User login

Is your patient a candidate for Mohs micrographic surgery?

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a unique dermatologic surgery technique that allows the dermatologist to fill the concomitant roles of surgeon and pathologist. It is utilized for the extirpation of skin malignancy, with an emphasis on tissue preservation and immediate surgical margin evaluation. In MMS, the Mohs surgeon acts as the surgeon for physical removal of the lesion and the pathologist during evaluation of frozen section margins.1

Primary care providers (PCPs) are on the frontlines of management of cutaneous malignancy. Whether referring to Dermatology for biopsy or performing a biopsy themselves, PCPs can assure optimal treatment outcomes by guiding patients to evidence-based treatments, while still respecting the patient’s wishes. In this evidence-based review of the advantages, improved outcomes, and safety of Mohs surgery for the treatment of common and rare skin neoplasms, we provide our primary care colleagues with information on the indications, process (the order in which steps of the procedure are performed), and techniques used for treating cutaneous malignancies with Mohs surgery.

When is Mohs surgery appropriate?

MMS has typically been reserved for treatment of cutaneous malignancy in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue preservation is key. In 2012, Connolly et al released appropriate use criteria (AUC) for MMS.2 (See “An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery.”) Within the AUC, there are 4 major qualitative and quantitative categories when considering referral for MMS:

- area of the body in which the lesion manifests

- the patient’s medical characteristics

- tumor characteristics

- the size of the lesion to be treated.2

Areas of the body are divided into 3 categories by the AUC according to how challenging tumor extirpation is expected to be and how critical tissue preservation is. Areas termed “H” receive the highest score for appropriate Mohs usage, followed by areas “M” and “L.”

SIDEBAR

An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery

“Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria” is a free and easy-to-use smartphone application to help determine whether Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is appropriate for a particular patient. Clinicians can enter the details of a recent skin cancer biopsy along with patient information into the app and it will calculate a score automatically categorized into 1 of 3 categories: “appropriate,” “uncertain,” and “not appropriate” for MMS. The clinician can then talk to the patient about a possible referral to a Mohs surgeon, depending on the appropriateness of the procedure for the patient and their tumor.

Patient medical characteristics that should be taken into account when referring for Mohs surgery are the patient’s immune status, genetic syndromes that may predispose the patient to cutaneous malignancies (eg, xeroderma pigmentosa), history of radiation to the area of involvement, and the patient’s history of aggressive cutaneous malignancies.

Tumor characteristics. The most common malignancies treated with MMS include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These malignancies are further delineated through histologic evaluation by a pathologist or dermatopathologist. Aggressive features of a BCC on any area of the body that warrant referral to a Mohs surgeon include morpheaform/fibrosing/sclerosing histologic findings, as well as micronodular architecture and perineural invasion. Concerning histologic SCC findings that warrant Mohs surgery through the AUC include sclerosing, basosquamous, and small cell histology, as well as poorly differentiated and/or undifferentiated SCC.

Melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna, which are variants of melanoma limited to the epidermis without invasion into the underlying dermis, are included within the AUC for MMS. For invasive melanoma (melanoma that has invaded into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue), MMS has been shown to have marginal benefit but currently is not included within the AUC.3

Continue to: Due to excellent margin control...

Due to excellent margin control via immediate microscopic evaluation of surgical margins, MMS is an appropriate treatment choice and indicated for many more uncommon cutaneous malignancies, including sebaceous and mucinous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, atypical fibroxanthoma, angiosarcoma, and other more rarely encountered clinical malignancies.2

Tumor size. When considering a referral to MMS for cancer extirpation, the size of the tumor does play a role; however, size depends on the type of tumor as well as the location on the body. In general, most skin cancers of any size on the face, perianal area, genitalia, nipples, hands, feet and ankles, or pretibial surface are appropriate for Mohs surgery. Skin cancers on the trunk and extremities are also appropriate if they are above a certain size specified by the AUC. Tumor type and whether they are recurrences also factor into the equation.

Who will do the procedure?

A recent review showed that PCPs were more likely to refer patients to plastic surgery rather than Mohs surgery for skin cancer removal, especially among younger female patients.4 This is likely because of the perception that plastic surgeons do more complex closures and have more experience removing difficult cancers. Interestingly, this same study showed that Mohs surgeons may actually be doing several-fold more complex closures (flaps and grafts) on the nose and ears than plastic surgeons at similar practice settings.4

Aside from Mohs surgeons doing more closures, perhaps the biggest difference between Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons is the pathology training of the Mohs surgeon. Mohs surgeons evaluate 100% of the tissue margins at the time of the procedure to both ensure complete tumor removal and to preserve as much tumor-free skin as possible, ultimately resulting in decreased recurrences and smaller scars. In contrast, the plastic surgeon’s rigorous training typically does not include extensive dermatopathology training, particularly the pathology of cutaneous neoplasms. Plastic surgeons will often send pathologic specimens for evaluation, meaning patients have to wait for outside histologic confirmation before their wounds can be closed. Additionally, the histologic evaluation is often not a full-margin assessment, as not all labs are equipped for this technique.

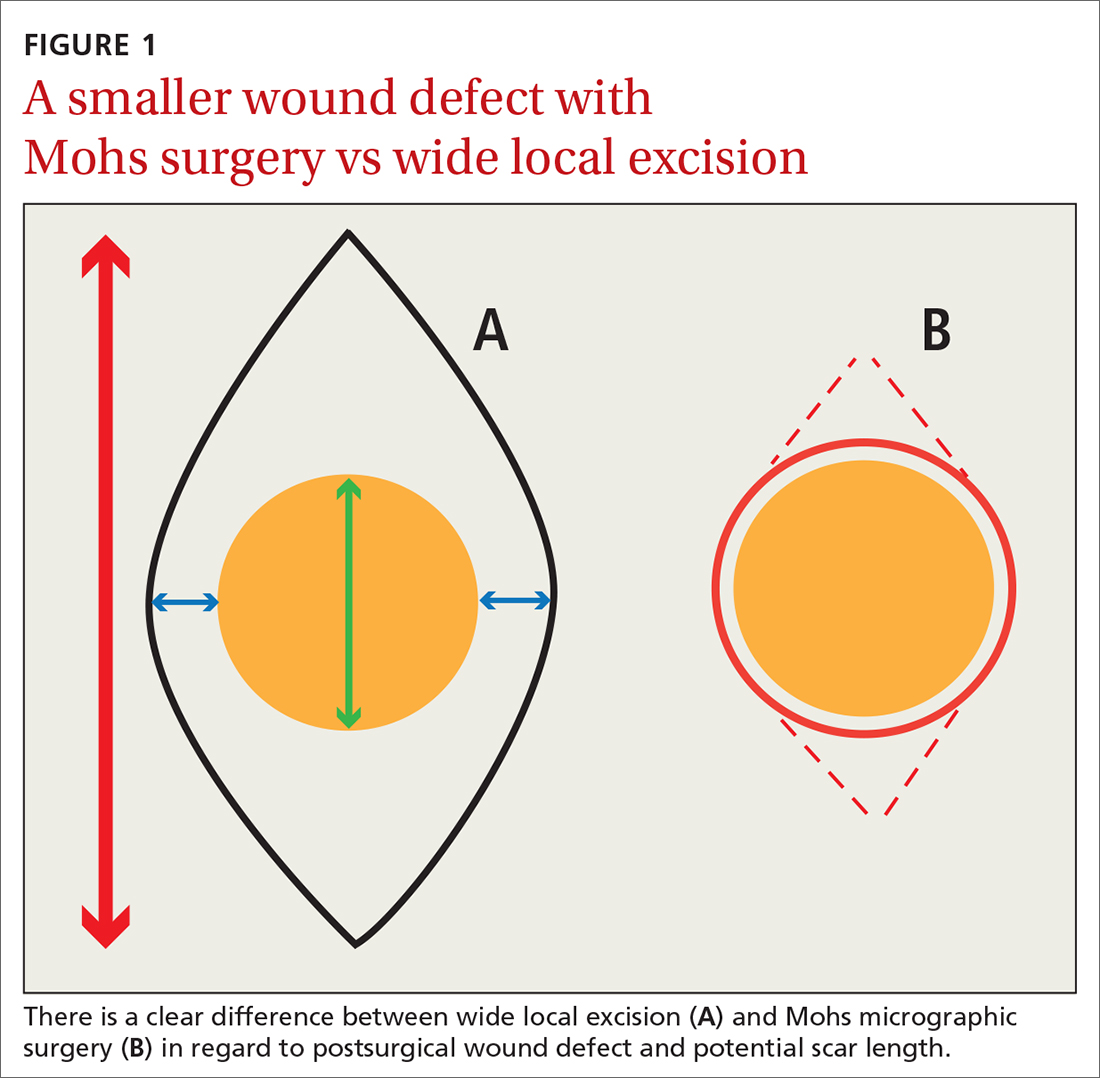

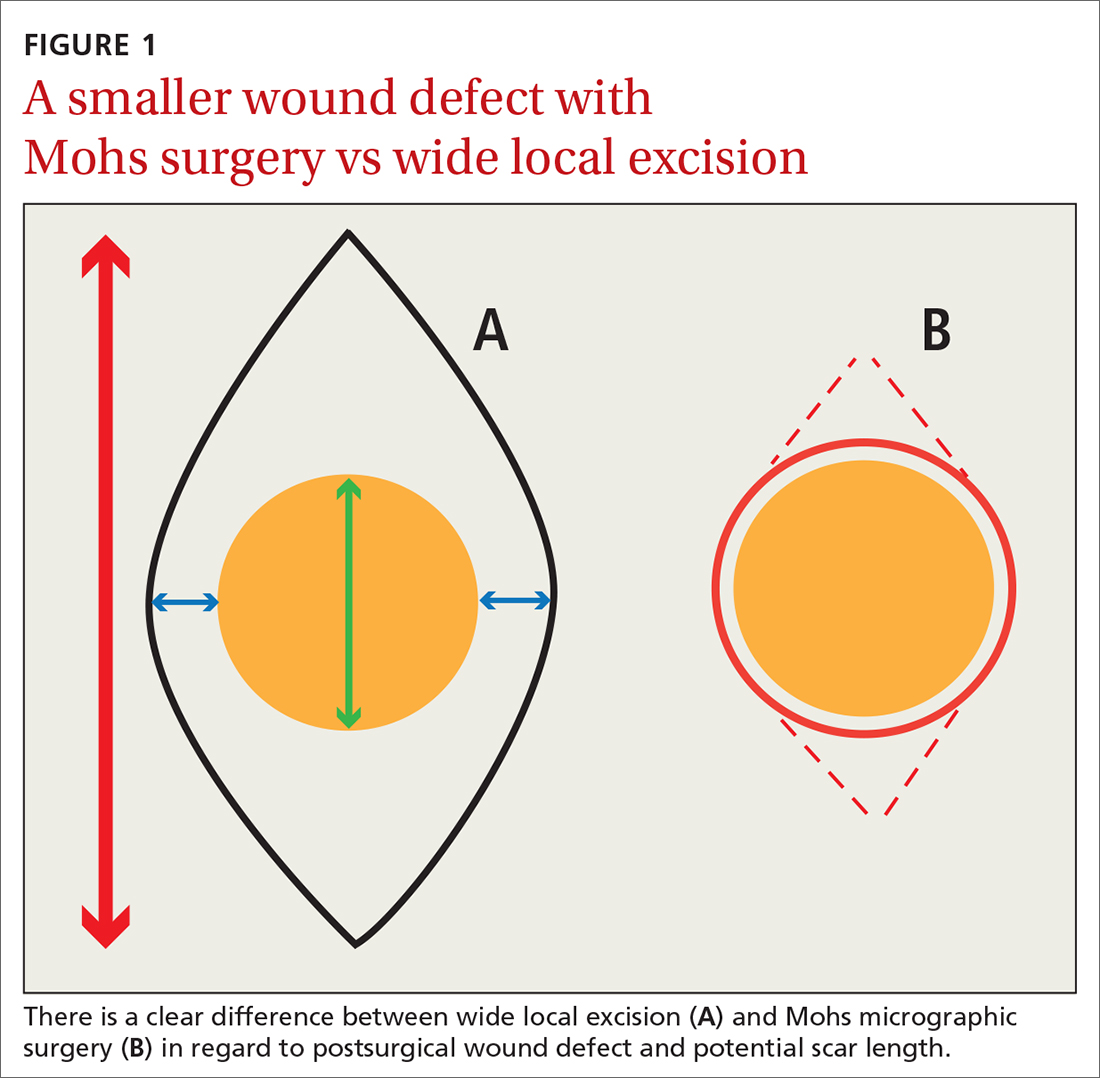

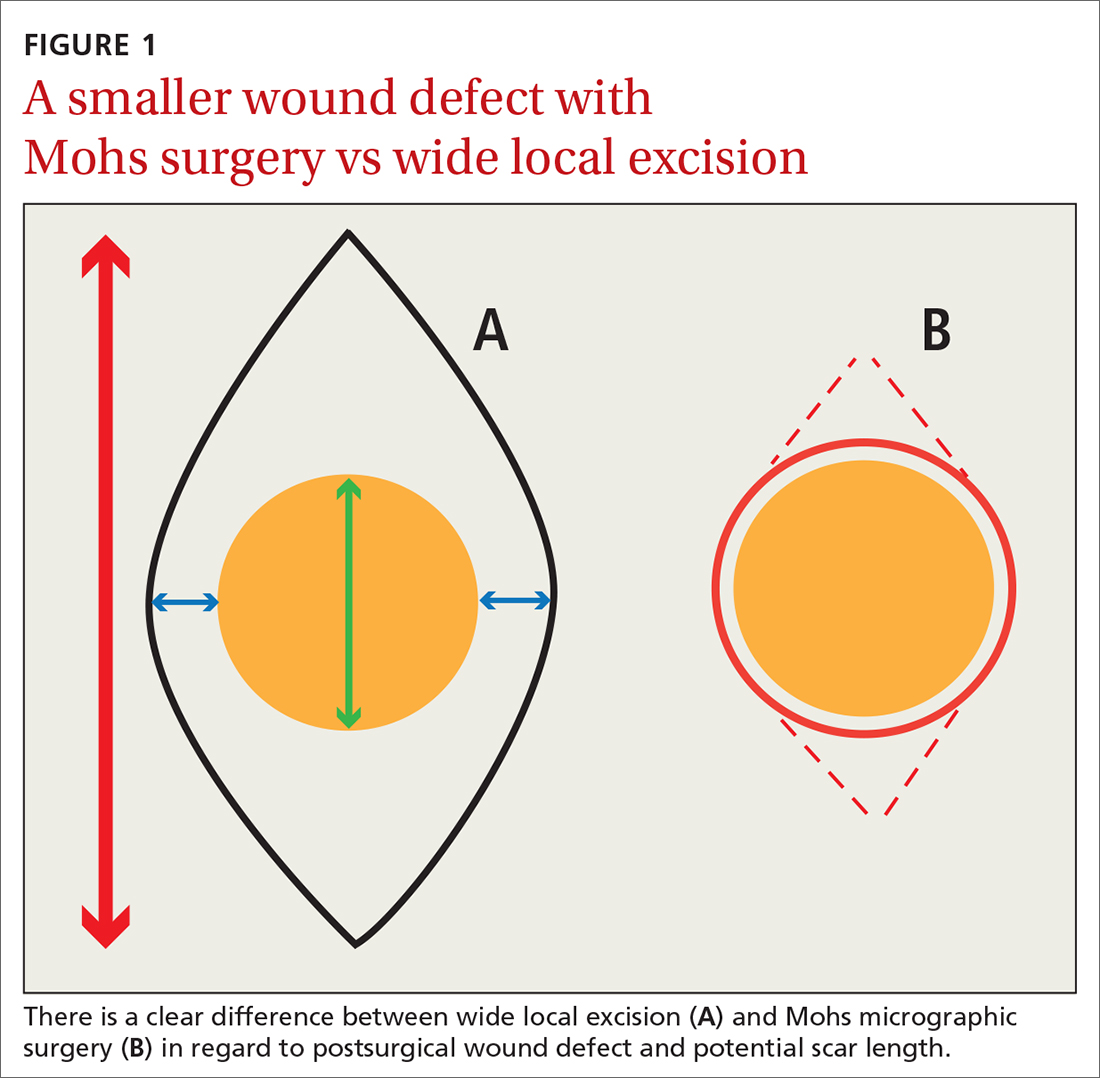

Consider early consultation with a Mohs surgeon for tumor extirpation to keep the defect size as small as possible, as MMS does not require taking margins of healthy surrounding tissue, in contrast to wide local excisions (WLEs; FIGURE 1). A smaller initial incision will result in a smaller scar, which is likely to have better cosmetic outcomes and decreased risk for wound infection.

Continue to: Before consultation...

Before consultation, include a picture of the surgical site with the patient’s referral documentation or have the patient present a photo from his or her phone to the Mohs surgeon. (If a camera or cell phone is not available, triangulation of the site’s location using cosmetic landmarks can be documented in the patient’s chart.)

What the patient can expect during preop visits

During an initial consultation, patients can expect an evaluation by the surgeon that will include more photo taking, a discussion of the surgery, and possibly, performance of an in-clinic biopsy of suspicious lesions. Many practices, including the authors’, use a photo capturing add-on for the EMR in the office.5-7

During the consent process, MMS is described to the patient using lay language and, often, pictorial depictions of the procedure. While explaining that the procedure helps preserve healthy tissue and limit the size of the resulting scar, the surgeon will typically manage the expectations of the patient prior to the first incision. Many clinically small lesions can have significant subclinical extension adjacent to, or on top of, cosmetic landmarks, requiring a flap or graft to close the surgical defect with acceptable cosmetic outcomes.8

One more time. Immediately before surgery, the surgeon will again review the procedure with the patient, using photos of the biopsy site taken during the initial consult, in conjunction with patient verification of the biopsy site, to verify the surgical site and confirm that the patient understands and agrees to the surgery.

A look at how Mohs surgery is performed

MMS typically is performed in the outpatient setting but can also be performed in an operating room or outpatient surgical center. MMS can be performed in a nonsterile procedure room with surgeons and assistants typically utilizing clean, nonsterile gloves, although many Mohs surgeons prefer to perform part, or all, of the technique using sterile gloves.9 A recent systematic review and large meta-analysis showed no significant difference in postsurgical site infections when comparing the use of sterile vs nonsterile gloves.10

Continue to: Prior to initial incision...

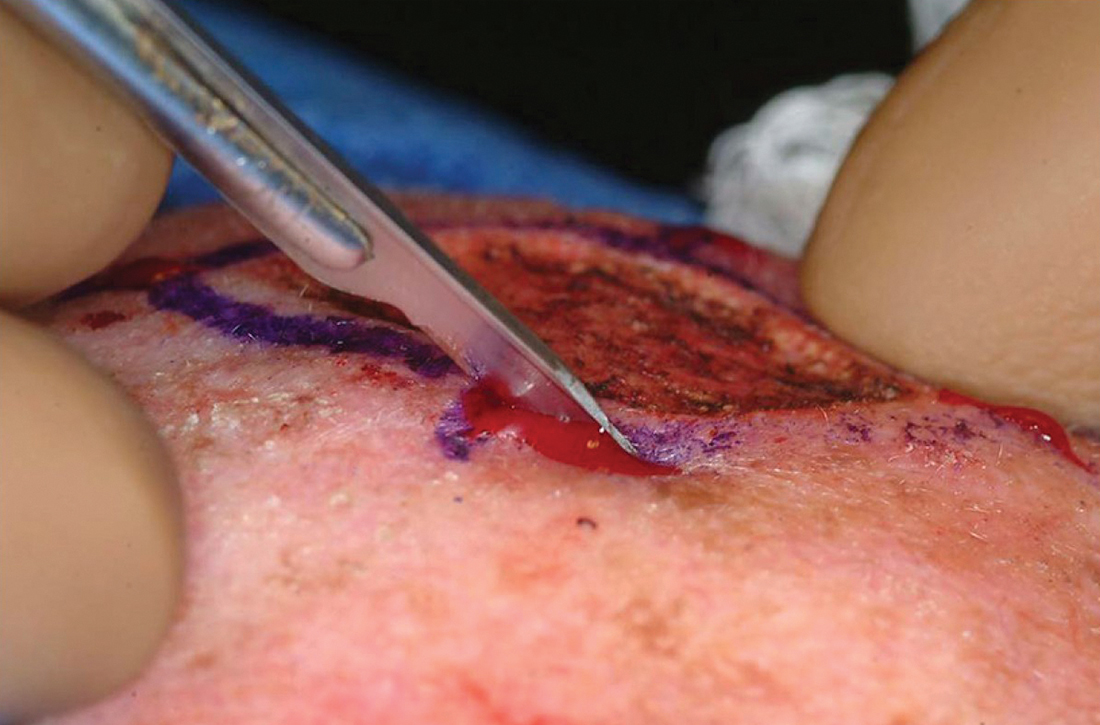

Prior to initial incision, the site is marked with a surgical pen and given 1-mm margins around the clinically visualized lesion. The site is then cleansed with an antiseptic, typically a chlorhexidine solution. Local anesthesia is employed, most commonly with a 1:100,000 lidocaine and epinephrine injection. Marking of the tumor prior to numbing is imperative, as the boundaries of the tumor are typically obscured when the local cutaneous vasculature constricts and causes visualized blanching of adjacent skin. Many Mohs surgeons perform a brief curettage of the lesion with a nondisposable, dull curette to better define the tumor edges and to debulk any obvious exophytic tumor noted by the naked eye.

Prior to the first incision, the surgical site is scored in a variety of ways in order to properly orient the tissue after it has been removed from the patient. Mohs surgeons have differing opinions on how to score and/or mark the tissue, but a common practice is to make a nick at the 12 o’clock position. Following removal of the first stage, the nick will be visible on both the extirpated tissue and the tissue just above the surgical defect. This prevents potential confusion regarding orientation during tissue processing.

The majority of all WLEs are performed utilizing the scalpel blade at an angle 90° perpendicular to the plane of the skin. In MMS, a signature 45° angle with the tip of the scalpel pointing toward, and the handle pointing away from, the lesion is commonly used in order to bevel the tissue being excised (FIGURE 2). Once the tissue is excised, hemostasis is obtained using electrodessication/electrofulguration or electrocoagulation.

Tissue processing and microscopic evaluation

The technique of beveling allows the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue to lie flat on the tissue block, so the Mohs surgeon can evaluate 100% of the excised tissue’s margins. The tissue is transported to a nearby lab for staining and processing. Even if near-perfect beveling is achieved, many stages will require bisecting, quadrissecting, or relaxing cuts in order to allow the margins to lie flat on the tissue block.

Using the scoring system made prior to incision, the tissue is oriented and stained with colored ink. Subsequently, a map is made with sections highlighting the colors used to stain designated areas of the tissue. This step is imperative for orientation during microscopic evaluation. Additionally, the map serves as a guide and log, should a section of the specimen have an involved margin and require another stage.

Continue to: Once fixed to the block...

Once fixed to the block, the tissue is engulfed in appropriate embedding medium and placed within the cryostat. The block is slowly cut to produce several micron-thin wafers of tissue that are then mounted on glass slides and processed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or various stains. The first wafers of tissue that come from the tissue block are those that are closest to the margin that was excised. Thus, 100% of the epidermis and deep margin can be visualized. “Deeper sections” are those that come from deeper cuts within the tissue and are more likely to show the malignant neoplasm.

The evaluation of immediate margins at the very edge of the tissue is in contrast to the technique of “bread-loafing,” which is the standard of evaluating margins after a WLE.11 With this process, the pathologist examines sections that are cut 2- to 4-mm apart. This process only allows the pathologist to examine roughly 1% of the total tissue that was excised, and large variability in cutaneous representation can occur depending on the individual who cuts and processes the tissue.11

Closing the defect

Once the site is deemed clear of residual tumor, the Mohs surgeon approaches the defect and determines the most appropriate way to close the surgical wound. Mohs surgeons are trained to close wounds using a variety of methods, including complex linear closures, flaps, and full-thickness skin grafts. Thoughtful consideration of local anatomy, cosmetic landmarks that may be affected by the closure method, and local tissue laxity are evaluated.

Depending on the location, a secondary intention closure may prove to be just as effective and cosmetically satisfying as a primary intention closure. In light of the many methods of closure, a complex or large surface area defect may better be suited for evaluation and closure by another specialist such as an ENT physician, ophthalmologist, or plastic surgeon.12

Lower recurrence rates for patients who undergo Mohs surgery

As noted earlier, the cutaneous malignancies most commonly treated with MMS are BCCs, followed by SCCs.13 Comparison studies between WLE and MMS show clinically significant differences in terms of recurrence rates between the 2 procedures.

Continue to: For BCCs

For BCCs, recurrence rates for excisions vs MMS are 10% and 1%, respectively.14-16 A randomized trial reviewing 10-year recurrence of primary BCCs on the face showed recurrence rates for MMS of 4.4% compared to 12.2% for WLE.17 This study also showed recurrence rates for recurrent facial BCCs treated with MMS to be 3.9% vs 13.5% for standard WLE.17

SCC. The evidence similarly supports the efficacy of MMS for SCCs. A recent study showed primary T2a tumors had a 1.2% local recurrence rate with Mohs vs a 4% recurrence rate with WLE at an average follow-up of 2.8 years.18 Another study showed that primary tumors that were < 2 cm in diameter had a 5-year cure rate of 99% with Mohs surgery.11

Melanoma in situ. A few studies have shown no clinically significant benefit of MMS compared to WLE when it comes to melanoma in situ.19,20 However, a more recent article by Etzkom et al noted the ability to potentially upstage melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma after reviewing peripheral and deep margins during MMS.21 In this study, the authors uniquely delayed wound closure if upstaging was established and the need for a sentinel lymph node biopsy was warranted. This approach to MMS with delayed closure ultimately paved the way for very low recurrence rates.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andres Garcia, MD, 2612 112th Street, Lubbock, TX 79423; [email protected]

1. Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with Mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

2. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. Published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:748.

3. Cheraghlou S, Christensen S, Agogo G, et al. Comparison of survival after Mohs micrographic surgery vs wide margin excision for early-stage invasive melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1252-1259.

4. Hill D, Kim K, Mansouri B, et al. Quantity and characteristics of flap or graft repairs for skin cancer on the nose or ears: a comparison between Mohs micrographic surgery and plastic surgery. Cutis. 2019;103:284-287.

5. McGinness JL, Goldstein G. The value of preoperative biopsy-site photography for identifying cutaneous lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:194-197.

6. Ke M, Moul D, Camouse M, et al. Where is it? The utility of biopsy-site photography. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:198-202.

7. Nijhawan RI, Lee EH, Nehal KS. Biopsy site selfies—a quality improvement pilot study to assist with correct surgical site identification. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:499-504

8. Breuninger H, Dietz K. Prediction of subclinical tumor infiltration in basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:574-578.

9. Rhinehart BM, Murphy Me, Farley MF, et al. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: infection rate is not affected. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:170-176.

10. Brewer JD, Gonzalez AB, Baum CL, et al. Comparison of sterile vs nonsterile gloves in cutaneous surgery and common outpatient dental procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1008-1014.

11. Shriner DL, McCoy DK, Goldberg DJ, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:79-97.

12. Gladstone HB, Stewart D. An algorithm for the reconstruction of complex facial defects. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:6-9.

13. Robinson JK. Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:149-156.

14. Swanson NA. Mohs surgery. Technique, indications, applications, and the future. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:761-773.

15. Robins P. Chemosurgery: my 15 years of experience. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:779-789.

16. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-328.

17. van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

18. Xiong DD, Beal BT, Varra V, et al. Outcomes in intermediate-risk squamous cell carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82: 1195-1204.

19. Trofymenko O, Bordeaux JS, Zeitouni NC. Melanoma of the face and Mohs micrographic surgery: nationwide mortality data analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:481-492.

20. Nosrati A, Berliner JG, Goel S, et al. Outcomes of melanoma in situ treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:436-441.

21. Etzkom JR, Sobanko JF, Elenitsas R, et al. Low recurrences for in situ and invasive melanomas using Mohs micrographic surgery with melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1) immunostaining: tissue processing methodology to optimize pathologic and margin assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:840-850.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a unique dermatologic surgery technique that allows the dermatologist to fill the concomitant roles of surgeon and pathologist. It is utilized for the extirpation of skin malignancy, with an emphasis on tissue preservation and immediate surgical margin evaluation. In MMS, the Mohs surgeon acts as the surgeon for physical removal of the lesion and the pathologist during evaluation of frozen section margins.1

Primary care providers (PCPs) are on the frontlines of management of cutaneous malignancy. Whether referring to Dermatology for biopsy or performing a biopsy themselves, PCPs can assure optimal treatment outcomes by guiding patients to evidence-based treatments, while still respecting the patient’s wishes. In this evidence-based review of the advantages, improved outcomes, and safety of Mohs surgery for the treatment of common and rare skin neoplasms, we provide our primary care colleagues with information on the indications, process (the order in which steps of the procedure are performed), and techniques used for treating cutaneous malignancies with Mohs surgery.

When is Mohs surgery appropriate?

MMS has typically been reserved for treatment of cutaneous malignancy in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue preservation is key. In 2012, Connolly et al released appropriate use criteria (AUC) for MMS.2 (See “An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery.”) Within the AUC, there are 4 major qualitative and quantitative categories when considering referral for MMS:

- area of the body in which the lesion manifests

- the patient’s medical characteristics

- tumor characteristics

- the size of the lesion to be treated.2

Areas of the body are divided into 3 categories by the AUC according to how challenging tumor extirpation is expected to be and how critical tissue preservation is. Areas termed “H” receive the highest score for appropriate Mohs usage, followed by areas “M” and “L.”

SIDEBAR

An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery

“Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria” is a free and easy-to-use smartphone application to help determine whether Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is appropriate for a particular patient. Clinicians can enter the details of a recent skin cancer biopsy along with patient information into the app and it will calculate a score automatically categorized into 1 of 3 categories: “appropriate,” “uncertain,” and “not appropriate” for MMS. The clinician can then talk to the patient about a possible referral to a Mohs surgeon, depending on the appropriateness of the procedure for the patient and their tumor.

Patient medical characteristics that should be taken into account when referring for Mohs surgery are the patient’s immune status, genetic syndromes that may predispose the patient to cutaneous malignancies (eg, xeroderma pigmentosa), history of radiation to the area of involvement, and the patient’s history of aggressive cutaneous malignancies.

Tumor characteristics. The most common malignancies treated with MMS include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These malignancies are further delineated through histologic evaluation by a pathologist or dermatopathologist. Aggressive features of a BCC on any area of the body that warrant referral to a Mohs surgeon include morpheaform/fibrosing/sclerosing histologic findings, as well as micronodular architecture and perineural invasion. Concerning histologic SCC findings that warrant Mohs surgery through the AUC include sclerosing, basosquamous, and small cell histology, as well as poorly differentiated and/or undifferentiated SCC.

Melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna, which are variants of melanoma limited to the epidermis without invasion into the underlying dermis, are included within the AUC for MMS. For invasive melanoma (melanoma that has invaded into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue), MMS has been shown to have marginal benefit but currently is not included within the AUC.3

Continue to: Due to excellent margin control...

Due to excellent margin control via immediate microscopic evaluation of surgical margins, MMS is an appropriate treatment choice and indicated for many more uncommon cutaneous malignancies, including sebaceous and mucinous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, atypical fibroxanthoma, angiosarcoma, and other more rarely encountered clinical malignancies.2

Tumor size. When considering a referral to MMS for cancer extirpation, the size of the tumor does play a role; however, size depends on the type of tumor as well as the location on the body. In general, most skin cancers of any size on the face, perianal area, genitalia, nipples, hands, feet and ankles, or pretibial surface are appropriate for Mohs surgery. Skin cancers on the trunk and extremities are also appropriate if they are above a certain size specified by the AUC. Tumor type and whether they are recurrences also factor into the equation.

Who will do the procedure?

A recent review showed that PCPs were more likely to refer patients to plastic surgery rather than Mohs surgery for skin cancer removal, especially among younger female patients.4 This is likely because of the perception that plastic surgeons do more complex closures and have more experience removing difficult cancers. Interestingly, this same study showed that Mohs surgeons may actually be doing several-fold more complex closures (flaps and grafts) on the nose and ears than plastic surgeons at similar practice settings.4

Aside from Mohs surgeons doing more closures, perhaps the biggest difference between Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons is the pathology training of the Mohs surgeon. Mohs surgeons evaluate 100% of the tissue margins at the time of the procedure to both ensure complete tumor removal and to preserve as much tumor-free skin as possible, ultimately resulting in decreased recurrences and smaller scars. In contrast, the plastic surgeon’s rigorous training typically does not include extensive dermatopathology training, particularly the pathology of cutaneous neoplasms. Plastic surgeons will often send pathologic specimens for evaluation, meaning patients have to wait for outside histologic confirmation before their wounds can be closed. Additionally, the histologic evaluation is often not a full-margin assessment, as not all labs are equipped for this technique.

Consider early consultation with a Mohs surgeon for tumor extirpation to keep the defect size as small as possible, as MMS does not require taking margins of healthy surrounding tissue, in contrast to wide local excisions (WLEs; FIGURE 1). A smaller initial incision will result in a smaller scar, which is likely to have better cosmetic outcomes and decreased risk for wound infection.

Continue to: Before consultation...

Before consultation, include a picture of the surgical site with the patient’s referral documentation or have the patient present a photo from his or her phone to the Mohs surgeon. (If a camera or cell phone is not available, triangulation of the site’s location using cosmetic landmarks can be documented in the patient’s chart.)

What the patient can expect during preop visits

During an initial consultation, patients can expect an evaluation by the surgeon that will include more photo taking, a discussion of the surgery, and possibly, performance of an in-clinic biopsy of suspicious lesions. Many practices, including the authors’, use a photo capturing add-on for the EMR in the office.5-7

During the consent process, MMS is described to the patient using lay language and, often, pictorial depictions of the procedure. While explaining that the procedure helps preserve healthy tissue and limit the size of the resulting scar, the surgeon will typically manage the expectations of the patient prior to the first incision. Many clinically small lesions can have significant subclinical extension adjacent to, or on top of, cosmetic landmarks, requiring a flap or graft to close the surgical defect with acceptable cosmetic outcomes.8

One more time. Immediately before surgery, the surgeon will again review the procedure with the patient, using photos of the biopsy site taken during the initial consult, in conjunction with patient verification of the biopsy site, to verify the surgical site and confirm that the patient understands and agrees to the surgery.

A look at how Mohs surgery is performed

MMS typically is performed in the outpatient setting but can also be performed in an operating room or outpatient surgical center. MMS can be performed in a nonsterile procedure room with surgeons and assistants typically utilizing clean, nonsterile gloves, although many Mohs surgeons prefer to perform part, or all, of the technique using sterile gloves.9 A recent systematic review and large meta-analysis showed no significant difference in postsurgical site infections when comparing the use of sterile vs nonsterile gloves.10

Continue to: Prior to initial incision...

Prior to initial incision, the site is marked with a surgical pen and given 1-mm margins around the clinically visualized lesion. The site is then cleansed with an antiseptic, typically a chlorhexidine solution. Local anesthesia is employed, most commonly with a 1:100,000 lidocaine and epinephrine injection. Marking of the tumor prior to numbing is imperative, as the boundaries of the tumor are typically obscured when the local cutaneous vasculature constricts and causes visualized blanching of adjacent skin. Many Mohs surgeons perform a brief curettage of the lesion with a nondisposable, dull curette to better define the tumor edges and to debulk any obvious exophytic tumor noted by the naked eye.

Prior to the first incision, the surgical site is scored in a variety of ways in order to properly orient the tissue after it has been removed from the patient. Mohs surgeons have differing opinions on how to score and/or mark the tissue, but a common practice is to make a nick at the 12 o’clock position. Following removal of the first stage, the nick will be visible on both the extirpated tissue and the tissue just above the surgical defect. This prevents potential confusion regarding orientation during tissue processing.

The majority of all WLEs are performed utilizing the scalpel blade at an angle 90° perpendicular to the plane of the skin. In MMS, a signature 45° angle with the tip of the scalpel pointing toward, and the handle pointing away from, the lesion is commonly used in order to bevel the tissue being excised (FIGURE 2). Once the tissue is excised, hemostasis is obtained using electrodessication/electrofulguration or electrocoagulation.

Tissue processing and microscopic evaluation

The technique of beveling allows the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue to lie flat on the tissue block, so the Mohs surgeon can evaluate 100% of the excised tissue’s margins. The tissue is transported to a nearby lab for staining and processing. Even if near-perfect beveling is achieved, many stages will require bisecting, quadrissecting, or relaxing cuts in order to allow the margins to lie flat on the tissue block.

Using the scoring system made prior to incision, the tissue is oriented and stained with colored ink. Subsequently, a map is made with sections highlighting the colors used to stain designated areas of the tissue. This step is imperative for orientation during microscopic evaluation. Additionally, the map serves as a guide and log, should a section of the specimen have an involved margin and require another stage.

Continue to: Once fixed to the block...

Once fixed to the block, the tissue is engulfed in appropriate embedding medium and placed within the cryostat. The block is slowly cut to produce several micron-thin wafers of tissue that are then mounted on glass slides and processed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or various stains. The first wafers of tissue that come from the tissue block are those that are closest to the margin that was excised. Thus, 100% of the epidermis and deep margin can be visualized. “Deeper sections” are those that come from deeper cuts within the tissue and are more likely to show the malignant neoplasm.

The evaluation of immediate margins at the very edge of the tissue is in contrast to the technique of “bread-loafing,” which is the standard of evaluating margins after a WLE.11 With this process, the pathologist examines sections that are cut 2- to 4-mm apart. This process only allows the pathologist to examine roughly 1% of the total tissue that was excised, and large variability in cutaneous representation can occur depending on the individual who cuts and processes the tissue.11

Closing the defect

Once the site is deemed clear of residual tumor, the Mohs surgeon approaches the defect and determines the most appropriate way to close the surgical wound. Mohs surgeons are trained to close wounds using a variety of methods, including complex linear closures, flaps, and full-thickness skin grafts. Thoughtful consideration of local anatomy, cosmetic landmarks that may be affected by the closure method, and local tissue laxity are evaluated.

Depending on the location, a secondary intention closure may prove to be just as effective and cosmetically satisfying as a primary intention closure. In light of the many methods of closure, a complex or large surface area defect may better be suited for evaluation and closure by another specialist such as an ENT physician, ophthalmologist, or plastic surgeon.12

Lower recurrence rates for patients who undergo Mohs surgery

As noted earlier, the cutaneous malignancies most commonly treated with MMS are BCCs, followed by SCCs.13 Comparison studies between WLE and MMS show clinically significant differences in terms of recurrence rates between the 2 procedures.

Continue to: For BCCs

For BCCs, recurrence rates for excisions vs MMS are 10% and 1%, respectively.14-16 A randomized trial reviewing 10-year recurrence of primary BCCs on the face showed recurrence rates for MMS of 4.4% compared to 12.2% for WLE.17 This study also showed recurrence rates for recurrent facial BCCs treated with MMS to be 3.9% vs 13.5% for standard WLE.17

SCC. The evidence similarly supports the efficacy of MMS for SCCs. A recent study showed primary T2a tumors had a 1.2% local recurrence rate with Mohs vs a 4% recurrence rate with WLE at an average follow-up of 2.8 years.18 Another study showed that primary tumors that were < 2 cm in diameter had a 5-year cure rate of 99% with Mohs surgery.11

Melanoma in situ. A few studies have shown no clinically significant benefit of MMS compared to WLE when it comes to melanoma in situ.19,20 However, a more recent article by Etzkom et al noted the ability to potentially upstage melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma after reviewing peripheral and deep margins during MMS.21 In this study, the authors uniquely delayed wound closure if upstaging was established and the need for a sentinel lymph node biopsy was warranted. This approach to MMS with delayed closure ultimately paved the way for very low recurrence rates.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andres Garcia, MD, 2612 112th Street, Lubbock, TX 79423; [email protected]

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a unique dermatologic surgery technique that allows the dermatologist to fill the concomitant roles of surgeon and pathologist. It is utilized for the extirpation of skin malignancy, with an emphasis on tissue preservation and immediate surgical margin evaluation. In MMS, the Mohs surgeon acts as the surgeon for physical removal of the lesion and the pathologist during evaluation of frozen section margins.1

Primary care providers (PCPs) are on the frontlines of management of cutaneous malignancy. Whether referring to Dermatology for biopsy or performing a biopsy themselves, PCPs can assure optimal treatment outcomes by guiding patients to evidence-based treatments, while still respecting the patient’s wishes. In this evidence-based review of the advantages, improved outcomes, and safety of Mohs surgery for the treatment of common and rare skin neoplasms, we provide our primary care colleagues with information on the indications, process (the order in which steps of the procedure are performed), and techniques used for treating cutaneous malignancies with Mohs surgery.

When is Mohs surgery appropriate?

MMS has typically been reserved for treatment of cutaneous malignancy in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue preservation is key. In 2012, Connolly et al released appropriate use criteria (AUC) for MMS.2 (See “An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery.”) Within the AUC, there are 4 major qualitative and quantitative categories when considering referral for MMS:

- area of the body in which the lesion manifests

- the patient’s medical characteristics

- tumor characteristics

- the size of the lesion to be treated.2

Areas of the body are divided into 3 categories by the AUC according to how challenging tumor extirpation is expected to be and how critical tissue preservation is. Areas termed “H” receive the highest score for appropriate Mohs usage, followed by areas “M” and “L.”

SIDEBAR

An app that helps clinicians apply the criteria for Mohs surgery

“Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria” is a free and easy-to-use smartphone application to help determine whether Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is appropriate for a particular patient. Clinicians can enter the details of a recent skin cancer biopsy along with patient information into the app and it will calculate a score automatically categorized into 1 of 3 categories: “appropriate,” “uncertain,” and “not appropriate” for MMS. The clinician can then talk to the patient about a possible referral to a Mohs surgeon, depending on the appropriateness of the procedure for the patient and their tumor.

Patient medical characteristics that should be taken into account when referring for Mohs surgery are the patient’s immune status, genetic syndromes that may predispose the patient to cutaneous malignancies (eg, xeroderma pigmentosa), history of radiation to the area of involvement, and the patient’s history of aggressive cutaneous malignancies.

Tumor characteristics. The most common malignancies treated with MMS include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These malignancies are further delineated through histologic evaluation by a pathologist or dermatopathologist. Aggressive features of a BCC on any area of the body that warrant referral to a Mohs surgeon include morpheaform/fibrosing/sclerosing histologic findings, as well as micronodular architecture and perineural invasion. Concerning histologic SCC findings that warrant Mohs surgery through the AUC include sclerosing, basosquamous, and small cell histology, as well as poorly differentiated and/or undifferentiated SCC.

Melanoma in situ and lentigo maligna, which are variants of melanoma limited to the epidermis without invasion into the underlying dermis, are included within the AUC for MMS. For invasive melanoma (melanoma that has invaded into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue), MMS has been shown to have marginal benefit but currently is not included within the AUC.3

Continue to: Due to excellent margin control...

Due to excellent margin control via immediate microscopic evaluation of surgical margins, MMS is an appropriate treatment choice and indicated for many more uncommon cutaneous malignancies, including sebaceous and mucinous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, atypical fibroxanthoma, angiosarcoma, and other more rarely encountered clinical malignancies.2

Tumor size. When considering a referral to MMS for cancer extirpation, the size of the tumor does play a role; however, size depends on the type of tumor as well as the location on the body. In general, most skin cancers of any size on the face, perianal area, genitalia, nipples, hands, feet and ankles, or pretibial surface are appropriate for Mohs surgery. Skin cancers on the trunk and extremities are also appropriate if they are above a certain size specified by the AUC. Tumor type and whether they are recurrences also factor into the equation.

Who will do the procedure?

A recent review showed that PCPs were more likely to refer patients to plastic surgery rather than Mohs surgery for skin cancer removal, especially among younger female patients.4 This is likely because of the perception that plastic surgeons do more complex closures and have more experience removing difficult cancers. Interestingly, this same study showed that Mohs surgeons may actually be doing several-fold more complex closures (flaps and grafts) on the nose and ears than plastic surgeons at similar practice settings.4

Aside from Mohs surgeons doing more closures, perhaps the biggest difference between Mohs surgeons and plastic surgeons is the pathology training of the Mohs surgeon. Mohs surgeons evaluate 100% of the tissue margins at the time of the procedure to both ensure complete tumor removal and to preserve as much tumor-free skin as possible, ultimately resulting in decreased recurrences and smaller scars. In contrast, the plastic surgeon’s rigorous training typically does not include extensive dermatopathology training, particularly the pathology of cutaneous neoplasms. Plastic surgeons will often send pathologic specimens for evaluation, meaning patients have to wait for outside histologic confirmation before their wounds can be closed. Additionally, the histologic evaluation is often not a full-margin assessment, as not all labs are equipped for this technique.

Consider early consultation with a Mohs surgeon for tumor extirpation to keep the defect size as small as possible, as MMS does not require taking margins of healthy surrounding tissue, in contrast to wide local excisions (WLEs; FIGURE 1). A smaller initial incision will result in a smaller scar, which is likely to have better cosmetic outcomes and decreased risk for wound infection.

Continue to: Before consultation...

Before consultation, include a picture of the surgical site with the patient’s referral documentation or have the patient present a photo from his or her phone to the Mohs surgeon. (If a camera or cell phone is not available, triangulation of the site’s location using cosmetic landmarks can be documented in the patient’s chart.)

What the patient can expect during preop visits

During an initial consultation, patients can expect an evaluation by the surgeon that will include more photo taking, a discussion of the surgery, and possibly, performance of an in-clinic biopsy of suspicious lesions. Many practices, including the authors’, use a photo capturing add-on for the EMR in the office.5-7

During the consent process, MMS is described to the patient using lay language and, often, pictorial depictions of the procedure. While explaining that the procedure helps preserve healthy tissue and limit the size of the resulting scar, the surgeon will typically manage the expectations of the patient prior to the first incision. Many clinically small lesions can have significant subclinical extension adjacent to, or on top of, cosmetic landmarks, requiring a flap or graft to close the surgical defect with acceptable cosmetic outcomes.8

One more time. Immediately before surgery, the surgeon will again review the procedure with the patient, using photos of the biopsy site taken during the initial consult, in conjunction with patient verification of the biopsy site, to verify the surgical site and confirm that the patient understands and agrees to the surgery.

A look at how Mohs surgery is performed

MMS typically is performed in the outpatient setting but can also be performed in an operating room or outpatient surgical center. MMS can be performed in a nonsterile procedure room with surgeons and assistants typically utilizing clean, nonsterile gloves, although many Mohs surgeons prefer to perform part, or all, of the technique using sterile gloves.9 A recent systematic review and large meta-analysis showed no significant difference in postsurgical site infections when comparing the use of sterile vs nonsterile gloves.10

Continue to: Prior to initial incision...

Prior to initial incision, the site is marked with a surgical pen and given 1-mm margins around the clinically visualized lesion. The site is then cleansed with an antiseptic, typically a chlorhexidine solution. Local anesthesia is employed, most commonly with a 1:100,000 lidocaine and epinephrine injection. Marking of the tumor prior to numbing is imperative, as the boundaries of the tumor are typically obscured when the local cutaneous vasculature constricts and causes visualized blanching of adjacent skin. Many Mohs surgeons perform a brief curettage of the lesion with a nondisposable, dull curette to better define the tumor edges and to debulk any obvious exophytic tumor noted by the naked eye.

Prior to the first incision, the surgical site is scored in a variety of ways in order to properly orient the tissue after it has been removed from the patient. Mohs surgeons have differing opinions on how to score and/or mark the tissue, but a common practice is to make a nick at the 12 o’clock position. Following removal of the first stage, the nick will be visible on both the extirpated tissue and the tissue just above the surgical defect. This prevents potential confusion regarding orientation during tissue processing.

The majority of all WLEs are performed utilizing the scalpel blade at an angle 90° perpendicular to the plane of the skin. In MMS, a signature 45° angle with the tip of the scalpel pointing toward, and the handle pointing away from, the lesion is commonly used in order to bevel the tissue being excised (FIGURE 2). Once the tissue is excised, hemostasis is obtained using electrodessication/electrofulguration or electrocoagulation.

Tissue processing and microscopic evaluation

The technique of beveling allows the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue to lie flat on the tissue block, so the Mohs surgeon can evaluate 100% of the excised tissue’s margins. The tissue is transported to a nearby lab for staining and processing. Even if near-perfect beveling is achieved, many stages will require bisecting, quadrissecting, or relaxing cuts in order to allow the margins to lie flat on the tissue block.

Using the scoring system made prior to incision, the tissue is oriented and stained with colored ink. Subsequently, a map is made with sections highlighting the colors used to stain designated areas of the tissue. This step is imperative for orientation during microscopic evaluation. Additionally, the map serves as a guide and log, should a section of the specimen have an involved margin and require another stage.

Continue to: Once fixed to the block...

Once fixed to the block, the tissue is engulfed in appropriate embedding medium and placed within the cryostat. The block is slowly cut to produce several micron-thin wafers of tissue that are then mounted on glass slides and processed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or various stains. The first wafers of tissue that come from the tissue block are those that are closest to the margin that was excised. Thus, 100% of the epidermis and deep margin can be visualized. “Deeper sections” are those that come from deeper cuts within the tissue and are more likely to show the malignant neoplasm.

The evaluation of immediate margins at the very edge of the tissue is in contrast to the technique of “bread-loafing,” which is the standard of evaluating margins after a WLE.11 With this process, the pathologist examines sections that are cut 2- to 4-mm apart. This process only allows the pathologist to examine roughly 1% of the total tissue that was excised, and large variability in cutaneous representation can occur depending on the individual who cuts and processes the tissue.11

Closing the defect

Once the site is deemed clear of residual tumor, the Mohs surgeon approaches the defect and determines the most appropriate way to close the surgical wound. Mohs surgeons are trained to close wounds using a variety of methods, including complex linear closures, flaps, and full-thickness skin grafts. Thoughtful consideration of local anatomy, cosmetic landmarks that may be affected by the closure method, and local tissue laxity are evaluated.

Depending on the location, a secondary intention closure may prove to be just as effective and cosmetically satisfying as a primary intention closure. In light of the many methods of closure, a complex or large surface area defect may better be suited for evaluation and closure by another specialist such as an ENT physician, ophthalmologist, or plastic surgeon.12

Lower recurrence rates for patients who undergo Mohs surgery

As noted earlier, the cutaneous malignancies most commonly treated with MMS are BCCs, followed by SCCs.13 Comparison studies between WLE and MMS show clinically significant differences in terms of recurrence rates between the 2 procedures.

Continue to: For BCCs

For BCCs, recurrence rates for excisions vs MMS are 10% and 1%, respectively.14-16 A randomized trial reviewing 10-year recurrence of primary BCCs on the face showed recurrence rates for MMS of 4.4% compared to 12.2% for WLE.17 This study also showed recurrence rates for recurrent facial BCCs treated with MMS to be 3.9% vs 13.5% for standard WLE.17

SCC. The evidence similarly supports the efficacy of MMS for SCCs. A recent study showed primary T2a tumors had a 1.2% local recurrence rate with Mohs vs a 4% recurrence rate with WLE at an average follow-up of 2.8 years.18 Another study showed that primary tumors that were < 2 cm in diameter had a 5-year cure rate of 99% with Mohs surgery.11

Melanoma in situ. A few studies have shown no clinically significant benefit of MMS compared to WLE when it comes to melanoma in situ.19,20 However, a more recent article by Etzkom et al noted the ability to potentially upstage melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma after reviewing peripheral and deep margins during MMS.21 In this study, the authors uniquely delayed wound closure if upstaging was established and the need for a sentinel lymph node biopsy was warranted. This approach to MMS with delayed closure ultimately paved the way for very low recurrence rates.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andres Garcia, MD, 2612 112th Street, Lubbock, TX 79423; [email protected]

1. Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with Mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

2. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. Published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:748.

3. Cheraghlou S, Christensen S, Agogo G, et al. Comparison of survival after Mohs micrographic surgery vs wide margin excision for early-stage invasive melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1252-1259.

4. Hill D, Kim K, Mansouri B, et al. Quantity and characteristics of flap or graft repairs for skin cancer on the nose or ears: a comparison between Mohs micrographic surgery and plastic surgery. Cutis. 2019;103:284-287.

5. McGinness JL, Goldstein G. The value of preoperative biopsy-site photography for identifying cutaneous lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:194-197.

6. Ke M, Moul D, Camouse M, et al. Where is it? The utility of biopsy-site photography. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:198-202.

7. Nijhawan RI, Lee EH, Nehal KS. Biopsy site selfies—a quality improvement pilot study to assist with correct surgical site identification. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:499-504

8. Breuninger H, Dietz K. Prediction of subclinical tumor infiltration in basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:574-578.

9. Rhinehart BM, Murphy Me, Farley MF, et al. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: infection rate is not affected. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:170-176.

10. Brewer JD, Gonzalez AB, Baum CL, et al. Comparison of sterile vs nonsterile gloves in cutaneous surgery and common outpatient dental procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1008-1014.

11. Shriner DL, McCoy DK, Goldberg DJ, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:79-97.

12. Gladstone HB, Stewart D. An algorithm for the reconstruction of complex facial defects. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:6-9.

13. Robinson JK. Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:149-156.

14. Swanson NA. Mohs surgery. Technique, indications, applications, and the future. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:761-773.

15. Robins P. Chemosurgery: my 15 years of experience. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:779-789.

16. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-328.

17. van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

18. Xiong DD, Beal BT, Varra V, et al. Outcomes in intermediate-risk squamous cell carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82: 1195-1204.

19. Trofymenko O, Bordeaux JS, Zeitouni NC. Melanoma of the face and Mohs micrographic surgery: nationwide mortality data analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:481-492.

20. Nosrati A, Berliner JG, Goel S, et al. Outcomes of melanoma in situ treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:436-441.

21. Etzkom JR, Sobanko JF, Elenitsas R, et al. Low recurrences for in situ and invasive melanomas using Mohs micrographic surgery with melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1) immunostaining: tissue processing methodology to optimize pathologic and margin assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:840-850.

1. Dim-Jamora KC, Perone JB. Management of cutaneous tumors with Mohs micrographic surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22:247-256.

2. Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. Published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:748.

3. Cheraghlou S, Christensen S, Agogo G, et al. Comparison of survival after Mohs micrographic surgery vs wide margin excision for early-stage invasive melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1252-1259.

4. Hill D, Kim K, Mansouri B, et al. Quantity and characteristics of flap or graft repairs for skin cancer on the nose or ears: a comparison between Mohs micrographic surgery and plastic surgery. Cutis. 2019;103:284-287.

5. McGinness JL, Goldstein G. The value of preoperative biopsy-site photography for identifying cutaneous lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:194-197.

6. Ke M, Moul D, Camouse M, et al. Where is it? The utility of biopsy-site photography. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:198-202.

7. Nijhawan RI, Lee EH, Nehal KS. Biopsy site selfies—a quality improvement pilot study to assist with correct surgical site identification. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:499-504

8. Breuninger H, Dietz K. Prediction of subclinical tumor infiltration in basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:574-578.

9. Rhinehart BM, Murphy Me, Farley MF, et al. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: infection rate is not affected. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:170-176.

10. Brewer JD, Gonzalez AB, Baum CL, et al. Comparison of sterile vs nonsterile gloves in cutaneous surgery and common outpatient dental procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1008-1014.

11. Shriner DL, McCoy DK, Goldberg DJ, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:79-97.

12. Gladstone HB, Stewart D. An algorithm for the reconstruction of complex facial defects. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007;12:6-9.

13. Robinson JK. Mohs micrographic surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:149-156.

14. Swanson NA. Mohs surgery. Technique, indications, applications, and the future. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:761-773.

15. Robins P. Chemosurgery: my 15 years of experience. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:779-789.

16. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-328.

17. van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

18. Xiong DD, Beal BT, Varra V, et al. Outcomes in intermediate-risk squamous cell carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82: 1195-1204.

19. Trofymenko O, Bordeaux JS, Zeitouni NC. Melanoma of the face and Mohs micrographic surgery: nationwide mortality data analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:481-492.

20. Nosrati A, Berliner JG, Goel S, et al. Outcomes of melanoma in situ treated with Mohs micrographic surgery compared with wide local excision. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:436-441.

21. Etzkom JR, Sobanko JF, Elenitsas R, et al. Low recurrences for in situ and invasive melanomas using Mohs micrographic surgery with melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1) immunostaining: tissue processing methodology to optimize pathologic and margin assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:840-850.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider Mohs surgery for patients who have lesions located mainly in regions of the face that make excision difficult without significant scarring. A

› Consider Mohs surgery for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma that typically involve (but are not necessarily limited to) the face, as the procedure significantly reduces recurrence rates and leads to cure rates of up to 99%. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis Mimicking Livedo Racemosa

To the Editor:

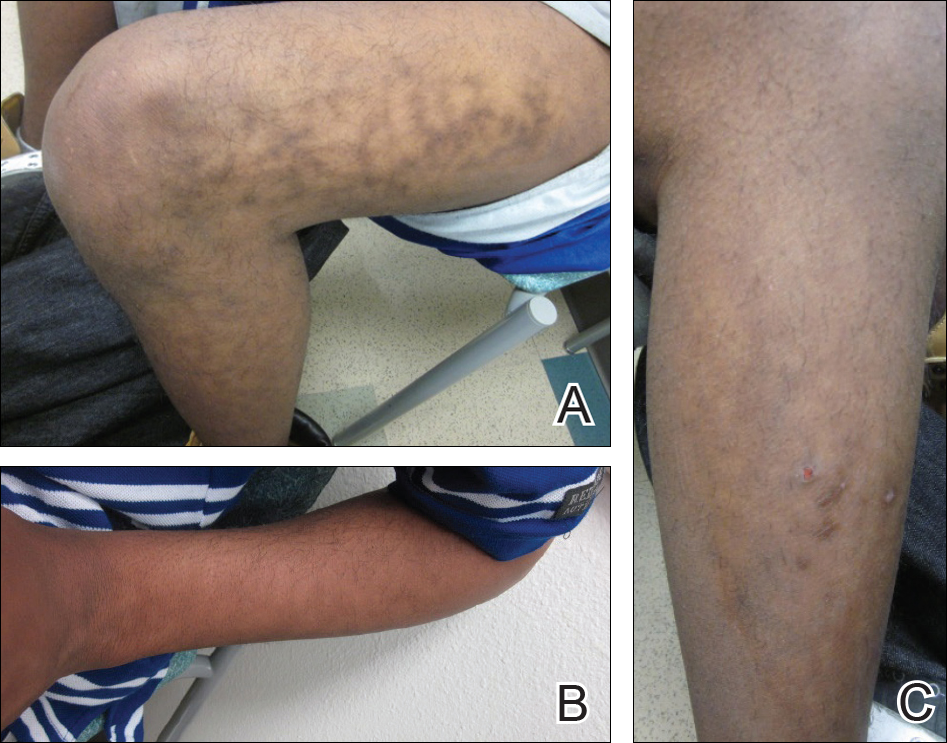

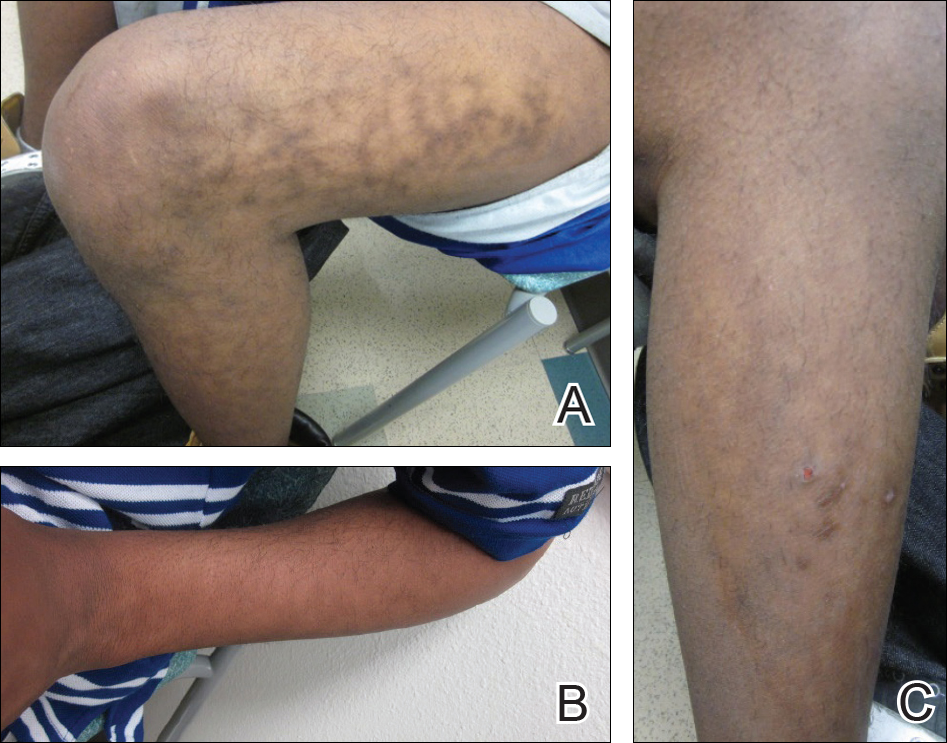

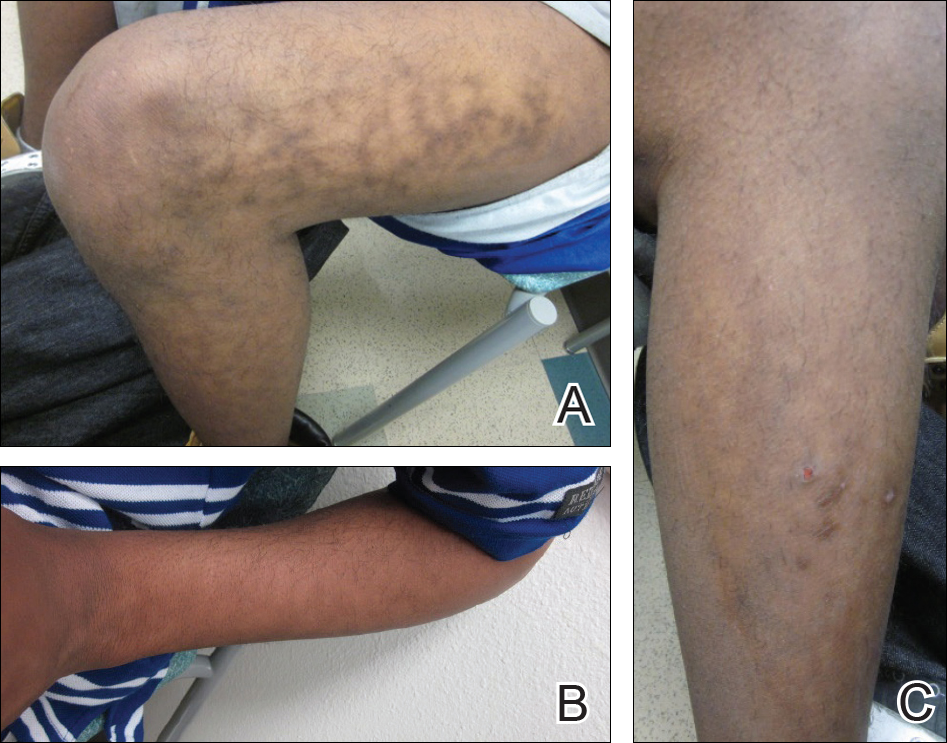

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should include terra firma-forme dermatosis in the differential diagnosis of any hyperpigmented condition, regardless of pattern of presentation.

- Clean the skin with an alcohol wipe to rule out a diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.