User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Wanted: Better evidence on fast-track lung resection

A host of medical specialties have adopted strategies to speed recovery of surgical patients, reduce length of hospital stays, and cut costs, known as fast-track or enhanced-recovery pathways, but when it comes to elective lung resection, the medical evidence has yet to establish if patients in expedited recovery protocols fare any better than do those in a conventional recovery course, a systematic review in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery reported (2016 Mar;151:708-15).

A team of investigators from McGill University in Montreal performed a systematic review of six studies that evaluated patient outcomes of both traditional and enhanced-recovery pathways (ERPs) in elective lung resection. They concluded that ERPs may reduce the length of hospital stays and hospital costs but that well-designed trials are needed to overcome limitations of existing studies.

“The influence of ERPs on postoperative outcomes after lung resection has not been extensively studied in comparative studies involving a control group receiving traditional care,” lead author Julio F. Fiore Jr., Ph.D., and his colleagues said. One of the six studies they reviewed was a randomized clinical trial. The six studies involved a total of 1,612 participants (821 ERP, 791 control).

The researchers also reported that the studies they analyzed shared a significant limitation. “Risk of bias favoring enhanced-recovery pathways was high,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues wrote. The studies were unclear if patient selection may have factored into the results.

Five studies reported shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) for the ERP group. “The majority of the studies reported that LOS was significantly shorter when patients undergoing lung resection were treated within an ERP, which corroborates the results observed in other surgical populations,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues said.

Three nonrandomized studies also evaluated costs per patient. Two reported significantly lower costs for ERP patients: $13,093 vs. $14,439 for controls; and $13,432 vs. $17,103 for controls (Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006 Sep;54:387-90; Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998 Sep;66:914-9). The third showed what the authors said was no statistically significant cost differential between the two groups: $14,792 for ERP vs. $16,063 for controls (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997 Aug;64:299-302).

Three studies evaluated readmission rates, but only one showed measurably lower rates for the ERP group: 3% vs. 10% for controls (Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). Three studies measured complication rates in both groups. Two reported cardiopulmonary complication rates of 18% and 17% in the ERP group vs. 16% and 14% in the control group, respectively (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012 May;41:1083-7; Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). One reported rates of pulmonary complications of 7% for ERP vs. 36% for controls (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008 Jul;34:174-80).

Dr. Fiore and his colleagues pointed out that some of the studies they reviewed were completed before video-assisted thoracic surgery became routine for lung resection. But they acknowledged that research in other surgical specialties have validated the role of ERP, along with minimally invasive surgery, to improve outcomes. “Future research should investigate whether this holds true for patients undergoing lung resection,” they said.

The study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

The task that Dr. Fiore and colleagues undertook to evaluate and compare disparate studies of fast-track surgery in lung resection is “akin to comparing not just apples and oranges but apples to zucchini,” Dr. Lisa M. Brown of University of California, Davis, Medical Center said in her invited analysis (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Mar;151:715-16). Without the authors’ “descriptive approach,” Dr. Brown said, “the results of a true meta-analysis would be uninterpretable.”

|

Dr. Lisa M. Brown |

Nonetheless, the systematic review underscores the need for a blinded, randomized trial, Dr. Brown said. “Furthermore, rather than measuring [hospital] stay, subjects should be evaluated for readiness for discharge, because this would reduce the effect of systems-based obstacles to discharge,” she said. Enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs) in colorectal surgery have been used as models for other specialties, but the novelty of these pathways versus traditional care may be difficult to replicate in thoracic surgery, she said. Strategies such as antibiotic prophylaxis and epidural analgesia in thoracic surgery “are not dissimilar enough from standard care to elicit a difference in outcome,” she said.

In thoracic surgery, ERPs must consider the challenges of pain control and chest tube management unique in these patients, Dr. Brown said. For pain control, paravertebral blockade rather than epidural analgesia could lead to earlier hospital discharges. Use of chest tubes is commonly a matter of surgeon preference, she said, but chest tubes without an air leak and with acceptable fluid output can be safely removed, and even patients with an air leak but no pneumothorax on water seal can go home with a chest tube, Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no financial relationships to disclose.

The task that Dr. Fiore and colleagues undertook to evaluate and compare disparate studies of fast-track surgery in lung resection is “akin to comparing not just apples and oranges but apples to zucchini,” Dr. Lisa M. Brown of University of California, Davis, Medical Center said in her invited analysis (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Mar;151:715-16). Without the authors’ “descriptive approach,” Dr. Brown said, “the results of a true meta-analysis would be uninterpretable.”

|

Dr. Lisa M. Brown |

Nonetheless, the systematic review underscores the need for a blinded, randomized trial, Dr. Brown said. “Furthermore, rather than measuring [hospital] stay, subjects should be evaluated for readiness for discharge, because this would reduce the effect of systems-based obstacles to discharge,” she said. Enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs) in colorectal surgery have been used as models for other specialties, but the novelty of these pathways versus traditional care may be difficult to replicate in thoracic surgery, she said. Strategies such as antibiotic prophylaxis and epidural analgesia in thoracic surgery “are not dissimilar enough from standard care to elicit a difference in outcome,” she said.

In thoracic surgery, ERPs must consider the challenges of pain control and chest tube management unique in these patients, Dr. Brown said. For pain control, paravertebral blockade rather than epidural analgesia could lead to earlier hospital discharges. Use of chest tubes is commonly a matter of surgeon preference, she said, but chest tubes without an air leak and with acceptable fluid output can be safely removed, and even patients with an air leak but no pneumothorax on water seal can go home with a chest tube, Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no financial relationships to disclose.

The task that Dr. Fiore and colleagues undertook to evaluate and compare disparate studies of fast-track surgery in lung resection is “akin to comparing not just apples and oranges but apples to zucchini,” Dr. Lisa M. Brown of University of California, Davis, Medical Center said in her invited analysis (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016 Mar;151:715-16). Without the authors’ “descriptive approach,” Dr. Brown said, “the results of a true meta-analysis would be uninterpretable.”

|

Dr. Lisa M. Brown |

Nonetheless, the systematic review underscores the need for a blinded, randomized trial, Dr. Brown said. “Furthermore, rather than measuring [hospital] stay, subjects should be evaluated for readiness for discharge, because this would reduce the effect of systems-based obstacles to discharge,” she said. Enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs) in colorectal surgery have been used as models for other specialties, but the novelty of these pathways versus traditional care may be difficult to replicate in thoracic surgery, she said. Strategies such as antibiotic prophylaxis and epidural analgesia in thoracic surgery “are not dissimilar enough from standard care to elicit a difference in outcome,” she said.

In thoracic surgery, ERPs must consider the challenges of pain control and chest tube management unique in these patients, Dr. Brown said. For pain control, paravertebral blockade rather than epidural analgesia could lead to earlier hospital discharges. Use of chest tubes is commonly a matter of surgeon preference, she said, but chest tubes without an air leak and with acceptable fluid output can be safely removed, and even patients with an air leak but no pneumothorax on water seal can go home with a chest tube, Dr. Brown said.

Dr. Brown had no financial relationships to disclose.

A host of medical specialties have adopted strategies to speed recovery of surgical patients, reduce length of hospital stays, and cut costs, known as fast-track or enhanced-recovery pathways, but when it comes to elective lung resection, the medical evidence has yet to establish if patients in expedited recovery protocols fare any better than do those in a conventional recovery course, a systematic review in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery reported (2016 Mar;151:708-15).

A team of investigators from McGill University in Montreal performed a systematic review of six studies that evaluated patient outcomes of both traditional and enhanced-recovery pathways (ERPs) in elective lung resection. They concluded that ERPs may reduce the length of hospital stays and hospital costs but that well-designed trials are needed to overcome limitations of existing studies.

“The influence of ERPs on postoperative outcomes after lung resection has not been extensively studied in comparative studies involving a control group receiving traditional care,” lead author Julio F. Fiore Jr., Ph.D., and his colleagues said. One of the six studies they reviewed was a randomized clinical trial. The six studies involved a total of 1,612 participants (821 ERP, 791 control).

The researchers also reported that the studies they analyzed shared a significant limitation. “Risk of bias favoring enhanced-recovery pathways was high,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues wrote. The studies were unclear if patient selection may have factored into the results.

Five studies reported shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) for the ERP group. “The majority of the studies reported that LOS was significantly shorter when patients undergoing lung resection were treated within an ERP, which corroborates the results observed in other surgical populations,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues said.

Three nonrandomized studies also evaluated costs per patient. Two reported significantly lower costs for ERP patients: $13,093 vs. $14,439 for controls; and $13,432 vs. $17,103 for controls (Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006 Sep;54:387-90; Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998 Sep;66:914-9). The third showed what the authors said was no statistically significant cost differential between the two groups: $14,792 for ERP vs. $16,063 for controls (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997 Aug;64:299-302).

Three studies evaluated readmission rates, but only one showed measurably lower rates for the ERP group: 3% vs. 10% for controls (Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). Three studies measured complication rates in both groups. Two reported cardiopulmonary complication rates of 18% and 17% in the ERP group vs. 16% and 14% in the control group, respectively (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012 May;41:1083-7; Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). One reported rates of pulmonary complications of 7% for ERP vs. 36% for controls (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008 Jul;34:174-80).

Dr. Fiore and his colleagues pointed out that some of the studies they reviewed were completed before video-assisted thoracic surgery became routine for lung resection. But they acknowledged that research in other surgical specialties have validated the role of ERP, along with minimally invasive surgery, to improve outcomes. “Future research should investigate whether this holds true for patients undergoing lung resection,” they said.

The study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

A host of medical specialties have adopted strategies to speed recovery of surgical patients, reduce length of hospital stays, and cut costs, known as fast-track or enhanced-recovery pathways, but when it comes to elective lung resection, the medical evidence has yet to establish if patients in expedited recovery protocols fare any better than do those in a conventional recovery course, a systematic review in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery reported (2016 Mar;151:708-15).

A team of investigators from McGill University in Montreal performed a systematic review of six studies that evaluated patient outcomes of both traditional and enhanced-recovery pathways (ERPs) in elective lung resection. They concluded that ERPs may reduce the length of hospital stays and hospital costs but that well-designed trials are needed to overcome limitations of existing studies.

“The influence of ERPs on postoperative outcomes after lung resection has not been extensively studied in comparative studies involving a control group receiving traditional care,” lead author Julio F. Fiore Jr., Ph.D., and his colleagues said. One of the six studies they reviewed was a randomized clinical trial. The six studies involved a total of 1,612 participants (821 ERP, 791 control).

The researchers also reported that the studies they analyzed shared a significant limitation. “Risk of bias favoring enhanced-recovery pathways was high,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues wrote. The studies were unclear if patient selection may have factored into the results.

Five studies reported shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) for the ERP group. “The majority of the studies reported that LOS was significantly shorter when patients undergoing lung resection were treated within an ERP, which corroborates the results observed in other surgical populations,” Dr. Fiore and his colleagues said.

Three nonrandomized studies also evaluated costs per patient. Two reported significantly lower costs for ERP patients: $13,093 vs. $14,439 for controls; and $13,432 vs. $17,103 for controls (Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006 Sep;54:387-90; Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1998 Sep;66:914-9). The third showed what the authors said was no statistically significant cost differential between the two groups: $14,792 for ERP vs. $16,063 for controls (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997 Aug;64:299-302).

Three studies evaluated readmission rates, but only one showed measurably lower rates for the ERP group: 3% vs. 10% for controls (Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). Three studies measured complication rates in both groups. Two reported cardiopulmonary complication rates of 18% and 17% in the ERP group vs. 16% and 14% in the control group, respectively (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012 May;41:1083-7; Lung Cancer. 2012 Dec;78:270-5). One reported rates of pulmonary complications of 7% for ERP vs. 36% for controls (Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008 Jul;34:174-80).

Dr. Fiore and his colleagues pointed out that some of the studies they reviewed were completed before video-assisted thoracic surgery became routine for lung resection. But they acknowledged that research in other surgical specialties have validated the role of ERP, along with minimally invasive surgery, to improve outcomes. “Future research should investigate whether this holds true for patients undergoing lung resection,” they said.

The study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Key clinical point: Well-designed clinical trials are needed to determine the effectiveness of fast-track recovery pathways in lung resection.

Major finding: Fast-track lung resection patients showed no differences in readmissions, overall complication and death rates compared to patients subjected to a traditional recovery course.

Data source: Systematic review of six studies published from 1997 to 2012 that involved 1,612 individuals who had lung resection.

Disclosures: The study authors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Sutureless AVR an option for higher-risk patients

The first North American experience with a sutureless bioprosthetic aortic valve that has been available in Europe since 2005 and is well suited for minimally invasive surgery has underscored the utility of the device as an alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement (AVR) in higher-risk patients, investigators from McGill University Health Center in Montreal reported in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:735-742).

The investigators, led by Dr. Benoir de Varennes, reported on their experience implanting the Enable valve (Medtronic, Minneapolis) in 63 patients between August 2012 and October 2014. “The enable bioprosthesis is an acceptable alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement in higher-risk patients,” Dr. de Varennes and colleagues said. “The early hemodynamic performance seems favorable.” Their findings were first presented at the 95th annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery in April 2015 in Seattle. A video of the presentation is available.

The Enable valve has been the subject of four European studies with 429 patients. It received its CE Mark in Europe in 2009, but is not yet commercially approved in the United States.

In the McGill study, one patient died within 30 days of receiving the valve and two died after 30 days, but none of the deaths were valve related. Four patients (6.3%) required revision during the implantation operation, and one patient required reoperation for early migration. Peak and mean gradients after surgery were 17 mm Hg and 9 mm Hg, respectively. Three patients had reported complications: Two (3.1%) required a pacemaker and one (1.6%) had a heart attack. Mean follow-up was 10 months.

Patient ages ranged from 57 to 89 years, with an average age of 80. Before surgery, all patients had calcific aortic stenosis, 43 (68%) had some degree of associated aortic regurgitation, and 46 (73%) were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV. At the last follow-up after surgery, 61 patients (97%) were in NYHA class I.

The investigators implanted the valve through a full sternotomy or a partial upper sternotomy into the fourth intercostal space, and they used perioperative transesophageal echocardiography in all patients. They performed high-transverse aortotomy and completely excised the native valve.

The average cross-clamp time for the 30 patients who had isolated AVR was 44 minutes and 77 minutes for the 33 patients who had combined procedures. Dr. de Varennes and colleagues acknowledged the cross-clamp time for isolated AVR is “similar” to European series but “not very different” from recent reports on sutured AVR (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;149:451-460). “This may be explained partly by the learning period of all three surgeons and the aggressive debridement of the annulus in all cases,” they said. “We think that, as further experience is gained, the clamp time will be further reduced, and this will benefit mostly higher-risk patients or those requiring concomitant procedures.”

They noted that some patients received the Enable prosthesis because of “hostile” aortas with extensive root calcification.

Dr. de Varennes disclosed he is a consultant for Medtronic and a proctor for Enable training. The coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

One of the key advantages that advocates of sutureless valves point to is shorter bypass times than sutured valves, but in his invited commentary Dr. Thomas G. Gleason of the University of Pittsburgh questioned this rationale based on the results Dr. de Varennes and colleagues reported (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;151:743-744). The cardiac bypass times they observed “are not appreciably different from those reported in larger series of conventional aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason suggested that “market forces” might be driving the push into sutureless aortic valve replacement. “The attraction, particularly to consumers, of the ministernotomy (and thus things that might facilitate it) is both cosmetic and the perception that it is less invasive,” he said. “These attractions notwithstanding, it has been difficult to demonstrate that ministernotomy or minithoracotomy yield better primary outcomes (e.g., mortality, stroke, or major complication rates) or even quality of life indicators, particularly when measured beyond the perioperative period.”

|

Dr. Thomas G. Gleason |

He alluded to the “elephant in the room” with regard to sutureless aortic valve technologies: their cost and unknown durability compared with conventional sutured bioprostheses.

“As health care costs continue to rise and large populations of patients are either underinsured or see rationed care, trimming direct costs may be a more relevant concern for the modern era than trimming cross-clamp time,” he said. Analyses have not yet evaluated the increased costs of sutureless valves in terms of shortened hospital stays or lower morbidity, particularly in the moderate-risk population with aortic stenosis, he said.

“Moving forward, there is little doubt that the current value of the sutureless valve will be dictated by the market, but in the end it will be measured by the long-term outcomes of the ‘minimally invaded,’” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason had no financial relationships to disclose.

One of the key advantages that advocates of sutureless valves point to is shorter bypass times than sutured valves, but in his invited commentary Dr. Thomas G. Gleason of the University of Pittsburgh questioned this rationale based on the results Dr. de Varennes and colleagues reported (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;151:743-744). The cardiac bypass times they observed “are not appreciably different from those reported in larger series of conventional aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason suggested that “market forces” might be driving the push into sutureless aortic valve replacement. “The attraction, particularly to consumers, of the ministernotomy (and thus things that might facilitate it) is both cosmetic and the perception that it is less invasive,” he said. “These attractions notwithstanding, it has been difficult to demonstrate that ministernotomy or minithoracotomy yield better primary outcomes (e.g., mortality, stroke, or major complication rates) or even quality of life indicators, particularly when measured beyond the perioperative period.”

|

Dr. Thomas G. Gleason |

He alluded to the “elephant in the room” with regard to sutureless aortic valve technologies: their cost and unknown durability compared with conventional sutured bioprostheses.

“As health care costs continue to rise and large populations of patients are either underinsured or see rationed care, trimming direct costs may be a more relevant concern for the modern era than trimming cross-clamp time,” he said. Analyses have not yet evaluated the increased costs of sutureless valves in terms of shortened hospital stays or lower morbidity, particularly in the moderate-risk population with aortic stenosis, he said.

“Moving forward, there is little doubt that the current value of the sutureless valve will be dictated by the market, but in the end it will be measured by the long-term outcomes of the ‘minimally invaded,’” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason had no financial relationships to disclose.

One of the key advantages that advocates of sutureless valves point to is shorter bypass times than sutured valves, but in his invited commentary Dr. Thomas G. Gleason of the University of Pittsburgh questioned this rationale based on the results Dr. de Varennes and colleagues reported (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016;151:743-744). The cardiac bypass times they observed “are not appreciably different from those reported in larger series of conventional aortic valve replacement,” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason suggested that “market forces” might be driving the push into sutureless aortic valve replacement. “The attraction, particularly to consumers, of the ministernotomy (and thus things that might facilitate it) is both cosmetic and the perception that it is less invasive,” he said. “These attractions notwithstanding, it has been difficult to demonstrate that ministernotomy or minithoracotomy yield better primary outcomes (e.g., mortality, stroke, or major complication rates) or even quality of life indicators, particularly when measured beyond the perioperative period.”

|

Dr. Thomas G. Gleason |

He alluded to the “elephant in the room” with regard to sutureless aortic valve technologies: their cost and unknown durability compared with conventional sutured bioprostheses.

“As health care costs continue to rise and large populations of patients are either underinsured or see rationed care, trimming direct costs may be a more relevant concern for the modern era than trimming cross-clamp time,” he said. Analyses have not yet evaluated the increased costs of sutureless valves in terms of shortened hospital stays or lower morbidity, particularly in the moderate-risk population with aortic stenosis, he said.

“Moving forward, there is little doubt that the current value of the sutureless valve will be dictated by the market, but in the end it will be measured by the long-term outcomes of the ‘minimally invaded,’” Dr. Gleason said.

Dr. Gleason had no financial relationships to disclose.

The first North American experience with a sutureless bioprosthetic aortic valve that has been available in Europe since 2005 and is well suited for minimally invasive surgery has underscored the utility of the device as an alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement (AVR) in higher-risk patients, investigators from McGill University Health Center in Montreal reported in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:735-742).

The investigators, led by Dr. Benoir de Varennes, reported on their experience implanting the Enable valve (Medtronic, Minneapolis) in 63 patients between August 2012 and October 2014. “The enable bioprosthesis is an acceptable alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement in higher-risk patients,” Dr. de Varennes and colleagues said. “The early hemodynamic performance seems favorable.” Their findings were first presented at the 95th annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery in April 2015 in Seattle. A video of the presentation is available.

The Enable valve has been the subject of four European studies with 429 patients. It received its CE Mark in Europe in 2009, but is not yet commercially approved in the United States.

In the McGill study, one patient died within 30 days of receiving the valve and two died after 30 days, but none of the deaths were valve related. Four patients (6.3%) required revision during the implantation operation, and one patient required reoperation for early migration. Peak and mean gradients after surgery were 17 mm Hg and 9 mm Hg, respectively. Three patients had reported complications: Two (3.1%) required a pacemaker and one (1.6%) had a heart attack. Mean follow-up was 10 months.

Patient ages ranged from 57 to 89 years, with an average age of 80. Before surgery, all patients had calcific aortic stenosis, 43 (68%) had some degree of associated aortic regurgitation, and 46 (73%) were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV. At the last follow-up after surgery, 61 patients (97%) were in NYHA class I.

The investigators implanted the valve through a full sternotomy or a partial upper sternotomy into the fourth intercostal space, and they used perioperative transesophageal echocardiography in all patients. They performed high-transverse aortotomy and completely excised the native valve.

The average cross-clamp time for the 30 patients who had isolated AVR was 44 minutes and 77 minutes for the 33 patients who had combined procedures. Dr. de Varennes and colleagues acknowledged the cross-clamp time for isolated AVR is “similar” to European series but “not very different” from recent reports on sutured AVR (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;149:451-460). “This may be explained partly by the learning period of all three surgeons and the aggressive debridement of the annulus in all cases,” they said. “We think that, as further experience is gained, the clamp time will be further reduced, and this will benefit mostly higher-risk patients or those requiring concomitant procedures.”

They noted that some patients received the Enable prosthesis because of “hostile” aortas with extensive root calcification.

Dr. de Varennes disclosed he is a consultant for Medtronic and a proctor for Enable training. The coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

The first North American experience with a sutureless bioprosthetic aortic valve that has been available in Europe since 2005 and is well suited for minimally invasive surgery has underscored the utility of the device as an alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement (AVR) in higher-risk patients, investigators from McGill University Health Center in Montreal reported in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;151:735-742).

The investigators, led by Dr. Benoir de Varennes, reported on their experience implanting the Enable valve (Medtronic, Minneapolis) in 63 patients between August 2012 and October 2014. “The enable bioprosthesis is an acceptable alternative to conventional aortic valve replacement in higher-risk patients,” Dr. de Varennes and colleagues said. “The early hemodynamic performance seems favorable.” Their findings were first presented at the 95th annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery in April 2015 in Seattle. A video of the presentation is available.

The Enable valve has been the subject of four European studies with 429 patients. It received its CE Mark in Europe in 2009, but is not yet commercially approved in the United States.

In the McGill study, one patient died within 30 days of receiving the valve and two died after 30 days, but none of the deaths were valve related. Four patients (6.3%) required revision during the implantation operation, and one patient required reoperation for early migration. Peak and mean gradients after surgery were 17 mm Hg and 9 mm Hg, respectively. Three patients had reported complications: Two (3.1%) required a pacemaker and one (1.6%) had a heart attack. Mean follow-up was 10 months.

Patient ages ranged from 57 to 89 years, with an average age of 80. Before surgery, all patients had calcific aortic stenosis, 43 (68%) had some degree of associated aortic regurgitation, and 46 (73%) were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV. At the last follow-up after surgery, 61 patients (97%) were in NYHA class I.

The investigators implanted the valve through a full sternotomy or a partial upper sternotomy into the fourth intercostal space, and they used perioperative transesophageal echocardiography in all patients. They performed high-transverse aortotomy and completely excised the native valve.

The average cross-clamp time for the 30 patients who had isolated AVR was 44 minutes and 77 minutes for the 33 patients who had combined procedures. Dr. de Varennes and colleagues acknowledged the cross-clamp time for isolated AVR is “similar” to European series but “not very different” from recent reports on sutured AVR (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;149:451-460). “This may be explained partly by the learning period of all three surgeons and the aggressive debridement of the annulus in all cases,” they said. “We think that, as further experience is gained, the clamp time will be further reduced, and this will benefit mostly higher-risk patients or those requiring concomitant procedures.”

They noted that some patients received the Enable prosthesis because of “hostile” aortas with extensive root calcification.

Dr. de Varennes disclosed he is a consultant for Medtronic and a proctor for Enable training. The coauthors had no relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Sutureless aortic valves have the potential to achieve shorter procedure times and benefit increased-risk patients with aortic stenosis.

Major finding: Thirty-day mortality of patients who received the Enable aortic valve was 1.6%, and late mortality was 3.2%. No deaths were valve related.

Data source: Sixty-three patients with aortic stenosis who had Enable bioprosthetic valve implantation between August 2012 and October 2014 at McGill University Health Center.

Disclosures: Lead author Dr. Benoit de Varennes is a consultant for Medtronic and a trainer for the Enable device. The other authors had no relationships to disclose.

Endometrial cancer: Lymphovascular space invasion boosts risk of nodal metastases

SAN DIEGO – The presence of lymphovascular space invasion in the setting of early-stage endometrial cancer is a more potent independent predictor of associated pelvic lymph node metastases than previously recognized, Dr. Soledad Jorge reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Indeed, she found in her large, population-based study that lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) was the strongest predictor of nodal disease, even more robust than tumor grade. LVSI also was associated with a 1.92-fold increased risk of mortality at 45 months’ follow-up after adjustment for the presence of lymph node metastases.

This was a study of 25,907 women with surgically staged endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium who underwent hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy during 2010-2012 and were registered in the National Cancer Data Base. Seventy-two percent of them had T1A disease, defined by less than 50% myometrial invasion, while the remaining 28% had T1B disease with greater than 50% myoinvasion, according to Dr. Jorge of Columbia University in New York.

LVSI was present in 15.2% of the women. Lymph node metastases were detected in 5% of the overall study population. Twenty-one percent of women with LVSI had positive pelvic lymph nodes, compared with just 2.1% of patients without LVSI, she said.

When patients were stratified by tumor depth and invasion, LVSI was independently associated with a 3- to 16-fold increased risk of nodal metastases. In a more comprehensive multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, tumor stage and grade, and other demographic and clinical factors, the relative risk of lymph node metastases in patients with T1A disease and LVSI was increased 9.2-fold, compared with that of patients with no LVSI. Patients with T1B disease and LVSI were at 4.6-fold greater risk for lymph node metastases than were T1B patients without LVSI, Dr. Jorge said.

LVSI was associated with significantly reduced survival out to 45 months in all patient subgroups except those having Stage IA, grade 1 tumors.

Dr. Jorge reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – The presence of lymphovascular space invasion in the setting of early-stage endometrial cancer is a more potent independent predictor of associated pelvic lymph node metastases than previously recognized, Dr. Soledad Jorge reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Indeed, she found in her large, population-based study that lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) was the strongest predictor of nodal disease, even more robust than tumor grade. LVSI also was associated with a 1.92-fold increased risk of mortality at 45 months’ follow-up after adjustment for the presence of lymph node metastases.

This was a study of 25,907 women with surgically staged endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium who underwent hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy during 2010-2012 and were registered in the National Cancer Data Base. Seventy-two percent of them had T1A disease, defined by less than 50% myometrial invasion, while the remaining 28% had T1B disease with greater than 50% myoinvasion, according to Dr. Jorge of Columbia University in New York.

LVSI was present in 15.2% of the women. Lymph node metastases were detected in 5% of the overall study population. Twenty-one percent of women with LVSI had positive pelvic lymph nodes, compared with just 2.1% of patients without LVSI, she said.

When patients were stratified by tumor depth and invasion, LVSI was independently associated with a 3- to 16-fold increased risk of nodal metastases. In a more comprehensive multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, tumor stage and grade, and other demographic and clinical factors, the relative risk of lymph node metastases in patients with T1A disease and LVSI was increased 9.2-fold, compared with that of patients with no LVSI. Patients with T1B disease and LVSI were at 4.6-fold greater risk for lymph node metastases than were T1B patients without LVSI, Dr. Jorge said.

LVSI was associated with significantly reduced survival out to 45 months in all patient subgroups except those having Stage IA, grade 1 tumors.

Dr. Jorge reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – The presence of lymphovascular space invasion in the setting of early-stage endometrial cancer is a more potent independent predictor of associated pelvic lymph node metastases than previously recognized, Dr. Soledad Jorge reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Indeed, she found in her large, population-based study that lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) was the strongest predictor of nodal disease, even more robust than tumor grade. LVSI also was associated with a 1.92-fold increased risk of mortality at 45 months’ follow-up after adjustment for the presence of lymph node metastases.

This was a study of 25,907 women with surgically staged endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium who underwent hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy during 2010-2012 and were registered in the National Cancer Data Base. Seventy-two percent of them had T1A disease, defined by less than 50% myometrial invasion, while the remaining 28% had T1B disease with greater than 50% myoinvasion, according to Dr. Jorge of Columbia University in New York.

LVSI was present in 15.2% of the women. Lymph node metastases were detected in 5% of the overall study population. Twenty-one percent of women with LVSI had positive pelvic lymph nodes, compared with just 2.1% of patients without LVSI, she said.

When patients were stratified by tumor depth and invasion, LVSI was independently associated with a 3- to 16-fold increased risk of nodal metastases. In a more comprehensive multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, tumor stage and grade, and other demographic and clinical factors, the relative risk of lymph node metastases in patients with T1A disease and LVSI was increased 9.2-fold, compared with that of patients with no LVSI. Patients with T1B disease and LVSI were at 4.6-fold greater risk for lymph node metastases than were T1B patients without LVSI, Dr. Jorge said.

LVSI was associated with significantly reduced survival out to 45 months in all patient subgroups except those having Stage IA, grade 1 tumors.

Dr. Jorge reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: The prevalence of lymph node metastases in early-stage endometrial cancer patients with lymphovascular space invasion was 10-fold greater than in patients without lymphovascular space invasion.

Major finding: The risk of mortality during 45 months of follow-up was roughly twice as great in patients with lymphovascular space invasion than in those without, independent of the presence or absence of nodal metastases.

Data source: This was a population-based study of nearly 26,000 women with early-stage endometrial cancer included in the National Cancer Data Base.

Disclosures: Dr. Jorge reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Debulking advanced ovarian cancer to low volume linked with better survival

SAN DIEGO – There is a survival benefit to debulking stage IIIC ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal tumors down to 10mm or smaller in size, a single-center retrospective study demonstrated.

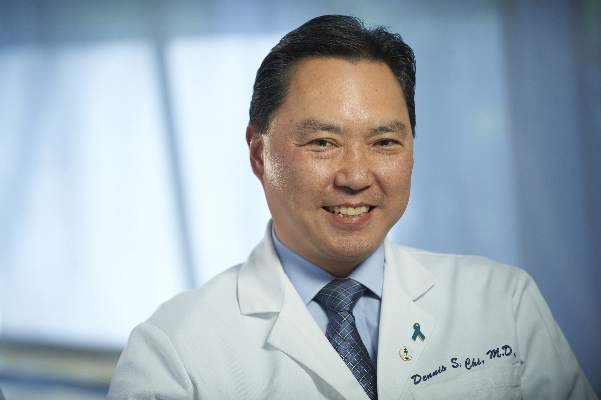

“You shouldn’t just relegate those patients [in whom] you can’t get a complete gross resection to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, because their median survival is going to generally be around 30-36 months,” Dr. Dennis S. Chi said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “But if you do a primary debulking and you get the volume of residual disease down to 10 mm or smaller in maximal diameter, the median survivals can be in the mid-40s to over 80 months.”

Dr. Chi, head of ovarian cancer surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said that the current findings come at a time when the initial management of advanced ovarian cancer is in flux and is controversial. “For decades it used to be that the initial step was to do an operation and to do a primary debulking surgery,” he said. “But studies in the 1980s and 1990s showed that if you did primary debulking surgery and you did the standard surgery that gynecologic oncologists did at that time, greater than 50% of the time you would not do an operation that would result in an optimal debulking, where you get all or almost all of the visible cancer out.”

Two camps formed, he continued, one consisting of clinicians who believe “we need to do better surgery, or more comprehensive surgery,” and another group of clinicians who say, “Why don’t we treat with chemotherapy first for three treatments, and then do surgery? Maybe this will shrink the cancer and consequently improve the surgical outcome.’ Both camps agree that if you cannot get all the cancer out or almost all the cancer out, then you should start with chemotherapy first. The question then lies, what is the cut-off?”

In a study led by Dr. Chi and Dr. Vasileios Sioulas, the Senior International Gynecologic Oncology Fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the authors set out to explore the effect of primary cytoreduction to minimal but gross residual disease in women with bulky stage IIIC ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer. They retrospectively evaluated the records of 496 women who underwent primary debulking surgery at the cancer center between 2001 and 2010. Their median age was 62 years, the median operative time was 265 minutes, and 46% of the patients received at least one cycle of primary or consolidation intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

The researchers assigned patients to one of four groups based on reported gross residual disease. More than one-third (37%) had no gross residual disease (group 1); 26% had residual disease of 1-5 mm in diameter (group 2); 11% had residual disease of 6-10 mm in diameter (group 3), and 26% had residual disease that exceeded 10 mm in diameter (group 4). The median follow-up in the entire cohort was 53 months, the median progression-free survival was 18.6 months, and the median overall survival was 54.7 months. However, median progression-free survival and median overall survival varied significantly among the four assigned groups. It was 26.7 months for group 1, 20.7 months for group 2, 16.2 months for group 3, and 13.6 months for group 4 (P less than .001). At the same time, median overall survival was 83.4 months for group 1, 54.5 months for 2, 43.8 months for group 3, and 38.9 months for group 4 (P less than .001).

To be consistent with the vast majority of the existing literature, which used the cut-off of 10 mm to define optimal residual disease, Dr. Sioulas and his associates merged patients with residual disease 1-5 mm and 6-10 mm into one group and found that its median overall survival was 52.6 months. Patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm had significantly better overall survival, as compared to those with residual disease greater than 10 mm (P less than .001). Importantly, among the patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm, the administration of at least one cycle of primary intraperitoneal chemotherapy was associated with significantly prolonged overall survival, as compared to the sole use of intravenous chemotherapy. The median overall survival for those groups was 65.1 and 40.6 months, respectively (P = .002).

“I certainly believe neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the best approach in certain situations, but I don’t think it should be the knee-jerk reflex for all patients with advanced ovarian cancer,” Dr. Chi said. “I think that may be doing a disservice to many patients who could get a distinct prolongation of life and overall survival, or even cure, with a primary debulking surgery approach.”

He noted that ovarian cancer “goes where it wants to go. It doesn’t care what the training or surgical capabilities of the surgeon are. It’s going to go where it wants to go, so you can’t make the patient and the disease fit into your training skill set. You have to adapt your training skill set to the disease.”

The ideal study of this issue, Dr. Chi said, would “compare 400 or 500 patients with primary debulking and 400 or 500 patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy to see which approach is better. There are two trials that have been done in Europe and have shown that it doesn’t matter, that the outcomes are the same whether you do primary debulking first or neoadjuvant chemotherapy first [see N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363;943-53 and Lancet 2015;386:249-57]. Unfortunately, the survival outcomes in their primary debulking surgery arm were much lower as compared to other studies, especially those conducted in the United States. This highlights the importance of homogeneity in advanced surgical skills as a prerequisite before we draw definite conclusions about the survival outcomes after primary debulking surgery in patients with advanced disease.”

Dr. Chi acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the fact that surgeons at Memorial Sloan Kettering “are more willing, and have more support staff available, to perform comprehensive surgeries than at other centers.”

SAN DIEGO – There is a survival benefit to debulking stage IIIC ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal tumors down to 10mm or smaller in size, a single-center retrospective study demonstrated.

“You shouldn’t just relegate those patients [in whom] you can’t get a complete gross resection to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, because their median survival is going to generally be around 30-36 months,” Dr. Dennis S. Chi said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “But if you do a primary debulking and you get the volume of residual disease down to 10 mm or smaller in maximal diameter, the median survivals can be in the mid-40s to over 80 months.”

Dr. Chi, head of ovarian cancer surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said that the current findings come at a time when the initial management of advanced ovarian cancer is in flux and is controversial. “For decades it used to be that the initial step was to do an operation and to do a primary debulking surgery,” he said. “But studies in the 1980s and 1990s showed that if you did primary debulking surgery and you did the standard surgery that gynecologic oncologists did at that time, greater than 50% of the time you would not do an operation that would result in an optimal debulking, where you get all or almost all of the visible cancer out.”

Two camps formed, he continued, one consisting of clinicians who believe “we need to do better surgery, or more comprehensive surgery,” and another group of clinicians who say, “Why don’t we treat with chemotherapy first for three treatments, and then do surgery? Maybe this will shrink the cancer and consequently improve the surgical outcome.’ Both camps agree that if you cannot get all the cancer out or almost all the cancer out, then you should start with chemotherapy first. The question then lies, what is the cut-off?”

In a study led by Dr. Chi and Dr. Vasileios Sioulas, the Senior International Gynecologic Oncology Fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the authors set out to explore the effect of primary cytoreduction to minimal but gross residual disease in women with bulky stage IIIC ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer. They retrospectively evaluated the records of 496 women who underwent primary debulking surgery at the cancer center between 2001 and 2010. Their median age was 62 years, the median operative time was 265 minutes, and 46% of the patients received at least one cycle of primary or consolidation intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

The researchers assigned patients to one of four groups based on reported gross residual disease. More than one-third (37%) had no gross residual disease (group 1); 26% had residual disease of 1-5 mm in diameter (group 2); 11% had residual disease of 6-10 mm in diameter (group 3), and 26% had residual disease that exceeded 10 mm in diameter (group 4). The median follow-up in the entire cohort was 53 months, the median progression-free survival was 18.6 months, and the median overall survival was 54.7 months. However, median progression-free survival and median overall survival varied significantly among the four assigned groups. It was 26.7 months for group 1, 20.7 months for group 2, 16.2 months for group 3, and 13.6 months for group 4 (P less than .001). At the same time, median overall survival was 83.4 months for group 1, 54.5 months for 2, 43.8 months for group 3, and 38.9 months for group 4 (P less than .001).

To be consistent with the vast majority of the existing literature, which used the cut-off of 10 mm to define optimal residual disease, Dr. Sioulas and his associates merged patients with residual disease 1-5 mm and 6-10 mm into one group and found that its median overall survival was 52.6 months. Patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm had significantly better overall survival, as compared to those with residual disease greater than 10 mm (P less than .001). Importantly, among the patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm, the administration of at least one cycle of primary intraperitoneal chemotherapy was associated with significantly prolonged overall survival, as compared to the sole use of intravenous chemotherapy. The median overall survival for those groups was 65.1 and 40.6 months, respectively (P = .002).

“I certainly believe neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the best approach in certain situations, but I don’t think it should be the knee-jerk reflex for all patients with advanced ovarian cancer,” Dr. Chi said. “I think that may be doing a disservice to many patients who could get a distinct prolongation of life and overall survival, or even cure, with a primary debulking surgery approach.”

He noted that ovarian cancer “goes where it wants to go. It doesn’t care what the training or surgical capabilities of the surgeon are. It’s going to go where it wants to go, so you can’t make the patient and the disease fit into your training skill set. You have to adapt your training skill set to the disease.”

The ideal study of this issue, Dr. Chi said, would “compare 400 or 500 patients with primary debulking and 400 or 500 patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy to see which approach is better. There are two trials that have been done in Europe and have shown that it doesn’t matter, that the outcomes are the same whether you do primary debulking first or neoadjuvant chemotherapy first [see N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363;943-53 and Lancet 2015;386:249-57]. Unfortunately, the survival outcomes in their primary debulking surgery arm were much lower as compared to other studies, especially those conducted in the United States. This highlights the importance of homogeneity in advanced surgical skills as a prerequisite before we draw definite conclusions about the survival outcomes after primary debulking surgery in patients with advanced disease.”

Dr. Chi acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the fact that surgeons at Memorial Sloan Kettering “are more willing, and have more support staff available, to perform comprehensive surgeries than at other centers.”

SAN DIEGO – There is a survival benefit to debulking stage IIIC ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal tumors down to 10mm or smaller in size, a single-center retrospective study demonstrated.

“You shouldn’t just relegate those patients [in whom] you can’t get a complete gross resection to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, because their median survival is going to generally be around 30-36 months,” Dr. Dennis S. Chi said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of Society of Gynecologic Oncology. “But if you do a primary debulking and you get the volume of residual disease down to 10 mm or smaller in maximal diameter, the median survivals can be in the mid-40s to over 80 months.”

Dr. Chi, head of ovarian cancer surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said that the current findings come at a time when the initial management of advanced ovarian cancer is in flux and is controversial. “For decades it used to be that the initial step was to do an operation and to do a primary debulking surgery,” he said. “But studies in the 1980s and 1990s showed that if you did primary debulking surgery and you did the standard surgery that gynecologic oncologists did at that time, greater than 50% of the time you would not do an operation that would result in an optimal debulking, where you get all or almost all of the visible cancer out.”

Two camps formed, he continued, one consisting of clinicians who believe “we need to do better surgery, or more comprehensive surgery,” and another group of clinicians who say, “Why don’t we treat with chemotherapy first for three treatments, and then do surgery? Maybe this will shrink the cancer and consequently improve the surgical outcome.’ Both camps agree that if you cannot get all the cancer out or almost all the cancer out, then you should start with chemotherapy first. The question then lies, what is the cut-off?”

In a study led by Dr. Chi and Dr. Vasileios Sioulas, the Senior International Gynecologic Oncology Fellow at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the authors set out to explore the effect of primary cytoreduction to minimal but gross residual disease in women with bulky stage IIIC ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer. They retrospectively evaluated the records of 496 women who underwent primary debulking surgery at the cancer center between 2001 and 2010. Their median age was 62 years, the median operative time was 265 minutes, and 46% of the patients received at least one cycle of primary or consolidation intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

The researchers assigned patients to one of four groups based on reported gross residual disease. More than one-third (37%) had no gross residual disease (group 1); 26% had residual disease of 1-5 mm in diameter (group 2); 11% had residual disease of 6-10 mm in diameter (group 3), and 26% had residual disease that exceeded 10 mm in diameter (group 4). The median follow-up in the entire cohort was 53 months, the median progression-free survival was 18.6 months, and the median overall survival was 54.7 months. However, median progression-free survival and median overall survival varied significantly among the four assigned groups. It was 26.7 months for group 1, 20.7 months for group 2, 16.2 months for group 3, and 13.6 months for group 4 (P less than .001). At the same time, median overall survival was 83.4 months for group 1, 54.5 months for 2, 43.8 months for group 3, and 38.9 months for group 4 (P less than .001).

To be consistent with the vast majority of the existing literature, which used the cut-off of 10 mm to define optimal residual disease, Dr. Sioulas and his associates merged patients with residual disease 1-5 mm and 6-10 mm into one group and found that its median overall survival was 52.6 months. Patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm had significantly better overall survival, as compared to those with residual disease greater than 10 mm (P less than .001). Importantly, among the patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm, the administration of at least one cycle of primary intraperitoneal chemotherapy was associated with significantly prolonged overall survival, as compared to the sole use of intravenous chemotherapy. The median overall survival for those groups was 65.1 and 40.6 months, respectively (P = .002).

“I certainly believe neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the best approach in certain situations, but I don’t think it should be the knee-jerk reflex for all patients with advanced ovarian cancer,” Dr. Chi said. “I think that may be doing a disservice to many patients who could get a distinct prolongation of life and overall survival, or even cure, with a primary debulking surgery approach.”

He noted that ovarian cancer “goes where it wants to go. It doesn’t care what the training or surgical capabilities of the surgeon are. It’s going to go where it wants to go, so you can’t make the patient and the disease fit into your training skill set. You have to adapt your training skill set to the disease.”

The ideal study of this issue, Dr. Chi said, would “compare 400 or 500 patients with primary debulking and 400 or 500 patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy to see which approach is better. There are two trials that have been done in Europe and have shown that it doesn’t matter, that the outcomes are the same whether you do primary debulking first or neoadjuvant chemotherapy first [see N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363;943-53 and Lancet 2015;386:249-57]. Unfortunately, the survival outcomes in their primary debulking surgery arm were much lower as compared to other studies, especially those conducted in the United States. This highlights the importance of homogeneity in advanced surgical skills as a prerequisite before we draw definite conclusions about the survival outcomes after primary debulking surgery in patients with advanced disease.”

Dr. Chi acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the fact that surgeons at Memorial Sloan Kettering “are more willing, and have more support staff available, to perform comprehensive surgeries than at other centers.”

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: A survival benefit was seen after debulking stage III ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal tumors down to 10 mm or smaller in diameter.

Major finding: Patients with residual disease of 1-10 mm had significantly better overall survival, as compared to those with residual disease greater than 10 mm (P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective evaluation of 496 women who underwent primary debulking surgery at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 2001 and 2010.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Match Day 2016: Residency spots rise, but growth still needed

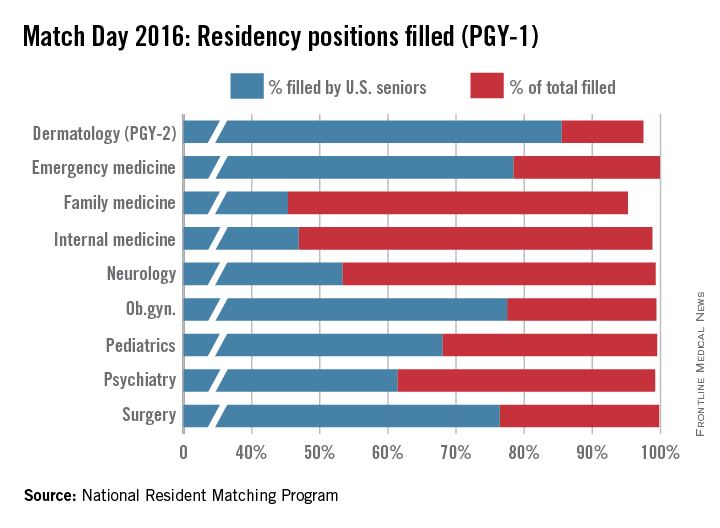

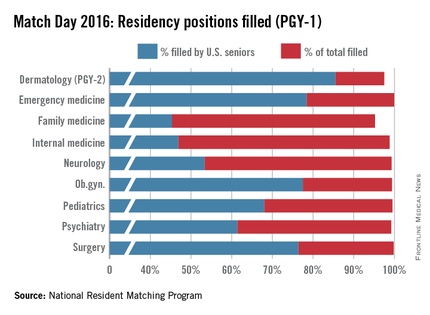

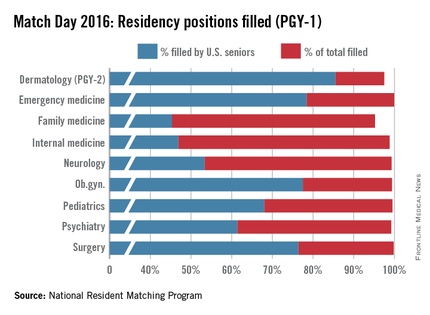

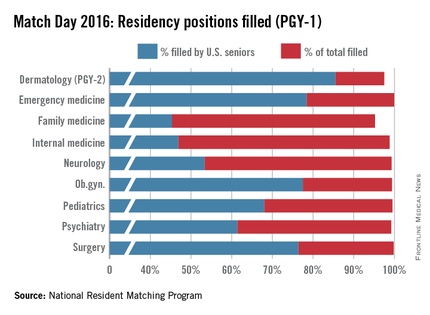

Medical school seniors scored a record number of available first-year slots in this year’s Main Residency Match, with both internal medicine and family medicine programs offering more spots to residents in 2016.

Continuing a 4-year growth trend, the number of available post-graduate year 1 (PGY-1) positions rose to 27,860 in 2016, 567 more spots than in 2015, and a record 18,668 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors registered for the match, 221 more than in 2015, according to data from the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Family medicine residency programs offered 3,238 positions in 2016, up from 3,195 in the 2015 match. This year, greater than 95% of those positions were filled; 45% were filled by U.S. medical school graduates, the NRMP announced March 18.

Internal medicine experienced similar increases, with residency programs offering 7,024 positions this year, up from 6,770 positions in 2015. Just less than 99% of the positions were filled, with 47% filled by U.S. medical school graduates in this year’s Match.

“We’re very pleased with the way the numbers turned out,” said Dr. Philip A. Masters, clinical content development director for the American College of Physicians (ACP). “About 45% of new slots in this year’s Match were in internal medicine. So that coupled with a very high fill rate really suggests a continuing and an increased interest in the field.”

Dr. Wanda Filer, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said she was glad to see an increased number of medical school graduates matching to family medicine, but she stressed that the numbers are not enough.

“This nation needs far more family medicine physicians than the current numbers are achieving,” she said in an interview. “The growth in family medicine residency slots is not fast enough and our antiquated graduate medical education payment is misaligned with U.S. workforce needs. Additionally, poor accountability for federal dollars by some U.S. medical schools to deliver that workforce should be rapidly addressed.”

While ACP officials were satisfied with the overall internal medicine numbers, Dr. Masters said that the lack of medical students entering general internal medicine and primary care careers is concerning.

“The number of people in the regular categorical [internal medicine] training programs is a lot lower than it used to be,” Dr. Masters said in a interview. “A long time ago, upwards of half of people who went in categorical training pursued a career in general internal medicine. [Now], the overall trend tends to be away from primary care/general internal medicine. That is concerning because that’s what society really needs right now.”

Pediatric positions, meanwhile, rose slightly in 2016, growing to 2,689, with 21 more slots than last year. Just more than 99% were filled, and 68% were filled by U.S. seniors.

The NRMP data shows that of 18,668 U.S. allopathic seniors who registered for the Match this year, 18,187 submitted program choices and 17,057 matched to first-year positions. This is up from the 18,025 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors who submitted program preferences for the 2015 Match, of which 16,932 matched to first-year positions.

The larger scope of this year’s Match is likely attributed to growing enrollment among medical colleges, said NRMP President and CEO Mona Signer.

“Every year seems to be larger than the year before, at least, certainly recently,” Ms. Signer said in an interview. “It isn’t just a little bit larger. It’s a lot larger. Medical schools have been increasing enrollment and new medical schools have been [opened]. We certainly expect to see that trickle into the Match as those new schools begin to graduate their first classes and as those existing schools begin to graduate larger classes.”

But Ms. Signer agrees with others that larger Match numbers will not necessarily curb future physician shortages.

“The increasing enrollment in medical schools can’t help but at least address the physician-to-population ratio,” she said. “The issue is, are those new physicians gong to be in the specialties that we need? Obviously, we need more primary care physicians. It remains to be seen whether larger class sizes are going to result in a better physician-to-population ratio in primary care.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Medical school seniors scored a record number of available first-year slots in this year’s Main Residency Match, with both internal medicine and family medicine programs offering more spots to residents in 2016.

Continuing a 4-year growth trend, the number of available post-graduate year 1 (PGY-1) positions rose to 27,860 in 2016, 567 more spots than in 2015, and a record 18,668 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors registered for the match, 221 more than in 2015, according to data from the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Family medicine residency programs offered 3,238 positions in 2016, up from 3,195 in the 2015 match. This year, greater than 95% of those positions were filled; 45% were filled by U.S. medical school graduates, the NRMP announced March 18.

Internal medicine experienced similar increases, with residency programs offering 7,024 positions this year, up from 6,770 positions in 2015. Just less than 99% of the positions were filled, with 47% filled by U.S. medical school graduates in this year’s Match.

“We’re very pleased with the way the numbers turned out,” said Dr. Philip A. Masters, clinical content development director for the American College of Physicians (ACP). “About 45% of new slots in this year’s Match were in internal medicine. So that coupled with a very high fill rate really suggests a continuing and an increased interest in the field.”

Dr. Wanda Filer, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said she was glad to see an increased number of medical school graduates matching to family medicine, but she stressed that the numbers are not enough.

“This nation needs far more family medicine physicians than the current numbers are achieving,” she said in an interview. “The growth in family medicine residency slots is not fast enough and our antiquated graduate medical education payment is misaligned with U.S. workforce needs. Additionally, poor accountability for federal dollars by some U.S. medical schools to deliver that workforce should be rapidly addressed.”

While ACP officials were satisfied with the overall internal medicine numbers, Dr. Masters said that the lack of medical students entering general internal medicine and primary care careers is concerning.

“The number of people in the regular categorical [internal medicine] training programs is a lot lower than it used to be,” Dr. Masters said in a interview. “A long time ago, upwards of half of people who went in categorical training pursued a career in general internal medicine. [Now], the overall trend tends to be away from primary care/general internal medicine. That is concerning because that’s what society really needs right now.”

Pediatric positions, meanwhile, rose slightly in 2016, growing to 2,689, with 21 more slots than last year. Just more than 99% were filled, and 68% were filled by U.S. seniors.

The NRMP data shows that of 18,668 U.S. allopathic seniors who registered for the Match this year, 18,187 submitted program choices and 17,057 matched to first-year positions. This is up from the 18,025 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors who submitted program preferences for the 2015 Match, of which 16,932 matched to first-year positions.

The larger scope of this year’s Match is likely attributed to growing enrollment among medical colleges, said NRMP President and CEO Mona Signer.

“Every year seems to be larger than the year before, at least, certainly recently,” Ms. Signer said in an interview. “It isn’t just a little bit larger. It’s a lot larger. Medical schools have been increasing enrollment and new medical schools have been [opened]. We certainly expect to see that trickle into the Match as those new schools begin to graduate their first classes and as those existing schools begin to graduate larger classes.”

But Ms. Signer agrees with others that larger Match numbers will not necessarily curb future physician shortages.

“The increasing enrollment in medical schools can’t help but at least address the physician-to-population ratio,” she said. “The issue is, are those new physicians gong to be in the specialties that we need? Obviously, we need more primary care physicians. It remains to be seen whether larger class sizes are going to result in a better physician-to-population ratio in primary care.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Medical school seniors scored a record number of available first-year slots in this year’s Main Residency Match, with both internal medicine and family medicine programs offering more spots to residents in 2016.

Continuing a 4-year growth trend, the number of available post-graduate year 1 (PGY-1) positions rose to 27,860 in 2016, 567 more spots than in 2015, and a record 18,668 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors registered for the match, 221 more than in 2015, according to data from the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Family medicine residency programs offered 3,238 positions in 2016, up from 3,195 in the 2015 match. This year, greater than 95% of those positions were filled; 45% were filled by U.S. medical school graduates, the NRMP announced March 18.

Internal medicine experienced similar increases, with residency programs offering 7,024 positions this year, up from 6,770 positions in 2015. Just less than 99% of the positions were filled, with 47% filled by U.S. medical school graduates in this year’s Match.

“We’re very pleased with the way the numbers turned out,” said Dr. Philip A. Masters, clinical content development director for the American College of Physicians (ACP). “About 45% of new slots in this year’s Match were in internal medicine. So that coupled with a very high fill rate really suggests a continuing and an increased interest in the field.”

Dr. Wanda Filer, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said she was glad to see an increased number of medical school graduates matching to family medicine, but she stressed that the numbers are not enough.

“This nation needs far more family medicine physicians than the current numbers are achieving,” she said in an interview. “The growth in family medicine residency slots is not fast enough and our antiquated graduate medical education payment is misaligned with U.S. workforce needs. Additionally, poor accountability for federal dollars by some U.S. medical schools to deliver that workforce should be rapidly addressed.”

While ACP officials were satisfied with the overall internal medicine numbers, Dr. Masters said that the lack of medical students entering general internal medicine and primary care careers is concerning.

“The number of people in the regular categorical [internal medicine] training programs is a lot lower than it used to be,” Dr. Masters said in a interview. “A long time ago, upwards of half of people who went in categorical training pursued a career in general internal medicine. [Now], the overall trend tends to be away from primary care/general internal medicine. That is concerning because that’s what society really needs right now.”

Pediatric positions, meanwhile, rose slightly in 2016, growing to 2,689, with 21 more slots than last year. Just more than 99% were filled, and 68% were filled by U.S. seniors.

The NRMP data shows that of 18,668 U.S. allopathic seniors who registered for the Match this year, 18,187 submitted program choices and 17,057 matched to first-year positions. This is up from the 18,025 U.S. allopathic medical school seniors who submitted program preferences for the 2015 Match, of which 16,932 matched to first-year positions.

The larger scope of this year’s Match is likely attributed to growing enrollment among medical colleges, said NRMP President and CEO Mona Signer.

“Every year seems to be larger than the year before, at least, certainly recently,” Ms. Signer said in an interview. “It isn’t just a little bit larger. It’s a lot larger. Medical schools have been increasing enrollment and new medical schools have been [opened]. We certainly expect to see that trickle into the Match as those new schools begin to graduate their first classes and as those existing schools begin to graduate larger classes.”

But Ms. Signer agrees with others that larger Match numbers will not necessarily curb future physician shortages.

“The increasing enrollment in medical schools can’t help but at least address the physician-to-population ratio,” she said. “The issue is, are those new physicians gong to be in the specialties that we need? Obviously, we need more primary care physicians. It remains to be seen whether larger class sizes are going to result in a better physician-to-population ratio in primary care.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Thyroid surgery access and acceptance varies along racial lines

BOSTON – Access to and acceptance of thyroid cancer surgery varies by race, with black patients in particular appearing to be disadvantaged, compared with whites, investigators reported.

A review of data on nearly 138,000 patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer showed that blacks were significantly less likely than were whites to be offered surgery – despite its generally excellent outcomes and low rates of morbidity and mortality, reported Dr. Herbert Castillo Valladares and his colleagues from the department of surgery at the Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

American Indians/Alaskan natives and Asian/Pacific Islanders were significantly more likely to refuse surgery than were whites, the investigators also reported in a poster session at the Society of Surgical Oncology annual cancer symposium.

“In this project, we wanted to focus on the provider-level factors that might be perpetuating these racial disparities, and it appears that we need to educate some providers about the recommendation of surgery or how to educate patients who refuse thyroid cancer surgery,” Dr. Valladares said in an interview.

The investigators noted that although incidence and prevalence rates of thyroid cancer are similar among various racial groups, survival differs by race, and they wanted to find out why. To do so, they polled the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry to identify 137,483 patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer during 1988-2012. Results were stratified by thyroid cancer type, either papillary, medullary, follicular, or anaplastic.

In all, 82% of the sample were white, 75% were female, 87% had a diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer, and 95% underwent thyroid cancer surgery.

In logistic regression analysis that controlled for race, the investigators found that blacks, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and persons of unknown race were significantly less likely than whites were to have thyroid cancer surgery (odds ratios, 0.7, 0.82, and 0.34, respectively; P for each less than .0001).

Similarly, surgery was more frequently not recommended for blacks (OR, 1.34; P less than .0001), Asian/Pacific Islanders (OR, 1.2; P = .004) and those of unknown race (OR, 3.06; P less than .0001).

American Indians/Alaskan natives and Asian/Pacific Islanders were also significantly more likely than were whites to refuse surgery (OR, 4.45; P = .0001; OR, 2.96; P less than .0001, respectively).

Compared with whites, blacks – but not other races – had significantly worse 5-year survival (hazard ratio, 1.14; P = .0002).

In an analysis by cancer type, the investigators saw that race was not a predictor for surgery recommendation or refusal of surgery by patients with medullary or anaplastic cancer. However, among patients with papillary thyroid cancer, the most common type, surgery was recommended less often for blacks (OR, 1.2), Asian/Pacific Islanders (OR, 1.3), and patients of unknown race (OR, 3.1; all comparisons significant by 95% confidence interval).

Among patients with follicular histology, patients of unknown race were significantly less likely than were whites to have the surgery recommended (OR, 2.7; significant by 95% CI).

Dr. Valladares explained that the SEER data set does not include information about provider type, such as those in community based versus academic settings, so the next step will be to find a method for analyzing factors at both the patient level and the provider level that might influence recommendations for surgery or patient refusals to accept surgery.

The study was supported by the Paul H. Lavietes, M.D., Summer Research Fellowship of Yale University. The investigators reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – Access to and acceptance of thyroid cancer surgery varies by race, with black patients in particular appearing to be disadvantaged, compared with whites, investigators reported.

A review of data on nearly 138,000 patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer showed that blacks were significantly less likely than were whites to be offered surgery – despite its generally excellent outcomes and low rates of morbidity and mortality, reported Dr. Herbert Castillo Valladares and his colleagues from the department of surgery at the Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

American Indians/Alaskan natives and Asian/Pacific Islanders were significantly more likely to refuse surgery than were whites, the investigators also reported in a poster session at the Society of Surgical Oncology annual cancer symposium.

“In this project, we wanted to focus on the provider-level factors that might be perpetuating these racial disparities, and it appears that we need to educate some providers about the recommendation of surgery or how to educate patients who refuse thyroid cancer surgery,” Dr. Valladares said in an interview.

The investigators noted that although incidence and prevalence rates of thyroid cancer are similar among various racial groups, survival differs by race, and they wanted to find out why. To do so, they polled the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry to identify 137,483 patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer during 1988-2012. Results were stratified by thyroid cancer type, either papillary, medullary, follicular, or anaplastic.

In all, 82% of the sample were white, 75% were female, 87% had a diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer, and 95% underwent thyroid cancer surgery.

In logistic regression analysis that controlled for race, the investigators found that blacks, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and persons of unknown race were significantly less likely than whites were to have thyroid cancer surgery (odds ratios, 0.7, 0.82, and 0.34, respectively; P for each less than .0001).