User login

Why This Child Hates to Put On Socks

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

ANSWER

The correct answer is juvenile plantar dermatosis (JPD; choice “b”). It is a condition related to having thin, dry, hyperreactive skin exposed to friction, wetting and drying, and constant exposure to the nonpermeable surfaces of shoes.

Pitted keratolysis (choice “a”) is a condition caused by sweating and increased warmth. The plantar keratin is broken down with the help of bacteria that overgrow in affected areas; this eventuates in focal loss of keratin in arcuate patterns. It is quite unlikely to occur prior to puberty.

Tinea pedis (choice “c”) is dermatophytosis, or fungal infection of the foot. It is also unusual prior to puberty, unlikely to present in the manner seen in this case, and likely to have responded at least partially to antifungal creams.

Psoriasis (choice “d”) seldom presents with fissuring, would not be confined to weight-bearing surfaces, and would probably have involved other areas, such as the scalp, elbows, knees, or nails.

DISCUSSION

JPD, also known as juvenile plantar dermatitis, is found almost exclusively on the weight-bearing surfaces of the feet of children ages 4 to 8—mostly boys, for whom this represents a manifestation of the atopic diathesis. Seen mostly in the summer, it is thought to be triggered by friction, wetting and drying, and shoe selection (ie, plastic rather than leather soles).

Affected children not only have dry, sensitive skin; their skin is actually thin and fragile as well. Plastic or other synthetic shoe surfaces worn in the summertime are thought to contribute to the friction, heat, and sweating necessary to produce these changes.

As in this case, JPD is often mistaken for tinea pedis but has nothing to do with infection of any kind. Tinea pedis is uncommon in children this young, and it would present in completely different ways, such as between the toes (especially the fourth and fifth) or with blisters on the instep.

Psoriasis, though not unknown in this age-group, does not resemble JPD clinically at all. When suspected, the diagnosis of psoriasis can be corroborated by finding it elsewhere (eg, through a positive family history or biopsy).

Pitted keratolyis is common enough, but is seen in older teens and men whose feet are prone to sweat a great deal. The choice of shoes and occupation are often crucial factors in its development. The clinical hallmark is arcuate whitish maceration on weight-bearing surfaces, which are often malodorous as well.

TREATMENT

The first treatment for JPD is education of parents and patients, reassuring them about the relatively benign nature of the problem. Moisturizing frequently with petrolatum-based moisturizers is necessary for prevention, but changing the type of shoes worn is the most effective step to take; it is also the most difficult, since children this age favor cheap, plastic flip-flops or shoes in the summer.

For the fissures, spraying on a flexible spray bandage can be helpful in protecting them and allowing them to heal. With significant inflammation, the use of mild steroid ointments, such as hydrocortisone 2.5%, can help. But by far, the best relief comes with the change in season and the choice of shoe (leather-soled).

The distraught mother of an 8-year-old boy brings him urgently to dermatology for evaluation of a condition that has affected his feet for the past two summers. Convinced he has “caught” athlete’s foot, she tried several OTC antifungal creams and sprays, with no good effect. The patient denies symptoms except occasional stinging. In his view, the biggest problem is that the bottoms of his feet are so rough that he hates to put on socks. Additional history taking reveals that the child is markedly atopic, with seasonal allergies, asthma, dry, sensitive skin, and eczema. As an infant, his diaper rashes were so severe that he was hospitalized twice. On inspection, the weight-bearing surfaces of both feet are fissured and shiny, with modest inflammation evident. The plantar aspects of both big toes are especially affected. Though these areas are rough and dry, there is no edema, increased warmth, or tenderness on palpation. His skin elsewhere, though dry, is free of obvious lesions.

Underlying Factors Influence Insulin's Effect

Q: Help! How do you proceed if, after you’ve continually increased a patient’s insulin dose, his/her blood glucose levels do not improve?

This is a common scenario in diabetes management. Here are nine things to consider when a patient’s situation just doesn’t make sense clinically:

1. Noncompliance with the prescribed dose. This is the most common scenario. Ask the patient, “How many injections do you miss in a typical week?” Assure that he or she is actually taking the currently prescribed amount of insulin before you further increase the dose.

2. Inaccurate insulin dosing. This problem can be due to impaired vision, poor technique, dexterity issues, or dementia. Ask the patient to demonstrate for you how he/she draws up and takes the insulin at home. You might just be surprised at what you see, even in patients who have been giving themselves insulin for years. Consider prescribing an insulin pen or having a family member or significant other dose the insulin if the patient is no longer reliable to accurately dose it for him- or herself.

3. “Bad insulin.” What this actually means is loss of potency. This can be caused by improper storage, exposure to heat or cold, or use of an insulin delivery device (ie, vial or pen) past the 28- to 45-day period recommended, depending on the type of insulin. Replace the vial or pen and re-assess for improvement in diabetes control.

4. Lipohypertrophy of injection sites due to overuse. Palpate and visually inspect injection sites to look for firm or hypertrophied tissue. Advise the patient to avoid these areas for future injection, as absorption from these sites can be poor and unpredictable.

5. Dietary issues. The patient may be increasing his/her food intake along with the increased insulin doses. One clue that should raise suspicion for this occurrence is rapidly increasing body weight. Consider referring the patient to a dietitian for nutrition counseling.

6. New medication. Sometimes a new treatment is added to a patient’s regimen by another provider, and the medication might have an adverse effect on blood glucose control. Common examples include steroids (typically a cortisone injection) or methylprednisolone dose-packs taken during an asthma flare.

7. Occult infection. Urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and the like can impact blood glucose control. Consider ordering a urinalysis and complete blood count if infection seems a likely cause.

8. Major life stressors. Inquire as to what is happening in the patient’s life that might impact his/her body’s response to insulin. They might be in the middle of a divorce or other family crisis or experiencing severe stress at work.

9. Technique and equipment issues. Inaccurate glucose monitoring technique or use of expired strips can lead to “false high” readings. Also, patients with a continuous glucose monitor may record false high results when they are taking acetaminophen. If this is the case, increasing the insulin dose will often result in hypoglycemia.

It may be helpful to keep this clinical checklist handy and add to it any other issues that you come across when the clinical picture doesn’t make sense. You may also want to consider referral to a diabetes educator; patients will often confide what is really going on to an educator in a longer visit, rather than in the typically shorter visits with their health care provider.

SUGGESTED READING

Sadler C, Einhorn D. Tailoring insulin regimens for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAAPA. 1998;11(4):55-71.

Q: Help! How do you proceed if, after you’ve continually increased a patient’s insulin dose, his/her blood glucose levels do not improve?

This is a common scenario in diabetes management. Here are nine things to consider when a patient’s situation just doesn’t make sense clinically:

1. Noncompliance with the prescribed dose. This is the most common scenario. Ask the patient, “How many injections do you miss in a typical week?” Assure that he or she is actually taking the currently prescribed amount of insulin before you further increase the dose.

2. Inaccurate insulin dosing. This problem can be due to impaired vision, poor technique, dexterity issues, or dementia. Ask the patient to demonstrate for you how he/she draws up and takes the insulin at home. You might just be surprised at what you see, even in patients who have been giving themselves insulin for years. Consider prescribing an insulin pen or having a family member or significant other dose the insulin if the patient is no longer reliable to accurately dose it for him- or herself.

3. “Bad insulin.” What this actually means is loss of potency. This can be caused by improper storage, exposure to heat or cold, or use of an insulin delivery device (ie, vial or pen) past the 28- to 45-day period recommended, depending on the type of insulin. Replace the vial or pen and re-assess for improvement in diabetes control.

4. Lipohypertrophy of injection sites due to overuse. Palpate and visually inspect injection sites to look for firm or hypertrophied tissue. Advise the patient to avoid these areas for future injection, as absorption from these sites can be poor and unpredictable.

5. Dietary issues. The patient may be increasing his/her food intake along with the increased insulin doses. One clue that should raise suspicion for this occurrence is rapidly increasing body weight. Consider referring the patient to a dietitian for nutrition counseling.

6. New medication. Sometimes a new treatment is added to a patient’s regimen by another provider, and the medication might have an adverse effect on blood glucose control. Common examples include steroids (typically a cortisone injection) or methylprednisolone dose-packs taken during an asthma flare.

7. Occult infection. Urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and the like can impact blood glucose control. Consider ordering a urinalysis and complete blood count if infection seems a likely cause.

8. Major life stressors. Inquire as to what is happening in the patient’s life that might impact his/her body’s response to insulin. They might be in the middle of a divorce or other family crisis or experiencing severe stress at work.

9. Technique and equipment issues. Inaccurate glucose monitoring technique or use of expired strips can lead to “false high” readings. Also, patients with a continuous glucose monitor may record false high results when they are taking acetaminophen. If this is the case, increasing the insulin dose will often result in hypoglycemia.

It may be helpful to keep this clinical checklist handy and add to it any other issues that you come across when the clinical picture doesn’t make sense. You may also want to consider referral to a diabetes educator; patients will often confide what is really going on to an educator in a longer visit, rather than in the typically shorter visits with their health care provider.

SUGGESTED READING

Sadler C, Einhorn D. Tailoring insulin regimens for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAAPA. 1998;11(4):55-71.

Q: Help! How do you proceed if, after you’ve continually increased a patient’s insulin dose, his/her blood glucose levels do not improve?

This is a common scenario in diabetes management. Here are nine things to consider when a patient’s situation just doesn’t make sense clinically:

1. Noncompliance with the prescribed dose. This is the most common scenario. Ask the patient, “How many injections do you miss in a typical week?” Assure that he or she is actually taking the currently prescribed amount of insulin before you further increase the dose.

2. Inaccurate insulin dosing. This problem can be due to impaired vision, poor technique, dexterity issues, or dementia. Ask the patient to demonstrate for you how he/she draws up and takes the insulin at home. You might just be surprised at what you see, even in patients who have been giving themselves insulin for years. Consider prescribing an insulin pen or having a family member or significant other dose the insulin if the patient is no longer reliable to accurately dose it for him- or herself.

3. “Bad insulin.” What this actually means is loss of potency. This can be caused by improper storage, exposure to heat or cold, or use of an insulin delivery device (ie, vial or pen) past the 28- to 45-day period recommended, depending on the type of insulin. Replace the vial or pen and re-assess for improvement in diabetes control.

4. Lipohypertrophy of injection sites due to overuse. Palpate and visually inspect injection sites to look for firm or hypertrophied tissue. Advise the patient to avoid these areas for future injection, as absorption from these sites can be poor and unpredictable.

5. Dietary issues. The patient may be increasing his/her food intake along with the increased insulin doses. One clue that should raise suspicion for this occurrence is rapidly increasing body weight. Consider referring the patient to a dietitian for nutrition counseling.

6. New medication. Sometimes a new treatment is added to a patient’s regimen by another provider, and the medication might have an adverse effect on blood glucose control. Common examples include steroids (typically a cortisone injection) or methylprednisolone dose-packs taken during an asthma flare.

7. Occult infection. Urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and the like can impact blood glucose control. Consider ordering a urinalysis and complete blood count if infection seems a likely cause.

8. Major life stressors. Inquire as to what is happening in the patient’s life that might impact his/her body’s response to insulin. They might be in the middle of a divorce or other family crisis or experiencing severe stress at work.

9. Technique and equipment issues. Inaccurate glucose monitoring technique or use of expired strips can lead to “false high” readings. Also, patients with a continuous glucose monitor may record false high results when they are taking acetaminophen. If this is the case, increasing the insulin dose will often result in hypoglycemia.

It may be helpful to keep this clinical checklist handy and add to it any other issues that you come across when the clinical picture doesn’t make sense. You may also want to consider referral to a diabetes educator; patients will often confide what is really going on to an educator in a longer visit, rather than in the typically shorter visits with their health care provider.

SUGGESTED READING

Sadler C, Einhorn D. Tailoring insulin regimens for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAAPA. 1998;11(4):55-71.

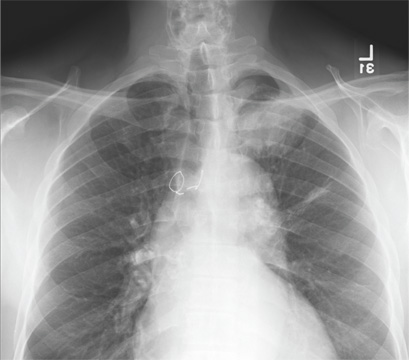

Is Chest Pain Related to Prior Fracture?

ANSWER

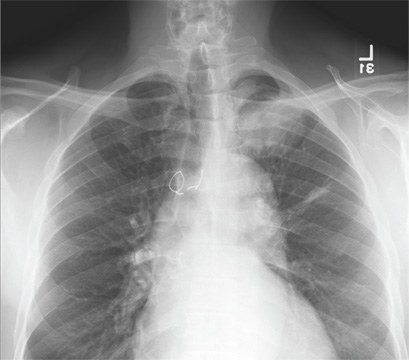

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous surgery on the sternum. There also is evidence of scarring or discoid atelectasis along the left mid lung.

Of note, though, is a soft tissue mass (about 5 to 6 cm) within the left pulmonary apex. This lesion could represent a rounded infiltrate, an atypical infection such as a mycetoma, or possibly a pulmonary neoplasm.

Since the patient was stable, he was placed on antibiotics with instructions to follow up with his primary care provider for further work-up on the mass. The patient did follow up; the lesion persisted and subsequent biopsy confirmed carcinoma.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous surgery on the sternum. There also is evidence of scarring or discoid atelectasis along the left mid lung.

Of note, though, is a soft tissue mass (about 5 to 6 cm) within the left pulmonary apex. This lesion could represent a rounded infiltrate, an atypical infection such as a mycetoma, or possibly a pulmonary neoplasm.

Since the patient was stable, he was placed on antibiotics with instructions to follow up with his primary care provider for further work-up on the mass. The patient did follow up; the lesion persisted and subsequent biopsy confirmed carcinoma.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates evidence of previous surgery on the sternum. There also is evidence of scarring or discoid atelectasis along the left mid lung.

Of note, though, is a soft tissue mass (about 5 to 6 cm) within the left pulmonary apex. This lesion could represent a rounded infiltrate, an atypical infection such as a mycetoma, or possibly a pulmonary neoplasm.

Since the patient was stable, he was placed on antibiotics with instructions to follow up with his primary care provider for further work-up on the mass. The patient did follow up; the lesion persisted and subsequent biopsy confirmed carcinoma.

A 61-year-old man presents to your urgent care center for evaluation of “chest pain” he has been experiencing for almost four weeks. He denies any injury or trauma. He describes the pain as “sharp” and “stabbing” and says occasionally it is associated with breathing, localized primarily to the left side. There is no radiation of the pain. He denies fever, nausea, weight loss, night sweats, and hemoptysis. He has smoked a half-pack of cigarettes daily for more than 40 years. His medical history is otherwise unremarkable, except that he was told he had “high blood pressure” and he had his sternum repaired several years ago, following fracture in an accident. Vital signs are as follows: temperature, 36.4°C; blood pressure, 174/100 mm Hg; ventricular rate, 88 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 100% on room air. He appears to be in no obvious distress. Lung sounds are normal, as is the rest of the physical examination. You obtain a chest radiograph. What is your impression?

Man in Distress With Lower Extremity Pain

ANSWER

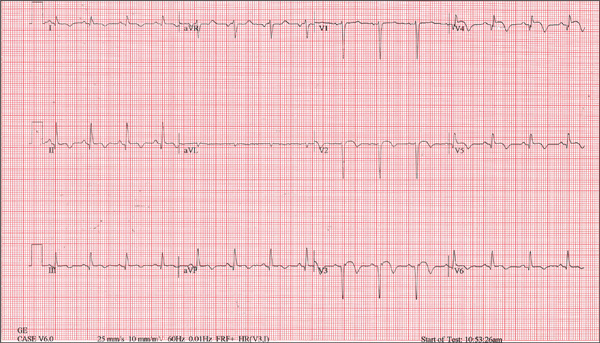

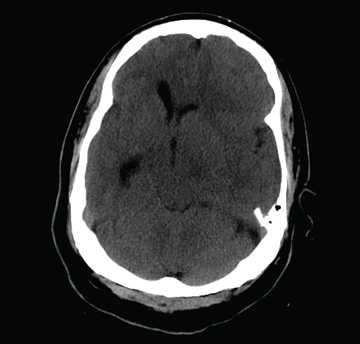

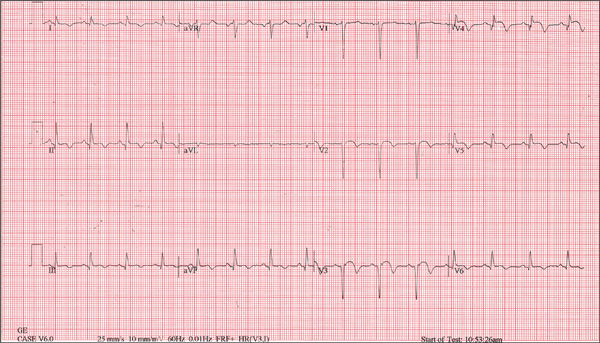

The ECG is diagnostic for a septal and anterolateral ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), suggestive of a recent MI versus left ventricular aneurysm. The ECG is also diagnostic for a recent inferior wall STEMI.

There are Q waves in leads V1 to V5 and a 2-mm ST elevation in V2 to V6, as well as a T-wave inversion (TWI) in V2 to V6 and lead 1. A 1-mm ST elevation, TWI, and small Q waves are noted in leads II, III, and aVF (inferior leads).

The patient’s abnormal troponin T level assisted with the differential diagnosis. The patient’s normal CK-MB pattern, combined with an elevated troponin T with ECG changes and chest pain reported about one week earlier, supported the diagnosis of a recent acute MI (within the past week).

The stress test was canceled. Cardiac catheterization was performed and showed a 100% mid left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis, with left to left collaterals, and an 80% right coronary artery (RCA) stenosis. No left ventricular aneurysm was noted.

Interventions included an urgent percutaneous intervention (PCI) coronary stent placement to the LAD and a staged PCI to the RCA at a later date.

ANSWER

The ECG is diagnostic for a septal and anterolateral ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), suggestive of a recent MI versus left ventricular aneurysm. The ECG is also diagnostic for a recent inferior wall STEMI.

There are Q waves in leads V1 to V5 and a 2-mm ST elevation in V2 to V6, as well as a T-wave inversion (TWI) in V2 to V6 and lead 1. A 1-mm ST elevation, TWI, and small Q waves are noted in leads II, III, and aVF (inferior leads).

The patient’s abnormal troponin T level assisted with the differential diagnosis. The patient’s normal CK-MB pattern, combined with an elevated troponin T with ECG changes and chest pain reported about one week earlier, supported the diagnosis of a recent acute MI (within the past week).

The stress test was canceled. Cardiac catheterization was performed and showed a 100% mid left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis, with left to left collaterals, and an 80% right coronary artery (RCA) stenosis. No left ventricular aneurysm was noted.

Interventions included an urgent percutaneous intervention (PCI) coronary stent placement to the LAD and a staged PCI to the RCA at a later date.

ANSWER

The ECG is diagnostic for a septal and anterolateral ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), suggestive of a recent MI versus left ventricular aneurysm. The ECG is also diagnostic for a recent inferior wall STEMI.

There are Q waves in leads V1 to V5 and a 2-mm ST elevation in V2 to V6, as well as a T-wave inversion (TWI) in V2 to V6 and lead 1. A 1-mm ST elevation, TWI, and small Q waves are noted in leads II, III, and aVF (inferior leads).

The patient’s abnormal troponin T level assisted with the differential diagnosis. The patient’s normal CK-MB pattern, combined with an elevated troponin T with ECG changes and chest pain reported about one week earlier, supported the diagnosis of a recent acute MI (within the past week).

The stress test was canceled. Cardiac catheterization was performed and showed a 100% mid left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis, with left to left collaterals, and an 80% right coronary artery (RCA) stenosis. No left ventricular aneurysm was noted.

Interventions included an urgent percutaneous intervention (PCI) coronary stent placement to the LAD and a staged PCI to the RCA at a later date.

A 53-year-old white man is referred for an adenosine myocardial perfusion scan stress test prior to left femoral popliteal bypass graft surgery. An ECG obtained one month ago was interpreted as normal. A transthoracic echocardiogram at that time revealed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (> 55%) with normal wall motion and no pathologic valvular heart disease. The patient is in distress due to left lower extremity vascular ischemic rest pain. He admits that earlier this morning, he was slightly dyspneic. However, he denies chest pain. He admits to not taking aspirin (162 mg Q day) as prescribed for the past two days. He also reports an 88–pack-year smoking history. Pulmonary function tests support mild obstructive emphysematous changes. The patient is 68” tall and weighs 128 lb (BMI, 19.5). His vital signs include: a blood pressure of 128/82 mm Hg; ventricular rate, 94 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 90% on room air. He is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include no jugular venous distention and no bilateral carotid, femoral, or abdominal bruits. The neurologic exam is unremarkable. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm with an S3 gallop; there is no S4, murmur, or click. There is no peripheral edema. Femoral pulses are +1. Pedal pulses are absent. Stat cardiac enzymes reveal a normal CK-MB (3.3 U/L) and an elevated troponin T level (0.117 μg/L; normal, 0.00 to 0.03). The complete blood count, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time/INR tests, and other chemistry panels all yield normal results. This patient’s ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 90 beats/min; PR interval, 135 ms; QRS duration, 96 ms; QT/QTc interval, 394/476 ms; P axis, 67°; R axis, 68°; and T axis, 172°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Edematous Changes Coincide with New Job

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gram-negative bacteria (choice “d”); Pseudomonas is the most likely culprit. Candida albicans (choice “a”), a yeast, is an unlikely cause of this problem and even more unlikely to show up on a bacterial culture. Coagulase-positive staph aureus (choice “b”) is typically associated with infections involving the acute onset of redness, pain, swelling, and pus formation, not the indolent, chronic, low-grade process seen in this case. Trichophyton rubrum (choice “c”) is a dermatophyte, the most common fungal cause of athlete’s feet. The bacterial culture could not have grown a dermatophyte, which needs special media and conditions to grow.

DISCUSSSION

Gram-negative interweb impetigo is a relatively common dermatologic entity, which can be caused by any number of organisms found in fecal material. Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Acinetobacter are among the more common culprits. These types of infections tend to be much more indolent than the more common staph- and strep-caused cellulitis, which are more likely to create acute redness, swelling, pain, and pus.

Both types of bacterial infections need certain conditions in order to develop. These include excessive heat, sweat, and perhaps most significantly, a break in the skin barrier. Ironically, these fissures are often caused by dermatophytes, in the form of tinea pedis, which is, of course, far better known for causing rashes of the foot.

But tinea pedis is more likely to be found between the third and fourth or the fourth and fifth toes. It creates itching and maceration but rarely causes diffuse redness or edema, and even more rarely leads to pain (unless there is a secondary bacterial infection). As mentioned, given the indolence of this infective process, a culture result showing staph or strep was unlikely.

The culture in this case showed Proteus, for which the minocycline was predictably effective. The rationale for obtaining the acid-fast culture was the possibility of finding Mycobacteria species such as M fortuitum, which is known to cause chronic indolent infections in feet and legs. These, however, more typically manifest with solitary eroded or ulcerated lesions. (Minocycline would have been effective against this organism.)

The use of the topical econazole served two purposes: While this was clearly not classic tinea pedis, it was still possible a dermatophyte or a yeast could have played a role in the creation of the initial fissuring; econazole will help control this, long term. Econazole also has significant antibacterial action and is particularly useful to help prevent future flares.

A 50-year-old man presents with a six-month history of worsening redness, swelling, and pain in the interdigital web spaces of both feet. Numerous treatments—most recently, a two-month course of terbinafine 250 mg/d—have not induced any change. The problem manifested as mild cracking between the first and second toes, dorsal aspect, and slowly spread laterally to involve all four web spaces. This pro-cess coincided with the start of a new job in which the patient is on his feet, wearing steel-toed boots, for 12 hours per day in a hot environment. Assuming the problem was athlete’s foot, he tried OTC clotrimazole and terbinafine creams; neither helped at all. In fact, the patient’s pain is now so bad that he has difficult walking. There is no history of smoking, diabetes, or other serious health problems. Examination shows distinct demarcated, dusky-red, edematous changes largely confined to the dorsal aspect. The actual deep interdigital space and the volar aspects of these areas are spared. Slight epidermal fissuring is seen on the dorsal aspect of each web space, from which a small amount of fluid can be coaxed. The fluid is sent for bacterial and acid-fast cultures. In the meantime, the patient is prescribed oral minocycline 100 bid and topical econazole cream and in-structed to return in two weeks. At that time, his condition is almost completely resolved.

Woman with “Dull, Achy” Back Pain and Shortness of Breath

ANSWER

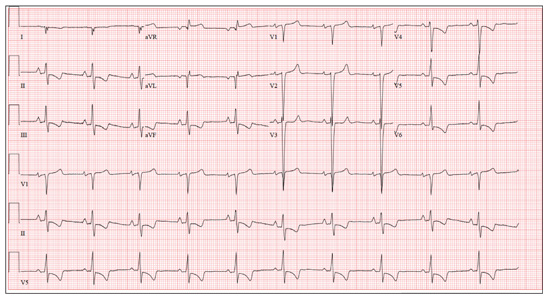

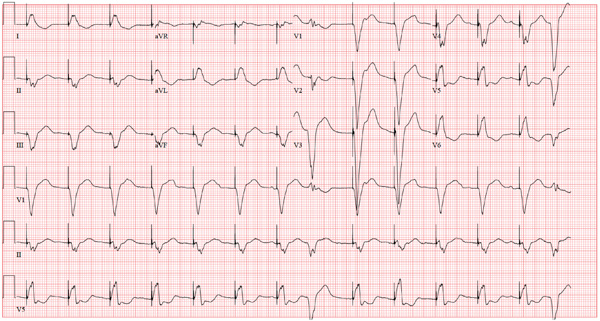

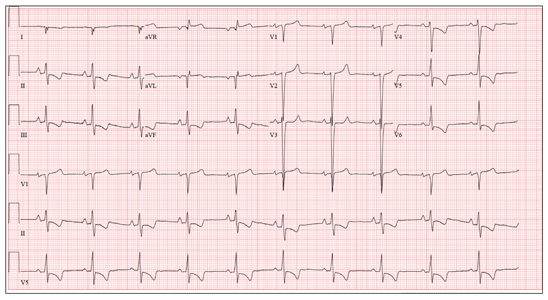

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm, right-axis deviation, evidence of a lateral MI, and inferolateral ST- and T-wave abnormalities.

Right-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis between 90° and 180° and QS or QR complexes in lead I and/or aVL. While the most common cause of a right-axis deviation is right ventricular hypertrophy, it is also evident in a lateral MI. Evidence for the latter includes the presence of significant Q waves in leads I and aVL. Finally, inferolateral ST- and T-wave changes are evidenced by inverted T waves in leads II, III, aVF, and precordial leads V4 to V6.

ECG evidence of a lateral MI not present on a previous scan (eight months ago), in the presence of a normal troponin level, suggests a recent MI.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm, right-axis deviation, evidence of a lateral MI, and inferolateral ST- and T-wave abnormalities.

Right-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis between 90° and 180° and QS or QR complexes in lead I and/or aVL. While the most common cause of a right-axis deviation is right ventricular hypertrophy, it is also evident in a lateral MI. Evidence for the latter includes the presence of significant Q waves in leads I and aVL. Finally, inferolateral ST- and T-wave changes are evidenced by inverted T waves in leads II, III, aVF, and precordial leads V4 to V6.

ECG evidence of a lateral MI not present on a previous scan (eight months ago), in the presence of a normal troponin level, suggests a recent MI.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm, right-axis deviation, evidence of a lateral MI, and inferolateral ST- and T-wave abnormalities.

Right-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis between 90° and 180° and QS or QR complexes in lead I and/or aVL. While the most common cause of a right-axis deviation is right ventricular hypertrophy, it is also evident in a lateral MI. Evidence for the latter includes the presence of significant Q waves in leads I and aVL. Finally, inferolateral ST- and T-wave changes are evidenced by inverted T waves in leads II, III, aVF, and precordial leads V4 to V6.

ECG evidence of a lateral MI not present on a previous scan (eight months ago), in the presence of a normal troponin level, suggests a recent MI.

A 70-year-old woman has a 10-year history of a dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy and New York Heart Association Class II heart failure. She presents with a one-week history of back pain and shortness of breath. She describes the pain as a “dull, achy” pressure, exacerbated by exertion and relieved with rest. She says the pain is localized in the back between her scapulas and does not radiate. She denies substernal chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or diaphoresis; the only associated symptom is dyspnea. Her most recent echocardiogram showed a dilated left ventricle, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 29%, and a normal right ventricle, with mild hypertrophy and mildly reduced systolic function. She was also noted to have atherosclerotic changes in her ascending and descending thoracic aorta. Medical history is remarkable for diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency, hyperlipidemia, and cataracts. Her current medications include aspirin, fer-rous sulfate, furosemide, hydralazine, glargine insulin, isosorbide dinitrate, lisinopril, metoprolol, and raloxifene. She is allergic to codeine, amiodarone, and radi-ographic contrast. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease, diabetes, and stroke. The patient is widowed, does not smoke, and does not consume alcohol. She is very active in her local quilting club. The review of systems is positive for increased weakness and diarrhea. She states that approximately two weeks ago, she experienced vague epigastric pain and diaphoresis; she did not seek medical attention, as it resolved. The physical exam reveals a thin, elderly woman in mild distress. Blood pressure is 139/82 mm Hg; pulse, 66 beats/min; respiratory rate, 21 breaths/¬min-1; and temperature, 35.9°C. Her weight is 108 lb. Pertinent physical findings include a grade II/VI diastolic murmur at the left lower sternal border, 2+ peripheral pulses with a bruit present in the right femoral artery, occasional late expiratory wheezes in both lung bases, vertebral tenderness at the T6-T7 level with no evidence of scoliosis or kyphosis, and no evidence of peripheral edema. She is intact from a neurologic standpoint. Significant laboratory data include a serum glucose level of 294 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 68 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.75 mg/dL; glomerular filtration rate, 30 mL/min; B-type natriuretic peptide, 984 pg/mL; and serum troponin, 0.11 ng/mL. An ECG is obtained that reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 62 beats/min; PR interval, 160 ms; QRS duration, 94 ms; QT/QTc interval, 404/410 ms; P ax-is, 84°; R axis, 151°; and T axis, 253°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Topical Steroids: the Solution or the Cause?

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). Prolonged injudicious use of topical steroids can cause a number of problems, including these; they are collectively termed iatrogenic since they are ultimately caused by prescribed medication. One of the more difficult aspects of this problem to deal with is the “addictive” state, in which withdrawal symptoms compel the patient to continue applying the offending steroid cream.

DISCUSSION

This is a relatively common scenario in dermatology offices. The misuse of topical steroids is well known, and something we strive to prevent—but with mixed results. It’s one of the reasons we’re stingy with refills of such medications, requiring the patient to be seen at least once a year. Unfortunately, this patient had been getting “refills” from friends in Mexico; patients often “borrow” steroid creams from household members or friends, or use products prescribed for one condition to treat others for which they were not intended.

The primary mode of action of topical steroids is vasoconstriction, a positive thing in terms of reduction of inflammation. The bad news is that continuous use of class 1 (the most powerful) steroids, such as clobetasol, can cause such profound and prolonged vasoconstriction that the skin effectively loses its blood supply and withers, sometimes down to adipose tissue. As one might suspect, this is more likely in already thin-skinned areas, including the antecubital area, face, neck, eyelids, and genitals, where the creation of striae is especially common.

Fairly early on in this process, before frank atrophy occurs, the condition being treated usually resolves. However, when the steroid is stopped, stinging and itching immediately return—which, of course, causes the patient to reapply the medication, perpetuating the vicious cycle.

The cycle is ultimately broken by gradual reduction in the frequency of application of successively weaker steroids. Usually, the skin gradually regenerates and returns to normal. In this case, the process will be lengthy and will almost certainly result in significant scarring.

Even injudicious application of weaker classes of steroids (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) to areas such as the face can result in a range of deleterious effects, including localized rosacea-like eruption or erythema. It has been reported that approximately 75% of cases of perioral dermatitis are either caused by or exacerbated by the application of topical steroids.

Topical application of even mid-strength steroids can also have systemic effects (eg, adrenal suppression, hyperglycemia) if applied over large areas. This is especially true when pediatric patients are involved.

Prevention of these iatrogenic effects lies in selecting the lowest strength steroid for the condition and area in question, then using them sparingly: no more than twice a day, and for no more than five days in a row, stopping for two consecutive days to allow the skin to regenerate. Even more caution should be exercised in treating children and when applying the product to intertriginous areas (skin-on-skin areas, such as the groin, in axillae, or under the breasts). Covering steroid-treated areas with anything—bandages, socks, even skin—effectively potentiates the positive and negative effects of steroids.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). Prolonged injudicious use of topical steroids can cause a number of problems, including these; they are collectively termed iatrogenic since they are ultimately caused by prescribed medication. One of the more difficult aspects of this problem to deal with is the “addictive” state, in which withdrawal symptoms compel the patient to continue applying the offending steroid cream.

DISCUSSION

This is a relatively common scenario in dermatology offices. The misuse of topical steroids is well known, and something we strive to prevent—but with mixed results. It’s one of the reasons we’re stingy with refills of such medications, requiring the patient to be seen at least once a year. Unfortunately, this patient had been getting “refills” from friends in Mexico; patients often “borrow” steroid creams from household members or friends, or use products prescribed for one condition to treat others for which they were not intended.

The primary mode of action of topical steroids is vasoconstriction, a positive thing in terms of reduction of inflammation. The bad news is that continuous use of class 1 (the most powerful) steroids, such as clobetasol, can cause such profound and prolonged vasoconstriction that the skin effectively loses its blood supply and withers, sometimes down to adipose tissue. As one might suspect, this is more likely in already thin-skinned areas, including the antecubital area, face, neck, eyelids, and genitals, where the creation of striae is especially common.

Fairly early on in this process, before frank atrophy occurs, the condition being treated usually resolves. However, when the steroid is stopped, stinging and itching immediately return—which, of course, causes the patient to reapply the medication, perpetuating the vicious cycle.

The cycle is ultimately broken by gradual reduction in the frequency of application of successively weaker steroids. Usually, the skin gradually regenerates and returns to normal. In this case, the process will be lengthy and will almost certainly result in significant scarring.

Even injudicious application of weaker classes of steroids (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) to areas such as the face can result in a range of deleterious effects, including localized rosacea-like eruption or erythema. It has been reported that approximately 75% of cases of perioral dermatitis are either caused by or exacerbated by the application of topical steroids.

Topical application of even mid-strength steroids can also have systemic effects (eg, adrenal suppression, hyperglycemia) if applied over large areas. This is especially true when pediatric patients are involved.

Prevention of these iatrogenic effects lies in selecting the lowest strength steroid for the condition and area in question, then using them sparingly: no more than twice a day, and for no more than five days in a row, stopping for two consecutive days to allow the skin to regenerate. Even more caution should be exercised in treating children and when applying the product to intertriginous areas (skin-on-skin areas, such as the groin, in axillae, or under the breasts). Covering steroid-treated areas with anything—bandages, socks, even skin—effectively potentiates the positive and negative effects of steroids.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). Prolonged injudicious use of topical steroids can cause a number of problems, including these; they are collectively termed iatrogenic since they are ultimately caused by prescribed medication. One of the more difficult aspects of this problem to deal with is the “addictive” state, in which withdrawal symptoms compel the patient to continue applying the offending steroid cream.

DISCUSSION

This is a relatively common scenario in dermatology offices. The misuse of topical steroids is well known, and something we strive to prevent—but with mixed results. It’s one of the reasons we’re stingy with refills of such medications, requiring the patient to be seen at least once a year. Unfortunately, this patient had been getting “refills” from friends in Mexico; patients often “borrow” steroid creams from household members or friends, or use products prescribed for one condition to treat others for which they were not intended.

The primary mode of action of topical steroids is vasoconstriction, a positive thing in terms of reduction of inflammation. The bad news is that continuous use of class 1 (the most powerful) steroids, such as clobetasol, can cause such profound and prolonged vasoconstriction that the skin effectively loses its blood supply and withers, sometimes down to adipose tissue. As one might suspect, this is more likely in already thin-skinned areas, including the antecubital area, face, neck, eyelids, and genitals, where the creation of striae is especially common.

Fairly early on in this process, before frank atrophy occurs, the condition being treated usually resolves. However, when the steroid is stopped, stinging and itching immediately return—which, of course, causes the patient to reapply the medication, perpetuating the vicious cycle.

The cycle is ultimately broken by gradual reduction in the frequency of application of successively weaker steroids. Usually, the skin gradually regenerates and returns to normal. In this case, the process will be lengthy and will almost certainly result in significant scarring.

Even injudicious application of weaker classes of steroids (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream) to areas such as the face can result in a range of deleterious effects, including localized rosacea-like eruption or erythema. It has been reported that approximately 75% of cases of perioral dermatitis are either caused by or exacerbated by the application of topical steroids.

Topical application of even mid-strength steroids can also have systemic effects (eg, adrenal suppression, hyperglycemia) if applied over large areas. This is especially true when pediatric patients are involved.

Prevention of these iatrogenic effects lies in selecting the lowest strength steroid for the condition and area in question, then using them sparingly: no more than twice a day, and for no more than five days in a row, stopping for two consecutive days to allow the skin to regenerate. Even more caution should be exercised in treating children and when applying the product to intertriginous areas (skin-on-skin areas, such as the groin, in axillae, or under the breasts). Covering steroid-treated areas with anything—bandages, socks, even skin—effectively potentiates the positive and negative effects of steroids.

A 59-year-old man presents with skin changes on both antecubital areas. For more than a year, he has applied clobetasol 0.05% cream at least twice daily to the area ostensibly for treatment of long-standing eczema, which has affected not only the antecubital areas but also the patient’s legs. In addition to the eczema, he has a history of atopy, marked by seasonal allergies and asthma. He notes that his stress level has increased in the past several months, which he suspects has contributed to his itching. On examination, marked epidermal atrophy is seen in both antecubital areas, along with extensive purpura. Surface adnexal structures, such as hair, follicles, and skin lines, are sparse at best, but dermal and subdermal vasculature are readily visible. In the midst of the affected area on the right arm, a nickel-sized, full-thickness defect is noted. Beneath it, adipose tissue can be seen. Clearly, these changes are attributable to the effects of the clobetasol, which the patient is advised to stop. But he replies that when he does, the treated areas burn and itch even more, until he obtains relief by applying more clobetasol.

Man with Consistent Headaches

ANSWER

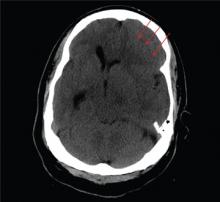

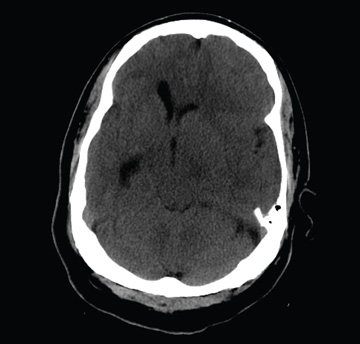

The image shows obvious mass effect throughout the left hemisphere. On close examination, there is evidence of an isodense subdural collection within the left frontoparietal region. This is causing a left-to-right shift of almost 11 mm.

This finding is most likely a subacute subdural hematoma, probably seven to 14 days old. Further questioning reveals that the patient had fallen in the shower approximately two weeks prior and hit his head. The patient was admitted for observation and subsequently underwent a craniotomy for evacuation of the subdural hematoma.

ANSWER

The image shows obvious mass effect throughout the left hemisphere. On close examination, there is evidence of an isodense subdural collection within the left frontoparietal region. This is causing a left-to-right shift of almost 11 mm.

This finding is most likely a subacute subdural hematoma, probably seven to 14 days old. Further questioning reveals that the patient had fallen in the shower approximately two weeks prior and hit his head. The patient was admitted for observation and subsequently underwent a craniotomy for evacuation of the subdural hematoma.

ANSWER

The image shows obvious mass effect throughout the left hemisphere. On close examination, there is evidence of an isodense subdural collection within the left frontoparietal region. This is causing a left-to-right shift of almost 11 mm.

This finding is most likely a subacute subdural hematoma, probably seven to 14 days old. Further questioning reveals that the patient had fallen in the shower approximately two weeks prior and hit his head. The patient was admitted for observation and subsequently underwent a craniotomy for evacuation of the subdural hematoma.

You are called to the emergency department (ED) in reference to a patient who was sent there by radiology with a reported “brain mass” noted on imaging. During further investigation in the ED, the patient, who is in his 50s, stated that he has had headaches for the past several weeks; he consulted his primary care provider, who ordered outpatient MRI of the brain—the test that ultimately led to his arrival in the ED. Since the MRI results were not immediately available for review, the ED staff obtained noncontrast CT of the head. The ED provider notes that it “looks like there is something there causing significant mass effect and shift.” When you arrive to see the patient, you note that he is awake, alert, and oriented times three. His Glasgow Coma Scale score is 15, and his vitals signs are normal. He states he has a mild headache, rating it a 3 out of 10 on a pain scale. His only other complaint is mild right-sided weakness, which he has noticed in the past week or so. Clinically, the strength in his right upper and lower extremities is good. His medical history is significant for prostate cancer and hypertension. A single cut from the CT of his head is shown. What is your impression?

Is This Golfer's Pacemaker Malfunctioning?

ANSWER

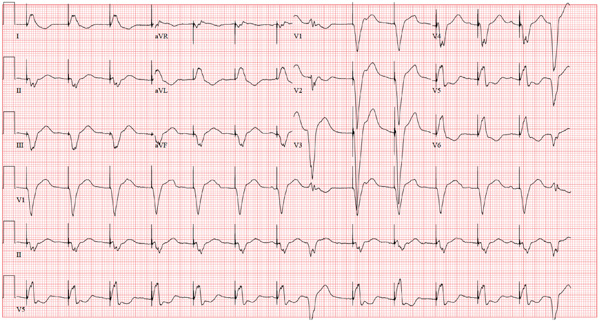

The ECG reveals an atrial-sensed and ventricular-paced rhythm of 83 beats/min. In this case, the pacemaker is functioning appropriately as programmed.

Pacemaker code consists of three letters: The first refers to the chamber(s) paced, the second to the chamber(s) sensed, and the third to the pacemaker’s response to a sensed beat. This patient has a pacing lead in the right atrium and one in the right ventricle and is programmed DDD. Each D in this case stands for dual: The first to indicate that both leads are programmed to pace, the second to indicate that both chambers may be sensed, and the third to indicate that the response to sensing can be either to inhibit or trigger a ventricular-paced beat in response to what happens in the atrium. Hence, there are four possible scenarios with a DDD pacemaker: AS-VS (atrial sensed-ventricle sensed; eg, intrinsic AV conduction requiring no pacing), AS-VP (atrial sensed-ventricle paced), AP-VS (atrial paced-ventricle sensed), and AP-VP (atrial paced-ventricle paced).

In this case, the atrial rate (83 beats/min) is faster than the pacemaker’s lower programmed rate. In order to see atrial pacing on the ECG, the intrinsic atrial rate would have to be less than the programmed rate of 60 beats/min. As soon as the pacemaker senses atrial conduction (either spontaneous or paced), it starts a timer (programmed at 130 ms in this case). If there is no spontaneous ventricular depolarization by the end of the timer, the pacemaker delivers an impulse to the ventricle, resulting in a paced ventricular beat. An often-made mistake (as this case illustrates) is the assumption that if one does not see pacing spikes, the pacemaker is not functioning properly.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals an atrial-sensed and ventricular-paced rhythm of 83 beats/min. In this case, the pacemaker is functioning appropriately as programmed.

Pacemaker code consists of three letters: The first refers to the chamber(s) paced, the second to the chamber(s) sensed, and the third to the pacemaker’s response to a sensed beat. This patient has a pacing lead in the right atrium and one in the right ventricle and is programmed DDD. Each D in this case stands for dual: The first to indicate that both leads are programmed to pace, the second to indicate that both chambers may be sensed, and the third to indicate that the response to sensing can be either to inhibit or trigger a ventricular-paced beat in response to what happens in the atrium. Hence, there are four possible scenarios with a DDD pacemaker: AS-VS (atrial sensed-ventricle sensed; eg, intrinsic AV conduction requiring no pacing), AS-VP (atrial sensed-ventricle paced), AP-VS (atrial paced-ventricle sensed), and AP-VP (atrial paced-ventricle paced).

In this case, the atrial rate (83 beats/min) is faster than the pacemaker’s lower programmed rate. In order to see atrial pacing on the ECG, the intrinsic atrial rate would have to be less than the programmed rate of 60 beats/min. As soon as the pacemaker senses atrial conduction (either spontaneous or paced), it starts a timer (programmed at 130 ms in this case). If there is no spontaneous ventricular depolarization by the end of the timer, the pacemaker delivers an impulse to the ventricle, resulting in a paced ventricular beat. An often-made mistake (as this case illustrates) is the assumption that if one does not see pacing spikes, the pacemaker is not functioning properly.

ANSWER

The ECG reveals an atrial-sensed and ventricular-paced rhythm of 83 beats/min. In this case, the pacemaker is functioning appropriately as programmed.

Pacemaker code consists of three letters: The first refers to the chamber(s) paced, the second to the chamber(s) sensed, and the third to the pacemaker’s response to a sensed beat. This patient has a pacing lead in the right atrium and one in the right ventricle and is programmed DDD. Each D in this case stands for dual: The first to indicate that both leads are programmed to pace, the second to indicate that both chambers may be sensed, and the third to indicate that the response to sensing can be either to inhibit or trigger a ventricular-paced beat in response to what happens in the atrium. Hence, there are four possible scenarios with a DDD pacemaker: AS-VS (atrial sensed-ventricle sensed; eg, intrinsic AV conduction requiring no pacing), AS-VP (atrial sensed-ventricle paced), AP-VS (atrial paced-ventricle sensed), and AP-VP (atrial paced-ventricle paced).

In this case, the atrial rate (83 beats/min) is faster than the pacemaker’s lower programmed rate. In order to see atrial pacing on the ECG, the intrinsic atrial rate would have to be less than the programmed rate of 60 beats/min. As soon as the pacemaker senses atrial conduction (either spontaneous or paced), it starts a timer (programmed at 130 ms in this case). If there is no spontaneous ventricular depolarization by the end of the timer, the pacemaker delivers an impulse to the ventricle, resulting in a paced ventricular beat. An often-made mistake (as this case illustrates) is the assumption that if one does not see pacing spikes, the pacemaker is not functioning properly.

A 75-year-old man has a history of New York Heart Association Class II congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD) with coronary artery by-pass graft (CABG) surgery, and aortic stenosis with a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement (AVR). He developed second-degree heart block (Mobitz II) following his four-vessel CABG and AVR four years ago, requiring placement of a dual-chamber pacemaker. He has been asymptomatic and plays golf two to three times per week. One week ago, he went to an urgent care center for treatment of a laceration on his leg and was told that part of his pacemaker wasn’t working. He presents to you now for follow-up on the pacemaker. Medical history is also remarkable for COPD, left inguinal hernia repair, hyperlipidemia, and bilateral cataracts. Family history is positive for CAD, diabetes, and stroke. He has a remote history of smoking and drinks one martini after each golf game. His medications include aspirin, lovastatin, and metoprolol. He has no drug allergies. The review of systems is negative except for a recent repair to a 3-cm laceration on the left leg. Physical examination reveals a well-developed, pleasant man in no distress. His height is 74” and weight, 179 lb. Blood pressure is 118/84 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; temperature, 98.8°F; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include a well-healed pacemaker site without signs of recent trauma. The lungs are clear in all fields, the cardiac exam is within normal limits, and there is no jugular venous distention. The abdomen is benign, and there is no peripheral edema. The laceration repair on his left leg is healing well (no erythema, induration, wound separation, or dehiscence). The pacemaker is programmed DDD at a lower rate of 60 beats/min and an upper rate of 120 beats/min, with paced and sensed atrioventricular (AV) delays programmed at 130 ms. An ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 83 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 162 ms; QT/QTc interval, 480/564 ms; P axis, unmeasurable; R axis, 254°; and T axis, 56°. What is your interpretation of this ECG? Is there any indication that the pacemaker is not functioning?

Is Leprosy the Cause of This Girl's Lesion?

ANSWER

The correct answer is postinflammatory hypopigmentation (choice “c”), in this case secondary to eczema in a classic antecubital location. Leprosy (choice “a”) is more common than one might imagine, but it does not appear overnight and does not involve overt inflammation. Vitiligo (choice “b”) does not appear suddenly and rarely involves the type of inflammation seen in this case. Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (choice “d”) is an inflammatory condition that presents with hypopigmentation and epidermal atrophy; however, it is gradual in onset and would not exhibit papulosquamous inflammation.

DISCUSSION

The more color in the skin, the more the loss of that color stands out. Patients and families with darker skin are often understandably upset by the contrast. Providers need a differential for pigment loss, including the items mentioned—some of which have the potential to be dreadfully serious.

Two relevant facts stand out in this case: the rapidity of onset and the history of eczema, in which secondary pigment loss can occur. As mentioned, it is especially obvious in those with darker skin. Fortunately, once the eczema calms down, the hypopigmentation resolves and normal color returns.

Paradoxically, it’s not at all unusual to see postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in those with skin of types IV and V (eg, African-Americans, some Hispanics, and those of Indian ancestry). Eczema is a common cause, but the inflammation can be from almost any source, including trauma, burns, or even acne.

Had this patient’s diagnosis not been obvious, a biopsy might have been indicated due to the serious nature of some of the items in the differential. Vitiligo, for example, can be very disfiguring, especially on a dark-skinned individual. It tends to become widespread and permanent, unless it’s caught and treated early on. Other conditions involving hypopigmentation include sarcoidosis, lupus, and morphea.

All of these conditions are unusual, if not rare, compared with atopic dermatitis (AD), which this patient has. AD is so common that almost 20% of newborns develop it. Eczema is one of the more typical manifestations, along with dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and reactive airway disease. Corroboration of the diagnosis is usually easily accomplished by taking a family history.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, this patient’s hypopigmentation will resolve quickly with treatment of her eczema, using a low-strength steroid cream (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment). But a good portion of the “treatment” of AD is done by educating the family about the nature of the condition, as well as providing reassurance about the absence of the more serious items in the differential.

ANSWER

The correct answer is postinflammatory hypopigmentation (choice “c”), in this case secondary to eczema in a classic antecubital location. Leprosy (choice “a”) is more common than one might imagine, but it does not appear overnight and does not involve overt inflammation. Vitiligo (choice “b”) does not appear suddenly and rarely involves the type of inflammation seen in this case. Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (choice “d”) is an inflammatory condition that presents with hypopigmentation and epidermal atrophy; however, it is gradual in onset and would not exhibit papulosquamous inflammation.

DISCUSSION

The more color in the skin, the more the loss of that color stands out. Patients and families with darker skin are often understandably upset by the contrast. Providers need a differential for pigment loss, including the items mentioned—some of which have the potential to be dreadfully serious.

Two relevant facts stand out in this case: the rapidity of onset and the history of eczema, in which secondary pigment loss can occur. As mentioned, it is especially obvious in those with darker skin. Fortunately, once the eczema calms down, the hypopigmentation resolves and normal color returns.

Paradoxically, it’s not at all unusual to see postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in those with skin of types IV and V (eg, African-Americans, some Hispanics, and those of Indian ancestry). Eczema is a common cause, but the inflammation can be from almost any source, including trauma, burns, or even acne.

Had this patient’s diagnosis not been obvious, a biopsy might have been indicated due to the serious nature of some of the items in the differential. Vitiligo, for example, can be very disfiguring, especially on a dark-skinned individual. It tends to become widespread and permanent, unless it’s caught and treated early on. Other conditions involving hypopigmentation include sarcoidosis, lupus, and morphea.

All of these conditions are unusual, if not rare, compared with atopic dermatitis (AD), which this patient has. AD is so common that almost 20% of newborns develop it. Eczema is one of the more typical manifestations, along with dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and reactive airway disease. Corroboration of the diagnosis is usually easily accomplished by taking a family history.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, this patient’s hypopigmentation will resolve quickly with treatment of her eczema, using a low-strength steroid cream (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment). But a good portion of the “treatment” of AD is done by educating the family about the nature of the condition, as well as providing reassurance about the absence of the more serious items in the differential.

ANSWER

The correct answer is postinflammatory hypopigmentation (choice “c”), in this case secondary to eczema in a classic antecubital location. Leprosy (choice “a”) is more common than one might imagine, but it does not appear overnight and does not involve overt inflammation. Vitiligo (choice “b”) does not appear suddenly and rarely involves the type of inflammation seen in this case. Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (choice “d”) is an inflammatory condition that presents with hypopigmentation and epidermal atrophy; however, it is gradual in onset and would not exhibit papulosquamous inflammation.

DISCUSSION

The more color in the skin, the more the loss of that color stands out. Patients and families with darker skin are often understandably upset by the contrast. Providers need a differential for pigment loss, including the items mentioned—some of which have the potential to be dreadfully serious.

Two relevant facts stand out in this case: the rapidity of onset and the history of eczema, in which secondary pigment loss can occur. As mentioned, it is especially obvious in those with darker skin. Fortunately, once the eczema calms down, the hypopigmentation resolves and normal color returns.

Paradoxically, it’s not at all unusual to see postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in those with skin of types IV and V (eg, African-Americans, some Hispanics, and those of Indian ancestry). Eczema is a common cause, but the inflammation can be from almost any source, including trauma, burns, or even acne.

Had this patient’s diagnosis not been obvious, a biopsy might have been indicated due to the serious nature of some of the items in the differential. Vitiligo, for example, can be very disfiguring, especially on a dark-skinned individual. It tends to become widespread and permanent, unless it’s caught and treated early on. Other conditions involving hypopigmentation include sarcoidosis, lupus, and morphea.

All of these conditions are unusual, if not rare, compared with atopic dermatitis (AD), which this patient has. AD is so common that almost 20% of newborns develop it. Eczema is one of the more typical manifestations, along with dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and reactive airway disease. Corroboration of the diagnosis is usually easily accomplished by taking a family history.

TREATMENT

Fortunately, this patient’s hypopigmentation will resolve quickly with treatment of her eczema, using a low-strength steroid cream (eg, hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or ointment). But a good portion of the “treatment” of AD is done by educating the family about the nature of the condition, as well as providing reassurance about the absence of the more serious items in the differential.

The parents of this 8-month-old infant are alarmed by skin changes that occurred practically overnight on the child’s arm—especially since the child’s grandparents suggested it might represent vitiligo or even leprosy. The child’s pediatrician thought “ringworm” was more likely, but the clotrimazole cream he recommended was no help. The child has an extensive history of atopy, including eczema affecting the trunk and face. The parents have used topical steroid cream on the affected areas with some good effect, but the loss of color in the antecubital site has made them reluctant to use the product on this new site. Examination shows a papulosquamous lesion, 3.5 cm in diameter, on the left lateral antecubital area, with marked central hypopigmentation. The child and her parents are Vietnamese, with type IV skin, making the pigment loss all the more obvious. The periphery of the lesion, in addition to being bumpy and scaly, is moderately inflamed. The rest of the child’s skin is dry but otherwise unremarkable.