User login

Wrist Pain After a Fall

A 90-year-old man is brought to your facility for evaluation after a fall. The patient states he was out in his yard, near his garden, when he “just passed out.” He landed in an ant bed and was eventually found by a neighbor, who brought him for evaluation. The patient says he has felt weak for the past several days. He has no other constitutional complaints. He is also experiencing bilateral wrist pain, he presumes as a result of receiving multiple ant bites. His medical history is significant for diabetes. His vital signs are normal. Inspection of both wrists demonstrates mild to moderate circumferential swelling with several raised, reddened bumps. Both wrists are tender; range of motion does cause some tenderness. Sensation is intact, and good capillary refill time is noted. While waiting for lab results, you obtain a radiograph of the left wrist (shown). What is your impression?

Childhood Problem Flares at Age 50

ANSWER

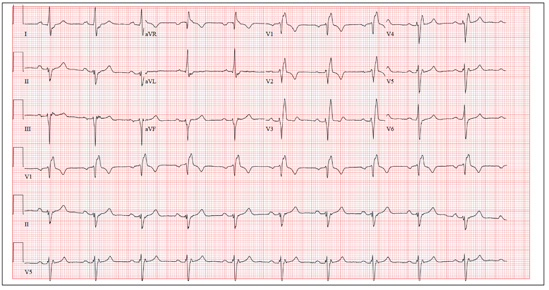

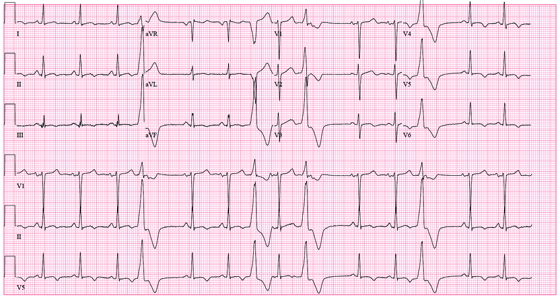

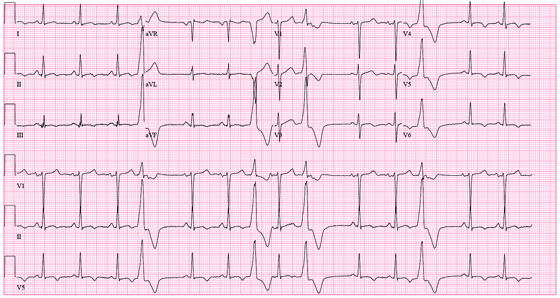

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a corresponding P for every QRS and a QRS for every P.

Right bundle branch block is evidenced by a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. Left anterior fascicular block is evident from the finding that the S waves are greater than the R waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

The presence of a right ventricular block and left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block) is consistent with a history of a VSD and/or surgical repair. The right and left bundles proceed from the atrioventricular node and bundle of His down the ventricular septum to the Purkinje fibers in the distal ventricular myocardium. Therefore, congenital anomalies of the ventricular septum, and/or surgical intervention within it, often affect conduction of the right and/or left bundle.

This patient’s symptoms were a result of his dilated aorta, and he underwent successful repair, with resolution of his symptoms.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a corresponding P for every QRS and a QRS for every P.

Right bundle branch block is evidenced by a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. Left anterior fascicular block is evident from the finding that the S waves are greater than the R waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

The presence of a right ventricular block and left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block) is consistent with a history of a VSD and/or surgical repair. The right and left bundles proceed from the atrioventricular node and bundle of His down the ventricular septum to the Purkinje fibers in the distal ventricular myocardium. Therefore, congenital anomalies of the ventricular septum, and/or surgical intervention within it, often affect conduction of the right and/or left bundle.

This patient’s symptoms were a result of his dilated aorta, and he underwent successful repair, with resolution of his symptoms.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min, with a corresponding P for every QRS and a QRS for every P.

Right bundle branch block is evidenced by a QRS duration > 120 ms, a terminal broad S wave in lead I, and an RSR’ complex in lead V1. Left anterior fascicular block is evident from the finding that the S waves are greater than the R waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

The presence of a right ventricular block and left anterior fascicular block (bifascicular block) is consistent with a history of a VSD and/or surgical repair. The right and left bundles proceed from the atrioventricular node and bundle of His down the ventricular septum to the Purkinje fibers in the distal ventricular myocardium. Therefore, congenital anomalies of the ventricular septum, and/or surgical intervention within it, often affect conduction of the right and/or left bundle.

This patient’s symptoms were a result of his dilated aorta, and he underwent successful repair, with resolution of his symptoms.

A man, 50, has a history of tetralogy of Fallot (ventricular septal defect [VSD], pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy, and overriding aorta). He underwent surgical correction at age 4, with placement of a Blalock-Taussig shunt and closure of his VSD, and was asymptomatic until one year ago. In the past year, he has developed progressive shortness of breath and dyspnea on exertion. In the past three months, he has developed chest pain that he describes as sharp, nonradiating, and occurring most often with dyspnea on exertion. He denies syncope, near-syncope, palpitations, or tachycardia. He cannot walk more than one-and-a-half blocks before stopping to rest, and he avoids hills and stairs if at all possible. A review of his most recent cardiac work-up (performed six months ago) reveals no significant coronary artery disease or evidence of aortic stenosis; it shows moderate aortic regurgitation, normal systolic aortic pressures, and normal left ventricular end diastolic pressures. The right ventricular pressures were elevated due to pulmonic stenosis; however, the estimated pulmonary artery pressures were normal. A cardiac MRI performed one month ago shows a significantly dilated aortic root with aneurysmal dilatation extending to the aortic arch, with effacement at the sinotubular junction and moderate aortic regurgitation. Additional findings include a markedly dilated right ventricular outflow tract with no pulmonic stenosis, evi-dence of a previous right Blalock-Taussig shunt, and moderate right atrial enlargement. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension. Family history is remarkable for hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease, but not congenital heart disease. The patient does not smoke and drinks socially on the weekends. His medications include amlodipine, aspirin, and lisinopril. He is allergic to penicillin and amox-icillin. A review of systems reveals that he has had flulike symptoms for the past four days, with a dry, nonproductive cough. Physical exam reveals a well-developed, obese male in no distress. His height is 67”and his weight, 208 lb. Blood pressure is 102/70 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. His oxygen saturation is 98% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include a grade II/VI holosystolic murmur and a grade III/VI diastolic murmur, with a prominent S2 best heard at the left lower sternal border. There is no jugular venous distention, no peripheral edema, and no abnormal pulmonary finding. An ECG previously ordered for today’s visit reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 63 beats/min; PR interval, 196 ms; QRS duration, 174 ms; QT/QTc inter-val, 460/470 ms; P axis, 34°; R axis, –67°; and T axis, 56°. What is your interpretation of this ECG? How does the patient’s history predict the findings?

Wife is Worried That Her Husband's Condition is Contagious

ANSWER

The correct answer is petaloid seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), named for the flowerlike appearance of its polycyclic borders. Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in this area, but tends to be scalier and usually involves multiple areas (eg, elbows, knees, and nails).

Rashes like this patient’s are often termed yeast infection (choice “b”). However, while a commensal yeast (Pityrosporum) can play a role in its formation, it appears that seborrhea represents an idiosyncratic reaction to increased numbers of this organism, rather than an actual infection.

Bowen’s disease (choice “c”) is a superficial squamous cell carcinoma, usually caused by overexposure to sunlight. Its lesions will be fixed, slowly growing larger with time, while seborrheic dermatitis will typically come and go. Biopsy is sometimes necessary to distinguish one from the other.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD, aka seborrhea) is common, affecting up to 5% of the population. Dandruff is its usual manifestation, but it affects numerous other areas (as in this case), including the axillae, groin, beard, and genitals.

Presenting with scaling on an erythematous base, SD often flares and remits with the season (especially winter), with stress, and with increases in alcohol intake. Although it is usually mild, some cases can be severe. SD is associated with or accentuated by several other conditions, including Parkinson’s, stroke, and HIV. Severe SD in infants raises the possibility of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, especially when the presentation is atypical.

The diagnosis of SD can be difficult when it appears elsewhere than the scalp and face (eg, as an axillary or genital rash). Likewise, sternal petaloid SD is mystifying, unless other corroboratory manifestations are sought and found.

A few patients show signs of SD and psoriasis such that a definitive diagnosis cannot be made. Such overlap cases are sometimes termed sebopsoriasis. But psoriasis will usually exhibit signs not seen with SD, such as pitting of the nails, involvement of extensor surfaces of elbows and knees, and characteristic signs of psoriatic arthropathy in about 20% of cases. Pinpoint bleeding caused by peeling away scale, called the Auspitz sign, is seen with psoriasis and not with SD.

TREATMENT

This patient’s chest involvement responded rapidly to topical betamethasone foam, quickly tapered to avoid thinning the skin. Less powerful steroid creams, lotions, or gels (eg, triamcinolone 0.025%) can be used on other areas, such as ears and face. The daily use of an OTC dandruff shampoo (containing selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, tar, or ketoconazole) is an effective approach to controlling scalp involvement, but the product should be changed weekly.

Once the initial inflammation is controlled, topical antiyeast/antifungal preparations (eg, ketoconazole cream or any of the imidazoles, such as clotrimazole or oxiconazole) can be useful.

Finally, emphasis must be placed on educating the patient to expect control of the condition but not a cure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is petaloid seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), named for the flowerlike appearance of its polycyclic borders. Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in this area, but tends to be scalier and usually involves multiple areas (eg, elbows, knees, and nails).

Rashes like this patient’s are often termed yeast infection (choice “b”). However, while a commensal yeast (Pityrosporum) can play a role in its formation, it appears that seborrhea represents an idiosyncratic reaction to increased numbers of this organism, rather than an actual infection.

Bowen’s disease (choice “c”) is a superficial squamous cell carcinoma, usually caused by overexposure to sunlight. Its lesions will be fixed, slowly growing larger with time, while seborrheic dermatitis will typically come and go. Biopsy is sometimes necessary to distinguish one from the other.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD, aka seborrhea) is common, affecting up to 5% of the population. Dandruff is its usual manifestation, but it affects numerous other areas (as in this case), including the axillae, groin, beard, and genitals.

Presenting with scaling on an erythematous base, SD often flares and remits with the season (especially winter), with stress, and with increases in alcohol intake. Although it is usually mild, some cases can be severe. SD is associated with or accentuated by several other conditions, including Parkinson’s, stroke, and HIV. Severe SD in infants raises the possibility of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, especially when the presentation is atypical.

The diagnosis of SD can be difficult when it appears elsewhere than the scalp and face (eg, as an axillary or genital rash). Likewise, sternal petaloid SD is mystifying, unless other corroboratory manifestations are sought and found.

A few patients show signs of SD and psoriasis such that a definitive diagnosis cannot be made. Such overlap cases are sometimes termed sebopsoriasis. But psoriasis will usually exhibit signs not seen with SD, such as pitting of the nails, involvement of extensor surfaces of elbows and knees, and characteristic signs of psoriatic arthropathy in about 20% of cases. Pinpoint bleeding caused by peeling away scale, called the Auspitz sign, is seen with psoriasis and not with SD.

TREATMENT

This patient’s chest involvement responded rapidly to topical betamethasone foam, quickly tapered to avoid thinning the skin. Less powerful steroid creams, lotions, or gels (eg, triamcinolone 0.025%) can be used on other areas, such as ears and face. The daily use of an OTC dandruff shampoo (containing selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, tar, or ketoconazole) is an effective approach to controlling scalp involvement, but the product should be changed weekly.

Once the initial inflammation is controlled, topical antiyeast/antifungal preparations (eg, ketoconazole cream or any of the imidazoles, such as clotrimazole or oxiconazole) can be useful.

Finally, emphasis must be placed on educating the patient to expect control of the condition but not a cure.

ANSWER

The correct answer is petaloid seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), named for the flowerlike appearance of its polycyclic borders. Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in this area, but tends to be scalier and usually involves multiple areas (eg, elbows, knees, and nails).

Rashes like this patient’s are often termed yeast infection (choice “b”). However, while a commensal yeast (Pityrosporum) can play a role in its formation, it appears that seborrhea represents an idiosyncratic reaction to increased numbers of this organism, rather than an actual infection.

Bowen’s disease (choice “c”) is a superficial squamous cell carcinoma, usually caused by overexposure to sunlight. Its lesions will be fixed, slowly growing larger with time, while seborrheic dermatitis will typically come and go. Biopsy is sometimes necessary to distinguish one from the other.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD, aka seborrhea) is common, affecting up to 5% of the population. Dandruff is its usual manifestation, but it affects numerous other areas (as in this case), including the axillae, groin, beard, and genitals.

Presenting with scaling on an erythematous base, SD often flares and remits with the season (especially winter), with stress, and with increases in alcohol intake. Although it is usually mild, some cases can be severe. SD is associated with or accentuated by several other conditions, including Parkinson’s, stroke, and HIV. Severe SD in infants raises the possibility of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, especially when the presentation is atypical.

The diagnosis of SD can be difficult when it appears elsewhere than the scalp and face (eg, as an axillary or genital rash). Likewise, sternal petaloid SD is mystifying, unless other corroboratory manifestations are sought and found.

A few patients show signs of SD and psoriasis such that a definitive diagnosis cannot be made. Such overlap cases are sometimes termed sebopsoriasis. But psoriasis will usually exhibit signs not seen with SD, such as pitting of the nails, involvement of extensor surfaces of elbows and knees, and characteristic signs of psoriatic arthropathy in about 20% of cases. Pinpoint bleeding caused by peeling away scale, called the Auspitz sign, is seen with psoriasis and not with SD.

TREATMENT

This patient’s chest involvement responded rapidly to topical betamethasone foam, quickly tapered to avoid thinning the skin. Less powerful steroid creams, lotions, or gels (eg, triamcinolone 0.025%) can be used on other areas, such as ears and face. The daily use of an OTC dandruff shampoo (containing selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, tar, or ketoconazole) is an effective approach to controlling scalp involvement, but the product should be changed weekly.

Once the initial inflammation is controlled, topical antiyeast/antifungal preparations (eg, ketoconazole cream or any of the imidazoles, such as clotrimazole or oxiconazole) can be useful.

Finally, emphasis must be placed on educating the patient to expect control of the condition but not a cure.

A 70-year-old man presents with a slightly itchy rash on his sternum that has appeared intermittently for years. Told it is “ringworm” by his primary care provider, the patient tried tolnaftate cream, to no avail. He is seeking additional consultation primarily because his wife is concerned she will catch the “infection.” The patient denies other skin problems, but then remembers that he has dandruff that flares from time to time, as well as a curious scaly red rash that “comes and goes” between his eyes, in his nasolabial folds, and behind his ears, especially in the winter. His father had similar problems. The patient is otherwise healthy, except for mild hypertension. The rash, located on the lower right sternum, measures about 6 cm at its largest dimension. Faintly pink, it has a papulosquamous surface, especially on its pol-ycyclic borders. Results of a KOH prep are negative for fungal elements. Elsewhere, a faintly scaly, orange-red rash is seen in the glabellar area and behind both ears. The man’s knees, elbows, and nails are free of any changes.

Elderly Woman with Shoulder Pain

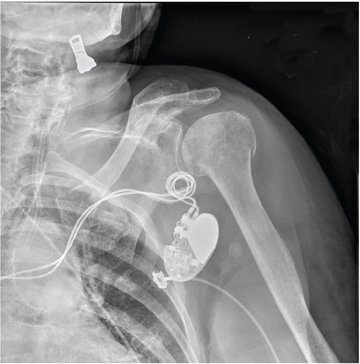

A 90-year-old woman is transferred to your facility from an outside hospital for evaluation of an intracranial hemorrhage secondary to a fall. The patient normally resides in a nursing home and has dementia. She was reportedly ambulating with her walker when she tripped and fell forward. In addition to dementia, her medical history is significant for sick sinus syndrome, for which she has a pacemaker. She also has hypertension and degenerative joint disease. Examination reveals an elderly female who is alert but very confused. Her vital signs are normal. She has moderate swelling and bruising on the left side of her forehead and left orbit. Her pupils react well. As you examine her, you note her unwillingness to use or move her left arm. When you inquire, she states, “It hurts.” Close examination of the left upper extremity shows no obvious deformity or swelling. She does have some tenderness over the left shoulder. You order a radiograph of the left shoulder (shown). What is your impression?

Dyspnea Confines Woman to Wheelchair

ANSWER

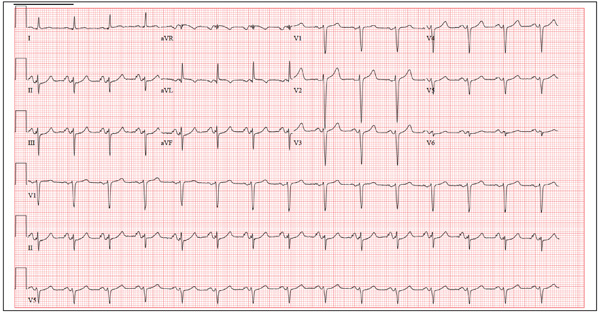

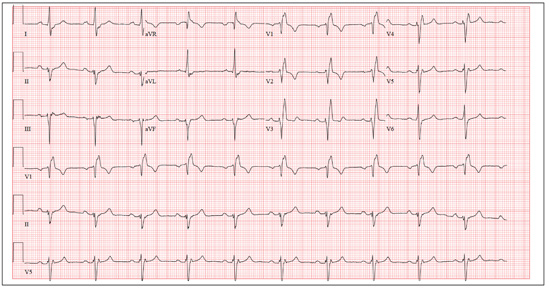

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, a left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an old anterolateral MI. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by the presence of a P wave for each QRS complex at a rate of 60 to 100 beats/min. Right atrial enlargement is diagnosed by the presence of tall, peaked P waves ≥ 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF, and is a result of the patient’s pulmonary hypertension (P pulmonale).

A left anterior fascicular block is evidenced by the presence of left-axis deviation (typically between –45° and –90°), small R and large S complexes in leads II, III, and aVF, small Q waves in leads I and aVL, a QRS duration < 120 ms, and poor R-wave progression in leads V1 to V3 and deep S waves in V5 to V6.

The usual criteria for an anterolateral MI include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V4 to V6 with ST-T wave changes. Poor R-wave progression in the absence of Q, QS, or QRS complexes in the anterolateral precordial leads (seen in this ECG) is also consistent with an old anterolateral MI.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, a left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an old anterolateral MI. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by the presence of a P wave for each QRS complex at a rate of 60 to 100 beats/min. Right atrial enlargement is diagnosed by the presence of tall, peaked P waves ≥ 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF, and is a result of the patient’s pulmonary hypertension (P pulmonale).

A left anterior fascicular block is evidenced by the presence of left-axis deviation (typically between –45° and –90°), small R and large S complexes in leads II, III, and aVF, small Q waves in leads I and aVL, a QRS duration < 120 ms, and poor R-wave progression in leads V1 to V3 and deep S waves in V5 to V6.

The usual criteria for an anterolateral MI include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V4 to V6 with ST-T wave changes. Poor R-wave progression in the absence of Q, QS, or QRS complexes in the anterolateral precordial leads (seen in this ECG) is also consistent with an old anterolateral MI.

ANSWER

The ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, a left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an old anterolateral MI. Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by the presence of a P wave for each QRS complex at a rate of 60 to 100 beats/min. Right atrial enlargement is diagnosed by the presence of tall, peaked P waves ≥ 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF, and is a result of the patient’s pulmonary hypertension (P pulmonale).

A left anterior fascicular block is evidenced by the presence of left-axis deviation (typically between –45° and –90°), small R and large S complexes in leads II, III, and aVF, small Q waves in leads I and aVL, a QRS duration < 120 ms, and poor R-wave progression in leads V1 to V3 and deep S waves in V5 to V6.

The usual criteria for an anterolateral MI include Q, QS, or QRS complexes in leads V4 to V6 with ST-T wave changes. Poor R-wave progression in the absence of Q, QS, or QRS complexes in the anterolateral precordial leads (seen in this ECG) is also consistent with an old anterolateral MI.

A 46-year-old woman is undergoing evaluation for consideration of heart transplantation versus left ventricular assist device placement as destination therapy. She has had a significant decline in her functional capacity in the past six months (sharpest in the past two months), and now can walk for only half a block be-fore becoming short of breath. For the past month, she has been unable to walk more than 100 feet without dyspnea and now confines herself to a wheelchair. Medical history is remarkable for type 1 diabetes requiring insulin pump therapy; multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) with angioplasty and stent placement; coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG; left internal thoracic artery graft to left anterior descending artery and reverse saphenous vein graft to the first obtuse marginal branch); an anterior wall myocardial infarction (MI) one year after her CABG; severe ischemic cardiomyopathy with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 18%; implantable defibrillator system for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death; pulmonary hypertension; and hyperlipidemia. Family history is remarkable for diabetes, MI, and sudden death. Social history reveals that despite her ill health, she continues to smoke 1½ packs of cigarettes per day, as she has for the past 30 years. She denies alcohol or illicit drug use. Her medication list is extensive: digoxin, atorvastatin, metoprolol, ramipril, spironolactone, torsemide, aspirin, clopidogrel, omeprazole, ondansetron, insulin pump, sildenafil, and sublingual nitroglycerin. She is allergic to penicillin and cephalosporins. The review of systems is remarkable for early satiety with occasional nausea and vomiting. She states she has difficulty sleeping, and her spouse states she snores very loudly and has witnessed several apneic spells. Physical examination reveals an anxious, obese woman sitting in a wheelchair. Blood pressure is 89/50 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 94% on room air; and temperature, 36.4°C. Pertinent physical findings include bilateral diabetic retinopathy, jugular venous pressures at 8 to 9 cm, brisk carotid upstrokes without bruits, and late expiratory wheezes in both lung bases. An implantable defibrillator is noted in the infraclavicular area on the left chest. The heart rate is regular, with a 3/6 holosystolic murmur (best heard at the left sternal border) that radiates to the left axilla. The abdomen is large, with the liver span palpable at the right costal margin, and an insulin pump is noted. The extremities reveal 2+ pitting edema to the knees bilaterally, and evidence of recent cellulitis is noted on the left leg below the knee. The neurologic exam is remarkable for diabetic paresthesias in both feet. As part of her work-up, an ECG is obtained and shows the following: a ventricular rate of 90 beats/min; PR interval, 138 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc inter-val, 370/450 ms; P axis, 81°; R axis, –48°; and T axis, 75°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Woman with Discomfort and Discoloration on Back

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema ab igne (choice “a”) caused, of course, by the effects of the heating pad. The reticular pattern and acute onset are quite characteristic of this unusual condition.

Contact dermatitis (choice “b”) would not have presented in this reticular pattern and would typically have itched intensely.

Cellulitis (choice “c”) represents a superficial infection usually caused by strep and/or staph. It would not have been reticular, would have been painful, and would have required a break in the skin for the offending organism to gain entrance.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA; choice “d”) describes vascular changes seen focally in patches that evolve slowly over months or even years. It is significant because of its reported potential to evolve into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; however, PVA does not present with a reticular pattern, nor does it appear acutely.

DISCUSSION

The superficial vascular plexus, configured in a reticular pattern and normally invisible, is sensitive to repeated exposure to the infrared portion of the magnetic spectrum (wavelength 700 to 1,100 nm). This exposure initially produces erythema, which over time turns livid, then permanently hyperpigmented.

Erythema ab igne (EAI) was classically seen in those sitting close to an open fire or stove (producing temperatures of 43°C to 47°C) for extended periods, often for hours each day. With the advent of central heating, other triggers of EAI evolved, including prolonged use of laptop computers, heating fans, and as in this case, heating pads. It can even be due to occupational exposure to intense heat, as with glassblowers, bakers, and steelworkers.

Most of the skin changes seen with EAI resemble those seen with chronic sun damage, including vasodilatation and melanin incontinence with melanophages in the upper dermis.

This particular patient had only one exposure to the heating pad, but had turned it on high and lain on it all night. This produced the changes seen, which will likely become permanently etched in her skin in the exact pattern of the causative heating pad. Months of dexamethasone therapy may also have contributed to the problem, by thinning the patient’s skin enough to render her susceptible to this single exposure to heat.

With EAI patients in general, thought needs to be given to possible underlying issues, such as the source of pain being treated with the heating pad—most commonly, on the low back—or the possible reason for constantly feeling cold, such as anemia or hypothyroidism.

Treatment choices include the application of tretinoin cream or 5-fluorouracil cream, or ablation with laser (YAG, ruby, alexandrite).

A 42-year-old woman presents with discoloration and discomfort involving her back. The discomfort, which started less than 24 hours ago, is not severe, but she is worried about the changes in color she can see in the mirror. Her history is significant for metastatic melanoma. She has been undergoing treatment with chemotherapy and localized radiation and for several months has been taking systemic steroids for intracerebral edema. Additional history taking reveals that the night before the appearance of the skin changes, she fell asleep lying on a heating pad because she was cold. She denies doing this habitually. Examination reveals a large patch of reticular erythema covering the entire central back, sharply sparing the area under the bra strap. The erythema is bounded laterally by sharply demarcated linear margins that mimic the exact shape and size of the heating pad in question. Focal blisters can be seen within the erythema, but the overall effect is macular (flat). Neither tenderness nor increased warmth is noted on palpation.

Elderly Man Failed To Mention Hip Pain After Fall

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates diffuse bony demineralization, as well as generalized degenerative changes. No obvious fracture or dislocation of the hip joint is seen.

Of note, though, are air lucencies within the area of the scrotum. This most likely represents a bowel finding and is strongly suggestive of an inguinal hernia. No acute intervention is warranted for this incidental finding; outpatient follow-up with general surgery was arranged.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates diffuse bony demineralization, as well as generalized degenerative changes. No obvious fracture or dislocation of the hip joint is seen.

Of note, though, are air lucencies within the area of the scrotum. This most likely represents a bowel finding and is strongly suggestive of an inguinal hernia. No acute intervention is warranted for this incidental finding; outpatient follow-up with general surgery was arranged.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates diffuse bony demineralization, as well as generalized degenerative changes. No obvious fracture or dislocation of the hip joint is seen.

Of note, though, are air lucencies within the area of the scrotum. This most likely represents a bowel finding and is strongly suggestive of an inguinal hernia. No acute intervention is warranted for this incidental finding; outpatient follow-up with general surgery was arranged.

An 87-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with a traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to a fall down some steps. He is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation; because his INR is elevated, he is placed in the ICU for close observation and warfarin reversal. His medical history is otherwise unremarkable, except for mild hypertension. During rounds, he complains of severe hip pain, possibly related to the fall. He admits that he “probably didn’t mention this” while he was in the emergency department. Physical examination demonstrates moderate tenderness and bruising in the left hip. No obvious leg shortening is noted. There is pain in the left hip with abduction and adduction, as well as with internal and external rotation. Good distal pulses are noted, as well as good color and sensation. His vital signs are normal. You order a portable pelvis radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Should This Fitness Instructor Worry About Her Heart?

ANSWER

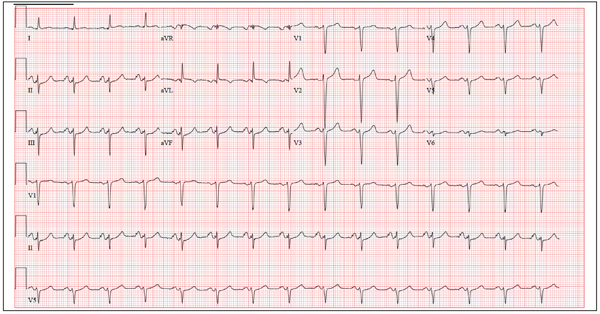

The ECG shows sinus tachycardia with premature atrial contractions. The premature atrial contractions occur at the 14th and 16th beats on the rhythm strip. They are evident by the shortened R-R interval preceding the beat, with the QRS complex appearing similar to the normal QRS complexes, signifying they propagate through the normal conduction system.

The P waves are hidden from view in the previous T wave. The nonspecific S- and T-wave abnormalities are physiologic in nature and of no consequence. Finally, the large S waves seen in the precordial leads are due to the patient’s thin body habitus and not to ventricular hypertrophy.

The patient was reassured that there were no structural abnormalities of her heart, and that there was no need to treat the premature contractions at this time. She was also asked to monitor her caffeine and energy drink intake to determine whether there was a correlation with her palpitations.

She was relieved to hear that there are no restrictions in her physical activity

ANSWER

The ECG shows sinus tachycardia with premature atrial contractions. The premature atrial contractions occur at the 14th and 16th beats on the rhythm strip. They are evident by the shortened R-R interval preceding the beat, with the QRS complex appearing similar to the normal QRS complexes, signifying they propagate through the normal conduction system.

The P waves are hidden from view in the previous T wave. The nonspecific S- and T-wave abnormalities are physiologic in nature and of no consequence. Finally, the large S waves seen in the precordial leads are due to the patient’s thin body habitus and not to ventricular hypertrophy.

The patient was reassured that there were no structural abnormalities of her heart, and that there was no need to treat the premature contractions at this time. She was also asked to monitor her caffeine and energy drink intake to determine whether there was a correlation with her palpitations.

She was relieved to hear that there are no restrictions in her physical activity

ANSWER

The ECG shows sinus tachycardia with premature atrial contractions. The premature atrial contractions occur at the 14th and 16th beats on the rhythm strip. They are evident by the shortened R-R interval preceding the beat, with the QRS complex appearing similar to the normal QRS complexes, signifying they propagate through the normal conduction system.

The P waves are hidden from view in the previous T wave. The nonspecific S- and T-wave abnormalities are physiologic in nature and of no consequence. Finally, the large S waves seen in the precordial leads are due to the patient’s thin body habitus and not to ventricular hypertrophy.

The patient was reassured that there were no structural abnormalities of her heart, and that there was no need to treat the premature contractions at this time. She was also asked to monitor her caffeine and energy drink intake to determine whether there was a correlation with her palpitations.

She was relieved to hear that there are no restrictions in her physical activity

A 38-year-old woman presents to your clinic with a two-year history of palpitations that have not increased in severity or frequency. Although they are bother-some, she has had no chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, or peripheral edema. She denies any symptoms of tachycardia, bradycardia, syn-cope, or near syncope. She works at a local health club as a Zumba instructor and teaches four spinning classes per week. She recently learned that the health club will be closing. As a result, until she finds another position, she will be without benefits. She states she wants to “get this checked out” before she loses her medical insurance. Medical history is unremarkable, with the exception of a right clavicle fracture sustained at age 15. She began menses at age 12, has never been pregnant, and has never had surgery. Family history is remarkable for hypertension and diabetes. Her parents and three siblings are alive and well. The patient has no known drug allergies. Her medications include ibuprofen as needed for musculoskeletal pain and an oral contraceptive. She denies recreational drug use. The review of systems is unremarkable, and her last menstrual period was 11 days ago. On physical exam, she is a thin, well-developed, athletic-appearing woman in no distress. Her height is 69”, and her weight is 144 lb. Blood pressure is 108/56 mm Hg; pulse, 58 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 beats/min; and temperature, 98.4°F. There are no murmurs, gallops, or rubs on her cardiac exam. Her lungs are clear. Her abdomen is flat and nontender, with good bowel tones in all quadrants. There is no peripheral edema. Peripheral pulses are full and bounding bilaterally in all four extremities. The neurologic exam is normal. A chemistry panel, complete blood count, lipid panel, and thyroid function studies are ordered; the results are all within normal limits. A transthoracic echocardiogram shows normal valves, normal wall motion, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 75%. A baseline ECG shows no ectopic beats. She is placed on a continuous rhythm monitor for 10 minutes, and no ectopic, premature, or dropped beats are seen. At that point, the patient remembers that the palpitations often occur just as she starts exercising, then go away once her heart rate is elevated. You have her do jumping jacks in the examination room for 30 seconds, and she states she can feel the palpitations. You quickly obtain an ECG, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 117 beats/min; PR interval, 158 ms; QRS duration, 110 ms; QT/QTc interval, 336/468 ms; P axis, 57°; R axis, 15°; and T axis, 153°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

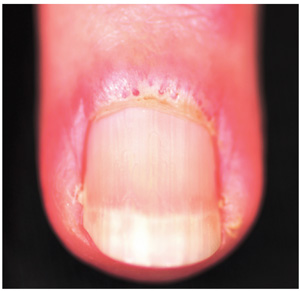

Skin Change and Fatigue Forces Woman to Take Leave of Absence

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

ANSWER

The correct answer is dermatomyositis (choice “c”), thought to be a vasculopathy mediated by the deposition of complement and lysis of capillaries in skin and muscle.

Carcinoid (choice “a”) is a rare tumor that can release vasoactive peptides, which cause episodic flushing, and if prolonged, can cause permanent changes in the skin. But carcinoid involves neither muscle weakness nor the particular skin changes seen with dermatomyositis.

Lupus erythematosus (choice “b”) can present with similar symptoms. However, when it affects the fingers, it specifically affects the interphalangeal skin, sharply sparing the knuckles. Both lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; choice “d”) can present with similar changes in the cuticles, but neither present with such profound muscle weakness.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is one of three main conditions that present with characteristic changes in the cuticular vasculature (the other two being scleroderma and MCTD). The definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rheumatologist, who is able to distinguish dermatomyositis from the rest of the differential—a process that can be rather complex.

The first diagnostic step is to identify the changes to the cuticular vasculature. These must be specifically sought; they are not always as obvious as in this case. Fortunately, magnification can easily be carried out with either an ophthalmoscope or dermatoscope, an examination enhanced by the application of oil first.

These findings, along with sunburn-like eruptions on the neck and face, should prompt laboratory testing. Significant results would include a positive antinuclear antibody test and elevations of the muscle enzymes creatine kinase and aldolase. Skin biopsy is helpful, though not diagnostic by itself. Additional studies might include a barium swallow, which would show weak pharyngeal muscles, and either an electromyography or MRI, which would demonstrate characteristic muscle changes secondary to inflammation.

Perhaps the most important aspect of dermatomyositis is its connection to cancer. A significant percentage of adults diagnosed with dermatomyositis will also have an associated and often occult malignancy, which may be found before, during, or after the diagnosis of dermatomyositis. (Juvenile dermatomyositis is not associated with malignancy.)

Patient age, constitutional symptoms, rapidity of onset, high level of serum muscle enzymes, grossly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and severity of dermatomyositis are all factors that would prompt an aggressive search for malignancies, the types of which mirror those seen in the general population. In such cases, surgical and/or medical cures of causative cancer usually stop the dermatomyositis as well.

The workup on this particular patient is still underway, but she is already responding to therapy with prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), to be taken until muscle enzymes are normal. This can take months, with dosage reduced as symptoms respond. Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, are often begun as prednisone levels are reduced.

SUGGESTED READING

James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Saunders; 2005:166-170.

Bergman R, Sharony L, Schapira D, et al. The handheld dermatoscope as a nail-fold capillaroscopic instrument. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(8): 1027-1030.

A three-month history of muscle weakness, fatigue, and skin changes prompts a 59-year-old woman to self-refer to dermatology. Otherwise healthy prior to the onset of these symptoms, she has had to take a leave of absence from work due to her inability to carry out her duties, which include light lifting and prolonged periods of time on her feet as a clerk in a pharmacy. She first consulted her primary care provider (PCP), who informed her that she was not anemic and did not have thyroid disease; the PCP felt that stress was probably a factor. She then purchased a number of products from her health food store, which she started taking until the skin on her hands began to change. On examination, atrophic pinkish red planar plaques are noted on 10/10 fingers, confined to the dorsal aspects of her joints and sharply sparing the interphalangeal spaces. The cuticles demonstrate the presence of dilated and irregularly shaped capillary loops. Several of her cuticles are also overgrown and frayed. Examination of the rest of the patient’s skin reveals a blanchable, faintly sunburned appearance to her anterior neck.

Woman with Metabolic Syndrome

ANSWER

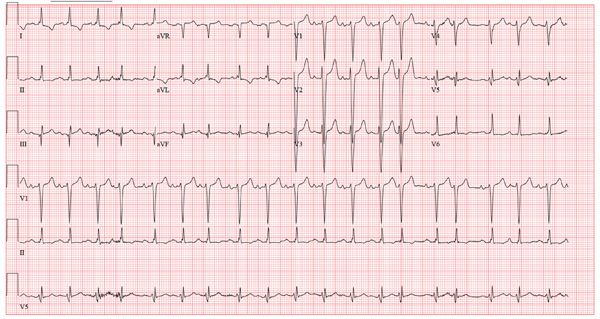

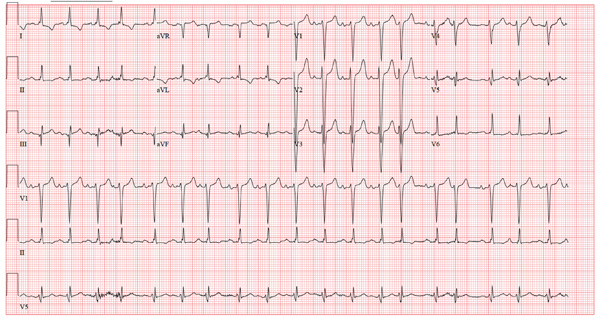

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), a T-wave abnormality suggesting lateral ischemia, and a prolonged QT interval.

PVCs occur when conduction of the ventricular myocardium occurs without involving the normal His-Purkinje system. They are responsible for the patient’s irregular pulse.

A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc interval > 440 ms. The QTc is calculated from Bazett’s formula, which states the QTc = QT interval divided by the square root of the previous R-R interval. The normal range for a QTc is generally considered to be 350 to 440 ms.

Inverted T waves in leads V3 to V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia. However, they are also seen in subacute or old pericarditis and myocarditis, so clinical correlation is required. The patient has had no recent or remote episodes of chest pain or chest discomfort in the past year.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), a T-wave abnormality suggesting lateral ischemia, and a prolonged QT interval.

PVCs occur when conduction of the ventricular myocardium occurs without involving the normal His-Purkinje system. They are responsible for the patient’s irregular pulse.

A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc interval > 440 ms. The QTc is calculated from Bazett’s formula, which states the QTc = QT interval divided by the square root of the previous R-R interval. The normal range for a QTc is generally considered to be 350 to 440 ms.

Inverted T waves in leads V3 to V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia. However, they are also seen in subacute or old pericarditis and myocarditis, so clinical correlation is required. The patient has had no recent or remote episodes of chest pain or chest discomfort in the past year.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), a T-wave abnormality suggesting lateral ischemia, and a prolonged QT interval.

PVCs occur when conduction of the ventricular myocardium occurs without involving the normal His-Purkinje system. They are responsible for the patient’s irregular pulse.

A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc interval > 440 ms. The QTc is calculated from Bazett’s formula, which states the QTc = QT interval divided by the square root of the previous R-R interval. The normal range for a QTc is generally considered to be 350 to 440 ms.

Inverted T waves in leads V3 to V6 are suggestive of lateral ischemia. However, they are also seen in subacute or old pericarditis and myocarditis, so clinical correlation is required. The patient has had no recent or remote episodes of chest pain or chest discomfort in the past year.

A 50-year-old woman with metabolic syndrome presents for a routine clinic appointment. You quickly review the five criteria of metabolic syndrome: • Fasting blood glucose ≥ 110 mg/dL • Waist circumference ≥ 40” in men or ≥ 35” in women • Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL • HDL cholesterol < 40 ¬mg/dL in men or < 50 mg/dL in women • Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mm Hg. The patient’s last clinic visit was four months ago; since then, she has done well and has no specific complaints or concerns. She denies angina, palpitations, dizziness, syncope, or dyspnea. Medical history is significant for New York Heart Association class III heart failure and cardiomyopathy secondary to myopericarditis with small-vessel coronary artery disease, as well as depression with anxiety. She also has a history of obstructive sleep apnea, but refuses to use a constant positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine at night due to claustrophobia. She attempts to control her diabetes with diet and exercise but admits she isn’t very compliant. Her medication list includes amlodipine, furosemide, carvedilol, lisinopril, isosorbide dinitrate, hydralazine, spironolactone, simvastatin, citalopram, omeprazole, and oxybutynin. She is allergic to ampicillin, methocarbamol, and codeine. The patient’s family history is unknown, as she was adopted. She works as a comptroller for a municipality in the suburbs, is recently divorced, and does not smoke or drink. Her review of systems is remarkable for headaches, anxiety, and loneliness following her divorce. She denies thoughts of injuring herself or suicide. Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 118/64 mm Hg; pulse, 88 beats/min and irregular; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99.2°F. Her weight is unchanged from her last visit. Her lungs are clear bilaterally, the jugular venous pressure is approximately 4 cm, and her cardiac exam reveals no murmurs, rubs, or extra heart sounds. Her abdomen is benign, and she has strong pulses bilaterally with 1+ pitting edema in both lower extremities, limited to the ankles. Laboratory data demonstrate chemical and lipid profiles and complete blood count within normal limits. An echocardiogram performed at her previous visit showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45%, with a mildly enlarged left ventricle, normal right ventricular size and function, and no valvular anomalies. It has been a year since her last ECG, so you decide to order one. It reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 87 beats/min; PR interval, 138 ms; QRS duration, 86 ms; QT/QTc interval, 388/466 ms; P axis, 61°; R axis, 43°; and T axis, 9°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?