User login

Belimumab for pregnant women with lupus: B-cell concerns remain

The largest combined analysis of birth outcome data for women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who took belimumab (Benlysta) during pregnancy appears to indicate that the biologic is “unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects,” but the full extent of possible risk remains unknown. The drug’s effect on B cells, immune function, and infections in exposed offspring were not captured in the data, but a separate case report published after the belimumab pregnancy data report indicates that the drug does cross the placenta and builds up in the blood of the newborn, reducing B cells at birth.

Children of women with SLE have increased birth defect risks, and standard SLE therapeutic agents (for example, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil) have been implicated in birth defects and pregnancy loss, but birth defect data for biologic drugs such as belimumab are limited. While belimumab animal data revealed no evidence of fetal harm or pregnancy loss rates, there was evidence of immature and mature B-cell count reductions.

Belimumab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients aged 5 years and older with active, autoantibody-positive SLE who are taking standard therapy, and also for those with lupus nephritis.

Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases on data they compiled through March 8, 2020, from belimumab clinical trials, the Belimumab Pregnancy Registry (BPR), and postmarketing/spontaneous reports that encompassed 319 pregnancies with known outcomes.

Across 18 clinical trials with 223 live births, birth defects occurred in 4 of 72 (5.6%) belimumab-exposed pregnancies and in 0 of 9 in placebo-exposed pregnancies. Pregnancy loss (excluding elective terminations) occurred in 31.8% (35 of 110) of belimumab-exposed women and 43.8% (7 of 16) of placebo-exposed women in clinical trials. In the BPR retrospective cohort, 4.2% had pregnancy loss. Postmarketing and spontaneous reports had a pregnancy loss rate of 31.4% (43 of 137). Concomitant medications, confounding factors, and/or missing data were noted in all belimumab-exposed women in clinical trials and the BPR cohort. Dr. Petri and colleagues reported no consistent pattern of birth defects across datasets but stated: “Low numbers of exposed pregnancies, presence of confounding factors/other biases, and incomplete information preclude informed recommendations regarding risk of birth defects and pregnancy loss with belimumab use.”

In an interview, coauthor Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine and director of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said that “the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases article provides some reassurance that belimumab is unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects. It is clearly not in the risk-range for thalidomide or mycophenolate. However, due to the complexity of collecting these data, this manuscript can’t explore the full extent of possible risks. It also did not provide information about B cells, immune function, or infection risks in exposed offspring.”

A separate case report by Helle Bitter of the department of rheumatology at Sorlandet Hospital Kristiansand (Norway) in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases is the first to show transplacental passage of belimumab in humans. Other prior reports have shown such transplacental passage for monoclonal IgG antibodies (tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and rituximab). Even though the last infusion was given late in the second trimester, belimumab was present in cord serum at birth, suggesting much higher concentrations before treatment was stopped. While B-cell numbers were reduced at birth, they returned to normal ranges by 4 months post partum when they were undetectable. In the mother, B-cell numbers remained low throughout the study period extending to 7 months after delivery. The authors stated that the child had a normal vaccination response, and except for the reduced B-cell levels at birth, had no adverse effects of prenatal exposure to maternal medication through age 6 years.

“The belimumab transfer in the case report is the level that we would anticipate based on similar studies in infant/mother pairs on other IgG1 antibody biologics like adalimumab – about 60% higher than the maternal level at birth,” Dr. Clowse said. “That the baby has very low B cells at birth is worrisome to me, demonstrating the lasting effect of maternal belimumab on the infant’s immune system, even when the drug was stopped 14 weeks prior to delivery. While this single infant did not have problems with infections, with more widespread use it seems possible that infants would be found to have higher rates of infections after in utero belimumab exposure.”

The field of lupus research greatly needs controlled studies of newer biologics in pregnancy, Dr. Clowse said. “Women with active lupus in pregnancy – particularly with active lupus nephritis – continue to suffer tragic outcomes at an alarming rate. Newer treatments for lupus nephritis provide some hope that we might be able to control lupus nephritis in pregnancy more effectively. The available data suggests the risks of these medications are not so large as to make studies unreasonable. Our current data doesn’t allow us to sufficiently balance the potential risks and benefits in a way that provides clinically useful guidance. Trials of these medications, however, would enable us to identify improved treatment strategies that could result in healthier women, pregnancies, and babies.”

GlaxoSmithKline funded the study. Dr. Clowse reported receiving consulting fees and grants from UCB and GlaxoSmithKline that relate to pregnancy in women with lupus.

The largest combined analysis of birth outcome data for women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who took belimumab (Benlysta) during pregnancy appears to indicate that the biologic is “unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects,” but the full extent of possible risk remains unknown. The drug’s effect on B cells, immune function, and infections in exposed offspring were not captured in the data, but a separate case report published after the belimumab pregnancy data report indicates that the drug does cross the placenta and builds up in the blood of the newborn, reducing B cells at birth.

Children of women with SLE have increased birth defect risks, and standard SLE therapeutic agents (for example, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil) have been implicated in birth defects and pregnancy loss, but birth defect data for biologic drugs such as belimumab are limited. While belimumab animal data revealed no evidence of fetal harm or pregnancy loss rates, there was evidence of immature and mature B-cell count reductions.

Belimumab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients aged 5 years and older with active, autoantibody-positive SLE who are taking standard therapy, and also for those with lupus nephritis.

Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases on data they compiled through March 8, 2020, from belimumab clinical trials, the Belimumab Pregnancy Registry (BPR), and postmarketing/spontaneous reports that encompassed 319 pregnancies with known outcomes.

Across 18 clinical trials with 223 live births, birth defects occurred in 4 of 72 (5.6%) belimumab-exposed pregnancies and in 0 of 9 in placebo-exposed pregnancies. Pregnancy loss (excluding elective terminations) occurred in 31.8% (35 of 110) of belimumab-exposed women and 43.8% (7 of 16) of placebo-exposed women in clinical trials. In the BPR retrospective cohort, 4.2% had pregnancy loss. Postmarketing and spontaneous reports had a pregnancy loss rate of 31.4% (43 of 137). Concomitant medications, confounding factors, and/or missing data were noted in all belimumab-exposed women in clinical trials and the BPR cohort. Dr. Petri and colleagues reported no consistent pattern of birth defects across datasets but stated: “Low numbers of exposed pregnancies, presence of confounding factors/other biases, and incomplete information preclude informed recommendations regarding risk of birth defects and pregnancy loss with belimumab use.”

In an interview, coauthor Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine and director of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said that “the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases article provides some reassurance that belimumab is unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects. It is clearly not in the risk-range for thalidomide or mycophenolate. However, due to the complexity of collecting these data, this manuscript can’t explore the full extent of possible risks. It also did not provide information about B cells, immune function, or infection risks in exposed offspring.”

A separate case report by Helle Bitter of the department of rheumatology at Sorlandet Hospital Kristiansand (Norway) in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases is the first to show transplacental passage of belimumab in humans. Other prior reports have shown such transplacental passage for monoclonal IgG antibodies (tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and rituximab). Even though the last infusion was given late in the second trimester, belimumab was present in cord serum at birth, suggesting much higher concentrations before treatment was stopped. While B-cell numbers were reduced at birth, they returned to normal ranges by 4 months post partum when they were undetectable. In the mother, B-cell numbers remained low throughout the study period extending to 7 months after delivery. The authors stated that the child had a normal vaccination response, and except for the reduced B-cell levels at birth, had no adverse effects of prenatal exposure to maternal medication through age 6 years.

“The belimumab transfer in the case report is the level that we would anticipate based on similar studies in infant/mother pairs on other IgG1 antibody biologics like adalimumab – about 60% higher than the maternal level at birth,” Dr. Clowse said. “That the baby has very low B cells at birth is worrisome to me, demonstrating the lasting effect of maternal belimumab on the infant’s immune system, even when the drug was stopped 14 weeks prior to delivery. While this single infant did not have problems with infections, with more widespread use it seems possible that infants would be found to have higher rates of infections after in utero belimumab exposure.”

The field of lupus research greatly needs controlled studies of newer biologics in pregnancy, Dr. Clowse said. “Women with active lupus in pregnancy – particularly with active lupus nephritis – continue to suffer tragic outcomes at an alarming rate. Newer treatments for lupus nephritis provide some hope that we might be able to control lupus nephritis in pregnancy more effectively. The available data suggests the risks of these medications are not so large as to make studies unreasonable. Our current data doesn’t allow us to sufficiently balance the potential risks and benefits in a way that provides clinically useful guidance. Trials of these medications, however, would enable us to identify improved treatment strategies that could result in healthier women, pregnancies, and babies.”

GlaxoSmithKline funded the study. Dr. Clowse reported receiving consulting fees and grants from UCB and GlaxoSmithKline that relate to pregnancy in women with lupus.

The largest combined analysis of birth outcome data for women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who took belimumab (Benlysta) during pregnancy appears to indicate that the biologic is “unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects,” but the full extent of possible risk remains unknown. The drug’s effect on B cells, immune function, and infections in exposed offspring were not captured in the data, but a separate case report published after the belimumab pregnancy data report indicates that the drug does cross the placenta and builds up in the blood of the newborn, reducing B cells at birth.

Children of women with SLE have increased birth defect risks, and standard SLE therapeutic agents (for example, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil) have been implicated in birth defects and pregnancy loss, but birth defect data for biologic drugs such as belimumab are limited. While belimumab animal data revealed no evidence of fetal harm or pregnancy loss rates, there was evidence of immature and mature B-cell count reductions.

Belimumab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients aged 5 years and older with active, autoantibody-positive SLE who are taking standard therapy, and also for those with lupus nephritis.

Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases on data they compiled through March 8, 2020, from belimumab clinical trials, the Belimumab Pregnancy Registry (BPR), and postmarketing/spontaneous reports that encompassed 319 pregnancies with known outcomes.

Across 18 clinical trials with 223 live births, birth defects occurred in 4 of 72 (5.6%) belimumab-exposed pregnancies and in 0 of 9 in placebo-exposed pregnancies. Pregnancy loss (excluding elective terminations) occurred in 31.8% (35 of 110) of belimumab-exposed women and 43.8% (7 of 16) of placebo-exposed women in clinical trials. In the BPR retrospective cohort, 4.2% had pregnancy loss. Postmarketing and spontaneous reports had a pregnancy loss rate of 31.4% (43 of 137). Concomitant medications, confounding factors, and/or missing data were noted in all belimumab-exposed women in clinical trials and the BPR cohort. Dr. Petri and colleagues reported no consistent pattern of birth defects across datasets but stated: “Low numbers of exposed pregnancies, presence of confounding factors/other biases, and incomplete information preclude informed recommendations regarding risk of birth defects and pregnancy loss with belimumab use.”

In an interview, coauthor Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine and director of the division of rheumatology and immunology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said that “the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases article provides some reassurance that belimumab is unlikely to cause very frequent birth defects. It is clearly not in the risk-range for thalidomide or mycophenolate. However, due to the complexity of collecting these data, this manuscript can’t explore the full extent of possible risks. It also did not provide information about B cells, immune function, or infection risks in exposed offspring.”

A separate case report by Helle Bitter of the department of rheumatology at Sorlandet Hospital Kristiansand (Norway) in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases is the first to show transplacental passage of belimumab in humans. Other prior reports have shown such transplacental passage for monoclonal IgG antibodies (tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and rituximab). Even though the last infusion was given late in the second trimester, belimumab was present in cord serum at birth, suggesting much higher concentrations before treatment was stopped. While B-cell numbers were reduced at birth, they returned to normal ranges by 4 months post partum when they were undetectable. In the mother, B-cell numbers remained low throughout the study period extending to 7 months after delivery. The authors stated that the child had a normal vaccination response, and except for the reduced B-cell levels at birth, had no adverse effects of prenatal exposure to maternal medication through age 6 years.

“The belimumab transfer in the case report is the level that we would anticipate based on similar studies in infant/mother pairs on other IgG1 antibody biologics like adalimumab – about 60% higher than the maternal level at birth,” Dr. Clowse said. “That the baby has very low B cells at birth is worrisome to me, demonstrating the lasting effect of maternal belimumab on the infant’s immune system, even when the drug was stopped 14 weeks prior to delivery. While this single infant did not have problems with infections, with more widespread use it seems possible that infants would be found to have higher rates of infections after in utero belimumab exposure.”

The field of lupus research greatly needs controlled studies of newer biologics in pregnancy, Dr. Clowse said. “Women with active lupus in pregnancy – particularly with active lupus nephritis – continue to suffer tragic outcomes at an alarming rate. Newer treatments for lupus nephritis provide some hope that we might be able to control lupus nephritis in pregnancy more effectively. The available data suggests the risks of these medications are not so large as to make studies unreasonable. Our current data doesn’t allow us to sufficiently balance the potential risks and benefits in a way that provides clinically useful guidance. Trials of these medications, however, would enable us to identify improved treatment strategies that could result in healthier women, pregnancies, and babies.”

GlaxoSmithKline funded the study. Dr. Clowse reported receiving consulting fees and grants from UCB and GlaxoSmithKline that relate to pregnancy in women with lupus.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Listeria infection in pregnancy: A potentially serious foodborne illness

CASE Pregnant patient with concerning symptoms of infection

A 28-year-old primigravid woman at 26 weeks’ gestation requests evaluation because of a 3-day history of low-grade fever (38.3 °C), chills, malaise, myalgias, pain in her upper back, nausea, diarrhea, and intermittent uterine contractions. Her symptoms began 2 days after she and her husband dined at a local Mexican restaurant. She specifically recalls eating unpasteurized cheese (queso fresco). Her husband also is experiencing similar symptoms.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the fetus?

- How should this patient be treated?

Listeriosis, a potentially serious foodborne illness, is an unusual infection in pregnancy. It can cause a number of adverse effects in both the pregnant woman and her fetus, including fetal death in utero. In this article, we review the microbiology and epidemiology of Listeria infection, consider the important steps in diagnosis, and discuss treatment options and prevention measures.

The causative organism in listeriosis

Listeriosis is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive, non–spore-forming bacillus. The organism is catalase positive and oxidase negative, and it exhibits tumbling motility when grown in culture. It can grow at temperatures less than 4 °C, which facilitates foodborne transmission of the bacterium despite adequate refrigeration. Of the 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, the 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b are most likely to be associated with human infection. The major virulence factors of L monocytogenes are the internalin surface proteins and the pore-forming listeriolysin O (LLO) cytotoxin. These factors enable the organism to effectively invade host cells.1

The pathogen uses several mechanisms to evade gastrointestinal defenses prior to entry into the bloodstream. It avoids destruction in the stomach by using proton pump inhibitors to elevate the pH of gastric acid. In the duodenum, it survives the antibacterial properties of bile by secreting bile salt hydrolases, which catabolize bile salts. In addition, the cytotoxin listeriolysin S (LLS) disrupts the protective barrier created by the normal gut flora. Once the organism penetrates the gastrointestinal barriers, it disseminates through the blood and lymphatics and then infects other tissues, such as the brain and placenta.1,2

Pathogenesis of infection

The primary reservoir of Listeria is soil and decaying vegetable matter. The organism also has been isolated from animal feed, water, sewage, and many animal species. With rare exceptions, most infections in adults result from inadvertent ingestion of the organism in contaminated food. In certain high-risk occupations, such as veterinary medicine, farming, and laboratory work, infection of the skin or eye can result from direct contact with an infected animal.3

Of note, foodborne illness caused by Listeria has the third highest mortality rate of any foodborne infection, 16% compared with 35% for Vibrio vulnificus and 17% for Clostridium botulinum.2,3 The principal foods that have been linked to listeriosis include:

- soft cheeses, particularly those made from unpasteurized milk

- melon

- hot dogs

- lunch meat, such as bologna

- deli meat, especially chicken

- canned foods, such as smoked seafood, and pâté or meat spreads that are labeled “keep refrigerated”

- unpasteurized milk

- sprouts

- hummus.

In healthy adults, listeriosis is usually a short-lived illness. However, in older adults, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, the infection can be devastating. Infection in the pregnant woman also poses major danger to the developing fetus because the organism has a special predilection for placental and fetal tissue.1,3,4

Immunity to Listeria infection depends primarily on T-cell lymphokine activation of macrophages. These latter cells are responsible for clearing the bacterium from the blood. As noted above, the principal virulence factor of L monocytogenes is listeriolysin O, a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. This substance induces T-cell receptor unresponsiveness, thus interfering with the host immune response to the invading pathogen.1,3-5

Continue to: Clinical manifestations of listeriosis...

Clinical manifestations of listeriosis

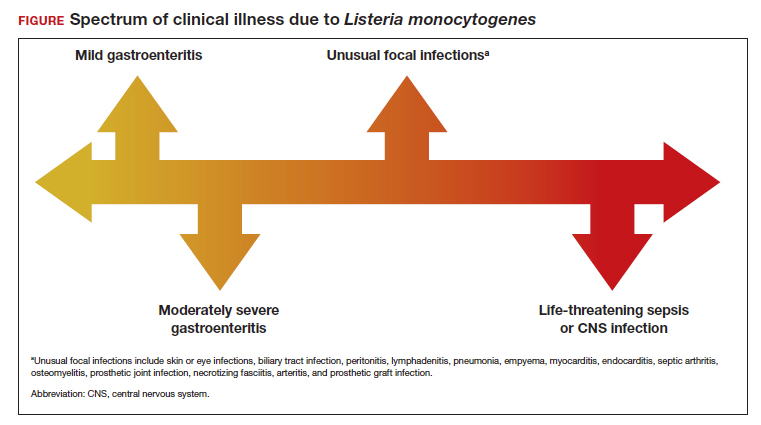

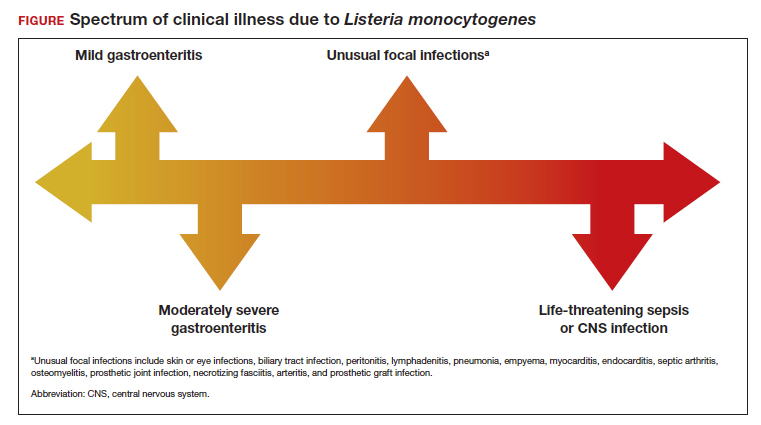

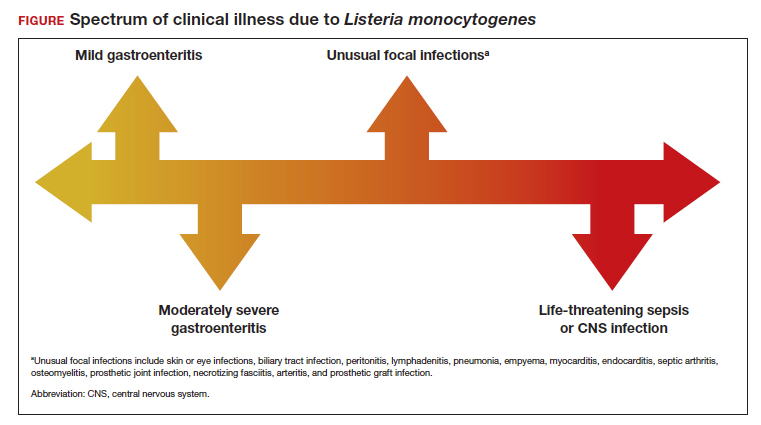

Listeria infections may present with various manifestations, depending on the degree of exposure and the underlying immunocompetence of the host (FIGURE). In its most common and simplest form, listeriosis presents as a mild to moderate gastroenteritis following exposure to contaminated food. Symptoms typically develop within 24 hours of exposure and include fever, myalgias, abdominal or back pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.5

Conversely, in immunocompromised patients, including pregnant women, listeriosis can present as life-threatening sepsis and/or central nervous system (CNS) infection (invasive infection). In this clinical setting, the mean incubation period is 11 days. The manifestations of CNS infection include meningoencephalitis, cerebritis, rhombencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain stem), brain abscess, and spinal cord abscess.5

In addition to these 2 clinical presentations, listeriosis can cause unusual focal infections as illustrated in the FIGURE. Some of these infections have unique clinical associations. For example, skin or eye infections may occur as a result of direct inoculation in veterinarians, farmers, and laboratory workers. Listeria peritonitis may occur in patients who are receiving peritoneal dialysis and in those who have cirrhosis. Prosthetic joint and graft infections, of course, may occur in patients who have had invasive procedures for implantation of grafts or prosthetic devices.5

Listeriosis is especially dangerous in pregnancy because it not only can cause serious injury to the mother and even death but it also may pose a major risk to fetal well-being. Possible perinatal complications include fetal death; preterm labor and delivery; and neonatal sepsis, meningitis, and death.5-8

Making the diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a thorough and focused history to assess for characteristic symptoms and possible Listeria exposure. Exposure should be presumed for patients who report consuming high-risk foods, especially foods recently recalled by the US Food and Drug Administration.

In the asymptomatic pregnant patient, diagnostic testing can be deferred, and the patient should be instructed to return for evaluation if symptoms develop within 2 months of exposure. However, symptomatic, febrile patients require testing. The most valuable testing modality is Gram stain and culture of blood. Gram stain typically will show gram-positive pleomorphic rods with rounded ends. Amniocentesis may be indicated if blood cultures are not definitive. Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid and a positive Gram stain are highly indicative of fetal infection. Cultures of the cerebrospinal fluid are indicated in any individual with focal neurologic findings. Stool cultures are rarely indicated.

When obtaining any of the cultures noted above, the clinician should alert the microbiologist of the concern for listeriosis because L monocytogenes can be confused with common contaminants, such as diphtheroids.5-9

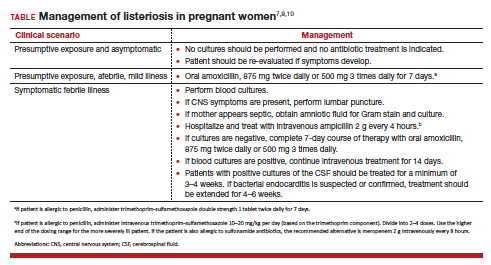

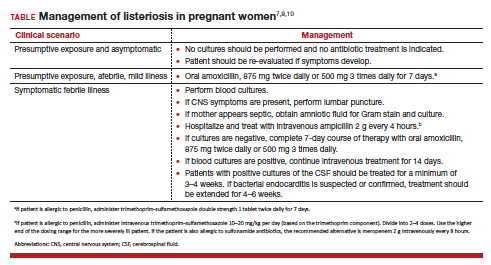

Treatment and follow-up

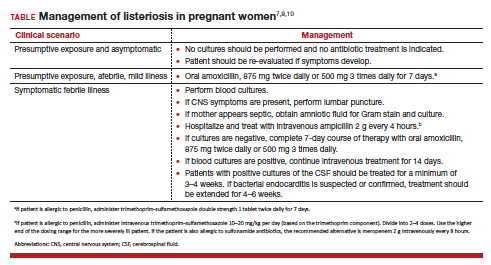

The treatment of listeriosis in pregnancy depends on the severity of the infection and the immune status of the mother. The TABLE offers several different clinical scenarios and the appropriate treatment for each. As noted, several scenarios may require cultures of the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and amniotic fluid.7,9,10

Following treatment of the mother, serial ultrasound examinations should be performed to monitor fetal growth, CNS anatomy, placental morphology, amniotic fluid volume, and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry. In the presence of fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, or abnormal Doppler velocimetry, biophysical profile testing should be performed. After delivery, the placenta should be examined carefully for histologic evidence of Listeria infection, such as miliary abscesses, and cultured for the bacterium.7-9

Prevention measures

Conservative measures for prevention of Listeria infection in pregnant women include the following7,10-12:

- Refrigerate milk and milk products at 40 °F (4.4 °C).

- Thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources.

- Wash raw vegetables carefully before eating.

- Keep uncooked meats separate from cooked meats and vegetables.

- Do not consume any beverages or foods made from unpasteurized milk.

- After handling uncooked foods, carefully wash all utensils and hands.

- Avoid all soft cheeses, such as Mexican-style feta, Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese, even if they are supposedly made from pasteurized milk.

- Reheat until steaming hot all leftover foods or ready-to-eat foods, such as hot dogs.

- Do not let juice from hot dogs or lunch meat packages drip onto other foods, utensils, or food preparation surfaces.

- Do not store opened hot dog packages in the refrigerator for more than 1 week. Do not store unopened packages for longer than 2 weeks.

- Do not store unopened lunch and deli meat packages in the refrigerator for longer than 2 weeks. Do not store opened packages for longer than 3 to 5 days.

- If other immunosuppressive conditions are present in combination with pregnancy, thoroughly heat cold cuts before eating.

- Do not eat raw or even lightly cooked sprouts of any kind. Cook sprouts thoroughly. Rinsing sprouts will not remove Listeria organisms.

- Do not eat refrigerated pâté or meat spreads from a deli counter or the refrigerated section of a grocery store.

- Canned or shelf-stable pâté and meat spreads are safe to eat, but be sure to refrigerate them after opening the packages.

- Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood. Canned or shelf-stable seafood, particularly when incorporated into a casserole, is safe to eat.

- Eat cut melon immediately. Refrigerate uneaten melon quickly if not eaten. Discard cut melon that is left at room temperature for more than 4 hours.

CASE Diagnosis made and prompt treatment initiated

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is listeriosis. Because the patient is moderately ill and experiencing uterine contractions, she should be hospitalized and monitored for progressive cervical dilation. Blood cultures should be obtained to identify L monocytogenes. In addition, an amniocentesis should be performed, and the amniotic fluid should be cultured for this microorganism. Stool culture and culture of the cerebrospinal fluid are not indicated. The patient should be treated with intravenous ampicillin, 2 g every 4 hours for 14 days. If she is allergic to penicillin, the alternative drug is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 8 to 10 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses, for 14 days. Prompt and effective treatment of the mother should prevent infection in the fetus and newborn. ●

- Listeriosis is primarily a foodborne illness caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive bacillus.

- Pregnant women, particularly those who are immunocompromised, are especially susceptible to Listeria infection.

- Foods that pose particular risk of transmitting infection include fresh unpasteurized cheeses, processed meats such as hot dogs, refrigerated pâté and meat spreads, refrigerated smoked seafood, unpasteurized milk, and unwashed raw produce.

- The infection may range from a mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening sepsis and meningitis.

- Listeriosis may cause early and late-onset neonatal infection that presents as either meningitis or sepsis.

- Blood and amniotic fluid cultures are essential to diagnose maternal infection. Stool cultures usually are not indicated.

- Mildly symptomatic but afebrile patients do not require treatment.

- Febrile symptomatic patients should be treated with either intravenous ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:32-46. doi:10.1038/nnrmicro.2017.126.

- Johnson JE, Mylonakis E. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:2543-2549.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?sectionName=CLINICAL%20EPIDEMIOLOGY&topicRef=1277&anchor=H4&source=see_link#H4

- Cherubin CE, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN, et al. Epidemiological spectrum and current treatment of listeriosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1108-1114.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-listeriamonocytogenes-infection

- Boucher M, Yonekura ML. Perinatal listeriosis (early-onset): correlation of antenatal manifestations and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:593-597.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 614: management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1241-1244.

- Rouse DJ, Keimig TW, Riley LE, et al. Case 16-2016. A 31-year-old pregnant woman with fever. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2076-2083.

- Craig AM, Dotters-Katz S, Kuller JA, et al. Listeriosis in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74: 362-368.

- Gelfand MS, Thompson JL, Swamy GK. Treatment and prevention of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?topicRef=1280&source=see_link

- Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ, Jones TF, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Networking Group. Reduction in the incidence of invasive listeriosis in Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network sites, 1996-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:513-520.

- MacDonald PDM, Whitwan RE, Boggs JD, et al. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:677-682.

CASE Pregnant patient with concerning symptoms of infection

A 28-year-old primigravid woman at 26 weeks’ gestation requests evaluation because of a 3-day history of low-grade fever (38.3 °C), chills, malaise, myalgias, pain in her upper back, nausea, diarrhea, and intermittent uterine contractions. Her symptoms began 2 days after she and her husband dined at a local Mexican restaurant. She specifically recalls eating unpasteurized cheese (queso fresco). Her husband also is experiencing similar symptoms.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the fetus?

- How should this patient be treated?

Listeriosis, a potentially serious foodborne illness, is an unusual infection in pregnancy. It can cause a number of adverse effects in both the pregnant woman and her fetus, including fetal death in utero. In this article, we review the microbiology and epidemiology of Listeria infection, consider the important steps in diagnosis, and discuss treatment options and prevention measures.

The causative organism in listeriosis

Listeriosis is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive, non–spore-forming bacillus. The organism is catalase positive and oxidase negative, and it exhibits tumbling motility when grown in culture. It can grow at temperatures less than 4 °C, which facilitates foodborne transmission of the bacterium despite adequate refrigeration. Of the 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, the 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b are most likely to be associated with human infection. The major virulence factors of L monocytogenes are the internalin surface proteins and the pore-forming listeriolysin O (LLO) cytotoxin. These factors enable the organism to effectively invade host cells.1

The pathogen uses several mechanisms to evade gastrointestinal defenses prior to entry into the bloodstream. It avoids destruction in the stomach by using proton pump inhibitors to elevate the pH of gastric acid. In the duodenum, it survives the antibacterial properties of bile by secreting bile salt hydrolases, which catabolize bile salts. In addition, the cytotoxin listeriolysin S (LLS) disrupts the protective barrier created by the normal gut flora. Once the organism penetrates the gastrointestinal barriers, it disseminates through the blood and lymphatics and then infects other tissues, such as the brain and placenta.1,2

Pathogenesis of infection

The primary reservoir of Listeria is soil and decaying vegetable matter. The organism also has been isolated from animal feed, water, sewage, and many animal species. With rare exceptions, most infections in adults result from inadvertent ingestion of the organism in contaminated food. In certain high-risk occupations, such as veterinary medicine, farming, and laboratory work, infection of the skin or eye can result from direct contact with an infected animal.3

Of note, foodborne illness caused by Listeria has the third highest mortality rate of any foodborne infection, 16% compared with 35% for Vibrio vulnificus and 17% for Clostridium botulinum.2,3 The principal foods that have been linked to listeriosis include:

- soft cheeses, particularly those made from unpasteurized milk

- melon

- hot dogs

- lunch meat, such as bologna

- deli meat, especially chicken

- canned foods, such as smoked seafood, and pâté or meat spreads that are labeled “keep refrigerated”

- unpasteurized milk

- sprouts

- hummus.

In healthy adults, listeriosis is usually a short-lived illness. However, in older adults, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, the infection can be devastating. Infection in the pregnant woman also poses major danger to the developing fetus because the organism has a special predilection for placental and fetal tissue.1,3,4

Immunity to Listeria infection depends primarily on T-cell lymphokine activation of macrophages. These latter cells are responsible for clearing the bacterium from the blood. As noted above, the principal virulence factor of L monocytogenes is listeriolysin O, a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. This substance induces T-cell receptor unresponsiveness, thus interfering with the host immune response to the invading pathogen.1,3-5

Continue to: Clinical manifestations of listeriosis...

Clinical manifestations of listeriosis

Listeria infections may present with various manifestations, depending on the degree of exposure and the underlying immunocompetence of the host (FIGURE). In its most common and simplest form, listeriosis presents as a mild to moderate gastroenteritis following exposure to contaminated food. Symptoms typically develop within 24 hours of exposure and include fever, myalgias, abdominal or back pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.5

Conversely, in immunocompromised patients, including pregnant women, listeriosis can present as life-threatening sepsis and/or central nervous system (CNS) infection (invasive infection). In this clinical setting, the mean incubation period is 11 days. The manifestations of CNS infection include meningoencephalitis, cerebritis, rhombencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain stem), brain abscess, and spinal cord abscess.5

In addition to these 2 clinical presentations, listeriosis can cause unusual focal infections as illustrated in the FIGURE. Some of these infections have unique clinical associations. For example, skin or eye infections may occur as a result of direct inoculation in veterinarians, farmers, and laboratory workers. Listeria peritonitis may occur in patients who are receiving peritoneal dialysis and in those who have cirrhosis. Prosthetic joint and graft infections, of course, may occur in patients who have had invasive procedures for implantation of grafts or prosthetic devices.5

Listeriosis is especially dangerous in pregnancy because it not only can cause serious injury to the mother and even death but it also may pose a major risk to fetal well-being. Possible perinatal complications include fetal death; preterm labor and delivery; and neonatal sepsis, meningitis, and death.5-8

Making the diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a thorough and focused history to assess for characteristic symptoms and possible Listeria exposure. Exposure should be presumed for patients who report consuming high-risk foods, especially foods recently recalled by the US Food and Drug Administration.

In the asymptomatic pregnant patient, diagnostic testing can be deferred, and the patient should be instructed to return for evaluation if symptoms develop within 2 months of exposure. However, symptomatic, febrile patients require testing. The most valuable testing modality is Gram stain and culture of blood. Gram stain typically will show gram-positive pleomorphic rods with rounded ends. Amniocentesis may be indicated if blood cultures are not definitive. Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid and a positive Gram stain are highly indicative of fetal infection. Cultures of the cerebrospinal fluid are indicated in any individual with focal neurologic findings. Stool cultures are rarely indicated.

When obtaining any of the cultures noted above, the clinician should alert the microbiologist of the concern for listeriosis because L monocytogenes can be confused with common contaminants, such as diphtheroids.5-9

Treatment and follow-up

The treatment of listeriosis in pregnancy depends on the severity of the infection and the immune status of the mother. The TABLE offers several different clinical scenarios and the appropriate treatment for each. As noted, several scenarios may require cultures of the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and amniotic fluid.7,9,10

Following treatment of the mother, serial ultrasound examinations should be performed to monitor fetal growth, CNS anatomy, placental morphology, amniotic fluid volume, and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry. In the presence of fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, or abnormal Doppler velocimetry, biophysical profile testing should be performed. After delivery, the placenta should be examined carefully for histologic evidence of Listeria infection, such as miliary abscesses, and cultured for the bacterium.7-9

Prevention measures

Conservative measures for prevention of Listeria infection in pregnant women include the following7,10-12:

- Refrigerate milk and milk products at 40 °F (4.4 °C).

- Thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources.

- Wash raw vegetables carefully before eating.

- Keep uncooked meats separate from cooked meats and vegetables.

- Do not consume any beverages or foods made from unpasteurized milk.

- After handling uncooked foods, carefully wash all utensils and hands.

- Avoid all soft cheeses, such as Mexican-style feta, Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese, even if they are supposedly made from pasteurized milk.

- Reheat until steaming hot all leftover foods or ready-to-eat foods, such as hot dogs.

- Do not let juice from hot dogs or lunch meat packages drip onto other foods, utensils, or food preparation surfaces.

- Do not store opened hot dog packages in the refrigerator for more than 1 week. Do not store unopened packages for longer than 2 weeks.

- Do not store unopened lunch and deli meat packages in the refrigerator for longer than 2 weeks. Do not store opened packages for longer than 3 to 5 days.

- If other immunosuppressive conditions are present in combination with pregnancy, thoroughly heat cold cuts before eating.

- Do not eat raw or even lightly cooked sprouts of any kind. Cook sprouts thoroughly. Rinsing sprouts will not remove Listeria organisms.

- Do not eat refrigerated pâté or meat spreads from a deli counter or the refrigerated section of a grocery store.

- Canned or shelf-stable pâté and meat spreads are safe to eat, but be sure to refrigerate them after opening the packages.

- Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood. Canned or shelf-stable seafood, particularly when incorporated into a casserole, is safe to eat.

- Eat cut melon immediately. Refrigerate uneaten melon quickly if not eaten. Discard cut melon that is left at room temperature for more than 4 hours.

CASE Diagnosis made and prompt treatment initiated

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is listeriosis. Because the patient is moderately ill and experiencing uterine contractions, she should be hospitalized and monitored for progressive cervical dilation. Blood cultures should be obtained to identify L monocytogenes. In addition, an amniocentesis should be performed, and the amniotic fluid should be cultured for this microorganism. Stool culture and culture of the cerebrospinal fluid are not indicated. The patient should be treated with intravenous ampicillin, 2 g every 4 hours for 14 days. If she is allergic to penicillin, the alternative drug is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 8 to 10 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses, for 14 days. Prompt and effective treatment of the mother should prevent infection in the fetus and newborn. ●

- Listeriosis is primarily a foodborne illness caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive bacillus.

- Pregnant women, particularly those who are immunocompromised, are especially susceptible to Listeria infection.

- Foods that pose particular risk of transmitting infection include fresh unpasteurized cheeses, processed meats such as hot dogs, refrigerated pâté and meat spreads, refrigerated smoked seafood, unpasteurized milk, and unwashed raw produce.

- The infection may range from a mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening sepsis and meningitis.

- Listeriosis may cause early and late-onset neonatal infection that presents as either meningitis or sepsis.

- Blood and amniotic fluid cultures are essential to diagnose maternal infection. Stool cultures usually are not indicated.

- Mildly symptomatic but afebrile patients do not require treatment.

- Febrile symptomatic patients should be treated with either intravenous ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

CASE Pregnant patient with concerning symptoms of infection

A 28-year-old primigravid woman at 26 weeks’ gestation requests evaluation because of a 3-day history of low-grade fever (38.3 °C), chills, malaise, myalgias, pain in her upper back, nausea, diarrhea, and intermittent uterine contractions. Her symptoms began 2 days after she and her husband dined at a local Mexican restaurant. She specifically recalls eating unpasteurized cheese (queso fresco). Her husband also is experiencing similar symptoms.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis?

- Does this infection pose a risk to the fetus?

- How should this patient be treated?

Listeriosis, a potentially serious foodborne illness, is an unusual infection in pregnancy. It can cause a number of adverse effects in both the pregnant woman and her fetus, including fetal death in utero. In this article, we review the microbiology and epidemiology of Listeria infection, consider the important steps in diagnosis, and discuss treatment options and prevention measures.

The causative organism in listeriosis

Listeriosis is caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive, non–spore-forming bacillus. The organism is catalase positive and oxidase negative, and it exhibits tumbling motility when grown in culture. It can grow at temperatures less than 4 °C, which facilitates foodborne transmission of the bacterium despite adequate refrigeration. Of the 13 serotypes of L monocytogenes, the 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b are most likely to be associated with human infection. The major virulence factors of L monocytogenes are the internalin surface proteins and the pore-forming listeriolysin O (LLO) cytotoxin. These factors enable the organism to effectively invade host cells.1

The pathogen uses several mechanisms to evade gastrointestinal defenses prior to entry into the bloodstream. It avoids destruction in the stomach by using proton pump inhibitors to elevate the pH of gastric acid. In the duodenum, it survives the antibacterial properties of bile by secreting bile salt hydrolases, which catabolize bile salts. In addition, the cytotoxin listeriolysin S (LLS) disrupts the protective barrier created by the normal gut flora. Once the organism penetrates the gastrointestinal barriers, it disseminates through the blood and lymphatics and then infects other tissues, such as the brain and placenta.1,2

Pathogenesis of infection

The primary reservoir of Listeria is soil and decaying vegetable matter. The organism also has been isolated from animal feed, water, sewage, and many animal species. With rare exceptions, most infections in adults result from inadvertent ingestion of the organism in contaminated food. In certain high-risk occupations, such as veterinary medicine, farming, and laboratory work, infection of the skin or eye can result from direct contact with an infected animal.3

Of note, foodborne illness caused by Listeria has the third highest mortality rate of any foodborne infection, 16% compared with 35% for Vibrio vulnificus and 17% for Clostridium botulinum.2,3 The principal foods that have been linked to listeriosis include:

- soft cheeses, particularly those made from unpasteurized milk

- melon

- hot dogs

- lunch meat, such as bologna

- deli meat, especially chicken

- canned foods, such as smoked seafood, and pâté or meat spreads that are labeled “keep refrigerated”

- unpasteurized milk

- sprouts

- hummus.

In healthy adults, listeriosis is usually a short-lived illness. However, in older adults, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women, the infection can be devastating. Infection in the pregnant woman also poses major danger to the developing fetus because the organism has a special predilection for placental and fetal tissue.1,3,4

Immunity to Listeria infection depends primarily on T-cell lymphokine activation of macrophages. These latter cells are responsible for clearing the bacterium from the blood. As noted above, the principal virulence factor of L monocytogenes is listeriolysin O, a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. This substance induces T-cell receptor unresponsiveness, thus interfering with the host immune response to the invading pathogen.1,3-5

Continue to: Clinical manifestations of listeriosis...

Clinical manifestations of listeriosis

Listeria infections may present with various manifestations, depending on the degree of exposure and the underlying immunocompetence of the host (FIGURE). In its most common and simplest form, listeriosis presents as a mild to moderate gastroenteritis following exposure to contaminated food. Symptoms typically develop within 24 hours of exposure and include fever, myalgias, abdominal or back pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.5

Conversely, in immunocompromised patients, including pregnant women, listeriosis can present as life-threatening sepsis and/or central nervous system (CNS) infection (invasive infection). In this clinical setting, the mean incubation period is 11 days. The manifestations of CNS infection include meningoencephalitis, cerebritis, rhombencephalitis (infection and inflammation of the brain stem), brain abscess, and spinal cord abscess.5

In addition to these 2 clinical presentations, listeriosis can cause unusual focal infections as illustrated in the FIGURE. Some of these infections have unique clinical associations. For example, skin or eye infections may occur as a result of direct inoculation in veterinarians, farmers, and laboratory workers. Listeria peritonitis may occur in patients who are receiving peritoneal dialysis and in those who have cirrhosis. Prosthetic joint and graft infections, of course, may occur in patients who have had invasive procedures for implantation of grafts or prosthetic devices.5

Listeriosis is especially dangerous in pregnancy because it not only can cause serious injury to the mother and even death but it also may pose a major risk to fetal well-being. Possible perinatal complications include fetal death; preterm labor and delivery; and neonatal sepsis, meningitis, and death.5-8

Making the diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a thorough and focused history to assess for characteristic symptoms and possible Listeria exposure. Exposure should be presumed for patients who report consuming high-risk foods, especially foods recently recalled by the US Food and Drug Administration.

In the asymptomatic pregnant patient, diagnostic testing can be deferred, and the patient should be instructed to return for evaluation if symptoms develop within 2 months of exposure. However, symptomatic, febrile patients require testing. The most valuable testing modality is Gram stain and culture of blood. Gram stain typically will show gram-positive pleomorphic rods with rounded ends. Amniocentesis may be indicated if blood cultures are not definitive. Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid and a positive Gram stain are highly indicative of fetal infection. Cultures of the cerebrospinal fluid are indicated in any individual with focal neurologic findings. Stool cultures are rarely indicated.

When obtaining any of the cultures noted above, the clinician should alert the microbiologist of the concern for listeriosis because L monocytogenes can be confused with common contaminants, such as diphtheroids.5-9

Treatment and follow-up

The treatment of listeriosis in pregnancy depends on the severity of the infection and the immune status of the mother. The TABLE offers several different clinical scenarios and the appropriate treatment for each. As noted, several scenarios may require cultures of the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and amniotic fluid.7,9,10

Following treatment of the mother, serial ultrasound examinations should be performed to monitor fetal growth, CNS anatomy, placental morphology, amniotic fluid volume, and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry. In the presence of fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, or abnormal Doppler velocimetry, biophysical profile testing should be performed. After delivery, the placenta should be examined carefully for histologic evidence of Listeria infection, such as miliary abscesses, and cultured for the bacterium.7-9

Prevention measures

Conservative measures for prevention of Listeria infection in pregnant women include the following7,10-12:

- Refrigerate milk and milk products at 40 °F (4.4 °C).

- Thoroughly cook raw food from animal sources.

- Wash raw vegetables carefully before eating.

- Keep uncooked meats separate from cooked meats and vegetables.

- Do not consume any beverages or foods made from unpasteurized milk.

- After handling uncooked foods, carefully wash all utensils and hands.

- Avoid all soft cheeses, such as Mexican-style feta, Brie, Camembert, and blue cheese, even if they are supposedly made from pasteurized milk.

- Reheat until steaming hot all leftover foods or ready-to-eat foods, such as hot dogs.

- Do not let juice from hot dogs or lunch meat packages drip onto other foods, utensils, or food preparation surfaces.

- Do not store opened hot dog packages in the refrigerator for more than 1 week. Do not store unopened packages for longer than 2 weeks.

- Do not store unopened lunch and deli meat packages in the refrigerator for longer than 2 weeks. Do not store opened packages for longer than 3 to 5 days.

- If other immunosuppressive conditions are present in combination with pregnancy, thoroughly heat cold cuts before eating.

- Do not eat raw or even lightly cooked sprouts of any kind. Cook sprouts thoroughly. Rinsing sprouts will not remove Listeria organisms.

- Do not eat refrigerated pâté or meat spreads from a deli counter or the refrigerated section of a grocery store.

- Canned or shelf-stable pâté and meat spreads are safe to eat, but be sure to refrigerate them after opening the packages.

- Do not eat refrigerated smoked seafood. Canned or shelf-stable seafood, particularly when incorporated into a casserole, is safe to eat.

- Eat cut melon immediately. Refrigerate uneaten melon quickly if not eaten. Discard cut melon that is left at room temperature for more than 4 hours.

CASE Diagnosis made and prompt treatment initiated

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is listeriosis. Because the patient is moderately ill and experiencing uterine contractions, she should be hospitalized and monitored for progressive cervical dilation. Blood cultures should be obtained to identify L monocytogenes. In addition, an amniocentesis should be performed, and the amniotic fluid should be cultured for this microorganism. Stool culture and culture of the cerebrospinal fluid are not indicated. The patient should be treated with intravenous ampicillin, 2 g every 4 hours for 14 days. If she is allergic to penicillin, the alternative drug is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 8 to 10 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses, for 14 days. Prompt and effective treatment of the mother should prevent infection in the fetus and newborn. ●

- Listeriosis is primarily a foodborne illness caused by Listeria monocytogenes, a gram-positive bacillus.

- Pregnant women, particularly those who are immunocompromised, are especially susceptible to Listeria infection.

- Foods that pose particular risk of transmitting infection include fresh unpasteurized cheeses, processed meats such as hot dogs, refrigerated pâté and meat spreads, refrigerated smoked seafood, unpasteurized milk, and unwashed raw produce.

- The infection may range from a mild gastroenteritis to life-threatening sepsis and meningitis.

- Listeriosis may cause early and late-onset neonatal infection that presents as either meningitis or sepsis.

- Blood and amniotic fluid cultures are essential to diagnose maternal infection. Stool cultures usually are not indicated.

- Mildly symptomatic but afebrile patients do not require treatment.

- Febrile symptomatic patients should be treated with either intravenous ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:32-46. doi:10.1038/nnrmicro.2017.126.

- Johnson JE, Mylonakis E. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:2543-2549.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?sectionName=CLINICAL%20EPIDEMIOLOGY&topicRef=1277&anchor=H4&source=see_link#H4

- Cherubin CE, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN, et al. Epidemiological spectrum and current treatment of listeriosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1108-1114.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-listeriamonocytogenes-infection

- Boucher M, Yonekura ML. Perinatal listeriosis (early-onset): correlation of antenatal manifestations and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:593-597.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 614: management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1241-1244.

- Rouse DJ, Keimig TW, Riley LE, et al. Case 16-2016. A 31-year-old pregnant woman with fever. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2076-2083.

- Craig AM, Dotters-Katz S, Kuller JA, et al. Listeriosis in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74: 362-368.

- Gelfand MS, Thompson JL, Swamy GK. Treatment and prevention of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?topicRef=1280&source=see_link

- Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ, Jones TF, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Networking Group. Reduction in the incidence of invasive listeriosis in Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network sites, 1996-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:513-520.

- MacDonald PDM, Whitwan RE, Boggs JD, et al. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:677-682.

- Radoshevich L, Cossart P. Listeria monocytogenes: towards a complete picture of its physiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:32-46. doi:10.1038/nnrmicro.2017.126.

- Johnson JE, Mylonakis E. Listeria monocytogenes. In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:2543-2549.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?sectionName=CLINICAL%20EPIDEMIOLOGY&topicRef=1277&anchor=H4&source=see_link#H4

- Cherubin CE, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN, et al. Epidemiological spectrum and current treatment of listeriosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1108-1114.

- Gelfand MS, Swamy GK, Thompson JL. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-listeriamonocytogenes-infection

- Boucher M, Yonekura ML. Perinatal listeriosis (early-onset): correlation of antenatal manifestations and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:593-597.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 614: management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1241-1244.

- Rouse DJ, Keimig TW, Riley LE, et al. Case 16-2016. A 31-year-old pregnant woman with fever. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2076-2083.

- Craig AM, Dotters-Katz S, Kuller JA, et al. Listeriosis in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74: 362-368.

- Gelfand MS, Thompson JL, Swamy GK. Treatment and prevention of Listeria monocytogenes infection. UpToDate. Updated August 23, 2022. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-of-listeria-monocytogenes-infection?topicRef=1280&source=see_link

- Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ, Jones TF, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Networking Group. Reduction in the incidence of invasive listeriosis in Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network sites, 1996-2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:513-520.

- MacDonald PDM, Whitwan RE, Boggs JD, et al. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:677-682.

State quality initiative can reduce postpartum hemorrhage and maternal morbidity

A statewide quality initiative can improve severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), a modeling analysis found. Such measures could potentially provide savings to birthing hospitals, according to the California cost-effectiveness study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A team led by Eric C. Wiesehan, MHA, MBA, a PhD candidate in health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, examined the effects of the safety initiative of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in a theoretical cohort of 480,000 births across a mix of hospital settings and sizes. The CMQCC developed a PPH toolkit and quality-improvement protocol to increase recognition, measurement, and timely response to PPH.

Drawing retrospectively on a large 2017 California implementation study, the simulation estimated that collaborative implementation of the CMQCC added 182 quality-adjusted life-years (0.000379 per birth) by averting 913 cases of SMM, 28 emergency hysterectomies, and one maternal mortality. Additionally, it saved $9 million ($17.78 per birth) owing to avoided SMM costs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pregnancy-related maternal deaths in the United States have increased from 7.2 per 100,000 live births to 16.9 per 100,000 live births over the past 20 years, making it the only country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development with rising rates of maternal mortality. PPH accounts for 11% of maternal deaths.

As to the study’s broader applicability, Dr. Wiesehan said in an interview, “findings of effectiveness in terms of reducing PPH-related SMM are well known outside of California. In terms of costs, however, it is more of an unknown how much is generalizable. It would go a long way if another state quality care collaborative implementing such a project recorded costs prospectively. Prospective costing, particularly microcosting, would be optimal to precisely place where the most, or least, value of this quality improvement project is achieved.”

Studies of PPH safety programs in other U.S. jurisdictions showing reductions in blood transfusions and maternal morbidities suggest the current findings are relevant to a range of hospital settings and regions. “With state perinatal collaboratives already in 47 states, examination of implementation of the PPH-SMM reduction initiative within additional collaboratives would add further robustness to our findings,” the authors wrote.

In 2022, a New York City hospital study reported that learning collaboratives that optimize practice and raise staff awareness could be important tools for improving maternal outcomes.

Still to be answered, said Dr. Wiesehan, are questions about the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of the quality initiative project beyond the early pre/post periods.

The authors indicated no specific funding for the study and had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

A statewide quality initiative can improve severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), a modeling analysis found. Such measures could potentially provide savings to birthing hospitals, according to the California cost-effectiveness study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A team led by Eric C. Wiesehan, MHA, MBA, a PhD candidate in health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, examined the effects of the safety initiative of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in a theoretical cohort of 480,000 births across a mix of hospital settings and sizes. The CMQCC developed a PPH toolkit and quality-improvement protocol to increase recognition, measurement, and timely response to PPH.

Drawing retrospectively on a large 2017 California implementation study, the simulation estimated that collaborative implementation of the CMQCC added 182 quality-adjusted life-years (0.000379 per birth) by averting 913 cases of SMM, 28 emergency hysterectomies, and one maternal mortality. Additionally, it saved $9 million ($17.78 per birth) owing to avoided SMM costs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pregnancy-related maternal deaths in the United States have increased from 7.2 per 100,000 live births to 16.9 per 100,000 live births over the past 20 years, making it the only country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development with rising rates of maternal mortality. PPH accounts for 11% of maternal deaths.

As to the study’s broader applicability, Dr. Wiesehan said in an interview, “findings of effectiveness in terms of reducing PPH-related SMM are well known outside of California. In terms of costs, however, it is more of an unknown how much is generalizable. It would go a long way if another state quality care collaborative implementing such a project recorded costs prospectively. Prospective costing, particularly microcosting, would be optimal to precisely place where the most, or least, value of this quality improvement project is achieved.”

Studies of PPH safety programs in other U.S. jurisdictions showing reductions in blood transfusions and maternal morbidities suggest the current findings are relevant to a range of hospital settings and regions. “With state perinatal collaboratives already in 47 states, examination of implementation of the PPH-SMM reduction initiative within additional collaboratives would add further robustness to our findings,” the authors wrote.

In 2022, a New York City hospital study reported that learning collaboratives that optimize practice and raise staff awareness could be important tools for improving maternal outcomes.

Still to be answered, said Dr. Wiesehan, are questions about the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of the quality initiative project beyond the early pre/post periods.

The authors indicated no specific funding for the study and had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

A statewide quality initiative can improve severe maternal morbidity (SMM) and reduce the incidence of maternal morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), a modeling analysis found. Such measures could potentially provide savings to birthing hospitals, according to the California cost-effectiveness study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A team led by Eric C. Wiesehan, MHA, MBA, a PhD candidate in health policy at Stanford (Calif.) University, examined the effects of the safety initiative of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) in a theoretical cohort of 480,000 births across a mix of hospital settings and sizes. The CMQCC developed a PPH toolkit and quality-improvement protocol to increase recognition, measurement, and timely response to PPH.

Drawing retrospectively on a large 2017 California implementation study, the simulation estimated that collaborative implementation of the CMQCC added 182 quality-adjusted life-years (0.000379 per birth) by averting 913 cases of SMM, 28 emergency hysterectomies, and one maternal mortality. Additionally, it saved $9 million ($17.78 per birth) owing to avoided SMM costs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pregnancy-related maternal deaths in the United States have increased from 7.2 per 100,000 live births to 16.9 per 100,000 live births over the past 20 years, making it the only country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development with rising rates of maternal mortality. PPH accounts for 11% of maternal deaths.

As to the study’s broader applicability, Dr. Wiesehan said in an interview, “findings of effectiveness in terms of reducing PPH-related SMM are well known outside of California. In terms of costs, however, it is more of an unknown how much is generalizable. It would go a long way if another state quality care collaborative implementing such a project recorded costs prospectively. Prospective costing, particularly microcosting, would be optimal to precisely place where the most, or least, value of this quality improvement project is achieved.”

Studies of PPH safety programs in other U.S. jurisdictions showing reductions in blood transfusions and maternal morbidities suggest the current findings are relevant to a range of hospital settings and regions. “With state perinatal collaboratives already in 47 states, examination of implementation of the PPH-SMM reduction initiative within additional collaboratives would add further robustness to our findings,” the authors wrote.

In 2022, a New York City hospital study reported that learning collaboratives that optimize practice and raise staff awareness could be important tools for improving maternal outcomes.

Still to be answered, said Dr. Wiesehan, are questions about the long-term effectiveness and sustainability of the quality initiative project beyond the early pre/post periods.

The authors indicated no specific funding for the study and had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

FDA OKs Tdap shot in pregnancy to protect newborns from pertussis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved another Tdap vaccine option for use during pregnancy to protect newborns from whooping cough.

The agency on Jan. 9 licensed Adacel (Sanofi Pasteur) for immunization during the third trimester to prevent pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old.

The FDA in October approved a different Tdap vaccine, Boostrix (GlaxoSmithKline), for this indication. Boostrix was the first vaccine specifically approved to prevent a disease in newborns whose mothers receive the vaccine while pregnant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that women receive a dose of Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy, preferably during gestational weeks 27-36 – and ideally toward the earlier end of that window – to help protect babies from whooping cough, the respiratory tract infection caused by Bordetella pertussis.

Providing a Tdap vaccine – tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine, adsorbed – in the third trimester confers passive immunity to the baby, according to the CDC. It also reduces the likelihood that the mother will get pertussis and pass it on to the infant.

One study found that providing Tdap vaccination during gestational weeks 27-36 was 85% more effective at preventing pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old, compared with providing Tdap vaccination to mothers in the hospital postpartum.

“On average, about 1,000 infants are hospitalized and typically between 5 and 15 infants die each year in the United States due to pertussis,” according to a CDC reference page. “Most of these deaths are among infants who are too young to be protected by the childhood pertussis vaccine series that starts when infants are 2 months old.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved another Tdap vaccine option for use during pregnancy to protect newborns from whooping cough.

The agency on Jan. 9 licensed Adacel (Sanofi Pasteur) for immunization during the third trimester to prevent pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old.

The FDA in October approved a different Tdap vaccine, Boostrix (GlaxoSmithKline), for this indication. Boostrix was the first vaccine specifically approved to prevent a disease in newborns whose mothers receive the vaccine while pregnant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that women receive a dose of Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy, preferably during gestational weeks 27-36 – and ideally toward the earlier end of that window – to help protect babies from whooping cough, the respiratory tract infection caused by Bordetella pertussis.

Providing a Tdap vaccine – tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine, adsorbed – in the third trimester confers passive immunity to the baby, according to the CDC. It also reduces the likelihood that the mother will get pertussis and pass it on to the infant.

One study found that providing Tdap vaccination during gestational weeks 27-36 was 85% more effective at preventing pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old, compared with providing Tdap vaccination to mothers in the hospital postpartum.

“On average, about 1,000 infants are hospitalized and typically between 5 and 15 infants die each year in the United States due to pertussis,” according to a CDC reference page. “Most of these deaths are among infants who are too young to be protected by the childhood pertussis vaccine series that starts when infants are 2 months old.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved another Tdap vaccine option for use during pregnancy to protect newborns from whooping cough.

The agency on Jan. 9 licensed Adacel (Sanofi Pasteur) for immunization during the third trimester to prevent pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old.

The FDA in October approved a different Tdap vaccine, Boostrix (GlaxoSmithKline), for this indication. Boostrix was the first vaccine specifically approved to prevent a disease in newborns whose mothers receive the vaccine while pregnant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that women receive a dose of Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy, preferably during gestational weeks 27-36 – and ideally toward the earlier end of that window – to help protect babies from whooping cough, the respiratory tract infection caused by Bordetella pertussis.

Providing a Tdap vaccine – tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine, adsorbed – in the third trimester confers passive immunity to the baby, according to the CDC. It also reduces the likelihood that the mother will get pertussis and pass it on to the infant.

One study found that providing Tdap vaccination during gestational weeks 27-36 was 85% more effective at preventing pertussis in infants younger than 2 months old, compared with providing Tdap vaccination to mothers in the hospital postpartum.

“On average, about 1,000 infants are hospitalized and typically between 5 and 15 infants die each year in the United States due to pertussis,” according to a CDC reference page. “Most of these deaths are among infants who are too young to be protected by the childhood pertussis vaccine series that starts when infants are 2 months old.”

Racial disparities in cesarean delivery rates

CASE Patient wants to reduce her risk of cesarean delivery (CD)

A 30-year-old primigravid woman expresses concern about her increased risk for CD as a Black woman. She has been reading in the news about the increased risks of CD and birth complications, and she asks what she can do to decrease her risk of having a CD.

What is the problem?

Recently, attention has been called to the stark racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Cesarean delivery rates illustrate an area in obstetric management in which racial disparities exist. It is well known that morbidity associated with CD is much higher than morbidity associated with vaginal delivery, which begs the question of whether disparities in mode of delivery may play a role in the disparity in maternal morbidity and mortality.

In the United States, 32% of all births between 2018 and 2020 were by CD. However, only 31% of White women delivered via CD as compared with 36% of Black women and 33% of Asian women.1 In 2021, the primary CD rates were 26% for Black women, 24% for Asian women, 21% for Hispanic women, and 22% for White women.2 This racial disparity, particularly between Black and White women, has been seen across nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex (NTSV) groups as well as multiparous women with prior vaginal delivery.3,4 The disparity persists after adjusting for risk factors.

A secondary analysis of groups deemed at low risk for CD within the ARRIVE trial study group reported the adjusted relative risk of CD birth for Black women as 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03–1.42) compared with White women and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.08–1.46) for Hispanic women.5 The investigators estimated that this accounted for 15% of excess maternal morbidity.5 These studies also have shown that a disparity exists in indication for CD, with Black women more likely to have a CD for the diagnosis of nonreassuring fetal tracing while White women are more likely to have a CD for failure to progress.

Patients who undergo CD are less likely to breastfeed, and they have a more difficult recovery, increased risks of infection, thromboembolic events, and increased risks for future pregnancy. Along with increased focus on racial disparities in obstetrics outcomes within the medical community, patients also have become more attuned to these racial disparities in maternal morbidity as this has increasingly become a topic of focus within the mainstream media.

What is behind differences in mode of delivery?