User login

Parent education improves quick disposal of children’s unused prescription opioids

SAN ANTONIO – Interventions aimed at educating parents about proper disposal methods for leftover prescription opioids and on explaining the risks of retaining opioids can increase the likelihood that parents will dispose of opioids when their children no longer need them, according to new research.

“Cost-effective disposal methods can nudge parents to dispose of their child’s leftover opioids promptly after use, but risk messaging is needed to best affect both early disposal and planned retention,” concluded Terri Voepel-Lewis, PhD, RN, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Such strategies can effectively reduce the presence of risky leftover medications in the home and decrease the risks posed to children and adolescents,” they wrote in a research poster at the annual meeting of College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers recruited 517 parents of children prescribed a short course of opioids, excluding children with chronic pain or the inability to report their pain.

The 255 parents randomly assigned to the nudge group received visual instructions on how to properly dispose of drugs while the 262 parents in the control group did not receive information on a disposal method. The groups were otherwise similar in terms of parent education, race/ethnicity, the child’s age and past opioid use, the parents’ past opioid use or misuse, whether opioids were kept in the home and whether the child’s procedure had been orthopedic/sports medicine–related.

Parents also were randomly assigned to routine care or to a Scenario-Tailored Opioid Messaging Program (STOMP). The STOMP group received tailored opioid risk information.

After a baseline survey on the child’s past pain, opioid use, misuse of opioids and risk perceptions, parents completed follow-up surveys at 7 and 14 days on opioid use, child pain, and behaviors related to retaining or disposing of opioids.

Just over a third of parents in the nudge group (34.7%) disposed of leftover opioids immediately after use, compared with 24% in the control group (odds ratio, 1.68; P = .01). Parents with the highest rate of disposal were those in the nudge group who participated in STOMP; they were more than twice as likely to dispose of opioids immediately after they were no longer needed (OR, 2.55; compared with control/non-STOMP).

A higher likelihood of disposal for parents in the nudge group alone, however, barely missed significance (OR, 1.77; P = .06) before adjustment. Parents’ intention to dispose of opioids was significantly different only among those who received STOMP education.

After the researchers controlled for child and parent factors, actual early disposal was significantly more likely in both the nudge and STOMP groups.

“Parental past opioid behaviors (kept an opioid in the home and past misuse) as well as orthopedic/sports medicine procedure were strongly associated with parents’ intention to retain [opioids],” the authors reported.

The study results revealed a divergence in parents’ intentions versus their behavior for one of the intervention groups.

“The nudge intervention improved parents’ prompt disposal of leftover prescription opioids but had no effect on planned retention rates,” the researchers reported. “In contrast, STOMP education had significant effects on early disposal behavior and planned retention. ”

Additional findings regarding parents’ past behaviors suggested that those who have kept leftover opioids or previously misused them may see the risks of doing so as low, the authors noted.

“Importantly, parents’ past prescription opioid retention behavior doubled the risk for planned retention, and their past opioid misuse more than tripled the risk,” the researchers wrote. “Assessing parents’ past behaviors and enhancing their perceptions of the real risks posed to children are important targets for risk reduction.”

The National Institute on Drug Addiction funded the research. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Interventions aimed at educating parents about proper disposal methods for leftover prescription opioids and on explaining the risks of retaining opioids can increase the likelihood that parents will dispose of opioids when their children no longer need them, according to new research.

“Cost-effective disposal methods can nudge parents to dispose of their child’s leftover opioids promptly after use, but risk messaging is needed to best affect both early disposal and planned retention,” concluded Terri Voepel-Lewis, PhD, RN, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Such strategies can effectively reduce the presence of risky leftover medications in the home and decrease the risks posed to children and adolescents,” they wrote in a research poster at the annual meeting of College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers recruited 517 parents of children prescribed a short course of opioids, excluding children with chronic pain or the inability to report their pain.

The 255 parents randomly assigned to the nudge group received visual instructions on how to properly dispose of drugs while the 262 parents in the control group did not receive information on a disposal method. The groups were otherwise similar in terms of parent education, race/ethnicity, the child’s age and past opioid use, the parents’ past opioid use or misuse, whether opioids were kept in the home and whether the child’s procedure had been orthopedic/sports medicine–related.

Parents also were randomly assigned to routine care or to a Scenario-Tailored Opioid Messaging Program (STOMP). The STOMP group received tailored opioid risk information.

After a baseline survey on the child’s past pain, opioid use, misuse of opioids and risk perceptions, parents completed follow-up surveys at 7 and 14 days on opioid use, child pain, and behaviors related to retaining or disposing of opioids.

Just over a third of parents in the nudge group (34.7%) disposed of leftover opioids immediately after use, compared with 24% in the control group (odds ratio, 1.68; P = .01). Parents with the highest rate of disposal were those in the nudge group who participated in STOMP; they were more than twice as likely to dispose of opioids immediately after they were no longer needed (OR, 2.55; compared with control/non-STOMP).

A higher likelihood of disposal for parents in the nudge group alone, however, barely missed significance (OR, 1.77; P = .06) before adjustment. Parents’ intention to dispose of opioids was significantly different only among those who received STOMP education.

After the researchers controlled for child and parent factors, actual early disposal was significantly more likely in both the nudge and STOMP groups.

“Parental past opioid behaviors (kept an opioid in the home and past misuse) as well as orthopedic/sports medicine procedure were strongly associated with parents’ intention to retain [opioids],” the authors reported.

The study results revealed a divergence in parents’ intentions versus their behavior for one of the intervention groups.

“The nudge intervention improved parents’ prompt disposal of leftover prescription opioids but had no effect on planned retention rates,” the researchers reported. “In contrast, STOMP education had significant effects on early disposal behavior and planned retention. ”

Additional findings regarding parents’ past behaviors suggested that those who have kept leftover opioids or previously misused them may see the risks of doing so as low, the authors noted.

“Importantly, parents’ past prescription opioid retention behavior doubled the risk for planned retention, and their past opioid misuse more than tripled the risk,” the researchers wrote. “Assessing parents’ past behaviors and enhancing their perceptions of the real risks posed to children are important targets for risk reduction.”

The National Institute on Drug Addiction funded the research. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Interventions aimed at educating parents about proper disposal methods for leftover prescription opioids and on explaining the risks of retaining opioids can increase the likelihood that parents will dispose of opioids when their children no longer need them, according to new research.

“Cost-effective disposal methods can nudge parents to dispose of their child’s leftover opioids promptly after use, but risk messaging is needed to best affect both early disposal and planned retention,” concluded Terri Voepel-Lewis, PhD, RN, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Such strategies can effectively reduce the presence of risky leftover medications in the home and decrease the risks posed to children and adolescents,” they wrote in a research poster at the annual meeting of College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers recruited 517 parents of children prescribed a short course of opioids, excluding children with chronic pain or the inability to report their pain.

The 255 parents randomly assigned to the nudge group received visual instructions on how to properly dispose of drugs while the 262 parents in the control group did not receive information on a disposal method. The groups were otherwise similar in terms of parent education, race/ethnicity, the child’s age and past opioid use, the parents’ past opioid use or misuse, whether opioids were kept in the home and whether the child’s procedure had been orthopedic/sports medicine–related.

Parents also were randomly assigned to routine care or to a Scenario-Tailored Opioid Messaging Program (STOMP). The STOMP group received tailored opioid risk information.

After a baseline survey on the child’s past pain, opioid use, misuse of opioids and risk perceptions, parents completed follow-up surveys at 7 and 14 days on opioid use, child pain, and behaviors related to retaining or disposing of opioids.

Just over a third of parents in the nudge group (34.7%) disposed of leftover opioids immediately after use, compared with 24% in the control group (odds ratio, 1.68; P = .01). Parents with the highest rate of disposal were those in the nudge group who participated in STOMP; they were more than twice as likely to dispose of opioids immediately after they were no longer needed (OR, 2.55; compared with control/non-STOMP).

A higher likelihood of disposal for parents in the nudge group alone, however, barely missed significance (OR, 1.77; P = .06) before adjustment. Parents’ intention to dispose of opioids was significantly different only among those who received STOMP education.

After the researchers controlled for child and parent factors, actual early disposal was significantly more likely in both the nudge and STOMP groups.

“Parental past opioid behaviors (kept an opioid in the home and past misuse) as well as orthopedic/sports medicine procedure were strongly associated with parents’ intention to retain [opioids],” the authors reported.

The study results revealed a divergence in parents’ intentions versus their behavior for one of the intervention groups.

“The nudge intervention improved parents’ prompt disposal of leftover prescription opioids but had no effect on planned retention rates,” the researchers reported. “In contrast, STOMP education had significant effects on early disposal behavior and planned retention. ”

Additional findings regarding parents’ past behaviors suggested that those who have kept leftover opioids or previously misused them may see the risks of doing so as low, the authors noted.

“Importantly, parents’ past prescription opioid retention behavior doubled the risk for planned retention, and their past opioid misuse more than tripled the risk,” the researchers wrote. “Assessing parents’ past behaviors and enhancing their perceptions of the real risks posed to children are important targets for risk reduction.”

The National Institute on Drug Addiction funded the research. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Medical cannabis laws appear no longer tied to drop in opioid overdose mortality

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

FROM PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Nicotine replacement therapy beats varenicline for smokers with OUD

SAN ANTONIO – People who smoke and have opioid use disorder have a lower likelihood of drug use several months after initiating smoking cessation treatment if they are treated with nicotine replacement therapy rather than varenicline, new research suggests.

“Differences were not due to the pretreatment differences in drug use, which were covaried,” wrote Damaris J. Rohsenow, PhD, and colleagues at Brown University’s Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Providence, R.I. “Results suggest it may be preferable to offer smokers with opioid use disorder [nicotine replacement therapy] rather than varenicline, given their lower adherence and more illicit drug use days during follow-up when given varenicline compared to [nicotine replacement therapy].”

They shared their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

About 80%-90% of patients with OUD smoke, and those patients have a particularly difficult time with smoking cessation partly because of nonadherence to cessation medications, the authors noted. Smoking increases the risk of relapse from any substance use disorder, and pain – frequently comorbid with smoking – contributes to opioid use, they added.

Though smoking treatment has been shown not to increase drug or alcohol use, varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy have different effects on a4b2 nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors (nAChRs). The authors noted that nicotine offers greater pain inhibition via full agonist effects across multiple nAChRs, whereas varenicline has only a partial agonist effect on a single nAChR.

“Smokers may receive more rewarding dopamine effects from the full nicotine agonist,” they wrote. The researchers therefore aimed to compare responses to nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline among smokers with and without OUD.

Ninety patients without OUD and 47 patients with it were randomly assigned to receive transdermal nicotine replacement therapy with placebo capsules or varenicline capsules with a placebo patch for 12 weeks with 3- and 6-month follow-ups. At baseline, those with OUD were significantly more likely to be white and slightly younger and have twice as many drug use days than those without the disorder.

Differences also existed between those with and without OUD for comorbid alcohol use disorder (55% vs. 81%), marijuana use disorder (32% vs. 19%) and cocaine use disorder (70% vs. 55%).

Those without OUD had slightly greater medication adherence, but with only borderline significance just among those taking varenicline. Loss to follow-up, meanwhile, was significantly greater for those with OUD in both treatment groups.

Those patients had 16.5 drug use days at 4-6 months’ follow-up, compared with 0.13 days among those with OUD using nicotine replacement therapy (P less than .026). Among those without OUD, nicotine replacement therapy patients had 5 drug use days, and varenicline patients had 2.5 drug use days.

“Given interactions between nicotine and the opioid system and given that [nicotine replacement therapy] binds to more types of nAChRs than varenicline does, it is possible that [nicotine replacement therapy] dampens desire to use opiates compared to varenicline by stimulating more nAChRs,” the authors wrote. “Increasing nicotine dose may be better for smokers with opioid use disorder,” they added, though they noted the small size of the study and the need for replication with larger populations.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – People who smoke and have opioid use disorder have a lower likelihood of drug use several months after initiating smoking cessation treatment if they are treated with nicotine replacement therapy rather than varenicline, new research suggests.

“Differences were not due to the pretreatment differences in drug use, which were covaried,” wrote Damaris J. Rohsenow, PhD, and colleagues at Brown University’s Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Providence, R.I. “Results suggest it may be preferable to offer smokers with opioid use disorder [nicotine replacement therapy] rather than varenicline, given their lower adherence and more illicit drug use days during follow-up when given varenicline compared to [nicotine replacement therapy].”

They shared their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

About 80%-90% of patients with OUD smoke, and those patients have a particularly difficult time with smoking cessation partly because of nonadherence to cessation medications, the authors noted. Smoking increases the risk of relapse from any substance use disorder, and pain – frequently comorbid with smoking – contributes to opioid use, they added.

Though smoking treatment has been shown not to increase drug or alcohol use, varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy have different effects on a4b2 nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors (nAChRs). The authors noted that nicotine offers greater pain inhibition via full agonist effects across multiple nAChRs, whereas varenicline has only a partial agonist effect on a single nAChR.

“Smokers may receive more rewarding dopamine effects from the full nicotine agonist,” they wrote. The researchers therefore aimed to compare responses to nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline among smokers with and without OUD.

Ninety patients without OUD and 47 patients with it were randomly assigned to receive transdermal nicotine replacement therapy with placebo capsules or varenicline capsules with a placebo patch for 12 weeks with 3- and 6-month follow-ups. At baseline, those with OUD were significantly more likely to be white and slightly younger and have twice as many drug use days than those without the disorder.

Differences also existed between those with and without OUD for comorbid alcohol use disorder (55% vs. 81%), marijuana use disorder (32% vs. 19%) and cocaine use disorder (70% vs. 55%).

Those without OUD had slightly greater medication adherence, but with only borderline significance just among those taking varenicline. Loss to follow-up, meanwhile, was significantly greater for those with OUD in both treatment groups.

Those patients had 16.5 drug use days at 4-6 months’ follow-up, compared with 0.13 days among those with OUD using nicotine replacement therapy (P less than .026). Among those without OUD, nicotine replacement therapy patients had 5 drug use days, and varenicline patients had 2.5 drug use days.

“Given interactions between nicotine and the opioid system and given that [nicotine replacement therapy] binds to more types of nAChRs than varenicline does, it is possible that [nicotine replacement therapy] dampens desire to use opiates compared to varenicline by stimulating more nAChRs,” the authors wrote. “Increasing nicotine dose may be better for smokers with opioid use disorder,” they added, though they noted the small size of the study and the need for replication with larger populations.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors reported no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – People who smoke and have opioid use disorder have a lower likelihood of drug use several months after initiating smoking cessation treatment if they are treated with nicotine replacement therapy rather than varenicline, new research suggests.

“Differences were not due to the pretreatment differences in drug use, which were covaried,” wrote Damaris J. Rohsenow, PhD, and colleagues at Brown University’s Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Providence, R.I. “Results suggest it may be preferable to offer smokers with opioid use disorder [nicotine replacement therapy] rather than varenicline, given their lower adherence and more illicit drug use days during follow-up when given varenicline compared to [nicotine replacement therapy].”

They shared their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

About 80%-90% of patients with OUD smoke, and those patients have a particularly difficult time with smoking cessation partly because of nonadherence to cessation medications, the authors noted. Smoking increases the risk of relapse from any substance use disorder, and pain – frequently comorbid with smoking – contributes to opioid use, they added.

Though smoking treatment has been shown not to increase drug or alcohol use, varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy have different effects on a4b2 nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors (nAChRs). The authors noted that nicotine offers greater pain inhibition via full agonist effects across multiple nAChRs, whereas varenicline has only a partial agonist effect on a single nAChR.

“Smokers may receive more rewarding dopamine effects from the full nicotine agonist,” they wrote. The researchers therefore aimed to compare responses to nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline among smokers with and without OUD.

Ninety patients without OUD and 47 patients with it were randomly assigned to receive transdermal nicotine replacement therapy with placebo capsules or varenicline capsules with a placebo patch for 12 weeks with 3- and 6-month follow-ups. At baseline, those with OUD were significantly more likely to be white and slightly younger and have twice as many drug use days than those without the disorder.

Differences also existed between those with and without OUD for comorbid alcohol use disorder (55% vs. 81%), marijuana use disorder (32% vs. 19%) and cocaine use disorder (70% vs. 55%).

Those without OUD had slightly greater medication adherence, but with only borderline significance just among those taking varenicline. Loss to follow-up, meanwhile, was significantly greater for those with OUD in both treatment groups.

Those patients had 16.5 drug use days at 4-6 months’ follow-up, compared with 0.13 days among those with OUD using nicotine replacement therapy (P less than .026). Among those without OUD, nicotine replacement therapy patients had 5 drug use days, and varenicline patients had 2.5 drug use days.

“Given interactions between nicotine and the opioid system and given that [nicotine replacement therapy] binds to more types of nAChRs than varenicline does, it is possible that [nicotine replacement therapy] dampens desire to use opiates compared to varenicline by stimulating more nAChRs,” the authors wrote. “Increasing nicotine dose may be better for smokers with opioid use disorder,” they added, though they noted the small size of the study and the need for replication with larger populations.

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Abuse rate of gabapentin, pregabalin far below that of opioids

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

SAN ANTONIO – Prescription opioid abuse has continued declining since 2011, but opioids remain far more commonly abused than other prescription drugs, including gabapentin and pregabalin, new research shows.

“Both gabapentin and pregabalin are abused but at rates that are 6-56 times less frequent than for opioid analgesics,” wrote Kofi Asomaning, DSci, of Pfizer, and associates at Pfizer and Denver Health’s Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center.

“Gabapentin is generally more frequently abused than pregabalin,” they reported in a research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

The researchers analyzed data from the RADARS System Survey of Non-Medical Use of Prescription Drugs Program (NMURx), the RADARS System Treatment Center Programs Combined, and the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS).

All those use self-reported data. The first is a confidential, anonymous web-based survey used to estimate population-level prevalence, and the second surveys patients with opioid use disorder entering treatment. The NPDS tracks all cases reported to poison control centers nationally.

Analysis of the NMURx data revealed similar lifetime abuse prevalence rates for gabapentin and pregabalin at 0.4%, several magnitudes lower than the 5.3% rate identified with opioids.

Gabapentin, however, had higher rates of abuse in the past month in the Treatment Center Programs Combined. For the third to fourth quarter of 2017, 0.12 per 100,000 population reportedly abused gabapentin, compared with 0.01 per 100,000 for pregabalin. The rate for past-month abuse of opioids was 0.79 per 100,000.

A similar pattern for the same quarter emerged from the NPDS data: Rate of gabapentin abuse was 0.06 per 100,000, rate for pregabalin was 0.01 per 100,000, and rate for opioids was 0.40 per 100,000.

Both pregabalin and opioids were predominantly ingested, though a very small amount of each was inhaled and a similarly small amount of opioids was injected. Data on exposure route for gabapentin were not provided, though it was used more frequently than pregabalin.

The research was funded by Pfizer. The RADARS system is owned by Denver Health and Hospital Authority under the Colorado state government. RADARS receives some funding from pharmaceutical industry subscriptions. Dr. Asomaning and Diane L. Martire, MD, MPH, are Pfizer employees who have financial interests with Pfizer.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Chronic opioid use may be common in patients with ankylosing spondylitis

About a quarter of all patients with ankylosing spondylitis, and more than half of those patients who were on Medicaid, received at least a 90-day supply of opioids in a year, based on an analysis of U.S. commercial claims data.

The findings were noted in 2012-2017 data from a cohort of 11,945 patients in the Truven Health MarketScan Research database. Of those patients given the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code 720.0, which is specific for ankylosing spondylitis, 23.5% of patients chronically used opioids. In the broader 720.x commercial claims cohort of 79,190 patients, the proportion who chronically used opioids was 27.3%.

More than 60% of the patients who chronically used opioids had a cumulative drug supply of 270 days or more.

“Patients with ankylosing spondylitis receive opioids with disturbing frequency,” said study author Victor S. Sloan, MD, and research colleagues in the June issue of the Journal of Rheumatology. Ankylosing spondylitis treatment guidelines “specify use of an NSAID as initial pharmacotherapy, with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy in cases of NSAID inefficacy or intolerance. However, for many patients, prescription opioids – while not addressing the underlying inflammation – may offer an inexpensive and rapid means of achieving symptomatic relief.”

Patients who chronically used opioids were more likely to have depression (25.4% vs. 12.5%) and anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.7%) during the baseline period of the study. Patients with chronic opioid use also were more likely to receive muscle relaxants (54.4% vs. 20.2%) and oral corticosteroids (18.4% vs. 9.6%), compared with patients without chronic opioid use, reported Dr. Sloan, vice president and immunology development strategy lead for UCB Pharma and of the Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and colleagues.

Claims for anti-TNF therapies, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and NSAIDs were similar for patients with and without chronic opioid use.

The patients in the study had claims with the specified diagnosis codes during Jan. 1, 2013–March 31, 2016 and were enrolled in medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months before and after the first qualifying ICD code. The study excluded patients with a history of cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer. Opioid claims within 7 days of a hospitalization or 2 days of an emergency department or urgent care visit were not included.

The investigators assessed patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and prior treatments during a 12-month baseline period prior to the index date. They examined opioid use and exposure to other treatments during a 12-month follow-up period after the index date. They defined chronic opioid use as at least 90 cumulative days of opioid use based on the supply value on opioid pharmacy claims. They summed the days’ supply for all opioid claims during the follow-up period.

Chronic use of opioids was most pronounced in the 917 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.0 diagnosis codes; 57.1% chronically used opioids during follow-up. Among 14,041 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.x codes, 76.7% chronically used opioids.

The data suggest that some patients may receive opioids before they receive recommended therapies. “If this is the case, there may be an opportunity to prevent chronic opioid use by intervening with recommended therapies earlier in the patient’s treatment course,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Sloan and colleagues noted that they had limited information about the timing of opioid use relative to ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis, opioid potency and dose, and the indication for which opioids were prescribed.

UCB Pharma funded the study. The authors are employees of UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Sloan VS et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180972.

About a quarter of all patients with ankylosing spondylitis, and more than half of those patients who were on Medicaid, received at least a 90-day supply of opioids in a year, based on an analysis of U.S. commercial claims data.

The findings were noted in 2012-2017 data from a cohort of 11,945 patients in the Truven Health MarketScan Research database. Of those patients given the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code 720.0, which is specific for ankylosing spondylitis, 23.5% of patients chronically used opioids. In the broader 720.x commercial claims cohort of 79,190 patients, the proportion who chronically used opioids was 27.3%.

More than 60% of the patients who chronically used opioids had a cumulative drug supply of 270 days or more.

“Patients with ankylosing spondylitis receive opioids with disturbing frequency,” said study author Victor S. Sloan, MD, and research colleagues in the June issue of the Journal of Rheumatology. Ankylosing spondylitis treatment guidelines “specify use of an NSAID as initial pharmacotherapy, with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy in cases of NSAID inefficacy or intolerance. However, for many patients, prescription opioids – while not addressing the underlying inflammation – may offer an inexpensive and rapid means of achieving symptomatic relief.”

Patients who chronically used opioids were more likely to have depression (25.4% vs. 12.5%) and anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.7%) during the baseline period of the study. Patients with chronic opioid use also were more likely to receive muscle relaxants (54.4% vs. 20.2%) and oral corticosteroids (18.4% vs. 9.6%), compared with patients without chronic opioid use, reported Dr. Sloan, vice president and immunology development strategy lead for UCB Pharma and of the Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and colleagues.

Claims for anti-TNF therapies, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and NSAIDs were similar for patients with and without chronic opioid use.

The patients in the study had claims with the specified diagnosis codes during Jan. 1, 2013–March 31, 2016 and were enrolled in medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months before and after the first qualifying ICD code. The study excluded patients with a history of cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer. Opioid claims within 7 days of a hospitalization or 2 days of an emergency department or urgent care visit were not included.

The investigators assessed patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and prior treatments during a 12-month baseline period prior to the index date. They examined opioid use and exposure to other treatments during a 12-month follow-up period after the index date. They defined chronic opioid use as at least 90 cumulative days of opioid use based on the supply value on opioid pharmacy claims. They summed the days’ supply for all opioid claims during the follow-up period.

Chronic use of opioids was most pronounced in the 917 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.0 diagnosis codes; 57.1% chronically used opioids during follow-up. Among 14,041 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.x codes, 76.7% chronically used opioids.

The data suggest that some patients may receive opioids before they receive recommended therapies. “If this is the case, there may be an opportunity to prevent chronic opioid use by intervening with recommended therapies earlier in the patient’s treatment course,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Sloan and colleagues noted that they had limited information about the timing of opioid use relative to ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis, opioid potency and dose, and the indication for which opioids were prescribed.

UCB Pharma funded the study. The authors are employees of UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Sloan VS et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180972.

About a quarter of all patients with ankylosing spondylitis, and more than half of those patients who were on Medicaid, received at least a 90-day supply of opioids in a year, based on an analysis of U.S. commercial claims data.

The findings were noted in 2012-2017 data from a cohort of 11,945 patients in the Truven Health MarketScan Research database. Of those patients given the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code 720.0, which is specific for ankylosing spondylitis, 23.5% of patients chronically used opioids. In the broader 720.x commercial claims cohort of 79,190 patients, the proportion who chronically used opioids was 27.3%.

More than 60% of the patients who chronically used opioids had a cumulative drug supply of 270 days or more.

“Patients with ankylosing spondylitis receive opioids with disturbing frequency,” said study author Victor S. Sloan, MD, and research colleagues in the June issue of the Journal of Rheumatology. Ankylosing spondylitis treatment guidelines “specify use of an NSAID as initial pharmacotherapy, with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] therapy in cases of NSAID inefficacy or intolerance. However, for many patients, prescription opioids – while not addressing the underlying inflammation – may offer an inexpensive and rapid means of achieving symptomatic relief.”

Patients who chronically used opioids were more likely to have depression (25.4% vs. 12.5%) and anxiety (20.9% vs. 11.7%) during the baseline period of the study. Patients with chronic opioid use also were more likely to receive muscle relaxants (54.4% vs. 20.2%) and oral corticosteroids (18.4% vs. 9.6%), compared with patients without chronic opioid use, reported Dr. Sloan, vice president and immunology development strategy lead for UCB Pharma and of the Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and colleagues.

Claims for anti-TNF therapies, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and NSAIDs were similar for patients with and without chronic opioid use.

The patients in the study had claims with the specified diagnosis codes during Jan. 1, 2013–March 31, 2016 and were enrolled in medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months before and after the first qualifying ICD code. The study excluded patients with a history of cancer other than nonmelanoma skin cancer. Opioid claims within 7 days of a hospitalization or 2 days of an emergency department or urgent care visit were not included.

The investigators assessed patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, and prior treatments during a 12-month baseline period prior to the index date. They examined opioid use and exposure to other treatments during a 12-month follow-up period after the index date. They defined chronic opioid use as at least 90 cumulative days of opioid use based on the supply value on opioid pharmacy claims. They summed the days’ supply for all opioid claims during the follow-up period.

Chronic use of opioids was most pronounced in the 917 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.0 diagnosis codes; 57.1% chronically used opioids during follow-up. Among 14,041 patients with Medicaid claims with 720.x codes, 76.7% chronically used opioids.

The data suggest that some patients may receive opioids before they receive recommended therapies. “If this is the case, there may be an opportunity to prevent chronic opioid use by intervening with recommended therapies earlier in the patient’s treatment course,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Sloan and colleagues noted that they had limited information about the timing of opioid use relative to ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis, opioid potency and dose, and the indication for which opioids were prescribed.

UCB Pharma funded the study. The authors are employees of UCB Pharma.

SOURCE: Sloan VS et al. J Rheumatol. 2019 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180972.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

The Opioid Crisis: An MDedge Psychcast Presentation

Opioid prescriptions declined 33% over 5 years

Fewer opioid retail prescriptions are being filled, according to a new report issued by the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force.

Opioid prescribing declined by 33% over a 5-year period based on the total number of opioid retail prescriptions filled. Total prescriptions declined from 251.8 million in 2013 to 168.8 million in 2018, according to the report.

The numbers come as the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show a leveling of deaths involving prescription opioids. The CDC data were most recently updated in January 2019 and cover the period 1999-2017.

A closer look shows that deaths involving prescription opioids, but not other synthetic narcotics, peaked in 2011 and have generally declined since then. Deaths involving other synthetic narcotics, however, have been rising, offsetting the reduction and keeping the total number of deaths involving opioids relatively stable between 2016 and 2017.

Other data released by the AMA Opioid Task Force show that physicians are increasing their use of state-level prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).

In 2017, there were 1.5 million physicians registered to use state PDMPs. That number rose to 1.97 million in 2019. And the physicians are using PDMPs. In 2018, physicians made 460 million PDMP queries, up 56% from 2017 and up 651% from 2014.

More education about opioid prescribing is being sought, with 700,000 physicians completing CME training and accessing other training related to opioid prescribing, pain management, screening for substance use disorders, and other related topics.

While the report does show positive trends, the task force is calling for more action, including more access to naloxone and better access to mental health treatment.

The report notes that more than 66,000 physicians and other health professionals have a federal waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, up more than 28,000 since 2016.

A number of policy recommendations are made in the report, including removing inappropriate administrative burdens or barriers that delay access to medications used in medication-assisted treatment (MAT); removing barriers to comprehensive pain care and rehabilitation programs, and reforming the civil and criminal justice system to help ensure access to high-quality, evidence-based care for opioid use disorder.

“We are at a crossroads in our nation’s efforts to end the opioid epidemic,” AMA Opioid Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, stated in the report. “It is time to end delays and barriers to medication-assisted treatment – evidence based care proven to save lives; time for payers, [pharmacy benefit managers] and pharmacy chains to reevaluate and revise policies that restrict opioid therapy to patients based on arbitrary thresholds; and time to commit to helping all patients access evidence-based care for pain and substance use disorders.”

Dr. Harris continued: “Physicians must continue to demonstrate leadership, but unless these actions occur, the progress we are making will not stop patients from dying.”

Fewer opioid retail prescriptions are being filled, according to a new report issued by the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force.

Opioid prescribing declined by 33% over a 5-year period based on the total number of opioid retail prescriptions filled. Total prescriptions declined from 251.8 million in 2013 to 168.8 million in 2018, according to the report.

The numbers come as the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show a leveling of deaths involving prescription opioids. The CDC data were most recently updated in January 2019 and cover the period 1999-2017.

A closer look shows that deaths involving prescription opioids, but not other synthetic narcotics, peaked in 2011 and have generally declined since then. Deaths involving other synthetic narcotics, however, have been rising, offsetting the reduction and keeping the total number of deaths involving opioids relatively stable between 2016 and 2017.

Other data released by the AMA Opioid Task Force show that physicians are increasing their use of state-level prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).

In 2017, there were 1.5 million physicians registered to use state PDMPs. That number rose to 1.97 million in 2019. And the physicians are using PDMPs. In 2018, physicians made 460 million PDMP queries, up 56% from 2017 and up 651% from 2014.

More education about opioid prescribing is being sought, with 700,000 physicians completing CME training and accessing other training related to opioid prescribing, pain management, screening for substance use disorders, and other related topics.

While the report does show positive trends, the task force is calling for more action, including more access to naloxone and better access to mental health treatment.

The report notes that more than 66,000 physicians and other health professionals have a federal waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, up more than 28,000 since 2016.

A number of policy recommendations are made in the report, including removing inappropriate administrative burdens or barriers that delay access to medications used in medication-assisted treatment (MAT); removing barriers to comprehensive pain care and rehabilitation programs, and reforming the civil and criminal justice system to help ensure access to high-quality, evidence-based care for opioid use disorder.

“We are at a crossroads in our nation’s efforts to end the opioid epidemic,” AMA Opioid Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, stated in the report. “It is time to end delays and barriers to medication-assisted treatment – evidence based care proven to save lives; time for payers, [pharmacy benefit managers] and pharmacy chains to reevaluate and revise policies that restrict opioid therapy to patients based on arbitrary thresholds; and time to commit to helping all patients access evidence-based care for pain and substance use disorders.”

Dr. Harris continued: “Physicians must continue to demonstrate leadership, but unless these actions occur, the progress we are making will not stop patients from dying.”

Fewer opioid retail prescriptions are being filled, according to a new report issued by the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force.

Opioid prescribing declined by 33% over a 5-year period based on the total number of opioid retail prescriptions filled. Total prescriptions declined from 251.8 million in 2013 to 168.8 million in 2018, according to the report.

The numbers come as the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show a leveling of deaths involving prescription opioids. The CDC data were most recently updated in January 2019 and cover the period 1999-2017.

A closer look shows that deaths involving prescription opioids, but not other synthetic narcotics, peaked in 2011 and have generally declined since then. Deaths involving other synthetic narcotics, however, have been rising, offsetting the reduction and keeping the total number of deaths involving opioids relatively stable between 2016 and 2017.

Other data released by the AMA Opioid Task Force show that physicians are increasing their use of state-level prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).

In 2017, there were 1.5 million physicians registered to use state PDMPs. That number rose to 1.97 million in 2019. And the physicians are using PDMPs. In 2018, physicians made 460 million PDMP queries, up 56% from 2017 and up 651% from 2014.

More education about opioid prescribing is being sought, with 700,000 physicians completing CME training and accessing other training related to opioid prescribing, pain management, screening for substance use disorders, and other related topics.

While the report does show positive trends, the task force is calling for more action, including more access to naloxone and better access to mental health treatment.

The report notes that more than 66,000 physicians and other health professionals have a federal waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, up more than 28,000 since 2016.

A number of policy recommendations are made in the report, including removing inappropriate administrative burdens or barriers that delay access to medications used in medication-assisted treatment (MAT); removing barriers to comprehensive pain care and rehabilitation programs, and reforming the civil and criminal justice system to help ensure access to high-quality, evidence-based care for opioid use disorder.

“We are at a crossroads in our nation’s efforts to end the opioid epidemic,” AMA Opioid Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, stated in the report. “It is time to end delays and barriers to medication-assisted treatment – evidence based care proven to save lives; time for payers, [pharmacy benefit managers] and pharmacy chains to reevaluate and revise policies that restrict opioid therapy to patients based on arbitrary thresholds; and time to commit to helping all patients access evidence-based care for pain and substance use disorders.”

Dr. Harris continued: “Physicians must continue to demonstrate leadership, but unless these actions occur, the progress we are making will not stop patients from dying.”

When adolescents visit the ED, 10% leave with an opioid

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

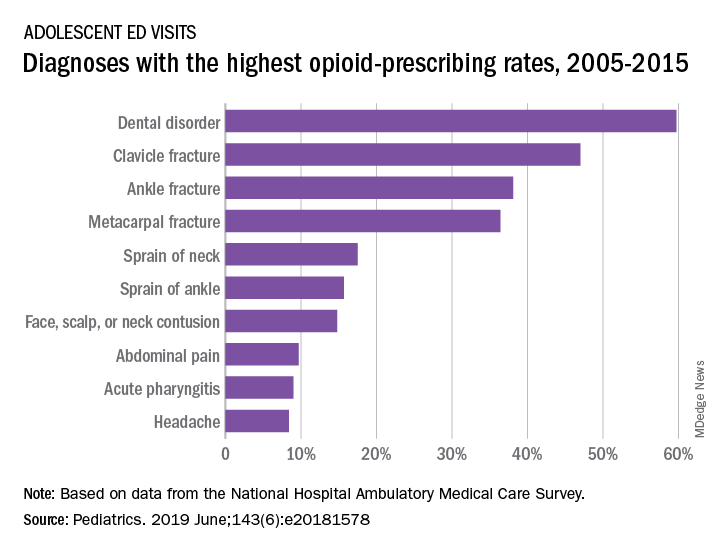

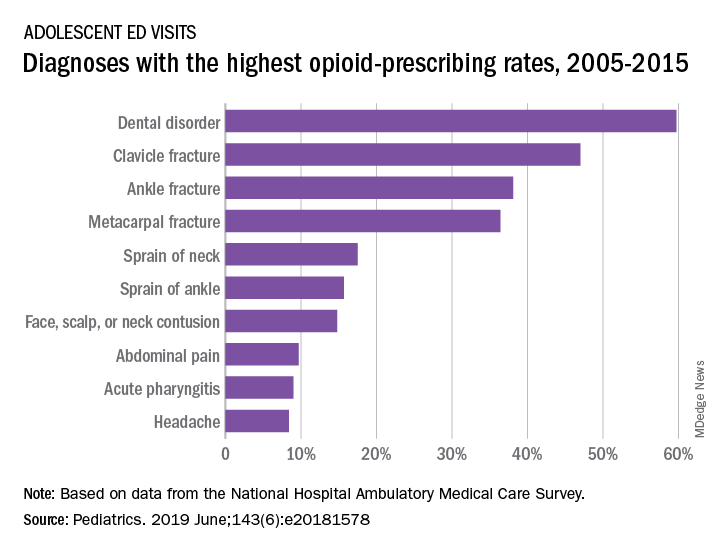

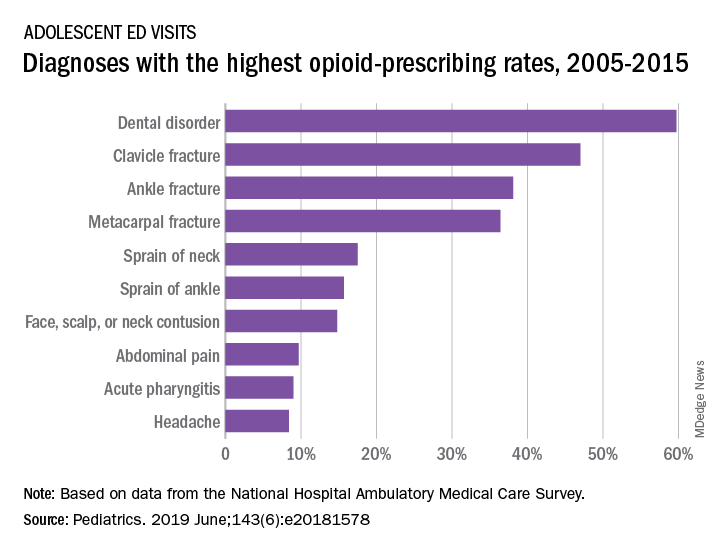

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

FROM PEDIATRICS

N.J. law, EMR alerts appear effective at reducing opioid prescriptions

WASHINGTON –

Researchers looked at prescribing patterns of doctors in the Penn Medicine health system, which straddles both the Philadelphia area and southern New Jersey, following the implementation of prescribing limits in New Jersey.

The law in question is a 5-day limit on new opioid prescriptions, which was passed in February 2017 and implemented in May 2017. Penn Medicine implemented an EMR alert in their New Jersey locations to alert physicians within the Penn Medicine system of the change in their state law 2 months after the law went into effect. Researchers looked at prescribing patterns before passage, during the transition between passage and the implementation of the EMR alert and following implementation of the EMR alert, as well as secondary outcomes such as rate of refills, telephone calls, and utilization.

“The implementation of the prescribing limit and EMR alert was associated with a decrease in the volume of opioids prescribed in acute prescriptions without changes in the rates of refills, telephone calls or utilization,” Margaret Lowenstein, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“This combination of the policy and the EMR alert may be an effective strategy to influence prescriber behavior,” she added.

Researchers compared outcomes before and after the implementation of the law in New Jersey, using prescribing patterns in Pennsylvania as the control. The cohort of patients was those with a new opioid prescription within Penn Medicine ambulatory nonteaching practices. It excluded specialties not represented in both states as well as patients with cancer, those in hospice and palliative care and those in treatment for opioid use disorder, since the law does not apply to those groups.

In New Jersey, there were 434 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 12 months prior to the implementation of the law, with 234 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 9 months after the EMR alert was implemented in New Jersey. In Pennsylvania, the cohort included 2,961 patients prior to the law going into effect and 1,677 after the EMR intervention went live in New Jersey.

For New Jersey, the morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per prescription was steady at about 350 during the period prior to the law’s implementation, but dropped to nearly 250 by the end of the postintervention period examined. In Pennsylvania, the prelaw implementation period had an MME per prescription a little higher than 200, which leveled off at around 200 during the postintervention period.

“In New Jersey, there is a significantly higher MME than in Pennsylvania and this difference persists in the transition period but what you see in the post period is a significantly greater decline in the MME per prescription in New Jersey as compared to the rate of change in Pa.,” Dr. Lowenstein said. “That difference was statistically significant.”

She said similar results were seen regarding the quantity of tablets prescribed. In New Jersey before the law’s passage, the number of tablets per prescription was close to 50, dropping down to about 35 post period. Pennsylvania saw a slight decrease from about 35 pills per prescription to about 33 during the same period.

No significant changes occurred in the other outcomes measured following implementation of the EMR alert.

Dr. Lowenstein noted that, because the transition period between the law going into effect and the implementation of the EMR alert was so short, whether the greater decreases in opioid prescriptions in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania was because of the law alone, the EMR alert alone, or both changes is unclear.

Based on the limited amount of change in prescribing patterns during the transition period, it appears that the EMR intervention may be driving the change, “but we weren’t powered to make that determination,” she added.

Dr. Lowenstein and her colleagues reported no disclosures.

WASHINGTON –

Researchers looked at prescribing patterns of doctors in the Penn Medicine health system, which straddles both the Philadelphia area and southern New Jersey, following the implementation of prescribing limits in New Jersey.

The law in question is a 5-day limit on new opioid prescriptions, which was passed in February 2017 and implemented in May 2017. Penn Medicine implemented an EMR alert in their New Jersey locations to alert physicians within the Penn Medicine system of the change in their state law 2 months after the law went into effect. Researchers looked at prescribing patterns before passage, during the transition between passage and the implementation of the EMR alert and following implementation of the EMR alert, as well as secondary outcomes such as rate of refills, telephone calls, and utilization.

“The implementation of the prescribing limit and EMR alert was associated with a decrease in the volume of opioids prescribed in acute prescriptions without changes in the rates of refills, telephone calls or utilization,” Margaret Lowenstein, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“This combination of the policy and the EMR alert may be an effective strategy to influence prescriber behavior,” she added.

Researchers compared outcomes before and after the implementation of the law in New Jersey, using prescribing patterns in Pennsylvania as the control. The cohort of patients was those with a new opioid prescription within Penn Medicine ambulatory nonteaching practices. It excluded specialties not represented in both states as well as patients with cancer, those in hospice and palliative care and those in treatment for opioid use disorder, since the law does not apply to those groups.

In New Jersey, there were 434 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 12 months prior to the implementation of the law, with 234 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 9 months after the EMR alert was implemented in New Jersey. In Pennsylvania, the cohort included 2,961 patients prior to the law going into effect and 1,677 after the EMR intervention went live in New Jersey.

For New Jersey, the morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per prescription was steady at about 350 during the period prior to the law’s implementation, but dropped to nearly 250 by the end of the postintervention period examined. In Pennsylvania, the prelaw implementation period had an MME per prescription a little higher than 200, which leveled off at around 200 during the postintervention period.

“In New Jersey, there is a significantly higher MME than in Pennsylvania and this difference persists in the transition period but what you see in the post period is a significantly greater decline in the MME per prescription in New Jersey as compared to the rate of change in Pa.,” Dr. Lowenstein said. “That difference was statistically significant.”

She said similar results were seen regarding the quantity of tablets prescribed. In New Jersey before the law’s passage, the number of tablets per prescription was close to 50, dropping down to about 35 post period. Pennsylvania saw a slight decrease from about 35 pills per prescription to about 33 during the same period.

No significant changes occurred in the other outcomes measured following implementation of the EMR alert.

Dr. Lowenstein noted that, because the transition period between the law going into effect and the implementation of the EMR alert was so short, whether the greater decreases in opioid prescriptions in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania was because of the law alone, the EMR alert alone, or both changes is unclear.

Based on the limited amount of change in prescribing patterns during the transition period, it appears that the EMR intervention may be driving the change, “but we weren’t powered to make that determination,” she added.

Dr. Lowenstein and her colleagues reported no disclosures.

WASHINGTON –

Researchers looked at prescribing patterns of doctors in the Penn Medicine health system, which straddles both the Philadelphia area and southern New Jersey, following the implementation of prescribing limits in New Jersey.

The law in question is a 5-day limit on new opioid prescriptions, which was passed in February 2017 and implemented in May 2017. Penn Medicine implemented an EMR alert in their New Jersey locations to alert physicians within the Penn Medicine system of the change in their state law 2 months after the law went into effect. Researchers looked at prescribing patterns before passage, during the transition between passage and the implementation of the EMR alert and following implementation of the EMR alert, as well as secondary outcomes such as rate of refills, telephone calls, and utilization.

“The implementation of the prescribing limit and EMR alert was associated with a decrease in the volume of opioids prescribed in acute prescriptions without changes in the rates of refills, telephone calls or utilization,” Margaret Lowenstein, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine.

“This combination of the policy and the EMR alert may be an effective strategy to influence prescriber behavior,” she added.

Researchers compared outcomes before and after the implementation of the law in New Jersey, using prescribing patterns in Pennsylvania as the control. The cohort of patients was those with a new opioid prescription within Penn Medicine ambulatory nonteaching practices. It excluded specialties not represented in both states as well as patients with cancer, those in hospice and palliative care and those in treatment for opioid use disorder, since the law does not apply to those groups.

In New Jersey, there were 434 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 12 months prior to the implementation of the law, with 234 patients receiving new prescriptions in the 9 months after the EMR alert was implemented in New Jersey. In Pennsylvania, the cohort included 2,961 patients prior to the law going into effect and 1,677 after the EMR intervention went live in New Jersey.

For New Jersey, the morphine milligram equivalent (MME) per prescription was steady at about 350 during the period prior to the law’s implementation, but dropped to nearly 250 by the end of the postintervention period examined. In Pennsylvania, the prelaw implementation period had an MME per prescription a little higher than 200, which leveled off at around 200 during the postintervention period.

“In New Jersey, there is a significantly higher MME than in Pennsylvania and this difference persists in the transition period but what you see in the post period is a significantly greater decline in the MME per prescription in New Jersey as compared to the rate of change in Pa.,” Dr. Lowenstein said. “That difference was statistically significant.”

She said similar results were seen regarding the quantity of tablets prescribed. In New Jersey before the law’s passage, the number of tablets per prescription was close to 50, dropping down to about 35 post period. Pennsylvania saw a slight decrease from about 35 pills per prescription to about 33 during the same period.

No significant changes occurred in the other outcomes measured following implementation of the EMR alert.

Dr. Lowenstein noted that, because the transition period between the law going into effect and the implementation of the EMR alert was so short, whether the greater decreases in opioid prescriptions in New Jersey relative to Pennsylvania was because of the law alone, the EMR alert alone, or both changes is unclear.

Based on the limited amount of change in prescribing patterns during the transition period, it appears that the EMR intervention may be driving the change, “but we weren’t powered to make that determination,” she added.

Dr. Lowenstein and her colleagues reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SGIM 2019

Risk of suicide attempt is higher in children of opioid users

according to an evaluation of a medical claims database from which a sample of more than 200,00 privately insured parents was evaluated.

Based on data collected between the years 2010 and 2016, the study raises the possibility that rising rates of opioid prescriptions and rising rates of suicide in adolescents and children are linked, said David A. Brent, of the University of Pittsburgh, and associates.