User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Spending on physicians rising faster than health expenditures overall

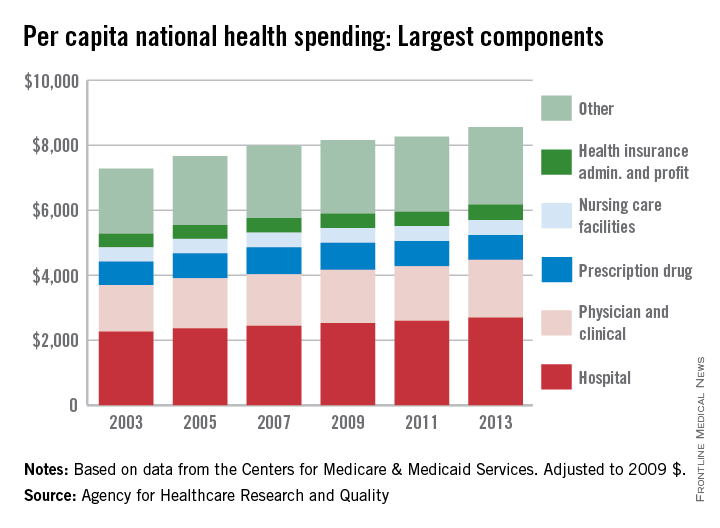

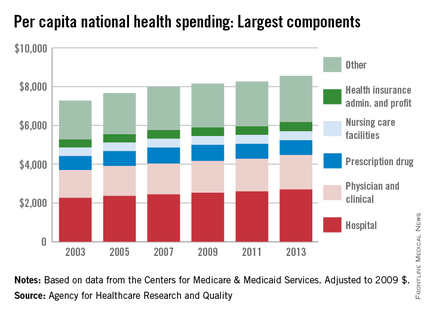

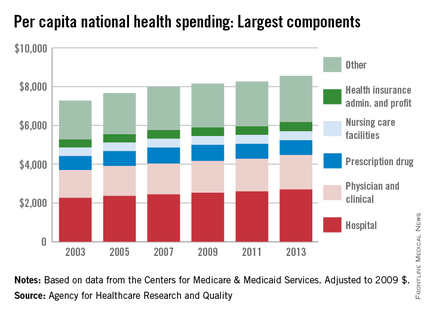

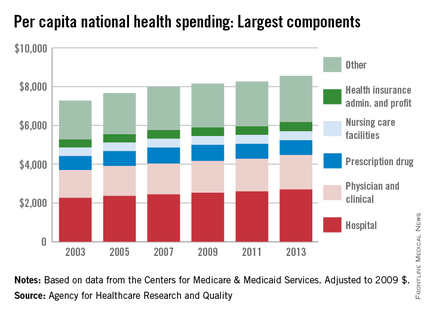

Spending on physicians rose by 2.4% per year from 2003 to 2013 – the largest increase among the major components of national health expenditures, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Per capita spending for the physician and clinical sector went from $1,432 in 2003 to $1,775 in 2013 when adjusted to 2009 dollars, for a total increase of almost 24%. Total per capita health expenditures were $7,284 in 2003 and $8,555 in 2013, which represents an annual increase of 1.75%, the AHRQ reported.

The largest portion of national health expenditures, hospital spending, increased from $2,264 (in 2009 dollars) per capita in 2003 to $2,700 in 2013 – just under 2% per year. Physician and clinical costs were the second-largest component of health expenditures, followed by prescription drugs, health insurance administration and profit, and nursing care facilities in 2013, the AHRQ noted.

Overall per capita spending on prescription drugs was up just 0.5% from 2003 to 2013, giving it the smallest increase among the five sectors. Spending on nursing home facilities rose slightly more, 0.7% a year, while the cost of insurance company administration and profit increased by 1.4% a year over that time, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Spending on physicians rose by 2.4% per year from 2003 to 2013 – the largest increase among the major components of national health expenditures, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Per capita spending for the physician and clinical sector went from $1,432 in 2003 to $1,775 in 2013 when adjusted to 2009 dollars, for a total increase of almost 24%. Total per capita health expenditures were $7,284 in 2003 and $8,555 in 2013, which represents an annual increase of 1.75%, the AHRQ reported.

The largest portion of national health expenditures, hospital spending, increased from $2,264 (in 2009 dollars) per capita in 2003 to $2,700 in 2013 – just under 2% per year. Physician and clinical costs were the second-largest component of health expenditures, followed by prescription drugs, health insurance administration and profit, and nursing care facilities in 2013, the AHRQ noted.

Overall per capita spending on prescription drugs was up just 0.5% from 2003 to 2013, giving it the smallest increase among the five sectors. Spending on nursing home facilities rose slightly more, 0.7% a year, while the cost of insurance company administration and profit increased by 1.4% a year over that time, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Spending on physicians rose by 2.4% per year from 2003 to 2013 – the largest increase among the major components of national health expenditures, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Per capita spending for the physician and clinical sector went from $1,432 in 2003 to $1,775 in 2013 when adjusted to 2009 dollars, for a total increase of almost 24%. Total per capita health expenditures were $7,284 in 2003 and $8,555 in 2013, which represents an annual increase of 1.75%, the AHRQ reported.

The largest portion of national health expenditures, hospital spending, increased from $2,264 (in 2009 dollars) per capita in 2003 to $2,700 in 2013 – just under 2% per year. Physician and clinical costs were the second-largest component of health expenditures, followed by prescription drugs, health insurance administration and profit, and nursing care facilities in 2013, the AHRQ noted.

Overall per capita spending on prescription drugs was up just 0.5% from 2003 to 2013, giving it the smallest increase among the five sectors. Spending on nursing home facilities rose slightly more, 0.7% a year, while the cost of insurance company administration and profit increased by 1.4% a year over that time, according to data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

New CDC opioid guideline targets overprescribing for chronic pain

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Nonopioid therapy is the preferred approach for managing chronic pain outside of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care, according to a new guideline released today by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 12 recommendations included in the guideline center around this principle and two others: using the lowest possible effective dosage when opioids are used, and exercising caution and monitoring patients closely when prescribing opioids.

Specifically, the guideline states that “clinicians should consider opioid therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient,” and that “treatment should be combined with nonpharmacologic and nonopioid therapy, as appropriate.”

The guideline also addresses steps to take before starting or continuing opioid therapy, and drug selection, dosage, duration, follow-up, and discontinuation. Recommendations for assessing risk and addressing harms of opioid use are also included.

The CDC developed the guideline as part of the U.S. government’s urgent response to the epidemic of overdose deaths, which has been fueled by a quadrupling of the prescribing and sales of opioids since 1999, according to a CDC press statement. The guideline’s purpose is to help prevent opioid misuse and overdose.

“The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, United States, 2016 will help primary care providers ensure the safest and most effective treatment for their patients,” according to the statement. The CDC’s director, Dr. Tom Frieden, noted that “overprescribing opioids – largely for chronic pain – is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic.”

In a CDC teleconference marking the release of the guideline, Dr. Frieden said it has become increasingly clear that opioids “carry substantial risks but only uncertain benefits, especially compared with other treatments for chronic pain.

“Beginning treatment with an opioid is a momentous decision, and it should only be done with full understanding by both the clinician and the patient of the substantial risks and uncertain benefits involved,” Dr. Frieden said. He added that he knows of no other medication “that’s routinely used for a nonfatal condition [and] that kills patients so frequently.

“With more than 250 million prescriptions written each year, it’s so important that doctors understand that any one of those prescriptions could potentially end a patient’s life,” he cautioned.

A 2015 study showed that 1 of every 550 patients treated with opioids for noncancer pain – and 1 of 32 who received the highest doses (more than 200 morphine milligram equivalents per day) – died within 2.5 years of the first prescription.

Dr. Frieden noted that opioids do have a place when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. “But for most patients – the vast majority of patients – the risks will outweigh the benefits,” he said.

The opioid epidemic is one of the most pressing public health issues in the United States today, said Sylvia M. Burwell, secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services. A year ago, she announced an HHS initiative to reduce prescription opioid and heroin-related drug overdose, death, and dependence.

“Last year, more Americans died from drug overdoses than car crashes,” Ms. Burwell said during the teleconference, noting that families across the nation and from all walks of life have been affected.

Combating the opioid epidemic is a national priority, she said, and the CDC guideline will help in that effort.

“We believe this guideline will help health care professionals provide safer and more effective care for patients dealing with chronic pain, and we also believe it will help these providers drive down the rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, and ... death,” she said.

The American Medical Association greeted the guideline with cautious support.

“While we are largely supportive of the guidelines, we remain concerned about the evidence base informing some of the recommendations,” noted Dr. Patrice A. Harris, chair-elect of the AMA board and chair of the AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse, in a statement.

The AMA also cited potential conflicts between the guideline and product labeling and state laws, as well as obstacles such as insurance coverage limits on nonpharmacologic treatments.

“If these guidelines help reduce the deaths resulting from opioids, they will prove to be valuable,” Dr. Harris said in the statement. “If they produce unintended consequences, we will need to mitigate them.”

Of note, the guideline stresses the right of patients with chronic pain to receive safe and effective pain management, and focuses on giving primary care providers – who account for about half of all opioid prescriptions – a road map for providing such pain management by increasing the use of effective nonopioid and nonpharmacologic therapies.

It was developed through a “rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments from the public and partner organizations,” according to the CDC statement. The organization “is dedicated to working with partners to improve the evidence base and will refine the recommendations as new research becomes available.

”In conjunction with the release of the guideline, the CDC has provided a checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, and a website with additional tools for implementing the recommendations within the guideline.

The CDC's opioid recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s new opioid prescription guideline includes 12 recommendations. Here they are, modified slightly for style:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy, and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to 50 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day, and generally should avoid increasing dosage to 90 or more MME per day.

6. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids. Three or fewer days often will be sufficient.

7. Providers should evaluate the benefits and harms with patients within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. They should reevaluate continued therapy’s benefits and harms every 3 months or more frequently. If continued therapy’s benefits do not outweigh harms, providers should work with patients to reduce dosages or discontinue opioids.

8. During therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harm. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose – such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosage (50 MME or more) – are present.

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications, as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid concurrent prescriptions of opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

M. Alexander Otto contributed to this article.

Flu vaccination found safe in surgical patients

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they leave the hospital appears safe.

Major finding: Patients received a flu vaccine in only 6,420 hospital stays for surgery, comprising only 15% of the patient hospitalizations that were eligible.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 81,647 surgeries at 14 California hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Enlarged uterus helps predict morcellation in vaginal hysterectomy

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Women with a larger-than-normal uterus are likelier to undergo cold-knife morcellation versus intact uterine removal during a vaginal hysterectomy.

Major finding: Larger-than-normal uterine weight was associated with increased odds of morcellation (aOR, 7.25; P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 743 women selected for vaginal hysterectomy.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Outcomes in major surgery unchanged by continuing clopidogrel

MONTREAL – Patients who stayed on antiplatelet therapy close to – or even up until – major surgery fared just as well as those who stopped their medication earlier in a retrospective, single-center study.

The study found no difference in blood product administration, adverse perioperative events, or all-cause 30-day mortality regardless of whether patients stopped clopidogrel (Plavix) the recommended 5 days before surgery.

“We believe that continuing clopidogrel in elective and emergent surgical situations appears to be safe, and may challenge the current recommendations,” said presenter Dr. David Strosberg.

The study addressed a thorny question for surgeons, Dr. Strosberg said. “As surgeons, we face a dilemma: Do we take the risk of thrombotic complications in stopping the antiplatelet drugs, or do we take the risk of increased surgical bleeding with continuing therapy?”

The package insert for clopidogrel advises discontinuation 5 days prior to surgery. However, manufacturer labeling also states that discontinuation of clopidogrel can lead to adverse cardiac events, said Dr. Strosberg, a general surgery resident at Ohio State University in Columbus.

The aim of the study, presented at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, was to ascertain whether continuing antiplatelet therapy increased the rate of adverse surgical outcomes in those undergoing major emergent or elective surgery.

Dr. Strosberg and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the record of patients over a 4-year period at a single institution and included those undergoing major general, thoracic, or vascular surgery who were taking clopidogrel at the time of presentation.

Data collected included patient characteristics, including demographic data and comorbidities, as well as transfusion requirements and perioperative events.

A total of 200 patients who had 205 qualifying procedures and were taking clopidogrel were included in the study. Of these, 116 patients (Group A) had their clopidogrel held for at least 5 days preoperatively. The remaining 89 patients (Group B) had their clopidogrel held for less than 5 days, or not at all.

Patient demographics were similar between the two groups. Patients in Group A were more likely to have emergency surgery, to have peripheral stents placed, to have COPD or peripheral vascular disease, to have a malignancy, and to have received aspirin within five days of surgery (P less than .01 for all).

Blood product administration rates and volumes did not differ significantly between the two groups, and there was no difference between the groups in the incidence of myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular events, or acute visceral or lower extremity ischemia.

Three patients in each group died within 30 days of the procedure, a nonsignificant difference. However, in the group that had clopidogrel held, three patients had perioperative myocardial infarctions, and two of these patients died. In discussing the study, Dr. Michael Dalsing said, “I think a lot of us would accept bleeding more over myocardial infarction.”

A subgroup analysis of the group who had clopidogrel held for fewer than 5 days compared outcomes for emergent vs. non-emergent surgery. The emergent surgery subgroup had a significantly higher rate of preoperative platelet transfusions, although numbers overall were small (2/17, 11.8%, vs. 0/72; P = .03).

Dr. Strosberg noted study limitations that included the retrospective, single-center nature of the study, and the fact that one variable, estimated blood loss, is notoriously subjective and inaccurate.

Dr. Dalsing, chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said that he “was surprised that not even one patient went back for postoperative bleeding in this high-risk group of patients,” and raised the question of potential selection bias. Dr. Strosberg replied that comorbidities were ascertained by the physician at the time of surgery planning; since no differences were seen between study groups, investigators didn’t go back and parse out details about comorbid conditions.

In discussion following the presentation, surgeons spoke to the real-world challenges of performing surgery on a patient with antiplatelet therapy on board.

“Overall, I think your data support kind of a bias I have. Since I’m a vascular surgeon, we almost always operate on clopidogrel, and I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better. But it’s something we almost have to do to keep our grafts going,” Dr. Dalsing said.

Dr. Peter Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said, “I’d be a little bit cautious with this. If you’ve ever done a big aortic procedure on someone on Plavix, I’ve seen them lose up to a couple of liters of blood just with oozing.”

“Those of us who do open aortic surgery know that very few things bleed like the back wall of an aortic anastomosis of a patient on Plavix,” echoed Dr. Peter Rossi, associate professor of vascular surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – Patients who stayed on antiplatelet therapy close to – or even up until – major surgery fared just as well as those who stopped their medication earlier in a retrospective, single-center study.

The study found no difference in blood product administration, adverse perioperative events, or all-cause 30-day mortality regardless of whether patients stopped clopidogrel (Plavix) the recommended 5 days before surgery.

“We believe that continuing clopidogrel in elective and emergent surgical situations appears to be safe, and may challenge the current recommendations,” said presenter Dr. David Strosberg.

The study addressed a thorny question for surgeons, Dr. Strosberg said. “As surgeons, we face a dilemma: Do we take the risk of thrombotic complications in stopping the antiplatelet drugs, or do we take the risk of increased surgical bleeding with continuing therapy?”

The package insert for clopidogrel advises discontinuation 5 days prior to surgery. However, manufacturer labeling also states that discontinuation of clopidogrel can lead to adverse cardiac events, said Dr. Strosberg, a general surgery resident at Ohio State University in Columbus.

The aim of the study, presented at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, was to ascertain whether continuing antiplatelet therapy increased the rate of adverse surgical outcomes in those undergoing major emergent or elective surgery.

Dr. Strosberg and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the record of patients over a 4-year period at a single institution and included those undergoing major general, thoracic, or vascular surgery who were taking clopidogrel at the time of presentation.

Data collected included patient characteristics, including demographic data and comorbidities, as well as transfusion requirements and perioperative events.

A total of 200 patients who had 205 qualifying procedures and were taking clopidogrel were included in the study. Of these, 116 patients (Group A) had their clopidogrel held for at least 5 days preoperatively. The remaining 89 patients (Group B) had their clopidogrel held for less than 5 days, or not at all.

Patient demographics were similar between the two groups. Patients in Group A were more likely to have emergency surgery, to have peripheral stents placed, to have COPD or peripheral vascular disease, to have a malignancy, and to have received aspirin within five days of surgery (P less than .01 for all).

Blood product administration rates and volumes did not differ significantly between the two groups, and there was no difference between the groups in the incidence of myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular events, or acute visceral or lower extremity ischemia.

Three patients in each group died within 30 days of the procedure, a nonsignificant difference. However, in the group that had clopidogrel held, three patients had perioperative myocardial infarctions, and two of these patients died. In discussing the study, Dr. Michael Dalsing said, “I think a lot of us would accept bleeding more over myocardial infarction.”

A subgroup analysis of the group who had clopidogrel held for fewer than 5 days compared outcomes for emergent vs. non-emergent surgery. The emergent surgery subgroup had a significantly higher rate of preoperative platelet transfusions, although numbers overall were small (2/17, 11.8%, vs. 0/72; P = .03).

Dr. Strosberg noted study limitations that included the retrospective, single-center nature of the study, and the fact that one variable, estimated blood loss, is notoriously subjective and inaccurate.

Dr. Dalsing, chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said that he “was surprised that not even one patient went back for postoperative bleeding in this high-risk group of patients,” and raised the question of potential selection bias. Dr. Strosberg replied that comorbidities were ascertained by the physician at the time of surgery planning; since no differences were seen between study groups, investigators didn’t go back and parse out details about comorbid conditions.

In discussion following the presentation, surgeons spoke to the real-world challenges of performing surgery on a patient with antiplatelet therapy on board.

“Overall, I think your data support kind of a bias I have. Since I’m a vascular surgeon, we almost always operate on clopidogrel, and I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better. But it’s something we almost have to do to keep our grafts going,” Dr. Dalsing said.

Dr. Peter Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said, “I’d be a little bit cautious with this. If you’ve ever done a big aortic procedure on someone on Plavix, I’ve seen them lose up to a couple of liters of blood just with oozing.”

“Those of us who do open aortic surgery know that very few things bleed like the back wall of an aortic anastomosis of a patient on Plavix,” echoed Dr. Peter Rossi, associate professor of vascular surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – Patients who stayed on antiplatelet therapy close to – or even up until – major surgery fared just as well as those who stopped their medication earlier in a retrospective, single-center study.

The study found no difference in blood product administration, adverse perioperative events, or all-cause 30-day mortality regardless of whether patients stopped clopidogrel (Plavix) the recommended 5 days before surgery.

“We believe that continuing clopidogrel in elective and emergent surgical situations appears to be safe, and may challenge the current recommendations,” said presenter Dr. David Strosberg.

The study addressed a thorny question for surgeons, Dr. Strosberg said. “As surgeons, we face a dilemma: Do we take the risk of thrombotic complications in stopping the antiplatelet drugs, or do we take the risk of increased surgical bleeding with continuing therapy?”

The package insert for clopidogrel advises discontinuation 5 days prior to surgery. However, manufacturer labeling also states that discontinuation of clopidogrel can lead to adverse cardiac events, said Dr. Strosberg, a general surgery resident at Ohio State University in Columbus.

The aim of the study, presented at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, was to ascertain whether continuing antiplatelet therapy increased the rate of adverse surgical outcomes in those undergoing major emergent or elective surgery.

Dr. Strosberg and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed the record of patients over a 4-year period at a single institution and included those undergoing major general, thoracic, or vascular surgery who were taking clopidogrel at the time of presentation.

Data collected included patient characteristics, including demographic data and comorbidities, as well as transfusion requirements and perioperative events.

A total of 200 patients who had 205 qualifying procedures and were taking clopidogrel were included in the study. Of these, 116 patients (Group A) had their clopidogrel held for at least 5 days preoperatively. The remaining 89 patients (Group B) had their clopidogrel held for less than 5 days, or not at all.

Patient demographics were similar between the two groups. Patients in Group A were more likely to have emergency surgery, to have peripheral stents placed, to have COPD or peripheral vascular disease, to have a malignancy, and to have received aspirin within five days of surgery (P less than .01 for all).

Blood product administration rates and volumes did not differ significantly between the two groups, and there was no difference between the groups in the incidence of myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular events, or acute visceral or lower extremity ischemia.

Three patients in each group died within 30 days of the procedure, a nonsignificant difference. However, in the group that had clopidogrel held, three patients had perioperative myocardial infarctions, and two of these patients died. In discussing the study, Dr. Michael Dalsing said, “I think a lot of us would accept bleeding more over myocardial infarction.”

A subgroup analysis of the group who had clopidogrel held for fewer than 5 days compared outcomes for emergent vs. non-emergent surgery. The emergent surgery subgroup had a significantly higher rate of preoperative platelet transfusions, although numbers overall were small (2/17, 11.8%, vs. 0/72; P = .03).

Dr. Strosberg noted study limitations that included the retrospective, single-center nature of the study, and the fact that one variable, estimated blood loss, is notoriously subjective and inaccurate.

Dr. Dalsing, chief of vascular surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said that he “was surprised that not even one patient went back for postoperative bleeding in this high-risk group of patients,” and raised the question of potential selection bias. Dr. Strosberg replied that comorbidities were ascertained by the physician at the time of surgery planning; since no differences were seen between study groups, investigators didn’t go back and parse out details about comorbid conditions.

In discussion following the presentation, surgeons spoke to the real-world challenges of performing surgery on a patient with antiplatelet therapy on board.

“Overall, I think your data support kind of a bias I have. Since I’m a vascular surgeon, we almost always operate on clopidogrel, and I don’t know if our bleeding risk is worse or better. But it’s something we almost have to do to keep our grafts going,” Dr. Dalsing said.

Dr. Peter Henke, professor of vascular surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said, “I’d be a little bit cautious with this. If you’ve ever done a big aortic procedure on someone on Plavix, I’ve seen them lose up to a couple of liters of blood just with oozing.”

“Those of us who do open aortic surgery know that very few things bleed like the back wall of an aortic anastomosis of a patient on Plavix,” echoed Dr. Peter Rossi, associate professor of vascular surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Outcomes were similar whether patients did or didn’t stop clopidogrel before major surgery.

Major finding: No significant differences in blood product use, adverse events, or death were seen with continuing clopidogrel.

Data source: Retrospective, single-center review of 200 patients undergoing major elective or emergent surgery and taking clopidogrel.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Treat most older women with stage I breast cancer with lumpectomy only

MIAMI – The trend over time to use less invasive surgery for breast cancer – from radical mastectomy to radical modified mastectomy to simplified mastectomy to lumpectomy – should extend now radiation therapy in older women with stage I disease, “and not give it unless it’s absolutely needed,” Dr. Kevin Hughes said at the annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, held by Physicians’ Education Resource.

In fact, in most instances, these older women should receive lumpectomy without radiation, said Dr. Hughes of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Three major trials that looked at stage I cancer in women over 50, 65, or 70 years of age reached the same conclusion: that radiation adds little benefit to overall treatment.

Dr. Hughes also said oncologists with genomic information on a specific cancer can also choose to more judiciously order radiation treatment, particularly with luminal A and, possibly, luminal B cancers.

Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MIAMI – The trend over time to use less invasive surgery for breast cancer – from radical mastectomy to radical modified mastectomy to simplified mastectomy to lumpectomy – should extend now radiation therapy in older women with stage I disease, “and not give it unless it’s absolutely needed,” Dr. Kevin Hughes said at the annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, held by Physicians’ Education Resource.

In fact, in most instances, these older women should receive lumpectomy without radiation, said Dr. Hughes of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Three major trials that looked at stage I cancer in women over 50, 65, or 70 years of age reached the same conclusion: that radiation adds little benefit to overall treatment.

Dr. Hughes also said oncologists with genomic information on a specific cancer can also choose to more judiciously order radiation treatment, particularly with luminal A and, possibly, luminal B cancers.

Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MIAMI – The trend over time to use less invasive surgery for breast cancer – from radical mastectomy to radical modified mastectomy to simplified mastectomy to lumpectomy – should extend now radiation therapy in older women with stage I disease, “and not give it unless it’s absolutely needed,” Dr. Kevin Hughes said at the annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, held by Physicians’ Education Resource.

In fact, in most instances, these older women should receive lumpectomy without radiation, said Dr. Hughes of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Three major trials that looked at stage I cancer in women over 50, 65, or 70 years of age reached the same conclusion: that radiation adds little benefit to overall treatment.

Dr. Hughes also said oncologists with genomic information on a specific cancer can also choose to more judiciously order radiation treatment, particularly with luminal A and, possibly, luminal B cancers.

Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MBCC

Global Surgery: ‘Partnership Among Friends’

Surgery volunteerism has been on the rise for several decades. The American College of Surgeons is increasing its role in organizing and facilitating these programs via Operation Giving Back (OGB). And many ACS members are prominent participants in this endeavor.

A leader in global surgery is Michael L. Bentz, M.D., FAAP, FACS, professor of surgery, pediatrics, and neurosurgery, and chairman of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Bentz has led international missions in many countries of the world over nearly 20 years and has helped a team develop a long-term program of clinical care and training in Nicaragua. We talked with him about his experiences.

Q: You have been involved in international surgical missions for many years. Can you tell us something about your early projects?

I was first exposed to international work at the University of Pittsburgh. My mentor J. William Futrell, M.D., FACS, was a veteran of over 30 international surgical trips. I went on the first trip with him to Vietnam in the 1997 and have been going ever since. For that initial trip, we worked with a nonprofit organization called Interplast. I went with a large group of 20 people from the University that included plastic surgery attendings, plastic surgery residents, pediatric attendings, pediatric residents, and nursing and anesthesia staff.

In those days, many trips were based predominantly on clinical care – adult care and pediatric care. Teams would do a certain number of operations and then go home. We did cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, burn reconstruction, congenital hand deformity surgery, and tumor management.

That would result in good outcomes for those who actually had a procedure done. But in any place I have ever worked overseas – Vietnam, China, Russia, Nicaragua – the need is overwhelming. The need far outstripped what surgical missions can provide in isolated, single trips back and forth.

Q: The years have brought changes to these missions. What are the most significant changes over the years in how these missions are conducted?

The scope and direction of global health is moving toward sustainable, long-term, and longitudinal education. In those earlier trips where there was an emphasis on doing as many operations as possible, people meant well – we meant well! But the real impact comes with the longitudinal education investment.

I have never been anywhere around the world where there weren’t interested, very capable, excellent surgeons committed to taking care of their patients who only need some support and facilitation.

If you compare the cases we are able to do on a trip with our partners with the cases they are able to do independently, it’s a logarithmic curve – they are far more productive than we could ever be on any number of trips. There is a multiplier effect that allows many more patients to be taken care of.

Q: Your institution has a long-term relationship with a hospital in Nicaragua. How does this work and what is the role of your team in the program?

The University of Wisconsin Division of Plastic Surgery and the Eduplast Foundation has a team of about 10 that goes to Nicaragua twice a year. Most importantly, we support a residency program in there. We move residents through a 3-year modular program much like programs in the U.S. and then examine them. We facilitate this educational process with trips there and we bring them to our institution in the U.S.

Over the past 10 years, we have been doing a weekly live webcast of our Plastic Surgery Grand Rounds which is received on several continents. This creates a very valuable bidirectional, and even tridirectional conversation. This webcast is simple, incredibly inexpensive, and has provided hundreds of hours of education over the years in addition to the on-site work we do.

There can be a language barrier in some cases, but we broadcast in English, with occasional translation support. In addition to Nicaragua, our webcast has been received in institutions in Thailand, China, Ecuador and across the United States. We keep records of cases performed. Our plastic surgery residents can get credit for the cases they do under faculty supervision at our international sites if we meet specific criteria set by our Resident Review Committee.

It is important to note that we take care of the patients in our partner institutions in Nicaragua exactly as we would care for patients in our institution in Wisconsin. There is no “practicing” as all operations are done by surgeons appropriately credentialed and trained for the task.

Q: Do you find that there is a cultural gap that you must bridge in working with colleagues and patients in Nicaragua?

Our program has an orientation session for team participants in advance of each trip, where we talk about the mechanics of the trip – safety, medical issues. We also talk about cultural considerations of each site. It is very important that the residents embed in the culture in which we are working. They also need to know the cultural norms of how to communicate with patients, parents, and children. Some of it is simply good manners – acting like your mother taught you!

The team can reside in a local hotel, but often stays in the homes of local hosts, and this can be a beautiful opportunity to learn about local norms and communication.

Q: What is your favorite part of these missions?

I have so many favorite parts! I like caring for people who otherwise might not receive medical care. This is “giving back” and I think all of the participants would agree that we come home feeling like we received much more than we gave. These experiences remind you of why you went to medical school. It is an opportunity to provide something in return for all the investment that has been made in us for our education. In working with colleagues from other countries, I learn as much as I teach. I come back a better surgeon.

The benefits to residents from our institution are many. They learn how to operate in a resource-limited setting, and they return with a greater appreciation for the equipment and supplies we have available at our institution in Madison. The cultural competence and awareness they also learn is an invaluable life skill.

I want to stress that the friendships with our fellow surgeons are what makes this work. We achieve a degree of continuity and even watch our pediatric patients grow up over the years because of our long-term relationship with the hospital in León and our dedicated colleagues there. This is a truly a partnership among friends.

Q: Do you have some advice for a surgeon interested in participating in an international program?

For those surgeons who were not exposed to these programs during residency, finding a mentor or mentoring organization is the way to begin. A beginner should consider making the first couple of trips with someone who knows the ropes in terms of understanding cultural competency, practical issues of safety, and relevant clinical issues. Almost every surgery discipline has an organization with the capability of identifying volunteer surgery groups in their specialty. ACS’ Operation Giving Back is a particularly important resource for helping Fellows find the right international program.

If you would like to learn more about global surgery programs, contact Operation Giving Back at [email protected]. Or if you would like to share your experiences as an international surgical volunteer, please email this publication at [email protected].

Surgery volunteerism has been on the rise for several decades. The American College of Surgeons is increasing its role in organizing and facilitating these programs via Operation Giving Back (OGB). And many ACS members are prominent participants in this endeavor.