User login

Erythematous Plaques on a Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

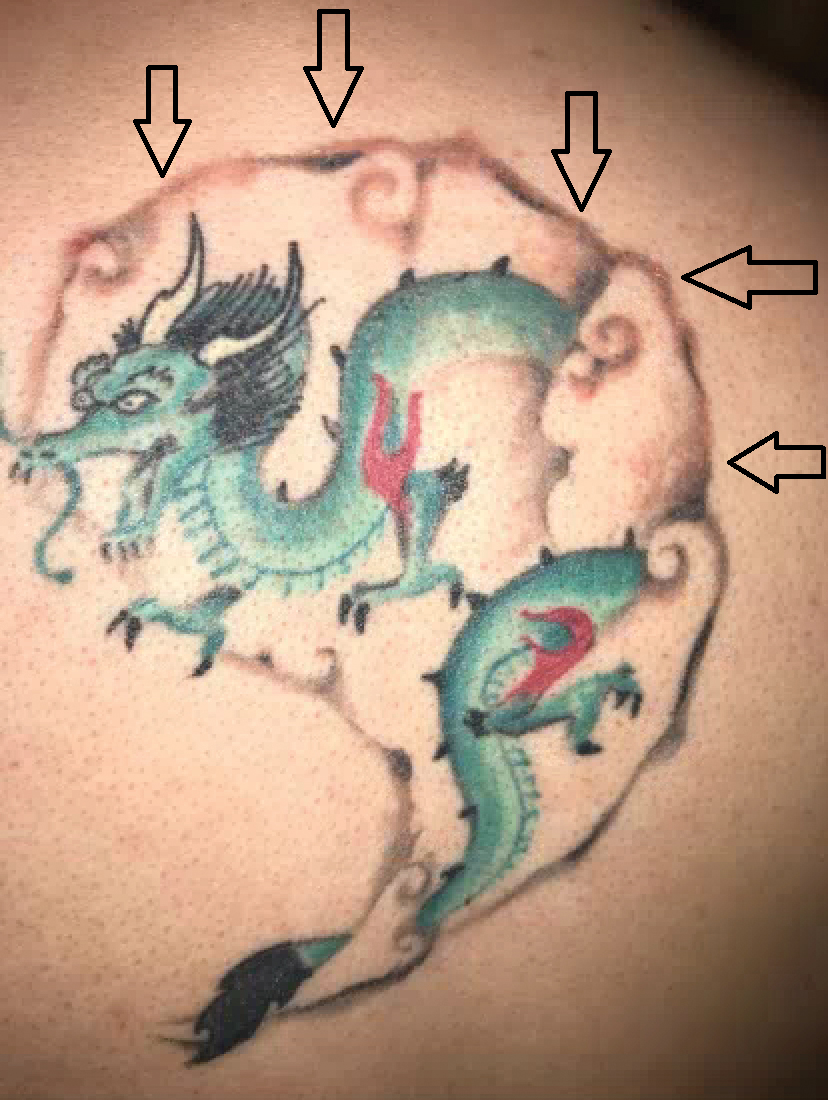

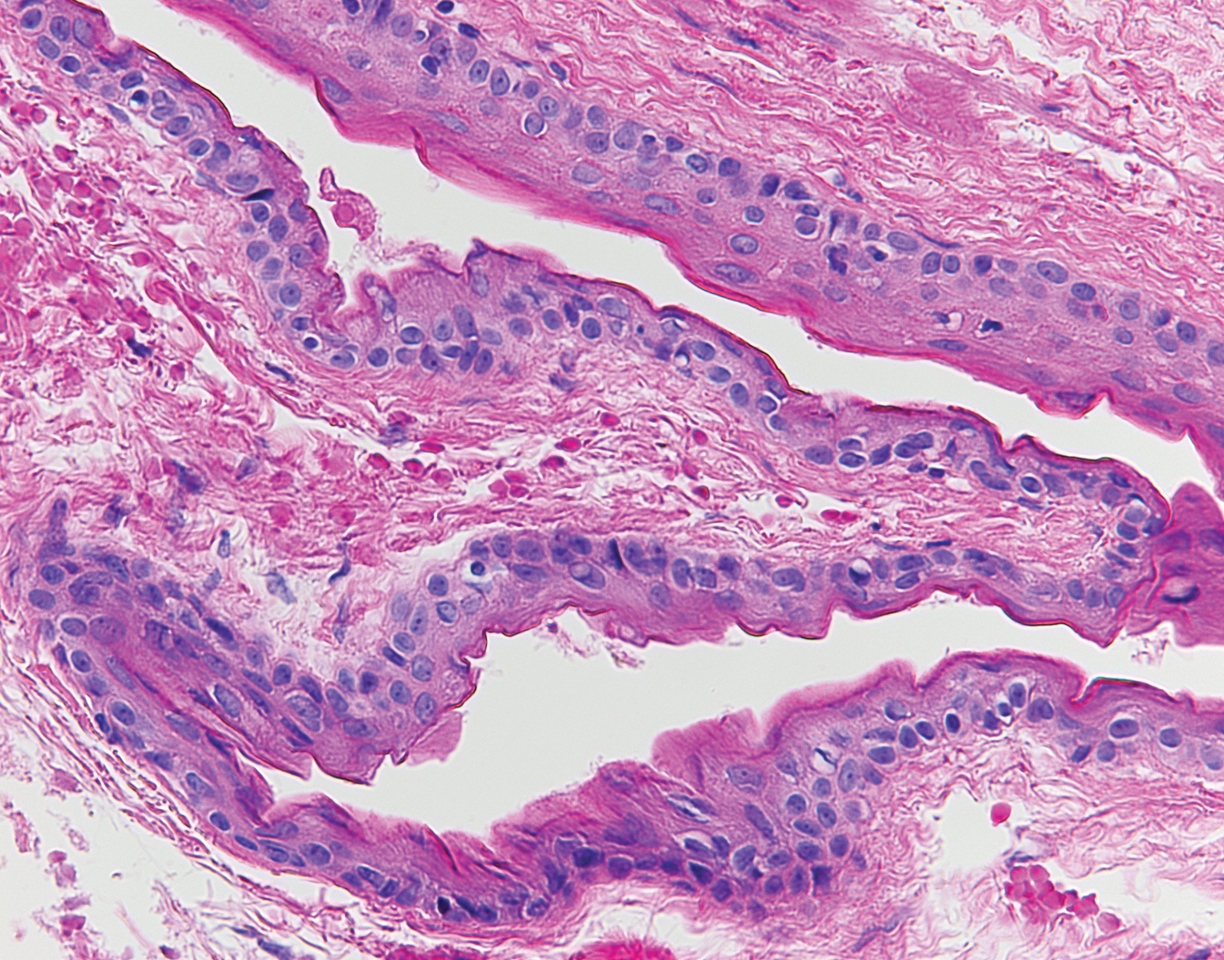

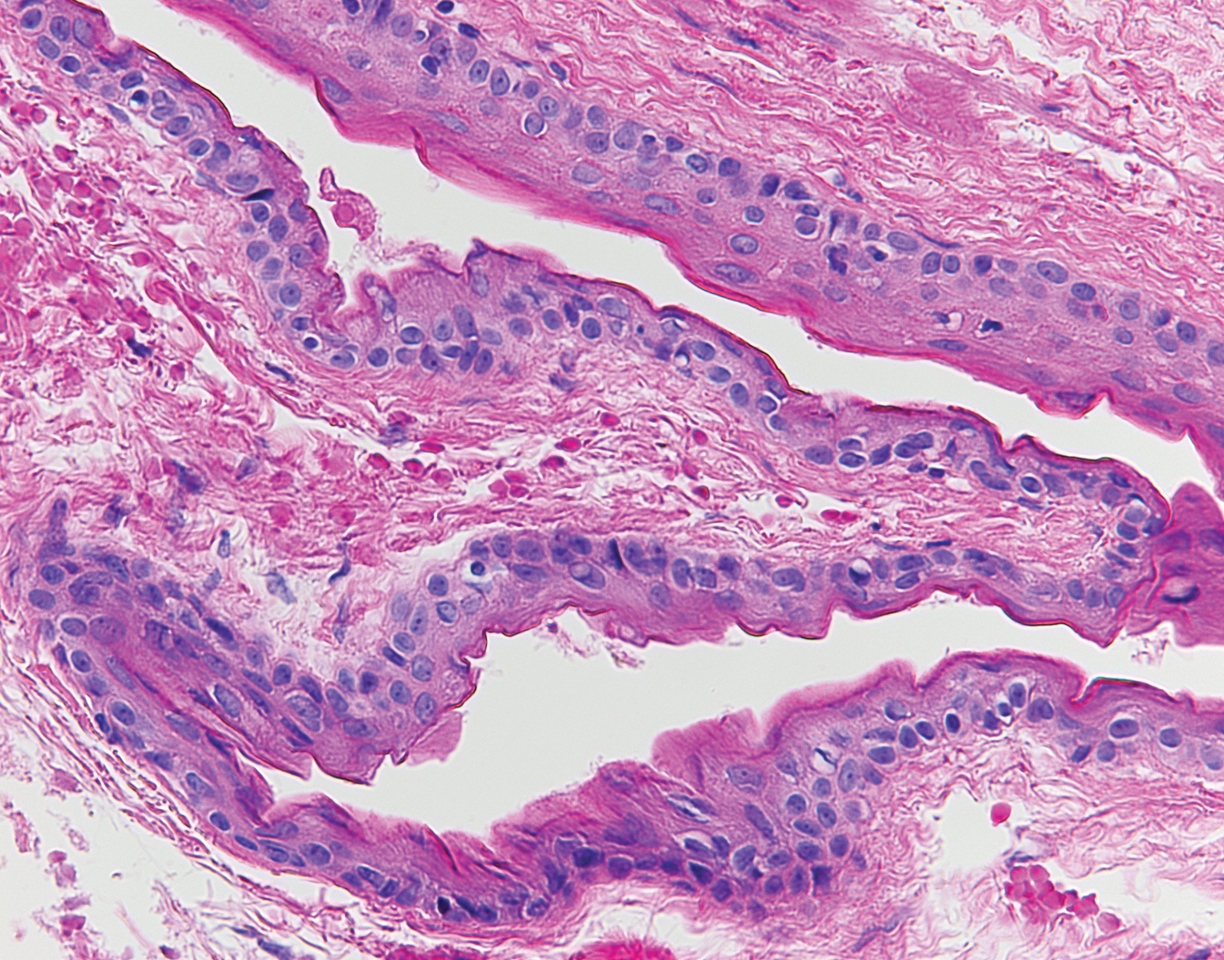

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

The Diagnosis: Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated acanthosis and coarse hypergranulosis with enlarged keratinocytes exhibiting blue cytoplasmic discoloration (Figure), which was suggestive of acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV).

Acquired EV is a rare dermatologic condition associated with specific human papillomavirus (HPV) types that presents with recalcitrant lesions most commonly in the setting of immunosuppression.1 The most common HPV types associated with EV are HPV-5 and -8, but associations with HPV-3, -9, -10, -12, -14, -15, -17, -19 to -25, -36 to -38, -47, and -50 also have been reported.1,2 Acquired EV has been identified in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, as well as in immunosuppressed patients with organ transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and IgM deficiency, and in patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 The diagnosis is clinicopathological with potential polymerase chain reaction studies to identify underlying HPV types.

Acquired EV presents as hypopigmented to red, tinea versicolor-like macules or as verrucous, flat-topped papules on the trunk, arms, and/or legs.4 Histopathology reveals viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypogranulosis.4

There is no standardized treatment regimen for acquired EV, and no single approach has proven to yield an efficacious clinical outcome. Topical treatment options include steroids, retinoids, immunomodulators, cryotherapy, and electrosurgery, whereas retinoids or interferon alfa have been used as oral systemic therapy. Photodynamic therapy also has been shown to improve symptoms.3 Combination therapy such as interferon alfa with zidovudine or imiquimod with oral isotretinoin has shown better results than any single treatment.4 Due to the underlying HPV infection and its role in promotion of skin cancer development, lesions can characteristically undergo malignant transformations into Bowen disease but most commonly invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with initial lesions preferentially affecting sun-exposed areas due to the synergistic effect of UV light with EV-HPV lesions. The EV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential.5 Little is known of the true incidence of oncogenicity for acquired EV. Regardless, consistent sun protection and lifelong clinical examinations are critical for prognosis.5

The differential diagnosis of EV presenting in a tattoo includes allergic contact dermatitis, cutaneous sarcoidosis, pityriasis versicolor, and SCC. The pathology is critical to differentiate between these entities. The most frequently reported skin reactions to tattoo ink include inflammatory diseases (eg, allergic contact dermatitis, granulomatous reaction) or infectious diseases (eg, bacterial, viral, fungal).6 Allergic contact dermatitis, typically red pigment, is a common tattoo reaction. The most common histologic feature, however, is spongiosis, which results from intercellular edema. It often is limited to the lower epidermis but may affect the upper layers if the reaction is severe.7 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is a great masquerader that can present in various ways; however, its salient features on pathology are noncaseating granuloma involving the basal cell layer and epithelioid granuloma consisting of Langerhans giant cells.8 Although pityriasis versicolor can present in young immunocompromised adults, histologically salient features are the presence of both spores and hyphae in the stratum corneum.9 Although immunosuppression is a known risk factor for SCC, it is characterized histologically by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis with thickened and elongated rete ridges. Scattered atypical cells and frequent mitoses are present.10

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

- Schultz B, Nguyen CV, Jacobson-Dunlop E. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in setting of tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol Case Rep. 2018;4:805-807.

- DeVilliers EM, Fauquet C, Brocker TR, et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27.

- Zampetti A, Giurdanella F, Manco S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis: a comprehensive review and a proposal for treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:974-980.

- Henley JK, Hossler EW. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a renal transplant recipient. Cutis. 2017;99:E9-E12.

- Berk DR, Bruckner AL, Lu D. Epidermodysplasia verruciform-like lesions in an HIV patient. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:1.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Cappello M, et al. Skin diseases and tattoos: a five-year experience. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:644-648.

- Nixon RL, Mowad CM, Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:242-259.

- Ferringer T. Granulomatous and histiocytic diseases. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier; 2019:175-176.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1329-1346.

- Soyer HP, Rigel DS, McMeniman E. Actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018:1887-1884.

A 29-year-old man presented with increased redness, dryness, and pruritus at the periphery of a tattoo (arrows) on the upper back of 4 months' duration. He was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus 8 months prior to presentation and had a history of cystic fibrosis, eczema, and genital molluscum contagiosum. Laboratory analysis 1 month prior revealed a CD4 count of 42 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1200 cells/mm3), and the viral load was 2388 copies/mL (reference range, 20-10,000,000 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous, eczematous, linear plaques along the dark gray lines of the tattoo. A 1.1.2 ×0.7.2 ×0.1-cm shave biopsy specimen was obtained. After the biopsy, tretinoin cream 0.1% and betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05% were prescribed to be alternately applied on the tattoo lesions until resolution.

Patient Questionnaire to Reduce Anxiety Prior to Full-Body Skin Examination

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

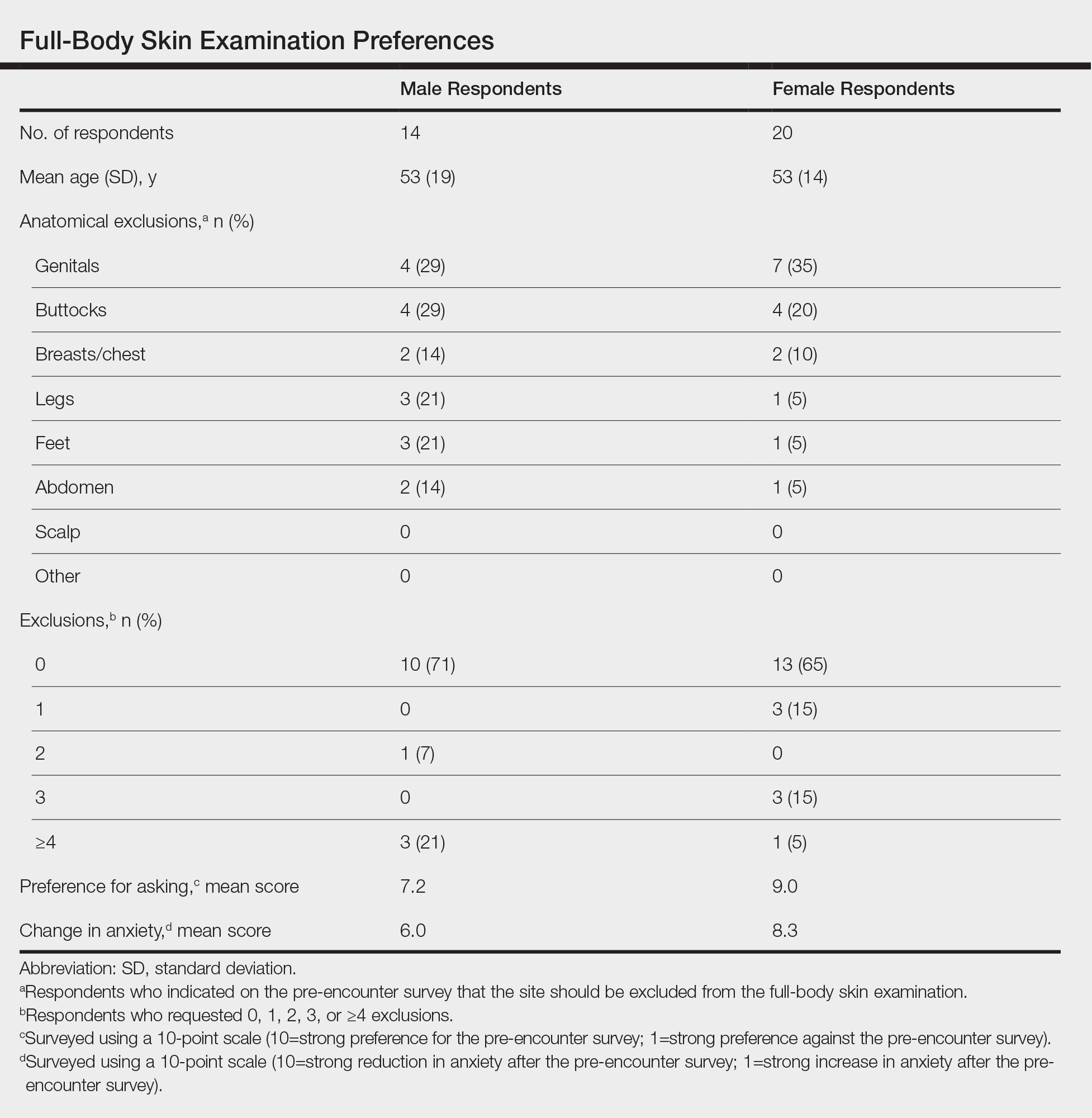

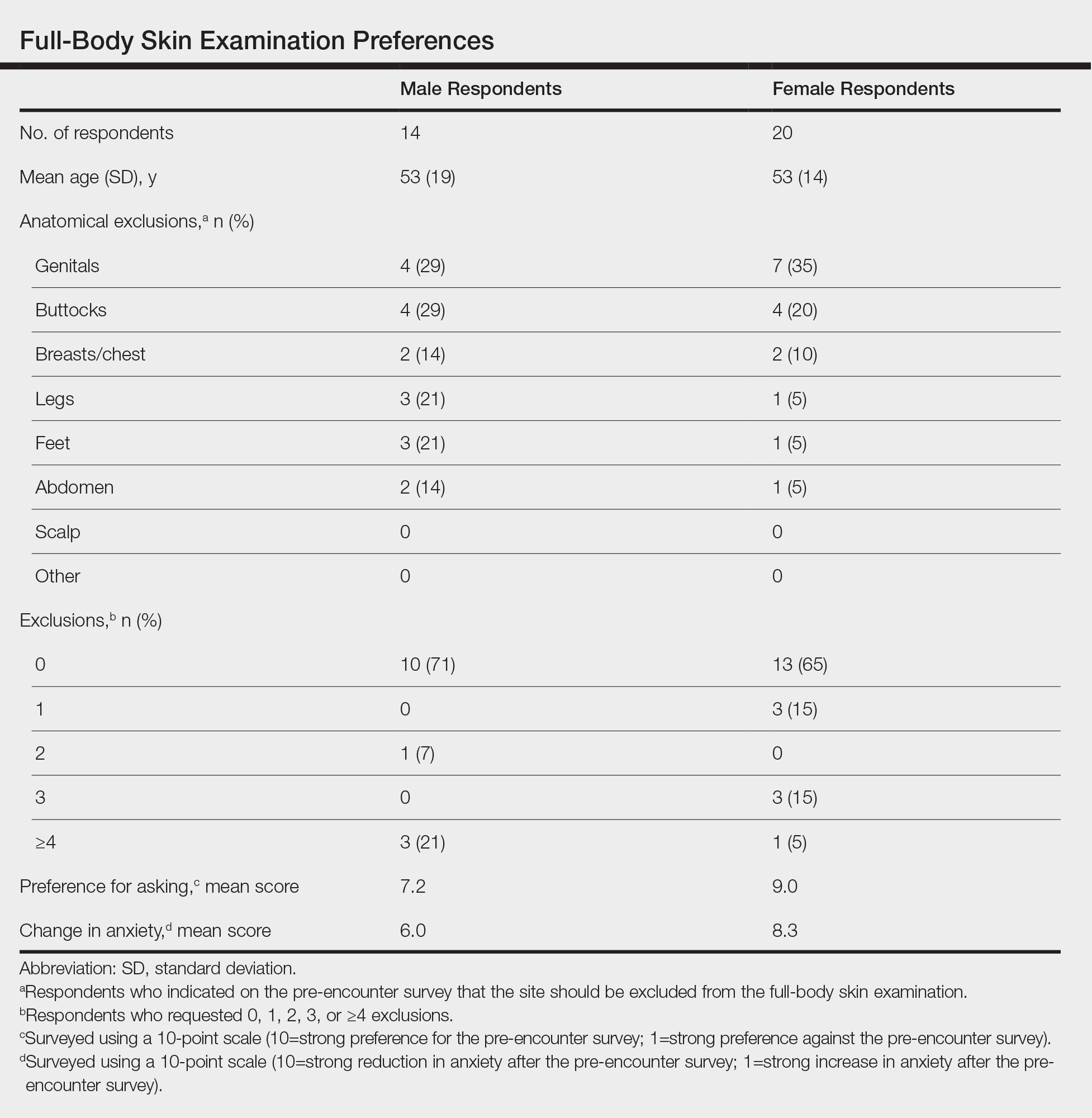

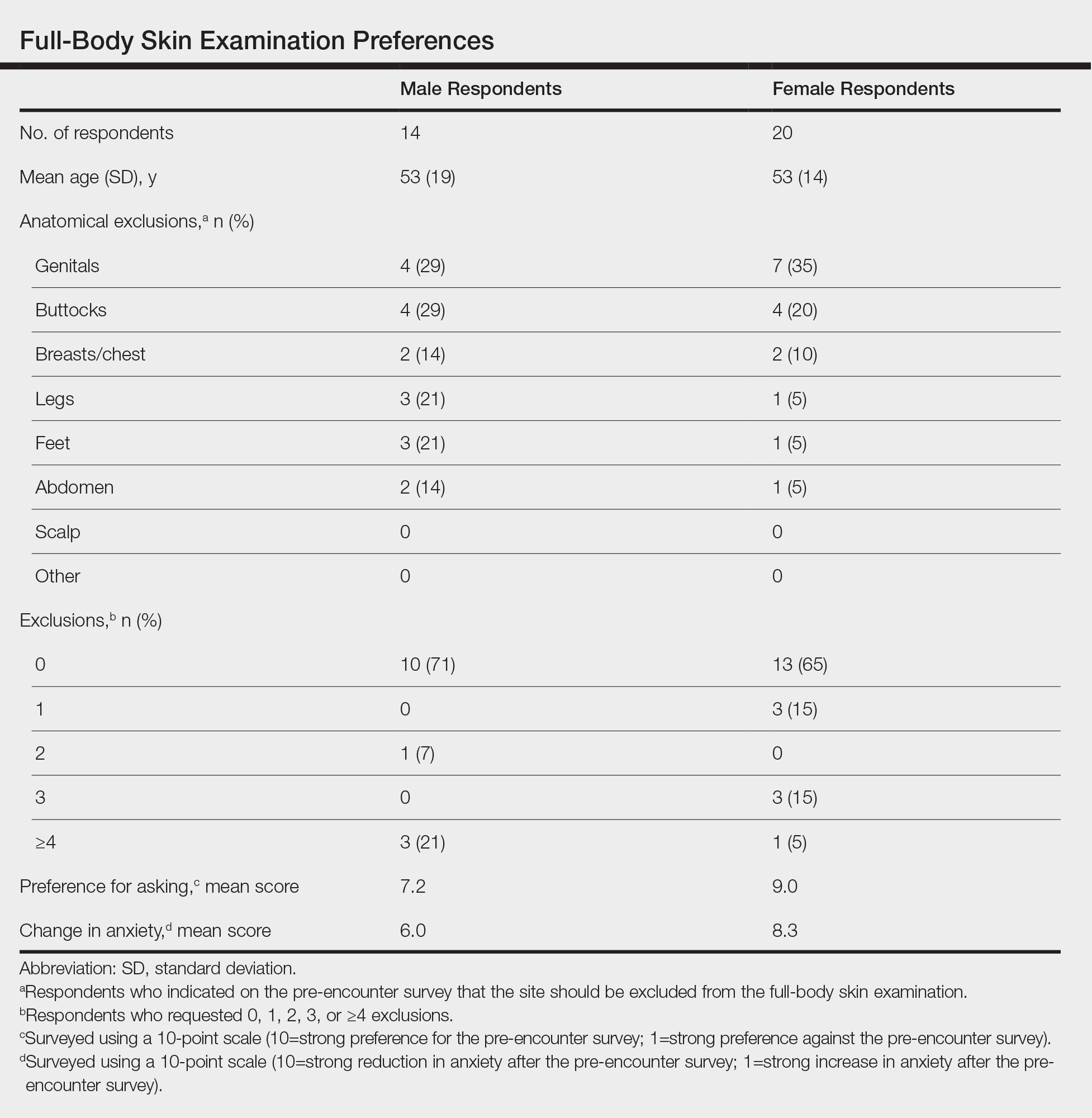

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

To the Editor:

A thorough full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an integral component of a dermatologic encounter and helps identify potentially malignant and high-risk lesions, particularly in areas that are difficult for the patient to visualize.1 Despite these benefits, many patients experience discomfort and anxiety about this examination because it involves sensitive anatomical areas. The true psychological impact of an FBSE is not clearly understood; however, research into improving patient comfort in these circumstances can have a broad positive impact.2 The purpose of this pilot study was to establish patients’ willingness to complete a pre-encounter questionnaire that defines their FBSE preferences as well as to identify the anatomical areas that are of most concern.

This study was approved by the University of Kansas institutional review board as nonhuman subjects research. A pre-encounter questionnaire that included information about the benefits of FBSEs was administered to 34 patients, allowing them to identify anatomic locations that they wanted to exclude from the FBSE.

Following the patient visit (in which the identified anatomical locations were excluded), patients were given a brief exit survey that asked about (1) their preference for a pre-encounter FBSE questionnaire and (2) the impact of the questionnaire on their anxiety level throughout the encounter. Preference for asking was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong preference for the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong preference against the pre-encounter survey). Change in anxiety was surveyed using a 10-point scale (10=strong reduction in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey; 1=strong increase in anxiety after the pre-encounter survey). Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed unpaired t tests, with P<.05 considered statistically significant.

Twenty female and 14 male patients were enrolled (mean age, 53 years)(Table). The most commonly excluded anatomical location on the pre-encounter survey was the genitals, followed by the buttocks, breasts/chest, legs, feet, and abdomen (Table); 10 (71%) male and 13 (65%) female respondents did not exclude any component of the FBSE.

After the provider visit, females had a higher preference for the pre-encounter survey (mean score, 9.0) compared to males (mean score, 7.2; P=.021). Similarly, females had reduced anxiety about the office visit after survey administration compared to males (mean score, 8.3 vs 6.0; P=.001)(Table).

The results of our pilot study showed that a brief pre-encounter questionnaire may reduce the distress associated with an FBSE. Our survey took less than 1 minute to complete and served as a useful guide to direct the provider during the FBSE. Moreover, recognizing that patients do not want certain anatomic locations examined can serve as an opportunity for the dermatologist to provide helpful home skin check instructions and recommendations.

The small sample size was a limitation of this study. Future studies can assess with greater precision the clear benefits of a pre-encounter survey as well as the benefits or drawbacks of a survey compared to other modalities that are aimed at reducing patient anxiety about the FBSE, such as having the physician directly ask the patient about areas to avoid during the examination.

A pre-encounter survey about the FBSE can serve as an efficient means of determining patient preference and reducing self-reported anxiety about the visit.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

- Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

- Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

Practice Points

- Full-body skin examination (FBSE) is an assessment that requires examination of sensitive body areas, any of which can be seen as intrusive by certain patients.

- A pre-encounter survey on the FBSE can offer an efficient means by which to determine patient preference and reduce visit-associated anxiety.

Pruritic Papules on the Face and Chest

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Folliculitis

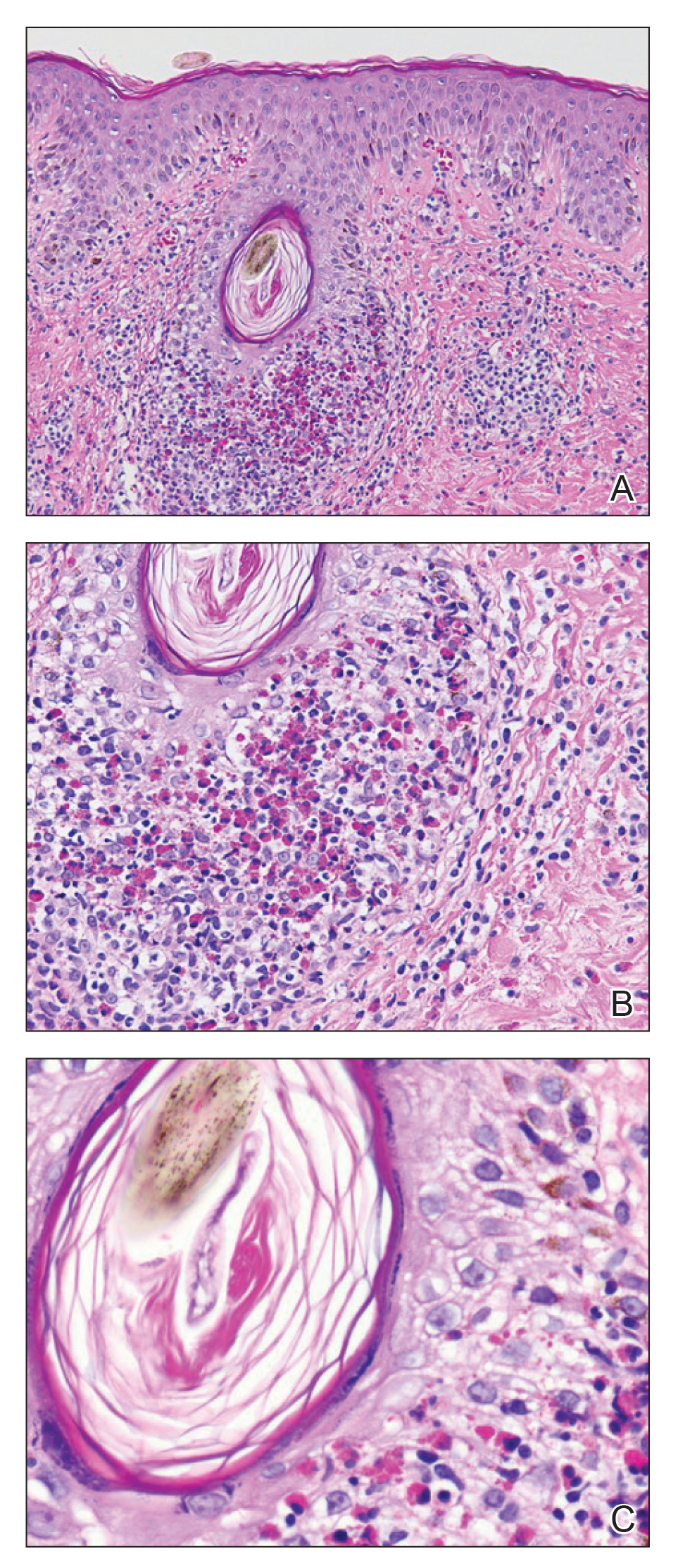

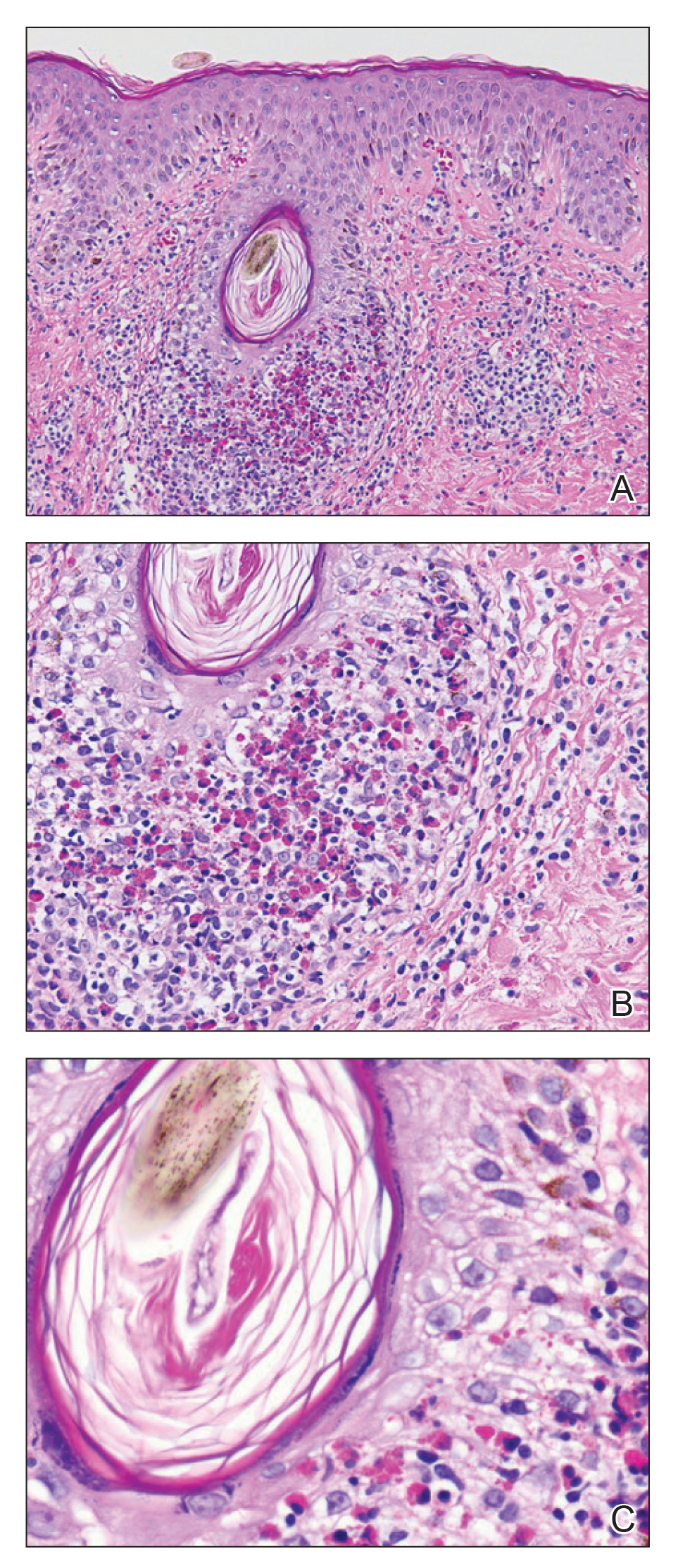

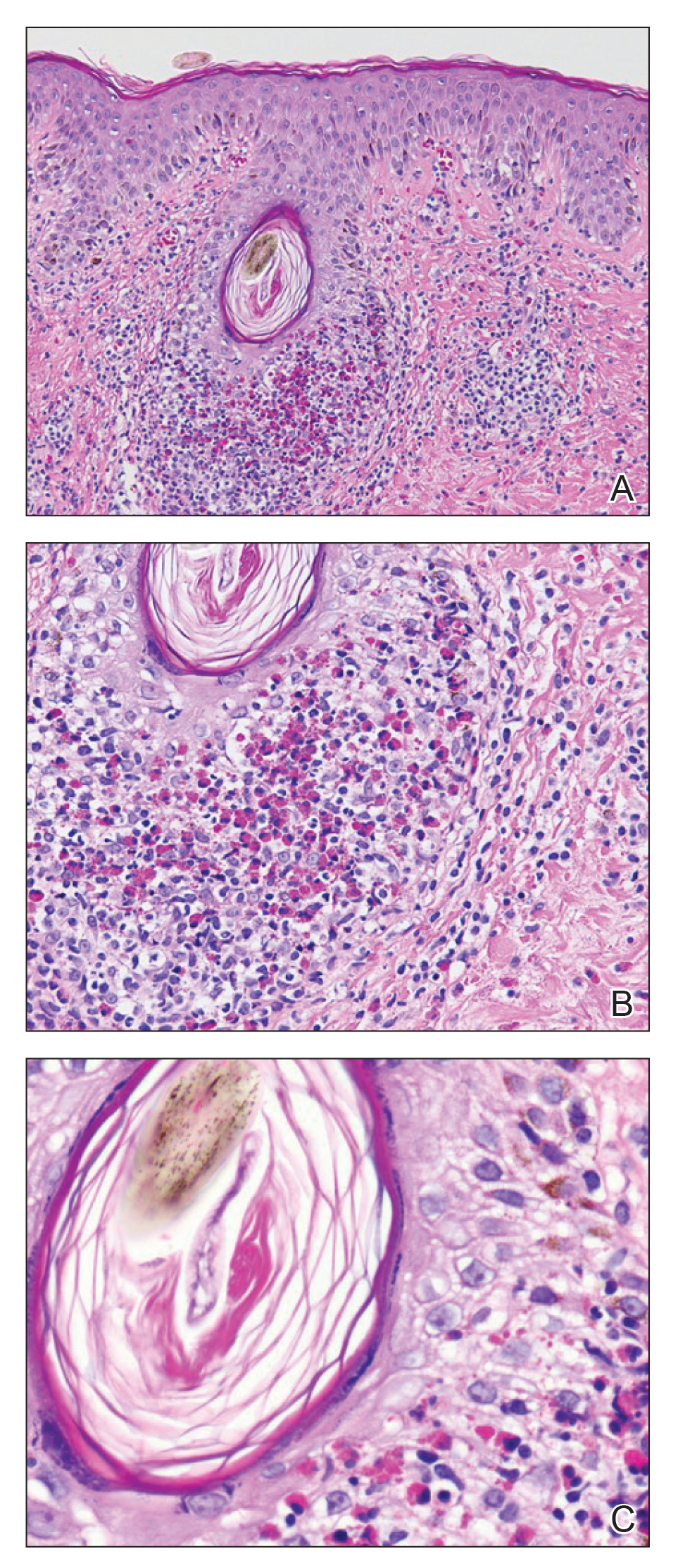

A shave biopsy specimen of an intact pustule on the left side of the chest was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed follicular inflammation with copious eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (EF) was made.

The patient was started on triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to active lesions, oral cetirizine 10 mg in the morning, and oral hydroxyzine 25 mg at bedtime. Laboratory evaluation at the time of diagnosis showed eosinophilia with a peripheral blood eosinophil count of 0.5 K/μL (reference range, 0.03–0.48 K/μL).

Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF is a pruritic follicular eruption that occurs in HIV-positive individuals with advanced disease. Clinically, it is characterized by intermittent, urticarial, red or flesh-colored, 2- to 5-mm papules with sparse pustules involving the head, neck, arms, and upper trunk.1,2 The cardinal clinical feature of the disorder is intense pruritus, with overlying crusts and excoriations present on physical examination.3

Patients usually have a CD4 count of less than 250 cells/mm3.2,3 Patients with HIV can develop an exacerbation of EF in the first 3 to 6 months after initiating antiretroviral therapy. This clinical pattern is believed to be due to the reconstituted immune system and increased circulation of inflammatory cells.4 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels are found in 25% to 50% of patients with HIV-associated EF.2,3

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of intensely pruritic papules with excoriations should include scabies.3 Other diagnoses to consider include opportunistic infections and papular urticaria.5 Acne vulgaris and Demodex folliculitis also may present with lesions similar to HIV-associated EF; however, these lesions tend not to be as intensely pruritic.1,5

The etiology of HIV-associated EF is unknown.3 One proposed mechanism involves a hypersensitivity reaction to Pityrosporum or Demodex mite fragments, as evidenced by studies that found fragments of these microorganisms in biopsied lesions of HIV-associated EF.3,6 In our patient's histopathology, it was noted that the afflicted hair follicle held a single Demodex mite (Figure, C).

The histopathology is characterized by a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophils and CD8+ lymphocytes with areas of sebaceous lysis.3,6 Spongiosis of the follicular epithelium is seen in early lesions of HIV-associated EF.6

The first-line treatment of HIV-associated EF includes antiretroviral therapy with topical steroids and antihistamines. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF improves as CD4 helper T-cell counts rise above 250 cells/mm3 with continued antiretroviral therapy, though it initially can cause a flare of the condition.4 High-potency steroids and antihistamines are added during this period to treat the severe pruritus.1,7 In particular, daily cetirizine has been shown to be effective, which may be due to its ability to block eosinophil migration in addition to H1-receptor antagonist properties.3,7

Various alternative therapies have been described in case reports and case series; however, there have been no controlled studies comparing therapies. Phototherapy with UVB light 3 times weekly for 3 to 6 weeks has been effective and curative in recalcitrant cases.7 Other frequently used treatments include oral metronidazole, oral itraconazole, and permethrin cream 5%. The effectiveness of the latter 2 treatments is believed to be related to the proposed role of Pityrosporum and Demodex in the pathogenesis.3

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his help compiling the histopathological images and their diagnostic descriptions.

- Parker SR, Parker DC, McCall CO. Eosinophilic folliculitis in HIV-infected women: case series and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:193-200.

- Rosenthal D, LeBoit PE, Klumpp L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated eosinophilic folliculitis. a unique dermatosis associated with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:206-209.

- Fearfield LA, Rowe A, Francis N, et al. Itchy folliculitis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: clinicopathological and immunological features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:3-11.

- Rajendran PM, Dolev JC, Heaphy MR, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1227-1231.

- Nervi SJ, Schwartz RA, Dmochowski M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- McCalmont TH, Altemus D, Maurer T, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: the histological spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:439-446.

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197.

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Folliculitis

A shave biopsy specimen of an intact pustule on the left side of the chest was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed follicular inflammation with copious eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (EF) was made.

The patient was started on triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to active lesions, oral cetirizine 10 mg in the morning, and oral hydroxyzine 25 mg at bedtime. Laboratory evaluation at the time of diagnosis showed eosinophilia with a peripheral blood eosinophil count of 0.5 K/μL (reference range, 0.03–0.48 K/μL).

Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF is a pruritic follicular eruption that occurs in HIV-positive individuals with advanced disease. Clinically, it is characterized by intermittent, urticarial, red or flesh-colored, 2- to 5-mm papules with sparse pustules involving the head, neck, arms, and upper trunk.1,2 The cardinal clinical feature of the disorder is intense pruritus, with overlying crusts and excoriations present on physical examination.3

Patients usually have a CD4 count of less than 250 cells/mm3.2,3 Patients with HIV can develop an exacerbation of EF in the first 3 to 6 months after initiating antiretroviral therapy. This clinical pattern is believed to be due to the reconstituted immune system and increased circulation of inflammatory cells.4 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels are found in 25% to 50% of patients with HIV-associated EF.2,3

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of intensely pruritic papules with excoriations should include scabies.3 Other diagnoses to consider include opportunistic infections and papular urticaria.5 Acne vulgaris and Demodex folliculitis also may present with lesions similar to HIV-associated EF; however, these lesions tend not to be as intensely pruritic.1,5

The etiology of HIV-associated EF is unknown.3 One proposed mechanism involves a hypersensitivity reaction to Pityrosporum or Demodex mite fragments, as evidenced by studies that found fragments of these microorganisms in biopsied lesions of HIV-associated EF.3,6 In our patient's histopathology, it was noted that the afflicted hair follicle held a single Demodex mite (Figure, C).

The histopathology is characterized by a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophils and CD8+ lymphocytes with areas of sebaceous lysis.3,6 Spongiosis of the follicular epithelium is seen in early lesions of HIV-associated EF.6

The first-line treatment of HIV-associated EF includes antiretroviral therapy with topical steroids and antihistamines. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF improves as CD4 helper T-cell counts rise above 250 cells/mm3 with continued antiretroviral therapy, though it initially can cause a flare of the condition.4 High-potency steroids and antihistamines are added during this period to treat the severe pruritus.1,7 In particular, daily cetirizine has been shown to be effective, which may be due to its ability to block eosinophil migration in addition to H1-receptor antagonist properties.3,7

Various alternative therapies have been described in case reports and case series; however, there have been no controlled studies comparing therapies. Phototherapy with UVB light 3 times weekly for 3 to 6 weeks has been effective and curative in recalcitrant cases.7 Other frequently used treatments include oral metronidazole, oral itraconazole, and permethrin cream 5%. The effectiveness of the latter 2 treatments is believed to be related to the proposed role of Pityrosporum and Demodex in the pathogenesis.3

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his help compiling the histopathological images and their diagnostic descriptions.

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Folliculitis

A shave biopsy specimen of an intact pustule on the left side of the chest was obtained. Histopathologic examination revealed follicular inflammation with copious eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (EF) was made.

The patient was started on triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to active lesions, oral cetirizine 10 mg in the morning, and oral hydroxyzine 25 mg at bedtime. Laboratory evaluation at the time of diagnosis showed eosinophilia with a peripheral blood eosinophil count of 0.5 K/μL (reference range, 0.03–0.48 K/μL).

Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF is a pruritic follicular eruption that occurs in HIV-positive individuals with advanced disease. Clinically, it is characterized by intermittent, urticarial, red or flesh-colored, 2- to 5-mm papules with sparse pustules involving the head, neck, arms, and upper trunk.1,2 The cardinal clinical feature of the disorder is intense pruritus, with overlying crusts and excoriations present on physical examination.3

Patients usually have a CD4 count of less than 250 cells/mm3.2,3 Patients with HIV can develop an exacerbation of EF in the first 3 to 6 months after initiating antiretroviral therapy. This clinical pattern is believed to be due to the reconstituted immune system and increased circulation of inflammatory cells.4 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels are found in 25% to 50% of patients with HIV-associated EF.2,3

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of intensely pruritic papules with excoriations should include scabies.3 Other diagnoses to consider include opportunistic infections and papular urticaria.5 Acne vulgaris and Demodex folliculitis also may present with lesions similar to HIV-associated EF; however, these lesions tend not to be as intensely pruritic.1,5

The etiology of HIV-associated EF is unknown.3 One proposed mechanism involves a hypersensitivity reaction to Pityrosporum or Demodex mite fragments, as evidenced by studies that found fragments of these microorganisms in biopsied lesions of HIV-associated EF.3,6 In our patient's histopathology, it was noted that the afflicted hair follicle held a single Demodex mite (Figure, C).

The histopathology is characterized by a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate of eosinophils and CD8+ lymphocytes with areas of sebaceous lysis.3,6 Spongiosis of the follicular epithelium is seen in early lesions of HIV-associated EF.6

The first-line treatment of HIV-associated EF includes antiretroviral therapy with topical steroids and antihistamines. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated EF improves as CD4 helper T-cell counts rise above 250 cells/mm3 with continued antiretroviral therapy, though it initially can cause a flare of the condition.4 High-potency steroids and antihistamines are added during this period to treat the severe pruritus.1,7 In particular, daily cetirizine has been shown to be effective, which may be due to its ability to block eosinophil migration in addition to H1-receptor antagonist properties.3,7

Various alternative therapies have been described in case reports and case series; however, there have been no controlled studies comparing therapies. Phototherapy with UVB light 3 times weekly for 3 to 6 weeks has been effective and curative in recalcitrant cases.7 Other frequently used treatments include oral metronidazole, oral itraconazole, and permethrin cream 5%. The effectiveness of the latter 2 treatments is believed to be related to the proposed role of Pityrosporum and Demodex in the pathogenesis.3

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Garth Fraga, MD (Kansas City, Kansas), for his help compiling the histopathological images and their diagnostic descriptions.

- Parker SR, Parker DC, McCall CO. Eosinophilic folliculitis in HIV-infected women: case series and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:193-200.

- Rosenthal D, LeBoit PE, Klumpp L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated eosinophilic folliculitis. a unique dermatosis associated with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:206-209.

- Fearfield LA, Rowe A, Francis N, et al. Itchy folliculitis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: clinicopathological and immunological features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:3-11.

- Rajendran PM, Dolev JC, Heaphy MR, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1227-1231.

- Nervi SJ, Schwartz RA, Dmochowski M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- McCalmont TH, Altemus D, Maurer T, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: the histological spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:439-446.

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197.

- Parker SR, Parker DC, McCall CO. Eosinophilic folliculitis in HIV-infected women: case series and review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:193-200.

- Rosenthal D, LeBoit PE, Klumpp L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated eosinophilic folliculitis. a unique dermatosis associated with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:206-209.

- Fearfield LA, Rowe A, Francis N, et al. Itchy folliculitis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: clinicopathological and immunological features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:3-11.

- Rajendran PM, Dolev JC, Heaphy MR, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: before and after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1227-1231.

- Nervi SJ, Schwartz RA, Dmochowski M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- McCalmont TH, Altemus D, Maurer T, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: the histological spectrum. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:439-446.

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197.

A 31-year-old man presented with a severely pruritic rash of 2 weeks' duration. Physical examination revealed numerous urticarial papules and rare erythematous pustules over the face (top), upper chest (bottom), and proximal arms; most lesions were excoriated. Additionally, there were numerous hyperpigmented papules with central hypopigmentation on the upper chest and arms. The lower half of the body was spared. His medical history was notable for human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS with a prior episode of Pneumocystis pneumonia. He had been noncompliant with antiretroviral therapy for the last 2 years but restarted therapy 3 weeks prior to presentation. Laboratory test results revealed a CD4 cell count of 13 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500-1500 cells/mm3) with a viral load of 179 copies/mL (reference range, undetectable).

Tense Bullae on the Hands

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

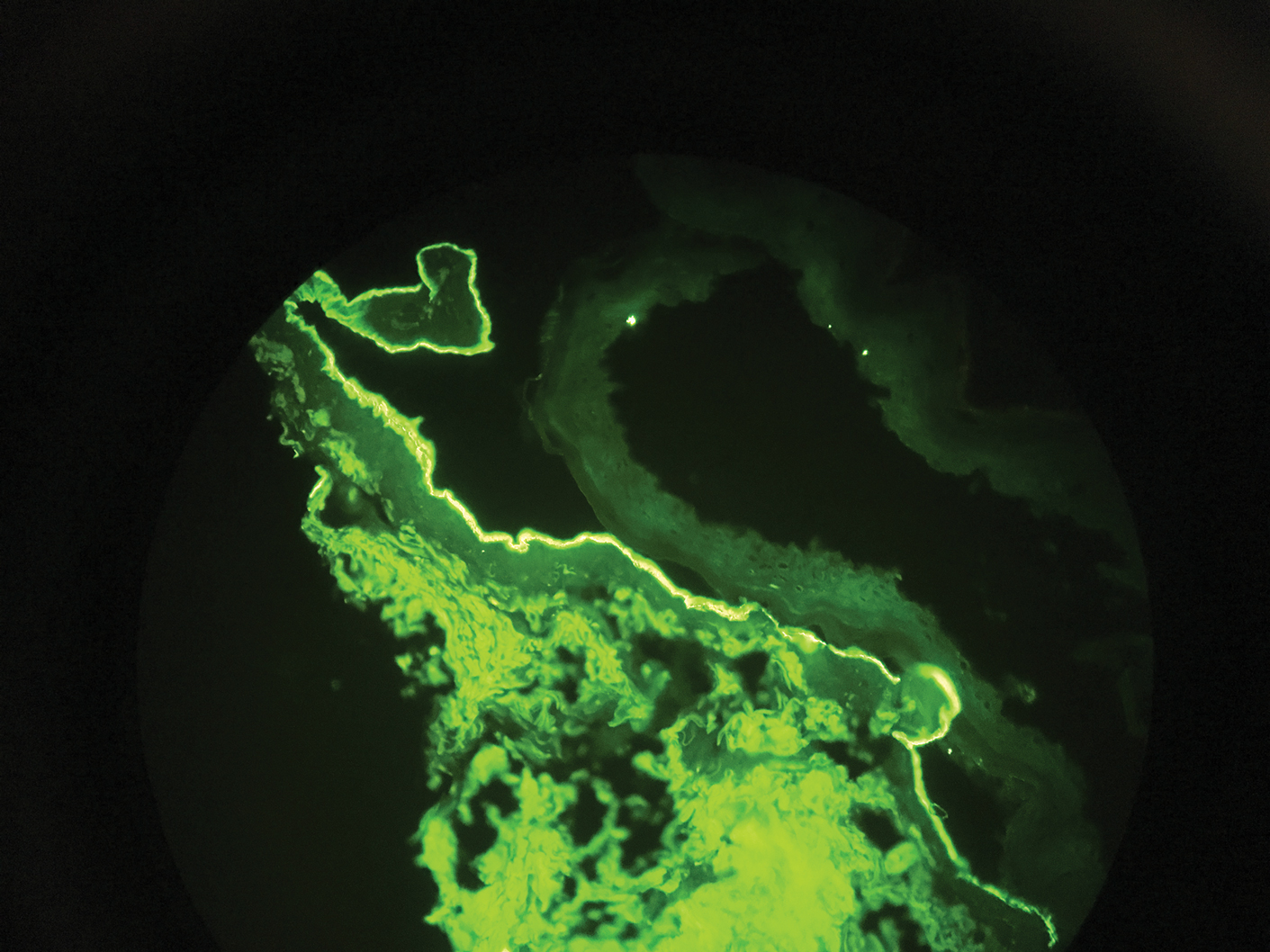

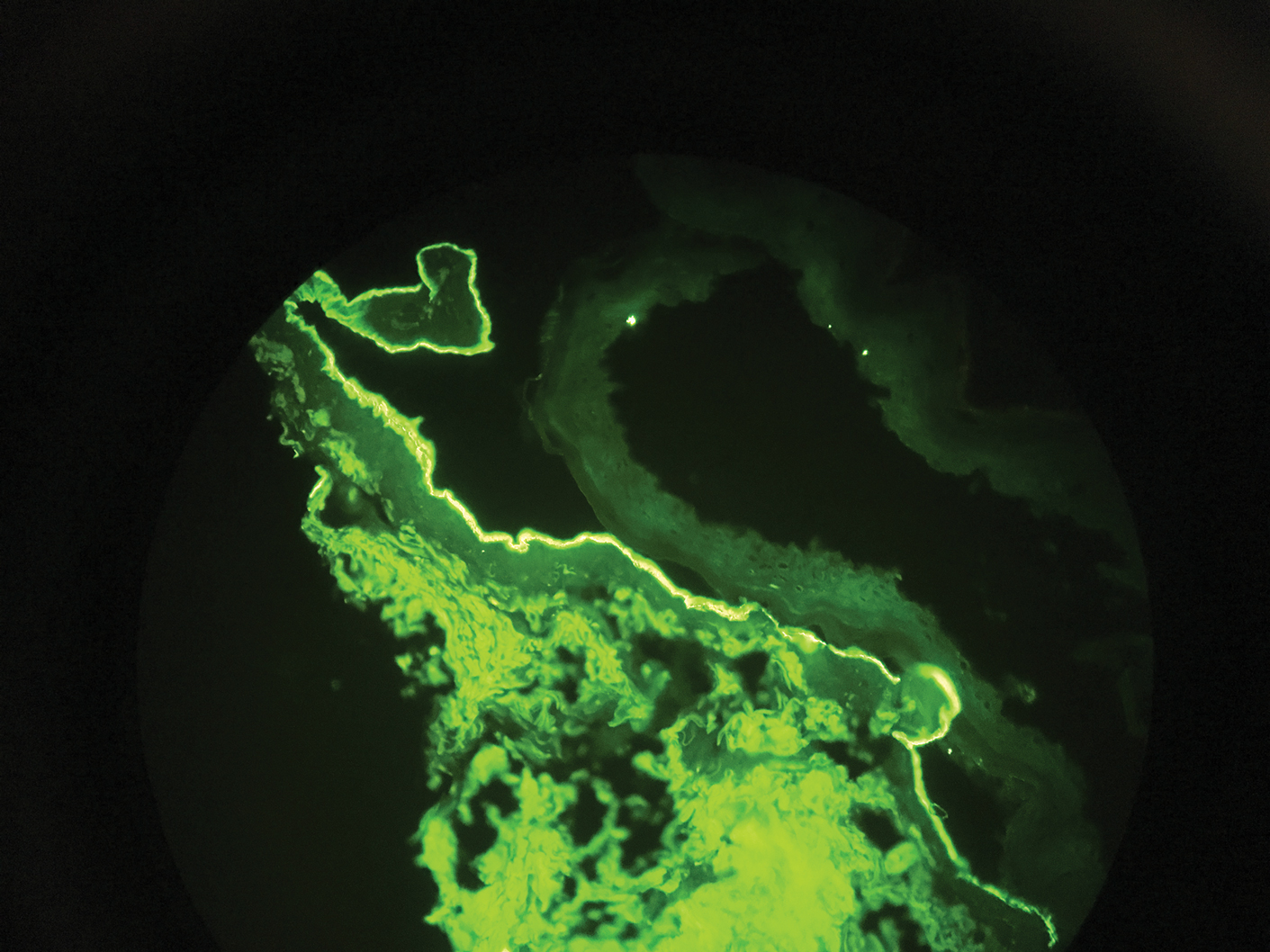

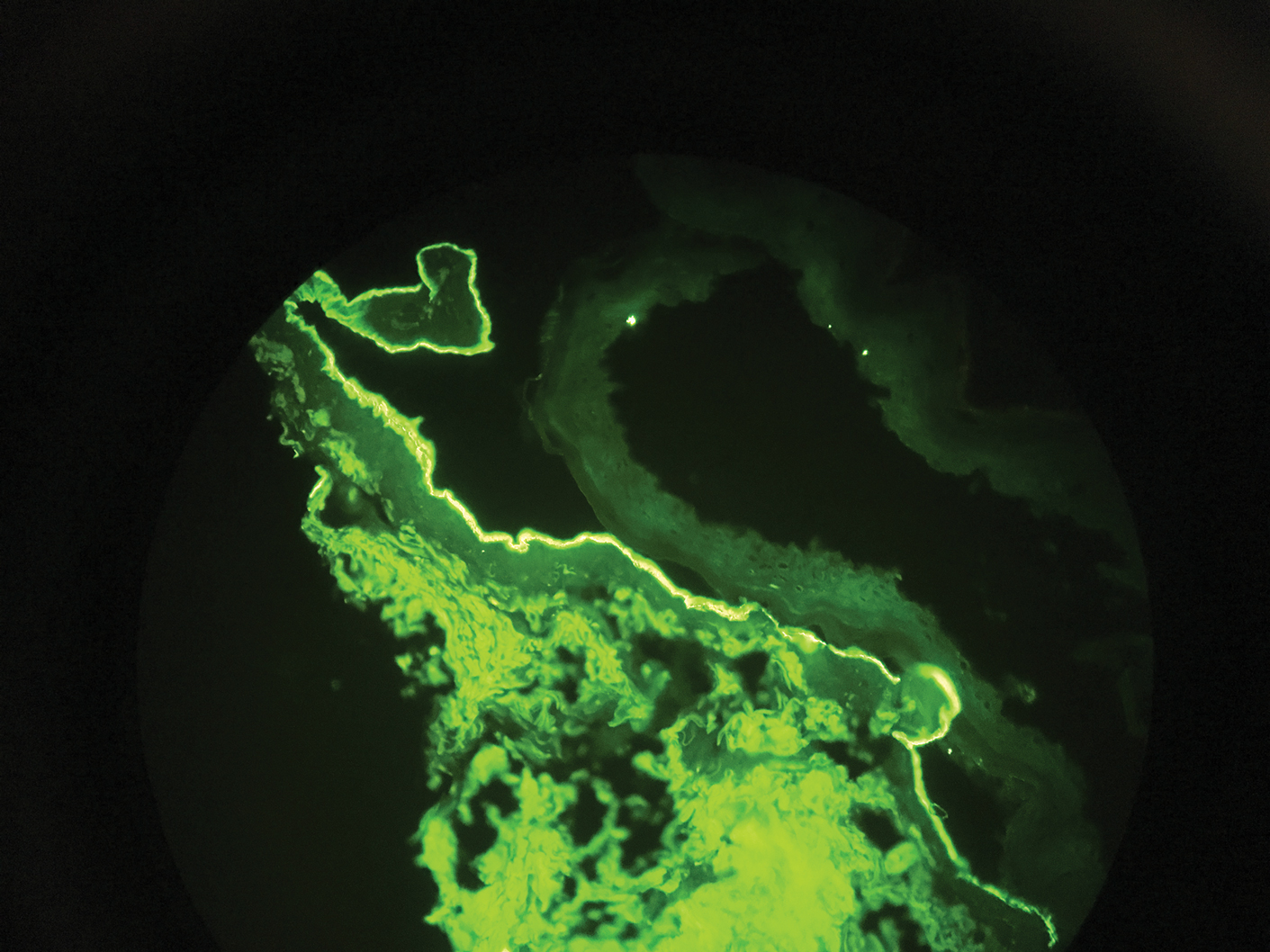

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

A 75-year-old man presented to our clinic with nonpainful, nonpruritic, tense bullae and erosions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and extensor surfaces of the elbows of 1 month's duration. The patient also had erythematous erosions and crusted papules on the left cheek and surrounding the left eye. He denied any new medications, history of liver or kidney disease, or history of hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus. There were no obvious exacerbating factors, including exposure to sunlight. Direct immunofluorescence using a salt-split preparation was performed on a biopsy of the perilesional skin.

Unilateral Vesicular Eruption in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

A 4-day-old female neonate presented to the dermatology clinic with a vesicular eruption on the left leg of 1 day's duration. The eruption was asymptomatic without any extracutaneous findings. This term infant was born without complication, and the mother denied any symptoms consistent with herpes simplex virus infection. Physical examination revealed yellow-red vesicles on an erythematous base in a blaschkoid distribution on the left leg. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction testing was negative.

Smooth Papules on the Left Hand

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.

Treatment has not proven to be consistently helpful, as cryotherapy and dermabrasion have been the mainstay of treatment, often with disappointing results.4 Laser treatment has been shown to be of some benefit in treating these lesions.2

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 1):149-171.

- Pourrabbani S, Marra DE, Iwasaki J, et al. Colloid milium: a review and update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:293-296.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012.

- Netscher DT, Sharma S, Kinner BM, et al. Adult-type colloid milium of hands and face successfully treated with dermabrasion. South Med J. 1996;89:1004-1007.

The Diagnosis: Adult Colloid Milium

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and histopathologic evaluation revealed collections of amorphic eosinophilic material and fissures in the papillary dermis with sparing of the dermoepidermal junction, indicating adult colloid milium (Figure 1).

Adult colloid milium is an uncommon condition with grouped translucent to whitish papules that present on sun-exposed skin on the hands, face, neck, or ears in middle-aged adults.1 It has been associated with petrochemical exposure, tanning bed use, and excessive sun exposure. Our patient had a history of sun exposure, specifically to the left hand while driving. This condition is widely thought to be a result of photoinduced damage to elastic fibers and may potentially be a popular variant of severe solar elastosis.2 Due to vascular fragility, trauma to these locations often will result in hemorrhage into individual lesions, as observed in our patient (Figure 2).

Adult colloid milium is diagnosed clinically and may mimic lichen or systemic amyloidosis, syringomas, lipoid proteinosis, molluscum contagiosum, steatocystoma multiplex, and sarcoidosis.2

Biopsy often is helpful in determining the diagnosis. Histopathology reveals amorphous eosinophilic deposits with fissures in the papillary dermis. These deposits are thought to be remnants of degenerated elastic fibers. Stains often are helpful, as the deposits are weakly apple-green birefringent on Congo red stain and are periodic acid-Schiff and thioflavin T positive. Laminin and type IV collagen stains are negative with adult colloid milium but are positive with amyloidosis and lipoid proteinosis.3 Electron microscopy also may help distinguish between amyloidosis and adult colloid milium, as these conditions may have a similar histologic appearance.