User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Point-Counterpoint: Hospital-acquired infections: Is getting to zero the right medicine?

YES – Eliminating HAIs is feasible and may help better focus prevention efforts.

For many years, research suggested that reducing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) by one-third was the best we could do. But recent landmark efforts, such as the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2005;54:1013-16) and the Michigan Keystone Project (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2725-32), have shattered our notions of how many HAIs might be preventable, achieving reductions of nearly 70% in central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). Similarly, a national campaign in England has achieved a 68% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections (Health Prot. Rep. 2012;6:38).

These new data suggest that possibly all HAIs are preventable, and there are now many published reports in which institutions have reached zero. For example, the Hawaii experience has shown that a prevention initiative achieved a median rate of zero catheter-related bloodstream infections (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9).

The advances in HAI prevention are coming in the context of an ever increasingly sick patient population, with patients who are more complicated than ever before. In fact, many of the greatest gains in CLABSI prevention have been among the very sickest patients in our hospitals – in the intensive care unit – as at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (Crit. Care Med. 2004;32:2014-20). So the rationale that we cannot get to zero because our patients are too sick simply is not relevant anymore.

We won’t know how many HAIs are preventable until we hit the bottom. But if our goal is not zero, we will likely end up accepting some infections that might be preventable. Therefore, we must set the goal at zero infections.

What if we don’t get there? That would suggest that some of these infections might not be related to health care delivery but rather to patient risk factors. And these are the infections that we can target. New research could end up preventing some of them. Modifications in definitions might be necessary to account for some of these infections.

One might then argue that we are just defining our way to zero. I would counter that plenty of places have, in fact, hit zero CLABSIs without any changes in our current definitions. But I will also argue that rational changes in our definitions will be needed to help us differentiate truly preventable HAIs and allow us to better focus our prevention efforts.

An excellent example is the new definition of the mucosal barrier injury–related bloodstream infections, which was discussed during the recent IDWeek. Making such an evidence-based change to a definition to focus prevention efforts is neither gaming nor cheating—it’s called good science and good policy.

The zero goal will also improve medical care through the wider adoption of best practices. Published reports of HAI prevention efforts show the successes have been obtained through the implementation of best practices, not through gaming, not through cheating. Zero HAIs as a goal is already driving real improvements in patient safety and quality.

Pushing for zero HAIs will also further research. How much can we argue for pushing the prevention research envelope if we decide that some of these infections are simply okay? How are we going to argue for funding for more prevention research if we tell them the infections aren’t really preventable? We will be much more successful if it’s clear that we need it to get to zero HAIs.

Getting to zero has been put forth as a goal that we should aim for, not as a standard that people should be punished for in the event it is not attained. In fact, value-based purchasing rules are based on relative infection rates – not on zero infection rates.

Moreover, it’s a long-range goal. This is not something that anyone is advocating for overnight. Evidence of that can be seen in the National Action Plan to Prevent HAIs, which calls for 30%-50% reductions, not zero, as the target for the first 5 years.

It must be acknowledged that sometimes an HAI is someone’s fault. Many U.S. institutions have yet to implement best practices for preventing CLABSIs, for example. How long can we hold these hospitals blameless for failing to do this?

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine, but the only medicine. It is our successes, published in our own medical literature, that have prompted the push to get to zero. We shouldn’t run away from the success that we have had; we should embrace it and build on it. Patients will no longer accept a goal of preventing some HAIs, and neither should we.

Dr. Srinivasan is associate director for health care–associated infection prevention programs, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

NO – Eliminating HAIs is unrealistic and has unintended negative consequences.

There are a variety of reasons why getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine. First and probably most important is that it is dishonest. Patients today are sicker and more immunosuppressed, and the devices we use are ever more invasive. When we have patients in our hospitals who, for example, have total artificial hearts in place for more than a year, can we realistically imagine that there would not be any HAIs? I don’t think so.

Extensive medical literature documenting infection prevention initiatives attests to this. For example, a recent analysis suggests that even if all U.S. hospitals implemented all of the measures known to prevent HAIs, at best 55%-70% of common HAIs would reasonably be preventable (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011;32:101-14). None were found to be 100% preventable.

If one looks closely at the Hawaii experience showing a median rate of zero HAIs, you actually see a 61% reduction in the rate of CLABSIs over 1.5 years, but it never reaches zero (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9). That translates to up to 10 infections per quarter. So we can use words in loose ways and talk about zero median infections, but there were not zero infections in that study. If the final rate of 0.6/1,000 catheter-days were applied to my hospital, it would translate to 11 CLABSIs annually – hardly a number that would allow me to say I had eliminated these infections.

Efforts to achieve zero HAIs may be a manifestation of postmodernism, a philosophical paradigm in which there is no absolute truth, and one that puts evidence-based medicine on par with practices such as homeopathy and the notion that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine causes autism.

Aiming for zero HAIs drives a punitive culture. If we accept the concept of getting to zero, it then means that zero is actually attainable, and if that is true, then all HAIs are preventable. And if that is true, logic tells us then that the occurrence of an HAI must be someone’s fault.

The zero goal places enormous pressure on infection preventionists and their programs, and it creates adversarial relationships between infection prevention services and clinicians as they argue about whether an event is an infection. Hospital administrators ask why programs are not reaching zero. And the infection prevention people are caught in the middle of all this. They are in a terrible position: In some cases, they are deciding – in a way – whether people will get a pay raise or will be fired from their jobs.

Trying to eliminate HAIs fosters problems with surveillance, such as outright cheating, making subtle changes to case definitions that reduce infection rates, and underfunding infection prevention programs to reduce their sensitivity for case ascertainment.

It also leads to inappropriate medical practices. For example, many hospitals now check urine cultures on admission in patients with urinary catheters, or obtain blood cultures on asymptomatic patients simply because they have a central line. We know what those kinds of practices lead to nonindicated treatment and overuse of antibiotics.

Aiming for zero separates infection prevention from quality and safety because now, the "be all, end all" becomes an infection-free hospital stay, when maybe that is not the main goal from a patient perspective.

The zero goal also fosters expedient solutions over the hard work of behavior change. A report predicts that, in 2016, the market for infection-control devices and products will be $18 billion – triple that of the market for antibiotics to treat those infections. So there’s a lot of industry out there waiting to get into the market. That in turn contributes to a conflict of interest. Some leading infectious disease associations now have strong sponsorship from these industries that is likely not serving us well.

Aiming for zero also punishes hospitals that care for poor and sicker patients. As an example, in public reporting of hospitals’ infection rates, academic medical centers may appear to have comparatively worse performance.

Finally, if we already know how to get to zero, why would we ever invest any more in research to reduce infections? It really weakens the rationale for funding in the whole field of HAI prevention.

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not a realistic or beneficial goal and may actually produce many unintended negative consequences. Clinicians and patients alike would be better served by a focus on achieving realistic reductions.

Dr. Edmond is the Richard P. Wenzel Professor of Internal Medicine and chair of the infectious diseases division, Virginia Commonwealth University Hospital, and an epidemiologist at the VCU Health System, both in Richmond. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

YES – Eliminating HAIs is feasible and may help better focus prevention efforts.

For many years, research suggested that reducing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) by one-third was the best we could do. But recent landmark efforts, such as the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2005;54:1013-16) and the Michigan Keystone Project (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2725-32), have shattered our notions of how many HAIs might be preventable, achieving reductions of nearly 70% in central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). Similarly, a national campaign in England has achieved a 68% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections (Health Prot. Rep. 2012;6:38).

These new data suggest that possibly all HAIs are preventable, and there are now many published reports in which institutions have reached zero. For example, the Hawaii experience has shown that a prevention initiative achieved a median rate of zero catheter-related bloodstream infections (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9).

The advances in HAI prevention are coming in the context of an ever increasingly sick patient population, with patients who are more complicated than ever before. In fact, many of the greatest gains in CLABSI prevention have been among the very sickest patients in our hospitals – in the intensive care unit – as at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (Crit. Care Med. 2004;32:2014-20). So the rationale that we cannot get to zero because our patients are too sick simply is not relevant anymore.

We won’t know how many HAIs are preventable until we hit the bottom. But if our goal is not zero, we will likely end up accepting some infections that might be preventable. Therefore, we must set the goal at zero infections.

What if we don’t get there? That would suggest that some of these infections might not be related to health care delivery but rather to patient risk factors. And these are the infections that we can target. New research could end up preventing some of them. Modifications in definitions might be necessary to account for some of these infections.

One might then argue that we are just defining our way to zero. I would counter that plenty of places have, in fact, hit zero CLABSIs without any changes in our current definitions. But I will also argue that rational changes in our definitions will be needed to help us differentiate truly preventable HAIs and allow us to better focus our prevention efforts.

An excellent example is the new definition of the mucosal barrier injury–related bloodstream infections, which was discussed during the recent IDWeek. Making such an evidence-based change to a definition to focus prevention efforts is neither gaming nor cheating—it’s called good science and good policy.

The zero goal will also improve medical care through the wider adoption of best practices. Published reports of HAI prevention efforts show the successes have been obtained through the implementation of best practices, not through gaming, not through cheating. Zero HAIs as a goal is already driving real improvements in patient safety and quality.

Pushing for zero HAIs will also further research. How much can we argue for pushing the prevention research envelope if we decide that some of these infections are simply okay? How are we going to argue for funding for more prevention research if we tell them the infections aren’t really preventable? We will be much more successful if it’s clear that we need it to get to zero HAIs.

Getting to zero has been put forth as a goal that we should aim for, not as a standard that people should be punished for in the event it is not attained. In fact, value-based purchasing rules are based on relative infection rates – not on zero infection rates.

Moreover, it’s a long-range goal. This is not something that anyone is advocating for overnight. Evidence of that can be seen in the National Action Plan to Prevent HAIs, which calls for 30%-50% reductions, not zero, as the target for the first 5 years.

It must be acknowledged that sometimes an HAI is someone’s fault. Many U.S. institutions have yet to implement best practices for preventing CLABSIs, for example. How long can we hold these hospitals blameless for failing to do this?

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine, but the only medicine. It is our successes, published in our own medical literature, that have prompted the push to get to zero. We shouldn’t run away from the success that we have had; we should embrace it and build on it. Patients will no longer accept a goal of preventing some HAIs, and neither should we.

Dr. Srinivasan is associate director for health care–associated infection prevention programs, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

NO – Eliminating HAIs is unrealistic and has unintended negative consequences.

There are a variety of reasons why getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine. First and probably most important is that it is dishonest. Patients today are sicker and more immunosuppressed, and the devices we use are ever more invasive. When we have patients in our hospitals who, for example, have total artificial hearts in place for more than a year, can we realistically imagine that there would not be any HAIs? I don’t think so.

Extensive medical literature documenting infection prevention initiatives attests to this. For example, a recent analysis suggests that even if all U.S. hospitals implemented all of the measures known to prevent HAIs, at best 55%-70% of common HAIs would reasonably be preventable (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011;32:101-14). None were found to be 100% preventable.

If one looks closely at the Hawaii experience showing a median rate of zero HAIs, you actually see a 61% reduction in the rate of CLABSIs over 1.5 years, but it never reaches zero (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9). That translates to up to 10 infections per quarter. So we can use words in loose ways and talk about zero median infections, but there were not zero infections in that study. If the final rate of 0.6/1,000 catheter-days were applied to my hospital, it would translate to 11 CLABSIs annually – hardly a number that would allow me to say I had eliminated these infections.

Efforts to achieve zero HAIs may be a manifestation of postmodernism, a philosophical paradigm in which there is no absolute truth, and one that puts evidence-based medicine on par with practices such as homeopathy and the notion that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine causes autism.

Aiming for zero HAIs drives a punitive culture. If we accept the concept of getting to zero, it then means that zero is actually attainable, and if that is true, then all HAIs are preventable. And if that is true, logic tells us then that the occurrence of an HAI must be someone’s fault.

The zero goal places enormous pressure on infection preventionists and their programs, and it creates adversarial relationships between infection prevention services and clinicians as they argue about whether an event is an infection. Hospital administrators ask why programs are not reaching zero. And the infection prevention people are caught in the middle of all this. They are in a terrible position: In some cases, they are deciding – in a way – whether people will get a pay raise or will be fired from their jobs.

Trying to eliminate HAIs fosters problems with surveillance, such as outright cheating, making subtle changes to case definitions that reduce infection rates, and underfunding infection prevention programs to reduce their sensitivity for case ascertainment.

It also leads to inappropriate medical practices. For example, many hospitals now check urine cultures on admission in patients with urinary catheters, or obtain blood cultures on asymptomatic patients simply because they have a central line. We know what those kinds of practices lead to nonindicated treatment and overuse of antibiotics.

Aiming for zero separates infection prevention from quality and safety because now, the "be all, end all" becomes an infection-free hospital stay, when maybe that is not the main goal from a patient perspective.

The zero goal also fosters expedient solutions over the hard work of behavior change. A report predicts that, in 2016, the market for infection-control devices and products will be $18 billion – triple that of the market for antibiotics to treat those infections. So there’s a lot of industry out there waiting to get into the market. That in turn contributes to a conflict of interest. Some leading infectious disease associations now have strong sponsorship from these industries that is likely not serving us well.

Aiming for zero also punishes hospitals that care for poor and sicker patients. As an example, in public reporting of hospitals’ infection rates, academic medical centers may appear to have comparatively worse performance.

Finally, if we already know how to get to zero, why would we ever invest any more in research to reduce infections? It really weakens the rationale for funding in the whole field of HAI prevention.

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not a realistic or beneficial goal and may actually produce many unintended negative consequences. Clinicians and patients alike would be better served by a focus on achieving realistic reductions.

Dr. Edmond is the Richard P. Wenzel Professor of Internal Medicine and chair of the infectious diseases division, Virginia Commonwealth University Hospital, and an epidemiologist at the VCU Health System, both in Richmond. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

YES – Eliminating HAIs is feasible and may help better focus prevention efforts.

For many years, research suggested that reducing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) by one-third was the best we could do. But recent landmark efforts, such as the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2005;54:1013-16) and the Michigan Keystone Project (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2725-32), have shattered our notions of how many HAIs might be preventable, achieving reductions of nearly 70% in central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). Similarly, a national campaign in England has achieved a 68% reduction in Clostridium difficile infections (Health Prot. Rep. 2012;6:38).

These new data suggest that possibly all HAIs are preventable, and there are now many published reports in which institutions have reached zero. For example, the Hawaii experience has shown that a prevention initiative achieved a median rate of zero catheter-related bloodstream infections (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9).

The advances in HAI prevention are coming in the context of an ever increasingly sick patient population, with patients who are more complicated than ever before. In fact, many of the greatest gains in CLABSI prevention have been among the very sickest patients in our hospitals – in the intensive care unit – as at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (Crit. Care Med. 2004;32:2014-20). So the rationale that we cannot get to zero because our patients are too sick simply is not relevant anymore.

We won’t know how many HAIs are preventable until we hit the bottom. But if our goal is not zero, we will likely end up accepting some infections that might be preventable. Therefore, we must set the goal at zero infections.

What if we don’t get there? That would suggest that some of these infections might not be related to health care delivery but rather to patient risk factors. And these are the infections that we can target. New research could end up preventing some of them. Modifications in definitions might be necessary to account for some of these infections.

One might then argue that we are just defining our way to zero. I would counter that plenty of places have, in fact, hit zero CLABSIs without any changes in our current definitions. But I will also argue that rational changes in our definitions will be needed to help us differentiate truly preventable HAIs and allow us to better focus our prevention efforts.

An excellent example is the new definition of the mucosal barrier injury–related bloodstream infections, which was discussed during the recent IDWeek. Making such an evidence-based change to a definition to focus prevention efforts is neither gaming nor cheating—it’s called good science and good policy.

The zero goal will also improve medical care through the wider adoption of best practices. Published reports of HAI prevention efforts show the successes have been obtained through the implementation of best practices, not through gaming, not through cheating. Zero HAIs as a goal is already driving real improvements in patient safety and quality.

Pushing for zero HAIs will also further research. How much can we argue for pushing the prevention research envelope if we decide that some of these infections are simply okay? How are we going to argue for funding for more prevention research if we tell them the infections aren’t really preventable? We will be much more successful if it’s clear that we need it to get to zero HAIs.

Getting to zero has been put forth as a goal that we should aim for, not as a standard that people should be punished for in the event it is not attained. In fact, value-based purchasing rules are based on relative infection rates – not on zero infection rates.

Moreover, it’s a long-range goal. This is not something that anyone is advocating for overnight. Evidence of that can be seen in the National Action Plan to Prevent HAIs, which calls for 30%-50% reductions, not zero, as the target for the first 5 years.

It must be acknowledged that sometimes an HAI is someone’s fault. Many U.S. institutions have yet to implement best practices for preventing CLABSIs, for example. How long can we hold these hospitals blameless for failing to do this?

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine, but the only medicine. It is our successes, published in our own medical literature, that have prompted the push to get to zero. We shouldn’t run away from the success that we have had; we should embrace it and build on it. Patients will no longer accept a goal of preventing some HAIs, and neither should we.

Dr. Srinivasan is associate director for health care–associated infection prevention programs, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

NO – Eliminating HAIs is unrealistic and has unintended negative consequences.

There are a variety of reasons why getting to zero HAIs is not the right medicine. First and probably most important is that it is dishonest. Patients today are sicker and more immunosuppressed, and the devices we use are ever more invasive. When we have patients in our hospitals who, for example, have total artificial hearts in place for more than a year, can we realistically imagine that there would not be any HAIs? I don’t think so.

Extensive medical literature documenting infection prevention initiatives attests to this. For example, a recent analysis suggests that even if all U.S. hospitals implemented all of the measures known to prevent HAIs, at best 55%-70% of common HAIs would reasonably be preventable (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011;32:101-14). None were found to be 100% preventable.

If one looks closely at the Hawaii experience showing a median rate of zero HAIs, you actually see a 61% reduction in the rate of CLABSIs over 1.5 years, but it never reaches zero (Am. J. Med. Qual. 2012;27:124-9). That translates to up to 10 infections per quarter. So we can use words in loose ways and talk about zero median infections, but there were not zero infections in that study. If the final rate of 0.6/1,000 catheter-days were applied to my hospital, it would translate to 11 CLABSIs annually – hardly a number that would allow me to say I had eliminated these infections.

Efforts to achieve zero HAIs may be a manifestation of postmodernism, a philosophical paradigm in which there is no absolute truth, and one that puts evidence-based medicine on par with practices such as homeopathy and the notion that the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine causes autism.

Aiming for zero HAIs drives a punitive culture. If we accept the concept of getting to zero, it then means that zero is actually attainable, and if that is true, then all HAIs are preventable. And if that is true, logic tells us then that the occurrence of an HAI must be someone’s fault.

The zero goal places enormous pressure on infection preventionists and their programs, and it creates adversarial relationships between infection prevention services and clinicians as they argue about whether an event is an infection. Hospital administrators ask why programs are not reaching zero. And the infection prevention people are caught in the middle of all this. They are in a terrible position: In some cases, they are deciding – in a way – whether people will get a pay raise or will be fired from their jobs.

Trying to eliminate HAIs fosters problems with surveillance, such as outright cheating, making subtle changes to case definitions that reduce infection rates, and underfunding infection prevention programs to reduce their sensitivity for case ascertainment.

It also leads to inappropriate medical practices. For example, many hospitals now check urine cultures on admission in patients with urinary catheters, or obtain blood cultures on asymptomatic patients simply because they have a central line. We know what those kinds of practices lead to nonindicated treatment and overuse of antibiotics.

Aiming for zero separates infection prevention from quality and safety because now, the "be all, end all" becomes an infection-free hospital stay, when maybe that is not the main goal from a patient perspective.

The zero goal also fosters expedient solutions over the hard work of behavior change. A report predicts that, in 2016, the market for infection-control devices and products will be $18 billion – triple that of the market for antibiotics to treat those infections. So there’s a lot of industry out there waiting to get into the market. That in turn contributes to a conflict of interest. Some leading infectious disease associations now have strong sponsorship from these industries that is likely not serving us well.

Aiming for zero also punishes hospitals that care for poor and sicker patients. As an example, in public reporting of hospitals’ infection rates, academic medical centers may appear to have comparatively worse performance.

Finally, if we already know how to get to zero, why would we ever invest any more in research to reduce infections? It really weakens the rationale for funding in the whole field of HAI prevention.

In sum, getting to zero HAIs is not a realistic or beneficial goal and may actually produce many unintended negative consequences. Clinicians and patients alike would be better served by a focus on achieving realistic reductions.

Dr. Edmond is the Richard P. Wenzel Professor of Internal Medicine and chair of the infectious diseases division, Virginia Commonwealth University Hospital, and an epidemiologist at the VCU Health System, both in Richmond. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Laparoscopic diverticulitis surgery linked to fewer complications

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients.

Data Source: From 10,085 U.S. patients who had surgery for acute management of complicated diverticulitis during 2005-2009.

Disclosures: Dr. Cornwell said he had no disclosures.

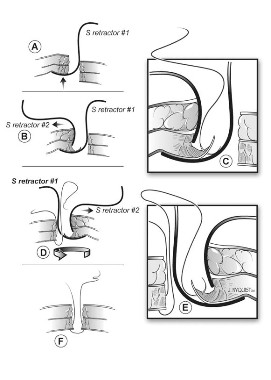

Hysterectomy Trendelenburg position: Less may be more

LAS VEGAS – Significantly reducing the degree of Trendelenburg position during robotic-assisted hysterectomy did not increase operative time and cut blood loss in half in a small retrospective analysis.

Surgeons spent an average of 66.5 minutes (range, 38-110 minutes) at the console when patients were placed in a minimum Trendelenburg position, compared with 79 minutes (range, 30-180 minutes) with a steep Trendelenburg position.

The difference in this primary outcome failed to achieve statistical significance (P = .105); however, the use of a minimum Trendelenburg position significantly reduced the average estimated blood loss from 101.3 mL to 50 mL (P = .007), Dr. Kelli Sasada reported at the 41st AAGL Global Congress.

A minimum degree of Trendelenburg position can be as effective as a steep Trendelenburg position in achieving adequate surgical exposure, thereby allowing safe completion of hysterectomy without increasing operative time, she said.

A steep Trendelenburg position, defined as at least 20 degrees in the anesthesia literature, improves the view of the surgical area during pelvic surgery by taking advantage of gravity to retract the bowels. It is common practice to use this approach during robotic-assisted hysterectomy because the patient’s position cannot conveniently be adjusted once the robot is docked, Dr. Sasada explained.

A steep Trendelenburg position, however, is often fraught with complications that can be severe and permanent, such as neural and retinal injuries, the patient moving or sliding off the table, ventilation concerns including airway access for the anesthesia provider, poor cardiopulmonary status, and alopecia, she added.

To explore the minimum degree of Trendelenburg necessary to complete the surgery safely, Dr. Sasada and her associate, Dr. Linda Mihalov, at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, took advantage of a new iPad app called clinometer HD (by plaincode) among 50 women undergoing da Vinci robotic-assisted benign total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Patients were secured in the dorsal lithotomy position, the abdomen was entered laparoscopically, and a brief survey was conducted to assess the size, position, and accessibility of the pelvic organs. The degree of Trendelenburg was determined by the surgeon and the iPad clinometer HD placed on the bed rail to measure the table tilt. The robot was then docked parallel to the patient’s side, and the surgery completed.

A steep Trendelenburg, defined as 30 degrees, was used in 38 women, and a minimum degree of Trendelenburg averaging 16.6 degrees (range, 13.8-19 degrees) used in 12 women, said Dr. Sasada, now with United Hospital System, St. Catherine’s Medical Center in Pleasant Prairie, Wis.

The average uterine weight was not significantly different between the steep and minimum Trendelenburg groups (215.4 g vs. 173.6 g; P = .21).

Body mass index also was similar at 28.5 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2 (P = .071), with a wide range in both groups, she said.

There was one case of intraoperative bleeding (500 cc) and no postoperative complications in the steep Trendelenburg group, and one case of postoperative urinary retention and no intraoperative complications in the minimum Trendelenburg group.

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Sasada said it’s possible that the lower blood loss with the minimum Trendelenburg position could be due to chance, but that both surgeries were completed with the same four incisions and without bowel prep.

Dr. Sasada currently uses a minimum Trendelenburg position and an iPad when performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy and other pelvic surgeries, but not in all cases, as some OR beds have built-in clinometers. The advantage of the iPad technology is that it offers "ease of use in the OR by anesthesia or nursing staff, and reproducibility between OR beds," she said in an interview.

Dr. Sasada and Dr. Mihalov reported no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Significantly reducing the degree of Trendelenburg position during robotic-assisted hysterectomy did not increase operative time and cut blood loss in half in a small retrospective analysis.

Surgeons spent an average of 66.5 minutes (range, 38-110 minutes) at the console when patients were placed in a minimum Trendelenburg position, compared with 79 minutes (range, 30-180 minutes) with a steep Trendelenburg position.

The difference in this primary outcome failed to achieve statistical significance (P = .105); however, the use of a minimum Trendelenburg position significantly reduced the average estimated blood loss from 101.3 mL to 50 mL (P = .007), Dr. Kelli Sasada reported at the 41st AAGL Global Congress.

A minimum degree of Trendelenburg position can be as effective as a steep Trendelenburg position in achieving adequate surgical exposure, thereby allowing safe completion of hysterectomy without increasing operative time, she said.

A steep Trendelenburg position, defined as at least 20 degrees in the anesthesia literature, improves the view of the surgical area during pelvic surgery by taking advantage of gravity to retract the bowels. It is common practice to use this approach during robotic-assisted hysterectomy because the patient’s position cannot conveniently be adjusted once the robot is docked, Dr. Sasada explained.

A steep Trendelenburg position, however, is often fraught with complications that can be severe and permanent, such as neural and retinal injuries, the patient moving or sliding off the table, ventilation concerns including airway access for the anesthesia provider, poor cardiopulmonary status, and alopecia, she added.

To explore the minimum degree of Trendelenburg necessary to complete the surgery safely, Dr. Sasada and her associate, Dr. Linda Mihalov, at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, took advantage of a new iPad app called clinometer HD (by plaincode) among 50 women undergoing da Vinci robotic-assisted benign total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Patients were secured in the dorsal lithotomy position, the abdomen was entered laparoscopically, and a brief survey was conducted to assess the size, position, and accessibility of the pelvic organs. The degree of Trendelenburg was determined by the surgeon and the iPad clinometer HD placed on the bed rail to measure the table tilt. The robot was then docked parallel to the patient’s side, and the surgery completed.

A steep Trendelenburg, defined as 30 degrees, was used in 38 women, and a minimum degree of Trendelenburg averaging 16.6 degrees (range, 13.8-19 degrees) used in 12 women, said Dr. Sasada, now with United Hospital System, St. Catherine’s Medical Center in Pleasant Prairie, Wis.

The average uterine weight was not significantly different between the steep and minimum Trendelenburg groups (215.4 g vs. 173.6 g; P = .21).

Body mass index also was similar at 28.5 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2 (P = .071), with a wide range in both groups, she said.

There was one case of intraoperative bleeding (500 cc) and no postoperative complications in the steep Trendelenburg group, and one case of postoperative urinary retention and no intraoperative complications in the minimum Trendelenburg group.

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Sasada said it’s possible that the lower blood loss with the minimum Trendelenburg position could be due to chance, but that both surgeries were completed with the same four incisions and without bowel prep.

Dr. Sasada currently uses a minimum Trendelenburg position and an iPad when performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy and other pelvic surgeries, but not in all cases, as some OR beds have built-in clinometers. The advantage of the iPad technology is that it offers "ease of use in the OR by anesthesia or nursing staff, and reproducibility between OR beds," she said in an interview.

Dr. Sasada and Dr. Mihalov reported no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Significantly reducing the degree of Trendelenburg position during robotic-assisted hysterectomy did not increase operative time and cut blood loss in half in a small retrospective analysis.

Surgeons spent an average of 66.5 minutes (range, 38-110 minutes) at the console when patients were placed in a minimum Trendelenburg position, compared with 79 minutes (range, 30-180 minutes) with a steep Trendelenburg position.

The difference in this primary outcome failed to achieve statistical significance (P = .105); however, the use of a minimum Trendelenburg position significantly reduced the average estimated blood loss from 101.3 mL to 50 mL (P = .007), Dr. Kelli Sasada reported at the 41st AAGL Global Congress.

A minimum degree of Trendelenburg position can be as effective as a steep Trendelenburg position in achieving adequate surgical exposure, thereby allowing safe completion of hysterectomy without increasing operative time, she said.

A steep Trendelenburg position, defined as at least 20 degrees in the anesthesia literature, improves the view of the surgical area during pelvic surgery by taking advantage of gravity to retract the bowels. It is common practice to use this approach during robotic-assisted hysterectomy because the patient’s position cannot conveniently be adjusted once the robot is docked, Dr. Sasada explained.

A steep Trendelenburg position, however, is often fraught with complications that can be severe and permanent, such as neural and retinal injuries, the patient moving or sliding off the table, ventilation concerns including airway access for the anesthesia provider, poor cardiopulmonary status, and alopecia, she added.

To explore the minimum degree of Trendelenburg necessary to complete the surgery safely, Dr. Sasada and her associate, Dr. Linda Mihalov, at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, took advantage of a new iPad app called clinometer HD (by plaincode) among 50 women undergoing da Vinci robotic-assisted benign total laparoscopic hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Patients were secured in the dorsal lithotomy position, the abdomen was entered laparoscopically, and a brief survey was conducted to assess the size, position, and accessibility of the pelvic organs. The degree of Trendelenburg was determined by the surgeon and the iPad clinometer HD placed on the bed rail to measure the table tilt. The robot was then docked parallel to the patient’s side, and the surgery completed.

A steep Trendelenburg, defined as 30 degrees, was used in 38 women, and a minimum degree of Trendelenburg averaging 16.6 degrees (range, 13.8-19 degrees) used in 12 women, said Dr. Sasada, now with United Hospital System, St. Catherine’s Medical Center in Pleasant Prairie, Wis.

The average uterine weight was not significantly different between the steep and minimum Trendelenburg groups (215.4 g vs. 173.6 g; P = .21).

Body mass index also was similar at 28.5 kg/m2 vs. 25 kg/m2 (P = .071), with a wide range in both groups, she said.

There was one case of intraoperative bleeding (500 cc) and no postoperative complications in the steep Trendelenburg group, and one case of postoperative urinary retention and no intraoperative complications in the minimum Trendelenburg group.

During a discussion of the study, Dr. Sasada said it’s possible that the lower blood loss with the minimum Trendelenburg position could be due to chance, but that both surgeries were completed with the same four incisions and without bowel prep.

Dr. Sasada currently uses a minimum Trendelenburg position and an iPad when performing robotic-assisted hysterectomy and other pelvic surgeries, but not in all cases, as some OR beds have built-in clinometers. The advantage of the iPad technology is that it offers "ease of use in the OR by anesthesia or nursing staff, and reproducibility between OR beds," she said in an interview.

Dr. Sasada and Dr. Mihalov reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE 41ST AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Major Finding: Average estimated blood loss was 101.3 mL with the steep Trendelenburg position vs. 50 mL with the minimum Trendelenburg (P = .007).

Data Source: Retrospective chart study of 50 women undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy.

Disclosures: Dr. Sasada and Dr. Mihalov reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Ruptured AAA triage to EVAR centers proposed

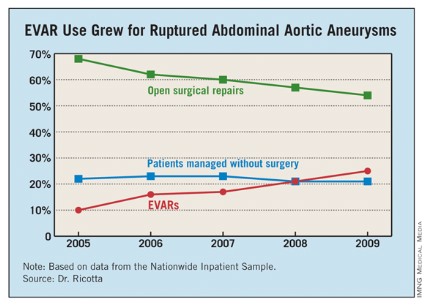

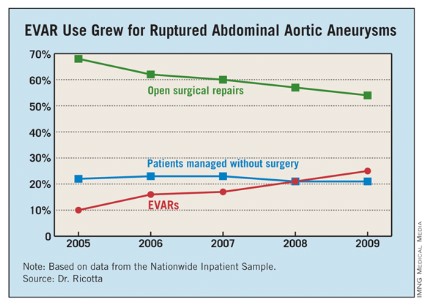

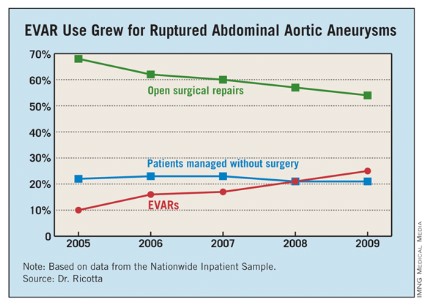

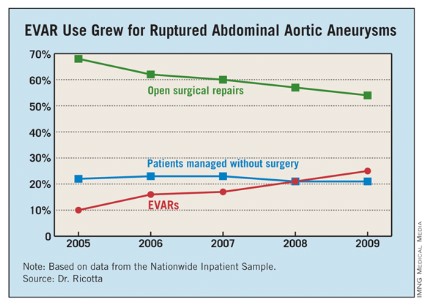

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – The number of U.S. patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms who were managed with endovascular aneurysm repair more than doubled during 2005-2009, suggesting that it’s time to develop a national triage system in order to perform emergency endovascular repairs around the clock, according to Dr. John J. Ricotta.

"A strategy that promotes development of EVAR [endovascular aneurysm repair] centers with triage of stable, EVAR-suitable patients may be the best approach," said Dr. Ricotta, a vascular surgeon and chairman of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

"Regionalization of EVAR services may be practical, along with a triage system to rapidly diagnose and transfer patients with RAAA [ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm]," Dr. Ricotta said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Because the time from the onset of symptoms to the start of successful EVAR repair is often more than 10 hours, stable RAAA patients could be transferred.

"The focus should be on older patients, who are more likely to survive if you do EVAR, and stable patients. Patients who are hemodynamically stable and have good anatomy [for performing EVAR] should go to an EVAR center."

Dr. Ricotta and his associates analyzed data collected from the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all patients aged 60 years or older treated for RAAA during 2005-2009. During the 5-year period, a total of 21,218 patients in the sample underwent treatment for RAAA; 60% of the patients underwent open surgical repair, 22% had no operative repair, and 18% had EVAR.

Use of EVAR rose from 10% of RAAA patients in 2005 to 25% in 2009 (see table). Among the subset of patients who had surgical management, EVAR use rose from 13% of patients in 2005 to 32% in 2009.

EVAR was performed primarily at urban teaching hospitals and in patients under 90. Throughout the 5-year period, EVAR use at urban teaching hospitals included 25% of RAAA patients, compared with 12% of these patients managed at urban nonteaching hospitals and 7% of RAAA patients managed at rural hospitals. About 19% of RAAA patients 60-89 years old underwent EVAR, compared with 12% of those aged 90 or older.

EVAR effectively reduced mortality. Throughout the period studied, the rate of in-hospital mortality was 41% in patients managed with open surgery and 28% in those managed with EVAR, a significant difference, Dr. Ricotta said.

Furthermore, EVAR produced a mortality benefit compared with open surgery across the spectrum of patients, regardless of age. For example, among patients who were at least 90 years old, in-hospital mortality following EVAR was 36%, compared with 77% among patients who had open repair. In a multivariate analysis, EVAR was the only demographic or clinical variable associated with a significant reduction in postoperative in-hospital death, cutting mortality by 47%.

Despite EVAR’s success, use of the technique is limited by the anatomic and physiologic presentation of RAAA patients. "With current technology, EVAR is generally thought to be applicable to 30%-50% of RAAA patients," Dr. Ricotta said. "Experienced centers report the use of EVAR for about 50% of RAAA patients."

Dr. Ricotta called for regionalization and a triage and transfer model, because "widespread adoption of EVAR for RAAA is not practical," he said. "It is an expensive and evolving technology that needs a dedicated staff and a high volume of procedures." An EVAR-first program requires ready CT access and suitable imaging facilities in the operating room, a suitable stock of endografts, and an EVAR team that’s available 24/7, he said.

"Patients who are transferred might do better than patients who are not transferred," agreed Dr. Spence M. Taylor, a vascular surgeon and professor of surgery at the University of South Carolina in Greenville. But he added that patient selection may also play a role. "EVAR does better than open surgical repair in patients who can be stabilized and have this intervention compared with patients who can’t."

Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: From 2005 to 2009, the percentage of hospitalized U.S. patients with a ruptured AAA who underwent EVAR grew from 10% to 25%.

Data Source: The data came from an analysis of 21,218 U.S. patients hospitalized for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm during 2005-2009 and included in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Disclosures: Dr. Ricotta and Dr. Taylor had no disclosures.

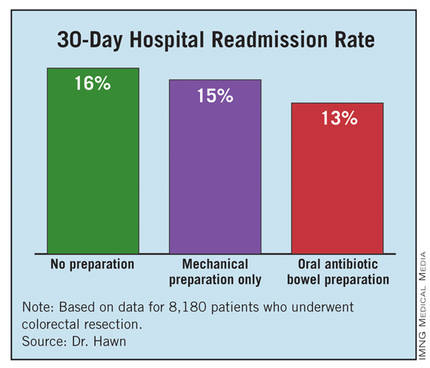

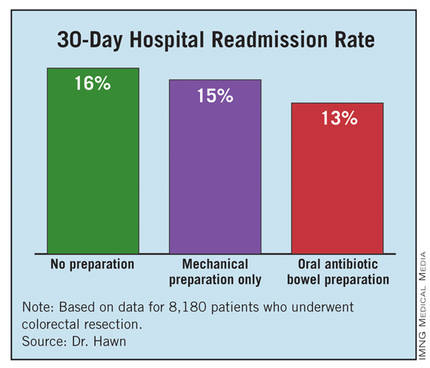

Antibiotic prophylaxis reduces colorectal surgery readmissions

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Administering a brief oral antibiotic regimen preoperatively to colorectal surgery patients cut the average postoperative hospitalization by more than a day and reduced 30-day readmissions by about 3% compared with no presurgical bowel preparation, a review of more than 8,000 patients found.

The primary driver of these beneficial effects was a reduced rate of surgical site infections, Dr. Mary T. Hawn said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"Efforts to improve adherence with the use of oral antibiotic preparation may improve the efficiency of care for colorectal surgery," said Dr. Hawn, chief of gastrointestinal surgery at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. "Further research is needed to determine the best protocol for bowel prep prior to colorectal surgery, and to prospectively monitor the rate of Clostridium difficile infection."

The findings by Dr. Hawn’s group also showed that oral antibiotic bowel preparation (OABP) led to a small but statistically significant increase in the rate of hospital readmissions among patients with a principal diagnostic code of colitis caused by C. difficile infection. The OABP patients had a 0.5% readmission rate, compared with a 0.1% rate among patients who received no presurgical bowel preparation.

The value of OABP as shown in this study is particularly important because the use of OABP before colorectal surgery has declined in the United States over the past 20 years, Dr. Hawn added.

Using data collected as part of the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Dr. Hawn and her colleagues analyzed results for 8,180 patients who underwent elective colorectal resection at any of 112 participating VA hospitals during 2005-2009. Patients who had a partial or total colectomy, a rectal resection, or an ostomy were included. Patients were excluded if they had a preoperative stay of more than 2 days, a postoperative stay of more than 30 days, or an American Surgical Association 5 classification, or if they died before hospital discharge.

Most of the patients (83%) underwent surgery for neoplasms; the next most common reason for surgery was diverticulitis, in 6%. OABP was the most common form of presurgical preparation, used on 44% of patients; mechanical preparation only was used on 39%, and no preparation was done in 17%. Ninety percent of the OABP patients also underwent mechanical preparation, while the other 10% had OABP only.

The average postoperative length of stay was 9.1 days among those who received no preparation, 8.6 days for those who got mechanical preparation only, and 7.9 days for those who had OABP – a statistically significant advantage for OABP. In a multivariate regression analysis that controlled for indication, age, and wound class, OABP cut length of stay by an average of 12% compared with no preparation, a statistically significant reduction. In the same analysis, mechanical preparation cut length of stay by only 4% compared with no preparation, also a significant effect.

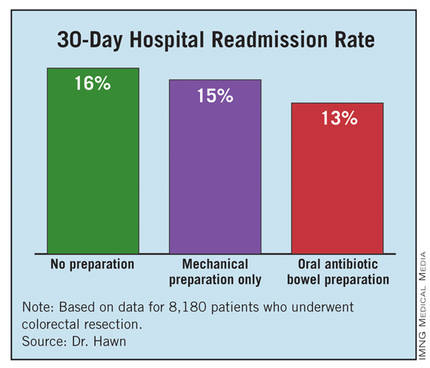

The hospital readmission rate was 16% with no preparation, 15% with mechanical preparation only, and 13% with OABP. In the multivariate regression analysis with adjustment for procedure, age, and wound class, OABP cut the readmission rate by 19% compared with no preparation, a statistically significant reduction. Mechanical preparation only did not have a statistically significant effect.

Further analyses showed that the most common reason for readmission among all patients studied was postoperative infection, in 18%, followed by digestive-system complications, in 10%. C. difficile infection caused 3% of readmissions.

In addition, infections were responsible for readmissions among 6% of patients who underwent no presurgical preparation and in 4% of those who underwent OABP, a statistically significant difference. In contrast, use of OABP produced no statistically significant decline in noninfectious causes of readmission. This rate ran 10% among patients with no preparation, and 9% in patients who underwent OABP.

Dr. Hawn said that she had no disclosures.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) remain a vexing problem despite the significant efforts by hospitals to increase compliance with measures of the Surgical Care Improvement Project. These efforts have so far failed to translate into improved outcomes. We need to identify additional processes that can be changed to improve surgical outcomes.

Elizabeth C. Wick |

At Johns Hopkins, we addressed SSIs by implementing the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program for patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Interventions included standardization of skin preparation, administration of preoperative chlorhexidine showers, selective elimination of mechanical bowel preparation, warming of patients in the preanesthesia area, adoption of enhanced sterile techniques for skin and fascial closure, and addressing previously unrecognized lapses in antibiotic prophylaxis. The program was modeled on ICU processes designed to prevent central line bloodstream infections.

Our program improved the operating room culture by engaging and empowering front-line staff to address deficits and improve processes. A recent review of the rate of SSIs during the 12 months prior to and the 12 months after implementation of this program found that infection rates fell from 27% before implementation to 18% afterward – a 33% relative decrease (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012;215:193-200).

We are expanding this program to colon surgery programs at more than 100 U.S. hospitals. Hospitals want to institute new processes proven to improve patient outcomes. The report by Dr. Hawn and her associates is an important step toward identifying a new approach that might further reduce SSIs.

Dr. Elizabeth C. Wick is a colorectal surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. She had no disclosures. She made these comments as a designated discussant for Dr. Hawn’s report.