User login

Paraneoplastic Acrokeratosis Bazex Syndrome: Unusual Association With In Situ Follicular Lymphoma and Response to Acitretin

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

To the Editor:

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis (PA), also known as Bazex syndrome, is a rare paraneoplastic dermatosis first described in 1965 by Bazex et al.1 This entity is clinically characterized by dusky erythematous to violaceous keratoderma of the acral sites and commonly affects men older than 40 years. In most reported cases, there has been an underlying primary malignant neoplasm of the upper aerodigestive tract2; however, some other associated malignancies also have been reported. Skin changes tend to occur before the diagnosis of the associated tumor in 67% of cases. The cutaneous lesions usually resolve after successful treatment of the tumor and relapse in case of recurrence of the malignancy.3

A 53-year-old woman who was a smoker with no relevant medical background was referred to the dermatology department with an itching psoriasiform dermatitis on the palms and soles of 2 months' duration. There were no signs of systemic disease. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, dusky red, thick, scaly plaques on the soles with sparing of the insteps (Figure, A). Scattered symmetric hyperkeratotic plaques were present on the palms (Figure, B). We also detected onychodystrophy on the hands. Other dermatologic findings were normal. Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen of the left sole showed hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and a predominantly perivascular dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

With the diagnostic suspicion of PA, blood tests, chest radiograph, and colonoscopy were performed without revealing abnormalities. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also was performed, showing cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal, and inguinal adenopathies. Histologic examination of both inguinal adenectomy and cervical lymph node biopsy revealed Bcl-2-positive in situ follicular lymphoma (ISFL). Examination of an iliac crest marrow aspirate showed minimal involvement of lymphoma (10%). Follow-up imaging performed 4 months after diagnosis showed no changes. The patient was diagnosed with a low-grade chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with histologic findings consistent with ISFL presenting with small disperse adenopathies and minimal bone marrow involvement. The hematology department opted for a wait-and-see approach with 6-month follow-up imaging.

The skin lesions were first treated with salicylic acid cream 10%, psoralen plus UVA therapy, and methotrexate 20 mg weekly for 2 months without remission. Replacing the other therapies, we initiated acitretin 25 mg daily, achieving sustained remission after 6 months of treatment, and then continued with a scaled dose reduction. The patient remained lesion free 1 year after starting the treatment, with a daily dose of 10 mg of acitretin.

Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis has been traditionally described as a paraneoplastic entity mainly associated with primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the upper aerodigestive tract or a metastatic SCC of the cervical lymph nodes with an unknown origin.4,5 However, uncommon associations such as adenocarcinoma of the prostate, lung, esophagus, stomach, and colon; transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder; small cell carcinoma of the lung; cutaneous SCC; breast cancer; metastatic thymic carcinoma; metastatic neuroendocrine tumor; bronchial carcinoid tumor; SCC of the vulvar region; simultaneous multiple genitourinary tumors; and liposarcoma also have been described.6 Regarding the association with lymphoma, PA has been reported with peripheral T-cell lymphoma7 and Hodgkin disease8; however, ISFL underlying PA is rare.

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Western countries and comprises approximately 20% of all lymphomas.9 It is slightly more prevalent in females, and the majority of patients present with advanced-stage disease. Generally considered to be an incurable disease, a watchful-waiting approach of conservative management has been advocated in most cases, deferring treatment until symptoms appear.9

Histology of PA is nonspecific, as in our case. However, it facilitates a differential diagnosis of major dermatoses including psoriasis vulgaris, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and lupus erythematosus.

Paraneoplastic palmoplantar keratoderma also is characteristic of Howel-Evans syndrome, which is a rare inherited condition associated with esophageal cancer. In contrast to our case, palmoplantar keratoderma in these patients usually begins around 10 years of age, is caused by a mutation in the RHBDF2 gene, and is inherited in an autosomal pattern.10

The diagnosis in our case was supported by a typical clinical picture, nonspecific histology, and the concurrent finding of the underlying lymphoma. Treatment of PA must focus on the removal of the underlying malignancy, which implies the remission of the cutaneous lesions. Taking into account that a recurrence of the primary tumor leads to a relapse of skin manifestations while distant metastases do not cause a reappearance of PA, it could be suggested that pathogenetically relevant factors are produced by the primary tumor and by lymph node metastases but not by metastases elsewhere.

In this case, due to the wait-and-see approach, a specific treatment for the skin lesions was established. Although management of the skin itself generally is ineffective, there are isolated reports of response after corticosteroids, antibiotics, antimycotics, keratolytic measures, or psoralen plus UVA therapy.6 Wishart11 used etretinate to achieve an improvement of PA. We also achieved good response with acitretin. Retinoids are known to have antineoplastic activity, which may have been helpful in both the patient we presented and the one reported by Wishart.11 In summary, we propose adding ISFL to the expanding list of malignant neoplasms associated with PA, noting the response of skin lesions after acitretin.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

- Bazex A, Salvador R, Dupré A, et al. Syndrome paranéoplasique à type d'hyperkératose des extremités. Guérison après le traitement de l'épithelioma laryngé. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1965;72:182.

- Bazex A, Griffiths A. Acrokeratosis paraneoplasticae--a new cutaneous marker of malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1980;103:301-306.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex syndrome: acrokeratosis paraneoplastica. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:84-89.

- Witkowski JA, Parish LC. Bazex's syndrome. Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2883-2884.

- Bolognia JL. Bazex's syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:37-42.

- Sator PG, Breier F, Gschnait F. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex's syndrome): association with liposarcoma [published online August 28, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:1103-1105.

- Lin YC, Chu CY, Chiu HC. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica Bazex's syndrome: unusual association with a peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:440-441.

- Lucker GP, Steijlen PM. Acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (Bazex syndrome) occurring with acquired ichthyosis in Hodgkin's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:322-325.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al. Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:2976-2984.

- Sroa N, Witman P. Howel-Evans syndrome: a variant of ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 2010;85:183-185.

- Wishart JM. Bazex paraneoplastic acrokeratosis: a case report and response to Tigason. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:595-599.

Practice Points

- Paraneoplastic acrokeratosis may mimic palmo-plantar acrokeratosis in both clinical presentation and treatment.

- Uncommon associations of paraneoplastic acrokeratosis with different types of lymphoma have been described.

Two cases of asymmetric papules

CASE 1 ›

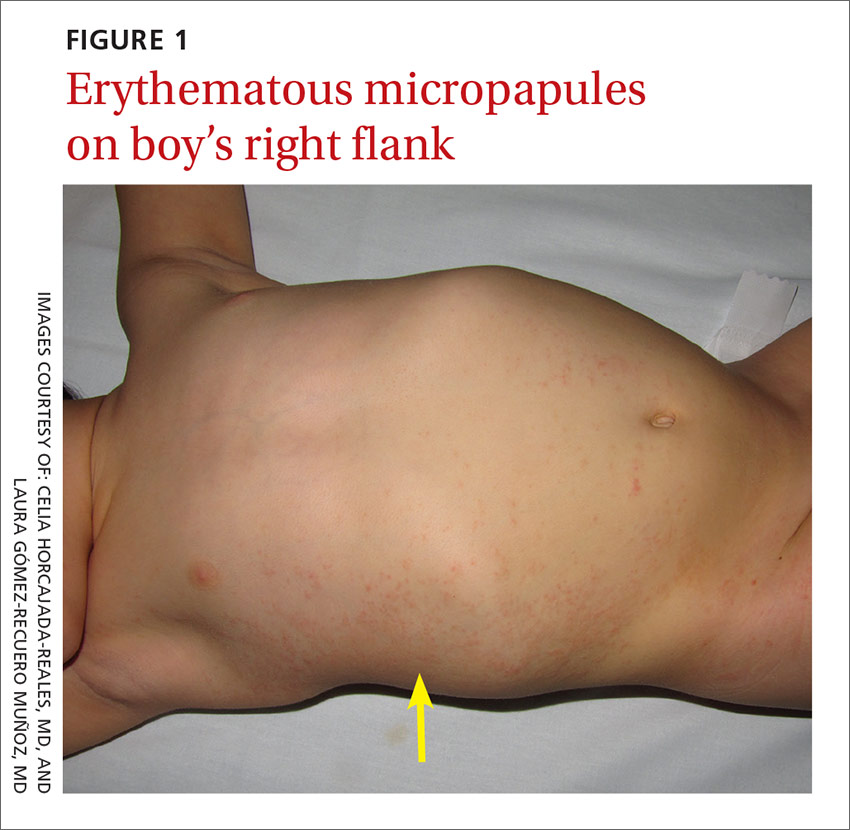

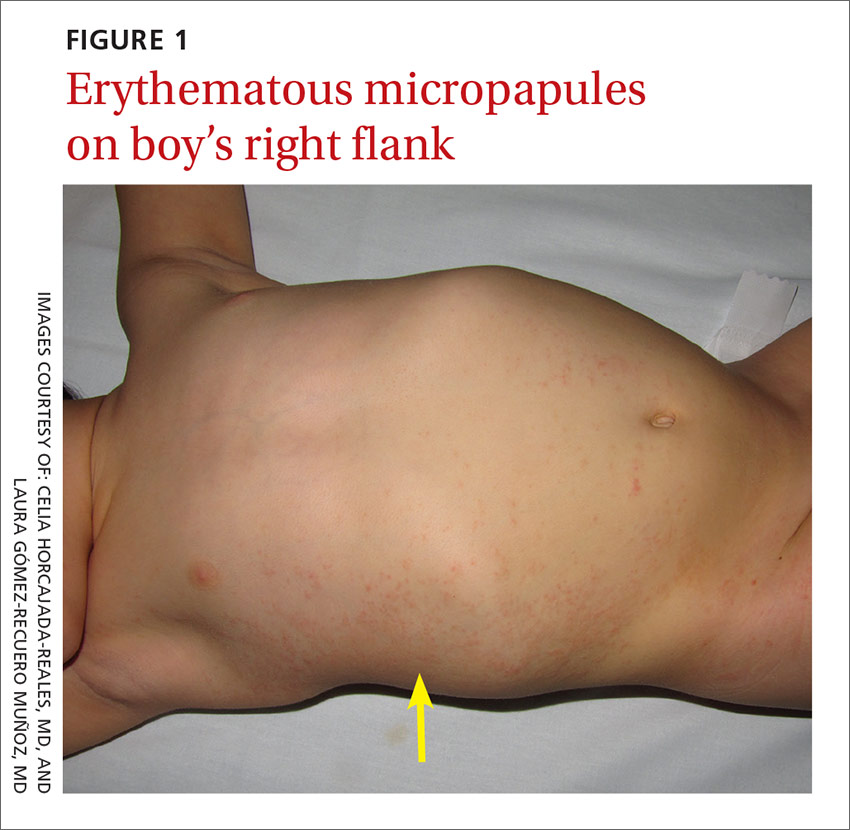

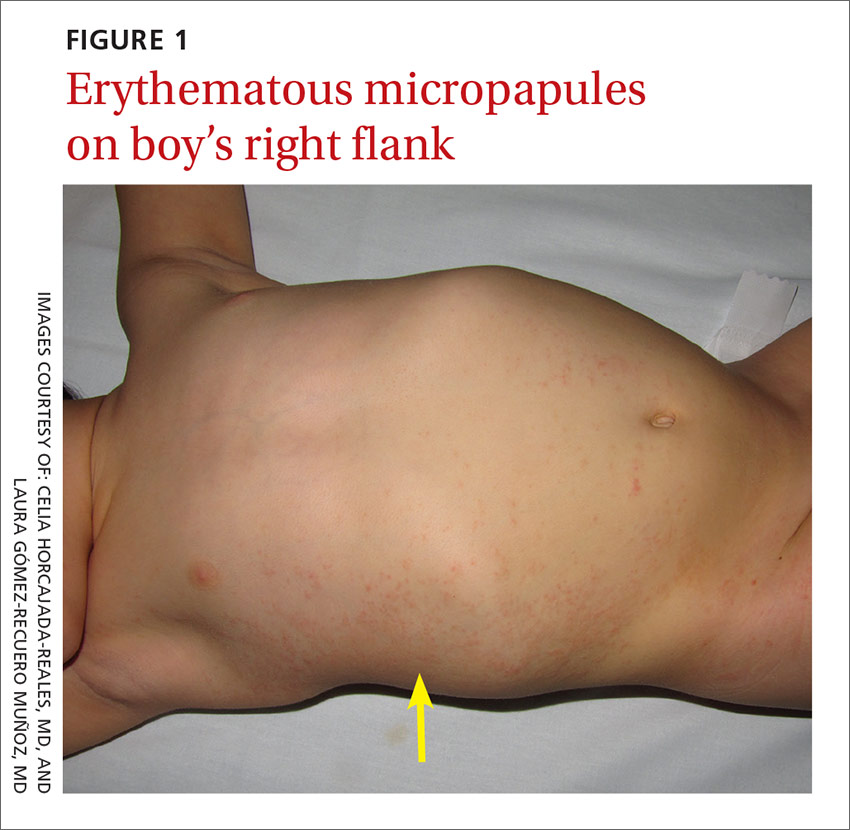

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.

CASE 1 ›

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

CASE 1 ›

A 3-year-old boy was brought to our emergency department for evaluation of skin lesions that he’d had for 7 days. The boy would sometimes scratch the lesions, which began on his right flank as erythematous micropapules and later spread to his right lateral thigh and inner arm (FIGURE 1). His lymph nodes were not palpable.

The boy’s parents had been told to use a topical corticosteroid, but the rash did not improve. His family denied fever or other previous infectious or systemic symptoms, and said that he hadn’t come into contact with any irritants or allergenic substances.

CASE 2 ›

A 13-year-old girl came to our emergency department with a pruriginous rash on her right leg and abdomen that she’d had for 4 days (FIGURE 2). The millimetric papules had also spread to the right side of her trunk, her right arm and armpit, and her inner thigh. Before the rash, she’d had a fever, otalgia, and conjunctivitis. We noted redness of her left conjunctiva, eardrum, and pharynx. The girl’s lymph nodes were not palpable. Serologic examinations for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, parvovirus B19, and Mycoplasma were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood

Both of these patients were given a diagnosis of asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), based on the appearance and distribution of the rashes.

A rare condition that mostly affects young children

APEC is a rash of unknown cause, although epidemiologic and clinical findings support a viral etiology. Cases of this rash were first reported in 1992 by Bodemer et al, and a year later, Taïeb et al reported new cases, establishing the term “asymmetric periflexural exanthem.”1,2 Several viruses have been related to APEC (including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, parainfluenza 2 and 3, and human herpesvirus 7), but none of these has been consistently associated with the rash.3-5

APEC tends to affect children between one and 5 years of age, but adult cases have been reported.6,7 The condition occurs slightly more frequently among females and more often in winter and spring.8,9 APEC is a rare condition; since 1992, there have only been about 300 cases reported in the literature.10

What you’ll see. The erythematous rash appears as an asymmetrical or unilateral papular, scarlatiniform, or eczematous exanthema. It initially affects the axilla or groin and may then progress to the extremities and trunk. Minor lesions infrequently present on the contralateral side. Most children who are affected by APEC are otherwise healthy and asymptomatic at presentation. The exanthem is occasionally pruritic and can be preceded by short respiratory or gastrointestinal prodromes or a low-grade fever.2,9 If the rash predominantly affects the lateral thoracic wall, it may be referred to as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem.11 Regional lymphadenopathies can often be found, and there is no systemic involvement.

The distribution of the rash helps to distinguish the condition

The differential diagnosis for this type of exanthem includes drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scarlet fever, papular acrodermatitis of childhood, and other viral rashes. The asymmetric distribution of APEC helps to distinguish the condition. Other possible asymmetric skin lesions, such as contact dermatitis, tinea corporis, or lichen striatus, can be differentiated by the characteristics of the cutaneous lesions. Contact dermatitis lesions are more vesicular, pruritic, and related to the contact area. Tinea corporis lesions tend to be smaller, circular, well-limited, and often have pustules. Lichen striatus starts as small pink-, red-, or flesh-colored spots that join together to form a dull red and slightly scaly linear band over the course of one or 2 weeks.12 Because APEC is self-limiting, a skin biopsy is usually not necessary.13

Lesions usually persist for one to 6 weeks and resolve with no sequelae. Only symptomatic treatment is required.9 Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, or oral antihistamines can be used, if necessary.

Our patients. Both patients were treated with oral antihistamines and the rashes completely resolved within 2 to 3 weeks.

CORRESPONDENCE

Celia Horcajada-Reales, MD, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Calle del Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain; [email protected].

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:693-696.

2. Taïeb A, Mégraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

3. Al Yousef Ali A, Farhi D, De Maricourt S, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema associated with HHV7 infection. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:230-231.

4. Coustou D, Masquelier B, Lafon ME, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: microbiologic case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:169-173.

5. Harangi F, Várszegi D, Szücs G. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood and viral examinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:112-115.

6. Zawar VP. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema: a report in an adult patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:401-404.

7. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

8. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. A clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

9. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

10. Mejía-Rodríguez SA, Ramírez-Romero VS, Valencia-Herrera A, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthema of childhood. An infrequently diagnosed disease entity. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2007;64:65-68.

11. Chuh AA, Chan HH. Unilateral mediothoracic exanthem: a variant of unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. Cutis. 2006;77:29-32.

12. Chuh A, Zawar V, Law M, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a brief review and arguments for diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4:e12.

13. Gelmetti C, Caputo R. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: who are you? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:293-294.