User login

Anticoagulant choice, PPI cotherapy impact risk of upper GI bleeding

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

Patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment had the lowest risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when taking apixaban, compared with rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and warfarin, according to a recent study.

Further, patients who received proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy had a lower overall risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Wayne A. Ray, PhD, from the department of health policy at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“These findings indicate the potential benefits of a gastrointestinal bleeding risk assessment before initiating anticoagulant treatment,” Dr. Ray and his colleagues wrote in their study, which was published in JAMA.

Dr. Ray and his colleagues performed a retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries (mean age, 76.4 years) who received 1,713,183 new episodes of oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015. They analyzed how patients reacted to apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin both with and without PPI cotherapy.

Overall, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding across 754,389 person-years without PPI therapy was 115 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 112-118) in 7,119 patients. The researchers found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban (1,278 patients; 144 per 10,000 person-years; 95% CI, 136-152) and lowest when taking apixaban (279 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; incidence rate ratio, 1,97; 95% CI, 1.73-2.25), compared with dabigatran (629 patients; 120 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.08-1.32) and warfarin (4,933 patients; 113 per 10,000 person-years; IRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35). There was a significantly lower incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding for apixaban, compared with warfarin (IRR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73) and dabigatran (IRR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.52-0.70).

There was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving PPI cotherapy (264,447 person-years; 76 per 10,000 person-years), compared with patients who received anticoagulant treatment without PPI cotherapy (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69). This reduced incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding was also seen in patients receiving PPI cotherapy and taking apixaban (IRR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.85), dabigatran (IRR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.41-0.59), rivaroxaban (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.68-0.84), and warfarin (IRR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.69).

The researchers noted that limitations in this study included potential misclassification of anticoagulant treatment, PPI cotherapy, and NSAIDs because of a reliance on filled prescription data; confounding by unmeasured factors such as aspirin exposure or Helicobacter pylori infection; and gastrointestinal bleeding being measured using a disease risk score.

This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: In patients receiving oral anticoagulant treatment, risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was highest in patients taking rivaroxaban, lowest when taking apixaban, and there was a lower overall incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding when receiving proton pump inhibitor cotherapy.

Major finding: Per 10,000 person-years, the incidence rate of gastrointestinal bleeding was 144 for rivaroxaban, 73 for apixaban, 120 for dabigatran, and 113 for warfarin; there was a gastrointestinal bleeding incidence rate ratio of 0.66 for patients using protein pump inhibitor cotherapy.

Study details: A retrospective, population-based study of 1,643,123 Medicare beneficiaries who received oral anticoagulant treatment between January 2011 and September 2015.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Ray WA et al. JAMA. 2018 Dec 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17242.

Surgical model to study reflux esophagitis after esophagojejunostomy

During a wound repair process in rats, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus was produced and increased in length following esophagojejunostomy, which may be independent of stem cell reprogramming, according to results from an anastomosed rodent study.

The investigators studied esophageal and tissue sections of 52 rats at different time points after esophagojejunostomy and samples were analyzed for length, type, and location of columnar lining. In addition, the sections were examined immunophenotypically to elucidate the molecular changes that occur during ulceration. Agoston T. Agoston, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the department of pathology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues reported the findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“This rodent columnar-lined esophagus has been proposed to develop from cellular reprogramming of progenitor cells, but studies on early columnar-lined esophagus development are lacking,” the researchers wrote.

In the model, ulceration was seen 2 weeks after surgery, which began distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis. Representative of wound healing, reepithelialization of the ulcer region took place through formation of immature glands, which were found to bud directly from jejunal crypts.

After immunophenotypic analysis, the researchers reported that “immunohistochemical characterization of neoglandular epithelium located immediately proximal to the anastomosis showed features similar to those of the native nonproliferating jejunal epithelium located immediately distal to the anastomosis.” They further reported that “the columnar-lined esophagus’s immunoprofile was similar to jejunal crypt epithelium.”

Upon further examination of the ulcer segment, Dr. Agoston and colleagues found that columnar-lined esophagus elongated from 0.15 mm (standard error of the mean, ± 0.1) to 5.22 mm (SEM, ± 0.37) at 2 and 32 weeks post esophagojejunostomy, respectively.

“There was a highly significant linear relationship between the length of the neoglandular epithelium in the distal esophagus and the number of weeks after surgery (correlation coefficient, 0.94; P less than .0001),” the investigators stated.

Locational analysis revealed epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers being expressed by spindle-shaped cells at the leading edge of the columnar-lined esophagus. In addition, neoglands were identified within esophageal ulcer beds and actively dividing squamous epithelium was seen exclusively at the proximal ulcer border.

Following the systematic analysis, the authors noted that the columnar-lined esophagus was most likely the result of jejunal cell migration into the esophagus. They suggested that if compared, jejunal cells may competitively dominate squamous cells in the context of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Furthermore, they observed that the region of ulceration following esophagojejunostomy in their model was more expansive than that reported in other comparable rodent models of reflux esophagitis.

“The reason for this difference is not clear, but we speculate that it is the result of technical aspects of our reflux-inducing surgery,” the researchers wrote. They further explained that “we intentionally fashioned a large anastomotic orifice between the esophagus and jejunum, perhaps larger than that fashioned by other investigators.” And they concluded, “we suspect that this larger orifice resulted in esophageal exposure to larger volumes of refluxate and, consequently, larger areas of ulceration.”

The authors acknowledged their results may not be fully applicable in the context of human Barrett’s esophagus, given the rodent model. However, they do believe the findings may provide a basis to help understand the wound repair process, particularly the distal edge of ulcers that border the columnar epithelium.

“Using a rat model of reflux esophagitis via surgical esophagojejunostomy, we have shown that a metaplastic, columnar-lined esophagus develops via a wound healing process, and not via genetic reprogramming of progenitor cells,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Baylor Scott and White Research Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Agoston AT et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.06.007.

Agoston et al. reported that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus develops in a wound-healing process on the distal edge of the ulcer, starting distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis in the esophagojejunal anastomosed rat model. They also concluded that the columnar-lined esophagus was caused through migration of jejunal cells into the esophagus.

These new findings bring up a couple of issues. One is that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus originates from jejunal crypt budding over the anastomosis. Some researchers may think this is not metaplasia, as there is no reprogramming of the stem cells. However, the definition of metaplasia is an endpoint such that a normal lineage is placed in an abnormal position, and it can be called metaplasia even it is from budding of jejunal crypt. This new finding is not denying metaplasia.

The second issue is whether these rodent models are really mimicking human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus or not. In humans, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus usually accompanies gastroesophageal reflux, but jejunum is not next to esophagus, and jejunal crypt budding is less likely. However, it is common to observe ulcerated lesions in the proximal front of long-segment Barrett’s esophagus in humans. In this process, the model of Agosto et al. is describing the human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus elongation.

There would be more reprogramming happening in the body of animals under the effect of microenvironment. This is a kind of adaptation, and analyzing key factors for this reprogramming would be the path to clarifying carcinogenesis in the metaplastic field and also a way to advance regenerative medicine.

Sachiyo Nomura MD, PhD, AGAF, FACS, is an investigator in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis and epithelial biology, and a gastrointestinal surgeon, at University of Tokyo Hospital, department of stomach and esophageal surgery, as well as an associate professor, department of gastrointestinal surgery, graduate school of medicine, at the university. She has no conflicts.

Agoston et al. reported that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus develops in a wound-healing process on the distal edge of the ulcer, starting distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis in the esophagojejunal anastomosed rat model. They also concluded that the columnar-lined esophagus was caused through migration of jejunal cells into the esophagus.

These new findings bring up a couple of issues. One is that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus originates from jejunal crypt budding over the anastomosis. Some researchers may think this is not metaplasia, as there is no reprogramming of the stem cells. However, the definition of metaplasia is an endpoint such that a normal lineage is placed in an abnormal position, and it can be called metaplasia even it is from budding of jejunal crypt. This new finding is not denying metaplasia.

The second issue is whether these rodent models are really mimicking human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus or not. In humans, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus usually accompanies gastroesophageal reflux, but jejunum is not next to esophagus, and jejunal crypt budding is less likely. However, it is common to observe ulcerated lesions in the proximal front of long-segment Barrett’s esophagus in humans. In this process, the model of Agosto et al. is describing the human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus elongation.

There would be more reprogramming happening in the body of animals under the effect of microenvironment. This is a kind of adaptation, and analyzing key factors for this reprogramming would be the path to clarifying carcinogenesis in the metaplastic field and also a way to advance regenerative medicine.

Sachiyo Nomura MD, PhD, AGAF, FACS, is an investigator in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis and epithelial biology, and a gastrointestinal surgeon, at University of Tokyo Hospital, department of stomach and esophageal surgery, as well as an associate professor, department of gastrointestinal surgery, graduate school of medicine, at the university. She has no conflicts.

Agoston et al. reported that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus develops in a wound-healing process on the distal edge of the ulcer, starting distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis in the esophagojejunal anastomosed rat model. They also concluded that the columnar-lined esophagus was caused through migration of jejunal cells into the esophagus.

These new findings bring up a couple of issues. One is that metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus originates from jejunal crypt budding over the anastomosis. Some researchers may think this is not metaplasia, as there is no reprogramming of the stem cells. However, the definition of metaplasia is an endpoint such that a normal lineage is placed in an abnormal position, and it can be called metaplasia even it is from budding of jejunal crypt. This new finding is not denying metaplasia.

The second issue is whether these rodent models are really mimicking human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus or not. In humans, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus usually accompanies gastroesophageal reflux, but jejunum is not next to esophagus, and jejunal crypt budding is less likely. However, it is common to observe ulcerated lesions in the proximal front of long-segment Barrett’s esophagus in humans. In this process, the model of Agosto et al. is describing the human metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus elongation.

There would be more reprogramming happening in the body of animals under the effect of microenvironment. This is a kind of adaptation, and analyzing key factors for this reprogramming would be the path to clarifying carcinogenesis in the metaplastic field and also a way to advance regenerative medicine.

Sachiyo Nomura MD, PhD, AGAF, FACS, is an investigator in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis and epithelial biology, and a gastrointestinal surgeon, at University of Tokyo Hospital, department of stomach and esophageal surgery, as well as an associate professor, department of gastrointestinal surgery, graduate school of medicine, at the university. She has no conflicts.

During a wound repair process in rats, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus was produced and increased in length following esophagojejunostomy, which may be independent of stem cell reprogramming, according to results from an anastomosed rodent study.

The investigators studied esophageal and tissue sections of 52 rats at different time points after esophagojejunostomy and samples were analyzed for length, type, and location of columnar lining. In addition, the sections were examined immunophenotypically to elucidate the molecular changes that occur during ulceration. Agoston T. Agoston, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the department of pathology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues reported the findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“This rodent columnar-lined esophagus has been proposed to develop from cellular reprogramming of progenitor cells, but studies on early columnar-lined esophagus development are lacking,” the researchers wrote.

In the model, ulceration was seen 2 weeks after surgery, which began distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis. Representative of wound healing, reepithelialization of the ulcer region took place through formation of immature glands, which were found to bud directly from jejunal crypts.

After immunophenotypic analysis, the researchers reported that “immunohistochemical characterization of neoglandular epithelium located immediately proximal to the anastomosis showed features similar to those of the native nonproliferating jejunal epithelium located immediately distal to the anastomosis.” They further reported that “the columnar-lined esophagus’s immunoprofile was similar to jejunal crypt epithelium.”

Upon further examination of the ulcer segment, Dr. Agoston and colleagues found that columnar-lined esophagus elongated from 0.15 mm (standard error of the mean, ± 0.1) to 5.22 mm (SEM, ± 0.37) at 2 and 32 weeks post esophagojejunostomy, respectively.

“There was a highly significant linear relationship between the length of the neoglandular epithelium in the distal esophagus and the number of weeks after surgery (correlation coefficient, 0.94; P less than .0001),” the investigators stated.

Locational analysis revealed epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers being expressed by spindle-shaped cells at the leading edge of the columnar-lined esophagus. In addition, neoglands were identified within esophageal ulcer beds and actively dividing squamous epithelium was seen exclusively at the proximal ulcer border.

Following the systematic analysis, the authors noted that the columnar-lined esophagus was most likely the result of jejunal cell migration into the esophagus. They suggested that if compared, jejunal cells may competitively dominate squamous cells in the context of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Furthermore, they observed that the region of ulceration following esophagojejunostomy in their model was more expansive than that reported in other comparable rodent models of reflux esophagitis.

“The reason for this difference is not clear, but we speculate that it is the result of technical aspects of our reflux-inducing surgery,” the researchers wrote. They further explained that “we intentionally fashioned a large anastomotic orifice between the esophagus and jejunum, perhaps larger than that fashioned by other investigators.” And they concluded, “we suspect that this larger orifice resulted in esophageal exposure to larger volumes of refluxate and, consequently, larger areas of ulceration.”

The authors acknowledged their results may not be fully applicable in the context of human Barrett’s esophagus, given the rodent model. However, they do believe the findings may provide a basis to help understand the wound repair process, particularly the distal edge of ulcers that border the columnar epithelium.

“Using a rat model of reflux esophagitis via surgical esophagojejunostomy, we have shown that a metaplastic, columnar-lined esophagus develops via a wound healing process, and not via genetic reprogramming of progenitor cells,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Baylor Scott and White Research Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Agoston AT et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.06.007.

During a wound repair process in rats, metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus was produced and increased in length following esophagojejunostomy, which may be independent of stem cell reprogramming, according to results from an anastomosed rodent study.

The investigators studied esophageal and tissue sections of 52 rats at different time points after esophagojejunostomy and samples were analyzed for length, type, and location of columnar lining. In addition, the sections were examined immunophenotypically to elucidate the molecular changes that occur during ulceration. Agoston T. Agoston, MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the department of pathology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues reported the findings in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“This rodent columnar-lined esophagus has been proposed to develop from cellular reprogramming of progenitor cells, but studies on early columnar-lined esophagus development are lacking,” the researchers wrote.

In the model, ulceration was seen 2 weeks after surgery, which began distally at the esophagojejunal anastomosis. Representative of wound healing, reepithelialization of the ulcer region took place through formation of immature glands, which were found to bud directly from jejunal crypts.

After immunophenotypic analysis, the researchers reported that “immunohistochemical characterization of neoglandular epithelium located immediately proximal to the anastomosis showed features similar to those of the native nonproliferating jejunal epithelium located immediately distal to the anastomosis.” They further reported that “the columnar-lined esophagus’s immunoprofile was similar to jejunal crypt epithelium.”

Upon further examination of the ulcer segment, Dr. Agoston and colleagues found that columnar-lined esophagus elongated from 0.15 mm (standard error of the mean, ± 0.1) to 5.22 mm (SEM, ± 0.37) at 2 and 32 weeks post esophagojejunostomy, respectively.

“There was a highly significant linear relationship between the length of the neoglandular epithelium in the distal esophagus and the number of weeks after surgery (correlation coefficient, 0.94; P less than .0001),” the investigators stated.

Locational analysis revealed epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers being expressed by spindle-shaped cells at the leading edge of the columnar-lined esophagus. In addition, neoglands were identified within esophageal ulcer beds and actively dividing squamous epithelium was seen exclusively at the proximal ulcer border.

Following the systematic analysis, the authors noted that the columnar-lined esophagus was most likely the result of jejunal cell migration into the esophagus. They suggested that if compared, jejunal cells may competitively dominate squamous cells in the context of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Furthermore, they observed that the region of ulceration following esophagojejunostomy in their model was more expansive than that reported in other comparable rodent models of reflux esophagitis.

“The reason for this difference is not clear, but we speculate that it is the result of technical aspects of our reflux-inducing surgery,” the researchers wrote. They further explained that “we intentionally fashioned a large anastomotic orifice between the esophagus and jejunum, perhaps larger than that fashioned by other investigators.” And they concluded, “we suspect that this larger orifice resulted in esophageal exposure to larger volumes of refluxate and, consequently, larger areas of ulceration.”

The authors acknowledged their results may not be fully applicable in the context of human Barrett’s esophagus, given the rodent model. However, they do believe the findings may provide a basis to help understand the wound repair process, particularly the distal edge of ulcers that border the columnar epithelium.

“Using a rat model of reflux esophagitis via surgical esophagojejunostomy, we have shown that a metaplastic, columnar-lined esophagus develops via a wound healing process, and not via genetic reprogramming of progenitor cells,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Baylor Scott and White Research Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Agoston AT et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.06.007.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Post esophagojejunostomy in rats, a wound repair process produces metaplastic columnar-lined esophagus likely independent of progenitor cell reprogramming.

Major finding: In an esophageal tissue section, columnar-lined esophagus length was significantly elongated from 0.15 (±0.1) mm to 5.22 (±0.37) mm at 2 and 32 weeks, respectively, following esophagojejunostomy.

Study details: Histologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 52 rats investigating the molecular characteristics of columnar-lined esophagus, specific to ulceration and wound healing, following surgery in an anastomosed rodent model.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Baylor Scott and White Research Institute. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Agoston AT et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.06.007.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Diagnosis of rumination syndrome

Additionally, promote diaphragmatic breathing to help manage the condition, advised authors of an expert review of clinical practice updates for rumination syndrome published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Patients, not unsurprisingly, typically use the word ‘vomiting’ to describe rumination events, and many patients are misdiagnosed as having refractory vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or gastroparesis,” Magnus Halland, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote in the review. “A long delay in receiving a diagnosis is common and can lead to unnecessary testing, reduced quality of life, and even invasive procedures such as surgery or feeding tubes.”

Rumination syndrome differs from vomiting, the authors noted, because the retrograde flow of ingested gastric content does not have an acidic taste and may in fact taste like food or drink recently ingested. Rumination can occur without any preceding events, after a reflux episode or by the swallowing of air that causes gastric straining but typically happens within 1 hour to 2 hours after a meal. Patients can experience weight loss, dental erosions and caries, heartburn, nausea, bloating, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, and belching, among other symptoms, in the presence of rumination syndrome, the authors said.

Dr. Halland and his colleagues provided seven best practice recommendations for rumination syndrome in their updates, which include:

- Patients who show symptoms of consistent postprandial regurgitation, often misdiagnosed with refractory gastroesophageal reflux or vomiting, should be considered for rumination syndrome.

- Patients who have dysphagia, nausea, nocturnal regurgitation, or gastric symptoms outside of meals are less likely to have rumination syndrome, but those symptoms do not exclude the condition.

- Rome IV criteria are advised to diagnose rumination syndrome after medical work-up, which includes “persistent or recurrent regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth with subsequent spitting or remastication and swallowing” not preceded by retching where patients fulfill these symptom criteria for 3 months with a minimum of 6 months of symptoms before diagnosis.

- Patients should receive first-line therapy for rumination syndrome consisting of diaphragmatic breathing with or without biofeedback.

- Patients should be referred to a speech therapist, gastroenterologist, psychologist, or other knowledgeable health practitioners to learn effective diaphragmatic breathing.

- Current limitations in the diagnosis of rumination syndrome include need for expertise and lack of standardized protocols, but “testing for rumination syndrome with postprandial high-resolution esophageal impedance manometry can be used to support the diagnosis.”

- Bacloflen (10 mg) taken three times daily is a “reasonable next step” for patients who do not respond to treatment.

The authors acknowledged that many questions, such as the pathophysiology and initiating factors of rumination syndrome, are unknown and noted future studies are needed to address epidemiology, develop validated tools for measuring symptoms, and study diaphragmatic breathing’s effect on reducing symptoms of rumination syndrome as well as the condition’s impact on quality of life.

“Indeed, the basic question of how subconsciously one can learn to regurgitate still needs to be answered,” Dr. Halland and his colleagues wrote.

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Halland M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.049.

Additionally, promote diaphragmatic breathing to help manage the condition, advised authors of an expert review of clinical practice updates for rumination syndrome published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Patients, not unsurprisingly, typically use the word ‘vomiting’ to describe rumination events, and many patients are misdiagnosed as having refractory vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or gastroparesis,” Magnus Halland, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote in the review. “A long delay in receiving a diagnosis is common and can lead to unnecessary testing, reduced quality of life, and even invasive procedures such as surgery or feeding tubes.”

Rumination syndrome differs from vomiting, the authors noted, because the retrograde flow of ingested gastric content does not have an acidic taste and may in fact taste like food or drink recently ingested. Rumination can occur without any preceding events, after a reflux episode or by the swallowing of air that causes gastric straining but typically happens within 1 hour to 2 hours after a meal. Patients can experience weight loss, dental erosions and caries, heartburn, nausea, bloating, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, and belching, among other symptoms, in the presence of rumination syndrome, the authors said.

Dr. Halland and his colleagues provided seven best practice recommendations for rumination syndrome in their updates, which include:

- Patients who show symptoms of consistent postprandial regurgitation, often misdiagnosed with refractory gastroesophageal reflux or vomiting, should be considered for rumination syndrome.

- Patients who have dysphagia, nausea, nocturnal regurgitation, or gastric symptoms outside of meals are less likely to have rumination syndrome, but those symptoms do not exclude the condition.

- Rome IV criteria are advised to diagnose rumination syndrome after medical work-up, which includes “persistent or recurrent regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth with subsequent spitting or remastication and swallowing” not preceded by retching where patients fulfill these symptom criteria for 3 months with a minimum of 6 months of symptoms before diagnosis.

- Patients should receive first-line therapy for rumination syndrome consisting of diaphragmatic breathing with or without biofeedback.

- Patients should be referred to a speech therapist, gastroenterologist, psychologist, or other knowledgeable health practitioners to learn effective diaphragmatic breathing.

- Current limitations in the diagnosis of rumination syndrome include need for expertise and lack of standardized protocols, but “testing for rumination syndrome with postprandial high-resolution esophageal impedance manometry can be used to support the diagnosis.”

- Bacloflen (10 mg) taken three times daily is a “reasonable next step” for patients who do not respond to treatment.

The authors acknowledged that many questions, such as the pathophysiology and initiating factors of rumination syndrome, are unknown and noted future studies are needed to address epidemiology, develop validated tools for measuring symptoms, and study diaphragmatic breathing’s effect on reducing symptoms of rumination syndrome as well as the condition’s impact on quality of life.

“Indeed, the basic question of how subconsciously one can learn to regurgitate still needs to be answered,” Dr. Halland and his colleagues wrote.

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Halland M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.049.

Additionally, promote diaphragmatic breathing to help manage the condition, advised authors of an expert review of clinical practice updates for rumination syndrome published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Patients, not unsurprisingly, typically use the word ‘vomiting’ to describe rumination events, and many patients are misdiagnosed as having refractory vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or gastroparesis,” Magnus Halland, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote in the review. “A long delay in receiving a diagnosis is common and can lead to unnecessary testing, reduced quality of life, and even invasive procedures such as surgery or feeding tubes.”

Rumination syndrome differs from vomiting, the authors noted, because the retrograde flow of ingested gastric content does not have an acidic taste and may in fact taste like food or drink recently ingested. Rumination can occur without any preceding events, after a reflux episode or by the swallowing of air that causes gastric straining but typically happens within 1 hour to 2 hours after a meal. Patients can experience weight loss, dental erosions and caries, heartburn, nausea, bloating, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, and belching, among other symptoms, in the presence of rumination syndrome, the authors said.

Dr. Halland and his colleagues provided seven best practice recommendations for rumination syndrome in their updates, which include:

- Patients who show symptoms of consistent postprandial regurgitation, often misdiagnosed with refractory gastroesophageal reflux or vomiting, should be considered for rumination syndrome.

- Patients who have dysphagia, nausea, nocturnal regurgitation, or gastric symptoms outside of meals are less likely to have rumination syndrome, but those symptoms do not exclude the condition.

- Rome IV criteria are advised to diagnose rumination syndrome after medical work-up, which includes “persistent or recurrent regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth with subsequent spitting or remastication and swallowing” not preceded by retching where patients fulfill these symptom criteria for 3 months with a minimum of 6 months of symptoms before diagnosis.

- Patients should receive first-line therapy for rumination syndrome consisting of diaphragmatic breathing with or without biofeedback.

- Patients should be referred to a speech therapist, gastroenterologist, psychologist, or other knowledgeable health practitioners to learn effective diaphragmatic breathing.

- Current limitations in the diagnosis of rumination syndrome include need for expertise and lack of standardized protocols, but “testing for rumination syndrome with postprandial high-resolution esophageal impedance manometry can be used to support the diagnosis.”

- Bacloflen (10 mg) taken three times daily is a “reasonable next step” for patients who do not respond to treatment.

The authors acknowledged that many questions, such as the pathophysiology and initiating factors of rumination syndrome, are unknown and noted future studies are needed to address epidemiology, develop validated tools for measuring symptoms, and study diaphragmatic breathing’s effect on reducing symptoms of rumination syndrome as well as the condition’s impact on quality of life.

“Indeed, the basic question of how subconsciously one can learn to regurgitate still needs to be answered,” Dr. Halland and his colleagues wrote.

The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Halland M et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun 11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.049.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Experts update diagnostic guidelines for eosinophilic esophagitis

The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis no longer needs to include a trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to an updated international consensus statement published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

“An initial rationale for the PPI trial was to distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease, but it is now known that these conditions have a complex relationship and are not necessarily mutually exclusive,” wrote Evan S. Dellon, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his associates. According to current evidence, “PPIs are better classified as a treatment for esophageal eosinophilia that may be due to eosinophilic esophagitis than as a diagnostic criterion,” they said.

Diagnostic guidelines for eosinophilic esophagitis were published first in 2007 and were updated in 2011. The guideline authors recommended either pH monitoring or an 8-week trial of high-dose PPI therapy to rule out inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

But subsequent publications described patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia who responded to PPIs and lacked classic GERD symptoms. Guidelines called this condition “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” and considered it a separate entity from GERD.

However, an “evolving body of research” shows that eosinophilic esophagitis can overlap with GERD, Dr. Dellon and his associates wrote. Furthermore, each of these conditions can trigger the other. Eosinophilic esophagitis can decrease esophageal compliance, leading to secondary reflux, while gastroesophageal reflux can erode the esophageal epithelium, triggering antigen exposure and eosinophilia.

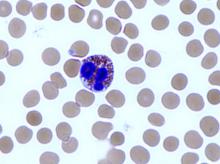

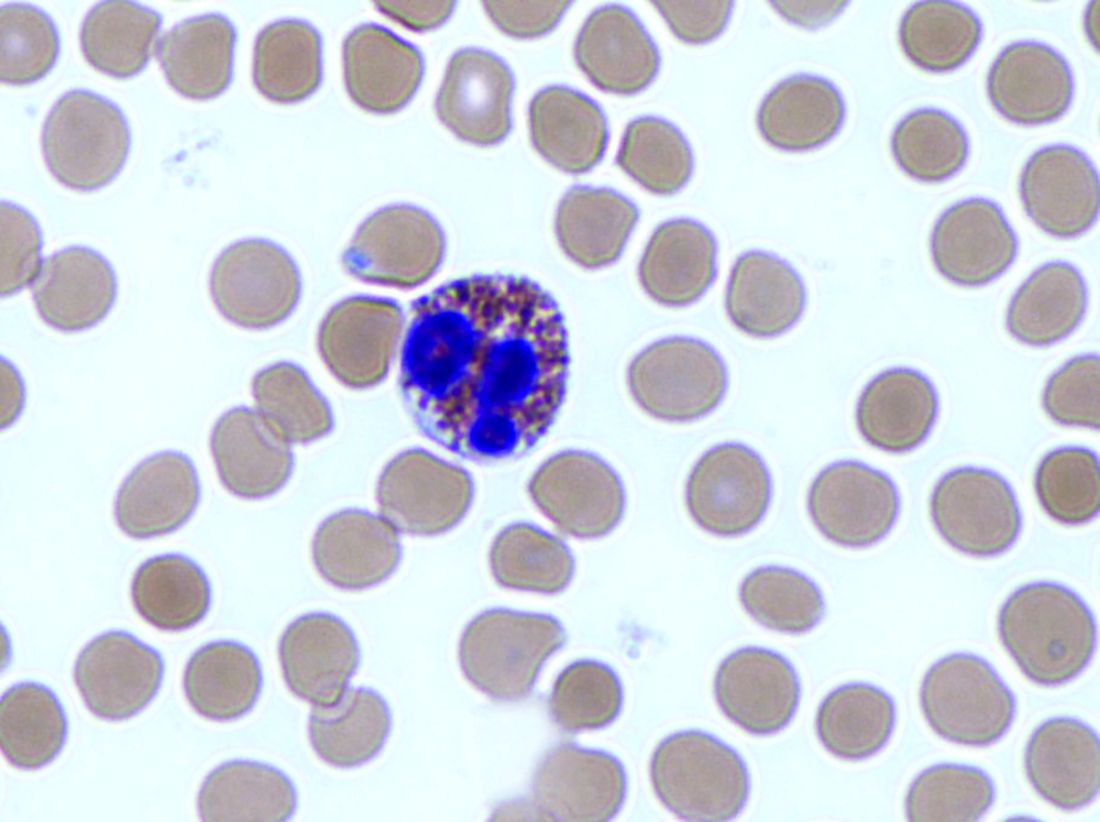

Therefore, Dr. Dellon and his associates recommended defining eosinophilic esophagitis as signs and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and an esophageal biopsy showing at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field, or approximately 60 eosinophils per millimeter, with infiltration limited to the esophagus. They stressed the importance of esophageal biopsy even if endoscopy shows normal mucosa. “As per prior guidelines, multiple biopsies from two or more esophageal levels, targeting areas of apparent inflammation, are recommended to increase the diagnostic yield,” they added. “Gastric and duodenal biopsies should be obtained as clinically indicated by symptoms, endoscopic findings in the stomach or duodenum, or high index of suspicion for a mucosal process.”

Physicians should increase their suspicion of eosinophilic esophagitis if patients have other types of atopy or endoscopic findings of “rings, furrows, exudates, edema, stricture, narrowing, and crepe-paper mucosa,” they added. In addition to GERD, they recommended looking carefully for other conditions that can trigger esophageal eosinophilia, such as pemphigus, drug hypersensitivity reactions, achalasia, and Crohn’s disease with esophageal involvement.

To create the guideline, Dr. Dellon and his associates searched PubMed for studies of all designs and sizes published from 1966 through December 2016. Teams of experts on specific topics then reviewed and discussed relevant literature. In May 2017, 43 reviewers met for 8 hours to present and discuss conclusions. There was 100% agreement to remove the PPI trial from the diagnostic criteria, the experts noted.

The authors disclosed financial support from the International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Diseases Researchers (TIGERS), The David and Denise Bunning Family, and the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. Dr. Dellon disclosed consulting relationships and receiving research funding from Adare, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire among others. The majority of his coauthors also disclosed relationships with numerous medical companies.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul 12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

Studies in the 1980s linked the presence of esophageal mucosal eosinophils with increased acid exposure on pH monitoring. For the next 2 decades, clinicians viewed eosinophils on esophageal biopsies as diagnostic for GERD such that the initial description of EoE by Attwood in 1993 distinguished EoE from GERD by the presence of esophageal eosinophilia in the absence of either reflux esophagitis or abnormal acid exposure on pH testing. Consequently, the initial diagnostic criteria for EoE in 2007 included a lack of response to PPI and/or normal pH testing to establish the diagnosis of EoE. Reflecting growing uncertainty regarding the ability of PPI therapy to differentiate acid-induced from allergic inflammatory mechanisms, an updated consensus in 2011 introduced the terminology “PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPIREE)” to describe an increasingly recognized subset of patients with suspected EoE that resolved with PPI. Now, supported by scientific evidence accumulated over the past decade, AGREE has taken a step back by removing the PPI trial from the diagnosis of EoE, thereby abandoning the PPIREE terminology. This step simplifies the diagnosis of EoE and acknowledges that a histologic response to PPI does not “rule in” GERD or “rule out” EoE. It is important to emphasize that the updated criteria still advocate careful consideration of secondary causes of esophageal eosinophilia prior to the diagnosis of EoE.

Ramifications of the updated diagnostic criteria include the opportunities for clinicians to consider use of topical corticosteroids and diet therapies, rather than mandate an up-front PPI trial, in patients with EoE. On a practical level, based on their effectiveness, safety, and ease of administration, PPIs remain positioned as a favorable initial intervention for EoE. Conceptually, however, the paradigm shift highlights the ability of research to improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and thereby impact clinical management.

Ikuo Hirano, MD, AGAF, is in the division of gastroenterology, Northwestern University, Chicago. He has received grant support from the NIH Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR, U54 AI117804), which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. He has received research funding and consulting fees from Celgene, Regeneron, Shire, and others.

Studies in the 1980s linked the presence of esophageal mucosal eosinophils with increased acid exposure on pH monitoring. For the next 2 decades, clinicians viewed eosinophils on esophageal biopsies as diagnostic for GERD such that the initial description of EoE by Attwood in 1993 distinguished EoE from GERD by the presence of esophageal eosinophilia in the absence of either reflux esophagitis or abnormal acid exposure on pH testing. Consequently, the initial diagnostic criteria for EoE in 2007 included a lack of response to PPI and/or normal pH testing to establish the diagnosis of EoE. Reflecting growing uncertainty regarding the ability of PPI therapy to differentiate acid-induced from allergic inflammatory mechanisms, an updated consensus in 2011 introduced the terminology “PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPIREE)” to describe an increasingly recognized subset of patients with suspected EoE that resolved with PPI. Now, supported by scientific evidence accumulated over the past decade, AGREE has taken a step back by removing the PPI trial from the diagnosis of EoE, thereby abandoning the PPIREE terminology. This step simplifies the diagnosis of EoE and acknowledges that a histologic response to PPI does not “rule in” GERD or “rule out” EoE. It is important to emphasize that the updated criteria still advocate careful consideration of secondary causes of esophageal eosinophilia prior to the diagnosis of EoE.

Ramifications of the updated diagnostic criteria include the opportunities for clinicians to consider use of topical corticosteroids and diet therapies, rather than mandate an up-front PPI trial, in patients with EoE. On a practical level, based on their effectiveness, safety, and ease of administration, PPIs remain positioned as a favorable initial intervention for EoE. Conceptually, however, the paradigm shift highlights the ability of research to improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and thereby impact clinical management.

Ikuo Hirano, MD, AGAF, is in the division of gastroenterology, Northwestern University, Chicago. He has received grant support from the NIH Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR, U54 AI117804), which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. He has received research funding and consulting fees from Celgene, Regeneron, Shire, and others.

Studies in the 1980s linked the presence of esophageal mucosal eosinophils with increased acid exposure on pH monitoring. For the next 2 decades, clinicians viewed eosinophils on esophageal biopsies as diagnostic for GERD such that the initial description of EoE by Attwood in 1993 distinguished EoE from GERD by the presence of esophageal eosinophilia in the absence of either reflux esophagitis or abnormal acid exposure on pH testing. Consequently, the initial diagnostic criteria for EoE in 2007 included a lack of response to PPI and/or normal pH testing to establish the diagnosis of EoE. Reflecting growing uncertainty regarding the ability of PPI therapy to differentiate acid-induced from allergic inflammatory mechanisms, an updated consensus in 2011 introduced the terminology “PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPIREE)” to describe an increasingly recognized subset of patients with suspected EoE that resolved with PPI. Now, supported by scientific evidence accumulated over the past decade, AGREE has taken a step back by removing the PPI trial from the diagnosis of EoE, thereby abandoning the PPIREE terminology. This step simplifies the diagnosis of EoE and acknowledges that a histologic response to PPI does not “rule in” GERD or “rule out” EoE. It is important to emphasize that the updated criteria still advocate careful consideration of secondary causes of esophageal eosinophilia prior to the diagnosis of EoE.

Ramifications of the updated diagnostic criteria include the opportunities for clinicians to consider use of topical corticosteroids and diet therapies, rather than mandate an up-front PPI trial, in patients with EoE. On a practical level, based on their effectiveness, safety, and ease of administration, PPIs remain positioned as a favorable initial intervention for EoE. Conceptually, however, the paradigm shift highlights the ability of research to improve our understanding of disease pathogenesis and thereby impact clinical management.

Ikuo Hirano, MD, AGAF, is in the division of gastroenterology, Northwestern University, Chicago. He has received grant support from the NIH Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR, U54 AI117804), which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. He has received research funding and consulting fees from Celgene, Regeneron, Shire, and others.

The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis no longer needs to include a trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to an updated international consensus statement published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

“An initial rationale for the PPI trial was to distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease, but it is now known that these conditions have a complex relationship and are not necessarily mutually exclusive,” wrote Evan S. Dellon, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his associates. According to current evidence, “PPIs are better classified as a treatment for esophageal eosinophilia that may be due to eosinophilic esophagitis than as a diagnostic criterion,” they said.

Diagnostic guidelines for eosinophilic esophagitis were published first in 2007 and were updated in 2011. The guideline authors recommended either pH monitoring or an 8-week trial of high-dose PPI therapy to rule out inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

But subsequent publications described patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia who responded to PPIs and lacked classic GERD symptoms. Guidelines called this condition “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” and considered it a separate entity from GERD.

However, an “evolving body of research” shows that eosinophilic esophagitis can overlap with GERD, Dr. Dellon and his associates wrote. Furthermore, each of these conditions can trigger the other. Eosinophilic esophagitis can decrease esophageal compliance, leading to secondary reflux, while gastroesophageal reflux can erode the esophageal epithelium, triggering antigen exposure and eosinophilia.

Therefore, Dr. Dellon and his associates recommended defining eosinophilic esophagitis as signs and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and an esophageal biopsy showing at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field, or approximately 60 eosinophils per millimeter, with infiltration limited to the esophagus. They stressed the importance of esophageal biopsy even if endoscopy shows normal mucosa. “As per prior guidelines, multiple biopsies from two or more esophageal levels, targeting areas of apparent inflammation, are recommended to increase the diagnostic yield,” they added. “Gastric and duodenal biopsies should be obtained as clinically indicated by symptoms, endoscopic findings in the stomach or duodenum, or high index of suspicion for a mucosal process.”

Physicians should increase their suspicion of eosinophilic esophagitis if patients have other types of atopy or endoscopic findings of “rings, furrows, exudates, edema, stricture, narrowing, and crepe-paper mucosa,” they added. In addition to GERD, they recommended looking carefully for other conditions that can trigger esophageal eosinophilia, such as pemphigus, drug hypersensitivity reactions, achalasia, and Crohn’s disease with esophageal involvement.

To create the guideline, Dr. Dellon and his associates searched PubMed for studies of all designs and sizes published from 1966 through December 2016. Teams of experts on specific topics then reviewed and discussed relevant literature. In May 2017, 43 reviewers met for 8 hours to present and discuss conclusions. There was 100% agreement to remove the PPI trial from the diagnostic criteria, the experts noted.

The authors disclosed financial support from the International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Diseases Researchers (TIGERS), The David and Denise Bunning Family, and the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. Dr. Dellon disclosed consulting relationships and receiving research funding from Adare, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire among others. The majority of his coauthors also disclosed relationships with numerous medical companies.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul 12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis no longer needs to include a trial of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to an updated international consensus statement published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

“An initial rationale for the PPI trial was to distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease, but it is now known that these conditions have a complex relationship and are not necessarily mutually exclusive,” wrote Evan S. Dellon, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his associates. According to current evidence, “PPIs are better classified as a treatment for esophageal eosinophilia that may be due to eosinophilic esophagitis than as a diagnostic criterion,” they said.

Diagnostic guidelines for eosinophilic esophagitis were published first in 2007 and were updated in 2011. The guideline authors recommended either pH monitoring or an 8-week trial of high-dose PPI therapy to rule out inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

But subsequent publications described patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia who responded to PPIs and lacked classic GERD symptoms. Guidelines called this condition “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” and considered it a separate entity from GERD.

However, an “evolving body of research” shows that eosinophilic esophagitis can overlap with GERD, Dr. Dellon and his associates wrote. Furthermore, each of these conditions can trigger the other. Eosinophilic esophagitis can decrease esophageal compliance, leading to secondary reflux, while gastroesophageal reflux can erode the esophageal epithelium, triggering antigen exposure and eosinophilia.

Therefore, Dr. Dellon and his associates recommended defining eosinophilic esophagitis as signs and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and an esophageal biopsy showing at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field, or approximately 60 eosinophils per millimeter, with infiltration limited to the esophagus. They stressed the importance of esophageal biopsy even if endoscopy shows normal mucosa. “As per prior guidelines, multiple biopsies from two or more esophageal levels, targeting areas of apparent inflammation, are recommended to increase the diagnostic yield,” they added. “Gastric and duodenal biopsies should be obtained as clinically indicated by symptoms, endoscopic findings in the stomach or duodenum, or high index of suspicion for a mucosal process.”

Physicians should increase their suspicion of eosinophilic esophagitis if patients have other types of atopy or endoscopic findings of “rings, furrows, exudates, edema, stricture, narrowing, and crepe-paper mucosa,” they added. In addition to GERD, they recommended looking carefully for other conditions that can trigger esophageal eosinophilia, such as pemphigus, drug hypersensitivity reactions, achalasia, and Crohn’s disease with esophageal involvement.

To create the guideline, Dr. Dellon and his associates searched PubMed for studies of all designs and sizes published from 1966 through December 2016. Teams of experts on specific topics then reviewed and discussed relevant literature. In May 2017, 43 reviewers met for 8 hours to present and discuss conclusions. There was 100% agreement to remove the PPI trial from the diagnostic criteria, the experts noted.

The authors disclosed financial support from the International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Diseases Researchers (TIGERS), The David and Denise Bunning Family, and the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. Dr. Dellon disclosed consulting relationships and receiving research funding from Adare, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire among others. The majority of his coauthors also disclosed relationships with numerous medical companies.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul 12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis no longer needs to include a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy.

Major finding: Eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease are not mutually exclusive.

Study details: Review by an international consensus panel of studies published between 1966 and 2016.

Disclosures: The authors disclosed financial support from the International Gastrointestinal Eosinophilic Diseases Researchers (TIGERS), The David and Denise Bunning Family, the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network. Dr. Dellon disclosed consulting relationships with Adare, Allakos, Alivio, Banner, Celgene/Receptos, Enumeral, GSK, Regeneron, and Shire. He also reported receiving research funding from Adare, Celgene/Receptos, Miraca, Meritage, Nutricia, Regeneron, and Shire and educational grants from Banner and Holoclara. The majority of his coauthors disclosed relationships with numerous medical companies.

Source: Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jul 12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

GERD patients who fail PPI often have functional heartburn or hypersensitivity

Abnormal pH results were similar in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who improved or failed to improve on a once-daily dose of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), but 75% of patients who failed treatment demonstrated either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity, based on data from 29 adults.

Previous research on PPI failure in GERD patients has focused on twice-daily doses; “the purpose of the study was to compare impedance-pH parameters between patients who failed versus those who responded to PPI once daily,” wrote Jason Abdallah, MD, of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the investigators reviewed data from adults diagnosed with GERD who were treated with PPI therapy. The 16 who reported heartburn and/or regurgitation at least twice a week for 3 months while on a standard, once-daily PPI dose were classified as the failure group. The 13 patients who reported complete symptom resolution for at least 4 weeks while on the same standard dose were classified as the success group.

Most of the patients in the PPI-failure group (75%) were found to have either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity with GERD. Impedance and pH parameters did not differ significantly between the PPI-failure and -success group, the researchers noted. Abnormal pH test results were similar between the groups, occurring in four of the patients who were successfully treated with PPI (31%) and four of the patients who failed PPI treatment (25%).

All patients completed the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) and GERD Health-Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) questionnaires, and all underwent upper endoscopy and combined 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring within 2-4 weeks of study enrollment and while following their PPI treatment plans. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the success and failure groups; the mean ages were 55 years and 47 years, respectively.

The patients in the success group averaged higher scores on the SF-36 than the failure group, but the difference was not significant. On the GERD-HRQL, treatment-failure patients reported that overall heartburn and either heartburn or bloating while lying down were the symptoms they found most annoying on a daily basis.

Among the treatment-failure patients, 10 (62%) had normal acid exposure and negative symptom-reflux association, 2 patients (13%) had normal acid exposure and positive symptom-reflux association, and 4 patients (25%) had abnormal esophageal acid exposure. Patients in the treatment failure group reported a total of 315 episodes of either heartburn or regurgitation.

Endoscopy findings were normal in most of the patients in both groups; 81% of the treatment-failure patients and 69% of the treatment-success patients had normal upper endoscopy findings. Abnormal findings in the treatment-success group included one case of erosive esophagitis, two cases of Barrett’s esophagus, three cases of nonobstructive Schatzki rings, and five cases of hiatal hernia. Abnormal findings in the treatment-failure group included two cases of Schatzki rings, one case of esophageal stricture, and three cases of hiatal hernia.

The total number of reflux events was similar between the groups; 1,279 in the treatment-failure group and 1,099 in the treatment-success group, with the number of reflux events per patient averaging 80 and 84, respectively.

“Our results support the hypothesis that PPI failure is primarily driven by esophageal hypersensitivity,” the researchers noted. The similarity in impedance and reflux “implies that the shift to nonacidic reflux is a general PPI phenomenon, as opposed to being unique to PPI-failure patients,” they said.

The study was limited by the small patient population, but the results provide some insight into refractory GERD and suggest that patients who fail to respond to once-daily PPI might benefit from a neuromodulator, as well as psychological interventions including cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and biofeedback, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Abdullah had no financial conflicts to disclose; a coauthor disclosed relationships with companies including Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Mederi Therapeutics, and Ethicon Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Abdallah J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.018.

Abnormal pH results were similar in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who improved or failed to improve on a once-daily dose of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), but 75% of patients who failed treatment demonstrated either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity, based on data from 29 adults.

Previous research on PPI failure in GERD patients has focused on twice-daily doses; “the purpose of the study was to compare impedance-pH parameters between patients who failed versus those who responded to PPI once daily,” wrote Jason Abdallah, MD, of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the investigators reviewed data from adults diagnosed with GERD who were treated with PPI therapy. The 16 who reported heartburn and/or regurgitation at least twice a week for 3 months while on a standard, once-daily PPI dose were classified as the failure group. The 13 patients who reported complete symptom resolution for at least 4 weeks while on the same standard dose were classified as the success group.

Most of the patients in the PPI-failure group (75%) were found to have either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity with GERD. Impedance and pH parameters did not differ significantly between the PPI-failure and -success group, the researchers noted. Abnormal pH test results were similar between the groups, occurring in four of the patients who were successfully treated with PPI (31%) and four of the patients who failed PPI treatment (25%).

All patients completed the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) and GERD Health-Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) questionnaires, and all underwent upper endoscopy and combined 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring within 2-4 weeks of study enrollment and while following their PPI treatment plans. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the success and failure groups; the mean ages were 55 years and 47 years, respectively.

The patients in the success group averaged higher scores on the SF-36 than the failure group, but the difference was not significant. On the GERD-HRQL, treatment-failure patients reported that overall heartburn and either heartburn or bloating while lying down were the symptoms they found most annoying on a daily basis.

Among the treatment-failure patients, 10 (62%) had normal acid exposure and negative symptom-reflux association, 2 patients (13%) had normal acid exposure and positive symptom-reflux association, and 4 patients (25%) had abnormal esophageal acid exposure. Patients in the treatment failure group reported a total of 315 episodes of either heartburn or regurgitation.

Endoscopy findings were normal in most of the patients in both groups; 81% of the treatment-failure patients and 69% of the treatment-success patients had normal upper endoscopy findings. Abnormal findings in the treatment-success group included one case of erosive esophagitis, two cases of Barrett’s esophagus, three cases of nonobstructive Schatzki rings, and five cases of hiatal hernia. Abnormal findings in the treatment-failure group included two cases of Schatzki rings, one case of esophageal stricture, and three cases of hiatal hernia.

The total number of reflux events was similar between the groups; 1,279 in the treatment-failure group and 1,099 in the treatment-success group, with the number of reflux events per patient averaging 80 and 84, respectively.

“Our results support the hypothesis that PPI failure is primarily driven by esophageal hypersensitivity,” the researchers noted. The similarity in impedance and reflux “implies that the shift to nonacidic reflux is a general PPI phenomenon, as opposed to being unique to PPI-failure patients,” they said.

The study was limited by the small patient population, but the results provide some insight into refractory GERD and suggest that patients who fail to respond to once-daily PPI might benefit from a neuromodulator, as well as psychological interventions including cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and biofeedback, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Abdullah had no financial conflicts to disclose; a coauthor disclosed relationships with companies including Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Mederi Therapeutics, and Ethicon Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Abdallah J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.018.

Abnormal pH results were similar in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who improved or failed to improve on a once-daily dose of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), but 75% of patients who failed treatment demonstrated either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity, based on data from 29 adults.

Previous research on PPI failure in GERD patients has focused on twice-daily doses; “the purpose of the study was to compare impedance-pH parameters between patients who failed versus those who responded to PPI once daily,” wrote Jason Abdallah, MD, of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and colleagues.

In a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the investigators reviewed data from adults diagnosed with GERD who were treated with PPI therapy. The 16 who reported heartburn and/or regurgitation at least twice a week for 3 months while on a standard, once-daily PPI dose were classified as the failure group. The 13 patients who reported complete symptom resolution for at least 4 weeks while on the same standard dose were classified as the success group.

Most of the patients in the PPI-failure group (75%) were found to have either functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity with GERD. Impedance and pH parameters did not differ significantly between the PPI-failure and -success group, the researchers noted. Abnormal pH test results were similar between the groups, occurring in four of the patients who were successfully treated with PPI (31%) and four of the patients who failed PPI treatment (25%).

All patients completed the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) and GERD Health-Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) questionnaires, and all underwent upper endoscopy and combined 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring within 2-4 weeks of study enrollment and while following their PPI treatment plans. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the success and failure groups; the mean ages were 55 years and 47 years, respectively.

The patients in the success group averaged higher scores on the SF-36 than the failure group, but the difference was not significant. On the GERD-HRQL, treatment-failure patients reported that overall heartburn and either heartburn or bloating while lying down were the symptoms they found most annoying on a daily basis.

Among the treatment-failure patients, 10 (62%) had normal acid exposure and negative symptom-reflux association, 2 patients (13%) had normal acid exposure and positive symptom-reflux association, and 4 patients (25%) had abnormal esophageal acid exposure. Patients in the treatment failure group reported a total of 315 episodes of either heartburn or regurgitation.

Endoscopy findings were normal in most of the patients in both groups; 81% of the treatment-failure patients and 69% of the treatment-success patients had normal upper endoscopy findings. Abnormal findings in the treatment-success group included one case of erosive esophagitis, two cases of Barrett’s esophagus, three cases of nonobstructive Schatzki rings, and five cases of hiatal hernia. Abnormal findings in the treatment-failure group included two cases of Schatzki rings, one case of esophageal stricture, and three cases of hiatal hernia.

The total number of reflux events was similar between the groups; 1,279 in the treatment-failure group and 1,099 in the treatment-success group, with the number of reflux events per patient averaging 80 and 84, respectively.

“Our results support the hypothesis that PPI failure is primarily driven by esophageal hypersensitivity,” the researchers noted. The similarity in impedance and reflux “implies that the shift to nonacidic reflux is a general PPI phenomenon, as opposed to being unique to PPI-failure patients,” they said.

The study was limited by the small patient population, but the results provide some insight into refractory GERD and suggest that patients who fail to respond to once-daily PPI might benefit from a neuromodulator, as well as psychological interventions including cognitive-behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, relaxation techniques, mindfulness, and biofeedback, the researchers concluded.

Dr. Abdullah had no financial conflicts to disclose; a coauthor disclosed relationships with companies including Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Mederi Therapeutics, and Ethicon Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Abdallah J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.018.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: PPI failure in GERD patients appears to be driven by esophageal hypersensitivity, not significantly associated with reflux.

Major finding: Most (75%) of the patients who failed PPI treatment had heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity with GERD.

Study details: The data come from a prospective cohort study of 29 adults with GERD.

Disclosures: Dr. Abdullah had no financial conflicts to disclose; a coauthor disclosed relationships with companies including Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Mederi Therapeutics, and Ethicon Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Abdullah J et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.018.

POEM effective for more than achalasia

.

The procedure was clinically successful and relieved chest pain in most patients, reported Mouen A. Khashab, MD, director of therapeutic endoscopy at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

POEM was introduced in 2008 as a less invasive alternative to laparoscopic Heller myotomy. During the procedure, submucosal tunneling is performed through the lower esophageal sphincter to the gastric cardia, thereby weakening the lower esophageal sphincter to allow passage of food.

POEM is clinically successful in 80%-90% of patients with achalasia. Although the procedure is regarded as safe and effective for achalasia, it has not been thoroughly researched for treatment of other esophageal motility disorders, including junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO), jackhammer esophagus (JE), or esophagogastric distal esophageal spasm (DES). EGJOO is similar to achalasia, but with peristalsis and a mean integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) greater than 15 mm Hg. Both JE and DES are spastic esophageal disorders. Patients with JE exhibit extreme esophageal hypercontractility, whereas patients with DES have a normal mean IRP and at least 20% premature contractions.

“The role POEM plays in management of these disorders is not clear, mainly due to scarcity of studies on this topic,” the authors wrote in Endoscopy International Open. “A previous multicenter study investigated the role of POEM in 73 patients with spastic esophageal disorders. However, the vast majority of patients (n = 54) in that study had type III (spastic) achalasia.” Since therapies such as botulinum toxin injections and calcium channel blockers are ineffective for many patients with nonachalasia esophageal motility disorders, “POEM is potentially an ideal treatment.”

The international, multicenter study involved 11 treatment centers and 50 patients. Patients with JE (n = 18), EGJOO (n = 15), and DES (n = 17) were included, each diagnosed according to the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders. Patients with type III achalasia were excluded.

Outcomes included technical success (completion of myotomy) and clinical success (Eckardt score at least 3 and symptom improvement). Prior to the procedure, the mean Eckardt score was 6.9 and chest pain was reported by almost three-quarters of the patients (72%).

Technical success was achieved in all patients. Myotomy thickness varied between cases; approximately half had a selective inner circular myotomy (48%), slightly less had a full-thickness myotomy (44%), and several were undefined (8%). Mean esophageal myotomy length was 12.5 cm and mean gastric myotomy length was 2.5 cm. Mean procedure time was approximately 90 minutes. Median duration of hospital stay was 2 days.

Nine adverse events (AEs) occurred in 8 patients, including submucosal hematoma, aspiration pneumonia, inadvertent mucosotomy, postprocedure pain, esophageal leak, bleed, and symptomatic capno-thorax/peritoneum.

“Although AEs occurred in 18% of patients,” the authors noted, “55.6% were rated as mild and 44.4% as moderate with no severe events. Most AEs can be managed intraprocedurally.”