User login

A Purplish Rash on the Instep

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen planus (choice “d”), an inflammatory condition marked by pathognomic histologic changes such as those described. Hardly on the tip of most primary care providers’ tongues, lichen planus is nonetheless quite commonly occuring.

Tinea pedis (choice “a”) certainly belongs in the differential, but it would be unusual in a woman of this age. The biopsy effectively ruled it out, as it did psoriasis (choice “b”) and contact dermatitis (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus (LP) is the prototypical lichenoid interface dermatitis; an inflammatory infiltrate erases the normally well-defined dermoepidermal junction, replacing it with a jagged “sawtooth” band of lymphocytes. In the process, the cells it kills off (keratinocytes) collect at this interface and are incorporated as necrotic keratinocytes into the papillary dermis.

Classically, the recognition of LP is taught with “The Ps.” LP is said to be:

• Papular

• Planar

• Purple

• Polygonal

• Pruritic

• Plaquish

• Penile

• Puzzling

The word “puzzling” may sound nebulous, but it is actually quite useful for dermatology providers. It comes into play whenever a condition stumps us—as in, “What in the world is this?” This puzzlement causes us to at least consider LP.

LP is often papular, and these papules often have flat (planar) tops. The purple color is more striking in lighter-skinned patients. (Almost all inflammatory conditions are more difficult to diagnose in those with darker skin.) More typically, LP lesions are multi-angular or polygonal, often plaquish, and almost invariably pruritic.

LP is common on the legs and/or trunk, favoring the sacral area. It can affect the scalp (being in the differential for hair loss), can cause nail dystrophy, and is relatively common in the mouth, where it presents as a lacy, reticular, slightly erosive process, usually affecting the buccal mucosae. It may be found on the penis, where it is usually confined to the distal shaft and proximal coronal areas.

Like many otherwise benign conditions, LP can present with bullae. In anterior tibial areas, especially on darker-skinned persons, it can be remarkably hypertrophic.

The cause is usually unknown, although certain drugs—especially the antimalarials, gold salts, and penicillamine—have been known to cause LP-like eruptions. It’s been my observation that flares of LP are prompted by stress (certainly present in this patient’s case). LP may have a connection to hepatitis, although no convincing connection has been established.

TREATMENT

This patient’s condition was treated with topical class I corticosteroid ointment (halobetasol). For her, having a certain diagnosis was almost as important as successful treatment.

Several months ago, an itchy rash appeared on the foot of this 61-year-old African-American woman. She tried using a variety of OTC and prescription products, including tolnaftate cream, hydrocortisone 1% cream, and triamcinolone cream, but the rash persisted. She reports that the triamcinolone cream did relieve the itching for a few minutes after application, but the symptoms always returned. The rash has gradually grown. The patient, a retired schoolteacher, denies any other skin problems. She does have several relatively minor health problems, including hypertension (well controlled with metoprolol) and mild reactive airway disease (related to a 20-year history of smoking). The rash manifested around the time she was forced to retire in an unforeseen downsizing effort by her school district. As a result, she lost her health care coverage and could not afford private insurance for herself and her husband (neither of whom are old enough to qualify for Medicare). The rash, which covers a roughly 12 × 8–cm area, begins on her left instep and spills onto the lower ankle. It is quite dark, as would be expected in a person with type V skin, but there is a slightly purplish tinge to it. The surface of the affected area is a bit shiny and atrophic, and the margins are well defined and annular. There is almost no scaling, and the rest of the skin on her feet and legs is well within normal limits. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed on the lesion. The pathology report shows obliteration of the dermoepidermal junction by a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis, associated with vacuolar changes and the accumulation of necrotic keratinocytes in the basal layer.

Man Has “a Couple of Blocks Somewhere”

ANSWER

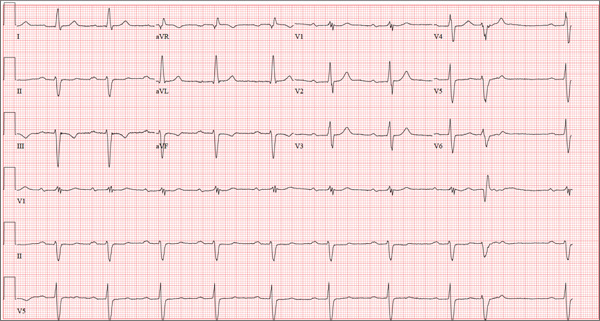

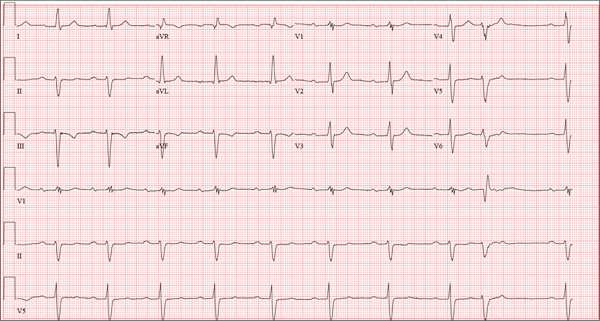

The correct interpretation includes sinus bradycardia with first-degree block, a single premature atrial beat with aberrancy, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block), left ventricular hypertrophy, and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads.

In sinus bradycardia, there is a P wave for every QRS complex with a rate less than 60 beats/min. First-degree block is evidenced by a PR interval ≥ 200 ms.

A single premature atrial contraction is seen as the ninth beat on the ECG. Aberrancy refers to the appearance of the QRS complex; the impulse arises above the AV node but propagates down the AV node and His-Purkinje system to the ventricles before the conduction system is fully repolarized. This results in a QRS complex with intrinsic conduction similar to a normally conducted beat, which then becomes wide and uncharacteristic. Additionally, it resets the sinus node, resulting in a pause before the next normally conducted P wave.

A right bundle branch block is evidenced by the presence of normal conduction with a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal R wave in lead V1 (R, rR’, rsR’, or qR), and slurred S waves in leads I and V6.

The presence of left anterior fascicular block is confirmed by the left-axis deviation (–59° in this ECG), a qR complex in leads I and aVL, and an rS pattern in leads II, III, and aVF. The presence of both a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitutes bifascicular block. (This is a conduction problem and does not refer to blockage in the arteries, as the patient believed!)

Criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy are met when the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm and the R wave in aVL is ≥ 11 mm.

Two other things to note in this ECG are the presence of T-wave inversions in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) which are of unclear reason; and the presence of biphasic P waves that do not meet criteria for either right or left atrial hypertrophy.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus bradycardia with first-degree block, a single premature atrial beat with aberrancy, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block), left ventricular hypertrophy, and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads.

In sinus bradycardia, there is a P wave for every QRS complex with a rate less than 60 beats/min. First-degree block is evidenced by a PR interval ≥ 200 ms.

A single premature atrial contraction is seen as the ninth beat on the ECG. Aberrancy refers to the appearance of the QRS complex; the impulse arises above the AV node but propagates down the AV node and His-Purkinje system to the ventricles before the conduction system is fully repolarized. This results in a QRS complex with intrinsic conduction similar to a normally conducted beat, which then becomes wide and uncharacteristic. Additionally, it resets the sinus node, resulting in a pause before the next normally conducted P wave.

A right bundle branch block is evidenced by the presence of normal conduction with a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal R wave in lead V1 (R, rR’, rsR’, or qR), and slurred S waves in leads I and V6.

The presence of left anterior fascicular block is confirmed by the left-axis deviation (–59° in this ECG), a qR complex in leads I and aVL, and an rS pattern in leads II, III, and aVF. The presence of both a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitutes bifascicular block. (This is a conduction problem and does not refer to blockage in the arteries, as the patient believed!)

Criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy are met when the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm and the R wave in aVL is ≥ 11 mm.

Two other things to note in this ECG are the presence of T-wave inversions in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) which are of unclear reason; and the presence of biphasic P waves that do not meet criteria for either right or left atrial hypertrophy.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus bradycardia with first-degree block, a single premature atrial beat with aberrancy, right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block), left ventricular hypertrophy, and T-wave inversions in the inferior leads.

In sinus bradycardia, there is a P wave for every QRS complex with a rate less than 60 beats/min. First-degree block is evidenced by a PR interval ≥ 200 ms.

A single premature atrial contraction is seen as the ninth beat on the ECG. Aberrancy refers to the appearance of the QRS complex; the impulse arises above the AV node but propagates down the AV node and His-Purkinje system to the ventricles before the conduction system is fully repolarized. This results in a QRS complex with intrinsic conduction similar to a normally conducted beat, which then becomes wide and uncharacteristic. Additionally, it resets the sinus node, resulting in a pause before the next normally conducted P wave.

A right bundle branch block is evidenced by the presence of normal conduction with a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal R wave in lead V1 (R, rR’, rsR’, or qR), and slurred S waves in leads I and V6.

The presence of left anterior fascicular block is confirmed by the left-axis deviation (–59° in this ECG), a qR complex in leads I and aVL, and an rS pattern in leads II, III, and aVF. The presence of both a right bundle and left anterior fascicular block constitutes bifascicular block. (This is a conduction problem and does not refer to blockage in the arteries, as the patient believed!)

Criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy are met when the sum of the S wave in V1 and the R wave in either V5 or V6 is ≥ 35 mm and the R wave in aVL is ≥ 11 mm.

Two other things to note in this ECG are the presence of T-wave inversions in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) which are of unclear reason; and the presence of biphasic P waves that do not meet criteria for either right or left atrial hypertrophy.

A 69-year-old man presents for a routine appointment. His cardiac history is remarkable for systemic hypertension, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, and dyspnea on exertion. He says a previous provider told him his ECG had “a couple of blocks,” which he believes are “somewhere in the arteries.” He regularly feels lightheaded if he rises from a lying or sitting position too quickly, but he has never lost consciousness. He denies any history of chest pain or symptoms suggestive of angina. Reviewing his prior cardiac workup, you find an echocardiogram that shows moderate left ventricular enlargement with a left ventricular ejection fraction estimated at 35% to 40%; a severely enlarged left atrium; and mild thickening of the mitral leaflets as well as mild mitral regurgitation. A report from an old ECG (conducted at an outside institution) reveals sinus bradycardia, bifascicular block, and left ventricular hypertrophy. Cardiac catheterization performed two years ago showed diffuse disease with no lesions > 30%. Pulmonary function testing showed mild airflow obstruction, no restrictive component, and mildly decreased diffusing capacity. Medical history is positive for two benign colonic polyps that were removed during his last colonoscopy and a remote history of malaria while traveling in Africa 10 years ago. He also has a history of depression, which has been well controlled by medication. His list of medications includes carvedilol, fluoxetine, melatonin, and lisinopril. He is allergic to atenolol and metoprolol. His family history is remarkable for type 1 diabetes (mother). He is a retired baggage handler for a major airline at a nearby international airport. Since high school, he has smoked between one-half and one pack of cigarettes per day. He typically consumes a 12-pack of beer on the weekends. The review of systems is remarkable for corrective lenses, occasional headaches, and dyspnea. The patient denies any other symptoms. Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 138/80 mm Hg; pulse, 64 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and O2 saturation, 97%. His height is 188 cm; weight, 107 kg; and BMI, 30. The lungs are clear to auscultation and percussion. The cardiac exam reveals no jugular venous distention, a normal rate and rhythm with occasional skipped beats, and a soft, grade II/VI blowing systolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border. The point of maximum impulse is palpable in the left anterior axillary line. The abdomen is soft and nontender, with no organomegaly. The genitourinary exam is normal. Peripheral pulses are 2+ bilaterally in both upper and lower extremities. There is no peripheral edema, and the neurologic exam is grossly intact. The patient is sent for a chest x-ray and an ECG. The latter reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 59 beats/min; PR interval, 284 ms; QRS duration, 130 ms; QT/QTc interval, 472/467 ms; P axis, 70°; R axis, –59°; and T axis, –29°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

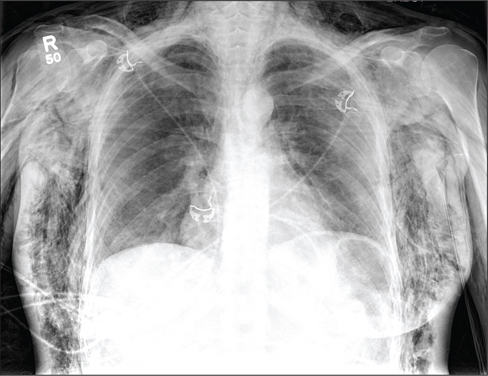

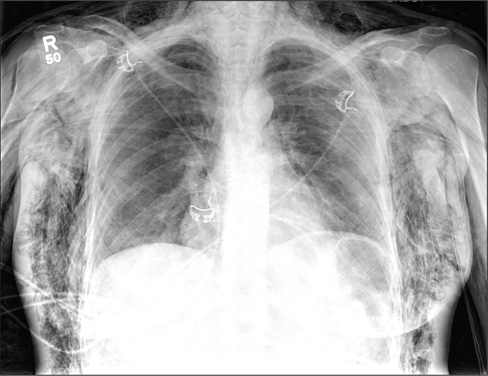

Woman Assaulted on Street

The chest radiograph demonstrates a massive amount of soft tissue and subcutaneous emphysema extending from the neck down through the chest and into the lower chest/upper abdomen. In addition, there are several fractured posterior ribs bilaterally. No large pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is noted.

Because of the extent and mechanism of injury, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis had already been ordered. Arrangements were also made for the patient to be admitted to the ICU for closer observation.

The chest radiograph demonstrates a massive amount of soft tissue and subcutaneous emphysema extending from the neck down through the chest and into the lower chest/upper abdomen. In addition, there are several fractured posterior ribs bilaterally. No large pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is noted.

Because of the extent and mechanism of injury, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis had already been ordered. Arrangements were also made for the patient to be admitted to the ICU for closer observation.

The chest radiograph demonstrates a massive amount of soft tissue and subcutaneous emphysema extending from the neck down through the chest and into the lower chest/upper abdomen. In addition, there are several fractured posterior ribs bilaterally. No large pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum is noted.

Because of the extent and mechanism of injury, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis had already been ordered. Arrangements were also made for the patient to be admitted to the ICU for closer observation.

A 40-year-old woman is brought in by EMS for evaluation of injuries secondary to being assaulted. She was out walking late last night when she was approached by two men who pushed her to the ground and began punching and kicking her repeatedly on her face, chest, and back. She is primarily complaining of chest wall and back pain. Her medical history is significant for hypertension, diet-controlled diabetes, and “some sort of heart problem” for which she takes medication. Surgical history is significant for hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and appendectomy. She smokes more than a pack of cigarettes per day and consumes at least a six-pack of beer daily. Initial exam shows an anxious female who appears somewhat uncomfortable but is in no obvious distress. Her vital signs are as follows: blood pressure, 130/88 mm Hg; pulse, 120 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air. Physical exam reveals extensive facial/periorbital swelling, as well as swelling in the neck. Some splinting is noted. There is extensive crepitus noted within the soft tissue of the face, neck, and chest wall. Also, there is moderate tenderness bilaterally over the ribs. Chest radiograph is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

Competitive Swimmer With Hip Pain

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

A 17-year-old girl presents for evaluation of severe pain in her left hip. She is a competitive swimmer; earlier in the day, she was at practice doing dry land (out of the water) activities/exercises. Having completed a series of stretches and warm-up exercises, she and her teammates proceeded to do sprints. During one of these sprints, she immediately felt a “pop” in her left hip followed by severe, debilitating pain in that hip and thigh. Medical history is otherwise unremarkable. Physical exam reveals that it is extremely painful for the patient to bear weight on the affected leg. There is moderate-to-severe tenderness over the lateral hip. Some swelling is noted; no bruising is present. Distal pulses are good, and motor and sensation are intact. Radiograph of the pelvis is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

Obese, Short of Breath, and Rationing Meds

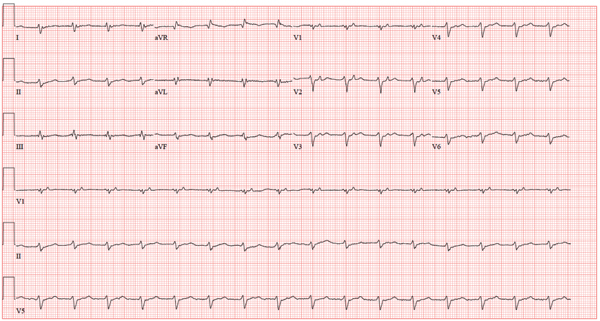

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

A 64-year-old man who is morbidly obese is admitted to the medical service with a two-week history of increasing shortness of breath, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He states that he has depleted his finances for the month and has resorted to taking his medications every other day in order to make them last until next payday. He denies chest pain but notes that he has had a lot of “heaviness” in his anterior chest for the past week and now has a persistent, nonproductive cough. His medical history is remarkable for a cardiomyopathy due to alcohol abuse, frequent pneumonias, and renal insufficiency. He has a history of sleep apnea and uses continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night in order to sleep. The patient is divorced, unemployed, lives alone in a subsidized apartment, and collects disability. Prior to filing for disability, he worked as a longshoreman. He is a former smoker who quit two years ago after several pulmonary infections. He attributes quitting smoking to his current weight problem. He states he has been an alcoholic for many years, and at one point consumed one bottle of whiskey per day along with one or two six-packs of beer. He has been to two alcohol rehab programs in the past five years and says he recently started drinking again when he learned his disability checks were not going to be increased. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease (mother) and diabetes (father). His parents and both of his siblings are being treated for hypertension. He has no known drug allergies. Current medications include aspirin, extended-release metoprolol, hydralazine, isosorbide mononitrate, torsemide, docusate, and senna. The review of systems is remarkable for chronic low back pain, corrective lenses, and multiple small venous ulcers on both legs that he states will “just not go away.” The physical exam reveals a morbidly obese male in mild distress. His weight is 494 lb and his height, is 70 in. His blood pressure is 120/82 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; temperature, 96.8°F; and O2 saturation, 92% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distension to 12 cm, coarse rales in both lower lung fields, distant heart sounds without evidence of a murmur or rub, an obese abdomen without palpable organomegaly or ascites, and 3+ pitting edema in both lower extremities to the level of the knees. There are multiple old and new small, superficial venous ulcers on both lower legs. The skin is warm and pink; however, pulses are not palpable. Upon his admission, a cardiac catheterization is performed, which shows a right dominant system with angiographically normal coronary arteries, a left ventricular ejection fraction of 44%, and no evidence of valvular disease. Right heart pressures include a pulmonary artery pressure of 70/62 mm Hg with a mean of 51 mm Hg. The wedge pressure is 35 mm Hg, the transpulmonary gradient is 10, and the cardiac output is 12.5 L/min with a cardiac index of 4.4 L/min. These data are consistent with moderate-to-severe pulmonary hypertension with severely elevated left-sided filling pressures. A transthoracic echocardiogram is remarkable for elevated left ventricular end diastolic volumes with diffuse hypokinesis and an ejection fraction of 40%. The patient is also found to have a small pericardial effusion and bilateral pleural effusions. An ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 98 beats/min; PR interval, 360 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 24/314 ms; P axis, 54°; R axis, 192°; and T axis, 24°. As you review these measurements, you are skeptical of a PR interval of 360 ms and refer to the tracing. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and is the PR interval of 360 ms correct?

Is Man Balding “Just Like Dad”?

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

A 39-year-old man presents with a two-month history of focal hair loss that has not responded to treatment. His primary care provider prescribed first an antifungal topical cream (clotrimazole/betamethasone bid for two weeks), then an oral antibiotic (cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days). Neither helped. His scalp is asymptomatic in the affected area (as well as elsewhere), but the hair loss is extremely upsetting to the patient. He is convinced (and has been told by family members) that he is merely going bald “just like his father.” The onset of his hair loss was rather sudden. It began with increased hair found in his sink and shower, followed by comments from family and coworkers. One friend loaned the patient his minoxidil solution, but twice-daily application for a week failed to slow the rate of hair loss. In general, the patient’s health is excellent; he does not require any maintenance medications. Neither he nor any family members have had any serious illnesses (eg, thyroid disease, lupus, vitiligo) that he could recall. The patient’s hair loss, affecting an approximately 10 x 8–cm area, is confined to the right parietal scalp and has a sharply defined border and strikingly oval shape. The hair loss within this area is complete, with no epidermal disturbance of the involved scalp skin noted on inspection or palpation. No nodes are palpable in the surrounding head or neck. No other areas of hair loss can be seen in hair-bearing areas.

A Different Source of Elbow Pain

ANSWER

The radiograph shows no obvious fracture or dislocation. However, there are two small, radiopaque densities noted within the soft tissue. These are most likely consistent with broken glass pieces.

When the laceration was irrigated and the wound probed, the glass bits were found and removed prior to wound closure.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows no obvious fracture or dislocation. However, there are two small, radiopaque densities noted within the soft tissue. These are most likely consistent with broken glass pieces.

When the laceration was irrigated and the wound probed, the glass bits were found and removed prior to wound closure.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows no obvious fracture or dislocation. However, there are two small, radiopaque densities noted within the soft tissue. These are most likely consistent with broken glass pieces.

When the laceration was irrigated and the wound probed, the glass bits were found and removed prior to wound closure.

A 30-year-old man is brought to your facility after being in a motor vehicle collision. He was an unrestrained driver who lost control of his vehicle, went off the road, and hit a tree. Emergency personnel on the scene indicated there was moderate damage to his vehicle, including a broken windshield, and no air bag deployment. The patient is complaining of right shoulder, chest, hip, and left elbow pain. His medical history is unremarkable. His vital signs are normal. On physical examination, he has superficial lacerations on his forehead, face, and both forearms. Bleeding from all wounds is controlled. Palpation reveals some bruising of the right shoulder, chest, right hip, and left elbow; no obvious deformity or neurovascular compromise is noted. Multiple radiographs are ordered; the left elbow is shown. What is your impression?

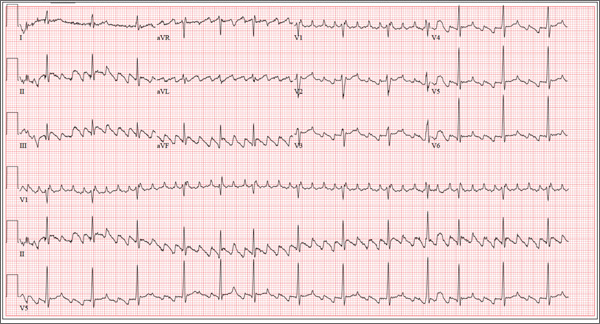

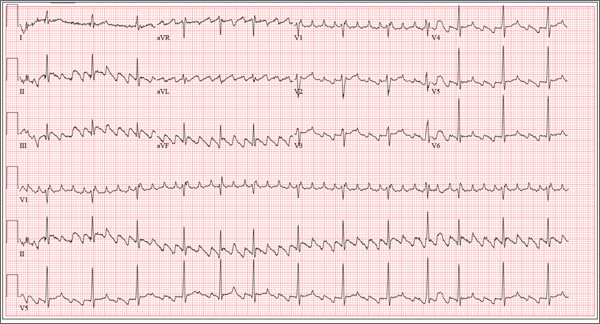

Young Man Thinks He is Having a Heart Attack

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

The 24-year-old male graduate student whom you saw one month ago for palpitations (see July 2013 ECG Challenge) returns without an appointment, stating that his heart is “flip-flopping” just as it has in the past. The problem started abruptly about 45 minutes ago, and he is afraid he might be having a heart attack. A quick check of his pulse reveals a rate of 80 beats/min. At his previous visit, an ECG showed sinus rhythm with sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC). A rhythm strip documented that his palpitations coincided with blocked PACs. You recall that he reported having two episodes of tachycardia in the past, while “pulling all-nighters” for finals as an undergraduate. Today, he denies shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, and symptoms of near-syncope or syncope, but says his heart is “flopping around” in his chest and he can feel his heart beat in his throat. He has no prior cardiac or pulmonary history and has not recently been ill. Medical history, medication list, allergies, family history, and review of systems are unchanged since his last visit: Medical history is remarkable only for fractures of the right ankle and the left clavicle. He takes no medications and has no drug allergies. Family history is significant for stroke (paternal grandfather), diabetes (maternal grandmother), and hypertension (father). The patient consumes alcohol socially, primarily on weekends, and does not binge drink. He smokes marijuana during snowboard season, but denies use at other times of the year. A 12-point review of systems is positive only for athlete’s foot and psoriasis on both upper extremities. The physical exam reveals an anxious but otherwise healthy, athletic-appearing male. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 140/88 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min-1; and O2 saturation, 99% on room air. His height is 70” and his weight, 161 lb. His lungs are clear, there is no jugular venous distention, and cardiac auscultation reveals no murmurs, gallops, or rubs. The abdominal exam is normal without organomegaly, and peripheral pulses are regular and strong bilaterally. His neurologic exam yields normal results. As you examine the ECG, you note the following: a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, unmeasurable; QRS duration, 92 ms; QT/QTc interval, 388/444 ms; P axis, 265°; R axis, 72°; and T axis, 66°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Not Just Another Groin Rash

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

A 60-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a somewhat itchy, unilateral groin rash. For several years, it has waxed and waned, never completely resolving. Recently, the rash has grown in size, and the itching has intensified, causing the patient to lose sleep. The patient has tried several OTC and prescription topical medications for this problem: creams containing clotrimazole, tolnaftate, 1% hydrocortisone, and betamethasone/clotrimazole, as well as triple-antibiotic ointment and several different moisturizing creams and lotions. He also tried a two-week course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). Additional questioning reveals a history of atopy, eczema, and asthma as a child. There is a strong family history of similar problems. This strikingly red, blistery-appearing rash is palm-sized and confined to the right groin. It has a fairly well–defined, scaly border that is KOH-negative on microscopic examination. Within the borders of this lesion are several focal, shiny, somewhat atrophic areas in which no epidermal adnexae (pores, follicles, hair, skin lines) can be seen.

Woman With Hip Pain After Car Accident

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of contrast material within the bladder. There is evidence of fixation of an old subcapital femoral neck fracture on the left.

There is an acute, mildly displaced right intertrochanteric fracture of the right hip. The orthopedic service was consulted, and plans were established to subsequently fix this fracture surgically.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of contrast material within the bladder. There is evidence of fixation of an old subcapital femoral neck fracture on the left.

There is an acute, mildly displaced right intertrochanteric fracture of the right hip. The orthopedic service was consulted, and plans were established to subsequently fix this fracture surgically.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of contrast material within the bladder. There is evidence of fixation of an old subcapital femoral neck fracture on the left.

There is an acute, mildly displaced right intertrochanteric fracture of the right hip. The orthopedic service was consulted, and plans were established to subsequently fix this fracture surgically.

A 55-year-old woman is transferred to your facility with injuries sustained in a motor vehicle collision. She was an unrestrained front-seat passenger in a vehicle that rear-ended another vehicle. There was no airbag deployment, and the patient believes she struck her face on the windshield. At the outside facility, it was determined that she had a cervical fracture and facial fractures. Upon arrival at your facility, she is complaining of bilateral hip pain as well. Her medical history is significant for coronary artery disease, several myocardial infarctions, hypertension, and stroke. She has a pacemaker. Six months ago, she had an open reduction internal fixation of her left hip for a fracture she sustained in a fall. Primary survey reveals a female who is uncomfortable but alert and oriented. Vital signs are normal. She has some facial swelling and bruising. Her heart and lungs are clear; abdomen is benign. She is able to move her upper extremities with-out any problems. She has limited movement of her lower extremities due to pain in her pelvis. She is able to move both feet and toes, and distal pulses and sensation are intact. No obvious leg shortening is noted. A portable radiograph of the pelvis is obtained. What is your impression?