User login

Split-dose oxycodone protocol reduces opioid use after cesarean

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Treatment in prison systems might lead to drop in overdose deaths

Incarceration versus treatment takes center stage in a new analysis of U.S. data from researchers in the United Kingdom.

The researchers performed an observational study looking at rates of incarceration, income, and drug-related deaths from 1983 to 2014 in the United States. They found a strong association between incarceration rates and drug-related deaths. Also, a very strong association was found between lower household income and drug-related deaths. Strikingly, in the counties with the highest incarceration rates, there was a 50% higher rate of drug deaths, reported Elias Nosrati, PhD, and associates (Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33). It is clearer every day that our opioid epidemic was in part wrought by a zealous push to change protocols on treating chronic pain. The epidemic also appears tied to well-meaning but overprescribing doctors and allegedly unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies and distributors. What we are learning through this most recent study is that another factor tied to the opioid and overdose epidemic could be incarceration.

According to the study, an increase in crime rates combined with sentencing reforms led the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons to soar from less than 200,000 in 1970 to almost 1 million in 1995. Furthermore, Dr. Nosrati and associates wrote, “Incarceration is directly associated with stigma, discrimination, poor mental health, and chronic economic hardship, all of which are linked to drug use disorders.”

Treatment for drug addiction in prison systems is rare, as is adequate mental health treatment. However, treatment for this population would likely help reduce drug overdose deaths and improve the quality of life for people who are incarcerated and their families. In the Philadelphia prison system, for example, treatment for inmates is available for opioid addiction, both with methadone and now more recently with buprenorphine (Suboxone). The Philadelphia Department of Prisons also provides cognitive-behavioral therapy. In Florida, Chapter 397 of the Florida statutes – known as the Marchman Act – provides for the involuntary (and voluntary) treatment of individuals with substance abuse problems.

The court systems in South Florida have a robust drug-diversion program, aimed at directing people facing incarceration for drug offenses into treatment instead. North Carolina has studied this issue specifically and found through a model simulation that diverting 10% of drug-abusing offenders out of incarceration into treatment would save $4.8 billion in legal costs for North Carolina counties and state legal systems. Diverting 40% of individuals would close to triple that savings.

There are striking data from programs treating individuals who are leveraged into treatment in order to maintain professional licenses. These such individuals, many of whom are physicians, airline pilots, and nurses, have a rate of sobriety of 90% or greater after 5 years. This data show that

In addition to the potential reduction in morbidity and mortality as well as the financial savings, why is treatment important? Because of societal costs. When parents or family members are put in jail for a drug charge or other charge, they leave behind a community, family, and very often children who are affected economically, emotionally, and socially. Those children in particular have higher risks of depression and PTSD. Diverting an offender into treatment or treating an incarcerated person for drug and mental health problems can change the life of a child or family member, and ultimately can change society.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Incarceration versus treatment takes center stage in a new analysis of U.S. data from researchers in the United Kingdom.

The researchers performed an observational study looking at rates of incarceration, income, and drug-related deaths from 1983 to 2014 in the United States. They found a strong association between incarceration rates and drug-related deaths. Also, a very strong association was found between lower household income and drug-related deaths. Strikingly, in the counties with the highest incarceration rates, there was a 50% higher rate of drug deaths, reported Elias Nosrati, PhD, and associates (Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33). It is clearer every day that our opioid epidemic was in part wrought by a zealous push to change protocols on treating chronic pain. The epidemic also appears tied to well-meaning but overprescribing doctors and allegedly unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies and distributors. What we are learning through this most recent study is that another factor tied to the opioid and overdose epidemic could be incarceration.

According to the study, an increase in crime rates combined with sentencing reforms led the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons to soar from less than 200,000 in 1970 to almost 1 million in 1995. Furthermore, Dr. Nosrati and associates wrote, “Incarceration is directly associated with stigma, discrimination, poor mental health, and chronic economic hardship, all of which are linked to drug use disorders.”

Treatment for drug addiction in prison systems is rare, as is adequate mental health treatment. However, treatment for this population would likely help reduce drug overdose deaths and improve the quality of life for people who are incarcerated and their families. In the Philadelphia prison system, for example, treatment for inmates is available for opioid addiction, both with methadone and now more recently with buprenorphine (Suboxone). The Philadelphia Department of Prisons also provides cognitive-behavioral therapy. In Florida, Chapter 397 of the Florida statutes – known as the Marchman Act – provides for the involuntary (and voluntary) treatment of individuals with substance abuse problems.

The court systems in South Florida have a robust drug-diversion program, aimed at directing people facing incarceration for drug offenses into treatment instead. North Carolina has studied this issue specifically and found through a model simulation that diverting 10% of drug-abusing offenders out of incarceration into treatment would save $4.8 billion in legal costs for North Carolina counties and state legal systems. Diverting 40% of individuals would close to triple that savings.

There are striking data from programs treating individuals who are leveraged into treatment in order to maintain professional licenses. These such individuals, many of whom are physicians, airline pilots, and nurses, have a rate of sobriety of 90% or greater after 5 years. This data show that

In addition to the potential reduction in morbidity and mortality as well as the financial savings, why is treatment important? Because of societal costs. When parents or family members are put in jail for a drug charge or other charge, they leave behind a community, family, and very often children who are affected economically, emotionally, and socially. Those children in particular have higher risks of depression and PTSD. Diverting an offender into treatment or treating an incarcerated person for drug and mental health problems can change the life of a child or family member, and ultimately can change society.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Incarceration versus treatment takes center stage in a new analysis of U.S. data from researchers in the United Kingdom.

The researchers performed an observational study looking at rates of incarceration, income, and drug-related deaths from 1983 to 2014 in the United States. They found a strong association between incarceration rates and drug-related deaths. Also, a very strong association was found between lower household income and drug-related deaths. Strikingly, in the counties with the highest incarceration rates, there was a 50% higher rate of drug deaths, reported Elias Nosrati, PhD, and associates (Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33). It is clearer every day that our opioid epidemic was in part wrought by a zealous push to change protocols on treating chronic pain. The epidemic also appears tied to well-meaning but overprescribing doctors and allegedly unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies and distributors. What we are learning through this most recent study is that another factor tied to the opioid and overdose epidemic could be incarceration.

According to the study, an increase in crime rates combined with sentencing reforms led the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons to soar from less than 200,000 in 1970 to almost 1 million in 1995. Furthermore, Dr. Nosrati and associates wrote, “Incarceration is directly associated with stigma, discrimination, poor mental health, and chronic economic hardship, all of which are linked to drug use disorders.”

Treatment for drug addiction in prison systems is rare, as is adequate mental health treatment. However, treatment for this population would likely help reduce drug overdose deaths and improve the quality of life for people who are incarcerated and their families. In the Philadelphia prison system, for example, treatment for inmates is available for opioid addiction, both with methadone and now more recently with buprenorphine (Suboxone). The Philadelphia Department of Prisons also provides cognitive-behavioral therapy. In Florida, Chapter 397 of the Florida statutes – known as the Marchman Act – provides for the involuntary (and voluntary) treatment of individuals with substance abuse problems.

The court systems in South Florida have a robust drug-diversion program, aimed at directing people facing incarceration for drug offenses into treatment instead. North Carolina has studied this issue specifically and found through a model simulation that diverting 10% of drug-abusing offenders out of incarceration into treatment would save $4.8 billion in legal costs for North Carolina counties and state legal systems. Diverting 40% of individuals would close to triple that savings.

There are striking data from programs treating individuals who are leveraged into treatment in order to maintain professional licenses. These such individuals, many of whom are physicians, airline pilots, and nurses, have a rate of sobriety of 90% or greater after 5 years. This data show that

In addition to the potential reduction in morbidity and mortality as well as the financial savings, why is treatment important? Because of societal costs. When parents or family members are put in jail for a drug charge or other charge, they leave behind a community, family, and very often children who are affected economically, emotionally, and socially. Those children in particular have higher risks of depression and PTSD. Diverting an offender into treatment or treating an incarcerated person for drug and mental health problems can change the life of a child or family member, and ultimately can change society.

Dr. Jorandby is chief medical officer of Lakeview Health in Jacksonville, Fla. She trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Poverty, incarceration may drive deaths from drug use

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

High rates of both incarceration and reduced household income are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the United States, based a regression analysis of several decades of data.

“More than half a million drug-related deaths have occurred in the USA in the past three and half decades, however, no studies have investigated the association between these deaths and the expansion of the incarcerated population,” wrote Elias Nosrati, PhD, of the University of Oxford (England) and colleagues.

The researchers reviewed previously unavailable data on jail and prison incarceration at the county level from the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice in New York, as well as mortality data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System. The analysis was published in the Lancet Public Health.

After adjustment for multiple confounding variables, each standard deviation in admission rates to local jails (an average of 7,018 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 1.5% increase in drug-related deaths, and each standard deviation in admission rates to state prisons (an average of 254.6 per 100,000 population) was associated with a significant 2.6% increase in drug-related deaths, reported Dr. Nosrati and colleagues.

“On average, the researchers wrote. In addition, each standard-deviation decrease in median household income was associated with a 12.8% increase in drug-related deaths within counties.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the observational nature of the study, the potential skewing of results because of missing data from some counties, and the inability to examine support for individuals released from jail or prison, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that, “when coupled with economic hardship, the operations of the prison and jail systems constitute an upstream determinant of despair, whereby regular exposures to neighborhood violence, unstable social and family relationships, and psychosocial stress trigger destructive behaviours,” they wrote.

In an accompanying comment, James LePage, PhD, wrote that current laws regarding trespassing, loitering, and vagrancy “unfairly criminalize individuals of low economic status and homeless individuals” by increasing their likelihood of interaction with the legal system and thus increasing the incarceration rate in this population.

“Future studies should focus on racial and ethnic biases in arrests and sentencing, and the subsequent effect on drug-related mortality,” wrote Dr. LePage of the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas.

Neither the researchers in the main study nor Dr. LePage had financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

FROM THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

Key clinical point: Reduced household income and increased incarceration are significantly associated with drug-related deaths in the U.S. population.

Major finding: High incarceration rates are associated with an increase in drug-related deaths of more than 50% at the county level.

Study details: The data come from a regression analysis of data from multiple institutions, including the U.S. National Vital Statistics System and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, as well as incarceration data from the Vera Institute of Justice for 2,640 U.S. counties from 1983 to 2014.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Nosrati E et al. Lancet Public Health. 2019 Jul 3;4:e326-33.

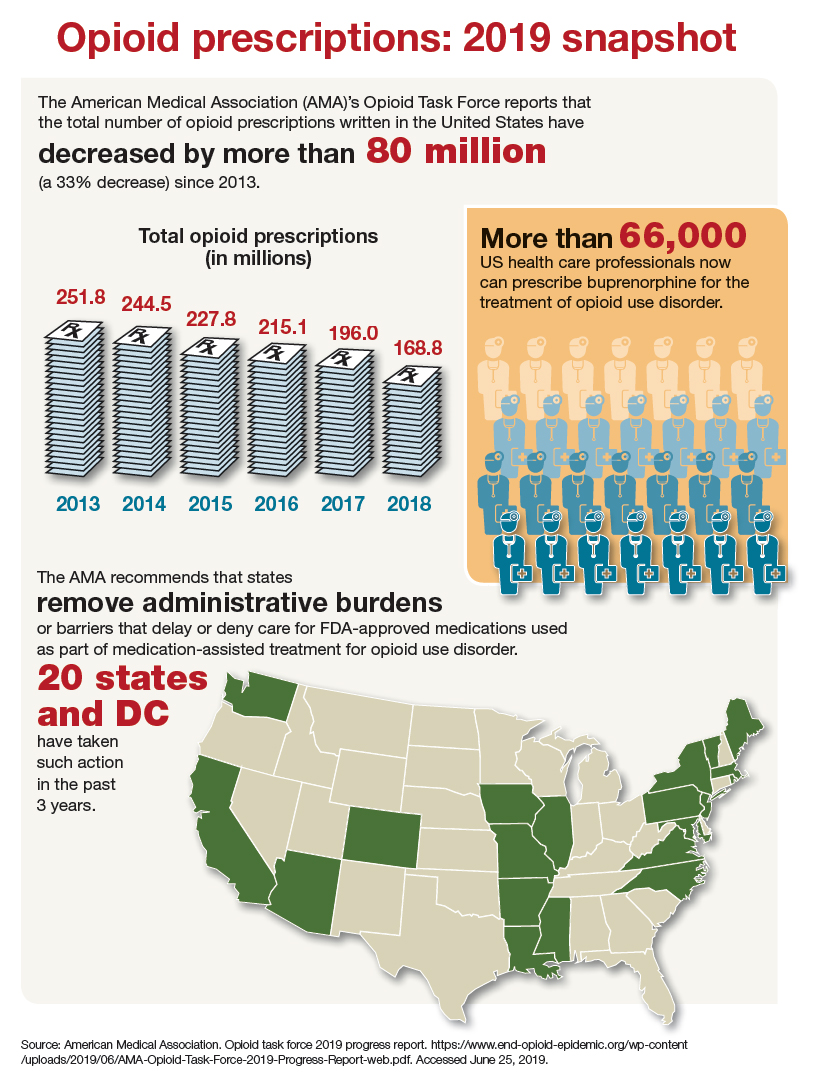

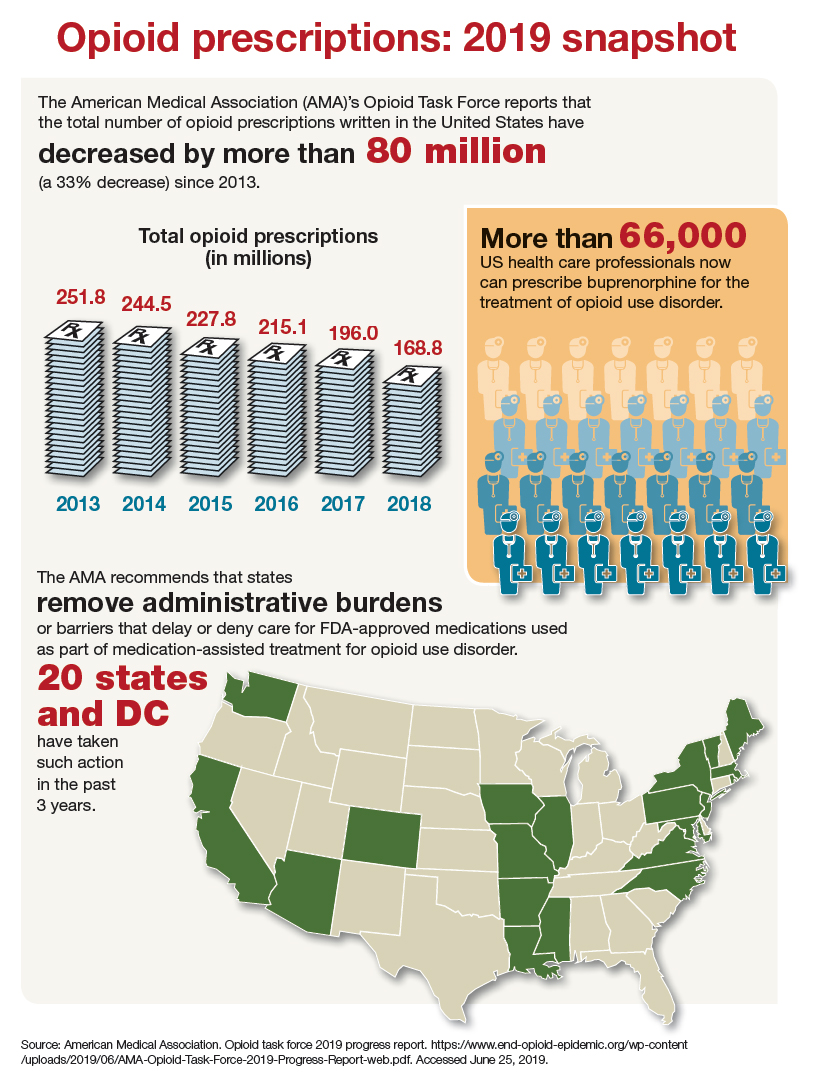

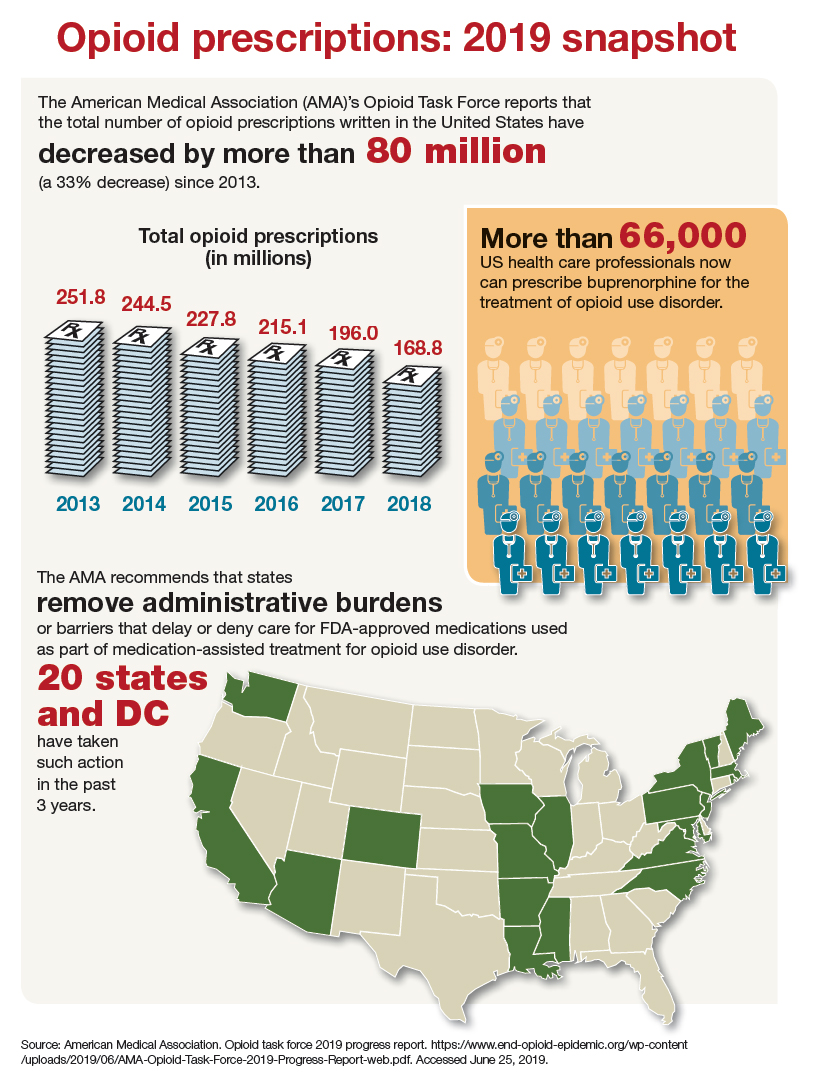

Opioid prescriptions: 2019 snapshot

Claims data suggest endometriosis ups risk of chronic opioid use

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Women with endometriosis are at increased risk of chronic opioid use, compared with those without endometriosis, based on an analysis of claims data.

The 2-year rate of chronic opioid use was 4.4% among 36,373 women with endometriosis, compared with 1.1% among 2,172,936 women without endometriosis (odds ratio, 3.94) – a finding with important implications for physician prescribing considerations, Stephanie E. Chiuve, ScD, reported at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The OR was 3.76 after adjusting for age, race, and geographic region, said Dr. Chiuve of AbbVie, North Chicago.

Notably, the prevalence of other pain conditions, depression, anxiety, abuse of substances other than opioids, immunologic disorders, and use of opioids and other medications at baseline was higher in women with endometriosis versus those without. In any year, women with endometriosis were twice as likely to fill at least one opioid prescription, and were 3.5-4 times more likely to be a chronic opioid user than were women without endometriosis, she and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the meeting.

“Up to 60% of women with endometriosis experience significant chronic pain, including dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, and dyspareunia,” they explained, adding that opioids may be prescribed for chronic pain management or for acute pain in the context of surgical procedures for endometriosis.

“This was due in part to various comorbidities that are also risk factors for chronic opioid use,” Dr. Chiuve said.

Women included in the study were aged 18-50 years (mean, 35 years), and were identified from a U.S. commercial insurance claims database and followed for 2 years after enrolling between January 2006 and December 2017. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 120 days covered by an opioid dispensing or at least 10 fills of an opioid over a 1-year period during the 2-year follow-up study.

“With a less restrictive definition of chronic opioid use [of at least 6 fills] in any given year, the OR for chronic use comparing women with endometriosis to [the referent group] was similar [OR, 3.77],” the investigators wrote. “The OR for chronic use was attenuated to 2.88 after further adjustment for comorbidities and other medication use.”

Women with endometriosis in this study also experienced higher rates of opioid-associated clinical sequelae, they noted. For example, the adjusted ORs were 17.71 for an opioid dependence diagnosis, 12.52 for opioid overdose, and 10.39 for opioid use disorder treatment in chronic versus nonchronic users of opioids.

Additionally, chronic users were more likely to be prescribed high dose opioids (aOR, 6.45) and to be coprescribed benzodiazepines and sedatives (aORs, 5.87 and 3.78, respectively).

In fact, the findings of this study – though limited by factors such as the use of prescription fills rather than intake to measure exposure, and possible misclassification of endometriosis because of a lack of billing claims or undiagnosed disease – raise concerns about harmful opioid-related outcomes and dangerous prescribing patterns, they said.

In a separate poster presentation at the meeting, the researchers reported that independent risk factors for chronic opioid use in this study population were younger age (ORs, 0.90 and 0.72 for those aged 25-35 and 35-40 years, respectively, vs. those under age 25 years); concomitant chronic pain conditions, including fibromyalgia (OR, 1.49), chronic back pain (OR, 1.55), headaches/migraines (OR, 1.49), irritable bowel syndrome (OR, 1.61), and rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.52); the use of antipsychiatric drugs, including antidepressants (OR, 2.0), antipsychotics (OR, 1.66), and benzodiazepines (OR, 1.87); and baseline opioid use (OR, 3.95).

Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race predicted lower risk of chronic opioid use (ORs, 0.56 and 0.39, respectively), they found.

“These data contribute to the knowledge of potential risks of opioid use and may inform benefit-risk decision making of opioid use among women with endometriosis for management of endometriosis and its associated pain,” they concluded.

This study was funded by AbbVie. Dr. Chiuve is an employee of AbbVie, and she reported receiving stock/stock options.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Opioids: Overprescribing, alternatives, and clinical guidance

Opioids: Overprescribing, alternatives, and clinical guidance

Optimal management of pregnant women with opioid misuse

Optimal management of postpartum and postoperative pain

Co-use of opioids, methamphetamine on rise in rural Oregon

Survey shows simultaneous use climbed from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017

SAN ANTONIO – A perceived low risk of using methamphetamine and a belief that methamphetamine helps with opioid addiction are both driving increasing levels of concurrent methamphetamine and opioid use in rural Oregon, according to recent qualitative research.

Use of methamphetamine by those who use opioids increased from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017, Gillian Leichtling, research manager at HealthInsight Oregon, said at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The highest prevalence of simultaneous use is in the western states, where 63% of opioid users also use methamphetamine, she said. Hospitalizations and overdoses related to methamphetamine have likewise increased, particularly in rural communities.

To better understand the motivations and implications of this trend, Ms. Leichtling and her colleagues conducted a survey from March 2018 to April 2019 of adults who had nonmedically used/injected opioids or methamphetamine in the past month. All participants lived in Lane or Douglas counties in southwestern Oregon, where half the land is controlled by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, and opioid overdose rates surpass that of the state average. Additional 60-minute semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted in summer 2018.

Among the 144 surveyed, 78% had used an opioid in the past month, nearly all of whom (96%) had also used methamphetamine in the past month. The interviewees included adults fairly evenly spread across ages, but most (94%) were white.

The main themes that emerged from the interviews involved the perceived benefits and consequences of those who used both opioids and methamphetamine, and the environmental circumstances that supported methamphetamine use, Ms. Leichtling explained.

Most people interviewed had their first experience with methamphetamine early in life, typically in early or mid-adolescence, she said. Two respondents, for example, first began using at 8 and 12 years old, the former learning from a preteen neighbor.

Methamphetamine’s wide availability and low cost also increased its use. In addition, methamphetamine use carries less stigma than heroin use, participants told the researchers. One person who noted the popularity of methamphetamine added: “You get treated really badly if you’re a heroin addict.”

In addition to less stigma, many of the perceived benefits of methamphetamine use related to opioids: Participants said methamphetamine “relieves opioid withdrawal, helps reduce opioid use, enhances functioning, and combines well with opioids” for a pleasurable effect, Ms. Leichtling said. Some also perceived methamphetamine as a way to reverse opioid overdose.

“I’m getting out of [the buprenorphine] program; they’re titrating me down rapidly, and so I’ve been sick for a week,” one respondent told researchers. “I’ve been doing so much more meth just to try to deflect the pain ... they’re too hard to come down from. It’s just you can’t do it without another drug ... especially if you have a job or responsibilities or kids,” they told researchers.

Another woman said she and her mother were able to come off heroin by using methamphetamine instead, and a yet another said she and her ex-boyfriend used methamphetamine to stop using opioids.

Several respondents also mentioned using methamphetamine to help them go to work, effectively put in long days, and then care for their families when they get home.

Ms. Leichtling described three main implications of the findings for interventions in rural areas. One was the need at the community level for greater access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of opioid use disorder to reduce the use of methamphetamine to taper opioid use or withdrawal.

Next, clinicians need to provide tailored treatment for the co-use of opioids and methamphetamine, and educate patients on alternatives to being dropped from medication-assisted opioid use disorder treatment. Finally, individual users need education on overdose that addresses the misconceptions and risks related to methamphetamine risk, Ms. Leichtling said.

Since the survey and interviews came only from two rural Oregon counties, the findings might not be generalizable, Ms. Leichtling said, and their study did not explore social determinants of health that might be at work.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the research. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Survey shows simultaneous use climbed from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017

Survey shows simultaneous use climbed from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017

SAN ANTONIO – A perceived low risk of using methamphetamine and a belief that methamphetamine helps with opioid addiction are both driving increasing levels of concurrent methamphetamine and opioid use in rural Oregon, according to recent qualitative research.

Use of methamphetamine by those who use opioids increased from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017, Gillian Leichtling, research manager at HealthInsight Oregon, said at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The highest prevalence of simultaneous use is in the western states, where 63% of opioid users also use methamphetamine, she said. Hospitalizations and overdoses related to methamphetamine have likewise increased, particularly in rural communities.

To better understand the motivations and implications of this trend, Ms. Leichtling and her colleagues conducted a survey from March 2018 to April 2019 of adults who had nonmedically used/injected opioids or methamphetamine in the past month. All participants lived in Lane or Douglas counties in southwestern Oregon, where half the land is controlled by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, and opioid overdose rates surpass that of the state average. Additional 60-minute semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted in summer 2018.

Among the 144 surveyed, 78% had used an opioid in the past month, nearly all of whom (96%) had also used methamphetamine in the past month. The interviewees included adults fairly evenly spread across ages, but most (94%) were white.

The main themes that emerged from the interviews involved the perceived benefits and consequences of those who used both opioids and methamphetamine, and the environmental circumstances that supported methamphetamine use, Ms. Leichtling explained.

Most people interviewed had their first experience with methamphetamine early in life, typically in early or mid-adolescence, she said. Two respondents, for example, first began using at 8 and 12 years old, the former learning from a preteen neighbor.

Methamphetamine’s wide availability and low cost also increased its use. In addition, methamphetamine use carries less stigma than heroin use, participants told the researchers. One person who noted the popularity of methamphetamine added: “You get treated really badly if you’re a heroin addict.”

In addition to less stigma, many of the perceived benefits of methamphetamine use related to opioids: Participants said methamphetamine “relieves opioid withdrawal, helps reduce opioid use, enhances functioning, and combines well with opioids” for a pleasurable effect, Ms. Leichtling said. Some also perceived methamphetamine as a way to reverse opioid overdose.

“I’m getting out of [the buprenorphine] program; they’re titrating me down rapidly, and so I’ve been sick for a week,” one respondent told researchers. “I’ve been doing so much more meth just to try to deflect the pain ... they’re too hard to come down from. It’s just you can’t do it without another drug ... especially if you have a job or responsibilities or kids,” they told researchers.

Another woman said she and her mother were able to come off heroin by using methamphetamine instead, and a yet another said she and her ex-boyfriend used methamphetamine to stop using opioids.

Several respondents also mentioned using methamphetamine to help them go to work, effectively put in long days, and then care for their families when they get home.

Ms. Leichtling described three main implications of the findings for interventions in rural areas. One was the need at the community level for greater access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of opioid use disorder to reduce the use of methamphetamine to taper opioid use or withdrawal.

Next, clinicians need to provide tailored treatment for the co-use of opioids and methamphetamine, and educate patients on alternatives to being dropped from medication-assisted opioid use disorder treatment. Finally, individual users need education on overdose that addresses the misconceptions and risks related to methamphetamine risk, Ms. Leichtling said.

Since the survey and interviews came only from two rural Oregon counties, the findings might not be generalizable, Ms. Leichtling said, and their study did not explore social determinants of health that might be at work.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the research. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – A perceived low risk of using methamphetamine and a belief that methamphetamine helps with opioid addiction are both driving increasing levels of concurrent methamphetamine and opioid use in rural Oregon, according to recent qualitative research.

Use of methamphetamine by those who use opioids increased from 19% to 34% between 2011 and 2017, Gillian Leichtling, research manager at HealthInsight Oregon, said at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The highest prevalence of simultaneous use is in the western states, where 63% of opioid users also use methamphetamine, she said. Hospitalizations and overdoses related to methamphetamine have likewise increased, particularly in rural communities.

To better understand the motivations and implications of this trend, Ms. Leichtling and her colleagues conducted a survey from March 2018 to April 2019 of adults who had nonmedically used/injected opioids or methamphetamine in the past month. All participants lived in Lane or Douglas counties in southwestern Oregon, where half the land is controlled by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, and opioid overdose rates surpass that of the state average. Additional 60-minute semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted in summer 2018.

Among the 144 surveyed, 78% had used an opioid in the past month, nearly all of whom (96%) had also used methamphetamine in the past month. The interviewees included adults fairly evenly spread across ages, but most (94%) were white.

The main themes that emerged from the interviews involved the perceived benefits and consequences of those who used both opioids and methamphetamine, and the environmental circumstances that supported methamphetamine use, Ms. Leichtling explained.

Most people interviewed had their first experience with methamphetamine early in life, typically in early or mid-adolescence, she said. Two respondents, for example, first began using at 8 and 12 years old, the former learning from a preteen neighbor.

Methamphetamine’s wide availability and low cost also increased its use. In addition, methamphetamine use carries less stigma than heroin use, participants told the researchers. One person who noted the popularity of methamphetamine added: “You get treated really badly if you’re a heroin addict.”

In addition to less stigma, many of the perceived benefits of methamphetamine use related to opioids: Participants said methamphetamine “relieves opioid withdrawal, helps reduce opioid use, enhances functioning, and combines well with opioids” for a pleasurable effect, Ms. Leichtling said. Some also perceived methamphetamine as a way to reverse opioid overdose.

“I’m getting out of [the buprenorphine] program; they’re titrating me down rapidly, and so I’ve been sick for a week,” one respondent told researchers. “I’ve been doing so much more meth just to try to deflect the pain ... they’re too hard to come down from. It’s just you can’t do it without another drug ... especially if you have a job or responsibilities or kids,” they told researchers.

Another woman said she and her mother were able to come off heroin by using methamphetamine instead, and a yet another said she and her ex-boyfriend used methamphetamine to stop using opioids.

Several respondents also mentioned using methamphetamine to help them go to work, effectively put in long days, and then care for their families when they get home.

Ms. Leichtling described three main implications of the findings for interventions in rural areas. One was the need at the community level for greater access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of opioid use disorder to reduce the use of methamphetamine to taper opioid use or withdrawal.

Next, clinicians need to provide tailored treatment for the co-use of opioids and methamphetamine, and educate patients on alternatives to being dropped from medication-assisted opioid use disorder treatment. Finally, individual users need education on overdose that addresses the misconceptions and risks related to methamphetamine risk, Ms. Leichtling said.

Since the survey and interviews came only from two rural Oregon counties, the findings might not be generalizable, Ms. Leichtling said, and their study did not explore social determinants of health that might be at work.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the research. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019