User login

Effect of Vitamin D on Nonskeletal Tissue Yet Unknown

Available data are not strong enough to show a definitive association between vitamin D levels and risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, or maternal-fetal health, according to a comprehensive review of available research.

"The efficacy issue [of vitamin D] remains a major question mark," said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen in an interview. He chaired the group that wrote the scientific statement published by Endocrine Society (Endocr. Rev. 2012 May 17 [doi:10.1210/er.2012-1000]).

The scientific statement takes a comprehensive look at basic and clinical evidence related to the effect of vitamin D and various organ systems.

Although some observational studies have shown that benefits of vitamin D may extend beyond bone health, the findings are inconsistent, the authors noted.

"We need large randomized controlled trials and dose-response data to test the effects of vitamin D on chronic disease outcomes including autoimmunity, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease," said Dr. Rosen, professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston, in a statement.

Dr. Robert H. Eckel, past president of the American Heart Association, said he agreed with the findings of the report. He said that physicians should be aware of low vitamin D levels and should correct the deficiencies, but they should not make any strong statements about vitamin D levels and risk for conditions such as heart disease or cancer, due to lack of sufficient evidence.

He added that ultimately, data from large, well-designed trials "may be informative in uncovering a relationship that’s more meaningful." Dr. Eckel, who is a professor of medicine at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, was not involved in the study.

Interest in vitamin D as a therapeutic option for the prevention of chronic disease has been growing in recent years, the authors noted. "In a 2-month span during the summer of 2011, there were more than 500 publications centered on vitamin D, most of which were related to its relationship to nonskeletal tissues," they wrote. But the results, they added, are confounded and difficult to interpret.

By organ or disorder, the authors came to the following conclusions:

• Skin. "There are no large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials demonstrating that vitamin D metabolites are superior to other types of treatment for various proliferative skin disorders or for the prevention of skin cancer."

• Obesity and diabetes mellitus. "The ever-expanding obesity epidemic has been associated with a rising prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established. ... There remains a paucity of randomized controlled trials of vitamin D for the prevention of diabetes; hence, few conclusions can be firmly established."

• Fall prevention and improvement in quality of life. Citing the public health implication of fall prevention, and the report by the Institute of Medicine, the authors wrote, "The absolute threshold level of [vitamin D] needed to prevent falls in an elderly population is not known in part because of lack of true dose-ranging studies. ... Selecting patients at risk for falls and defining the appropriate dose remains as areas in need of further research."

• Cancer. "Despite biological plausibility for a role of vitamin D in cancer prevention, most recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as a comprehensive review by the IOM Committee, have found that the evidence that vitamin D reduces cancer incidence and/or mortality is inconsistent and inconclusive as to causality."

• Cardiovascular disease. Although there is a possibility that vitamin D supplementation may lower cardiovascular risk, "additional research, particularly from randomized trials, is needed."

• The placenta and maternal-fetal health. "There is insufficient evidence to recommend a particular maternal intake of vitamin D or [serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D] blood level during pregnancy to achieve any purported nonskeletal benefit of vitamin D," the authors wrote, but they added that "the biological plausibility may be sufficient to justify clinical trials to test whether vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy will prevent type 1 diabetes in the offspring."

"We’re hopeful that some of the intervention trial [on vitamin D] will get underway, and although they’re expensive, their findings can help change practice," said Dr. Rosen.

Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Available data are not strong enough to show a definitive association between vitamin D levels and risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, or maternal-fetal health, according to a comprehensive review of available research.

"The efficacy issue [of vitamin D] remains a major question mark," said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen in an interview. He chaired the group that wrote the scientific statement published by Endocrine Society (Endocr. Rev. 2012 May 17 [doi:10.1210/er.2012-1000]).

The scientific statement takes a comprehensive look at basic and clinical evidence related to the effect of vitamin D and various organ systems.

Although some observational studies have shown that benefits of vitamin D may extend beyond bone health, the findings are inconsistent, the authors noted.

"We need large randomized controlled trials and dose-response data to test the effects of vitamin D on chronic disease outcomes including autoimmunity, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease," said Dr. Rosen, professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston, in a statement.

Dr. Robert H. Eckel, past president of the American Heart Association, said he agreed with the findings of the report. He said that physicians should be aware of low vitamin D levels and should correct the deficiencies, but they should not make any strong statements about vitamin D levels and risk for conditions such as heart disease or cancer, due to lack of sufficient evidence.

He added that ultimately, data from large, well-designed trials "may be informative in uncovering a relationship that’s more meaningful." Dr. Eckel, who is a professor of medicine at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, was not involved in the study.

Interest in vitamin D as a therapeutic option for the prevention of chronic disease has been growing in recent years, the authors noted. "In a 2-month span during the summer of 2011, there were more than 500 publications centered on vitamin D, most of which were related to its relationship to nonskeletal tissues," they wrote. But the results, they added, are confounded and difficult to interpret.

By organ or disorder, the authors came to the following conclusions:

• Skin. "There are no large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials demonstrating that vitamin D metabolites are superior to other types of treatment for various proliferative skin disorders or for the prevention of skin cancer."

• Obesity and diabetes mellitus. "The ever-expanding obesity epidemic has been associated with a rising prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established. ... There remains a paucity of randomized controlled trials of vitamin D for the prevention of diabetes; hence, few conclusions can be firmly established."

• Fall prevention and improvement in quality of life. Citing the public health implication of fall prevention, and the report by the Institute of Medicine, the authors wrote, "The absolute threshold level of [vitamin D] needed to prevent falls in an elderly population is not known in part because of lack of true dose-ranging studies. ... Selecting patients at risk for falls and defining the appropriate dose remains as areas in need of further research."

• Cancer. "Despite biological plausibility for a role of vitamin D in cancer prevention, most recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as a comprehensive review by the IOM Committee, have found that the evidence that vitamin D reduces cancer incidence and/or mortality is inconsistent and inconclusive as to causality."

• Cardiovascular disease. Although there is a possibility that vitamin D supplementation may lower cardiovascular risk, "additional research, particularly from randomized trials, is needed."

• The placenta and maternal-fetal health. "There is insufficient evidence to recommend a particular maternal intake of vitamin D or [serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D] blood level during pregnancy to achieve any purported nonskeletal benefit of vitamin D," the authors wrote, but they added that "the biological plausibility may be sufficient to justify clinical trials to test whether vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy will prevent type 1 diabetes in the offspring."

"We’re hopeful that some of the intervention trial [on vitamin D] will get underway, and although they’re expensive, their findings can help change practice," said Dr. Rosen.

Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Available data are not strong enough to show a definitive association between vitamin D levels and risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, or maternal-fetal health, according to a comprehensive review of available research.

"The efficacy issue [of vitamin D] remains a major question mark," said Dr. Clifford J. Rosen in an interview. He chaired the group that wrote the scientific statement published by Endocrine Society (Endocr. Rev. 2012 May 17 [doi:10.1210/er.2012-1000]).

The scientific statement takes a comprehensive look at basic and clinical evidence related to the effect of vitamin D and various organ systems.

Although some observational studies have shown that benefits of vitamin D may extend beyond bone health, the findings are inconsistent, the authors noted.

"We need large randomized controlled trials and dose-response data to test the effects of vitamin D on chronic disease outcomes including autoimmunity, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease," said Dr. Rosen, professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston, in a statement.

Dr. Robert H. Eckel, past president of the American Heart Association, said he agreed with the findings of the report. He said that physicians should be aware of low vitamin D levels and should correct the deficiencies, but they should not make any strong statements about vitamin D levels and risk for conditions such as heart disease or cancer, due to lack of sufficient evidence.

He added that ultimately, data from large, well-designed trials "may be informative in uncovering a relationship that’s more meaningful." Dr. Eckel, who is a professor of medicine at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, was not involved in the study.

Interest in vitamin D as a therapeutic option for the prevention of chronic disease has been growing in recent years, the authors noted. "In a 2-month span during the summer of 2011, there were more than 500 publications centered on vitamin D, most of which were related to its relationship to nonskeletal tissues," they wrote. But the results, they added, are confounded and difficult to interpret.

By organ or disorder, the authors came to the following conclusions:

• Skin. "There are no large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials demonstrating that vitamin D metabolites are superior to other types of treatment for various proliferative skin disorders or for the prevention of skin cancer."

• Obesity and diabetes mellitus. "The ever-expanding obesity epidemic has been associated with a rising prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established. ... There remains a paucity of randomized controlled trials of vitamin D for the prevention of diabetes; hence, few conclusions can be firmly established."

• Fall prevention and improvement in quality of life. Citing the public health implication of fall prevention, and the report by the Institute of Medicine, the authors wrote, "The absolute threshold level of [vitamin D] needed to prevent falls in an elderly population is not known in part because of lack of true dose-ranging studies. ... Selecting patients at risk for falls and defining the appropriate dose remains as areas in need of further research."

• Cancer. "Despite biological plausibility for a role of vitamin D in cancer prevention, most recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as a comprehensive review by the IOM Committee, have found that the evidence that vitamin D reduces cancer incidence and/or mortality is inconsistent and inconclusive as to causality."

• Cardiovascular disease. Although there is a possibility that vitamin D supplementation may lower cardiovascular risk, "additional research, particularly from randomized trials, is needed."

• The placenta and maternal-fetal health. "There is insufficient evidence to recommend a particular maternal intake of vitamin D or [serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D] blood level during pregnancy to achieve any purported nonskeletal benefit of vitamin D," the authors wrote, but they added that "the biological plausibility may be sufficient to justify clinical trials to test whether vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy will prevent type 1 diabetes in the offspring."

"We’re hopeful that some of the intervention trial [on vitamin D] will get underway, and although they’re expensive, their findings can help change practice," said Dr. Rosen.

Dr. Rosen reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Some Risk Factors for Failed Epidural Conversion Are Modifiable

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Several factors, some of them modifiable, increase the odds of a failed conversion from epidural analgesia for labor to epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery, concluded the first systematic review and meta-analysis of this issue.

The analysis found that 1 in every 20 women having an epidural in place and needing a cesarean had to undergo general anesthesia because the epidural could not be used for anesthesia, lead investigator Melissa E.B. Bauer, D.O., reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology.

Women had a more than tripling of the odds of failed conversion if they needed two or more epidural analgesia boluses (so-called top-ups) during labor, had a general anesthesiologist instead of an obstetric anesthesiologist, or required a cesarean on a more urgent basis.

The findings underscored the need to investigate if a patient needs top-ups, according to Dr. Bauer. If a patient makes two or more requests for more analgesia, has breakthrough pain, and is really uncomfortable, she needs to be assessed to see if she has a nonworking epidural. If so, it needs to be replaced, she said in an interview, while noting that other factors, such as dystocia, may also be a cause.

The higher odds of failed conversion that are seen with a general anesthesiologist suggest that "people who manage labor and delivery more often are going to be a little bit more comfortable troubleshooting epidurals and trying to avoid a general anesthetic," commented Dr. Bauer, who is an obstetric anesthesiologist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

The risk with an urgent cesarean may be the hardest to modify. "We can’t really do anything about that, except to have better communication of obstetricians and [obstetric] anesthesia; to say, if you tell us [a cesarean is coming], maybe we can run to the room and start bolusing that epidural so that by the time the [patient] gets to the OR, we have enough of a level so that [you] can start and avoid a general," she explained. "So the main points are, having more cooperation and also evaluating the [fetal-monitoring] strip, and saying okay, do we have 5 or 10 minutes to convert [the epidural] or not – those things might be helpful."

Dr. Brenda A. Bucklin, professor of anesthesiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and comoderator of a related poster discussion session, asked, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists less comfortable in providing general anesthesia for cesarean delivery?"

"I think that it’s the opposite," Dr. Bauer replied. "Since we provide anesthesia for pregnant patients on a daily or weekly basis, we have more familiarity with the obstetric airway, and we are also called to the main hospital to provide anesthesia on any pregnant patient there as well."

Dr. Bucklin also wanted to know, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists more likely to limp along with a bad epidural for cesarean delivery?"

"I would say no, but part of the difference is that we tend to troubleshoot our epidurals sooner because we can look at the fetal strips and say, oh, I think [the baby’s] coming, and we go and evaluate the patient on a regular basis," Dr. Bauer said. "Also, once a C-section is called, we’re in the room and we have some familiarity with the surgeons to see [if this is] really an emergency, is there time for me to bolus this. I think that [because of] those relationships and also our understanding of [obstetrics] in general, we have a decreased rate of general anesthesia."

There are several reasons to want to avoid a failed epidural conversion and have to resort to general anesthesia, she noted in the interview. Managing the airway in obstetric patients can be challenging, and there are risks associated with using another type of anesthesia on top of an epidural. "You always want the mother to be able to participate in the birth as well," she added.

The investigators identified 13 observational studies with a total of 8,628 women that assessed the rate of failed conversion and risk factors for this outcome.

Results showed that the percentage of patients having an epidural catheter in place who still had to undergo general anesthesia for their cesarean averaged 5%, with a range of 0%-21% across studies, reported Dr. Bauer.

Women’s odds of failed conversion increased significantly if they needed at least two clinician-administered top-ups of analgesia during labor vs. no top-ups (odds ratio, 3.2), had a general vs. obstetric anesthesiologist (OR, 4.6), or required a more urgent cesarean delivery (OR, 40.4).

A variety of other factors were not significantly associated with the odds of failed conversion: combined spinal-epidural instead of standard epidural techniques, the duration of epidural analgesia, the extent of cervical dilation at the time of epidural placement, and obesity.

However, Dr. Bauer noted, the lack of association for obesity is uncertain, given that studies varied widely in terms of when they assessed body mass index or weight relative to pregnancy. "Also, most anesthesiologists are not going to let a patient who is really obese have a nonworking epidural because we don’t want to put her to sleep" and use general anesthesia, she added.

Dr. Bauer disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Several factors, some of them modifiable, increase the odds of a failed conversion from epidural analgesia for labor to epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery, concluded the first systematic review and meta-analysis of this issue.

The analysis found that 1 in every 20 women having an epidural in place and needing a cesarean had to undergo general anesthesia because the epidural could not be used for anesthesia, lead investigator Melissa E.B. Bauer, D.O., reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology.

Women had a more than tripling of the odds of failed conversion if they needed two or more epidural analgesia boluses (so-called top-ups) during labor, had a general anesthesiologist instead of an obstetric anesthesiologist, or required a cesarean on a more urgent basis.

The findings underscored the need to investigate if a patient needs top-ups, according to Dr. Bauer. If a patient makes two or more requests for more analgesia, has breakthrough pain, and is really uncomfortable, she needs to be assessed to see if she has a nonworking epidural. If so, it needs to be replaced, she said in an interview, while noting that other factors, such as dystocia, may also be a cause.

The higher odds of failed conversion that are seen with a general anesthesiologist suggest that "people who manage labor and delivery more often are going to be a little bit more comfortable troubleshooting epidurals and trying to avoid a general anesthetic," commented Dr. Bauer, who is an obstetric anesthesiologist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

The risk with an urgent cesarean may be the hardest to modify. "We can’t really do anything about that, except to have better communication of obstetricians and [obstetric] anesthesia; to say, if you tell us [a cesarean is coming], maybe we can run to the room and start bolusing that epidural so that by the time the [patient] gets to the OR, we have enough of a level so that [you] can start and avoid a general," she explained. "So the main points are, having more cooperation and also evaluating the [fetal-monitoring] strip, and saying okay, do we have 5 or 10 minutes to convert [the epidural] or not – those things might be helpful."

Dr. Brenda A. Bucklin, professor of anesthesiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and comoderator of a related poster discussion session, asked, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists less comfortable in providing general anesthesia for cesarean delivery?"

"I think that it’s the opposite," Dr. Bauer replied. "Since we provide anesthesia for pregnant patients on a daily or weekly basis, we have more familiarity with the obstetric airway, and we are also called to the main hospital to provide anesthesia on any pregnant patient there as well."

Dr. Bucklin also wanted to know, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists more likely to limp along with a bad epidural for cesarean delivery?"

"I would say no, but part of the difference is that we tend to troubleshoot our epidurals sooner because we can look at the fetal strips and say, oh, I think [the baby’s] coming, and we go and evaluate the patient on a regular basis," Dr. Bauer said. "Also, once a C-section is called, we’re in the room and we have some familiarity with the surgeons to see [if this is] really an emergency, is there time for me to bolus this. I think that [because of] those relationships and also our understanding of [obstetrics] in general, we have a decreased rate of general anesthesia."

There are several reasons to want to avoid a failed epidural conversion and have to resort to general anesthesia, she noted in the interview. Managing the airway in obstetric patients can be challenging, and there are risks associated with using another type of anesthesia on top of an epidural. "You always want the mother to be able to participate in the birth as well," she added.

The investigators identified 13 observational studies with a total of 8,628 women that assessed the rate of failed conversion and risk factors for this outcome.

Results showed that the percentage of patients having an epidural catheter in place who still had to undergo general anesthesia for their cesarean averaged 5%, with a range of 0%-21% across studies, reported Dr. Bauer.

Women’s odds of failed conversion increased significantly if they needed at least two clinician-administered top-ups of analgesia during labor vs. no top-ups (odds ratio, 3.2), had a general vs. obstetric anesthesiologist (OR, 4.6), or required a more urgent cesarean delivery (OR, 40.4).

A variety of other factors were not significantly associated with the odds of failed conversion: combined spinal-epidural instead of standard epidural techniques, the duration of epidural analgesia, the extent of cervical dilation at the time of epidural placement, and obesity.

However, Dr. Bauer noted, the lack of association for obesity is uncertain, given that studies varied widely in terms of when they assessed body mass index or weight relative to pregnancy. "Also, most anesthesiologists are not going to let a patient who is really obese have a nonworking epidural because we don’t want to put her to sleep" and use general anesthesia, she added.

Dr. Bauer disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Several factors, some of them modifiable, increase the odds of a failed conversion from epidural analgesia for labor to epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery, concluded the first systematic review and meta-analysis of this issue.

The analysis found that 1 in every 20 women having an epidural in place and needing a cesarean had to undergo general anesthesia because the epidural could not be used for anesthesia, lead investigator Melissa E.B. Bauer, D.O., reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology.

Women had a more than tripling of the odds of failed conversion if they needed two or more epidural analgesia boluses (so-called top-ups) during labor, had a general anesthesiologist instead of an obstetric anesthesiologist, or required a cesarean on a more urgent basis.

The findings underscored the need to investigate if a patient needs top-ups, according to Dr. Bauer. If a patient makes two or more requests for more analgesia, has breakthrough pain, and is really uncomfortable, she needs to be assessed to see if she has a nonworking epidural. If so, it needs to be replaced, she said in an interview, while noting that other factors, such as dystocia, may also be a cause.

The higher odds of failed conversion that are seen with a general anesthesiologist suggest that "people who manage labor and delivery more often are going to be a little bit more comfortable troubleshooting epidurals and trying to avoid a general anesthetic," commented Dr. Bauer, who is an obstetric anesthesiologist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

The risk with an urgent cesarean may be the hardest to modify. "We can’t really do anything about that, except to have better communication of obstetricians and [obstetric] anesthesia; to say, if you tell us [a cesarean is coming], maybe we can run to the room and start bolusing that epidural so that by the time the [patient] gets to the OR, we have enough of a level so that [you] can start and avoid a general," she explained. "So the main points are, having more cooperation and also evaluating the [fetal-monitoring] strip, and saying okay, do we have 5 or 10 minutes to convert [the epidural] or not – those things might be helpful."

Dr. Brenda A. Bucklin, professor of anesthesiology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and comoderator of a related poster discussion session, asked, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists less comfortable in providing general anesthesia for cesarean delivery?"

"I think that it’s the opposite," Dr. Bauer replied. "Since we provide anesthesia for pregnant patients on a daily or weekly basis, we have more familiarity with the obstetric airway, and we are also called to the main hospital to provide anesthesia on any pregnant patient there as well."

Dr. Bucklin also wanted to know, "Are [obstetric] anesthesiologists more likely to limp along with a bad epidural for cesarean delivery?"

"I would say no, but part of the difference is that we tend to troubleshoot our epidurals sooner because we can look at the fetal strips and say, oh, I think [the baby’s] coming, and we go and evaluate the patient on a regular basis," Dr. Bauer said. "Also, once a C-section is called, we’re in the room and we have some familiarity with the surgeons to see [if this is] really an emergency, is there time for me to bolus this. I think that [because of] those relationships and also our understanding of [obstetrics] in general, we have a decreased rate of general anesthesia."

There are several reasons to want to avoid a failed epidural conversion and have to resort to general anesthesia, she noted in the interview. Managing the airway in obstetric patients can be challenging, and there are risks associated with using another type of anesthesia on top of an epidural. "You always want the mother to be able to participate in the birth as well," she added.

The investigators identified 13 observational studies with a total of 8,628 women that assessed the rate of failed conversion and risk factors for this outcome.

Results showed that the percentage of patients having an epidural catheter in place who still had to undergo general anesthesia for their cesarean averaged 5%, with a range of 0%-21% across studies, reported Dr. Bauer.

Women’s odds of failed conversion increased significantly if they needed at least two clinician-administered top-ups of analgesia during labor vs. no top-ups (odds ratio, 3.2), had a general vs. obstetric anesthesiologist (OR, 4.6), or required a more urgent cesarean delivery (OR, 40.4).

A variety of other factors were not significantly associated with the odds of failed conversion: combined spinal-epidural instead of standard epidural techniques, the duration of epidural analgesia, the extent of cervical dilation at the time of epidural placement, and obesity.

However, Dr. Bauer noted, the lack of association for obesity is uncertain, given that studies varied widely in terms of when they assessed body mass index or weight relative to pregnancy. "Also, most anesthesiologists are not going to let a patient who is really obese have a nonworking epidural because we don’t want to put her to sleep" and use general anesthesia, she added.

Dr. Bauer disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY FOR OBSTETRIC ANESTHESIA AND PERINATOLOGY

Major Finding: Women’s odds of failed conversion were increased if they received two or more analgesia boluses during labor (OR, 3.2), had a general vs. obstetric anesthesiologist (OR, 4.6), or required a more urgent cesarean delivery (OR, 40.4).

Data Source: The data are from systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies with a total of 8,628 women that assessed conversion of epidural labor analgesia to epidural cesarean anesthesia.

Disclosures: Dr. Bauer disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Obstetric Outcomes Fairly Good Despite Maternal CHD

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Parturients with congenital heart disease do have a rockier obstetric course, but generally fare quite well in the peripartum period, a retrospective cohort study found.

Researchers at the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver led by Christine M. Warrick found that roughly 1% of women delivering there over a 4-year period had congenital heart disease.

This group had higher rates of cesarean delivery and neonatal ICU admission than did parturients overall, according to results reported in a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Maternal ICU admissions were rare, however, and there were no cases of maternal mortality.

"Congenital heart disease is definitely a risk factor for maternal and fetal complications, but overall the women seemed to do pretty well. The main things to look out for would be neonatal ICU admissions and respiratory distress in the babies," Ms. Warrick commented in an interview.

In additional study findings, although the large majority of women received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only a minority had an epidural placed early, before 4 cm of cervical dilation.

"There is some literature that suggests that early epidural placement is beneficial for these women because it decreases the stress on the heart secondary to pain," she noted. "Some of these women come [to the hospital] in labor and they are already beyond 4 cm of dilation, so that may be a big reason why there weren’t so many early epidurals placed."

In a related poster discussion session, comoderator Dr. Katherine W. Arendt of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked, "Do you believe that the geographical elevation of your hospital improved or worsened your outcomes compared to a sea-level hospital?"

"It’s difficult to say exactly how the elevation affected all of these women, since we had so many different varieties of congenital heart disease," replied Ms. Warrick, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Colorado in Aurora. "But it is possible that women with more severe congenital heart disease would not tolerate a lower partial pressure of oxygen in our environment, and there were some women who were advised to deliver at lower altitudes because of this. So that probably improved our outcomes in women who received adequate prenatal care. I also think that points to the importance of prenatal care in these women."

"We know that more women are surviving to childbearing age with congenital heart disease due to the recent advances in surgical repair of these defects, and it is actually one of the major causes of cardiac diseases in pregnant women in the United States," she said. Many of the normal changes of pregnancy, labor, and delivery put stress on the heart and would be expected to exacerbate matters.

The investigators studied 13,109 parturients in the hospital’s perinatal database between October 2005 and December 2009. Medical history and record review identified 75 women, or 0.6%, as having congenital heart disease.

These women had a mean age of 26 years. The majority were non-Hispanic white (60%) and nulliparous (55%). Fully 34% were overweight or obese, and 8% smoked.

According to cardiologists’ notes of symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy, 60%, 33%, and 7% of the women had New York Heart Association functional class I, II, and III, respectively. The leading congenital anomalies were atrial septal defects (28%), valvular disorders (19%), and tetralogy of Fallot (11%).

In terms of cardiac outcomes, 11% of the women had an arrhythmia in the peripartum period, and 5% required diuresis, Ms. Warrick reported. Although 87% received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only 31% received an early epidural.

Some 19% of the women had a preterm birth (one occurring before 37 weeks’ gestation), and 45% had a prolonged hospital stay (lasting more than 2 days after a vaginal delivery or more than 3 days after a cesarean delivery).

Although 3% of the women were admitted to the ICU for prophylactic monitoring, there were no maternal deaths in the peripartum period.

Compared with parturients overall, those with congenital heart disease were more likely to have a cesarean delivery (31% vs. 27%) and a neonatal ICU admission (23% vs. 15%). The majority of the neonatal ICU admissions were for prematurity or respiratory distress.

"In anyone with congenital heart disease, prenatal care is very important, and a lot of these women were followed closely by a team of physicians [specializing in high-risk pregnancies]," noted Ms. Warrick.

"All in all, pregnant women with congenital heart disease can undergo labor and delivery without many complications, but tend to have longer hospital stays and more neonatal ICU admissions," she concluded.

Ms. Warrick disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Parturients with congenital heart disease do have a rockier obstetric course, but generally fare quite well in the peripartum period, a retrospective cohort study found.

Researchers at the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver led by Christine M. Warrick found that roughly 1% of women delivering there over a 4-year period had congenital heart disease.

This group had higher rates of cesarean delivery and neonatal ICU admission than did parturients overall, according to results reported in a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Maternal ICU admissions were rare, however, and there were no cases of maternal mortality.

"Congenital heart disease is definitely a risk factor for maternal and fetal complications, but overall the women seemed to do pretty well. The main things to look out for would be neonatal ICU admissions and respiratory distress in the babies," Ms. Warrick commented in an interview.

In additional study findings, although the large majority of women received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only a minority had an epidural placed early, before 4 cm of cervical dilation.

"There is some literature that suggests that early epidural placement is beneficial for these women because it decreases the stress on the heart secondary to pain," she noted. "Some of these women come [to the hospital] in labor and they are already beyond 4 cm of dilation, so that may be a big reason why there weren’t so many early epidurals placed."

In a related poster discussion session, comoderator Dr. Katherine W. Arendt of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked, "Do you believe that the geographical elevation of your hospital improved or worsened your outcomes compared to a sea-level hospital?"

"It’s difficult to say exactly how the elevation affected all of these women, since we had so many different varieties of congenital heart disease," replied Ms. Warrick, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Colorado in Aurora. "But it is possible that women with more severe congenital heart disease would not tolerate a lower partial pressure of oxygen in our environment, and there were some women who were advised to deliver at lower altitudes because of this. So that probably improved our outcomes in women who received adequate prenatal care. I also think that points to the importance of prenatal care in these women."

"We know that more women are surviving to childbearing age with congenital heart disease due to the recent advances in surgical repair of these defects, and it is actually one of the major causes of cardiac diseases in pregnant women in the United States," she said. Many of the normal changes of pregnancy, labor, and delivery put stress on the heart and would be expected to exacerbate matters.

The investigators studied 13,109 parturients in the hospital’s perinatal database between October 2005 and December 2009. Medical history and record review identified 75 women, or 0.6%, as having congenital heart disease.

These women had a mean age of 26 years. The majority were non-Hispanic white (60%) and nulliparous (55%). Fully 34% were overweight or obese, and 8% smoked.

According to cardiologists’ notes of symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy, 60%, 33%, and 7% of the women had New York Heart Association functional class I, II, and III, respectively. The leading congenital anomalies were atrial septal defects (28%), valvular disorders (19%), and tetralogy of Fallot (11%).

In terms of cardiac outcomes, 11% of the women had an arrhythmia in the peripartum period, and 5% required diuresis, Ms. Warrick reported. Although 87% received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only 31% received an early epidural.

Some 19% of the women had a preterm birth (one occurring before 37 weeks’ gestation), and 45% had a prolonged hospital stay (lasting more than 2 days after a vaginal delivery or more than 3 days after a cesarean delivery).

Although 3% of the women were admitted to the ICU for prophylactic monitoring, there were no maternal deaths in the peripartum period.

Compared with parturients overall, those with congenital heart disease were more likely to have a cesarean delivery (31% vs. 27%) and a neonatal ICU admission (23% vs. 15%). The majority of the neonatal ICU admissions were for prematurity or respiratory distress.

"In anyone with congenital heart disease, prenatal care is very important, and a lot of these women were followed closely by a team of physicians [specializing in high-risk pregnancies]," noted Ms. Warrick.

"All in all, pregnant women with congenital heart disease can undergo labor and delivery without many complications, but tend to have longer hospital stays and more neonatal ICU admissions," she concluded.

Ms. Warrick disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

MONTEREY, CALIF. – Parturients with congenital heart disease do have a rockier obstetric course, but generally fare quite well in the peripartum period, a retrospective cohort study found.

Researchers at the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver led by Christine M. Warrick found that roughly 1% of women delivering there over a 4-year period had congenital heart disease.

This group had higher rates of cesarean delivery and neonatal ICU admission than did parturients overall, according to results reported in a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Maternal ICU admissions were rare, however, and there were no cases of maternal mortality.

"Congenital heart disease is definitely a risk factor for maternal and fetal complications, but overall the women seemed to do pretty well. The main things to look out for would be neonatal ICU admissions and respiratory distress in the babies," Ms. Warrick commented in an interview.

In additional study findings, although the large majority of women received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only a minority had an epidural placed early, before 4 cm of cervical dilation.

"There is some literature that suggests that early epidural placement is beneficial for these women because it decreases the stress on the heart secondary to pain," she noted. "Some of these women come [to the hospital] in labor and they are already beyond 4 cm of dilation, so that may be a big reason why there weren’t so many early epidurals placed."

In a related poster discussion session, comoderator Dr. Katherine W. Arendt of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., asked, "Do you believe that the geographical elevation of your hospital improved or worsened your outcomes compared to a sea-level hospital?"

"It’s difficult to say exactly how the elevation affected all of these women, since we had so many different varieties of congenital heart disease," replied Ms. Warrick, who is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Colorado in Aurora. "But it is possible that women with more severe congenital heart disease would not tolerate a lower partial pressure of oxygen in our environment, and there were some women who were advised to deliver at lower altitudes because of this. So that probably improved our outcomes in women who received adequate prenatal care. I also think that points to the importance of prenatal care in these women."

"We know that more women are surviving to childbearing age with congenital heart disease due to the recent advances in surgical repair of these defects, and it is actually one of the major causes of cardiac diseases in pregnant women in the United States," she said. Many of the normal changes of pregnancy, labor, and delivery put stress on the heart and would be expected to exacerbate matters.

The investigators studied 13,109 parturients in the hospital’s perinatal database between October 2005 and December 2009. Medical history and record review identified 75 women, or 0.6%, as having congenital heart disease.

These women had a mean age of 26 years. The majority were non-Hispanic white (60%) and nulliparous (55%). Fully 34% were overweight or obese, and 8% smoked.

According to cardiologists’ notes of symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy, 60%, 33%, and 7% of the women had New York Heart Association functional class I, II, and III, respectively. The leading congenital anomalies were atrial septal defects (28%), valvular disorders (19%), and tetralogy of Fallot (11%).

In terms of cardiac outcomes, 11% of the women had an arrhythmia in the peripartum period, and 5% required diuresis, Ms. Warrick reported. Although 87% received regional anesthesia for labor and delivery, only 31% received an early epidural.

Some 19% of the women had a preterm birth (one occurring before 37 weeks’ gestation), and 45% had a prolonged hospital stay (lasting more than 2 days after a vaginal delivery or more than 3 days after a cesarean delivery).

Although 3% of the women were admitted to the ICU for prophylactic monitoring, there were no maternal deaths in the peripartum period.

Compared with parturients overall, those with congenital heart disease were more likely to have a cesarean delivery (31% vs. 27%) and a neonatal ICU admission (23% vs. 15%). The majority of the neonatal ICU admissions were for prematurity or respiratory distress.

"In anyone with congenital heart disease, prenatal care is very important, and a lot of these women were followed closely by a team of physicians [specializing in high-risk pregnancies]," noted Ms. Warrick.

"All in all, pregnant women with congenital heart disease can undergo labor and delivery without many complications, but tend to have longer hospital stays and more neonatal ICU admissions," she concluded.

Ms. Warrick disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOCIETY FOR OBSTETRIC ANESTHESIA AND PERINATOLOGY

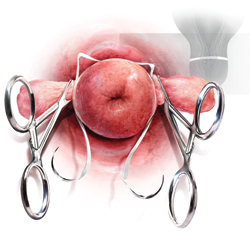

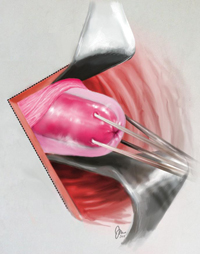

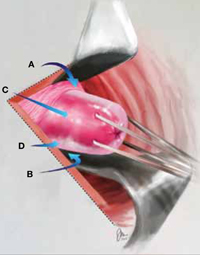

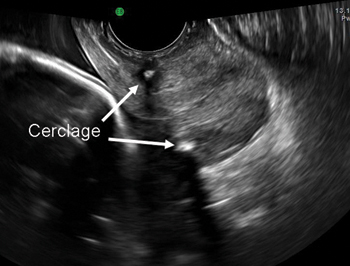

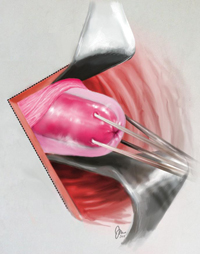

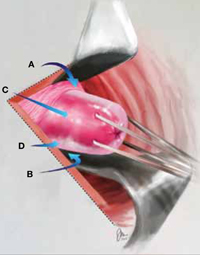

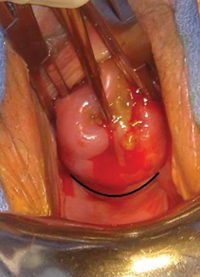

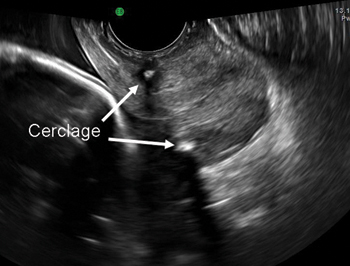

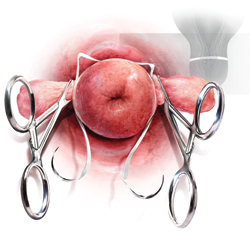

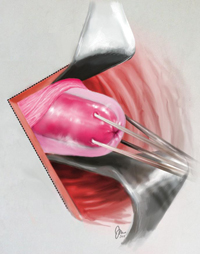

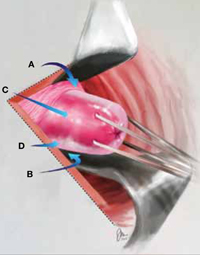

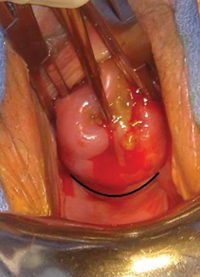

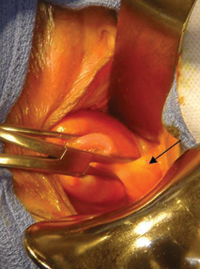

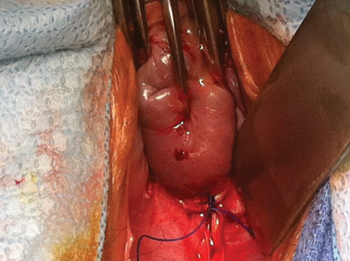

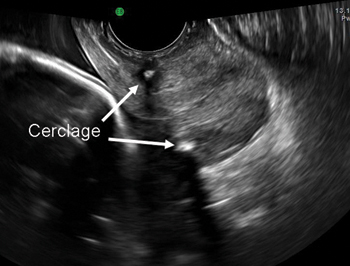

Why high placement of the cerclage is a key to success

UPDATE: INFECTIOUS DISEASE

- 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis

Meghan O. Schimpf (June 2012) - Gaps in Chlamydia testing threaten reproductive health, CDC warns

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (Web exclusive, May 2012)

Dr. Duff reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

In this Update, I’ve highlighted four interesting articles about infectious disease management in obstetric and gyn practice that appeared in the medical literature over the past 12 months:

- One describes a study that reminds physicians of the importance of an unusual manifestation of gonococcal infection

- A second article demonstrates the importance of making a change in the prophylactic antibiotic regimen provided to morbidly obese patients who are having a cesarean delivery

- A third describes an exciting development in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection

- The final article makes interesting observations about the proper duration of treatment for patients who have chorioamnionitis.

N gonorrhoeae causes illness beyond the urogenital tract

Bleich AT, Sheffield JS, Wendel GD, Sigman A, Cunningham FG. Disseminated gonococcal infection in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):597–602.

This article describes a retrospective review of 112 women who were admitted to Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas, from January 1975 through December 2008 and given a diagnosis of disseminated infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Eighty (71%) of these women were not pregnant and were cared for on the internal medicine service; 32 (29%) were pregnant and were treated by faculty members and residents on the ObGyn service.

Over the course of the study, the frequency of disseminated gonococcal infection decreased significantly. Among pregnant women, the rate of infection was 11 for every 100,000 deliveries before 1980 and, after 1985, five for every 100,000 deliveries.

The most common clinical manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection was arthritis. The most commonly affected joints were the knee, wrist, elbow, and ankle.

Other common clinical manifestations included dermatitis, fever, chills, and a purulent cervical discharge. Notably, the frequency of a purulent joint effusion was 50% in pregnant women and 70% in nonpregnant women—reflecting the fact that the duration of symptoms was approximately 3 days shorter in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women. Otherwise, the clinical presentation in pregnant women did not differ significantly from that of nonpregnant women.

In addition, the clinical course and the response to intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy did not differ significantly between pregnant and nonpregnant women.

The authors were unable to document that disseminated gonococcal infection had any deleterious effect on the outcome of pregnancy among the patients studied. Although four of the 32 women delivered preterm, in only one instance was delivery related temporally to the disseminated gonococcal infection.

Commentary

Because of their experience treating women who have gonorrhea, I would say that most ObGyns think of N gonorrhoeae as causing localized infection in the lower genital tract (urethritis, endocervicitis, inflammatory proctitis) or upper genital tract (pelvic inflammatory disease). We should recognize, however, that gonorrhea also can cause prominent extra-pelvic findings, such as severe pharyngitis (in patients who practice orogenital intercourse) and perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome).

In addition, always bear in mind that, in rare instances, gonorrhea can become disseminated, causing quite serious illness. The most common extra-pelvic manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection is arthritis. As noted in this study of a series of patients, the arthritis is usually polyarticular and affects medium or small joints.

The second most common manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection is dermatitis. Characteristic lesions are raised, red or purple papules. These lesions are not a simple vasculitis; rather, they contain a high concentration of microorganisms.

Other possible manifestations of disseminated infection include pericarditis, endocarditis, and meningitis.

The diagnosis of disseminated gonococcal infection is usually made by clinical examination and culture of specimens from the genital tract, blood, or joint effusion.

Disseminated gonococcal infection usually responds promptly to intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Recommended therapy is ceftriaxone:

• 25 to 50 mg/kg/d IV for 7 days

or

• a single, daily, 25 to 50 mg/kg intramuscular dose, also for 7 days.

Continue therapy for 10 to 14 days if the patient has meningitis.

An alternative regimen is cefotaxime:

• 25 mg/kg/d IV for 7 days

or

• 25 mg/kg IM every 12 hours, also for 7 days.

Extend treatment for 10 to 14 days if meningitis is present.1

Obesity curtails effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in cesarean delivery

Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, Wing DA, Chan K, Edmiston CE Jr. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

In this prospective study of the influence of an obese habitus on antibiotic prophylaxis during cesarean delivery, researchers divided 29 patients who were scheduled for cesarean into three groups, by body mass index (BMI):

- lean (BMI, <30; n = 10)

- obese (30–39.9; n = 10)

- extremely obese (>40; n = 9).

All patients were given a 2-g dose of IV cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before surgery.

During delivery, the team took two specimens of adipose tissue: one immediately after the skin incision and one later, after fascia was closed. They also obtained a specimen of myometrial tissue after delivery and a blood specimen after surgery was completed.

The concentration of cefazolin was then measured in adipose and myometrial tissue and in serum.

Findings. The researchers demonstrated that the mean concentration of cefazolin in the initial specimen of adipose tissue was significantly higher in lean patients than in obese and extremely obese patients. All 10 women who had a BMI less than 30 had a serum cefazolin concentration greater than 4 μg/g—the theoretical break-point for defining resistance to cefazolin. The initial adipose tissue specimen from two of the 10 obese patients and three of the nine extremely obese patients showed cefazolin concentrations less than 4 μg/g.

Of particular interest, two women—both of whom had a BMI greater than 40—developed a wound infection that required antibiotic therapy. Their initial and subsequent adipose tissue concentrations of cefazolin were less than the 4 μg/g break-point for resistance.

The concentration of cefazolin in the patients’ myometrial and serum specimens demonstrated a pattern similar to what the researchers observed in adipose tissue, but these results were not statistically significant across BMI groups. In fact, the cefazolin concentration in all groups’ myometrial and serum specimens exceeded the minimum inhibitory concentration for most potential pathogens in the setting of cesarean delivery.

Commentary

Clearly, prophylactic antibiotics are indicated for all women who are having a cesarean delivery. Antibiotics have their greatest impact when administered before the surgical incision is made; to exert their full protective effect against endometritis and wound infection, however, antibiotics should reach a recognized therapeutic concentration—not only in serum and myometrium but in the subcutaneous tissue.

The customary dosage of cefazolin for cesarean delivery prophylaxis has been 1 g. This study demonstrated that, although a 2-g dose of cefazolin reached a therapeutic concentration in myometrial tissue and serum, it did not consistently do so in the adipose tissue of obese and extremely obese patients.

Pending further investigation, I strongly recommend that all women who have a BMI greater than 30 receive a 2-g dose of cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before cesarean delivery. Future research is needed to determine whether an even higher dosage is necessary to achieve a therapeutic concentration in the subcutaneous tissue of morbidly obese patients.

New therapies promise a better outcome in hepatitis C

Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2405–2416.

The authors conducted an international Phase-3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two different treatment modalities for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The authors assigned 1,088 patients who had HCV genotype-1 infection and who had not received prior therapy to one of three treatment groups:

- telaprevir (Incivek, Vertex Pharmaceuticals), an HCV genotype-1 protease inhibitor, combined with peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys, Genetech) plus ribavirin (Copegus, Genetech; Rebetol, Merck; etc.) for 12 weeks; patients then were given peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin only for 12 additional weeks if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 4 and 12 or peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin only for 36 weeks if HCV RNA was detectable at either time point (Group 1)

- telaprevir with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 8 weeks, then placebo with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 4 weeks, followed by 12 to 36 weeks of peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin using the HCV RNA criteria applied to Group 1 (Group 2)

- placebo with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by 36 weeks of peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin (Group 3).

The primary endpoint of the trial was the percentage of patients who had undetectable plasma HCV RNA at 24 weeks after the last planned dose of the study drugs. The investigators considered that this endpoint represented a sustained virologic response.

Findings. Seventy-five percent of patients in Group 1 and 69% of those in Group 2 had a sustained virologic response. By comparison, only 44% of patients in Group 3 had a sustained response. The differences in outcome between Group 1 and Group 3, and between Group 2 and Group 3, were highly significant (P<.001). Virologic failure was more common among patients who had HCV genotype-1a infection than among those who had HCV genotype-1b infection.

The most common side effects noted by patients who received telaprevir were gastrointestinal irritation, rash, and anemia. Ten percent of patients in the telaprevir group discontinued therapy, compared with 7% in the peginterferon-ribavirin-alone group.

Commentary

Worldwide, approximately 170 million people have chronic hepatitis C, which is the most common indication for liver transplantation. Until recently, the principal treatments for hepatitis C were pegylated interferon alfa with ribavirin and without ribavirin; the response rate with these regimens was in the range of 55%. This study shows that adding telaprevir to regimens for HCV infection significantly improves prospects for long-term resolution of infection.

In some obstetric and gynecologic populations, HCV is more common than hepatitis B virus. Risk factors for hepatitis C include hepatitis B, intravenous drug abuse, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. HCV-infected women pose a risk to their sex partners; infected pregnant women can transmit the virus to their baby.

Unlike hepatitis A and hepatitis B, immunoprophylaxis is not available for hepatitis C. That reality is what makes the study by Jacobsen and colleagues so compelling: They have clearly demonstrated that multi-agent antiviral therapy might be able to truly cure this infection.

The lesson here for ObGyns? Screen at-risk patients and then refer the hepatitis C-seropositive ones to a specialist in gastroenterology, who can determine candidacy for one of the new treatment regimens.

Clearly, the prognosis for people who have hepatitis C is much better today than it was 20 years ago.

For how long should chorioamnionitis be treated?

Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(6):1102-1105.

The authors conducted a retrospective review of 423 women who had been treated for chorioamnionitis at the University of Florida from 2005 to 2009.

Patients had been given IV ampicillin (2 g every 6 h) plus IV gentamicin (1.5 mg/kg every 8 h) as soon as the diagnosis of chorioamnionitis was established; postpartum, they were given only the one next scheduled dose of each antibiotic. Patients who had a cesarean received either metronidazole (500 mg) or clindamycin (900 mg) immediately after cord clamping to enhance coverage of anaerobic organisms.

The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as persistent fever requiring continued antibiotics, surgical intervention, or administration of heparin for septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis.

Findings. Here is a breakdown of what the investigators found regarding the 282 women who delivered vaginally and the 141 who underwent cesarean delivery:

- Overall, 399 of the patients (94%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 92% and 96%) were treated successfully; 24 (6%; 95% CI, 3.7% and 8.3%) failed short-course treatment

- Of the 282 patients who delivered vaginally, 279 (99%; 95% CI, 98% and 100%) were cured with short-term therapy

- Of the 141 who delivered by cesarean, 120 (85%; 95% CI, 79% and 91%) were cured (P<.001).

- Seventeen of the total treatment failures had endometritis and responded quickly to continuation of antibiotics. Of the 17 patients with endometritis, 14 had a cesarean delivery.

- Seven patients had more serious complications: four, wound infection; three, septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis. All serious complications occurred after cesarean delivery.

- Of the four patients who had a wound infection, three had labor induced by misoprostol; their BMI was 44.8, 31.1, and 48.5, respectively. The fourth had a cesarean delivery at 29 weeks for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), chorioamnionitis, and malpresentation.

- Of the three patients who had septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis, two had labor induced by misoprostol. One had a BMI of 29.2; the other, 31.1. The third patient was delivered secondary to PPROM; her BMI was 40.3.

In addition, of the 21 treatment failures in the cesarean delivery group, 6 had prolonged rupture of membranes (ROM) and 10 had a BMI greater than 30. Six patients had both prolonged ROM and were obese or morbidly obese.

Of the 120 women who had a cesarean delivery and were treated successfully, 3 had prolonged ROM and 39 had a BMI greater than 30. None had both prolonged ROM and a BMI greater than 30.

Last, the difference between treatment failures and treatment successes in regard to the frequency of prolonged ROM or a BMI greater than 30 was highly significant (P<.01).

Commentary

In most published reports of patients who have chorioamnionitis, antibiotic treatment continues until the patient is afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. This treatment approach has been based largely on expert opinion, however, not on Level-1 or Level-2 evidence.

In 2003, Edwards and Duff published a study of chorioamnionitis antibiotic regimens that compared single-dose postpartum treatment to extended treatment.2 This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference between patients who had only a single dose of postpartum antibiotics and those who received an extended course of medication (i.e., who were treated until they had been afebrile and asymptomatic for a minimum of 24 hours) in regard to adverse outcomes (2.9% and 4.3%, respectively). The study discussed here extends and refines the observations made in the 2003 Edwards and Duff randomized controlled trial.

The new study shows that a limited course of antibiotics was, overall, effective in treating 94% of patients with chorioamnionitis (95% CI, 92% and 96%). Only 1% of patients who delivered vaginally failed therapy, compared with 15% of patients who delivered by cesarean (P<.001). In the cesarean group, women who failed therapy were likely to 1) be obese or 2) have a relatively long duration of labor or ruptured membranes, or both. These patients may have benefitted from a more extended course of antibiotic therapy.

Based on this investigation, I strongly recommend a limited course of antibiotic therapy (ampicillin plus gentamicin) for women with chorioamnionitis who deliver vaginally. Patients who have had a cesarean delivery—particularly those who are obese or have had an extended duration of labor, or both—should be treated with antibiotics until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Edwards RK, Duff P. Single dose postpartum therapy for women with chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):957-961.

- 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis

Meghan O. Schimpf (June 2012) - Gaps in Chlamydia testing threaten reproductive health, CDC warns

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor (Web exclusive, May 2012)

Dr. Duff reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

In this Update, I’ve highlighted four interesting articles about infectious disease management in obstetric and gyn practice that appeared in the medical literature over the past 12 months:

- One describes a study that reminds physicians of the importance of an unusual manifestation of gonococcal infection

- A second article demonstrates the importance of making a change in the prophylactic antibiotic regimen provided to morbidly obese patients who are having a cesarean delivery

- A third describes an exciting development in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection

- The final article makes interesting observations about the proper duration of treatment for patients who have chorioamnionitis.

N gonorrhoeae causes illness beyond the urogenital tract

Bleich AT, Sheffield JS, Wendel GD, Sigman A, Cunningham FG. Disseminated gonococcal infection in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):597–602.

This article describes a retrospective review of 112 women who were admitted to Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas, from January 1975 through December 2008 and given a diagnosis of disseminated infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Eighty (71%) of these women were not pregnant and were cared for on the internal medicine service; 32 (29%) were pregnant and were treated by faculty members and residents on the ObGyn service.

Over the course of the study, the frequency of disseminated gonococcal infection decreased significantly. Among pregnant women, the rate of infection was 11 for every 100,000 deliveries before 1980 and, after 1985, five for every 100,000 deliveries.

The most common clinical manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection was arthritis. The most commonly affected joints were the knee, wrist, elbow, and ankle.

Other common clinical manifestations included dermatitis, fever, chills, and a purulent cervical discharge. Notably, the frequency of a purulent joint effusion was 50% in pregnant women and 70% in nonpregnant women—reflecting the fact that the duration of symptoms was approximately 3 days shorter in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women. Otherwise, the clinical presentation in pregnant women did not differ significantly from that of nonpregnant women.

In addition, the clinical course and the response to intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy did not differ significantly between pregnant and nonpregnant women.

The authors were unable to document that disseminated gonococcal infection had any deleterious effect on the outcome of pregnancy among the patients studied. Although four of the 32 women delivered preterm, in only one instance was delivery related temporally to the disseminated gonococcal infection.

Commentary

Because of their experience treating women who have gonorrhea, I would say that most ObGyns think of N gonorrhoeae as causing localized infection in the lower genital tract (urethritis, endocervicitis, inflammatory proctitis) or upper genital tract (pelvic inflammatory disease). We should recognize, however, that gonorrhea also can cause prominent extra-pelvic findings, such as severe pharyngitis (in patients who practice orogenital intercourse) and perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome).

In addition, always bear in mind that, in rare instances, gonorrhea can become disseminated, causing quite serious illness. The most common extra-pelvic manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection is arthritis. As noted in this study of a series of patients, the arthritis is usually polyarticular and affects medium or small joints.

The second most common manifestation of disseminated gonococcal infection is dermatitis. Characteristic lesions are raised, red or purple papules. These lesions are not a simple vasculitis; rather, they contain a high concentration of microorganisms.

Other possible manifestations of disseminated infection include pericarditis, endocarditis, and meningitis.

The diagnosis of disseminated gonococcal infection is usually made by clinical examination and culture of specimens from the genital tract, blood, or joint effusion.

Disseminated gonococcal infection usually responds promptly to intravenous antibiotic therapy.

Recommended therapy is ceftriaxone:

• 25 to 50 mg/kg/d IV for 7 days

or

• a single, daily, 25 to 50 mg/kg intramuscular dose, also for 7 days.

Continue therapy for 10 to 14 days if the patient has meningitis.

An alternative regimen is cefotaxime:

• 25 mg/kg/d IV for 7 days

or

• 25 mg/kg IM every 12 hours, also for 7 days.

Extend treatment for 10 to 14 days if meningitis is present.1

Obesity curtails effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in cesarean delivery

Pevzner L, Swank M, Krepel C, Wing DA, Chan K, Edmiston CE Jr. Effects of maternal obesity on tissue concentrations of prophylactic cefazolin during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):877–882.

In this prospective study of the influence of an obese habitus on antibiotic prophylaxis during cesarean delivery, researchers divided 29 patients who were scheduled for cesarean into three groups, by body mass index (BMI):

- lean (BMI, <30; n = 10)

- obese (30–39.9; n = 10)

- extremely obese (>40; n = 9).

All patients were given a 2-g dose of IV cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before surgery.

During delivery, the team took two specimens of adipose tissue: one immediately after the skin incision and one later, after fascia was closed. They also obtained a specimen of myometrial tissue after delivery and a blood specimen after surgery was completed.

The concentration of cefazolin was then measured in adipose and myometrial tissue and in serum.

Findings. The researchers demonstrated that the mean concentration of cefazolin in the initial specimen of adipose tissue was significantly higher in lean patients than in obese and extremely obese patients. All 10 women who had a BMI less than 30 had a serum cefazolin concentration greater than 4 μg/g—the theoretical break-point for defining resistance to cefazolin. The initial adipose tissue specimen from two of the 10 obese patients and three of the nine extremely obese patients showed cefazolin concentrations less than 4 μg/g.

Of particular interest, two women—both of whom had a BMI greater than 40—developed a wound infection that required antibiotic therapy. Their initial and subsequent adipose tissue concentrations of cefazolin were less than the 4 μg/g break-point for resistance.

The concentration of cefazolin in the patients’ myometrial and serum specimens demonstrated a pattern similar to what the researchers observed in adipose tissue, but these results were not statistically significant across BMI groups. In fact, the cefazolin concentration in all groups’ myometrial and serum specimens exceeded the minimum inhibitory concentration for most potential pathogens in the setting of cesarean delivery.

Commentary

Clearly, prophylactic antibiotics are indicated for all women who are having a cesarean delivery. Antibiotics have their greatest impact when administered before the surgical incision is made; to exert their full protective effect against endometritis and wound infection, however, antibiotics should reach a recognized therapeutic concentration—not only in serum and myometrium but in the subcutaneous tissue.

The customary dosage of cefazolin for cesarean delivery prophylaxis has been 1 g. This study demonstrated that, although a 2-g dose of cefazolin reached a therapeutic concentration in myometrial tissue and serum, it did not consistently do so in the adipose tissue of obese and extremely obese patients.

Pending further investigation, I strongly recommend that all women who have a BMI greater than 30 receive a 2-g dose of cefazolin 30 to 60 minutes before cesarean delivery. Future research is needed to determine whether an even higher dosage is necessary to achieve a therapeutic concentration in the subcutaneous tissue of morbidly obese patients.

New therapies promise a better outcome in hepatitis C

Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2405–2416.

The authors conducted an international Phase-3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two different treatment modalities for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The authors assigned 1,088 patients who had HCV genotype-1 infection and who had not received prior therapy to one of three treatment groups:

- telaprevir (Incivek, Vertex Pharmaceuticals), an HCV genotype-1 protease inhibitor, combined with peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys, Genetech) plus ribavirin (Copegus, Genetech; Rebetol, Merck; etc.) for 12 weeks; patients then were given peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin only for 12 additional weeks if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 4 and 12 or peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin only for 36 weeks if HCV RNA was detectable at either time point (Group 1)

- telaprevir with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 8 weeks, then placebo with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 4 weeks, followed by 12 to 36 weeks of peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin using the HCV RNA criteria applied to Group 1 (Group 2)

- placebo with peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for 12 weeks, followed by 36 weeks of peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin (Group 3).

The primary endpoint of the trial was the percentage of patients who had undetectable plasma HCV RNA at 24 weeks after the last planned dose of the study drugs. The investigators considered that this endpoint represented a sustained virologic response.

Findings. Seventy-five percent of patients in Group 1 and 69% of those in Group 2 had a sustained virologic response. By comparison, only 44% of patients in Group 3 had a sustained response. The differences in outcome between Group 1 and Group 3, and between Group 2 and Group 3, were highly significant (P<.001). Virologic failure was more common among patients who had HCV genotype-1a infection than among those who had HCV genotype-1b infection.

The most common side effects noted by patients who received telaprevir were gastrointestinal irritation, rash, and anemia. Ten percent of patients in the telaprevir group discontinued therapy, compared with 7% in the peginterferon-ribavirin-alone group.

Commentary

Worldwide, approximately 170 million people have chronic hepatitis C, which is the most common indication for liver transplantation. Until recently, the principal treatments for hepatitis C were pegylated interferon alfa with ribavirin and without ribavirin; the response rate with these regimens was in the range of 55%. This study shows that adding telaprevir to regimens for HCV infection significantly improves prospects for long-term resolution of infection.

In some obstetric and gynecologic populations, HCV is more common than hepatitis B virus. Risk factors for hepatitis C include hepatitis B, intravenous drug abuse, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. HCV-infected women pose a risk to their sex partners; infected pregnant women can transmit the virus to their baby.

Unlike hepatitis A and hepatitis B, immunoprophylaxis is not available for hepatitis C. That reality is what makes the study by Jacobsen and colleagues so compelling: They have clearly demonstrated that multi-agent antiviral therapy might be able to truly cure this infection.

The lesson here for ObGyns? Screen at-risk patients and then refer the hepatitis C-seropositive ones to a specialist in gastroenterology, who can determine candidacy for one of the new treatment regimens.

Clearly, the prognosis for people who have hepatitis C is much better today than it was 20 years ago.

For how long should chorioamnionitis be treated?

Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(6):1102-1105.

The authors conducted a retrospective review of 423 women who had been treated for chorioamnionitis at the University of Florida from 2005 to 2009.

Patients had been given IV ampicillin (2 g every 6 h) plus IV gentamicin (1.5 mg/kg every 8 h) as soon as the diagnosis of chorioamnionitis was established; postpartum, they were given only the one next scheduled dose of each antibiotic. Patients who had a cesarean received either metronidazole (500 mg) or clindamycin (900 mg) immediately after cord clamping to enhance coverage of anaerobic organisms.

The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as persistent fever requiring continued antibiotics, surgical intervention, or administration of heparin for septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis.

Findings. Here is a breakdown of what the investigators found regarding the 282 women who delivered vaginally and the 141 who underwent cesarean delivery:

- Overall, 399 of the patients (94%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 92% and 96%) were treated successfully; 24 (6%; 95% CI, 3.7% and 8.3%) failed short-course treatment

- Of the 282 patients who delivered vaginally, 279 (99%; 95% CI, 98% and 100%) were cured with short-term therapy

- Of the 141 who delivered by cesarean, 120 (85%; 95% CI, 79% and 91%) were cured (P<.001).

- Seventeen of the total treatment failures had endometritis and responded quickly to continuation of antibiotics. Of the 17 patients with endometritis, 14 had a cesarean delivery.

- Seven patients had more serious complications: four, wound infection; three, septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis. All serious complications occurred after cesarean delivery.

- Of the four patients who had a wound infection, three had labor induced by misoprostol; their BMI was 44.8, 31.1, and 48.5, respectively. The fourth had a cesarean delivery at 29 weeks for preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), chorioamnionitis, and malpresentation.

- Of the three patients who had septic pelvic-vein thrombophlebitis, two had labor induced by misoprostol. One had a BMI of 29.2; the other, 31.1. The third patient was delivered secondary to PPROM; her BMI was 40.3.

In addition, of the 21 treatment failures in the cesarean delivery group, 6 had prolonged rupture of membranes (ROM) and 10 had a BMI greater than 30. Six patients had both prolonged ROM and were obese or morbidly obese.

Of the 120 women who had a cesarean delivery and were treated successfully, 3 had prolonged ROM and 39 had a BMI greater than 30. None had both prolonged ROM and a BMI greater than 30.

Last, the difference between treatment failures and treatment successes in regard to the frequency of prolonged ROM or a BMI greater than 30 was highly significant (P<.01).

Commentary

In most published reports of patients who have chorioamnionitis, antibiotic treatment continues until the patient is afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. This treatment approach has been based largely on expert opinion, however, not on Level-1 or Level-2 evidence.

In 2003, Edwards and Duff published a study of chorioamnionitis antibiotic regimens that compared single-dose postpartum treatment to extended treatment.2 This randomized controlled trial demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference between patients who had only a single dose of postpartum antibiotics and those who received an extended course of medication (i.e., who were treated until they had been afebrile and asymptomatic for a minimum of 24 hours) in regard to adverse outcomes (2.9% and 4.3%, respectively). The study discussed here extends and refines the observations made in the 2003 Edwards and Duff randomized controlled trial.