User login

Polydactyly of the Hand

Polydactyly is the presence of extra digits. Its incidence is likely underestimated because many practitioners treat simple “nubbins” without referring them to orthopedic specialists.1-3 Polydactyly can be detected by ultrasound as early as 14 weeks’ gestational age, with partial autoamputation seen in most isolated polydactylies.4 The thumb, responsible for 40% of hand function, must be able to oppose the other digits with a stable pinch.5 Polydactyly encumbers this motion when the duplicated digits deviate from normal alignment. Ezaki6 noted that the anatomy is better described as “split” than “duplicated.” There are many dichotomous ways to classify polydactyly: preaxial (radial) versus postaxial (ulnar), thumb versus triphalangeal, simple versus complex (Figure 1). Mixed polydactyly is defined as the presence of preaxial and postaxial polydactyly.7 Surgical management seeks to allow normal hand function and to restore cosmesis.

Epidemiology

Sun and colleagues8 reported the overall polydactyly incidence as 2 per 1000 live births in China from 1998 to 2009, with a slight male predominance; polydactyly was also 3 times more common than syndactyly in this population. Ivy,9 in a 5-year audit of Pennsylvania Department of Health records, found polydactyly to be the fourth most common congenital anomaly after clubfoot, cleft lip/palate, and spina bifida. Thumb duplication occurs in 0.08 to 1.4 per 1000 live births and is more common in American Indians and Asians than in other races.5,10 It occurs in a male-to-female ratio of 2.5 to 1 and is most often unilateral.5 Postaxial polydactyly is predominant in black infants; it is most often inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, if isolated, or in an autosomal recessive pattern, if syndromic.1 A prospective San Diego study of 11,161 newborns found postaxial type B polydactyly in 1 per 531 live births (1 per 143 black infants, 1 per 1339 white infants); 76% of cases were bilateral, and 86% had a positive family history.3 In patients of non-African descent, it is associated with anomalies in other organs. Central duplication is rare and often autosomal dominant.5,10

Genetics and Development

As early as 1896, the heritability of polydactyly was noted.11 As of 2010, polydactyly has been associated with 310 diseases.12 Ninety-nine genes, most involved in regulation of anterior-posterior formation of the limb bud, have been implicated.12,13

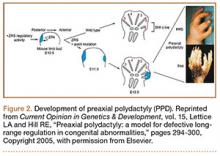

The upper limb begins to form at day 26 in utero.14 Apoptosis in the interdigital necrotic zones results in the formation of individual digits. It is presumed that, in polydactyly, the involved tissue is hypoplastic because of an abnormal interaction between mesoderm and ectoderm.5 Presence of an apical ectodermal ridge determines the formation of a limb bud, and on it the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) dictates preaxial and postaxial alignment.14,15 The ZPA is located on the posterior zone of the developing limb bud. The levels of GLI3, a zinc finger-containing DNA-binding protein, are highest in the anterior area, and HAND2, a basic helix-loop-helix DNA-binding protein, is found in the ZPA. This polarity promotes sonic hedgehog (Shh) gene expression in the posterior region, which in turn prevents GLI3 cleavage into its repressed form. GLI3R (repressed) and GLI3A (active) concentrations are highest, therefore, in the anterior and posterior portions of the bud, respectively. The GLI3A:GLI3R ratio is responsible for the identity and number of digits in the hand (ie, the thumb develops in regions of high GLI3R). GLI and Shh mutations lead to polydactylous hands with absent thumbs (Figure 2).16

Ciliopathies have also been shown to cause postaxial polydactyly, possibly because of the role that nonmotile cilia play in hedgehog signaling.17 Mutations in Shh genomic regulators cause preaxial polydactyly.18 HoxD activates Shh in the ZPA; HoxD13 mutations are associated with synpolydactyly.16,19 In each of these mutations, Shh production is altered, and some form of polydactyly results.

Associations

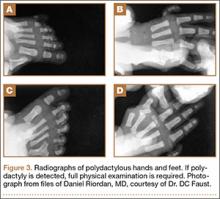

Many syndromes have been associated with polydactyly. Not all polydactyly is associated with other disorders, but the more complex the polydactyly, the more likely that other anomalies are present. Every patient who presents with polydactyly should have a full history taken and a physical examination performed (Figure 3). Any patient with syndromic findings or atypical presentations (eg, triphalangism, postaxial polydactyly in a patient of non-African descent, central and index polydactyly) should be referred to a geneticist.

Classifications

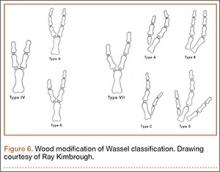

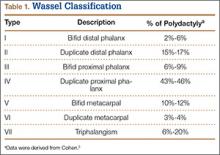

The Wassel20 classification describes the anatomical presentation of thumb duplication on the basis of 70 cases in Iowa (Figures 4, 5; Table 1). Because some duplications fall outside the Wassel classification, many researchers have proposed modifications (Figure 6).21-25

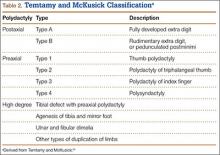

The Temtamy and McKusick10 classification, which is the product of geneticists, classifies duplications by grouping genetically related presentations (Table 2). It provides the most commonly used postaxial classification, with type A being a fully developed digit and type B a rudimentary and pedunculated digit, informally referred to as a nubbin. Type B is more common than type A. Given inheritance patterns, it is assumed that type A is likely multifactorial and type B autosomal dominant.10 Thumb polydactyly inheritance is still unclear. The other types of preaxial polydactyly and high degrees of polydactyly are rare but seem to be passed on in an autosomal dominant fashion on pedigree analysis.10

The Stelling and Turek classification presents the duplication from a tissue perspective: Type I duplication is a rudimentary mass devoid of other tissue elements; type II is a subtotal duplication with some normal structures; and type III is a duplication of the entire “osteoarticular column,” including the metacarpal.1 It is interesting to note that histology of type I duplications shows neuroma-like tissue.26-28 Again, normal is a relative term because, in polydactyly, the duplications are hypoplastic and deviated, with anomalous anatomy.

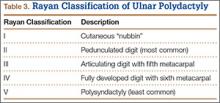

The Rayan classification describes ulnar polydactyly and was derived from a case study series of 148 patients in Oklahoma (Table 3).29

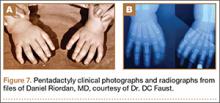

There are also some complex polydactylies that are not easily classified: ulnar dimelia, cleft hand, pentadactyly, and hyperphalangism. Ulnar dimelia, also known as “mirror hand,” is typically 7 digits with no thumb, but other variations are seen. The radius is often absent, and the elbow is abnormal. There is some debate about whether it is a fusion of 2 hands. Pentadactyly, or the 5-fingered hand, appears as 5 triphalangeal digits with no thumb (Figure 7).

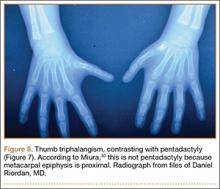

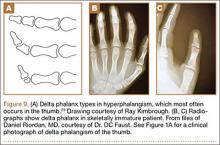

Isolated thumb triphalangism might appear similar to pentadactyly. Miura30,31 pointed out that the radial digit in the pentadactylous hand may be opposable (thumb-like) or nonopposable; in his studies, the patients with the opposable thumb had a metacarpal with a proximal epiphysis (Figure 8). Consequently, the triphalangeal thumb metacarpal with a distal epiphysis is true pentadactyly, whereas that with a proximal epiphysis is hyperphalangism (Figure 9). Treatment of these complex polydactylies involves the same underlying principles as for preaxial and postaxial polydactyly, albeit with additional proximal upper extremity considerations.

When to Operate (Timing)

Ezaki6 recommended surgical intervention at age 6 to 9 months, before fine motor skills have developed with the abnormal anatomy. Cortical learning occurs as the child begins prehensile activities before 6 months, but the risks of anesthesia outweigh functional benefits until the child is older. Waiting until 1 year of age is not uncommon, though surgery at an earlier age may be beneficial if the polydactyly affects hand function.32 It is not uncommon to wait with the more balanced thumb polydactylies to assess thumb function. Hypoplasia might also delay surgical intervention until there is enough tissue inventory for reconstruction. Wassel20 noted that surgical intervention ideally occurs before the supernumerary elements displace the normal elements, as tends to happen with growth. Suture ligation is an option in the neonatal unit for some pedunculated digits.33 Studies have shown satisfactory results in adults treated for polydactyly, if the patient presents later than expected.34

Surgical Considerations

Knavel recommended simple excision, stating that “ablation requires no ingenuity and creates no problems.”5 This belief, though true for some duplications, will not lead to the best outcome for more complex polydactylies. The goal of surgery is a stable and well-aligned thumb for pinch and prehensile activity, as well as a cosmetically pleasing hand. Incisions should not be made linearly along the axis of the digit, as the scar will cause deviation with growth.24

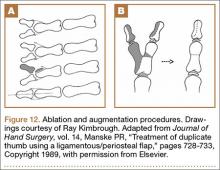

Wassel type I polydactyly might appear incidentally as a broad thumb, in which case it requires no intervention (Figure 10). However, in Wassel types I and II polydactyly with deformity, the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure is useful for both bifid and duplicated phalanges (Figure 11).5,6,30,32,35 Collateral ligaments may need to be released in type II because of difficulty in opposing the tissue. Cosmetic results with Bilhaut-Cloquet are unpredictable. The original technique required symmetrically sized digits; results today have been improved with microtechniques and preservation of an entire nail.36 Another option is ablation of the more hypoplastic osseous element and soft-tissue augmentation of the residual digit. The theme of ablation and augmentation is seen throughout the literature for the surgical treatment of polydactyly (Figure 12).1

For type III polydactyly, the bifid proximal phalanx is narrowed by resection and realigned with osteotomy of the remaining diaphysis. Type IV polydactyly, the most common thumb duplication, often requires advancement of the abductor pollicis brevis to the base of the proximal phalanx to aid in metacarpophalangeal (MCP) stabilization, abduction, and opposition. The metacarpal head, if broad and with 2 facets, can be shaped to form a single articulating surface. The metacarpal, occasionally with the proximal phalanx, often requires realignment by closing wedge osteotomy. Last, tendons on the resected bony elements should be rebalanced on the remaining digit, and anomalous slips must be released. For instance, given a radial insertion of the long flexor tendon on the distal phalanx, the tendon should be moved centrally. A strong flexor or extensor tendon on the amputated digit should be transferred to the remaining digit.24

Types V and VI are treated similarly to type IV, with the addition of a first web space Z-plasty or web widening if there is thenar eminence contracture. Acral transposition has also been described, with transposition of the tip of the ablated digit in place of the tip of the kept digit; this technique is ideal if one digit has a more normal proximal part while the other has a more normal distal part (Figure 13).35

Type VII thumb polydactyly, the type most likely inherited and associated with other disorders, should be treated like type VI. The nail should be preserved; amputation of the distal phalanx is not advised. Resection of the delta phalanx or 1 interphalangeal (IP) joint is an option. Articular surfaces will remodel if done before the age of 1 year. If the thenar eminence is hypoplastic, then Huber transfer of the abductor digiti minimi should be considered.37 Resection of the triphalangeal thumb is also advised, even if the biphalangeal thumb is more hypoplastic, with transfer of the ligaments and tendons, as described earlier.5,6,24,30,32,35

Thumb triphalangism, if isolated, and hyperphalangism in the other digits, can be treated with resection of the delta phalanx or one of the IP joints if it is affecting function or cosmesis.1,6 Wood and Flatt23 recommended early resection of a thumb delta phalanx because of the likelihood of deviation that impedes thumb function. For children, they recommended delta phalanx resection and Kirschner wire fixation for 6 weeks; for adults, they recommended resection or fusion of the joint, with osteotomy as needed for deviation.23,24 For thumb triphalangism, multiple surgeries are the norm, as Wood24 reported in his study of 21 patients who underwent 78 operations in total.

Index polydactyly may present as a simple pedunculated skin tag, which can be simply excised, or as a more complex musculoskeletal duplication. More complex presentations can be treated with procedures similar to those used for the thumb. Typically, the additional digit is radially deviated and angulated, eventually leading to impingement of thumb pinch and the first web space. Ray amputation is also an option if no reconstructive surgery will produce the stable, sensate radial pinch that is essential to hand function.32

Ring-finger polydactyly and long-finger polydactyly are often complicated by some element of syndactyly, resulting in a relative paucity of skin (Figure 14). There is failure of both formation (hypoplasia) and differentiation (syndactyly). The hypoplasia particularly affects the function of these digits by tethering them; multiple surgeries to restore proper hand function are the norm.1 Reconstructive surgery for these digits requires preoperative tissue inventory followed by resection and augmentation; as in syndactyly, skin for coverage is at a premium. Creation of a 3-fingered hand is an option.23

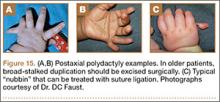

Temtamy and McKusick10 type A little-finger polydactyly is treated similarly to the thumb, with the caveat that hypothenar and intrinsic muscles that insert on the resected little finger are transferred to the remaining digit. In contrast to thumb polydactyly, the extrinsic musculature tends to be in good position. Suture ligation of type B polydactyly, as described by Flatt, is likely more common than orthopedists appreciate, as pediatricians and neonatal unit practitioners commonly perform this procedure in the nursery.1-3 It has been described with 2-0 Vicryl3 (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) and 4-0 silk sutures,32 with the goal of necrosis and autoamputation. Parents should be told the finger generally falls off about 10 days (range, 4-21 days) after ligation.3 Multiple authors have cited a report of exsanguination from suture ligation, but we could not locate the primary source. It is advisable to wait until a patient is 6 months of age if planning to resect the nubbin in the operating room, given the anesthesia risk and the lack of functional impairment. Katz and Linder33 indicated they remove type B polydactyly in the nursery suite used for circumcisions; they use anesthetizing cream on the skin, and sharp excision with a scalpel, followed by direct pressure and Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) application. Suture ligation is recommended only if there is a narrow, thin (<2 mm) soft-tissue stalk; any broad or bony stalk necessitates surgical removal to avoid neuroma formation and failure of autonecrosis (Figure 15).27 Other options are a single swipe of a scalpel and elliptical excision; sharp transaction of the digital nerve with subsequent retraction is advised to avoid neuroma formation.2

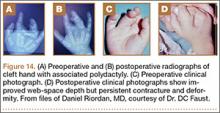

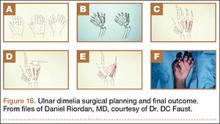

Barton described ulnar dimelia operations as “spare parts surgery.”1 Extra digits are ablated and a thumb created (Figure 16). The hand might have a digit in relatively good rotational position for thumbplasty, or the principles of pollicization may need to be used. If the patient is already using the hand, the surgeon should note which finger the patient uses as a thumb.24 Any accompanying wrist flexion contracture must be corrected with careful attention to musculotendinous balancing. Because the forearm and elbow, and occasionally even the more proximal limb, will be abnormal in this disorder, multiple surgeries are again the norm.1

Pentadactyly is treated like thumb hypoplasia, with first web space creation.1

Complications

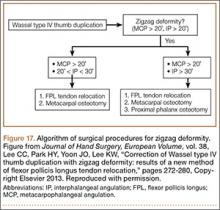

In polydactyly, a reoperation rate of up to 25% has been reported, with most reoperations performed because of residual or subsequent deformity.5,30,31,38 Risk factors for reoperation are type IV thumb duplication, preoperative “zigzag” deformity, and radially deviated thumb elements at presentation.5 The delta phalanx may not show on radiographs until the patient is 18 months old, but functional deformity will worsen as long as it is present. Zigzag deformity may be due to the delta phalanx or to musculotendinous imbalance, such as a radially inserted flexor pollicis longus (FPL) or lack of stable MCP abduction. Miura31 found that careful reconstruction of the joint capsule and thenar muscles from the ablated digit to the remnant digit is the key to a successful initial surgery. Lee and colleagues39 defined zigzag deformity as more than 20° MCP and IP angulation; for cases present before surgery, they recommended FPL relocation by the pullout technique in addition to osteotomies to prevent further interphalangeal deviation (Figures 17, 18).

Abnormal physeal growth, joint instability, and stiffness can all occur. Stiffness is particularly difficult to treat but seldom presents a functional problem. Joint enlargement, which is not uncommon, results from either broad articular surfaces or retained cartilage from the perichondral ring after resection that later ossifies.5,38 Nubbin-type duplications may not fall off after suture ligation, necessitating further excision, and a cosmetic bump is seen after 40% of suture ligations.3 Patillo and Rayan28 and Rayan and Frey29 warned against suture ligation unless the nubbin has a small stalk because of the possibility of infection and gangrene. The excised nubbin tissue is histologically nervous, and there have been reports of painful neuromas in the remaining scar of a ligated nubbin that respond well to excision.26,27,40 It is thought that these painful lesions form because the ligature prevents the digital nerves to the vestigial digit from retracting.27 Nail deformity and IP joint stiffness are seen with the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure, though often finger function remains satisfactory.

Conclusion

Polydactyly is a common congenital hand abnormality. Its true incidence is unknown because of inconsistent documentation. Surgeons must strive for a functional, cosmetic hand, given a diverse set of possible anomalies. Hypoplasia is the rule; tissue should be ablated and augmented as necessary. Musculotendinous insertions may need to be centralized. Patients’ family members should always be counseled that more surgery may be needed in the future, as further deformity can occur with growth. Surgically corrected thumb duplications will be stiffer, shorter, and thinner than their normal counterparts. Nail ridges are common. However, it should be noted that 88% of these patients are satisfied with their results.41 Some amount of contracture and abnormal function should be expected with index-, long-, and ring-finger duplications. The only remnant of type B postaxial duplications may be a slight discoloration or bump, though stiffness and deformity can happen with a type A deformity. A “duplicated” digit that requires surgical correction will never be completely normal, but acceptable function is routinely achievable.

1. Graham TJ, Ress AM. Finger polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):49-64.

2. Abzug JM, Kozin SH. Treatment of postaxial polydactyly type B. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1223-1225.

3. Watson BT, Hennrikus WL. Postaxial type-B polydactyly—prevalence and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(1):65-68.

4. Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Fetal polydactyly diagnosis during early pregnancy: clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):755-758.

5. Cohen MS. Thumb duplication. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):17-27.

6. Ezaki M. Radial polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):577-588.

7. Nathan PA, Keniston RC. Crossed polydactyly: case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(6):847-849.

8. Sun G, Xu ZM, Liang JF, Li L, Tang DX. Twelve-year prevalence of common neonatal congenital malformations in Zhejiang Province, China. World J Pediatr. 2011;7(4):331-336.

9. Ivy RH. Congenital anomalies as recorded on birth certificates in the Division of Vital Statistics of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, for the period of 1951–1955, inclusive. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1957;20(5):400-411.

10. Temtamy SA, McKusick VA. Polydactyly as a part of syndromes. In: Bergsma D, ed. Mudge JR, Paul NW, Conde Greene S, associate eds. The Genetics of Hand Malformations. New York, NY: Liss. Birth Defects Original Article Series. 1978;14(3):364-439.

11. Gould W, Pyle L. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. New York, NY: Bell; 1896.

12. Biesecker LG. Polydactyly: how many disorders and how many genes: 2010 update. Dev Dyn. 2011;250(5):931-942.

13. Grzeschik K. Human limb malformations; an approach to the molecular basis of development. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;46(7):983-991.

14. Zaleske DJ. Development of the upper limb. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):383-390.

15. Beatty E. Upper limb tissue differentiation in the human embryo. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):391-404.

16. Anderson E, Peluso S, Lettice LA, Hill RE. Human limb abnormalities caused by disruption of hedgehog signaling. Trends Genet. 2012;28(8):364-373.

17. Ware SM, Aygun MG, Heldebrandt F. Spectrum of clinical diseases caused by disorders of primary cilia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(5):444-450.

18. Lettice LA, Hill RE. Preaxial polydactyly: a model for defective long-range regulation in congenital abnormalities. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(3):294-300.

19. Al-Qattan MA. Type II familial synpolydactyly: report on two families with an emphasis on variations of expression. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(1):112-114.

20. Wassel HD. The results of surgery for polydactyly of the thumb. Clin Orthop. 1969;(64):175-193.

21. Blauth W, Olason AT. Classification of polydactyly of the hands and feet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(6):334-344.

22. Wood VE. Super digit. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):673-684.

23. Wood VE, Flatt AE. Congenital triangular bones in the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(3):179-193.

24. Wood VE. Polydactyly and the triphalangeal thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(5):436-444.

25. Zuidam JM, Selles RW, Ananta M, Runia J, Hovius SER. A classification system of radial polydactyly: inclusion of triphalangeal thumb and triplication. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(3):373-377.

26. Leber GE, Gosain AK. Surgical excision of pedunculated supernumerary digits prevents traumatic amputation neuromas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(2):108-112.

27. Mullick S, Borschel GH. A selective approach to treatment of ulnar polydactyly: preventing painful neuroma and incomplete excision. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;27(1):39-42.

28. Patillo D, Rayan GM. Complications of suture ligation ablation for ulnar polydactyly: a report of two cases. Hand (N Y). 2011;6(1):102-105.

29. Rayan GM, Frey B. Ulnar polydactyly. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1449-1454.

30. Miura T. Triphalangeal thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(5):587-594.

31. Miura T. Duplicated thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3):470-481.

32. Simmons BP. Polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):545-566.

33. Katz K, Linder N. Postaxial type B polydactyly treated by excision in the neonatal nursery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(4):448-449.

34. Manohar A, Beard AJ. Outcome of reconstruction for duplication of the thumb in adults aged over 40. Hand Surg. 2011;16(2):207-210.

35. Watt AJ, Chung KC. Duplication. Hand Clin. 2009;25(2):215-228.

36. Tonkin MA. Thumb duplication: concepts and techniques. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(1):1-17.

37. Huber E. Relief operation in the case of paralysis of the median nerve. J Hand Surg Eur. 2004;29(1):35-37.

38. Mih AD. Complications of duplicate thumb reconstruction. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):143-149.

39. Lee CC, Park HY, Yoon JO, Lee KW. Correction of Wassel type IV thumb duplication with zigzag deformity: results of a new method of flexor pollicis longus tendon relocation. J Hand Surg Eur. 2013;38(3):272-280.

40. Hare PJ. Rudimentary polydactyly. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66(11):402-408.

41. Yen CH, Chan WL, Leung HB, Mak KH. Thumb polydactyly: clinical outcome after reconstruction. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2006;14(3):295-302.

42. Edmunds JO. A tribute to Daniel C. Riordan, MD (1917–2012). Tulane University School of Medicine, Department of Orthopaedics website. http://tulane.edu/som/departments/orthopaedics/news-and-events/danriordantribute.cfm. Accessed March 31, 2015.

43. Faust DC, Herms R. Daniel C. Riordan, MD, 1917–2012. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(1):202-205.

Polydactyly is the presence of extra digits. Its incidence is likely underestimated because many practitioners treat simple “nubbins” without referring them to orthopedic specialists.1-3 Polydactyly can be detected by ultrasound as early as 14 weeks’ gestational age, with partial autoamputation seen in most isolated polydactylies.4 The thumb, responsible for 40% of hand function, must be able to oppose the other digits with a stable pinch.5 Polydactyly encumbers this motion when the duplicated digits deviate from normal alignment. Ezaki6 noted that the anatomy is better described as “split” than “duplicated.” There are many dichotomous ways to classify polydactyly: preaxial (radial) versus postaxial (ulnar), thumb versus triphalangeal, simple versus complex (Figure 1). Mixed polydactyly is defined as the presence of preaxial and postaxial polydactyly.7 Surgical management seeks to allow normal hand function and to restore cosmesis.

Epidemiology

Sun and colleagues8 reported the overall polydactyly incidence as 2 per 1000 live births in China from 1998 to 2009, with a slight male predominance; polydactyly was also 3 times more common than syndactyly in this population. Ivy,9 in a 5-year audit of Pennsylvania Department of Health records, found polydactyly to be the fourth most common congenital anomaly after clubfoot, cleft lip/palate, and spina bifida. Thumb duplication occurs in 0.08 to 1.4 per 1000 live births and is more common in American Indians and Asians than in other races.5,10 It occurs in a male-to-female ratio of 2.5 to 1 and is most often unilateral.5 Postaxial polydactyly is predominant in black infants; it is most often inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, if isolated, or in an autosomal recessive pattern, if syndromic.1 A prospective San Diego study of 11,161 newborns found postaxial type B polydactyly in 1 per 531 live births (1 per 143 black infants, 1 per 1339 white infants); 76% of cases were bilateral, and 86% had a positive family history.3 In patients of non-African descent, it is associated with anomalies in other organs. Central duplication is rare and often autosomal dominant.5,10

Genetics and Development

As early as 1896, the heritability of polydactyly was noted.11 As of 2010, polydactyly has been associated with 310 diseases.12 Ninety-nine genes, most involved in regulation of anterior-posterior formation of the limb bud, have been implicated.12,13

The upper limb begins to form at day 26 in utero.14 Apoptosis in the interdigital necrotic zones results in the formation of individual digits. It is presumed that, in polydactyly, the involved tissue is hypoplastic because of an abnormal interaction between mesoderm and ectoderm.5 Presence of an apical ectodermal ridge determines the formation of a limb bud, and on it the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) dictates preaxial and postaxial alignment.14,15 The ZPA is located on the posterior zone of the developing limb bud. The levels of GLI3, a zinc finger-containing DNA-binding protein, are highest in the anterior area, and HAND2, a basic helix-loop-helix DNA-binding protein, is found in the ZPA. This polarity promotes sonic hedgehog (Shh) gene expression in the posterior region, which in turn prevents GLI3 cleavage into its repressed form. GLI3R (repressed) and GLI3A (active) concentrations are highest, therefore, in the anterior and posterior portions of the bud, respectively. The GLI3A:GLI3R ratio is responsible for the identity and number of digits in the hand (ie, the thumb develops in regions of high GLI3R). GLI and Shh mutations lead to polydactylous hands with absent thumbs (Figure 2).16

Ciliopathies have also been shown to cause postaxial polydactyly, possibly because of the role that nonmotile cilia play in hedgehog signaling.17 Mutations in Shh genomic regulators cause preaxial polydactyly.18 HoxD activates Shh in the ZPA; HoxD13 mutations are associated with synpolydactyly.16,19 In each of these mutations, Shh production is altered, and some form of polydactyly results.

Associations

Many syndromes have been associated with polydactyly. Not all polydactyly is associated with other disorders, but the more complex the polydactyly, the more likely that other anomalies are present. Every patient who presents with polydactyly should have a full history taken and a physical examination performed (Figure 3). Any patient with syndromic findings or atypical presentations (eg, triphalangism, postaxial polydactyly in a patient of non-African descent, central and index polydactyly) should be referred to a geneticist.

Classifications

The Wassel20 classification describes the anatomical presentation of thumb duplication on the basis of 70 cases in Iowa (Figures 4, 5; Table 1). Because some duplications fall outside the Wassel classification, many researchers have proposed modifications (Figure 6).21-25

The Temtamy and McKusick10 classification, which is the product of geneticists, classifies duplications by grouping genetically related presentations (Table 2). It provides the most commonly used postaxial classification, with type A being a fully developed digit and type B a rudimentary and pedunculated digit, informally referred to as a nubbin. Type B is more common than type A. Given inheritance patterns, it is assumed that type A is likely multifactorial and type B autosomal dominant.10 Thumb polydactyly inheritance is still unclear. The other types of preaxial polydactyly and high degrees of polydactyly are rare but seem to be passed on in an autosomal dominant fashion on pedigree analysis.10

The Stelling and Turek classification presents the duplication from a tissue perspective: Type I duplication is a rudimentary mass devoid of other tissue elements; type II is a subtotal duplication with some normal structures; and type III is a duplication of the entire “osteoarticular column,” including the metacarpal.1 It is interesting to note that histology of type I duplications shows neuroma-like tissue.26-28 Again, normal is a relative term because, in polydactyly, the duplications are hypoplastic and deviated, with anomalous anatomy.

The Rayan classification describes ulnar polydactyly and was derived from a case study series of 148 patients in Oklahoma (Table 3).29

There are also some complex polydactylies that are not easily classified: ulnar dimelia, cleft hand, pentadactyly, and hyperphalangism. Ulnar dimelia, also known as “mirror hand,” is typically 7 digits with no thumb, but other variations are seen. The radius is often absent, and the elbow is abnormal. There is some debate about whether it is a fusion of 2 hands. Pentadactyly, or the 5-fingered hand, appears as 5 triphalangeal digits with no thumb (Figure 7).

Isolated thumb triphalangism might appear similar to pentadactyly. Miura30,31 pointed out that the radial digit in the pentadactylous hand may be opposable (thumb-like) or nonopposable; in his studies, the patients with the opposable thumb had a metacarpal with a proximal epiphysis (Figure 8). Consequently, the triphalangeal thumb metacarpal with a distal epiphysis is true pentadactyly, whereas that with a proximal epiphysis is hyperphalangism (Figure 9). Treatment of these complex polydactylies involves the same underlying principles as for preaxial and postaxial polydactyly, albeit with additional proximal upper extremity considerations.

When to Operate (Timing)

Ezaki6 recommended surgical intervention at age 6 to 9 months, before fine motor skills have developed with the abnormal anatomy. Cortical learning occurs as the child begins prehensile activities before 6 months, but the risks of anesthesia outweigh functional benefits until the child is older. Waiting until 1 year of age is not uncommon, though surgery at an earlier age may be beneficial if the polydactyly affects hand function.32 It is not uncommon to wait with the more balanced thumb polydactylies to assess thumb function. Hypoplasia might also delay surgical intervention until there is enough tissue inventory for reconstruction. Wassel20 noted that surgical intervention ideally occurs before the supernumerary elements displace the normal elements, as tends to happen with growth. Suture ligation is an option in the neonatal unit for some pedunculated digits.33 Studies have shown satisfactory results in adults treated for polydactyly, if the patient presents later than expected.34

Surgical Considerations

Knavel recommended simple excision, stating that “ablation requires no ingenuity and creates no problems.”5 This belief, though true for some duplications, will not lead to the best outcome for more complex polydactylies. The goal of surgery is a stable and well-aligned thumb for pinch and prehensile activity, as well as a cosmetically pleasing hand. Incisions should not be made linearly along the axis of the digit, as the scar will cause deviation with growth.24

Wassel type I polydactyly might appear incidentally as a broad thumb, in which case it requires no intervention (Figure 10). However, in Wassel types I and II polydactyly with deformity, the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure is useful for both bifid and duplicated phalanges (Figure 11).5,6,30,32,35 Collateral ligaments may need to be released in type II because of difficulty in opposing the tissue. Cosmetic results with Bilhaut-Cloquet are unpredictable. The original technique required symmetrically sized digits; results today have been improved with microtechniques and preservation of an entire nail.36 Another option is ablation of the more hypoplastic osseous element and soft-tissue augmentation of the residual digit. The theme of ablation and augmentation is seen throughout the literature for the surgical treatment of polydactyly (Figure 12).1

For type III polydactyly, the bifid proximal phalanx is narrowed by resection and realigned with osteotomy of the remaining diaphysis. Type IV polydactyly, the most common thumb duplication, often requires advancement of the abductor pollicis brevis to the base of the proximal phalanx to aid in metacarpophalangeal (MCP) stabilization, abduction, and opposition. The metacarpal head, if broad and with 2 facets, can be shaped to form a single articulating surface. The metacarpal, occasionally with the proximal phalanx, often requires realignment by closing wedge osteotomy. Last, tendons on the resected bony elements should be rebalanced on the remaining digit, and anomalous slips must be released. For instance, given a radial insertion of the long flexor tendon on the distal phalanx, the tendon should be moved centrally. A strong flexor or extensor tendon on the amputated digit should be transferred to the remaining digit.24

Types V and VI are treated similarly to type IV, with the addition of a first web space Z-plasty or web widening if there is thenar eminence contracture. Acral transposition has also been described, with transposition of the tip of the ablated digit in place of the tip of the kept digit; this technique is ideal if one digit has a more normal proximal part while the other has a more normal distal part (Figure 13).35

Type VII thumb polydactyly, the type most likely inherited and associated with other disorders, should be treated like type VI. The nail should be preserved; amputation of the distal phalanx is not advised. Resection of the delta phalanx or 1 interphalangeal (IP) joint is an option. Articular surfaces will remodel if done before the age of 1 year. If the thenar eminence is hypoplastic, then Huber transfer of the abductor digiti minimi should be considered.37 Resection of the triphalangeal thumb is also advised, even if the biphalangeal thumb is more hypoplastic, with transfer of the ligaments and tendons, as described earlier.5,6,24,30,32,35

Thumb triphalangism, if isolated, and hyperphalangism in the other digits, can be treated with resection of the delta phalanx or one of the IP joints if it is affecting function or cosmesis.1,6 Wood and Flatt23 recommended early resection of a thumb delta phalanx because of the likelihood of deviation that impedes thumb function. For children, they recommended delta phalanx resection and Kirschner wire fixation for 6 weeks; for adults, they recommended resection or fusion of the joint, with osteotomy as needed for deviation.23,24 For thumb triphalangism, multiple surgeries are the norm, as Wood24 reported in his study of 21 patients who underwent 78 operations in total.

Index polydactyly may present as a simple pedunculated skin tag, which can be simply excised, or as a more complex musculoskeletal duplication. More complex presentations can be treated with procedures similar to those used for the thumb. Typically, the additional digit is radially deviated and angulated, eventually leading to impingement of thumb pinch and the first web space. Ray amputation is also an option if no reconstructive surgery will produce the stable, sensate radial pinch that is essential to hand function.32

Ring-finger polydactyly and long-finger polydactyly are often complicated by some element of syndactyly, resulting in a relative paucity of skin (Figure 14). There is failure of both formation (hypoplasia) and differentiation (syndactyly). The hypoplasia particularly affects the function of these digits by tethering them; multiple surgeries to restore proper hand function are the norm.1 Reconstructive surgery for these digits requires preoperative tissue inventory followed by resection and augmentation; as in syndactyly, skin for coverage is at a premium. Creation of a 3-fingered hand is an option.23

Temtamy and McKusick10 type A little-finger polydactyly is treated similarly to the thumb, with the caveat that hypothenar and intrinsic muscles that insert on the resected little finger are transferred to the remaining digit. In contrast to thumb polydactyly, the extrinsic musculature tends to be in good position. Suture ligation of type B polydactyly, as described by Flatt, is likely more common than orthopedists appreciate, as pediatricians and neonatal unit practitioners commonly perform this procedure in the nursery.1-3 It has been described with 2-0 Vicryl3 (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) and 4-0 silk sutures,32 with the goal of necrosis and autoamputation. Parents should be told the finger generally falls off about 10 days (range, 4-21 days) after ligation.3 Multiple authors have cited a report of exsanguination from suture ligation, but we could not locate the primary source. It is advisable to wait until a patient is 6 months of age if planning to resect the nubbin in the operating room, given the anesthesia risk and the lack of functional impairment. Katz and Linder33 indicated they remove type B polydactyly in the nursery suite used for circumcisions; they use anesthetizing cream on the skin, and sharp excision with a scalpel, followed by direct pressure and Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) application. Suture ligation is recommended only if there is a narrow, thin (<2 mm) soft-tissue stalk; any broad or bony stalk necessitates surgical removal to avoid neuroma formation and failure of autonecrosis (Figure 15).27 Other options are a single swipe of a scalpel and elliptical excision; sharp transaction of the digital nerve with subsequent retraction is advised to avoid neuroma formation.2

Barton described ulnar dimelia operations as “spare parts surgery.”1 Extra digits are ablated and a thumb created (Figure 16). The hand might have a digit in relatively good rotational position for thumbplasty, or the principles of pollicization may need to be used. If the patient is already using the hand, the surgeon should note which finger the patient uses as a thumb.24 Any accompanying wrist flexion contracture must be corrected with careful attention to musculotendinous balancing. Because the forearm and elbow, and occasionally even the more proximal limb, will be abnormal in this disorder, multiple surgeries are again the norm.1

Pentadactyly is treated like thumb hypoplasia, with first web space creation.1

Complications

In polydactyly, a reoperation rate of up to 25% has been reported, with most reoperations performed because of residual or subsequent deformity.5,30,31,38 Risk factors for reoperation are type IV thumb duplication, preoperative “zigzag” deformity, and radially deviated thumb elements at presentation.5 The delta phalanx may not show on radiographs until the patient is 18 months old, but functional deformity will worsen as long as it is present. Zigzag deformity may be due to the delta phalanx or to musculotendinous imbalance, such as a radially inserted flexor pollicis longus (FPL) or lack of stable MCP abduction. Miura31 found that careful reconstruction of the joint capsule and thenar muscles from the ablated digit to the remnant digit is the key to a successful initial surgery. Lee and colleagues39 defined zigzag deformity as more than 20° MCP and IP angulation; for cases present before surgery, they recommended FPL relocation by the pullout technique in addition to osteotomies to prevent further interphalangeal deviation (Figures 17, 18).

Abnormal physeal growth, joint instability, and stiffness can all occur. Stiffness is particularly difficult to treat but seldom presents a functional problem. Joint enlargement, which is not uncommon, results from either broad articular surfaces or retained cartilage from the perichondral ring after resection that later ossifies.5,38 Nubbin-type duplications may not fall off after suture ligation, necessitating further excision, and a cosmetic bump is seen after 40% of suture ligations.3 Patillo and Rayan28 and Rayan and Frey29 warned against suture ligation unless the nubbin has a small stalk because of the possibility of infection and gangrene. The excised nubbin tissue is histologically nervous, and there have been reports of painful neuromas in the remaining scar of a ligated nubbin that respond well to excision.26,27,40 It is thought that these painful lesions form because the ligature prevents the digital nerves to the vestigial digit from retracting.27 Nail deformity and IP joint stiffness are seen with the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure, though often finger function remains satisfactory.

Conclusion

Polydactyly is a common congenital hand abnormality. Its true incidence is unknown because of inconsistent documentation. Surgeons must strive for a functional, cosmetic hand, given a diverse set of possible anomalies. Hypoplasia is the rule; tissue should be ablated and augmented as necessary. Musculotendinous insertions may need to be centralized. Patients’ family members should always be counseled that more surgery may be needed in the future, as further deformity can occur with growth. Surgically corrected thumb duplications will be stiffer, shorter, and thinner than their normal counterparts. Nail ridges are common. However, it should be noted that 88% of these patients are satisfied with their results.41 Some amount of contracture and abnormal function should be expected with index-, long-, and ring-finger duplications. The only remnant of type B postaxial duplications may be a slight discoloration or bump, though stiffness and deformity can happen with a type A deformity. A “duplicated” digit that requires surgical correction will never be completely normal, but acceptable function is routinely achievable.

Polydactyly is the presence of extra digits. Its incidence is likely underestimated because many practitioners treat simple “nubbins” without referring them to orthopedic specialists.1-3 Polydactyly can be detected by ultrasound as early as 14 weeks’ gestational age, with partial autoamputation seen in most isolated polydactylies.4 The thumb, responsible for 40% of hand function, must be able to oppose the other digits with a stable pinch.5 Polydactyly encumbers this motion when the duplicated digits deviate from normal alignment. Ezaki6 noted that the anatomy is better described as “split” than “duplicated.” There are many dichotomous ways to classify polydactyly: preaxial (radial) versus postaxial (ulnar), thumb versus triphalangeal, simple versus complex (Figure 1). Mixed polydactyly is defined as the presence of preaxial and postaxial polydactyly.7 Surgical management seeks to allow normal hand function and to restore cosmesis.

Epidemiology

Sun and colleagues8 reported the overall polydactyly incidence as 2 per 1000 live births in China from 1998 to 2009, with a slight male predominance; polydactyly was also 3 times more common than syndactyly in this population. Ivy,9 in a 5-year audit of Pennsylvania Department of Health records, found polydactyly to be the fourth most common congenital anomaly after clubfoot, cleft lip/palate, and spina bifida. Thumb duplication occurs in 0.08 to 1.4 per 1000 live births and is more common in American Indians and Asians than in other races.5,10 It occurs in a male-to-female ratio of 2.5 to 1 and is most often unilateral.5 Postaxial polydactyly is predominant in black infants; it is most often inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, if isolated, or in an autosomal recessive pattern, if syndromic.1 A prospective San Diego study of 11,161 newborns found postaxial type B polydactyly in 1 per 531 live births (1 per 143 black infants, 1 per 1339 white infants); 76% of cases were bilateral, and 86% had a positive family history.3 In patients of non-African descent, it is associated with anomalies in other organs. Central duplication is rare and often autosomal dominant.5,10

Genetics and Development

As early as 1896, the heritability of polydactyly was noted.11 As of 2010, polydactyly has been associated with 310 diseases.12 Ninety-nine genes, most involved in regulation of anterior-posterior formation of the limb bud, have been implicated.12,13

The upper limb begins to form at day 26 in utero.14 Apoptosis in the interdigital necrotic zones results in the formation of individual digits. It is presumed that, in polydactyly, the involved tissue is hypoplastic because of an abnormal interaction between mesoderm and ectoderm.5 Presence of an apical ectodermal ridge determines the formation of a limb bud, and on it the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) dictates preaxial and postaxial alignment.14,15 The ZPA is located on the posterior zone of the developing limb bud. The levels of GLI3, a zinc finger-containing DNA-binding protein, are highest in the anterior area, and HAND2, a basic helix-loop-helix DNA-binding protein, is found in the ZPA. This polarity promotes sonic hedgehog (Shh) gene expression in the posterior region, which in turn prevents GLI3 cleavage into its repressed form. GLI3R (repressed) and GLI3A (active) concentrations are highest, therefore, in the anterior and posterior portions of the bud, respectively. The GLI3A:GLI3R ratio is responsible for the identity and number of digits in the hand (ie, the thumb develops in regions of high GLI3R). GLI and Shh mutations lead to polydactylous hands with absent thumbs (Figure 2).16

Ciliopathies have also been shown to cause postaxial polydactyly, possibly because of the role that nonmotile cilia play in hedgehog signaling.17 Mutations in Shh genomic regulators cause preaxial polydactyly.18 HoxD activates Shh in the ZPA; HoxD13 mutations are associated with synpolydactyly.16,19 In each of these mutations, Shh production is altered, and some form of polydactyly results.

Associations

Many syndromes have been associated with polydactyly. Not all polydactyly is associated with other disorders, but the more complex the polydactyly, the more likely that other anomalies are present. Every patient who presents with polydactyly should have a full history taken and a physical examination performed (Figure 3). Any patient with syndromic findings or atypical presentations (eg, triphalangism, postaxial polydactyly in a patient of non-African descent, central and index polydactyly) should be referred to a geneticist.

Classifications

The Wassel20 classification describes the anatomical presentation of thumb duplication on the basis of 70 cases in Iowa (Figures 4, 5; Table 1). Because some duplications fall outside the Wassel classification, many researchers have proposed modifications (Figure 6).21-25

The Temtamy and McKusick10 classification, which is the product of geneticists, classifies duplications by grouping genetically related presentations (Table 2). It provides the most commonly used postaxial classification, with type A being a fully developed digit and type B a rudimentary and pedunculated digit, informally referred to as a nubbin. Type B is more common than type A. Given inheritance patterns, it is assumed that type A is likely multifactorial and type B autosomal dominant.10 Thumb polydactyly inheritance is still unclear. The other types of preaxial polydactyly and high degrees of polydactyly are rare but seem to be passed on in an autosomal dominant fashion on pedigree analysis.10

The Stelling and Turek classification presents the duplication from a tissue perspective: Type I duplication is a rudimentary mass devoid of other tissue elements; type II is a subtotal duplication with some normal structures; and type III is a duplication of the entire “osteoarticular column,” including the metacarpal.1 It is interesting to note that histology of type I duplications shows neuroma-like tissue.26-28 Again, normal is a relative term because, in polydactyly, the duplications are hypoplastic and deviated, with anomalous anatomy.

The Rayan classification describes ulnar polydactyly and was derived from a case study series of 148 patients in Oklahoma (Table 3).29

There are also some complex polydactylies that are not easily classified: ulnar dimelia, cleft hand, pentadactyly, and hyperphalangism. Ulnar dimelia, also known as “mirror hand,” is typically 7 digits with no thumb, but other variations are seen. The radius is often absent, and the elbow is abnormal. There is some debate about whether it is a fusion of 2 hands. Pentadactyly, or the 5-fingered hand, appears as 5 triphalangeal digits with no thumb (Figure 7).

Isolated thumb triphalangism might appear similar to pentadactyly. Miura30,31 pointed out that the radial digit in the pentadactylous hand may be opposable (thumb-like) or nonopposable; in his studies, the patients with the opposable thumb had a metacarpal with a proximal epiphysis (Figure 8). Consequently, the triphalangeal thumb metacarpal with a distal epiphysis is true pentadactyly, whereas that with a proximal epiphysis is hyperphalangism (Figure 9). Treatment of these complex polydactylies involves the same underlying principles as for preaxial and postaxial polydactyly, albeit with additional proximal upper extremity considerations.

When to Operate (Timing)

Ezaki6 recommended surgical intervention at age 6 to 9 months, before fine motor skills have developed with the abnormal anatomy. Cortical learning occurs as the child begins prehensile activities before 6 months, but the risks of anesthesia outweigh functional benefits until the child is older. Waiting until 1 year of age is not uncommon, though surgery at an earlier age may be beneficial if the polydactyly affects hand function.32 It is not uncommon to wait with the more balanced thumb polydactylies to assess thumb function. Hypoplasia might also delay surgical intervention until there is enough tissue inventory for reconstruction. Wassel20 noted that surgical intervention ideally occurs before the supernumerary elements displace the normal elements, as tends to happen with growth. Suture ligation is an option in the neonatal unit for some pedunculated digits.33 Studies have shown satisfactory results in adults treated for polydactyly, if the patient presents later than expected.34

Surgical Considerations

Knavel recommended simple excision, stating that “ablation requires no ingenuity and creates no problems.”5 This belief, though true for some duplications, will not lead to the best outcome for more complex polydactylies. The goal of surgery is a stable and well-aligned thumb for pinch and prehensile activity, as well as a cosmetically pleasing hand. Incisions should not be made linearly along the axis of the digit, as the scar will cause deviation with growth.24

Wassel type I polydactyly might appear incidentally as a broad thumb, in which case it requires no intervention (Figure 10). However, in Wassel types I and II polydactyly with deformity, the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure is useful for both bifid and duplicated phalanges (Figure 11).5,6,30,32,35 Collateral ligaments may need to be released in type II because of difficulty in opposing the tissue. Cosmetic results with Bilhaut-Cloquet are unpredictable. The original technique required symmetrically sized digits; results today have been improved with microtechniques and preservation of an entire nail.36 Another option is ablation of the more hypoplastic osseous element and soft-tissue augmentation of the residual digit. The theme of ablation and augmentation is seen throughout the literature for the surgical treatment of polydactyly (Figure 12).1

For type III polydactyly, the bifid proximal phalanx is narrowed by resection and realigned with osteotomy of the remaining diaphysis. Type IV polydactyly, the most common thumb duplication, often requires advancement of the abductor pollicis brevis to the base of the proximal phalanx to aid in metacarpophalangeal (MCP) stabilization, abduction, and opposition. The metacarpal head, if broad and with 2 facets, can be shaped to form a single articulating surface. The metacarpal, occasionally with the proximal phalanx, often requires realignment by closing wedge osteotomy. Last, tendons on the resected bony elements should be rebalanced on the remaining digit, and anomalous slips must be released. For instance, given a radial insertion of the long flexor tendon on the distal phalanx, the tendon should be moved centrally. A strong flexor or extensor tendon on the amputated digit should be transferred to the remaining digit.24

Types V and VI are treated similarly to type IV, with the addition of a first web space Z-plasty or web widening if there is thenar eminence contracture. Acral transposition has also been described, with transposition of the tip of the ablated digit in place of the tip of the kept digit; this technique is ideal if one digit has a more normal proximal part while the other has a more normal distal part (Figure 13).35

Type VII thumb polydactyly, the type most likely inherited and associated with other disorders, should be treated like type VI. The nail should be preserved; amputation of the distal phalanx is not advised. Resection of the delta phalanx or 1 interphalangeal (IP) joint is an option. Articular surfaces will remodel if done before the age of 1 year. If the thenar eminence is hypoplastic, then Huber transfer of the abductor digiti minimi should be considered.37 Resection of the triphalangeal thumb is also advised, even if the biphalangeal thumb is more hypoplastic, with transfer of the ligaments and tendons, as described earlier.5,6,24,30,32,35

Thumb triphalangism, if isolated, and hyperphalangism in the other digits, can be treated with resection of the delta phalanx or one of the IP joints if it is affecting function or cosmesis.1,6 Wood and Flatt23 recommended early resection of a thumb delta phalanx because of the likelihood of deviation that impedes thumb function. For children, they recommended delta phalanx resection and Kirschner wire fixation for 6 weeks; for adults, they recommended resection or fusion of the joint, with osteotomy as needed for deviation.23,24 For thumb triphalangism, multiple surgeries are the norm, as Wood24 reported in his study of 21 patients who underwent 78 operations in total.

Index polydactyly may present as a simple pedunculated skin tag, which can be simply excised, or as a more complex musculoskeletal duplication. More complex presentations can be treated with procedures similar to those used for the thumb. Typically, the additional digit is radially deviated and angulated, eventually leading to impingement of thumb pinch and the first web space. Ray amputation is also an option if no reconstructive surgery will produce the stable, sensate radial pinch that is essential to hand function.32

Ring-finger polydactyly and long-finger polydactyly are often complicated by some element of syndactyly, resulting in a relative paucity of skin (Figure 14). There is failure of both formation (hypoplasia) and differentiation (syndactyly). The hypoplasia particularly affects the function of these digits by tethering them; multiple surgeries to restore proper hand function are the norm.1 Reconstructive surgery for these digits requires preoperative tissue inventory followed by resection and augmentation; as in syndactyly, skin for coverage is at a premium. Creation of a 3-fingered hand is an option.23

Temtamy and McKusick10 type A little-finger polydactyly is treated similarly to the thumb, with the caveat that hypothenar and intrinsic muscles that insert on the resected little finger are transferred to the remaining digit. In contrast to thumb polydactyly, the extrinsic musculature tends to be in good position. Suture ligation of type B polydactyly, as described by Flatt, is likely more common than orthopedists appreciate, as pediatricians and neonatal unit practitioners commonly perform this procedure in the nursery.1-3 It has been described with 2-0 Vicryl3 (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) and 4-0 silk sutures,32 with the goal of necrosis and autoamputation. Parents should be told the finger generally falls off about 10 days (range, 4-21 days) after ligation.3 Multiple authors have cited a report of exsanguination from suture ligation, but we could not locate the primary source. It is advisable to wait until a patient is 6 months of age if planning to resect the nubbin in the operating room, given the anesthesia risk and the lack of functional impairment. Katz and Linder33 indicated they remove type B polydactyly in the nursery suite used for circumcisions; they use anesthetizing cream on the skin, and sharp excision with a scalpel, followed by direct pressure and Steri-Strip (3M, St. Paul, Minnesota) application. Suture ligation is recommended only if there is a narrow, thin (<2 mm) soft-tissue stalk; any broad or bony stalk necessitates surgical removal to avoid neuroma formation and failure of autonecrosis (Figure 15).27 Other options are a single swipe of a scalpel and elliptical excision; sharp transaction of the digital nerve with subsequent retraction is advised to avoid neuroma formation.2

Barton described ulnar dimelia operations as “spare parts surgery.”1 Extra digits are ablated and a thumb created (Figure 16). The hand might have a digit in relatively good rotational position for thumbplasty, or the principles of pollicization may need to be used. If the patient is already using the hand, the surgeon should note which finger the patient uses as a thumb.24 Any accompanying wrist flexion contracture must be corrected with careful attention to musculotendinous balancing. Because the forearm and elbow, and occasionally even the more proximal limb, will be abnormal in this disorder, multiple surgeries are again the norm.1

Pentadactyly is treated like thumb hypoplasia, with first web space creation.1

Complications

In polydactyly, a reoperation rate of up to 25% has been reported, with most reoperations performed because of residual or subsequent deformity.5,30,31,38 Risk factors for reoperation are type IV thumb duplication, preoperative “zigzag” deformity, and radially deviated thumb elements at presentation.5 The delta phalanx may not show on radiographs until the patient is 18 months old, but functional deformity will worsen as long as it is present. Zigzag deformity may be due to the delta phalanx or to musculotendinous imbalance, such as a radially inserted flexor pollicis longus (FPL) or lack of stable MCP abduction. Miura31 found that careful reconstruction of the joint capsule and thenar muscles from the ablated digit to the remnant digit is the key to a successful initial surgery. Lee and colleagues39 defined zigzag deformity as more than 20° MCP and IP angulation; for cases present before surgery, they recommended FPL relocation by the pullout technique in addition to osteotomies to prevent further interphalangeal deviation (Figures 17, 18).

Abnormal physeal growth, joint instability, and stiffness can all occur. Stiffness is particularly difficult to treat but seldom presents a functional problem. Joint enlargement, which is not uncommon, results from either broad articular surfaces or retained cartilage from the perichondral ring after resection that later ossifies.5,38 Nubbin-type duplications may not fall off after suture ligation, necessitating further excision, and a cosmetic bump is seen after 40% of suture ligations.3 Patillo and Rayan28 and Rayan and Frey29 warned against suture ligation unless the nubbin has a small stalk because of the possibility of infection and gangrene. The excised nubbin tissue is histologically nervous, and there have been reports of painful neuromas in the remaining scar of a ligated nubbin that respond well to excision.26,27,40 It is thought that these painful lesions form because the ligature prevents the digital nerves to the vestigial digit from retracting.27 Nail deformity and IP joint stiffness are seen with the Bilhaut-Cloquet procedure, though often finger function remains satisfactory.

Conclusion

Polydactyly is a common congenital hand abnormality. Its true incidence is unknown because of inconsistent documentation. Surgeons must strive for a functional, cosmetic hand, given a diverse set of possible anomalies. Hypoplasia is the rule; tissue should be ablated and augmented as necessary. Musculotendinous insertions may need to be centralized. Patients’ family members should always be counseled that more surgery may be needed in the future, as further deformity can occur with growth. Surgically corrected thumb duplications will be stiffer, shorter, and thinner than their normal counterparts. Nail ridges are common. However, it should be noted that 88% of these patients are satisfied with their results.41 Some amount of contracture and abnormal function should be expected with index-, long-, and ring-finger duplications. The only remnant of type B postaxial duplications may be a slight discoloration or bump, though stiffness and deformity can happen with a type A deformity. A “duplicated” digit that requires surgical correction will never be completely normal, but acceptable function is routinely achievable.

1. Graham TJ, Ress AM. Finger polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):49-64.

2. Abzug JM, Kozin SH. Treatment of postaxial polydactyly type B. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1223-1225.

3. Watson BT, Hennrikus WL. Postaxial type-B polydactyly—prevalence and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(1):65-68.

4. Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Fetal polydactyly diagnosis during early pregnancy: clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):755-758.

5. Cohen MS. Thumb duplication. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):17-27.

6. Ezaki M. Radial polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):577-588.

7. Nathan PA, Keniston RC. Crossed polydactyly: case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(6):847-849.

8. Sun G, Xu ZM, Liang JF, Li L, Tang DX. Twelve-year prevalence of common neonatal congenital malformations in Zhejiang Province, China. World J Pediatr. 2011;7(4):331-336.

9. Ivy RH. Congenital anomalies as recorded on birth certificates in the Division of Vital Statistics of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, for the period of 1951–1955, inclusive. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1957;20(5):400-411.

10. Temtamy SA, McKusick VA. Polydactyly as a part of syndromes. In: Bergsma D, ed. Mudge JR, Paul NW, Conde Greene S, associate eds. The Genetics of Hand Malformations. New York, NY: Liss. Birth Defects Original Article Series. 1978;14(3):364-439.

11. Gould W, Pyle L. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. New York, NY: Bell; 1896.

12. Biesecker LG. Polydactyly: how many disorders and how many genes: 2010 update. Dev Dyn. 2011;250(5):931-942.

13. Grzeschik K. Human limb malformations; an approach to the molecular basis of development. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;46(7):983-991.

14. Zaleske DJ. Development of the upper limb. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):383-390.

15. Beatty E. Upper limb tissue differentiation in the human embryo. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):391-404.

16. Anderson E, Peluso S, Lettice LA, Hill RE. Human limb abnormalities caused by disruption of hedgehog signaling. Trends Genet. 2012;28(8):364-373.

17. Ware SM, Aygun MG, Heldebrandt F. Spectrum of clinical diseases caused by disorders of primary cilia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(5):444-450.

18. Lettice LA, Hill RE. Preaxial polydactyly: a model for defective long-range regulation in congenital abnormalities. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(3):294-300.

19. Al-Qattan MA. Type II familial synpolydactyly: report on two families with an emphasis on variations of expression. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(1):112-114.

20. Wassel HD. The results of surgery for polydactyly of the thumb. Clin Orthop. 1969;(64):175-193.

21. Blauth W, Olason AT. Classification of polydactyly of the hands and feet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(6):334-344.

22. Wood VE. Super digit. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):673-684.

23. Wood VE, Flatt AE. Congenital triangular bones in the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(3):179-193.

24. Wood VE. Polydactyly and the triphalangeal thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(5):436-444.

25. Zuidam JM, Selles RW, Ananta M, Runia J, Hovius SER. A classification system of radial polydactyly: inclusion of triphalangeal thumb and triplication. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(3):373-377.

26. Leber GE, Gosain AK. Surgical excision of pedunculated supernumerary digits prevents traumatic amputation neuromas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(2):108-112.

27. Mullick S, Borschel GH. A selective approach to treatment of ulnar polydactyly: preventing painful neuroma and incomplete excision. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;27(1):39-42.

28. Patillo D, Rayan GM. Complications of suture ligation ablation for ulnar polydactyly: a report of two cases. Hand (N Y). 2011;6(1):102-105.

29. Rayan GM, Frey B. Ulnar polydactyly. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1449-1454.

30. Miura T. Triphalangeal thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(5):587-594.

31. Miura T. Duplicated thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3):470-481.

32. Simmons BP. Polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):545-566.

33. Katz K, Linder N. Postaxial type B polydactyly treated by excision in the neonatal nursery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(4):448-449.

34. Manohar A, Beard AJ. Outcome of reconstruction for duplication of the thumb in adults aged over 40. Hand Surg. 2011;16(2):207-210.

35. Watt AJ, Chung KC. Duplication. Hand Clin. 2009;25(2):215-228.

36. Tonkin MA. Thumb duplication: concepts and techniques. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(1):1-17.

37. Huber E. Relief operation in the case of paralysis of the median nerve. J Hand Surg Eur. 2004;29(1):35-37.

38. Mih AD. Complications of duplicate thumb reconstruction. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):143-149.

39. Lee CC, Park HY, Yoon JO, Lee KW. Correction of Wassel type IV thumb duplication with zigzag deformity: results of a new method of flexor pollicis longus tendon relocation. J Hand Surg Eur. 2013;38(3):272-280.

40. Hare PJ. Rudimentary polydactyly. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66(11):402-408.

41. Yen CH, Chan WL, Leung HB, Mak KH. Thumb polydactyly: clinical outcome after reconstruction. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2006;14(3):295-302.

42. Edmunds JO. A tribute to Daniel C. Riordan, MD (1917–2012). Tulane University School of Medicine, Department of Orthopaedics website. http://tulane.edu/som/departments/orthopaedics/news-and-events/danriordantribute.cfm. Accessed March 31, 2015.

43. Faust DC, Herms R. Daniel C. Riordan, MD, 1917–2012. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(1):202-205.

1. Graham TJ, Ress AM. Finger polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):49-64.

2. Abzug JM, Kozin SH. Treatment of postaxial polydactyly type B. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1223-1225.

3. Watson BT, Hennrikus WL. Postaxial type-B polydactyly—prevalence and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(1):65-68.

4. Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Fetal polydactyly diagnosis during early pregnancy: clinical applications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(3):755-758.

5. Cohen MS. Thumb duplication. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):17-27.

6. Ezaki M. Radial polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):577-588.

7. Nathan PA, Keniston RC. Crossed polydactyly: case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(6):847-849.

8. Sun G, Xu ZM, Liang JF, Li L, Tang DX. Twelve-year prevalence of common neonatal congenital malformations in Zhejiang Province, China. World J Pediatr. 2011;7(4):331-336.

9. Ivy RH. Congenital anomalies as recorded on birth certificates in the Division of Vital Statistics of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, for the period of 1951–1955, inclusive. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1957;20(5):400-411.

10. Temtamy SA, McKusick VA. Polydactyly as a part of syndromes. In: Bergsma D, ed. Mudge JR, Paul NW, Conde Greene S, associate eds. The Genetics of Hand Malformations. New York, NY: Liss. Birth Defects Original Article Series. 1978;14(3):364-439.

11. Gould W, Pyle L. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. New York, NY: Bell; 1896.

12. Biesecker LG. Polydactyly: how many disorders and how many genes: 2010 update. Dev Dyn. 2011;250(5):931-942.

13. Grzeschik K. Human limb malformations; an approach to the molecular basis of development. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;46(7):983-991.

14. Zaleske DJ. Development of the upper limb. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):383-390.

15. Beatty E. Upper limb tissue differentiation in the human embryo. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):391-404.

16. Anderson E, Peluso S, Lettice LA, Hill RE. Human limb abnormalities caused by disruption of hedgehog signaling. Trends Genet. 2012;28(8):364-373.

17. Ware SM, Aygun MG, Heldebrandt F. Spectrum of clinical diseases caused by disorders of primary cilia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(5):444-450.

18. Lettice LA, Hill RE. Preaxial polydactyly: a model for defective long-range regulation in congenital abnormalities. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15(3):294-300.

19. Al-Qattan MA. Type II familial synpolydactyly: report on two families with an emphasis on variations of expression. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(1):112-114.

20. Wassel HD. The results of surgery for polydactyly of the thumb. Clin Orthop. 1969;(64):175-193.

21. Blauth W, Olason AT. Classification of polydactyly of the hands and feet. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107(6):334-344.

22. Wood VE. Super digit. Hand Clin. 1990;6(4):673-684.

23. Wood VE, Flatt AE. Congenital triangular bones in the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1977;2(3):179-193.

24. Wood VE. Polydactyly and the triphalangeal thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(5):436-444.

25. Zuidam JM, Selles RW, Ananta M, Runia J, Hovius SER. A classification system of radial polydactyly: inclusion of triphalangeal thumb and triplication. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(3):373-377.

26. Leber GE, Gosain AK. Surgical excision of pedunculated supernumerary digits prevents traumatic amputation neuromas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(2):108-112.

27. Mullick S, Borschel GH. A selective approach to treatment of ulnar polydactyly: preventing painful neuroma and incomplete excision. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;27(1):39-42.

28. Patillo D, Rayan GM. Complications of suture ligation ablation for ulnar polydactyly: a report of two cases. Hand (N Y). 2011;6(1):102-105.

29. Rayan GM, Frey B. Ulnar polydactyly. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1449-1454.

30. Miura T. Triphalangeal thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1976;58(5):587-594.

31. Miura T. Duplicated thumb. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3):470-481.

32. Simmons BP. Polydactyly. Hand Clin. 1985;1(3):545-566.

33. Katz K, Linder N. Postaxial type B polydactyly treated by excision in the neonatal nursery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(4):448-449.

34. Manohar A, Beard AJ. Outcome of reconstruction for duplication of the thumb in adults aged over 40. Hand Surg. 2011;16(2):207-210.

35. Watt AJ, Chung KC. Duplication. Hand Clin. 2009;25(2):215-228.

36. Tonkin MA. Thumb duplication: concepts and techniques. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(1):1-17.

37. Huber E. Relief operation in the case of paralysis of the median nerve. J Hand Surg Eur. 2004;29(1):35-37.

38. Mih AD. Complications of duplicate thumb reconstruction. Hand Clin. 1998;14(1):143-149.

39. Lee CC, Park HY, Yoon JO, Lee KW. Correction of Wassel type IV thumb duplication with zigzag deformity: results of a new method of flexor pollicis longus tendon relocation. J Hand Surg Eur. 2013;38(3):272-280.

40. Hare PJ. Rudimentary polydactyly. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66(11):402-408.

41. Yen CH, Chan WL, Leung HB, Mak KH. Thumb polydactyly: clinical outcome after reconstruction. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2006;14(3):295-302.

42. Edmunds JO. A tribute to Daniel C. Riordan, MD (1917–2012). Tulane University School of Medicine, Department of Orthopaedics website. http://tulane.edu/som/departments/orthopaedics/news-and-events/danriordantribute.cfm. Accessed March 31, 2015.

43. Faust DC, Herms R. Daniel C. Riordan, MD, 1917–2012. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(1):202-205.

Nontraumatic Knee Pain: A Diagnostic & Treatment Guide

Jane, age 42, presents with right knee pain that she’s had for about six months. She denies any trauma. Jane describes the pain as “vague and poorly localized” but worse with activity. She says she started a walking/running program nine months ago, when she was told she was overweight (BMI, 29). She has lost 10 pounds since then and hopes to lose more by continuing to exercise. Further review reveals that Jane has experienced increasing pain while ascending and descending stairs and that the pain is also exacerbated when she stands after prolonged sitting.

If Jane were your patient, what would you include in a physical examination, and how would you diagnose and treat her?

Knee pain is a common presentation in primary care. While traumatic knee pain is frequently addressed in the medical literature, little has been written about chronic nontraumatic nonarthritic knee pain such as Jane’s. Thus, while physical exam tests often lead to the correct diagnosis for traumatic knee pain, there is limited information on the use of such tests to determine the etiology of chronic knee pain.

This review was developed to fill that gap. The pages that follow contain general guidance on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic nontraumatic knee pain. The conditions are presented anatomically—anterior, lateral, medial, or posterior—with common etiologies, history and physical exam findings, and diagnosis and treatment options for each (see Table, page 28).1-31

ANTERIOR KNEE PAIN

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS)

The most common cause of anterior knee pain, PFPS is a complex entity with an etiology that has not been well described.2 The quadriceps tendon, medial and lateral retinacula, iliotibial band (ITB), vastus medialis and lateralis, and the insertion of the patellar tendon on the anterior tibial tubercle all play a role in proper tracking of the patellofemoral joint; an imbalance in any of these forces leads to abnormal patellar tracking over the femoral condyles, and pain ensues. PFPS can also be secondary to joint overload, in which excessive physical activity (eg, running, lunges, or squats) overloads the patellofemoral joint and causes pain.

Risk factors for PFPS include strength imbalances in the quadriceps, hamstring, and hip muscle groups, and increased training, such as running longer distances.4,32 A recent review showed no relationship between an increased quadriceps (Q)-angle and PFPS, so that is no longer considered a major risk factor.5

Diagnosis. PFPS is a diagnosis of exclusion and is primarily based on history and physical exam. Anterior knee pain that is exacerbated when seated for long periods of time (the “theater sign”) or by descending stairs is a classic indication of PFPS.1 Patients may complain of knee stiffness or “giving out” secondary to sharp knee pain and a sensation of popping or crepitus in the joint. Swelling is not a common finding.2

A recent meta-analysis revealed limited evidence for the use of any specific physical exam tests to diagnose PFPS. But pain during squatting and pain with a patellar tilt test were most consistent with a diagnosis of PFPS. (The patellar tilt test involves lifting the lateral edge of the patella superiorly while the patient lies supine with knee extended; pain with < 20° of lift suggests a tight lateral retinaculum). Conversely, the absence of pain during squatting or the absence of lateral retinacular pain helps rule it out.2 A physical exam of the cruciate and collateral ligaments should be performed in a patient with a history of instability. Radiography is not needed for a diagnosis but may be considered if examination reveals an effusion, the patient is 50 or older, or no improvement occurs after eight to 12 weeks of treatment.33

Treatment. The most effective and strongly supported treatment for PFPS is a six-week physiotherapy program focusing on strengthening the quadriceps and hip muscles and stretching the quadriceps, ITB, hamstrings, and hip flexors.4,5 There is limited information about the use of NSAIDs, but they can be considered for short-term management.2

Patellar taping and bracing have shown some promise as adjunct therapies for PFPS, although the data for both are nonconclusive. There is a paucity of prospective randomized trials of patellar bracing, and a 2012 Cochrane review found limited evidence of its efficacy.34 But a 2014 meta-analysis revealed moderate evidence in support of patellar taping early on to help decrease pain,6 and a recent review suggests that it can be helpful in both the short and long term.7