User login

Caring for women with pelvic floor disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: Expert guidance

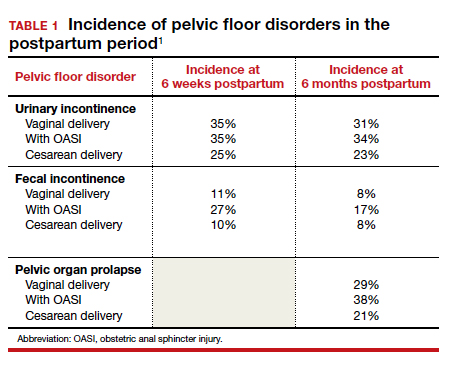

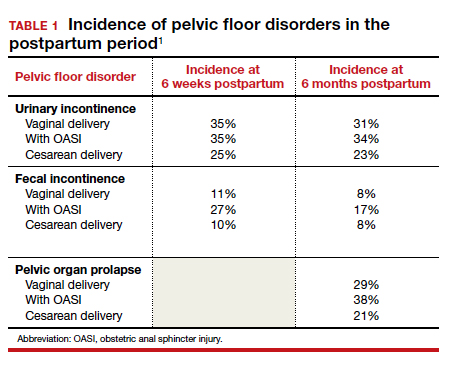

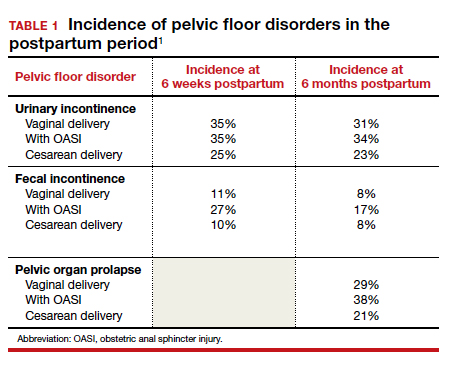

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) affect many pregnant and newly postpartum women. These conditions, including urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be overshadowed by common pregnancy and postpartum concerns (TABLE 1).1 With the use of a few quick screening questions, however, PFDs easily can be identified in this at-risk population. Active management need not be delayed until after delivery for women experiencing bother, as options exist for women with PFDs during pregnancy as well as postpartum.

In this article, we discuss the common PFDs that obstetric clinicians face in the context of case scenarios and review how you can be better equipped to care for affected individuals.

CASE 1 Screening

A 30-year-old woman (G1P1) presents for her routine postpartum visit after an operative vaginal delivery with a second-degree laceration.

How would you screen this patient for PFDs?

Why screening for PFDs matters

While there are no validated PFD screening tools for this patient population, clinicians can ask a series of brief open-ended questions as part of the review of systems to efficiently evaluate for the common PFDs in peripartum patients (see “Screening questions to evaluate patients for peripartum pelvic floor disorders” below).

Pelvic floor disorders in the peripartum period can have a significant negative impact. In pregnancy, nearly half of women report psychological strain due to the presence of bowel, bladder, prolapse, or sexual dysfunction symptoms.2 Postpartum, PFDs have negative effects on overall health, well-being, and self-esteem, with significantly increased rates of postpartum depression in women who experience urinary incontinence.3,4 Proactively inquiring about PFD symptoms, providing anticipatory guidance, and recommending treatment options can positively impact a patient in multiple domains.

Sometimes during pregnancy or after having a baby, a woman experiences pelvic floor symptoms. Do you have any of the following?

- leakage with coughing, laughing, sneezing, or physical activity

- urgency to urinate or leakage due to urgency

- bulging or pressure within the vagina

- pain with intercourse

- accidental bowel leakage of stool or flatus

CASE 2 Stress urinary incontinence

A 27-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 2 months following spontaneous vaginal delivery with symptoms of urine leakage with laughing and running. Her urinary incontinence has been improving since delivery, but it continues to be bothersome.

What would you recommend for this patient?

Conservative SUI management strategies in pregnancy

Urinary tract symptoms are common in pregnancy, with up to 41.8% of women reporting urinary symptom distress in the third trimester.5 During pregnancy, estrogen and progesterone decrease urethral pressure that, together with increased intra-abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus, can cause or worsen stress urinary incontinence (SUI).6

During pregnancy, women should be offered conservative therapies for SUI. For women who can perform a pelvic floor contraction (a Kegel exercise), self-guided pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs) may be helpful (see “Pelvic floor muscle exercises” below). We recommend that women start with 1 to 2 sets of 10 Kegel exercises per day and that they hold the squeeze for 2 to 3 seconds, working up to holding for 10 seconds. The goal is to strengthen and improve muscle control so that the Kegel squeeze can be paired with activities that cause SUI.

For women who are unable to perform a Kegel exercise or are not improving with a home PFME regimen, referral to pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be considered. While data support the efficacy of PFPT for SUI treatment in nonpregnant women,7 data are lacking on PFME in pregnancy.

In women without urinary incontinence, PFME in early pregnancy can prevent the onset of incontinence in late pregnancy and the postpartum period.8 By contrast, the same 2020 Cochrane Review found no evidence that antenatal pelvic floor muscle therapy in incontinent women decreases incontinence in mid- or late-pregnancy or in the postpartum period.8 As the quality of this evidence is very low and there is no evidence of harm with PFME, we continue to recommend it for women with bothersome SUI.

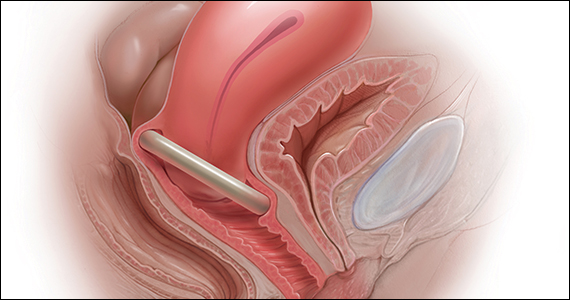

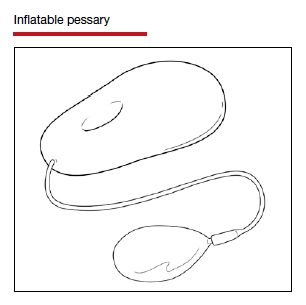

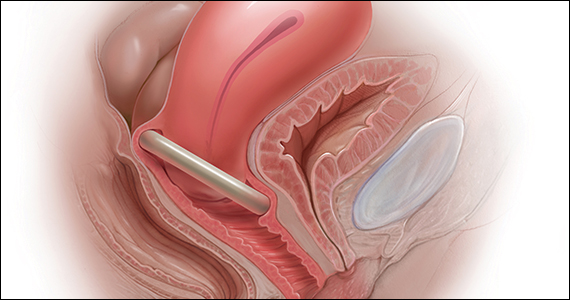

Incontinence pessaries or vaginal inserts (such as Poise Impressa bladder supports) can be helpful for SUI treatment. An incontinence pessary can be fitted in the office, and fitting kits are available for both. Pessaries can safely be used in pregnancy, but there are no data on the efficacy of pessaries for treating SUI in pregnancy. In nonpregnant women, evidence demonstrates 63% satisfaction 3 months post–pessary placement for SUI.7

We do not recommend invasive procedures for the treatment of SUI during pregnancy or in the first 6 months following delivery. There is no evidence that elective cesarean delivery prevents persistent SUI postpartum.9

To identify and engage the proper pelvic floor muscles:

- Insert a finger in the vagina and squeeze the vaginal muscles around your finger.

- Imagine you are sitting on a marble and have to pick it up with the vaginal muscles.

- Squeeze the muscles you would use to stop the flow of urine or hold back flatulence.

Perform sets of 10, 2 to 3 times per day as follows:

- Squeeze: Engage the pelvic floor muscles as described above; avoid performing Kegels while voiding.

- Hold: For 2 to 10 seconds; increase the duration to 10 seconds as able.

- Relax: Completely relax muscles before initating the next squeeze.

Reference

1. UpToDate. Patient education: pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises (the basics). 2018. https://uptodatefree.ir/topic.htm?path=pelvic-muscle-kegel-exercises-the-basics. Accessed February 24, 2021.

Continue to: Managing SUI in the postpartum period...

Managing SUI in the postpartum period

After the first 6 months postpartum and exhaustion of conservative measures, we offer surgical interventions for women with persistent, bothersome incontinence. Surgery for SUI typically is not recommended until childbearing is complete, but it can be considered if the patient’s bother is significant.

For women with bothersome SUI who still desire future pregnancy, management options include periurethral bulking, a retropubic urethropexy (Burch procedure), or a midurethral sling procedure. Women who undergo an anti-incontinence procedure have an increased risk for urinary retention during a subsequent pregnancy.10 Most women with a midurethral sling will continue to be continent following an obstetric delivery.

Anticipatory guidance

At 3 months postpartum, the incidence of urinary incontinence is 6% to 40%, depending on parity and delivery type. Postpartum urinary incontinence is most common after instrumented vaginal delivery (32%) followed by spontaneous vaginal delivery (28%) and cesarean delivery (15%). The mean prevalence of any type of urinary incontinence is 33% at 3 months postpartum, and only small changes in the rate of urinary incontinence occur over the first postpartum year.11 While urinary incontinence is common postpartum, it should not be considered normal. We counsel that symptoms may improve spontaneously, but treatment can be initiated if the patient experiences significant bother.

A longitudinal cohort study that followed women from 3 months to 12 years postpartum found that, of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum, 76% continued to report incontinence at 12 years postpartum.12 We recommend that women be counseled that, even when symptoms resolve, they remain at increased risk for urinary incontinence in the future. Invasive therapies should be used to treat bothersome urinary incontinence, not to prevent future incontinence.

CASE 3 Fecal incontinence

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 3 weeks postpartum following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery complicated by a 3c laceration. She reports fecal urgency, inability to control flatus, and once-daily fecal incontinence.

How would you evaluate these symptoms?

Steps in evaluation

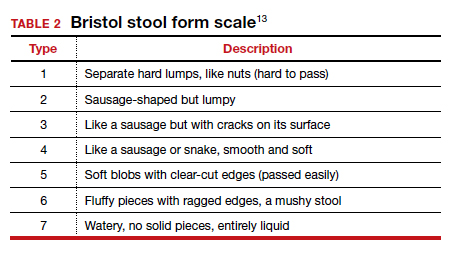

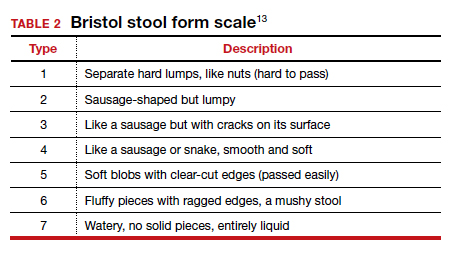

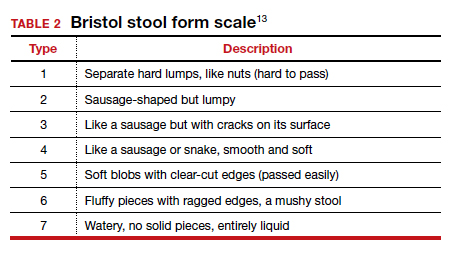

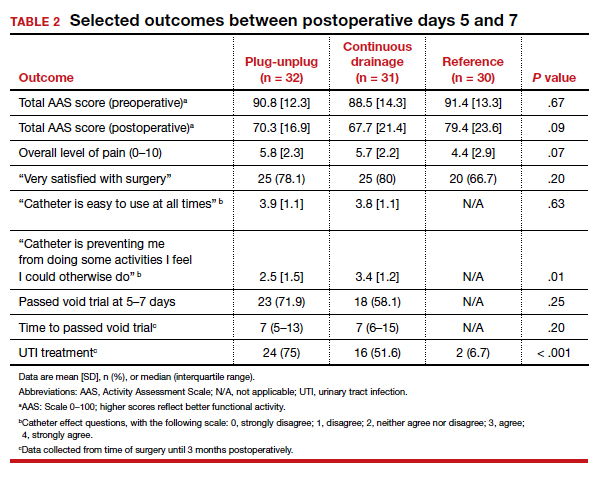

The initial evaluation should include an inquiry regarding the patient’s stool consistency and bowel regimen. The Bristol stool form scale can be used to help patients describe their typical bowel movements (TABLE 2).13 During healing, the goal is to achieve a Bristol type 4 stool, both to avoid straining and to improve continence, as loose stool is the most difficult to control.

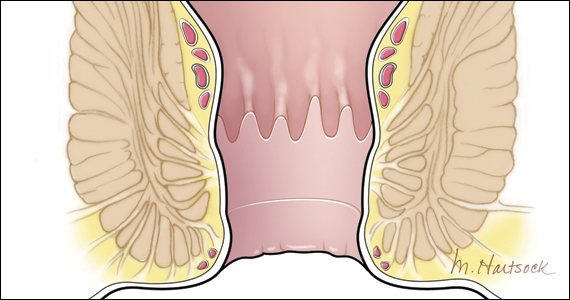

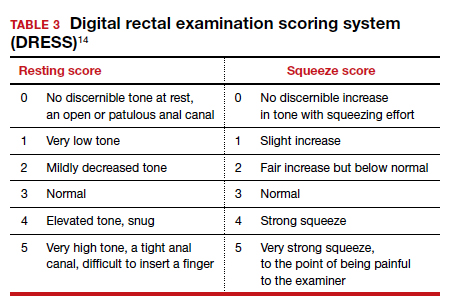

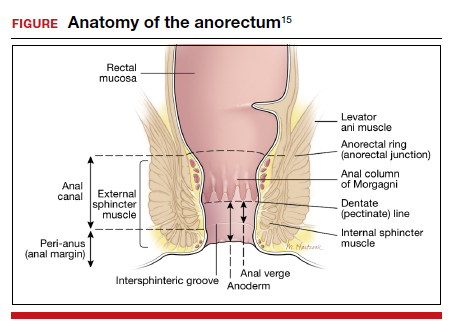

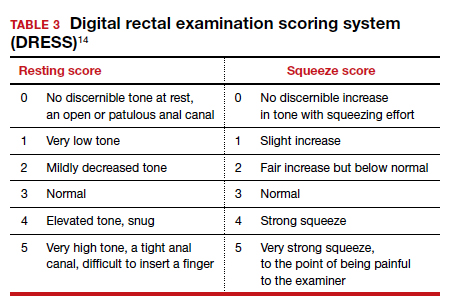

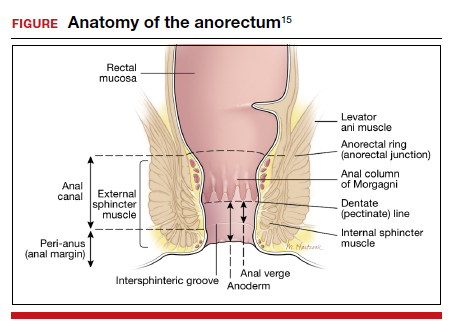

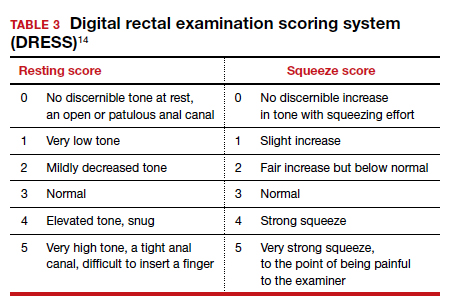

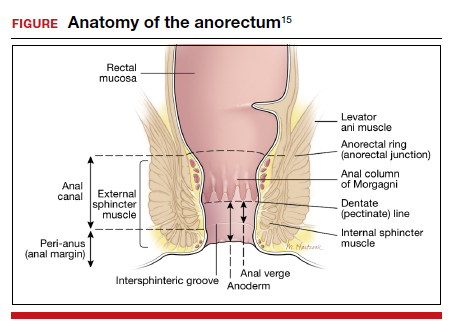

A physical examination can evaluate healing and sphincter integrity; it should include inspection of the distal vagina and perineal body and a digital rectal exam. Anal canal resting tone and squeeze strength should be evaluated, and the digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS) can be useful for quantification (TABLE 3).14 Lack of tone at rest in the anterolateral portion of the sphincter complex can indicate an internal anal sphincter defect, as 80% of the resting tone comes from this muscle (FIGURE).15

The rectovaginal septum should be assessed given the increased risk of rectovaginal fistula in women with obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). The patient should be instructed to contract the anal sphincter, allowing evaluation of muscular contraction. Lack of contraction anteriolaterally may indicate external anal sphincter separation.

Continue to: Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms...

Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms

The patient can be counseled regarding stool bulking, first with insoluble fiber supplementation and cessation of stool softeners if she is incontinent of liquid stool. If these measures are not effective, use of a constipating agent, such as loperamide, can improve stool consistency and thereby decrease incontinence episodes. PFPT with biofeedback can be offered as well. While typically we do not recommend initiating PFPT before 6 weeks postpartum, so the initial phases of healing can occur, early referral enables the patient to avoid a delay in access to care.

The patient also can be counseled about a referral to a pelvic floor specialist for further evaluation. A variety of peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics are being established by Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) physicians. These clinics provide the benefit of comprehensive care for pelvic floor disorders in this unique population.

When conservative measures fail. If a patient has persistent bowel control issues despite conservative measures, a referral to an FPMRS physician should be initiated.

Delivery route in future pregnancies

The risk of a subsequent OASI is low. While this means that many women can safely pursue a future vaginal delivery, a scheduled cesarean delivery is indicated for women with persistent bowel control issues, wound healing complications, and those who experienced psychological trauma from their delivery.16 We recommend a shared-decision making approach, reviewing modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors to help determine whether or not a future vaginal birth is appropriate. It is important to highlight that a cesarean delivery does not protect against fecal incontinence in women with a history of OASI; however, there is benefit in preventing worsening of anal incontinence, if present.17

CASE 4 Uterovaginal prolapse

A 36-year-old woman (G3P3) presents for her routine postpartum visit at 6 weeks after a spontaneous vaginal delivery without lacerations. She reports a persistent feeling of vaginal pressure and fullness. She thinks she felt a bulge with wiping after a bowel movement.

What options are available for this patient?

Prolapse in the peripartum population

Previous studies have revealed an increased prevalence of POP in pregnant women on examination compared with their nulligravid counterparts (47.6% vs 0%).18 With the changes in the hormonal milieu in pregnancy, as well as the weight of the gravid uterus on the pelvic floor, it is not surprising that pregnancy may be the inciting event to expose even transient defects in pelvic organ support.19

It is well established that increasing parity and, to a lesser extent, larger babies are associated with increased risk for future POP and surgery for prolapse. In the first year postpartum, nearly one-third of women have stage 2 or greater prolapse on exam, with studies demonstrating an increased prevalence of postpartum POP in women who delivered vaginally compared with those who delivered by cesarean.20,21

Initial evaluation

Diagnosis can be made during a routine pelvic exam by having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver while in the lithotomy position. Using half of a speculum permits evaluation of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls separately, and Valsalva during a bimanual exam can aid in evaluating descensus of the uterus and cervix.

Excellent free patient education resources available online through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association can be used to direct counseling.

Continue to: Treatments you can offer for POP...

Treatments you can offer for POP

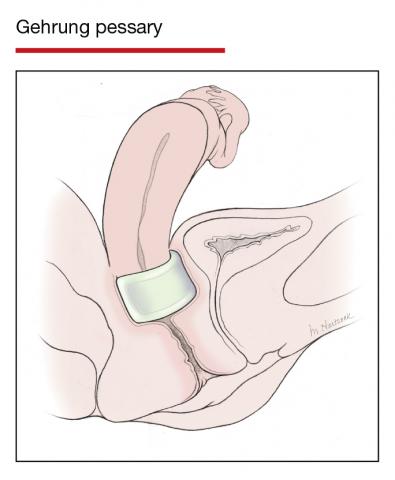

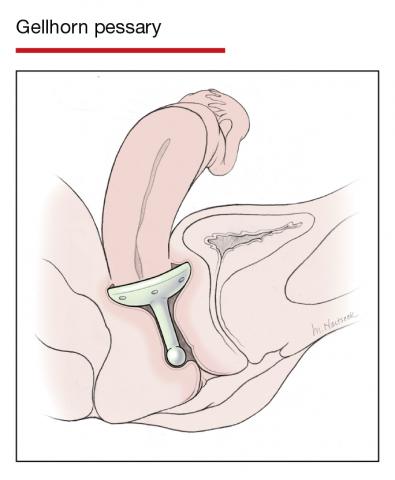

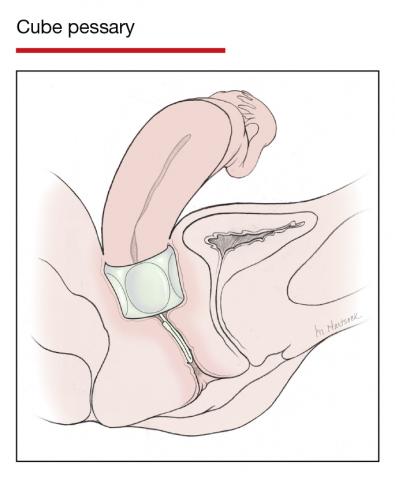

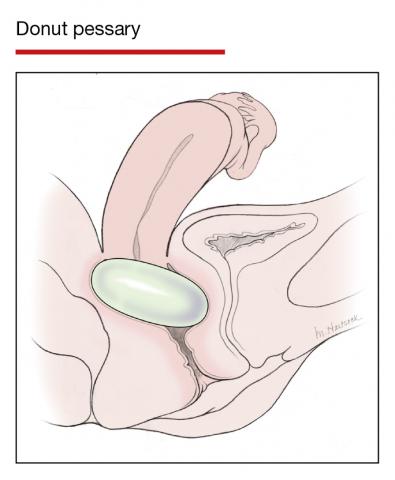

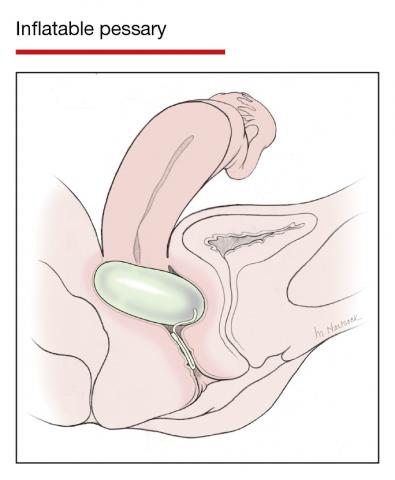

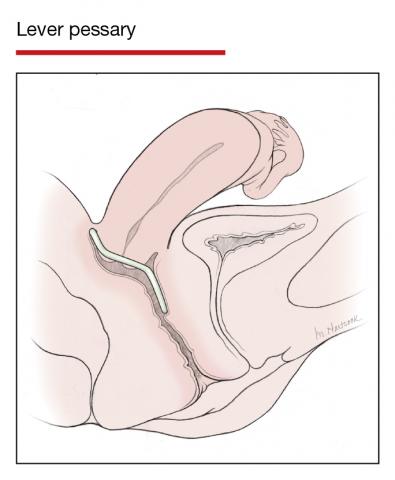

For pregnant or postpartum patients with bothersome prolapse, initial management options include pessary fitting and/or PFPT referral. In pregnancy, women often can be successfully fitted with a pessary for POP; however, as expulsion is a common issue, selection of a stiffer or space-occupying device may be more efficacious.

Often, early onset POP in pregnancy resolves as the gravid uterus lifts out of the pelvis in the second trimester, at which time the pessary can be discontinued. In the postpartum period, a pessary fitting can be undertaken similarly to that in nonpregnant patients. While data are lacking in the peripartum population, evidence supports the positive impact of PFPT on improving POP symptom bother.22 Additionally, for postpartum women who experience OASI, PFPT can produce significant improvement in subjective POP and associated bother.23

Impact of future childbearing wishes on treatment

The desire for future childbearing does not preclude treatment of patients experiencing bother from POP after conservative management options have failed. Both vaginal native tissue and mesh-augmented uterine-sparing repairs are performed by many FPMRS specialists and are associated with good outcomes. As with SUI, we do not recommend invasive treatment for POP during pregnancy or before 6 months postpartum.

In conclusion

Obstetric specialists play an essential role in caring for women with PFDs in the peripartum period. Basic evaluation, counseling, and management can be initiated using many of the resources already available in an obstetric ambulatory practice. Important adjunctive resources include those available for both providers and patients through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association. In addition, clinicians can partner with pelvic floor specialists through the growing number of FPMRS-run peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics across the country and pelvic floor physical therapists.

If these specialty clinics and therapists are not available in your area, FPMRS specialists, urologists, gastroenterologists, and/or colorectal surgeons can aid in patient diagnosis and management to reach the ultimate goal of improving PFDs in this at-risk population. ●

- Madsen AM, Hickman LC, Propst K. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. Forthcoming 2021.

- Bodner-Adler B, Kimberger O, Laml T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic floor disorders during early and late pregnancy in a cohort of Austrian women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1325-1330.

- Swenson CW, DePorre JA, Haefner JK, et al. Postpartum depression screening and pelvic floor symptoms among women referred to a specialty postpartum perineal clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:335.e1-335.e6.

- Skinner EM, Dietz HP. Psychological and somatic sequelae of traumatic vaginal delivery: a literature review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:309-314.

- Yohay D, Weintraub AY, Mauer-Perry N, et al. Prevalence and trends of pelvic floor disorders in late pregnancy and after delivery in a cohort of Israeli women using the PFDI-20. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:35-39.

- Gregory WT, Sibai BM. Obstetrics and pelvic floor disorders. In: Walters M, Karram M, eds. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015:224-237.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD007471.

- Foldspang A, Hvidman L, Mommsen S, et al. Risk of postpartum urinary incontinence associated with pregnancy and mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:923-927.

- Wieslander CK, Weinstein MM, Handa V, et al. Pregnancy in women with prior treatments for pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:299-305.

- Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1511-1522.

- MacArthur C, Wilson D, Herbison P, et al; Prolong Study Group. Urinary incontinence persisting after childbirth: extent, delivery history, and effects in a 12-year longitudinal cohort study. BJOG. 2016;123:1022-1029.

- Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:693-703

- Orkin BA, Sinykin SB, Lloyd PC. The digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS). Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1656-1660.

- UpToDate. Repair of episiotomy and perineal lacerations associated with childbirth. 2020. https://www-uptodate-com .ccmain.ohionet.org/contents/repair-of-perineal-and-other -lacerations-associated-with-childbirth?search=repair%20 episiotomy&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usa ge_type=default&display_rank=1. Accessed February 28, 2021.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 198: prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e87-e102.

- Jangö H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthøj S, et al. Long-term anal incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injury—does grade of tear matter? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:232.e1-232.e10.

- O’Boyle AL, Woodman PJ, O’Boyle JD, et al. Pelvic organ support in nulliparous pregnant and nonpregnant women: a case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:99-102.

- Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, et al. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119 (2, pt 1):233-239.

- Handa VL, Nygaard I, Kenton K, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic organ support among primiparous women in the first year after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1407-1411.

- O’Boyle AL, O’Boyle JD, Calhoun B, et al. Pelvic organ support in pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:69-72.

- Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al; POPPY Trial Collaborators. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:796-806.

- Von Bargen E, Haviland MJ, Chang OH, et al. Evaluation of postpartum pelvic floor physical therapy on obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000849.

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) affect many pregnant and newly postpartum women. These conditions, including urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be overshadowed by common pregnancy and postpartum concerns (TABLE 1).1 With the use of a few quick screening questions, however, PFDs easily can be identified in this at-risk population. Active management need not be delayed until after delivery for women experiencing bother, as options exist for women with PFDs during pregnancy as well as postpartum.

In this article, we discuss the common PFDs that obstetric clinicians face in the context of case scenarios and review how you can be better equipped to care for affected individuals.

CASE 1 Screening

A 30-year-old woman (G1P1) presents for her routine postpartum visit after an operative vaginal delivery with a second-degree laceration.

How would you screen this patient for PFDs?

Why screening for PFDs matters

While there are no validated PFD screening tools for this patient population, clinicians can ask a series of brief open-ended questions as part of the review of systems to efficiently evaluate for the common PFDs in peripartum patients (see “Screening questions to evaluate patients for peripartum pelvic floor disorders” below).

Pelvic floor disorders in the peripartum period can have a significant negative impact. In pregnancy, nearly half of women report psychological strain due to the presence of bowel, bladder, prolapse, or sexual dysfunction symptoms.2 Postpartum, PFDs have negative effects on overall health, well-being, and self-esteem, with significantly increased rates of postpartum depression in women who experience urinary incontinence.3,4 Proactively inquiring about PFD symptoms, providing anticipatory guidance, and recommending treatment options can positively impact a patient in multiple domains.

Sometimes during pregnancy or after having a baby, a woman experiences pelvic floor symptoms. Do you have any of the following?

- leakage with coughing, laughing, sneezing, or physical activity

- urgency to urinate or leakage due to urgency

- bulging or pressure within the vagina

- pain with intercourse

- accidental bowel leakage of stool or flatus

CASE 2 Stress urinary incontinence

A 27-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 2 months following spontaneous vaginal delivery with symptoms of urine leakage with laughing and running. Her urinary incontinence has been improving since delivery, but it continues to be bothersome.

What would you recommend for this patient?

Conservative SUI management strategies in pregnancy

Urinary tract symptoms are common in pregnancy, with up to 41.8% of women reporting urinary symptom distress in the third trimester.5 During pregnancy, estrogen and progesterone decrease urethral pressure that, together with increased intra-abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus, can cause or worsen stress urinary incontinence (SUI).6

During pregnancy, women should be offered conservative therapies for SUI. For women who can perform a pelvic floor contraction (a Kegel exercise), self-guided pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs) may be helpful (see “Pelvic floor muscle exercises” below). We recommend that women start with 1 to 2 sets of 10 Kegel exercises per day and that they hold the squeeze for 2 to 3 seconds, working up to holding for 10 seconds. The goal is to strengthen and improve muscle control so that the Kegel squeeze can be paired with activities that cause SUI.

For women who are unable to perform a Kegel exercise or are not improving with a home PFME regimen, referral to pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be considered. While data support the efficacy of PFPT for SUI treatment in nonpregnant women,7 data are lacking on PFME in pregnancy.

In women without urinary incontinence, PFME in early pregnancy can prevent the onset of incontinence in late pregnancy and the postpartum period.8 By contrast, the same 2020 Cochrane Review found no evidence that antenatal pelvic floor muscle therapy in incontinent women decreases incontinence in mid- or late-pregnancy or in the postpartum period.8 As the quality of this evidence is very low and there is no evidence of harm with PFME, we continue to recommend it for women with bothersome SUI.

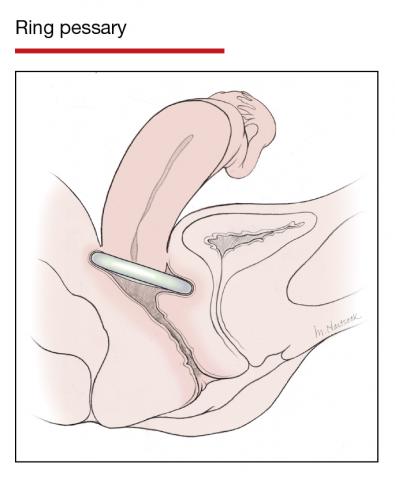

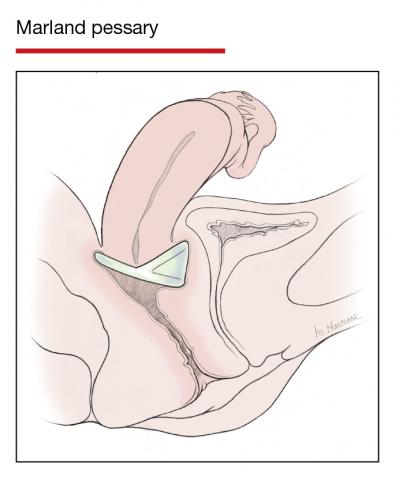

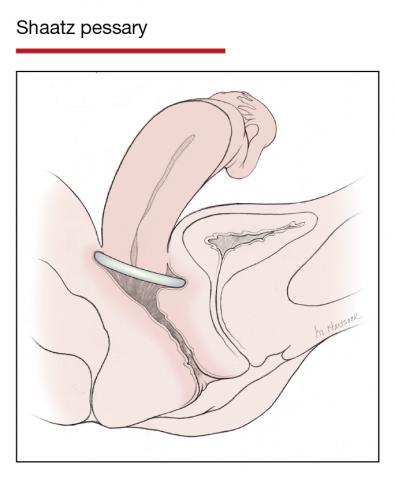

Incontinence pessaries or vaginal inserts (such as Poise Impressa bladder supports) can be helpful for SUI treatment. An incontinence pessary can be fitted in the office, and fitting kits are available for both. Pessaries can safely be used in pregnancy, but there are no data on the efficacy of pessaries for treating SUI in pregnancy. In nonpregnant women, evidence demonstrates 63% satisfaction 3 months post–pessary placement for SUI.7

We do not recommend invasive procedures for the treatment of SUI during pregnancy or in the first 6 months following delivery. There is no evidence that elective cesarean delivery prevents persistent SUI postpartum.9

To identify and engage the proper pelvic floor muscles:

- Insert a finger in the vagina and squeeze the vaginal muscles around your finger.

- Imagine you are sitting on a marble and have to pick it up with the vaginal muscles.

- Squeeze the muscles you would use to stop the flow of urine or hold back flatulence.

Perform sets of 10, 2 to 3 times per day as follows:

- Squeeze: Engage the pelvic floor muscles as described above; avoid performing Kegels while voiding.

- Hold: For 2 to 10 seconds; increase the duration to 10 seconds as able.

- Relax: Completely relax muscles before initating the next squeeze.

Reference

1. UpToDate. Patient education: pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises (the basics). 2018. https://uptodatefree.ir/topic.htm?path=pelvic-muscle-kegel-exercises-the-basics. Accessed February 24, 2021.

Continue to: Managing SUI in the postpartum period...

Managing SUI in the postpartum period

After the first 6 months postpartum and exhaustion of conservative measures, we offer surgical interventions for women with persistent, bothersome incontinence. Surgery for SUI typically is not recommended until childbearing is complete, but it can be considered if the patient’s bother is significant.

For women with bothersome SUI who still desire future pregnancy, management options include periurethral bulking, a retropubic urethropexy (Burch procedure), or a midurethral sling procedure. Women who undergo an anti-incontinence procedure have an increased risk for urinary retention during a subsequent pregnancy.10 Most women with a midurethral sling will continue to be continent following an obstetric delivery.

Anticipatory guidance

At 3 months postpartum, the incidence of urinary incontinence is 6% to 40%, depending on parity and delivery type. Postpartum urinary incontinence is most common after instrumented vaginal delivery (32%) followed by spontaneous vaginal delivery (28%) and cesarean delivery (15%). The mean prevalence of any type of urinary incontinence is 33% at 3 months postpartum, and only small changes in the rate of urinary incontinence occur over the first postpartum year.11 While urinary incontinence is common postpartum, it should not be considered normal. We counsel that symptoms may improve spontaneously, but treatment can be initiated if the patient experiences significant bother.

A longitudinal cohort study that followed women from 3 months to 12 years postpartum found that, of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum, 76% continued to report incontinence at 12 years postpartum.12 We recommend that women be counseled that, even when symptoms resolve, they remain at increased risk for urinary incontinence in the future. Invasive therapies should be used to treat bothersome urinary incontinence, not to prevent future incontinence.

CASE 3 Fecal incontinence

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 3 weeks postpartum following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery complicated by a 3c laceration. She reports fecal urgency, inability to control flatus, and once-daily fecal incontinence.

How would you evaluate these symptoms?

Steps in evaluation

The initial evaluation should include an inquiry regarding the patient’s stool consistency and bowel regimen. The Bristol stool form scale can be used to help patients describe their typical bowel movements (TABLE 2).13 During healing, the goal is to achieve a Bristol type 4 stool, both to avoid straining and to improve continence, as loose stool is the most difficult to control.

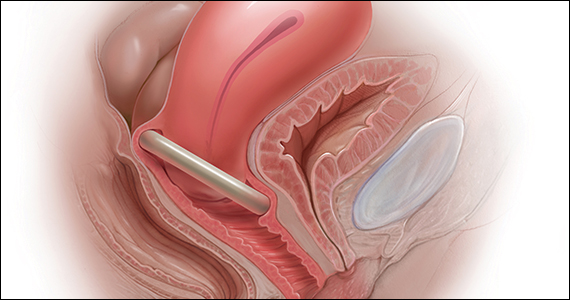

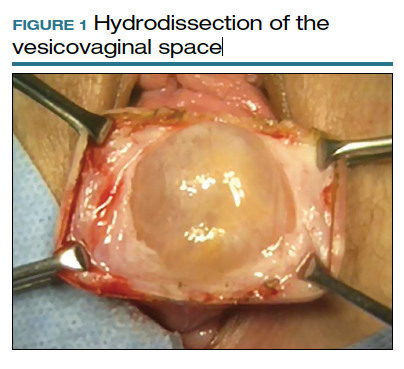

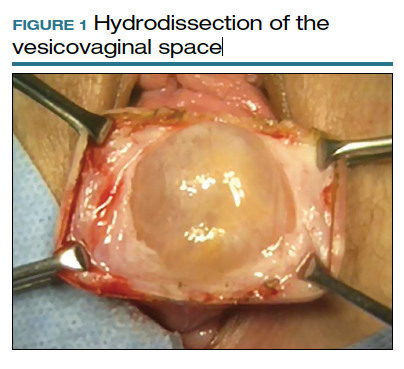

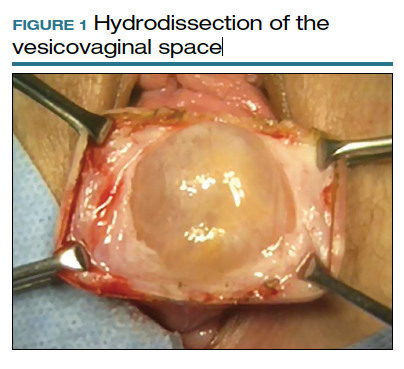

A physical examination can evaluate healing and sphincter integrity; it should include inspection of the distal vagina and perineal body and a digital rectal exam. Anal canal resting tone and squeeze strength should be evaluated, and the digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS) can be useful for quantification (TABLE 3).14 Lack of tone at rest in the anterolateral portion of the sphincter complex can indicate an internal anal sphincter defect, as 80% of the resting tone comes from this muscle (FIGURE).15

The rectovaginal septum should be assessed given the increased risk of rectovaginal fistula in women with obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). The patient should be instructed to contract the anal sphincter, allowing evaluation of muscular contraction. Lack of contraction anteriolaterally may indicate external anal sphincter separation.

Continue to: Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms...

Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms

The patient can be counseled regarding stool bulking, first with insoluble fiber supplementation and cessation of stool softeners if she is incontinent of liquid stool. If these measures are not effective, use of a constipating agent, such as loperamide, can improve stool consistency and thereby decrease incontinence episodes. PFPT with biofeedback can be offered as well. While typically we do not recommend initiating PFPT before 6 weeks postpartum, so the initial phases of healing can occur, early referral enables the patient to avoid a delay in access to care.

The patient also can be counseled about a referral to a pelvic floor specialist for further evaluation. A variety of peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics are being established by Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) physicians. These clinics provide the benefit of comprehensive care for pelvic floor disorders in this unique population.

When conservative measures fail. If a patient has persistent bowel control issues despite conservative measures, a referral to an FPMRS physician should be initiated.

Delivery route in future pregnancies

The risk of a subsequent OASI is low. While this means that many women can safely pursue a future vaginal delivery, a scheduled cesarean delivery is indicated for women with persistent bowel control issues, wound healing complications, and those who experienced psychological trauma from their delivery.16 We recommend a shared-decision making approach, reviewing modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors to help determine whether or not a future vaginal birth is appropriate. It is important to highlight that a cesarean delivery does not protect against fecal incontinence in women with a history of OASI; however, there is benefit in preventing worsening of anal incontinence, if present.17

CASE 4 Uterovaginal prolapse

A 36-year-old woman (G3P3) presents for her routine postpartum visit at 6 weeks after a spontaneous vaginal delivery without lacerations. She reports a persistent feeling of vaginal pressure and fullness. She thinks she felt a bulge with wiping after a bowel movement.

What options are available for this patient?

Prolapse in the peripartum population

Previous studies have revealed an increased prevalence of POP in pregnant women on examination compared with their nulligravid counterparts (47.6% vs 0%).18 With the changes in the hormonal milieu in pregnancy, as well as the weight of the gravid uterus on the pelvic floor, it is not surprising that pregnancy may be the inciting event to expose even transient defects in pelvic organ support.19

It is well established that increasing parity and, to a lesser extent, larger babies are associated with increased risk for future POP and surgery for prolapse. In the first year postpartum, nearly one-third of women have stage 2 or greater prolapse on exam, with studies demonstrating an increased prevalence of postpartum POP in women who delivered vaginally compared with those who delivered by cesarean.20,21

Initial evaluation

Diagnosis can be made during a routine pelvic exam by having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver while in the lithotomy position. Using half of a speculum permits evaluation of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls separately, and Valsalva during a bimanual exam can aid in evaluating descensus of the uterus and cervix.

Excellent free patient education resources available online through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association can be used to direct counseling.

Continue to: Treatments you can offer for POP...

Treatments you can offer for POP

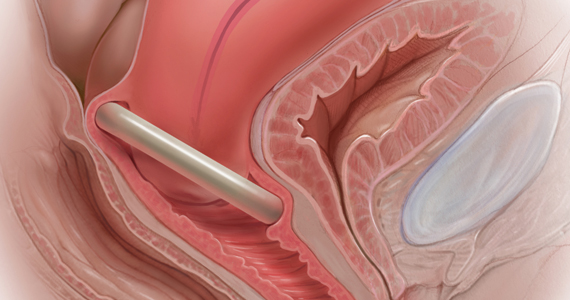

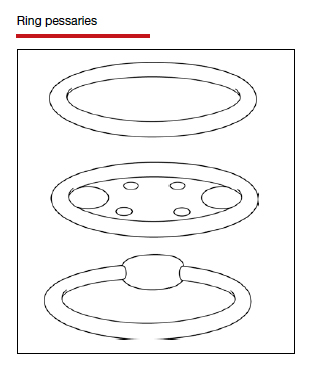

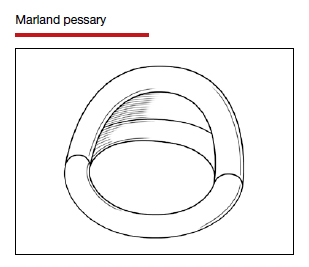

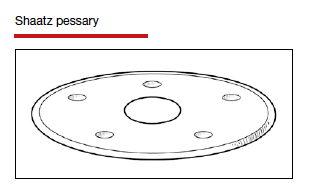

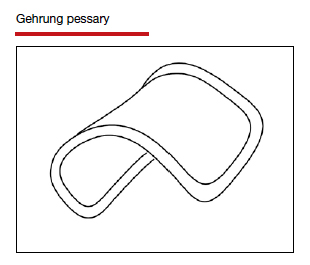

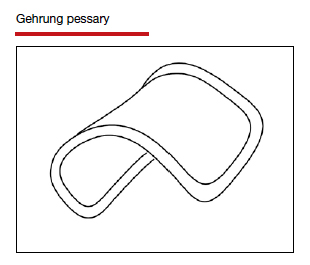

For pregnant or postpartum patients with bothersome prolapse, initial management options include pessary fitting and/or PFPT referral. In pregnancy, women often can be successfully fitted with a pessary for POP; however, as expulsion is a common issue, selection of a stiffer or space-occupying device may be more efficacious.

Often, early onset POP in pregnancy resolves as the gravid uterus lifts out of the pelvis in the second trimester, at which time the pessary can be discontinued. In the postpartum period, a pessary fitting can be undertaken similarly to that in nonpregnant patients. While data are lacking in the peripartum population, evidence supports the positive impact of PFPT on improving POP symptom bother.22 Additionally, for postpartum women who experience OASI, PFPT can produce significant improvement in subjective POP and associated bother.23

Impact of future childbearing wishes on treatment

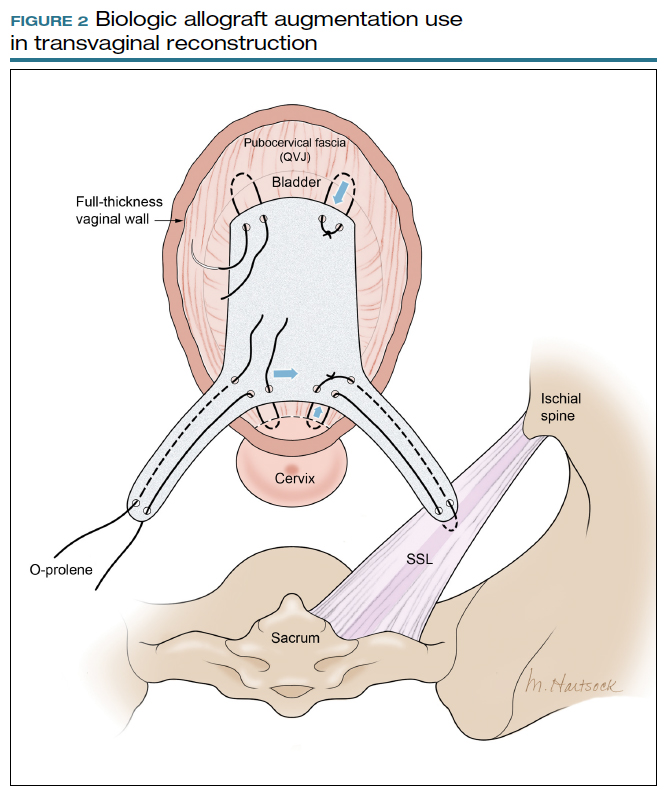

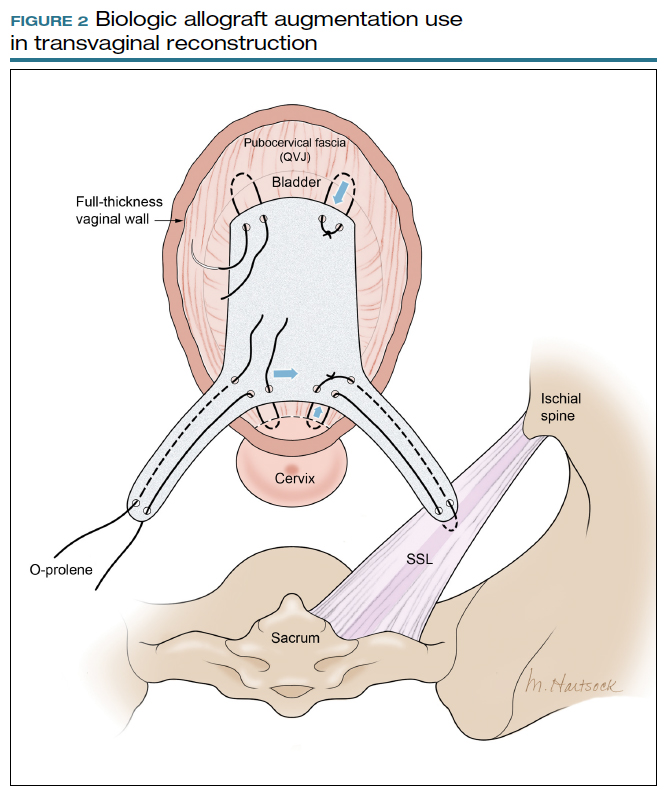

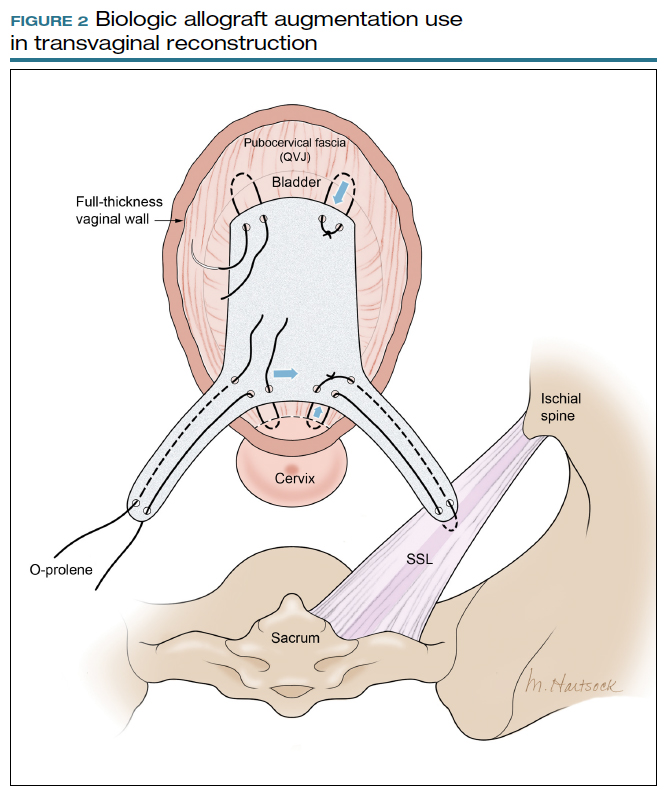

The desire for future childbearing does not preclude treatment of patients experiencing bother from POP after conservative management options have failed. Both vaginal native tissue and mesh-augmented uterine-sparing repairs are performed by many FPMRS specialists and are associated with good outcomes. As with SUI, we do not recommend invasive treatment for POP during pregnancy or before 6 months postpartum.

In conclusion

Obstetric specialists play an essential role in caring for women with PFDs in the peripartum period. Basic evaluation, counseling, and management can be initiated using many of the resources already available in an obstetric ambulatory practice. Important adjunctive resources include those available for both providers and patients through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association. In addition, clinicians can partner with pelvic floor specialists through the growing number of FPMRS-run peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics across the country and pelvic floor physical therapists.

If these specialty clinics and therapists are not available in your area, FPMRS specialists, urologists, gastroenterologists, and/or colorectal surgeons can aid in patient diagnosis and management to reach the ultimate goal of improving PFDs in this at-risk population. ●

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) affect many pregnant and newly postpartum women. These conditions, including urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be overshadowed by common pregnancy and postpartum concerns (TABLE 1).1 With the use of a few quick screening questions, however, PFDs easily can be identified in this at-risk population. Active management need not be delayed until after delivery for women experiencing bother, as options exist for women with PFDs during pregnancy as well as postpartum.

In this article, we discuss the common PFDs that obstetric clinicians face in the context of case scenarios and review how you can be better equipped to care for affected individuals.

CASE 1 Screening

A 30-year-old woman (G1P1) presents for her routine postpartum visit after an operative vaginal delivery with a second-degree laceration.

How would you screen this patient for PFDs?

Why screening for PFDs matters

While there are no validated PFD screening tools for this patient population, clinicians can ask a series of brief open-ended questions as part of the review of systems to efficiently evaluate for the common PFDs in peripartum patients (see “Screening questions to evaluate patients for peripartum pelvic floor disorders” below).

Pelvic floor disorders in the peripartum period can have a significant negative impact. In pregnancy, nearly half of women report psychological strain due to the presence of bowel, bladder, prolapse, or sexual dysfunction symptoms.2 Postpartum, PFDs have negative effects on overall health, well-being, and self-esteem, with significantly increased rates of postpartum depression in women who experience urinary incontinence.3,4 Proactively inquiring about PFD symptoms, providing anticipatory guidance, and recommending treatment options can positively impact a patient in multiple domains.

Sometimes during pregnancy or after having a baby, a woman experiences pelvic floor symptoms. Do you have any of the following?

- leakage with coughing, laughing, sneezing, or physical activity

- urgency to urinate or leakage due to urgency

- bulging or pressure within the vagina

- pain with intercourse

- accidental bowel leakage of stool or flatus

CASE 2 Stress urinary incontinence

A 27-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 2 months following spontaneous vaginal delivery with symptoms of urine leakage with laughing and running. Her urinary incontinence has been improving since delivery, but it continues to be bothersome.

What would you recommend for this patient?

Conservative SUI management strategies in pregnancy

Urinary tract symptoms are common in pregnancy, with up to 41.8% of women reporting urinary symptom distress in the third trimester.5 During pregnancy, estrogen and progesterone decrease urethral pressure that, together with increased intra-abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus, can cause or worsen stress urinary incontinence (SUI).6

During pregnancy, women should be offered conservative therapies for SUI. For women who can perform a pelvic floor contraction (a Kegel exercise), self-guided pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs) may be helpful (see “Pelvic floor muscle exercises” below). We recommend that women start with 1 to 2 sets of 10 Kegel exercises per day and that they hold the squeeze for 2 to 3 seconds, working up to holding for 10 seconds. The goal is to strengthen and improve muscle control so that the Kegel squeeze can be paired with activities that cause SUI.

For women who are unable to perform a Kegel exercise or are not improving with a home PFME regimen, referral to pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be considered. While data support the efficacy of PFPT for SUI treatment in nonpregnant women,7 data are lacking on PFME in pregnancy.

In women without urinary incontinence, PFME in early pregnancy can prevent the onset of incontinence in late pregnancy and the postpartum period.8 By contrast, the same 2020 Cochrane Review found no evidence that antenatal pelvic floor muscle therapy in incontinent women decreases incontinence in mid- or late-pregnancy or in the postpartum period.8 As the quality of this evidence is very low and there is no evidence of harm with PFME, we continue to recommend it for women with bothersome SUI.

Incontinence pessaries or vaginal inserts (such as Poise Impressa bladder supports) can be helpful for SUI treatment. An incontinence pessary can be fitted in the office, and fitting kits are available for both. Pessaries can safely be used in pregnancy, but there are no data on the efficacy of pessaries for treating SUI in pregnancy. In nonpregnant women, evidence demonstrates 63% satisfaction 3 months post–pessary placement for SUI.7

We do not recommend invasive procedures for the treatment of SUI during pregnancy or in the first 6 months following delivery. There is no evidence that elective cesarean delivery prevents persistent SUI postpartum.9

To identify and engage the proper pelvic floor muscles:

- Insert a finger in the vagina and squeeze the vaginal muscles around your finger.

- Imagine you are sitting on a marble and have to pick it up with the vaginal muscles.

- Squeeze the muscles you would use to stop the flow of urine or hold back flatulence.

Perform sets of 10, 2 to 3 times per day as follows:

- Squeeze: Engage the pelvic floor muscles as described above; avoid performing Kegels while voiding.

- Hold: For 2 to 10 seconds; increase the duration to 10 seconds as able.

- Relax: Completely relax muscles before initating the next squeeze.

Reference

1. UpToDate. Patient education: pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises (the basics). 2018. https://uptodatefree.ir/topic.htm?path=pelvic-muscle-kegel-exercises-the-basics. Accessed February 24, 2021.

Continue to: Managing SUI in the postpartum period...

Managing SUI in the postpartum period

After the first 6 months postpartum and exhaustion of conservative measures, we offer surgical interventions for women with persistent, bothersome incontinence. Surgery for SUI typically is not recommended until childbearing is complete, but it can be considered if the patient’s bother is significant.

For women with bothersome SUI who still desire future pregnancy, management options include periurethral bulking, a retropubic urethropexy (Burch procedure), or a midurethral sling procedure. Women who undergo an anti-incontinence procedure have an increased risk for urinary retention during a subsequent pregnancy.10 Most women with a midurethral sling will continue to be continent following an obstetric delivery.

Anticipatory guidance

At 3 months postpartum, the incidence of urinary incontinence is 6% to 40%, depending on parity and delivery type. Postpartum urinary incontinence is most common after instrumented vaginal delivery (32%) followed by spontaneous vaginal delivery (28%) and cesarean delivery (15%). The mean prevalence of any type of urinary incontinence is 33% at 3 months postpartum, and only small changes in the rate of urinary incontinence occur over the first postpartum year.11 While urinary incontinence is common postpartum, it should not be considered normal. We counsel that symptoms may improve spontaneously, but treatment can be initiated if the patient experiences significant bother.

A longitudinal cohort study that followed women from 3 months to 12 years postpartum found that, of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum, 76% continued to report incontinence at 12 years postpartum.12 We recommend that women be counseled that, even when symptoms resolve, they remain at increased risk for urinary incontinence in the future. Invasive therapies should be used to treat bothersome urinary incontinence, not to prevent future incontinence.

CASE 3 Fecal incontinence

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 3 weeks postpartum following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery complicated by a 3c laceration. She reports fecal urgency, inability to control flatus, and once-daily fecal incontinence.

How would you evaluate these symptoms?

Steps in evaluation

The initial evaluation should include an inquiry regarding the patient’s stool consistency and bowel regimen. The Bristol stool form scale can be used to help patients describe their typical bowel movements (TABLE 2).13 During healing, the goal is to achieve a Bristol type 4 stool, both to avoid straining and to improve continence, as loose stool is the most difficult to control.

A physical examination can evaluate healing and sphincter integrity; it should include inspection of the distal vagina and perineal body and a digital rectal exam. Anal canal resting tone and squeeze strength should be evaluated, and the digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS) can be useful for quantification (TABLE 3).14 Lack of tone at rest in the anterolateral portion of the sphincter complex can indicate an internal anal sphincter defect, as 80% of the resting tone comes from this muscle (FIGURE).15

The rectovaginal septum should be assessed given the increased risk of rectovaginal fistula in women with obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). The patient should be instructed to contract the anal sphincter, allowing evaluation of muscular contraction. Lack of contraction anteriolaterally may indicate external anal sphincter separation.

Continue to: Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms...

Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms

The patient can be counseled regarding stool bulking, first with insoluble fiber supplementation and cessation of stool softeners if she is incontinent of liquid stool. If these measures are not effective, use of a constipating agent, such as loperamide, can improve stool consistency and thereby decrease incontinence episodes. PFPT with biofeedback can be offered as well. While typically we do not recommend initiating PFPT before 6 weeks postpartum, so the initial phases of healing can occur, early referral enables the patient to avoid a delay in access to care.

The patient also can be counseled about a referral to a pelvic floor specialist for further evaluation. A variety of peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics are being established by Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) physicians. These clinics provide the benefit of comprehensive care for pelvic floor disorders in this unique population.

When conservative measures fail. If a patient has persistent bowel control issues despite conservative measures, a referral to an FPMRS physician should be initiated.

Delivery route in future pregnancies

The risk of a subsequent OASI is low. While this means that many women can safely pursue a future vaginal delivery, a scheduled cesarean delivery is indicated for women with persistent bowel control issues, wound healing complications, and those who experienced psychological trauma from their delivery.16 We recommend a shared-decision making approach, reviewing modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors to help determine whether or not a future vaginal birth is appropriate. It is important to highlight that a cesarean delivery does not protect against fecal incontinence in women with a history of OASI; however, there is benefit in preventing worsening of anal incontinence, if present.17

CASE 4 Uterovaginal prolapse

A 36-year-old woman (G3P3) presents for her routine postpartum visit at 6 weeks after a spontaneous vaginal delivery without lacerations. She reports a persistent feeling of vaginal pressure and fullness. She thinks she felt a bulge with wiping after a bowel movement.

What options are available for this patient?

Prolapse in the peripartum population

Previous studies have revealed an increased prevalence of POP in pregnant women on examination compared with their nulligravid counterparts (47.6% vs 0%).18 With the changes in the hormonal milieu in pregnancy, as well as the weight of the gravid uterus on the pelvic floor, it is not surprising that pregnancy may be the inciting event to expose even transient defects in pelvic organ support.19

It is well established that increasing parity and, to a lesser extent, larger babies are associated with increased risk for future POP and surgery for prolapse. In the first year postpartum, nearly one-third of women have stage 2 or greater prolapse on exam, with studies demonstrating an increased prevalence of postpartum POP in women who delivered vaginally compared with those who delivered by cesarean.20,21

Initial evaluation

Diagnosis can be made during a routine pelvic exam by having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver while in the lithotomy position. Using half of a speculum permits evaluation of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls separately, and Valsalva during a bimanual exam can aid in evaluating descensus of the uterus and cervix.

Excellent free patient education resources available online through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association can be used to direct counseling.

Continue to: Treatments you can offer for POP...

Treatments you can offer for POP

For pregnant or postpartum patients with bothersome prolapse, initial management options include pessary fitting and/or PFPT referral. In pregnancy, women often can be successfully fitted with a pessary for POP; however, as expulsion is a common issue, selection of a stiffer or space-occupying device may be more efficacious.

Often, early onset POP in pregnancy resolves as the gravid uterus lifts out of the pelvis in the second trimester, at which time the pessary can be discontinued. In the postpartum period, a pessary fitting can be undertaken similarly to that in nonpregnant patients. While data are lacking in the peripartum population, evidence supports the positive impact of PFPT on improving POP symptom bother.22 Additionally, for postpartum women who experience OASI, PFPT can produce significant improvement in subjective POP and associated bother.23

Impact of future childbearing wishes on treatment

The desire for future childbearing does not preclude treatment of patients experiencing bother from POP after conservative management options have failed. Both vaginal native tissue and mesh-augmented uterine-sparing repairs are performed by many FPMRS specialists and are associated with good outcomes. As with SUI, we do not recommend invasive treatment for POP during pregnancy or before 6 months postpartum.

In conclusion

Obstetric specialists play an essential role in caring for women with PFDs in the peripartum period. Basic evaluation, counseling, and management can be initiated using many of the resources already available in an obstetric ambulatory practice. Important adjunctive resources include those available for both providers and patients through the American Urogynecologic Society and the International Urogynecological Association. In addition, clinicians can partner with pelvic floor specialists through the growing number of FPMRS-run peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics across the country and pelvic floor physical therapists.

If these specialty clinics and therapists are not available in your area, FPMRS specialists, urologists, gastroenterologists, and/or colorectal surgeons can aid in patient diagnosis and management to reach the ultimate goal of improving PFDs in this at-risk population. ●

- Madsen AM, Hickman LC, Propst K. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. Forthcoming 2021.

- Bodner-Adler B, Kimberger O, Laml T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic floor disorders during early and late pregnancy in a cohort of Austrian women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1325-1330.

- Swenson CW, DePorre JA, Haefner JK, et al. Postpartum depression screening and pelvic floor symptoms among women referred to a specialty postpartum perineal clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:335.e1-335.e6.

- Skinner EM, Dietz HP. Psychological and somatic sequelae of traumatic vaginal delivery: a literature review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:309-314.

- Yohay D, Weintraub AY, Mauer-Perry N, et al. Prevalence and trends of pelvic floor disorders in late pregnancy and after delivery in a cohort of Israeli women using the PFDI-20. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:35-39.

- Gregory WT, Sibai BM. Obstetrics and pelvic floor disorders. In: Walters M, Karram M, eds. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015:224-237.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD007471.

- Foldspang A, Hvidman L, Mommsen S, et al. Risk of postpartum urinary incontinence associated with pregnancy and mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:923-927.

- Wieslander CK, Weinstein MM, Handa V, et al. Pregnancy in women with prior treatments for pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:299-305.

- Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1511-1522.

- MacArthur C, Wilson D, Herbison P, et al; Prolong Study Group. Urinary incontinence persisting after childbirth: extent, delivery history, and effects in a 12-year longitudinal cohort study. BJOG. 2016;123:1022-1029.

- Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:693-703

- Orkin BA, Sinykin SB, Lloyd PC. The digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS). Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1656-1660.

- UpToDate. Repair of episiotomy and perineal lacerations associated with childbirth. 2020. https://www-uptodate-com .ccmain.ohionet.org/contents/repair-of-perineal-and-other -lacerations-associated-with-childbirth?search=repair%20 episiotomy&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usa ge_type=default&display_rank=1. Accessed February 28, 2021.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 198: prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e87-e102.

- Jangö H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthøj S, et al. Long-term anal incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injury—does grade of tear matter? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:232.e1-232.e10.

- O’Boyle AL, Woodman PJ, O’Boyle JD, et al. Pelvic organ support in nulliparous pregnant and nonpregnant women: a case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:99-102.

- Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, et al. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119 (2, pt 1):233-239.

- Handa VL, Nygaard I, Kenton K, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic organ support among primiparous women in the first year after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1407-1411.

- O’Boyle AL, O’Boyle JD, Calhoun B, et al. Pelvic organ support in pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:69-72.

- Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al; POPPY Trial Collaborators. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:796-806.

- Von Bargen E, Haviland MJ, Chang OH, et al. Evaluation of postpartum pelvic floor physical therapy on obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000849.

- Madsen AM, Hickman LC, Propst K. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. Forthcoming 2021.

- Bodner-Adler B, Kimberger O, Laml T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic floor disorders during early and late pregnancy in a cohort of Austrian women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1325-1330.

- Swenson CW, DePorre JA, Haefner JK, et al. Postpartum depression screening and pelvic floor symptoms among women referred to a specialty postpartum perineal clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:335.e1-335.e6.

- Skinner EM, Dietz HP. Psychological and somatic sequelae of traumatic vaginal delivery: a literature review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:309-314.

- Yohay D, Weintraub AY, Mauer-Perry N, et al. Prevalence and trends of pelvic floor disorders in late pregnancy and after delivery in a cohort of Israeli women using the PFDI-20. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:35-39.

- Gregory WT, Sibai BM. Obstetrics and pelvic floor disorders. In: Walters M, Karram M, eds. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015:224-237.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

- Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD007471.

- Foldspang A, Hvidman L, Mommsen S, et al. Risk of postpartum urinary incontinence associated with pregnancy and mode of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:923-927.

- Wieslander CK, Weinstein MM, Handa V, et al. Pregnancy in women with prior treatments for pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:299-305.

- Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1511-1522.

- MacArthur C, Wilson D, Herbison P, et al; Prolong Study Group. Urinary incontinence persisting after childbirth: extent, delivery history, and effects in a 12-year longitudinal cohort study. BJOG. 2016;123:1022-1029.

- Blake MR, Raker JM, Whelan K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:693-703

- Orkin BA, Sinykin SB, Lloyd PC. The digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS). Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1656-1660.

- UpToDate. Repair of episiotomy and perineal lacerations associated with childbirth. 2020. https://www-uptodate-com .ccmain.ohionet.org/contents/repair-of-perineal-and-other -lacerations-associated-with-childbirth?search=repair%20 episiotomy&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usa ge_type=default&display_rank=1. Accessed February 28, 2021.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 198: prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e87-e102.

- Jangö H, Langhoff-Roos J, Rosthøj S, et al. Long-term anal incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injury—does grade of tear matter? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:232.e1-232.e10.

- O’Boyle AL, Woodman PJ, O’Boyle JD, et al. Pelvic organ support in nulliparous pregnant and nonpregnant women: a case control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:99-102.

- Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, et al. Pelvic floor disorders after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119 (2, pt 1):233-239.

- Handa VL, Nygaard I, Kenton K, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Pelvic organ support among primiparous women in the first year after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1407-1411.

- O’Boyle AL, O’Boyle JD, Calhoun B, et al. Pelvic organ support in pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:69-72.

- Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al; POPPY Trial Collaborators. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:796-806.

- Von Bargen E, Haviland MJ, Chang OH, et al. Evaluation of postpartum pelvic floor physical therapy on obstetrical anal sphincter injury: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000849.

Pessaries for POP and SUI: Their fitting, care, and effectiveness in various disorders

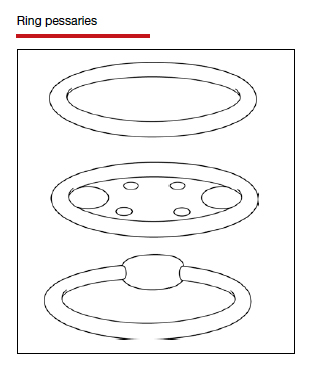

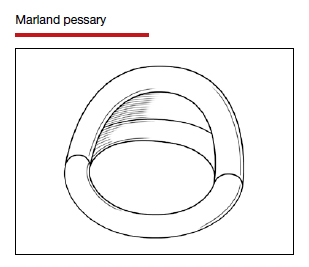

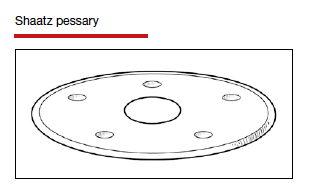

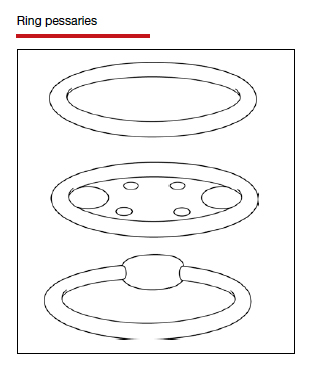

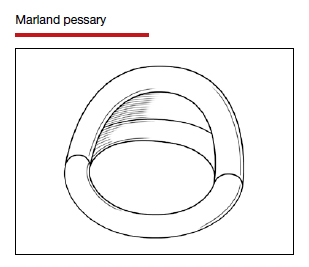

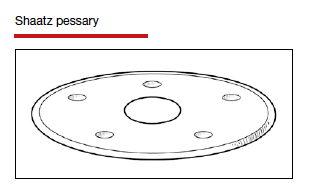

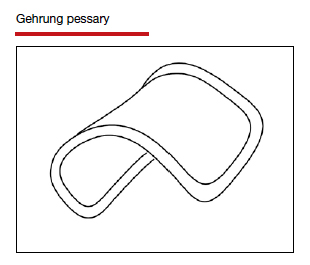

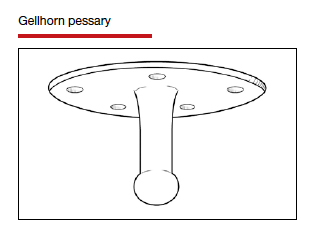

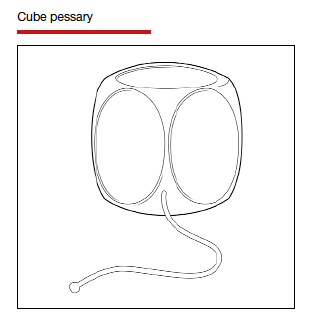

In Part 1 of this article in the December 2020 issue of OBG Management, I discussed the reasons that pessaries are an effective treatment option for many women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and provided details on the types of pessaries available.

In this article, I highlight the steps in fitting a pessary, pessary aftercare, and potential complications associated with pessary use. In addition, I discuss the effectiveness of pessary treatment for POP and SUI as well as for preterm labor prevention and defecatory disorders.

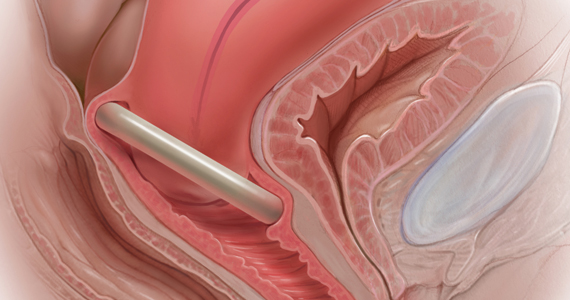

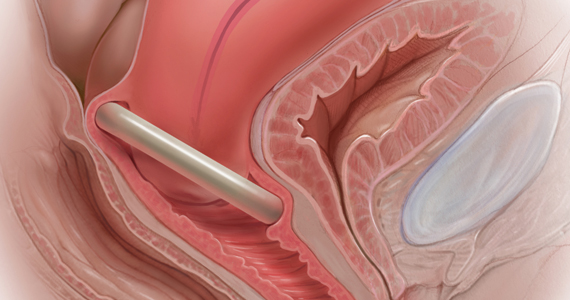

The pessary fitting process

For a given patient, the best size pessary is the smallest one that will not fall out. The only “rule” for fitting a pessary is that a woman’s internal vaginal caliber should be wider than her introitus.

When fitting a pessary, goals include that the selected pessary:

- should be comfortable for the patient to wear

- is not easily expelled

- does not interfere with urination or defecation

- does not cause vaginal irritation.

The presence or absence of a cervix or uterus does not affect pessary choice.

Most experts agree that the process for fitting the right size pessary is one of trial and error. As with fitting a contraceptive diaphragm, the clinician should perform a manual examination to estimate the integrity and width of the perineum and the depth of the vagina to roughly approximate the pessary size that might best fit. Using a set of “fitting pessaries,” a pessary of the estimated size should be placed into the vagina and the fit evaluated as to whether the device is too big, too small, or appropriate. If the pessary is easily expelled, larger sizes should be tried until the pessary remains in place or the patient is uncomfortable. Once the pessary is in place, the clinician should be able to run his or her finger around the entire pessary; if this is not possible, the pessary is too tight. In addition, the pessary should remain more than one finger breadth above the introitus when the patient is standing or bearing down.

Since many patients who require a pessary are elderly, their perineal skin and vaginal mucosa may be atrophic and fragile. Inserting a pessary can be uncomfortable and can cause abrasions or tears. Successfully fitting a pessary may require extra care under these circumstances. The following steps may help alleviate these difficulties:

- Explain the fitting process to the patient in detail.

- Employ lubrication liberally.

- Enlarge the introitus by applying gentle digital pressure on the posterior fourchette.

- Apply 2% lidocaine ointment several minutes prior to pessary fitting to help decrease patient discomfort.

- Treat the patient for several weeks with vaginal estrogen cream before attempting to fit a pessary if severe vulvovaginal atrophy is present.

Once the type and size of the pessary are selected and a pessary is inserted, evaluate the patient with the pessary in place. Assess for the following:

Discomfort. Ask the patient if she feels discomfort with the pessary in position. A patient with a properly fitting pessary should not feel that it is in place. If she does feel discomfort initially, the discomfort will only increase with time and the issue should be addressed at that time.

Expulsion. Test to make certain that the pessary is not easily expelled from the vagina. Have the patient walk, cough, squat, and even jump if possible.

Urination. Have the patient urinate with the pessary in place. This tests for her ability to void while wearing the pessary and shows whether the contraction of pelvic muscles during voiding results in expulsion of the pessary. (Experience shows that it is best to do this with a plastic “hat” over the toilet so that if the pessary is expelled, it does not drop into the bowl.)

Re-examination. After these provocative tests, examine the patient again to ensure that the pessary has not slid out of place.

Depending on whether or not your office stocks pessaries, at this point the patient is either given the correct type and size of pessary or it is ordered for her. If the former, the patient should try placing it herself; if she is unable to, the clinician should place it for her. In either event, its position should be checked. If the pessary has to be ordered, the patient must schedule an appointment to return for pessary insertion.

Whether the pessary is supplied by the office or ordered, instruct the patient on how to insert and remove the pessary, how frequently to remove it for cleansing (see below), and signs to watch for, such as vaginal bleeding, inability to void or defecate, or pelvic pain.

It is advisable to schedule a subsequent visit for 2 to 3 weeks after initial pessary placement to assess how the patient is doing and to address any issues that have developed.

Continue to: Special circumstances...

Special circumstances

It is safe for a patient with a pessary in place to undergo magnetic resonance imaging.1 Patients should be informed, however, that full body scans, such as at airports, will detect pessaries. Patients may need to obtain a physician’s note to document that the pessary is a medical device.

Finally, several factors may prevent successful pessary fitting. These include prior pelvic surgery, obesity, short vaginal length (less than 6–7 cm), and a vaginal introitus width of greater than 4 finger breadths.

Necessary pessary aftercare

Once a pessary is in place and the patient is comfortable with it, the only maintenance necessary is the pessary’s intermittent removal for cleansing and for evaluation of the vaginal mucosa for erosion and ulcerations. How frequently this should be done varies based on the type of pessary, the amount of discharge that a woman produces, whether or not an odor develops after prolonged wearing of the pessary, and whether or not the patient’s vaginal mucosa has been abraded.

The question of timing for pessary cleaning

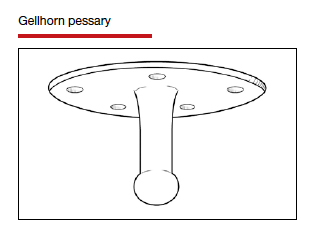

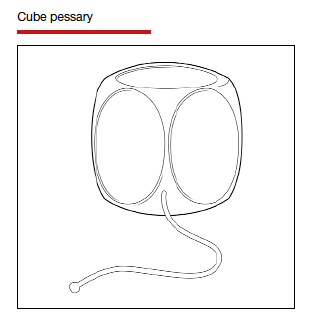

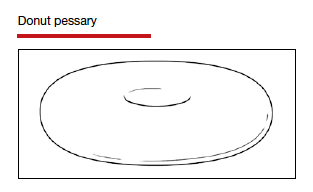

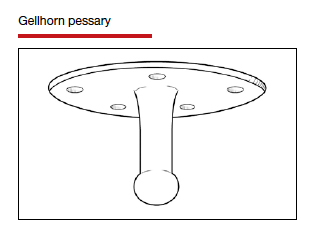

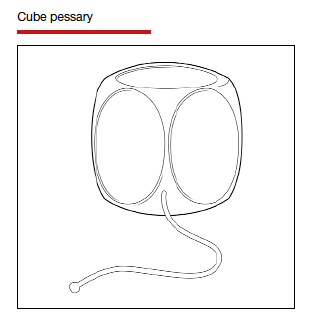

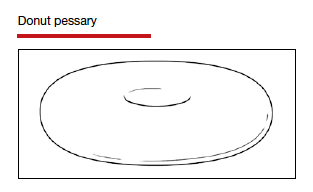

Although there are many opinions about how often pessaries should be removed and cleaned, no data in the literature support any specific interval. Pessaries that are easily removed by women themselves can be cleaned as frequently as desired, often on a weekly basis. The patient simply removes the pessary, washes it with soap and water, and reinserts it. For pessaries that are difficult to remove (such as the Gellhorn, cube, or donut) or for women who are physically unable to remove their own ring pessary, the clinician should remove and clean the pessary in the office every 3 to 6 months. It has been shown that there is no difference in complications from pessary use with either of these intervals.2

Prior to any vaginal surgical procedure, patients must be instructed to remove their pessary 10 to 14 days beforehand so that the surgeon can see the full extent of prolapse when making decisions about reconstruction and so that any vaginal mucosal erosions or abrasions have time to heal.

Office visits for follow-up care

The pessary “cleaning visit” has several goals, including to:

- see if the pessary is meeting the patient’s needs in terms of resolving symptoms of prolapse and/or restoring urinary continence

- discuss with the patient any problems she may be having, such as pelvic discomfort or pressure, difficulty voiding or defecating, excessive vaginal discharge, or vaginal odor

- check for vaginal mucosal erosion or ulceration; such vaginal lesions often can be prevented by the prophylactic use of either estrogen vaginal cream twice weekly or the continuous use of an estradiol vaginal ring in addition to the pessary

- evaluate the condition of the pessary itself and clean it with soap and water.

Continue to: Potential complications of pessary use...

Potential complications of pessary use

The most common complications experienced by pessary users are:

Odor or excessive discharge. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) occurs more frequently in women who use pessaries. The symptoms of BV can be minimized—but unfortunately not totally eliminated—by the prophylactic use of antiseptic vaginal creams or gels, such as metronidazole, clindamycin, Trimo-San (oxyquinoline sulfate and sodium lauryl sulfate), and others. Inserting the gel vaginally once a week can significantly reduce discharge and odor.3

Vaginal mucosal erosion and ulceration. These are treated by removing the pessary for 2 weeks during which time estrogen cream is applied daily or an estradiol vaginal ring is put in place. If no resolution occurs after 2 weeks, the nonhealing vaginal mucosa should be biopsied.

Pressure on the rectum or bladder. If the pessary causes significant discomfort or interferes with voiding function, then either a different size or a different type pessary should be tried

Patients may discontinue pessary use for a variety of reasons. Among these are:

- discomfort

- inadequate improvement of POP or incontinence symptoms

- expulsion of the pessary during daily activities

- the patient’s desire for surgery instead

- worsening of urine leakage

- difficulty inserting or removing the pessary

- damage to the vaginal mucosa

- pain during removal of the pessary in the office.

Pessary effectiveness for POP and SUI symptoms

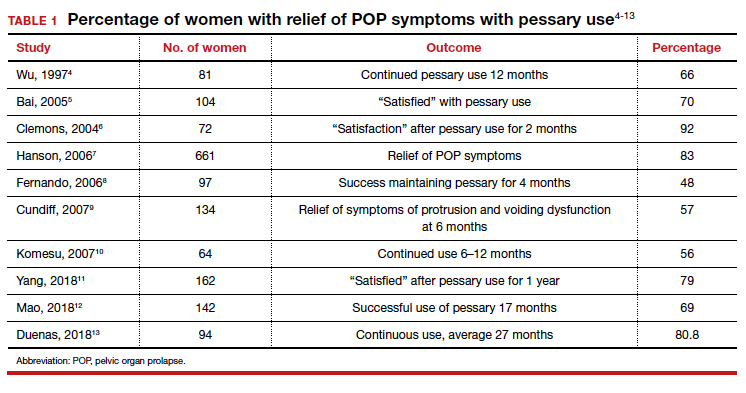

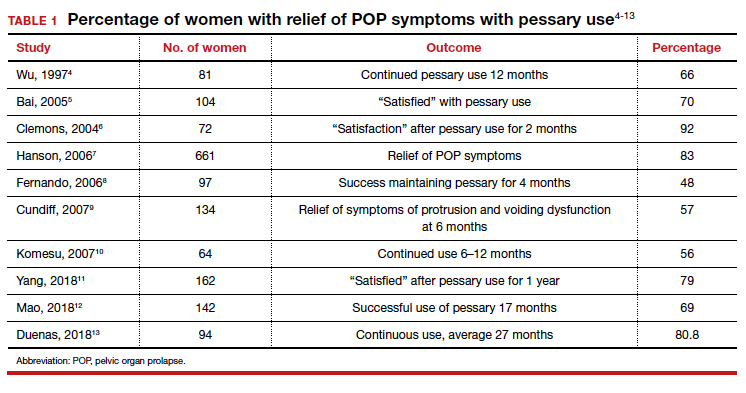

As might be expected with a device that is available in so many forms and is used to treat varied types of POP and SUI, the data concerning the success rates of pessary use vary considerably. These rates depend on the definition of success, that is, complete or partial control of prolapse and/or incontinence; which devices are being evaluated; and the nature and severity of the POP and/or SUI being treated.

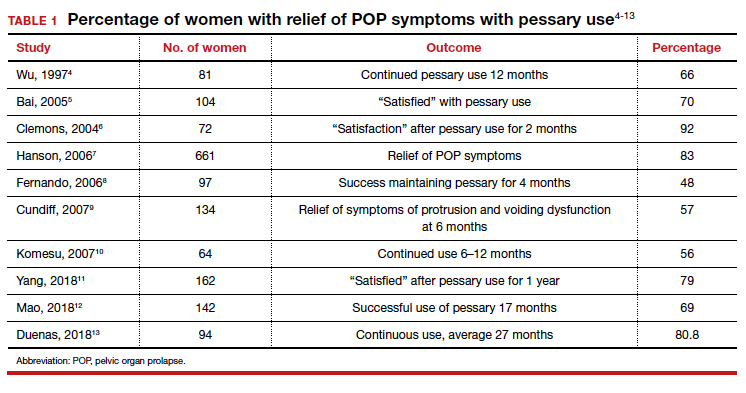

That being said, a review of the literature reveals that the rates of prolapse symptom relief vary from 48% to 92% (TABLE 1).4-13

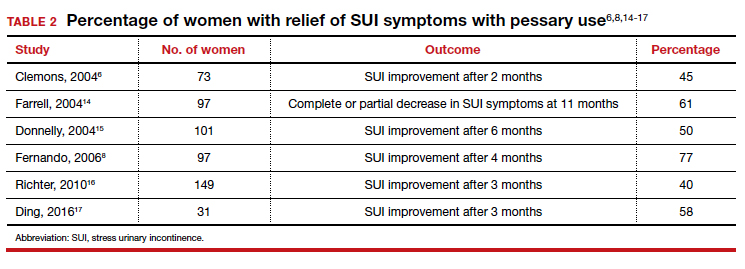

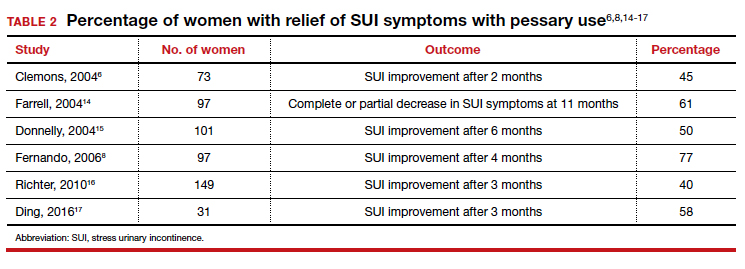

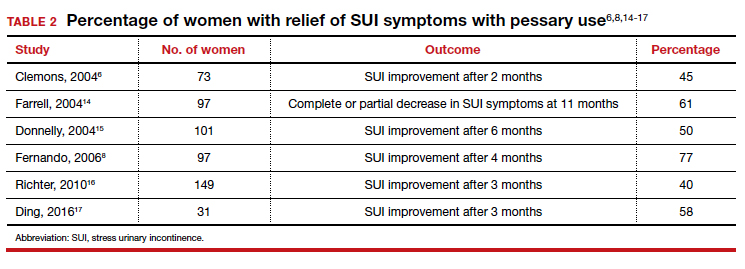

As for success in relieving symptoms of incontinence, studies show improvements in from 40% to 77% of patients (TABLE 2).6,8,14-17

In addition, some studies show a 50% improvement in bowel symptoms (urgency, obstruction, and anal incontinence) with the use of a pessary.9,18

How pessaries compare with surgery

While surgery has the advantage of being a one-time fix with a very high rate of initial success in correcting both POP and incontinence, surgery also has potential drawbacks:

- It is an invasive procedure with the discomfort and risk of complications any surgery entails.

- There is a relatively high rate of prolapse recurrence.

- It exposes the patient to the possibility of mesh erosion if mesh is employed either for POP support or incontinence treatment.

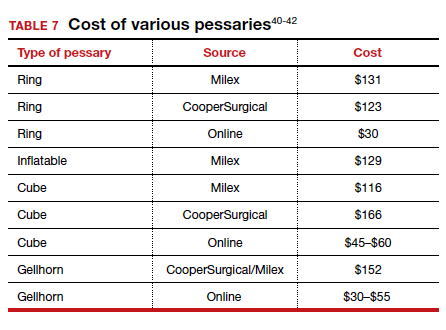

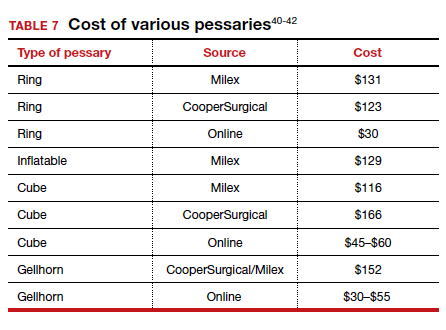

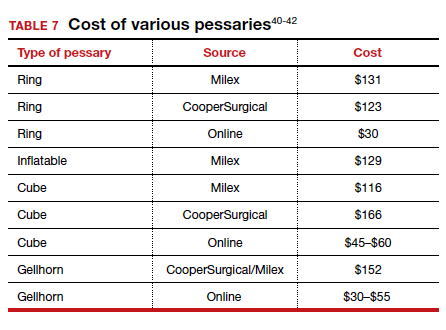

Pessaries, on the other hand, are inexpensive, nonsurgical, removable, and allow for immediate correction of symptoms. Moreover, if the pessary is tried and is found to be unsatisfactory, surgery always can be performed subsequently.

Drawbacks of pessary treatment compared with surgery include the:

- ongoing need to wear an artificial internal device

- need for intermittent pessary removal and cleansing

- inability to have sexual intercourse with certain kinds of pessaries in place

- possible accumulation of vaginal discharge and odor.

Sexual activity and pessaries

Studies by Fernando, Meriwether, and Kuhn concur that for a substantial number of pessary users who are sexually active, both frequency and satisfaction with sexual intercourse are increased.8,19,20 Kuhn further showed that desire, orgasm, and lubrication improved with the use of pessaries.20 While some types of pessaries do require removal for intercourse, Clemons reported that issues involving sexual activity are not associated with pessary discontinuation.21

Using a pessary to predict a surgical outcome

Because a pessary elevates the pelvic organs, supports the vaginal walls, and lifts the bladder and urethra into a position that simulates the results of surgical repair, trial placement of a pessary can be used as a fairly accurate predictive tool to model what pelvic support and continence status will be after a proposed surgical procedure.22,23 This is especially important because a significant number of patients with POP will have their occult stress incontinence unmasked following a reparative procedure.24 A brief pessary trial prior to surgery, therefore, can be a useful tool for both patient and surgeon.

Continue to: Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor...

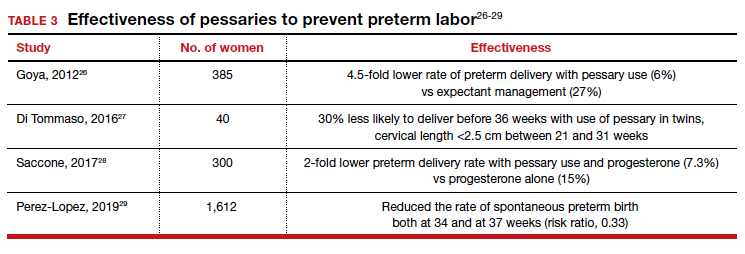

Pessaries for prevention of preterm labor

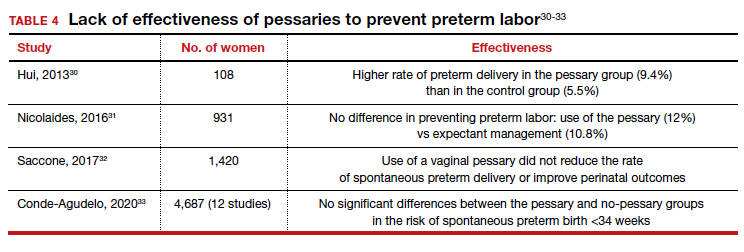

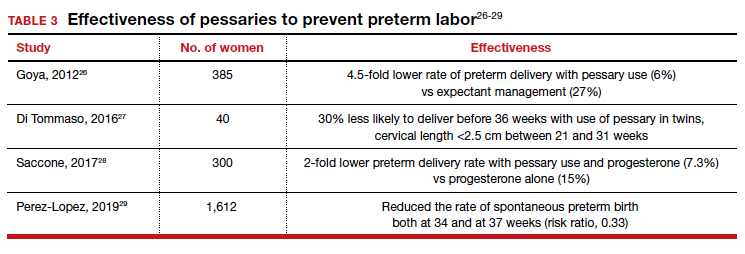

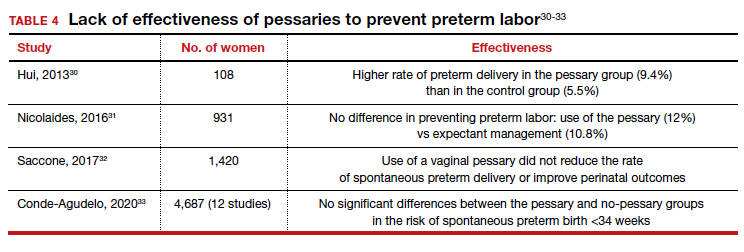

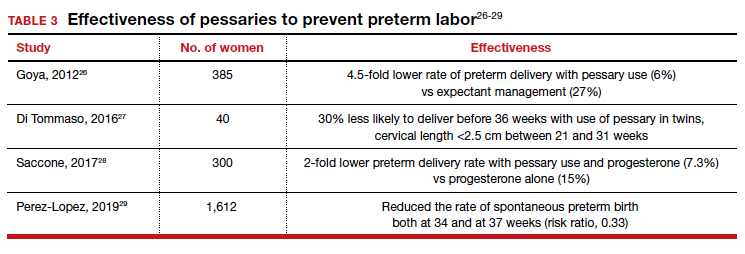

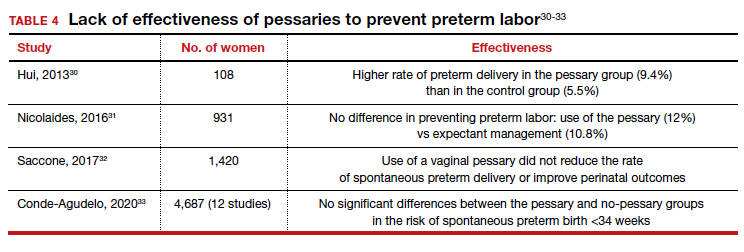

Almost 1 in 10 births in the United States occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestation.25 Obstetricians have long thought that in women at risk for preterm delivery, the use of a pessary might help reduce the pressure of the growing uterus on the cervix and thus help prevent premature cervical dilation. It also has been thought that use of a pessary would be a safer and less invasive alternative to cervical cerclage. Many studies have evaluated the use of pessaries for the prevention of preterm labor with a mixture of positive (TABLE 3)26-29 and negative results (TABLE 4).30-33

From these data, it is reasonable to conclude that:

- The final answer concerning the effectiveness or lack thereof of pessary use in preventing preterm delivery is not yet in.

- Any advantage there might be to using pessaries to prevent preterm delivery cannot be too significant if multiple studies show as many negative outcomes as positive ones.

Pessary effectiveness in defecatory disorders

Vaginal birth has the potential to create multiple anatomic injuries in the anus, lower pelvis, and perineum that can affect defecation and bowel control. Tears of the anal sphincter, whether obvious or occult, may heal incompletely or be repaired inadequately.34 Nerve innervation of the perianal and perineal areas can be interrupted or damaged by stretching, tearing, or prolonged compression. Of healthy parous adult women, 7% to 16% admit incontinence of gas or feces.35,36

In addition, when a rectocele is present, stool in the lower rectum may cause bulging of the anterior rectal wall into the vagina, preventing stool from passing out of the anus. This sometimes requires women to digitally press their posterior vaginal walls during defecation to evacuate stool successfully. The question thus arises as to whether or not pessary placement and subsequent relief of rectoceles might facilitate bowel movements and decrease or eliminate defecatory dysfunction.

As with the issue of pessary use for prevention of preterm delivery, the answer is mixed. For instance, while Brazell18 showed that there was an overall improvement in bowel symptoms in pessary users, a study by Komesu10 did not demonstrate improvement.

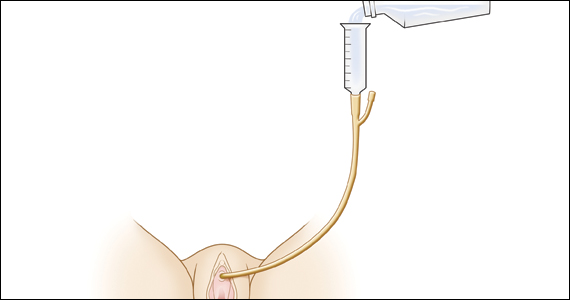

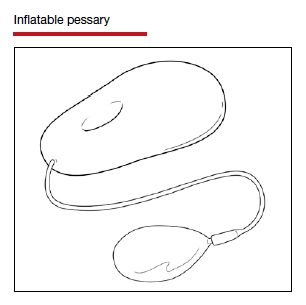

There is, however, a relatively new device specifically designed to control defecatory problems: the vaginal bowel control system (Eclipse; Pelvalon). The silicon device is placed intravaginally as one does a pessary. After insertion, it is inflated via a valve and syringe. It works by putting pressure on and reversibly closing the lower rectum, thus blocking the uncontrolled passage of stool and gas. It can be worn continuously or intermittently, but it does need to be deflated for normal bowel movements. One trial of this device demonstrated a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes with a patient satisfaction rate of 84% at 3 months.37 This device may well prove to be a valuable nonsurgical approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence. Unfortunately, the device is relatively expensive and usually is not covered by insurance as third-party payers do not consider it to be a pessary (which generally is covered).

Practice management particulars

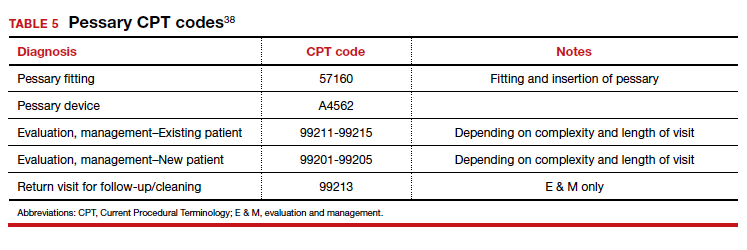

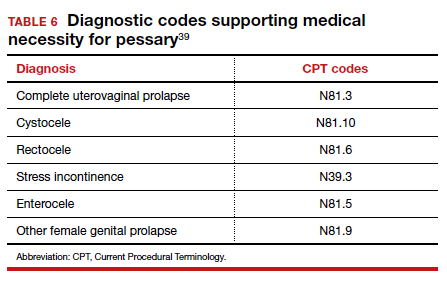

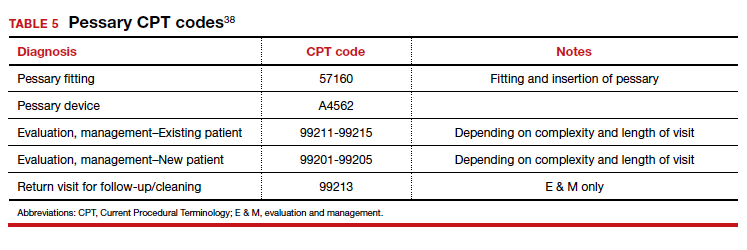

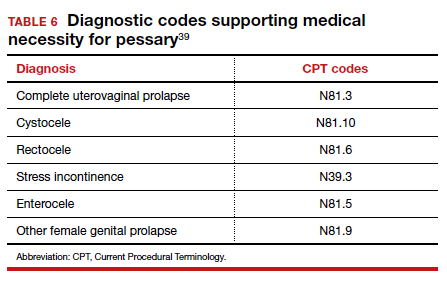

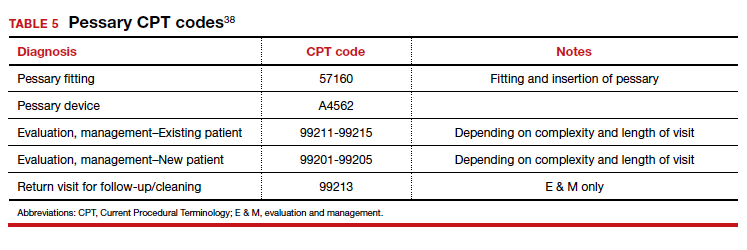

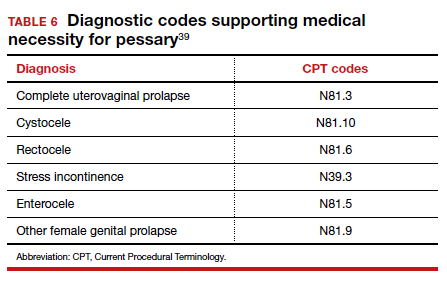

Useful information on Current Procedural Terminology codes for pessaries, diagnostic codes, and the cost of various pessaries is provided in TABLE 5,38TABLE 6,39 and TABLE 7.40-42

A contemporary device used since antiquity

Pessaries, considered “old-fashioned” by many gynecologists, are actually a very cost-effective and useful tool for the correction of POP and SUI. It behooves all who provide medical care to women to be familiar with them, to know when they might be useful, and to know how to fit and prescribe them. ●

- O’Dell K, Atnip S. Pessary care: follow up and management of complications. Urol Nurs. 2012;32:126-136, 145.

- Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:129-131.

- Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, et al. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:729.e1-9.

- Wu V, Farrell SA, Baskett TF, et al. A simplified protocol for pessary management. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:990-994.

- Bai SW, Yoon BS, Kwon JY, et al. Survey of the characteristics and satisfaction degree of the patients using a pessary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:182-186.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, et al. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1025-1029.

- Hanson LM, Schulz JA, Flood CG, et al. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17: 155-159.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, et al. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:93-99.

- Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:405.e1-405e.8.

- Komesu YM Rogers RG, Rode MA, et al. Pelvic floor symptom changes in pessary users. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197: 620.e1-6.

- Yang J, Han J, Zhu F, et al. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used inpatients with pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study of 8 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:623-629.

- Mao M, Ai F, Zhang Y, et al. Changes in the symptoms and quality of life of women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse fitted with a ring with support pessary. Maturitas. 2018;117:51-56.