User login

Split-dose oxycodone protocol reduces opioid use after cesarean

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

A retrospective study reviewed medical records of 1,050 women undergoing cesarean delivery, 508 of whom were treated after a change in protocol for postdelivery oxycodone orders. Instead of a 5-mg oral dose given for a verbal pain score of 4/10 or below and 10 mg for a pain score of 5-10/10, patients were given 2.5-mg or 5-mg dose respectively, with a nurse check after 1 hour to see if more of the same dosage was needed.

The split-dose approach was associated with a 56% reduction in median opioid consumption in the first 48 hours after cesarean delivery; 10 mg before the change in practice to 4.4 mg after it. There was also a 6.9-percentage-point decrease in the number of patients needing any postoperative opioids.

While the study did show a slight increase in average verbal pain scores in the first 58 hours after surgery – from a mean of 1.8 before the split-dose protocol was introduced to 2 after it was introduced – there was no increase in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin, and no difference in peak verbal pain scores.

“Our goal with the introduction of this new order set was to use a patient-centered, response-feedback approach to postcesarean delivery analgesia in the form of split doses of oxycodone rather than the traditional standard dose model,” wrote Jalal A. Nanji, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and coauthors. “Involving patients in the decision for how much postcesarean delivery analgesia they will receive has been found to reduce opioid use and improve maternal satisfaction.”

The number of patients reporting postoperative nausea or vomiting was halved in those treated with the split-dose regimen, with no difference in mean overall patient satisfaction score.

Dr. Nanji and associates wrote that women viewed avoiding nausea or vomiting after a cesarean as a high priority, and targeting the root cause – excessive opioid use – was preferable to treating nausea and vomiting with antiemetics.

They also noted that input from nursing staff was vital in developing the new split-order set, not only because it directly affected nursing work flow but also to optimize the process.

“With the opioid epidemic on the rise and the increase in efforts by physicians to decrease outpatient opioid prescriptions, this study is extremely relevant and timely,” commented Marissa Platner, MD, an assistant professor in maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

“Although this study is retrospective and, therefore, there are inherent biases and an inability to control all contributing factors, it clearly demonstrates that, overall, there seem to be improved outcomes with split-dose protocol of opioid administration during the postoperative period in terms of overall patient satisfaction, opioid consumption, and postoperative nausea and vomiting. The patient-centered nature and response-feedback design of this study also contributes to its strength and improves its generalizability. In order to encourage others to considering adapting protocol in other institutions, it should be evaluated via a randomized controlled trial," Dr. Platner said in an interview.*

"The premise and execution of this study were novel and interesting," commented Katrina Mark, MD, associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology & reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "The authors found that by decreasing the standard doses of oxycodone ordered after a cesarean section and asking women if they desired better pain control, rather than reacting only to a pain score, patients’ overall postoperative usage of opiates also decreased. In decreasing the amount of opiates used, the authors also observed a decrease some of the side effects associated with opiate use, which is promising.

"This study, among other recent studies, highlights the fact that postoperative prescribing standards are not evidence-based and may lead to overprescribing of opiates. Improving prescribing practices is a noble and important goal. In this study, a change in clinical practice among both nurses and prescribers is likely what caused the greatest change. The use of a protocol which prescribed oxycodone based on asking if a woman desired improved pain control, rather than prescribing only based on her pain score response, makes a lot of intuitive sense. Decreasing opioid consumption requires education of healthcare providers and patients, and protocols like this one will help to encourage that conversation," she noted in an interview.

"Before the findings of this study can be widely adopted, however, there are two major points that will need to be addressed," Dr. Mark emphasized. "The first is patient satisfaction. The peak pain scores were not different between the groups, but the mean pain scores were. The authors deemed this clinically insignificant, which it may be. However, without the patients’ perspective on this new protocol, it is difficult to tell if the opioid usage decreased because women actually needed less opiates or if it decreased because the system discouraged opioid use and made it more challenging for them to obtain the medicine they needed to achieve adequate pain control. The desire to decrease opioid prescribing is warranted, and likely completely appropriate, but there is certainly a role for opioids in pain management. We should not be so motivated to decrease use that we cause unnecessary suffering. The second point that will need to be addressed is the effect on nursing practice. There was no standardized evaluation of the impact that this protocol had on the nursing staff, and it is unclear if this protocol would require greater resources than may be readily available at all hospitals."**

The study was supported by the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. One author declared travel funding from a university. No other conflicts of interest were declared. Dr. Platner and Dr. Mark also had no relevant financial disclosures.*

SOURCE: Nanji J et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003305.

*This article was updated on 7/15/2019.

**It was updated again on 7/17/2019.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Consider cutaneous endometriosis in women with umbilical lesions

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

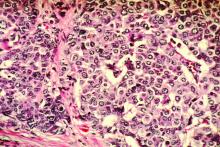

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

according to Liza Raffi of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates.

The report, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, detailed a case of a woman aged 41 years who presented with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus and flares of pain during menstrual periods. Her past history indicated a missed miscarriage (removed by dilation and curettage) and laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

At presentation, the woman reported undergoing fertility treatments including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

Because of the patient’s history of salpingectomy and painful menstrual periods, her physicians suspected cutaneous endometriosis. An ultrasound was performed to rule out fistula, and then a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed. The biopsy showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, which was consistent with cutaneous endometriosis, likely transplanted during the laparoscopic port site entry during salpingectomy.

The patient chose to undergo surgery for excision of the nodule, declining hormonal therapy because she was undergoing fertility treatment.

“The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer,” the investigators wrote. “Ultimately, patients should be referred to obstetrics & gynecology if they describe classic symptoms including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.”

Ms. Raffi and associates reported they had no conflicts of interest. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Raffi L et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.025.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

The FDA has revised its guidance on fish consumption

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

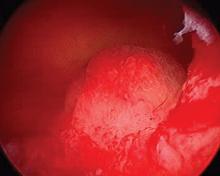

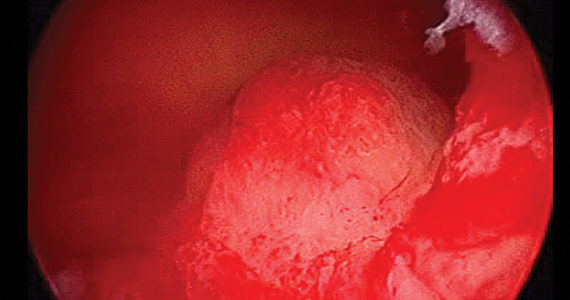

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

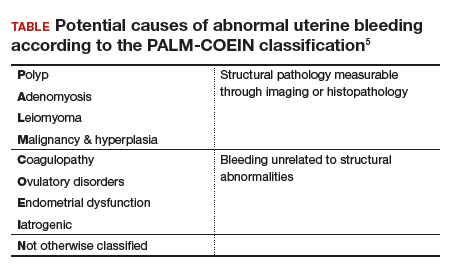

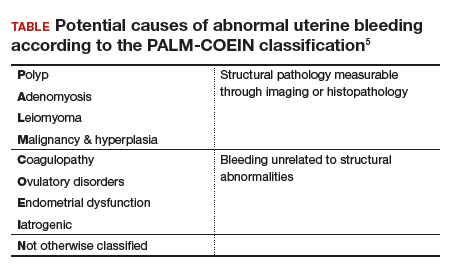

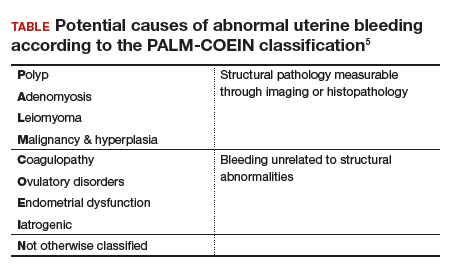

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.

If a patient wants a baby, she should find a gynecologic surgeon who does minimally invasive laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgery, because she is more likely to have a take-home baby with a surgical approach than with embolization. In my experience, there is always going to be a patient who wants to keep her uterus at age 49 and who has every comorbidity. I might offer her the embolization just knowing what the odds of pregnancy are.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda but I take a more liberal approach. Sometimes we do a myomectomy because we are trying to enhance fertility, while other times we do a myomectomy to address fibroid-related symptoms. These patients are having specific symptoms, and we want to leave the embolization option open.

If I have a patient who is 39 and becoming pregnant is not necessarily her goal, but she does not want to have a hysterectomy and if she got pregnant it would be okay, I am going to treat her a little different with respect to fibroid embolization than I would treat someone who is actively trying to have a baby. This goes back to what you were saying, let’s treat the patient, not just the fibroid.

Dr. Bradley: That is so important and sentinel. If she really does not want a hysterectomy but does not want a baby, I will ask, “Would you go through in vitro fertilization? Would you take clomiphene?” If she answers no, then I feel more comfortable, like you, with referring the patient for uterine fibroid embolization. The point is to get the patient with the right team to get the best outcomes.

Surgical approaches, intraoperative agents, and suture technique

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, tell us about your surgical approaches to fibroids.

Dr. Anderson: At my institution we do have a fellowship in minimally invasive surgery, but I still do a lot of open myomectomies. I have a few guidelines to determine whether I am going to proceed laparoscopically, do a little minilaparotomy incision, or if a gigantic uterus is going to require a big incision. My mantra to my fellows has always been, “minimally invasive is the impact on the patient, not the size of the incision.”

Sometimes, prolonged anesthesia and Trendelenburg create more morbidity than a minilaparotomy. If a patient has 4 or 5 fibroids and most of them are intramural and I cannot see them but I want to be able to feel them, and to get a really good closure of the myometrium, I might choose to do a minilaparotomy. But if it is a case of a solitary fibroid, I would be more inclined to operate laparoscopically.

Continue to: Dr. Bradley...

Dr. Bradley: Our protocol is similar. We use MRI liberally. If patients have 4 or more fibroids and they are larger than 8 cm, most will have open surgery. I do not do robotic or laparoscopic procedures, so my referral source is for the larger myomas. We do not put retractors in; we can make incisions. Even if we do a huge Maylard incision, it is cosmetically wonderful. We use a loading dose of IV tranexamic acid with tranexamic acid throughout the surgery, and misoprostol intravaginally prior to surgery, to control uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, is there a role for agents such as vasopressin, and what about routes of administration?

Dr. Anderson: When I do a laparoscopic or open procedure, I inject vasopressin (dilute 20 U in 100 mL of saline) into the pseudocapsule around the fibroid. I also administer rectal misoprostol (400 µg) just before the patient prep is done, which is amazing in reducing blood loss. There is also a role for a GnRH agonist, not necessarily to reduce the size of the uterus but to reduce blood flow in the pelvis and blood loss. Many different techniques are available. I do not use tourniquets, however. If bleeding does occur, I want to see it so I can fix it—not after I have sewn up the uterus and taken off a tourniquet.

Dr. Bradley: Do you use Floseal hemostatic matrix or any other agent to control bleeding?

Dr. Anderson: I do, for local hemostasis.

Dr. Bradley: Some surgeons will use barbed suture.

Dr. Anderson: I do like barbed sutures. In teaching residents to do myomectomy, it is very beneficial. But I am still a big fan of the good old figure-of-8 stitch because it is compressive and you get a good apposition of the tissue, good hemostasis, and strong closure.

Dr. Sanfilippo: We hope that this conversation will change your management of uterine fibroids. I thank Dr. Bradley and Dr. Anderson for a lively and very informative discussion.

Watch the video: Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

- Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK. Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:95-114.

- Divakars H. Asymptomatic uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:643-654.

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2013;22:807-816.

- Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective cohort study of uterine fibroids and miscarriage risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1140-1148.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, for the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204-2208.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76.

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.