User login

NDMA found in samples of ranitidine, FDA says

According to the Food and Drug Administration,

“NDMA is a known environmental contaminant and found in water and foods, including meats, dairy products, and vegetables,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement issued on Sept. 13, 2019. “The FDA has been investigating NDMA and other nitrosamine impurities in blood pressure and heart failure medicines called Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) since last year. In the case of ARBs, the FDA has recommended numerous recalls as it discovered unacceptable levels of nitrosamines.”

Dr. Woodcock said that the agency is working with industry partners to determine whether the low levels of NDMA in ranitidine pose a risk to patients, and it plans to post that information when it becomes available. For now, “patients should be able to trust that their medicines are as safe as they can be and that the benefits of taking them outweigh any risk to their health,” she said. “Although NDMA may cause harm in large amounts, the levels the FDA is finding in ranitidine from preliminary tests barely exceed amounts you might expect to find in common foods.”

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that the FDA is not suggesting that individuals stop taking ranitidine at this time. “However, patients taking prescription ranitidine who wish to discontinue use should talk to their health care professional about other treatment options,” she said. “People taking OTC ranitidine could consider using other OTC medicines approved for their condition. There are multiple drugs on the market that are approved for the same or similar uses as ranitidine.”

She advised consumers and health care professionals to report any adverse reactions with ranitidine to the FDA’s MedWatch program to help the agency better understand the problem.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about GERD, including symptoms, testing, lifestyle modifications and drug treatments at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-gerd.

According to the Food and Drug Administration,

“NDMA is a known environmental contaminant and found in water and foods, including meats, dairy products, and vegetables,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement issued on Sept. 13, 2019. “The FDA has been investigating NDMA and other nitrosamine impurities in blood pressure and heart failure medicines called Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) since last year. In the case of ARBs, the FDA has recommended numerous recalls as it discovered unacceptable levels of nitrosamines.”

Dr. Woodcock said that the agency is working with industry partners to determine whether the low levels of NDMA in ranitidine pose a risk to patients, and it plans to post that information when it becomes available. For now, “patients should be able to trust that their medicines are as safe as they can be and that the benefits of taking them outweigh any risk to their health,” she said. “Although NDMA may cause harm in large amounts, the levels the FDA is finding in ranitidine from preliminary tests barely exceed amounts you might expect to find in common foods.”

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that the FDA is not suggesting that individuals stop taking ranitidine at this time. “However, patients taking prescription ranitidine who wish to discontinue use should talk to their health care professional about other treatment options,” she said. “People taking OTC ranitidine could consider using other OTC medicines approved for their condition. There are multiple drugs on the market that are approved for the same or similar uses as ranitidine.”

She advised consumers and health care professionals to report any adverse reactions with ranitidine to the FDA’s MedWatch program to help the agency better understand the problem.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about GERD, including symptoms, testing, lifestyle modifications and drug treatments at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-gerd.

According to the Food and Drug Administration,

“NDMA is a known environmental contaminant and found in water and foods, including meats, dairy products, and vegetables,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement issued on Sept. 13, 2019. “The FDA has been investigating NDMA and other nitrosamine impurities in blood pressure and heart failure medicines called Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) since last year. In the case of ARBs, the FDA has recommended numerous recalls as it discovered unacceptable levels of nitrosamines.”

Dr. Woodcock said that the agency is working with industry partners to determine whether the low levels of NDMA in ranitidine pose a risk to patients, and it plans to post that information when it becomes available. For now, “patients should be able to trust that their medicines are as safe as they can be and that the benefits of taking them outweigh any risk to their health,” she said. “Although NDMA may cause harm in large amounts, the levels the FDA is finding in ranitidine from preliminary tests barely exceed amounts you might expect to find in common foods.”

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that the FDA is not suggesting that individuals stop taking ranitidine at this time. “However, patients taking prescription ranitidine who wish to discontinue use should talk to their health care professional about other treatment options,” she said. “People taking OTC ranitidine could consider using other OTC medicines approved for their condition. There are multiple drugs on the market that are approved for the same or similar uses as ranitidine.”

She advised consumers and health care professionals to report any adverse reactions with ranitidine to the FDA’s MedWatch program to help the agency better understand the problem.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about GERD, including symptoms, testing, lifestyle modifications and drug treatments at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-gerd.

Diagnosis and management of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia pose challenges

CHICAGO – Because gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia share several symptoms (e.g., upper abdominal pain, fullness, and bloating) and pathophysiological abnormalities (e.g., delayed gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation, and visceral hypersensitivity), it can be hard to distinguish the two conditions, according to a lecture presented at Freston Conference 2019, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Additional research into the role of diet in these conditions will improve the treatment of these patients, said Linda Nguyen, MD, director of neurogastroenterology and motility at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Distinguishing the disorders

The accepted definition of gastroparesis is abnormal gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction. The condition’s symptoms include nausea, vomiting, bloating, early satiety, abdominal pain, and weight loss. A previous consensus held that if a patient had abdominal pain, he or she did not have gastroparesis. Yet studies indicate that up to 80% of patients with gastroparesis have pain.

Functional dyspepsia is defined as bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain or burning in the absence of structural abnormality. The disorder can be subdivided into postprandial distress (i.e., meal-related symptomatology) and epigastric pain syndrome (i.e., pain or burning that may or may not be related to meals). Either of these alternatives may entail nausea and vomiting.

Comparing the pathophysiologies of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia helps to distinguish these disorders from each other. A 2019 review described rapid gastric emptying and duodenal eosinophilia in patients with functional dyspepsia, but not in patients with gastroparesis. Patients with epigastric pain syndrome had sensitivity to acid, bile, and fats. Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis, which is the most common type, had a weak antral pump and abnormal duodenal feedback, but patients with functional dyspepsia did not have these characteristics (J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25[1]:27-35).

Examining symptoms and severity

One examination of patients with gastroparesis found that approximately 46% of them had a body mass index of 25 or greater. About 26% of patients had a BMI greater than 30. Yet these patients were eating less than 60% of their recommended daily allowances, based on their age, height, weight, and sex (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9[12]:1056-64).

Accelerating gastric emptying may not relieve symptoms completely in a patient with gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen. A 2007 study of patients with gastroparesis found that 43% had impaired accommodation, and 29% had visceral hypersensitivity (Gut. 2007;56[1]:29-36). The same data indicated that gastric emptying time was not correlated with symptom severity. Impaired accommodation, however, was associated with early satiety and weight loss. Visceral hypersensitivity was associated with pain, early satiety, and weight loss. These data suggest that accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity may influence symptom severity in gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen.

Other researchers compared mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of early satiety in patients with gastroparesis. They found that patients with severe symptoms of early satiety have more delayed gastric emptying than do patients with mild or moderate symptoms of early satiety (Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29[4].).

Dr. Nguyen and colleagues examined normal gastric emptying, compared with severely delayed gastric emptying, which they defined as greater than 35% retention at 4 hours. They found that severely delayed gastric emptying was associated with more severe symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting, as measured by Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI). Extreme symptoms may help differentiate between gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia, said Dr. Nguyen.

Dietary and pharmacologic treatment

Although clinicians might consider recommending dietary modifications to treat gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia, the literature contains little evidence about their efficacy in these indications, said Dr. Nguyen. Based on a study by Tack and colleagues, some clinicians recommend small, frequent meals that are low in fat and low in fiber to patients with gastroparesis. Such a diet could be harmful, however, to patients with comorbid diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, or renal failure.

Common dietary recommendations for functional dyspepsia include small, frequent meals; decreased fat consumption; and avoidance of citrus and spicy foods. These recommendations are based on small studies in which patients reported which foods tended to cause their symptoms. Trials of dietary modifications in functional dyspepsia, however, are lacking.

Nevertheless, the literature can guide the selection of pharmacotherapy for these disorders. Talley et al. examined the effects of neuromodulators such as amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, and escitalopram in functional dyspepsia. About 70% of the sample had postprandial distress syndrome, and 20% met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis. Amitriptyline provided greater symptomatic relief to these patients than did placebo, but escitalopram did not. Patients who met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis did not respond well to tricyclic antidepressants, but patients with epigastric pain syndrome did. Furthermore, compared with patients with normal gastric emptying, those with delayed emptying did not respond to tricyclic antidepressants. A separate study found that the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline did not improve symptoms of gastroparesis (JAMA. 2013;310[24]:2640-9).

Promotility agents may be beneficial for certain patients. A study published this year suggests that, compared with placebo, prucalopride is effective for nausea, vomiting, fullness, bloating, and gastric emptying in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis (Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114[8]:1265-74.). A 2017 meta-analysis, however, found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective than promotility agents in patients with functional dyspepsia (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[7]:988-1013.).

Pyloric dysfunction may accompany gastroparesis in some patients. Increased severity of gastric emptying delay is associated with increased pylorospasm. Endoscopists have gained experience in performing pyloric myotomy, and this treatment has become more popular. Uncontrolled studies indicate that the proportion of patients with decreased symptom severity after this procedure is higher than 70% and can be as high as 86% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85[1]:123-8). The predictors of a good response include idiopathic etiology, male sex, moderate symptom severity, and greater delay in gastric emptying.

Functional dyspepsia should perhaps be understood as normal gastric emptying and symptoms of epigastric pain syndrome, said Dr. Nguyen. Those patients may respond to neuromodulators, she added. Idiopathic gastroparesis appears to be characterized by severe delay in gastric emptying, postprandial symptoms, nausea, and vomiting. “In the middle is the gray zone, where you have these patients with postprandial distress with or without delayed gastric emptying,” said Dr. Nguyen. Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis could be two ends of a spectrum, and the best management for patients with symptoms that occur in both disorders is unclear.

Help educate your patients about gastroparesis, its symptoms and causes, as well as testing and treatment using AGA patient education, which can be found in the GI Patient Center at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroparesis.

CHICAGO – Because gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia share several symptoms (e.g., upper abdominal pain, fullness, and bloating) and pathophysiological abnormalities (e.g., delayed gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation, and visceral hypersensitivity), it can be hard to distinguish the two conditions, according to a lecture presented at Freston Conference 2019, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Additional research into the role of diet in these conditions will improve the treatment of these patients, said Linda Nguyen, MD, director of neurogastroenterology and motility at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Distinguishing the disorders

The accepted definition of gastroparesis is abnormal gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction. The condition’s symptoms include nausea, vomiting, bloating, early satiety, abdominal pain, and weight loss. A previous consensus held that if a patient had abdominal pain, he or she did not have gastroparesis. Yet studies indicate that up to 80% of patients with gastroparesis have pain.

Functional dyspepsia is defined as bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain or burning in the absence of structural abnormality. The disorder can be subdivided into postprandial distress (i.e., meal-related symptomatology) and epigastric pain syndrome (i.e., pain or burning that may or may not be related to meals). Either of these alternatives may entail nausea and vomiting.

Comparing the pathophysiologies of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia helps to distinguish these disorders from each other. A 2019 review described rapid gastric emptying and duodenal eosinophilia in patients with functional dyspepsia, but not in patients with gastroparesis. Patients with epigastric pain syndrome had sensitivity to acid, bile, and fats. Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis, which is the most common type, had a weak antral pump and abnormal duodenal feedback, but patients with functional dyspepsia did not have these characteristics (J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25[1]:27-35).

Examining symptoms and severity

One examination of patients with gastroparesis found that approximately 46% of them had a body mass index of 25 or greater. About 26% of patients had a BMI greater than 30. Yet these patients were eating less than 60% of their recommended daily allowances, based on their age, height, weight, and sex (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9[12]:1056-64).

Accelerating gastric emptying may not relieve symptoms completely in a patient with gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen. A 2007 study of patients with gastroparesis found that 43% had impaired accommodation, and 29% had visceral hypersensitivity (Gut. 2007;56[1]:29-36). The same data indicated that gastric emptying time was not correlated with symptom severity. Impaired accommodation, however, was associated with early satiety and weight loss. Visceral hypersensitivity was associated with pain, early satiety, and weight loss. These data suggest that accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity may influence symptom severity in gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen.

Other researchers compared mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of early satiety in patients with gastroparesis. They found that patients with severe symptoms of early satiety have more delayed gastric emptying than do patients with mild or moderate symptoms of early satiety (Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29[4].).

Dr. Nguyen and colleagues examined normal gastric emptying, compared with severely delayed gastric emptying, which they defined as greater than 35% retention at 4 hours. They found that severely delayed gastric emptying was associated with more severe symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting, as measured by Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI). Extreme symptoms may help differentiate between gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia, said Dr. Nguyen.

Dietary and pharmacologic treatment

Although clinicians might consider recommending dietary modifications to treat gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia, the literature contains little evidence about their efficacy in these indications, said Dr. Nguyen. Based on a study by Tack and colleagues, some clinicians recommend small, frequent meals that are low in fat and low in fiber to patients with gastroparesis. Such a diet could be harmful, however, to patients with comorbid diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, or renal failure.

Common dietary recommendations for functional dyspepsia include small, frequent meals; decreased fat consumption; and avoidance of citrus and spicy foods. These recommendations are based on small studies in which patients reported which foods tended to cause their symptoms. Trials of dietary modifications in functional dyspepsia, however, are lacking.

Nevertheless, the literature can guide the selection of pharmacotherapy for these disorders. Talley et al. examined the effects of neuromodulators such as amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, and escitalopram in functional dyspepsia. About 70% of the sample had postprandial distress syndrome, and 20% met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis. Amitriptyline provided greater symptomatic relief to these patients than did placebo, but escitalopram did not. Patients who met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis did not respond well to tricyclic antidepressants, but patients with epigastric pain syndrome did. Furthermore, compared with patients with normal gastric emptying, those with delayed emptying did not respond to tricyclic antidepressants. A separate study found that the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline did not improve symptoms of gastroparesis (JAMA. 2013;310[24]:2640-9).

Promotility agents may be beneficial for certain patients. A study published this year suggests that, compared with placebo, prucalopride is effective for nausea, vomiting, fullness, bloating, and gastric emptying in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis (Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114[8]:1265-74.). A 2017 meta-analysis, however, found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective than promotility agents in patients with functional dyspepsia (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[7]:988-1013.).

Pyloric dysfunction may accompany gastroparesis in some patients. Increased severity of gastric emptying delay is associated with increased pylorospasm. Endoscopists have gained experience in performing pyloric myotomy, and this treatment has become more popular. Uncontrolled studies indicate that the proportion of patients with decreased symptom severity after this procedure is higher than 70% and can be as high as 86% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85[1]:123-8). The predictors of a good response include idiopathic etiology, male sex, moderate symptom severity, and greater delay in gastric emptying.

Functional dyspepsia should perhaps be understood as normal gastric emptying and symptoms of epigastric pain syndrome, said Dr. Nguyen. Those patients may respond to neuromodulators, she added. Idiopathic gastroparesis appears to be characterized by severe delay in gastric emptying, postprandial symptoms, nausea, and vomiting. “In the middle is the gray zone, where you have these patients with postprandial distress with or without delayed gastric emptying,” said Dr. Nguyen. Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis could be two ends of a spectrum, and the best management for patients with symptoms that occur in both disorders is unclear.

Help educate your patients about gastroparesis, its symptoms and causes, as well as testing and treatment using AGA patient education, which can be found in the GI Patient Center at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroparesis.

CHICAGO – Because gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia share several symptoms (e.g., upper abdominal pain, fullness, and bloating) and pathophysiological abnormalities (e.g., delayed gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation, and visceral hypersensitivity), it can be hard to distinguish the two conditions, according to a lecture presented at Freston Conference 2019, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Additional research into the role of diet in these conditions will improve the treatment of these patients, said Linda Nguyen, MD, director of neurogastroenterology and motility at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Distinguishing the disorders

The accepted definition of gastroparesis is abnormal gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction. The condition’s symptoms include nausea, vomiting, bloating, early satiety, abdominal pain, and weight loss. A previous consensus held that if a patient had abdominal pain, he or she did not have gastroparesis. Yet studies indicate that up to 80% of patients with gastroparesis have pain.

Functional dyspepsia is defined as bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain or burning in the absence of structural abnormality. The disorder can be subdivided into postprandial distress (i.e., meal-related symptomatology) and epigastric pain syndrome (i.e., pain or burning that may or may not be related to meals). Either of these alternatives may entail nausea and vomiting.

Comparing the pathophysiologies of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia helps to distinguish these disorders from each other. A 2019 review described rapid gastric emptying and duodenal eosinophilia in patients with functional dyspepsia, but not in patients with gastroparesis. Patients with epigastric pain syndrome had sensitivity to acid, bile, and fats. Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis, which is the most common type, had a weak antral pump and abnormal duodenal feedback, but patients with functional dyspepsia did not have these characteristics (J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25[1]:27-35).

Examining symptoms and severity

One examination of patients with gastroparesis found that approximately 46% of them had a body mass index of 25 or greater. About 26% of patients had a BMI greater than 30. Yet these patients were eating less than 60% of their recommended daily allowances, based on their age, height, weight, and sex (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9[12]:1056-64).

Accelerating gastric emptying may not relieve symptoms completely in a patient with gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen. A 2007 study of patients with gastroparesis found that 43% had impaired accommodation, and 29% had visceral hypersensitivity (Gut. 2007;56[1]:29-36). The same data indicated that gastric emptying time was not correlated with symptom severity. Impaired accommodation, however, was associated with early satiety and weight loss. Visceral hypersensitivity was associated with pain, early satiety, and weight loss. These data suggest that accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity may influence symptom severity in gastroparesis, said Dr. Nguyen.

Other researchers compared mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of early satiety in patients with gastroparesis. They found that patients with severe symptoms of early satiety have more delayed gastric emptying than do patients with mild or moderate symptoms of early satiety (Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29[4].).

Dr. Nguyen and colleagues examined normal gastric emptying, compared with severely delayed gastric emptying, which they defined as greater than 35% retention at 4 hours. They found that severely delayed gastric emptying was associated with more severe symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting, as measured by Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI). Extreme symptoms may help differentiate between gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia, said Dr. Nguyen.

Dietary and pharmacologic treatment

Although clinicians might consider recommending dietary modifications to treat gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia, the literature contains little evidence about their efficacy in these indications, said Dr. Nguyen. Based on a study by Tack and colleagues, some clinicians recommend small, frequent meals that are low in fat and low in fiber to patients with gastroparesis. Such a diet could be harmful, however, to patients with comorbid diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, or renal failure.

Common dietary recommendations for functional dyspepsia include small, frequent meals; decreased fat consumption; and avoidance of citrus and spicy foods. These recommendations are based on small studies in which patients reported which foods tended to cause their symptoms. Trials of dietary modifications in functional dyspepsia, however, are lacking.

Nevertheless, the literature can guide the selection of pharmacotherapy for these disorders. Talley et al. examined the effects of neuromodulators such as amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, and escitalopram in functional dyspepsia. About 70% of the sample had postprandial distress syndrome, and 20% met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis. Amitriptyline provided greater symptomatic relief to these patients than did placebo, but escitalopram did not. Patients who met criteria for idiopathic gastroparesis did not respond well to tricyclic antidepressants, but patients with epigastric pain syndrome did. Furthermore, compared with patients with normal gastric emptying, those with delayed emptying did not respond to tricyclic antidepressants. A separate study found that the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline did not improve symptoms of gastroparesis (JAMA. 2013;310[24]:2640-9).

Promotility agents may be beneficial for certain patients. A study published this year suggests that, compared with placebo, prucalopride is effective for nausea, vomiting, fullness, bloating, and gastric emptying in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis (Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114[8]:1265-74.). A 2017 meta-analysis, however, found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective than promotility agents in patients with functional dyspepsia (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[7]:988-1013.).

Pyloric dysfunction may accompany gastroparesis in some patients. Increased severity of gastric emptying delay is associated with increased pylorospasm. Endoscopists have gained experience in performing pyloric myotomy, and this treatment has become more popular. Uncontrolled studies indicate that the proportion of patients with decreased symptom severity after this procedure is higher than 70% and can be as high as 86% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85[1]:123-8). The predictors of a good response include idiopathic etiology, male sex, moderate symptom severity, and greater delay in gastric emptying.

Functional dyspepsia should perhaps be understood as normal gastric emptying and symptoms of epigastric pain syndrome, said Dr. Nguyen. Those patients may respond to neuromodulators, she added. Idiopathic gastroparesis appears to be characterized by severe delay in gastric emptying, postprandial symptoms, nausea, and vomiting. “In the middle is the gray zone, where you have these patients with postprandial distress with or without delayed gastric emptying,” said Dr. Nguyen. Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis could be two ends of a spectrum, and the best management for patients with symptoms that occur in both disorders is unclear.

Help educate your patients about gastroparesis, its symptoms and causes, as well as testing and treatment using AGA patient education, which can be found in the GI Patient Center at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/gastroparesis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FRESTON CONFERENCE 2019

Endoscopic therapy decreases recurrence of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus

A study of patients with Barrett’s esophagus found that, although intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in the cardia were common before treatment, they were more frequently present at higher levels and successful endoscopic eradication therapy lessened the risk.

“The results of this study provide evidence to suggest that, in Barrett’s esophagus patients who have achieved CEIM [complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia], it is sufficient to perform a close examination of the cardia and, in the absence of visible abnormalities, to randomly biopsy only at the level of TGF [top of gastric folds], rather than deeper into the cardia, during surveillance exams,” wrote Swathi Eluri, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia of patients with Barrett’s esophagus who successfully underwent endoscopic eradication therapy (EET), along with the incidence of cardia intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in patients undergoing EET, this single-center study examined two groups: a cross-sectional group of 116 patients who had achieved CEIM, and a longitudinal group of 42 treatment-naive patients who were receiving EET and subsequently achieved CEIM.

Along with clinical biopsies, the cross-sectional group underwent standardized biopsies from four quadrants in four locations: the distal esophagus, 1 cm proximal to top of gastric folds (TGF–1); at TGF; 1 cm into the gastric cardia (TGF+1); and 2 cm into the cardia (TGF+2). The longitudinal group also underwent 16 biopsies in the same areas; after CEIM was achieved, they underwent standard research biopsies of the distal esophagus and cardia at 6- and 18-month follow-ups.

Within the cross-sectional group, 15% of patients (n = 17) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia after CEIM. Of those 17 patients, 12 had intestinal metaplasia, 2 were indefinite for dysplasia, and 3 had low-grade dysplasia. Of the 12 patients with cardia intestinal metaplasia, 83% had it at the level of TGF; 50% at TGF+1; and 25% at TGF+2.

Within the longitudinal group, 28% of patients (n = 12) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia before ablation. Of those 12 patients, 9 had dysplastic intestinal metaplasia. Cases of pretreatment dysplasia were all found at the level of TGF, with one case extended to TGF+1. All patients achieved CEIM; at 18 months post CEIM, two patients had intestinal metaplasia and none had dysplasia.

The authors shared their study’s limitations, which included the lack of generalizability of a single-center study and a notable number of dropouts in the longitudinal group. They also acknowledged using multiple ablation modalities, although they added that most patients in both groups underwent radiofrequency ablation, the most commonly used treatment method and one that made “the results of the study more applicable to real-world practice.”

In turn, the authors noted their study’s strengths, which included the collection of data in a standardized manner and the availability of complete ablation history for all patients. Theirs was also the first study to systematically sample the cardia at multiple levels, which allows for “a more granular understanding of the location of initial and incident cardia lesions, which can guide depth of ablation during EET.”

The study was funded by an American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award and CSA Medical. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eluri S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.065.

A study of patients with Barrett’s esophagus found that, although intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in the cardia were common before treatment, they were more frequently present at higher levels and successful endoscopic eradication therapy lessened the risk.

“The results of this study provide evidence to suggest that, in Barrett’s esophagus patients who have achieved CEIM [complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia], it is sufficient to perform a close examination of the cardia and, in the absence of visible abnormalities, to randomly biopsy only at the level of TGF [top of gastric folds], rather than deeper into the cardia, during surveillance exams,” wrote Swathi Eluri, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia of patients with Barrett’s esophagus who successfully underwent endoscopic eradication therapy (EET), along with the incidence of cardia intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in patients undergoing EET, this single-center study examined two groups: a cross-sectional group of 116 patients who had achieved CEIM, and a longitudinal group of 42 treatment-naive patients who were receiving EET and subsequently achieved CEIM.

Along with clinical biopsies, the cross-sectional group underwent standardized biopsies from four quadrants in four locations: the distal esophagus, 1 cm proximal to top of gastric folds (TGF–1); at TGF; 1 cm into the gastric cardia (TGF+1); and 2 cm into the cardia (TGF+2). The longitudinal group also underwent 16 biopsies in the same areas; after CEIM was achieved, they underwent standard research biopsies of the distal esophagus and cardia at 6- and 18-month follow-ups.

Within the cross-sectional group, 15% of patients (n = 17) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia after CEIM. Of those 17 patients, 12 had intestinal metaplasia, 2 were indefinite for dysplasia, and 3 had low-grade dysplasia. Of the 12 patients with cardia intestinal metaplasia, 83% had it at the level of TGF; 50% at TGF+1; and 25% at TGF+2.

Within the longitudinal group, 28% of patients (n = 12) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia before ablation. Of those 12 patients, 9 had dysplastic intestinal metaplasia. Cases of pretreatment dysplasia were all found at the level of TGF, with one case extended to TGF+1. All patients achieved CEIM; at 18 months post CEIM, two patients had intestinal metaplasia and none had dysplasia.

The authors shared their study’s limitations, which included the lack of generalizability of a single-center study and a notable number of dropouts in the longitudinal group. They also acknowledged using multiple ablation modalities, although they added that most patients in both groups underwent radiofrequency ablation, the most commonly used treatment method and one that made “the results of the study more applicable to real-world practice.”

In turn, the authors noted their study’s strengths, which included the collection of data in a standardized manner and the availability of complete ablation history for all patients. Theirs was also the first study to systematically sample the cardia at multiple levels, which allows for “a more granular understanding of the location of initial and incident cardia lesions, which can guide depth of ablation during EET.”

The study was funded by an American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award and CSA Medical. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eluri S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.065.

A study of patients with Barrett’s esophagus found that, although intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in the cardia were common before treatment, they were more frequently present at higher levels and successful endoscopic eradication therapy lessened the risk.

“The results of this study provide evidence to suggest that, in Barrett’s esophagus patients who have achieved CEIM [complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia], it is sufficient to perform a close examination of the cardia and, in the absence of visible abnormalities, to randomly biopsy only at the level of TGF [top of gastric folds], rather than deeper into the cardia, during surveillance exams,” wrote Swathi Eluri, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and coauthors. The study was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To determine the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia of patients with Barrett’s esophagus who successfully underwent endoscopic eradication therapy (EET), along with the incidence of cardia intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in patients undergoing EET, this single-center study examined two groups: a cross-sectional group of 116 patients who had achieved CEIM, and a longitudinal group of 42 treatment-naive patients who were receiving EET and subsequently achieved CEIM.

Along with clinical biopsies, the cross-sectional group underwent standardized biopsies from four quadrants in four locations: the distal esophagus, 1 cm proximal to top of gastric folds (TGF–1); at TGF; 1 cm into the gastric cardia (TGF+1); and 2 cm into the cardia (TGF+2). The longitudinal group also underwent 16 biopsies in the same areas; after CEIM was achieved, they underwent standard research biopsies of the distal esophagus and cardia at 6- and 18-month follow-ups.

Within the cross-sectional group, 15% of patients (n = 17) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia after CEIM. Of those 17 patients, 12 had intestinal metaplasia, 2 were indefinite for dysplasia, and 3 had low-grade dysplasia. Of the 12 patients with cardia intestinal metaplasia, 83% had it at the level of TGF; 50% at TGF+1; and 25% at TGF+2.

Within the longitudinal group, 28% of patients (n = 12) had intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in the cardia before ablation. Of those 12 patients, 9 had dysplastic intestinal metaplasia. Cases of pretreatment dysplasia were all found at the level of TGF, with one case extended to TGF+1. All patients achieved CEIM; at 18 months post CEIM, two patients had intestinal metaplasia and none had dysplasia.

The authors shared their study’s limitations, which included the lack of generalizability of a single-center study and a notable number of dropouts in the longitudinal group. They also acknowledged using multiple ablation modalities, although they added that most patients in both groups underwent radiofrequency ablation, the most commonly used treatment method and one that made “the results of the study more applicable to real-world practice.”

In turn, the authors noted their study’s strengths, which included the collection of data in a standardized manner and the availability of complete ablation history for all patients. Theirs was also the first study to systematically sample the cardia at multiple levels, which allows for “a more granular understanding of the location of initial and incident cardia lesions, which can guide depth of ablation during EET.”

The study was funded by an American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award and CSA Medical. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Eluri S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.065.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Can dietary therapies treat GERD effectively?

CHICAGO – , according to an overview presented at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Modifying diet may reduce lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and decrease the number of reflux events. Prescribing an overly restrictive diet, however, can promote hypervigilance and overwhelm patients. Successful dietary therapy requires balancing expectations and maintaining cognitive flexibility, said John E. Pandolfino, MD, Hans Popper Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

When a patient presents with GERD and does not have warning signs such as dysphagia or odynophagia, the initial treatment typically is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). This therapy effectively reduces the acidity of the gastric juice and improves acid clearance. It does not, however, change the number of reflux events or affect tissue permeability, said Dr. Pandolfino. Dietary therapy has the potential to address these outcomes.

Diets can facilitate weight loss

The first mechanism by which dietary therapies reduce GERD is by facilitating weight loss. “Obesity is associated with reflux. If you reduce that gastroesophageal pressure gradient that is generated by truncal obesity, you will improve reflux,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Second, reducing the intake of alcohol, coffee, or carbohydrates can decrease the acidity of the gastric juice. Certain foods can reduce the number of reflux events, and others can strengthen the LES.

The increasing incidence of obesity is associated with increasing incidence of GERD. Exacerbations of GERD increase the number of transient LES relaxations (TLESRs), increase the amount of liquid refluxate, and promote the formation of a hiatus hernia, said Dr. Pandolfino. One study found that moderate weight gain can cause or worsen reflux symptoms among patients of normal weight (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[22]:2340-8.). Weight loss was associated with a decreased risk of GERD symptoms. Another analysis found that reducing body mass index by 3.5 points is associated with “a dramatic reduction in overall symptoms,” said Dr. Pandolfino (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108[3]:376-82). Weight loss enhanced the effects of medication and reduced the gastroesophageal pressure gradient.

Dr. Pandolfino and colleagues developed and studied the Reflux Improvement and Monitoring (TRIM) program as a treatment for GERD. In this program, patients with GERD who had a BMI above 30 and were taking a PPI were referred to health coaches for weight loss treatment. Participants’ GERD Q scores decreased from 8.7 at baseline to 7.5 at 3 months and 7.4 at 6 months. Furthermore, percentage of excess body weight continued to decline for 12 months among patients who participated in TRIM, compared with controls (Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113[1]:23-30.).

“These patients learn healthier habits [such as] walking a little bit more and watching the overall volume of food that they’re taking in,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “This was a simple thing to focus on, diet and exercise, that dramatically reduced overall severity of reflux. The interesting thing here is that we got 30% of people off their PPI therapy.”

Lifestyle changes may benefit patients

Several common lifestyle recommendations for patients with GERD relate to diet. Such recommendations include avoiding alcohol; eating smaller, more frequent meals; and avoiding food within 3 hours of bedtime. But data suggest that it is not effective to recommend the avoidance of acidic or irritative foods (e.g., citrus fruits, tomatoes, and carbonated beverages) or refluxogenic foods (e.g., fatty or fried foods, coffee, and chocolate) to all patients. Genetic predispositions may cause these foods to be irritants to certain patients, but “I don’t globally tell people to avoid things unless they irritate them,” said Dr. Pandolfino.

Understanding the mechanism by which certain foods trigger GERD can aid in appropriate therapy. For example, coffee can reduce LES pressure and increase gastric acid production. “If you have someone who already has low LES pressure, reducing coffee consumption might help that patient,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Data suggest that certain elimination diets are ineffective, however. Clinical trials do not suggest that eliminating carbonated beverages affects symptoms, and the data about eliminating alcohol, citrus, spicy foods, and chocolate are conflicting (Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19[8]:38.).

In a 2018 study, investigators gave patients with GERD 5 g of psyllium t.i.d. They performed physiologic testing on the patients at baseline and after 10 days of the diet. The intervention was associated with a significant increase in LES pressure and a reduction in overall reflux (World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24[21]:2291-9.). “This was one of the first studies that showed a dramatic improvement in physiology,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “Certainly, this is provocative, and I think that this is not an unreasonable thing to do in someone who’s not getting enough fiber.”

In addition to improving cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the Mediterranean diet reduces reflux symptoms and complications. When the researchers controlled for eating habits, the association persisted (Dis Esophagus. 2016;29[7]:794-800.).

Optimal GERD therapy follows from an analysis of patient-centered foci, such as obesity and triggers, and specific functional defects. In the quest for personalized therapy, a clinician should not discount the underlying pathogenesis, because some patients may require medications or surgery, said Dr. Pandolfino.

CHICAGO – , according to an overview presented at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Modifying diet may reduce lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and decrease the number of reflux events. Prescribing an overly restrictive diet, however, can promote hypervigilance and overwhelm patients. Successful dietary therapy requires balancing expectations and maintaining cognitive flexibility, said John E. Pandolfino, MD, Hans Popper Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

When a patient presents with GERD and does not have warning signs such as dysphagia or odynophagia, the initial treatment typically is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). This therapy effectively reduces the acidity of the gastric juice and improves acid clearance. It does not, however, change the number of reflux events or affect tissue permeability, said Dr. Pandolfino. Dietary therapy has the potential to address these outcomes.

Diets can facilitate weight loss

The first mechanism by which dietary therapies reduce GERD is by facilitating weight loss. “Obesity is associated with reflux. If you reduce that gastroesophageal pressure gradient that is generated by truncal obesity, you will improve reflux,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Second, reducing the intake of alcohol, coffee, or carbohydrates can decrease the acidity of the gastric juice. Certain foods can reduce the number of reflux events, and others can strengthen the LES.

The increasing incidence of obesity is associated with increasing incidence of GERD. Exacerbations of GERD increase the number of transient LES relaxations (TLESRs), increase the amount of liquid refluxate, and promote the formation of a hiatus hernia, said Dr. Pandolfino. One study found that moderate weight gain can cause or worsen reflux symptoms among patients of normal weight (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[22]:2340-8.). Weight loss was associated with a decreased risk of GERD symptoms. Another analysis found that reducing body mass index by 3.5 points is associated with “a dramatic reduction in overall symptoms,” said Dr. Pandolfino (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108[3]:376-82). Weight loss enhanced the effects of medication and reduced the gastroesophageal pressure gradient.

Dr. Pandolfino and colleagues developed and studied the Reflux Improvement and Monitoring (TRIM) program as a treatment for GERD. In this program, patients with GERD who had a BMI above 30 and were taking a PPI were referred to health coaches for weight loss treatment. Participants’ GERD Q scores decreased from 8.7 at baseline to 7.5 at 3 months and 7.4 at 6 months. Furthermore, percentage of excess body weight continued to decline for 12 months among patients who participated in TRIM, compared with controls (Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113[1]:23-30.).

“These patients learn healthier habits [such as] walking a little bit more and watching the overall volume of food that they’re taking in,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “This was a simple thing to focus on, diet and exercise, that dramatically reduced overall severity of reflux. The interesting thing here is that we got 30% of people off their PPI therapy.”

Lifestyle changes may benefit patients

Several common lifestyle recommendations for patients with GERD relate to diet. Such recommendations include avoiding alcohol; eating smaller, more frequent meals; and avoiding food within 3 hours of bedtime. But data suggest that it is not effective to recommend the avoidance of acidic or irritative foods (e.g., citrus fruits, tomatoes, and carbonated beverages) or refluxogenic foods (e.g., fatty or fried foods, coffee, and chocolate) to all patients. Genetic predispositions may cause these foods to be irritants to certain patients, but “I don’t globally tell people to avoid things unless they irritate them,” said Dr. Pandolfino.

Understanding the mechanism by which certain foods trigger GERD can aid in appropriate therapy. For example, coffee can reduce LES pressure and increase gastric acid production. “If you have someone who already has low LES pressure, reducing coffee consumption might help that patient,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Data suggest that certain elimination diets are ineffective, however. Clinical trials do not suggest that eliminating carbonated beverages affects symptoms, and the data about eliminating alcohol, citrus, spicy foods, and chocolate are conflicting (Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19[8]:38.).

In a 2018 study, investigators gave patients with GERD 5 g of psyllium t.i.d. They performed physiologic testing on the patients at baseline and after 10 days of the diet. The intervention was associated with a significant increase in LES pressure and a reduction in overall reflux (World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24[21]:2291-9.). “This was one of the first studies that showed a dramatic improvement in physiology,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “Certainly, this is provocative, and I think that this is not an unreasonable thing to do in someone who’s not getting enough fiber.”

In addition to improving cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the Mediterranean diet reduces reflux symptoms and complications. When the researchers controlled for eating habits, the association persisted (Dis Esophagus. 2016;29[7]:794-800.).

Optimal GERD therapy follows from an analysis of patient-centered foci, such as obesity and triggers, and specific functional defects. In the quest for personalized therapy, a clinician should not discount the underlying pathogenesis, because some patients may require medications or surgery, said Dr. Pandolfino.

CHICAGO – , according to an overview presented at the meeting, sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association. Modifying diet may reduce lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and decrease the number of reflux events. Prescribing an overly restrictive diet, however, can promote hypervigilance and overwhelm patients. Successful dietary therapy requires balancing expectations and maintaining cognitive flexibility, said John E. Pandolfino, MD, Hans Popper Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

When a patient presents with GERD and does not have warning signs such as dysphagia or odynophagia, the initial treatment typically is a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). This therapy effectively reduces the acidity of the gastric juice and improves acid clearance. It does not, however, change the number of reflux events or affect tissue permeability, said Dr. Pandolfino. Dietary therapy has the potential to address these outcomes.

Diets can facilitate weight loss

The first mechanism by which dietary therapies reduce GERD is by facilitating weight loss. “Obesity is associated with reflux. If you reduce that gastroesophageal pressure gradient that is generated by truncal obesity, you will improve reflux,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Second, reducing the intake of alcohol, coffee, or carbohydrates can decrease the acidity of the gastric juice. Certain foods can reduce the number of reflux events, and others can strengthen the LES.

The increasing incidence of obesity is associated with increasing incidence of GERD. Exacerbations of GERD increase the number of transient LES relaxations (TLESRs), increase the amount of liquid refluxate, and promote the formation of a hiatus hernia, said Dr. Pandolfino. One study found that moderate weight gain can cause or worsen reflux symptoms among patients of normal weight (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[22]:2340-8.). Weight loss was associated with a decreased risk of GERD symptoms. Another analysis found that reducing body mass index by 3.5 points is associated with “a dramatic reduction in overall symptoms,” said Dr. Pandolfino (Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108[3]:376-82). Weight loss enhanced the effects of medication and reduced the gastroesophageal pressure gradient.

Dr. Pandolfino and colleagues developed and studied the Reflux Improvement and Monitoring (TRIM) program as a treatment for GERD. In this program, patients with GERD who had a BMI above 30 and were taking a PPI were referred to health coaches for weight loss treatment. Participants’ GERD Q scores decreased from 8.7 at baseline to 7.5 at 3 months and 7.4 at 6 months. Furthermore, percentage of excess body weight continued to decline for 12 months among patients who participated in TRIM, compared with controls (Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113[1]:23-30.).

“These patients learn healthier habits [such as] walking a little bit more and watching the overall volume of food that they’re taking in,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “This was a simple thing to focus on, diet and exercise, that dramatically reduced overall severity of reflux. The interesting thing here is that we got 30% of people off their PPI therapy.”

Lifestyle changes may benefit patients

Several common lifestyle recommendations for patients with GERD relate to diet. Such recommendations include avoiding alcohol; eating smaller, more frequent meals; and avoiding food within 3 hours of bedtime. But data suggest that it is not effective to recommend the avoidance of acidic or irritative foods (e.g., citrus fruits, tomatoes, and carbonated beverages) or refluxogenic foods (e.g., fatty or fried foods, coffee, and chocolate) to all patients. Genetic predispositions may cause these foods to be irritants to certain patients, but “I don’t globally tell people to avoid things unless they irritate them,” said Dr. Pandolfino.

Understanding the mechanism by which certain foods trigger GERD can aid in appropriate therapy. For example, coffee can reduce LES pressure and increase gastric acid production. “If you have someone who already has low LES pressure, reducing coffee consumption might help that patient,” said Dr. Pandolfino. Data suggest that certain elimination diets are ineffective, however. Clinical trials do not suggest that eliminating carbonated beverages affects symptoms, and the data about eliminating alcohol, citrus, spicy foods, and chocolate are conflicting (Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19[8]:38.).

In a 2018 study, investigators gave patients with GERD 5 g of psyllium t.i.d. They performed physiologic testing on the patients at baseline and after 10 days of the diet. The intervention was associated with a significant increase in LES pressure and a reduction in overall reflux (World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24[21]:2291-9.). “This was one of the first studies that showed a dramatic improvement in physiology,” said Dr. Pandolfino. “Certainly, this is provocative, and I think that this is not an unreasonable thing to do in someone who’s not getting enough fiber.”

In addition to improving cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the Mediterranean diet reduces reflux symptoms and complications. When the researchers controlled for eating habits, the association persisted (Dis Esophagus. 2016;29[7]:794-800.).

Optimal GERD therapy follows from an analysis of patient-centered foci, such as obesity and triggers, and specific functional defects. In the quest for personalized therapy, a clinician should not discount the underlying pathogenesis, because some patients may require medications or surgery, said Dr. Pandolfino.

REPORTING FROM FRESTON CONFERENCE 2019

Developments in gastric cancer

In the United States, gastric cancer accounts for 1.6% of all cancers with an estimated 27,510 cases in 2019 per the SEER database. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has been decreasing in the United States, there have been alarming trends, suggesting an increased rate in select populations, especially in the young Hispanic population in the age group of 20-49 years (SEER Cancer Statistics Review [CSR] 1975-2015).

Risk factors for gastric cancer include increasing age, male sex, presence of intestinal metaplasia, and varying degrees of dysplasia (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88). Gastric cancer is primarily characterized into two subtypes: intestinal type, which is the more common type associated with gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and the diffuse type, which is genetically determined.

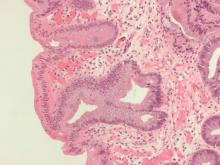

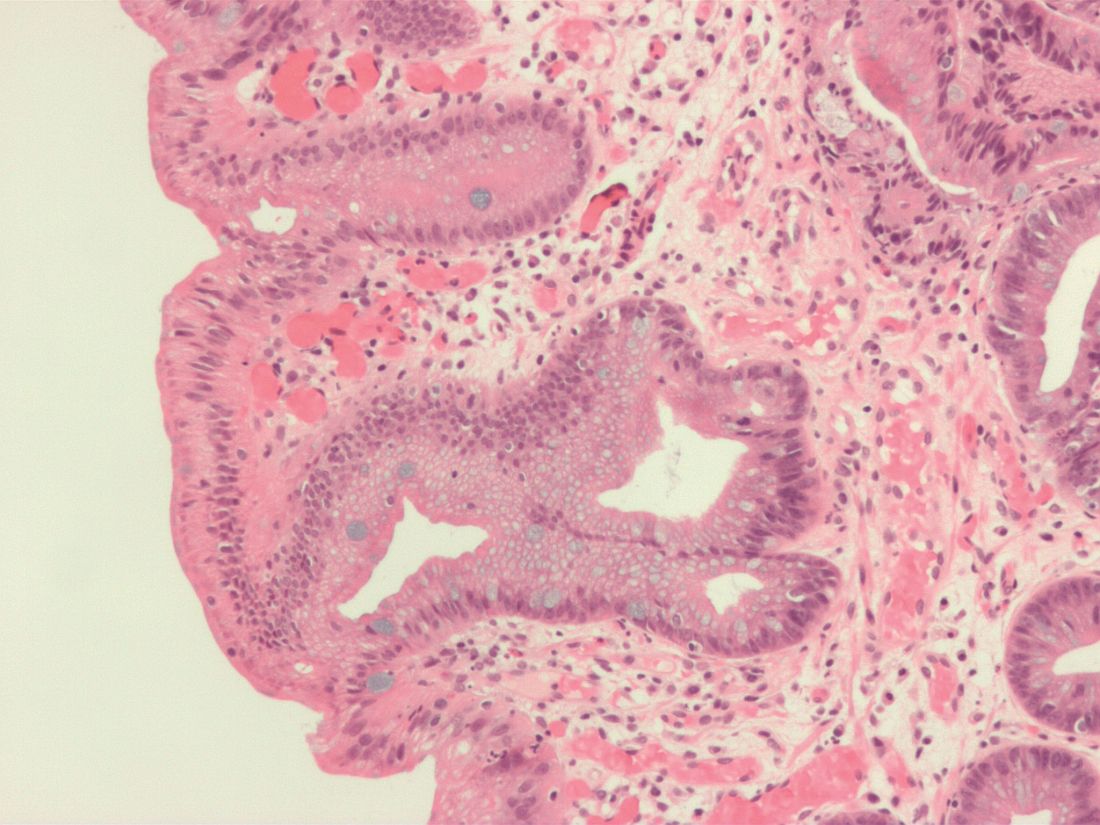

GIM, a precancerous lesion, is defined as the replacement of the normal gastric mucosa by intestinal epithelium and can be limited (confined to one region of the stomach) or extensive (involving more than two regions of the stomach). Risk factors for GIM include Helicobacter pylori infection, age, smoking status, and presence of a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. Histologically, GIM is characterized as either complete – defined as the presence of small intestinal-type mucosa with mature absorptive cells, goblet cells, and a brush border – or incomplete – with columnar “intermediate” cells in various stages of differentiation, irregular mucin droplets, without a brush border. Extensive and incomplete type of GIM is associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88).

Gastric cancer screening has been shown to be effective in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. However, in low-incidence countries, at-risk patients can be identified based on epidemiology, genetics, and environmental risk factors as well as incidence of H. pylori, and serologic markers of chronic inflammation such as pepsinogen, and gastrin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[5]:704-15). H. pylori eradication has been shown to reduce the risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with H. pylori-associated GIM. For detection of dysplasia and early gastric cancer, patients with GIM should undergo a full systematic endoscopy protocol of the stomach with clear photographic documentation of gastric regions and pathology.

On standard white-light endoscopy, GIM appears as small gray-white, slightly elevated plaques surrounded by mixed patchy pink and pale areas of mucosa causing an irregular uneven surface. Sometimes GIM can present as patchy erythema with mottling.

On the other hand, presence of features such as differences in color, loss of vascularity, elevation or depression, nodularity or thickening, and abnormal convergence or flattening of folds should raise suspicion for gastric dysplasia or early gastric cancer. Presence of GIM on endoscopy should be documented in detail with photographic evidence including the location and extent of GIM, and obtaining mapping biopsies that include at least two biopsies from the antrum (from lesser and greater curve) and from the body (lesser and greater curve). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended every 3 years in patients with extensive GIM affecting the antrum and body, incomplete GIM, and a family history of gastric cancer.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Sharma is professor of medicine and director of fellowship training, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Kansas, Kansas City.

In the United States, gastric cancer accounts for 1.6% of all cancers with an estimated 27,510 cases in 2019 per the SEER database. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has been decreasing in the United States, there have been alarming trends, suggesting an increased rate in select populations, especially in the young Hispanic population in the age group of 20-49 years (SEER Cancer Statistics Review [CSR] 1975-2015).

Risk factors for gastric cancer include increasing age, male sex, presence of intestinal metaplasia, and varying degrees of dysplasia (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88). Gastric cancer is primarily characterized into two subtypes: intestinal type, which is the more common type associated with gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and the diffuse type, which is genetically determined.

GIM, a precancerous lesion, is defined as the replacement of the normal gastric mucosa by intestinal epithelium and can be limited (confined to one region of the stomach) or extensive (involving more than two regions of the stomach). Risk factors for GIM include Helicobacter pylori infection, age, smoking status, and presence of a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. Histologically, GIM is characterized as either complete – defined as the presence of small intestinal-type mucosa with mature absorptive cells, goblet cells, and a brush border – or incomplete – with columnar “intermediate” cells in various stages of differentiation, irregular mucin droplets, without a brush border. Extensive and incomplete type of GIM is associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88).

Gastric cancer screening has been shown to be effective in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. However, in low-incidence countries, at-risk patients can be identified based on epidemiology, genetics, and environmental risk factors as well as incidence of H. pylori, and serologic markers of chronic inflammation such as pepsinogen, and gastrin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[5]:704-15). H. pylori eradication has been shown to reduce the risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with H. pylori-associated GIM. For detection of dysplasia and early gastric cancer, patients with GIM should undergo a full systematic endoscopy protocol of the stomach with clear photographic documentation of gastric regions and pathology.

On standard white-light endoscopy, GIM appears as small gray-white, slightly elevated plaques surrounded by mixed patchy pink and pale areas of mucosa causing an irregular uneven surface. Sometimes GIM can present as patchy erythema with mottling.

On the other hand, presence of features such as differences in color, loss of vascularity, elevation or depression, nodularity or thickening, and abnormal convergence or flattening of folds should raise suspicion for gastric dysplasia or early gastric cancer. Presence of GIM on endoscopy should be documented in detail with photographic evidence including the location and extent of GIM, and obtaining mapping biopsies that include at least two biopsies from the antrum (from lesser and greater curve) and from the body (lesser and greater curve). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended every 3 years in patients with extensive GIM affecting the antrum and body, incomplete GIM, and a family history of gastric cancer.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Sharma is professor of medicine and director of fellowship training, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Kansas, Kansas City.

In the United States, gastric cancer accounts for 1.6% of all cancers with an estimated 27,510 cases in 2019 per the SEER database. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has been decreasing in the United States, there have been alarming trends, suggesting an increased rate in select populations, especially in the young Hispanic population in the age group of 20-49 years (SEER Cancer Statistics Review [CSR] 1975-2015).

Risk factors for gastric cancer include increasing age, male sex, presence of intestinal metaplasia, and varying degrees of dysplasia (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88). Gastric cancer is primarily characterized into two subtypes: intestinal type, which is the more common type associated with gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and the diffuse type, which is genetically determined.

GIM, a precancerous lesion, is defined as the replacement of the normal gastric mucosa by intestinal epithelium and can be limited (confined to one region of the stomach) or extensive (involving more than two regions of the stomach). Risk factors for GIM include Helicobacter pylori infection, age, smoking status, and presence of a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. Histologically, GIM is characterized as either complete – defined as the presence of small intestinal-type mucosa with mature absorptive cells, goblet cells, and a brush border – or incomplete – with columnar “intermediate” cells in various stages of differentiation, irregular mucin droplets, without a brush border. Extensive and incomplete type of GIM is associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer (Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365-88).

Gastric cancer screening has been shown to be effective in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. However, in low-incidence countries, at-risk patients can be identified based on epidemiology, genetics, and environmental risk factors as well as incidence of H. pylori, and serologic markers of chronic inflammation such as pepsinogen, and gastrin (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112[5]:704-15). H. pylori eradication has been shown to reduce the risk of developing gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with H. pylori-associated GIM. For detection of dysplasia and early gastric cancer, patients with GIM should undergo a full systematic endoscopy protocol of the stomach with clear photographic documentation of gastric regions and pathology.

On standard white-light endoscopy, GIM appears as small gray-white, slightly elevated plaques surrounded by mixed patchy pink and pale areas of mucosa causing an irregular uneven surface. Sometimes GIM can present as patchy erythema with mottling.

On the other hand, presence of features such as differences in color, loss of vascularity, elevation or depression, nodularity or thickening, and abnormal convergence or flattening of folds should raise suspicion for gastric dysplasia or early gastric cancer. Presence of GIM on endoscopy should be documented in detail with photographic evidence including the location and extent of GIM, and obtaining mapping biopsies that include at least two biopsies from the antrum (from lesser and greater curve) and from the body (lesser and greater curve). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended every 3 years in patients with extensive GIM affecting the antrum and body, incomplete GIM, and a family history of gastric cancer.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Sharma is professor of medicine and director of fellowship training, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Kansas, Kansas City.

Upper and lower gastroenterology – the state of the art

In the upper GI section of the Postgraduate course program, Ikuo Hirano, MD, educated us on the refractory patient with eosinophilic esophagitis, reinforcing the need for chronic maintenance treatment and the complementary role of dilation. Gregory Ginsberg, MD, elucidated the specific strategies needed for gastric polyps with advice on which to leave and which to resect. Sachin Wani, MD, carefully outlined the changing landscape of Barrett’s esophagus with emphasis on our move to ablate rather than observe low-grade dysplasia. In the difficult area of treating gastroparesis, Linda Nguyen, MD, acquainted us with some of the newer medications for this disorder and discussed the emerging role of endoscopic pyloromyotomy. Michael Camilleri, MD, delivered a thorough analysis on the concept of leaky gut with data-driven recommendations on testing and the lack of adequate treatment. Finally, William Chey, MD, gave perspective to diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel bacterial overgrowth, particularly with its role in irritable bowel syndrome.

In the lower GI section of the course, Sunanda Kane, MD, gave a wonderful overview the present and emerging biologics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). David Rubin, MD, shared his expertise and vast experience for best management of ulcerative colitis while Edward Loftus Jr., MD, discussed the fact and fiction of diet-based therapy in IBD. This was followed by a timely lecture by Christina Ha, MD, on the need to think well outside the GI tract in IBD, discussing infections, cancers, and vaccinations in patients with IBD. The IBD section finished with an erudite and timely lecture by Marla Dubinsky, MD, evaluating the controversy over use of biosimilars in our clinical practice. The remainder of the lower GI section started with AGA President David Lieberman, MD, analyzing recent data on the need to move the colonic cancer screening age to 45 years, particularly in African Americans. Following this was a timely talk by Xavie Llor, MD, PhD, on when to suspect and how to test for the expanding definition of Lynch syndrome. Lin Chang, MD, delivered the penultimate clinical lecture on management of irritable bowel syndrome based on her many years of clinical expertise in this area. Finally, Gail Hecht, MD, AGAF, a former AGA president, summarized the exciting world of microbiome research from the recent annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit. All in all it was considered one of the best AGA Postgraduate courses by many and we look forward to even greater improvements for 2020.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Katzka is professor of medicine and head of the Esophageal Interest Group at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He is on the advisory boards for Shire and Celgene.

In the upper GI section of the Postgraduate course program, Ikuo Hirano, MD, educated us on the refractory patient with eosinophilic esophagitis, reinforcing the need for chronic maintenance treatment and the complementary role of dilation. Gregory Ginsberg, MD, elucidated the specific strategies needed for gastric polyps with advice on which to leave and which to resect. Sachin Wani, MD, carefully outlined the changing landscape of Barrett’s esophagus with emphasis on our move to ablate rather than observe low-grade dysplasia. In the difficult area of treating gastroparesis, Linda Nguyen, MD, acquainted us with some of the newer medications for this disorder and discussed the emerging role of endoscopic pyloromyotomy. Michael Camilleri, MD, delivered a thorough analysis on the concept of leaky gut with data-driven recommendations on testing and the lack of adequate treatment. Finally, William Chey, MD, gave perspective to diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel bacterial overgrowth, particularly with its role in irritable bowel syndrome.

In the lower GI section of the course, Sunanda Kane, MD, gave a wonderful overview the present and emerging biologics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). David Rubin, MD, shared his expertise and vast experience for best management of ulcerative colitis while Edward Loftus Jr., MD, discussed the fact and fiction of diet-based therapy in IBD. This was followed by a timely lecture by Christina Ha, MD, on the need to think well outside the GI tract in IBD, discussing infections, cancers, and vaccinations in patients with IBD. The IBD section finished with an erudite and timely lecture by Marla Dubinsky, MD, evaluating the controversy over use of biosimilars in our clinical practice. The remainder of the lower GI section started with AGA President David Lieberman, MD, analyzing recent data on the need to move the colonic cancer screening age to 45 years, particularly in African Americans. Following this was a timely talk by Xavie Llor, MD, PhD, on when to suspect and how to test for the expanding definition of Lynch syndrome. Lin Chang, MD, delivered the penultimate clinical lecture on management of irritable bowel syndrome based on her many years of clinical expertise in this area. Finally, Gail Hecht, MD, AGAF, a former AGA president, summarized the exciting world of microbiome research from the recent annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit. All in all it was considered one of the best AGA Postgraduate courses by many and we look forward to even greater improvements for 2020.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Katzka is professor of medicine and head of the Esophageal Interest Group at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He is on the advisory boards for Shire and Celgene.

In the upper GI section of the Postgraduate course program, Ikuo Hirano, MD, educated us on the refractory patient with eosinophilic esophagitis, reinforcing the need for chronic maintenance treatment and the complementary role of dilation. Gregory Ginsberg, MD, elucidated the specific strategies needed for gastric polyps with advice on which to leave and which to resect. Sachin Wani, MD, carefully outlined the changing landscape of Barrett’s esophagus with emphasis on our move to ablate rather than observe low-grade dysplasia. In the difficult area of treating gastroparesis, Linda Nguyen, MD, acquainted us with some of the newer medications for this disorder and discussed the emerging role of endoscopic pyloromyotomy. Michael Camilleri, MD, delivered a thorough analysis on the concept of leaky gut with data-driven recommendations on testing and the lack of adequate treatment. Finally, William Chey, MD, gave perspective to diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel bacterial overgrowth, particularly with its role in irritable bowel syndrome.

In the lower GI section of the course, Sunanda Kane, MD, gave a wonderful overview the present and emerging biologics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). David Rubin, MD, shared his expertise and vast experience for best management of ulcerative colitis while Edward Loftus Jr., MD, discussed the fact and fiction of diet-based therapy in IBD. This was followed by a timely lecture by Christina Ha, MD, on the need to think well outside the GI tract in IBD, discussing infections, cancers, and vaccinations in patients with IBD. The IBD section finished with an erudite and timely lecture by Marla Dubinsky, MD, evaluating the controversy over use of biosimilars in our clinical practice. The remainder of the lower GI section started with AGA President David Lieberman, MD, analyzing recent data on the need to move the colonic cancer screening age to 45 years, particularly in African Americans. Following this was a timely talk by Xavie Llor, MD, PhD, on when to suspect and how to test for the expanding definition of Lynch syndrome. Lin Chang, MD, delivered the penultimate clinical lecture on management of irritable bowel syndrome based on her many years of clinical expertise in this area. Finally, Gail Hecht, MD, AGAF, a former AGA president, summarized the exciting world of microbiome research from the recent annual Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit. All in all it was considered one of the best AGA Postgraduate courses by many and we look forward to even greater improvements for 2020.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2019. Dr. Katzka is professor of medicine and head of the Esophageal Interest Group at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He is on the advisory boards for Shire and Celgene.

Large prospective trial offers reassurance for long-term PPI use

Aside from a possible increased risk of enteric infections, long-term use of the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole appears safe in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease, according to a prospective trial involving more than 17,000 participants.

In contrast with published observational studies, the present trial found no associations between long-term PPI use and previously reported risks such as pneumonia, fracture, or cerebrovascular events, according to lead author Paul Moayyedi, MB ChB, PhD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest PPI trial for any indication and the first prospective randomized trial to evaluate the many long-term safety concerns related to PPI therapy,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “It is reassuring that there was no evidence for harm for most of these events other than an excess of enteric infections.”

“Given how commonly acid suppressive medications are used, it is important to ensure that this class of drugs is safe,” the investigators wrote. They noted that patients are often alarmed by “sensational headlines” about PPI safety. “There are balancing articles that more carefully discuss the risks and benefits of taking PPI therapy but these receive less media attention,” the investigators added.

The present, prospective trial, COMPASS, involved 17,598 participants from 33 countries with stable peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease. “We use the term participants, rather than patients, as not all of those taking part in this research would have been patients throughout the trial but all participated in the randomized controlled trial,” the investigators wrote.