User login

Man Is Alarmed by Skin Lesions

ANSWER

The correct answer is eruptive xanthomata (choice “b”) caused by an accumulation of lipid-filled macrophages as a result of pathologic levels of serum triglyceride—a situation discussed more fully below.

Neurofibromatosis type I (choice “a”), also known as von Recklinghausen disease, can present with multiple intradermal nodules. However, it usually appears in the second or third decade of life, with lesions that are fixed and soft. Biopsy would have confirmed this diagnosis.

Diabetic dermopathy (choice “c”) manifests with atrophic patches on anterior tibial skin. The patches occasionally become superficially eroded but do not resemble this patient’s lesions at all.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (choice “d”) usually presents on children as a solitary yellowish brown papule. It can resemble eruptive xanthomata histologically but not clinically.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthomata (EX) are relatively common, manifesting rapidly as papules and nodules, most frequently in the setting of hypertriglyceridemia. The latter can be familial and may be worsened by poorly controlled diabetes. Persons with Fredrickson types I, IV, and V hyperlipidemia are especially prone to EX.

As might be expected, patients with EX are at risk for several associated morbidities, including acute pancreatitis (especially in childhood cases) and atherosclerotic vessel disease. EX have also been associated with hypothyroid states and nephrotic syndromes.

Elevations in cholesterol, with normal triglyceride levels, can be associated with several types of xanthoma, including plane xanthomas and xanthelasma. The latter, often benign, can manifest in a normolipemic patient as well (necessitating a problem-directed history, physical, and lipid check).

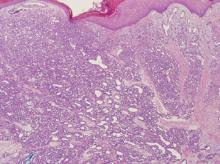

Biopsy is often required to confirm the diagnosis of EX. As in this case, it typically shows monotonous collections of lipid-laden macrophages. Frozen sections of EX can be successfully stained for lipids, but routine processing of specimens effectively removes any lipids, replacing them with paraffin.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails controlling lipids with medication (fenofibrate), diet, and exercise and getting diabetes under control, as indicated. It is also essential to assess for atherosclerotic vessel disease and rule out pancreatitis.

Within a month of institution of treatment, this patient’s lesions had all but disappeared. His serum amylase and lipase were within normal limits, and testing for atherosclerotic vessel disease was pending.

Click here for more DermaDiagnosis cases, including

• The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

• A Purplish Rash on the Instep

• Hair Loss at a Very Young Age.

ANSWER

The correct answer is eruptive xanthomata (choice “b”) caused by an accumulation of lipid-filled macrophages as a result of pathologic levels of serum triglyceride—a situation discussed more fully below.

Neurofibromatosis type I (choice “a”), also known as von Recklinghausen disease, can present with multiple intradermal nodules. However, it usually appears in the second or third decade of life, with lesions that are fixed and soft. Biopsy would have confirmed this diagnosis.

Diabetic dermopathy (choice “c”) manifests with atrophic patches on anterior tibial skin. The patches occasionally become superficially eroded but do not resemble this patient’s lesions at all.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (choice “d”) usually presents on children as a solitary yellowish brown papule. It can resemble eruptive xanthomata histologically but not clinically.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthomata (EX) are relatively common, manifesting rapidly as papules and nodules, most frequently in the setting of hypertriglyceridemia. The latter can be familial and may be worsened by poorly controlled diabetes. Persons with Fredrickson types I, IV, and V hyperlipidemia are especially prone to EX.

As might be expected, patients with EX are at risk for several associated morbidities, including acute pancreatitis (especially in childhood cases) and atherosclerotic vessel disease. EX have also been associated with hypothyroid states and nephrotic syndromes.

Elevations in cholesterol, with normal triglyceride levels, can be associated with several types of xanthoma, including plane xanthomas and xanthelasma. The latter, often benign, can manifest in a normolipemic patient as well (necessitating a problem-directed history, physical, and lipid check).

Biopsy is often required to confirm the diagnosis of EX. As in this case, it typically shows monotonous collections of lipid-laden macrophages. Frozen sections of EX can be successfully stained for lipids, but routine processing of specimens effectively removes any lipids, replacing them with paraffin.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails controlling lipids with medication (fenofibrate), diet, and exercise and getting diabetes under control, as indicated. It is also essential to assess for atherosclerotic vessel disease and rule out pancreatitis.

Within a month of institution of treatment, this patient’s lesions had all but disappeared. His serum amylase and lipase were within normal limits, and testing for atherosclerotic vessel disease was pending.

Click here for more DermaDiagnosis cases, including

• The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

• A Purplish Rash on the Instep

• Hair Loss at a Very Young Age.

ANSWER

The correct answer is eruptive xanthomata (choice “b”) caused by an accumulation of lipid-filled macrophages as a result of pathologic levels of serum triglyceride—a situation discussed more fully below.

Neurofibromatosis type I (choice “a”), also known as von Recklinghausen disease, can present with multiple intradermal nodules. However, it usually appears in the second or third decade of life, with lesions that are fixed and soft. Biopsy would have confirmed this diagnosis.

Diabetic dermopathy (choice “c”) manifests with atrophic patches on anterior tibial skin. The patches occasionally become superficially eroded but do not resemble this patient’s lesions at all.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (choice “d”) usually presents on children as a solitary yellowish brown papule. It can resemble eruptive xanthomata histologically but not clinically.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthomata (EX) are relatively common, manifesting rapidly as papules and nodules, most frequently in the setting of hypertriglyceridemia. The latter can be familial and may be worsened by poorly controlled diabetes. Persons with Fredrickson types I, IV, and V hyperlipidemia are especially prone to EX.

As might be expected, patients with EX are at risk for several associated morbidities, including acute pancreatitis (especially in childhood cases) and atherosclerotic vessel disease. EX have also been associated with hypothyroid states and nephrotic syndromes.

Elevations in cholesterol, with normal triglyceride levels, can be associated with several types of xanthoma, including plane xanthomas and xanthelasma. The latter, often benign, can manifest in a normolipemic patient as well (necessitating a problem-directed history, physical, and lipid check).

Biopsy is often required to confirm the diagnosis of EX. As in this case, it typically shows monotonous collections of lipid-laden macrophages. Frozen sections of EX can be successfully stained for lipids, but routine processing of specimens effectively removes any lipids, replacing them with paraffin.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails controlling lipids with medication (fenofibrate), diet, and exercise and getting diabetes under control, as indicated. It is also essential to assess for atherosclerotic vessel disease and rule out pancreatitis.

Within a month of institution of treatment, this patient’s lesions had all but disappeared. His serum amylase and lipase were within normal limits, and testing for atherosclerotic vessel disease was pending.

Click here for more DermaDiagnosis cases, including

• The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

• A Purplish Rash on the Instep

• Hair Loss at a Very Young Age.

Although they are unaccompanied by any other symptoms, this man is understandably alarmed by the extensive lesions covering much of his body. They first appeared months ago but have become more numerous, larger, and more prominent with time. The patient’s history includes type 2 diabetes (often poorly controlled) and dyslipidemia, for which he takes fenofibrate. Several years ago, he experienced a similar skin outbreak, which resolved after the patient increased his exercise and gained better control of his blood glucose. The condition is striking. There are widespread bilateral collections of shallow intradermal papules, nodules, and plaques primarily on the extensor surfaces of the patient’s arms, legs, and thighs and the convex surfaces of his buttocks. Numbering into the hundreds, the lesions spare his palms, soles, face, and scalp. No abnormality of the periocular skin is appreciated. Moderately firm on palpation, the lesions range in size from 1 to 3 cm in diameter. In several locations, they are linearly configured. A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of them shows large numbers of foamy macrophages in the epidermis and upper dermis. Bloodwork reveals a triglyceride level of 3,850 mg/dL.

Generalized Yellow Discoloration of the Skin

The Diagnosis: Carotenemia

Laboratory parameters including thyroid function testing as well as total protein and bilirubin levels were within reference range. Testing revealed multiple food allergies to almonds, oranges, cashews, garlic, peanuts, and cantaloupe. The patient was treated with a dietary expansion based on his allergy testing.

ß-Carotene converts to vitamin A in the intestine and acts as a lipochrome. Lack of conversion can be noted as an inborn error of metabolism.1 Many green, yellow, and orange fruits and vegetables contain ß-carotene, including carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, green beans, papayas, and pumpkins.1-3 ß-Carotene also is used as a vitamin supplement4 or therapeutic agent in photosensitive disorders such as genetic porphyrias.5

ß-Carotene can accumulate in the stratum corneum and impart a yellow color to the skin when the circulating levels are high; this coloration is termed carotenemia.1,4 Carotenemia is common in infants and young children who have diets rich in green and orange vegetable purees.6 Carotenemia limited to thick areas of the skin, such as the palms and soles, can be seen in adults who eat large amounts of carrots; generalized carotenemia is rare.1,4

Carotenemia is a benign condition of excess cutaneous buildup of ß-carotene through excessive intake of carotene-rich foods1-4 or nutritional supplements7 or through association with anorexia, liver disease, renal disease, hypothyroidism, or diabetes mellitus.1,4,8,9 Carotene deposits usually are most notable in areas with thick stratum corneum, such as the nasolabial folds, palms, and soles, as opposed to areas such as the conjunctivae and mucosa.1,4

Carotenemia may mimic jaundice and should be differentiated through scleral examination for icterus and bilirubin levels. Carotene levels can be tested but generally are unnecessary. Carotenemia can be seen in liver or renal disease and can exacerbate the yellow coloration seen in jaundiced individuals.1,4,9

Because it is a benign condition, the pathology usually is limited to skin discoloration, as seen in our patient. Although this condition can be reversed with a modified diet, our patient had multiple food allergies that further restricted his vegetarian diet, thereby limiting the modifications that he was willing to make to his diet.

1. Schwartz RA. Carotenemia. Emedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104368-overview. Updated April 8, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2014.

2. Sale TA, Stratman E. Carotenemia associated with green bean ingestion. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:657-659.

3. Costanza DJ. Carotenemia associated with papaya ingestion. Calif Med. 1968;109:319-320.

4. Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

5. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

6. Karthik SV, Campbell-Davidson D, Isherwood D. Carotenemia in infancy and its association with prevalent feeding practices. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:571-573.

7. Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Hamamoto Y, et al. A case of carotenemia associated with ingestion of nutrient supplements. J Dermatol. 2006;2:132-134.

8. Thibault L, Roberge AG. The nutritional status of subjects with nervosa. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1987;57:447-452.

9. Matthews-Roth M, Gulbrandsen CL. Transport of beta-carotene in serum of individuals with carotenemia. Clin Chem. 1974;20:1578-1579.

The Diagnosis: Carotenemia

Laboratory parameters including thyroid function testing as well as total protein and bilirubin levels were within reference range. Testing revealed multiple food allergies to almonds, oranges, cashews, garlic, peanuts, and cantaloupe. The patient was treated with a dietary expansion based on his allergy testing.

ß-Carotene converts to vitamin A in the intestine and acts as a lipochrome. Lack of conversion can be noted as an inborn error of metabolism.1 Many green, yellow, and orange fruits and vegetables contain ß-carotene, including carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, green beans, papayas, and pumpkins.1-3 ß-Carotene also is used as a vitamin supplement4 or therapeutic agent in photosensitive disorders such as genetic porphyrias.5

ß-Carotene can accumulate in the stratum corneum and impart a yellow color to the skin when the circulating levels are high; this coloration is termed carotenemia.1,4 Carotenemia is common in infants and young children who have diets rich in green and orange vegetable purees.6 Carotenemia limited to thick areas of the skin, such as the palms and soles, can be seen in adults who eat large amounts of carrots; generalized carotenemia is rare.1,4

Carotenemia is a benign condition of excess cutaneous buildup of ß-carotene through excessive intake of carotene-rich foods1-4 or nutritional supplements7 or through association with anorexia, liver disease, renal disease, hypothyroidism, or diabetes mellitus.1,4,8,9 Carotene deposits usually are most notable in areas with thick stratum corneum, such as the nasolabial folds, palms, and soles, as opposed to areas such as the conjunctivae and mucosa.1,4

Carotenemia may mimic jaundice and should be differentiated through scleral examination for icterus and bilirubin levels. Carotene levels can be tested but generally are unnecessary. Carotenemia can be seen in liver or renal disease and can exacerbate the yellow coloration seen in jaundiced individuals.1,4,9

Because it is a benign condition, the pathology usually is limited to skin discoloration, as seen in our patient. Although this condition can be reversed with a modified diet, our patient had multiple food allergies that further restricted his vegetarian diet, thereby limiting the modifications that he was willing to make to his diet.

The Diagnosis: Carotenemia

Laboratory parameters including thyroid function testing as well as total protein and bilirubin levels were within reference range. Testing revealed multiple food allergies to almonds, oranges, cashews, garlic, peanuts, and cantaloupe. The patient was treated with a dietary expansion based on his allergy testing.

ß-Carotene converts to vitamin A in the intestine and acts as a lipochrome. Lack of conversion can be noted as an inborn error of metabolism.1 Many green, yellow, and orange fruits and vegetables contain ß-carotene, including carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, green beans, papayas, and pumpkins.1-3 ß-Carotene also is used as a vitamin supplement4 or therapeutic agent in photosensitive disorders such as genetic porphyrias.5

ß-Carotene can accumulate in the stratum corneum and impart a yellow color to the skin when the circulating levels are high; this coloration is termed carotenemia.1,4 Carotenemia is common in infants and young children who have diets rich in green and orange vegetable purees.6 Carotenemia limited to thick areas of the skin, such as the palms and soles, can be seen in adults who eat large amounts of carrots; generalized carotenemia is rare.1,4

Carotenemia is a benign condition of excess cutaneous buildup of ß-carotene through excessive intake of carotene-rich foods1-4 or nutritional supplements7 or through association with anorexia, liver disease, renal disease, hypothyroidism, or diabetes mellitus.1,4,8,9 Carotene deposits usually are most notable in areas with thick stratum corneum, such as the nasolabial folds, palms, and soles, as opposed to areas such as the conjunctivae and mucosa.1,4

Carotenemia may mimic jaundice and should be differentiated through scleral examination for icterus and bilirubin levels. Carotene levels can be tested but generally are unnecessary. Carotenemia can be seen in liver or renal disease and can exacerbate the yellow coloration seen in jaundiced individuals.1,4,9

Because it is a benign condition, the pathology usually is limited to skin discoloration, as seen in our patient. Although this condition can be reversed with a modified diet, our patient had multiple food allergies that further restricted his vegetarian diet, thereby limiting the modifications that he was willing to make to his diet.

1. Schwartz RA. Carotenemia. Emedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104368-overview. Updated April 8, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2014.

2. Sale TA, Stratman E. Carotenemia associated with green bean ingestion. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:657-659.

3. Costanza DJ. Carotenemia associated with papaya ingestion. Calif Med. 1968;109:319-320.

4. Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

5. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

6. Karthik SV, Campbell-Davidson D, Isherwood D. Carotenemia in infancy and its association with prevalent feeding practices. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:571-573.

7. Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Hamamoto Y, et al. A case of carotenemia associated with ingestion of nutrient supplements. J Dermatol. 2006;2:132-134.

8. Thibault L, Roberge AG. The nutritional status of subjects with nervosa. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1987;57:447-452.

9. Matthews-Roth M, Gulbrandsen CL. Transport of beta-carotene in serum of individuals with carotenemia. Clin Chem. 1974;20:1578-1579.

1. Schwartz RA. Carotenemia. Emedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104368-overview. Updated April 8, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2014.

2. Sale TA, Stratman E. Carotenemia associated with green bean ingestion. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:657-659.

3. Costanza DJ. Carotenemia associated with papaya ingestion. Calif Med. 1968;109:319-320.

4. Lascari AD. Carotenemia. a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:25-29.

5. Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924-937.

6. Karthik SV, Campbell-Davidson D, Isherwood D. Carotenemia in infancy and its association with prevalent feeding practices. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:571-573.

7. Takita Y, Ichimiya M, Hamamoto Y, et al. A case of carotenemia associated with ingestion of nutrient supplements. J Dermatol. 2006;2:132-134.

8. Thibault L, Roberge AG. The nutritional status of subjects with nervosa. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1987;57:447-452.

9. Matthews-Roth M, Gulbrandsen CL. Transport of beta-carotene in serum of individuals with carotenemia. Clin Chem. 1974;20:1578-1579.

A 50-year-old man presented with yellow, pruritic, xerotic skin and lethargy. The patient also reported nasal congestion and sneezing, especially when eating peanuts. He was fearful of allergic reactions and restricted his diet to “safe foods” such as squash, green beans, and sweet potatoes. On examination the patient had marked generalized yellow discoloration of the skin with pale mucous membranes, nonicteric sclerae, infraocular violaceous and hyperpigmented skin (allergic shiners), and Dennie-Morgan folds.

Pruritus and Hyperpigmented Streaks

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple linear, flagellate, and hyperpigmented plaques on the trunk. Similar lesions were seen on the upper and lower extremities. Given the patient's history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and concurrent chemotherapy, the use of systemic steroids was avoided. Notable improvement in the symptoms was achieved with topical steroids (triamcinolone acetonide ointment) under occlusion and systemic gabapentin. The patient's chemotherapy is ongoing. This characteristic skin eruption often is seen after treatment with systemic bleomycin sulfate.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation following systemic bleomycin sulfate use as a chemotherapeutic agent is a well-known cutaneous reaction that occurs in approximately 10% of exposed individuals.1 Bleomycin sulfate, an antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is a commonly used antitumor agent for both hematologic and solid-organ malignancies.2 Many patients develop generalized pruritus within several days after initiating bleomycin sulfate, followed by the characteristic linear and hyperpigmented streaks. The exact mechanism of this characteristic rash is unknown. Suggested pathways include induction of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, postinflammatory pigmentary incontinence, and altered levels of melanin due to a toxic effect of the medication. Other commonly reported adverse events to bleomycin sulfate include alopecia and stomatitis.3

Although a diffuse rash is the most commonly reported cutaneous reaction to systemic bleomycin sulfate, there have been reports of hyperpigmentation only in areas of pressure and palmar creases. Tsuji and Sawabe4 reported a case of hyperpigmentation limited to areas of striae distensae after systemic bleomycin sulfate. Flagellate hyperpigmentation also has been reported following intralesional bleomycin sulfate for the treatment of verruca plantaris. In that case, the patient had received 14 U of intralesional bleomycin sulfate injected at different sites of recalcitrant verruca and developed urticaria, generalized pruritus, and flagellate hyperpigmentation.5

Treatment of flagellate hyperpigmentation includes cessation of the medication, which is not always possible due to the need for an effective chemotherapeutic regimen. Most cases are reversible following discontinuation of bleomycin sulfate, and care is directed at symptom relief with antipruritic agents, antihistamines, systemic steroids, or topical steroids.3

1. Watanabe T, Tsuchida T. 'Flagellate' erythema in dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 1995;190:230-231.

2. Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an antitumor antibiotic. clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

3. Susser WS, Whitaker-Worth DL, Grant-Kels JM. Mucocutaneous reactions to chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:367-398; quiz 399-400.

4. Tsuji T, Sawabe M. Hyperpigmentation in striae distensae after bleomycin treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:503-505.

5. Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple linear, flagellate, and hyperpigmented plaques on the trunk. Similar lesions were seen on the upper and lower extremities. Given the patient's history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and concurrent chemotherapy, the use of systemic steroids was avoided. Notable improvement in the symptoms was achieved with topical steroids (triamcinolone acetonide ointment) under occlusion and systemic gabapentin. The patient's chemotherapy is ongoing. This characteristic skin eruption often is seen after treatment with systemic bleomycin sulfate.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation following systemic bleomycin sulfate use as a chemotherapeutic agent is a well-known cutaneous reaction that occurs in approximately 10% of exposed individuals.1 Bleomycin sulfate, an antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is a commonly used antitumor agent for both hematologic and solid-organ malignancies.2 Many patients develop generalized pruritus within several days after initiating bleomycin sulfate, followed by the characteristic linear and hyperpigmented streaks. The exact mechanism of this characteristic rash is unknown. Suggested pathways include induction of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, postinflammatory pigmentary incontinence, and altered levels of melanin due to a toxic effect of the medication. Other commonly reported adverse events to bleomycin sulfate include alopecia and stomatitis.3

Although a diffuse rash is the most commonly reported cutaneous reaction to systemic bleomycin sulfate, there have been reports of hyperpigmentation only in areas of pressure and palmar creases. Tsuji and Sawabe4 reported a case of hyperpigmentation limited to areas of striae distensae after systemic bleomycin sulfate. Flagellate hyperpigmentation also has been reported following intralesional bleomycin sulfate for the treatment of verruca plantaris. In that case, the patient had received 14 U of intralesional bleomycin sulfate injected at different sites of recalcitrant verruca and developed urticaria, generalized pruritus, and flagellate hyperpigmentation.5

Treatment of flagellate hyperpigmentation includes cessation of the medication, which is not always possible due to the need for an effective chemotherapeutic regimen. Most cases are reversible following discontinuation of bleomycin sulfate, and care is directed at symptom relief with antipruritic agents, antihistamines, systemic steroids, or topical steroids.3

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Hyperpigmentation

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple linear, flagellate, and hyperpigmented plaques on the trunk. Similar lesions were seen on the upper and lower extremities. Given the patient's history of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and concurrent chemotherapy, the use of systemic steroids was avoided. Notable improvement in the symptoms was achieved with topical steroids (triamcinolone acetonide ointment) under occlusion and systemic gabapentin. The patient's chemotherapy is ongoing. This characteristic skin eruption often is seen after treatment with systemic bleomycin sulfate.

Flagellate hyperpigmentation following systemic bleomycin sulfate use as a chemotherapeutic agent is a well-known cutaneous reaction that occurs in approximately 10% of exposed individuals.1 Bleomycin sulfate, an antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is a commonly used antitumor agent for both hematologic and solid-organ malignancies.2 Many patients develop generalized pruritus within several days after initiating bleomycin sulfate, followed by the characteristic linear and hyperpigmented streaks. The exact mechanism of this characteristic rash is unknown. Suggested pathways include induction of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, postinflammatory pigmentary incontinence, and altered levels of melanin due to a toxic effect of the medication. Other commonly reported adverse events to bleomycin sulfate include alopecia and stomatitis.3

Although a diffuse rash is the most commonly reported cutaneous reaction to systemic bleomycin sulfate, there have been reports of hyperpigmentation only in areas of pressure and palmar creases. Tsuji and Sawabe4 reported a case of hyperpigmentation limited to areas of striae distensae after systemic bleomycin sulfate. Flagellate hyperpigmentation also has been reported following intralesional bleomycin sulfate for the treatment of verruca plantaris. In that case, the patient had received 14 U of intralesional bleomycin sulfate injected at different sites of recalcitrant verruca and developed urticaria, generalized pruritus, and flagellate hyperpigmentation.5

Treatment of flagellate hyperpigmentation includes cessation of the medication, which is not always possible due to the need for an effective chemotherapeutic regimen. Most cases are reversible following discontinuation of bleomycin sulfate, and care is directed at symptom relief with antipruritic agents, antihistamines, systemic steroids, or topical steroids.3

1. Watanabe T, Tsuchida T. 'Flagellate' erythema in dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 1995;190:230-231.

2. Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an antitumor antibiotic. clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

3. Susser WS, Whitaker-Worth DL, Grant-Kels JM. Mucocutaneous reactions to chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:367-398; quiz 399-400.

4. Tsuji T, Sawabe M. Hyperpigmentation in striae distensae after bleomycin treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:503-505.

5. Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

1. Watanabe T, Tsuchida T. 'Flagellate' erythema in dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 1995;190:230-231.

2. Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an antitumor antibiotic. clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

3. Susser WS, Whitaker-Worth DL, Grant-Kels JM. Mucocutaneous reactions to chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:367-398; quiz 399-400.

4. Tsuji T, Sawabe M. Hyperpigmentation in striae distensae after bleomycin treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:503-505.

5. Abess A, Keel DM, Graham BS. Flagellate hyperpigmentation following intralesional bleomycin treatment of verruca plantaris. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:337-339.

A 57-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread pruritic rash. The patient had a recent diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and was currently undergoing chemotherapy with adriamycin, bleomycin sulfate, vinblastine sulfate, and dacarbazine. The patient’s medical history included hypertension, which was well controlled, and a remote history of a stroke. The patient stated that the rash was recurrent and developed a few days after each dose of bleomycin. Review of systems was otherwise unremarkable, except for pruritus.

Inmate Falls From Top Bunk

ANSWER

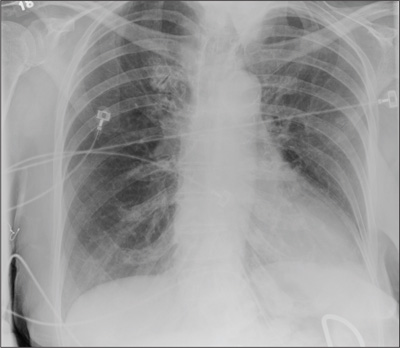

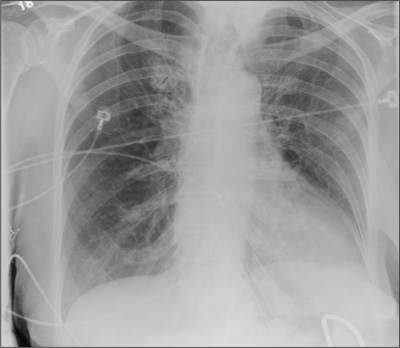

The radiograph demonstrates no acute osseous injury, such as fracture or dislocation. Of interest and note is increased sclerosis within both femoral heads, more so on the left versus the right side. Given the patient’s young age, such findings could be related to early avascular necrosis. His clinical symptoms certainly correlate. MRI or bone scan, as well as orthopedic evaluation, is warranted in such a case.

Fortunately, subsequent MRI of both hips did not show any avascular necrosis but rather osteoarthritic changes. The MRI of his spinal column was negative as well.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no acute osseous injury, such as fracture or dislocation. Of interest and note is increased sclerosis within both femoral heads, more so on the left versus the right side. Given the patient’s young age, such findings could be related to early avascular necrosis. His clinical symptoms certainly correlate. MRI or bone scan, as well as orthopedic evaluation, is warranted in such a case.

Fortunately, subsequent MRI of both hips did not show any avascular necrosis but rather osteoarthritic changes. The MRI of his spinal column was negative as well.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no acute osseous injury, such as fracture or dislocation. Of interest and note is increased sclerosis within both femoral heads, more so on the left versus the right side. Given the patient’s young age, such findings could be related to early avascular necrosis. His clinical symptoms certainly correlate. MRI or bone scan, as well as orthopedic evaluation, is warranted in such a case.

Fortunately, subsequent MRI of both hips did not show any avascular necrosis but rather osteoarthritic changes. The MRI of his spinal column was negative as well.

A 30-year-old man is transferred to your facility for evaluation of reported paraplegia after a fall. The patient is an inmate at a local prison. He states he was sleeping on the top bunk when he rolled over and fell off the bed, landing flat on his back on the concrete floor. He immediately started having severe back and hip pain and noticed that he could not move his legs. His primary complaint is severe bilateral hip pain. He was initially evaluated at an outside hospital, where CT of his head, cervical spine, and lumbar spine was negative for any acute pathology. He was sent to your facility for an MRI to rule out contusion or acute herniated disc. The patient denies any significant medical history, including back trauma. Currently, he reports no bowel/bladder issues or saddle anesthesia. On initial exam, he is awake, alert, and oriented, with normal vital signs. Musculoskeletal exam demonstrates a moderate amount of paraspinous tenderness and bilateral hip/pelvis tenderness. There is no instability detected, nor any leg shortening or rotation. He does have bilateral weakness in both lower extremities on the magnitude of 3-/5, although his exam seems limited due to the severity of his hip pain. Sensation is completely intact in both lower extremities. While the patient is awaiting his MRI, you order a portable pelvis radiograph, since none was performed at the outside facility. What is your impression?

Healthy and Active, but Getting Fatigued

ANSWER

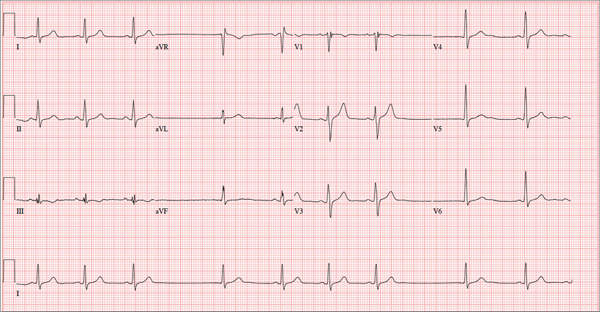

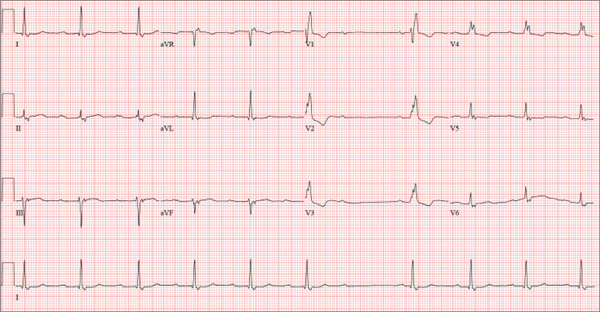

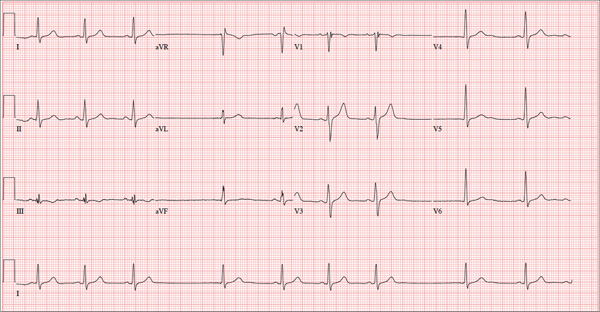

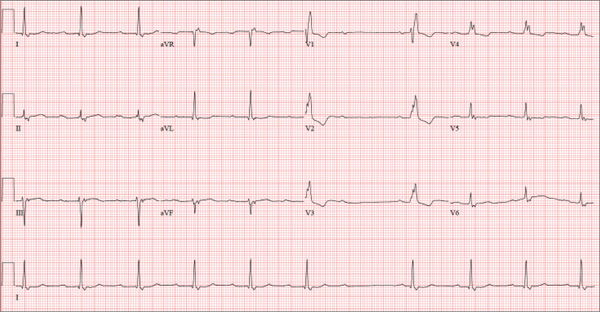

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus bradycardia with marked sinus arrhythmia and junctional escape beats with sinus arrest. An intraventricular conduction defect is also present.

Sinus bradycardia is indicated by the normal PQRST complexes at a rate of less than 60 beats/min. A marked sinus arrhythmia is evidenced by more than one pause (between third and fourth beats and seventh and eighth beats on the lead I rhythm strip) on the ECG.

Sinus arrest occurs when the sinus node fails to conduct (absence of P wave during the interval of the pause). A normal QRS complex without a preceding P wave indicates a junctional escape beat. Finally, an intraventricular conduction defect is documented by a QRS duration ≥ 110 ms in the absence of a right or left bundle branch block.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus bradycardia with marked sinus arrhythmia and junctional escape beats with sinus arrest. An intraventricular conduction defect is also present.

Sinus bradycardia is indicated by the normal PQRST complexes at a rate of less than 60 beats/min. A marked sinus arrhythmia is evidenced by more than one pause (between third and fourth beats and seventh and eighth beats on the lead I rhythm strip) on the ECG.

Sinus arrest occurs when the sinus node fails to conduct (absence of P wave during the interval of the pause). A normal QRS complex without a preceding P wave indicates a junctional escape beat. Finally, an intraventricular conduction defect is documented by a QRS duration ≥ 110 ms in the absence of a right or left bundle branch block.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus bradycardia with marked sinus arrhythmia and junctional escape beats with sinus arrest. An intraventricular conduction defect is also present.

Sinus bradycardia is indicated by the normal PQRST complexes at a rate of less than 60 beats/min. A marked sinus arrhythmia is evidenced by more than one pause (between third and fourth beats and seventh and eighth beats on the lead I rhythm strip) on the ECG.

Sinus arrest occurs when the sinus node fails to conduct (absence of P wave during the interval of the pause). A normal QRS complex without a preceding P wave indicates a junctional escape beat. Finally, an intraventricular conduction defect is documented by a QRS duration ≥ 110 ms in the absence of a right or left bundle branch block.

A 68-year-old retired high school teacher became fatigued while doing yardwork. After sitting down to rest, he noticed that his heart seemed to be skipping beats. He asked his daughter, a pediatric nurse, to come over and check his pulse. She confirmed his suspicion and recommended he go to the emergency department. The patient refused but made an appointment to see his primary care provider. Since you are covering for his usual provider (who is on maternity leave), the patient presents to you. Review of his chart indicates that he has been healthy and active his entire life and has never had any cardiac issues. He does not have hypertension, diabetes, hypothyroidism, or pulmonary problems. His history includes GERD, kidney stones, hyperlipidemia, and a fractured left clavicle. All immunizations and tetanus booster are current. The patient denies any history of chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, near-syncope, palpitations, or other heart rhythm issues (eg, tachycardia, bradycardia, or atrial fibrillation). His last ECG, performed three years ago during a routine visit, showed normal sinus rhythm with normal intervals and no evidence of chamber enlargement; hypertrophy; arrhythmia; P, QRS, or QT interval abnormalities; or blocks. His current medications include esomeprazole magnesium, simvastatin, niacin, and aspirin. He denies illicit or homeopathic drug use and has no known drug allergies. He is a widower who does not drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 108/58 mm Hg; pulse, 60 beats/min with occasional pauses; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 98% on room air; and temperature, 98.9°F. His weight is 169 lb and his height, 74 in. Physical exam reveals a tall, thin, healthy-appearing male in no distress. The HEENT exam is remarkable only for corrective lenses. There is no thyromegaly, jugular venous distention, or lymphadenopathy. The lungs are clear in all fields. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rhythm with occasional pauses and no evidence of murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. The abdomen is soft and nontender, without evidence of organomegaly or masses. The peripheral pulses are 2+ bilaterally in all extremities, and the neurologic exam is intact. An ECG is performed, which reveals a ventricular rate of 55 beats/min; PR interval, 146 ms; QRS duration, 122 ms; QT/QTc interval, 424/405 ms; P axis, 60°; R axis, 38°; and T axis, 29°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

A 48-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of several relatively minor skin problems. One of them is a taglike lesion on the skin of her low back. Present for years, it has begun to bother her a bit; it rubs against her clothes and is occasionally traumatized enough to bleed. The patient isn’t worried about it but does want it removed. Her history is unremarkable, with no personal or family history of skin cancer. She is fair and tolerates the sun poorly, but for that reason she has limited her sun exposure throughout her life. The lesion is a 5 x 6–mm taglike nodule located in the midline of her low back. At first glance, it appears to be traumatized. But on closer inspection, the distal half of the lesion is simply black, with indistinct margins. On palpation, the lesion is firmer than most tags but nontender. A few drops of lidocaine with epinephrine are injected into the base of the lesion, which is then saucerized. Minor bleeding is easily controlled by electrocautery, and the lesion is submitted to pathology. The resultant report shows a simple benign tag. No explanation for the darker portion of the lesion is given.

Erythematous Friable Papules on the Flank

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Pyogenic Granuloma With Satellite Papules

Pyogenic granulomas, also known as lobular capillary hemangiomas, are common benign, friable, rapidly growing, erythematous and exophytic papules with a surrounding collarette of scale. Due to the friable nature of these lesions, they are often hemorrhagic and ulcerative on presentation; however, disseminated pyogenic granulomas frequently are more sessile in appearance with a smooth surface. The pathogenesis of these lesions is largely unknown, but they exhibit a number of clinical features suggestive of reactive neovascularization.1

Primary pyogenic granulomas occur most often on sites with high vascularity (eg, gingiva, lips, fingers, face, tongue), but no site on the skin is exempt.2,3 They are found most commonly in children and young adults after minor trauma and also are associated with pregnancy with a higher frequency of occurrence on the gingiva in that particular setting.2

The differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma includes warts or inflamed intradermal nevi as well as bacillary angiomatosis and Kaposi sarcoma in an immunosuppressed patient. Most importantly, pyogenic granulomas can be confused with amelanotic melanoma; therefore, biopsy to rule out this condition is mandatory. On histopathology, pyogenic granuloma is characterized by a proliferation of capillaries arranged in a lobular pattern separated by a pale stroma (Figure).

Pyogenic granulomas usually are solitary lesions; however, recurrence after treatment is common. These benign growths have been reported to arise from certain systemic agents including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and indinavir.1 Disseminated pyogenic granulomas are rare, but cases in children and adults have been reported, many associated with prior trauma. In addition, congenital disseminated pyogenic granulomas have been described, which could be easily confused with infantile hemangiomatosis; however, the former are GLUT-1 (glucose transporter type 1) negative.4

Although recurrence of pyogenic granulomas is common, recurrence with satellite lesions is relatively rare. In documented cases, such as the Blickenstaff et al2 report, recurrences occurred most commonly on the trunk, especially in the scapular area in adolescents and young adults. They often occur after prior irritation or treatment of the primary lesion but also may spontaneously develop. After initial therapy, satellites may arise either with or without recurrence of the primary lesion. These satellite lesions usually are smaller than the original lesion, smooth, bright red, are not as friable, and lack a collarette.2,3

Recurrence of pyogenic granulomas with satellite lesions has been reported to occur in association with almost all forms of treatment, including excision with cautery and CO2 laser. These recurrences have been successfully treated with simple excision, cryotherapy, diathermy, and curettage; however, some physicians recommend a conservative approach to therapy, as a majority of these lesions tend to spontaneously resolve after 6 to 12 months.2,3,5

Ezzell et al6 and others have reported successful treatment of pyogenic granulomas with imiquimod cream 5%. Imiquimod is thought to trigger resolution of pyogenic granulomas due to its antitumor and immunoregulatory effects. As a topical agent, imiquimod would offer patients a safe and noninvasive therapy that would be especially beneficial for larger lesions with satellites, similar to the papules described in our patient.6,7

After a repeat biopsy in our patient confirmed pyogenic granuloma, she was started on imiquimod cream 5% applied nightly, which continued for 6 weeks. Follow-up after 6 weeks revealed no change in lesion size and the family opted to discontinue treatment at that time because of a lack of response. Although a continued conservative approach was recommended by our facility, the patient and guardians opted for surgical excision and were referred to a local pediatric surgeon for excision under general anesthesia.

1. North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Elsevier; 2008:1771-1794.

2. Blickenstaff RD, Roenigk RK, Peters MS, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1241-1244.

3. Allen R, Rodman O. Pyogenic granuloma recurrent with satellite lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:490-492.

4. Browning JC, Eldin KW, Kozakewich HP, et al. Congenital disseminated pyogenic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:323-327.

5. Fisher I. Recurrent multiple pyogenic granuloma with multiple satellites. features of Masson’s hemangioma. Cutis. 1977;20:201-205.

6. Ezzell TI, Fromowitz JS, Ramos-Caro FA. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma treated with topical imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S244-S245.

7. Tritton SM, Smith S, Wong LC, et al. Pyogenic granuloma in ten children treated with topical imiquimod. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:269-272.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Pyogenic Granuloma With Satellite Papules

Pyogenic granulomas, also known as lobular capillary hemangiomas, are common benign, friable, rapidly growing, erythematous and exophytic papules with a surrounding collarette of scale. Due to the friable nature of these lesions, they are often hemorrhagic and ulcerative on presentation; however, disseminated pyogenic granulomas frequently are more sessile in appearance with a smooth surface. The pathogenesis of these lesions is largely unknown, but they exhibit a number of clinical features suggestive of reactive neovascularization.1

Primary pyogenic granulomas occur most often on sites with high vascularity (eg, gingiva, lips, fingers, face, tongue), but no site on the skin is exempt.2,3 They are found most commonly in children and young adults after minor trauma and also are associated with pregnancy with a higher frequency of occurrence on the gingiva in that particular setting.2

The differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma includes warts or inflamed intradermal nevi as well as bacillary angiomatosis and Kaposi sarcoma in an immunosuppressed patient. Most importantly, pyogenic granulomas can be confused with amelanotic melanoma; therefore, biopsy to rule out this condition is mandatory. On histopathology, pyogenic granuloma is characterized by a proliferation of capillaries arranged in a lobular pattern separated by a pale stroma (Figure).

Pyogenic granulomas usually are solitary lesions; however, recurrence after treatment is common. These benign growths have been reported to arise from certain systemic agents including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and indinavir.1 Disseminated pyogenic granulomas are rare, but cases in children and adults have been reported, many associated with prior trauma. In addition, congenital disseminated pyogenic granulomas have been described, which could be easily confused with infantile hemangiomatosis; however, the former are GLUT-1 (glucose transporter type 1) negative.4

Although recurrence of pyogenic granulomas is common, recurrence with satellite lesions is relatively rare. In documented cases, such as the Blickenstaff et al2 report, recurrences occurred most commonly on the trunk, especially in the scapular area in adolescents and young adults. They often occur after prior irritation or treatment of the primary lesion but also may spontaneously develop. After initial therapy, satellites may arise either with or without recurrence of the primary lesion. These satellite lesions usually are smaller than the original lesion, smooth, bright red, are not as friable, and lack a collarette.2,3

Recurrence of pyogenic granulomas with satellite lesions has been reported to occur in association with almost all forms of treatment, including excision with cautery and CO2 laser. These recurrences have been successfully treated with simple excision, cryotherapy, diathermy, and curettage; however, some physicians recommend a conservative approach to therapy, as a majority of these lesions tend to spontaneously resolve after 6 to 12 months.2,3,5

Ezzell et al6 and others have reported successful treatment of pyogenic granulomas with imiquimod cream 5%. Imiquimod is thought to trigger resolution of pyogenic granulomas due to its antitumor and immunoregulatory effects. As a topical agent, imiquimod would offer patients a safe and noninvasive therapy that would be especially beneficial for larger lesions with satellites, similar to the papules described in our patient.6,7

After a repeat biopsy in our patient confirmed pyogenic granuloma, she was started on imiquimod cream 5% applied nightly, which continued for 6 weeks. Follow-up after 6 weeks revealed no change in lesion size and the family opted to discontinue treatment at that time because of a lack of response. Although a continued conservative approach was recommended by our facility, the patient and guardians opted for surgical excision and were referred to a local pediatric surgeon for excision under general anesthesia.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Pyogenic Granuloma With Satellite Papules

Pyogenic granulomas, also known as lobular capillary hemangiomas, are common benign, friable, rapidly growing, erythematous and exophytic papules with a surrounding collarette of scale. Due to the friable nature of these lesions, they are often hemorrhagic and ulcerative on presentation; however, disseminated pyogenic granulomas frequently are more sessile in appearance with a smooth surface. The pathogenesis of these lesions is largely unknown, but they exhibit a number of clinical features suggestive of reactive neovascularization.1

Primary pyogenic granulomas occur most often on sites with high vascularity (eg, gingiva, lips, fingers, face, tongue), but no site on the skin is exempt.2,3 They are found most commonly in children and young adults after minor trauma and also are associated with pregnancy with a higher frequency of occurrence on the gingiva in that particular setting.2

The differential diagnosis of pyogenic granuloma includes warts or inflamed intradermal nevi as well as bacillary angiomatosis and Kaposi sarcoma in an immunosuppressed patient. Most importantly, pyogenic granulomas can be confused with amelanotic melanoma; therefore, biopsy to rule out this condition is mandatory. On histopathology, pyogenic granuloma is characterized by a proliferation of capillaries arranged in a lobular pattern separated by a pale stroma (Figure).

Pyogenic granulomas usually are solitary lesions; however, recurrence after treatment is common. These benign growths have been reported to arise from certain systemic agents including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, systemic retinoids, and indinavir.1 Disseminated pyogenic granulomas are rare, but cases in children and adults have been reported, many associated with prior trauma. In addition, congenital disseminated pyogenic granulomas have been described, which could be easily confused with infantile hemangiomatosis; however, the former are GLUT-1 (glucose transporter type 1) negative.4

Although recurrence of pyogenic granulomas is common, recurrence with satellite lesions is relatively rare. In documented cases, such as the Blickenstaff et al2 report, recurrences occurred most commonly on the trunk, especially in the scapular area in adolescents and young adults. They often occur after prior irritation or treatment of the primary lesion but also may spontaneously develop. After initial therapy, satellites may arise either with or without recurrence of the primary lesion. These satellite lesions usually are smaller than the original lesion, smooth, bright red, are not as friable, and lack a collarette.2,3

Recurrence of pyogenic granulomas with satellite lesions has been reported to occur in association with almost all forms of treatment, including excision with cautery and CO2 laser. These recurrences have been successfully treated with simple excision, cryotherapy, diathermy, and curettage; however, some physicians recommend a conservative approach to therapy, as a majority of these lesions tend to spontaneously resolve after 6 to 12 months.2,3,5

Ezzell et al6 and others have reported successful treatment of pyogenic granulomas with imiquimod cream 5%. Imiquimod is thought to trigger resolution of pyogenic granulomas due to its antitumor and immunoregulatory effects. As a topical agent, imiquimod would offer patients a safe and noninvasive therapy that would be especially beneficial for larger lesions with satellites, similar to the papules described in our patient.6,7

After a repeat biopsy in our patient confirmed pyogenic granuloma, she was started on imiquimod cream 5% applied nightly, which continued for 6 weeks. Follow-up after 6 weeks revealed no change in lesion size and the family opted to discontinue treatment at that time because of a lack of response. Although a continued conservative approach was recommended by our facility, the patient and guardians opted for surgical excision and were referred to a local pediatric surgeon for excision under general anesthesia.

1. North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Elsevier; 2008:1771-1794.

2. Blickenstaff RD, Roenigk RK, Peters MS, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1241-1244.

3. Allen R, Rodman O. Pyogenic granuloma recurrent with satellite lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:490-492.

4. Browning JC, Eldin KW, Kozakewich HP, et al. Congenital disseminated pyogenic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:323-327.

5. Fisher I. Recurrent multiple pyogenic granuloma with multiple satellites. features of Masson’s hemangioma. Cutis. 1977;20:201-205.

6. Ezzell TI, Fromowitz JS, Ramos-Caro FA. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma treated with topical imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S244-S245.

7. Tritton SM, Smith S, Wong LC, et al. Pyogenic granuloma in ten children treated with topical imiquimod. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:269-272.

1. North PE, Kincannon J. Vascular neoplasms and neoplastic-like proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Elsevier; 2008:1771-1794.

2. Blickenstaff RD, Roenigk RK, Peters MS, et al. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma with satellitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1241-1244.

3. Allen R, Rodman O. Pyogenic granuloma recurrent with satellite lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:490-492.

4. Browning JC, Eldin KW, Kozakewich HP, et al. Congenital disseminated pyogenic granuloma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:323-327.

5. Fisher I. Recurrent multiple pyogenic granuloma with multiple satellites. features of Masson’s hemangioma. Cutis. 1977;20:201-205.

6. Ezzell TI, Fromowitz JS, Ramos-Caro FA. Recurrent pyogenic granuloma treated with topical imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S244-S245.

7. Tritton SM, Smith S, Wong LC, et al. Pyogenic granuloma in ten children treated with topical imiquimod. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:269-272.

An 11-year-old girl presented to our clinic with a small erythematous friable papule on the right side of the flank. She reported that the papule bled easily and was mildly tender to palpation. A shave biopsy with electrocautery to the base of the lesion was performed. The patient returned 1 month later with recurrence of the papule and was treated with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser during her clinic visit. She returned 3 weeks later with persistence of the same papule and also with several new smaller but similar-appearing papules.

Indurated Thigh Plaque With Associated Lymphadenopathy

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

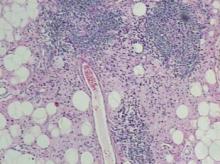

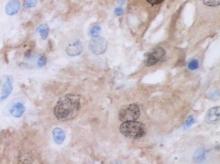

Punch biopsies of the mass from the right thigh were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a reactive fibroinflammatory process of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with fibrosis and prominent lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic infiltrate with emperipolesis (Figure 1). The histiocytes stained positive for S-100 (Figure 2) and CD68. Markers for CD34, smooth muscle actin, and keratin were negative, as were acid-fast bacteria (Ziehl-Neelsen) and fungal (Gomori methenamine-silver) stains. The morphologic and immunohistochemical features of the biopsy specimens were consistent with Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a benign histiocytic proliferative disorder that usually involves the lymph nodes but may involve any organ system including the skin and soft tissue.1,2 Systemic RDD usually presents in children or young adults as massive cervical lymphadenopathy, often with fever, polyclonal hyperglobulinemia, mild anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and occasionally neutropenia.2 Rosai-Dorfman disease was first described as a distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1969.3

Extranodal involvement occurs in approximately 40% of patients, with cutaneous disease in approximately 10% of cases. Other sites that may be affected include the eyelid and orbit, salivary glands, lungs, central nervous system, and bone.2 Purely cutaneous RDD is rare and has a variable skin distribution. Compared to systemic RDD, cutaneous disease affects older patients with a predilection for females and white individuals.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous RDD reveals a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes with scattered lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.2 Emperipolesis, consisting of intact lymphocytes and less commonly plasma cells in the cytoplasm of the histiocytes, is a characteristic feature of cutaneous RDD. Occasional findings include fibrosis, lymphoid aggregates, foamy histiocytes inside of dilated lymphatics, thick-walled venules with surrounding plasma cells, and multinucleate histiocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry is helpful in diagnosing RDD, as the histiocytes stain strongly positive for S-100, occasionally positive for CD68, and negative for CD1a.5

The pathogenesis of RDD remains unknown. Some cases of RDD have had positive serologies for human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Barr virus, though an infectious origin has not been proven.5 Clonality studies have shown the cellular infiltrate to be polyclonal, supporting a reactive rather than neoplastic process.6 The disease course of RDD varies from self-limited to protracted with remissions and exacerbations. Many cutaneous RDD lesions spontaneously heal and only require treatment when disseminated, destructive, or causing physical compromise.2 Treatment modalities for cutaneous RDD have exhibited varying degrees of success and include surgical excision; thalidomide; isotretinoin; radiotherapy; alkylating agents; and oral, topical, and intralesional steroids.2

The mass in our patient was surgically excised, though surgical margins remained positive. He was followed by the hematology-oncology service and later reported the development of 2 additional masses in the right leg with intermittent tenderness. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head was negative for intracranial abnormalities, though it did demonstrate prominent nasopharyngeal soft tissue and sinus disease. A complete skeletal radiograph survey and whole-body technetium bone scan did not show evidence of bone involvement. Chest computed tomography was negative for mass lesions. The patient deferred a bone marrow biopsy and was reportedly doing well at follow-up without further treatment.

1. Rubenstein MA, Farnsworth NN, Pielop JA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:8.

2. Goodman WT, Barrett TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1395-1410.

3. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

4. Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

5. Wartman DG, Perry A, Werchniak AE. Multiple nodules and plaques on the face and trunk. cutaneous Rosai Dorfman disease (RDD). Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1501-1506.

6. Paulli M, Bergamaschi G, Tonon L. Evidence for a polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate in sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease). Br J Haematol. 1995;91:415-418.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Punch biopsies of the mass from the right thigh were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a reactive fibroinflammatory process of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with fibrosis and prominent lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic infiltrate with emperipolesis (Figure 1). The histiocytes stained positive for S-100 (Figure 2) and CD68. Markers for CD34, smooth muscle actin, and keratin were negative, as were acid-fast bacteria (Ziehl-Neelsen) and fungal (Gomori methenamine-silver) stains. The morphologic and immunohistochemical features of the biopsy specimens were consistent with Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a benign histiocytic proliferative disorder that usually involves the lymph nodes but may involve any organ system including the skin and soft tissue.1,2 Systemic RDD usually presents in children or young adults as massive cervical lymphadenopathy, often with fever, polyclonal hyperglobulinemia, mild anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and occasionally neutropenia.2 Rosai-Dorfman disease was first described as a distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1969.3

Extranodal involvement occurs in approximately 40% of patients, with cutaneous disease in approximately 10% of cases. Other sites that may be affected include the eyelid and orbit, salivary glands, lungs, central nervous system, and bone.2 Purely cutaneous RDD is rare and has a variable skin distribution. Compared to systemic RDD, cutaneous disease affects older patients with a predilection for females and white individuals.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous RDD reveals a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes with scattered lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.2 Emperipolesis, consisting of intact lymphocytes and less commonly plasma cells in the cytoplasm of the histiocytes, is a characteristic feature of cutaneous RDD. Occasional findings include fibrosis, lymphoid aggregates, foamy histiocytes inside of dilated lymphatics, thick-walled venules with surrounding plasma cells, and multinucleate histiocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry is helpful in diagnosing RDD, as the histiocytes stain strongly positive for S-100, occasionally positive for CD68, and negative for CD1a.5

The pathogenesis of RDD remains unknown. Some cases of RDD have had positive serologies for human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Barr virus, though an infectious origin has not been proven.5 Clonality studies have shown the cellular infiltrate to be polyclonal, supporting a reactive rather than neoplastic process.6 The disease course of RDD varies from self-limited to protracted with remissions and exacerbations. Many cutaneous RDD lesions spontaneously heal and only require treatment when disseminated, destructive, or causing physical compromise.2 Treatment modalities for cutaneous RDD have exhibited varying degrees of success and include surgical excision; thalidomide; isotretinoin; radiotherapy; alkylating agents; and oral, topical, and intralesional steroids.2

The mass in our patient was surgically excised, though surgical margins remained positive. He was followed by the hematology-oncology service and later reported the development of 2 additional masses in the right leg with intermittent tenderness. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head was negative for intracranial abnormalities, though it did demonstrate prominent nasopharyngeal soft tissue and sinus disease. A complete skeletal radiograph survey and whole-body technetium bone scan did not show evidence of bone involvement. Chest computed tomography was negative for mass lesions. The patient deferred a bone marrow biopsy and was reportedly doing well at follow-up without further treatment.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Punch biopsies of the mass from the right thigh were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a reactive fibroinflammatory process of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with fibrosis and prominent lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic infiltrate with emperipolesis (Figure 1). The histiocytes stained positive for S-100 (Figure 2) and CD68. Markers for CD34, smooth muscle actin, and keratin were negative, as were acid-fast bacteria (Ziehl-Neelsen) and fungal (Gomori methenamine-silver) stains. The morphologic and immunohistochemical features of the biopsy specimens were consistent with Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a benign histiocytic proliferative disorder that usually involves the lymph nodes but may involve any organ system including the skin and soft tissue.1,2 Systemic RDD usually presents in children or young adults as massive cervical lymphadenopathy, often with fever, polyclonal hyperglobulinemia, mild anemia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and occasionally neutropenia.2 Rosai-Dorfman disease was first described as a distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1969.3

Extranodal involvement occurs in approximately 40% of patients, with cutaneous disease in approximately 10% of cases. Other sites that may be affected include the eyelid and orbit, salivary glands, lungs, central nervous system, and bone.2 Purely cutaneous RDD is rare and has a variable skin distribution. Compared to systemic RDD, cutaneous disease affects older patients with a predilection for females and white individuals.4

Histologic examination of cutaneous RDD reveals a dense dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes with scattered lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.2 Emperipolesis, consisting of intact lymphocytes and less commonly plasma cells in the cytoplasm of the histiocytes, is a characteristic feature of cutaneous RDD. Occasional findings include fibrosis, lymphoid aggregates, foamy histiocytes inside of dilated lymphatics, thick-walled venules with surrounding plasma cells, and multinucleate histiocytes.2 Immunohistochemistry is helpful in diagnosing RDD, as the histiocytes stain strongly positive for S-100, occasionally positive for CD68, and negative for CD1a.5

The pathogenesis of RDD remains unknown. Some cases of RDD have had positive serologies for human herpesvirus 6 and Epstein-Barr virus, though an infectious origin has not been proven.5 Clonality studies have shown the cellular infiltrate to be polyclonal, supporting a reactive rather than neoplastic process.6 The disease course of RDD varies from self-limited to protracted with remissions and exacerbations. Many cutaneous RDD lesions spontaneously heal and only require treatment when disseminated, destructive, or causing physical compromise.2 Treatment modalities for cutaneous RDD have exhibited varying degrees of success and include surgical excision; thalidomide; isotretinoin; radiotherapy; alkylating agents; and oral, topical, and intralesional steroids.2

The mass in our patient was surgically excised, though surgical margins remained positive. He was followed by the hematology-oncology service and later reported the development of 2 additional masses in the right leg with intermittent tenderness. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head was negative for intracranial abnormalities, though it did demonstrate prominent nasopharyngeal soft tissue and sinus disease. A complete skeletal radiograph survey and whole-body technetium bone scan did not show evidence of bone involvement. Chest computed tomography was negative for mass lesions. The patient deferred a bone marrow biopsy and was reportedly doing well at follow-up without further treatment.

1. Rubenstein MA, Farnsworth NN, Pielop JA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:8.

2. Goodman WT, Barrett TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1395-1410.

3. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

4. Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

5. Wartman DG, Perry A, Werchniak AE. Multiple nodules and plaques on the face and trunk. cutaneous Rosai Dorfman disease (RDD). Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1501-1506.

6. Paulli M, Bergamaschi G, Tonon L. Evidence for a polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate in sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease). Br J Haematol. 1995;91:415-418.

1. Rubenstein MA, Farnsworth NN, Pielop JA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:8.

2. Goodman WT, Barrett TL. Histiocytoses. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:1395-1410.

3. Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

4. Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

5. Wartman DG, Perry A, Werchniak AE. Multiple nodules and plaques on the face and trunk. cutaneous Rosai Dorfman disease (RDD). Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1501-1506.

6. Paulli M, Bergamaschi G, Tonon L. Evidence for a polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate in sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease). Br J Haematol. 1995;91:415-418.

A 38-year-old white man with a history of lower extremity varicose veins was referred for evaluation of a plaque on the medial aspect of the right thigh and right inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient reported having the lesion for approximately 1 year; over time it had become progressively more indurated. He denied pain, discomfort, and pruritus at the site, as well as any systemic symptoms. The patient had no known allergies, was not taking any medications, smoked 1 pack of tobacco daily for 20 years, drank alcohol socially, and was not sexually active. His family history was noncontributory. Prior to the dermatology consultation, a computed tomography scan of the right leg, abdomen, and pelvis was obtained and demonstrated a subcutaneous mass in the distal third of the medial aspect of the right thigh as well as pericaval and right inguinal lymphadenopathy. Physical examination revealed a violaceous, indurated, nodular plaque on the medial aspect of the right thigh measuring approximately 10×5 cm. Multiple small, nontender, mobile lymph nodes were palpated on the right side of the inguinal region. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Elderly Woman Takes a Fall