User login

Child hit by car

ANSWER

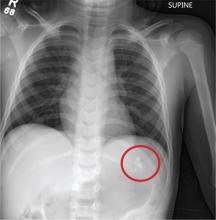

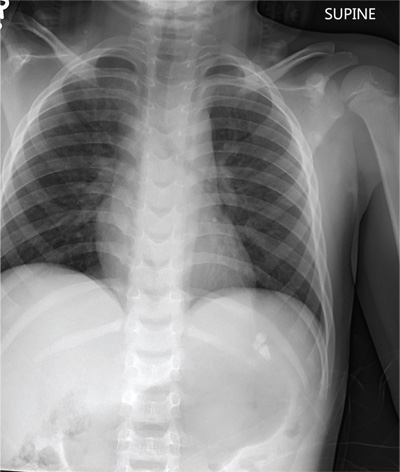

The chest radiograph demonstrates no acute abnormalities within the lungs, ribs, or chest. Of note, there are two radiodensities consistent with teeth, which are presumed to be in the patient’s stomach (most likely secondary to being swallowed following trauma to his face). Upon reexamination, it is noted that the child’s two front incisors are missing, with minimally bleeding sockets. Other than reassurance, no specific intervention was required.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates no acute abnormalities within the lungs, ribs, or chest. Of note, there are two radiodensities consistent with teeth, which are presumed to be in the patient’s stomach (most likely secondary to being swallowed following trauma to his face). Upon reexamination, it is noted that the child’s two front incisors are missing, with minimally bleeding sockets. Other than reassurance, no specific intervention was required.

ANSWER

The chest radiograph demonstrates no acute abnormalities within the lungs, ribs, or chest. Of note, there are two radiodensities consistent with teeth, which are presumed to be in the patient’s stomach (most likely secondary to being swallowed following trauma to his face). Upon reexamination, it is noted that the child’s two front incisors are missing, with minimally bleeding sockets. Other than reassurance, no specific intervention was required.

A 6-year-old boy is brought to your facility by ambulance after being hit by a car. The child was apparently riding his bike when a slow-moving vehicle turned onto the street and accidentally bumped him, knocking him to the ground. He was not wearing a helmet. The child is crying but somewhat consolable. His medical history is unremarkable. On initial assessment, he is awake, crying, and moving all of his extremities spontaneously. His vital signs include a temperature of 36.3°C; blood pressure, 149/72 mm Hg; pulse, 110 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min. Physical examination reveals several abrasions to his face, nose, and lips. Otherwise, he is normocephalic. His pupils are equal and react appropriately. Heart and lung sounds are clear, and the abdomen appears benign. You order some preliminary labwork and CT of the head. In addition, a portable chest radiograph is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

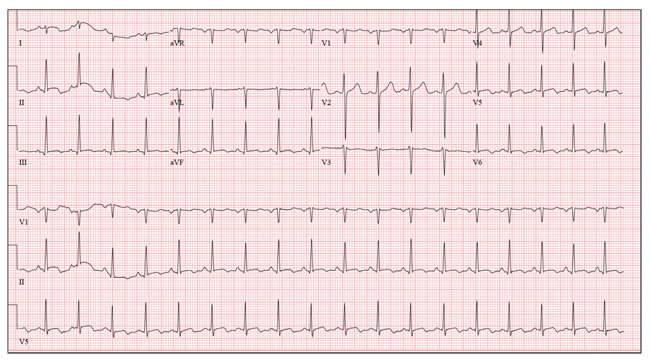

Is Active Patient a “Picture of Health”?

ANSWER

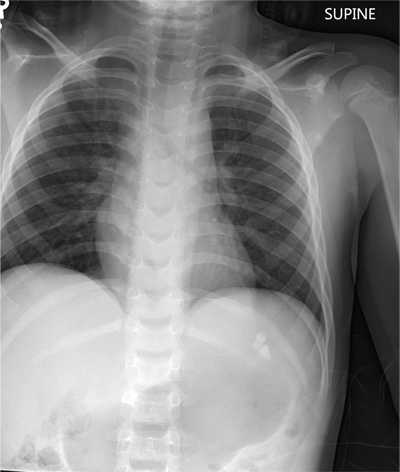

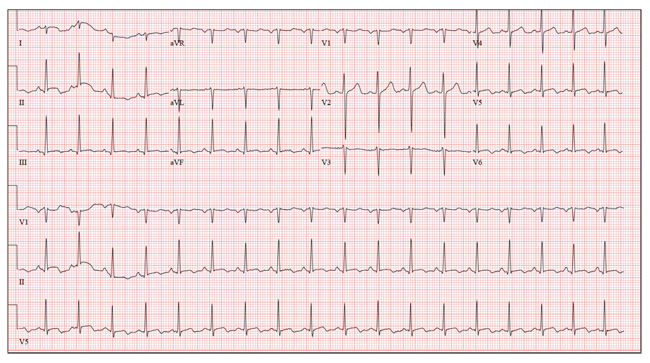

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia, a right bundle branch block, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate less than 60 beats/min and may be considered “marked” if the rate is less than 50 beats/min.

A right bundle branch block is indicated by a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and the presence of an RSR’ pattern in lead V1.

Small or nonexistent T waves in leads V5 and V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia but are not diagnostic in this individual.

His marked bradycardia was attributed to his exceptional athleticism and the fact that the ECG was taken “at rest.” It was not of concern, nor did it require treatment.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia, a right bundle branch block, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate less than 60 beats/min and may be considered “marked” if the rate is less than 50 beats/min.

A right bundle branch block is indicated by a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and the presence of an RSR’ pattern in lead V1.

Small or nonexistent T waves in leads V5 and V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia but are not diagnostic in this individual.

His marked bradycardia was attributed to his exceptional athleticism and the fact that the ECG was taken “at rest.” It was not of concern, nor did it require treatment.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia, a right bundle branch block, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a sinus rate less than 60 beats/min and may be considered “marked” if the rate is less than 50 beats/min.

A right bundle branch block is indicated by a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and the presence of an RSR’ pattern in lead V1.

Small or nonexistent T waves in leads V5 and V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia but are not diagnostic in this individual.

His marked bradycardia was attributed to his exceptional athleticism and the fact that the ECG was taken “at rest.” It was not of concern, nor did it require treatment.

A 62-year-old man presents for a preoperative history and physical exam prior to surgical repair of an injury to his right anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). He reports that he has been healthy all his life and has never had an injury or illness requiring hospitalization. He is an accountant at a local financial institution and has a very active lifestyle, which includes competitive cycling, running, and skiing. He recently completed his fourth triathlon and was training for his sixth marathon until his injury occurred. One week ago, he was skiing moguls on a black diamond course when he fell and tumbled about 20 feet before stopping. His right ski binding did not release from the boot. He felt his right knee “pop” and knew immediately that he had sustained a serious injury. When he tried to stand, he was unable to bear weight on his right leg. The ski patrol transported him off the slope via basket. He was then taken to a local hospital by a colleague. Physical exam and MRI confirmed an avulsion of the ACL. He has been convalescing at home (having delayed his surgery in order to catch up on paper-work for work) and is scheduled for surgery in two days’ time. Medical history is unremarkable. Aside from the usual childhood illnesses (eg, ear infections, chicken pox, mumps), he has been very healthy and attributes this to a strict diet and rigorous exercise. Social history reveals that he is married to an attorney and has no children. He has never smoked or taken recreational drugs, and he consumes approximately one bottle of wine per week. His current medications include naproxen as needed for pain, a daily aspirin, fish oil, a multivitamin, and omeprazole on rare occasions. The review of systems is remarkable only for occasional gastroesophageal re-flux, which is exacerbated by spicy dishes containing curry. Physical exam reveals a thin, athletic male in no acute distress. His weight is 168 lb, and his height is 74”. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 104/62 mm Hg; pulse, 50 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98°F. Examination of the head, neck, lungs, heart, abdomen, skin, and nervous system yields normal findings. Lachman, pivot shift, and anterior drawer maneuvers of the right knee are all positive. A routine ECG is performed that reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 49 beats/min; PR interval, 176 ms; QRS dura-tion, 120 ms; QT/QTc interval, 430/388 ms; P axis, 14°; R axis, 38°; and T axis, 103°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

A Compulsion to Scratch, But Is There an Itch?

ANSWER

The correct answer is neurotic excoriations (choice “d”), a chronic condition thought to be a psychologic process with dermatologic manifestations, consciously created by repetitive scratching and rubbing. Focally, it can manifest with skin alterations very similar to lichen simplex chronicus (choice “a”; also known as neurodermatitis), but the latter refers to very limited, localized processes and does not involve the psychiatric overlay seen with neurotic excoriations.

Patients with dermatitis artefacta (choice “b”; formerly called factitial dermatitis) consciously create their lesions for secondary gain, often using sharp objects such as nail files, kitchen utensils, or even shards of broken glass. Dermatitis artefacta lesions, which are relatively sparse and bizarre in appearance, can also be created by the application of caustic chemicals, or even by injection of foreign substances.

The differential rightly includes any number of skin conditions such as bullous pemphigoid (choice “c”). However, this was effectively ruled out by the biopsy and also by the morphology and extended chronicity of the patient’s complaint.

DISCUSSION

Neurotic excoriations (NE) are usually created by unconscious picking, scratching, or rubbing. There may be a precipitating minor skin pathology (eg, insect bite, folliculitis or acne), but it can develop independent of any such process. Its origins can often be tied to upsetting life events, such as divorce, death, or early dementia.

More history taking from this patient and her family revealed that her skin problems began after her husband died in an accident, after which, according to her children, “she has never been the same.” Her picking accelerated when she moved to an assisted living setting.

Because patients create neurotic excoriations, their lesions have the quality of an “outside job,” with clean linear erosions, crusts, and scars that can be hypopigmented or hyperpigmented, depending on the patient’s skin type. Similar in size and shape, the lesions tend to be bilaterally and symmetrically distributed and confined to areas within easy reach, such as the extensor surfaces of the arms and the upper part of the back.

The vast majority of NE patients are adult women, though it is also seen in children as a manifestation of comorbid psychopathology or other psychosocial stressor.

TREATMENT

As one might expect, treatment of NE is difficult, particularly since many patients find it impossible to accept the role their mental state plays in the creation and perpetuation of their condition. In the best of all possible scenarios, the patient would be seen and followed by a psychiatrist, who would probably prescribe psychoactive medication.

Failing that—or even in addition to that treatment—one could, at a minimum, find ways to distract the patient, trim her nails as much as possible, and/or place barriers between the offending nails and the skin in question.

Topical medications, such as steroid creams, are of very limited usefulness, as are oral antibiotics and antihistamines.

ANSWER

The correct answer is neurotic excoriations (choice “d”), a chronic condition thought to be a psychologic process with dermatologic manifestations, consciously created by repetitive scratching and rubbing. Focally, it can manifest with skin alterations very similar to lichen simplex chronicus (choice “a”; also known as neurodermatitis), but the latter refers to very limited, localized processes and does not involve the psychiatric overlay seen with neurotic excoriations.

Patients with dermatitis artefacta (choice “b”; formerly called factitial dermatitis) consciously create their lesions for secondary gain, often using sharp objects such as nail files, kitchen utensils, or even shards of broken glass. Dermatitis artefacta lesions, which are relatively sparse and bizarre in appearance, can also be created by the application of caustic chemicals, or even by injection of foreign substances.

The differential rightly includes any number of skin conditions such as bullous pemphigoid (choice “c”). However, this was effectively ruled out by the biopsy and also by the morphology and extended chronicity of the patient’s complaint.

DISCUSSION

Neurotic excoriations (NE) are usually created by unconscious picking, scratching, or rubbing. There may be a precipitating minor skin pathology (eg, insect bite, folliculitis or acne), but it can develop independent of any such process. Its origins can often be tied to upsetting life events, such as divorce, death, or early dementia.

More history taking from this patient and her family revealed that her skin problems began after her husband died in an accident, after which, according to her children, “she has never been the same.” Her picking accelerated when she moved to an assisted living setting.

Because patients create neurotic excoriations, their lesions have the quality of an “outside job,” with clean linear erosions, crusts, and scars that can be hypopigmented or hyperpigmented, depending on the patient’s skin type. Similar in size and shape, the lesions tend to be bilaterally and symmetrically distributed and confined to areas within easy reach, such as the extensor surfaces of the arms and the upper part of the back.

The vast majority of NE patients are adult women, though it is also seen in children as a manifestation of comorbid psychopathology or other psychosocial stressor.

TREATMENT

As one might expect, treatment of NE is difficult, particularly since many patients find it impossible to accept the role their mental state plays in the creation and perpetuation of their condition. In the best of all possible scenarios, the patient would be seen and followed by a psychiatrist, who would probably prescribe psychoactive medication.

Failing that—or even in addition to that treatment—one could, at a minimum, find ways to distract the patient, trim her nails as much as possible, and/or place barriers between the offending nails and the skin in question.

Topical medications, such as steroid creams, are of very limited usefulness, as are oral antibiotics and antihistamines.

ANSWER

The correct answer is neurotic excoriations (choice “d”), a chronic condition thought to be a psychologic process with dermatologic manifestations, consciously created by repetitive scratching and rubbing. Focally, it can manifest with skin alterations very similar to lichen simplex chronicus (choice “a”; also known as neurodermatitis), but the latter refers to very limited, localized processes and does not involve the psychiatric overlay seen with neurotic excoriations.

Patients with dermatitis artefacta (choice “b”; formerly called factitial dermatitis) consciously create their lesions for secondary gain, often using sharp objects such as nail files, kitchen utensils, or even shards of broken glass. Dermatitis artefacta lesions, which are relatively sparse and bizarre in appearance, can also be created by the application of caustic chemicals, or even by injection of foreign substances.

The differential rightly includes any number of skin conditions such as bullous pemphigoid (choice “c”). However, this was effectively ruled out by the biopsy and also by the morphology and extended chronicity of the patient’s complaint.

DISCUSSION

Neurotic excoriations (NE) are usually created by unconscious picking, scratching, or rubbing. There may be a precipitating minor skin pathology (eg, insect bite, folliculitis or acne), but it can develop independent of any such process. Its origins can often be tied to upsetting life events, such as divorce, death, or early dementia.

More history taking from this patient and her family revealed that her skin problems began after her husband died in an accident, after which, according to her children, “she has never been the same.” Her picking accelerated when she moved to an assisted living setting.

Because patients create neurotic excoriations, their lesions have the quality of an “outside job,” with clean linear erosions, crusts, and scars that can be hypopigmented or hyperpigmented, depending on the patient’s skin type. Similar in size and shape, the lesions tend to be bilaterally and symmetrically distributed and confined to areas within easy reach, such as the extensor surfaces of the arms and the upper part of the back.

The vast majority of NE patients are adult women, though it is also seen in children as a manifestation of comorbid psychopathology or other psychosocial stressor.

TREATMENT

As one might expect, treatment of NE is difficult, particularly since many patients find it impossible to accept the role their mental state plays in the creation and perpetuation of their condition. In the best of all possible scenarios, the patient would be seen and followed by a psychiatrist, who would probably prescribe psychoactive medication.

Failing that—or even in addition to that treatment—one could, at a minimum, find ways to distract the patient, trim her nails as much as possible, and/or place barriers between the offending nails and the skin in question.

Topical medications, such as steroid creams, are of very limited usefulness, as are oral antibiotics and antihistamines.

At her daughters’ insistence, this 69-year-old woman requests referral to dermatology for a skin condition that has been present for at least 20 years. During that time, she has seen many medical providers (including dermatologists) and has tried many different treatments (eg, creams, oral antibiotics, oral steroids, and antihistamines). While some of these helped a bit, most did not help at all—nor did the constant nagging at the patient by family and caregivers. Nonetheless, her daughters feel strongly that their mother is perpetuating the problem with her “scratching and picking.” They have observed that when she is able to leave her arms alone, the improvement in her skin is dramatic. For example, years ago, she broke her wrist and was placed in a cast for six weeks; when it was removed, the affected arm was completely clear (except for multiple old scars). Everyone, including the patient, was ecstatic—but a week later, the lesions returned. The extensor aspects of both arms and hands are covered with linear excoriations, scars, and scabs, with focal hyperpigmentation in many of the excoriated areas. Overall, the skin in these areas is re-markably thickened and focally shiny. Her skin elsewhere—such as her palms and the volar aspects of her arms—is relatively clear. Throughout the examination, the patient’s hands never stop rubbing and scratching her arms, even as she weakly denies doing so. “Whatever happens, I’m not going to see a shrink,” she says. Clearly, a biopsy is in order, with a sample taken from a typical section of her forearm. The results show minimal changes but demonstrate hyperkeratosis. Blood work, including a complete metabolic profile and complete blood count, fail to show any evidence of systemic disease.

Foot Pain Following a Car Crash

The radiograph demonstrates an acute fracture of the second, third, and fourth distal metatarsals. The third and fourth are mildly impacted.

In addition, there is a deformity noted within the medial cuneiform, strongly suggestive of a fracture. This was later confirmed by CT. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

The radiograph demonstrates an acute fracture of the second, third, and fourth distal metatarsals. The third and fourth are mildly impacted.

In addition, there is a deformity noted within the medial cuneiform, strongly suggestive of a fracture. This was later confirmed by CT. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

The radiograph demonstrates an acute fracture of the second, third, and fourth distal metatarsals. The third and fourth are mildly impacted.

In addition, there is a deformity noted within the medial cuneiform, strongly suggestive of a fracture. This was later confirmed by CT. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

Following a motor vehicle collision, a 60-year-old woman is brought in by emergency medical transport. She was a restrained driver in a vehicle that went out of control, hit a tree, and ended up in a ditch. There was a prolonged extrication time (> 30 minutes) due to extensive damage to the front of the vehicle. On arrival, the patient is awake and alert, complaining primarily of pain in her left hip and right foot. Her medical history is unremarkable. She has an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. Her vital signs are: blood pressure, 154/100 mm Hg; pulse, 108 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air. Primary survey is otherwise unremarkable. A series of radiographs are ordered; that of the right foot is shown. What is your impression?

Grad Student With Palpitations

ANSWER

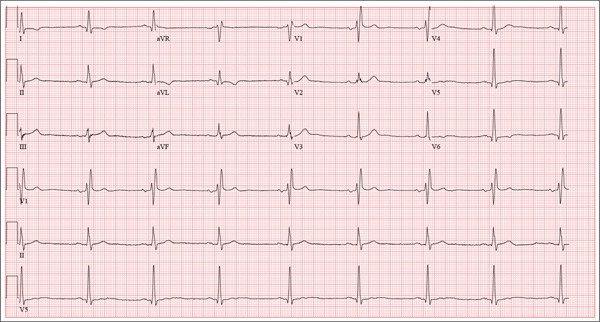

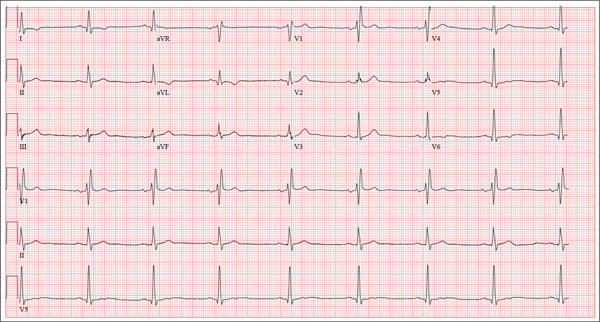

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with marked sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC).

Sinus rhythm is defined as a heart rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a P wave for every QRS complex, a QRS complex for every P wave, and a consistent PR interval between 120 and 200 ms.

A sinus arrhythmia is defined as a variation of the P-P interval ≥ 120 ms in the presence of normal P waves and a normal PR interval. The most common cause of a sinus arrhythmia is respiratory variation.

A blocked PAC is seen following the fifth QRS complex. Careful inspection of the terminal portion of the T wave reveals a P wave without a corresponding QRS complex. There is no QRS complex because the PAC occurs while the AV node is refractory. The subsequent pause occurs because the PAC blocks the sinus node and resets the sinus rate.

The palpitations were correlated to PACs observed on a continuous rhythm strip, and the patient was reassured.

A 24-year-old graduate student presents to the student clinic with a history of palpitations. He first noticed them while snowboarding two months ago, but says they’re now occurring daily and much more frequently. He is concerned about the risk for “another” episode of tachycardia, which, through careful questioning, you learn he has experienced twice before. He recalls that each of the episodes—which occurred while he was “pulling all-nighters” for final exams during his undergrad years—began abruptly and lasted for approximately an hour. He had no chest pain, symptoms of near-syncope, or syncope, but recalls feeling very “jittery,” which he attributed to drinking a full pot of coffee while studying. The patient has no prior cardiac or pulmonary history and considers himself to be in excellent health. He has run two half-marathons in the preceding six months and is an avid snowboarder. He also competes in local road cycling competitions with reasonable success. Medical history is remarkable only for fractures of the right ankle and the left clavicle. He takes no medications and has no drug allergies. Family history is significant for stroke (paternal grandfather), diabetes (maternal grandmother), and hypertension (father). He consumes alcohol socially, primarily on weekends, and does not binge drink. He smokes marijuana during snowboard season but denies use at other times of the year. A 12-point review of systems is positive only for athlete’s foot and psoriasis on both upper extremities. The physical exam reveals a healthy, athletic-appearing male in no distress. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 126/68 mm Hg; pulse, 78 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 99% on room air. He is afebrile. His height is 70” and weight, 158 lb. Auscultation of the heart reveals no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, but you do detect several pauses. As you listen, he emphatically states, “There’s one … there’s another.” Following the physical exam, the patient asks you to order an ECG. The resultant tracing reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 70 beats/min; PR interval, 178 ms; QRS duration, 90 ms; QT/QTc interval, 402/434 ms; P axis, 23°, R axis, 38°; and T axis, 31°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

An Encounter With Unflattering Light

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatoheliosis (choice “d”), also correctly termed photoaging. This condition manifests as a number of specific skin changes, including the items named (choices “a,” “b,” and “c”)—all of which were present on this patient.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronic overexposure to UV radiation constitute the most common reason patients present to dermatology practices in the United States. The bulk of this damage takes decades to appear, by which time patients have forgotten about their earlier sun exposure (in fact, they often deny any exposure) and even the painful sunburns that taught them to avoid the sun in the first place.

In general, the effects of sunburns sustained in childhood or young adulthood do not usually manifest until the patient is in his/her 50s or 60s, although patients who are less sun-tolerant (our definition of “fair”) may show signs of damage considerably earlier.

However, with the popularity of artificial tanning among teenagers (and even preteens in some cases), evidence of sun damage is being seen at younger ages than ever. Basal cell carcinomas, once unheard of in teenagers, are being found with increasing frequency in this age-group. In patients ages 12 to 15, there has been a 100-fold increase in the incidence of melanoma—theorized to be due, in part, to the effects of artificial tanning.

This particular patient is typical of cases in which sun damage was obtained more passively. At one time in the US, having a tan was decidedly unfashionable; it marked one as a member of “the lower classes.” But that all began to change after WWI: Hemlines and hairlines rose, Prohibition created a new generation of drinkers and scofflaws, clothing began to be more revealing, and suddenly it was fashionable for women to shave their legs and get a tan.

About that same time, many men began to ignore the long-held tradition of wearing hats and long sleeves when outside, inevitably tanned, and thus gained approval from the opposite sex. Most went off to war in the 1940s, many to the Pacific theater, where they had even more exposure to the sun.

Following WWII, a great number of these men returned to their jobs as farmers, ranchers, or construction workers. Golfing became the “in” sport during leisure time. It’s this generation we’re seeing now for sun-related pathology. Even if they had been inclined to use it, effective sunscreen was not generally available until the early 1970s.

The patient depicted here has a typical collection of the pre-cancerous sun damage known as dermatoheliosis: solar elastosis, actinic keratoses, telangiectasias, and solar atrophy (which affects the arms more than the face). The latter, along with the effects of wind, heat, cold, smoking, and drinking alcohol, constitute the main causes of extrinsic aging.

TREATMENT

Short of heroic efforts, not much will be done for this patient’s dermatoheliosis. However, he was strongly advised to return to dermatology twice a year to watch for the arrival of the basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas that are almost certainly headed his way.

During a recent trip, this 77-year-old man stayed in a hotel in which the bathroom lighting was considerably brighter than that at home—allowing him to see a number of skin changes he hadn’t noticed before. As a result, he presents to dermatology for an evaluation. The patient’s forehead, as well as his cheeks and nose, look curiously mottled (pink and white), with a rough, scar-like, pebbly surface that resembles chicken skin. There are also numerous 1- to 3-mm rough, scaly, papular lesions and multiple faint telangiectasias. In sun-exposed areas, such as his hands and arms, the skin is rough, dry, and exceptionally thin, with light and dark color changes; this is in sharp contrast to the relatively pristine texture and uniformly light color of the volar forearms and other areas that are not exposed to the sun. History taking reveals that, as a young man, the patient spent a great deal of time outdoors, both at work and in his free time. He never wore a hat or used any other form of sun protection. Since age 50, he has had several skin cancers removed from his face and back. Despite this, he is not seeing a dermatology provider regularly.

Drug Abuse Follows a Broken Heart

ANSWER

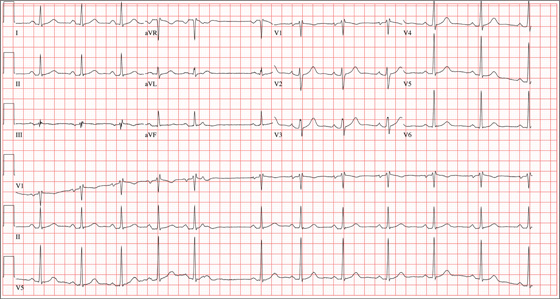

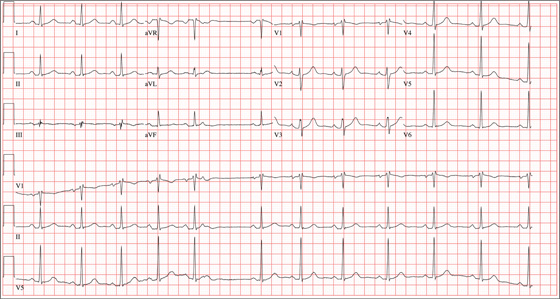

This ECG shows sinus tachycardia at a rate of 110 beats/min, evidenced by the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with regular R-R intervals. Left atrial enlargement is evident from the presence of P waves ≥ 110 ms (admittedly difficult to see in this example) and a terminal negativity of the P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2. A rightward axis is evidenced by the presence of an R-wave axis of 96°; however, it does not meet criteria for a true right-axis deviation

(≥ 105°). Nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are observed in leads V5 and V6.

The most intriguing aspect of this ECG is observed in lead V3. Note the abrupt disruption of R-wave progression between leads V2 and V4. This was due to incorrect placement of the ECG electrode for V3, which occurred in the haste to obtain the ECG prior to the CT scan. This illustrates the importance of correct electrode placement for an accurate tracing.

ANSWER

This ECG shows sinus tachycardia at a rate of 110 beats/min, evidenced by the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with regular R-R intervals. Left atrial enlargement is evident from the presence of P waves ≥ 110 ms (admittedly difficult to see in this example) and a terminal negativity of the P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2. A rightward axis is evidenced by the presence of an R-wave axis of 96°; however, it does not meet criteria for a true right-axis deviation

(≥ 105°). Nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are observed in leads V5 and V6.

The most intriguing aspect of this ECG is observed in lead V3. Note the abrupt disruption of R-wave progression between leads V2 and V4. This was due to incorrect placement of the ECG electrode for V3, which occurred in the haste to obtain the ECG prior to the CT scan. This illustrates the importance of correct electrode placement for an accurate tracing.

ANSWER

This ECG shows sinus tachycardia at a rate of 110 beats/min, evidenced by the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with regular R-R intervals. Left atrial enlargement is evident from the presence of P waves ≥ 110 ms (admittedly difficult to see in this example) and a terminal negativity of the P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2. A rightward axis is evidenced by the presence of an R-wave axis of 96°; however, it does not meet criteria for a true right-axis deviation

(≥ 105°). Nonspecific T-wave abnormalities are observed in leads V5 and V6.

The most intriguing aspect of this ECG is observed in lead V3. Note the abrupt disruption of R-wave progression between leads V2 and V4. This was due to incorrect placement of the ECG electrode for V3, which occurred in the haste to obtain the ECG prior to the CT scan. This illustrates the importance of correct electrode placement for an accurate tracing.

A 26-year-old man is brought to the emergency department (ED) by three friends who hadn’t seen him for two days and went to his apartment to check on him. They found him unconscious on the floor with four empty syringes on the coffee table beside him. The patient was aroused with difficulty but remained incoherent. Rather than call 911, they carried him to their car and brought him to the ED. According to his friends, he has been an IV drug abuser since breaking up with his girlfriend two years ago. He has been increasingly despondent over the past few days after seeing her with anoth-er man. The friends state that they know he has used heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and methamphet-amines in the past, but do not know what he used on this occasion. He has not had any prior illnesses, surgical procedures, or medical conditions that they are aware of. They do not know whether the patient is taking any prescription medications, nor whether he is aller-gic to any medications. According to one of the friends, the patient works with him as a welder at a local factory. He states the patient has been absent from work since last seeing his ex-girlfriend. You are unable to obtain a review of systems. A cursory examination reveals a thin, disheveled male who is unconscious but arousable. Blood pressure is 102/62 mm Hg, and pulse, 110 beats/min. Res-pirations are shallow at a rate of 20 breaths/min-1. Examination of the skin is remarkable for multiple recent and mature needle tracks in both upper ex-tremities, as well as multiple excoriations and shallow ulcers on both lower extremities. The EENT exam is remarkable for constricted pupils that react to light. Corneal reflexes are intact. The teeth are in poor repair with multiple caries and missing teeth. The neck veins are not distended, the thyroid is normal, and there are palpable lymph nodes in the left anterior cervical chain. The lungs have diffuse, scattered dry rales. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate at 110 beats/min with a soft, early systolic murmur best heard at the left upper sternal border. A rub is also present. Peripheral pulses are equal bilaterally in both upper and lower extremities. The abdomen is soft and nontender. The liver edge is palpable 2 cm below the right costal margin, and a firm spleen is palpable on the left. The neurologic exam reveals hyperactive deep tendon re-flexes in all four extremities. Laboratory samples are drawn; results are positive for cocaine, cannabis, and methamphetamine. Stat blood cultures are positive for Staphylococcus aureus, and the white blood count is 21,000/μL. A bedside echocardiogram performed in the ED shows evidence of a pericardial effusion and a perivalvular abscess on the septal side of the mitral valve, consistent with endocarditis. Prior to the patient’s transport to radiology for a CT scan, a quick ECG is performed. It reveals a ven-tricular rate of 110 beats/min; PR interval, 130 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 352/476 ms; P axis, 59°; R axis, 96°; and T axis, 106°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Wife Wants Husband’s “Zits” Gone!

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dilated pore of Winer (choice “b”), a hair structure anomaly discussed below. Sebaceous cysts (choice “a”) often present with a surface punctum, but the depth and appearance of this pore are not consistent with a simple punctum. The same could be said of the other two choices: ice-pick scar secondary to acne (choice “c”) and ingrown hair (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Dilated pore of Winer is actually a tumor of the intraepidermal follicle and related infundibulum of the pilosebaceous apparatus, a fact confirmed by immunohistochemical studies. It has no implication for health, but its appearance is occasionally distressing. Unfortunately, this patient has matching dilated pores on either side of his nose.

These scar-like pits are most commonly seen on the face, especially the maxillae. Even though they resemble one another, dilated pore of Winer differs significantly from a simple comedone: The former is considerably deeper, as well as markedly different in structure.

TREATMENT

The only effective treatment for dilated pore of Winer is surgical excision, which is easily accomplished under local anesthesia. A 4- to 5-mm punch biopsy tool is introduced into the skin at the same angle as the course of the pore, then taken down to adipose tissue, which ensures complete removal. Two interrupted skin sutures serve to convert the round punch defect into a linear wound, preferably matching skin tension lines. The tissue thus removed is always sent for pathologic examination to rule out basal cell carcinoma.

But for the vast majority of patients affected by dilated pore of Winer, the best treatment is to leave the lesions alone.

A 52-year-old man self-refers to dermatology, at his wife’s insistence, for evaluation of “big black-heads” that have been present on his maxillae for as long as he can remember. Periodically, he ex-presses cheesy, odoriferous material from them. He denies ever experiencing trauma in the area, and there is no history of other skin problems (eg, acne). His wife wants him to get these “black-heads” removed, because there is “dirt” in them. Small “holes” are seen on each side of the nose, about 3 cm lateral to midline. Each lesion is 2 to 3 mm wide and obviously deep. There is no comedonal material or protruding hair seen in the lesions; the surrounding skin is unchanged. Induration is absent in or around the lesions. No signs of active acne are seen elsewhere.

Cough and Back Pain in a Man With COPD

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some evidence of hyperinflated lungs, consistent with COPD. There is a small right effusion evident.

Of note is a superior mediastinal mass, which is causing right-sided and anterior displacement of the intrathoracic trachea. The differential includes possible adenopathy related to a carcinoma or a substernal goiter. Further diagnostic studies and surgical evaluation are warranted.

In this particular case, review of the patient’s imaging history showed he had a chest radiograph two years ago, at which time these findings were present. This favors substernal goiter as the diagnosis. Multinodular goiter was later confirmed with a thyroid ultrasound, and referral to general surgery was made.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some evidence of hyperinflated lungs, consistent with COPD. There is a small right effusion evident.

Of note is a superior mediastinal mass, which is causing right-sided and anterior displacement of the intrathoracic trachea. The differential includes possible adenopathy related to a carcinoma or a substernal goiter. Further diagnostic studies and surgical evaluation are warranted.

In this particular case, review of the patient’s imaging history showed he had a chest radiograph two years ago, at which time these findings were present. This favors substernal goiter as the diagnosis. Multinodular goiter was later confirmed with a thyroid ultrasound, and referral to general surgery was made.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows some evidence of hyperinflated lungs, consistent with COPD. There is a small right effusion evident.

Of note is a superior mediastinal mass, which is causing right-sided and anterior displacement of the intrathoracic trachea. The differential includes possible adenopathy related to a carcinoma or a substernal goiter. Further diagnostic studies and surgical evaluation are warranted.

In this particular case, review of the patient’s imaging history showed he had a chest radiograph two years ago, at which time these findings were present. This favors substernal goiter as the diagnosis. Multinodular goiter was later confirmed with a thyroid ultrasound, and referral to general surgery was made.

A 60-year-old man presents for evaluation of fever, cough, and back pain. His symptoms have been intermittent but have worsened over the past month or so. He has had no treatment prior to today’s visit. His medical history is significant for hypertension, COPD, and chronic renal insufficiency. He denies any history of tobacco use. On physical exam, you see an older man in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable. He is afe-brile, with a blood pressure of 150/90 mm Hg, a heart rate of 66 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min. His O2 saturation is 98% on room air. His neck is supple, with no evidence of ade-nopathy. Lung sounds are slightly decreased bilaterally, with a few crackles heard. The rest of his physical exam, overall, is normal. You order preliminary lab work as well as a chest radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Hand Slammed in Door

A 48-year-old woman presents to the urgent care center with complaints of right hand pain second-ary to an injury she sustained earlier in the day. Her hand was accidentally caught in a metal door as it was being shut by someone else. The door struck her in the middorsal aspect of her hand. She is now complaining of pain and swelling. She is healthy except for mild but well-controlled hypertension. Her vital signs are normal. Examina-tion of her right hand shows mild to moderate soft tissue swelling and some early bruising. There is extreme tenderness over the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones. Good capillary refill time is noted, and sensation is intact. She is able to flex her fingers somewhat, although this is limited by the swelling. Radiograph of the right hand is obtained. What is your impression?