User login

Antibiotic resistance rises among pneumococcus strains in kids

Antibiotic resistance in strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been rising since 2013 because of changing susceptibility profiles, based on data from 1,201 isolates collected from 448 children in primary care settings.

“New strains expressing capsular serotypes not included in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine are emerging to cause disease, and strains that acquire antibiotic resistance are increasing in frequency due to their survival of the fittest advantage,” wrote Ravinder Kaur, PhD, of Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, and colleagues.

Similar Darwinian principles occurred after the introduction of PCV-7, the study authors added.

In a prospective cohort study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed 1,201 isolates collected from the nasopharynx during healthy periods, and from the nasopharynx and middle ear fluid (MEF) during episodes of acute otitis media, in children aged 6-36 months who were seen in primary care settings.

The isolates were collected during 2006-2016 to reflect the pre- and post-PCV13 era. Children received PCV-7 from 2006 until April 2010, and received PCV-13 after April 2010.

Overall, the number of acute otitis media (AOM) cases caused by S. pneumoniae was not significantly different between the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, nor was the frequency of pneumococci identified in the nasopharynx during healthy visits and visits at the start of an AOM infection.

The researchers examined susceptibility using minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). During healthy visits, the MIC50 of isolated pneumococci was low (no greater than 0.06 mcg/mL) for all four beta-lactam drugs tested. And it didn’t change significantly over the study years.

In contrast, among the nasopharyngeal and MEF isolates during AOM, the MIC50 to penicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, and meropenem during 2013-2016 rose significantly, the investigators said.

A change in antibiotic susceptibility within a subtype also contributed to the development of PCV-13 resistance.

The study authors identified three serotypes that affected the changes in susceptibility in their study population. Serotypes 35B and 35F increased their beta-lactam resistance during 2013-2016, and serotype 11A had a higher MIC to quinolones and became more prevalent during 2013-2016. Those three serotypes accounted for most of the change in antibiotic susceptibility, the researchers said.

In addition, “the frequency of strains resistant to penicillin and amoxicillin decreased with the introduction of PCV-13, but rebounded to levels similar to those before PCV-13 introduction by 2015-2016,” the investigators noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the homogeneous study population and potential lack of generalizability to other settings. In addition, the researchers did not study antibiotic consumption or antibiotic treatment failure, and they could not account for potential AOM cases that may have been treated in settings other than primary care.

However, the investigators said the results support the need for additional studies and attention to the development of the next generation of PCVs, the PCV-15 and PCV-20. Both include serotypes 22F and 33F, but neither includes 35B or 35F. The PCV-20 also includes 11A and 15B.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and Sanofi Pasteur. Some isolates collected during the 2010-2013 time period were part of a study supported by Pfizer. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kaur R et al. Clin Inf Dis. 2020 Feb 18. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa157.

Dr. Kaur and colleagues report their analysis of pneumococcal resistance among nasopharyngeal and middle ear isolates (90% nasopharyngeal and 10% middle ear) collected between 2008 and 2016. They demonstrate the dominant role that nonvaccine serotypes play in carriage and acute otitis media (AOM) in children, and by extension potentially the entire spectrum of pneumococcal disease in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) era. Nonsusceptibility to beta-lactams was reported for one-third of isolates with the increase in the most recent reported years (2013-2016).

What are the implications for treatment of pneumococcal infections? For AOM, amoxicillin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were all less than 4 mcg/mL, which is the pharmacodynamic breakpoint for high-dose (90 mg/kg per day) AOM regimens; these data support continued use of high-dose amoxicillin for children with AOM that requires antimicrobial treatment. Resistance to macrolides (erythromycin and likely azithromycin) occurred in approximately one-third of isolates; however, in contrast to beta-lactams (amoxicillin), higher macrolide doses do not overcome resistance. Thus macrolide use for AOM appears limited to those with beta-lactam allergy and no better alternative drug, i.e., expect failure in one-third of AOM patients if macrolides are used. For ceftriaxone, no 2013-2016 isolate had a MIC over 0.5 mcg/mL, implying that ceftriaxone remains appropriate first-line therapy for serious pneumococcal disease and effective for pneumococcal AOM when oral drugs have failed or are not an option because of repeated emesis. Interestingly, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (T/S) had lower resistance rates against the nonvaccine “bad boy” serogroup 35 (8%-15%), compared with cephalosporins (32%-57%). Perhaps we are back to the future and T/S will again have a role against pneumococcal AOM. Of note, no isolate was resistant to levofloxacin or linezolid. Linezolid or macrolide use alone must be considered with the caveat that nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae now likely surpasses pneumococcus as an AOM pathogen, and neither drug class is active against nontypeable H. influenzae.

What are the implications for prevention? This is one of many studies in the post-PCV era reporting serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes. But most prior studies reported reduced overall disease burden; in other words, the absolute number of pneumococcal infections was reduced, but residual AOM nonvaccine types dominated as the etiology. The current study, however, suggests that the overall number of AOM episodes may not be less because increases in AOM caused by nonvaccine serotypes may be offsetting declines in AOM caused by vaccine serotypes. This concept contrasts to multiple large epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decline in overall incidence of AOM office visits/episodes and several Israeli studies reporting a decline in pneumococcal AOM in children who warrant tympanocentesis. These new data are food for thought, but antibiotic resistance can vary regionally, so confirmation based on data from other regions seems warranted.

Next-generation vaccines will need to consider which serotypes are prevalent in pneumococcal disease, including AOM, as we continue into the PCV13 era. However, serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia would be higher priorities than AOM. Indeed, several candidate PCV vaccines are currently in clinical trials adding up to seven serotypes, including most of the newly emerging invasive disease serotypes. One downside to the newer PCVs is lack of serogroup 35, a prominent culprit in AOM resistance in the current report.

Stephen I. Pelton, MD, is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Pelton has received honorarium from Merck Vaccines, Pfizer, and Sanofi for participation in advisory board meeting on pneumococcal vaccine and/or membership on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Boston Medical Center has received investigator-initiated research grants from Merck Vaccines and Pfizer.

Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City Boston Medical Center has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer for research vaccine studies, and from Pfizer and Merck for investigator-initiated research grants for in vitro pneumococcal investigations on which Dr. Harrison is an investigator.

Dr. Kaur and colleagues report their analysis of pneumococcal resistance among nasopharyngeal and middle ear isolates (90% nasopharyngeal and 10% middle ear) collected between 2008 and 2016. They demonstrate the dominant role that nonvaccine serotypes play in carriage and acute otitis media (AOM) in children, and by extension potentially the entire spectrum of pneumococcal disease in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) era. Nonsusceptibility to beta-lactams was reported for one-third of isolates with the increase in the most recent reported years (2013-2016).

What are the implications for treatment of pneumococcal infections? For AOM, amoxicillin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were all less than 4 mcg/mL, which is the pharmacodynamic breakpoint for high-dose (90 mg/kg per day) AOM regimens; these data support continued use of high-dose amoxicillin for children with AOM that requires antimicrobial treatment. Resistance to macrolides (erythromycin and likely azithromycin) occurred in approximately one-third of isolates; however, in contrast to beta-lactams (amoxicillin), higher macrolide doses do not overcome resistance. Thus macrolide use for AOM appears limited to those with beta-lactam allergy and no better alternative drug, i.e., expect failure in one-third of AOM patients if macrolides are used. For ceftriaxone, no 2013-2016 isolate had a MIC over 0.5 mcg/mL, implying that ceftriaxone remains appropriate first-line therapy for serious pneumococcal disease and effective for pneumococcal AOM when oral drugs have failed or are not an option because of repeated emesis. Interestingly, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (T/S) had lower resistance rates against the nonvaccine “bad boy” serogroup 35 (8%-15%), compared with cephalosporins (32%-57%). Perhaps we are back to the future and T/S will again have a role against pneumococcal AOM. Of note, no isolate was resistant to levofloxacin or linezolid. Linezolid or macrolide use alone must be considered with the caveat that nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae now likely surpasses pneumococcus as an AOM pathogen, and neither drug class is active against nontypeable H. influenzae.

What are the implications for prevention? This is one of many studies in the post-PCV era reporting serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes. But most prior studies reported reduced overall disease burden; in other words, the absolute number of pneumococcal infections was reduced, but residual AOM nonvaccine types dominated as the etiology. The current study, however, suggests that the overall number of AOM episodes may not be less because increases in AOM caused by nonvaccine serotypes may be offsetting declines in AOM caused by vaccine serotypes. This concept contrasts to multiple large epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decline in overall incidence of AOM office visits/episodes and several Israeli studies reporting a decline in pneumococcal AOM in children who warrant tympanocentesis. These new data are food for thought, but antibiotic resistance can vary regionally, so confirmation based on data from other regions seems warranted.

Next-generation vaccines will need to consider which serotypes are prevalent in pneumococcal disease, including AOM, as we continue into the PCV13 era. However, serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia would be higher priorities than AOM. Indeed, several candidate PCV vaccines are currently in clinical trials adding up to seven serotypes, including most of the newly emerging invasive disease serotypes. One downside to the newer PCVs is lack of serogroup 35, a prominent culprit in AOM resistance in the current report.

Stephen I. Pelton, MD, is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Pelton has received honorarium from Merck Vaccines, Pfizer, and Sanofi for participation in advisory board meeting on pneumococcal vaccine and/or membership on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Boston Medical Center has received investigator-initiated research grants from Merck Vaccines and Pfizer.

Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City Boston Medical Center has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer for research vaccine studies, and from Pfizer and Merck for investigator-initiated research grants for in vitro pneumococcal investigations on which Dr. Harrison is an investigator.

Dr. Kaur and colleagues report their analysis of pneumococcal resistance among nasopharyngeal and middle ear isolates (90% nasopharyngeal and 10% middle ear) collected between 2008 and 2016. They demonstrate the dominant role that nonvaccine serotypes play in carriage and acute otitis media (AOM) in children, and by extension potentially the entire spectrum of pneumococcal disease in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) era. Nonsusceptibility to beta-lactams was reported for one-third of isolates with the increase in the most recent reported years (2013-2016).

What are the implications for treatment of pneumococcal infections? For AOM, amoxicillin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were all less than 4 mcg/mL, which is the pharmacodynamic breakpoint for high-dose (90 mg/kg per day) AOM regimens; these data support continued use of high-dose amoxicillin for children with AOM that requires antimicrobial treatment. Resistance to macrolides (erythromycin and likely azithromycin) occurred in approximately one-third of isolates; however, in contrast to beta-lactams (amoxicillin), higher macrolide doses do not overcome resistance. Thus macrolide use for AOM appears limited to those with beta-lactam allergy and no better alternative drug, i.e., expect failure in one-third of AOM patients if macrolides are used. For ceftriaxone, no 2013-2016 isolate had a MIC over 0.5 mcg/mL, implying that ceftriaxone remains appropriate first-line therapy for serious pneumococcal disease and effective for pneumococcal AOM when oral drugs have failed or are not an option because of repeated emesis. Interestingly, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (T/S) had lower resistance rates against the nonvaccine “bad boy” serogroup 35 (8%-15%), compared with cephalosporins (32%-57%). Perhaps we are back to the future and T/S will again have a role against pneumococcal AOM. Of note, no isolate was resistant to levofloxacin or linezolid. Linezolid or macrolide use alone must be considered with the caveat that nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae now likely surpasses pneumococcus as an AOM pathogen, and neither drug class is active against nontypeable H. influenzae.

What are the implications for prevention? This is one of many studies in the post-PCV era reporting serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes. But most prior studies reported reduced overall disease burden; in other words, the absolute number of pneumococcal infections was reduced, but residual AOM nonvaccine types dominated as the etiology. The current study, however, suggests that the overall number of AOM episodes may not be less because increases in AOM caused by nonvaccine serotypes may be offsetting declines in AOM caused by vaccine serotypes. This concept contrasts to multiple large epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decline in overall incidence of AOM office visits/episodes and several Israeli studies reporting a decline in pneumococcal AOM in children who warrant tympanocentesis. These new data are food for thought, but antibiotic resistance can vary regionally, so confirmation based on data from other regions seems warranted.

Next-generation vaccines will need to consider which serotypes are prevalent in pneumococcal disease, including AOM, as we continue into the PCV13 era. However, serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumonia would be higher priorities than AOM. Indeed, several candidate PCV vaccines are currently in clinical trials adding up to seven serotypes, including most of the newly emerging invasive disease serotypes. One downside to the newer PCVs is lack of serogroup 35, a prominent culprit in AOM resistance in the current report.

Stephen I. Pelton, MD, is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital–Kansas City, Mo. Dr. Pelton has received honorarium from Merck Vaccines, Pfizer, and Sanofi for participation in advisory board meeting on pneumococcal vaccine and/or membership on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Boston Medical Center has received investigator-initiated research grants from Merck Vaccines and Pfizer.

Children’s Mercy Hospital – Kansas City Boston Medical Center has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer for research vaccine studies, and from Pfizer and Merck for investigator-initiated research grants for in vitro pneumococcal investigations on which Dr. Harrison is an investigator.

Antibiotic resistance in strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been rising since 2013 because of changing susceptibility profiles, based on data from 1,201 isolates collected from 448 children in primary care settings.

“New strains expressing capsular serotypes not included in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine are emerging to cause disease, and strains that acquire antibiotic resistance are increasing in frequency due to their survival of the fittest advantage,” wrote Ravinder Kaur, PhD, of Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, and colleagues.

Similar Darwinian principles occurred after the introduction of PCV-7, the study authors added.

In a prospective cohort study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed 1,201 isolates collected from the nasopharynx during healthy periods, and from the nasopharynx and middle ear fluid (MEF) during episodes of acute otitis media, in children aged 6-36 months who were seen in primary care settings.

The isolates were collected during 2006-2016 to reflect the pre- and post-PCV13 era. Children received PCV-7 from 2006 until April 2010, and received PCV-13 after April 2010.

Overall, the number of acute otitis media (AOM) cases caused by S. pneumoniae was not significantly different between the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, nor was the frequency of pneumococci identified in the nasopharynx during healthy visits and visits at the start of an AOM infection.

The researchers examined susceptibility using minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). During healthy visits, the MIC50 of isolated pneumococci was low (no greater than 0.06 mcg/mL) for all four beta-lactam drugs tested. And it didn’t change significantly over the study years.

In contrast, among the nasopharyngeal and MEF isolates during AOM, the MIC50 to penicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, and meropenem during 2013-2016 rose significantly, the investigators said.

A change in antibiotic susceptibility within a subtype also contributed to the development of PCV-13 resistance.

The study authors identified three serotypes that affected the changes in susceptibility in their study population. Serotypes 35B and 35F increased their beta-lactam resistance during 2013-2016, and serotype 11A had a higher MIC to quinolones and became more prevalent during 2013-2016. Those three serotypes accounted for most of the change in antibiotic susceptibility, the researchers said.

In addition, “the frequency of strains resistant to penicillin and amoxicillin decreased with the introduction of PCV-13, but rebounded to levels similar to those before PCV-13 introduction by 2015-2016,” the investigators noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the homogeneous study population and potential lack of generalizability to other settings. In addition, the researchers did not study antibiotic consumption or antibiotic treatment failure, and they could not account for potential AOM cases that may have been treated in settings other than primary care.

However, the investigators said the results support the need for additional studies and attention to the development of the next generation of PCVs, the PCV-15 and PCV-20. Both include serotypes 22F and 33F, but neither includes 35B or 35F. The PCV-20 also includes 11A and 15B.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and Sanofi Pasteur. Some isolates collected during the 2010-2013 time period were part of a study supported by Pfizer. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kaur R et al. Clin Inf Dis. 2020 Feb 18. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa157.

Antibiotic resistance in strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been rising since 2013 because of changing susceptibility profiles, based on data from 1,201 isolates collected from 448 children in primary care settings.

“New strains expressing capsular serotypes not included in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine are emerging to cause disease, and strains that acquire antibiotic resistance are increasing in frequency due to their survival of the fittest advantage,” wrote Ravinder Kaur, PhD, of Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, and colleagues.

Similar Darwinian principles occurred after the introduction of PCV-7, the study authors added.

In a prospective cohort study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed 1,201 isolates collected from the nasopharynx during healthy periods, and from the nasopharynx and middle ear fluid (MEF) during episodes of acute otitis media, in children aged 6-36 months who were seen in primary care settings.

The isolates were collected during 2006-2016 to reflect the pre- and post-PCV13 era. Children received PCV-7 from 2006 until April 2010, and received PCV-13 after April 2010.

Overall, the number of acute otitis media (AOM) cases caused by S. pneumoniae was not significantly different between the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, nor was the frequency of pneumococci identified in the nasopharynx during healthy visits and visits at the start of an AOM infection.

The researchers examined susceptibility using minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC). During healthy visits, the MIC50 of isolated pneumococci was low (no greater than 0.06 mcg/mL) for all four beta-lactam drugs tested. And it didn’t change significantly over the study years.

In contrast, among the nasopharyngeal and MEF isolates during AOM, the MIC50 to penicillin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, and meropenem during 2013-2016 rose significantly, the investigators said.

A change in antibiotic susceptibility within a subtype also contributed to the development of PCV-13 resistance.

The study authors identified three serotypes that affected the changes in susceptibility in their study population. Serotypes 35B and 35F increased their beta-lactam resistance during 2013-2016, and serotype 11A had a higher MIC to quinolones and became more prevalent during 2013-2016. Those three serotypes accounted for most of the change in antibiotic susceptibility, the researchers said.

In addition, “the frequency of strains resistant to penicillin and amoxicillin decreased with the introduction of PCV-13, but rebounded to levels similar to those before PCV-13 introduction by 2015-2016,” the investigators noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the homogeneous study population and potential lack of generalizability to other settings. In addition, the researchers did not study antibiotic consumption or antibiotic treatment failure, and they could not account for potential AOM cases that may have been treated in settings other than primary care.

However, the investigators said the results support the need for additional studies and attention to the development of the next generation of PCVs, the PCV-15 and PCV-20. Both include serotypes 22F and 33F, but neither includes 35B or 35F. The PCV-20 also includes 11A and 15B.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and Sanofi Pasteur. Some isolates collected during the 2010-2013 time period were part of a study supported by Pfizer. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kaur R et al. Clin Inf Dis. 2020 Feb 18. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa157.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

U.S. reports first death from COVID-19, possible outbreak at long-term care facility

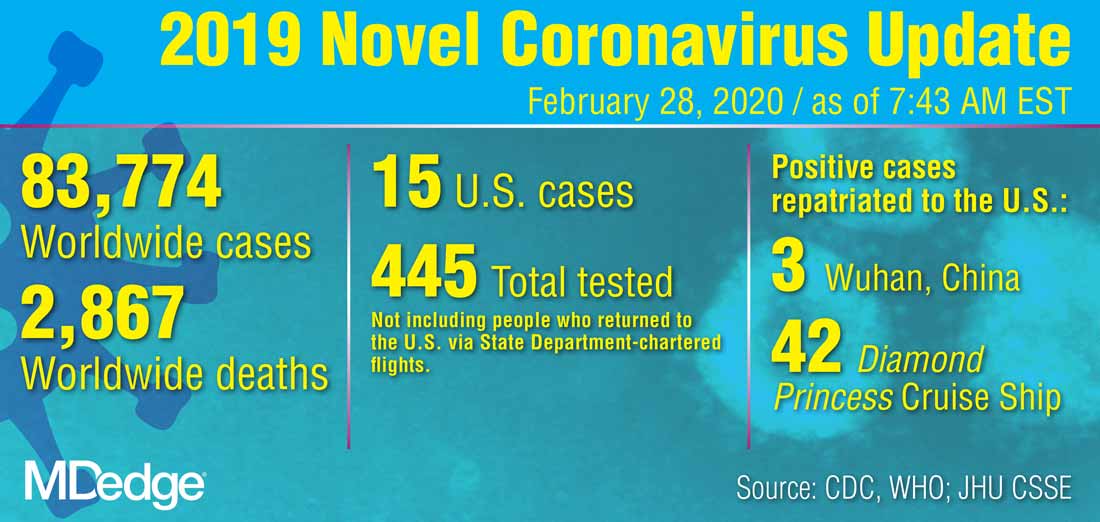

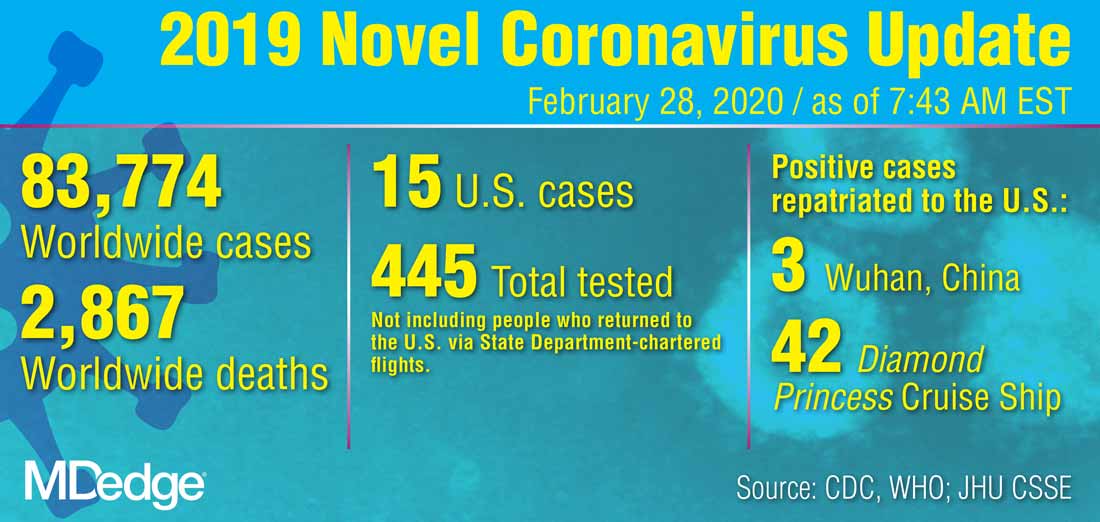

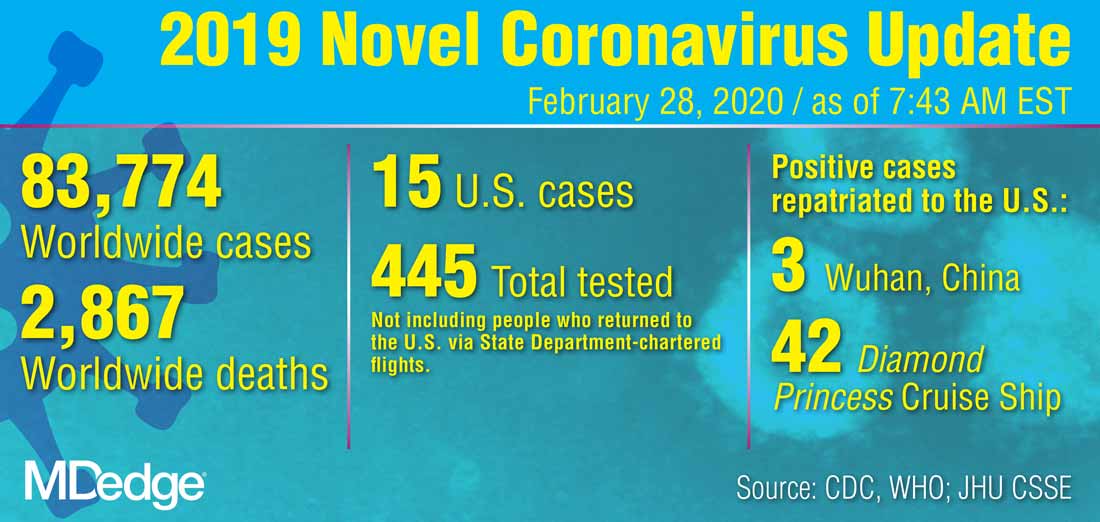

The first death in the United States from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was a Washington state man in his 50s who had underlying health conditions, state health officials announced on Feb 29. At the same time, officials there are investigating a possible COVID-19 outbreak at a long-term care facility.

Washington state officials reported two other presumptive positive cases of COVID-19, both of whom are associated with LifeCare of Kirkland, Washington. One is a woman in her 70s who is a resident at the facility and the other is a woman in her 40s who is a health care worker at the facility.

Additionally, many residents and staff members at the facility have reported respiratory symptoms, according to Jeff Duchin, MD, health officer for public health in Seattle and King County. Among the more than 100 residents at the facility, 27 have respiratory symptoms; while among the 180 staff members, 25 have reported symptoms.

Overall, these reports bring the total number of U.S. COVID-19 cases detected by the public health system to 22, though that number is expected to climb as these investigations continue.

The general risk to the American public is still low, including residents in long-term care facilities, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during the Feb. 29 press briefing. Older people are are higher risk, however, and long-term care facilities should emphasize handwashing and the early identification of individuals with symptoms.

Dr. Duchin added that health care workers who are sick should stay home and that visitors should be screened for symptoms, the same advice offered to limit the spread of influenza at long-term care facilities.

The CDC briefing comes after President Trump held his own press conference at the White House where he identified the person who had died as being a woman in her 50s who was medically at risk.

During that press conference, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that the current pattern of disease with COVID-19 suggests that 75%-80% of patients will have mild illness and recover, while 15%-20% will require advanced medical care.

For the most part, the more serious cases will occur in those who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions. There is “no indication” that individuals who recover from the virus are becoming re-infected, Dr. Fauci said.

The administration also announced a series of actions aimed at slowing the spread of the virus and responding to it. On March 2, President Trump will meet with leaders in the pharmaceutical industry at the White House to discuss vaccine development. The administration is also working to ensure an adequate supply of face masks. Vice President Mike Pence said there are currently more than 40 million masks available, but that the administration has received promises of 35 million more masks per month from manufacturers. Access to masks will be prioritized for high-risk health care workers, Vice President Pence said. “The average American does not need to go out and buy a mask,” he added.

Additionally, Vice President Pence announced new travel restrictions with Iran that would bar entry to the United States for any foreign national who visited Iran in the last 14 days. The federal government is also advising Americans not to travel to the regions in Italy and South Korea that have been most affected by COVID-19. The government is also working with officials in Italy and South Korea to conduct medical screening of anyone coming into the United States from those countries.

The first death in the United States from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was a Washington state man in his 50s who had underlying health conditions, state health officials announced on Feb 29. At the same time, officials there are investigating a possible COVID-19 outbreak at a long-term care facility.

Washington state officials reported two other presumptive positive cases of COVID-19, both of whom are associated with LifeCare of Kirkland, Washington. One is a woman in her 70s who is a resident at the facility and the other is a woman in her 40s who is a health care worker at the facility.

Additionally, many residents and staff members at the facility have reported respiratory symptoms, according to Jeff Duchin, MD, health officer for public health in Seattle and King County. Among the more than 100 residents at the facility, 27 have respiratory symptoms; while among the 180 staff members, 25 have reported symptoms.

Overall, these reports bring the total number of U.S. COVID-19 cases detected by the public health system to 22, though that number is expected to climb as these investigations continue.

The general risk to the American public is still low, including residents in long-term care facilities, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during the Feb. 29 press briefing. Older people are are higher risk, however, and long-term care facilities should emphasize handwashing and the early identification of individuals with symptoms.

Dr. Duchin added that health care workers who are sick should stay home and that visitors should be screened for symptoms, the same advice offered to limit the spread of influenza at long-term care facilities.

The CDC briefing comes after President Trump held his own press conference at the White House where he identified the person who had died as being a woman in her 50s who was medically at risk.

During that press conference, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that the current pattern of disease with COVID-19 suggests that 75%-80% of patients will have mild illness and recover, while 15%-20% will require advanced medical care.

For the most part, the more serious cases will occur in those who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions. There is “no indication” that individuals who recover from the virus are becoming re-infected, Dr. Fauci said.

The administration also announced a series of actions aimed at slowing the spread of the virus and responding to it. On March 2, President Trump will meet with leaders in the pharmaceutical industry at the White House to discuss vaccine development. The administration is also working to ensure an adequate supply of face masks. Vice President Mike Pence said there are currently more than 40 million masks available, but that the administration has received promises of 35 million more masks per month from manufacturers. Access to masks will be prioritized for high-risk health care workers, Vice President Pence said. “The average American does not need to go out and buy a mask,” he added.

Additionally, Vice President Pence announced new travel restrictions with Iran that would bar entry to the United States for any foreign national who visited Iran in the last 14 days. The federal government is also advising Americans not to travel to the regions in Italy and South Korea that have been most affected by COVID-19. The government is also working with officials in Italy and South Korea to conduct medical screening of anyone coming into the United States from those countries.

The first death in the United States from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was a Washington state man in his 50s who had underlying health conditions, state health officials announced on Feb 29. At the same time, officials there are investigating a possible COVID-19 outbreak at a long-term care facility.

Washington state officials reported two other presumptive positive cases of COVID-19, both of whom are associated with LifeCare of Kirkland, Washington. One is a woman in her 70s who is a resident at the facility and the other is a woman in her 40s who is a health care worker at the facility.

Additionally, many residents and staff members at the facility have reported respiratory symptoms, according to Jeff Duchin, MD, health officer for public health in Seattle and King County. Among the more than 100 residents at the facility, 27 have respiratory symptoms; while among the 180 staff members, 25 have reported symptoms.

Overall, these reports bring the total number of U.S. COVID-19 cases detected by the public health system to 22, though that number is expected to climb as these investigations continue.

The general risk to the American public is still low, including residents in long-term care facilities, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during the Feb. 29 press briefing. Older people are are higher risk, however, and long-term care facilities should emphasize handwashing and the early identification of individuals with symptoms.

Dr. Duchin added that health care workers who are sick should stay home and that visitors should be screened for symptoms, the same advice offered to limit the spread of influenza at long-term care facilities.

The CDC briefing comes after President Trump held his own press conference at the White House where he identified the person who had died as being a woman in her 50s who was medically at risk.

During that press conference, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that the current pattern of disease with COVID-19 suggests that 75%-80% of patients will have mild illness and recover, while 15%-20% will require advanced medical care.

For the most part, the more serious cases will occur in those who are elderly or have underlying medical conditions. There is “no indication” that individuals who recover from the virus are becoming re-infected, Dr. Fauci said.

The administration also announced a series of actions aimed at slowing the spread of the virus and responding to it. On March 2, President Trump will meet with leaders in the pharmaceutical industry at the White House to discuss vaccine development. The administration is also working to ensure an adequate supply of face masks. Vice President Mike Pence said there are currently more than 40 million masks available, but that the administration has received promises of 35 million more masks per month from manufacturers. Access to masks will be prioritized for high-risk health care workers, Vice President Pence said. “The average American does not need to go out and buy a mask,” he added.

Additionally, Vice President Pence announced new travel restrictions with Iran that would bar entry to the United States for any foreign national who visited Iran in the last 14 days. The federal government is also advising Americans not to travel to the regions in Italy and South Korea that have been most affected by COVID-19. The government is also working with officials in Italy and South Korea to conduct medical screening of anyone coming into the United States from those countries.

CDC revises COVID-19 test kits, broadens ‘person under investigation’ definition

In a telebriefing on the COVID-19 outbreak, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at .

The definition has been revised “to meet the needs of this rapidly evolving situation,” she said. The new PUI definition includes travel to more geographic areas to reflect this past week’s marked uptick in coronavirus activity in Italy and Iran. In addition to these countries and China, recent travel to Japan or South Korea also constitutes an epidemiologic risk factor which, in conjunction with clinical features, warrant an individual being classified as a PUI. These five countries each now have widespread person-to-person transmission of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier left open the possibility that the PUI definition would continue to evolve if such transmission within communities becomes more common. Asked whether the small number of U.S. cases thus might be an artifact of low test volumes, she said, “We aggressively controlled our borders to slow the spread. This was an intentional U.S. strategy. The CDC has always had the capacity to test rapidly from the time the sequence was available. ...We have been testing aggressively.”

The original PUI definition, she explained, emphasized individuals with fever, cough, or trouble breathing who had traveled recently from areas with COVID-19 activity, in particular China’s Hubei province. “We have been most focused on symptomatic people who are closely linked to, or who had, travel history, but our criteria also allow for clinical discretion,” she said. “There is no substitute for an astute clinician on the front lines of patient care.”

The first COVID-19 case from person-to-person spread was reported on Feb. 27. “At this time, we don’t know how or where this person became infected,” said Dr. Messonnier, although investigations are still underway. She responded to a question about whether the CDC delayed allowing COVID-19 testing for the patient for several days, as was reported in some media accounts. “According to CDC records, the first call we got was Feb. 23,” when public health officials in California reported a severely ill person with no travel abroad and no known contacts with individuals that would trigger suspicions for coronavirus. The CDC recommended COVID-19 testing on that day, she said.

Dr. Messonnier declined to answer questions about a whistleblower report alleging improper training and inadequate protective measures for Department of Health & Human Services workers at the quarantine center at Travis Air Force Base, Calif.

Dr. Messonnier said that the CDC has been working closely with the Food and Drug Administration to address problems with the COVID-19 test kits that were unusable because of a large number of indeterminate results. The two agencies together have determined that of the three reactions that were initially deemed necessary for a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis, just two are sufficient, so new kits that omit the problematic chemical are being manufactured and distributed.

These new kits are rapidly being made available; the goal, said Dr. Messonnier, is to have to state and local public health departments equipped with test kits by about March 7.

As local tests become available, the most updated information will be coming from state and local public health departments, she stressed, adding that the CDC would continue to update case counts on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of each week. Procedures are being developed for the management of patients presumed to have COVID-19, where local health departments see positive tests but the mandatory CDC confirmatory test hasn’t been completed.

While new cases emerge across Europe and Asia, China’s earlier COVID-19 explosion seems to be slowing. “It’s really good news that the case counts in China are decreasing,” both for the well-being of that country’s citizens, and as a sign of the disease’s potential global effects, said Dr. Messonnier. She added that epidemiologists and mathematical modelers are parsing case fatality rates as well.

She advised health care providers and public health officials to keep abreast of changes in CDC guidance by checking frequently at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

In a telebriefing on the COVID-19 outbreak, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at .

The definition has been revised “to meet the needs of this rapidly evolving situation,” she said. The new PUI definition includes travel to more geographic areas to reflect this past week’s marked uptick in coronavirus activity in Italy and Iran. In addition to these countries and China, recent travel to Japan or South Korea also constitutes an epidemiologic risk factor which, in conjunction with clinical features, warrant an individual being classified as a PUI. These five countries each now have widespread person-to-person transmission of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier left open the possibility that the PUI definition would continue to evolve if such transmission within communities becomes more common. Asked whether the small number of U.S. cases thus might be an artifact of low test volumes, she said, “We aggressively controlled our borders to slow the spread. This was an intentional U.S. strategy. The CDC has always had the capacity to test rapidly from the time the sequence was available. ...We have been testing aggressively.”

The original PUI definition, she explained, emphasized individuals with fever, cough, or trouble breathing who had traveled recently from areas with COVID-19 activity, in particular China’s Hubei province. “We have been most focused on symptomatic people who are closely linked to, or who had, travel history, but our criteria also allow for clinical discretion,” she said. “There is no substitute for an astute clinician on the front lines of patient care.”

The first COVID-19 case from person-to-person spread was reported on Feb. 27. “At this time, we don’t know how or where this person became infected,” said Dr. Messonnier, although investigations are still underway. She responded to a question about whether the CDC delayed allowing COVID-19 testing for the patient for several days, as was reported in some media accounts. “According to CDC records, the first call we got was Feb. 23,” when public health officials in California reported a severely ill person with no travel abroad and no known contacts with individuals that would trigger suspicions for coronavirus. The CDC recommended COVID-19 testing on that day, she said.

Dr. Messonnier declined to answer questions about a whistleblower report alleging improper training and inadequate protective measures for Department of Health & Human Services workers at the quarantine center at Travis Air Force Base, Calif.

Dr. Messonnier said that the CDC has been working closely with the Food and Drug Administration to address problems with the COVID-19 test kits that were unusable because of a large number of indeterminate results. The two agencies together have determined that of the three reactions that were initially deemed necessary for a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis, just two are sufficient, so new kits that omit the problematic chemical are being manufactured and distributed.

These new kits are rapidly being made available; the goal, said Dr. Messonnier, is to have to state and local public health departments equipped with test kits by about March 7.

As local tests become available, the most updated information will be coming from state and local public health departments, she stressed, adding that the CDC would continue to update case counts on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of each week. Procedures are being developed for the management of patients presumed to have COVID-19, where local health departments see positive tests but the mandatory CDC confirmatory test hasn’t been completed.

While new cases emerge across Europe and Asia, China’s earlier COVID-19 explosion seems to be slowing. “It’s really good news that the case counts in China are decreasing,” both for the well-being of that country’s citizens, and as a sign of the disease’s potential global effects, said Dr. Messonnier. She added that epidemiologists and mathematical modelers are parsing case fatality rates as well.

She advised health care providers and public health officials to keep abreast of changes in CDC guidance by checking frequently at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

In a telebriefing on the COVID-19 outbreak, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at .

The definition has been revised “to meet the needs of this rapidly evolving situation,” she said. The new PUI definition includes travel to more geographic areas to reflect this past week’s marked uptick in coronavirus activity in Italy and Iran. In addition to these countries and China, recent travel to Japan or South Korea also constitutes an epidemiologic risk factor which, in conjunction with clinical features, warrant an individual being classified as a PUI. These five countries each now have widespread person-to-person transmission of the virus.

Dr. Messonnier left open the possibility that the PUI definition would continue to evolve if such transmission within communities becomes more common. Asked whether the small number of U.S. cases thus might be an artifact of low test volumes, she said, “We aggressively controlled our borders to slow the spread. This was an intentional U.S. strategy. The CDC has always had the capacity to test rapidly from the time the sequence was available. ...We have been testing aggressively.”

The original PUI definition, she explained, emphasized individuals with fever, cough, or trouble breathing who had traveled recently from areas with COVID-19 activity, in particular China’s Hubei province. “We have been most focused on symptomatic people who are closely linked to, or who had, travel history, but our criteria also allow for clinical discretion,” she said. “There is no substitute for an astute clinician on the front lines of patient care.”

The first COVID-19 case from person-to-person spread was reported on Feb. 27. “At this time, we don’t know how or where this person became infected,” said Dr. Messonnier, although investigations are still underway. She responded to a question about whether the CDC delayed allowing COVID-19 testing for the patient for several days, as was reported in some media accounts. “According to CDC records, the first call we got was Feb. 23,” when public health officials in California reported a severely ill person with no travel abroad and no known contacts with individuals that would trigger suspicions for coronavirus. The CDC recommended COVID-19 testing on that day, she said.

Dr. Messonnier declined to answer questions about a whistleblower report alleging improper training and inadequate protective measures for Department of Health & Human Services workers at the quarantine center at Travis Air Force Base, Calif.

Dr. Messonnier said that the CDC has been working closely with the Food and Drug Administration to address problems with the COVID-19 test kits that were unusable because of a large number of indeterminate results. The two agencies together have determined that of the three reactions that were initially deemed necessary for a definitive COVID-19 diagnosis, just two are sufficient, so new kits that omit the problematic chemical are being manufactured and distributed.

These new kits are rapidly being made available; the goal, said Dr. Messonnier, is to have to state and local public health departments equipped with test kits by about March 7.

As local tests become available, the most updated information will be coming from state and local public health departments, she stressed, adding that the CDC would continue to update case counts on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of each week. Procedures are being developed for the management of patients presumed to have COVID-19, where local health departments see positive tests but the mandatory CDC confirmatory test hasn’t been completed.

While new cases emerge across Europe and Asia, China’s earlier COVID-19 explosion seems to be slowing. “It’s really good news that the case counts in China are decreasing,” both for the well-being of that country’s citizens, and as a sign of the disease’s potential global effects, said Dr. Messonnier. She added that epidemiologists and mathematical modelers are parsing case fatality rates as well.

She advised health care providers and public health officials to keep abreast of changes in CDC guidance by checking frequently at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

REPORTING FROM A CDC BRIEFING

Children bearing the brunt of declining flu activity

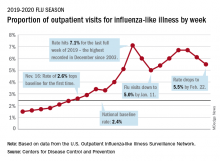

National flu activity decreased for the second consecutive week, but pediatric mortality is heading in the opposite direction, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza-like illness (ILI) represented 5.5% of all visits to outpatient health care providers during the week ending Feb. 22, compared with 6.1% the previous week, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 28. The ILI visit rate had reached 6.6% in early February after dropping to 5.0% in mid-January, following a rise to a season-high 7.1% in the last week of December.

Another measure of ILI activity, the percentage of laboratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the second week in a row. The rate was 26.4% for the week ending Feb. 22, which is down from the season high of 30.3% reached 2 weeks before, the influenza division said.

ILI-related deaths among children, however, are not dropping. The total for 2019-2020 is now up to 125, and that “number is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Hospitalization rates, which have been fairly typical in the general population, also are elevated for young adults and school-aged children, the agency said, and “rates among children 0-4 years old are now the highest CDC has on record at this point in the season, surpassing rates reported during the second wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.”

National flu activity decreased for the second consecutive week, but pediatric mortality is heading in the opposite direction, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza-like illness (ILI) represented 5.5% of all visits to outpatient health care providers during the week ending Feb. 22, compared with 6.1% the previous week, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 28. The ILI visit rate had reached 6.6% in early February after dropping to 5.0% in mid-January, following a rise to a season-high 7.1% in the last week of December.

Another measure of ILI activity, the percentage of laboratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the second week in a row. The rate was 26.4% for the week ending Feb. 22, which is down from the season high of 30.3% reached 2 weeks before, the influenza division said.

ILI-related deaths among children, however, are not dropping. The total for 2019-2020 is now up to 125, and that “number is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Hospitalization rates, which have been fairly typical in the general population, also are elevated for young adults and school-aged children, the agency said, and “rates among children 0-4 years old are now the highest CDC has on record at this point in the season, surpassing rates reported during the second wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.”

National flu activity decreased for the second consecutive week, but pediatric mortality is heading in the opposite direction, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza-like illness (ILI) represented 5.5% of all visits to outpatient health care providers during the week ending Feb. 22, compared with 6.1% the previous week, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 28. The ILI visit rate had reached 6.6% in early February after dropping to 5.0% in mid-January, following a rise to a season-high 7.1% in the last week of December.

Another measure of ILI activity, the percentage of laboratory specimens testing positive, also declined for the second week in a row. The rate was 26.4% for the week ending Feb. 22, which is down from the season high of 30.3% reached 2 weeks before, the influenza division said.

ILI-related deaths among children, however, are not dropping. The total for 2019-2020 is now up to 125, and that “number is higher for the same time period than in every season since reporting began in 2004-05, except for the 2009 pandemic,” the CDC noted.

Hospitalization rates, which have been fairly typical in the general population, also are elevated for young adults and school-aged children, the agency said, and “rates among children 0-4 years old are now the highest CDC has on record at this point in the season, surpassing rates reported during the second wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.”

What hospitalists need to know about COVID-19

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

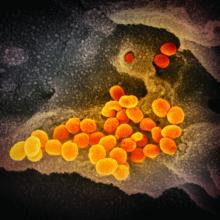

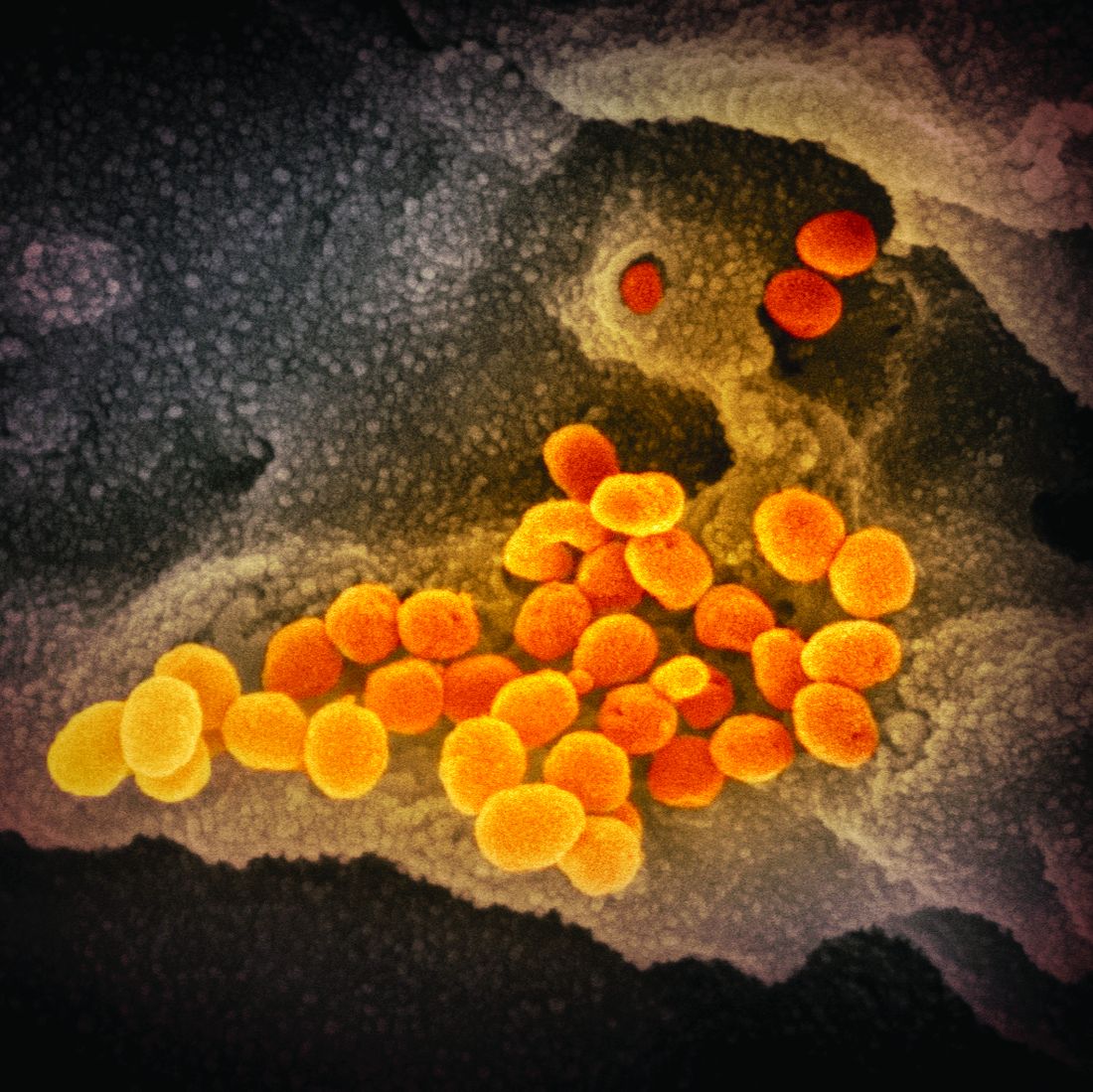

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?

CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a face mask to protect themselves from respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. A face mask should be used by people who have COVID-19 and are showing symptoms to protect others from the risk of getting infected.

Should medical waste or general waste from health care facilities treating PUIs and patients with confirmed COVID-19 be handled any differently or need any additional disinfection?

No. CDC’s guidance states that management of laundry, food service utensils, and medical waste should be performed in accordance with routine procedures.

Can people who recover from COVID-19 be infected again?

Unknown. The immune response to COVID-19 is not yet understood.

What is the mortality rate of COVID-19, and how does it compare to the mortality rate of influenza (flu)?

The average 10-year mortality rate for flu, using CDC data, is found to be around 0.1%. Even though this percentage appears to be small, influenza is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 to 40,000 deaths annually in the U.S.

According to statistics released by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Feb. 17, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is estimated to be around 2.3%. This calculation was based on cases reported through Feb. 11, and calcuated by dividing the number of coronavirus-related deaths at the time (1,023) by the number of confirmed cases (44,672) of COVID-19 infection. However, this report has its limitations, since Chinese officials have a vague way of defining who has COVID-19 infection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the mortality rate for COVID-19 to be between 2% and 4%.

Dr. Sitammagari is a co-medical director for quality and assistant professor of internal medicine at Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. He is also a physician advisor. He currently serves as treasurer for the NC-Triangle Chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine and as an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Skandhan is a hospitalist and member of the Core Faculty for the Internal Medicine Residency Program at Southeast Health (SEH), Dothan Ala., and an assistant professor at the Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine. He serves as the medical director/physician liaison for the Clinical Documentation Program at SEH and also as the director for physician integration for Southeast Health Statera Network, an Accountable Care Organization. Dr. Skandhan was a cofounder of the Wiregrass chapter of SHM and currently serves on the Advisory board. He is also a member of the editorial board of The Hospitalist.

Dr. Dahlin is a second-year internal medicine resident at Southeast Health, Dothan, Ala. She serves as her class representative and is the cochair/resident liaison for the research committee at SEH. Dr. Dahlin also serves as a resident liaison for the Wiregrass chapter of SHM.

This article last updated 4/8/20. (Disclaimer: The information in this article may not be updated regularly. For more COVID-19 coverage, bookmark our COVID-19 updates page. The editors of The Hospitalist encourage clinicians to also review information on the CDC website and on the AHA website.)

An infectious disease outbreak that began in December 2019 in Wuhan (Hubei Province), China, was found to be caused by the seventh strain of coronavirus, initially called the novel (new) coronavirus. The virus was later labeled as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named COVID-19. Until 2019, only six strains of human coronaviruses had previously been identified.

As of April 8, 2020, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 has been detected in at least 209 countries and has spread to every contintent except Antarctica. More than 1,469,245 people have become infected globally, and at least 86,278 have died. Based on the cases detected and tested in the United States through the U.S. public health surveillance systems, we have had 406,693 confirmed cases and 13,089 deaths.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic.

As the number of cases increases in the United States, we hope to provide answers about some common questions regarding COVID-19. The information summarized in this article is obtained and modified from the CDC.

What are the clinical features of COVID-19?

Ranges from asymptomatic infection, a mild disease with nonspecific signs and symptoms of acute respiratory illness, to severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and septic shock.

Who is at risk for COVID-19?

Persons who have had prolonged, unprotected close contact with a patient with symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19, and those with recent travel to China, especially Hubei Province.

Who is at risk for severe disease from COVID-19?

Older adults and persons who have underlying chronic medical conditions, such as immunocompromising conditions.

How is COVID-19 spread?

Person-to-person, mainly through respiratory droplets. SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

When is someone infectious?

Incubation period may range from 2 to 14 days. Detection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present, as it may be detectable in the upper or lower respiratory tract for weeks after illness onset.

Can someone who has been quarantined for COVID-19 spread the illness to others?

For COVID-19, the period of quarantine is 14 days from the last date of exposure, because 14 days is the longest incubation period seen for similar coronaviruses. Someone who has been released from COVID-19 quarantine is not considered a risk for spreading the virus to others because they have not developed illness during the incubation period.

Can a person test negative and later test positive for COVID-19?

Yes. In the early stages of infection, it is possible the virus will not be detected.

Do patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 need to be admitted to the hospital?

Not all patients with COVID-19 require hospital admission. Patients whose clinical presentation warrants inpatient clinical management for supportive medical care should be admitted to the hospital under appropriate isolation precautions. The decision to monitor these patients in the inpatient or outpatient setting should be made on a case-by-case basis.

What should you do if you suspect a patient for COVID-19?

Immediately notify both infection control personnel at your health care facility and your local or state health department. State health departments that have identified a person under investigation (PUI) should immediately contact CDC’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100 and complete a COVID-19 PUI case investigation form.

CDC’s EOC will assist local/state health departments to collect, store, and ship specimens appropriately to CDC, including during after-hours or on weekends/holidays.

What type of isolation is needed for COVID-19?

Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) using Standard, Contact, and Airborne Precautions with eye protection.

How should health care personnel protect themselves when evaluating a patient who may have COVID-19?

Standard Precautions, Contact Precautions, Airborne Precautions, and use eye protection (e.g., goggles or a face shield).

What face mask do health care workers wear for respiratory protection?

A fit-tested NIOSH-certified disposable N95 filtering facepiece respirator should be worn before entry into the patient room or care area. Disposable respirators should be removed and discarded after exiting the patient’s room or care area and closing the door. Perform hand hygiene after discarding the respirator.

If reusable respirators (e.g., powered air purifying respirator/PAPR) are used, they must be cleaned and disinfected according to manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions prior to re-use.

What should you tell the patient if COVID-19 is suspected or confirmed?

Patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be asked to wear a surgical mask as soon as they are identified, to prevent spread to others.

Should any diagnostic or therapeutic interventions be withheld because of concerns about the transmission of COVID-19?

No.

How do you test a patient for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

At this time, diagnostic testing for COVID-19 can be conducted only at CDC.

The CDC recommends collecting and testing multiple clinical specimens from different sites, including two specimen types – lower respiratory and upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, bronchioalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) using a real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified regardless of the time of symptom onset. Turnaround time for the PCR assay testing is about 24-48 hours.

Testing for other respiratory pathogens should not delay specimen shipping to CDC. If a PUI tests positive for another respiratory pathogen, after clinical evaluation and consultation with public health authorities, they may no longer be considered a PUI.

Will existing respiratory virus panels detect SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19?

No.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Symptomatic management. Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended for viral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and should be avoided unless they are indicated for another reason (e.g., COPD exacerbation, refractory septic shock following Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines). There are currently no antiviral drugs licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat COVID-19.

What is considered ‘close contact’ for health care exposures?

Being within approximately 6 feet (2 meters), of a person with COVID-19 for a prolonged period of time (such as caring for or visiting the patient, or sitting within 6 feet of the patient in a health care waiting area or room); or having unprotected direct contact with infectious secretions or excretions of the patient (e.g., being coughed on, touching used tissues with a bare hand). However, until more is known about transmission risks, it would be reasonable to consider anything longer than a brief (e.g., less than 1-2 minutes) exposure as prolonged.

What happens if the health care personnel (HCP) are exposed to confirmed COVID-19 patients? What’s the protocol for HCP exposed to persons under investigation (PUI) if test results are delayed beyond 48-72 hours?

Management is similar in both these scenarios. CDC categorized exposures as high, medium, low, and no identifiable risk. High- and medium-risk exposures are managed similarly with active monitoring for COVID-19 until 14 days after last potential exposure and exclude from work for 14 days after last exposure. Active monitoring means that the state or local public health authority assumes responsibility for establishing regular communication with potentially exposed people to assess for the presence of fever or respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, shortness of breath, sore throat). For HCP with high- or medium-risk exposures, CDC recommends this communication occurs at least once each day. For full details, please see www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html.

Should postexposure prophylaxis be used for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19?

None available.

COVID-19 test results are negative in a symptomatic patient you suspected of COVID-19? What does it mean?

A negative test result for a sample collected while a person has symptoms likely means that the COVID-19 virus is not causing their current illness.

What if your hospital does not have an Airborne Infection Isolation Room (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Transfer the patient to a facility that has an available AIIR. If a transfer is impractical or not medically appropriate, the patient should be cared for in a single-person room and the door should be kept closed. The room should ideally not have an exhaust that is recirculated within the building without high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Health care personnel should still use gloves, gown, respiratory and eye protection and follow all other recommended infection prevention and control practices when caring for these patients.

What if your hospital does not have enough Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIR) for COVID-19 patients?

Prioritize patients for AIIR who are symptomatic with severe illness (e.g., those requiring ventilator support).

When can patients with confirmed COVID-19 be discharged from the hospital?

Patients can be discharged from the health care facility whenever clinically indicated. Isolation should be maintained at home if the patient returns home before the time period recommended for discontinuation of hospital transmission-based precautions.

Considerations to discontinue transmission-based precautions include all of the following:

- Resolution of fever, without the use of antipyretic medication.

- Improvement in illness signs and symptoms.

- Negative rRT-PCR results from at least two consecutive sets of paired nasopharyngeal and throat swabs specimens collected at least 24 hours apart (total of four negative specimens – two nasopharyngeal and two throat) from a patient with COVID-19 are needed before discontinuing transmission-based precautions.

Should people be concerned about pets or other animals and COVID-19?

To date, CDC has not received any reports of pets or other animals becoming sick with COVID-19.

Should patients avoid contact with pets or other animals if they are sick with COVID-19?

Patients should restrict contact with pets and other animals while they are sick with COVID-19, just like they would around other people.

Does CDC recommend the use of face masks in the community to prevent COVID-19?