User login

Mental health risks higher among young people with IBD

, a new U.K. study suggests.

The retrospective, observational study of young people with IBD versus those without assessed the incidence of a wide range of mental health conditions in people aged 5-25 years.

“Anxiety and depression will not be a surprise to most of us. But we also saw changes for eating disorders, PTSD, and sleep changes,” said Richard K. Russell, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh.

Dr. Russell presented the research at the annual congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, held in Copenhagen and virtually.

The findings indicate an unmet need for mental health care for young patients with IBD, he said. “All of us at ECCO need to address this gap.”

Key findings

Dr. Russell and colleagues identified 3,898 young people diagnosed with IBD in the 10-year period Jan. 1, 2010, through Jan. 1, 2020, using the Optimum Patient Care Research Database, which includes de-identified data from more than 1,000 general practices across the United Kingdom. They used propensity score matching to create a control group of 15,571 people without IBD, controlling for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and health conditions other than IBD.

Median follow-up was about 3 years.

The cumulative lifetime risk for developing any mental health condition by age 25 was 31.1% in the IBD group versus 25.1% in controls, a statistically significant difference.

Compared with the control group, the people with incident IBD were significantly more likely to develop the following:

- PTSD.

- Eating disorders.

- Self-harm.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorder.

- ‘Any mental health condition.’

Those most are risk included males overall, and specifically boys aged 12-17 years. Those with Crohn’s disease versus other types of IBD were also most at risk.

In a subgroup analysis, presented as a poster at the meeting, Dr. Russell and colleagues also found that mental health comorbidity in children and young adults with IBD is associated with increased IBD symptoms and health care utilization, as well as time off work.

Children and young adults with both IBD and mental health conditions should be monitored and receive appropriate mental health support as part of their multidisciplinary care, Dr. Russell said.

Dr. Russell added that the study period ended a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, so the research does not reflect its impact on mental health in the study population.

“The number of children and young adults we’re seeing in our clinic with mental health issues has rocketed through the roof because of the pandemic,” he said.

Dr. Russell suggested that the organization create a psychology subgroup called Proactive Psychologists of ECCO, or Prosecco for short.

Clinical implications

The study is important for highlighting the increased burden of mental health problems in young people with IBD, said session comoderator Nick Kennedy, MD, a consultant gastroenterologist and chief research information officer with the Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust in England.

Dr. Kennedy, who was not affiliated with the research, is also supportive of the idea of a psychological subgroup within ECCO.

The peak age for developing mental health disorders found by the study (12-17 years) “is a unique and very sensitive time,” said Sara Mesilhy, MBBS, a gastroenterologist with the Royal College of Physicians in London.

“These results highlight the need for development of early screening psychiatric programs starting from time of diagnosis and continuing on periodic intervals to offer the best management plan for IBD patients, especially those with childhood-onset IBD,” said Dr. Mesilhy, who was not affiliated with the research.

Such programs would “improve the patient’s quality of life, protecting them from a lot of suffering and preventing the bad sequelae for these disorders,” said Dr. Mesilhy. “Moreover, we still need further studies to identify the most efficient monitoring and treatment protocols.”

Dr. Kennedy applauded the researchers for conducting a population-based study because it ensured an adequate cohort size and maximized identification of mental health disorders.

“It was interesting to see that there were a range of conditions where risk was increased, and that males with IBD were at particularly increased risk,” he added.

Researchers’ use of coded primary care data was a study limitation, but it was “appropriately acknowledged by the presenter,” Dr. Kennedy said.

The study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Russell disclosed he is a consultant and member of a speakers’ bureau for Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Mesilhy report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new U.K. study suggests.

The retrospective, observational study of young people with IBD versus those without assessed the incidence of a wide range of mental health conditions in people aged 5-25 years.

“Anxiety and depression will not be a surprise to most of us. But we also saw changes for eating disorders, PTSD, and sleep changes,” said Richard K. Russell, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh.

Dr. Russell presented the research at the annual congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, held in Copenhagen and virtually.

The findings indicate an unmet need for mental health care for young patients with IBD, he said. “All of us at ECCO need to address this gap.”

Key findings

Dr. Russell and colleagues identified 3,898 young people diagnosed with IBD in the 10-year period Jan. 1, 2010, through Jan. 1, 2020, using the Optimum Patient Care Research Database, which includes de-identified data from more than 1,000 general practices across the United Kingdom. They used propensity score matching to create a control group of 15,571 people without IBD, controlling for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and health conditions other than IBD.

Median follow-up was about 3 years.

The cumulative lifetime risk for developing any mental health condition by age 25 was 31.1% in the IBD group versus 25.1% in controls, a statistically significant difference.

Compared with the control group, the people with incident IBD were significantly more likely to develop the following:

- PTSD.

- Eating disorders.

- Self-harm.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorder.

- ‘Any mental health condition.’

Those most are risk included males overall, and specifically boys aged 12-17 years. Those with Crohn’s disease versus other types of IBD were also most at risk.

In a subgroup analysis, presented as a poster at the meeting, Dr. Russell and colleagues also found that mental health comorbidity in children and young adults with IBD is associated with increased IBD symptoms and health care utilization, as well as time off work.

Children and young adults with both IBD and mental health conditions should be monitored and receive appropriate mental health support as part of their multidisciplinary care, Dr. Russell said.

Dr. Russell added that the study period ended a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, so the research does not reflect its impact on mental health in the study population.

“The number of children and young adults we’re seeing in our clinic with mental health issues has rocketed through the roof because of the pandemic,” he said.

Dr. Russell suggested that the organization create a psychology subgroup called Proactive Psychologists of ECCO, or Prosecco for short.

Clinical implications

The study is important for highlighting the increased burden of mental health problems in young people with IBD, said session comoderator Nick Kennedy, MD, a consultant gastroenterologist and chief research information officer with the Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust in England.

Dr. Kennedy, who was not affiliated with the research, is also supportive of the idea of a psychological subgroup within ECCO.

The peak age for developing mental health disorders found by the study (12-17 years) “is a unique and very sensitive time,” said Sara Mesilhy, MBBS, a gastroenterologist with the Royal College of Physicians in London.

“These results highlight the need for development of early screening psychiatric programs starting from time of diagnosis and continuing on periodic intervals to offer the best management plan for IBD patients, especially those with childhood-onset IBD,” said Dr. Mesilhy, who was not affiliated with the research.

Such programs would “improve the patient’s quality of life, protecting them from a lot of suffering and preventing the bad sequelae for these disorders,” said Dr. Mesilhy. “Moreover, we still need further studies to identify the most efficient monitoring and treatment protocols.”

Dr. Kennedy applauded the researchers for conducting a population-based study because it ensured an adequate cohort size and maximized identification of mental health disorders.

“It was interesting to see that there were a range of conditions where risk was increased, and that males with IBD were at particularly increased risk,” he added.

Researchers’ use of coded primary care data was a study limitation, but it was “appropriately acknowledged by the presenter,” Dr. Kennedy said.

The study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Russell disclosed he is a consultant and member of a speakers’ bureau for Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Mesilhy report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new U.K. study suggests.

The retrospective, observational study of young people with IBD versus those without assessed the incidence of a wide range of mental health conditions in people aged 5-25 years.

“Anxiety and depression will not be a surprise to most of us. But we also saw changes for eating disorders, PTSD, and sleep changes,” said Richard K. Russell, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh.

Dr. Russell presented the research at the annual congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, held in Copenhagen and virtually.

The findings indicate an unmet need for mental health care for young patients with IBD, he said. “All of us at ECCO need to address this gap.”

Key findings

Dr. Russell and colleagues identified 3,898 young people diagnosed with IBD in the 10-year period Jan. 1, 2010, through Jan. 1, 2020, using the Optimum Patient Care Research Database, which includes de-identified data from more than 1,000 general practices across the United Kingdom. They used propensity score matching to create a control group of 15,571 people without IBD, controlling for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and health conditions other than IBD.

Median follow-up was about 3 years.

The cumulative lifetime risk for developing any mental health condition by age 25 was 31.1% in the IBD group versus 25.1% in controls, a statistically significant difference.

Compared with the control group, the people with incident IBD were significantly more likely to develop the following:

- PTSD.

- Eating disorders.

- Self-harm.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorder.

- ‘Any mental health condition.’

Those most are risk included males overall, and specifically boys aged 12-17 years. Those with Crohn’s disease versus other types of IBD were also most at risk.

In a subgroup analysis, presented as a poster at the meeting, Dr. Russell and colleagues also found that mental health comorbidity in children and young adults with IBD is associated with increased IBD symptoms and health care utilization, as well as time off work.

Children and young adults with both IBD and mental health conditions should be monitored and receive appropriate mental health support as part of their multidisciplinary care, Dr. Russell said.

Dr. Russell added that the study period ended a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, so the research does not reflect its impact on mental health in the study population.

“The number of children and young adults we’re seeing in our clinic with mental health issues has rocketed through the roof because of the pandemic,” he said.

Dr. Russell suggested that the organization create a psychology subgroup called Proactive Psychologists of ECCO, or Prosecco for short.

Clinical implications

The study is important for highlighting the increased burden of mental health problems in young people with IBD, said session comoderator Nick Kennedy, MD, a consultant gastroenterologist and chief research information officer with the Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust in England.

Dr. Kennedy, who was not affiliated with the research, is also supportive of the idea of a psychological subgroup within ECCO.

The peak age for developing mental health disorders found by the study (12-17 years) “is a unique and very sensitive time,” said Sara Mesilhy, MBBS, a gastroenterologist with the Royal College of Physicians in London.

“These results highlight the need for development of early screening psychiatric programs starting from time of diagnosis and continuing on periodic intervals to offer the best management plan for IBD patients, especially those with childhood-onset IBD,” said Dr. Mesilhy, who was not affiliated with the research.

Such programs would “improve the patient’s quality of life, protecting them from a lot of suffering and preventing the bad sequelae for these disorders,” said Dr. Mesilhy. “Moreover, we still need further studies to identify the most efficient monitoring and treatment protocols.”

Dr. Kennedy applauded the researchers for conducting a population-based study because it ensured an adequate cohort size and maximized identification of mental health disorders.

“It was interesting to see that there were a range of conditions where risk was increased, and that males with IBD were at particularly increased risk,” he added.

Researchers’ use of coded primary care data was a study limitation, but it was “appropriately acknowledged by the presenter,” Dr. Kennedy said.

The study was supported by Pfizer. Dr. Russell disclosed he is a consultant and member of a speakers’ bureau for Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Mesilhy report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECCO 2023

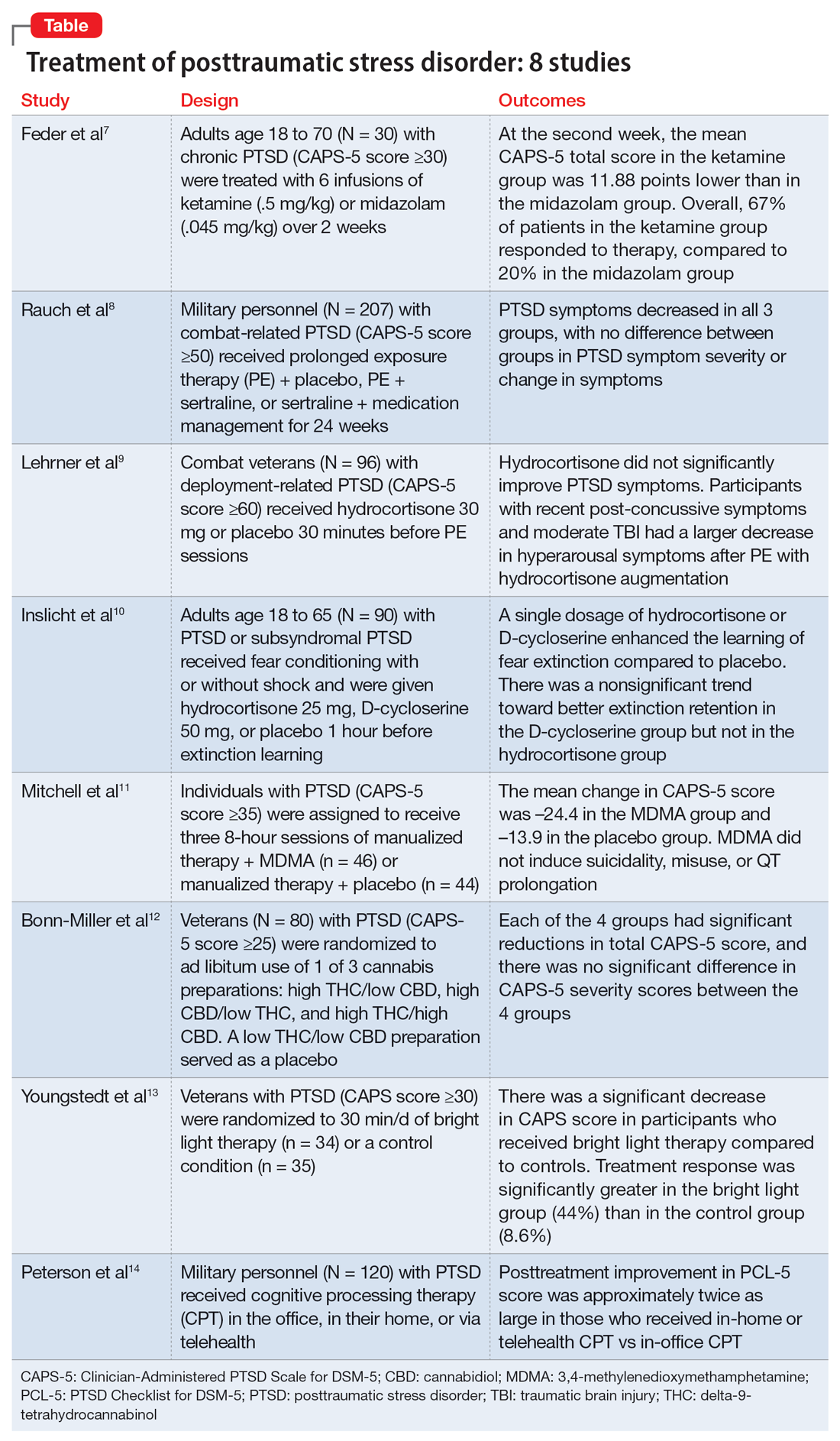

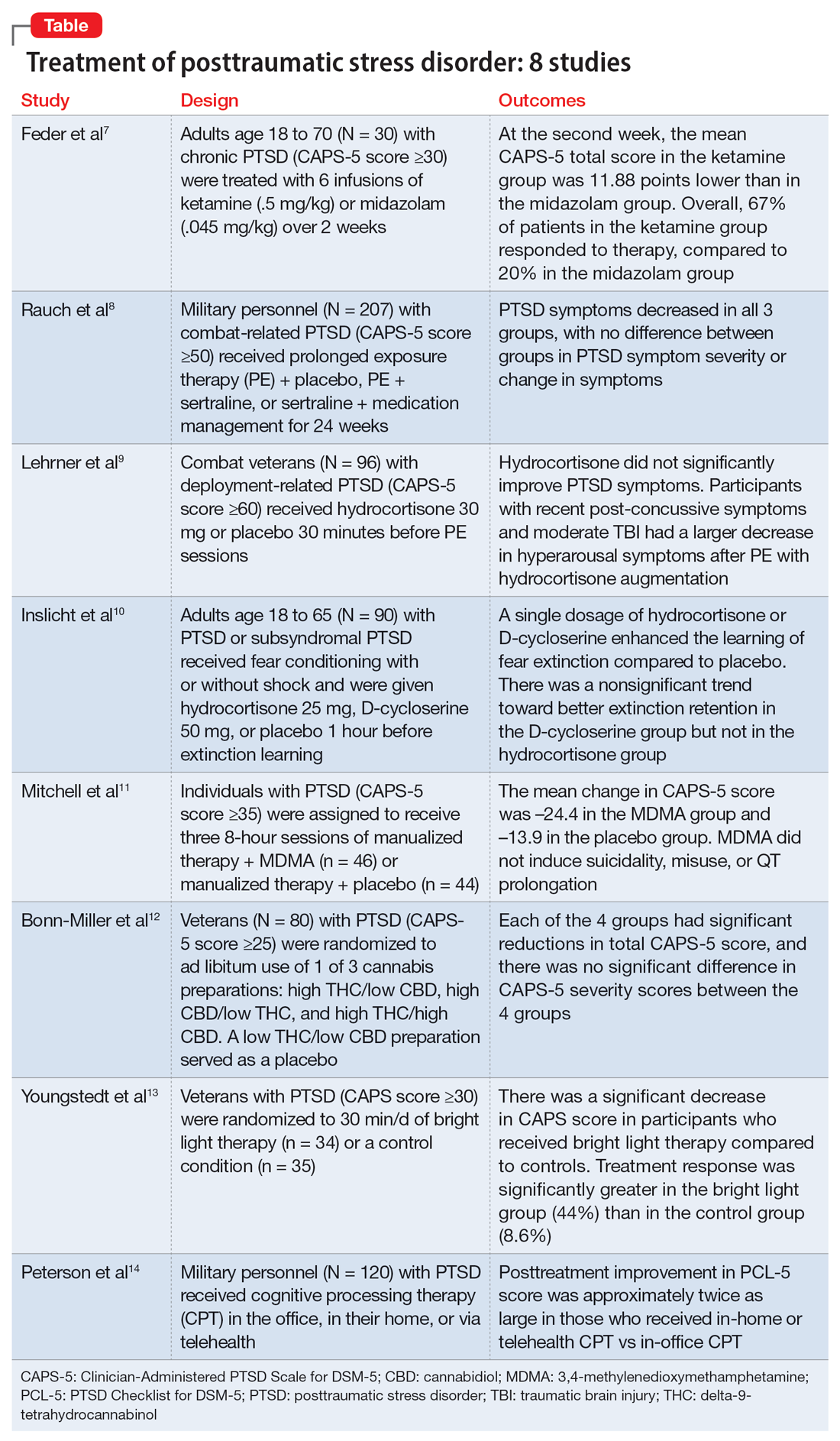

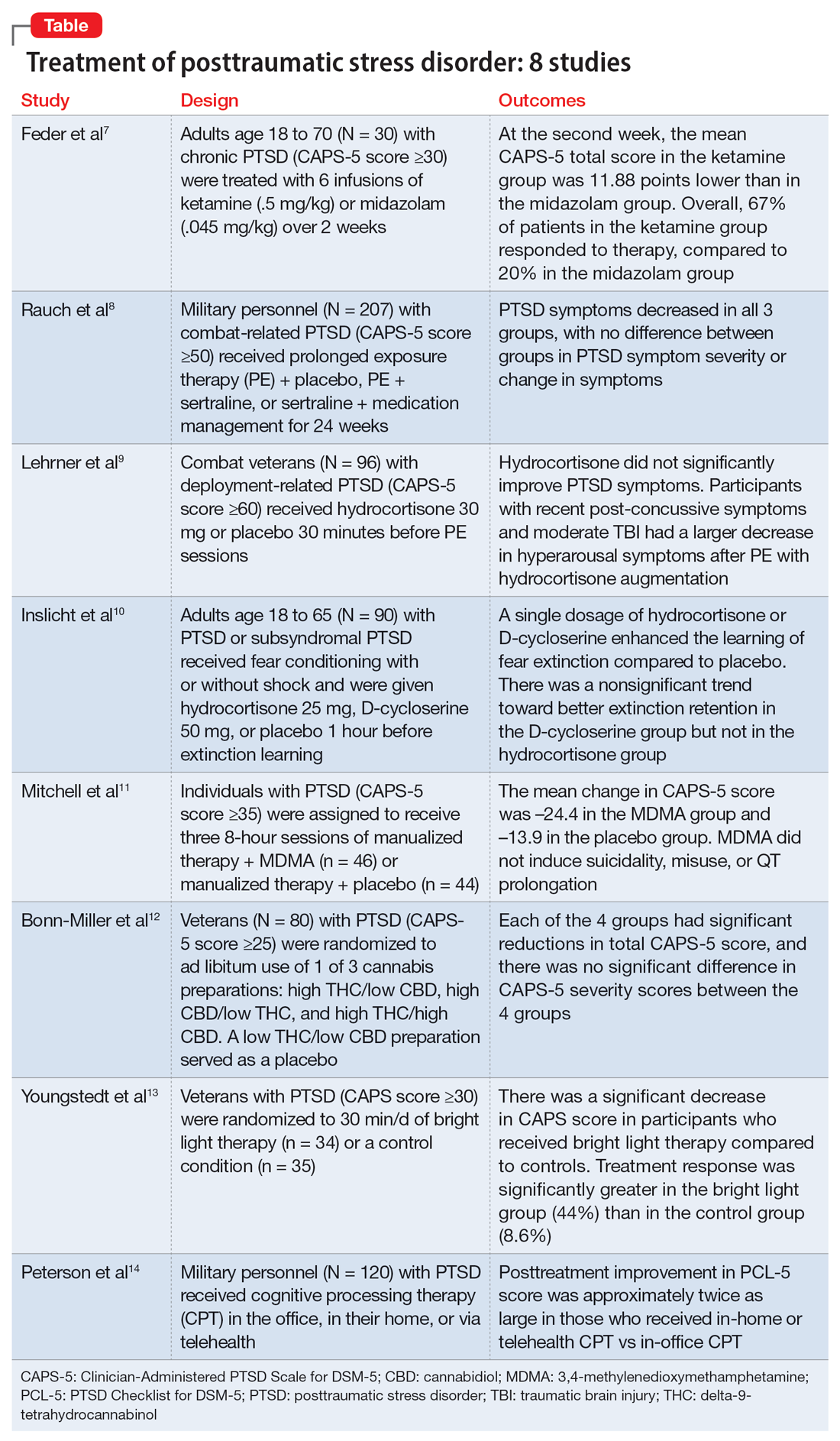

Ketamine plus psychotherapy ‘highly effective’ for PTSD

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of four studies investigating combined use of psychotherapy and ketamine for PTSD, results showed that all the studies showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptom scores.

Overall, the treatment was “highly effective, as seen by the significant improvements in symptoms on multiple measures,” Aaron E. Philipp-Muller, BScH, Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues write.

Furthermore, the study “demonstrates the potential feasibility of this treatment model and corroborates previous work,” the investigators write.

However, a limitation they note was that only 34 participants were included in the analysis.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Emerging treatment

Ketamine is an “emerging treatment for a number of psychopathologies, such as major depressive disorder and PTSD, with a higher response than other pharmacologic agents,” the researchers write.

It is hypothesized that ketamine rapidly facilitates long-term potentiation, “thereby allowing a patient to disengage from an established pattern of thought more readily,” they write.

However, ketamine has several drawbacks, including the fact that it brings only 1 week of relief for PTSD. Also, because it must be administered intravenously, it is “impractical for long-term weekly administration,” they note.

Pharmacologically enhanced psychotherapy is a potential way to prolong ketamine’s effects. Several prior studies have investigated this model using other psychedelic medications, with encouraging results.

The current investigators decided to review all literature to date on the subject of ketamine plus psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD.

To be included, the study had to include patients diagnosed with PTSD, an intervention involving ketamine alongside any form of psychotherapy, and assessment of all patients before and after treatment using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) or the PTSD Checklist (PCL).

Four studies met inclusion criteria. Of these, two were of “moderate” quality and two were of “low” quality, based on the GRADE assessment. The studies encompassed a total of 34 patients with “diverse traumatic experiences” and included several types of ketamine administration protocols, including one used previously for treating depression and another used previously for chronic pain.

The psychotherapy modalities also differed between the studies. In two studies, patients received 12 sessions of trauma interventions using mindfulness-based extinction and reconsolidation therapy; in a third study, patients received 10 weekly sessions of prolonged exposure therapy; and in the fourth study, patients received five daily sessions of exposure therapy.

Across the studies, the psychotherapies were paired differently with ketamine administration, such as the number of ketamine administrations in conjunction with therapy.

Despite the differences in protocols, all the studies of ketamine plus psychotherapy showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, with a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) of –7.26 (95% CI, –12.28 to –2.25; P = .005) for the CAPS and a pooled SMD of –5.17 (95% CI, –7.99 to –2.35; P < .001) for the PCL.

The researchers acknowledge that the sample size was very small “due to the novelty of this research area.” This prompted the inclusion of nonrandomized studies that “lowered the quality of the evidence,” they note.

Nevertheless, “these preliminary findings indicate the potential of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD,” the investigators write.

A promising avenue?

In a comment, Dan Iosifescu, MD, professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, called the combination of ketamine and psychotherapy in PTSD “a very promising treatment avenue.”

Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research, noted that “several PTSD-focused psychotherapies are ultimately very effective but very hard to tolerate for participants.” For example, prolonged exposure therapy has dropout rates as high as 50%.

In addition, ketamine has rapid but not sustained effects in PTSD, he said.

“So in theory, a course of ketamine could help PTSD patients improve rapidly and tolerate the psychotherapy, which could provide sustained benefits,” he added.

However, Dr. Iosifescu cautioned that the data supporting this “is very sparse for now.”

He also noted that the meta-analysis included only “four tiny studies” and had only 34 total participants. In addition, several of the studies had no comparison group and the study designs were all different – “both with respect to the administration of ketamine and to the paired PTSD psychotherapy.”

For this reason, “any conclusions are only a very preliminary suggestion that this may be a fruitful avenue,” he said.

Dr. Iosifescu added that additional studies on this topic are ongoing. The largest one at the Veterans Administration will hopefully include 100 participants and “will provide more reliable evidence for this important topic,” he said.

The study was indirectly supported by the Internal Faculty Grant from the department of psychiatry, Queen’s University. Dr. Iosifescu reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of four studies investigating combined use of psychotherapy and ketamine for PTSD, results showed that all the studies showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptom scores.

Overall, the treatment was “highly effective, as seen by the significant improvements in symptoms on multiple measures,” Aaron E. Philipp-Muller, BScH, Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues write.

Furthermore, the study “demonstrates the potential feasibility of this treatment model and corroborates previous work,” the investigators write.

However, a limitation they note was that only 34 participants were included in the analysis.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Emerging treatment

Ketamine is an “emerging treatment for a number of psychopathologies, such as major depressive disorder and PTSD, with a higher response than other pharmacologic agents,” the researchers write.

It is hypothesized that ketamine rapidly facilitates long-term potentiation, “thereby allowing a patient to disengage from an established pattern of thought more readily,” they write.

However, ketamine has several drawbacks, including the fact that it brings only 1 week of relief for PTSD. Also, because it must be administered intravenously, it is “impractical for long-term weekly administration,” they note.

Pharmacologically enhanced psychotherapy is a potential way to prolong ketamine’s effects. Several prior studies have investigated this model using other psychedelic medications, with encouraging results.

The current investigators decided to review all literature to date on the subject of ketamine plus psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD.

To be included, the study had to include patients diagnosed with PTSD, an intervention involving ketamine alongside any form of psychotherapy, and assessment of all patients before and after treatment using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) or the PTSD Checklist (PCL).

Four studies met inclusion criteria. Of these, two were of “moderate” quality and two were of “low” quality, based on the GRADE assessment. The studies encompassed a total of 34 patients with “diverse traumatic experiences” and included several types of ketamine administration protocols, including one used previously for treating depression and another used previously for chronic pain.

The psychotherapy modalities also differed between the studies. In two studies, patients received 12 sessions of trauma interventions using mindfulness-based extinction and reconsolidation therapy; in a third study, patients received 10 weekly sessions of prolonged exposure therapy; and in the fourth study, patients received five daily sessions of exposure therapy.

Across the studies, the psychotherapies were paired differently with ketamine administration, such as the number of ketamine administrations in conjunction with therapy.

Despite the differences in protocols, all the studies of ketamine plus psychotherapy showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, with a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) of –7.26 (95% CI, –12.28 to –2.25; P = .005) for the CAPS and a pooled SMD of –5.17 (95% CI, –7.99 to –2.35; P < .001) for the PCL.

The researchers acknowledge that the sample size was very small “due to the novelty of this research area.” This prompted the inclusion of nonrandomized studies that “lowered the quality of the evidence,” they note.

Nevertheless, “these preliminary findings indicate the potential of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD,” the investigators write.

A promising avenue?

In a comment, Dan Iosifescu, MD, professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, called the combination of ketamine and psychotherapy in PTSD “a very promising treatment avenue.”

Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research, noted that “several PTSD-focused psychotherapies are ultimately very effective but very hard to tolerate for participants.” For example, prolonged exposure therapy has dropout rates as high as 50%.

In addition, ketamine has rapid but not sustained effects in PTSD, he said.

“So in theory, a course of ketamine could help PTSD patients improve rapidly and tolerate the psychotherapy, which could provide sustained benefits,” he added.

However, Dr. Iosifescu cautioned that the data supporting this “is very sparse for now.”

He also noted that the meta-analysis included only “four tiny studies” and had only 34 total participants. In addition, several of the studies had no comparison group and the study designs were all different – “both with respect to the administration of ketamine and to the paired PTSD psychotherapy.”

For this reason, “any conclusions are only a very preliminary suggestion that this may be a fruitful avenue,” he said.

Dr. Iosifescu added that additional studies on this topic are ongoing. The largest one at the Veterans Administration will hopefully include 100 participants and “will provide more reliable evidence for this important topic,” he said.

The study was indirectly supported by the Internal Faculty Grant from the department of psychiatry, Queen’s University. Dr. Iosifescu reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of four studies investigating combined use of psychotherapy and ketamine for PTSD, results showed that all the studies showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptom scores.

Overall, the treatment was “highly effective, as seen by the significant improvements in symptoms on multiple measures,” Aaron E. Philipp-Muller, BScH, Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues write.

Furthermore, the study “demonstrates the potential feasibility of this treatment model and corroborates previous work,” the investigators write.

However, a limitation they note was that only 34 participants were included in the analysis.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Emerging treatment

Ketamine is an “emerging treatment for a number of psychopathologies, such as major depressive disorder and PTSD, with a higher response than other pharmacologic agents,” the researchers write.

It is hypothesized that ketamine rapidly facilitates long-term potentiation, “thereby allowing a patient to disengage from an established pattern of thought more readily,” they write.

However, ketamine has several drawbacks, including the fact that it brings only 1 week of relief for PTSD. Also, because it must be administered intravenously, it is “impractical for long-term weekly administration,” they note.

Pharmacologically enhanced psychotherapy is a potential way to prolong ketamine’s effects. Several prior studies have investigated this model using other psychedelic medications, with encouraging results.

The current investigators decided to review all literature to date on the subject of ketamine plus psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD.

To be included, the study had to include patients diagnosed with PTSD, an intervention involving ketamine alongside any form of psychotherapy, and assessment of all patients before and after treatment using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) or the PTSD Checklist (PCL).

Four studies met inclusion criteria. Of these, two were of “moderate” quality and two were of “low” quality, based on the GRADE assessment. The studies encompassed a total of 34 patients with “diverse traumatic experiences” and included several types of ketamine administration protocols, including one used previously for treating depression and another used previously for chronic pain.

The psychotherapy modalities also differed between the studies. In two studies, patients received 12 sessions of trauma interventions using mindfulness-based extinction and reconsolidation therapy; in a third study, patients received 10 weekly sessions of prolonged exposure therapy; and in the fourth study, patients received five daily sessions of exposure therapy.

Across the studies, the psychotherapies were paired differently with ketamine administration, such as the number of ketamine administrations in conjunction with therapy.

Despite the differences in protocols, all the studies of ketamine plus psychotherapy showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, with a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) of –7.26 (95% CI, –12.28 to –2.25; P = .005) for the CAPS and a pooled SMD of –5.17 (95% CI, –7.99 to –2.35; P < .001) for the PCL.

The researchers acknowledge that the sample size was very small “due to the novelty of this research area.” This prompted the inclusion of nonrandomized studies that “lowered the quality of the evidence,” they note.

Nevertheless, “these preliminary findings indicate the potential of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD,” the investigators write.

A promising avenue?

In a comment, Dan Iosifescu, MD, professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, called the combination of ketamine and psychotherapy in PTSD “a very promising treatment avenue.”

Dr. Iosifescu, who was not involved with the research, noted that “several PTSD-focused psychotherapies are ultimately very effective but very hard to tolerate for participants.” For example, prolonged exposure therapy has dropout rates as high as 50%.

In addition, ketamine has rapid but not sustained effects in PTSD, he said.

“So in theory, a course of ketamine could help PTSD patients improve rapidly and tolerate the psychotherapy, which could provide sustained benefits,” he added.

However, Dr. Iosifescu cautioned that the data supporting this “is very sparse for now.”

He also noted that the meta-analysis included only “four tiny studies” and had only 34 total participants. In addition, several of the studies had no comparison group and the study designs were all different – “both with respect to the administration of ketamine and to the paired PTSD psychotherapy.”

For this reason, “any conclusions are only a very preliminary suggestion that this may be a fruitful avenue,” he said.

Dr. Iosifescu added that additional studies on this topic are ongoing. The largest one at the Veterans Administration will hopefully include 100 participants and “will provide more reliable evidence for this important topic,” he said.

The study was indirectly supported by the Internal Faculty Grant from the department of psychiatry, Queen’s University. Dr. Iosifescu reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

More on psilocybin

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

I would like to remark on “Psychedelics for treating psychiatric disorders: Are they safe?” (

The Oregon Psilocybin Services that will begin in 2023 are not specific to therapeutic use; this is a common misconception. These are specifically referred to as “psilocybin services” in the Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR), and psilocybin facilitators are required to limit their scope such that they are not practicing psychotherapy or other interventions, even if they do have a medical or psychotherapy background. The intention of the Oregon Psilocybin Services rollout was that these services would not be of the medical model. In the spirit of this, services do not require a medical diagnosis or referral, and services are not a medical or clinical treatment (OAR 333-333-5040). Additionally, services cannot be provided in a health care facility (OAR 441). Facilitators receive robust training as defined by Oregon law, and licensed facilitators provide this information during preparation for services. When discussing this model on a large public scale, I have noticed substantial misconceptions; it is imperative that we refer to these services as they are defined so that individuals with mental health conditions who seek them are aware that such services are different from psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Instead, Oregon Psilocybin Services might be better categorized as supported psilocybin use.

Two short-term exposure therapies linked to PTSD reductions

Two forms of short-term exposure therapy may help reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In addition, remission rates of around 50% were sustained in both groups up to the 6-month mark.

“With about two-thirds of study participants reporting clinically meaningful symptom improvement and more than half losing their PTSD diagnosis, this study provides important new evidence that combat-related PTSD can be effectively treated – in as little as 3 weeks,” lead investigator Alan Peterson, PhD, told this news organization.

Dr. Peterson, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, and director of the Consortium to Alleviate PTSD, noted that while condensed treatments may not be feasible for everyone, “results show that compressed formats adapted to the military context resulted in significant, meaningful, and lasting improvements in PTSD, disability, and functional impairments for most participants.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Breathing, direct exposure, education

The investigators randomly recruited 234 military personnel and veterans from two military treatment facilities and two Veterans Affairs facilities in south and central Texas.

Participants (78% men; mean age, 39 years) were active-duty service members or veterans who had deployed post Sept. 11 and met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. They could receive psychotropic medications at stable doses and were excluded if they had mania, substance abuse, psychosis, or suicidality.

The sample included 44% White participants, 26% Black participants, and 25% Hispanic participants.

The researchers randomly assigned the participants to receive either massed-PE (n = 117) or IOP-PE (n = 117).

PE, the foundation of both protocols, includes psychoeducation about trauma, diaphragmatic breathing, direct and imaginal exposure, and processing of the trauma.

The massed-PE protocol was delivered in 15 daily 90-minute sessions over 3 consecutive weeks, as was the IOP-PE. However, the IOP-PE also included eight additional multiple daily feedback sessions, homework, social support from friends or family, and three booster sessions post treatment.

The investigators conducted baseline assessments and follow-up assessments at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up, there were 57 participants left to analyze in the massed-PE group and 57 in the IOP-PE group.

Significantly decreased symptoms

As measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), PTSD symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to the 1-month follow-up in both groups (massed-PE mean change, –14.13; P < .001; IOP-PE mean change, –13.85; P < .001).

Both groups also failed to meet PTSD diagnostic criteria at 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-ups.

At the 1-month follow-up, 62% of participants who received massed-PE and 48% of those who received IOP-PE no longer met diagnostic criteria on the CAPS-5. Diagnostic remission was maintained in more than half of the massed-PE group (52%) and the IOP-PE group (53%) at the 6-month follow-up.

Disability scores as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale also decreased significantly in both groups (P < .001) from baseline to the 1-month follow-up mark; as did psychosocial functioning scores, as reflected by the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (P < .001).

Dr. Peterson noted that the condensed treatment format could be an essential option to consider even in other countries, such as Ukraine, where there are concerns about PTSD in military personnel.

Study limitations included the lack of a placebo or inactive comparison group, and the lack of generalizability of the results to the entire population of U.S. service members and veterans outside of Texas.

Dr. Peterson said he plans to continue his research and that the compressed treatment formats studied “are well-suited for the evaluation of alternative modes of therapy combining cognitive-behavioral treatments with medications and medical devices.”

Generalizability limited?

Commenting on the research, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s committee on the psychiatric dimensions of disaster, said he was reassured to see participants achieve and keep improvements throughout the study.

“One of the biggest challenges we have, particularly with trauma and stress disorders, is keeping people in therapy” because of the difficult nature of the exposure therapy, said Dr. Morganstein, who was not involved with the research.

“The number of people assigned to each group and who ultimately completed the last follow-up gives a good idea of the utility of the intervention,” he added.

However, Dr. Morganstein noted that some of the exclusion criteria, particularly suicidality and substance abuse, affected the study’s relevance to real-world populations.

“The people in the study become less representative of those who are actually in clinical care,” he said, noting that these two conditions are often comorbid with PTSD.

The study was funded by the Department of Defense, the Defense Health Program, the Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Office of Research and Development, and the Clinical Science Research & Development Service. The investigators and Dr. Morganstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two forms of short-term exposure therapy may help reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In addition, remission rates of around 50% were sustained in both groups up to the 6-month mark.

“With about two-thirds of study participants reporting clinically meaningful symptom improvement and more than half losing their PTSD diagnosis, this study provides important new evidence that combat-related PTSD can be effectively treated – in as little as 3 weeks,” lead investigator Alan Peterson, PhD, told this news organization.

Dr. Peterson, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, and director of the Consortium to Alleviate PTSD, noted that while condensed treatments may not be feasible for everyone, “results show that compressed formats adapted to the military context resulted in significant, meaningful, and lasting improvements in PTSD, disability, and functional impairments for most participants.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Breathing, direct exposure, education

The investigators randomly recruited 234 military personnel and veterans from two military treatment facilities and two Veterans Affairs facilities in south and central Texas.

Participants (78% men; mean age, 39 years) were active-duty service members or veterans who had deployed post Sept. 11 and met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. They could receive psychotropic medications at stable doses and were excluded if they had mania, substance abuse, psychosis, or suicidality.

The sample included 44% White participants, 26% Black participants, and 25% Hispanic participants.

The researchers randomly assigned the participants to receive either massed-PE (n = 117) or IOP-PE (n = 117).

PE, the foundation of both protocols, includes psychoeducation about trauma, diaphragmatic breathing, direct and imaginal exposure, and processing of the trauma.

The massed-PE protocol was delivered in 15 daily 90-minute sessions over 3 consecutive weeks, as was the IOP-PE. However, the IOP-PE also included eight additional multiple daily feedback sessions, homework, social support from friends or family, and three booster sessions post treatment.

The investigators conducted baseline assessments and follow-up assessments at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up, there were 57 participants left to analyze in the massed-PE group and 57 in the IOP-PE group.

Significantly decreased symptoms

As measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), PTSD symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to the 1-month follow-up in both groups (massed-PE mean change, –14.13; P < .001; IOP-PE mean change, –13.85; P < .001).

Both groups also failed to meet PTSD diagnostic criteria at 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-ups.

At the 1-month follow-up, 62% of participants who received massed-PE and 48% of those who received IOP-PE no longer met diagnostic criteria on the CAPS-5. Diagnostic remission was maintained in more than half of the massed-PE group (52%) and the IOP-PE group (53%) at the 6-month follow-up.

Disability scores as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale also decreased significantly in both groups (P < .001) from baseline to the 1-month follow-up mark; as did psychosocial functioning scores, as reflected by the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (P < .001).

Dr. Peterson noted that the condensed treatment format could be an essential option to consider even in other countries, such as Ukraine, where there are concerns about PTSD in military personnel.

Study limitations included the lack of a placebo or inactive comparison group, and the lack of generalizability of the results to the entire population of U.S. service members and veterans outside of Texas.

Dr. Peterson said he plans to continue his research and that the compressed treatment formats studied “are well-suited for the evaluation of alternative modes of therapy combining cognitive-behavioral treatments with medications and medical devices.”

Generalizability limited?

Commenting on the research, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s committee on the psychiatric dimensions of disaster, said he was reassured to see participants achieve and keep improvements throughout the study.

“One of the biggest challenges we have, particularly with trauma and stress disorders, is keeping people in therapy” because of the difficult nature of the exposure therapy, said Dr. Morganstein, who was not involved with the research.

“The number of people assigned to each group and who ultimately completed the last follow-up gives a good idea of the utility of the intervention,” he added.

However, Dr. Morganstein noted that some of the exclusion criteria, particularly suicidality and substance abuse, affected the study’s relevance to real-world populations.

“The people in the study become less representative of those who are actually in clinical care,” he said, noting that these two conditions are often comorbid with PTSD.

The study was funded by the Department of Defense, the Defense Health Program, the Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Office of Research and Development, and the Clinical Science Research & Development Service. The investigators and Dr. Morganstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two forms of short-term exposure therapy may help reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, new research suggests.

In addition, remission rates of around 50% were sustained in both groups up to the 6-month mark.

“With about two-thirds of study participants reporting clinically meaningful symptom improvement and more than half losing their PTSD diagnosis, this study provides important new evidence that combat-related PTSD can be effectively treated – in as little as 3 weeks,” lead investigator Alan Peterson, PhD, told this news organization.

Dr. Peterson, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, and director of the Consortium to Alleviate PTSD, noted that while condensed treatments may not be feasible for everyone, “results show that compressed formats adapted to the military context resulted in significant, meaningful, and lasting improvements in PTSD, disability, and functional impairments for most participants.”

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Breathing, direct exposure, education

The investigators randomly recruited 234 military personnel and veterans from two military treatment facilities and two Veterans Affairs facilities in south and central Texas.

Participants (78% men; mean age, 39 years) were active-duty service members or veterans who had deployed post Sept. 11 and met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. They could receive psychotropic medications at stable doses and were excluded if they had mania, substance abuse, psychosis, or suicidality.

The sample included 44% White participants, 26% Black participants, and 25% Hispanic participants.

The researchers randomly assigned the participants to receive either massed-PE (n = 117) or IOP-PE (n = 117).

PE, the foundation of both protocols, includes psychoeducation about trauma, diaphragmatic breathing, direct and imaginal exposure, and processing of the trauma.

The massed-PE protocol was delivered in 15 daily 90-minute sessions over 3 consecutive weeks, as was the IOP-PE. However, the IOP-PE also included eight additional multiple daily feedback sessions, homework, social support from friends or family, and three booster sessions post treatment.

The investigators conducted baseline assessments and follow-up assessments at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up, there were 57 participants left to analyze in the massed-PE group and 57 in the IOP-PE group.

Significantly decreased symptoms

As measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), PTSD symptoms decreased significantly from baseline to the 1-month follow-up in both groups (massed-PE mean change, –14.13; P < .001; IOP-PE mean change, –13.85; P < .001).

Both groups also failed to meet PTSD diagnostic criteria at 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-ups.

At the 1-month follow-up, 62% of participants who received massed-PE and 48% of those who received IOP-PE no longer met diagnostic criteria on the CAPS-5. Diagnostic remission was maintained in more than half of the massed-PE group (52%) and the IOP-PE group (53%) at the 6-month follow-up.

Disability scores as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale also decreased significantly in both groups (P < .001) from baseline to the 1-month follow-up mark; as did psychosocial functioning scores, as reflected by the Brief Inventory of Psychosocial Functioning (P < .001).

Dr. Peterson noted that the condensed treatment format could be an essential option to consider even in other countries, such as Ukraine, where there are concerns about PTSD in military personnel.

Study limitations included the lack of a placebo or inactive comparison group, and the lack of generalizability of the results to the entire population of U.S. service members and veterans outside of Texas.

Dr. Peterson said he plans to continue his research and that the compressed treatment formats studied “are well-suited for the evaluation of alternative modes of therapy combining cognitive-behavioral treatments with medications and medical devices.”

Generalizability limited?

Commenting on the research, Joshua Morganstein, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s committee on the psychiatric dimensions of disaster, said he was reassured to see participants achieve and keep improvements throughout the study.

“One of the biggest challenges we have, particularly with trauma and stress disorders, is keeping people in therapy” because of the difficult nature of the exposure therapy, said Dr. Morganstein, who was not involved with the research.

“The number of people assigned to each group and who ultimately completed the last follow-up gives a good idea of the utility of the intervention,” he added.

However, Dr. Morganstein noted that some of the exclusion criteria, particularly suicidality and substance abuse, affected the study’s relevance to real-world populations.

“The people in the study become less representative of those who are actually in clinical care,” he said, noting that these two conditions are often comorbid with PTSD.

The study was funded by the Department of Defense, the Defense Health Program, the Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Office of Research and Development, and the Clinical Science Research & Development Service. The investigators and Dr. Morganstein have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Anxiety sensitivity fuels depression in dissociative identity disorder

Anxiety sensitivity refers to fear of the signs and symptoms of anxiety based on the individual’s belief that the signs of anxiety will have harmful consequences, wrote Xi Pan, LICSW, MPA, of McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and colleagues.

Anxiety sensitivity can include cognitive, physical, and social elements: for example, fear that the inability to focus signals mental illness, fear that a racing heart might cause a heart attack, or fear that exhibiting anxiety signs in public (e.g., sweaty palms) will cause embarrassment, the researchers said.

Previous studies have found associations between anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks, and anxiety sensitivity has been shown to contribute to worsening symptoms in patients with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and trauma-related disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder. However, “anxiety sensitivity has not been studied in individuals with complex dissociative disorders such as dissociative identity disorder (DID)” – who often have co-occurring PTSD and depression, the researchers said.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors analyzed data from 21 treatment-seeking adult women with histories of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and dissociative identity disorder. Participants completed the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI), Beck Depression Inventory-II, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation, and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Anxiety sensitivity in cognitive, physical, and social domains was assessed using ASI subscales.

Pearson correlations showed that symptoms of depression were significantly associated with anxiety sensitivity total scores and across all anxiety subscales. However, no direct associations appeared between anxiety sensitivity and PTSD or severe dissociative symptoms.

In a multiple regression analysis, the ASI cognitive subscale was a positive predictor of depressive symptoms, although physical and social subscale scores were not.

The researchers also tested for an indirect relationship between anxiety sensitivity and dissociative symptoms through depression. “Specifically, more severe ASI cognitive concerns were associated with more depressive symptoms, and more depressive symptoms predicted more severe pathological dissociation symptoms,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by the inability to show a direct causal relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depression, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the small sample size, use of self-reports, and the population of mainly White women, which may not generalize to other populations, they said.

However, the results represent the first empirical investigation of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and DID symptoms, and support the value of assessment for anxiety sensitivity in DID patients in clinical practice, they said.

“If high levels of anxiety sensitivity are identified, the individual may benefit from targeted interventions, which in turn may alleviate some symptoms of depression and dissociation in DID,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Anxiety sensitivity refers to fear of the signs and symptoms of anxiety based on the individual’s belief that the signs of anxiety will have harmful consequences, wrote Xi Pan, LICSW, MPA, of McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and colleagues.

Anxiety sensitivity can include cognitive, physical, and social elements: for example, fear that the inability to focus signals mental illness, fear that a racing heart might cause a heart attack, or fear that exhibiting anxiety signs in public (e.g., sweaty palms) will cause embarrassment, the researchers said.

Previous studies have found associations between anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks, and anxiety sensitivity has been shown to contribute to worsening symptoms in patients with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and trauma-related disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder. However, “anxiety sensitivity has not been studied in individuals with complex dissociative disorders such as dissociative identity disorder (DID)” – who often have co-occurring PTSD and depression, the researchers said.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors analyzed data from 21 treatment-seeking adult women with histories of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and dissociative identity disorder. Participants completed the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI), Beck Depression Inventory-II, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation, and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Anxiety sensitivity in cognitive, physical, and social domains was assessed using ASI subscales.

Pearson correlations showed that symptoms of depression were significantly associated with anxiety sensitivity total scores and across all anxiety subscales. However, no direct associations appeared between anxiety sensitivity and PTSD or severe dissociative symptoms.

In a multiple regression analysis, the ASI cognitive subscale was a positive predictor of depressive symptoms, although physical and social subscale scores were not.

The researchers also tested for an indirect relationship between anxiety sensitivity and dissociative symptoms through depression. “Specifically, more severe ASI cognitive concerns were associated with more depressive symptoms, and more depressive symptoms predicted more severe pathological dissociation symptoms,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by the inability to show a direct causal relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depression, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the small sample size, use of self-reports, and the population of mainly White women, which may not generalize to other populations, they said.

However, the results represent the first empirical investigation of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and DID symptoms, and support the value of assessment for anxiety sensitivity in DID patients in clinical practice, they said.

“If high levels of anxiety sensitivity are identified, the individual may benefit from targeted interventions, which in turn may alleviate some symptoms of depression and dissociation in DID,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Anxiety sensitivity refers to fear of the signs and symptoms of anxiety based on the individual’s belief that the signs of anxiety will have harmful consequences, wrote Xi Pan, LICSW, MPA, of McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and colleagues.

Anxiety sensitivity can include cognitive, physical, and social elements: for example, fear that the inability to focus signals mental illness, fear that a racing heart might cause a heart attack, or fear that exhibiting anxiety signs in public (e.g., sweaty palms) will cause embarrassment, the researchers said.

Previous studies have found associations between anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks, and anxiety sensitivity has been shown to contribute to worsening symptoms in patients with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and trauma-related disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder. However, “anxiety sensitivity has not been studied in individuals with complex dissociative disorders such as dissociative identity disorder (DID)” – who often have co-occurring PTSD and depression, the researchers said.

In a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, the authors analyzed data from 21 treatment-seeking adult women with histories of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and dissociative identity disorder. Participants completed the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI), Beck Depression Inventory-II, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation, and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Anxiety sensitivity in cognitive, physical, and social domains was assessed using ASI subscales.

Pearson correlations showed that symptoms of depression were significantly associated with anxiety sensitivity total scores and across all anxiety subscales. However, no direct associations appeared between anxiety sensitivity and PTSD or severe dissociative symptoms.

In a multiple regression analysis, the ASI cognitive subscale was a positive predictor of depressive symptoms, although physical and social subscale scores were not.

The researchers also tested for an indirect relationship between anxiety sensitivity and dissociative symptoms through depression. “Specifically, more severe ASI cognitive concerns were associated with more depressive symptoms, and more depressive symptoms predicted more severe pathological dissociation symptoms,” they wrote.

The findings were limited by the inability to show a direct causal relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depression, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the small sample size, use of self-reports, and the population of mainly White women, which may not generalize to other populations, they said.

However, the results represent the first empirical investigation of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and DID symptoms, and support the value of assessment for anxiety sensitivity in DID patients in clinical practice, they said.

“If high levels of anxiety sensitivity are identified, the individual may benefit from targeted interventions, which in turn may alleviate some symptoms of depression and dissociation in DID,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

More support for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD

The MAPP2 study is the second randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD.

The investigators confirm results of the MAPP1 study, which were published in Nature Medicine. Patients who received MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in MAPP1 demonstrated greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy, compared with participants who received psychotherapy with placebo.

The design of the MAPP2 study was similar to that of MAPP1, and its results were similar, the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which sponsored MAPP1 and MAPP2, said in a news release.

No specific results from MAPP2 were provided at this time. The full data from MAPP2 are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal later this year, and a new drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will follow.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to MDMA as an adjunct to psychotherapy for adults with PTSD in 2017.

MAPS was founded in 1986 to fund and facilitate research into the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapies; to educate the public about psychedelics for medical, social, and spiritual use; and to advocate for drug policy reform.

“When I first articulated a plan to legitimize a psychedelic-assisted therapy through FDA approval, many people said it was impossible,” Rick Doblin, PhD, founder and executive director of MAPS, said in the news release.

“Thirty-seven years later, we are on the precipice of bringing a novel therapy to the millions of Americans living with PTSD who haven’t found relief through current treatments,” said Dr. Doblin.

“The impossible became possible through the bravery of clinical trial participants, the compassion of mental health practitioners, and the generosity of thousands of donors. Today, we can imagine that MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD may soon be available and accessible to all who could benefit,” Dr. Doblin added.

According to MAPS, phase 2 trials are being planned or conducted regarding the efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapies for substance use disorder and eating disorders, as well as couples therapy and group therapy among veterans.

Currently, no psychedelic-assisted therapy has been approved by the FDA or other regulatory authorities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The MAPP2 study is the second randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD.

The investigators confirm results of the MAPP1 study, which were published in Nature Medicine. Patients who received MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in MAPP1 demonstrated greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy, compared with participants who received psychotherapy with placebo.

The design of the MAPP2 study was similar to that of MAPP1, and its results were similar, the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which sponsored MAPP1 and MAPP2, said in a news release.

No specific results from MAPP2 were provided at this time. The full data from MAPP2 are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal later this year, and a new drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will follow.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to MDMA as an adjunct to psychotherapy for adults with PTSD in 2017.

MAPS was founded in 1986 to fund and facilitate research into the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapies; to educate the public about psychedelics for medical, social, and spiritual use; and to advocate for drug policy reform.

“When I first articulated a plan to legitimize a psychedelic-assisted therapy through FDA approval, many people said it was impossible,” Rick Doblin, PhD, founder and executive director of MAPS, said in the news release.

“Thirty-seven years later, we are on the precipice of bringing a novel therapy to the millions of Americans living with PTSD who haven’t found relief through current treatments,” said Dr. Doblin.

“The impossible became possible through the bravery of clinical trial participants, the compassion of mental health practitioners, and the generosity of thousands of donors. Today, we can imagine that MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD may soon be available and accessible to all who could benefit,” Dr. Doblin added.

According to MAPS, phase 2 trials are being planned or conducted regarding the efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapies for substance use disorder and eating disorders, as well as couples therapy and group therapy among veterans.

Currently, no psychedelic-assisted therapy has been approved by the FDA or other regulatory authorities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The MAPP2 study is the second randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD.

The investigators confirm results of the MAPP1 study, which were published in Nature Medicine. Patients who received MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in MAPP1 demonstrated greater improvement in PTSD symptoms, mood, and empathy, compared with participants who received psychotherapy with placebo.

The design of the MAPP2 study was similar to that of MAPP1, and its results were similar, the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), which sponsored MAPP1 and MAPP2, said in a news release.

No specific results from MAPP2 were provided at this time. The full data from MAPP2 are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal later this year, and a new drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will follow.

The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation to MDMA as an adjunct to psychotherapy for adults with PTSD in 2017.

MAPS was founded in 1986 to fund and facilitate research into the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapies; to educate the public about psychedelics for medical, social, and spiritual use; and to advocate for drug policy reform.

“When I first articulated a plan to legitimize a psychedelic-assisted therapy through FDA approval, many people said it was impossible,” Rick Doblin, PhD, founder and executive director of MAPS, said in the news release.

“Thirty-seven years later, we are on the precipice of bringing a novel therapy to the millions of Americans living with PTSD who haven’t found relief through current treatments,” said Dr. Doblin.

“The impossible became possible through the bravery of clinical trial participants, the compassion of mental health practitioners, and the generosity of thousands of donors. Today, we can imagine that MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD may soon be available and accessible to all who could benefit,” Dr. Doblin added.

According to MAPS, phase 2 trials are being planned or conducted regarding the efficacy of MDMA-assisted therapies for substance use disorder and eating disorders, as well as couples therapy and group therapy among veterans.

Currently, no psychedelic-assisted therapy has been approved by the FDA or other regulatory authorities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More evidence suicidal thoughts, behaviors are genetically based

“It’s really important for us to continue to study the genetic risk factors for suicidal behaviors so we can really understand the biology and develop better treatments,” study investigator Allison E. Ashley-Koch, PhD, professor in the department of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry).

SITB heritability

Suicide is a leading cause of death, particularly among individuals aged 15-29 years. Whereas the global rate of suicide has decreased by 36% in the past 20 years, the rate in the United States has increased by 35%, with the greatest rise in military veterans.

Twin studies suggest heritability for SITB is between 30% and 55%, but the molecular genetic basis of SITB remains elusive.

To address this research gap, investigators conducted a study of 633,778 U.S. military veterans from the Million Veteran Program (MVP) cohort. Of these, 71% had European ancestry, 19% had African ancestry, 8% were Hispanic, and 1% were Asian. Just under 10% of the sample was female.

Study participants donated a blood sample and agreed to have their genetic information linked with their electronic health record data.

From diagnostic codes and other sources, researchers identified 121,211 individuals with SITB. They classified participants with no documented lifetime history of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide death as controls.

Rates of SITB differed significantly by ancestry – 25% in those with African or Hispanic ancestry, 21% in those with Asian ancestry, and 16.8% in those with European ancestry. Rates also differed by age and sex; those with SITB were younger and more likely to be female.

In addition to age and sex, covariates included “genetic principal components,” which Dr. Ashley-Koch said accounts for combining data of individuals with different ethnic/racial backgrounds.

Through meta-analysis, the investigators identified seven genome-wide, significant cross-ancestry risk loci.

To evaluate whether the findings could be replicated, researchers used the International Suicide Genetics Consortium (ISGC), a primarily civilian international consortium of roughly 550,000 individuals of mostly European ancestry.

The analysis showed the top replicated cross-ancestry risk locus was rs6557168, an intronic single-nucleotide variant (SNV) in the ESR1 gene that encodes an estrogen receptor. Previous work identified ESR1 as a causal genetic driver gene for development of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, both of which are risk factors for SITB among veterans.

The second-strongest replicated cross-ancestry locus was rs12808482, an intronic variant in the DRD2 gene, which encodes the D2 dopamine-receptor subtype. The authors noted DRD2 is highly expressed in brain tissue and has been associated with numerous psychiatric phenotypes.

Research suggests DRD2 is associated with other risk factors for SITB, such as schizophrenia, mood disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but DRD2 could also contribute to suicide risk directly. The authors noted it is highly expressed in the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, substantia nigra, and hippocampus.

Outstanding candidate gene

The study revealed a cross-ancestry GWS association for rs10671545, a variant in DCC, which is “also an outstanding candidate gene,” the investigators write.

They note it is expressed in brain tissue, is involved in synaptic plasticity, axon guidance, and circadian entrainment, and has been associated with multiple psychiatric phenotypes.

Researchers also found what they called “intriguing” cross-ancestry GWS associations for the TRAF3 gene, which regulates type-1 interferon production. Many patients receiving interferon therapy develop major depressive disorder and suicidal ideation.

TRAF3 is also associated with antisocial behavior, substance use, and ADHD. Lithium – a standard treatment for bipolar disorder that reduces suicide risk – modulates the expression of TRAF3.

Dr. Ashley-Koch noted the replication of these loci (ESR1, DRD2, TRAF3, and DCC) was in a population of mostly White civilians. “This suggests to us that at least some of the risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors does cross ancestry and also crosses military and civilian populations.”

It was “exciting” that all four genes the study focused on had previously been implicated in other psychiatric disorders, said Dr. Ashley-Koch. “What gave us a little more confidence, above and beyond the replication, was that these genes are somehow important for psychiatric disorders, and not any psychiatric disorders, but the ones that are also associated with a high risk of suicide behavior, such as depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, and ADHD.”

The findings will not have an immediate impact on clinical practice, said Dr. Ashley-Koch.

“We need to take the next step, which is to try to understand how these genetic factors may impact risk and what else is happening biologically to increase that risk. Then once we do that, hopefully we can develop some new treatments,” she added.

‘Valuable and noble’ research

Commenting on the study, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, chief of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, said this kind of genetic research is “valuable and noble.”

Researchers have long been interested in risk factors for suicide among military personnel and veterans, said Dr. Ritchie. Evidence to date suggests being a young male is a risk factor as is feeling excluded or not fitting into the unit, and drug or alcohol addiction.

Dr. Ritchie noted other psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder, are at least partially inherited.

She noted the study’s findings should not be used to discriminate against those who might have the identified genetic loci without clearer evidence of their impact.

“If we were able to identify these genes, would we start screening everybody who joins the military to see if they have these genes, and how would that impact the ability to recruit or retain personnel?”

She agreed additional work is needed to determine if and how carrying these genes might impact clinical care.

In addition, she pointed out that behavior is influenced not only by genetic load but also by environment. “This study may show the impact of the genetic load a little bit more clearly; right now, we tend to look at environmental factors.”

The study was supported by an award from the Clinical Science Research and Development (CSR&D) service of the Veterans Health Administration’s Office of Research and Development. The work was also supported in part by the joint U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Energy MVP CHAMPION program.

Dr. Ashley-Koch reported grants from Veterans Administration during the conduct of the study. Several other coauthors report relationships with industry, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies. The full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Ritchie reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“It’s really important for us to continue to study the genetic risk factors for suicidal behaviors so we can really understand the biology and develop better treatments,” study investigator Allison E. Ashley-Koch, PhD, professor in the department of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry).

SITB heritability

Suicide is a leading cause of death, particularly among individuals aged 15-29 years. Whereas the global rate of suicide has decreased by 36% in the past 20 years, the rate in the United States has increased by 35%, with the greatest rise in military veterans.

Twin studies suggest heritability for SITB is between 30% and 55%, but the molecular genetic basis of SITB remains elusive.

To address this research gap, investigators conducted a study of 633,778 U.S. military veterans from the Million Veteran Program (MVP) cohort. Of these, 71% had European ancestry, 19% had African ancestry, 8% were Hispanic, and 1% were Asian. Just under 10% of the sample was female.

Study participants donated a blood sample and agreed to have their genetic information linked with their electronic health record data.

From diagnostic codes and other sources, researchers identified 121,211 individuals with SITB. They classified participants with no documented lifetime history of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, or suicide death as controls.

Rates of SITB differed significantly by ancestry – 25% in those with African or Hispanic ancestry, 21% in those with Asian ancestry, and 16.8% in those with European ancestry. Rates also differed by age and sex; those with SITB were younger and more likely to be female.

In addition to age and sex, covariates included “genetic principal components,” which Dr. Ashley-Koch said accounts for combining data of individuals with different ethnic/racial backgrounds.