User login

Our EHRs have a drug problem

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

The “opioid epidemic” has become, perhaps, the most talked-about health crisis of the 21st century. It is a pervasive topic of discussion in the health literature and beyond, written about on the front pages of national newspapers and even mentioned in presidential state-of-the-union addresses.

As practicing physicians, we are all too familiar with the ills of chronic opioid use and have dealt with the implications of the crisis long before the issue attracted the public’s attention. In many ways, we have felt alone in bearing the burdens of caring for patients on chronic controlled substances. Until this point it has been our sacred duty to determine which patients are truly in need of those medications, and which are merely dependent on or – even worse – abusing them.

Health care providers have been largely blamed for the creation of this crisis, but we are not alone. Responsibility must also be shared by the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers, and even the government. Marketing practices, inadequate coverage of pain-relieving procedures and rehabilitation, and poorly-conceived drug policies have created an environment where it has been far too difficult to provide appropriate care for patients with chronic pain. As a result, patients who may have had an alternative to opioids were still started on these medications, and we – their physicians – have been left alone to manage the outcome.

Recently, however, health policy and public awareness have signaled a dramatic shift in the management of long-term pain medication. Significant legislation has been enacted on national, state, and local levels, and parties who are perceived to be responsible for the crisis are being held to task. For example, in August a landmark legal case was decided in an Oklahoma district court. Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals was found guilty of promoting drug addiction through false and misleading marketing and was thus ordered to pay $572 million to the state to fund drug rehabilitation programs. This is likely a harbinger of many more such decisions to come, and the industry as a whole is bracing for the worst.

Physician prescribing practices are also being carefully scrutinized by the DEA, and a significant number of new “checks and balances” have been put in place to address dependence and addiction concerns. Unfortunately, as with all sweeping reform programs, there are good – and not-so-good – aspects to these changes. In many ways, the new tools at our disposal are a powerful way of mitigating drug dependence and diversion while protecting the sanctity of our “prescription pads.” Yet, as with so many other government mandates, we are burdened with the onus of complying with the new mandates for each and every opioid prescription, while our EHRs provide little help. This means more “clicks” for us, which can feel quite burdensome. It doesn’t need to be this way. Below are two straightforward things that can and should occur in order for providers to feel unburdened and to fully embrace the changes.

PDMP integration

One of the major ways of controlling prescription opioid abuse is through effective monitoring. Forty-nine of the 50 U.S. states have developed Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), with Missouri being the only holdout (due to the politics of individual privacy concerns and conflation with gun control legislation). Most – though not all – of the states with a PDMP also mandate that physicians query a database prior to prescribing controlled substances. While noble and helpful in principle, querying a PDMP can be cumbersome, and the process is rarely integrated into the EHR workflow. Instead, physicians typically need to login to a separate website and manually transpose patient data to search the database. While most states have offered to subsidize PDMP integration with electronic records, EHR vendors have been very slow to develop the capability, leaving most physicians with no choice but to continue the aforementioned workflow. That is, if they comply at all; many well-meaning physicians have told us that they find themselves too harried to use the PDMP consistently. This reduces the value of these databases and places the physicians at significant risk. In some states, failure to query the database can lead to loss of a doctor’s medical license. It is high time that EHR vendors step up and integrate with every state’s prescription drug database.

Electronic prescribing of controlled substances

The other major milestone in prescription opioid management is the electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). This received national priority when the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was signed into federal law in October of 2018. Included in this act is a requirement that, by January of 2021, all controlled substance prescriptions covered under Medicare Part D be sent electronically. Taking this as inspiration, many states and private companies have adopted more aggressive policies, choosing to implement electronic prescription requirements prior to the 2021 deadline. In Pennsylvania, where we practice, an EPCS requirement goes into effect in October of this year (2019). National pharmacy chains have also taken a more proactive approach. Walmart, for example, has decided that it will require EPCS nationwide in all of its stores beginning in January of 2020.

Essentially physicians have no choice – if they plan to continue to prescribe controlled substances, they will need to begin doing so electronically. Unfortunately, this may not be a straightforward process. While most EHRs offer some sort of EPCS solution, it is typically far from user friendly. Setting up EPCS can be costly and incredibly time consuming, and the procedure of actually submitting controlled prescriptions can be onerous and add many extra clicks. If vendors are serious about assisting in solving the opioid crisis, they need to make streamlining the steps of EPCS a high priority.

A prescription for success

As with so many other topics we’ve written about, we face an ever-increasing burden to provide quality patient care while complying with cumbersome and often unfunded external mandates. In the case of the opioid crisis, we believe we can do better. Our prescription for success? Streamlined workflow, smarter EHRs, and fewer clicks. There is no question that physicians and patients will benefit from effective implementation of the new tools at our disposal, but we need EHR vendors to step up and help carry the load.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter @doctornotte. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health.

USPSTF draft guidance calls for drug use screening

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

according to a draft recommendation statement now available for public comment.

The statement defines illicit drug use as “use of illegal drugs and the nonmedical use of prescription psychoactive medications (i.e., use for reasons, for duration, in amounts, or with frequency other than prescribed or use by persons other than the prescribed individual).”

The guidelines do not apply to individuals younger than 18 years, for whom the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening, or to adults currently diagnosed or in treatment for a drug use disorder.

In the draft recommendation statement, available online, the USPSTF noted that several screening tools are available for use in primary care practices, including the BSTAD (Brief Screener for Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs) that consists of six questions. The task force noted that they have found “adequate evidence” that these screening tools can detect illicit drug use. In addition, they wrote that no studies offer evidence of benefits versus harms of these screening tools, and evidence of harms associated with screening are limited.

Screening intervals can be simplified by screening young adults whenever they seek medical services and when clinicians suspect illicit drug use, the USPSTF said.

When the draft recommendation is finalized, it will replace the 2008 recommendation, which found insufficient evidence for screening in adults, as well as in adolescents. New evidence since 2008 supports the value of screening for adults aged 18 years and older, including pregnant and postpartum women.

The draft recommendations are based on the results of two systematic evidence reviews that assessed the accuracy and harms of routine illicit drug use screening. The USPSTF’s review included 12 studies on the accuracy of 15 screening tools. Overall, the sensitivity of direct screening tools to identify “unhealthy use of ‘any drug’ (including illegal drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs) in the past month or year” ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, and the specificity ranged from 0.87 to 0.97.

Based on the current evidence, the USPSTF assigned drug screening for adults a grade B recommendation, defined as “high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.”

For treatment, the Task Force found evidence to support strategies including pharmacotherapy with naltrexone, buprenorphine, and methadone, as well as for psychosocial interventions.

The USPSTF acknowledged that many factors may affect a clinicians’ decision of whether to implement the drug screening recommendation. “In many communities, affordable, accessible, and timely services for diagnostic assessment and treatment for patients with positive screening results are in limited supply or unaffordable. Providers should be aware of any state requirements for mandatory screening or reporting of screening results to medicolegal authorities and understand the positive and negative implications of reporting,” they wrote.

The draft recommendations also identified several research gaps including the effectiveness of screening for illicit drug use in adolescents, the optimal screening interval for all patients, the accuracy of screening tools for detecting opioids, the accuracy of screening within the same population, the benefits of naloxone as rescue therapy, and nonmedical use of other prescription drugs, as well as ways to improve access to care for those diagnosed with drug use disorders.

The draft recommendation is available for public comment until Sept. 9, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST.

The USPSTF is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE USPSTF

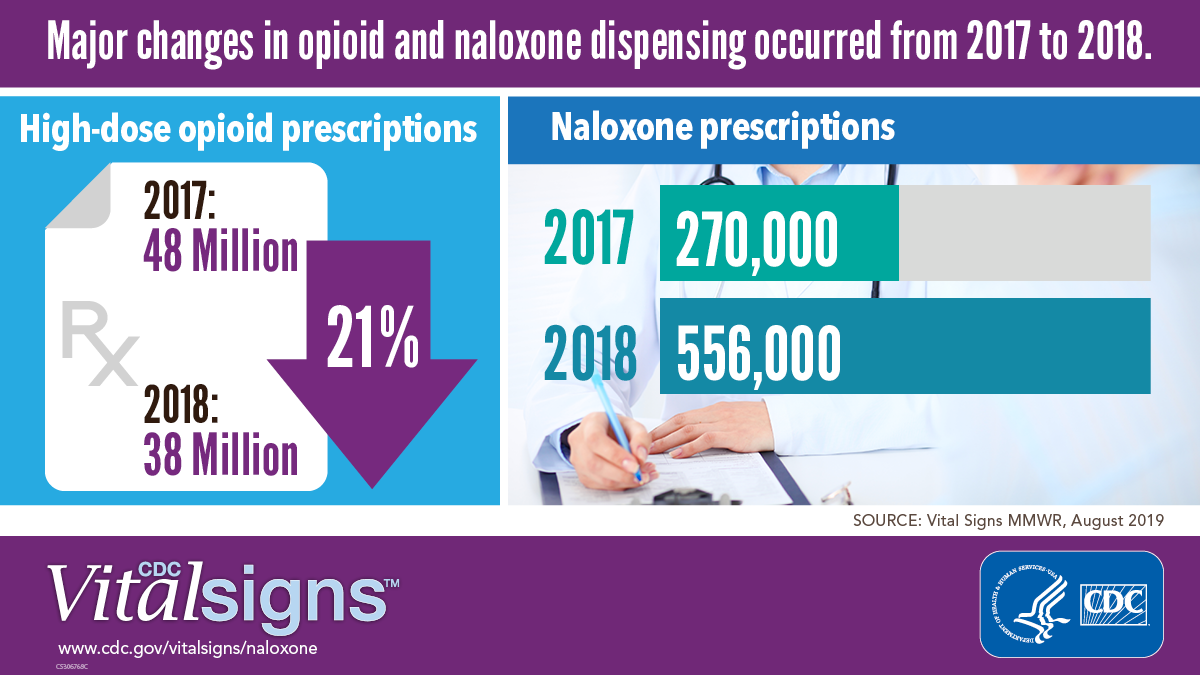

CDC finds that too little naloxone is dispensed

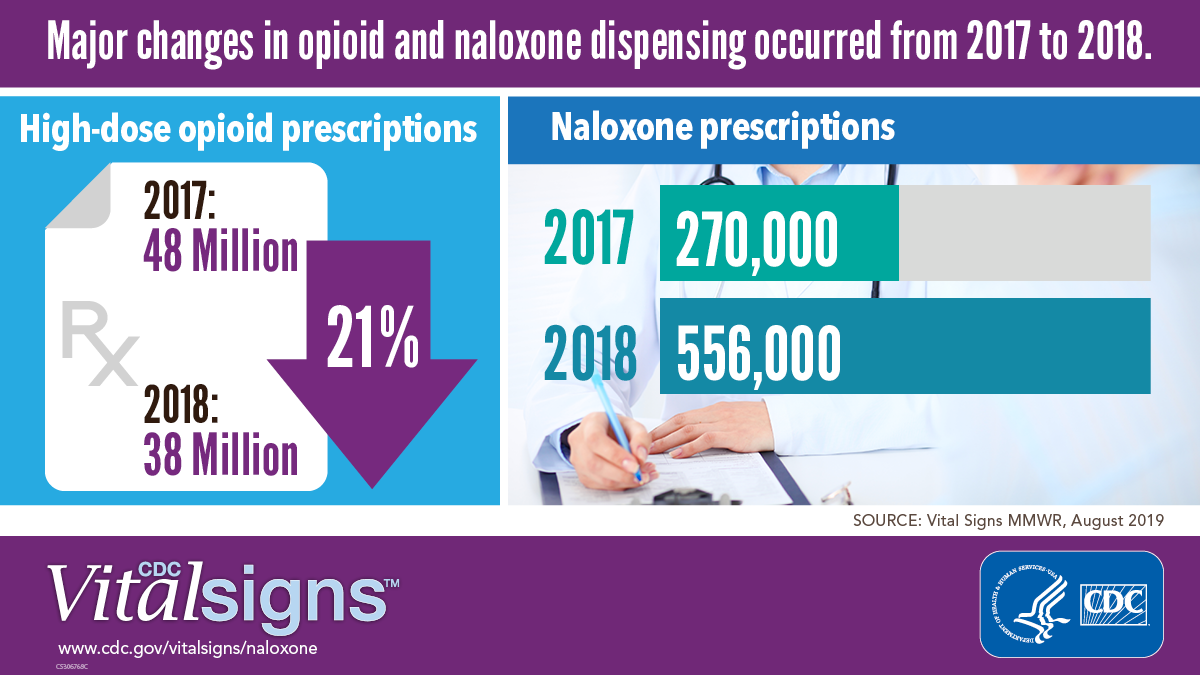

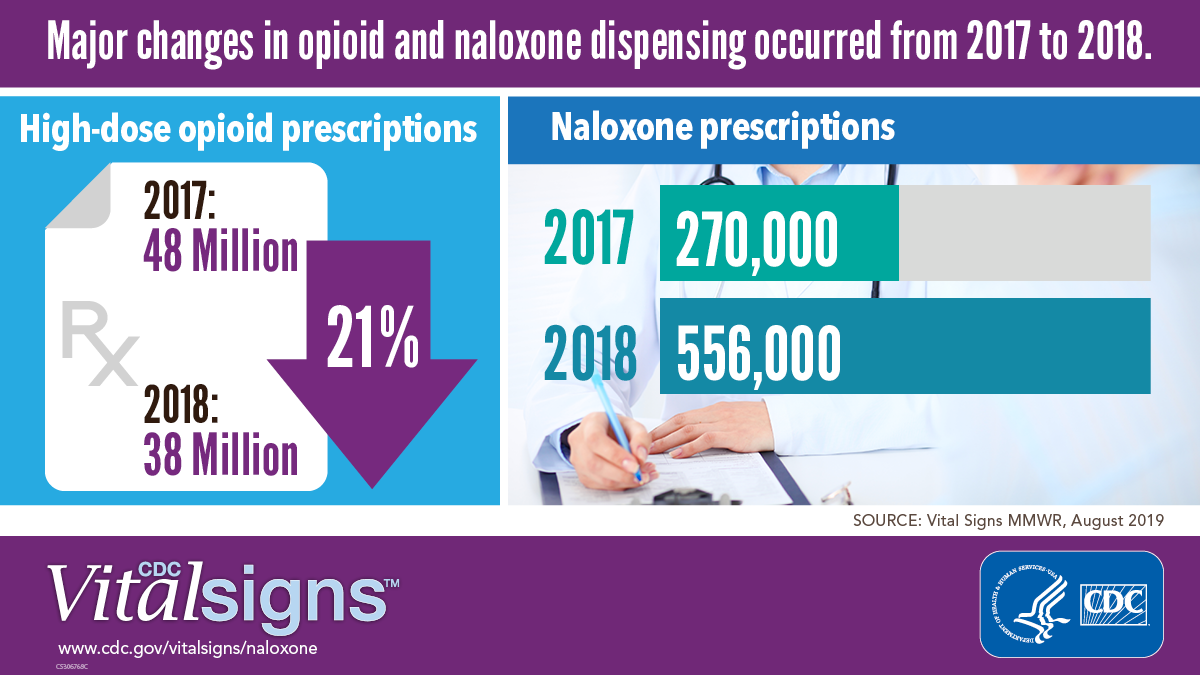

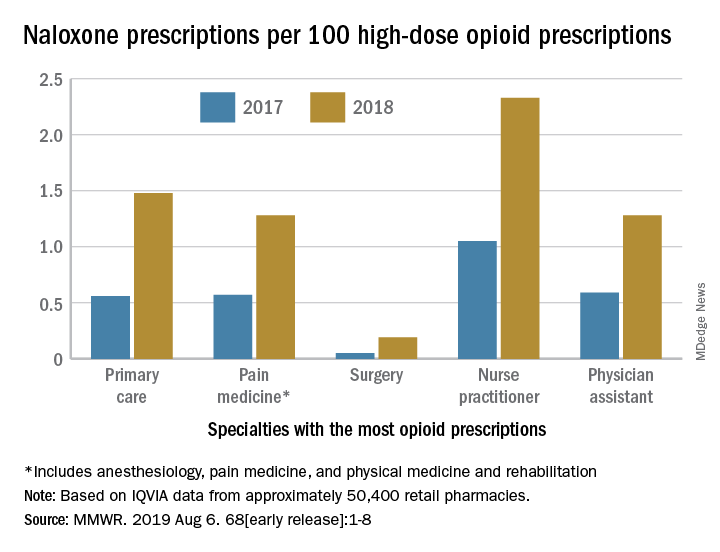

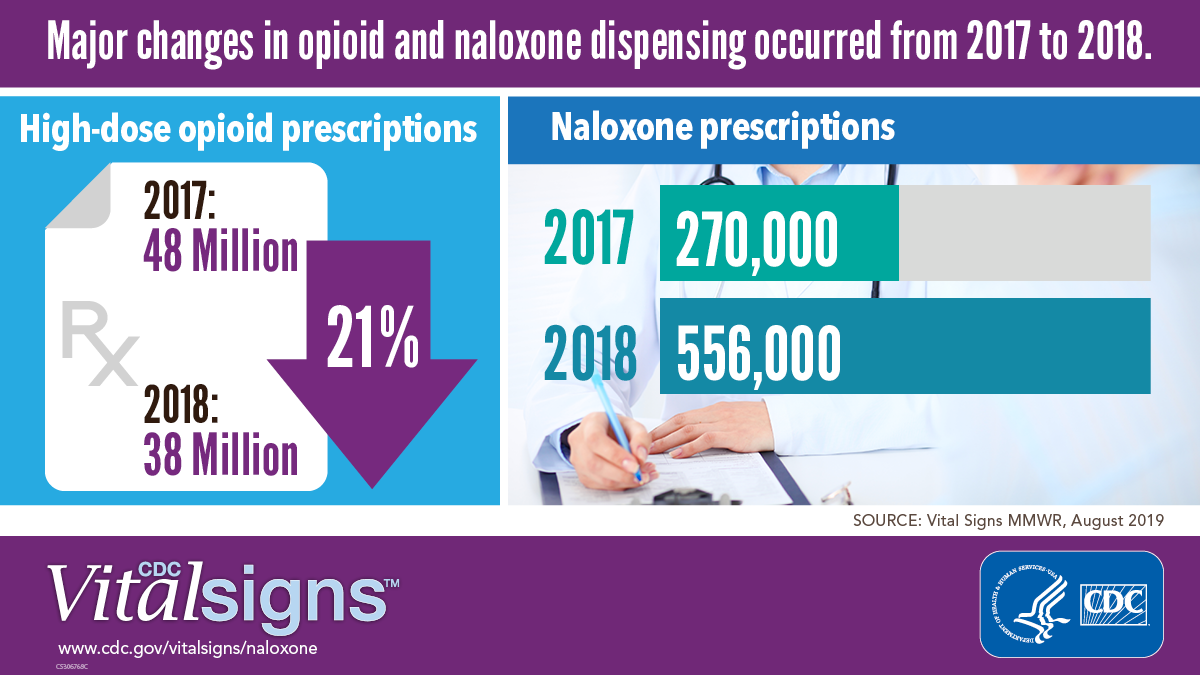

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

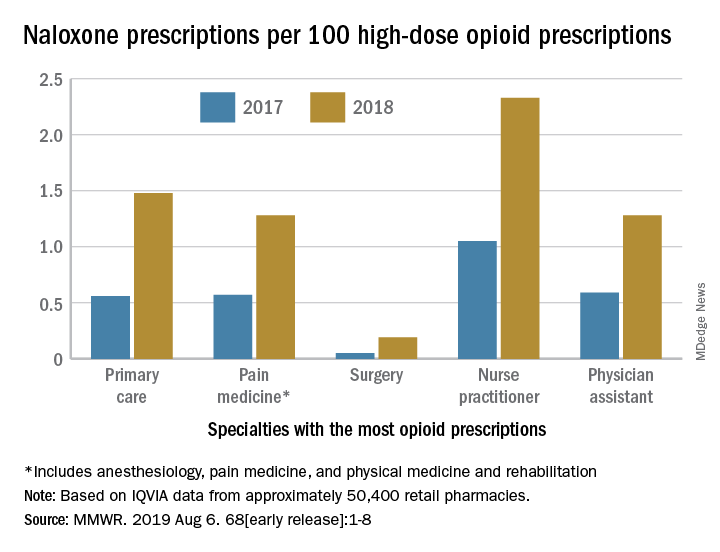

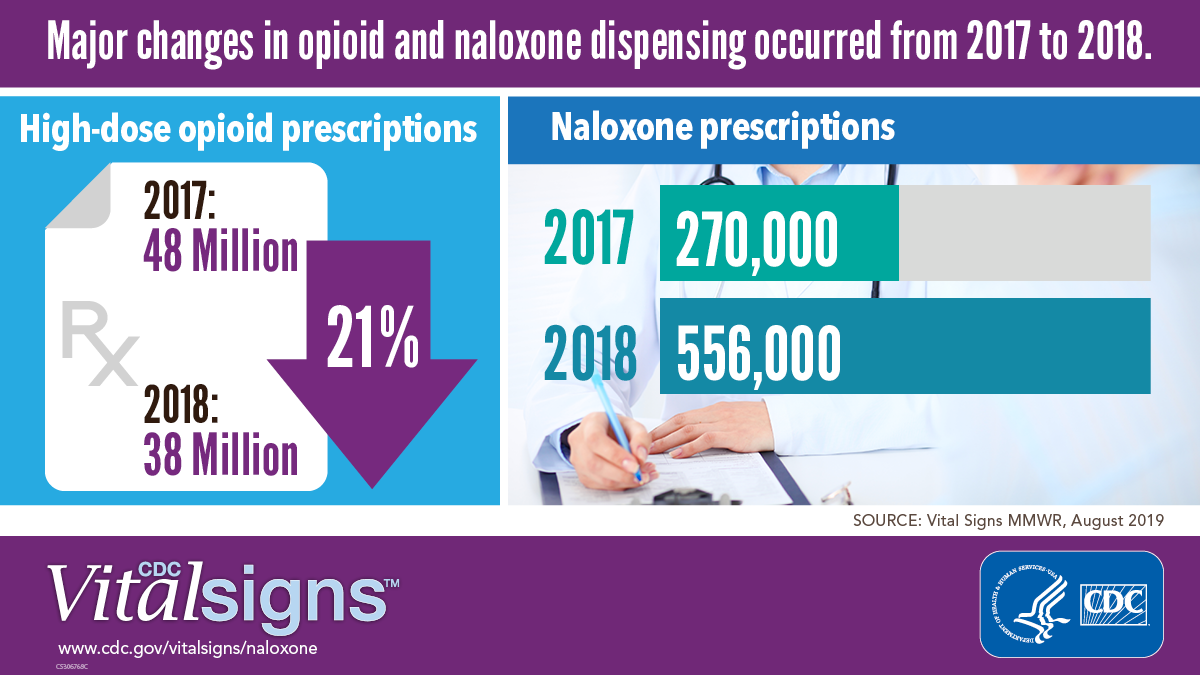

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

Although the CDC recommends that clinicians consider prescribing naloxone, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to patients who receive high-dose opioid prescriptions, one naloxone prescription was dispensed in 2018 for every 69 such patients, according to a Vital Signs investigation published Aug. 6 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Approximately 9 million more naloxone prescriptions could have been dispensed in 2018 if every patient with a high-dose opioid prescription were offered the drug, according to the agency. In addition, the rate at which naloxone is dispensed varies significantly according to region.

“Thousands of Americans are alive today thanks to the use of naloxone,” said Alex M. Azar, secretary of Health and Human Services, in a press release. “Giving people a chance to survive an opioid overdose and safely enter recovery is one of the five key pillars of our HHS strategy for ending the overdose epidemic. With help from Congress, the private sector, state, and local governments and communities, targeted access to naloxone has expanded dramatically over the last several years, but today’s CDC report is a reminder that there is much more all of us need to do to save lives.”

Investigators examined retail pharmacy data

In 2017, 47,600 (67.8%) drug overdose deaths in the United States involved opioids. For decades, emergency medical service providers have administered naloxone to patients with suspected drug overdose. A major focus of public health initiatives intended to address the opioid overdose crisis has been to increase access to naloxone through clinician prescribing and pharmacy dispensing. The CDC recommends considering prescribing naloxone to patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, those receiving opioid dosages of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater (that is, high-dose prescriptions), and those who are using benzodiazepines concurrently.

Investigators at the CDC examined retail pharmacy data from IQVIA, a company that maintains information on prescriptions from approximately 50,400 retail pharmacies. They extracted data from 2012 through 2018 to analyze naloxone dispensing by region, urban versus rural status, prescriber specialty, and recipient characteristics (for example, age group, sex, out-of-pocket costs, and method of payment).

Dispensations doubled from 2017 to 2018

Naloxone dispensing from retail pharmacies increased from 0.4 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2012 to 170.2 prescriptions per 100,000 in 2018. From 2017 to 2018 alone, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 106%.

Despite consistency among state laws, naloxone dispensation varied by region. The average rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 0.2 in the lowest quartile to 2.9 in the highest quartile. In 2018, the rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions ranged from 1.5 in metropolitan counties and 1.6 in the Northeast to 1.2 in rural counties and 1.3 in the Midwest. Rural counties were nearly three times more likely to be low-dispensing counties, compared with metropolitan counties.

The rate of naloxone prescriptions per 100 high-dose opioid prescriptions also varied by provider specialty. This rate was lowest among surgeons (0.2) and highest among psychiatrists (12.9).

Most naloxone prescriptions entailed out-of-pocket costs. About 71% of prescriptions paid for by Medicare entailed out-of-pocket costs, compared with 43.8% of prescriptions paid for by Medicaid, and 41.5% of prescriptions paid for by commercial insurance.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

More can be done

“It is clear from the data that there is still much needed education around the important role naloxone plays in reducing overdose deaths,” said Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, in a press release. “The time is now to ensure all individuals who are prescribed high-dose opioids also receive naloxone as a potential life-saving intervention. As we aggressively confront what is the public health crisis of our time, CDC will continue to stress with health care providers the benefit of making this overdose-reversing medicine available to patients.”

“While we’ve seen these important increases [in naloxone prescriptions], we are not as far along as we’d like to be,” said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, during a press conference. “Cost is one of the issues, but I think awareness is another.” These data should prompt pharmacies to make sure that they stock naloxone and remind clinicians to consider naloxone when they prescribe opioids, she added. Patients and their family members should be aware of naloxone and ask their health care providers about it. “We’d really like to see the increase [in naloxone prescriptions] move much more rapidly,” she concluded.

The investigators disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guy GP et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Aug 6.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Pharmacist stigma a barrier to rural buprenorphine access

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Most attention paid to barriers for medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder has focused on prescribers and patients, but pharmacists are “a neglected link in the chain,” according to Hannah Cooper, ScD, an assistant professor of behavioral sciences and health education at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Pharmacy-based dispensing of buprenorphine is one of the medication’s major advances over methadone,” Dr. Cooper told attendees at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. Yet, early interviews she and her colleagues conducted with rural Kentucky pharmacist colleagues in the CARE2HOPE study “revealed that pharmacy-level barriers might also curtail access to buprenorphine.”

Little research has examined those barriers, but Dr. Cooper noted. Further, anecdotal evidence has suggested that wholesaler concerns about Drug Enforcement Administration restrictions on dispensing buprenorphine has caused shortages at pharmacies.

Dr. Cooper and colleagues, therefore, designed a qualitative study aimed at learning about pharmacists’ attitudes and dispensing practices related to buprenorphine. They also looked at whether DEA limits actually exist on dispensing the drug. They interviewed 14 pharmacists operating 15 pharmacies across all 12 counties in two rural Kentucky health districts. Eleven of the pharmacists worked in independent pharmacies; the others worked at chains. Six pharmacies dispensed more than 100 buprenorphine prescriptions a month, five dispensed only several dozen a month, and four refused to dispense it at all.

Perceptions of federal restrictions

“Variations in buprenorphine dispensing did not solely reflect underlying variations in local need or prescribing practices,” Dr. Cooper said. At 12 of the 15 pharmacies, limits on buprenorphine resulted from a perceived DEA “cap” on dispensing the drug or “because of distrust in buprenorphine itself, its prescribers and its patients.”

The perceived cap from the DEA was shrouded in uncertainty: 10 of the pharmacists said the DEA capped the percentage of controlled substances pharmacists could dispense that were opioids, yet the pharmacists did not know what that percentage was.

Five of those interviewed said the cap often significantly cut short how many buprenorphine prescriptions they would dispense. Since they did not know how much the cap was, they internally set arbitrary limits, such as dispensing two prescriptions per day, to avoid risk of the DEA investigating their pharmacy.

Yet, those limits could not meet patient demand, so several pharmacists rationed buprenorphine only to local residents or long-term customers, causing additional problems. That practice strained relationships with prescribers, who then had to call multiple pharmacies to find one that would dispense the drug to new patients. It also put pharmacy staff at risk when a rejection angered a customer and “undermined local recovery efforts,” Dr. Cooper said.

Five other pharmacists, however, did not ration their buprenorphine and did not worry about exceeding the DEA cap.

No numerical cap appears to exist, but DEA regulations and the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act do require internal opioid surveillance systems at wholesalers that flag suspicious orders of controlled substances, including buprenorphine. And they enforce it: An $80 million settlement in 2013 resulted from the DEA’s charge that Walgreens distribution centers did not report suspicious drug orders.

Stigma among some pharmacists

Six of the pharmacists had low trust in buprenorphine and in those who prescribed it and used it, Dr. Cooper reported. Three would not dispense the drug at all, and two would not take new buprenorphine patients.

One such pharmacist told researchers: “It is supposed to be the drug to help them [recover.] They want Suboxone worse than they do the hydrocodone. … It’s not what it’s designed to be.”

Those pharmacists also reported believing that malpractice was common among prescribers, who, for example, did not provide required counseling to patients or did not quickly wean them off buprenorphine. The pharmacists perceived the physicians prescribing buprenorphine as doing so only to make more money, just as they had done by prescribing opioids in the first place.

Those pharmacists also believed the patients themselves sold buprenorphine to make money and that opioid use disorder was a choice. They told researchers that dispensing buprenorphine would bring more drug users to their stores and subsequently hurt business.

Yet, those beliefs were not universal among the pharmacists. Eight believed buprenorphine was an appropriate opioid use disorder treatment and had positive attitudes toward patients. Unlike those who viewed the disorder as a choice, those pharmacists saw it as a disease and viewed the patients admirably for their commitment to recovery.

Though a small, qualitative study, those findings suggest a need to more closely examine how pharmacies affect access to medication to treat opioid use disorder, Dr. Cooper said.

“In an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic, policies and stigma curtail access to buprenorphine,” she told attendees. “DEA regulations, the SUPPORT Act, and related lawsuits have led wholesalers to develop proprietary caps that force some pharmacists to ration the number of buprenorphine prescriptions they filled.” Some pharmacists will not dispense the drug at all, while others “limited dispensing to known or local patients and prescribers, a practice that pharmacists recognized hurt patients who had to travel far to reach prescribers.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health through CARE2HOPE, Rural Health Project, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research. The authors reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Medication overuse prevalent among U.S. migraine patients

PHILADELPHIA – according to findings from an analysis of 16,789 people with migraine.

About 18% of the people identified with migraine in the study cohort reported a drug consumption pattern that met the prespecified definition of “medication overuse,” Todd J. Schwedt, MD, and his associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Supplying each migraine patient with a “comprehensive treatment plan” along with “improved acute treatment options ... may help reduce the prevalence and associated burden of medication overuse,” said Dr. Schwedt, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. The analysis also showed that medication overuse (MO) significantly linked with several markers of worse clinical status.

If patients have “an effective preventive treatment that reduces headaches and migraine attacks then they will, in general, use less acute medications. Many people with migraine never even get diagnosed, and patients who qualify for preventive treatment never get it,” Dr. Schwedt noted in an interview. He described a comprehensive treatment plan as a management strategy that includes lifestyle modifications, a migraine-prevention agent, and the availability of an effective acute treatment for a patient to use when a migraine strikes along with clear instructions on how to appropriately self-administer the medication. Only a small fraction of U.S. migraine patients currently receive this complete package of care, he said.

The analysis he ran used data collected in the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes) study, which used an Internet-based survey to collect data from a representative 58,000-person sample of U.S. residents, which included 16,789 who met the applied migraine definition, with 91% having fewer than 15 headaches/month and the remaining 9% with a monthly headache average of 15 or more (Cephalagia. 2015 Jun;35[7]:563-78).

The researchers defined overuse of a single medication as use 15 times or more a month of an NSAID, aspirin, or acetaminophen, or use at least 10 times a month of a triptan, ergotamine, or opioid. They also had a prespecified definition of multidrug overuse that applied similar monthly thresholds. The patients averaged about 41 years old, three-quarters were women, and 85% were white. Patients identified with MO had a substantially higher rate of headaches per month: an average of nearly 12, compared with an average of about 4 per month among those without overuse. Almost two-thirds of the patients with MO reported having been formally diagnosed as having migraine headaches, compared with 41% of those without overuse.

Among the 13,749 patients (82%) on some headache medication, 67% were on a nonopioid analgesic, including 61% on an NSAID. MO among all people on nonopioid analgesics was 16%, and 12% among those who used NSAIDS. The most overused drug in this subgroup were combination analgesics, overused by 18% of those taking these drugs.

The drug class with the biggest MO rate was opioids, used by 12% of those on any medication and overused by 22% of those taking an opioid. Triptans were taken by 11%, with an MO rate of 11% among these users. Ergotamine was used by less than 1% of all patients, and those taking this drug tallied a 19% MO rate.

“Opioids were the class most often overused, more evidence that opioids should rarely if ever be used to treat migraine,” Dr. Schwedt said.

The analysis also showed that patients who had MO has multiple signs of worse clinical status. Patients with MO had a significantly higher rate of diagnosed depression, 54%, compared with 28% in those without MO; anxiety, 49% compared with 26%; migraine-associated disability, 73% compared with 32%; migraine-associated functional impairment (Migraine Interictal Burden Scale), 65% compared with 32%; and emergency department or urgent care use, 13% compared with 3%. All these between-group differences were statistically significant.

CaMEO was funded by Allergan. Dr. Schwedt has been a consultant to Allergan, and also to Alder, Amgen, Cipla, Dr. Reddy’s, Ipsen, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. He has stock ownership in Aural Analytics, Nocira, and Second Opinion, and he has received research funding from Amgen.

SOURCE: Schwedt TJ et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:83-4, Abstract P92.

PHILADELPHIA – according to findings from an analysis of 16,789 people with migraine.

About 18% of the people identified with migraine in the study cohort reported a drug consumption pattern that met the prespecified definition of “medication overuse,” Todd J. Schwedt, MD, and his associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Supplying each migraine patient with a “comprehensive treatment plan” along with “improved acute treatment options ... may help reduce the prevalence and associated burden of medication overuse,” said Dr. Schwedt, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. The analysis also showed that medication overuse (MO) significantly linked with several markers of worse clinical status.

If patients have “an effective preventive treatment that reduces headaches and migraine attacks then they will, in general, use less acute medications. Many people with migraine never even get diagnosed, and patients who qualify for preventive treatment never get it,” Dr. Schwedt noted in an interview. He described a comprehensive treatment plan as a management strategy that includes lifestyle modifications, a migraine-prevention agent, and the availability of an effective acute treatment for a patient to use when a migraine strikes along with clear instructions on how to appropriately self-administer the medication. Only a small fraction of U.S. migraine patients currently receive this complete package of care, he said.

The analysis he ran used data collected in the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes) study, which used an Internet-based survey to collect data from a representative 58,000-person sample of U.S. residents, which included 16,789 who met the applied migraine definition, with 91% having fewer than 15 headaches/month and the remaining 9% with a monthly headache average of 15 or more (Cephalagia. 2015 Jun;35[7]:563-78).

The researchers defined overuse of a single medication as use 15 times or more a month of an NSAID, aspirin, or acetaminophen, or use at least 10 times a month of a triptan, ergotamine, or opioid. They also had a prespecified definition of multidrug overuse that applied similar monthly thresholds. The patients averaged about 41 years old, three-quarters were women, and 85% were white. Patients identified with MO had a substantially higher rate of headaches per month: an average of nearly 12, compared with an average of about 4 per month among those without overuse. Almost two-thirds of the patients with MO reported having been formally diagnosed as having migraine headaches, compared with 41% of those without overuse.

Among the 13,749 patients (82%) on some headache medication, 67% were on a nonopioid analgesic, including 61% on an NSAID. MO among all people on nonopioid analgesics was 16%, and 12% among those who used NSAIDS. The most overused drug in this subgroup were combination analgesics, overused by 18% of those taking these drugs.

The drug class with the biggest MO rate was opioids, used by 12% of those on any medication and overused by 22% of those taking an opioid. Triptans were taken by 11%, with an MO rate of 11% among these users. Ergotamine was used by less than 1% of all patients, and those taking this drug tallied a 19% MO rate.

“Opioids were the class most often overused, more evidence that opioids should rarely if ever be used to treat migraine,” Dr. Schwedt said.

The analysis also showed that patients who had MO has multiple signs of worse clinical status. Patients with MO had a significantly higher rate of diagnosed depression, 54%, compared with 28% in those without MO; anxiety, 49% compared with 26%; migraine-associated disability, 73% compared with 32%; migraine-associated functional impairment (Migraine Interictal Burden Scale), 65% compared with 32%; and emergency department or urgent care use, 13% compared with 3%. All these between-group differences were statistically significant.

CaMEO was funded by Allergan. Dr. Schwedt has been a consultant to Allergan, and also to Alder, Amgen, Cipla, Dr. Reddy’s, Ipsen, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. He has stock ownership in Aural Analytics, Nocira, and Second Opinion, and he has received research funding from Amgen.

SOURCE: Schwedt TJ et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:83-4, Abstract P92.

PHILADELPHIA – according to findings from an analysis of 16,789 people with migraine.

About 18% of the people identified with migraine in the study cohort reported a drug consumption pattern that met the prespecified definition of “medication overuse,” Todd J. Schwedt, MD, and his associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Supplying each migraine patient with a “comprehensive treatment plan” along with “improved acute treatment options ... may help reduce the prevalence and associated burden of medication overuse,” said Dr. Schwedt, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. The analysis also showed that medication overuse (MO) significantly linked with several markers of worse clinical status.

If patients have “an effective preventive treatment that reduces headaches and migraine attacks then they will, in general, use less acute medications. Many people with migraine never even get diagnosed, and patients who qualify for preventive treatment never get it,” Dr. Schwedt noted in an interview. He described a comprehensive treatment plan as a management strategy that includes lifestyle modifications, a migraine-prevention agent, and the availability of an effective acute treatment for a patient to use when a migraine strikes along with clear instructions on how to appropriately self-administer the medication. Only a small fraction of U.S. migraine patients currently receive this complete package of care, he said.

The analysis he ran used data collected in the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes) study, which used an Internet-based survey to collect data from a representative 58,000-person sample of U.S. residents, which included 16,789 who met the applied migraine definition, with 91% having fewer than 15 headaches/month and the remaining 9% with a monthly headache average of 15 or more (Cephalagia. 2015 Jun;35[7]:563-78).

The researchers defined overuse of a single medication as use 15 times or more a month of an NSAID, aspirin, or acetaminophen, or use at least 10 times a month of a triptan, ergotamine, or opioid. They also had a prespecified definition of multidrug overuse that applied similar monthly thresholds. The patients averaged about 41 years old, three-quarters were women, and 85% were white. Patients identified with MO had a substantially higher rate of headaches per month: an average of nearly 12, compared with an average of about 4 per month among those without overuse. Almost two-thirds of the patients with MO reported having been formally diagnosed as having migraine headaches, compared with 41% of those without overuse.

Among the 13,749 patients (82%) on some headache medication, 67% were on a nonopioid analgesic, including 61% on an NSAID. MO among all people on nonopioid analgesics was 16%, and 12% among those who used NSAIDS. The most overused drug in this subgroup were combination analgesics, overused by 18% of those taking these drugs.

The drug class with the biggest MO rate was opioids, used by 12% of those on any medication and overused by 22% of those taking an opioid. Triptans were taken by 11%, with an MO rate of 11% among these users. Ergotamine was used by less than 1% of all patients, and those taking this drug tallied a 19% MO rate.

“Opioids were the class most often overused, more evidence that opioids should rarely if ever be used to treat migraine,” Dr. Schwedt said.

The analysis also showed that patients who had MO has multiple signs of worse clinical status. Patients with MO had a significantly higher rate of diagnosed depression, 54%, compared with 28% in those without MO; anxiety, 49% compared with 26%; migraine-associated disability, 73% compared with 32%; migraine-associated functional impairment (Migraine Interictal Burden Scale), 65% compared with 32%; and emergency department or urgent care use, 13% compared with 3%. All these between-group differences were statistically significant.

CaMEO was funded by Allergan. Dr. Schwedt has been a consultant to Allergan, and also to Alder, Amgen, Cipla, Dr. Reddy’s, Ipsen, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. He has stock ownership in Aural Analytics, Nocira, and Second Opinion, and he has received research funding from Amgen.

SOURCE: Schwedt TJ et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:83-4, Abstract P92.

REPORTING FROM AHS 2019

Gynecologic surgeries linked with persistent opioid use

– showing that persistent opioid use can follow such surgeries.

For a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Jason D. Wright, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues looked at insurance claims data from 729,625 opioid-naive women, median age 44 years, who had undergone a myomectomy; a minimally invasive, vaginal, or abdominal hysterectomy; an open or laparoscopic oophorectomy; endometrial ablation; tubal ligation; or dilation and curettage. The vast majority of subjects, 93%, had commercial health insurance, with the rest enrolled in Medicaid. Women undergoing multiple surgical procedures, with serious comorbidities, or who underwent another surgery within 6 months of the initial one, were excluded from the analysis.