User login

Is Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Connected to Sunscreen Usage?

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has become increasingly common since it was first described in 1994.1 A positive correlation between FFA and the use of sunscreens was reported in an observational study.2 The geographic distribution of this association has spanned the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, and Asia, though data from the United States are lacking. Various international studies have demonstrated an association between FFA and sunscreen use, further exemplifying this stark contrast.

In the United Kingdom (UK), Aldoori et al2 found that women who used sunscreen at least twice weekly had 2 times the likelihood of developing FFA compared with women who did not use sunscreen regularly. Kidambi et al3 found similar results in UK men with FFA who had higher rates of primary sunscreen use and higher rates of at least twice-weekly use of facial moisturizer with unspecified sunscreen content.

These associations between FFA and sunscreen use are not unique to the UK. A study conducted in Spain identified a statistical association between FFA and use of facial sunscreen in women (odds ratio, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.06-2.41]) and men (odds ratio, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.04-3.23]).4 In Thailand, FFA was nearly twice as likely to be present in patients with regular sunscreen use compared to controls who did not apply sunscreen regularly.5 Interestingly, a Brazilian study showed no connection between sunscreen use and FFA. Instead, FFA was associated with hair straightening with formalin or use of facial soap orfacial moisturizer.6 An international systematic review of 1248 patients with FFA and 1459 controls determined that sunscreen users were 2.21 times more likely to develop FFA than their counterparts who did not use sunscreen regularly.7

Quite glaring is the lack of data from the United States, which could be used to compare FFA and sunscreen associations to other nations. It is possible that certain regions of the world such as the United States may not have an increased risk for FFA in sunscreen users due to other environmental factors, differing sunscreen application practices, or differing chemical ingredients. At the same time, many other countries cannot afford or lack access to sunscreens or facial moisturizers, which is an additional variable that may complicate this association. These populations need to be studied to determine whether they are as susceptible to FFA as those who use sunscreen regularly around the world.

Another underlying factor supporting this association is the inherent need for sunscreen use. For instance, research has shown that patients with FFA had higher rates of actinic skin damage, which could explain increased sunscreen use.8

To make more clear and distinct claims, further studies are needed in regions that are known to use sunscreen extensively (eg, United States) to compare with their European, Asian, and South American counterparts. Moreover, it also is important to study regions where sunscreen access is limited and whether there is FFA development in these populations.

Given the potential association between sunscreen use and FFA, dermatologists can take a cautious approach tailored to the patient by recommending noncomedogenic mineral sunscreens with zinc or titanium oxide, which are less irritating than chemical sunscreens. Avoidance of sunscreen application to the hairline and use of additional sun-protection methods such as broad-brimmed hats also should be emphasized.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690060100013

- Aldoori N, Dobson K, Holden CR, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: possible association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens: a questionnaire study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:762-767.

- Kidambi AD, Dobson K, Holmes S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with leave-on facial cosmetics and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2020;175:61-67.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Rodrigues-Barata AR, et al. Risk factors associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicentre case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:404-410. doi:10.1111/ced.13785

- Leecharoen W, Thanomkitti K, Thuangtong R, et al. Use of facial care products and frontal fibrosing alopecia: coincidence or true association? J Dermatol. 2021;48:1557-1563.

- Müller Ramos P, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.07

- Kam O, Na S, Guo W, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and personal care product use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2313-2331. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02604-7

- Porriño-Bustamante ML, Montero-Vílchez T, Pinedo-Moraleda FJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and sunscreen use: a cross-sectionalstudy of actinic damage. Acta Derm Venereol. Published online August 11, 2022. doi:10.2340/actadv.v102.306

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has become increasingly common since it was first described in 1994.1 A positive correlation between FFA and the use of sunscreens was reported in an observational study.2 The geographic distribution of this association has spanned the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, and Asia, though data from the United States are lacking. Various international studies have demonstrated an association between FFA and sunscreen use, further exemplifying this stark contrast.

In the United Kingdom (UK), Aldoori et al2 found that women who used sunscreen at least twice weekly had 2 times the likelihood of developing FFA compared with women who did not use sunscreen regularly. Kidambi et al3 found similar results in UK men with FFA who had higher rates of primary sunscreen use and higher rates of at least twice-weekly use of facial moisturizer with unspecified sunscreen content.

These associations between FFA and sunscreen use are not unique to the UK. A study conducted in Spain identified a statistical association between FFA and use of facial sunscreen in women (odds ratio, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.06-2.41]) and men (odds ratio, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.04-3.23]).4 In Thailand, FFA was nearly twice as likely to be present in patients with regular sunscreen use compared to controls who did not apply sunscreen regularly.5 Interestingly, a Brazilian study showed no connection between sunscreen use and FFA. Instead, FFA was associated with hair straightening with formalin or use of facial soap orfacial moisturizer.6 An international systematic review of 1248 patients with FFA and 1459 controls determined that sunscreen users were 2.21 times more likely to develop FFA than their counterparts who did not use sunscreen regularly.7

Quite glaring is the lack of data from the United States, which could be used to compare FFA and sunscreen associations to other nations. It is possible that certain regions of the world such as the United States may not have an increased risk for FFA in sunscreen users due to other environmental factors, differing sunscreen application practices, or differing chemical ingredients. At the same time, many other countries cannot afford or lack access to sunscreens or facial moisturizers, which is an additional variable that may complicate this association. These populations need to be studied to determine whether they are as susceptible to FFA as those who use sunscreen regularly around the world.

Another underlying factor supporting this association is the inherent need for sunscreen use. For instance, research has shown that patients with FFA had higher rates of actinic skin damage, which could explain increased sunscreen use.8

To make more clear and distinct claims, further studies are needed in regions that are known to use sunscreen extensively (eg, United States) to compare with their European, Asian, and South American counterparts. Moreover, it also is important to study regions where sunscreen access is limited and whether there is FFA development in these populations.

Given the potential association between sunscreen use and FFA, dermatologists can take a cautious approach tailored to the patient by recommending noncomedogenic mineral sunscreens with zinc or titanium oxide, which are less irritating than chemical sunscreens. Avoidance of sunscreen application to the hairline and use of additional sun-protection methods such as broad-brimmed hats also should be emphasized.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) has become increasingly common since it was first described in 1994.1 A positive correlation between FFA and the use of sunscreens was reported in an observational study.2 The geographic distribution of this association has spanned the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, and Asia, though data from the United States are lacking. Various international studies have demonstrated an association between FFA and sunscreen use, further exemplifying this stark contrast.

In the United Kingdom (UK), Aldoori et al2 found that women who used sunscreen at least twice weekly had 2 times the likelihood of developing FFA compared with women who did not use sunscreen regularly. Kidambi et al3 found similar results in UK men with FFA who had higher rates of primary sunscreen use and higher rates of at least twice-weekly use of facial moisturizer with unspecified sunscreen content.

These associations between FFA and sunscreen use are not unique to the UK. A study conducted in Spain identified a statistical association between FFA and use of facial sunscreen in women (odds ratio, 1.6 [95% CI, 1.06-2.41]) and men (odds ratio, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.04-3.23]).4 In Thailand, FFA was nearly twice as likely to be present in patients with regular sunscreen use compared to controls who did not apply sunscreen regularly.5 Interestingly, a Brazilian study showed no connection between sunscreen use and FFA. Instead, FFA was associated with hair straightening with formalin or use of facial soap orfacial moisturizer.6 An international systematic review of 1248 patients with FFA and 1459 controls determined that sunscreen users were 2.21 times more likely to develop FFA than their counterparts who did not use sunscreen regularly.7

Quite glaring is the lack of data from the United States, which could be used to compare FFA and sunscreen associations to other nations. It is possible that certain regions of the world such as the United States may not have an increased risk for FFA in sunscreen users due to other environmental factors, differing sunscreen application practices, or differing chemical ingredients. At the same time, many other countries cannot afford or lack access to sunscreens or facial moisturizers, which is an additional variable that may complicate this association. These populations need to be studied to determine whether they are as susceptible to FFA as those who use sunscreen regularly around the world.

Another underlying factor supporting this association is the inherent need for sunscreen use. For instance, research has shown that patients with FFA had higher rates of actinic skin damage, which could explain increased sunscreen use.8

To make more clear and distinct claims, further studies are needed in regions that are known to use sunscreen extensively (eg, United States) to compare with their European, Asian, and South American counterparts. Moreover, it also is important to study regions where sunscreen access is limited and whether there is FFA development in these populations.

Given the potential association between sunscreen use and FFA, dermatologists can take a cautious approach tailored to the patient by recommending noncomedogenic mineral sunscreens with zinc or titanium oxide, which are less irritating than chemical sunscreens. Avoidance of sunscreen application to the hairline and use of additional sun-protection methods such as broad-brimmed hats also should be emphasized.

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690060100013

- Aldoori N, Dobson K, Holden CR, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: possible association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens: a questionnaire study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:762-767.

- Kidambi AD, Dobson K, Holmes S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with leave-on facial cosmetics and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2020;175:61-67.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Rodrigues-Barata AR, et al. Risk factors associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicentre case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:404-410. doi:10.1111/ced.13785

- Leecharoen W, Thanomkitti K, Thuangtong R, et al. Use of facial care products and frontal fibrosing alopecia: coincidence or true association? J Dermatol. 2021;48:1557-1563.

- Müller Ramos P, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.07

- Kam O, Na S, Guo W, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and personal care product use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2313-2331. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02604-7

- Porriño-Bustamante ML, Montero-Vílchez T, Pinedo-Moraleda FJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and sunscreen use: a cross-sectionalstudy of actinic damage. Acta Derm Venereol. Published online August 11, 2022. doi:10.2340/actadv.v102.306

- Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690060100013

- Aldoori N, Dobson K, Holden CR, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: possible association with leave-on facial skin care products and sunscreens: a questionnaire study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:762-767.

- Kidambi AD, Dobson K, Holmes S, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with leave-on facial cosmetics and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2020;175:61-67.

- Moreno-Arrones OM, Saceda-Corralo D, Rodrigues-Barata AR, et al. Risk factors associated with frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicentre case-control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:404-410. doi:10.1111/ced.13785

- Leecharoen W, Thanomkitti K, Thuangtong R, et al. Use of facial care products and frontal fibrosing alopecia: coincidence or true association? J Dermatol. 2021;48:1557-1563.

- Müller Ramos P, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, et al. Risk factors for frontal fibrosing alopecia: a case-control study in a multiracial population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:712-718. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.07

- Kam O, Na S, Guo W, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and personal care product use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2313-2331. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02604-7

- Porriño-Bustamante ML, Montero-Vílchez T, Pinedo-Moraleda FJ, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia and sunscreen use: a cross-sectionalstudy of actinic damage. Acta Derm Venereol. Published online August 11, 2022. doi:10.2340/actadv.v102.306

Evaluating the Cost Burden of Alopecia Areata Treatment: A Comprehensive Review for Dermatologists

Alopecia areata (AA) affects 4.5 million individuals in the United States, with 66% younger than 30 years.1,2 Inflammation causes hair loss in well-circumscribed, nonscarring patches on the body with a predilection for the scalp.3-6 The disease can devastate a patient’s self-esteem, in turn reducing quality of life.1,7 Alopecia areata is an autoimmune T-cell–mediated disease in which hair follicles lose their immune privilege.8-10 Several specific mechanisms in the cytokine interactions between T cells and the hair follicle have been discovered, revealing the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway as pivotal in the pathogenesis of the disease and leading to the use of JAK inhibitors for treatment.11

There is no cure for AA, and the condition is managed with prolonged medical treatments and cosmetic therapies.2 Although some patients may be able to manage the annual cost, the cumulative cost of AA treatment can be burdensome.12 This cumulative cost may increase if newer, potentially expensive treatments become the standard of care. Patients with AA report dipping into their savings (41.3%) and cutting back on food or clothing expenses (33.9%) to account for the cost of alopecia treatment. Although prior estimates of the annual out-of-pocket cost of AA treatments range from $1354 to $2685, the cost burden of individual therapies is poorly understood.12-14

Patients who must juggle expensive medical bills with basic living expenses may be lost to follow-up or fall into treatment nonadherence.15 Other patients’ out-of-pocket costs may be manageable, but the costs to the health care system may compromise care in other ways. We conducted a literature review of the recommended therapies for AA based on American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to identify the costs of alopecia treatment and consolidate the available data for the practicing dermatologist.

Methods

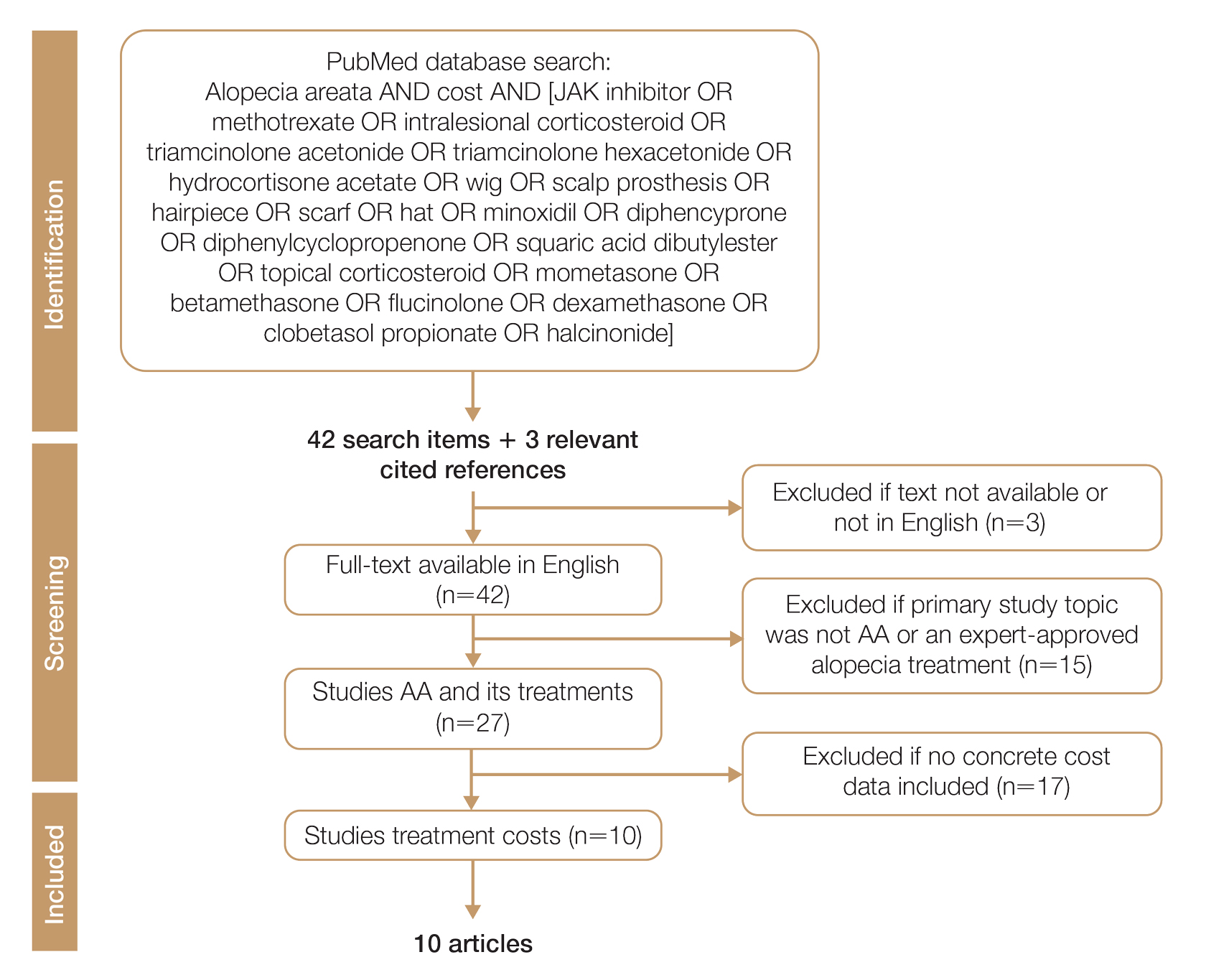

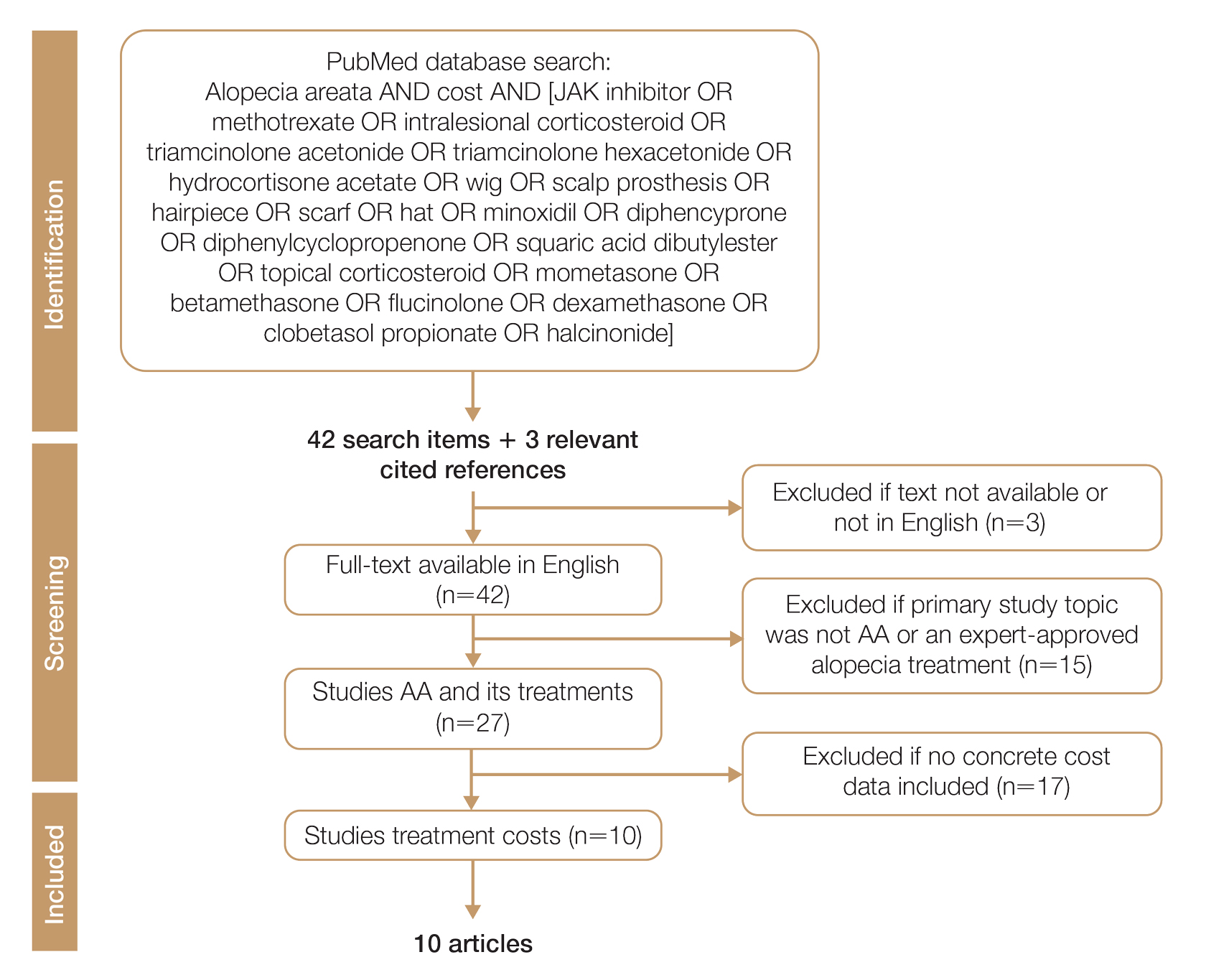

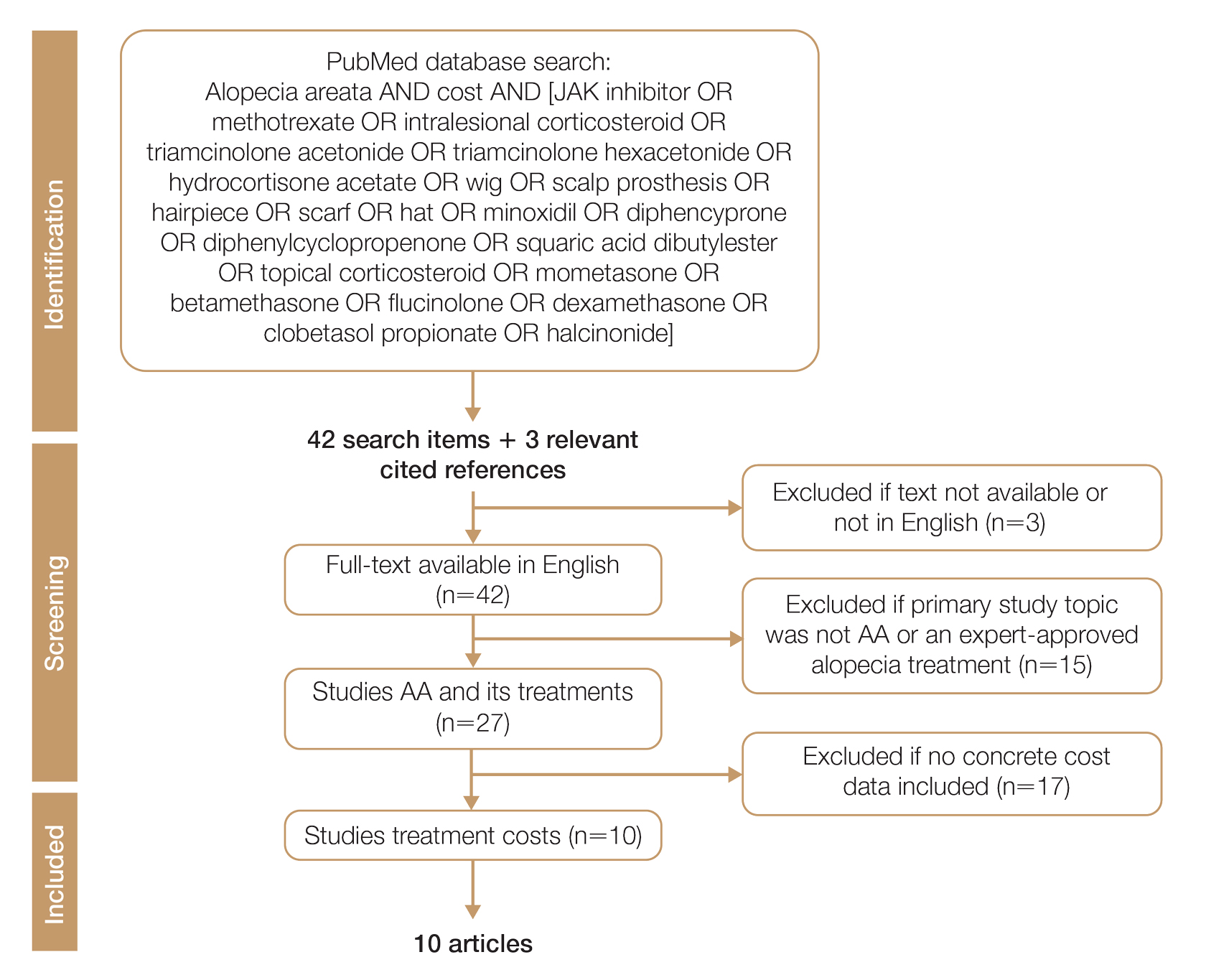

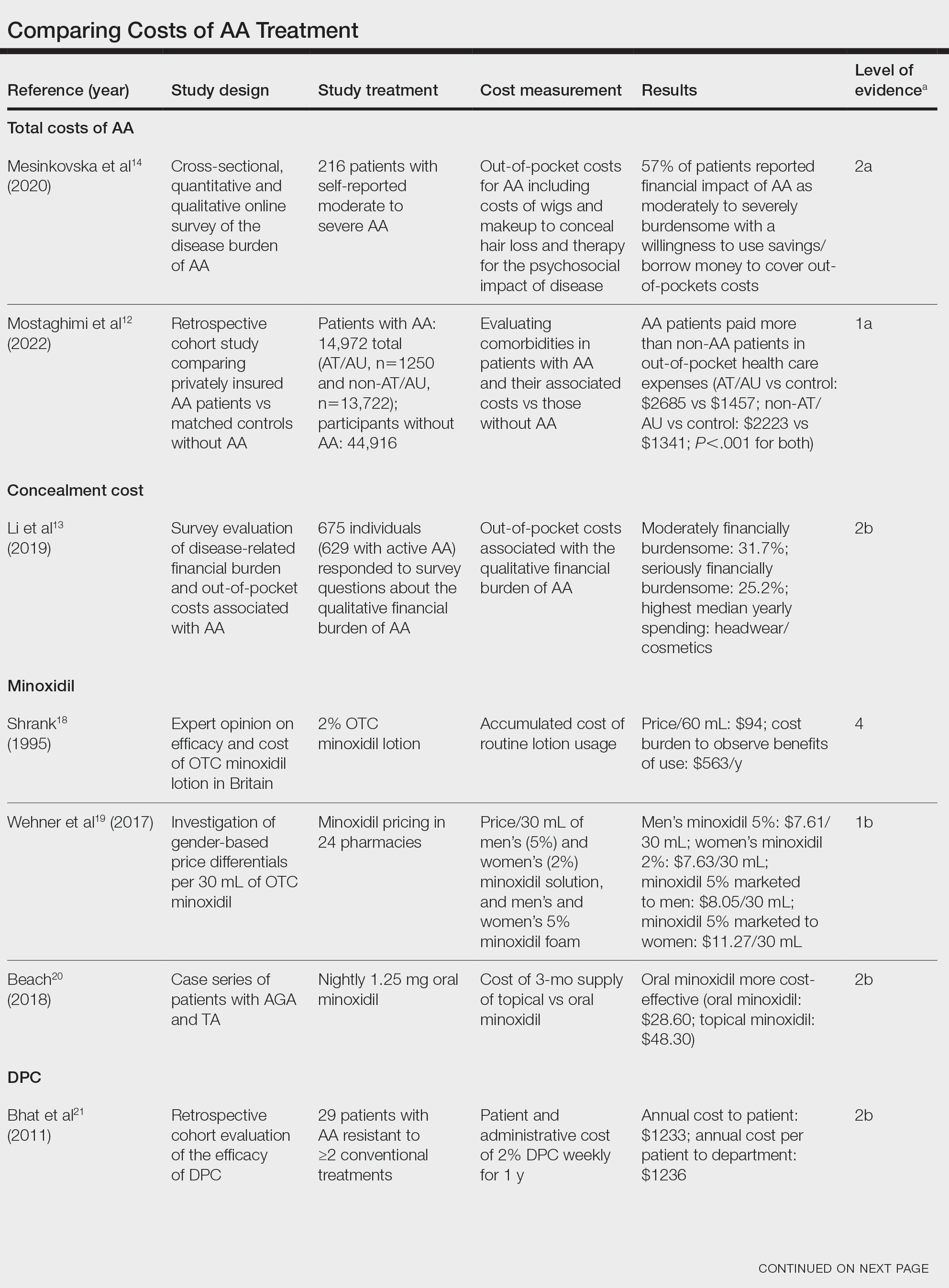

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE through September 15, 2022, using the terms alopecia and cost plus one of the treatments (n=21) identified by the AAD2 for the treatment of AA (Figure). The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies. Forty-five articles were identified.

Given the dearth of cost research in alopecia and the paucity of large prospective studies, we excluded articles that were not available in their full-text form or were not in English (n=3), articles whose primary study topic was not AA or an expert-approved alopecia treatment (n=15), and articles with no concrete cost data (n=17), which yielded 10 relevant articles that we studied using qualitative analysis.

Due to substantial differences in study methods and outcome measures, we did not compare the costs of alopecia among studies and did not perform statistical analysis. The quality of each study was investigated and assigned a level of evidence per the 2009 criteria from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.16

All cost data were converted into US dollars ($) using the conversion rate from the time of the original article’s publication.

Results

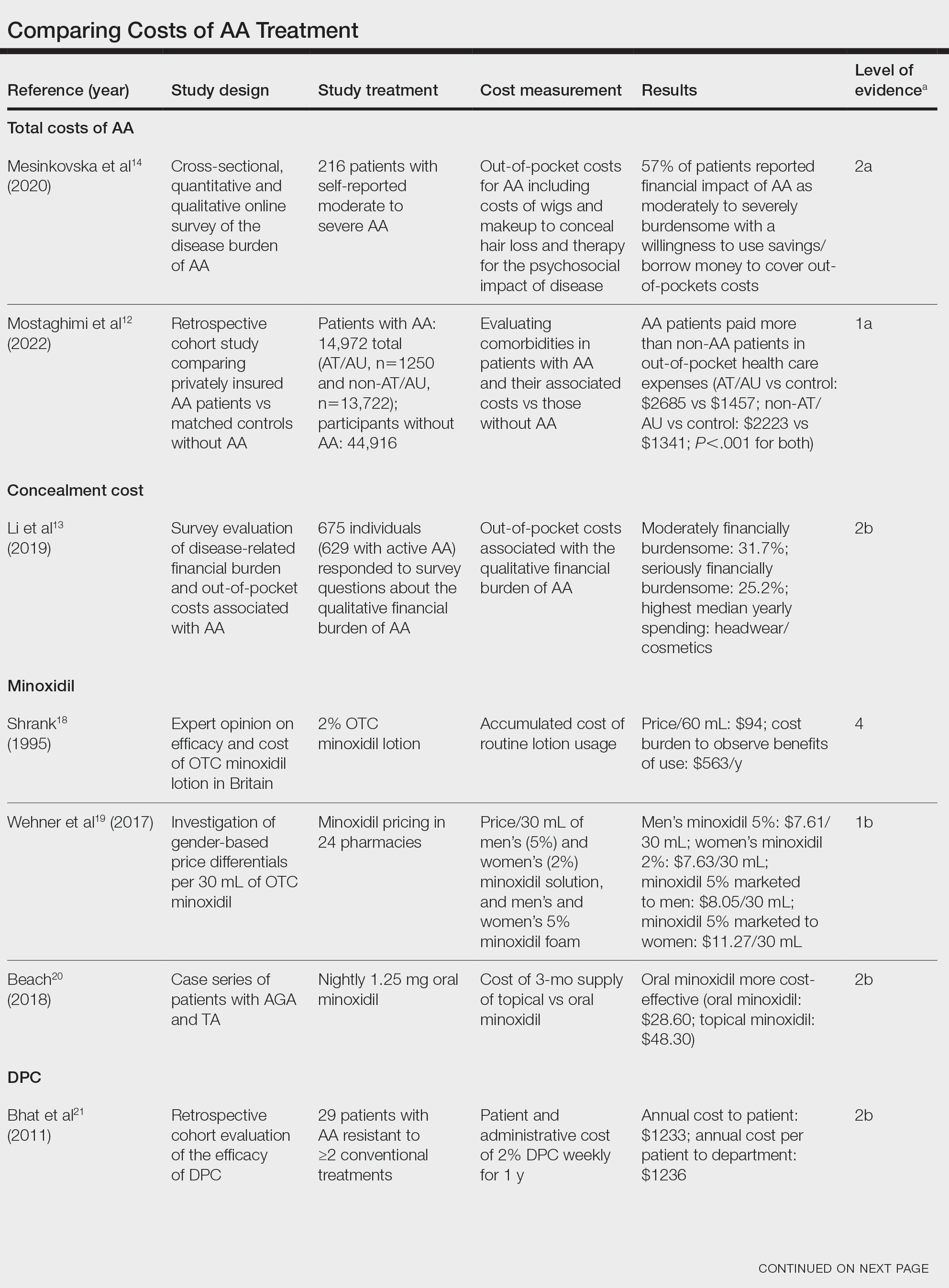

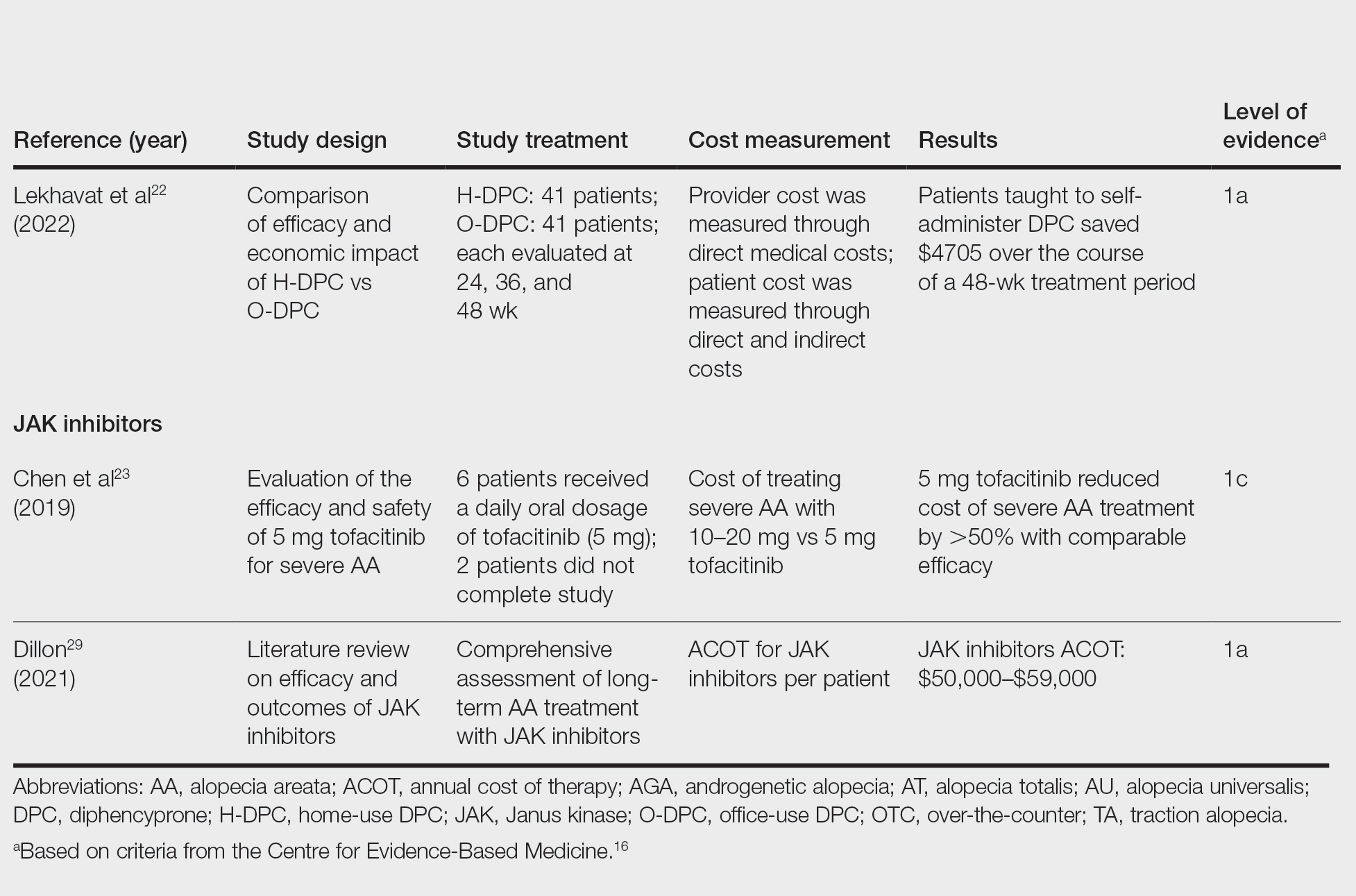

Total and Out-of-pocket Costs of AA—Li et al13 studied out-of-pocket health care costs for AA patients (N=675). Of these participants, 56.9% said their AA was moderately to seriously financially burdensome, and 41.3% reported using their savings to manage these expenses. Participants reported median out-of-pocket spending of $1354 (interquartile range, $537–$3300) annually. The most common categories of expenses were hair appointments (81.8%) and vitamins/supplements (67.7%).13

Mesinkovska et al14 studied the qualitative and quantitative financial burdens of moderate to severe AA (N=216). Fifty-seven percent of patients reported the financial impact of AA as moderately to severely burdensome with a willingness to borrow money or use savings to cover out-of-pocket costs. Patients without insurance cited cost as a major barrier to obtaining reatment. In addition to direct treatment-related expenses, AA patients spent a mean of $1961 per year on therapy to cope with the disease’s psychological burden. Lost work hours represented another source of financial burden; 61% of patients were employed, and 45% of them reported missing time from their job because of AA.14

Mostaghimi et al12 studied health care resource utilization and all-cause direct health care costs in privately insured AA patients with or without alopecia totalis (AT) or alopecia universalis (AU)(n=14,972) matched with non-AA controls (n=44,916)(1:3 ratio). Mean total all-cause medical and pharmacy costs were higher in both AA groups compared with controls (AT/AU, $18,988 vs $11,030; non-AT/AU, $13,686 vs $9336; P<.001 for both). Out-of-pocket costs were higher for AA vs controls (AT/AU, $2685 vs $1457; non-AT/AU, $2223 vs $1341; P<.001 for both). Medical costs in the AT/AU and non-AT/AU groups largely were driven by outpatient costs (AT/AU, $10,277 vs $5713; non-AT/AU, $8078 vs $4672; P<.001 for both).12

Costs of Concealment—When studying the out-of-pocket costs of AA (N=675), Li et al13 discovered that the median yearly spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items such as hats, wigs, and makeup ($450; interquartile range, $50–$1500). Mesinkovska et al14 reported that 49% of patients had insurance that covered AA treatment. However, 75% of patients reported that their insurance would not cover costs of concealment (eg, weave, wig, hair piece). Patients (N=112) spent a mean of $2211 per year and 10.3 hours per week on concealment.14

Minoxidil—Minoxidil solution is available over-the-counter, and its ease of access makes it a popular treatment for AA.17 Because manufacturers can sell directly to the public, minoxidil is marketed with bold claims and convincing packaging. Shrank18 noted that the product can take 4 months to work, meaning customers must incur a substantial cost burden before realizing the treatment’s benefit, which is not always obvious when purchasing minoxidil products, leaving customers—who were marketed a miracle drug—disappointed. Per Shrank,18 patients who did not experience hair regrowth after 4 months were advised to continue treatment for a year, leading them to spend hundreds of dollars for uncertain results. Those who did experience hair regrowth were advised to continue using the product twice daily 7 days per week indefinitely.18

Wehner et al19 studied the association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. The price that women paid for 2% regular-strength minoxidil solutions was similar to the price that men paid for 5% extra-strength minoxidil solutions (women’s 2%, $7.63/30 mL; men’s 5%, $7.61/30 mL; P=.67). Minoxidil 5% foams with identical ingredients were priced significantly more per volume of the same product when sold as a product directed at women vs a product directed at men (men’s 5%, $8.05/30 mL; women’s 5%, $11.27/30 mL; P<.001).19

Beach20 compared the cost of oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil. At $28.60 for a 3-month supply, oral minoxidil demonstrated cost savings compared to topical minoxidil ($48.30).20

Diphencyprone—Bhat et al21 studied the cost-efficiency of diphencyprone (DPC) in patients with AA resistant to at least 2 conventional treatments (N=29). After initial sensitization with 2% DPC, patients received weekly or fortnightly treatments. Most of the annual cost burden of DPC treatment was due to staff time and overhead rather than the cost of the DPC itself: $258 for the DPC, $978 in staff time and overhead for the department, and $1233 directly charged to the patient.21

Lekhavat et al22 studied the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC in extensive AA (N=82). Both groups received weekly treatments in the hospital until DPC concentrations had been adjusted. Afterward, the home group was given training on self-applying DPC at home. The home group had monthly office visits for DPC concentration evaluation and refills, while the office group had weekly appointments for DPC treatment at the hospital. Calculated costs included those to the health care provider (ie, material, labor, capital costs) and the patient’s final out-of-pocket expense. The total cost to the health care provider was higher for the office group than the home group at 48 weeks (office, $683.52; home, $303.67; P<.001). Median out-of-pocket costs did not vary significantly between groups, which may have been due to small sample size affecting the range (office, $418.07; home, $189.69; P=.101). There was no significant difference between groups in the proportion of patients who responded favorably to the DPC.22

JAK Inhibitors—Chen et al23 studied the efficacy of low-dose (5 mg) tofacitinib to treat severe AA (N=6). Compared to prior studies,24-27 this analysis reported the efficacy of low-dose tofacitinib was not inferior to higher doses (10–20 mg), and low-dose tofacitinib reduced treatment costs by more than 50%.23

Per the GlobalData Healthcare database, the estimated annual cost of therapy for JAK inhibitors following US Food and Drug Administration approval was $50,000. At the time of their reporting, the next most expensive immunomodulatory drug for AA was cyclosporine, with an annual cost of therapy of $1400.28 Dillon29 reviewed the use of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of AA. The cost estimates by Dillon29 prior to FDA approval aligned with the pricing of Eli Lilly and Company for the now-approved JAK inhibitor baricitinib.30 The list price of baricitinib is $2739.99 for a 30-day supply of 2-mg tablets or $5479.98 for a 30-day supply of 4-mg tablets. This amounts to $32,879.88 for an annual supply of 2-mg tablets and $65,759.76 for an annual supply for 4-mg tablets, though the out-of-pocket costs will vary.30

Comment

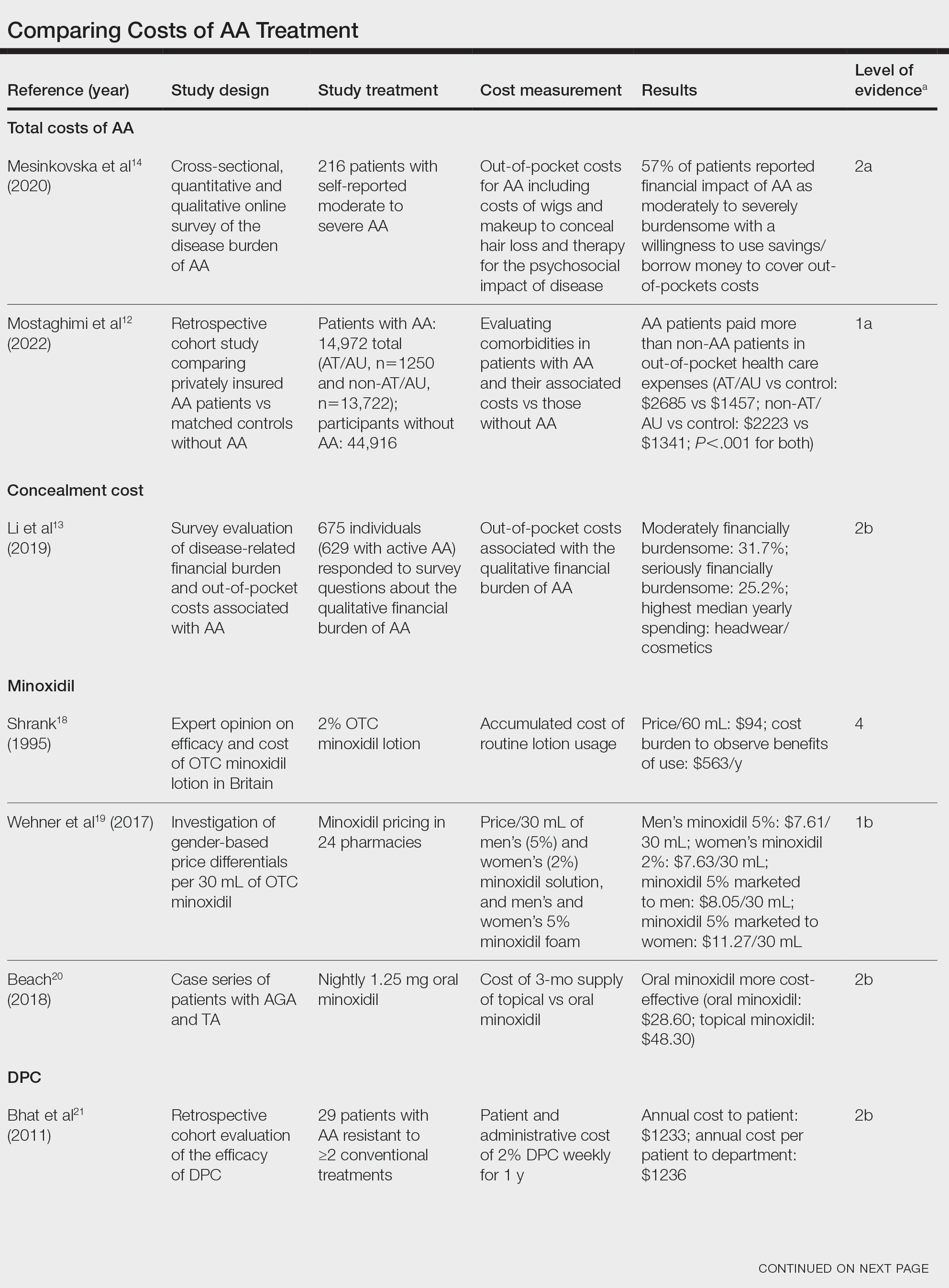

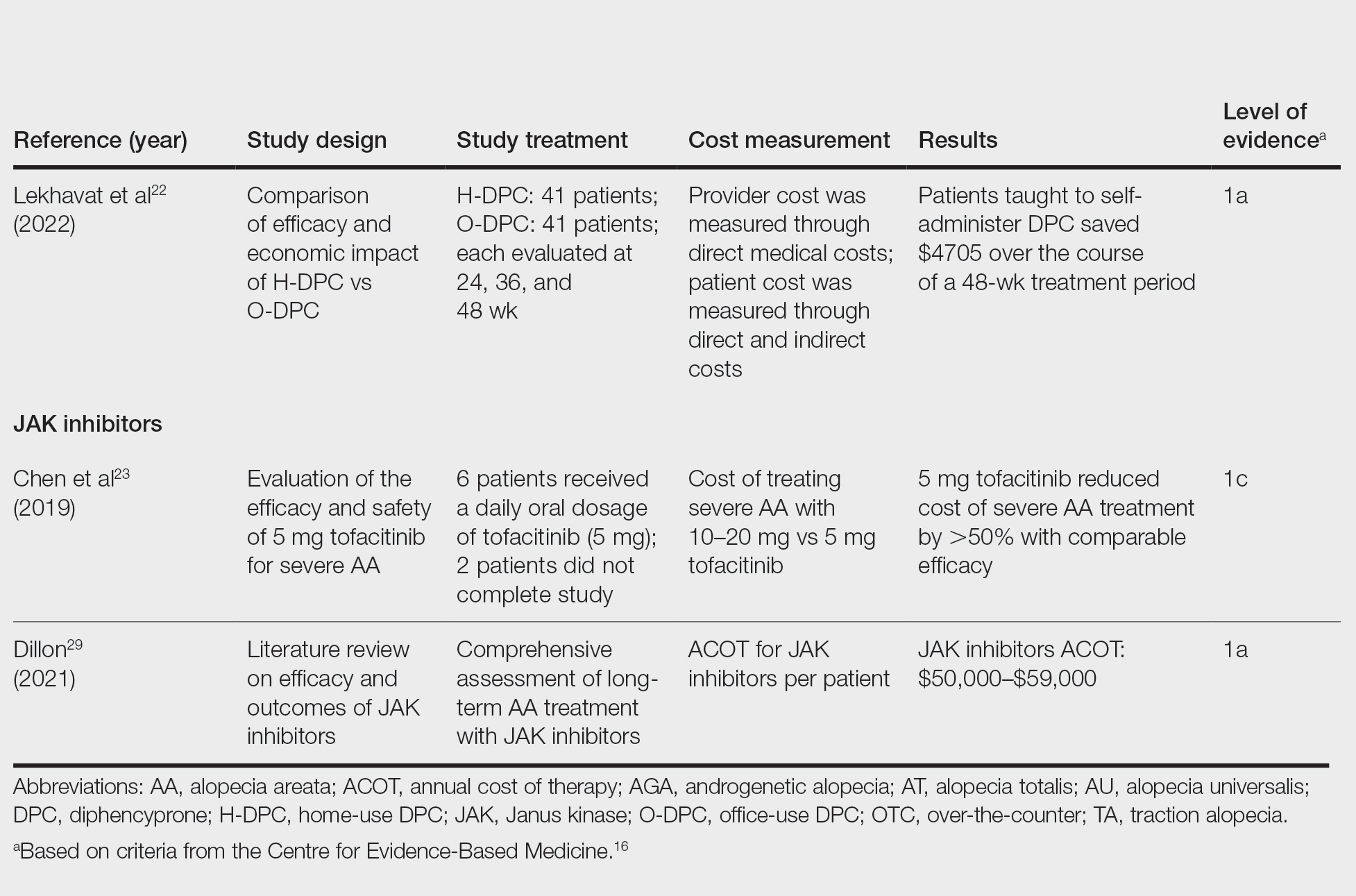

We reviewed the global and treatment-specific costs of AA, consolidating the available data for the practicing dermatologist. Ten studies of approximately 16,000 patients with AA across a range of levels of evidence (1a to 4) were included (Table). Three of 10 articles studied global costs of AA, 1 studied costs of concealment, 3 studied costs of minoxidil, 2 studied costs of DPC, and 2 studied costs of JAK inhibitors. Only 2 studies achieved level of evidence 1a: the first assessed the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC,22 and the second researched the efficacy and outcomes of JAK inhibitors.29

Hair-loss treatments and concealment techniques cost the average patient thousands of dollars. Spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items, which were rarely covered by insurance.13 Psychosocial sequelae further increased cost via therapy charges and lost time at work.14 Patients with AA had greater all-cause medical costs than those without AA, with most of the cost driven by outpatient visits. Patients with AA also paid nearly twice as much as non-AA patients on out-of-pocket health care expenses.14 Despite the high costs and limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients reported willingness to incur debt or use savings to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress.13

Minoxidil solution does not require physician office visits and is available over-the-counter.17 Despite identical ingredients, minoxidil is priced more per volume when marketed to women compared with men, which reflects the larger issue of gender-based pricing that does not exist for other AAD-approved alopecia therapies but may exist for cosmetic treatments and nonapproved therapies (eg, vitamins/supplements) that are popular in the treatment of AA.19 Oral minoxidil was more cost-effective than the topical form, and gender-based pricing was a nonissue.20 However, oral minoxidil requires a prescription, mandating patients incur the cost of an office visit. Patients should be wary of gender- or marketing-related surcharges for minoxidil solutions, and oral minoxidil may be a cost-effective choice.

Diphencyprone is a relatively affordable drug for AA, but the regular office visits traditionally required for its administration increase associated cost.21 Self-administration of DPC at home was more cost- and time-effective than in-office DPC administration and did not decrease efficacy. A regimen combining office visits for initial DPC titration, at-home DPC administration, and periodic office follow-up could minimize costs while preserving outcomes and safety.22

Janus kinase inhibitors are cutting-edge and expensive therapies for AA. The annual cost of these medications poses a tremendous burden on the payer (list price of annual supply ritlecitinib is $49,000),31 be that the patient or the insurance company. Low-dose tofacitinib may be similarly efficacious and could substantially reduce treatment costs.23 The true utility of these medications, specifically considering their steep costs, remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Alopecia areata poses a substantial and recurring cost burden on patients that is multifactorial including treatment, office visits, concealment, alternative therapies, psychosocial costs, and missed time at work. Although several treatment options exist, none of them are definitive. Oral minoxidil and at-home DPC administration can be cost-effective, though the cumulative cost is still high. The cost utility of JAK inhibitors remains unclear. When JAK inhibitors are prescribed, low-dose therapy may be used as maintenance to curb treatment costs. Concealment and therapy costs pose an additional, largely out-of-pocket financial burden. Despite the limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients incur substantial expenses to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress. There are no head-to-head studies comparing the cost-effectiveness of the different AA therapies; thus, it is unclear if one treatment is most efficacious. This topic remains an avenue for future investigation. Much of the cost burden of AA treatment falls directly on patients. Increasing coverage of AA-associated expenses, such as minoxidil therapy or wigs, could decrease the cost burden on patients. Providers also can inform patients about cost-saving tactics, such as purchasing minoxidil based on concentration and vehicle rather than marketing directed at men vs women. Finally, some patients may have insurance plans that at least partially cover the costs of wigs but may not be aware of this benefit. Querying a patient’s insurance provider can further minimize costs.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:96-98. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.423

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:15-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142

- Olsen EA, Carson SC, Turney EA. Systemic steroids with or without 2% topical minoxidil in the treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1467-1473.

- Levy LL, Urban J, King BA. Treatment of recalcitrant atopic dermatitis with the oral Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib citrate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:395-399. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.045

- Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145. doi:10.1111/bjd.12266

- Strober B, Buonanno M, Clark JD, et al. Effect of tofacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on haematological parameters during 12 weeks of psoriasis treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:992-999. doi:10.1111/bjd.12517

- van der Steen PH, van Baar HM, Happle R, et al. Prognostic factors in the treatment of alopecia areata with diphenylcyclopropenone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(2, pt 1):227-230. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70032-w

- Strazzulla LC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, et al. Image gallery: treatment of refractory alopecia universalis with oral tofacitinib citrate and adjunct intralesional triamcinolone injections. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:E125. doi:10.1111/bjd.15483

- Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549-566; quiz 567-570.

- Carnahan MC, Goldstein DA. Ocular complications of topical, peri-ocular, and systemic corticosteroids. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:478-483. doi:10.1097/00055735-200012000-00016

- Harel S, Higgins CA, Cerise JE, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling promotes hair growth. Sci Adv. 2015;1:E1500973. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500973

- Mostaghimi A, Gandhi K, Done N, et al. All-cause health care resource utilization and costs among adults with alopecia areata: a retrospective claims database study in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28:426-434. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.4.426

- Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, et al. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:493-494. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5218

- Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, et al. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20:S62-S68. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007

- Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44. doi:10.2147/rmhp.S19801

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009). University of Oxford website. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- Klifto KM, Othman S, Kovach SJ. Minoxidil, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), or combined minoxidil and PRP for androgenetic alopecia in men: a cost-effectiveness Markov decision analysis of prospective studies. Cureus. 2021;13:E20839. doi:10.7759/cureus.20839

- Shrank AB. Minoxidil over the counter. BMJ. 1995;311:526. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7004.526

- Wehner MR, Nead KT, Lipoff JB. Association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:825-826.

- Beach RA. Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: tolerability & the five C’s of oral therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12707. doi:10.1111/dth.12707

- Bhat A, Sripathy K, Wahie S, et al. Efficacy and cost-efficiency of diphencyprone for alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:43-44.

- Lekhavat C, Rattanaumpawan P, Juengsamranphong I. Economic impact of home-use versus office-use diphenylcyclopropenone in extensive alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:108-117.

- Chen YY, Lin SY, Chen YC, et al. Low-dose tofacitinib for treating patients with severe alopecia areata: an efficient and cost-saving regimen. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:667-669. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3668

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.007

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89776. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.89776

- Jabbari A, Sansaricq F, Cerise J, et al. An open-label pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of tofacitinib in moderate to severe patch-type alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1539-1545. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.032

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.006

- GlobalData Healthcare. Can JAK inhibitors penetrate the alopecia areata market effectively? Pharmaceutical Technology. July 15, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/analyst-comment/alopecia-areata-treatment-2019/

- Dillon KL. A comprehensive literature review of JAK inhibitors in treatment of alopecia areata. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:691-714. doi:10.2147/ccid.S309215

- How much should I expect to pay for Olumiant? Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.lillypricinginfo.com/olumiant

- McNamee A. FDA approves first-ever adolescent alopecia treatment from Pfizer. Pharmaceutical Technology. June 26, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/fda-approves-first-ever-adolescent-alopecia-treatment-from-pfizer/?cf-view

Alopecia areata (AA) affects 4.5 million individuals in the United States, with 66% younger than 30 years.1,2 Inflammation causes hair loss in well-circumscribed, nonscarring patches on the body with a predilection for the scalp.3-6 The disease can devastate a patient’s self-esteem, in turn reducing quality of life.1,7 Alopecia areata is an autoimmune T-cell–mediated disease in which hair follicles lose their immune privilege.8-10 Several specific mechanisms in the cytokine interactions between T cells and the hair follicle have been discovered, revealing the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway as pivotal in the pathogenesis of the disease and leading to the use of JAK inhibitors for treatment.11

There is no cure for AA, and the condition is managed with prolonged medical treatments and cosmetic therapies.2 Although some patients may be able to manage the annual cost, the cumulative cost of AA treatment can be burdensome.12 This cumulative cost may increase if newer, potentially expensive treatments become the standard of care. Patients with AA report dipping into their savings (41.3%) and cutting back on food or clothing expenses (33.9%) to account for the cost of alopecia treatment. Although prior estimates of the annual out-of-pocket cost of AA treatments range from $1354 to $2685, the cost burden of individual therapies is poorly understood.12-14

Patients who must juggle expensive medical bills with basic living expenses may be lost to follow-up or fall into treatment nonadherence.15 Other patients’ out-of-pocket costs may be manageable, but the costs to the health care system may compromise care in other ways. We conducted a literature review of the recommended therapies for AA based on American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to identify the costs of alopecia treatment and consolidate the available data for the practicing dermatologist.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE through September 15, 2022, using the terms alopecia and cost plus one of the treatments (n=21) identified by the AAD2 for the treatment of AA (Figure). The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies. Forty-five articles were identified.

Given the dearth of cost research in alopecia and the paucity of large prospective studies, we excluded articles that were not available in their full-text form or were not in English (n=3), articles whose primary study topic was not AA or an expert-approved alopecia treatment (n=15), and articles with no concrete cost data (n=17), which yielded 10 relevant articles that we studied using qualitative analysis.

Due to substantial differences in study methods and outcome measures, we did not compare the costs of alopecia among studies and did not perform statistical analysis. The quality of each study was investigated and assigned a level of evidence per the 2009 criteria from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.16

All cost data were converted into US dollars ($) using the conversion rate from the time of the original article’s publication.

Results

Total and Out-of-pocket Costs of AA—Li et al13 studied out-of-pocket health care costs for AA patients (N=675). Of these participants, 56.9% said their AA was moderately to seriously financially burdensome, and 41.3% reported using their savings to manage these expenses. Participants reported median out-of-pocket spending of $1354 (interquartile range, $537–$3300) annually. The most common categories of expenses were hair appointments (81.8%) and vitamins/supplements (67.7%).13

Mesinkovska et al14 studied the qualitative and quantitative financial burdens of moderate to severe AA (N=216). Fifty-seven percent of patients reported the financial impact of AA as moderately to severely burdensome with a willingness to borrow money or use savings to cover out-of-pocket costs. Patients without insurance cited cost as a major barrier to obtaining reatment. In addition to direct treatment-related expenses, AA patients spent a mean of $1961 per year on therapy to cope with the disease’s psychological burden. Lost work hours represented another source of financial burden; 61% of patients were employed, and 45% of them reported missing time from their job because of AA.14

Mostaghimi et al12 studied health care resource utilization and all-cause direct health care costs in privately insured AA patients with or without alopecia totalis (AT) or alopecia universalis (AU)(n=14,972) matched with non-AA controls (n=44,916)(1:3 ratio). Mean total all-cause medical and pharmacy costs were higher in both AA groups compared with controls (AT/AU, $18,988 vs $11,030; non-AT/AU, $13,686 vs $9336; P<.001 for both). Out-of-pocket costs were higher for AA vs controls (AT/AU, $2685 vs $1457; non-AT/AU, $2223 vs $1341; P<.001 for both). Medical costs in the AT/AU and non-AT/AU groups largely were driven by outpatient costs (AT/AU, $10,277 vs $5713; non-AT/AU, $8078 vs $4672; P<.001 for both).12

Costs of Concealment—When studying the out-of-pocket costs of AA (N=675), Li et al13 discovered that the median yearly spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items such as hats, wigs, and makeup ($450; interquartile range, $50–$1500). Mesinkovska et al14 reported that 49% of patients had insurance that covered AA treatment. However, 75% of patients reported that their insurance would not cover costs of concealment (eg, weave, wig, hair piece). Patients (N=112) spent a mean of $2211 per year and 10.3 hours per week on concealment.14

Minoxidil—Minoxidil solution is available over-the-counter, and its ease of access makes it a popular treatment for AA.17 Because manufacturers can sell directly to the public, minoxidil is marketed with bold claims and convincing packaging. Shrank18 noted that the product can take 4 months to work, meaning customers must incur a substantial cost burden before realizing the treatment’s benefit, which is not always obvious when purchasing minoxidil products, leaving customers—who were marketed a miracle drug—disappointed. Per Shrank,18 patients who did not experience hair regrowth after 4 months were advised to continue treatment for a year, leading them to spend hundreds of dollars for uncertain results. Those who did experience hair regrowth were advised to continue using the product twice daily 7 days per week indefinitely.18

Wehner et al19 studied the association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. The price that women paid for 2% regular-strength minoxidil solutions was similar to the price that men paid for 5% extra-strength minoxidil solutions (women’s 2%, $7.63/30 mL; men’s 5%, $7.61/30 mL; P=.67). Minoxidil 5% foams with identical ingredients were priced significantly more per volume of the same product when sold as a product directed at women vs a product directed at men (men’s 5%, $8.05/30 mL; women’s 5%, $11.27/30 mL; P<.001).19

Beach20 compared the cost of oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil. At $28.60 for a 3-month supply, oral minoxidil demonstrated cost savings compared to topical minoxidil ($48.30).20

Diphencyprone—Bhat et al21 studied the cost-efficiency of diphencyprone (DPC) in patients with AA resistant to at least 2 conventional treatments (N=29). After initial sensitization with 2% DPC, patients received weekly or fortnightly treatments. Most of the annual cost burden of DPC treatment was due to staff time and overhead rather than the cost of the DPC itself: $258 for the DPC, $978 in staff time and overhead for the department, and $1233 directly charged to the patient.21

Lekhavat et al22 studied the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC in extensive AA (N=82). Both groups received weekly treatments in the hospital until DPC concentrations had been adjusted. Afterward, the home group was given training on self-applying DPC at home. The home group had monthly office visits for DPC concentration evaluation and refills, while the office group had weekly appointments for DPC treatment at the hospital. Calculated costs included those to the health care provider (ie, material, labor, capital costs) and the patient’s final out-of-pocket expense. The total cost to the health care provider was higher for the office group than the home group at 48 weeks (office, $683.52; home, $303.67; P<.001). Median out-of-pocket costs did not vary significantly between groups, which may have been due to small sample size affecting the range (office, $418.07; home, $189.69; P=.101). There was no significant difference between groups in the proportion of patients who responded favorably to the DPC.22

JAK Inhibitors—Chen et al23 studied the efficacy of low-dose (5 mg) tofacitinib to treat severe AA (N=6). Compared to prior studies,24-27 this analysis reported the efficacy of low-dose tofacitinib was not inferior to higher doses (10–20 mg), and low-dose tofacitinib reduced treatment costs by more than 50%.23

Per the GlobalData Healthcare database, the estimated annual cost of therapy for JAK inhibitors following US Food and Drug Administration approval was $50,000. At the time of their reporting, the next most expensive immunomodulatory drug for AA was cyclosporine, with an annual cost of therapy of $1400.28 Dillon29 reviewed the use of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of AA. The cost estimates by Dillon29 prior to FDA approval aligned with the pricing of Eli Lilly and Company for the now-approved JAK inhibitor baricitinib.30 The list price of baricitinib is $2739.99 for a 30-day supply of 2-mg tablets or $5479.98 for a 30-day supply of 4-mg tablets. This amounts to $32,879.88 for an annual supply of 2-mg tablets and $65,759.76 for an annual supply for 4-mg tablets, though the out-of-pocket costs will vary.30

Comment

We reviewed the global and treatment-specific costs of AA, consolidating the available data for the practicing dermatologist. Ten studies of approximately 16,000 patients with AA across a range of levels of evidence (1a to 4) were included (Table). Three of 10 articles studied global costs of AA, 1 studied costs of concealment, 3 studied costs of minoxidil, 2 studied costs of DPC, and 2 studied costs of JAK inhibitors. Only 2 studies achieved level of evidence 1a: the first assessed the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC,22 and the second researched the efficacy and outcomes of JAK inhibitors.29

Hair-loss treatments and concealment techniques cost the average patient thousands of dollars. Spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items, which were rarely covered by insurance.13 Psychosocial sequelae further increased cost via therapy charges and lost time at work.14 Patients with AA had greater all-cause medical costs than those without AA, with most of the cost driven by outpatient visits. Patients with AA also paid nearly twice as much as non-AA patients on out-of-pocket health care expenses.14 Despite the high costs and limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients reported willingness to incur debt or use savings to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress.13

Minoxidil solution does not require physician office visits and is available over-the-counter.17 Despite identical ingredients, minoxidil is priced more per volume when marketed to women compared with men, which reflects the larger issue of gender-based pricing that does not exist for other AAD-approved alopecia therapies but may exist for cosmetic treatments and nonapproved therapies (eg, vitamins/supplements) that are popular in the treatment of AA.19 Oral minoxidil was more cost-effective than the topical form, and gender-based pricing was a nonissue.20 However, oral minoxidil requires a prescription, mandating patients incur the cost of an office visit. Patients should be wary of gender- or marketing-related surcharges for minoxidil solutions, and oral minoxidil may be a cost-effective choice.

Diphencyprone is a relatively affordable drug for AA, but the regular office visits traditionally required for its administration increase associated cost.21 Self-administration of DPC at home was more cost- and time-effective than in-office DPC administration and did not decrease efficacy. A regimen combining office visits for initial DPC titration, at-home DPC administration, and periodic office follow-up could minimize costs while preserving outcomes and safety.22

Janus kinase inhibitors are cutting-edge and expensive therapies for AA. The annual cost of these medications poses a tremendous burden on the payer (list price of annual supply ritlecitinib is $49,000),31 be that the patient or the insurance company. Low-dose tofacitinib may be similarly efficacious and could substantially reduce treatment costs.23 The true utility of these medications, specifically considering their steep costs, remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Alopecia areata poses a substantial and recurring cost burden on patients that is multifactorial including treatment, office visits, concealment, alternative therapies, psychosocial costs, and missed time at work. Although several treatment options exist, none of them are definitive. Oral minoxidil and at-home DPC administration can be cost-effective, though the cumulative cost is still high. The cost utility of JAK inhibitors remains unclear. When JAK inhibitors are prescribed, low-dose therapy may be used as maintenance to curb treatment costs. Concealment and therapy costs pose an additional, largely out-of-pocket financial burden. Despite the limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients incur substantial expenses to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress. There are no head-to-head studies comparing the cost-effectiveness of the different AA therapies; thus, it is unclear if one treatment is most efficacious. This topic remains an avenue for future investigation. Much of the cost burden of AA treatment falls directly on patients. Increasing coverage of AA-associated expenses, such as minoxidil therapy or wigs, could decrease the cost burden on patients. Providers also can inform patients about cost-saving tactics, such as purchasing minoxidil based on concentration and vehicle rather than marketing directed at men vs women. Finally, some patients may have insurance plans that at least partially cover the costs of wigs but may not be aware of this benefit. Querying a patient’s insurance provider can further minimize costs.

Alopecia areata (AA) affects 4.5 million individuals in the United States, with 66% younger than 30 years.1,2 Inflammation causes hair loss in well-circumscribed, nonscarring patches on the body with a predilection for the scalp.3-6 The disease can devastate a patient’s self-esteem, in turn reducing quality of life.1,7 Alopecia areata is an autoimmune T-cell–mediated disease in which hair follicles lose their immune privilege.8-10 Several specific mechanisms in the cytokine interactions between T cells and the hair follicle have been discovered, revealing the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway as pivotal in the pathogenesis of the disease and leading to the use of JAK inhibitors for treatment.11

There is no cure for AA, and the condition is managed with prolonged medical treatments and cosmetic therapies.2 Although some patients may be able to manage the annual cost, the cumulative cost of AA treatment can be burdensome.12 This cumulative cost may increase if newer, potentially expensive treatments become the standard of care. Patients with AA report dipping into their savings (41.3%) and cutting back on food or clothing expenses (33.9%) to account for the cost of alopecia treatment. Although prior estimates of the annual out-of-pocket cost of AA treatments range from $1354 to $2685, the cost burden of individual therapies is poorly understood.12-14

Patients who must juggle expensive medical bills with basic living expenses may be lost to follow-up or fall into treatment nonadherence.15 Other patients’ out-of-pocket costs may be manageable, but the costs to the health care system may compromise care in other ways. We conducted a literature review of the recommended therapies for AA based on American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to identify the costs of alopecia treatment and consolidate the available data for the practicing dermatologist.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE through September 15, 2022, using the terms alopecia and cost plus one of the treatments (n=21) identified by the AAD2 for the treatment of AA (Figure). The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies. Forty-five articles were identified.

Given the dearth of cost research in alopecia and the paucity of large prospective studies, we excluded articles that were not available in their full-text form or were not in English (n=3), articles whose primary study topic was not AA or an expert-approved alopecia treatment (n=15), and articles with no concrete cost data (n=17), which yielded 10 relevant articles that we studied using qualitative analysis.

Due to substantial differences in study methods and outcome measures, we did not compare the costs of alopecia among studies and did not perform statistical analysis. The quality of each study was investigated and assigned a level of evidence per the 2009 criteria from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.16

All cost data were converted into US dollars ($) using the conversion rate from the time of the original article’s publication.

Results

Total and Out-of-pocket Costs of AA—Li et al13 studied out-of-pocket health care costs for AA patients (N=675). Of these participants, 56.9% said their AA was moderately to seriously financially burdensome, and 41.3% reported using their savings to manage these expenses. Participants reported median out-of-pocket spending of $1354 (interquartile range, $537–$3300) annually. The most common categories of expenses were hair appointments (81.8%) and vitamins/supplements (67.7%).13

Mesinkovska et al14 studied the qualitative and quantitative financial burdens of moderate to severe AA (N=216). Fifty-seven percent of patients reported the financial impact of AA as moderately to severely burdensome with a willingness to borrow money or use savings to cover out-of-pocket costs. Patients without insurance cited cost as a major barrier to obtaining reatment. In addition to direct treatment-related expenses, AA patients spent a mean of $1961 per year on therapy to cope with the disease’s psychological burden. Lost work hours represented another source of financial burden; 61% of patients were employed, and 45% of them reported missing time from their job because of AA.14

Mostaghimi et al12 studied health care resource utilization and all-cause direct health care costs in privately insured AA patients with or without alopecia totalis (AT) or alopecia universalis (AU)(n=14,972) matched with non-AA controls (n=44,916)(1:3 ratio). Mean total all-cause medical and pharmacy costs were higher in both AA groups compared with controls (AT/AU, $18,988 vs $11,030; non-AT/AU, $13,686 vs $9336; P<.001 for both). Out-of-pocket costs were higher for AA vs controls (AT/AU, $2685 vs $1457; non-AT/AU, $2223 vs $1341; P<.001 for both). Medical costs in the AT/AU and non-AT/AU groups largely were driven by outpatient costs (AT/AU, $10,277 vs $5713; non-AT/AU, $8078 vs $4672; P<.001 for both).12

Costs of Concealment—When studying the out-of-pocket costs of AA (N=675), Li et al13 discovered that the median yearly spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items such as hats, wigs, and makeup ($450; interquartile range, $50–$1500). Mesinkovska et al14 reported that 49% of patients had insurance that covered AA treatment. However, 75% of patients reported that their insurance would not cover costs of concealment (eg, weave, wig, hair piece). Patients (N=112) spent a mean of $2211 per year and 10.3 hours per week on concealment.14

Minoxidil—Minoxidil solution is available over-the-counter, and its ease of access makes it a popular treatment for AA.17 Because manufacturers can sell directly to the public, minoxidil is marketed with bold claims and convincing packaging. Shrank18 noted that the product can take 4 months to work, meaning customers must incur a substantial cost burden before realizing the treatment’s benefit, which is not always obvious when purchasing minoxidil products, leaving customers—who were marketed a miracle drug—disappointed. Per Shrank,18 patients who did not experience hair regrowth after 4 months were advised to continue treatment for a year, leading them to spend hundreds of dollars for uncertain results. Those who did experience hair regrowth were advised to continue using the product twice daily 7 days per week indefinitely.18

Wehner et al19 studied the association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. The price that women paid for 2% regular-strength minoxidil solutions was similar to the price that men paid for 5% extra-strength minoxidil solutions (women’s 2%, $7.63/30 mL; men’s 5%, $7.61/30 mL; P=.67). Minoxidil 5% foams with identical ingredients were priced significantly more per volume of the same product when sold as a product directed at women vs a product directed at men (men’s 5%, $8.05/30 mL; women’s 5%, $11.27/30 mL; P<.001).19

Beach20 compared the cost of oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil. At $28.60 for a 3-month supply, oral minoxidil demonstrated cost savings compared to topical minoxidil ($48.30).20

Diphencyprone—Bhat et al21 studied the cost-efficiency of diphencyprone (DPC) in patients with AA resistant to at least 2 conventional treatments (N=29). After initial sensitization with 2% DPC, patients received weekly or fortnightly treatments. Most of the annual cost burden of DPC treatment was due to staff time and overhead rather than the cost of the DPC itself: $258 for the DPC, $978 in staff time and overhead for the department, and $1233 directly charged to the patient.21

Lekhavat et al22 studied the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC in extensive AA (N=82). Both groups received weekly treatments in the hospital until DPC concentrations had been adjusted. Afterward, the home group was given training on self-applying DPC at home. The home group had monthly office visits for DPC concentration evaluation and refills, while the office group had weekly appointments for DPC treatment at the hospital. Calculated costs included those to the health care provider (ie, material, labor, capital costs) and the patient’s final out-of-pocket expense. The total cost to the health care provider was higher for the office group than the home group at 48 weeks (office, $683.52; home, $303.67; P<.001). Median out-of-pocket costs did not vary significantly between groups, which may have been due to small sample size affecting the range (office, $418.07; home, $189.69; P=.101). There was no significant difference between groups in the proportion of patients who responded favorably to the DPC.22

JAK Inhibitors—Chen et al23 studied the efficacy of low-dose (5 mg) tofacitinib to treat severe AA (N=6). Compared to prior studies,24-27 this analysis reported the efficacy of low-dose tofacitinib was not inferior to higher doses (10–20 mg), and low-dose tofacitinib reduced treatment costs by more than 50%.23

Per the GlobalData Healthcare database, the estimated annual cost of therapy for JAK inhibitors following US Food and Drug Administration approval was $50,000. At the time of their reporting, the next most expensive immunomodulatory drug for AA was cyclosporine, with an annual cost of therapy of $1400.28 Dillon29 reviewed the use of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of AA. The cost estimates by Dillon29 prior to FDA approval aligned with the pricing of Eli Lilly and Company for the now-approved JAK inhibitor baricitinib.30 The list price of baricitinib is $2739.99 for a 30-day supply of 2-mg tablets or $5479.98 for a 30-day supply of 4-mg tablets. This amounts to $32,879.88 for an annual supply of 2-mg tablets and $65,759.76 for an annual supply for 4-mg tablets, though the out-of-pocket costs will vary.30

Comment

We reviewed the global and treatment-specific costs of AA, consolidating the available data for the practicing dermatologist. Ten studies of approximately 16,000 patients with AA across a range of levels of evidence (1a to 4) were included (Table). Three of 10 articles studied global costs of AA, 1 studied costs of concealment, 3 studied costs of minoxidil, 2 studied costs of DPC, and 2 studied costs of JAK inhibitors. Only 2 studies achieved level of evidence 1a: the first assessed the economic impact of home-use vs office-use DPC,22 and the second researched the efficacy and outcomes of JAK inhibitors.29

Hair-loss treatments and concealment techniques cost the average patient thousands of dollars. Spending was highest on headwear or cosmetic items, which were rarely covered by insurance.13 Psychosocial sequelae further increased cost via therapy charges and lost time at work.14 Patients with AA had greater all-cause medical costs than those without AA, with most of the cost driven by outpatient visits. Patients with AA also paid nearly twice as much as non-AA patients on out-of-pocket health care expenses.14 Despite the high costs and limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients reported willingness to incur debt or use savings to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress.13

Minoxidil solution does not require physician office visits and is available over-the-counter.17 Despite identical ingredients, minoxidil is priced more per volume when marketed to women compared with men, which reflects the larger issue of gender-based pricing that does not exist for other AAD-approved alopecia therapies but may exist for cosmetic treatments and nonapproved therapies (eg, vitamins/supplements) that are popular in the treatment of AA.19 Oral minoxidil was more cost-effective than the topical form, and gender-based pricing was a nonissue.20 However, oral minoxidil requires a prescription, mandating patients incur the cost of an office visit. Patients should be wary of gender- or marketing-related surcharges for minoxidil solutions, and oral minoxidil may be a cost-effective choice.

Diphencyprone is a relatively affordable drug for AA, but the regular office visits traditionally required for its administration increase associated cost.21 Self-administration of DPC at home was more cost- and time-effective than in-office DPC administration and did not decrease efficacy. A regimen combining office visits for initial DPC titration, at-home DPC administration, and periodic office follow-up could minimize costs while preserving outcomes and safety.22

Janus kinase inhibitors are cutting-edge and expensive therapies for AA. The annual cost of these medications poses a tremendous burden on the payer (list price of annual supply ritlecitinib is $49,000),31 be that the patient or the insurance company. Low-dose tofacitinib may be similarly efficacious and could substantially reduce treatment costs.23 The true utility of these medications, specifically considering their steep costs, remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Alopecia areata poses a substantial and recurring cost burden on patients that is multifactorial including treatment, office visits, concealment, alternative therapies, psychosocial costs, and missed time at work. Although several treatment options exist, none of them are definitive. Oral minoxidil and at-home DPC administration can be cost-effective, though the cumulative cost is still high. The cost utility of JAK inhibitors remains unclear. When JAK inhibitors are prescribed, low-dose therapy may be used as maintenance to curb treatment costs. Concealment and therapy costs pose an additional, largely out-of-pocket financial burden. Despite the limited efficacy of many AA therapies, patients incur substantial expenses to manage their AA. This willingness to pay reflects AA’s impact on quality of life and puts these patients at high risk for financial distress. There are no head-to-head studies comparing the cost-effectiveness of the different AA therapies; thus, it is unclear if one treatment is most efficacious. This topic remains an avenue for future investigation. Much of the cost burden of AA treatment falls directly on patients. Increasing coverage of AA-associated expenses, such as minoxidil therapy or wigs, could decrease the cost burden on patients. Providers also can inform patients about cost-saving tactics, such as purchasing minoxidil based on concentration and vehicle rather than marketing directed at men vs women. Finally, some patients may have insurance plans that at least partially cover the costs of wigs but may not be aware of this benefit. Querying a patient’s insurance provider can further minimize costs.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:96-98. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.423

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:15-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142

- Olsen EA, Carson SC, Turney EA. Systemic steroids with or without 2% topical minoxidil in the treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1467-1473.

- Levy LL, Urban J, King BA. Treatment of recalcitrant atopic dermatitis with the oral Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib citrate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:395-399. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.045

- Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145. doi:10.1111/bjd.12266

- Strober B, Buonanno M, Clark JD, et al. Effect of tofacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on haematological parameters during 12 weeks of psoriasis treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:992-999. doi:10.1111/bjd.12517

- van der Steen PH, van Baar HM, Happle R, et al. Prognostic factors in the treatment of alopecia areata with diphenylcyclopropenone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(2, pt 1):227-230. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70032-w

- Strazzulla LC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, et al. Image gallery: treatment of refractory alopecia universalis with oral tofacitinib citrate and adjunct intralesional triamcinolone injections. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:E125. doi:10.1111/bjd.15483

- Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549-566; quiz 567-570.

- Carnahan MC, Goldstein DA. Ocular complications of topical, peri-ocular, and systemic corticosteroids. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:478-483. doi:10.1097/00055735-200012000-00016

- Harel S, Higgins CA, Cerise JE, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling promotes hair growth. Sci Adv. 2015;1:E1500973. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500973

- Mostaghimi A, Gandhi K, Done N, et al. All-cause health care resource utilization and costs among adults with alopecia areata: a retrospective claims database study in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28:426-434. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.4.426

- Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, et al. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:493-494. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5218

- Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, et al. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20:S62-S68. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007

- Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44. doi:10.2147/rmhp.S19801

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009). University of Oxford website. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- Klifto KM, Othman S, Kovach SJ. Minoxidil, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), or combined minoxidil and PRP for androgenetic alopecia in men: a cost-effectiveness Markov decision analysis of prospective studies. Cureus. 2021;13:E20839. doi:10.7759/cureus.20839

- Shrank AB. Minoxidil over the counter. BMJ. 1995;311:526. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7004.526

- Wehner MR, Nead KT, Lipoff JB. Association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:825-826.

- Beach RA. Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: tolerability & the five C’s of oral therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12707. doi:10.1111/dth.12707

- Bhat A, Sripathy K, Wahie S, et al. Efficacy and cost-efficiency of diphencyprone for alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:43-44.

- Lekhavat C, Rattanaumpawan P, Juengsamranphong I. Economic impact of home-use versus office-use diphenylcyclopropenone in extensive alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:108-117.

- Chen YY, Lin SY, Chen YC, et al. Low-dose tofacitinib for treating patients with severe alopecia areata: an efficient and cost-saving regimen. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:667-669. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3668

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.007

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89776. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.89776

- Jabbari A, Sansaricq F, Cerise J, et al. An open-label pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of tofacitinib in moderate to severe patch-type alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1539-1545. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.032

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.006

- GlobalData Healthcare. Can JAK inhibitors penetrate the alopecia areata market effectively? Pharmaceutical Technology. July 15, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/analyst-comment/alopecia-areata-treatment-2019/

- Dillon KL. A comprehensive literature review of JAK inhibitors in treatment of alopecia areata. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:691-714. doi:10.2147/ccid.S309215

- How much should I expect to pay for Olumiant? Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.lillypricinginfo.com/olumiant

- McNamee A. FDA approves first-ever adolescent alopecia treatment from Pfizer. Pharmaceutical Technology. June 26, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/fda-approves-first-ever-adolescent-alopecia-treatment-from-pfizer/?cf-view

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Pazzaglia M, et al. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% under occlusion in the treatment of alopecia totalis/universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:96-98. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.423

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:15-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142

- Olsen EA, Carson SC, Turney EA. Systemic steroids with or without 2% topical minoxidil in the treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1467-1473.

- Levy LL, Urban J, King BA. Treatment of recalcitrant atopic dermatitis with the oral Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib citrate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:395-399. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.045

- Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137-145. doi:10.1111/bjd.12266

- Strober B, Buonanno M, Clark JD, et al. Effect of tofacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, on haematological parameters during 12 weeks of psoriasis treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:992-999. doi:10.1111/bjd.12517

- van der Steen PH, van Baar HM, Happle R, et al. Prognostic factors in the treatment of alopecia areata with diphenylcyclopropenone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(2, pt 1):227-230. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70032-w

- Strazzulla LC, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, et al. Image gallery: treatment of refractory alopecia universalis with oral tofacitinib citrate and adjunct intralesional triamcinolone injections. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:E125. doi:10.1111/bjd.15483

- Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549-566; quiz 567-570.

- Carnahan MC, Goldstein DA. Ocular complications of topical, peri-ocular, and systemic corticosteroids. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:478-483. doi:10.1097/00055735-200012000-00016

- Harel S, Higgins CA, Cerise JE, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling promotes hair growth. Sci Adv. 2015;1:E1500973. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500973

- Mostaghimi A, Gandhi K, Done N, et al. All-cause health care resource utilization and costs among adults with alopecia areata: a retrospective claims database study in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28:426-434. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.4.426

- Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, et al. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:493-494. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5218

- Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, et al. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20:S62-S68. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007

- Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:35-44. doi:10.2147/rmhp.S19801

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009). University of Oxford website. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- Klifto KM, Othman S, Kovach SJ. Minoxidil, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), or combined minoxidil and PRP for androgenetic alopecia in men: a cost-effectiveness Markov decision analysis of prospective studies. Cureus. 2021;13:E20839. doi:10.7759/cureus.20839

- Shrank AB. Minoxidil over the counter. BMJ. 1995;311:526. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7004.526

- Wehner MR, Nead KT, Lipoff JB. Association between gender and drug cost for over-the-counter minoxidil. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:825-826.

- Beach RA. Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: tolerability & the five C’s of oral therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12707. doi:10.1111/dth.12707

- Bhat A, Sripathy K, Wahie S, et al. Efficacy and cost-efficiency of diphencyprone for alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:43-44.

- Lekhavat C, Rattanaumpawan P, Juengsamranphong I. Economic impact of home-use versus office-use diphenylcyclopropenone in extensive alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:108-117.

- Chen YY, Lin SY, Chen YC, et al. Low-dose tofacitinib for treating patients with severe alopecia areata: an efficient and cost-saving regimen. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:667-669. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3668

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.007

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89776. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.89776

- Jabbari A, Sansaricq F, Cerise J, et al. An open-label pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of tofacitinib in moderate to severe patch-type alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1539-1545. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.032

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.006

- GlobalData Healthcare. Can JAK inhibitors penetrate the alopecia areata market effectively? Pharmaceutical Technology. July 15, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/analyst-comment/alopecia-areata-treatment-2019/

- Dillon KL. A comprehensive literature review of JAK inhibitors in treatment of alopecia areata. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:691-714. doi:10.2147/ccid.S309215

- How much should I expect to pay for Olumiant? Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.lillypricinginfo.com/olumiant

- McNamee A. FDA approves first-ever adolescent alopecia treatment from Pfizer. Pharmaceutical Technology. June 26, 2023. Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/fda-approves-first-ever-adolescent-alopecia-treatment-from-pfizer/?cf-view

Practice Points

- Hair loss treatments and concealment techniques cost the average patient thousands of dollars. Much of this cost burden comes from items not covered by insurance.

- Providers should be wary of gender- or marketing-related surcharges for minoxidil solutions, and oral minoxidil may be a cost-effective option.

- Self-administering diphencyprone at home is more cost- and time-effective than in-office diphencyprone administration and does not decrease efficacy.

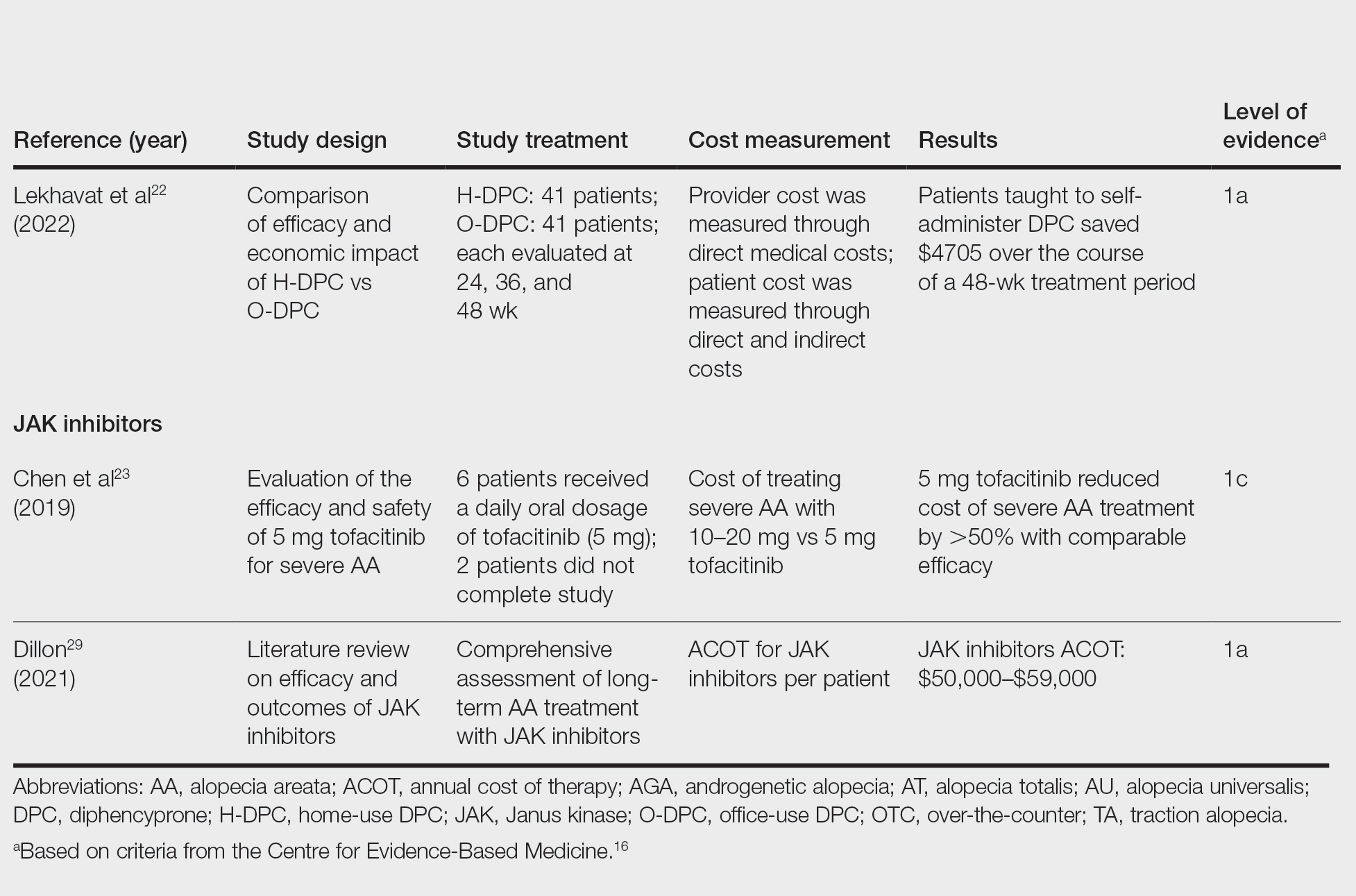

New Razor Technology Improves Appearance and Quality of Life in Men With Pseudofolliculitis Barbae

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB)(also known as razor bumps or shaving bumps)1 is a skin condition that consists of papules resulting from ingrown hairs.2 In more severe cases, papules become pustules, then abscesses, which can cause scarring.1,2 The condition can be distressing for patients, with considerable negative impact on their daily lives.3 The condition also is associated with shaving-related stinging, burning, pruritus, and cuts on the skin.4