User login

Conservative Approach to Treatment of Cyclosporine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia With Azithromycin and Chlorhexidine

Conservative Approach to Treatment of Cyclosporine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia With Azithromycin and Chlorhexidine

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor and immunosuppressive medication with several indications, including prevention of parenchymal organ and bone marrow transplant rejection as well as treatment of numerous dermatologic conditions (eg, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis). Although it is an effective medication, there are many known adverse effects including nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and gingival hyperplasia.1 Addressing symptomatic cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be challenging, especially if continued use of cyclosporine is necessary for adequate control of the underlying disease. We present a simplified approach for conservative management of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia that allows for continued use of cyclosporine.

Practice Gap

Cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia is a fibrous overgrowth of the interdental papilla and labial gingiva that may lead to gum pain, difficulty eating, gingivitis, and/ or tooth decay or loss.2 The condition usually occurs 3 to 6 months after starting cyclosporine but may occur as soon as 1 month later.1,3 The pathophysiology of this adverse effect is incompletely understood, but several mechanisms have been implicated, including upregulation of the salivary proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6.1 Additionally, patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia have increased bacterial colonization with species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis.4 Risk factors for cyclosporine- induced gingival hyperplasia include higher serum concentrations (>400 ng/mL) of cyclosporine, history of gingival hyperplasia, concomitant use of calcium channel blockers, and insufficient oral hygiene.2,3 A study by Seymour and Smith5 found that proper oral hygiene leads to less severe cases of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia but does not prevent gingival overgrowth. Treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia traditionally involves targeting oral bacteria and reducing inflammation. Decreasing dental plaque through regular tooth-brushing and interdental cleaning may reduce symptoms such as bleeding and discomfort of the gums.

The intensity of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be reduced with chlorhexidine or azithromycin. Individually, each therapy has been shown to clinically improve cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia; however, to our knowledge the combination of these treatments has not been reported.1 We present a simplified approach to treating cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia using both azithromycin and chlorhexidine. This conservative approach results in effective and sustained improvement of gingival hyperplasia while allowing patients to continue cyclosporine therapy to control underlying disease with minimal adverse effects.

Technique

Before initiating treatment, it is important to confirm that the etiology of gingival hyperplasia is due to cyclosporine use and rule out nutritional deficiencies and autoimmune conditions as potential causes. Be sure to inquire about nutritional intake, systemic symptoms, and family history of autoimmune conditions. Our approach includes the use of azithromycin 500 mg once daily for 7 days followed by chlorhexidine 0.12% oral solution 15 mL twice daily (swish undiluted for 30 seconds, then spit) for at least 3 months for optimal management of gingival hyperplasia. Chlorhexidine should be continued for at least 6 months to maintain symptom resolution. While cyclosporine therapy may be continued throughout the duration of this regimen, consider switching to other immunosuppressive medications that are not associated with gingival hyperplasia (eg, tacrolimus) if symptoms are severe and/or resistant to therapy.1,6

We applied this technique to treat cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in a 28-year-old woman with a 3-year history of primary aplastic anemia. The patient initially presented with pain and bleeding of the gums of several months’ duration and reported experiencing gum pain when eating solid foods. Her medications included cyclosporine 225 mg daily for aplastic anemia and dapsone 100 mg daily for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, both of which were taken for the past 6 months. Oral examination revealed pink to bright red hyperplastic gingivae (Figure). She had no other symptoms associated with aplastic anemia and no signs of vitamin or nutritional deficiencies. She denied pre-existing periodontitis prior to starting cyclosporine and reported that the symptoms started several months after initiating cyclosporine therapy. Thus, the clinical diagnosis of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia was made, and treatment with azithromycin and chlorhexidine was initiated with marked reduction in symptoms.

Conservative management of gingival hyperplasia with oral hygiene including regular tooth-brushing and flossing and antimicrobial therapies was preferred in this patient to reduce gum pain and minimize the risk for tooth loss while also limiting the use of surgically invasive interventions. Due to limited therapeutic options for aplastic anemia, continued administration of cyclosporine was necessary in our patient to prevent further complications.

Practice Implications

The precise mechanism by which azithromycin treats gingival hyperplasia is unclear but may involve its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Small concentrations of azithromycin have been shown to persist in macrophages and fibroblasts of the gingiva even with short-term administration of 3 to 5 days.7 Chlorhexidine is another antimicrobial agent often used in oral rinse solutions to decrease plaque formation and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine can reduce cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth when used twice daily.8 After rinsing with chlorhexidine, saliva exhibits antibacterial activity for up to 5 hours; however, tooth and gum discoloration may occur.8

Recurrence of gingival hyperplasia is likely if cyclosporine is not discontinued or maintained with treatment.3 Conventional gingivectomy should be considered for cases in which conservative treatment is ineffective, aesthetic concerns arise, or gingival hyperplasia persists for more than 6 to 12 months after discontinuing cyclosporine.1

We theorize that the microbial properties of azithromycin and chlorhexidine help reduce periodontal inflammation and bacterial overgrowth in patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia, which allows for restoration of gingival health. Our case highlights the efficacy of our treatment approach using a 7-day course of azithromycin followed by twice-daily use of chlorhexidine oral rinse in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia with continued use of cyclosporine.

- Chojnacka-Purpurowicz J, Wygonowska E, Placek W, et al. Cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth—review. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15912.

- Greenburg KV, Armitage GC, Shiboski CH. Gingival enlargement among renal transplant recipients in the era of new-generation immunosuppressants. J Periodontol. 2008;79:453-460.

- Cyclosporine (ciclosporin)(systemic): drug information. UpToDate. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/table-of-contents/drug-information/general-drug-information

- Gong Y, Bi W, Cao L, et al. Association of CD14-260 polymorphisms, red-complex periodontopathogens and gingival crevicular fluid cytokine levels with cyclosporine A-induced gingival overgrowth in renal transplant patients. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:203-212.

- Seymour RA, Smith DG. The effect of a plaque control programme on the incidence and severity of cyclosporin-induced gingival changes. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:107-110.

- Nash MM, Zaltzman JS. Efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1998;65:1611-1615.

- Martín JM, Mateo E, Jordá E. Utilidad de la azitromicina en la hyperplasia gingival inducida por ciclosporina [azithromycin for the treatment of ciclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:780.

- Gau CH, Tu HS, Chin YT, et al. Can chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily ameliorate cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth? J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:131-137.

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor and immunosuppressive medication with several indications, including prevention of parenchymal organ and bone marrow transplant rejection as well as treatment of numerous dermatologic conditions (eg, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis). Although it is an effective medication, there are many known adverse effects including nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and gingival hyperplasia.1 Addressing symptomatic cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be challenging, especially if continued use of cyclosporine is necessary for adequate control of the underlying disease. We present a simplified approach for conservative management of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia that allows for continued use of cyclosporine.

Practice Gap

Cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia is a fibrous overgrowth of the interdental papilla and labial gingiva that may lead to gum pain, difficulty eating, gingivitis, and/ or tooth decay or loss.2 The condition usually occurs 3 to 6 months after starting cyclosporine but may occur as soon as 1 month later.1,3 The pathophysiology of this adverse effect is incompletely understood, but several mechanisms have been implicated, including upregulation of the salivary proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6.1 Additionally, patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia have increased bacterial colonization with species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis.4 Risk factors for cyclosporine- induced gingival hyperplasia include higher serum concentrations (>400 ng/mL) of cyclosporine, history of gingival hyperplasia, concomitant use of calcium channel blockers, and insufficient oral hygiene.2,3 A study by Seymour and Smith5 found that proper oral hygiene leads to less severe cases of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia but does not prevent gingival overgrowth. Treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia traditionally involves targeting oral bacteria and reducing inflammation. Decreasing dental plaque through regular tooth-brushing and interdental cleaning may reduce symptoms such as bleeding and discomfort of the gums.

The intensity of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be reduced with chlorhexidine or azithromycin. Individually, each therapy has been shown to clinically improve cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia; however, to our knowledge the combination of these treatments has not been reported.1 We present a simplified approach to treating cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia using both azithromycin and chlorhexidine. This conservative approach results in effective and sustained improvement of gingival hyperplasia while allowing patients to continue cyclosporine therapy to control underlying disease with minimal adverse effects.

Technique

Before initiating treatment, it is important to confirm that the etiology of gingival hyperplasia is due to cyclosporine use and rule out nutritional deficiencies and autoimmune conditions as potential causes. Be sure to inquire about nutritional intake, systemic symptoms, and family history of autoimmune conditions. Our approach includes the use of azithromycin 500 mg once daily for 7 days followed by chlorhexidine 0.12% oral solution 15 mL twice daily (swish undiluted for 30 seconds, then spit) for at least 3 months for optimal management of gingival hyperplasia. Chlorhexidine should be continued for at least 6 months to maintain symptom resolution. While cyclosporine therapy may be continued throughout the duration of this regimen, consider switching to other immunosuppressive medications that are not associated with gingival hyperplasia (eg, tacrolimus) if symptoms are severe and/or resistant to therapy.1,6

We applied this technique to treat cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in a 28-year-old woman with a 3-year history of primary aplastic anemia. The patient initially presented with pain and bleeding of the gums of several months’ duration and reported experiencing gum pain when eating solid foods. Her medications included cyclosporine 225 mg daily for aplastic anemia and dapsone 100 mg daily for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, both of which were taken for the past 6 months. Oral examination revealed pink to bright red hyperplastic gingivae (Figure). She had no other symptoms associated with aplastic anemia and no signs of vitamin or nutritional deficiencies. She denied pre-existing periodontitis prior to starting cyclosporine and reported that the symptoms started several months after initiating cyclosporine therapy. Thus, the clinical diagnosis of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia was made, and treatment with azithromycin and chlorhexidine was initiated with marked reduction in symptoms.

Conservative management of gingival hyperplasia with oral hygiene including regular tooth-brushing and flossing and antimicrobial therapies was preferred in this patient to reduce gum pain and minimize the risk for tooth loss while also limiting the use of surgically invasive interventions. Due to limited therapeutic options for aplastic anemia, continued administration of cyclosporine was necessary in our patient to prevent further complications.

Practice Implications

The precise mechanism by which azithromycin treats gingival hyperplasia is unclear but may involve its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Small concentrations of azithromycin have been shown to persist in macrophages and fibroblasts of the gingiva even with short-term administration of 3 to 5 days.7 Chlorhexidine is another antimicrobial agent often used in oral rinse solutions to decrease plaque formation and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine can reduce cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth when used twice daily.8 After rinsing with chlorhexidine, saliva exhibits antibacterial activity for up to 5 hours; however, tooth and gum discoloration may occur.8

Recurrence of gingival hyperplasia is likely if cyclosporine is not discontinued or maintained with treatment.3 Conventional gingivectomy should be considered for cases in which conservative treatment is ineffective, aesthetic concerns arise, or gingival hyperplasia persists for more than 6 to 12 months after discontinuing cyclosporine.1

We theorize that the microbial properties of azithromycin and chlorhexidine help reduce periodontal inflammation and bacterial overgrowth in patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia, which allows for restoration of gingival health. Our case highlights the efficacy of our treatment approach using a 7-day course of azithromycin followed by twice-daily use of chlorhexidine oral rinse in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia with continued use of cyclosporine.

Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor and immunosuppressive medication with several indications, including prevention of parenchymal organ and bone marrow transplant rejection as well as treatment of numerous dermatologic conditions (eg, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis). Although it is an effective medication, there are many known adverse effects including nephrotoxicity, hypertension, and gingival hyperplasia.1 Addressing symptomatic cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be challenging, especially if continued use of cyclosporine is necessary for adequate control of the underlying disease. We present a simplified approach for conservative management of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia that allows for continued use of cyclosporine.

Practice Gap

Cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia is a fibrous overgrowth of the interdental papilla and labial gingiva that may lead to gum pain, difficulty eating, gingivitis, and/ or tooth decay or loss.2 The condition usually occurs 3 to 6 months after starting cyclosporine but may occur as soon as 1 month later.1,3 The pathophysiology of this adverse effect is incompletely understood, but several mechanisms have been implicated, including upregulation of the salivary proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-8, and IL-6.1 Additionally, patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia have increased bacterial colonization with species such as Porphyromonas gingivalis.4 Risk factors for cyclosporine- induced gingival hyperplasia include higher serum concentrations (>400 ng/mL) of cyclosporine, history of gingival hyperplasia, concomitant use of calcium channel blockers, and insufficient oral hygiene.2,3 A study by Seymour and Smith5 found that proper oral hygiene leads to less severe cases of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia but does not prevent gingival overgrowth. Treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia traditionally involves targeting oral bacteria and reducing inflammation. Decreasing dental plaque through regular tooth-brushing and interdental cleaning may reduce symptoms such as bleeding and discomfort of the gums.

The intensity of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia can be reduced with chlorhexidine or azithromycin. Individually, each therapy has been shown to clinically improve cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia; however, to our knowledge the combination of these treatments has not been reported.1 We present a simplified approach to treating cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia using both azithromycin and chlorhexidine. This conservative approach results in effective and sustained improvement of gingival hyperplasia while allowing patients to continue cyclosporine therapy to control underlying disease with minimal adverse effects.

Technique

Before initiating treatment, it is important to confirm that the etiology of gingival hyperplasia is due to cyclosporine use and rule out nutritional deficiencies and autoimmune conditions as potential causes. Be sure to inquire about nutritional intake, systemic symptoms, and family history of autoimmune conditions. Our approach includes the use of azithromycin 500 mg once daily for 7 days followed by chlorhexidine 0.12% oral solution 15 mL twice daily (swish undiluted for 30 seconds, then spit) for at least 3 months for optimal management of gingival hyperplasia. Chlorhexidine should be continued for at least 6 months to maintain symptom resolution. While cyclosporine therapy may be continued throughout the duration of this regimen, consider switching to other immunosuppressive medications that are not associated with gingival hyperplasia (eg, tacrolimus) if symptoms are severe and/or resistant to therapy.1,6

We applied this technique to treat cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in a 28-year-old woman with a 3-year history of primary aplastic anemia. The patient initially presented with pain and bleeding of the gums of several months’ duration and reported experiencing gum pain when eating solid foods. Her medications included cyclosporine 225 mg daily for aplastic anemia and dapsone 100 mg daily for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, both of which were taken for the past 6 months. Oral examination revealed pink to bright red hyperplastic gingivae (Figure). She had no other symptoms associated with aplastic anemia and no signs of vitamin or nutritional deficiencies. She denied pre-existing periodontitis prior to starting cyclosporine and reported that the symptoms started several months after initiating cyclosporine therapy. Thus, the clinical diagnosis of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia was made, and treatment with azithromycin and chlorhexidine was initiated with marked reduction in symptoms.

Conservative management of gingival hyperplasia with oral hygiene including regular tooth-brushing and flossing and antimicrobial therapies was preferred in this patient to reduce gum pain and minimize the risk for tooth loss while also limiting the use of surgically invasive interventions. Due to limited therapeutic options for aplastic anemia, continued administration of cyclosporine was necessary in our patient to prevent further complications.

Practice Implications

The precise mechanism by which azithromycin treats gingival hyperplasia is unclear but may involve its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Small concentrations of azithromycin have been shown to persist in macrophages and fibroblasts of the gingiva even with short-term administration of 3 to 5 days.7 Chlorhexidine is another antimicrobial agent often used in oral rinse solutions to decrease plaque formation and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine can reduce cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth when used twice daily.8 After rinsing with chlorhexidine, saliva exhibits antibacterial activity for up to 5 hours; however, tooth and gum discoloration may occur.8

Recurrence of gingival hyperplasia is likely if cyclosporine is not discontinued or maintained with treatment.3 Conventional gingivectomy should be considered for cases in which conservative treatment is ineffective, aesthetic concerns arise, or gingival hyperplasia persists for more than 6 to 12 months after discontinuing cyclosporine.1

We theorize that the microbial properties of azithromycin and chlorhexidine help reduce periodontal inflammation and bacterial overgrowth in patients with cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia, which allows for restoration of gingival health. Our case highlights the efficacy of our treatment approach using a 7-day course of azithromycin followed by twice-daily use of chlorhexidine oral rinse in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia with continued use of cyclosporine.

- Chojnacka-Purpurowicz J, Wygonowska E, Placek W, et al. Cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth—review. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15912.

- Greenburg KV, Armitage GC, Shiboski CH. Gingival enlargement among renal transplant recipients in the era of new-generation immunosuppressants. J Periodontol. 2008;79:453-460.

- Cyclosporine (ciclosporin)(systemic): drug information. UpToDate. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/table-of-contents/drug-information/general-drug-information

- Gong Y, Bi W, Cao L, et al. Association of CD14-260 polymorphisms, red-complex periodontopathogens and gingival crevicular fluid cytokine levels with cyclosporine A-induced gingival overgrowth in renal transplant patients. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:203-212.

- Seymour RA, Smith DG. The effect of a plaque control programme on the incidence and severity of cyclosporin-induced gingival changes. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:107-110.

- Nash MM, Zaltzman JS. Efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1998;65:1611-1615.

- Martín JM, Mateo E, Jordá E. Utilidad de la azitromicina en la hyperplasia gingival inducida por ciclosporina [azithromycin for the treatment of ciclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:780.

- Gau CH, Tu HS, Chin YT, et al. Can chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily ameliorate cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth? J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:131-137.

- Chojnacka-Purpurowicz J, Wygonowska E, Placek W, et al. Cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth—review. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15912.

- Greenburg KV, Armitage GC, Shiboski CH. Gingival enlargement among renal transplant recipients in the era of new-generation immunosuppressants. J Periodontol. 2008;79:453-460.

- Cyclosporine (ciclosporin)(systemic): drug information. UpToDate. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/table-of-contents/drug-information/general-drug-information

- Gong Y, Bi W, Cao L, et al. Association of CD14-260 polymorphisms, red-complex periodontopathogens and gingival crevicular fluid cytokine levels with cyclosporine A-induced gingival overgrowth in renal transplant patients. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:203-212.

- Seymour RA, Smith DG. The effect of a plaque control programme on the incidence and severity of cyclosporin-induced gingival changes. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:107-110.

- Nash MM, Zaltzman JS. Efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1998;65:1611-1615.

- Martín JM, Mateo E, Jordá E. Utilidad de la azitromicina en la hyperplasia gingival inducida por ciclosporina [azithromycin for the treatment of ciclosporin-induced gingival hyperplasia]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:780.

- Gau CH, Tu HS, Chin YT, et al. Can chlorhexidine mouthwash twice daily ameliorate cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth? J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:131-137.

Conservative Approach to Treatment of Cyclosporine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia With Azithromycin and Chlorhexidine

Conservative Approach to Treatment of Cyclosporine-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia With Azithromycin and Chlorhexidine

Need a Wood Lamp Alternative? Grab Your Smartphone

Practice Gap

The Wood lamp commonly is used as a diagnostic tool for pigmentary skin conditions (eg, vitiligo) or skin conditions that exhibit fluorescence (eg, erythrasma).1 Recently, its diagnostic efficacy has extended to scabies, in which it unveils a distinctive wavy, bluish-white, linear fluorescence upon illumination.2

Functionally, the Wood lamp operates by subjecting phosphors to UV light within the wavelength range of 320 to 400 nm, inducing fluorescence in substances such as collagen and elastin. In the context of vitiligo, this process manifests as a preferential chalk white fluorescence in areas lacking melanin.1

Despite its demonstrated effectiveness, the Wood lamp is not without limitations. It comes with a notable financial investment ranging from $70 to $500, requires periodic maintenance such as light bulb replacements, and can be unwieldy.3 Furthermore, its reliance on a power source poses a challenge in settings where immediate access to convenient power outlets is limited, such as inpatient and rural dermatology clinics. These limitations underscore the need for alternative solutions and innovations to address challenges and ensure accessibility in diverse health care environments.

The Tools

Free smartphone applications (apps), such as Ultraviolet Light-UV Lamp by AppBrain or Blacklight UV Light Simulator by That Smile, can simulate UV light and functionally serve as a Wood lamp.

The Technique

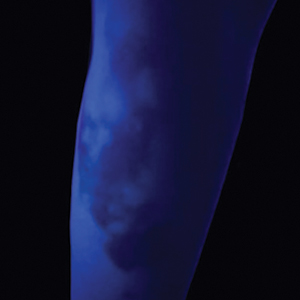

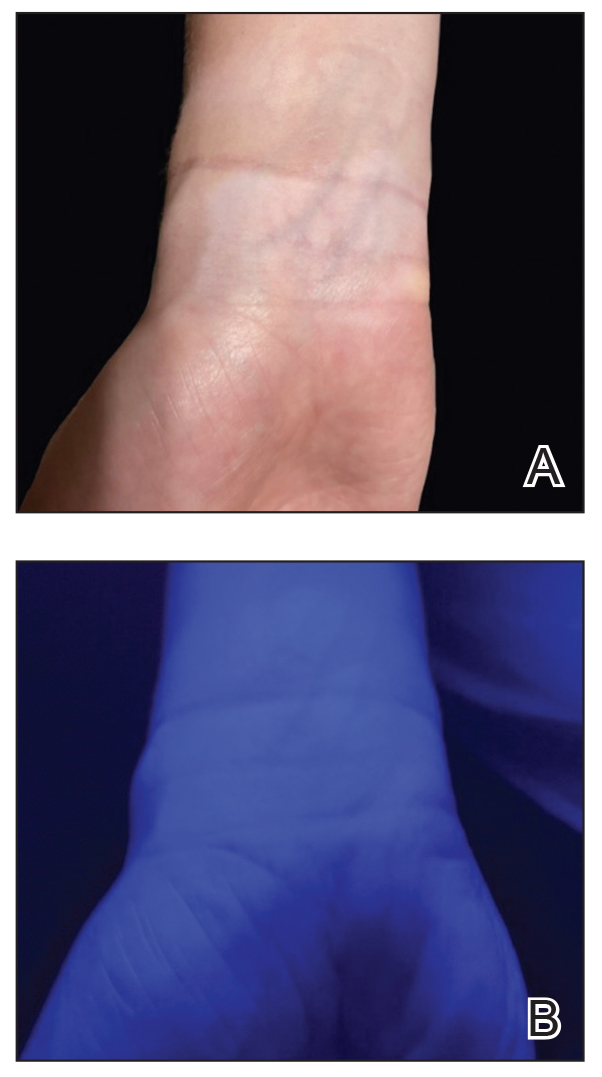

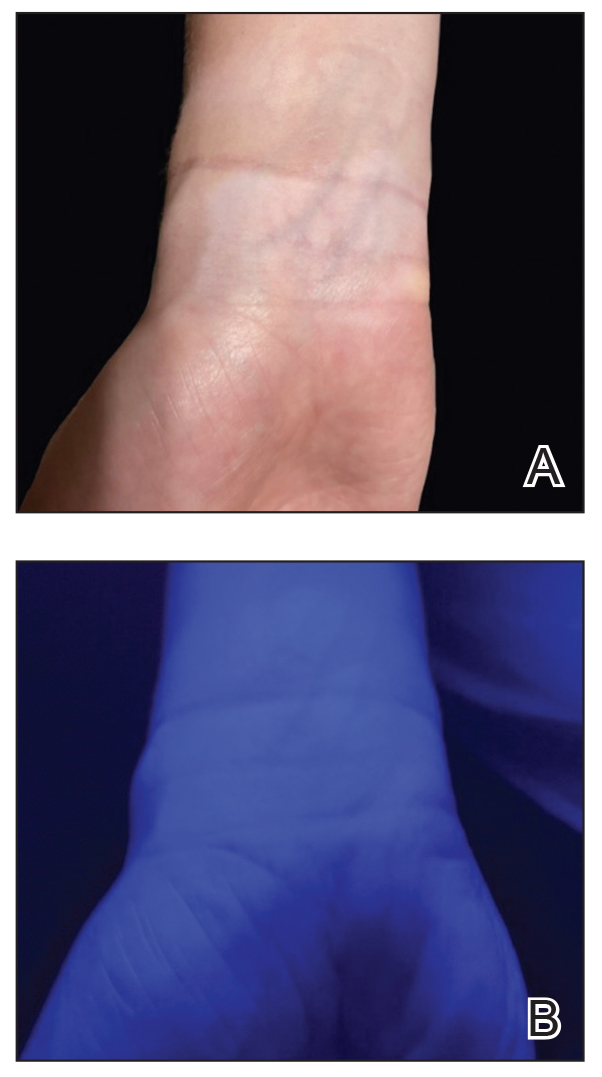

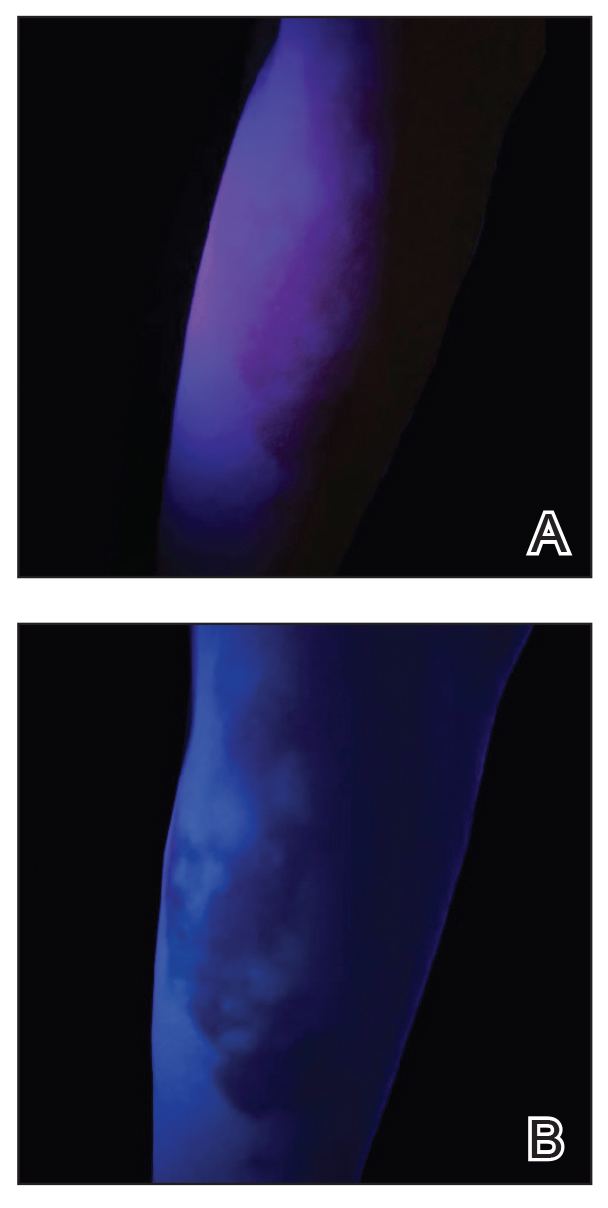

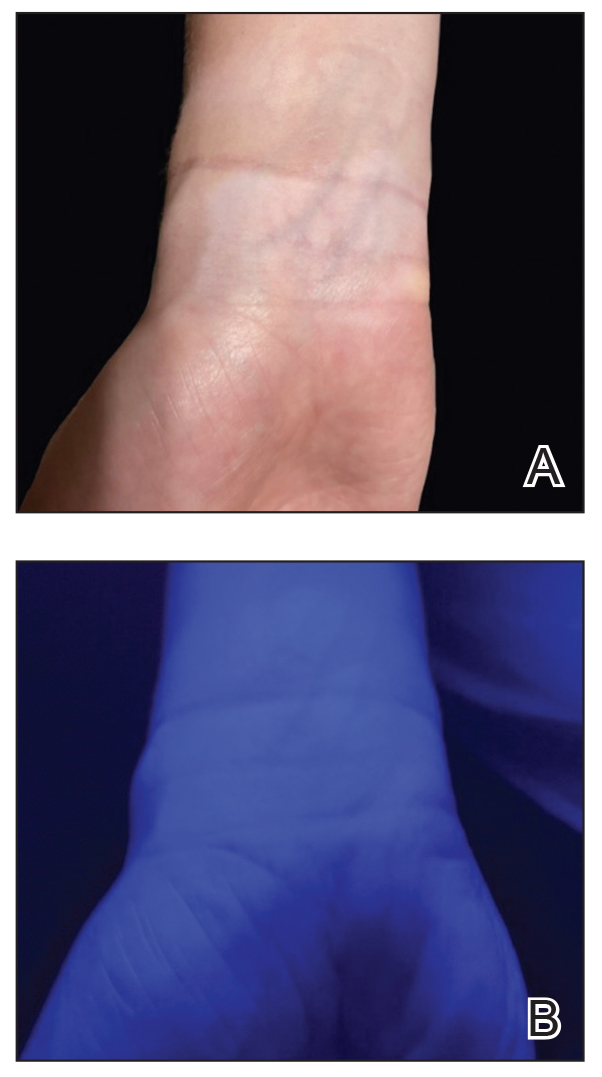

UV light apps use LED or organic LED screen pixels to emit a blue light equivalent at 467 nm.4 Although these apps are not designed specifically for dermatologic uses, they are mostly free, widely available for Android and iPhone users, and portable. Importantly, they can demonstrate good performance in visualizing vitiligo, as shown in Figure 1—albeit perhaps not reaching the same level as the Wood lamp (Figure 2).

Because these UV light apps are not regulated and their efficacy for medical use has not been firmly established, the Wood lamp remains the gold standard. Therefore, we propose the use of UV light apps in situations when a Wood lamp is not available or convenient, such as in rural, inpatient, or international health care settings.

Practice Implications

Exploring and adopting these free alternatives can contribute to improved accessibility and diagnostic capabilities in diverse health care environments, particularly for communities facing financial constraints. Continued research and validation of these apps in clinical settings will be essential to establish their reliability and effectiveness in enhancing diagnostic practices.

- Dyer JM, Foy VM. Revealing the unseen: a review of Wood’s lamp in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:25-30.

- Scanni G. Facilitations in the clinical diagnosis of human scabies through the use of ultraviolet light (UV-scab scanning): a case-series study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7:422. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7120422

- USA Medical and Surgical Supplies. Top 9 medical diagnostic applications for a Woods lamp. February 26, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2024.

- Huang Y, Hsiang E-L, Deng M-Y, et al. Mini-led, micro-led and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl. 2020;9:105. doi:10.1038/s41377-020-0341-9

Practice Gap

The Wood lamp commonly is used as a diagnostic tool for pigmentary skin conditions (eg, vitiligo) or skin conditions that exhibit fluorescence (eg, erythrasma).1 Recently, its diagnostic efficacy has extended to scabies, in which it unveils a distinctive wavy, bluish-white, linear fluorescence upon illumination.2

Functionally, the Wood lamp operates by subjecting phosphors to UV light within the wavelength range of 320 to 400 nm, inducing fluorescence in substances such as collagen and elastin. In the context of vitiligo, this process manifests as a preferential chalk white fluorescence in areas lacking melanin.1

Despite its demonstrated effectiveness, the Wood lamp is not without limitations. It comes with a notable financial investment ranging from $70 to $500, requires periodic maintenance such as light bulb replacements, and can be unwieldy.3 Furthermore, its reliance on a power source poses a challenge in settings where immediate access to convenient power outlets is limited, such as inpatient and rural dermatology clinics. These limitations underscore the need for alternative solutions and innovations to address challenges and ensure accessibility in diverse health care environments.

The Tools

Free smartphone applications (apps), such as Ultraviolet Light-UV Lamp by AppBrain or Blacklight UV Light Simulator by That Smile, can simulate UV light and functionally serve as a Wood lamp.

The Technique

UV light apps use LED or organic LED screen pixels to emit a blue light equivalent at 467 nm.4 Although these apps are not designed specifically for dermatologic uses, they are mostly free, widely available for Android and iPhone users, and portable. Importantly, they can demonstrate good performance in visualizing vitiligo, as shown in Figure 1—albeit perhaps not reaching the same level as the Wood lamp (Figure 2).

Because these UV light apps are not regulated and their efficacy for medical use has not been firmly established, the Wood lamp remains the gold standard. Therefore, we propose the use of UV light apps in situations when a Wood lamp is not available or convenient, such as in rural, inpatient, or international health care settings.

Practice Implications

Exploring and adopting these free alternatives can contribute to improved accessibility and diagnostic capabilities in diverse health care environments, particularly for communities facing financial constraints. Continued research and validation of these apps in clinical settings will be essential to establish their reliability and effectiveness in enhancing diagnostic practices.

Practice Gap

The Wood lamp commonly is used as a diagnostic tool for pigmentary skin conditions (eg, vitiligo) or skin conditions that exhibit fluorescence (eg, erythrasma).1 Recently, its diagnostic efficacy has extended to scabies, in which it unveils a distinctive wavy, bluish-white, linear fluorescence upon illumination.2

Functionally, the Wood lamp operates by subjecting phosphors to UV light within the wavelength range of 320 to 400 nm, inducing fluorescence in substances such as collagen and elastin. In the context of vitiligo, this process manifests as a preferential chalk white fluorescence in areas lacking melanin.1

Despite its demonstrated effectiveness, the Wood lamp is not without limitations. It comes with a notable financial investment ranging from $70 to $500, requires periodic maintenance such as light bulb replacements, and can be unwieldy.3 Furthermore, its reliance on a power source poses a challenge in settings where immediate access to convenient power outlets is limited, such as inpatient and rural dermatology clinics. These limitations underscore the need for alternative solutions and innovations to address challenges and ensure accessibility in diverse health care environments.

The Tools

Free smartphone applications (apps), such as Ultraviolet Light-UV Lamp by AppBrain or Blacklight UV Light Simulator by That Smile, can simulate UV light and functionally serve as a Wood lamp.

The Technique

UV light apps use LED or organic LED screen pixels to emit a blue light equivalent at 467 nm.4 Although these apps are not designed specifically for dermatologic uses, they are mostly free, widely available for Android and iPhone users, and portable. Importantly, they can demonstrate good performance in visualizing vitiligo, as shown in Figure 1—albeit perhaps not reaching the same level as the Wood lamp (Figure 2).

Because these UV light apps are not regulated and their efficacy for medical use has not been firmly established, the Wood lamp remains the gold standard. Therefore, we propose the use of UV light apps in situations when a Wood lamp is not available or convenient, such as in rural, inpatient, or international health care settings.

Practice Implications

Exploring and adopting these free alternatives can contribute to improved accessibility and diagnostic capabilities in diverse health care environments, particularly for communities facing financial constraints. Continued research and validation of these apps in clinical settings will be essential to establish their reliability and effectiveness in enhancing diagnostic practices.

- Dyer JM, Foy VM. Revealing the unseen: a review of Wood’s lamp in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:25-30.

- Scanni G. Facilitations in the clinical diagnosis of human scabies through the use of ultraviolet light (UV-scab scanning): a case-series study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7:422. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7120422

- USA Medical and Surgical Supplies. Top 9 medical diagnostic applications for a Woods lamp. February 26, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2024.

- Huang Y, Hsiang E-L, Deng M-Y, et al. Mini-led, micro-led and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl. 2020;9:105. doi:10.1038/s41377-020-0341-9

- Dyer JM, Foy VM. Revealing the unseen: a review of Wood’s lamp in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:25-30.

- Scanni G. Facilitations in the clinical diagnosis of human scabies through the use of ultraviolet light (UV-scab scanning): a case-series study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7:422. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7120422

- USA Medical and Surgical Supplies. Top 9 medical diagnostic applications for a Woods lamp. February 26, 2019. Accessed May 20, 2024.

- Huang Y, Hsiang E-L, Deng M-Y, et al. Mini-led, micro-led and OLED displays: present status and future perspectives. Light Sci Appl. 2020;9:105. doi:10.1038/s41377-020-0341-9

Purpuric Eruption in a Patient With Hairy Cell Leukemia

The Diagnosis: Purpuric Drug Eruption

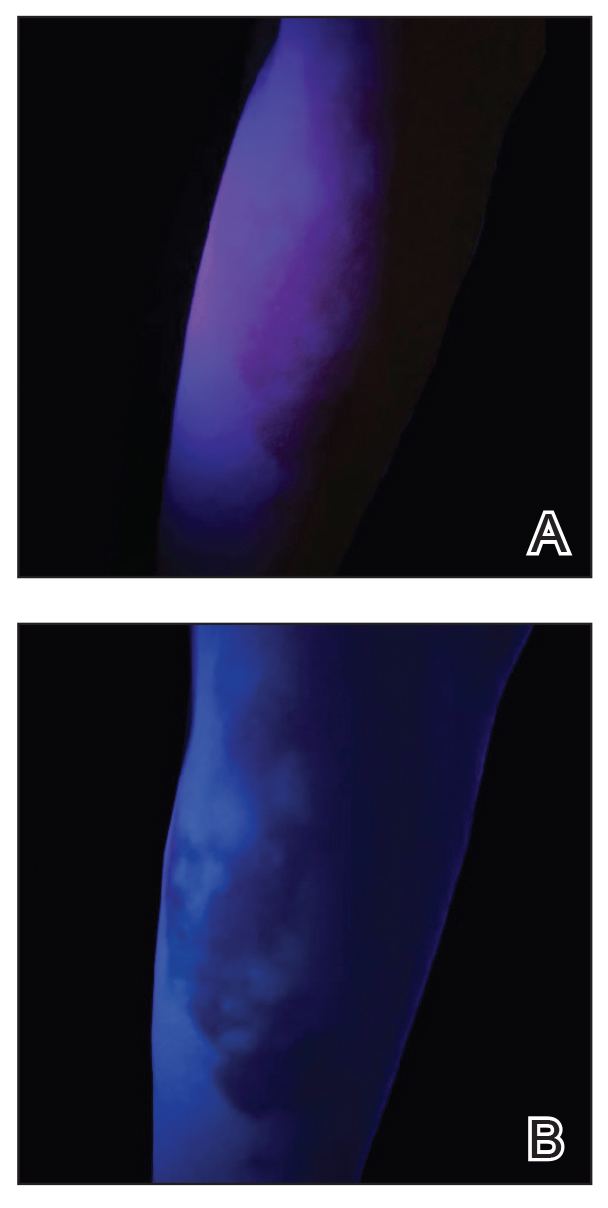

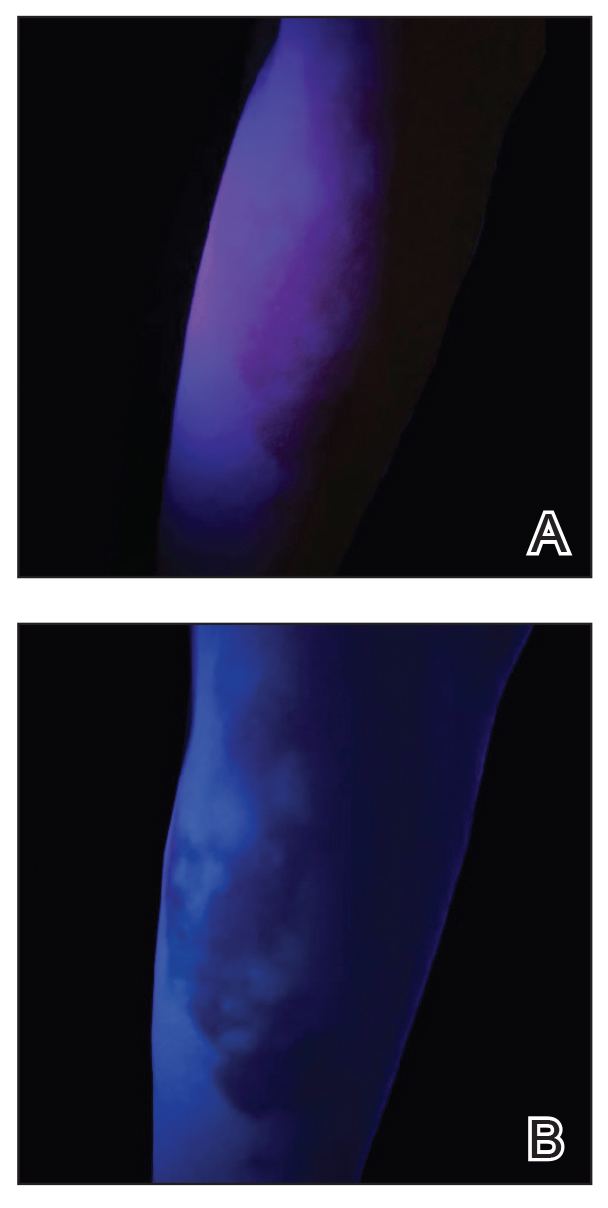

Histopathology revealed interface dermatitis, spongiosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with a purpuric drug eruption. Our patient achieved remission of hairy cell leukemia after receiving only 2 of 5 expected doses of cladribine. The rash resolved completely in 3 weeks following a prednisone taper (Figure).

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare indolent lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that accounts for approximately 2% of adult leukemias in the United States. Cladribine, a purine nucleoside analog that impairs DNA synthesis and repair, has become the mainstay of therapy, demonstrating a 95% complete response rate.1 Although few reports have addressed the cutaneous reactions seen with cladribine therapy, they can occur in more than 50% of patients.1,2 The most common skin manifestation associated with cladribine therapy is a morbilliform rash, but Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been reported.1

Few cases of purpuric eruption secondary to cladribine treatment have been described, and nearly all reports involve concomitant medications such as allopurinol, which our patient was taking, and antibiotics including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and penicillins.1,3,4 In a cohort of 35 patients receiving cladribine,1 only concomitant treatment with cladribine and allopurinol caused cutaneous reactions, further supporting the hypothesis of cladribine-induced drug sensitivity. Allopurinol often is prescribed during induction therapy for prophylaxis against tumor lysis syndrome; similarly, antibiotics frequently are given prophylactically and therapeutically for neutropenic fever. It is believed that T-cell imbalance and profound lymphopenia induced by cladribine increase susceptibility to drug hypersensitivity reactions.1,3

The typical purpuric eruption develops within 2 days of starting cladribine therapy. Diascopy will reveal petechiae, and biopsy should be performed to rule out other serious drug-induced reactions, such as erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and TEN. A cladribine-induced purpuric eruption typically is self-resolving and carries a favorable prognosis, though high-dose corticosteroids often are prescribed to hasten recovery. The rare reports of serious cutaneous reactions secondary to cladribine therapy have been with maculopapular, not purpuric eruptions.2 Based on limited available data, cladribine-induced purpura should not be a limitation to continued treatment in patients who need it.1 Careful consideration of concomitant drug use is necessary, as the current literature demonstrates resolution of rash with withdrawal of other therapies, namely allopurinol.2-4 Future studies are needed to examine the safety of withholding offending medications and to further elucidate the mechanisms contributing to drug hypersensitivity due to cladribine.

Widespread purpura and petechiae can pose a wide differential; the patient’s recent history of cladribine administration pointed to a classic purpuric eruption. Other diagnoses such as toxic erythema of chemotherapy (TEC) and TEN are not purpuric, though plaques can be violaceous. Lack of bullae, blisters, and facial or mucosal surface involvement suggest TEN.5 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation do manifest with petechiae and purpura, though such a robust eruption in the context of recent cladribine therapy is less likely. The classic retiform purpura and necrosis were not present to suggest purpura fulminans from disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Several of the proposed diagnoses as well as a purpuric drug eruption would demonstrate extravasated red blood cells on histopathology, but the presence of interface dermatitis narrows the differential to a purpuric drug eruption. Necrotic keratinocytes and full-thickness necrosis were not present on biopsy to support a diagnosis of TEN in our patient. Characteristic features of TEC—including eccrine squamous syringometaplasia, dermal edema, and keratinocyte atypia—were not present on biopsy.6 Finally, although TEN should resolve with steroid treatment, TEC is self-limited and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation would not resolve with use of steroids alone.

- Ganzel C, Gatt ME, Maly A, et al. High incidence of skin rash in patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1169-1173. doi:10.3109/10428194.2011.635864

- Chubar Y, Bennett M. Cutaneous reactions in hairy cell leukaemia treated with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and allopurinol. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:768-770. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04506.x

- Espinosa Lara P, Quirós Redondo V, Aguado Lobo M, et al. Purpuric exanthema in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine and allopurinol. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1209-1210. doi:10.1007 /s00277-017-2992-z

- Hendrick A. Purpuric rash following treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Clin Lab Haematol. 2001;23:67-68. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2257.2001.0346b.x

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Cooper DL, Glusac EJ. Toxic erythema of chemotherapy: a useful clinical term. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:524-529.

The Diagnosis: Purpuric Drug Eruption

Histopathology revealed interface dermatitis, spongiosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with a purpuric drug eruption. Our patient achieved remission of hairy cell leukemia after receiving only 2 of 5 expected doses of cladribine. The rash resolved completely in 3 weeks following a prednisone taper (Figure).

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare indolent lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that accounts for approximately 2% of adult leukemias in the United States. Cladribine, a purine nucleoside analog that impairs DNA synthesis and repair, has become the mainstay of therapy, demonstrating a 95% complete response rate.1 Although few reports have addressed the cutaneous reactions seen with cladribine therapy, they can occur in more than 50% of patients.1,2 The most common skin manifestation associated with cladribine therapy is a morbilliform rash, but Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been reported.1

Few cases of purpuric eruption secondary to cladribine treatment have been described, and nearly all reports involve concomitant medications such as allopurinol, which our patient was taking, and antibiotics including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and penicillins.1,3,4 In a cohort of 35 patients receiving cladribine,1 only concomitant treatment with cladribine and allopurinol caused cutaneous reactions, further supporting the hypothesis of cladribine-induced drug sensitivity. Allopurinol often is prescribed during induction therapy for prophylaxis against tumor lysis syndrome; similarly, antibiotics frequently are given prophylactically and therapeutically for neutropenic fever. It is believed that T-cell imbalance and profound lymphopenia induced by cladribine increase susceptibility to drug hypersensitivity reactions.1,3

The typical purpuric eruption develops within 2 days of starting cladribine therapy. Diascopy will reveal petechiae, and biopsy should be performed to rule out other serious drug-induced reactions, such as erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and TEN. A cladribine-induced purpuric eruption typically is self-resolving and carries a favorable prognosis, though high-dose corticosteroids often are prescribed to hasten recovery. The rare reports of serious cutaneous reactions secondary to cladribine therapy have been with maculopapular, not purpuric eruptions.2 Based on limited available data, cladribine-induced purpura should not be a limitation to continued treatment in patients who need it.1 Careful consideration of concomitant drug use is necessary, as the current literature demonstrates resolution of rash with withdrawal of other therapies, namely allopurinol.2-4 Future studies are needed to examine the safety of withholding offending medications and to further elucidate the mechanisms contributing to drug hypersensitivity due to cladribine.

Widespread purpura and petechiae can pose a wide differential; the patient’s recent history of cladribine administration pointed to a classic purpuric eruption. Other diagnoses such as toxic erythema of chemotherapy (TEC) and TEN are not purpuric, though plaques can be violaceous. Lack of bullae, blisters, and facial or mucosal surface involvement suggest TEN.5 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation do manifest with petechiae and purpura, though such a robust eruption in the context of recent cladribine therapy is less likely. The classic retiform purpura and necrosis were not present to suggest purpura fulminans from disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Several of the proposed diagnoses as well as a purpuric drug eruption would demonstrate extravasated red blood cells on histopathology, but the presence of interface dermatitis narrows the differential to a purpuric drug eruption. Necrotic keratinocytes and full-thickness necrosis were not present on biopsy to support a diagnosis of TEN in our patient. Characteristic features of TEC—including eccrine squamous syringometaplasia, dermal edema, and keratinocyte atypia—were not present on biopsy.6 Finally, although TEN should resolve with steroid treatment, TEC is self-limited and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation would not resolve with use of steroids alone.

The Diagnosis: Purpuric Drug Eruption

Histopathology revealed interface dermatitis, spongiosis, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with a purpuric drug eruption. Our patient achieved remission of hairy cell leukemia after receiving only 2 of 5 expected doses of cladribine. The rash resolved completely in 3 weeks following a prednisone taper (Figure).

Hairy cell leukemia is a rare indolent lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that accounts for approximately 2% of adult leukemias in the United States. Cladribine, a purine nucleoside analog that impairs DNA synthesis and repair, has become the mainstay of therapy, demonstrating a 95% complete response rate.1 Although few reports have addressed the cutaneous reactions seen with cladribine therapy, they can occur in more than 50% of patients.1,2 The most common skin manifestation associated with cladribine therapy is a morbilliform rash, but Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been reported.1

Few cases of purpuric eruption secondary to cladribine treatment have been described, and nearly all reports involve concomitant medications such as allopurinol, which our patient was taking, and antibiotics including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and penicillins.1,3,4 In a cohort of 35 patients receiving cladribine,1 only concomitant treatment with cladribine and allopurinol caused cutaneous reactions, further supporting the hypothesis of cladribine-induced drug sensitivity. Allopurinol often is prescribed during induction therapy for prophylaxis against tumor lysis syndrome; similarly, antibiotics frequently are given prophylactically and therapeutically for neutropenic fever. It is believed that T-cell imbalance and profound lymphopenia induced by cladribine increase susceptibility to drug hypersensitivity reactions.1,3

The typical purpuric eruption develops within 2 days of starting cladribine therapy. Diascopy will reveal petechiae, and biopsy should be performed to rule out other serious drug-induced reactions, such as erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and TEN. A cladribine-induced purpuric eruption typically is self-resolving and carries a favorable prognosis, though high-dose corticosteroids often are prescribed to hasten recovery. The rare reports of serious cutaneous reactions secondary to cladribine therapy have been with maculopapular, not purpuric eruptions.2 Based on limited available data, cladribine-induced purpura should not be a limitation to continued treatment in patients who need it.1 Careful consideration of concomitant drug use is necessary, as the current literature demonstrates resolution of rash with withdrawal of other therapies, namely allopurinol.2-4 Future studies are needed to examine the safety of withholding offending medications and to further elucidate the mechanisms contributing to drug hypersensitivity due to cladribine.

Widespread purpura and petechiae can pose a wide differential; the patient’s recent history of cladribine administration pointed to a classic purpuric eruption. Other diagnoses such as toxic erythema of chemotherapy (TEC) and TEN are not purpuric, though plaques can be violaceous. Lack of bullae, blisters, and facial or mucosal surface involvement suggest TEN.5 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation do manifest with petechiae and purpura, though such a robust eruption in the context of recent cladribine therapy is less likely. The classic retiform purpura and necrosis were not present to suggest purpura fulminans from disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Several of the proposed diagnoses as well as a purpuric drug eruption would demonstrate extravasated red blood cells on histopathology, but the presence of interface dermatitis narrows the differential to a purpuric drug eruption. Necrotic keratinocytes and full-thickness necrosis were not present on biopsy to support a diagnosis of TEN in our patient. Characteristic features of TEC—including eccrine squamous syringometaplasia, dermal edema, and keratinocyte atypia—were not present on biopsy.6 Finally, although TEN should resolve with steroid treatment, TEC is self-limited and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and disseminated intravascular coagulation would not resolve with use of steroids alone.

- Ganzel C, Gatt ME, Maly A, et al. High incidence of skin rash in patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1169-1173. doi:10.3109/10428194.2011.635864

- Chubar Y, Bennett M. Cutaneous reactions in hairy cell leukaemia treated with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and allopurinol. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:768-770. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04506.x

- Espinosa Lara P, Quirós Redondo V, Aguado Lobo M, et al. Purpuric exanthema in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine and allopurinol. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1209-1210. doi:10.1007 /s00277-017-2992-z

- Hendrick A. Purpuric rash following treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Clin Lab Haematol. 2001;23:67-68. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2257.2001.0346b.x

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Cooper DL, Glusac EJ. Toxic erythema of chemotherapy: a useful clinical term. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:524-529.

- Ganzel C, Gatt ME, Maly A, et al. High incidence of skin rash in patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1169-1173. doi:10.3109/10428194.2011.635864

- Chubar Y, Bennett M. Cutaneous reactions in hairy cell leukaemia treated with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine and allopurinol. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:768-770. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04506.x

- Espinosa Lara P, Quirós Redondo V, Aguado Lobo M, et al. Purpuric exanthema in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with cladribine and allopurinol. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1209-1210. doi:10.1007 /s00277-017-2992-z

- Hendrick A. Purpuric rash following treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Clin Lab Haematol. 2001;23:67-68. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-2257.2001.0346b.x

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Cooper DL, Glusac EJ. Toxic erythema of chemotherapy: a useful clinical term. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:524-529.

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with neutropenic fever and a rash over the body after receiving 2 doses of cladribine therapy for hairy cell leukemia. Physical examination demonstrated marked facial (top), lip, and tongue swelling, as well as a diffuse dusky nonpalpable purpuric rash on the abdomen (bottom) and back involving 90% of the body surface area. Bilateral ear edema was appreciated with accentuation of the earlobe crease. The patient exhibited subconjunctival hemorrhage, ectropion, and scleral injection. A punch biopsy of the thigh was performed.

Shiny Indurated Plaques on the Legs

The Diagnosis: Pretibial Myxedema

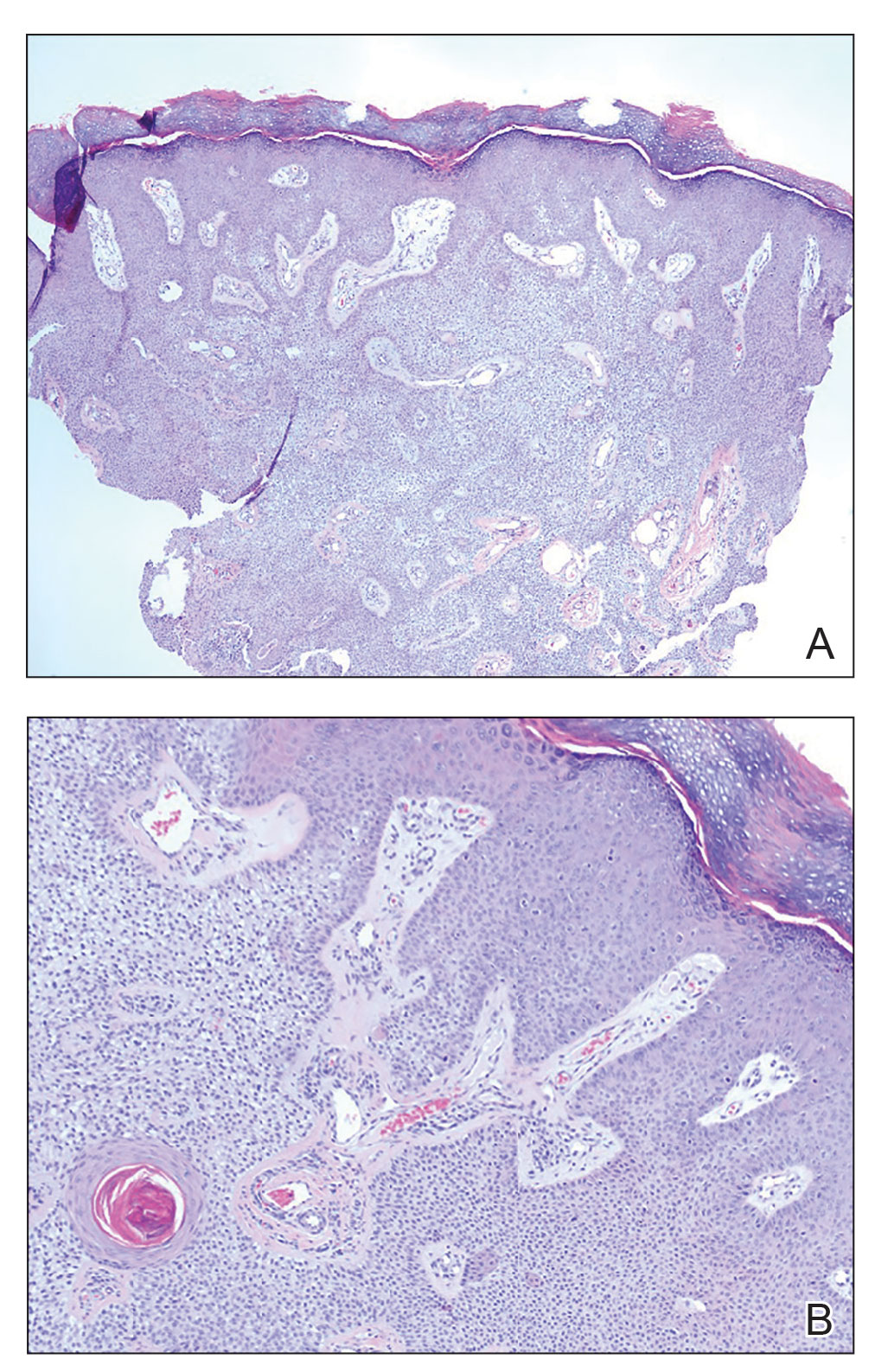

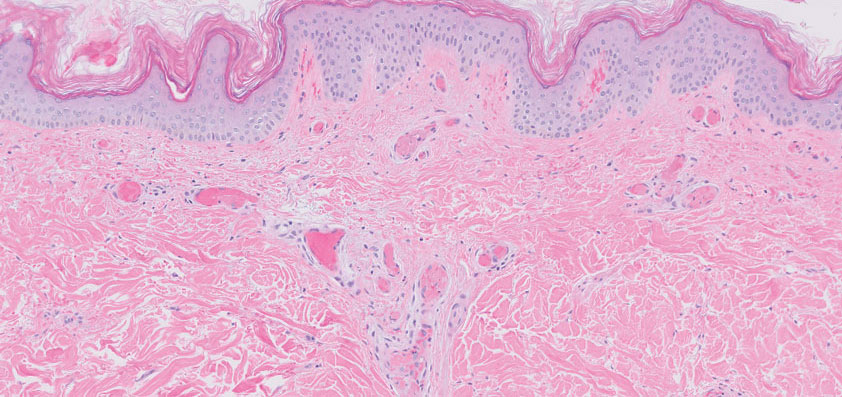

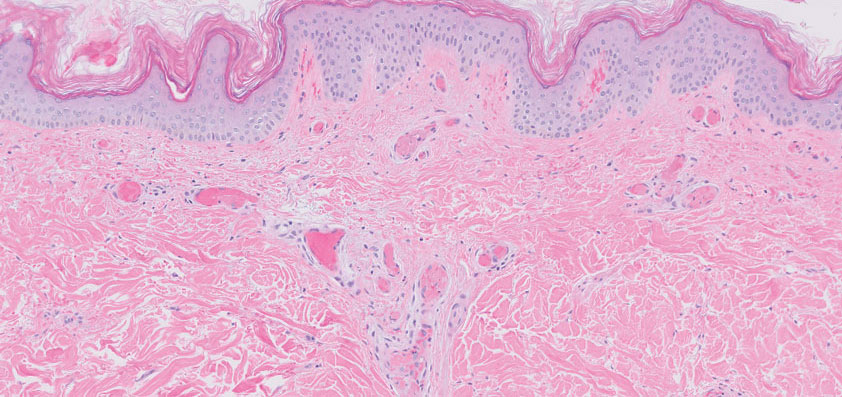

Histopathology showed superficial and deep mucin deposition with proliferation of fibroblasts and thin wiry collagen bundles that were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 3 months, followed by a trial of pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for 3 months. After this treatment failed, she was started on rituximab infusions of 1 g biweekly for 1 month, followed by 500 mg at 6 months, with marked improvement after the first 2 doses of 1 g.

Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of autoimmune thyroid disease, occurring in 1% to 5% of patients with Graves disease. It usually occurs in older adult women on the pretibial regions and less commonly on the upper extremities, face, and areas of prior trauma.1-3 Although typically asymptomatic, it can be painful and ulcerate.3 The clinical presentation consists of bilateral nonpitting edema with overlying indurated skin as well as flesh-colored, yellow-brown, violaceous, or peau d’orange papules and plaques.2,3 Lesions develop over months and often have been associated with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis.2 Many variants have been identified including nodular, plaquelike, diffuse swelling (ie, nonpitting edema), tumor, mixture, polypoid, and elephantiasis; severe cases with acral involvement are termed thyroid acropachy.1-3 Pathogenesis likely involves the activation of thyrotropin receptors on fibroblasts by the circulating thyrotropin autoantibodies found in Graves disease. Activated fibroblasts upregulate glycosaminoglycan production, which osmotically drives the accumulation of dermal and subdermal fluid.1,3

This diagnosis should be considered in any patient with pretibial edema or edema in areas of trauma. Graves disease most commonly is diagnosed 1 to 2 years prior to the development of pretibial myxedema; other extrathyroidal manifestations, most commonly ophthalmopathies, almost always are found in patients with pretibial myxedema. If a diagnosis of Graves disease has not been established, thyroid studies, including thyrotropin receptor antibody serum levels, should be obtained. Histopathology showing increased mucin in the dermis and increased fibroblasts can aid in diagnosis.2,3

The differential diagnosis includes inflammatory dermatoses, such as stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis. Stasis dermatitis is characterized by lichenified yellowbrown plaques that present on the lower extremities; lipodermatosclerosis then can develop and present as atrophic sclerotic plaques with a champagne bottle–like appearance. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates atrophic, shiny, yellow plaques with telangiectases and ulcerations. Hypertrophic lichen planus presents with hyperkeratotic hyperpigmented plaques on the shins.1,2 Other diseases of cutaneous mucin deposition, namely scleromyxedema, demonstrate similar physical findings but more commonly are located on the trunk, face, and dorsal hands rather than the lower extremities.1-3

Treatment of pretibial myxedema is difficult; normalization of thyroid function, weight reduction, and compression stockings can help reduce edema. Medical therapies aim to decrease glycosaminoglycan production by fibroblasts. First-line treatment includes topical steroids under occlusion, and second-line therapies include intralesional steroids, systemic corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, and octreotide.2,3 Therapies for refractory disease include plasmapheresis, surgical excision, radiotherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin; more recent studies also endorse the use of isotretinoin, intralesional hyaluronidase, and rituximab.2,4 Success also has been observed with the insulin growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor teprotumumab in active thyroid eye disease, in which insulin growth factor 1 receptor is overexpressed by fibroblasts. Given the similar pathogenesis of thyroid ophthalmopathy with other extrathyroidal manifestations, teprotumumab is a promising option for refractory cases of pretibial myxedema and has led to disease resolution in several patients.4

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7. doi:10.1097/00005792-199401000-00001

- Ai J, Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Autoimmune thyroid diseases: etiology, pathogenesis, and dermatologic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:641-662. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.257

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8220

- Varma A, Rheeman C, Levitt J. Resolution of pretibial myxedema with teprotumumab in a patient with Graves disease. JAAD Case Reports. 2020;6:1281-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.09.003

The Diagnosis: Pretibial Myxedema

Histopathology showed superficial and deep mucin deposition with proliferation of fibroblasts and thin wiry collagen bundles that were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 3 months, followed by a trial of pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for 3 months. After this treatment failed, she was started on rituximab infusions of 1 g biweekly for 1 month, followed by 500 mg at 6 months, with marked improvement after the first 2 doses of 1 g.

Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of autoimmune thyroid disease, occurring in 1% to 5% of patients with Graves disease. It usually occurs in older adult women on the pretibial regions and less commonly on the upper extremities, face, and areas of prior trauma.1-3 Although typically asymptomatic, it can be painful and ulcerate.3 The clinical presentation consists of bilateral nonpitting edema with overlying indurated skin as well as flesh-colored, yellow-brown, violaceous, or peau d’orange papules and plaques.2,3 Lesions develop over months and often have been associated with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis.2 Many variants have been identified including nodular, plaquelike, diffuse swelling (ie, nonpitting edema), tumor, mixture, polypoid, and elephantiasis; severe cases with acral involvement are termed thyroid acropachy.1-3 Pathogenesis likely involves the activation of thyrotropin receptors on fibroblasts by the circulating thyrotropin autoantibodies found in Graves disease. Activated fibroblasts upregulate glycosaminoglycan production, which osmotically drives the accumulation of dermal and subdermal fluid.1,3

This diagnosis should be considered in any patient with pretibial edema or edema in areas of trauma. Graves disease most commonly is diagnosed 1 to 2 years prior to the development of pretibial myxedema; other extrathyroidal manifestations, most commonly ophthalmopathies, almost always are found in patients with pretibial myxedema. If a diagnosis of Graves disease has not been established, thyroid studies, including thyrotropin receptor antibody serum levels, should be obtained. Histopathology showing increased mucin in the dermis and increased fibroblasts can aid in diagnosis.2,3

The differential diagnosis includes inflammatory dermatoses, such as stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis. Stasis dermatitis is characterized by lichenified yellowbrown plaques that present on the lower extremities; lipodermatosclerosis then can develop and present as atrophic sclerotic plaques with a champagne bottle–like appearance. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates atrophic, shiny, yellow plaques with telangiectases and ulcerations. Hypertrophic lichen planus presents with hyperkeratotic hyperpigmented plaques on the shins.1,2 Other diseases of cutaneous mucin deposition, namely scleromyxedema, demonstrate similar physical findings but more commonly are located on the trunk, face, and dorsal hands rather than the lower extremities.1-3

Treatment of pretibial myxedema is difficult; normalization of thyroid function, weight reduction, and compression stockings can help reduce edema. Medical therapies aim to decrease glycosaminoglycan production by fibroblasts. First-line treatment includes topical steroids under occlusion, and second-line therapies include intralesional steroids, systemic corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, and octreotide.2,3 Therapies for refractory disease include plasmapheresis, surgical excision, radiotherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin; more recent studies also endorse the use of isotretinoin, intralesional hyaluronidase, and rituximab.2,4 Success also has been observed with the insulin growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor teprotumumab in active thyroid eye disease, in which insulin growth factor 1 receptor is overexpressed by fibroblasts. Given the similar pathogenesis of thyroid ophthalmopathy with other extrathyroidal manifestations, teprotumumab is a promising option for refractory cases of pretibial myxedema and has led to disease resolution in several patients.4

The Diagnosis: Pretibial Myxedema

Histopathology showed superficial and deep mucin deposition with proliferation of fibroblasts and thin wiry collagen bundles that were consistent with a diagnosis of pretibial myxedema. The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 3 months, followed by a trial of pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily for 3 months. After this treatment failed, she was started on rituximab infusions of 1 g biweekly for 1 month, followed by 500 mg at 6 months, with marked improvement after the first 2 doses of 1 g.

Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of autoimmune thyroid disease, occurring in 1% to 5% of patients with Graves disease. It usually occurs in older adult women on the pretibial regions and less commonly on the upper extremities, face, and areas of prior trauma.1-3 Although typically asymptomatic, it can be painful and ulcerate.3 The clinical presentation consists of bilateral nonpitting edema with overlying indurated skin as well as flesh-colored, yellow-brown, violaceous, or peau d’orange papules and plaques.2,3 Lesions develop over months and often have been associated with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis.2 Many variants have been identified including nodular, plaquelike, diffuse swelling (ie, nonpitting edema), tumor, mixture, polypoid, and elephantiasis; severe cases with acral involvement are termed thyroid acropachy.1-3 Pathogenesis likely involves the activation of thyrotropin receptors on fibroblasts by the circulating thyrotropin autoantibodies found in Graves disease. Activated fibroblasts upregulate glycosaminoglycan production, which osmotically drives the accumulation of dermal and subdermal fluid.1,3

This diagnosis should be considered in any patient with pretibial edema or edema in areas of trauma. Graves disease most commonly is diagnosed 1 to 2 years prior to the development of pretibial myxedema; other extrathyroidal manifestations, most commonly ophthalmopathies, almost always are found in patients with pretibial myxedema. If a diagnosis of Graves disease has not been established, thyroid studies, including thyrotropin receptor antibody serum levels, should be obtained. Histopathology showing increased mucin in the dermis and increased fibroblasts can aid in diagnosis.2,3

The differential diagnosis includes inflammatory dermatoses, such as stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis. Stasis dermatitis is characterized by lichenified yellowbrown plaques that present on the lower extremities; lipodermatosclerosis then can develop and present as atrophic sclerotic plaques with a champagne bottle–like appearance. Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates atrophic, shiny, yellow plaques with telangiectases and ulcerations. Hypertrophic lichen planus presents with hyperkeratotic hyperpigmented plaques on the shins.1,2 Other diseases of cutaneous mucin deposition, namely scleromyxedema, demonstrate similar physical findings but more commonly are located on the trunk, face, and dorsal hands rather than the lower extremities.1-3

Treatment of pretibial myxedema is difficult; normalization of thyroid function, weight reduction, and compression stockings can help reduce edema. Medical therapies aim to decrease glycosaminoglycan production by fibroblasts. First-line treatment includes topical steroids under occlusion, and second-line therapies include intralesional steroids, systemic corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, and octreotide.2,3 Therapies for refractory disease include plasmapheresis, surgical excision, radiotherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin; more recent studies also endorse the use of isotretinoin, intralesional hyaluronidase, and rituximab.2,4 Success also has been observed with the insulin growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor teprotumumab in active thyroid eye disease, in which insulin growth factor 1 receptor is overexpressed by fibroblasts. Given the similar pathogenesis of thyroid ophthalmopathy with other extrathyroidal manifestations, teprotumumab is a promising option for refractory cases of pretibial myxedema and has led to disease resolution in several patients.4

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7. doi:10.1097/00005792-199401000-00001

- Ai J, Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Autoimmune thyroid diseases: etiology, pathogenesis, and dermatologic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:641-662. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.257

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8220

- Varma A, Rheeman C, Levitt J. Resolution of pretibial myxedema with teprotumumab in a patient with Graves disease. JAAD Case Reports. 2020;6:1281-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.09.003

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7. doi:10.1097/00005792-199401000-00001

- Ai J, Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Autoimmune thyroid diseases: etiology, pathogenesis, and dermatologic manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:641-662. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.257

- Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DDF, et al. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8220

- Varma A, Rheeman C, Levitt J. Resolution of pretibial myxedema with teprotumumab in a patient with Graves disease. JAAD Case Reports. 2020;6:1281-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.09.003

A 70-year-old woman presented with pain and swelling in both legs of many years’ duration. She had no history of skin disease. Physical examination revealed shiny indurated plaques on the legs, ankles, and toes with limited range of motion in the ankles (top). Marked thickening of the hands and index fingers also was noted (bottom). A punch biopsy of the distal pretibial region was performed.

Oval Brown Plaque on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Poroma

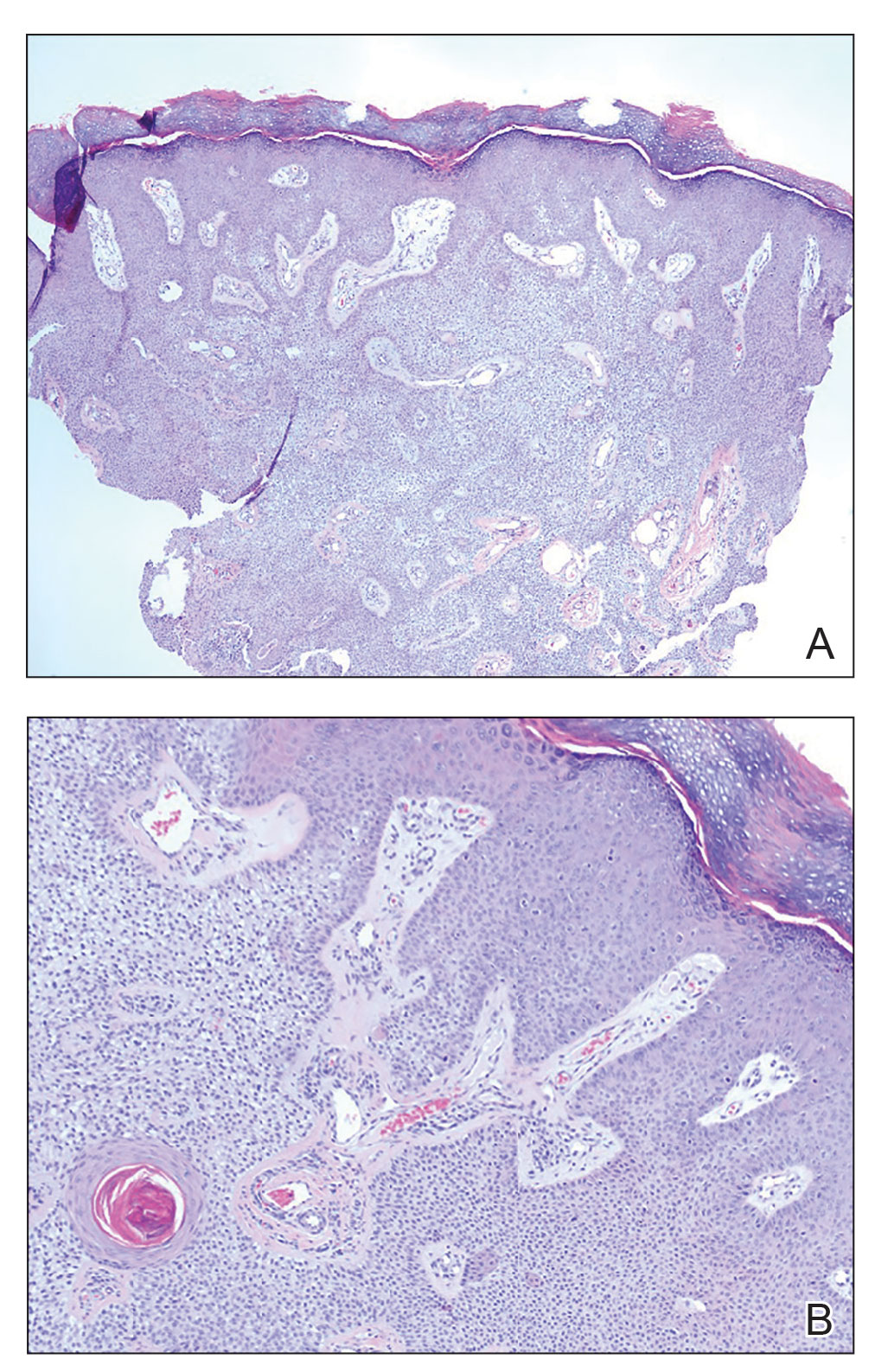

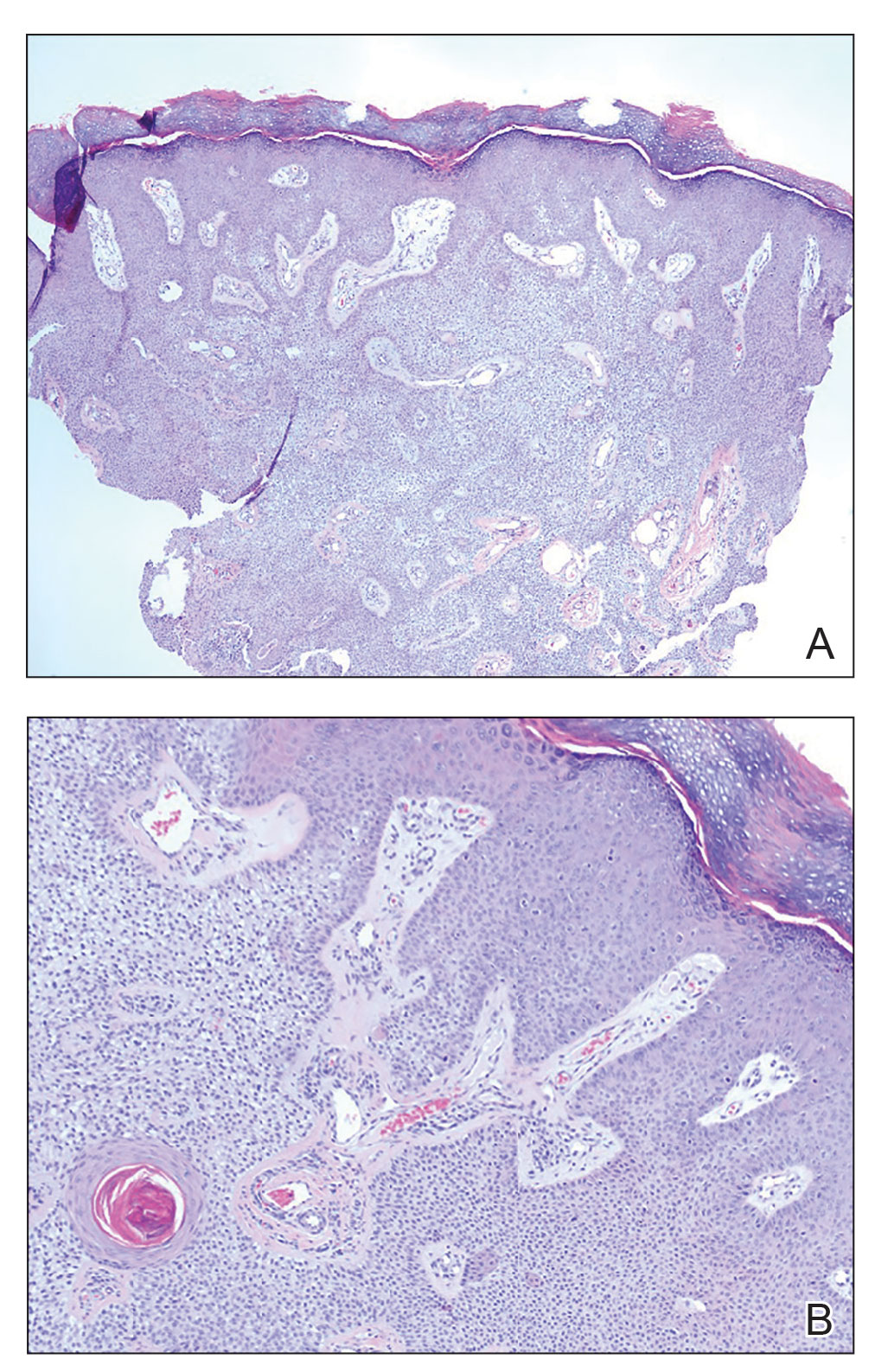

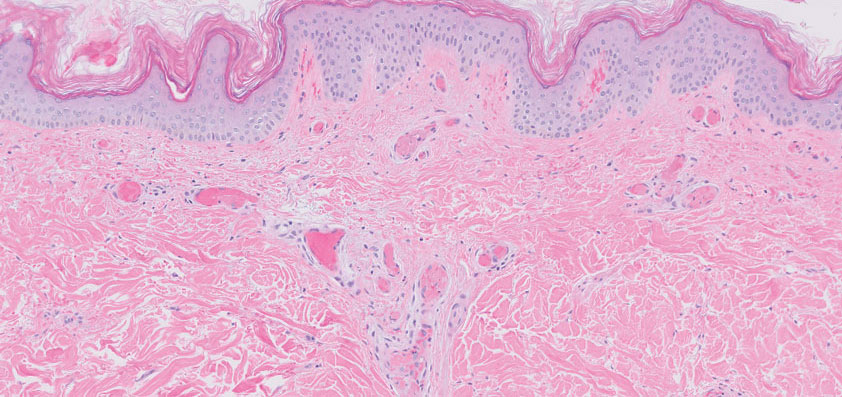

Histopathology showed an endophytic expansion of the epidermis by bland, uniform, basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductal differentiation and an abrupt transition with surrounding epidermal keratinocytes (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of poroma. The patient elected to monitor the lesion rather than to have it excised.

Eccrine poroma, used interchangeably with the term poroma, is a rare benign adnexal tumor of the eccrine sweat glands resulting from proliferation of the acrosyringium.1,2 It often occurs on the palms or soles, though it also can arise anywhere sweat glands are present.1 Eccrine poromas often appear in middle-aged individuals as singular, well-circumscribed, red-brown papules or nodules.3 A characteristic feature is a shallow, cup-shaped depression within the larger papule or nodule.1

Because the condition is benign and often asymptomatic, it can be safely monitored for progression.1 However, if the lesion is symptomatic or located in a sensitive area, complete excision is curative.4 Eccrine poromas can recur, making close monitoring following excision important.5 The development of bleeding, itching, or pain in a previously asymptomatic lesion may indicate possible malignant transformation, which occurs in only 18% of cases.6

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, circumscribed acral hypokeratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.7 In rare cases it has been shown to present on the palms or soles as a slowgrowing, reddish-pink papule or plaque with central ulceration. It typically is asymptomatic. Histopathology shows dermal nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, stromal mucin, and peritumoral clefts. Treatment is surgical excision.7

Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis presents on the palms or soles as a solitary, shallow, well-defined lesion with a flat base and raised border.8 It often is red-pink in color and most frequently occurs in middle-aged women. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, it is thought to be the result of trauma or human papillomavirus infection.8 Biopsy results characteristically show hypokeratosis demarcated by a sharp and frayed cutoff from uninvolved acral skin with discrete hypogranulosis, dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and slightly thickened collagen fibers in the reticular dermis.9 Surgical excision is a potential treatment option, as topical corticosteroids, retinoids, and calcipotriene have not been shown to be effective; spontaneous resolution has been reported.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that is associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection.10 It typically presents on mucocutaneous sites and the lower extremities. Palmar involvement has been reported in rare cases, occurring as a solitary, well-demarcated, violaceous macule or patch that may be painful.10-12 Characteristic histopathologic features include a proliferation in the dermis of slitlike vascular spaces and spindle cell proliferation.13 Treatment options include cryosurgery; pulsed dye laser; and topical, intralesional, or systemic chemotherapy agents, depending on the stage of the patient’s disease. Antiretroviral therapy is indicated for patients with Kaposi sarcoma secondary to AIDS.14

Pyogenic granuloma presents as a solitary red-brown or bluish-black papule or nodule that bleeds easily when manipulated.15 It commonly occurs following trauma, typically on the fingers, feet, and lips.6 Although benign, potential complications include ulceration and blood loss. Pyogenic granulomas can be treated via curettage and cautery, excision, cryosurgery, or pulsed dye laser.15

- Wankhade V, Singh R, Sadhwani V, et al. Eccrine poroma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:304-305.

- Yorulmaz A, Aksoy GG, Ozhamam EU. A growing mass under the nail: subungual eccrine poroma. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:254-257.

- Wang Y, Liu M, Zheng Y, et al. Eccrine poroma presented as spindleshaped plaque: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E25971. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025971

- Sharma M, Singh M, Gupta K, et al. Eccrine poroma of the eyelid. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:2522.

- Rasool MN, Hawary MB. Benign eccrine poroma in the palm of the hand. Ann Saudi Med. 2004;24:46-47.

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms [published online April 2, 2014]. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061. doi:10.1111/ijd.12448

- López-Sánchez C, Ferguson P, Collgros H. Basal cell carcinoma of the palm: an unusual presentation of a common tumour [published online August 6, 2019]. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:69-70. doi:10.1111/ajd.13129

- Berk DR, Böer A, Bauschard FD, et al. Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis [published online April 6, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:292-296. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.022

- Majluf-Cáceres P, Vera-Kellet C, González-Bombardiere S. New dermoscopic keys for circumscribed acral hypokeratosis: report of four cases. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021010. doi:10.5826/dpc.1102a10

- Simonart T, De Dobbeleer G, Stallenberg B. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma of the palm in a metallurgist: role of iron filings in its development? Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1061-1063. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05331.x

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0101-RS

- Al Zolibani AA, Al Robaee AA. Primary palmoplantar Kaposi’s sarcoma: an unusual presentation. Skinmed. 2006;5:248-249. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2006.04662.x

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, et al. Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:9. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates [published online July 10, 2019]. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517. doi:10.1016/j. det.2019.05.008

- Murthy SC, Nagaraj A. Pyogenic granuloma. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:855. doi:10.1007/s13312-012-0184-4

The Diagnosis: Poroma

Histopathology showed an endophytic expansion of the epidermis by bland, uniform, basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductal differentiation and an abrupt transition with surrounding epidermal keratinocytes (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of poroma. The patient elected to monitor the lesion rather than to have it excised.

Eccrine poroma, used interchangeably with the term poroma, is a rare benign adnexal tumor of the eccrine sweat glands resulting from proliferation of the acrosyringium.1,2 It often occurs on the palms or soles, though it also can arise anywhere sweat glands are present.1 Eccrine poromas often appear in middle-aged individuals as singular, well-circumscribed, red-brown papules or nodules.3 A characteristic feature is a shallow, cup-shaped depression within the larger papule or nodule.1

Because the condition is benign and often asymptomatic, it can be safely monitored for progression.1 However, if the lesion is symptomatic or located in a sensitive area, complete excision is curative.4 Eccrine poromas can recur, making close monitoring following excision important.5 The development of bleeding, itching, or pain in a previously asymptomatic lesion may indicate possible malignant transformation, which occurs in only 18% of cases.6

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, circumscribed acral hypokeratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.7 In rare cases it has been shown to present on the palms or soles as a slowgrowing, reddish-pink papule or plaque with central ulceration. It typically is asymptomatic. Histopathology shows dermal nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, stromal mucin, and peritumoral clefts. Treatment is surgical excision.7

Circumscribed acral hypokeratosis presents on the palms or soles as a solitary, shallow, well-defined lesion with a flat base and raised border.8 It often is red-pink in color and most frequently occurs in middle-aged women. Although the cause of the condition is unknown, it is thought to be the result of trauma or human papillomavirus infection.8 Biopsy results characteristically show hypokeratosis demarcated by a sharp and frayed cutoff from uninvolved acral skin with discrete hypogranulosis, dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and slightly thickened collagen fibers in the reticular dermis.9 Surgical excision is a potential treatment option, as topical corticosteroids, retinoids, and calcipotriene have not been shown to be effective; spontaneous resolution has been reported.8

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm that is associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection.10 It typically presents on mucocutaneous sites and the lower extremities. Palmar involvement has been reported in rare cases, occurring as a solitary, well-demarcated, violaceous macule or patch that may be painful.10-12 Characteristic histopathologic features include a proliferation in the dermis of slitlike vascular spaces and spindle cell proliferation.13 Treatment options include cryosurgery; pulsed dye laser; and topical, intralesional, or systemic chemotherapy agents, depending on the stage of the patient’s disease. Antiretroviral therapy is indicated for patients with Kaposi sarcoma secondary to AIDS.14

Pyogenic granuloma presents as a solitary red-brown or bluish-black papule or nodule that bleeds easily when manipulated.15 It commonly occurs following trauma, typically on the fingers, feet, and lips.6 Although benign, potential complications include ulceration and blood loss. Pyogenic granulomas can be treated via curettage and cautery, excision, cryosurgery, or pulsed dye laser.15

The Diagnosis: Poroma

Histopathology showed an endophytic expansion of the epidermis by bland, uniform, basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductal differentiation and an abrupt transition with surrounding epidermal keratinocytes (Figure), consistent with a diagnosis of poroma. The patient elected to monitor the lesion rather than to have it excised.

Eccrine poroma, used interchangeably with the term poroma, is a rare benign adnexal tumor of the eccrine sweat glands resulting from proliferation of the acrosyringium.1,2 It often occurs on the palms or soles, though it also can arise anywhere sweat glands are present.1 Eccrine poromas often appear in middle-aged individuals as singular, well-circumscribed, red-brown papules or nodules.3 A characteristic feature is a shallow, cup-shaped depression within the larger papule or nodule.1

Because the condition is benign and often asymptomatic, it can be safely monitored for progression.1 However, if the lesion is symptomatic or located in a sensitive area, complete excision is curative.4 Eccrine poromas can recur, making close monitoring following excision important.5 The development of bleeding, itching, or pain in a previously asymptomatic lesion may indicate possible malignant transformation, which occurs in only 18% of cases.6

The differential diagnosis includes basal cell carcinoma, circumscribed acral hypokeratosis, Kaposi sarcoma, and pyogenic granuloma. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer.7 In rare cases it has been shown to present on the palms or soles as a slowgrowing, reddish-pink papule or plaque with central ulceration. It typically is asymptomatic. Histopathology shows dermal nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading, stromal mucin, and peritumoral clefts. Treatment is surgical excision.7