User login

Hair Care Practices in Black Women With and Without Scarring Alopecia: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Bimatoprost Repigments Vitiligo Patient Skin

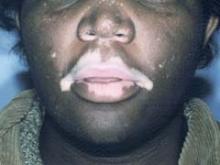

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA – Topical bimatoprost ophthalmic solution shows promise as a novel treatment for localized, stable vitiligo, a small pilot study suggests.

Patients with recalcitrant sequential or focal vitiligo, especially on the face, responded particularly well to the topical prostaglandin F2-alpha analogue in this small prospective trial with blinded outcome assessment, Dr. Tarun Narang said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Advantages of this off-label treatment include its low cost, the fact that patients can self-apply it with no requirement for photoexposure, and the minimal side effects, added Dr. Narang of Gian Sagar Medical College in Banur, India.

He reported on 10 patients with localized vitiligo who applied bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution at a dose of 1 drop per 2 cm2 of affected skin twice daily for 4 months.

Seven of 10 patients showed pronounced repigmentation beginning on average after 2 months of treatment: 3 patients had 100% repigmentation, 3 others had 75%-99% repigmentation, and 1 patient showed 50%-75% repigmentation.

Patients with a disease duration of 6 months or less had the best results. Lesions on the face and scalp regimented fastest, after just 4-6 weeks of treatment. Facial lesions responded best, as all three patients who had 100% clearing had vitiligo on the face.

During 6 months of follow-up, three patients with lesions on the trunk or extremities that initially responded to treatment relapsed, typically 2-3 months after conclusion of the 4-month treatment period. Interestingly, all five patients with focal or segmental vitiligo had either 100% repigmentation or 75%-99% improvement, and none relapsed off therapy, Dr. Narang noted.

The only treatment side effect was a transient burning sensation, mainly on the lips, reported by two patients.

Dr. Narang said that although vitiligo involves the disappearance of dermal melanocytes, the mechanisms involved are not completely understood. However, it is known that prostaglandins in the skin help regulate melanocytes.

The topical prostaglandin analogues prescribed for treatment of glaucoma cause increased melanogenesis as evidenced by their common side effects: periocular skin hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, and iris hyperpigmentation.

Ophthalmologic colleagues say these side effects are more pronounced with bimatoprost than other topical prostaglandin analogues, which is why Dr. Narang said he decided to conduct this first-ever study of the drug as a treatment for vitiligo. The long-term effects of daily bimatoprost for vitiligo will require further study, he stressed.

Dr. Narang declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA – Topical bimatoprost ophthalmic solution shows promise as a novel treatment for localized, stable vitiligo, a small pilot study suggests.

Patients with recalcitrant sequential or focal vitiligo, especially on the face, responded particularly well to the topical prostaglandin F2-alpha analogue in this small prospective trial with blinded outcome assessment, Dr. Tarun Narang said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Advantages of this off-label treatment include its low cost, the fact that patients can self-apply it with no requirement for photoexposure, and the minimal side effects, added Dr. Narang of Gian Sagar Medical College in Banur, India.

He reported on 10 patients with localized vitiligo who applied bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution at a dose of 1 drop per 2 cm2 of affected skin twice daily for 4 months.

Seven of 10 patients showed pronounced repigmentation beginning on average after 2 months of treatment: 3 patients had 100% repigmentation, 3 others had 75%-99% repigmentation, and 1 patient showed 50%-75% repigmentation.

Patients with a disease duration of 6 months or less had the best results. Lesions on the face and scalp regimented fastest, after just 4-6 weeks of treatment. Facial lesions responded best, as all three patients who had 100% clearing had vitiligo on the face.

During 6 months of follow-up, three patients with lesions on the trunk or extremities that initially responded to treatment relapsed, typically 2-3 months after conclusion of the 4-month treatment period. Interestingly, all five patients with focal or segmental vitiligo had either 100% repigmentation or 75%-99% improvement, and none relapsed off therapy, Dr. Narang noted.

The only treatment side effect was a transient burning sensation, mainly on the lips, reported by two patients.

Dr. Narang said that although vitiligo involves the disappearance of dermal melanocytes, the mechanisms involved are not completely understood. However, it is known that prostaglandins in the skin help regulate melanocytes.

The topical prostaglandin analogues prescribed for treatment of glaucoma cause increased melanogenesis as evidenced by their common side effects: periocular skin hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, and iris hyperpigmentation.

Ophthalmologic colleagues say these side effects are more pronounced with bimatoprost than other topical prostaglandin analogues, which is why Dr. Narang said he decided to conduct this first-ever study of the drug as a treatment for vitiligo. The long-term effects of daily bimatoprost for vitiligo will require further study, he stressed.

Dr. Narang declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

SEOUL, SOUTH KOREA – Topical bimatoprost ophthalmic solution shows promise as a novel treatment for localized, stable vitiligo, a small pilot study suggests.

Patients with recalcitrant sequential or focal vitiligo, especially on the face, responded particularly well to the topical prostaglandin F2-alpha analogue in this small prospective trial with blinded outcome assessment, Dr. Tarun Narang said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Advantages of this off-label treatment include its low cost, the fact that patients can self-apply it with no requirement for photoexposure, and the minimal side effects, added Dr. Narang of Gian Sagar Medical College in Banur, India.

He reported on 10 patients with localized vitiligo who applied bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution at a dose of 1 drop per 2 cm2 of affected skin twice daily for 4 months.

Seven of 10 patients showed pronounced repigmentation beginning on average after 2 months of treatment: 3 patients had 100% repigmentation, 3 others had 75%-99% repigmentation, and 1 patient showed 50%-75% repigmentation.

Patients with a disease duration of 6 months or less had the best results. Lesions on the face and scalp regimented fastest, after just 4-6 weeks of treatment. Facial lesions responded best, as all three patients who had 100% clearing had vitiligo on the face.

During 6 months of follow-up, three patients with lesions on the trunk or extremities that initially responded to treatment relapsed, typically 2-3 months after conclusion of the 4-month treatment period. Interestingly, all five patients with focal or segmental vitiligo had either 100% repigmentation or 75%-99% improvement, and none relapsed off therapy, Dr. Narang noted.

The only treatment side effect was a transient burning sensation, mainly on the lips, reported by two patients.

Dr. Narang said that although vitiligo involves the disappearance of dermal melanocytes, the mechanisms involved are not completely understood. However, it is known that prostaglandins in the skin help regulate melanocytes.

The topical prostaglandin analogues prescribed for treatment of glaucoma cause increased melanogenesis as evidenced by their common side effects: periocular skin hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, and iris hyperpigmentation.

Ophthalmologic colleagues say these side effects are more pronounced with bimatoprost than other topical prostaglandin analogues, which is why Dr. Narang said he decided to conduct this first-ever study of the drug as a treatment for vitiligo. The long-term effects of daily bimatoprost for vitiligo will require further study, he stressed.

Dr. Narang declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE WORLD CONGRESS OF DERMATOLOGY

Major Finding: Seven of 10 vitiligo patients showed pronounced repigmentation beginning on average after 2 months of treatment: 3 patients had 100% repigmentation, 3 patients had 75%-99% repigmentation, and 1 patient showed 50%-75% repigmentation.

Data Source: A small pilot study to evaluate an off-label use of topical bimatoprost ophthalmic solution.

Disclosures: Dr. Narang declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

Healthy People Don't Need Vitamin D Screen, Guidelines Say

BOSTON – Healthy individuals do not need to be screened for vitamin D deficiency, according to guidelines released today by the Endocrine Society.

"We do not recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. That's an important message. So we're recommending screening for those at risk for vitamin D deficiency – those who are obese, African Americans, pregnant and lactating women, patients with malabsorption syndromes, and a whole list that we have provided in the guidelines," lead author Dr. Michael F. Holick said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Holick headed a task force appointed by the clinical guidelines subcommittee of the Endocrine Society to formulate evidence-based recommendations on vitamin D deficiency. The subcommittee deemed vitamin D deficiency a priority area in need of practice guidelines.

The task force noted that most individuals do not get adequate vitamin D for a number of reasons. In particular, "there needs to be an appreciation that unprotected sun exposure is the major source of vitamin D for both children and adults and that in the absence of sun exposure it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain an adequate amount of vitamin D from dietary sources without supplementation to satisfy the body’s requirement. Concerns about melanoma and other types of skin cancer necessitate avoidance of excessive exposure to midday sun," they wrote.

The task force recommended that those at risk for vitamin D deficiency be screened by measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels using a reliable assay. Causes of vitamin D deficiency include obesity, fat malabsorption syndromes, bariatric surgery, nephrotic syndrome, a wide range of medications (anticonvulsants and anti–HIV/AIDS drugs), chronic granuloma-forming disorders, some lymphomas, and primary hyperthyroidism.

The guidelines were released at the meeting and will be published in the July issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385).

The guidelines provide long-awaited recommendations on vitamin D intake and the diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Physicians have struggled for years to delineate how much vitamin D is necessary for different clinical groups, how to measure it, and how best to supplement deficiencies.

The task force commissioned the conduct of two systematic reviews of the literature to inform its key recommendations and followed the approach recommended by GRADE, an international group with expertise in development and implementation of evidence-based guidelines.

"All available evidence suggests that children and adults should maintain a blood level of 25(OH)D above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets and osteomalacia, respectively. However, to maximize vitamin D's effect on calcium, bone, and muscle metabolism, the 25(OH)D blood level should be above 30 ng/mL," the group wrote.

In the new guidelines, vitamin D deficiency is defined as a 25(OH)D concentration less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). The task force suggests:

– Infants and children aged 0-1 year require at least 400 IU/day (IU = 25 ng) of vitamin D to maximize bone health.

– Children 1 year and older require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 19-50 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 50-70 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults 70 years and older require 800 IU/day.

– Pregnant and lactating women require at least 600 IU/day.

The task force also recommends that obese children and adults and children and adults on certain medications (anticonvulsant medications, glucocorticoids, antifungals such as ketoconazole, and medications for AIDS) be given at least 2-3 times more vitamin D for their age group to satisfy their bodies' vitamin D requirements.

Either vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 can be used for the treatment and prevention of vitamin D deficiency. The group recommends that adults who are vitamin D deficient be treated with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 once a week for eight weeks or its equivalent of 6,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 daily to achieve a blood level of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL. This should be followed by maintenance therapy of 1,500-2,000 IU/day.

The task force also recommends vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention. "We know that there is sufficient evidence to give vitamin D for fall prevention. It's well documented that vitamin D is very important for muscle strength," said Dr. Holick, professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at Boston University.

However, the group does not recommend prescribing vitamin D supplementation beyond recommended daily needs for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease or death or improving quality of life, because there is insufficient evidence.

The guidelines are cosponsored by the Canadian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism and the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

All but one of the authors reported having significant financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, medical organizations, and/or food industry groups.

BOSTON – Healthy individuals do not need to be screened for vitamin D deficiency, according to guidelines released today by the Endocrine Society.

"We do not recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. That's an important message. So we're recommending screening for those at risk for vitamin D deficiency – those who are obese, African Americans, pregnant and lactating women, patients with malabsorption syndromes, and a whole list that we have provided in the guidelines," lead author Dr. Michael F. Holick said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Holick headed a task force appointed by the clinical guidelines subcommittee of the Endocrine Society to formulate evidence-based recommendations on vitamin D deficiency. The subcommittee deemed vitamin D deficiency a priority area in need of practice guidelines.

The task force noted that most individuals do not get adequate vitamin D for a number of reasons. In particular, "there needs to be an appreciation that unprotected sun exposure is the major source of vitamin D for both children and adults and that in the absence of sun exposure it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain an adequate amount of vitamin D from dietary sources without supplementation to satisfy the body’s requirement. Concerns about melanoma and other types of skin cancer necessitate avoidance of excessive exposure to midday sun," they wrote.

The task force recommended that those at risk for vitamin D deficiency be screened by measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels using a reliable assay. Causes of vitamin D deficiency include obesity, fat malabsorption syndromes, bariatric surgery, nephrotic syndrome, a wide range of medications (anticonvulsants and anti–HIV/AIDS drugs), chronic granuloma-forming disorders, some lymphomas, and primary hyperthyroidism.

The guidelines were released at the meeting and will be published in the July issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385).

The guidelines provide long-awaited recommendations on vitamin D intake and the diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Physicians have struggled for years to delineate how much vitamin D is necessary for different clinical groups, how to measure it, and how best to supplement deficiencies.

The task force commissioned the conduct of two systematic reviews of the literature to inform its key recommendations and followed the approach recommended by GRADE, an international group with expertise in development and implementation of evidence-based guidelines.

"All available evidence suggests that children and adults should maintain a blood level of 25(OH)D above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets and osteomalacia, respectively. However, to maximize vitamin D's effect on calcium, bone, and muscle metabolism, the 25(OH)D blood level should be above 30 ng/mL," the group wrote.

In the new guidelines, vitamin D deficiency is defined as a 25(OH)D concentration less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). The task force suggests:

– Infants and children aged 0-1 year require at least 400 IU/day (IU = 25 ng) of vitamin D to maximize bone health.

– Children 1 year and older require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 19-50 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 50-70 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults 70 years and older require 800 IU/day.

– Pregnant and lactating women require at least 600 IU/day.

The task force also recommends that obese children and adults and children and adults on certain medications (anticonvulsant medications, glucocorticoids, antifungals such as ketoconazole, and medications for AIDS) be given at least 2-3 times more vitamin D for their age group to satisfy their bodies' vitamin D requirements.

Either vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 can be used for the treatment and prevention of vitamin D deficiency. The group recommends that adults who are vitamin D deficient be treated with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 once a week for eight weeks or its equivalent of 6,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 daily to achieve a blood level of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL. This should be followed by maintenance therapy of 1,500-2,000 IU/day.

The task force also recommends vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention. "We know that there is sufficient evidence to give vitamin D for fall prevention. It's well documented that vitamin D is very important for muscle strength," said Dr. Holick, professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at Boston University.

However, the group does not recommend prescribing vitamin D supplementation beyond recommended daily needs for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease or death or improving quality of life, because there is insufficient evidence.

The guidelines are cosponsored by the Canadian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism and the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

All but one of the authors reported having significant financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, medical organizations, and/or food industry groups.

BOSTON – Healthy individuals do not need to be screened for vitamin D deficiency, according to guidelines released today by the Endocrine Society.

"We do not recommend screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. That's an important message. So we're recommending screening for those at risk for vitamin D deficiency – those who are obese, African Americans, pregnant and lactating women, patients with malabsorption syndromes, and a whole list that we have provided in the guidelines," lead author Dr. Michael F. Holick said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Holick headed a task force appointed by the clinical guidelines subcommittee of the Endocrine Society to formulate evidence-based recommendations on vitamin D deficiency. The subcommittee deemed vitamin D deficiency a priority area in need of practice guidelines.

The task force noted that most individuals do not get adequate vitamin D for a number of reasons. In particular, "there needs to be an appreciation that unprotected sun exposure is the major source of vitamin D for both children and adults and that in the absence of sun exposure it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain an adequate amount of vitamin D from dietary sources without supplementation to satisfy the body’s requirement. Concerns about melanoma and other types of skin cancer necessitate avoidance of excessive exposure to midday sun," they wrote.

The task force recommended that those at risk for vitamin D deficiency be screened by measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels using a reliable assay. Causes of vitamin D deficiency include obesity, fat malabsorption syndromes, bariatric surgery, nephrotic syndrome, a wide range of medications (anticonvulsants and anti–HIV/AIDS drugs), chronic granuloma-forming disorders, some lymphomas, and primary hyperthyroidism.

The guidelines were released at the meeting and will be published in the July issue of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385).

The guidelines provide long-awaited recommendations on vitamin D intake and the diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Physicians have struggled for years to delineate how much vitamin D is necessary for different clinical groups, how to measure it, and how best to supplement deficiencies.

The task force commissioned the conduct of two systematic reviews of the literature to inform its key recommendations and followed the approach recommended by GRADE, an international group with expertise in development and implementation of evidence-based guidelines.

"All available evidence suggests that children and adults should maintain a blood level of 25(OH)D above 20 ng/mL to prevent rickets and osteomalacia, respectively. However, to maximize vitamin D's effect on calcium, bone, and muscle metabolism, the 25(OH)D blood level should be above 30 ng/mL," the group wrote.

In the new guidelines, vitamin D deficiency is defined as a 25(OH)D concentration less than 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L). The task force suggests:

– Infants and children aged 0-1 year require at least 400 IU/day (IU = 25 ng) of vitamin D to maximize bone health.

– Children 1 year and older require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 19-50 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults aged 50-70 years require at least 600 IU/day.

– Adults 70 years and older require 800 IU/day.

– Pregnant and lactating women require at least 600 IU/day.

The task force also recommends that obese children and adults and children and adults on certain medications (anticonvulsant medications, glucocorticoids, antifungals such as ketoconazole, and medications for AIDS) be given at least 2-3 times more vitamin D for their age group to satisfy their bodies' vitamin D requirements.

Either vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 can be used for the treatment and prevention of vitamin D deficiency. The group recommends that adults who are vitamin D deficient be treated with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 once a week for eight weeks or its equivalent of 6,000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 daily to achieve a blood level of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL. This should be followed by maintenance therapy of 1,500-2,000 IU/day.

The task force also recommends vitamin D supplementation for fall prevention. "We know that there is sufficient evidence to give vitamin D for fall prevention. It's well documented that vitamin D is very important for muscle strength," said Dr. Holick, professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at Boston University.

However, the group does not recommend prescribing vitamin D supplementation beyond recommended daily needs for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease or death or improving quality of life, because there is insufficient evidence.

The guidelines are cosponsored by the Canadian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism and the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

All but one of the authors reported having significant financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, medical organizations, and/or food industry groups.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ENDOCRINE SOCIETY

Prescription Versus Over-the-counter Moisturizers: Unraveling the Mystery

Skin of Color: Rosacea

While often considered a problem in white skin, rosacea is also a common concern in skin of color patients.

The clinical signs of rosacea are often hard to diagnose in Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, and are often not associated with clinical signs and symptoms of flushing or telangiectasias. Trigger factors associated with rosacea flares – hot beverages, spicy foods, caffeine, alcoholic drinks, heat, and exercise – are often completely absent in skin of color.

Rosacea occurs mainly on the central malar cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose. Erythema and red/brown papules are common and are often confused with acne. As the condition progresses, the skin becomes persistently red and can feel uneven or even thicker. Hyper or hypopigmentation may develop in areas with inflammation. Perioral or periorficial papules, a form of rosacea commonly seen in skin of color, is also often misdiagnosed.

It has been my experience that rosacea in skin of color is often refractory to traditional topical medications and patients will often need a short course of oral antibiotics. Sulfur/sodium sulfacetamide topicals, in addition to azelaic acid, are a great adjunct to oral treatment. Topical steroids may initially improve symptoms, but will actually make the disease progress when the steroids are stopped, so they should be avoided. Strict photo protection should be encouraged.

For years, the cause of rosacea was unknown. However a team of researchers, led by Dr. Richard L. Gallo, chief of dermatology and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego, found that overproduction of two interactive inflammatory proteins results in excessive levels of a third protein that cause rosacea symptoms. His team found skin antimicrobial peptides, cathelicidins, were altered and overproduced in patients with rosacea (Nat. Med. 2007;13:975-80).

Approximately 14 million people in the United States have rosacea. Early diagnosis and management with combination oral and topical medications are effective at controlling this highly prevalent yet often misdiagnosed disease. Future research into the underlying cause of rosacea will offer targeted therapies aimed at the abnormally processed antimicrobial peptides present in the skin of rosacea patients.

While often considered a problem in white skin, rosacea is also a common concern in skin of color patients.

The clinical signs of rosacea are often hard to diagnose in Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, and are often not associated with clinical signs and symptoms of flushing or telangiectasias. Trigger factors associated with rosacea flares – hot beverages, spicy foods, caffeine, alcoholic drinks, heat, and exercise – are often completely absent in skin of color.

Rosacea occurs mainly on the central malar cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose. Erythema and red/brown papules are common and are often confused with acne. As the condition progresses, the skin becomes persistently red and can feel uneven or even thicker. Hyper or hypopigmentation may develop in areas with inflammation. Perioral or periorficial papules, a form of rosacea commonly seen in skin of color, is also often misdiagnosed.

It has been my experience that rosacea in skin of color is often refractory to traditional topical medications and patients will often need a short course of oral antibiotics. Sulfur/sodium sulfacetamide topicals, in addition to azelaic acid, are a great adjunct to oral treatment. Topical steroids may initially improve symptoms, but will actually make the disease progress when the steroids are stopped, so they should be avoided. Strict photo protection should be encouraged.

For years, the cause of rosacea was unknown. However a team of researchers, led by Dr. Richard L. Gallo, chief of dermatology and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego, found that overproduction of two interactive inflammatory proteins results in excessive levels of a third protein that cause rosacea symptoms. His team found skin antimicrobial peptides, cathelicidins, were altered and overproduced in patients with rosacea (Nat. Med. 2007;13:975-80).

Approximately 14 million people in the United States have rosacea. Early diagnosis and management with combination oral and topical medications are effective at controlling this highly prevalent yet often misdiagnosed disease. Future research into the underlying cause of rosacea will offer targeted therapies aimed at the abnormally processed antimicrobial peptides present in the skin of rosacea patients.

While often considered a problem in white skin, rosacea is also a common concern in skin of color patients.

The clinical signs of rosacea are often hard to diagnose in Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, and are often not associated with clinical signs and symptoms of flushing or telangiectasias. Trigger factors associated with rosacea flares – hot beverages, spicy foods, caffeine, alcoholic drinks, heat, and exercise – are often completely absent in skin of color.

Rosacea occurs mainly on the central malar cheeks, forehead, chin, and nose. Erythema and red/brown papules are common and are often confused with acne. As the condition progresses, the skin becomes persistently red and can feel uneven or even thicker. Hyper or hypopigmentation may develop in areas with inflammation. Perioral or periorficial papules, a form of rosacea commonly seen in skin of color, is also often misdiagnosed.

It has been my experience that rosacea in skin of color is often refractory to traditional topical medications and patients will often need a short course of oral antibiotics. Sulfur/sodium sulfacetamide topicals, in addition to azelaic acid, are a great adjunct to oral treatment. Topical steroids may initially improve symptoms, but will actually make the disease progress when the steroids are stopped, so they should be avoided. Strict photo protection should be encouraged.

For years, the cause of rosacea was unknown. However a team of researchers, led by Dr. Richard L. Gallo, chief of dermatology and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Diego, found that overproduction of two interactive inflammatory proteins results in excessive levels of a third protein that cause rosacea symptoms. His team found skin antimicrobial peptides, cathelicidins, were altered and overproduced in patients with rosacea (Nat. Med. 2007;13:975-80).

Approximately 14 million people in the United States have rosacea. Early diagnosis and management with combination oral and topical medications are effective at controlling this highly prevalent yet often misdiagnosed disease. Future research into the underlying cause of rosacea will offer targeted therapies aimed at the abnormally processed antimicrobial peptides present in the skin of rosacea patients.

The Field Effect [editorial]

Lignin Peroxidase

Lignin peroxidase, a novel skin-lightening active agent that is derived from a fungus, is being studied with some interest and is being developed as an ingredient in products to treat pigmentation disorders.

Melanin, the dark pigment in the skin, is produced in the basal layer of the epidermis by melanocytes. Melanocytes make melanin, which is packaged into melanosomes and then transferred to the epidermal cells (keratinocytes). Accumulation of melanin in the epidermis is the main cause of pigmentation disorders, which are observed in all demographic groups but most commonly in people with darker skin types.

Excessive sun exposure in dark and light skin types can lead to unwanted accumulation of pigment (known as solar lentigo) in the skin. Pigmentation disorders are notoriously difficult to treat. Melanin is a very durable compound, and researchers have been largely unsuccessful in finding ways to break down melanin to reduce unwanted skin pigment. The existing topical treatments for skin lightening focus on the prevention of melanin formation by blocking tyrosinase and inhibiting its biosynthesis; by preventing the stimulation of melanocytes by UVA: or by blocking the transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes via the PAR-2 receptor.

Alternative to Hydroquinone

Historically, the most effective treatments for skin lightening have contained hydroquinone. However, hydroquinone has become controversial, and related safety concerns have prompted research into alternative agents to treat skin pigmentation disorders. In addition, the skin develops tachyphylaxis to hydroquinone requiring 1-month "holidays" in order to maintain effectiveness, and a subset of people may develop contact allergy to hydroquinone. Many other compounds have been studied for the treatment of pigmentation disorders, including retinoids, mequinol, azelaic acid, arbutin, kojic acid, aloesin, licorice extract, ascorbic acid, soy proteins, N-acetyl glucosamine, and most recently, lignin peroxidase.

The enzyme lignin peroxidase (LIP) was first identified in 1984 (Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;234:353-62), and has been researched for many years as a potential agent to break down lignin to whiten wood pulp in paper production. It was later found to break down eumelanin, which has a chemical structure similar to lignin. The development of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening agent resulted from these discoveries (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Patent Application 20060051305). This novel skin-lightening active ingredient is produced extracellularly during submerged fermentation of the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium 3 (Biotechnol. Bioproc. E. 2004;9:153-68) and then purified from the fermented liquid medium (Lonza of Switzerland).The LIP enzyme (trademarked as Melanozyme) identifies eumelanin in the epidermis and specifically breaks down the pigment without affecting melanin biosynthesis or blocking tyrosinase. Although there are other types of lignin peroxidase enzymes, at this point, Melanozyme is the only one that has been developed and proved to be effective for skin lightening. Melanozyme is a glycoprotein active at pH 2-4.5 and inactive above that pH level. (The normal pH of skin is around 5.5, with slight variations between 5.0 and 6.5.)

Product Based on Lignin Peroxidase

Melanozyme is currently proprietary and is available only in a new skin-lightening product known on the market as Elure The Elure products are presented in a two-sided dispenser with one side containing the Melanozyme component and the other side an activator. Melanozyme alone has little ability to lighten skin, and first needs to be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (0.012% in the activator) to enter an "activated state." The activator, which contains a small amount of hydrogen peroxide, is applied to the surface of the skin after the Melanozyme.

When applied to skin, the products that contain the Melanozyme and the activator have to be slightly acidic and buffered in order for the enzyme to perform. In addition, the enzyme is required to be first oxidized by H2O2, and then reduced by a substrate molecule (for example, veratryl alcohol) before the melanin is oxidized. After application of Elure lotion or cream, the skin pH is temporarily reduced to 3.5 but subsequently increases to its normal level of around 5.5. As the skin surface returns to the normal pH level, the enzyme is inactivated. It becomes a simple glycoprotein and is hydrolyzed in the skin by the naturally present proteases and other glycosidases into amino acids.

The safety of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening active ingredient has been demonstrated in preclinical studies (data on file at Rakuto Bio Technologies Ltd., 5 Carmel Street, P.O. Box 528, New Industrial Park, Yokneam 20692 Israel) with doses that are 17,000 times the recommended dose without prompting any side effects. LIP is nonmutagenic and nonirritating to eyes. The potential for skin irritation is very low, and in studies of 50 subjects each, there were no reports of skin irritation during acute sensitivity or cumulative sensitivity, or when used in sensitized skin.

Conclusion

Three open-label clinical trials and one double-blind, split-face controlled study (Rakuto Bio Technologies) in subjects with Fitzpatrick skin types II-IV have confirmed the tolerability of Elure. In all clinical studies conducted with Elure, significant improvement in tone, evenness, and dyspigmentation were achieved in most subjects within 1 month of use. Elure has been shown to be better tolerated and more effective than 2% hydroquinone. However, more studies are needed to compare the product against stronger concentrations of hydroquinone and other existing treatments, as well as to demonstrate its effectiveness in the treatment of other pigmentary conditions in a broader range of patients. The use of Elure in a combination skin care regimen with hydroquinone and glycolic acid has not been studied, but there is no reason to believe that these products would be incompatible. In fact, a glycolic cleanser that lowers the pH of the skin prior to application could theoretically enhance the efficacy of the product.

Dr. Baumann is on the advisory board of Syneron, the manufacturer of Elure.

Lignin peroxidase, a novel skin-lightening active agent that is derived from a fungus, is being studied with some interest and is being developed as an ingredient in products to treat pigmentation disorders.

Melanin, the dark pigment in the skin, is produced in the basal layer of the epidermis by melanocytes. Melanocytes make melanin, which is packaged into melanosomes and then transferred to the epidermal cells (keratinocytes). Accumulation of melanin in the epidermis is the main cause of pigmentation disorders, which are observed in all demographic groups but most commonly in people with darker skin types.

Excessive sun exposure in dark and light skin types can lead to unwanted accumulation of pigment (known as solar lentigo) in the skin. Pigmentation disorders are notoriously difficult to treat. Melanin is a very durable compound, and researchers have been largely unsuccessful in finding ways to break down melanin to reduce unwanted skin pigment. The existing topical treatments for skin lightening focus on the prevention of melanin formation by blocking tyrosinase and inhibiting its biosynthesis; by preventing the stimulation of melanocytes by UVA: or by blocking the transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes via the PAR-2 receptor.

Alternative to Hydroquinone

Historically, the most effective treatments for skin lightening have contained hydroquinone. However, hydroquinone has become controversial, and related safety concerns have prompted research into alternative agents to treat skin pigmentation disorders. In addition, the skin develops tachyphylaxis to hydroquinone requiring 1-month "holidays" in order to maintain effectiveness, and a subset of people may develop contact allergy to hydroquinone. Many other compounds have been studied for the treatment of pigmentation disorders, including retinoids, mequinol, azelaic acid, arbutin, kojic acid, aloesin, licorice extract, ascorbic acid, soy proteins, N-acetyl glucosamine, and most recently, lignin peroxidase.

The enzyme lignin peroxidase (LIP) was first identified in 1984 (Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;234:353-62), and has been researched for many years as a potential agent to break down lignin to whiten wood pulp in paper production. It was later found to break down eumelanin, which has a chemical structure similar to lignin. The development of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening agent resulted from these discoveries (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Patent Application 20060051305). This novel skin-lightening active ingredient is produced extracellularly during submerged fermentation of the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium 3 (Biotechnol. Bioproc. E. 2004;9:153-68) and then purified from the fermented liquid medium (Lonza of Switzerland).The LIP enzyme (trademarked as Melanozyme) identifies eumelanin in the epidermis and specifically breaks down the pigment without affecting melanin biosynthesis or blocking tyrosinase. Although there are other types of lignin peroxidase enzymes, at this point, Melanozyme is the only one that has been developed and proved to be effective for skin lightening. Melanozyme is a glycoprotein active at pH 2-4.5 and inactive above that pH level. (The normal pH of skin is around 5.5, with slight variations between 5.0 and 6.5.)

Product Based on Lignin Peroxidase

Melanozyme is currently proprietary and is available only in a new skin-lightening product known on the market as Elure The Elure products are presented in a two-sided dispenser with one side containing the Melanozyme component and the other side an activator. Melanozyme alone has little ability to lighten skin, and first needs to be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (0.012% in the activator) to enter an "activated state." The activator, which contains a small amount of hydrogen peroxide, is applied to the surface of the skin after the Melanozyme.

When applied to skin, the products that contain the Melanozyme and the activator have to be slightly acidic and buffered in order for the enzyme to perform. In addition, the enzyme is required to be first oxidized by H2O2, and then reduced by a substrate molecule (for example, veratryl alcohol) before the melanin is oxidized. After application of Elure lotion or cream, the skin pH is temporarily reduced to 3.5 but subsequently increases to its normal level of around 5.5. As the skin surface returns to the normal pH level, the enzyme is inactivated. It becomes a simple glycoprotein and is hydrolyzed in the skin by the naturally present proteases and other glycosidases into amino acids.

The safety of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening active ingredient has been demonstrated in preclinical studies (data on file at Rakuto Bio Technologies Ltd., 5 Carmel Street, P.O. Box 528, New Industrial Park, Yokneam 20692 Israel) with doses that are 17,000 times the recommended dose without prompting any side effects. LIP is nonmutagenic and nonirritating to eyes. The potential for skin irritation is very low, and in studies of 50 subjects each, there were no reports of skin irritation during acute sensitivity or cumulative sensitivity, or when used in sensitized skin.

Conclusion

Three open-label clinical trials and one double-blind, split-face controlled study (Rakuto Bio Technologies) in subjects with Fitzpatrick skin types II-IV have confirmed the tolerability of Elure. In all clinical studies conducted with Elure, significant improvement in tone, evenness, and dyspigmentation were achieved in most subjects within 1 month of use. Elure has been shown to be better tolerated and more effective than 2% hydroquinone. However, more studies are needed to compare the product against stronger concentrations of hydroquinone and other existing treatments, as well as to demonstrate its effectiveness in the treatment of other pigmentary conditions in a broader range of patients. The use of Elure in a combination skin care regimen with hydroquinone and glycolic acid has not been studied, but there is no reason to believe that these products would be incompatible. In fact, a glycolic cleanser that lowers the pH of the skin prior to application could theoretically enhance the efficacy of the product.

Dr. Baumann is on the advisory board of Syneron, the manufacturer of Elure.

Lignin peroxidase, a novel skin-lightening active agent that is derived from a fungus, is being studied with some interest and is being developed as an ingredient in products to treat pigmentation disorders.

Melanin, the dark pigment in the skin, is produced in the basal layer of the epidermis by melanocytes. Melanocytes make melanin, which is packaged into melanosomes and then transferred to the epidermal cells (keratinocytes). Accumulation of melanin in the epidermis is the main cause of pigmentation disorders, which are observed in all demographic groups but most commonly in people with darker skin types.

Excessive sun exposure in dark and light skin types can lead to unwanted accumulation of pigment (known as solar lentigo) in the skin. Pigmentation disorders are notoriously difficult to treat. Melanin is a very durable compound, and researchers have been largely unsuccessful in finding ways to break down melanin to reduce unwanted skin pigment. The existing topical treatments for skin lightening focus on the prevention of melanin formation by blocking tyrosinase and inhibiting its biosynthesis; by preventing the stimulation of melanocytes by UVA: or by blocking the transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes via the PAR-2 receptor.

Alternative to Hydroquinone

Historically, the most effective treatments for skin lightening have contained hydroquinone. However, hydroquinone has become controversial, and related safety concerns have prompted research into alternative agents to treat skin pigmentation disorders. In addition, the skin develops tachyphylaxis to hydroquinone requiring 1-month "holidays" in order to maintain effectiveness, and a subset of people may develop contact allergy to hydroquinone. Many other compounds have been studied for the treatment of pigmentation disorders, including retinoids, mequinol, azelaic acid, arbutin, kojic acid, aloesin, licorice extract, ascorbic acid, soy proteins, N-acetyl glucosamine, and most recently, lignin peroxidase.

The enzyme lignin peroxidase (LIP) was first identified in 1984 (Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;234:353-62), and has been researched for many years as a potential agent to break down lignin to whiten wood pulp in paper production. It was later found to break down eumelanin, which has a chemical structure similar to lignin. The development of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening agent resulted from these discoveries (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Patent Application 20060051305). This novel skin-lightening active ingredient is produced extracellularly during submerged fermentation of the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium 3 (Biotechnol. Bioproc. E. 2004;9:153-68) and then purified from the fermented liquid medium (Lonza of Switzerland).The LIP enzyme (trademarked as Melanozyme) identifies eumelanin in the epidermis and specifically breaks down the pigment without affecting melanin biosynthesis or blocking tyrosinase. Although there are other types of lignin peroxidase enzymes, at this point, Melanozyme is the only one that has been developed and proved to be effective for skin lightening. Melanozyme is a glycoprotein active at pH 2-4.5 and inactive above that pH level. (The normal pH of skin is around 5.5, with slight variations between 5.0 and 6.5.)

Product Based on Lignin Peroxidase

Melanozyme is currently proprietary and is available only in a new skin-lightening product known on the market as Elure The Elure products are presented in a two-sided dispenser with one side containing the Melanozyme component and the other side an activator. Melanozyme alone has little ability to lighten skin, and first needs to be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (0.012% in the activator) to enter an "activated state." The activator, which contains a small amount of hydrogen peroxide, is applied to the surface of the skin after the Melanozyme.

When applied to skin, the products that contain the Melanozyme and the activator have to be slightly acidic and buffered in order for the enzyme to perform. In addition, the enzyme is required to be first oxidized by H2O2, and then reduced by a substrate molecule (for example, veratryl alcohol) before the melanin is oxidized. After application of Elure lotion or cream, the skin pH is temporarily reduced to 3.5 but subsequently increases to its normal level of around 5.5. As the skin surface returns to the normal pH level, the enzyme is inactivated. It becomes a simple glycoprotein and is hydrolyzed in the skin by the naturally present proteases and other glycosidases into amino acids.

The safety of lignin peroxidase as a skin-lightening active ingredient has been demonstrated in preclinical studies (data on file at Rakuto Bio Technologies Ltd., 5 Carmel Street, P.O. Box 528, New Industrial Park, Yokneam 20692 Israel) with doses that are 17,000 times the recommended dose without prompting any side effects. LIP is nonmutagenic and nonirritating to eyes. The potential for skin irritation is very low, and in studies of 50 subjects each, there were no reports of skin irritation during acute sensitivity or cumulative sensitivity, or when used in sensitized skin.

Conclusion

Three open-label clinical trials and one double-blind, split-face controlled study (Rakuto Bio Technologies) in subjects with Fitzpatrick skin types II-IV have confirmed the tolerability of Elure. In all clinical studies conducted with Elure, significant improvement in tone, evenness, and dyspigmentation were achieved in most subjects within 1 month of use. Elure has been shown to be better tolerated and more effective than 2% hydroquinone. However, more studies are needed to compare the product against stronger concentrations of hydroquinone and other existing treatments, as well as to demonstrate its effectiveness in the treatment of other pigmentary conditions in a broader range of patients. The use of Elure in a combination skin care regimen with hydroquinone and glycolic acid has not been studied, but there is no reason to believe that these products would be incompatible. In fact, a glycolic cleanser that lowers the pH of the skin prior to application could theoretically enhance the efficacy of the product.

Dr. Baumann is on the advisory board of Syneron, the manufacturer of Elure.

Skin of Color: Dangers of Black Market Bleaching Agents

Black market skin bleaching agents with potentially unsafe ingredients are a growing concern in some countries, according to an article published yesterday, April 11, by the Associated Press, "Skin Bleaching a Growing Problem in Jamaican Slums."

The use of these agents stems from societal and cultural beliefs that lighter skin could lead to a better way of life, particularly for those that are impoverished.

In Jamaica, for example, a "23-year-old resident of a Kingston ghetto hopes to transform her dark complexion to a cafe-au-lait-color common among Jamaica's elite and favored by many men in her neighborhood. She believes a fairer skin could be her ticket to a better life. So she spends her meager savings on cheap black-market concoctions that promise to lighten her pigment," (excerpt from AP story).

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Jamaica, but is inherent to many nations around the world. It has been documented in India, the Americas, the Middle East, the Philippines, and in some parts of Africa and Asia.

Lightening agents, such as hydroquinone, have been banned in over the counter preparations in Japan, the European Union, and Australia. OTC hydroquinone is still available in the United States in percentages of up to 2%. While hydroquinone use may lead to adverse events such as ochronosis, it is a rare event typically seen with use of much higher concentrations over longer periods of time. In my opinion, it is not low concentrations of hydroquinone, but other potentially harmful ingredients that may be found in some of the black market products that are of major concern.

"Lightening creams are not effectively regulated in Jamaica, where even roadside vendors sell tubes and plastic bags of powders and ointments from cardboard boxes stacked along sidewalks in market districts," according to the AP story. "Many of the tubes are unlabeled as to their actual ingredients," said Dr. Richard Desnoes, president of the Dermatology Association of Jamaica.

"Hardcore bleachers use illegal ointments smuggled into the Caribbean country that contain toxins like mercury, a metal that blocks production of melanin, which give skin its color, but can also be toxic," the story continued.

In addition, potent topical corticosteroids have been found in some of these products, leading to reports of atrophy, striae, and even symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome.

Black market skin bleaching agents with potentially unsafe ingredients are a growing concern in some countries, according to an article published yesterday, April 11, by the Associated Press, "Skin Bleaching a Growing Problem in Jamaican Slums."

The use of these agents stems from societal and cultural beliefs that lighter skin could lead to a better way of life, particularly for those that are impoverished.

In Jamaica, for example, a "23-year-old resident of a Kingston ghetto hopes to transform her dark complexion to a cafe-au-lait-color common among Jamaica's elite and favored by many men in her neighborhood. She believes a fairer skin could be her ticket to a better life. So she spends her meager savings on cheap black-market concoctions that promise to lighten her pigment," (excerpt from AP story).

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Jamaica, but is inherent to many nations around the world. It has been documented in India, the Americas, the Middle East, the Philippines, and in some parts of Africa and Asia.

Lightening agents, such as hydroquinone, have been banned in over the counter preparations in Japan, the European Union, and Australia. OTC hydroquinone is still available in the United States in percentages of up to 2%. While hydroquinone use may lead to adverse events such as ochronosis, it is a rare event typically seen with use of much higher concentrations over longer periods of time. In my opinion, it is not low concentrations of hydroquinone, but other potentially harmful ingredients that may be found in some of the black market products that are of major concern.

"Lightening creams are not effectively regulated in Jamaica, where even roadside vendors sell tubes and plastic bags of powders and ointments from cardboard boxes stacked along sidewalks in market districts," according to the AP story. "Many of the tubes are unlabeled as to their actual ingredients," said Dr. Richard Desnoes, president of the Dermatology Association of Jamaica.

"Hardcore bleachers use illegal ointments smuggled into the Caribbean country that contain toxins like mercury, a metal that blocks production of melanin, which give skin its color, but can also be toxic," the story continued.

In addition, potent topical corticosteroids have been found in some of these products, leading to reports of atrophy, striae, and even symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome.

Black market skin bleaching agents with potentially unsafe ingredients are a growing concern in some countries, according to an article published yesterday, April 11, by the Associated Press, "Skin Bleaching a Growing Problem in Jamaican Slums."

The use of these agents stems from societal and cultural beliefs that lighter skin could lead to a better way of life, particularly for those that are impoverished.

In Jamaica, for example, a "23-year-old resident of a Kingston ghetto hopes to transform her dark complexion to a cafe-au-lait-color common among Jamaica's elite and favored by many men in her neighborhood. She believes a fairer skin could be her ticket to a better life. So she spends her meager savings on cheap black-market concoctions that promise to lighten her pigment," (excerpt from AP story).

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Jamaica, but is inherent to many nations around the world. It has been documented in India, the Americas, the Middle East, the Philippines, and in some parts of Africa and Asia.

Lightening agents, such as hydroquinone, have been banned in over the counter preparations in Japan, the European Union, and Australia. OTC hydroquinone is still available in the United States in percentages of up to 2%. While hydroquinone use may lead to adverse events such as ochronosis, it is a rare event typically seen with use of much higher concentrations over longer periods of time. In my opinion, it is not low concentrations of hydroquinone, but other potentially harmful ingredients that may be found in some of the black market products that are of major concern.

"Lightening creams are not effectively regulated in Jamaica, where even roadside vendors sell tubes and plastic bags of powders and ointments from cardboard boxes stacked along sidewalks in market districts," according to the AP story. "Many of the tubes are unlabeled as to their actual ingredients," said Dr. Richard Desnoes, president of the Dermatology Association of Jamaica.

"Hardcore bleachers use illegal ointments smuggled into the Caribbean country that contain toxins like mercury, a metal that blocks production of melanin, which give skin its color, but can also be toxic," the story continued.

In addition, potent topical corticosteroids have been found in some of these products, leading to reports of atrophy, striae, and even symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome.

Scarring Alopecia in Black Women Still Not Understood

Despite being the most common pattern of scarring hair loss among African American women, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is still poorly understood, according to a report published online April 11 in Archives of Dermatology.

The etiology of and risk factors for the disorder have not been established. And although African American women commonly present with the condition, the exact prevalence remains unknown, said Dr. Angela Kyei and her associates at the Cleveland Clinic Institute of Dermatology and Plastic Surgery.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) – previously known as hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome – is a scarring hair loss centered on the vertex of the scalp and spreading peripherally, which is described almost exclusively in African American women. In the late 1960s it was linked to the use of hot combs, but since then almost every method of hair grooming in this population has been associated, albeit weakly, with the disorder. Few studies have examined other possible etiologies, such as immunologic, dermatologic, or genetic factors.

"Given the lack of epidemiologic data, the main goal of [our] study was to elucidate environmental as well as medical risk factors that may be associated with CCCA," the researchers wrote.

They administered questionnaires to 326 African American women attending two churches and a health fair in the Cleveland area. Sixteen of the women ended up being excluded from the analysis.

The questionnaires asked detailed information about family history of male- and female-pattern hair loss; personal medical history, including bacterial and fungal skin infections, autoimmune conditions, and hormonal dysregulation; and hair grooming methods used. The study subjects also underwent a scalp examination that included the grading of hair loss.

A total of 86 of the 310 women (28%) were judged to have central hair loss. Of these, 52 women – 17% of the total study population – had CCCA.

It appeared that hair grooming practices that cause traction, such as weaves and braids, may contribute to the development of CCCA, as women with the most severe central hair loss used these styles more frequently than did those without hair loss. "This has some clinical bearing because traction can clinically produce folliculitis of the scalp, which can cause scarring if this inflammation is prolonged," noted Dr. Kyei and her colleagues (Arch. Dermatol. 2011 April 11 [doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.66]).

After paying hundreds of dollars for such hair styling, women often maintain weaves and braids for weeks to months, so any reactive inflammation usually is prolonged, the investigators added.

However, "the relationship between chemical relaxer use and the development of CCCA continues to be murky," they noted. These products clearly weaken the hair shaft, which can cause breakage, but that does not necessarily lead to CCCA. "The fact that most African Americans use chemical relaxers in combination with braiding and other hair grooming practices makes it even more difficult to tease out a relationship," Dr. Kyei and her associates added.

It is difficult to find subjects who do not use chemical relaxers for comparison, since most African Americans begin the practice in childhood. In this study, 91% of the women reported using chemical relaxers, and began doing so at an average age of 10 years.

Nevertheless, "we feel that it is not unreasonable to assume that the scalp may absorb some of the caustic chemicals found in relaxers, which in time leads to damage of the scalp in the form of scarring," they wrote.

Although the prevalence of bacterial skin infections in these study subjects was only 11%, there was a significant elevation among women with CCCA, compared with women who did not have CCCA. The rate of acne also was elevated in affected subjects, but not to a significant degree. Thus, the researchers said that their study "demonstrates that inflammation in the form of bacterial infection and acne may also be contributing to the development of CCCA, a finding consistent with the histopathologic characteristics of this disease," which show a lymphocytic perifollicular infiltrate in its early stages.

In contrast, there was no such association with fungal infections of the scalp, ringworm, or vaginal yeast infections, which was "surprising given how prone this population is to fungal infection," they added.

"One of the most surprising findings ... was the overrepresentation of type 2 [diabetes mellitus] in those with CCCA," the authors noted. Again, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was low, at 8%, but it was significantly elevated in women with CCCA, compared with those without CCCA.

"These are important data that need further study because CCCA may be a marker of metabolic dysfunction and, when present, can prompt clinicians to do further testing for diabetes mellitus," Dr. Kyei and her colleagues wrote.

Only 9% of the study subjects had thyroid abnormalities, and three-fourths of them had no or minimal hair loss.

A history of male-pattern baldness in the maternal grandfather was found to be a risk factor for CCCA, which suggests that genetics may play a role.

Hormonal dysregulation did not appear to be associated with development of CCCA. Neither were scarring disorders, since only 6% of the subjects reported a history of keloids, and the rate was no higher in women with CCCA than in those without CCCA.

Similarly, there were relatively high prevalences of seborrheic dermatitis (24%), eczema (13%), and contact dermatitis from chemical relaxers (9%), as would be expected in an African American population. However, these conditions were unrelated to CCCA.

This study was supported in part by the North American Hair Research Society and Procter & Gamble. No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Despite being the most common pattern of scarring hair loss among African American women, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is still poorly understood, according to a report published online April 11 in Archives of Dermatology.

The etiology of and risk factors for the disorder have not been established. And although African American women commonly present with the condition, the exact prevalence remains unknown, said Dr. Angela Kyei and her associates at the Cleveland Clinic Institute of Dermatology and Plastic Surgery.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) – previously known as hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome – is a scarring hair loss centered on the vertex of the scalp and spreading peripherally, which is described almost exclusively in African American women. In the late 1960s it was linked to the use of hot combs, but since then almost every method of hair grooming in this population has been associated, albeit weakly, with the disorder. Few studies have examined other possible etiologies, such as immunologic, dermatologic, or genetic factors.

"Given the lack of epidemiologic data, the main goal of [our] study was to elucidate environmental as well as medical risk factors that may be associated with CCCA," the researchers wrote.

They administered questionnaires to 326 African American women attending two churches and a health fair in the Cleveland area. Sixteen of the women ended up being excluded from the analysis.

The questionnaires asked detailed information about family history of male- and female-pattern hair loss; personal medical history, including bacterial and fungal skin infections, autoimmune conditions, and hormonal dysregulation; and hair grooming methods used. The study subjects also underwent a scalp examination that included the grading of hair loss.

A total of 86 of the 310 women (28%) were judged to have central hair loss. Of these, 52 women – 17% of the total study population – had CCCA.

It appeared that hair grooming practices that cause traction, such as weaves and braids, may contribute to the development of CCCA, as women with the most severe central hair loss used these styles more frequently than did those without hair loss. "This has some clinical bearing because traction can clinically produce folliculitis of the scalp, which can cause scarring if this inflammation is prolonged," noted Dr. Kyei and her colleagues (Arch. Dermatol. 2011 April 11 [doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.66]).

After paying hundreds of dollars for such hair styling, women often maintain weaves and braids for weeks to months, so any reactive inflammation usually is prolonged, the investigators added.

However, "the relationship between chemical relaxer use and the development of CCCA continues to be murky," they noted. These products clearly weaken the hair shaft, which can cause breakage, but that does not necessarily lead to CCCA. "The fact that most African Americans use chemical relaxers in combination with braiding and other hair grooming practices makes it even more difficult to tease out a relationship," Dr. Kyei and her associates added.

It is difficult to find subjects who do not use chemical relaxers for comparison, since most African Americans begin the practice in childhood. In this study, 91% of the women reported using chemical relaxers, and began doing so at an average age of 10 years.

Nevertheless, "we feel that it is not unreasonable to assume that the scalp may absorb some of the caustic chemicals found in relaxers, which in time leads to damage of the scalp in the form of scarring," they wrote.

Although the prevalence of bacterial skin infections in these study subjects was only 11%, there was a significant elevation among women with CCCA, compared with women who did not have CCCA. The rate of acne also was elevated in affected subjects, but not to a significant degree. Thus, the researchers said that their study "demonstrates that inflammation in the form of bacterial infection and acne may also be contributing to the development of CCCA, a finding consistent with the histopathologic characteristics of this disease," which show a lymphocytic perifollicular infiltrate in its early stages.

In contrast, there was no such association with fungal infections of the scalp, ringworm, or vaginal yeast infections, which was "surprising given how prone this population is to fungal infection," they added.

"One of the most surprising findings ... was the overrepresentation of type 2 [diabetes mellitus] in those with CCCA," the authors noted. Again, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was low, at 8%, but it was significantly elevated in women with CCCA, compared with those without CCCA.

"These are important data that need further study because CCCA may be a marker of metabolic dysfunction and, when present, can prompt clinicians to do further testing for diabetes mellitus," Dr. Kyei and her colleagues wrote.

Only 9% of the study subjects had thyroid abnormalities, and three-fourths of them had no or minimal hair loss.

A history of male-pattern baldness in the maternal grandfather was found to be a risk factor for CCCA, which suggests that genetics may play a role.

Hormonal dysregulation did not appear to be associated with development of CCCA. Neither were scarring disorders, since only 6% of the subjects reported a history of keloids, and the rate was no higher in women with CCCA than in those without CCCA.

Similarly, there were relatively high prevalences of seborrheic dermatitis (24%), eczema (13%), and contact dermatitis from chemical relaxers (9%), as would be expected in an African American population. However, these conditions were unrelated to CCCA.

This study was supported in part by the North American Hair Research Society and Procter & Gamble. No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Despite being the most common pattern of scarring hair loss among African American women, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is still poorly understood, according to a report published online April 11 in Archives of Dermatology.

The etiology of and risk factors for the disorder have not been established. And although African American women commonly present with the condition, the exact prevalence remains unknown, said Dr. Angela Kyei and her associates at the Cleveland Clinic Institute of Dermatology and Plastic Surgery.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) – previously known as hot comb alopecia or follicular degeneration syndrome – is a scarring hair loss centered on the vertex of the scalp and spreading peripherally, which is described almost exclusively in African American women. In the late 1960s it was linked to the use of hot combs, but since then almost every method of hair grooming in this population has been associated, albeit weakly, with the disorder. Few studies have examined other possible etiologies, such as immunologic, dermatologic, or genetic factors.

"Given the lack of epidemiologic data, the main goal of [our] study was to elucidate environmental as well as medical risk factors that may be associated with CCCA," the researchers wrote.

They administered questionnaires to 326 African American women attending two churches and a health fair in the Cleveland area. Sixteen of the women ended up being excluded from the analysis.

The questionnaires asked detailed information about family history of male- and female-pattern hair loss; personal medical history, including bacterial and fungal skin infections, autoimmune conditions, and hormonal dysregulation; and hair grooming methods used. The study subjects also underwent a scalp examination that included the grading of hair loss.

A total of 86 of the 310 women (28%) were judged to have central hair loss. Of these, 52 women – 17% of the total study population – had CCCA.

It appeared that hair grooming practices that cause traction, such as weaves and braids, may contribute to the development of CCCA, as women with the most severe central hair loss used these styles more frequently than did those without hair loss. "This has some clinical bearing because traction can clinically produce folliculitis of the scalp, which can cause scarring if this inflammation is prolonged," noted Dr. Kyei and her colleagues (Arch. Dermatol. 2011 April 11 [doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.66]).

After paying hundreds of dollars for such hair styling, women often maintain weaves and braids for weeks to months, so any reactive inflammation usually is prolonged, the investigators added.

However, "the relationship between chemical relaxer use and the development of CCCA continues to be murky," they noted. These products clearly weaken the hair shaft, which can cause breakage, but that does not necessarily lead to CCCA. "The fact that most African Americans use chemical relaxers in combination with braiding and other hair grooming practices makes it even more difficult to tease out a relationship," Dr. Kyei and her associates added.

It is difficult to find subjects who do not use chemical relaxers for comparison, since most African Americans begin the practice in childhood. In this study, 91% of the women reported using chemical relaxers, and began doing so at an average age of 10 years.

Nevertheless, "we feel that it is not unreasonable to assume that the scalp may absorb some of the caustic chemicals found in relaxers, which in time leads to damage of the scalp in the form of scarring," they wrote.

Although the prevalence of bacterial skin infections in these study subjects was only 11%, there was a significant elevation among women with CCCA, compared with women who did not have CCCA. The rate of acne also was elevated in affected subjects, but not to a significant degree. Thus, the researchers said that their study "demonstrates that inflammation in the form of bacterial infection and acne may also be contributing to the development of CCCA, a finding consistent with the histopathologic characteristics of this disease," which show a lymphocytic perifollicular infiltrate in its early stages.

In contrast, there was no such association with fungal infections of the scalp, ringworm, or vaginal yeast infections, which was "surprising given how prone this population is to fungal infection," they added.

"One of the most surprising findings ... was the overrepresentation of type 2 [diabetes mellitus] in those with CCCA," the authors noted. Again, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was low, at 8%, but it was significantly elevated in women with CCCA, compared with those without CCCA.

"These are important data that need further study because CCCA may be a marker of metabolic dysfunction and, when present, can prompt clinicians to do further testing for diabetes mellitus," Dr. Kyei and her colleagues wrote.

Only 9% of the study subjects had thyroid abnormalities, and three-fourths of them had no or minimal hair loss.

A history of male-pattern baldness in the maternal grandfather was found to be a risk factor for CCCA, which suggests that genetics may play a role.

Hormonal dysregulation did not appear to be associated with development of CCCA. Neither were scarring disorders, since only 6% of the subjects reported a history of keloids, and the rate was no higher in women with CCCA than in those without CCCA.

Similarly, there were relatively high prevalences of seborrheic dermatitis (24%), eczema (13%), and contact dermatitis from chemical relaxers (9%), as would be expected in an African American population. However, these conditions were unrelated to CCCA.

This study was supported in part by the North American Hair Research Society and Procter & Gamble. No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM ARCHIVES OF DERMATOLOGY

Major Finding: A total of 86 of the 310 women (28%) were judged to have central hair loss. Of these, 52 women – 17% of the total study population – had CCCA.

Data Source: A community-based cross-sectional survey of 326 African American women.

Disclosures: This study was supported in part by the North American Hair Research Society and Procter & Gamble. No financial conflicts of interest were reported.