User login

Colchicine May Benefit Patients With Diabetes and Recent MI

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A daily low dose of colchicine significantly reduces ischemic cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and a recent myocardial infarction (MI).

METHODOLOGY:

- After an MI, patients with vs without T2D have a higher risk for another cardiovascular event.

- The Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT), a randomized, double-blinded trial, found a lower risk for ischemic cardiovascular events with 0.5 mg colchicine taken daily vs placebo, initiated within 30 days of an MI.

- Researchers conducted a prespecified subgroup analysis of 959 adult patients with T2D (mean age, 62.4 years; 22.2% women) in COLCOT (462 patients in colchicine and 497 patients in placebo groups).

- The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring coronary revascularization within a median 23 months.

- The patients were taking a variety of appropriate medications, including aspirin and another antiplatelet agent and a statin (98%-99%) and metformin (75%-76%).

TAKEAWAY:

- The risk for the primary endpoint was reduced by 35% in patients with T2D who received colchicine than in those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65; P = .03).

- The primary endpoint event rate per 100 patient-months was significantly lower in the colchicine group than in the placebo group (rate ratio, 0.53; P = .01).

- The frequencies of adverse events were similar in both the treatment and placebo groups (14.6% and 12.8%, respectively; P = .41), with gastrointestinal adverse events being the most common.

- In COLCOT, patients with T2D had a 1.86-fold higher risk for a primary endpoint cardiovascular event, but there was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between those with and without T2D on colchicine.

IN PRACTICE:

“Patients with both T2D and a recent MI derive a large benefit from inflammation-reducing therapy with colchicine,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This study, led by François Roubille, University Hospital of Montpellier, France, was published online on January 5, 2024, in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients were not stratified at inclusion for the presence of diabetes. Also, the study did not evaluate the role of glycated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as the effects of different glucose-lowering medications or possible hypoglycemic episodes.

DISCLOSURES:

The COLCOT study was funded by the Government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Coauthors Jean-Claude Tardif and Wolfgang Koenig declared receiving research grants, honoraria, advisory board fees, and lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies, as well as having other ties with various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Eli Lilly Offers Obesity Drug Directly to Consumers

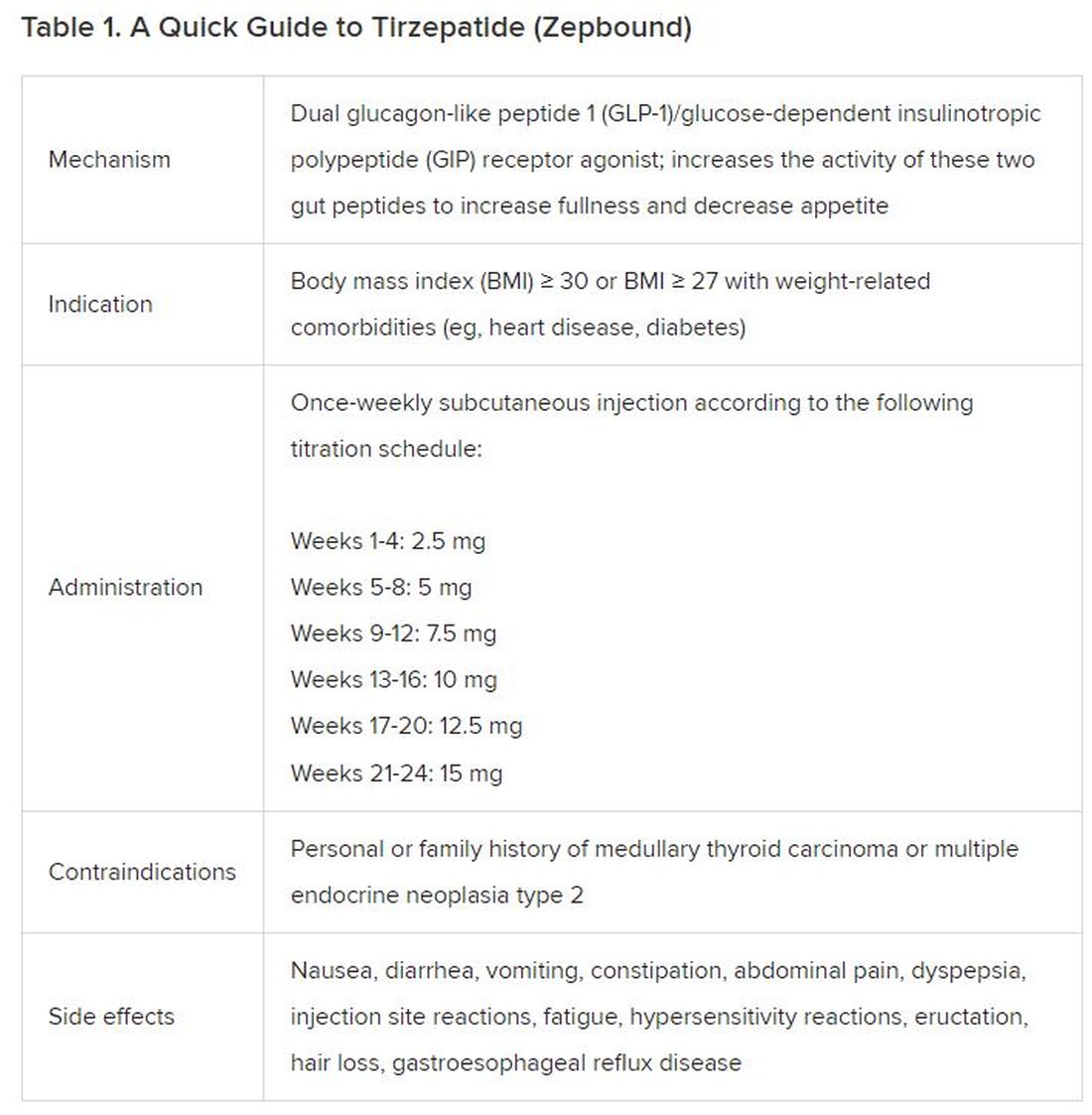

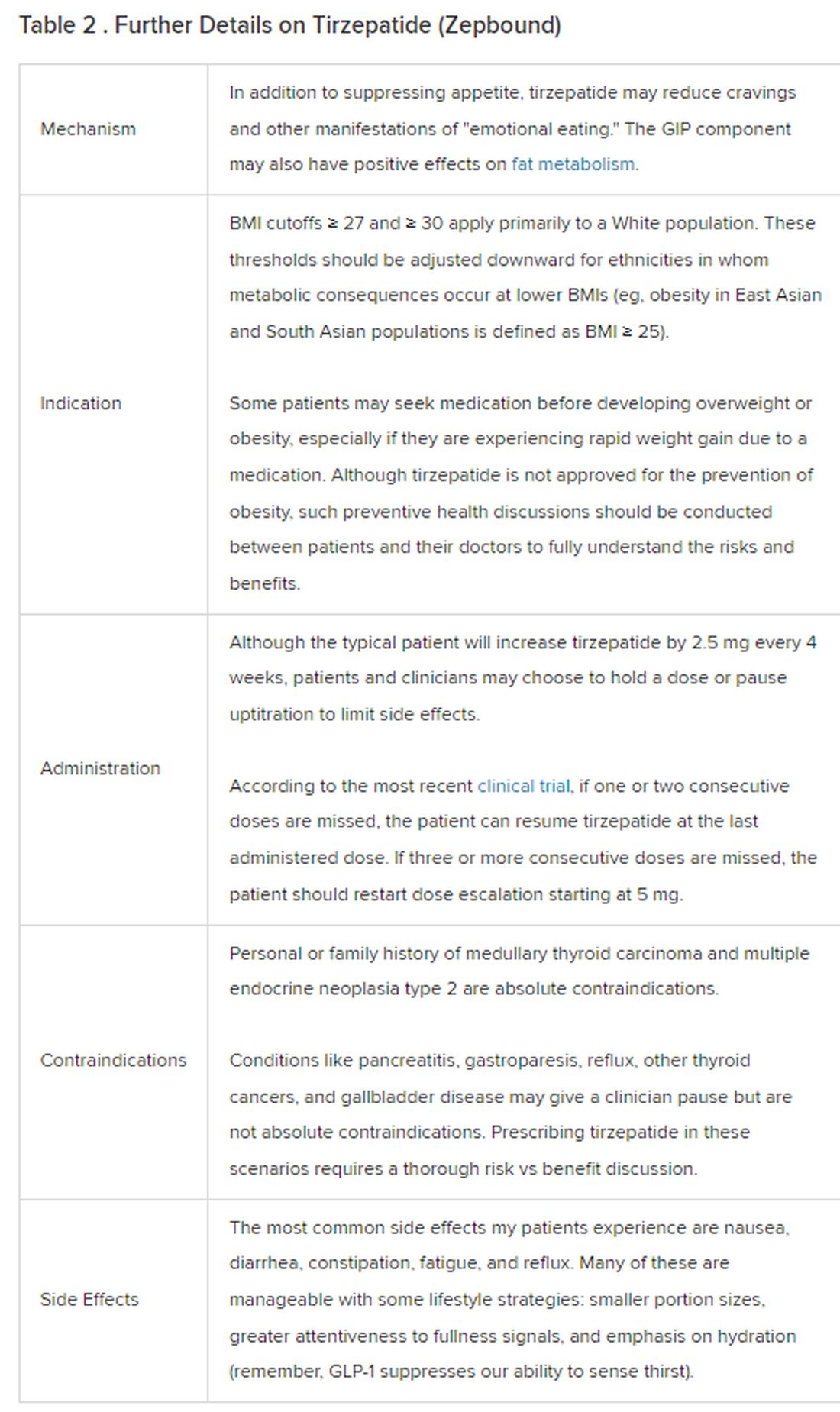

Eli Lilly, maker of the anti-obesity drug Zepbound, announced this week the launch of LillyDirect, a direct-to-patient portal, allowing some patients to obtain its drug for as little as $25 a month.

The move is seen as a major shift in the way these popular medications can reach patients.

For many of the 42 million Americans with obesity, weight loss medications such as Wegovy, Saxenda, and the brand-new Zepbound can be a godsend, helping them lose the excess pounds they’ve struggled with for decades or a lifetime.

But getting these medications has been a struggle for many who are eligible. Shortages of the drugs have been one barrier, and costs of up to $1,300 monthly — the price tag without insurance coverage — are another hurdle.

But 2024 may be a much brighter year, thanks to Lilly’s new portal as well as other developments:

Insurance coverage on private health plans, while still spotty, may be improving. Federal legislators are fighting a 2003 law that forbids Medicare from paying for the medications when prescribed for obesity.

New research found that semaglutide (Wegovy) can reduce the risk of recurrent strokes and heart attacks as well as deaths from cardiovascular events in those with obesity and preexisting cardiovascular disease (or diseases of the heart and blood vessels), a finding experts said should get the attention of health insurers.

The medications, also referred to as GLP-1 agonists, work by activating the receptors of hormones (called glucagon-like peptide 1 and others) that are naturally released after eating. That, in turn, makes you feel more full, leading to weight loss of up to 22% for some. The medications are approved for those with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or a BMI of 27 with at least one other weight-related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol. The medicines, injected weekly or more often, are prescribed along with advice about a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

LillyDirect

Patients can access the obesity medicines through the telehealth platform FORM. Patients reach independent telehealth providers, according to Lilly, who can complement a patient’s current doctor or be an alternative to in-patient care in some cases.

Eli Lilly officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Some obesity experts welcomed the new service. “Any program that improves availability and affordability of these ground-breaking medications is welcome news for our long-suffering patients,” said Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, a long-time obesity researcher.

“It’s a great move for Lilly to do,” agreed Caroline Apovian, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who is also a veteran obesity specialist. “It is trying to help the accessibility issue and do it responsibly.”

“The bottom line is, there is an overwhelming amount of consumer need and desire for these medications and not enough channels [to provide them],” said Zeev Neuwirth, MD, a former executive at Atrium Health who writes about health care trends. “Eli Lilly is responding to a market need that is out there and quite honestly continuing to grow.”

There are still concerns and questions, Dr. Neuwirth said, “especially since this is to my knowledge the first of its kind in terms of a pharmaceutical manufacturer directly dispensing medication in this nontraditional way.”

He called for transparency between telehealth providers and the pharmaceutical company to rule out any conflicts of interest.

The American College of Physicians, an organization of internal medicine doctors and others, issued a statement expressing concern. Omar T. Atiq, MD, group’s president, said his organization is “concerned by the development of websites that enable patients to order prescription medications directly from the drugmakers. While information on in-person care is available, this direct-to-consumer approach is primarily oriented around the use of telehealth services to prescribe a drug maker’s products.”

The group urged that an established patient-doctor relationship be present, or that care should happen in consultation with a doctor who does have an established relationship (the latter an option offered by Lilly). “These direct-to-consumer services have the potential to leave patients confused and misinformed about medications.”

Heart Attack, Stroke Reduction Benefits

Previous research has found that the GLP-1 medicines such as Ozempic (semaglutide), which the FDA approved to treat diabetes, also reduce the risk of cardiovascular issues such as strokes and heart attacks. Now, new research finds that semaglutide at the Wegovy dose (usually slightly higher than the Ozempic dose for diabetes) also has those benefits in those who don›t have a diabetes diagnosis but do have obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In a clinical trial sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the maker of Wegovy, half of more than 17,000 people with obesity were given semaglutide (Wegovy); the other half got a placebo. Compared to those on the placebo, those who took the Wegovy had a 20% reduction in strokes, heart attacks, and deaths from cardiovascular causes over a 33-month period.

The study results are a “big deal,” Dr. Aronne said. The results make it clear that those with obesity but not diabetes will get the cardiovascular benefits from the treatment as well. While more analysis is necessary, he said the important point is that the study showed that reducing body weight is linked to improvement in critical health outcomes.

As the research evolves, he said, it’s going to be difficult for insurers to deny medications in the face of those findings, which promise reductions in long-term health care costs.

Insurance Coverage

In November, the American Medical Association voted to adopt a policy to urge insurance coverage for evidence-based treatment for obesity, including the new obesity medications.

“No single organization is going to be able to convince insurers and employers to cover this,” Dr. Aronne said. “But I think a prominent organization like the AMA adding their voice to the rising chorus is going to help.”

Coverage of GLP-1 medications could nearly double in 2024, according to a survey of 500 human resources decision-makers released in October by Accolade, a personalized health care advocacy and delivery company. While 25% of respondents said they currently offered coverage when the survey was done in August and September, 43% said they intend to offer coverage in 2024.

In an email, David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a health care industry association, said: “Every American deserves affordable coverage and high-quality care, and that includes coverage and care for evidence-based obesity treatments and therapies.”

He said “clinical leaders and other experts at health insurance providers routinely review the evidence for all types of treatments, including treatments for obesity, and offer multiple options to patients — ranging from lifestyle changes and nutrition counseling, to surgical interventions, to prescription drugs.”

Mr. Allen said the evidence that obesity drugs help with weight loss “is still evolving.”

“And some patients are experiencing bad effects related to these drugs such as vomiting and nausea, for example, and the likelihood of gaining the weight back when discontinuing the drugs,” he said.

Others are fighting for Medicare coverage, while some experts contend the costs of that coverage would be overwhelming. A bipartisan bill, the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act of 2023, would allow coverage under Medicare›s prescription drug benefit for drugs used for the treatment of obesity or for weigh loss management for people who are overweight. Some say it›s an uphill climb, citing a Vanderbilt University analysis that found giving just 10% of Medicare-eligible patients the drugs would cost $13.6 billion to more than $26 billion.

However, a white paper from the University of Southern California concluded that the value to society of covering the drugs for Medicare recipients would equal nearly $1 trillion over 10 years, citing savings in hospitalizations and other health care costs.

Comprehensive insurance coverage is needed, Dr. Apovian said. Private insurance plans, Medicare, and Medicaid must all realize the importance of covering what has been now shown to be life-saving drugs, she said.

Broader coverage might also reduce the number of patients getting obesity drugs from unreliable sources, in an effort to save money, and having adverse effects. The FDA warned against counterfeit semaglutide in December.

Long-Term Picture

Research suggests the obesity medications must be taken continuously, at least for most people, to maintain the weight loss. In a study of patients on Zepbound, Dr. Aronne and colleagues found that withdrawing the medication led people to regain weight, while continuing it led to maintaining and even increasing the initial weight loss. While some may be able to use the medications only from time to time, “the majority will have to take these on a chronic basis,” Dr. Aronne said.

Obesity, like high blood pressure and other chronic conditions, needs continuous treatment, Dr. Apovian said. No one would suggest withdrawing blood pressure medications that stabilize blood pressure; the same should be true for the obesity drugs, she said.

Dr. Apovian consults for FORM, the telehealth platform Lilly uses for LillyDirect, and consults for Novo Nordisk, which makes Saxenda and Wegovy. Dr. Aronne is a consultant and investigator for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Eli Lilly, maker of the anti-obesity drug Zepbound, announced this week the launch of LillyDirect, a direct-to-patient portal, allowing some patients to obtain its drug for as little as $25 a month.

The move is seen as a major shift in the way these popular medications can reach patients.

For many of the 42 million Americans with obesity, weight loss medications such as Wegovy, Saxenda, and the brand-new Zepbound can be a godsend, helping them lose the excess pounds they’ve struggled with for decades or a lifetime.

But getting these medications has been a struggle for many who are eligible. Shortages of the drugs have been one barrier, and costs of up to $1,300 monthly — the price tag without insurance coverage — are another hurdle.

But 2024 may be a much brighter year, thanks to Lilly’s new portal as well as other developments:

Insurance coverage on private health plans, while still spotty, may be improving. Federal legislators are fighting a 2003 law that forbids Medicare from paying for the medications when prescribed for obesity.

New research found that semaglutide (Wegovy) can reduce the risk of recurrent strokes and heart attacks as well as deaths from cardiovascular events in those with obesity and preexisting cardiovascular disease (or diseases of the heart and blood vessels), a finding experts said should get the attention of health insurers.

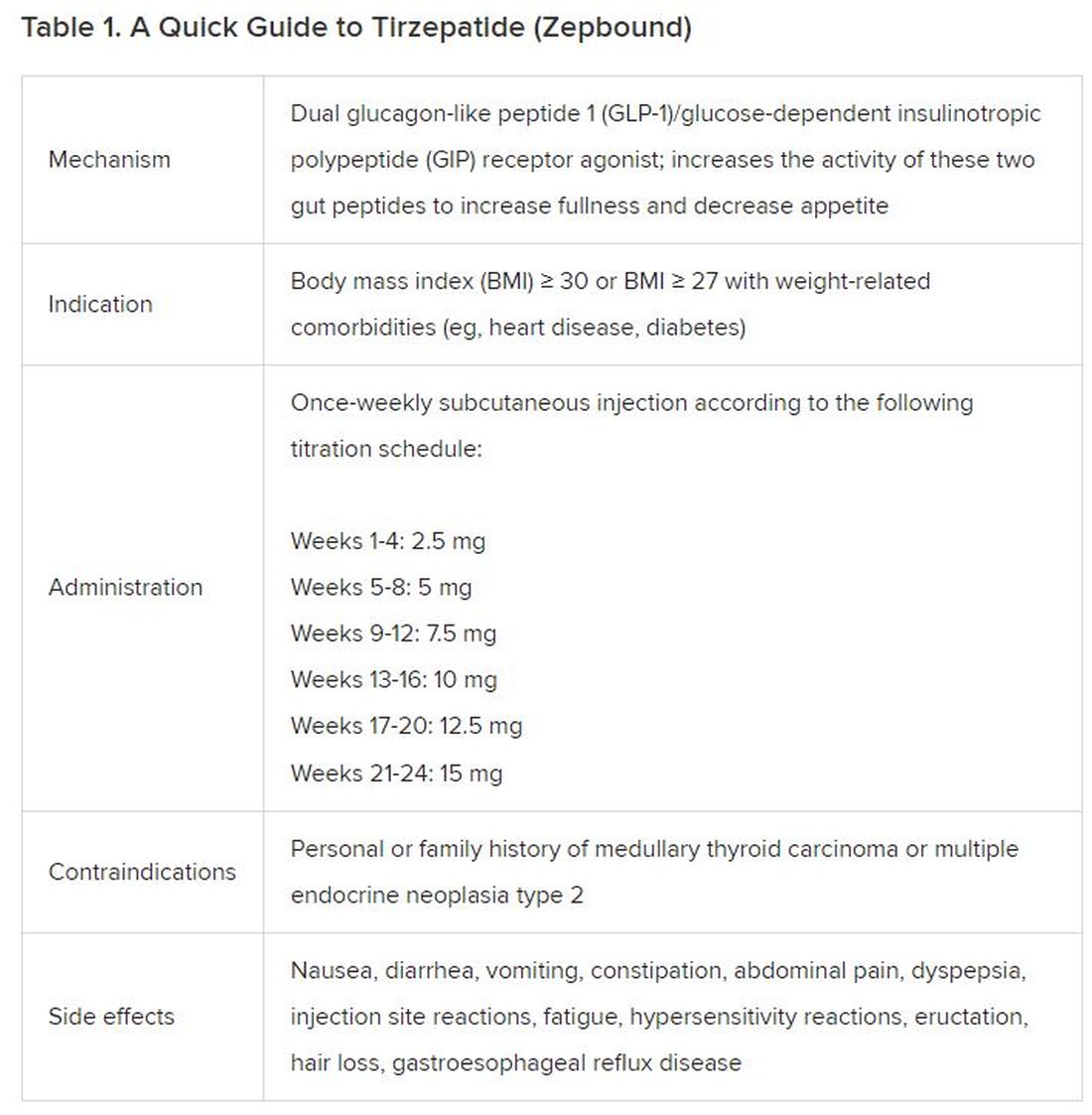

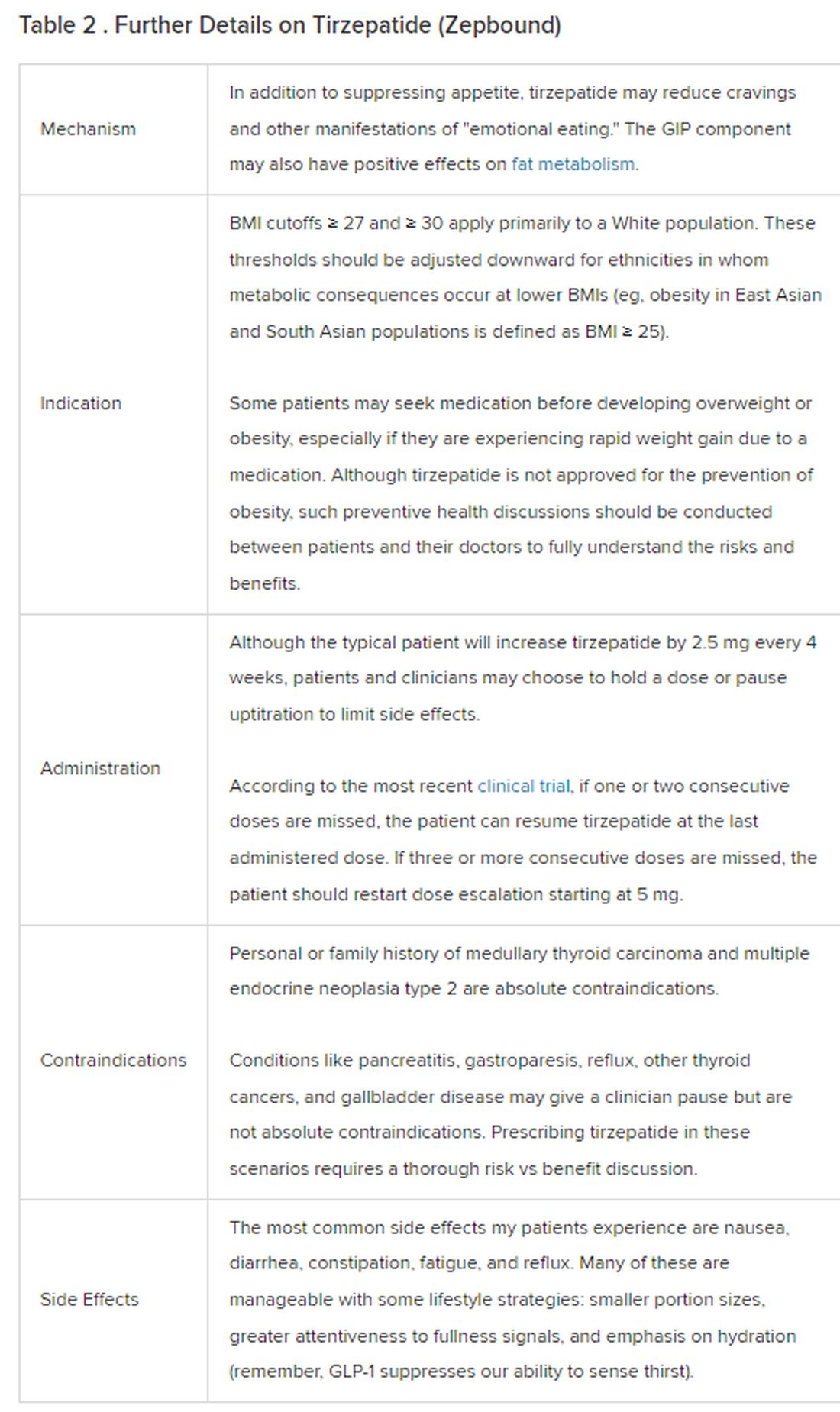

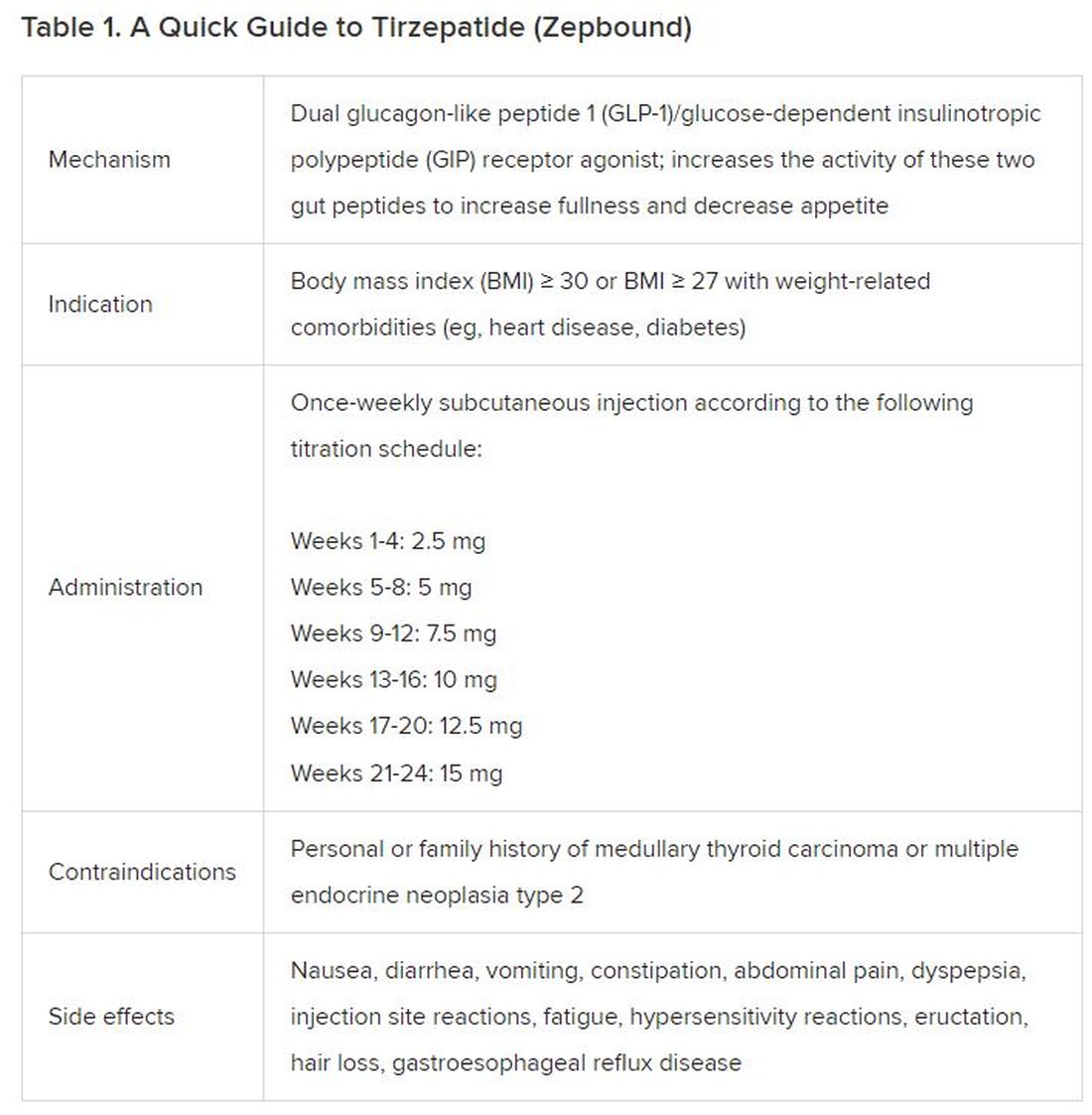

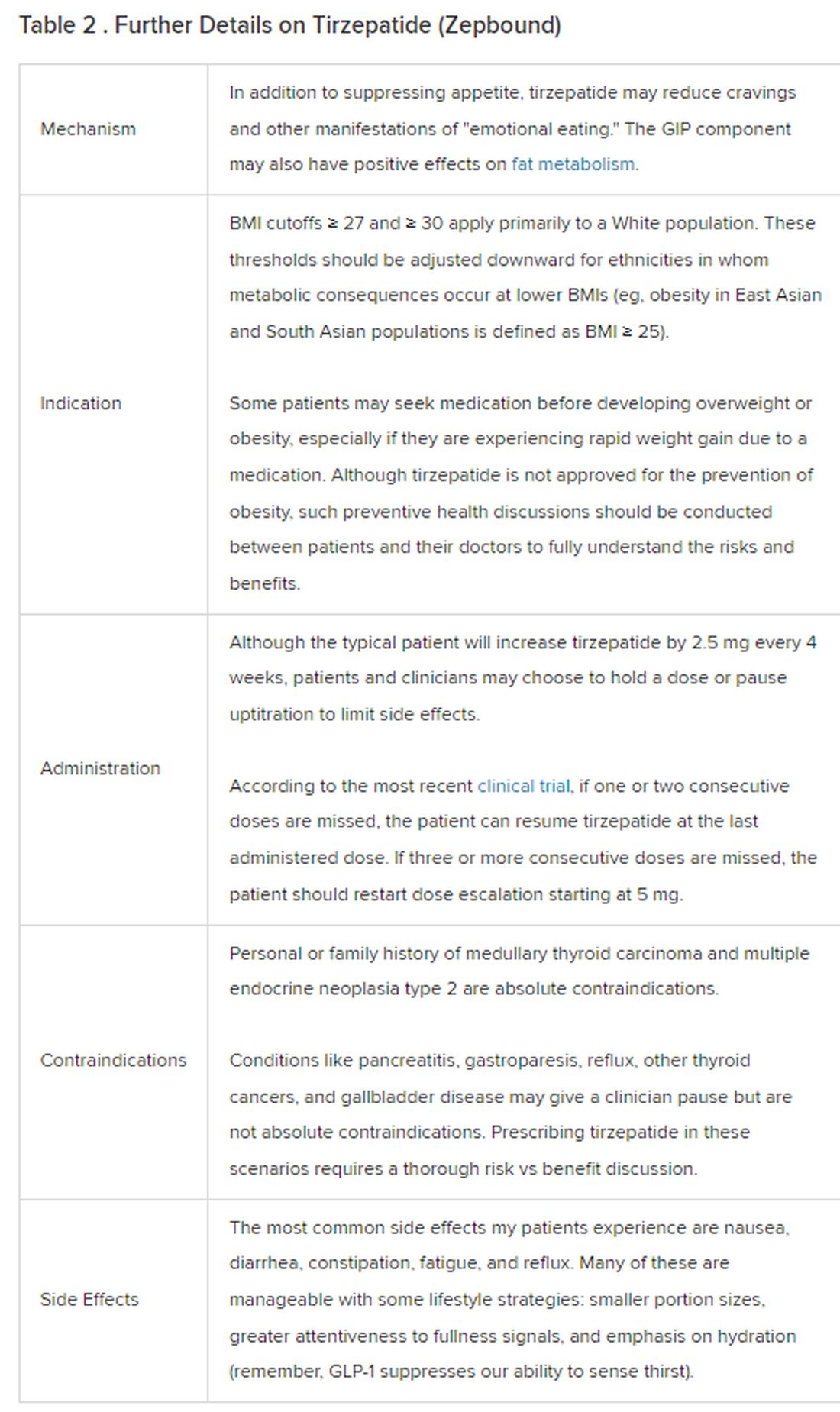

The medications, also referred to as GLP-1 agonists, work by activating the receptors of hormones (called glucagon-like peptide 1 and others) that are naturally released after eating. That, in turn, makes you feel more full, leading to weight loss of up to 22% for some. The medications are approved for those with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or a BMI of 27 with at least one other weight-related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol. The medicines, injected weekly or more often, are prescribed along with advice about a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

LillyDirect

Patients can access the obesity medicines through the telehealth platform FORM. Patients reach independent telehealth providers, according to Lilly, who can complement a patient’s current doctor or be an alternative to in-patient care in some cases.

Eli Lilly officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Some obesity experts welcomed the new service. “Any program that improves availability and affordability of these ground-breaking medications is welcome news for our long-suffering patients,” said Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, a long-time obesity researcher.

“It’s a great move for Lilly to do,” agreed Caroline Apovian, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who is also a veteran obesity specialist. “It is trying to help the accessibility issue and do it responsibly.”

“The bottom line is, there is an overwhelming amount of consumer need and desire for these medications and not enough channels [to provide them],” said Zeev Neuwirth, MD, a former executive at Atrium Health who writes about health care trends. “Eli Lilly is responding to a market need that is out there and quite honestly continuing to grow.”

There are still concerns and questions, Dr. Neuwirth said, “especially since this is to my knowledge the first of its kind in terms of a pharmaceutical manufacturer directly dispensing medication in this nontraditional way.”

He called for transparency between telehealth providers and the pharmaceutical company to rule out any conflicts of interest.

The American College of Physicians, an organization of internal medicine doctors and others, issued a statement expressing concern. Omar T. Atiq, MD, group’s president, said his organization is “concerned by the development of websites that enable patients to order prescription medications directly from the drugmakers. While information on in-person care is available, this direct-to-consumer approach is primarily oriented around the use of telehealth services to prescribe a drug maker’s products.”

The group urged that an established patient-doctor relationship be present, or that care should happen in consultation with a doctor who does have an established relationship (the latter an option offered by Lilly). “These direct-to-consumer services have the potential to leave patients confused and misinformed about medications.”

Heart Attack, Stroke Reduction Benefits

Previous research has found that the GLP-1 medicines such as Ozempic (semaglutide), which the FDA approved to treat diabetes, also reduce the risk of cardiovascular issues such as strokes and heart attacks. Now, new research finds that semaglutide at the Wegovy dose (usually slightly higher than the Ozempic dose for diabetes) also has those benefits in those who don›t have a diabetes diagnosis but do have obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In a clinical trial sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the maker of Wegovy, half of more than 17,000 people with obesity were given semaglutide (Wegovy); the other half got a placebo. Compared to those on the placebo, those who took the Wegovy had a 20% reduction in strokes, heart attacks, and deaths from cardiovascular causes over a 33-month period.

The study results are a “big deal,” Dr. Aronne said. The results make it clear that those with obesity but not diabetes will get the cardiovascular benefits from the treatment as well. While more analysis is necessary, he said the important point is that the study showed that reducing body weight is linked to improvement in critical health outcomes.

As the research evolves, he said, it’s going to be difficult for insurers to deny medications in the face of those findings, which promise reductions in long-term health care costs.

Insurance Coverage

In November, the American Medical Association voted to adopt a policy to urge insurance coverage for evidence-based treatment for obesity, including the new obesity medications.

“No single organization is going to be able to convince insurers and employers to cover this,” Dr. Aronne said. “But I think a prominent organization like the AMA adding their voice to the rising chorus is going to help.”

Coverage of GLP-1 medications could nearly double in 2024, according to a survey of 500 human resources decision-makers released in October by Accolade, a personalized health care advocacy and delivery company. While 25% of respondents said they currently offered coverage when the survey was done in August and September, 43% said they intend to offer coverage in 2024.

In an email, David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a health care industry association, said: “Every American deserves affordable coverage and high-quality care, and that includes coverage and care for evidence-based obesity treatments and therapies.”

He said “clinical leaders and other experts at health insurance providers routinely review the evidence for all types of treatments, including treatments for obesity, and offer multiple options to patients — ranging from lifestyle changes and nutrition counseling, to surgical interventions, to prescription drugs.”

Mr. Allen said the evidence that obesity drugs help with weight loss “is still evolving.”

“And some patients are experiencing bad effects related to these drugs such as vomiting and nausea, for example, and the likelihood of gaining the weight back when discontinuing the drugs,” he said.

Others are fighting for Medicare coverage, while some experts contend the costs of that coverage would be overwhelming. A bipartisan bill, the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act of 2023, would allow coverage under Medicare›s prescription drug benefit for drugs used for the treatment of obesity or for weigh loss management for people who are overweight. Some say it›s an uphill climb, citing a Vanderbilt University analysis that found giving just 10% of Medicare-eligible patients the drugs would cost $13.6 billion to more than $26 billion.

However, a white paper from the University of Southern California concluded that the value to society of covering the drugs for Medicare recipients would equal nearly $1 trillion over 10 years, citing savings in hospitalizations and other health care costs.

Comprehensive insurance coverage is needed, Dr. Apovian said. Private insurance plans, Medicare, and Medicaid must all realize the importance of covering what has been now shown to be life-saving drugs, she said.

Broader coverage might also reduce the number of patients getting obesity drugs from unreliable sources, in an effort to save money, and having adverse effects. The FDA warned against counterfeit semaglutide in December.

Long-Term Picture

Research suggests the obesity medications must be taken continuously, at least for most people, to maintain the weight loss. In a study of patients on Zepbound, Dr. Aronne and colleagues found that withdrawing the medication led people to regain weight, while continuing it led to maintaining and even increasing the initial weight loss. While some may be able to use the medications only from time to time, “the majority will have to take these on a chronic basis,” Dr. Aronne said.

Obesity, like high blood pressure and other chronic conditions, needs continuous treatment, Dr. Apovian said. No one would suggest withdrawing blood pressure medications that stabilize blood pressure; the same should be true for the obesity drugs, she said.

Dr. Apovian consults for FORM, the telehealth platform Lilly uses for LillyDirect, and consults for Novo Nordisk, which makes Saxenda and Wegovy. Dr. Aronne is a consultant and investigator for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Eli Lilly, maker of the anti-obesity drug Zepbound, announced this week the launch of LillyDirect, a direct-to-patient portal, allowing some patients to obtain its drug for as little as $25 a month.

The move is seen as a major shift in the way these popular medications can reach patients.

For many of the 42 million Americans with obesity, weight loss medications such as Wegovy, Saxenda, and the brand-new Zepbound can be a godsend, helping them lose the excess pounds they’ve struggled with for decades or a lifetime.

But getting these medications has been a struggle for many who are eligible. Shortages of the drugs have been one barrier, and costs of up to $1,300 monthly — the price tag without insurance coverage — are another hurdle.

But 2024 may be a much brighter year, thanks to Lilly’s new portal as well as other developments:

Insurance coverage on private health plans, while still spotty, may be improving. Federal legislators are fighting a 2003 law that forbids Medicare from paying for the medications when prescribed for obesity.

New research found that semaglutide (Wegovy) can reduce the risk of recurrent strokes and heart attacks as well as deaths from cardiovascular events in those with obesity and preexisting cardiovascular disease (or diseases of the heart and blood vessels), a finding experts said should get the attention of health insurers.

The medications, also referred to as GLP-1 agonists, work by activating the receptors of hormones (called glucagon-like peptide 1 and others) that are naturally released after eating. That, in turn, makes you feel more full, leading to weight loss of up to 22% for some. The medications are approved for those with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or a BMI of 27 with at least one other weight-related health condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol. The medicines, injected weekly or more often, are prescribed along with advice about a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.

LillyDirect

Patients can access the obesity medicines through the telehealth platform FORM. Patients reach independent telehealth providers, according to Lilly, who can complement a patient’s current doctor or be an alternative to in-patient care in some cases.

Eli Lilly officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Some obesity experts welcomed the new service. “Any program that improves availability and affordability of these ground-breaking medications is welcome news for our long-suffering patients,” said Louis Aronne, MD, director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, a long-time obesity researcher.

“It’s a great move for Lilly to do,” agreed Caroline Apovian, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who is also a veteran obesity specialist. “It is trying to help the accessibility issue and do it responsibly.”

“The bottom line is, there is an overwhelming amount of consumer need and desire for these medications and not enough channels [to provide them],” said Zeev Neuwirth, MD, a former executive at Atrium Health who writes about health care trends. “Eli Lilly is responding to a market need that is out there and quite honestly continuing to grow.”

There are still concerns and questions, Dr. Neuwirth said, “especially since this is to my knowledge the first of its kind in terms of a pharmaceutical manufacturer directly dispensing medication in this nontraditional way.”

He called for transparency between telehealth providers and the pharmaceutical company to rule out any conflicts of interest.

The American College of Physicians, an organization of internal medicine doctors and others, issued a statement expressing concern. Omar T. Atiq, MD, group’s president, said his organization is “concerned by the development of websites that enable patients to order prescription medications directly from the drugmakers. While information on in-person care is available, this direct-to-consumer approach is primarily oriented around the use of telehealth services to prescribe a drug maker’s products.”

The group urged that an established patient-doctor relationship be present, or that care should happen in consultation with a doctor who does have an established relationship (the latter an option offered by Lilly). “These direct-to-consumer services have the potential to leave patients confused and misinformed about medications.”

Heart Attack, Stroke Reduction Benefits

Previous research has found that the GLP-1 medicines such as Ozempic (semaglutide), which the FDA approved to treat diabetes, also reduce the risk of cardiovascular issues such as strokes and heart attacks. Now, new research finds that semaglutide at the Wegovy dose (usually slightly higher than the Ozempic dose for diabetes) also has those benefits in those who don›t have a diabetes diagnosis but do have obesity and cardiovascular disease.

In a clinical trial sponsored by Novo Nordisk, the maker of Wegovy, half of more than 17,000 people with obesity were given semaglutide (Wegovy); the other half got a placebo. Compared to those on the placebo, those who took the Wegovy had a 20% reduction in strokes, heart attacks, and deaths from cardiovascular causes over a 33-month period.

The study results are a “big deal,” Dr. Aronne said. The results make it clear that those with obesity but not diabetes will get the cardiovascular benefits from the treatment as well. While more analysis is necessary, he said the important point is that the study showed that reducing body weight is linked to improvement in critical health outcomes.

As the research evolves, he said, it’s going to be difficult for insurers to deny medications in the face of those findings, which promise reductions in long-term health care costs.

Insurance Coverage

In November, the American Medical Association voted to adopt a policy to urge insurance coverage for evidence-based treatment for obesity, including the new obesity medications.

“No single organization is going to be able to convince insurers and employers to cover this,” Dr. Aronne said. “But I think a prominent organization like the AMA adding their voice to the rising chorus is going to help.”

Coverage of GLP-1 medications could nearly double in 2024, according to a survey of 500 human resources decision-makers released in October by Accolade, a personalized health care advocacy and delivery company. While 25% of respondents said they currently offered coverage when the survey was done in August and September, 43% said they intend to offer coverage in 2024.

In an email, David Allen, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a health care industry association, said: “Every American deserves affordable coverage and high-quality care, and that includes coverage and care for evidence-based obesity treatments and therapies.”

He said “clinical leaders and other experts at health insurance providers routinely review the evidence for all types of treatments, including treatments for obesity, and offer multiple options to patients — ranging from lifestyle changes and nutrition counseling, to surgical interventions, to prescription drugs.”

Mr. Allen said the evidence that obesity drugs help with weight loss “is still evolving.”

“And some patients are experiencing bad effects related to these drugs such as vomiting and nausea, for example, and the likelihood of gaining the weight back when discontinuing the drugs,” he said.

Others are fighting for Medicare coverage, while some experts contend the costs of that coverage would be overwhelming. A bipartisan bill, the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act of 2023, would allow coverage under Medicare›s prescription drug benefit for drugs used for the treatment of obesity or for weigh loss management for people who are overweight. Some say it›s an uphill climb, citing a Vanderbilt University analysis that found giving just 10% of Medicare-eligible patients the drugs would cost $13.6 billion to more than $26 billion.

However, a white paper from the University of Southern California concluded that the value to society of covering the drugs for Medicare recipients would equal nearly $1 trillion over 10 years, citing savings in hospitalizations and other health care costs.

Comprehensive insurance coverage is needed, Dr. Apovian said. Private insurance plans, Medicare, and Medicaid must all realize the importance of covering what has been now shown to be life-saving drugs, she said.

Broader coverage might also reduce the number of patients getting obesity drugs from unreliable sources, in an effort to save money, and having adverse effects. The FDA warned against counterfeit semaglutide in December.

Long-Term Picture

Research suggests the obesity medications must be taken continuously, at least for most people, to maintain the weight loss. In a study of patients on Zepbound, Dr. Aronne and colleagues found that withdrawing the medication led people to regain weight, while continuing it led to maintaining and even increasing the initial weight loss. While some may be able to use the medications only from time to time, “the majority will have to take these on a chronic basis,” Dr. Aronne said.

Obesity, like high blood pressure and other chronic conditions, needs continuous treatment, Dr. Apovian said. No one would suggest withdrawing blood pressure medications that stabilize blood pressure; the same should be true for the obesity drugs, she said.

Dr. Apovian consults for FORM, the telehealth platform Lilly uses for LillyDirect, and consults for Novo Nordisk, which makes Saxenda and Wegovy. Dr. Aronne is a consultant and investigator for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and other companies.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Walking Fast May Help Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

Walking is a simple, cost-free form of exercise that benefits physical, social, and mental health in many ways. Several clinical trials have shown that walking regularly is associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, and having a higher daily step count is linked to a decreased risk for premature death.

Walking and Diabetes

In recent years, the link between walking speed and the risk for multiple health problems has sparked keen interest. Data suggest that a faster walking pace may have a greater physiological response and may be associated with more favorable health advantages than a slow walking pace. A previous meta-analysis of eight cohort studies suggested that individuals in the fastest walking-pace category (median = 5.6 km/h) had a 44% lower risk for stroke than those in the slowest walking-pace category (median = 1.6 km/h). The risk for the former decreased by 13% for every 1 km/h increment in baseline walking pace.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the most common metabolic diseases in the world. People with this type of diabetes have an increased risk for microvascular and macrovascular complications and a shorter life expectancy. Approximately 537 million adults are estimated to be living with diabetes worldwide, and this number is expected to reach 783 million by 2045.

Physical activity is an essential component of T2D prevention programs and can favorably affect blood sugar control. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that being physically active was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of acquiring T2D in the general population, and regular walking was associated with a 15% reduction in the risk of developing T2D.

However, no studies have investigated the link between different walking speeds and the risk for T2D. A team from the Research Center at the Semnan University of Medical Sciences in Iran carried out a systematic review of the association between walking speed and the risk of developing T2D in adults; this review was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

10 Cohort Studies

This systematic review used publications (1999-2022) available in the usual data sources (PubMed, Scopus, CENTRAL, and Web of Science). Random-effects meta-analyses were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) based on different walking speeds. The researchers rated the credibility of subgroup differences and the certainty of evidence using the Instrument to assess the Credibility of Effect Modification ANalyses (ICEMAN) and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tools, respectively.

Of the 508,121 potential participants, 18,410 adults from 10 prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom were deemed eligible. The proportion of women was between 52% and 73%, depending on the cohort. Follow-up duration varied from 3 to 11.1 years (median, 8 years).

Five cohort studies measured walking speed using stopwatch testing, while the other five used self-assessed questionnaires. To define cases of T2D, seven studies used objective methods such as blood glucose measurement or linkage with medical records, and in three cohorts, self-assessment questionnaires were used (these were checked against patient records). All studies controlled age, sex, and tobacco consumption in the multivariate analyses, and some controlled just alcohol consumption, blood pressure, total physical activity volume, body mass index, time spent walking or daily step count, and a family history of diabetes.

The Right Speed

The authors first categorized walking speed into four prespecified levels: Easy or casual (< 2 mph or 3.2 km/h), average or normal (2-3 mph or 3.2-4.8 km/h), fairly brisk (3-4 mph or 4.8-6.4 km/h), and very brisk or brisk/striding (> 4 mph or > 6.4 km/h).

Four cohort studies with 6,520 cases of T2D among 160,321 participants reported information on average or normal walking. Participants with average or normal walking were at a 15% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.85 [95% CI, 0.70-1.00]; RD = 0.86 [1.72-0]). Ten cohort studies with 18,410 cases among 508,121 participants reported information on fairly brisk walking. Those with fairly brisk walking were at a 24% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.76 [0.65-0.87]; I2 = 90%; RD = 1.38 [2.01-0.75]).

There was no significant or credible subgroup difference by adjustment for the total physical activity or time spent walking per day. The dose-response analysis suggested that the risk for T2D decreased significantly at a walking speed of 4 km/h and above.

Study Limitations

This meta-analysis has strengths that may increase the generalizability of its results. The researchers included cohort studies, which allowed them to consider the temporal sequence of exposure and outcome. Cohort studies are less affected by recall and selection biases compared with retrospective case–control studies, which increase the likelihood of causality. The researchers also assessed the credibility of subgroup differences using the recently developed ICEMAN tool, calculated both relative and absolute risks, and rated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Some shortcomings must be considered. Most of the studies included in the present review were rated as having a serious risk for bias, with the most important biases resulting from inadequate adjustment for potential confounders and the methods used for walking speed assessment and diagnosis of T2D. In addition, the findings could have been subject to reverse causality bias because participants with faster walking speed are more likely to perform more physical activity and have better cardiorespiratory fitness, greater muscle mass, and better health status. However, the subgroup analyses of fairly brisk and brisk/striding walking indicated that there were no significant subgroup differences by follow-up duration and that the significant inverse associations remained stable in the subgroup of cohort studies with a follow-up duration of > 10 years.

The authors concluded that While current strategies to increase total walking time are beneficial, it may also be reasonable to encourage people to walk at faster speeds to further increase the health benefits of walking.”

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Walking is a simple, cost-free form of exercise that benefits physical, social, and mental health in many ways. Several clinical trials have shown that walking regularly is associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, and having a higher daily step count is linked to a decreased risk for premature death.

Walking and Diabetes

In recent years, the link between walking speed and the risk for multiple health problems has sparked keen interest. Data suggest that a faster walking pace may have a greater physiological response and may be associated with more favorable health advantages than a slow walking pace. A previous meta-analysis of eight cohort studies suggested that individuals in the fastest walking-pace category (median = 5.6 km/h) had a 44% lower risk for stroke than those in the slowest walking-pace category (median = 1.6 km/h). The risk for the former decreased by 13% for every 1 km/h increment in baseline walking pace.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the most common metabolic diseases in the world. People with this type of diabetes have an increased risk for microvascular and macrovascular complications and a shorter life expectancy. Approximately 537 million adults are estimated to be living with diabetes worldwide, and this number is expected to reach 783 million by 2045.

Physical activity is an essential component of T2D prevention programs and can favorably affect blood sugar control. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that being physically active was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of acquiring T2D in the general population, and regular walking was associated with a 15% reduction in the risk of developing T2D.

However, no studies have investigated the link between different walking speeds and the risk for T2D. A team from the Research Center at the Semnan University of Medical Sciences in Iran carried out a systematic review of the association between walking speed and the risk of developing T2D in adults; this review was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

10 Cohort Studies

This systematic review used publications (1999-2022) available in the usual data sources (PubMed, Scopus, CENTRAL, and Web of Science). Random-effects meta-analyses were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) based on different walking speeds. The researchers rated the credibility of subgroup differences and the certainty of evidence using the Instrument to assess the Credibility of Effect Modification ANalyses (ICEMAN) and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tools, respectively.

Of the 508,121 potential participants, 18,410 adults from 10 prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom were deemed eligible. The proportion of women was between 52% and 73%, depending on the cohort. Follow-up duration varied from 3 to 11.1 years (median, 8 years).

Five cohort studies measured walking speed using stopwatch testing, while the other five used self-assessed questionnaires. To define cases of T2D, seven studies used objective methods such as blood glucose measurement or linkage with medical records, and in three cohorts, self-assessment questionnaires were used (these were checked against patient records). All studies controlled age, sex, and tobacco consumption in the multivariate analyses, and some controlled just alcohol consumption, blood pressure, total physical activity volume, body mass index, time spent walking or daily step count, and a family history of diabetes.

The Right Speed

The authors first categorized walking speed into four prespecified levels: Easy or casual (< 2 mph or 3.2 km/h), average or normal (2-3 mph or 3.2-4.8 km/h), fairly brisk (3-4 mph or 4.8-6.4 km/h), and very brisk or brisk/striding (> 4 mph or > 6.4 km/h).

Four cohort studies with 6,520 cases of T2D among 160,321 participants reported information on average or normal walking. Participants with average or normal walking were at a 15% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.85 [95% CI, 0.70-1.00]; RD = 0.86 [1.72-0]). Ten cohort studies with 18,410 cases among 508,121 participants reported information on fairly brisk walking. Those with fairly brisk walking were at a 24% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.76 [0.65-0.87]; I2 = 90%; RD = 1.38 [2.01-0.75]).

There was no significant or credible subgroup difference by adjustment for the total physical activity or time spent walking per day. The dose-response analysis suggested that the risk for T2D decreased significantly at a walking speed of 4 km/h and above.

Study Limitations

This meta-analysis has strengths that may increase the generalizability of its results. The researchers included cohort studies, which allowed them to consider the temporal sequence of exposure and outcome. Cohort studies are less affected by recall and selection biases compared with retrospective case–control studies, which increase the likelihood of causality. The researchers also assessed the credibility of subgroup differences using the recently developed ICEMAN tool, calculated both relative and absolute risks, and rated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Some shortcomings must be considered. Most of the studies included in the present review were rated as having a serious risk for bias, with the most important biases resulting from inadequate adjustment for potential confounders and the methods used for walking speed assessment and diagnosis of T2D. In addition, the findings could have been subject to reverse causality bias because participants with faster walking speed are more likely to perform more physical activity and have better cardiorespiratory fitness, greater muscle mass, and better health status. However, the subgroup analyses of fairly brisk and brisk/striding walking indicated that there were no significant subgroup differences by follow-up duration and that the significant inverse associations remained stable in the subgroup of cohort studies with a follow-up duration of > 10 years.

The authors concluded that While current strategies to increase total walking time are beneficial, it may also be reasonable to encourage people to walk at faster speeds to further increase the health benefits of walking.”

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Walking is a simple, cost-free form of exercise that benefits physical, social, and mental health in many ways. Several clinical trials have shown that walking regularly is associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, and having a higher daily step count is linked to a decreased risk for premature death.

Walking and Diabetes

In recent years, the link between walking speed and the risk for multiple health problems has sparked keen interest. Data suggest that a faster walking pace may have a greater physiological response and may be associated with more favorable health advantages than a slow walking pace. A previous meta-analysis of eight cohort studies suggested that individuals in the fastest walking-pace category (median = 5.6 km/h) had a 44% lower risk for stroke than those in the slowest walking-pace category (median = 1.6 km/h). The risk for the former decreased by 13% for every 1 km/h increment in baseline walking pace.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the most common metabolic diseases in the world. People with this type of diabetes have an increased risk for microvascular and macrovascular complications and a shorter life expectancy. Approximately 537 million adults are estimated to be living with diabetes worldwide, and this number is expected to reach 783 million by 2045.

Physical activity is an essential component of T2D prevention programs and can favorably affect blood sugar control. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that being physically active was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of acquiring T2D in the general population, and regular walking was associated with a 15% reduction in the risk of developing T2D.

However, no studies have investigated the link between different walking speeds and the risk for T2D. A team from the Research Center at the Semnan University of Medical Sciences in Iran carried out a systematic review of the association between walking speed and the risk of developing T2D in adults; this review was published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

10 Cohort Studies

This systematic review used publications (1999-2022) available in the usual data sources (PubMed, Scopus, CENTRAL, and Web of Science). Random-effects meta-analyses were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) based on different walking speeds. The researchers rated the credibility of subgroup differences and the certainty of evidence using the Instrument to assess the Credibility of Effect Modification ANalyses (ICEMAN) and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tools, respectively.

Of the 508,121 potential participants, 18,410 adults from 10 prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom were deemed eligible. The proportion of women was between 52% and 73%, depending on the cohort. Follow-up duration varied from 3 to 11.1 years (median, 8 years).

Five cohort studies measured walking speed using stopwatch testing, while the other five used self-assessed questionnaires. To define cases of T2D, seven studies used objective methods such as blood glucose measurement or linkage with medical records, and in three cohorts, self-assessment questionnaires were used (these were checked against patient records). All studies controlled age, sex, and tobacco consumption in the multivariate analyses, and some controlled just alcohol consumption, blood pressure, total physical activity volume, body mass index, time spent walking or daily step count, and a family history of diabetes.

The Right Speed

The authors first categorized walking speed into four prespecified levels: Easy or casual (< 2 mph or 3.2 km/h), average or normal (2-3 mph or 3.2-4.8 km/h), fairly brisk (3-4 mph or 4.8-6.4 km/h), and very brisk or brisk/striding (> 4 mph or > 6.4 km/h).

Four cohort studies with 6,520 cases of T2D among 160,321 participants reported information on average or normal walking. Participants with average or normal walking were at a 15% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.85 [95% CI, 0.70-1.00]; RD = 0.86 [1.72-0]). Ten cohort studies with 18,410 cases among 508,121 participants reported information on fairly brisk walking. Those with fairly brisk walking were at a 24% lower risk for T2D than those with easy or casual walking (RR = 0.76 [0.65-0.87]; I2 = 90%; RD = 1.38 [2.01-0.75]).

There was no significant or credible subgroup difference by adjustment for the total physical activity or time spent walking per day. The dose-response analysis suggested that the risk for T2D decreased significantly at a walking speed of 4 km/h and above.

Study Limitations

This meta-analysis has strengths that may increase the generalizability of its results. The researchers included cohort studies, which allowed them to consider the temporal sequence of exposure and outcome. Cohort studies are less affected by recall and selection biases compared with retrospective case–control studies, which increase the likelihood of causality. The researchers also assessed the credibility of subgroup differences using the recently developed ICEMAN tool, calculated both relative and absolute risks, and rated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Some shortcomings must be considered. Most of the studies included in the present review were rated as having a serious risk for bias, with the most important biases resulting from inadequate adjustment for potential confounders and the methods used for walking speed assessment and diagnosis of T2D. In addition, the findings could have been subject to reverse causality bias because participants with faster walking speed are more likely to perform more physical activity and have better cardiorespiratory fitness, greater muscle mass, and better health status. However, the subgroup analyses of fairly brisk and brisk/striding walking indicated that there were no significant subgroup differences by follow-up duration and that the significant inverse associations remained stable in the subgroup of cohort studies with a follow-up duration of > 10 years.

The authors concluded that While current strategies to increase total walking time are beneficial, it may also be reasonable to encourage people to walk at faster speeds to further increase the health benefits of walking.”

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE

Spending the Holidays With GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: 5 Things to Know

As an endocrinologist, I treat many patients who have diabetes, obesity, or both. Antiobesity medications, particularly the class of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), are our first support tools when nutrition and physical activity aren’t enough.

1. Be mindful of fullness cues.

GLP-1 RAs increase satiety; they help patients feel fuller sooner within a meal and longer in between meals. This means consuming the “usual” at a holiday gathering makes them feel as if they ate too much, and often this will result in more side effects, such as nausea and reflux.

Patient tip: A good rule of thumb is to anticipate feeling full with half of your usual portion. Start with half a plate and reassess your hunger level after finishing.

2. Distinguish between hunger and “food noise.”

Ask your patients, “Do you ever find yourself eating even when you’re not hungry?” Many people eat because of emotions (eg, stress, anxiety, happiness), social situations, or cultural expectations. This type of food consumption is what scientists call “hedonic food intake” and may be driven by the “food noise” that patients describe as persistent thoughts about food in the absence of physiologic hunger. Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) has been found to reduce cravings, though other research has shown that emotional eating may blunt the effect of GLP-1 RAs.

Patient tip: Recognize when you might be seeking food for reasons other than hunger, and try a different way to address the cue (eg, chat with a friend or family member, go for a walk).

3. Be careful with alcohol.

GLP-1 RAs are being researched as potential treatments for alcohol use disorder. Many patients report less interest in alcohol and a lower tolerance to alcohol when they are taking a GLP-1 RA. Additionally, GLP-1 RAs may be a risk factor for pancreatitis, which can be caused by consuming too much alcohol.

Patient tip: The standard recommendation remains true: If drinking alcohol, limit to one to two servings per day, but also know that reduced intake or interest is normal when taking a GLP-1 RA.

4. Be aware of sickness vs side effects.

With holiday travel and the winter season, it is common for people to catch a cold or a stomach bug. Symptoms of common illnesses might include fatigue, loss of appetite, or diarrhea. These symptoms overlap with side effects of antiobesity medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Patient tip: If you are experiencing constitutional or gastrointestinal symptoms due to illness, speak with your board-certified obesity medicine doctor, who may recommend a temporary medication adjustment to avoid excess side effects.

5. Stay strong against weight stigma.

The holiday season can be a stressful time, especially as patients are reconnecting with people who have not been a part of their health or weight loss journey. Unfortunately, weight bias and weight stigma remain rampant. Many people don’t understand the biology of obesity and refuse to accept the necessity of medical treatment. They may be surrounded by opinions, often louder and less informed.

Patient tip: Remember that obesity is a medical disease. Tell your nosy cousin that it’s a private health matter and that your decisions are your own.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed financial relationships with Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As an endocrinologist, I treat many patients who have diabetes, obesity, or both. Antiobesity medications, particularly the class of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), are our first support tools when nutrition and physical activity aren’t enough.

1. Be mindful of fullness cues.

GLP-1 RAs increase satiety; they help patients feel fuller sooner within a meal and longer in between meals. This means consuming the “usual” at a holiday gathering makes them feel as if they ate too much, and often this will result in more side effects, such as nausea and reflux.

Patient tip: A good rule of thumb is to anticipate feeling full with half of your usual portion. Start with half a plate and reassess your hunger level after finishing.

2. Distinguish between hunger and “food noise.”

Ask your patients, “Do you ever find yourself eating even when you’re not hungry?” Many people eat because of emotions (eg, stress, anxiety, happiness), social situations, or cultural expectations. This type of food consumption is what scientists call “hedonic food intake” and may be driven by the “food noise” that patients describe as persistent thoughts about food in the absence of physiologic hunger. Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) has been found to reduce cravings, though other research has shown that emotional eating may blunt the effect of GLP-1 RAs.

Patient tip: Recognize when you might be seeking food for reasons other than hunger, and try a different way to address the cue (eg, chat with a friend or family member, go for a walk).

3. Be careful with alcohol.

GLP-1 RAs are being researched as potential treatments for alcohol use disorder. Many patients report less interest in alcohol and a lower tolerance to alcohol when they are taking a GLP-1 RA. Additionally, GLP-1 RAs may be a risk factor for pancreatitis, which can be caused by consuming too much alcohol.

Patient tip: The standard recommendation remains true: If drinking alcohol, limit to one to two servings per day, but also know that reduced intake or interest is normal when taking a GLP-1 RA.

4. Be aware of sickness vs side effects.

With holiday travel and the winter season, it is common for people to catch a cold or a stomach bug. Symptoms of common illnesses might include fatigue, loss of appetite, or diarrhea. These symptoms overlap with side effects of antiobesity medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Patient tip: If you are experiencing constitutional or gastrointestinal symptoms due to illness, speak with your board-certified obesity medicine doctor, who may recommend a temporary medication adjustment to avoid excess side effects.

5. Stay strong against weight stigma.

The holiday season can be a stressful time, especially as patients are reconnecting with people who have not been a part of their health or weight loss journey. Unfortunately, weight bias and weight stigma remain rampant. Many people don’t understand the biology of obesity and refuse to accept the necessity of medical treatment. They may be surrounded by opinions, often louder and less informed.

Patient tip: Remember that obesity is a medical disease. Tell your nosy cousin that it’s a private health matter and that your decisions are your own.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed financial relationships with Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As an endocrinologist, I treat many patients who have diabetes, obesity, or both. Antiobesity medications, particularly the class of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), are our first support tools when nutrition and physical activity aren’t enough.

1. Be mindful of fullness cues.

GLP-1 RAs increase satiety; they help patients feel fuller sooner within a meal and longer in between meals. This means consuming the “usual” at a holiday gathering makes them feel as if they ate too much, and often this will result in more side effects, such as nausea and reflux.

Patient tip: A good rule of thumb is to anticipate feeling full with half of your usual portion. Start with half a plate and reassess your hunger level after finishing.

2. Distinguish between hunger and “food noise.”

Ask your patients, “Do you ever find yourself eating even when you’re not hungry?” Many people eat because of emotions (eg, stress, anxiety, happiness), social situations, or cultural expectations. This type of food consumption is what scientists call “hedonic food intake” and may be driven by the “food noise” that patients describe as persistent thoughts about food in the absence of physiologic hunger. Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) has been found to reduce cravings, though other research has shown that emotional eating may blunt the effect of GLP-1 RAs.

Patient tip: Recognize when you might be seeking food for reasons other than hunger, and try a different way to address the cue (eg, chat with a friend or family member, go for a walk).

3. Be careful with alcohol.

GLP-1 RAs are being researched as potential treatments for alcohol use disorder. Many patients report less interest in alcohol and a lower tolerance to alcohol when they are taking a GLP-1 RA. Additionally, GLP-1 RAs may be a risk factor for pancreatitis, which can be caused by consuming too much alcohol.

Patient tip: The standard recommendation remains true: If drinking alcohol, limit to one to two servings per day, but also know that reduced intake or interest is normal when taking a GLP-1 RA.

4. Be aware of sickness vs side effects.

With holiday travel and the winter season, it is common for people to catch a cold or a stomach bug. Symptoms of common illnesses might include fatigue, loss of appetite, or diarrhea. These symptoms overlap with side effects of antiobesity medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide.

Patient tip: If you are experiencing constitutional or gastrointestinal symptoms due to illness, speak with your board-certified obesity medicine doctor, who may recommend a temporary medication adjustment to avoid excess side effects.

5. Stay strong against weight stigma.

The holiday season can be a stressful time, especially as patients are reconnecting with people who have not been a part of their health or weight loss journey. Unfortunately, weight bias and weight stigma remain rampant. Many people don’t understand the biology of obesity and refuse to accept the necessity of medical treatment. They may be surrounded by opinions, often louder and less informed.

Patient tip: Remember that obesity is a medical disease. Tell your nosy cousin that it’s a private health matter and that your decisions are your own.

Dr. Tchang is Assistant Professor, Clinical Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine; Physician, Department of Medicine, Iris Cantor Women’s Health Center, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, New York, NY. She disclosed financial relationships with Gelesis and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ED Visits for Diabetes on the Rise in the US

Emergency department (ED) visits by adults with diabetes increased by more than 25% since 2012, with the highest rates among Blacks and those aged over 65 years, a new data brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics shows.

In 2021, diabetes was the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the brief, published online on December 19, 2023. Its frequency is increasing in young people, and increasing age is a risk factor for hospitalization.

The latest data show that in 2020-2021, the overall annual ED visit rate was 72.2 visits per 1000 adults with diabetes, with no significant difference in terms of sex (75.1 visits per 1000 women vs 69.1 visits per 1000 men). By race/ethnicity, Blacks had the highest rates, at 135.5 visits per 1000 adults, followed by Whites (69.9) and Hispanics (52.3). The rates increased with age for both women and men, and among the three race/ethnic groups.

Comorbidities Count

The most ED visits were made by patients with diabetes and two to four other chronic conditions (541.4 visits per 1000 visits). Rates for patients without other chronic conditions were the lowest (90.2).

Among individuals with diabetes aged 18-44 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (402.0) and lowest among those with five or more other conditions (93.8).

Among patients aged 45-64 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (526.4) and lowest for those without other conditions (87.7). In the 65 years and older group, rates were the highest for individuals with two to four other chronic conditions (605.2), followed by five or more conditions (217.7), one other condition (140.6), and no other conditions (36.5).

Notably, the ED visit rates for those with two to four or five or more other chronic conditions increased with age, whereas visits for those with no other chronic conditions or one other condition decreased with age.

Decade-Long Trend

ED visit rates among adults with diabetes increased throughout the past decade, from 48.6 visits per 1000 adults in 2012 to 74.9 per 1000 adults in 2021. Rates for those aged 65 and older were higher than all other age groups, increasing from 113.4 to 156.8. Increases were also seen among those aged 45-64 years (53.1 in 2012 to 89.2 in 2021) and 18-44 (20.9 in 2012 to 26.4 in 2016, then plateauing from 2016-2021).

Data are based on a sample of 4051 ED visits, representing about 18,238,000 average annual visits made by adults with diabetes to nonfederal, general, and short-stay hospitals during 2020-2021.

Taken together, these most recent estimates “show an increasing trend in rates by adults with diabetes in the ED setting,” the authors concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Emergency department (ED) visits by adults with diabetes increased by more than 25% since 2012, with the highest rates among Blacks and those aged over 65 years, a new data brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics shows.

In 2021, diabetes was the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the brief, published online on December 19, 2023. Its frequency is increasing in young people, and increasing age is a risk factor for hospitalization.

The latest data show that in 2020-2021, the overall annual ED visit rate was 72.2 visits per 1000 adults with diabetes, with no significant difference in terms of sex (75.1 visits per 1000 women vs 69.1 visits per 1000 men). By race/ethnicity, Blacks had the highest rates, at 135.5 visits per 1000 adults, followed by Whites (69.9) and Hispanics (52.3). The rates increased with age for both women and men, and among the three race/ethnic groups.

Comorbidities Count

The most ED visits were made by patients with diabetes and two to four other chronic conditions (541.4 visits per 1000 visits). Rates for patients without other chronic conditions were the lowest (90.2).

Among individuals with diabetes aged 18-44 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (402.0) and lowest among those with five or more other conditions (93.8).

Among patients aged 45-64 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (526.4) and lowest for those without other conditions (87.7). In the 65 years and older group, rates were the highest for individuals with two to four other chronic conditions (605.2), followed by five or more conditions (217.7), one other condition (140.6), and no other conditions (36.5).

Notably, the ED visit rates for those with two to four or five or more other chronic conditions increased with age, whereas visits for those with no other chronic conditions or one other condition decreased with age.

Decade-Long Trend

ED visit rates among adults with diabetes increased throughout the past decade, from 48.6 visits per 1000 adults in 2012 to 74.9 per 1000 adults in 2021. Rates for those aged 65 and older were higher than all other age groups, increasing from 113.4 to 156.8. Increases were also seen among those aged 45-64 years (53.1 in 2012 to 89.2 in 2021) and 18-44 (20.9 in 2012 to 26.4 in 2016, then plateauing from 2016-2021).

Data are based on a sample of 4051 ED visits, representing about 18,238,000 average annual visits made by adults with diabetes to nonfederal, general, and short-stay hospitals during 2020-2021.

Taken together, these most recent estimates “show an increasing trend in rates by adults with diabetes in the ED setting,” the authors concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Emergency department (ED) visits by adults with diabetes increased by more than 25% since 2012, with the highest rates among Blacks and those aged over 65 years, a new data brief from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics shows.

In 2021, diabetes was the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the brief, published online on December 19, 2023. Its frequency is increasing in young people, and increasing age is a risk factor for hospitalization.

The latest data show that in 2020-2021, the overall annual ED visit rate was 72.2 visits per 1000 adults with diabetes, with no significant difference in terms of sex (75.1 visits per 1000 women vs 69.1 visits per 1000 men). By race/ethnicity, Blacks had the highest rates, at 135.5 visits per 1000 adults, followed by Whites (69.9) and Hispanics (52.3). The rates increased with age for both women and men, and among the three race/ethnic groups.

Comorbidities Count

The most ED visits were made by patients with diabetes and two to four other chronic conditions (541.4 visits per 1000 visits). Rates for patients without other chronic conditions were the lowest (90.2).

Among individuals with diabetes aged 18-44 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (402.0) and lowest among those with five or more other conditions (93.8).

Among patients aged 45-64 years, ED visit rates were the highest for those with two to four other chronic conditions (526.4) and lowest for those without other conditions (87.7). In the 65 years and older group, rates were the highest for individuals with two to four other chronic conditions (605.2), followed by five or more conditions (217.7), one other condition (140.6), and no other conditions (36.5).

Notably, the ED visit rates for those with two to four or five or more other chronic conditions increased with age, whereas visits for those with no other chronic conditions or one other condition decreased with age.

Decade-Long Trend

ED visit rates among adults with diabetes increased throughout the past decade, from 48.6 visits per 1000 adults in 2012 to 74.9 per 1000 adults in 2021. Rates for those aged 65 and older were higher than all other age groups, increasing from 113.4 to 156.8. Increases were also seen among those aged 45-64 years (53.1 in 2012 to 89.2 in 2021) and 18-44 (20.9 in 2012 to 26.4 in 2016, then plateauing from 2016-2021).

Data are based on a sample of 4051 ED visits, representing about 18,238,000 average annual visits made by adults with diabetes to nonfederal, general, and short-stay hospitals during 2020-2021.

Taken together, these most recent estimates “show an increasing trend in rates by adults with diabetes in the ED setting,” the authors concluded.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

GLP-1 RAs Associated With Reduced Colorectal Cancer Risk in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

according to a new analysis.

In particular, GLP-1 RAs were associated with decreased risk compared with other antidiabetic treatments, including insulin, metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones.

More profound effects were seen in patients with overweight or obesity, “suggesting a potential protective effect against CRC partially mediated by weight loss and other mechanisms related to weight loss,” Lindsey Wang, an undergraduate student at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Testing Treatments