User login

Mysterious vaping lung injuries may have flown under regulatory radar

It was the arrival of the second man in his early 20s gasping for air that alarmed Dixie Harris, MD. Young patients rarely get so sick, so fast, with a severe lung illness, and this was her second case in a matter of days.

Then she saw three more patients at her Utah telehealth clinic with similar symptoms. They did not have infections, but all had been vaping. When Dr. Harris heard several teenagers in Wisconsin had been hospitalized in similar cases, she quickly alerted her state health department.

As patients in hospitals across the country combat a mysterious illness linked to e-cigarettes, federal and state investigators are frantically trying to trace the outbreaks to specific vaping products that, until recently, were virtually unregulated.

As of Aug. 22, 2019, 193 potential vaping-related illnesses in 22 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wisconsin, which first put out an alert in July, has at least 16 confirmed and 15 suspected cases. Illinois has reported 34 patients, 1 of whom has died. Indiana is investigating 24 cases.

Lung doctors said they had seen warning signs for years that vaping could be hazardous as they treated patients. Medically it seemed problematic since it often involved inhaling chemicals not normally inhaled into the lungs. Despite that, assessing the safety of a new product storming the market fell between regulatory cracks, leaving doctors unsure where to register concerns before the outbreak. The Food and Drug Administration took years to regulate e-cigarettes once a court determined it had the authority to do so.

“You don’t know what you’re putting into your lungs when you vape,” said Dr. Harris, a critical care pulmonologist. “It’s purported to be safe, but how do you know if it’s safe? To me, it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Off the radar

When e-cigarettes came to market about a decade ago, they fell into a regulatory no man’s land. They are not a food, not a drug, and not a medical device, any of which would have put them immediately in the FDA’s purview. And, until a few years ago, they weren’t even lumped in with tobacco products.

As a result, billions of dollars of vaping products have been sold online, at big-box retailers, and in corner stores without going through the FDA’s rigorous review process to assess their safety. Companies like Juul, Blu, and NJoy quickly established their brands of devices and cartridges, or pods. And thousands of related products are sold, sometimes on the black market, over the Internet, or beyond.

“It makes it really tough because we don’t know what we’re looking for,” said Ruth Lynfield, MD, the state epidemiologist for Minnesota, where several patients were admitted to the ICU as a result of the illness. She added that, if it turns out that the products in question were sold by unregistered retailers and manufacturers “on the street,” outbreak sleuths will have a harder time figuring out exactly what is in them.

With e-cigarettes, people can vape – or smoke – nicotine products, selecting flavorings like mint, mango, blueberry crème brûlée, or cookies and milk. They can also inhale cannabis products. Many are hopeful that e-cigarettes might be useful smoking cessation tools, but some research has called that into question.

The mysterious pulmonary disease cases have been linked to vaping, but it’s unclear whether there is a common device or chemical. In some states, including California and Utah, all of the patients had vaped cannabis products. One or more substances could be involved, health officials have said. The products used by several victims are being tested to see what they contained.

And this has apparently been the case for years.

Multiple doctors described seeing earlier cases of severe lung problems linked to vaping that were not officially reported or included in the current CDC count.

Laura Crotty Alexander, MD, a pulmonologist and researcher with the University of California, San Diego, said she saw her first case about 2 years ago. A young man had been vaping for months with the same device but developed acute lung injury when he switched flavors. She strongly suspected a link, but did not report the illness anywhere.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t want to report it, it’s that there’s no pathway” to do so, Dr. Alexander said.

She said she’s concerned that many physicians haven’t been asking patients about e-cigarette use and that there’s no way to document a case like this in the medical coding system.

John E. Parker, MD, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, said he saw his first patient with pneumonia tied to vaping in 2015. Doctors there were intrigued enough to report on the case at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Parker and his team didn’t contact a federal agency, and Dr. Parker said it was unclear whom to call.

Numerous other cases have been reported in medical journals and at professional conferences in the years since. The FDA’s voluntary system for reporting tobacco-related health problems included 96 seizures and only 1 lung ailment tied to e-cigarettes between April and June 2019. The system appears to be utilized most by concerned citizens, rather than manufacturers or health care professionals.

But several lung specialists said that due to the patchwork nature of regulatory oversight over the years, the true scope of the problem is yet to be identified.

“We do know that e-cigarettes do not emit a harmless aerosol,” said Brian King, PhD, MPH, a deputy director in the Office on Smoking and Health at the CDC in a call with media on Aug. 23 about the outbreak. “It is possible that some of these cases were already occurring but we were not picking them up.”

Regulatory limits

The FDA has had limited authority to regulate e-cigarettes over the years.

In 2009, Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, empowering the FDA to oversee the safety and sale of tobacco products. But e-cigarettes, still new, were not top of mind.

Later that year, the FDA tried to block imports of e-cigarettes, saying the combination drug-device products were unapproved and therefore illegal for sale in the United States. Two vaping companies, Smoking Everywhere and NJoy, sued, and a federal judge ruled in 2010 that the FDA should regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products.

It took the agency 6 years to finalize what’s become known as the “deeming rule,” in which it formally began regulating e-cigarettes and e-liquids.

By then, it was May 2016, and the e-cigarette market had swelled to an estimated $4.1 billion, Wells Fargo Securities analyst Bonnie Herzog said at the time. Market researchers now project that the global industry could reach $48 billion by 2023.

Critics say the FDA took too long to act.

“I think the fact that FDA has been dillydallying [has made] figuring out what’s going on [with this outbreak] much harder,” said Stanton Glantz, PhD, a University of California, San Francisco, professor in its Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. “No question.”

The agency began by banning e-cigarette sales to minors and requiring all new vaping products to submit applications for authorization before they could come to market. Companies and retailers with thousands of products already on the market were granted 2 years to submit applications, and the FDA would get an additional year to evaluate the applications. Meanwhile, existing products could still be sold.

But when Scott Gottlieb, MD, arrived as the new FDA commissioner in 2017, the rule hadn’t been implemented and there was no formal guidance for companies to file applications, he said. As a result, he pushed the deadline back to 2022, drawing ire from public health advocates, who called foul over his previous ties to an e-cigarette retailer called Kure.

“I thought e-cigarettes at the time – and I still believe – that they represent an opportunity for currently addicted adult smokers to transition off of combustible tobacco,” he said in an interview, adding that other parts of the deeming rule went into effect as planned. “All I did was delay the application deadline.”

Dr. Gottlieb’s thinking changed the following year, when a national survey showed a sharp rise in teen vaping, which he called an “epidemic.” He announced that the agency would rethink the extended deadline and weigh whether to take flavors that appeal to kids off the market.

A judge ruled last month that e-cigarette makers would have only 10 more months to submit applications to the FDA. They’re now due in May 2020.

Asked about the lung injuries appearing now, Dr. Gottlieb, who left the FDA in April 2019, said he suspected counterfeit pods are to blame, given the geographic clustering of cases and the fact that, overall, the FDA is inspecting registered e-cigarette makers and retailers to make sure they’re complying with existing regulations.

“I think the manufacturers are culpable if their products are being used, whether the liquids are counterfeit or real,” he said. “Ultimately, they’re responsible for keeping their products out of the hands of kids.”

Juul, the leading e-cigarette maker, agreed that children shouldn’t be able to vape its products, and said curtailing access should be done “through significant regulation” and “enforcement.”

“When people say ‘Why aren’t these being regulated?’ They actually are all being regulated,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

For example, companies are required to label their products as potentially addictive, sell only to adults and comply with manufacturing standards. The agency has conducted thousands of inspections of e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers and taken enforcement actions against companies selling e-cigarettes that look like juice boxes, and against a company that was putting the ingredients found in erectile dysfunction drugs into its vape liquid.

Health departments investigating the outbreak told Kaiser Health News that e-cigarettes’ niche as a tobacco product instead of a drug has presented challenges. Most weren’t aware that adverse events could be reported to a database that tracks problems with tobacco products. And, because e-cigarettes never went through the FDA’s “gold-standard” approval process for drugs, doctors can’t readily look up a detailed list of known side effects.

But like other arms of the FDA, the tobacco office has tools and a team to investigate a public health threat just as the teams for drugs and devices do, Dr. Gottlieb said. It may even be better equipped because of its funding.

“I don’t think FDA is operating in any way with hands tied behind its back because of the way that the statute is set up,” he said.

Teen vaping has exploded during this regulatory tussle. In 2011, 1.5% of high school students reported vaping. By 2018, it was 20.8%, according to a CDC report.

Unknown components

Still, doctors and researchers are concerned about the ingredients in e-cigarettes and how little the public knows about the risks of vaping.

In Juul’s terms and conditions, posted on its website, it says, “We encourage consumers to do their own research regarding vapor products and what is right for them.” Many ingredients in e-cigarette products, however, are protected as trade secrets.

Since at least 2013, the flavor industry has expressed concern about the use of flavoring chemicals in vaping products.

The vast majority of the chemicals have been tested only by ingesting them in small quantities because they’re encountered in foods. For most of these chemicals, there have been no tests to determine whether it is safe to inhale them, as happens daily by millions when they use e-cigarettes.

“Many of the ingredients of vaping products, including flavoring substances, have not been tested for … the exposure one would get from using a vaping device,” said John Hallagan, a senior adviser to the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association. The group has sent cease-and-desist letters to e-cigarette companies in previous years for using the food safety certification of the flavor industry to imply that the chemicals are also safe in e-cigarettes.

Some flavor chemicals are thought to be harmful when inhaled in high doses. Research suggests that cinnamaldehyde, the main component of many cinnamon flavors, may impair lung function when inhaled. Sven-Eric Jordt, PhD, a professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., says he presented evidence of its dangers at an FDA meeting in 2015 — and its relative abundance in many e-cigarette vaping liquids. In response, one major e-cigarette liquid seller, Tasty Vapor, voluntarily took its cinnamon-flavored liquid off the shelves.

In 2017, when Dr. Gottlieb delayed the FDA application deadline, the product was back. A company email to its customers put it this way: “Two years ago, Tasty Vapor allowed itself to be intimidated by scaremongering tactics. … We lost a lot of sales as well as a good number of long-time customers. We no long see reason to disappoint our customers hostage for these shady tactics.”

At the time of publication, Tasty Vapor’s owner did not reply to a request for comment.

Dr. Jordt said he is frustrated by the delays in the regulatory approval process.

“As a parent, I would say that the government has not acted on this,” he said. “You’re basically left to act alone with your addicted kid. It’s kind of terrifying that this was allowed to happen. The industry needs to be held to account.”

Kaiser Health News correspondents Cara Anthony, Markian Hawryluk, and Lauren Weber, as well as reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. This story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

It was the arrival of the second man in his early 20s gasping for air that alarmed Dixie Harris, MD. Young patients rarely get so sick, so fast, with a severe lung illness, and this was her second case in a matter of days.

Then she saw three more patients at her Utah telehealth clinic with similar symptoms. They did not have infections, but all had been vaping. When Dr. Harris heard several teenagers in Wisconsin had been hospitalized in similar cases, she quickly alerted her state health department.

As patients in hospitals across the country combat a mysterious illness linked to e-cigarettes, federal and state investigators are frantically trying to trace the outbreaks to specific vaping products that, until recently, were virtually unregulated.

As of Aug. 22, 2019, 193 potential vaping-related illnesses in 22 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wisconsin, which first put out an alert in July, has at least 16 confirmed and 15 suspected cases. Illinois has reported 34 patients, 1 of whom has died. Indiana is investigating 24 cases.

Lung doctors said they had seen warning signs for years that vaping could be hazardous as they treated patients. Medically it seemed problematic since it often involved inhaling chemicals not normally inhaled into the lungs. Despite that, assessing the safety of a new product storming the market fell between regulatory cracks, leaving doctors unsure where to register concerns before the outbreak. The Food and Drug Administration took years to regulate e-cigarettes once a court determined it had the authority to do so.

“You don’t know what you’re putting into your lungs when you vape,” said Dr. Harris, a critical care pulmonologist. “It’s purported to be safe, but how do you know if it’s safe? To me, it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Off the radar

When e-cigarettes came to market about a decade ago, they fell into a regulatory no man’s land. They are not a food, not a drug, and not a medical device, any of which would have put them immediately in the FDA’s purview. And, until a few years ago, they weren’t even lumped in with tobacco products.

As a result, billions of dollars of vaping products have been sold online, at big-box retailers, and in corner stores without going through the FDA’s rigorous review process to assess their safety. Companies like Juul, Blu, and NJoy quickly established their brands of devices and cartridges, or pods. And thousands of related products are sold, sometimes on the black market, over the Internet, or beyond.

“It makes it really tough because we don’t know what we’re looking for,” said Ruth Lynfield, MD, the state epidemiologist for Minnesota, where several patients were admitted to the ICU as a result of the illness. She added that, if it turns out that the products in question were sold by unregistered retailers and manufacturers “on the street,” outbreak sleuths will have a harder time figuring out exactly what is in them.

With e-cigarettes, people can vape – or smoke – nicotine products, selecting flavorings like mint, mango, blueberry crème brûlée, or cookies and milk. They can also inhale cannabis products. Many are hopeful that e-cigarettes might be useful smoking cessation tools, but some research has called that into question.

The mysterious pulmonary disease cases have been linked to vaping, but it’s unclear whether there is a common device or chemical. In some states, including California and Utah, all of the patients had vaped cannabis products. One or more substances could be involved, health officials have said. The products used by several victims are being tested to see what they contained.

And this has apparently been the case for years.

Multiple doctors described seeing earlier cases of severe lung problems linked to vaping that were not officially reported or included in the current CDC count.

Laura Crotty Alexander, MD, a pulmonologist and researcher with the University of California, San Diego, said she saw her first case about 2 years ago. A young man had been vaping for months with the same device but developed acute lung injury when he switched flavors. She strongly suspected a link, but did not report the illness anywhere.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t want to report it, it’s that there’s no pathway” to do so, Dr. Alexander said.

She said she’s concerned that many physicians haven’t been asking patients about e-cigarette use and that there’s no way to document a case like this in the medical coding system.

John E. Parker, MD, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, said he saw his first patient with pneumonia tied to vaping in 2015. Doctors there were intrigued enough to report on the case at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Parker and his team didn’t contact a federal agency, and Dr. Parker said it was unclear whom to call.

Numerous other cases have been reported in medical journals and at professional conferences in the years since. The FDA’s voluntary system for reporting tobacco-related health problems included 96 seizures and only 1 lung ailment tied to e-cigarettes between April and June 2019. The system appears to be utilized most by concerned citizens, rather than manufacturers or health care professionals.

But several lung specialists said that due to the patchwork nature of regulatory oversight over the years, the true scope of the problem is yet to be identified.

“We do know that e-cigarettes do not emit a harmless aerosol,” said Brian King, PhD, MPH, a deputy director in the Office on Smoking and Health at the CDC in a call with media on Aug. 23 about the outbreak. “It is possible that some of these cases were already occurring but we were not picking them up.”

Regulatory limits

The FDA has had limited authority to regulate e-cigarettes over the years.

In 2009, Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, empowering the FDA to oversee the safety and sale of tobacco products. But e-cigarettes, still new, were not top of mind.

Later that year, the FDA tried to block imports of e-cigarettes, saying the combination drug-device products were unapproved and therefore illegal for sale in the United States. Two vaping companies, Smoking Everywhere and NJoy, sued, and a federal judge ruled in 2010 that the FDA should regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products.

It took the agency 6 years to finalize what’s become known as the “deeming rule,” in which it formally began regulating e-cigarettes and e-liquids.

By then, it was May 2016, and the e-cigarette market had swelled to an estimated $4.1 billion, Wells Fargo Securities analyst Bonnie Herzog said at the time. Market researchers now project that the global industry could reach $48 billion by 2023.

Critics say the FDA took too long to act.

“I think the fact that FDA has been dillydallying [has made] figuring out what’s going on [with this outbreak] much harder,” said Stanton Glantz, PhD, a University of California, San Francisco, professor in its Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. “No question.”

The agency began by banning e-cigarette sales to minors and requiring all new vaping products to submit applications for authorization before they could come to market. Companies and retailers with thousands of products already on the market were granted 2 years to submit applications, and the FDA would get an additional year to evaluate the applications. Meanwhile, existing products could still be sold.

But when Scott Gottlieb, MD, arrived as the new FDA commissioner in 2017, the rule hadn’t been implemented and there was no formal guidance for companies to file applications, he said. As a result, he pushed the deadline back to 2022, drawing ire from public health advocates, who called foul over his previous ties to an e-cigarette retailer called Kure.

“I thought e-cigarettes at the time – and I still believe – that they represent an opportunity for currently addicted adult smokers to transition off of combustible tobacco,” he said in an interview, adding that other parts of the deeming rule went into effect as planned. “All I did was delay the application deadline.”

Dr. Gottlieb’s thinking changed the following year, when a national survey showed a sharp rise in teen vaping, which he called an “epidemic.” He announced that the agency would rethink the extended deadline and weigh whether to take flavors that appeal to kids off the market.

A judge ruled last month that e-cigarette makers would have only 10 more months to submit applications to the FDA. They’re now due in May 2020.

Asked about the lung injuries appearing now, Dr. Gottlieb, who left the FDA in April 2019, said he suspected counterfeit pods are to blame, given the geographic clustering of cases and the fact that, overall, the FDA is inspecting registered e-cigarette makers and retailers to make sure they’re complying with existing regulations.

“I think the manufacturers are culpable if their products are being used, whether the liquids are counterfeit or real,” he said. “Ultimately, they’re responsible for keeping their products out of the hands of kids.”

Juul, the leading e-cigarette maker, agreed that children shouldn’t be able to vape its products, and said curtailing access should be done “through significant regulation” and “enforcement.”

“When people say ‘Why aren’t these being regulated?’ They actually are all being regulated,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

For example, companies are required to label their products as potentially addictive, sell only to adults and comply with manufacturing standards. The agency has conducted thousands of inspections of e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers and taken enforcement actions against companies selling e-cigarettes that look like juice boxes, and against a company that was putting the ingredients found in erectile dysfunction drugs into its vape liquid.

Health departments investigating the outbreak told Kaiser Health News that e-cigarettes’ niche as a tobacco product instead of a drug has presented challenges. Most weren’t aware that adverse events could be reported to a database that tracks problems with tobacco products. And, because e-cigarettes never went through the FDA’s “gold-standard” approval process for drugs, doctors can’t readily look up a detailed list of known side effects.

But like other arms of the FDA, the tobacco office has tools and a team to investigate a public health threat just as the teams for drugs and devices do, Dr. Gottlieb said. It may even be better equipped because of its funding.

“I don’t think FDA is operating in any way with hands tied behind its back because of the way that the statute is set up,” he said.

Teen vaping has exploded during this regulatory tussle. In 2011, 1.5% of high school students reported vaping. By 2018, it was 20.8%, according to a CDC report.

Unknown components

Still, doctors and researchers are concerned about the ingredients in e-cigarettes and how little the public knows about the risks of vaping.

In Juul’s terms and conditions, posted on its website, it says, “We encourage consumers to do their own research regarding vapor products and what is right for them.” Many ingredients in e-cigarette products, however, are protected as trade secrets.

Since at least 2013, the flavor industry has expressed concern about the use of flavoring chemicals in vaping products.

The vast majority of the chemicals have been tested only by ingesting them in small quantities because they’re encountered in foods. For most of these chemicals, there have been no tests to determine whether it is safe to inhale them, as happens daily by millions when they use e-cigarettes.

“Many of the ingredients of vaping products, including flavoring substances, have not been tested for … the exposure one would get from using a vaping device,” said John Hallagan, a senior adviser to the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association. The group has sent cease-and-desist letters to e-cigarette companies in previous years for using the food safety certification of the flavor industry to imply that the chemicals are also safe in e-cigarettes.

Some flavor chemicals are thought to be harmful when inhaled in high doses. Research suggests that cinnamaldehyde, the main component of many cinnamon flavors, may impair lung function when inhaled. Sven-Eric Jordt, PhD, a professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., says he presented evidence of its dangers at an FDA meeting in 2015 — and its relative abundance in many e-cigarette vaping liquids. In response, one major e-cigarette liquid seller, Tasty Vapor, voluntarily took its cinnamon-flavored liquid off the shelves.

In 2017, when Dr. Gottlieb delayed the FDA application deadline, the product was back. A company email to its customers put it this way: “Two years ago, Tasty Vapor allowed itself to be intimidated by scaremongering tactics. … We lost a lot of sales as well as a good number of long-time customers. We no long see reason to disappoint our customers hostage for these shady tactics.”

At the time of publication, Tasty Vapor’s owner did not reply to a request for comment.

Dr. Jordt said he is frustrated by the delays in the regulatory approval process.

“As a parent, I would say that the government has not acted on this,” he said. “You’re basically left to act alone with your addicted kid. It’s kind of terrifying that this was allowed to happen. The industry needs to be held to account.”

Kaiser Health News correspondents Cara Anthony, Markian Hawryluk, and Lauren Weber, as well as reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. This story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

It was the arrival of the second man in his early 20s gasping for air that alarmed Dixie Harris, MD. Young patients rarely get so sick, so fast, with a severe lung illness, and this was her second case in a matter of days.

Then she saw three more patients at her Utah telehealth clinic with similar symptoms. They did not have infections, but all had been vaping. When Dr. Harris heard several teenagers in Wisconsin had been hospitalized in similar cases, she quickly alerted her state health department.

As patients in hospitals across the country combat a mysterious illness linked to e-cigarettes, federal and state investigators are frantically trying to trace the outbreaks to specific vaping products that, until recently, were virtually unregulated.

As of Aug. 22, 2019, 193 potential vaping-related illnesses in 22 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wisconsin, which first put out an alert in July, has at least 16 confirmed and 15 suspected cases. Illinois has reported 34 patients, 1 of whom has died. Indiana is investigating 24 cases.

Lung doctors said they had seen warning signs for years that vaping could be hazardous as they treated patients. Medically it seemed problematic since it often involved inhaling chemicals not normally inhaled into the lungs. Despite that, assessing the safety of a new product storming the market fell between regulatory cracks, leaving doctors unsure where to register concerns before the outbreak. The Food and Drug Administration took years to regulate e-cigarettes once a court determined it had the authority to do so.

“You don’t know what you’re putting into your lungs when you vape,” said Dr. Harris, a critical care pulmonologist. “It’s purported to be safe, but how do you know if it’s safe? To me, it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Off the radar

When e-cigarettes came to market about a decade ago, they fell into a regulatory no man’s land. They are not a food, not a drug, and not a medical device, any of which would have put them immediately in the FDA’s purview. And, until a few years ago, they weren’t even lumped in with tobacco products.

As a result, billions of dollars of vaping products have been sold online, at big-box retailers, and in corner stores without going through the FDA’s rigorous review process to assess their safety. Companies like Juul, Blu, and NJoy quickly established their brands of devices and cartridges, or pods. And thousands of related products are sold, sometimes on the black market, over the Internet, or beyond.

“It makes it really tough because we don’t know what we’re looking for,” said Ruth Lynfield, MD, the state epidemiologist for Minnesota, where several patients were admitted to the ICU as a result of the illness. She added that, if it turns out that the products in question were sold by unregistered retailers and manufacturers “on the street,” outbreak sleuths will have a harder time figuring out exactly what is in them.

With e-cigarettes, people can vape – or smoke – nicotine products, selecting flavorings like mint, mango, blueberry crème brûlée, or cookies and milk. They can also inhale cannabis products. Many are hopeful that e-cigarettes might be useful smoking cessation tools, but some research has called that into question.

The mysterious pulmonary disease cases have been linked to vaping, but it’s unclear whether there is a common device or chemical. In some states, including California and Utah, all of the patients had vaped cannabis products. One or more substances could be involved, health officials have said. The products used by several victims are being tested to see what they contained.

And this has apparently been the case for years.

Multiple doctors described seeing earlier cases of severe lung problems linked to vaping that were not officially reported or included in the current CDC count.

Laura Crotty Alexander, MD, a pulmonologist and researcher with the University of California, San Diego, said she saw her first case about 2 years ago. A young man had been vaping for months with the same device but developed acute lung injury when he switched flavors. She strongly suspected a link, but did not report the illness anywhere.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t want to report it, it’s that there’s no pathway” to do so, Dr. Alexander said.

She said she’s concerned that many physicians haven’t been asking patients about e-cigarette use and that there’s no way to document a case like this in the medical coding system.

John E. Parker, MD, of West Virginia University, Morgantown, said he saw his first patient with pneumonia tied to vaping in 2015. Doctors there were intrigued enough to report on the case at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. Dr. Parker and his team didn’t contact a federal agency, and Dr. Parker said it was unclear whom to call.

Numerous other cases have been reported in medical journals and at professional conferences in the years since. The FDA’s voluntary system for reporting tobacco-related health problems included 96 seizures and only 1 lung ailment tied to e-cigarettes between April and June 2019. The system appears to be utilized most by concerned citizens, rather than manufacturers or health care professionals.

But several lung specialists said that due to the patchwork nature of regulatory oversight over the years, the true scope of the problem is yet to be identified.

“We do know that e-cigarettes do not emit a harmless aerosol,” said Brian King, PhD, MPH, a deputy director in the Office on Smoking and Health at the CDC in a call with media on Aug. 23 about the outbreak. “It is possible that some of these cases were already occurring but we were not picking them up.”

Regulatory limits

The FDA has had limited authority to regulate e-cigarettes over the years.

In 2009, Congress passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, empowering the FDA to oversee the safety and sale of tobacco products. But e-cigarettes, still new, were not top of mind.

Later that year, the FDA tried to block imports of e-cigarettes, saying the combination drug-device products were unapproved and therefore illegal for sale in the United States. Two vaping companies, Smoking Everywhere and NJoy, sued, and a federal judge ruled in 2010 that the FDA should regulate e-cigarettes as tobacco products.

It took the agency 6 years to finalize what’s become known as the “deeming rule,” in which it formally began regulating e-cigarettes and e-liquids.

By then, it was May 2016, and the e-cigarette market had swelled to an estimated $4.1 billion, Wells Fargo Securities analyst Bonnie Herzog said at the time. Market researchers now project that the global industry could reach $48 billion by 2023.

Critics say the FDA took too long to act.

“I think the fact that FDA has been dillydallying [has made] figuring out what’s going on [with this outbreak] much harder,” said Stanton Glantz, PhD, a University of California, San Francisco, professor in its Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. “No question.”

The agency began by banning e-cigarette sales to minors and requiring all new vaping products to submit applications for authorization before they could come to market. Companies and retailers with thousands of products already on the market were granted 2 years to submit applications, and the FDA would get an additional year to evaluate the applications. Meanwhile, existing products could still be sold.

But when Scott Gottlieb, MD, arrived as the new FDA commissioner in 2017, the rule hadn’t been implemented and there was no formal guidance for companies to file applications, he said. As a result, he pushed the deadline back to 2022, drawing ire from public health advocates, who called foul over his previous ties to an e-cigarette retailer called Kure.

“I thought e-cigarettes at the time – and I still believe – that they represent an opportunity for currently addicted adult smokers to transition off of combustible tobacco,” he said in an interview, adding that other parts of the deeming rule went into effect as planned. “All I did was delay the application deadline.”

Dr. Gottlieb’s thinking changed the following year, when a national survey showed a sharp rise in teen vaping, which he called an “epidemic.” He announced that the agency would rethink the extended deadline and weigh whether to take flavors that appeal to kids off the market.

A judge ruled last month that e-cigarette makers would have only 10 more months to submit applications to the FDA. They’re now due in May 2020.

Asked about the lung injuries appearing now, Dr. Gottlieb, who left the FDA in April 2019, said he suspected counterfeit pods are to blame, given the geographic clustering of cases and the fact that, overall, the FDA is inspecting registered e-cigarette makers and retailers to make sure they’re complying with existing regulations.

“I think the manufacturers are culpable if their products are being used, whether the liquids are counterfeit or real,” he said. “Ultimately, they’re responsible for keeping their products out of the hands of kids.”

Juul, the leading e-cigarette maker, agreed that children shouldn’t be able to vape its products, and said curtailing access should be done “through significant regulation” and “enforcement.”

“When people say ‘Why aren’t these being regulated?’ They actually are all being regulated,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

For example, companies are required to label their products as potentially addictive, sell only to adults and comply with manufacturing standards. The agency has conducted thousands of inspections of e-cigarette manufacturers and retailers and taken enforcement actions against companies selling e-cigarettes that look like juice boxes, and against a company that was putting the ingredients found in erectile dysfunction drugs into its vape liquid.

Health departments investigating the outbreak told Kaiser Health News that e-cigarettes’ niche as a tobacco product instead of a drug has presented challenges. Most weren’t aware that adverse events could be reported to a database that tracks problems with tobacco products. And, because e-cigarettes never went through the FDA’s “gold-standard” approval process for drugs, doctors can’t readily look up a detailed list of known side effects.

But like other arms of the FDA, the tobacco office has tools and a team to investigate a public health threat just as the teams for drugs and devices do, Dr. Gottlieb said. It may even be better equipped because of its funding.

“I don’t think FDA is operating in any way with hands tied behind its back because of the way that the statute is set up,” he said.

Teen vaping has exploded during this regulatory tussle. In 2011, 1.5% of high school students reported vaping. By 2018, it was 20.8%, according to a CDC report.

Unknown components

Still, doctors and researchers are concerned about the ingredients in e-cigarettes and how little the public knows about the risks of vaping.

In Juul’s terms and conditions, posted on its website, it says, “We encourage consumers to do their own research regarding vapor products and what is right for them.” Many ingredients in e-cigarette products, however, are protected as trade secrets.

Since at least 2013, the flavor industry has expressed concern about the use of flavoring chemicals in vaping products.

The vast majority of the chemicals have been tested only by ingesting them in small quantities because they’re encountered in foods. For most of these chemicals, there have been no tests to determine whether it is safe to inhale them, as happens daily by millions when they use e-cigarettes.

“Many of the ingredients of vaping products, including flavoring substances, have not been tested for … the exposure one would get from using a vaping device,” said John Hallagan, a senior adviser to the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association. The group has sent cease-and-desist letters to e-cigarette companies in previous years for using the food safety certification of the flavor industry to imply that the chemicals are also safe in e-cigarettes.

Some flavor chemicals are thought to be harmful when inhaled in high doses. Research suggests that cinnamaldehyde, the main component of many cinnamon flavors, may impair lung function when inhaled. Sven-Eric Jordt, PhD, a professor at Duke University, Durham, N.C., says he presented evidence of its dangers at an FDA meeting in 2015 — and its relative abundance in many e-cigarette vaping liquids. In response, one major e-cigarette liquid seller, Tasty Vapor, voluntarily took its cinnamon-flavored liquid off the shelves.

In 2017, when Dr. Gottlieb delayed the FDA application deadline, the product was back. A company email to its customers put it this way: “Two years ago, Tasty Vapor allowed itself to be intimidated by scaremongering tactics. … We lost a lot of sales as well as a good number of long-time customers. We no long see reason to disappoint our customers hostage for these shady tactics.”

At the time of publication, Tasty Vapor’s owner did not reply to a request for comment.

Dr. Jordt said he is frustrated by the delays in the regulatory approval process.

“As a parent, I would say that the government has not acted on this,” he said. “You’re basically left to act alone with your addicted kid. It’s kind of terrifying that this was allowed to happen. The industry needs to be held to account.”

Kaiser Health News correspondents Cara Anthony, Markian Hawryluk, and Lauren Weber, as well as reporter Victoria Knight contributed to this report. This story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

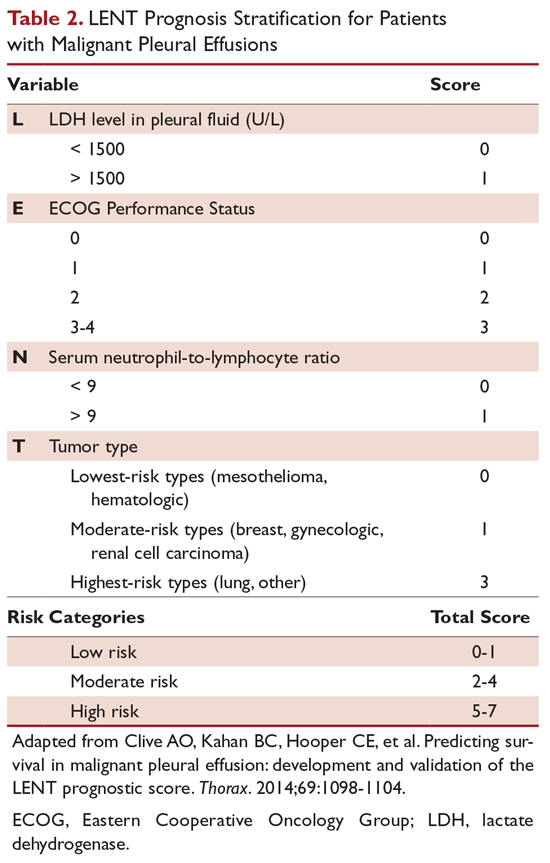

Malignant Pleural Effusion: Therapeutic Options and Strategies

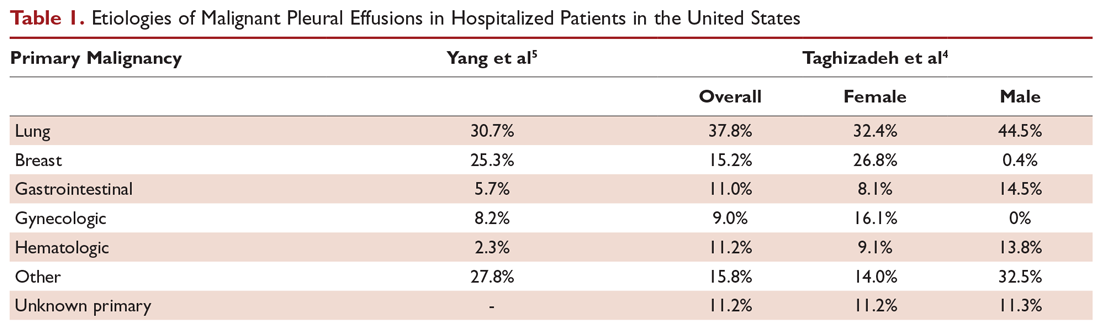

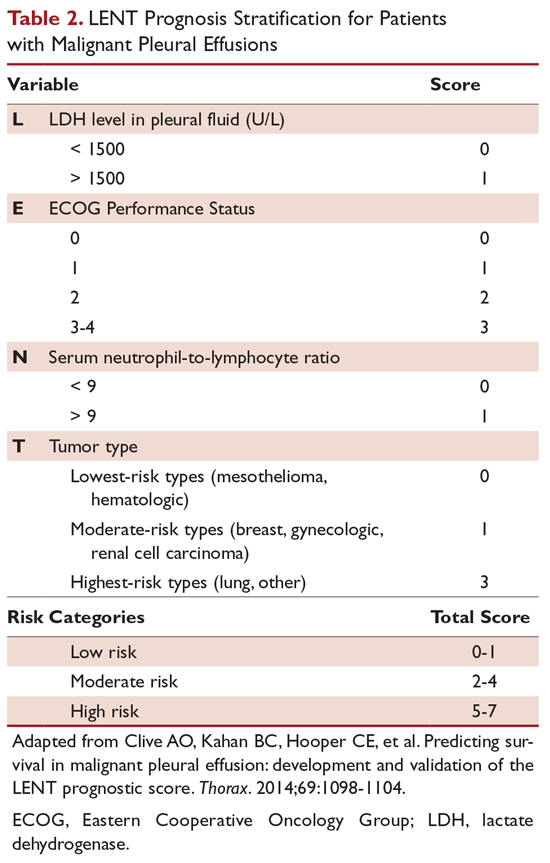

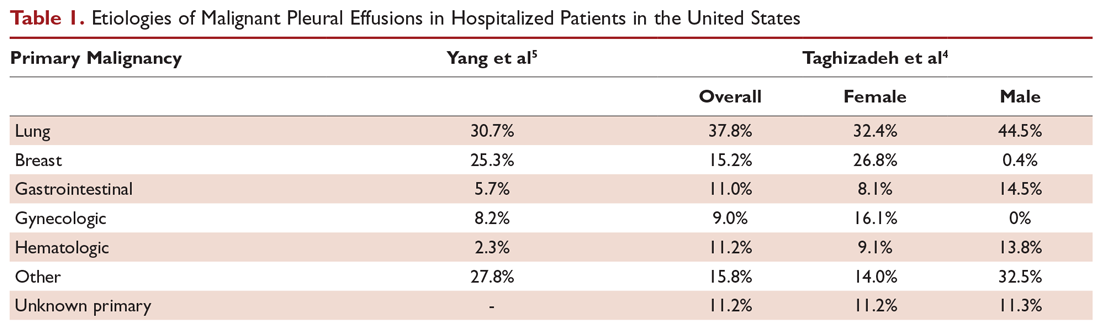

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a common clinical problem in patients with advanced stage cancer. Each year in the United States, more than 150,000 individuals are diagnosed with MPE, and there are approximately 126,000 admissions for MPE.1-3 Providing effective therapeutic management remains a challenge, and currently available therapeutic interventions are palliative rather than curative. This article, the second in a 2-part review of MPE, focuses on the available management options.

Therapeutic Thoracentesis

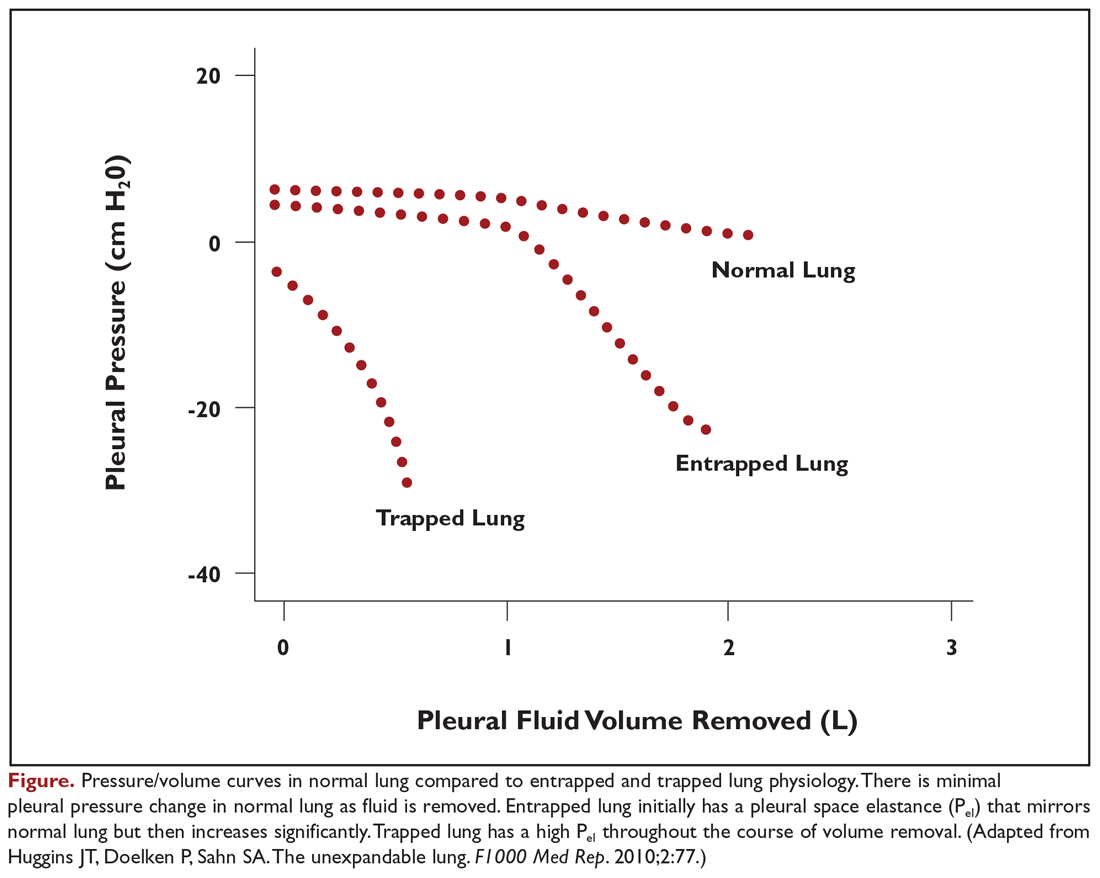

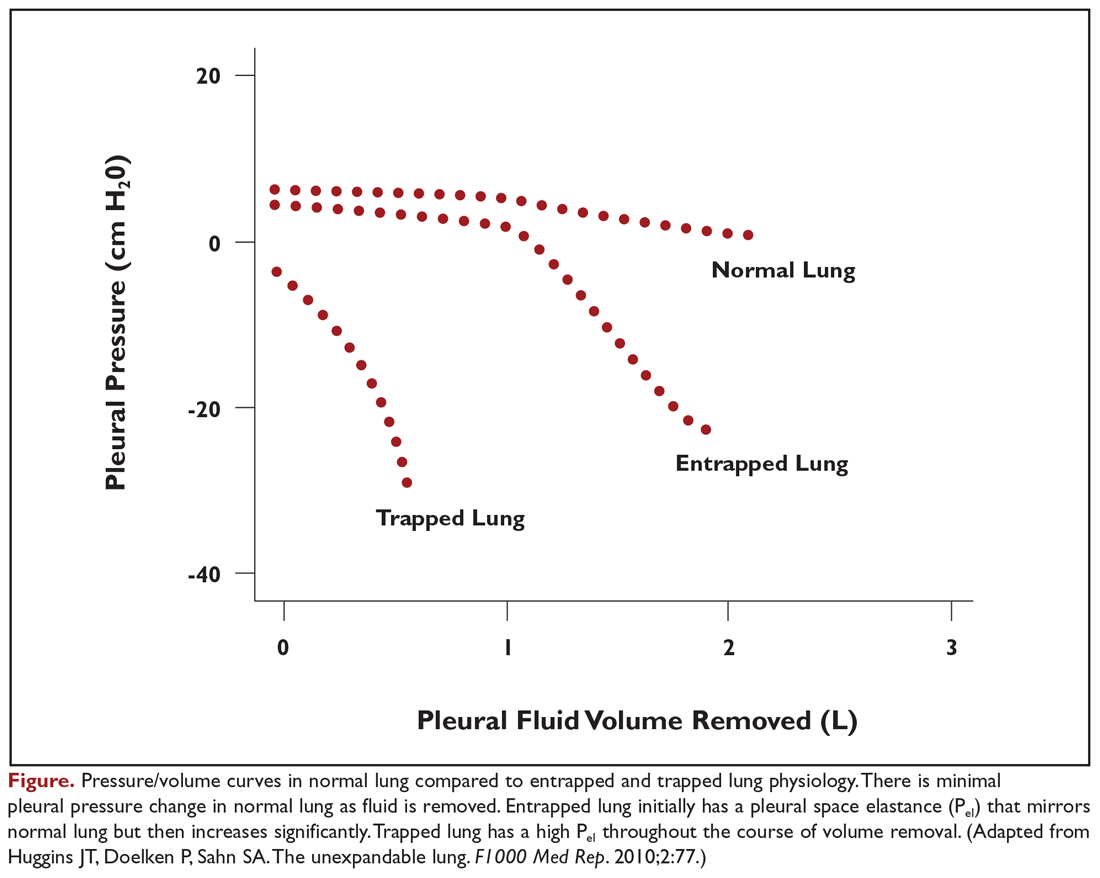

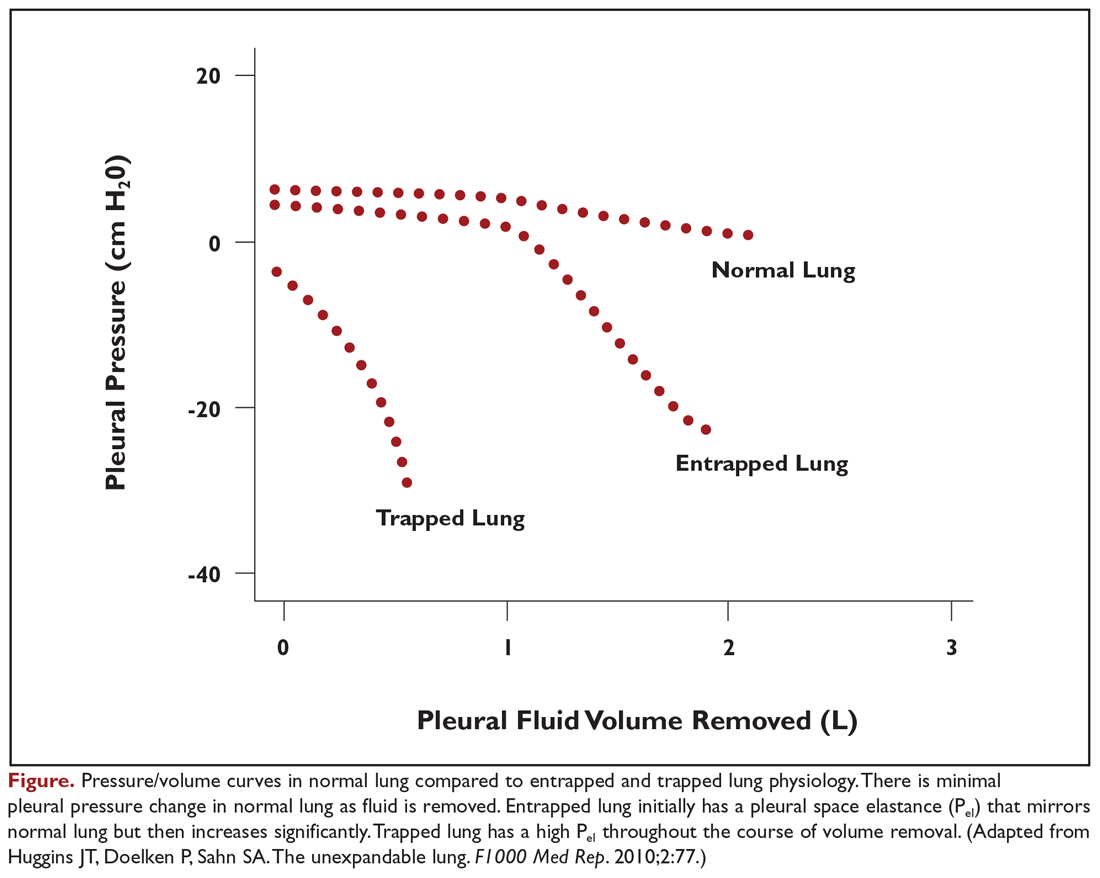

Evaluation of pleural fluid cytology is a crucial step in the diagnosis and staging of disease. As a result, large-volume fluid removal is often the first therapeutic intervention for patients who present with symptomatic effusions. A patient’s clinical response to therapeutic thoracentesis dictates which additional therapeutic options are appropriate for palliation. Lack of symptom relief suggests that other comorbid conditions or trapped lung physiology may be the primary cause of the patient’s symptoms and discourages more invasive interventions. Radiographic evidence of lung re-expansion after fluid removal is also an important predictor of success for potential pleurodesis.4,5

There are no absolute contraindications to thoracentesis. However, caution should be used for patients with risk factors that may predispose to complications of pneumothorax and bleeding, such as coagulopathy, treatment with anticoagulation medications, thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction (eg, antiplatelet medications, uremia), positive pressure ventilation, and small effusion size. These factors are only relative contraindications, however, as thoracentesis can still be safely performed by experienced operators using guidance technology such as ultrasonography.

A retrospective review of 1009 ultrasound-guided thoracenteses with risk factors of an international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 1.6, platelet values less than 50,000/μL, or both, reported an overall rate of hemorrhagic complication of 0.4%, with no difference between procedures performed with (n = 303) or without (n = 706) transfusion correction of coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia.6 A similar retrospective evaluation of 1076 ultrasound-guided thoracenteses, including 267 patients with an INR greater than 1.5 and 58 patients with a platelet count less than 50,000/μL, reported a 0% complication rate.7 Small case series have also demonstrated low hemorrhagic complication rates for thoracentesis in patients treated with clopidogrel8,9 and with increased bleeding risk from elevated INR (liver disease or warfarin therapy) and renal disease.10

Complications from pneumothorax can similarly be affected by patient- and operator-dependent risk factors. Meta-analysis of 24 studies including 6605 thoracenteses demonstrated an overall pneumothorax rate of 6.0%, with 34.1% requiring chest tube insertion.11 Lower pneumothorax rates were associated with the use of ultrasound guidance (odds ratio, 0.3; 95% confidence interval, 0.2-0.7). Experienced operators also had fewer pneumothorax complications, though this factor was not significant in the studies directly comparing this variable. Therapeutic thoracentesis and use of a larger-bore needle were also significantly correlated with pneumothorax, while mechanical ventilation had a nonsignificant trend towards increased risk.

Although there is no consensus on the volume of pleural fluid that may be safely removed, it is recommended not to remove more than 1.5 L during a procedure in order to avoid precipitating re-expansion pulmonary edema.2,12 However, re-expansion pulmonary edema rates remain low even when larger volumes are removed if the patient remains symptom-free during the procedure and pleural manometry pressure does not exceed –20 cm H2O.13 Patient symptoms alone, however, are neither a sensitive nor specific indicator that pleural pressures exceed –20 cm H2O.14 Use of excessive negative pressure during drainage, such as from a vacuum bottle, should also be avoided. Comparison of suction generated manually with a syringe versus a vacuum bottle suggests decreased complications with manual drainage, though the sample size in the supporting study was small relative to the infrequency of the complications being evaluated.15

Given the low morbidity and noninvasive nature of the procedure, serial large-volume thoracentesis remains a viable therapeutic intervention for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo more invasive interventions, especially for patients with a slow fluid re-accumulation rate or who are anticipated to have limited survival. Unfortunately, many symptomatic effusions will recur within a short interval time span, which necessitates repeat procedures.16,17 Therefore, factors such as poor symptom control, patient inconvenience, recurrent procedural risk, and utilization of medical resources need to be considered as well.

Tunneled Pleural Catheter

Tunneled pleural catheters (TPCs) are a potentially permanent and minimally invasive therapy which allow intermittent drainage of pleural fluid (Figure 1). The catheter is tunneled under the skin to prevent infection. A polyester cuff attached to the catheter is positioned within the tunnel and induces fibrosis around the catheter, thereby securing the catheter in place. Placement can be performed under local anesthesia at the patient’s bedside or in an outpatient procedure space. Fluid can then be drained via specialized drainage bottles or bags by the patient, a family member, or visiting home nurse. The catheter can also be removed in the event of a complication or the development of spontaneous pleurodesis.

TPCs are an effective palliative management strategy for patients with recurrent effusions and are an efficacious alternative to pleurodesis.18-20 TPCs may be used in patients with poor prognosis or trapped lung or in those in whom prior pleurodesis has failed.21-23 Meta-analysis of 19 studies showed symptomatic improvement in 95.6% of patients, with development of spontaneous pleurodesis in 45.6% of patients (range, 11.8% to 76.4%) after an average of 52 days.24 However, most of the studies included in this analysis were retrospective case series. Development of spontaneous pleurodesis from TPC drainage in prospective, controlled trials has been considerably more modest, supporting a range of approximately 20% to 30% with routine drainage strategies.20,25-27 Spontaneous pleurodesis develops greater rapidity and frequency in patients undergoing daily drainage compared to every-other-day or symptom-directed drainage strategies.25,26 However, there is no appreciable improvement in quality of life scores with a specific drainage strategy. Small case series also demonstrate that TPC drainage may induce spontaneous pleurodesis in some patients initially presenting with trapped lung physiology.22

Catheter placement can be performed successfully in the vast majority of patients.28 Increased bleeding risk, significant malignancy-related involvement of the skin and chest wall, and pleural loculations can complicate TPC placement. TPC-related complications are relatively uncommon, but include pneumothorax, catheter malfunction and obstruction, and infections including soft tissue and pleural space infections.24 In a multicenter retrospective series of 1021 patients, only 4.9% developed a TPC-related pleural infection.29 Over 94% were successfully managed with antibiotic therapy, and the TPC was able to be preserved in 54%. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common causative organism and was identified in 48% of cases. Of note, spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 62% of cases following a pleural space infection, which likely occurred as sequelae of the inflammatory nature of the infection. Retrospective analysis suggests that the risk of TPC-related infections is not substantially higher for patients with higher risks of immunosuppression from chemotherapy or hematologic malignancies.30,31 Tumor metastasis along the catheter tract is a rare occurrence (< 1%), but is most notable with mesothelioma, which has an incidence as high as 10%.24,32 In addition, development of pleural loculations can impede fluid drainage and relief of dyspnea. Intrapleural instillation of fibrinolytics can be used to improve drainage and improve symptom palliation.33

Pleurodesis

Pleurodesis obliterates the potential pleural space by inducing inflammation and fibrosis, resulting in adherence of the visceral and parietal pleura together. This process can be induced through mechanical abrasion of the pleural surface, introduction of chemical sclerosants, or from prolonged use of a chest tube. Chemical sclerosants are the most commonly used method for MPEs and are introduced through a chest tube or under visual guidance such as medical thoracoscopy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). The pleurodesis process is thought to occur by induction of a systemic inflammatory response with localized deposition of fibrin.34 Activation of fibroblasts and successful pleurodesis have been correlated with higher basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) levels in pleural fluid.35 Increased tumor burden is associated with lower bFGF levels, suggesting a possible mechanism for reduced pleurodesis success in these cases. Corticosteroids may reduce the likelihood of pleurodesis due to a reduction of inflammation, as demonstrated in a rabbit model using talc and doxycycline.36,37 Animal data also suggests that use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may hinder the likelihood of successful pleurodesis, but this has not been observed in humans.38,39

Patients selected for pleurodesis should have significant symptom relief from large-volume removal of pleural fluid, good functional status, and evidence of full lung re-expansion after thoracentesis. Lack of visceral and parietal pleural apposition will prevent pleural adhesion from developing. As a result, trapped lung is associated with chemical pleurodesis failure and is an absolute contraindication to the procedure.4,5,12 The pleurodesis process typically requires 5 to 7 days, during which time the patient is hospitalized for chest tube drainage and pain control. When pleural fluid output diminishes, the chest tube is removed and the patient can be discharged. Modified protocols are now emerging which may shorten the required hospitalization associated with pleurodesis procedures.

Pleurodesis Agents

A variety of chemical sclerosants have been used for pleurodesis, including talc, bleomycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, iodopovidone, and mepacrine. Published data regarding these agents are heterogenous, with significant variability in reported outcomes. However, systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that talc is likely to have higher success rates compared to other agents or chest tube drainage alone for treatment of MPE.40,41

Additional factors have been shown to be associated with pleurodesis outcomes. Pleurodesis success is negatively associated with low pleural pH, with receiver operating curve thresholds of 7.28 to 7.34.42,43 Trapped lung, large bulky tumor lining the pleural surfaces, and elevated adenosine deaminase levels are also associated with poor pleurodesis outcomes.4,5,12,35,43 In contrast, pleural fluid output less than 200 mL per day and the presence of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) mutation treated with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors are associated with successful pleurodesis.44,45

The most common complications associated with chemical pleurodesis are fever and pain. Other potential complications include soft tissue infections at the chest tube site and of the pleural space, arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, and hypotension. Doxycycline is commonly associated with greater pleuritic pain than talc. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute pneumonitis, and respiratory failure have been described with talc pleurodesis. ARDS secondary to talc pleurodesis occurs in 1% to 9% of cases, though this may be related to the use of ungraded talc. A prospective description of 558 patients treated with large particle talc (> 5 μm) reported no occurrences of ARDS, suggesting the safety of graded large particle talc.46

Pleurodesis Methods

Chest tube thoracostomy is an inpatient procedure performed under local anesthesia or conscious sedation. It can be used for measured, intermittent drainage of large effusions for immediate symptom relief, as well as to demonstrate complete lung re-expansion prior to instillation of a chemical sclerosant. Pleurodesis using a chest tube is performed by instillation of a slurry created by mixing the sclerosing agent of choice with 50 to 100 mL of sterile saline. This slurry is instilled into the pleural cavity through the chest tube. The chest tube is clamped for 1 to 2 hours before being reconnected to suction. Intermittent rotation of the patient has not been shown to improve distribution of the sclerosant or result in better procedural outcomes.47,48 Typically, a 24F to 32F chest tube is used because of the concern about obstruction of smaller bore tubes by fibrin plugs. A noninferiority study comparing 12F to 24F chest tubes for talc pleurodesis demonstrated a higher procedure failure rate with the 12F tube (30% versus 24%) and failed to meet noninferiority criteria.39 However, larger caliber tubes are also associated with greater patient discomfort compared to smaller bore tubes.

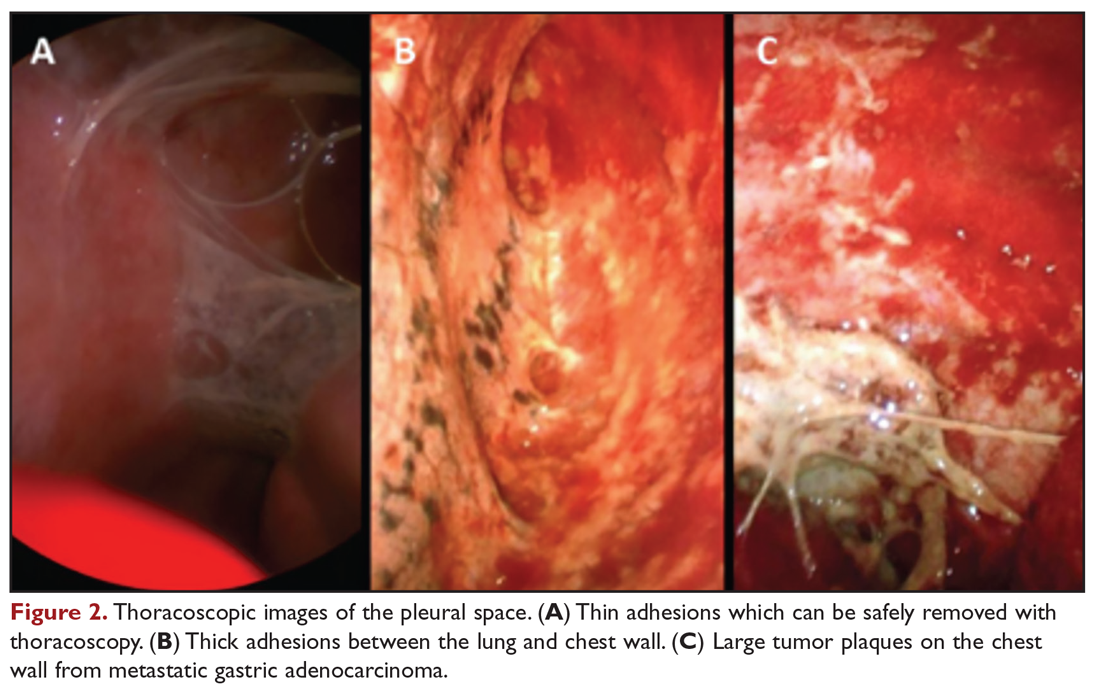

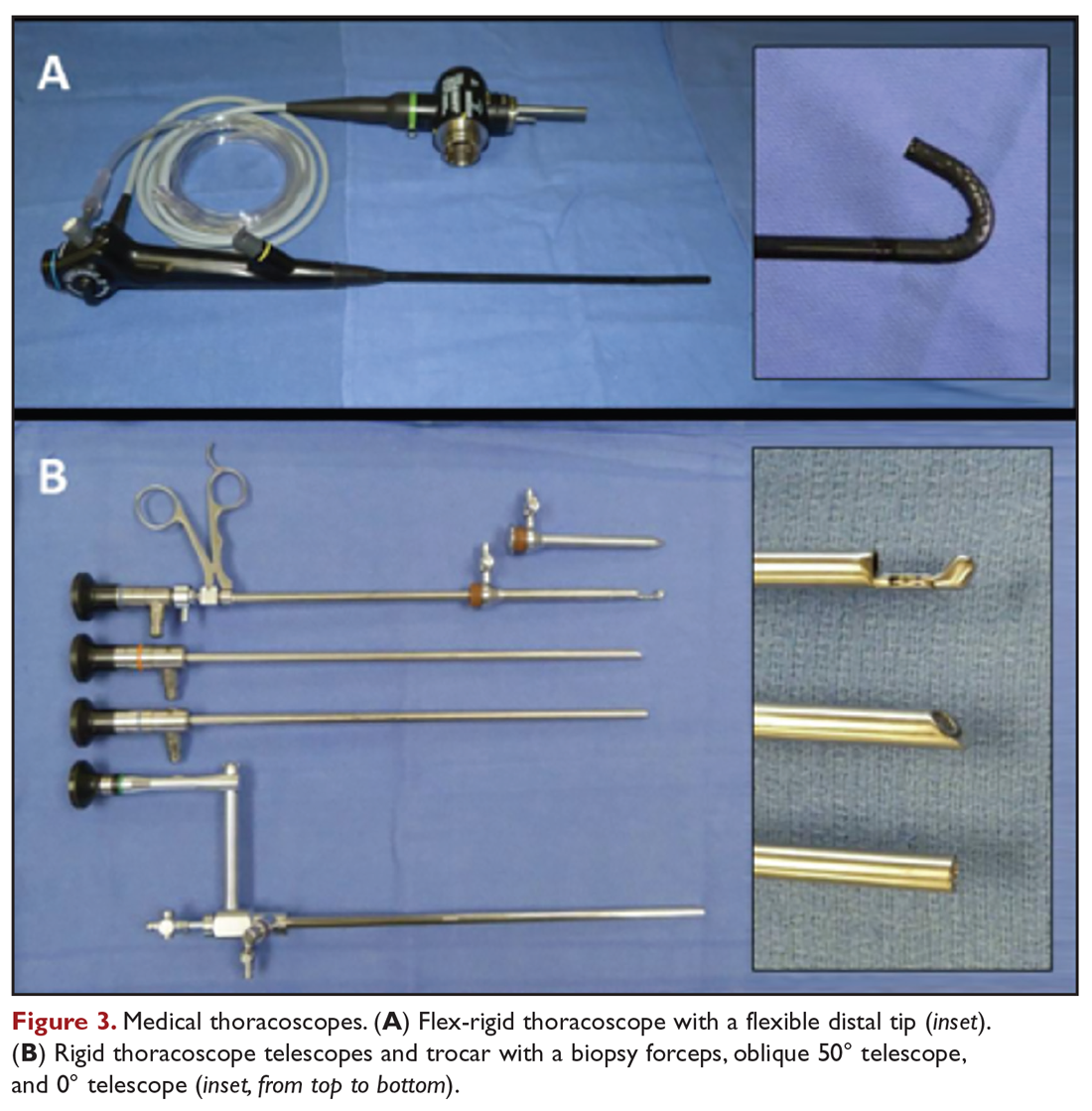

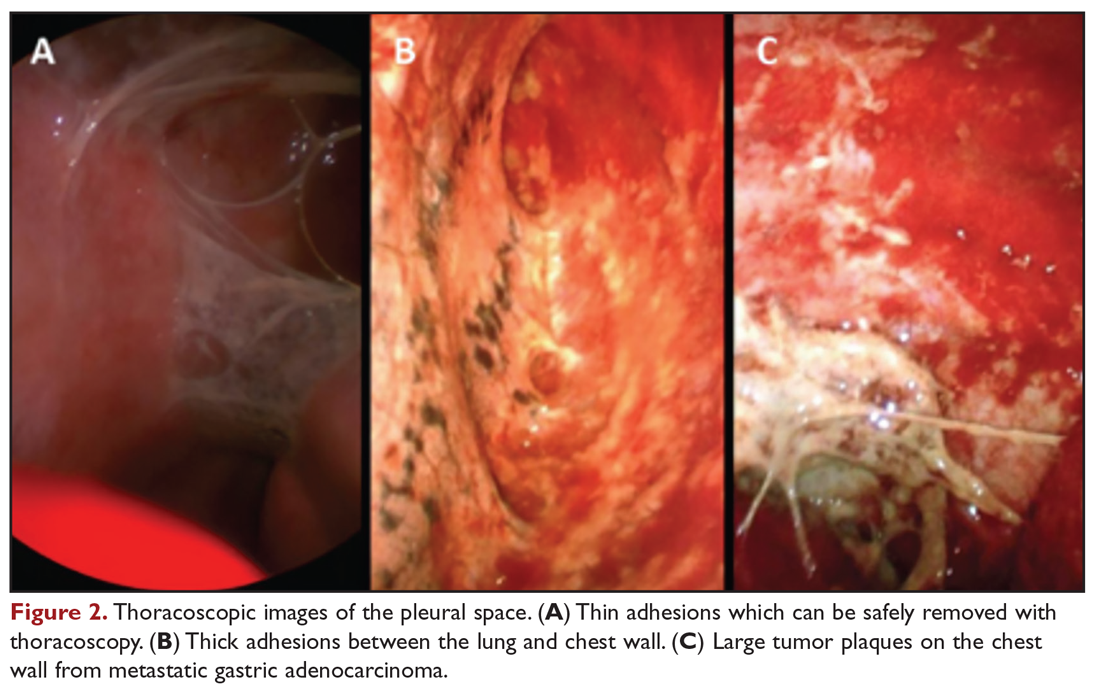

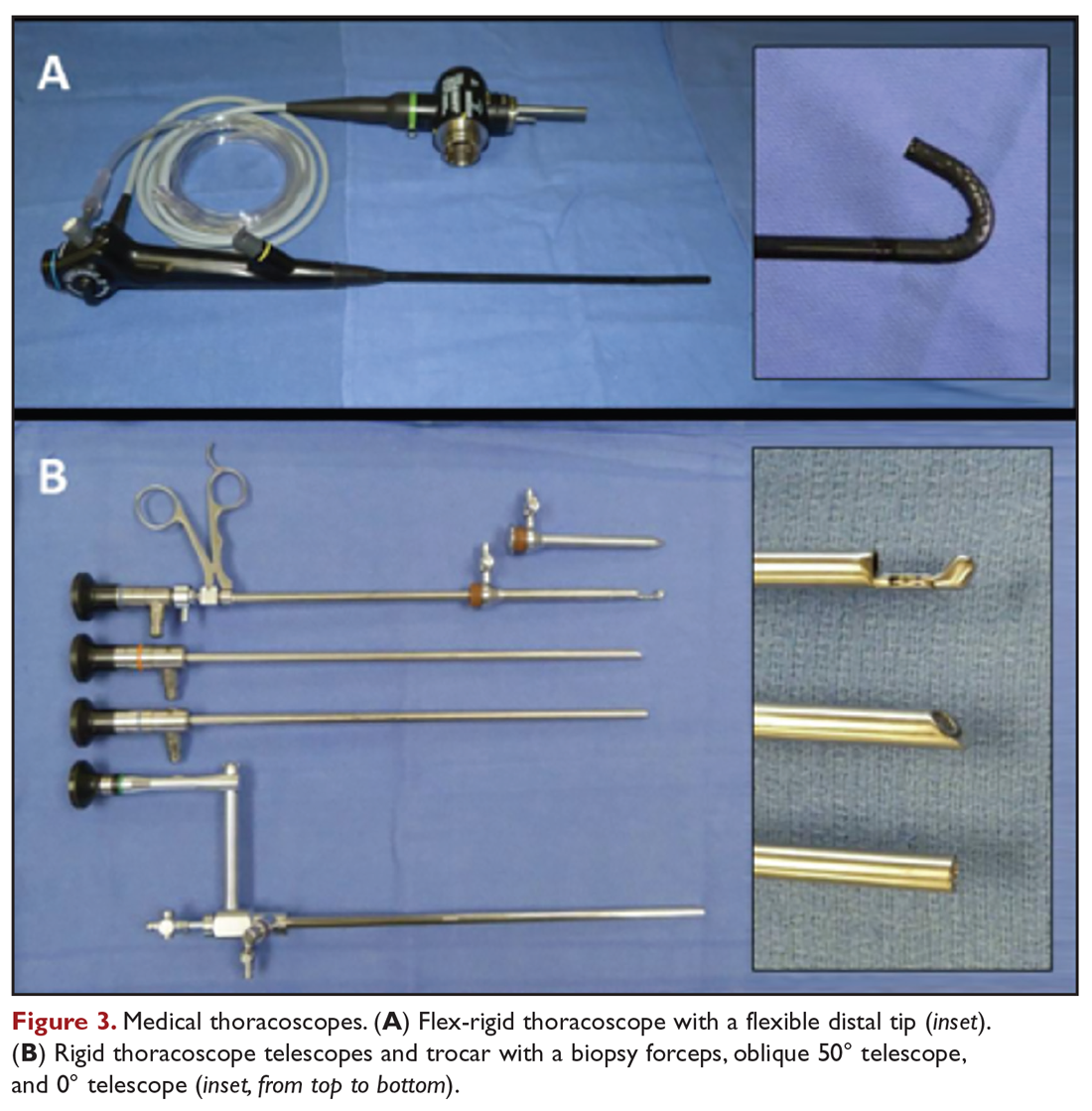

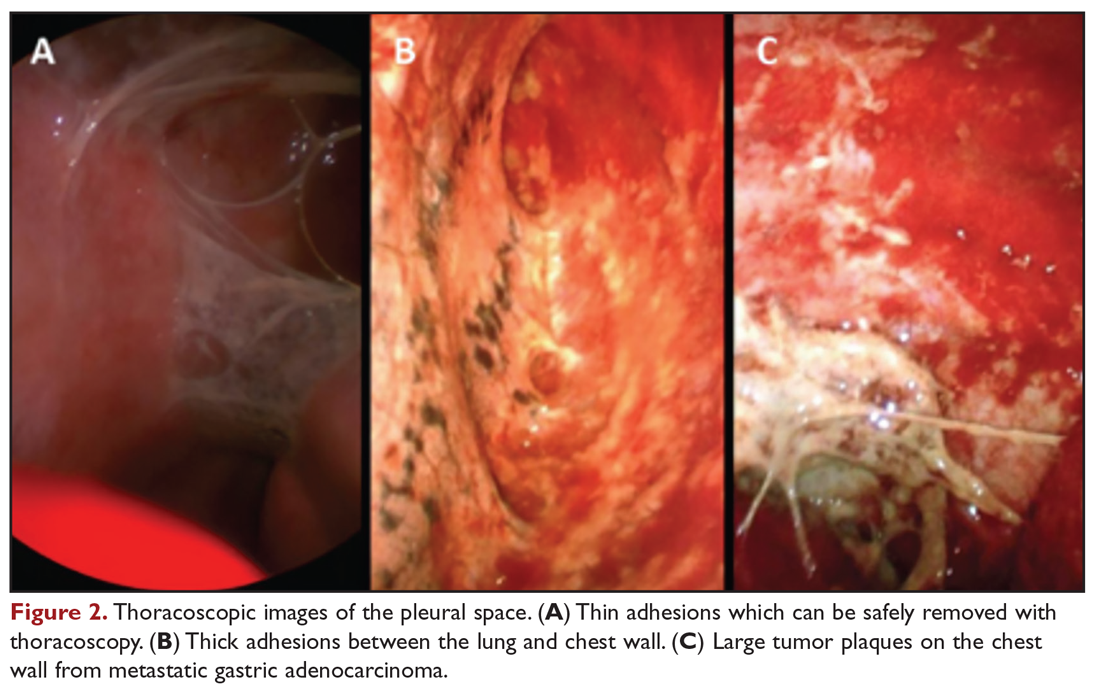

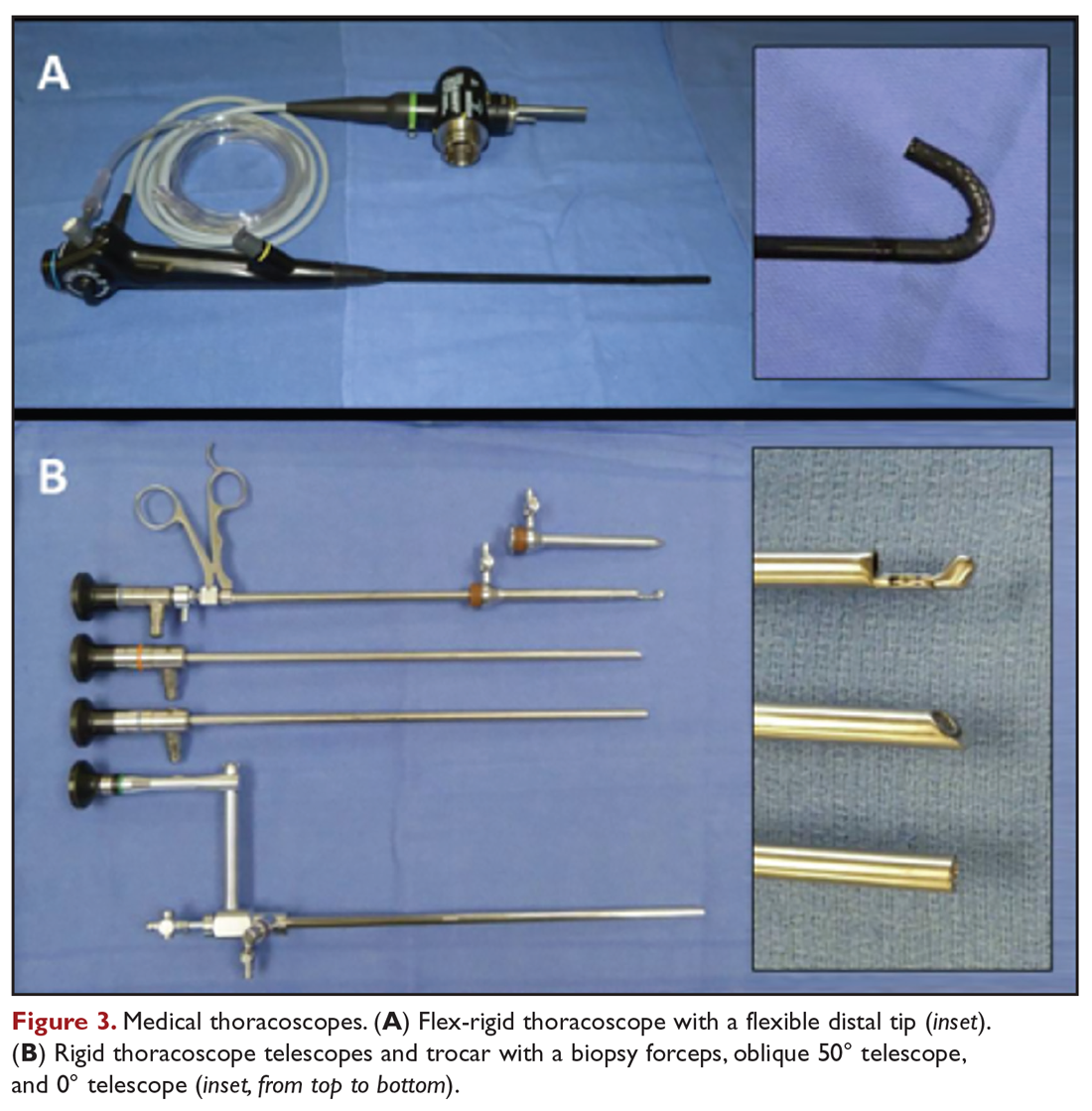

Medical thoracoscopy and VATS are minimally invasive means to visualize the pleural space, obtain visually guided biopsy of the parietal pleura, perform lysis of adhesions, and introduce chemical sclerosants for pleurodesis (Figure 2). Medical thoracoscopy can be performed under local anesthesia with procedural sedation in an endoscopy suite or procedure room.

VATS has several distinct and clinically important differences. The equipment is slightly larger but otherwise similar in concept to rigid medical thoracoscopes. A greater number of diagnostic and therapeutic options, such as diagnostic biopsy of lung parenchyma and select hilar lymph nodes, are also possible. However, VATS requires surgical training and is performed in an operating room setting, which necessitates additional ancillary and logistical support. VATS also uses at least 2 trocar insertion sites, requires general anesthesia, and utilizes single-lung ventilation through a double-lumen endotracheal tube. Procedure-related complications for medical thoracoscopy and VATS include pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, fever, and pain.49

Data comparing talc slurry versus talc poudrage are heterogenous, without clear advantage for either method. Reported rates of successful pleurodesis are generally in the range of 70% to 80% for both methods.19,20,40,50 There is a possible suggestion of benefit with talc poudrage compared to slurry, but data is lacking to support either as a definitive choice in current guidelines.12,51 An advantage of medical thoracoscopy or VATS is that pleural biopsy can be performed simultaneously, if necessary, thereby allowing both diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.52 Visualizing the thoracic cavity may also permit creation of optimal conditions for pleurodesis in select individuals by allowing access to loculated spaces and providing visual confirmation of complete drainage of pleural fluid and uniform distribution of the chemical sclerosant.

Other Surgical Interventions

Thoracotomy with decortication is rarely used as treatment of malignant effusions complicated by loculations or trapped lung due to the significantly increased procedural morbidity and mortality. Therefore, it is reserved for the limited population of patients in whom other therapeutic interventions have failed but who otherwise have significant symptoms with a long life expectancy. Mesothelioma is a specific situation in which variations of pleurectomy, such as radical pleurectomy with decortication, lung-sparing total pleurectomy, and extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), have been used as front-line therapy. The Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) trial, the only randomized, controlled evaluation of EPP, demonstrated decreased median survival in patients treated by EPP compared to controls (14.4 months versus 19.5 months).53 EPP is also associated with high procedure-related morbidity and mortality rates of approximately 50% and 4% to 15%, respectively.54 While successful at achieving pleurodesis, use of EPP as a treatment for mesothelioma is now discouraged.53,55 Less invasive surgical approaches, such as pleurectomy with decortication, are able to palliate symptoms with significantly less operative risk.56

Management Considerations

Selection of Therapeutic Interventions

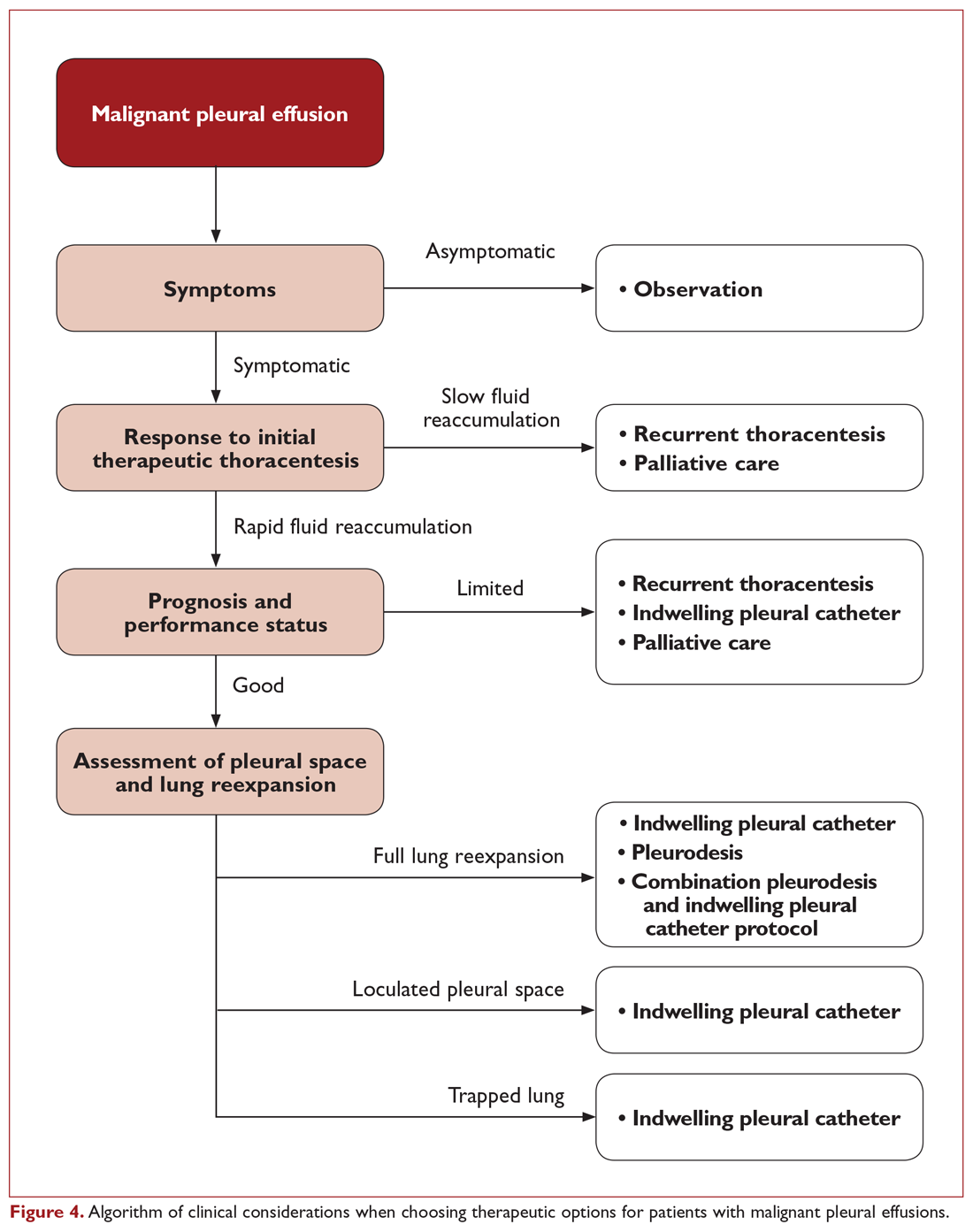

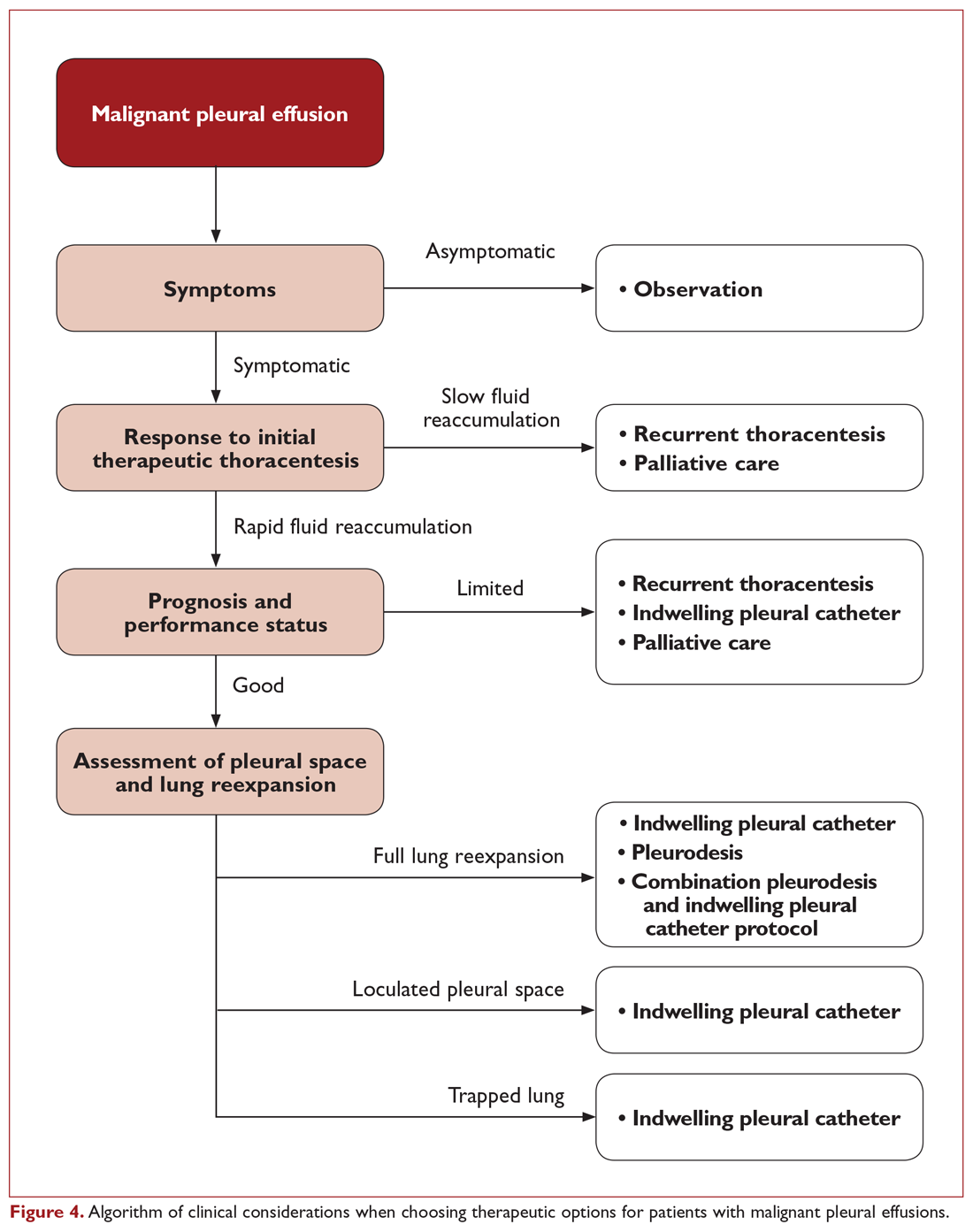

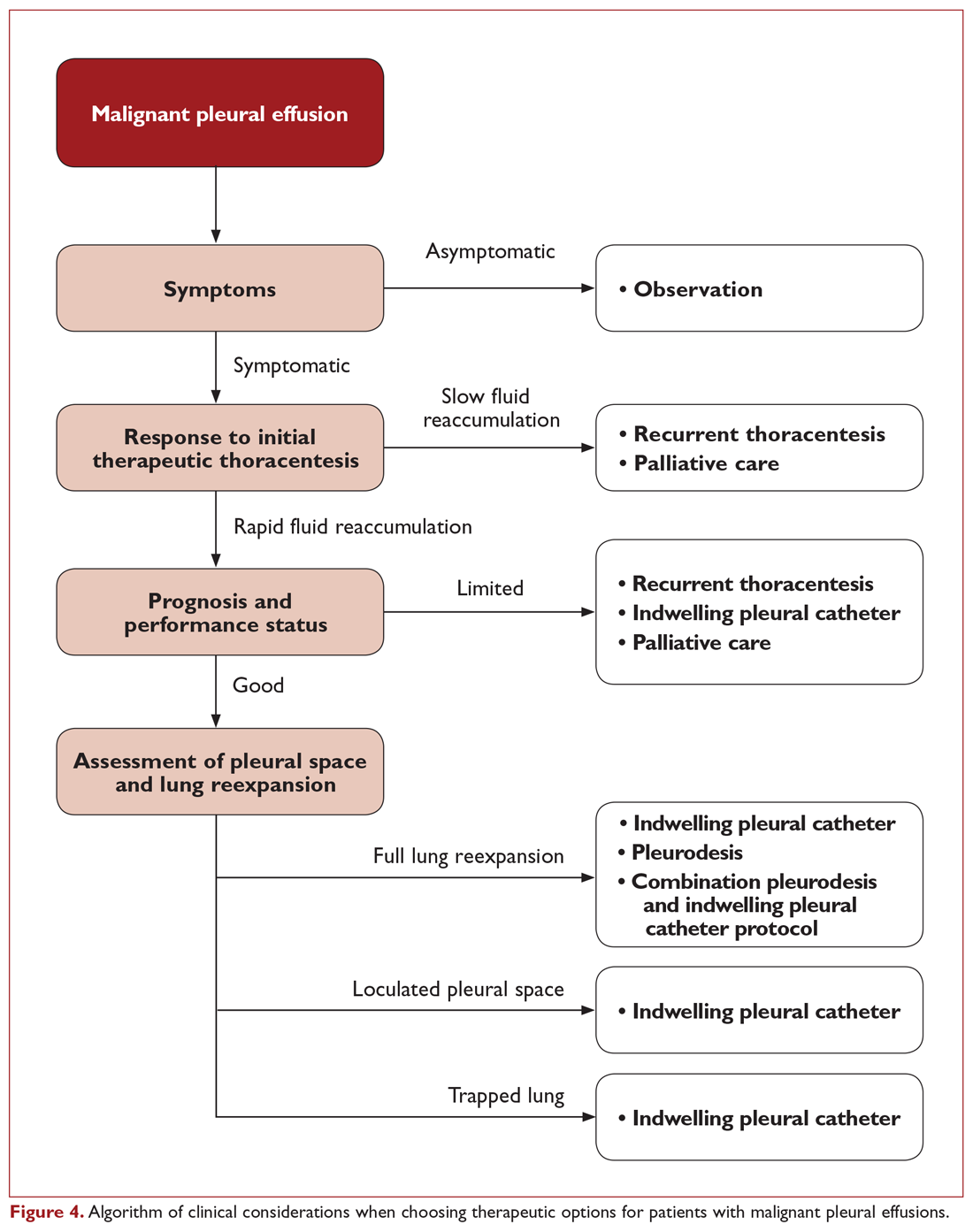

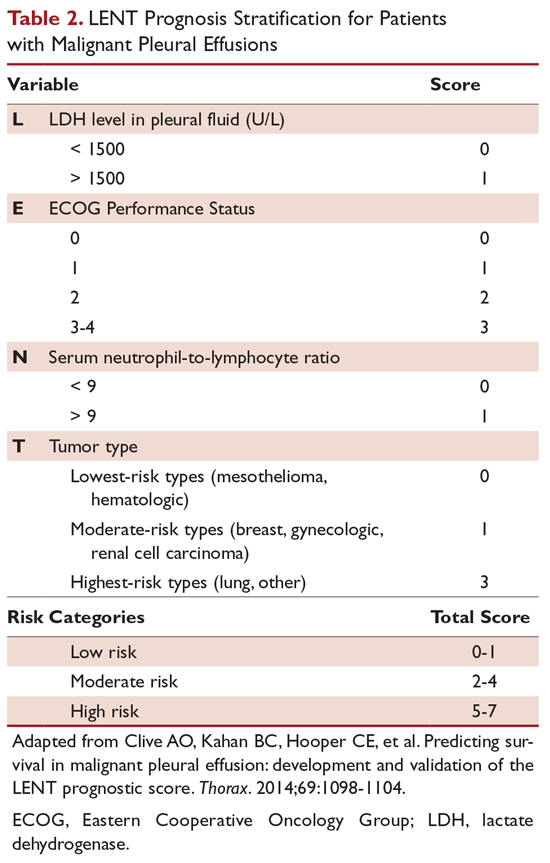

The ideal management strategy provides both immediate and long-term symptom palliation, has minimal associated morbidity and side effects, minimizes hospitalization time and clinic visits, avoids the risks and inconvenience of recurring procedures, is inexpensive, and minimizes utilization of medical resources. Unfortunately, no single palliation methodology fits these needs for all patients. When evaluating therapeutic options for patients with MPE, it is important to consider factors such as the severity of symptoms, fluid quantity, fluid re-accumulation rate, pleural physiology, functional status, overall prognosis, and anticipated response of the malignancy to therapy. One example management algorithm (Figure 4) demonstrates the impact of these variables on the appropriate treatment options. However, this is a simplified algorithm and the selected palliation strategy should be decided upon after shared decision-making between the patient and physician and should fit within the context of the patient’s desired goals of care. It is also crucial for patients to understand that these therapeutic interventions are palliative rather than curative.

When compared directly with pleurodesis, TPC provides similar control of symptoms but with a reduction in hospital length of stay by a median of 3.5 to 5.5 days.19,57 In a nonrandomized trial where patients chose palliation by TPC or talc pleurodesis, more TPC patients had a significant immediate improvement in quality of life and dyspnea after the first 7 days of therapy.58 This is reasonably attributed to the differences between the immediate relief from fluid drainage after TPC placement compared to the time required for pleural symphysis to occur with pleurodesis. However, control of dyspnea symptoms is similar between the 2 strategies after 6 weeks.19 Therefore, both TPC and pleurodesis strategies are viewed as first-line options for patients with expandable lung and no prior palliative interventions for MPE.59

Pleural adhesions and trapped lung also pose specific dilemmas. Pleural adhesions can create loculated fluid pockets, thereby complicating drainage by thoracentesis or TPC and hindering dispersal of pleurodesis agents. Adhesiolysis by medical thoracoscopy or VATS may be useful in these patients to free up the pleural space and improve efficacy of long-term drainage options or facilitate pleurodesis. Intrapleural administration of fibrinolytics, such as streptokinase and urokinase, has also been used for treatment of loculated effusions and may improve drainage of pleural fluid and lung re-expansion.60-63 However routine use of intrapleural fibrinolytics with pleurodesis has not been shown to be beneficial. In a randomized comparison using intrapleural urokinase prior to pleurodesis for patients with septated malignant pleural effusions, no difference in pleurodesis outcomes were identified.63 As a result, TPC is the preferred palliation approach for patients with trapped lung physiology.51,59

Combination Strategies

Combinations of different therapeutic interventions are being evaluated as a means for patients to achieve long-term benefits from pleurodesis while minimizing hospitalization time. One strategy using simultaneous treatment with thoracoscopic talc poudrage and insertion of a large-bore chest tube and TPC has been shown to permit early removal of the chest tube and discharge home using the TPC for continued daily pleural drainage. This “rapid pleurodesis” strategy has an 80% to 90% successful pleurodesis rate, permitting removal of the TPC at a median of 7 to 10 days.64,65 With this approach, median hospitalization length of stay was approximately 2 days. While there was no control arm in these early reports with limited sample sizes, the pleurodesis success rate and length of hospitalization compare favorably to other published studies. A prospective, randomized trial of TPC versus an outpatient regimen of talc slurry via TPC has also shown promise, with successful pleurodesis after 35 days in 43% of those treated with the combination of talc slurry and TPC compared to only 23% in those treated by TPC alone.27

Another novel approach to obtain the benefits of both TPC and pleurodesis strategies is the use of drug-eluting TPC to induce inflammation and promote adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura. An early report of slow-release silver nitrate (AgNO3) –coated TPC demonstrated an encouraging 89% spontaneous pleurodesis rate after a median of 4 days in the small subgroup of patients with fully expandable lung.66 Device-related adverse events were relatively high at 24.6%, though only one was deemed a serious adverse event. Additional studies of these novel and combination strategies are ongoing at this time.

Costs

While cost of care is not a consideration in the decision-making for individual patients, it is important from a systems-based perspective. Upfront costs for pleurodesis are generally higher due to the facility and hospitalization costs, whereas TPC have ongoing costs for drainage bottles and supplies. In a prospective, randomized trial of TPC versus talc pleurodesis, there was no appreciable difference in overall costs between the 2 approaches.67 The cost of TPC was significantly less, however, for patients with a shorter survival of less than 14 weeks.

Readmissions

Subsequent hospitalization requirements beyond just the initial treatment for a MPE remains another significant consideration for this patient population. A prospective, randomized trial comparing TPC to talc pleurodesis demonstrated a reduction in total all-cause hospital stay for TPC, with a median all-cause hospitalization time of 10 days for patients treated with TPC compared to 12 days for the talc pleurodesis group.20 The primary difference in the number of hospitalization days was due to a difference in effusion-related hospital days (median 1 versus 4 days, respectively), which was primarily comprised of the initial hospitalization. In addition, fewer patients treated with TPC required subsequent ipsilateral invasive procedures (4.1% versus 22.5%, respectively). However, it is important to note that the majority of all-cause hospital days were not effusion-related, demonstrating that this population has a high utilization of acute inpatient services for other reasons related to their advanced malignancy. In a study of regional hospitals in the United States, 38.3% of patients admitted for a primary diagnosis of MPE were readmitted within 30 days.68 There was remarkably little variability in readmission rates among hospitals, despite differences in factors such as institution size, location, patient distribution, and potential practice differences. This suggests that utilization of palliation strategies for MPE are only one component related to hospitalization in this population. Even at the best performing hospitals, there are significant common drivers for readmission that are not addressed. Therefore, additional effort should be focused on addressing aspects of care beyond just the palliation of MPE that predispose this population to requiring frequent treatment in an acute care setting.

Conclusion

MPEs represent advanced stage disease and frequently adversely affect a patient’s quality of life. The treating clinician has access to a variety of therapeutic options, though no single intervention strategy is universally superior in all circumstances. Initial thoracentesis is important in evaluating whether removal of a large volume of fluid provides significant symptom relief and restores functional status. Both talc pleurodesis and TPC provide similar control of symptoms and are first-line approaches for symptomatic patients with MPE and fully expandable lungs. Pleurodesis is associated with greater procedure-related risk and length of hospitalization and is contraindicated in patients with trapped lung, but does not require long-term catheter care or disposable resources. Determination of the appropriate therapeutic management strategy requires careful evaluation of the patient’s clinical situation and informed discussion with the patient to make sure that the treatment plan fits within the context of their goals of medical care.

1. Antony VB, Loddenkemper R, Astoul P, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:402-419.

2. Society AT. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1987-2001.

3. Taghizadeh N, Fortin M, Tremblay A. US hospitalizations for malignant pleural effusions: data from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Chest. 2017;151:845-854.

4. Adler RH, Sayek I. Treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a method using tube thoracostomy and talc. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976;22:8-15.

5. Villanueva AG, Gray AW, Shahian DM, et al. Efficacy of short term versus long term tube thoracostomy drainage before tetracycline pleurodesis in the treatment of malignant pleural effusions. Thorax. 1994;49:23-25.

6. Hibbert RM, Atwell TD, Lekah A, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest. 2013;144:456-463.

7. Patel MD, Joshi SD. Abnormal preprocedural international normalized ratio and platelet counts are not associated with increased bleeding complications after ultrasound-guided thoracentesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W164-168.

8. Zalt MB, Bechara RI, Parks C, Berkowitz DM. Effect of routine clopidogrel use on bleeding complications after ultrasound-guided thoracentesis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:284-287.

9. Mahmood K, Shofer SL, Moser BK, et al. Hemorrhagic complications of thoracentesis and small-bore chest tube placement in patients taking clopidogrel. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:73-79.

10. Puchalski JT, Argento AC, Murphy TE, et al. The safety of thoracentesis in patients with uncorrected bleeding risk. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:336-341.

11. Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Balk EM, Smetana GW. Pneumothorax following thoracentesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:332-339.

12. Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, et al; Group BPDG. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65 Suppl 2:ii32-40.

13. Feller-Kopman D, Berkowitz D, Boiselle P, Ernst A. Large-volume thoracentesis and the risk of reexpansion pulmonary edema. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1656-1661.

14. Feller-Kopman D, Walkey A, Berkowitz D, Ernst A. The relationship of pleural pressure to symptom development during therapeutic thoracentesis. Chest. 2006;129:1556-1560.

15. Senitko M, Ray AS, Murphy TE, et al. Safety and tolerability of vacuum versus manual drainage during thoracentesis: a randomized trial. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019;26:166-171.

16. Ost DE, Niu J, Zhao H, et al. Quality gaps and comparative effectiveness of management strategies for recurrent malignant pleural effusions. Chest. 2018;153:438-452.

17. Grosu HB, Molina S, Casal R, et al. Risk factors for pleural effusion recurrence in patients with malignancy. Respirology. 2019;24:76-82.

18. Musani AI, Haas AR, Seijo L, et al. Outpatient management of malignant pleural effusions with small-bore, tunneled pleural catheters. Respiration. 2004;71:559-566.

19. Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:2383-2389.

20. Thomas R, Fysh ETH, Smith NA, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs talc pleurodesis on hospitalization days in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the AMPLE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1903-1912.

21. Qureshi RA, Collinson SL, Powell RJ, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusion associated with trapped lung syndrome. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2008;16:120-123.

22. Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:961-964.

23. Sioris T, Sihvo E, Salo J, et al. Long-term indwelling pleural catheter (PleurX) for malignant pleural effusion unsuitable for talc pleurodesis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:546-551.

24. Van Meter ME, McKee KY, Kohlwes RJ. Efficacy and safety of tunneled pleural catheters in adults with malignant pleural effusions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:70-76.

25. Wahidi MM, Reddy C, Yarmus L, et al. Randomized trial of pleural fluid drainage frequency in patients with malignant pleural effusions. the ASAP trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1050-1057.

26. Muruganandan S, Azzopardi M, Fitzgerald DB, et al. Aggressive versus symptom-guided drainage of malignant pleural effusion via indwelling pleural catheters (AMPLE-2): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:671-680.

27. Bhatnagar R, Keenan EK, Morley AJ, et al. Outpatient talc administration by indwelling pleural catheter for malignant effusion. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1313-1322.

28. Tremblay A, Michaud G. Single-center experience with 250 tunnelled pleural catheter insertions for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2006;129:362-368.

29. Fysh ETH, Tremblay A, Feller-Kopman D, et al. Clinical outcomes of indwelling pleural catheter-related pleural infections: an international multicenter study. Chest. 2013;144:1597-1602.

30. Morel A, Mishra E, Medley L, et al. Chemotherapy should not be withheld from patients with an indwelling pleural catheter for malignant pleural effusion. Thorax. 2011;66:448-449.

31. Gilbert CR, Lee HJ, Skalski JH, et al. The use of indwelling tunneled pleural catheters for recurrent pleural effusions in patients with hematologic malignancies: a multicenter study. Chest. 2015;148:752-758.

32. Thomas R, Budgeon CA, Kuok YJ, et al. Catheter tract metastasis associated with indwelling pleural catheters. Chest. 2014;146:557-562.

33. Thomas R, Piccolo F, Miller D, et al. Intrapleural fibrinolysis for the treatment of indwelling pleural catheter-related symptomatic loculations: a multicenter observational study. Chest. 2015;148:746-751.

34. Antony VB. Pathogenesis of malignant pleural effusions and talc pleurodesis. Pneumologie. 1999;53:493-498.

35. Antony VB, Nasreen N, Mohammed KA, et al. Talc pleurodesis: basic fibroblast growth factor mediates pleural fibrosis. Chest. 2004;126:1522-1528.

36. Xie C, Teixeira LR, McGovern JP, Light RW. Systemic corticosteroids decrease the effectiveness of talc pleurodesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(5 Pt 1):1441-1444.

37. Teixeira LR, Wu W, Chang DS, Light RW. The effect of corticosteroids on pleurodesis induced by doxycycline in rabbits. Chest. 2002;121:216-219.

38. Hunt I, Teh E, Southon R, Treasure T. Using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) following pleurodesis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:102-104.

39. Rahman NM, Pepperell J, Rehal S, et al. Effect of opioids vs NSAIDs and larger vs smaller chest tube size on pain control and pleurodesis efficacy among patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2641-2653.

40. Clive AO, Jones HE, Bhatnagar R, Preston NJ, Maskell N. Interventions for the management of malignant pleural effusions: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(5):CD010529.

41. Tan C, Sedrakyan A, Browne J, et al. The evidence on the effectiveness of management for malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:829-838.

42. Heffner JE, Nietert PJ, Barbieri C. Pleural fluid pH as a predictor of pleurodesis failure: analysis of primary data. Chest. 2000;117:87-95.

43. Yildirim H, Metintas M, Ak G, et al. Predictors of talc pleurodesis outcome in patients with malignant pleural effusions. Lung Cancer. 2008;62:139-144.

44. Aydogmus U, Ozdemir S, Cansever L, et al. Bedside talc pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion: factors affecting success. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:745-750.

45. Guo H, Wan Y, Tian G, et al. EGFR mutations predict a favorable outcome for malignant pleural effusion of lung adenocarcinoma with Tarceva therapy. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:880-890.

46. Janssen JP, Collier G, Astoul P, et al. Safety of pleurodesis with talc poudrage in malignant pleural effusion: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1535-1539.

47. Dryzer SR, Allen ML, Strange C, Sahn SA. A comparison of rotation and nonrotation in tetracycline pleurodesis. Chest. 1993;104:1763-1766.

48. Mager HJ, Maesen B, Verzijlbergen F, Schramel F. Distribution of talc suspension during treatment of malignant pleural effusion with talc pleurodesis. Lung Cancer. 2002;36:77-81.

49. Hsia D, Musani AI. Interventional pulmonology. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:1095-1114.

50. Dresler CM, Olak J, Herndon JE, et al. Phase III intergroup study of talc poudrage vs talc slurry sclerosis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2005;127:909-915.

51. Bibby AC, Dorn P, Psallidas I, et al. ERS/EACTS statement on the management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(1).

52. Sakuraba M, Masuda K, Hebisawa A, et al. Diagnostic value of thoracoscopic pleural biopsy for pleurisy under local anaesthesia. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:722-724.

53. Treasure T, Lang-Lazdunski L, Waller D, et al. Extra-pleural pneumonectomy versus no extra-pleural pneumonectomy for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinical outcomes of the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) randomised feasibility study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:763-772.

54. Zellos L, Jaklitsch MT, Al-Mourgi MA, Sugarbaker DJ. Complications of extrapleural pneumonectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19:355-359.

55. Zahid I, Sharif S, Routledge T, Scarci M. Is pleurectomy and decortication superior to palliative care in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:812-817.

56. Soysal O, Karaoğlanoğlu N, Demiracan S, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication for palliation in malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:210-213.

57. Putnam JB, Light RW, Rodriguez RM, et al. A randomized comparison of indwelling pleural catheter and doxycycline pleurodesis in the management of malignant pleural effusions. Cancer. 1999;86:1992-1999.

58. Fysh ETH, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest. 2012;142:394-400.

59. Feller-Kopman DJ, Reddy CB, DeCamp MM, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusions. An official ATS/STS/STR clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:839-849.

60. Davies CW, Traill ZC, Gleeson FV, Davies RJ. Intrapleural streptokinase in the management of malignant multiloculated pleural effusions. Chest. 1999;115:729-733.

61. Hsu LH, Soong TC, Feng AC, Liu MC. Intrapleural urokinase for the treatment of loculated malignant pleural effusions and trapped lungs in medically inoperable cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:460-467.

62. Okur E, Baysungur V, Tezel C, et al. Streptokinase for malignant pleural effusions: a randomized controlled study. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2011;19:238-243.

63. Mishra EK, Clive AO, Wills GH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of urokinase versus placebo for nondraining malignant pleural effusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:502-508.

64. Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest. 2011;139:1419-1423.

65. Krochmal R, Reddy C, Yarmus L, et al. Patient evaluation for rapid pleurodesis of malignant pleural effusions. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:2538-2543.