User login

Severe Phymatous Rosacea of the Nose, Cheeks, and Chin Treated With Hydrosurgery

Phymatous rosacea is a rare and severe form of rosacea that manifests as disfiguring soft-tissue hypertrophy and hyperplasia as well as fibrosis of the sebaceous glands. 1 Treatments for phymatous rosacea include pharmacotherapeutic and surgical modalities; most cases are treated surgically. Surgical modalities vary, ranging from cryosurgery to conventional excision, and consensus guidelines for surgical management do not exist because data are largely limited to case reports and small case series. 2 The Versajet II Hydrosurgery System (Smith-Nephew) is a high-pressure, pulsatile lavage system that has been used for phymatous rosacea and then only for rosacea of the nose (rhinophyma). We present the case of a patient with phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin who was successfully treated with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System beyond just the nose region.

Case Report

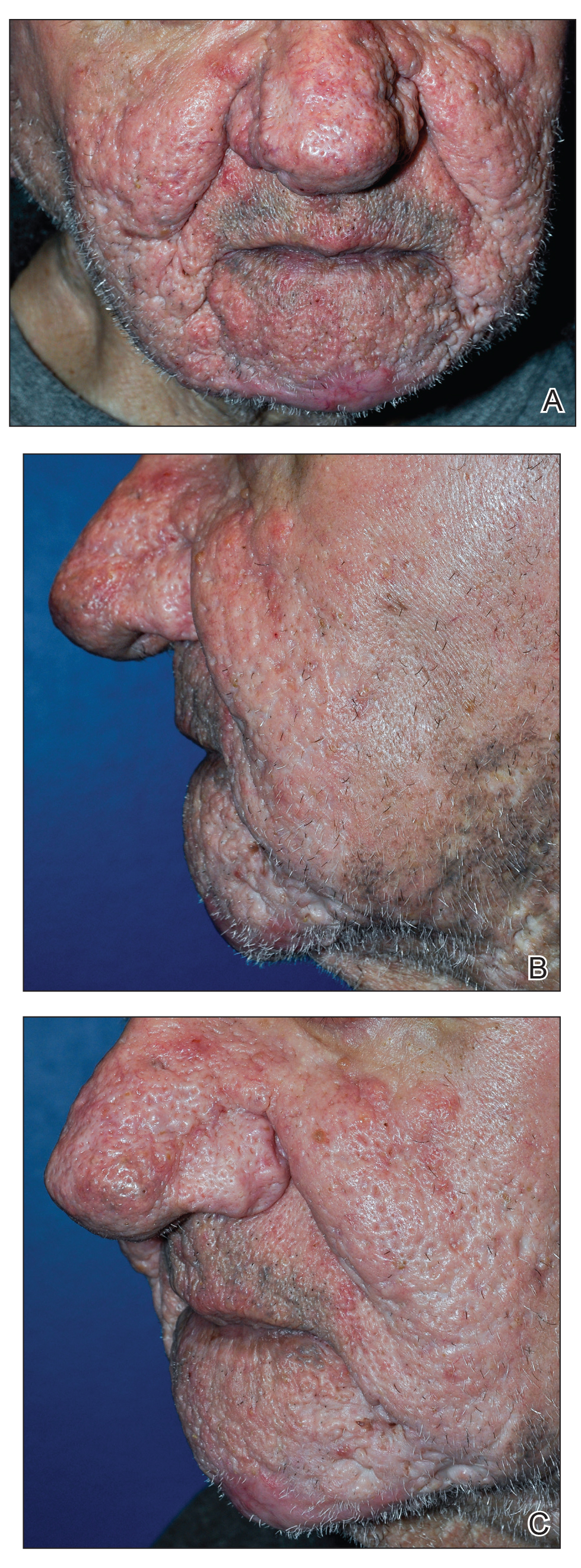

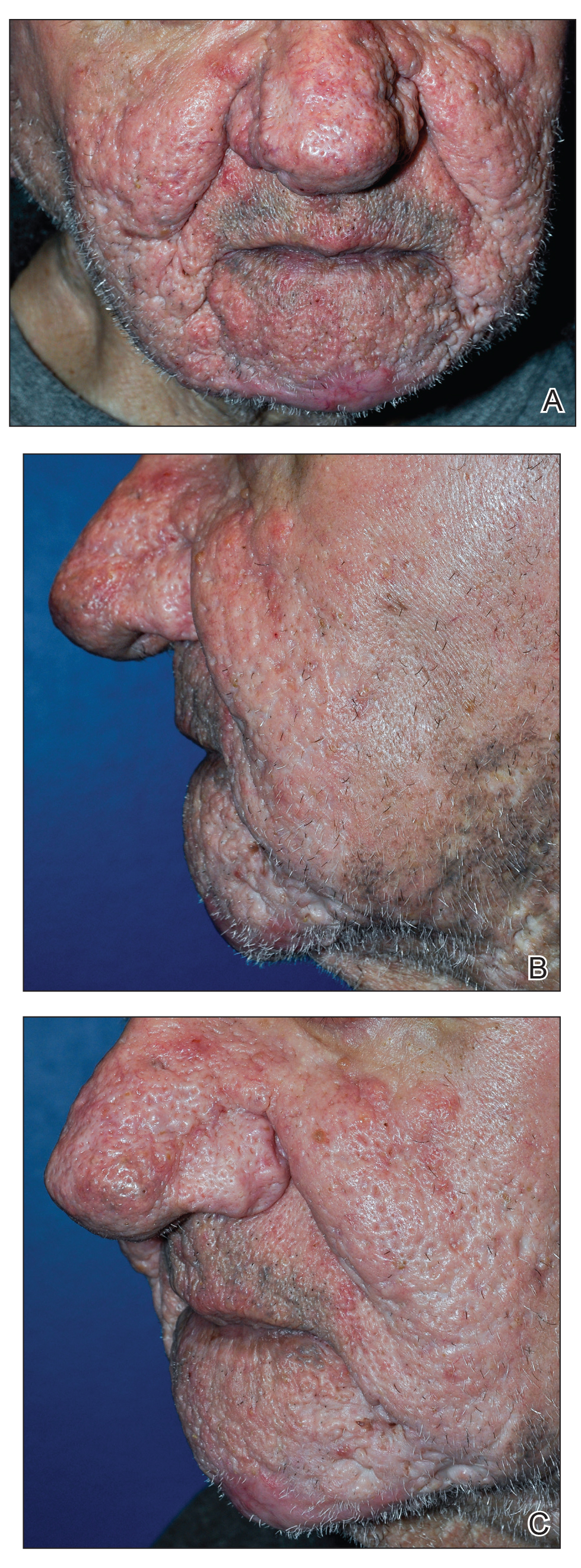

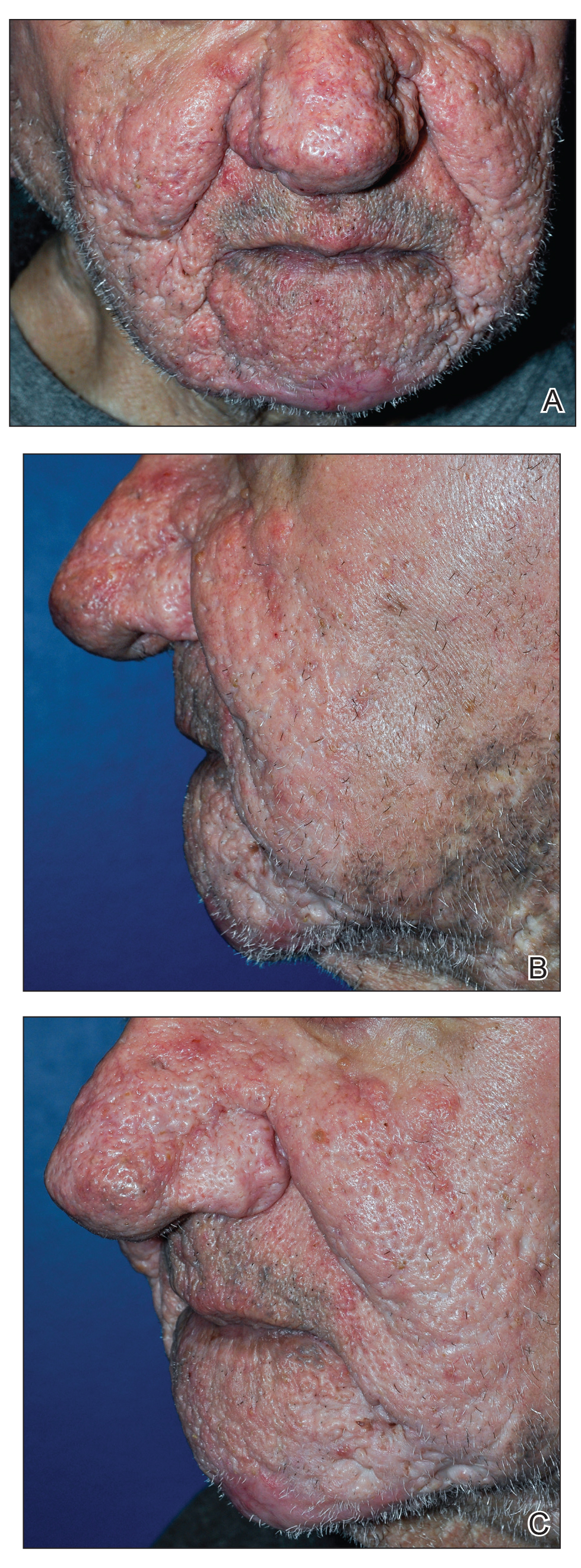

A 75-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of severe phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin that had been present for several years. Examination revealed verruciform, thickened, erythematous skin of the nose, cheeks, and chin; marked blue-gray hyperpigmentation on the neck and hands; generalized facial redness; and cystic and depressed scars (Figure 1). The patient had been treated with topical metronidazole without response, and isotretinoin worsened the symptoms. He also was taking minocycline but stopped it at our request because of concern that the drug was causing the blue-gray hyperpigmentation. The patient was referred to plastic surgery and tangential excision was recommended. Fractional ablative laser therapy was considered but deferred because the patient wanted quicker results.

The patient received tangential excision of the phymatous areas of the chin, bilateral cheeks, and nose with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System until a pleasing contour was noted. At 1-month follow-up, the patient had an excellent contour of the nose, cheeks, and chin (Figure 2).

Comment

Phymatous rosacea is a rare disfiguring disease that most commonly presents on the nose but also can affect the chin, cheeks, eyelids, ears, and forehead. Incidence is greater in individuals of Scottish descent and in men due to the influence of androgens. The etiology of the condition is unknown.1

Aside from clinical findings of hyperplastic and fibrotic sebaceous glands in conjunction with enlargement of the affected facial areas, histopathologic findings of phymatous rosacea vary but typically include hypertrophy of subcutaneous tissue, enlarged sebaceous ducts filled with keratin and sebum, atrophy of the dermis, and abnormal vascular development in the form of telangiectases.

Phymatous rosacea adversely affects patients’ physical, mental, and social well-being. Left untreated, it can cause nasal obstruction and recurrent bacterial infections. Furthermore, because of the potential extent of facial deformity, phymatous rosacea can be highly stigmatizing.3 Nonmelanoma skin cancers have been reported within phymatous skin, but evidence of an association between the 2 diseases remains inconclusive.4 Excised tissue from our patient was not submitted to pathology for analysis.

Given the far-reaching physical and psychological consequences of phymatous rosacea, treatment is critical but, regrettably, challenging. Although medical and surgical interventions exist, surgery is the most common practice. Oral isotretinoin may help, but many cases are recalcitrant, as was the disease in our patient. Therefore, procedural remedies often are sought, including scalpel excision, cryosurgery, argon laser, CO2 laser, dermabrasion, and electrocautery.2

Our patient underwent Versajet II Hydrosurgery System treatment of the phymatous rosacea on the nose, cheeks, and chin. Versajet is not yet commonly used to treat phymatous rosacea, likely due to the upfront cost of obtaining a new device, lack of physician familiarity, and few reports of its use for phymatous skin. A search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Web of Science using the terms Rosacea AND (Versajet OR Hydrosurgery) yielded only 6 cases of rosacea treated by hydrosurgery; all were limited to rhinophyma and reported excellent cosmetic and functional results.5-10 Our case was unique in that hydrosurgery was used to treat phymatous rosacea beyond the nose.

Hydrosurgery has many advantages in the treatment of phymatous rosacea and other conditions in which surgical debridement is necessary, such as burns and wounds. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that hydrosurgery is more cost-effective than conventional excision because of decreased operative time and intraoperative blood loss, fewer debridement procedures, and fewer postoperative complications.11

Rennekampff et al12 showed that Versajet debridement is superior to conventional surgery in contouring facial and acral sites and has a lower probability of infection. They proposed that by running a highly pressurized constant stream of saline across the device, Versajet clears blood and debris from the surgical site during excision.12 Hydrosurgical debridement also has been shown to reduce Staphylococcus aureus inoculate levels from in vitro–contaminated equine models significantly more than conventional debridement methods (P<.05).13

Versajet surgery appears to be well tolerated, with side effects comparable to those of classic surgical excision. A randomized controlled trial in burn patients in which treatment with Versajet was compared to traditional debridement found no significant difference in postoperative pain, healing time, and contracture rate.13

Overall, tangential excision of our patient’s phymatous rosacea using the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System yielded excellent contouring. However, due to the paucity of literature on the subject, it is difficult to discern the optimal treatment modality. Therefore, more research—ideally randomized trials—should be pursued to examine the comparative effectiveness of different interventions for phymatous rosacea.

- Curnier A, Choudhary S. Rhinophyma: dispelling the myths. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:351-354.

- Sadick H, Goepel B, Bersch C, et al. Rhinophyma: diagnosis and treatment options for a disfiguring tumor of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:114-120.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Lazzeri D, Colizzi L, Licata G, et al. Malignancies within rhinophyma: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36:396-405.

- Dunne JA, Saleh DB, Rawlins JM. Management of rhinophyma with Versajet™ and ReCell®. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:e282-e284.

- Yildiz K, Kayan BR, Dulgeroglu T, et al. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet™ Hydrosurgery System and autologous cell suspension (ReCELL®): a case report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:114-116.

- Nicolas J, Garmi R, Labbé D, et al. The role of Versajet in the surgical treatment of rhinophyma. case report. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54:78-81.

- Novati FC, Franchi A, Roggio T, et al. Treatment of a double-giant rhinophyma with electrocautery and Versajet Hydrosurgery System. Ann Ital Chir. 2015;86. pii: S2239253X15023269.

- Taghizadeh R, Mackay SP, Gilbert PM. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet Hydrosurgery System. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:330-333.

- Wong WL, Wong She R, Mathy JA. Rhinophyma treatment using Versajet Hydrosurgery. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E331-E332.

- Liu J, Ko JH, Secretov E, et al. Comparing the hydrosurgery system to conventional debridement techniques for the treatment of delayed healing wounds: a prospective, randomised clinical trial to investigate clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Int Wound J. 2015;12:456-461.

- Rennekampff H-O, Schaller H-E, Wisser D, et al. Debridement of burn wounds with a water jet surgical tool. Burns. 2006;32:64-69.

- Skarlina EM, Wilmink JM, Fall N, et al. Effectiveness of conventional and hydrosurgical debridement methods in reducing Staphylococcus aureus inoculation of equine muscle in vitro. Equine Vet J. 2015;47:218-222.

Phymatous rosacea is a rare and severe form of rosacea that manifests as disfiguring soft-tissue hypertrophy and hyperplasia as well as fibrosis of the sebaceous glands. 1 Treatments for phymatous rosacea include pharmacotherapeutic and surgical modalities; most cases are treated surgically. Surgical modalities vary, ranging from cryosurgery to conventional excision, and consensus guidelines for surgical management do not exist because data are largely limited to case reports and small case series. 2 The Versajet II Hydrosurgery System (Smith-Nephew) is a high-pressure, pulsatile lavage system that has been used for phymatous rosacea and then only for rosacea of the nose (rhinophyma). We present the case of a patient with phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin who was successfully treated with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System beyond just the nose region.

Case Report

A 75-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of severe phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin that had been present for several years. Examination revealed verruciform, thickened, erythematous skin of the nose, cheeks, and chin; marked blue-gray hyperpigmentation on the neck and hands; generalized facial redness; and cystic and depressed scars (Figure 1). The patient had been treated with topical metronidazole without response, and isotretinoin worsened the symptoms. He also was taking minocycline but stopped it at our request because of concern that the drug was causing the blue-gray hyperpigmentation. The patient was referred to plastic surgery and tangential excision was recommended. Fractional ablative laser therapy was considered but deferred because the patient wanted quicker results.

The patient received tangential excision of the phymatous areas of the chin, bilateral cheeks, and nose with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System until a pleasing contour was noted. At 1-month follow-up, the patient had an excellent contour of the nose, cheeks, and chin (Figure 2).

Comment

Phymatous rosacea is a rare disfiguring disease that most commonly presents on the nose but also can affect the chin, cheeks, eyelids, ears, and forehead. Incidence is greater in individuals of Scottish descent and in men due to the influence of androgens. The etiology of the condition is unknown.1

Aside from clinical findings of hyperplastic and fibrotic sebaceous glands in conjunction with enlargement of the affected facial areas, histopathologic findings of phymatous rosacea vary but typically include hypertrophy of subcutaneous tissue, enlarged sebaceous ducts filled with keratin and sebum, atrophy of the dermis, and abnormal vascular development in the form of telangiectases.

Phymatous rosacea adversely affects patients’ physical, mental, and social well-being. Left untreated, it can cause nasal obstruction and recurrent bacterial infections. Furthermore, because of the potential extent of facial deformity, phymatous rosacea can be highly stigmatizing.3 Nonmelanoma skin cancers have been reported within phymatous skin, but evidence of an association between the 2 diseases remains inconclusive.4 Excised tissue from our patient was not submitted to pathology for analysis.

Given the far-reaching physical and psychological consequences of phymatous rosacea, treatment is critical but, regrettably, challenging. Although medical and surgical interventions exist, surgery is the most common practice. Oral isotretinoin may help, but many cases are recalcitrant, as was the disease in our patient. Therefore, procedural remedies often are sought, including scalpel excision, cryosurgery, argon laser, CO2 laser, dermabrasion, and electrocautery.2

Our patient underwent Versajet II Hydrosurgery System treatment of the phymatous rosacea on the nose, cheeks, and chin. Versajet is not yet commonly used to treat phymatous rosacea, likely due to the upfront cost of obtaining a new device, lack of physician familiarity, and few reports of its use for phymatous skin. A search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Web of Science using the terms Rosacea AND (Versajet OR Hydrosurgery) yielded only 6 cases of rosacea treated by hydrosurgery; all were limited to rhinophyma and reported excellent cosmetic and functional results.5-10 Our case was unique in that hydrosurgery was used to treat phymatous rosacea beyond the nose.

Hydrosurgery has many advantages in the treatment of phymatous rosacea and other conditions in which surgical debridement is necessary, such as burns and wounds. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that hydrosurgery is more cost-effective than conventional excision because of decreased operative time and intraoperative blood loss, fewer debridement procedures, and fewer postoperative complications.11

Rennekampff et al12 showed that Versajet debridement is superior to conventional surgery in contouring facial and acral sites and has a lower probability of infection. They proposed that by running a highly pressurized constant stream of saline across the device, Versajet clears blood and debris from the surgical site during excision.12 Hydrosurgical debridement also has been shown to reduce Staphylococcus aureus inoculate levels from in vitro–contaminated equine models significantly more than conventional debridement methods (P<.05).13

Versajet surgery appears to be well tolerated, with side effects comparable to those of classic surgical excision. A randomized controlled trial in burn patients in which treatment with Versajet was compared to traditional debridement found no significant difference in postoperative pain, healing time, and contracture rate.13

Overall, tangential excision of our patient’s phymatous rosacea using the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System yielded excellent contouring. However, due to the paucity of literature on the subject, it is difficult to discern the optimal treatment modality. Therefore, more research—ideally randomized trials—should be pursued to examine the comparative effectiveness of different interventions for phymatous rosacea.

Phymatous rosacea is a rare and severe form of rosacea that manifests as disfiguring soft-tissue hypertrophy and hyperplasia as well as fibrosis of the sebaceous glands. 1 Treatments for phymatous rosacea include pharmacotherapeutic and surgical modalities; most cases are treated surgically. Surgical modalities vary, ranging from cryosurgery to conventional excision, and consensus guidelines for surgical management do not exist because data are largely limited to case reports and small case series. 2 The Versajet II Hydrosurgery System (Smith-Nephew) is a high-pressure, pulsatile lavage system that has been used for phymatous rosacea and then only for rosacea of the nose (rhinophyma). We present the case of a patient with phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin who was successfully treated with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System beyond just the nose region.

Case Report

A 75-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of severe phymatous rosacea of the nose, cheeks, and chin that had been present for several years. Examination revealed verruciform, thickened, erythematous skin of the nose, cheeks, and chin; marked blue-gray hyperpigmentation on the neck and hands; generalized facial redness; and cystic and depressed scars (Figure 1). The patient had been treated with topical metronidazole without response, and isotretinoin worsened the symptoms. He also was taking minocycline but stopped it at our request because of concern that the drug was causing the blue-gray hyperpigmentation. The patient was referred to plastic surgery and tangential excision was recommended. Fractional ablative laser therapy was considered but deferred because the patient wanted quicker results.

The patient received tangential excision of the phymatous areas of the chin, bilateral cheeks, and nose with the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System until a pleasing contour was noted. At 1-month follow-up, the patient had an excellent contour of the nose, cheeks, and chin (Figure 2).

Comment

Phymatous rosacea is a rare disfiguring disease that most commonly presents on the nose but also can affect the chin, cheeks, eyelids, ears, and forehead. Incidence is greater in individuals of Scottish descent and in men due to the influence of androgens. The etiology of the condition is unknown.1

Aside from clinical findings of hyperplastic and fibrotic sebaceous glands in conjunction with enlargement of the affected facial areas, histopathologic findings of phymatous rosacea vary but typically include hypertrophy of subcutaneous tissue, enlarged sebaceous ducts filled with keratin and sebum, atrophy of the dermis, and abnormal vascular development in the form of telangiectases.

Phymatous rosacea adversely affects patients’ physical, mental, and social well-being. Left untreated, it can cause nasal obstruction and recurrent bacterial infections. Furthermore, because of the potential extent of facial deformity, phymatous rosacea can be highly stigmatizing.3 Nonmelanoma skin cancers have been reported within phymatous skin, but evidence of an association between the 2 diseases remains inconclusive.4 Excised tissue from our patient was not submitted to pathology for analysis.

Given the far-reaching physical and psychological consequences of phymatous rosacea, treatment is critical but, regrettably, challenging. Although medical and surgical interventions exist, surgery is the most common practice. Oral isotretinoin may help, but many cases are recalcitrant, as was the disease in our patient. Therefore, procedural remedies often are sought, including scalpel excision, cryosurgery, argon laser, CO2 laser, dermabrasion, and electrocautery.2

Our patient underwent Versajet II Hydrosurgery System treatment of the phymatous rosacea on the nose, cheeks, and chin. Versajet is not yet commonly used to treat phymatous rosacea, likely due to the upfront cost of obtaining a new device, lack of physician familiarity, and few reports of its use for phymatous skin. A search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Web of Science using the terms Rosacea AND (Versajet OR Hydrosurgery) yielded only 6 cases of rosacea treated by hydrosurgery; all were limited to rhinophyma and reported excellent cosmetic and functional results.5-10 Our case was unique in that hydrosurgery was used to treat phymatous rosacea beyond the nose.

Hydrosurgery has many advantages in the treatment of phymatous rosacea and other conditions in which surgical debridement is necessary, such as burns and wounds. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that hydrosurgery is more cost-effective than conventional excision because of decreased operative time and intraoperative blood loss, fewer debridement procedures, and fewer postoperative complications.11

Rennekampff et al12 showed that Versajet debridement is superior to conventional surgery in contouring facial and acral sites and has a lower probability of infection. They proposed that by running a highly pressurized constant stream of saline across the device, Versajet clears blood and debris from the surgical site during excision.12 Hydrosurgical debridement also has been shown to reduce Staphylococcus aureus inoculate levels from in vitro–contaminated equine models significantly more than conventional debridement methods (P<.05).13

Versajet surgery appears to be well tolerated, with side effects comparable to those of classic surgical excision. A randomized controlled trial in burn patients in which treatment with Versajet was compared to traditional debridement found no significant difference in postoperative pain, healing time, and contracture rate.13

Overall, tangential excision of our patient’s phymatous rosacea using the Versajet II Hydrosurgery System yielded excellent contouring. However, due to the paucity of literature on the subject, it is difficult to discern the optimal treatment modality. Therefore, more research—ideally randomized trials—should be pursued to examine the comparative effectiveness of different interventions for phymatous rosacea.

- Curnier A, Choudhary S. Rhinophyma: dispelling the myths. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:351-354.

- Sadick H, Goepel B, Bersch C, et al. Rhinophyma: diagnosis and treatment options for a disfiguring tumor of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:114-120.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Lazzeri D, Colizzi L, Licata G, et al. Malignancies within rhinophyma: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36:396-405.

- Dunne JA, Saleh DB, Rawlins JM. Management of rhinophyma with Versajet™ and ReCell®. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:e282-e284.

- Yildiz K, Kayan BR, Dulgeroglu T, et al. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet™ Hydrosurgery System and autologous cell suspension (ReCELL®): a case report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:114-116.

- Nicolas J, Garmi R, Labbé D, et al. The role of Versajet in the surgical treatment of rhinophyma. case report. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54:78-81.

- Novati FC, Franchi A, Roggio T, et al. Treatment of a double-giant rhinophyma with electrocautery and Versajet Hydrosurgery System. Ann Ital Chir. 2015;86. pii: S2239253X15023269.

- Taghizadeh R, Mackay SP, Gilbert PM. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet Hydrosurgery System. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:330-333.

- Wong WL, Wong She R, Mathy JA. Rhinophyma treatment using Versajet Hydrosurgery. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E331-E332.

- Liu J, Ko JH, Secretov E, et al. Comparing the hydrosurgery system to conventional debridement techniques for the treatment of delayed healing wounds: a prospective, randomised clinical trial to investigate clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Int Wound J. 2015;12:456-461.

- Rennekampff H-O, Schaller H-E, Wisser D, et al. Debridement of burn wounds with a water jet surgical tool. Burns. 2006;32:64-69.

- Skarlina EM, Wilmink JM, Fall N, et al. Effectiveness of conventional and hydrosurgical debridement methods in reducing Staphylococcus aureus inoculation of equine muscle in vitro. Equine Vet J. 2015;47:218-222.

- Curnier A, Choudhary S. Rhinophyma: dispelling the myths. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:351-354.

- Sadick H, Goepel B, Bersch C, et al. Rhinophyma: diagnosis and treatment options for a disfiguring tumor of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61:114-120.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Lazzeri D, Colizzi L, Licata G, et al. Malignancies within rhinophyma: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36:396-405.

- Dunne JA, Saleh DB, Rawlins JM. Management of rhinophyma with Versajet™ and ReCell®. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:e282-e284.

- Yildiz K, Kayan BR, Dulgeroglu T, et al. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet™ Hydrosurgery System and autologous cell suspension (ReCELL®): a case report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:114-116.

- Nicolas J, Garmi R, Labbé D, et al. The role of Versajet in the surgical treatment of rhinophyma. case report. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54:78-81.

- Novati FC, Franchi A, Roggio T, et al. Treatment of a double-giant rhinophyma with electrocautery and Versajet Hydrosurgery System. Ann Ital Chir. 2015;86. pii: S2239253X15023269.

- Taghizadeh R, Mackay SP, Gilbert PM. Treatment of rhinophyma with the Versajet Hydrosurgery System. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:330-333.

- Wong WL, Wong She R, Mathy JA. Rhinophyma treatment using Versajet Hydrosurgery. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E331-E332.

- Liu J, Ko JH, Secretov E, et al. Comparing the hydrosurgery system to conventional debridement techniques for the treatment of delayed healing wounds: a prospective, randomised clinical trial to investigate clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Int Wound J. 2015;12:456-461.

- Rennekampff H-O, Schaller H-E, Wisser D, et al. Debridement of burn wounds with a water jet surgical tool. Burns. 2006;32:64-69.

- Skarlina EM, Wilmink JM, Fall N, et al. Effectiveness of conventional and hydrosurgical debridement methods in reducing Staphylococcus aureus inoculation of equine muscle in vitro. Equine Vet J. 2015;47:218-222.

Practice Points

- Phymatous rosacea is a rare disfiguring disease that most commonly affects men and can have considerable effects on a patient’s physical, mental, and social well-being.

- Treatment of phymatous rosacea usually is surgical; however, no consensus guidelines exist for best surgical management.

- The Versajet II Hydrosurgery System can be useful and effective for the treatment of phymatous rosacea, not only on the nose but elsewhere on the face.

Comparison of Salicylic Acid 30% Peel and Pneumatic Broadband Light in the Treatment of Mild to Moderately Severe Facial Acne Vulgaris

Facial acne vulgaris is a common skin disease among teenagers and adolescents that may negatively affect self-esteem, perceived facial attractiveness, and social participation.1 Treatments for acne often are multimodal and require the utmost adherence. For these reasons, acne treatments have been challenging to clinicians and patients alike, as patient compliance in maintaining the use of prescribed topical and oral medications remains essential to attain improvement in quality of life (QOL).

Salicylic acid is a popular medicament for acne treatment that frequently is used as monotherapy or as an adjuvant for other acne treatments, especially in patients with oily skin.2 Salicylic acid has a keratolytic effect, causing corneocyte discohesion in clogged pores or congested follicles,2 and it is effective in treating both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne.3,4

Light therapy, particularly with visible light, has been demonstrated to improve acne outcomes.5 Pneumatic broadband light (PBBL) is a therapeutic light treatment in the broadband range (400–1200 nm) that is combined with vacuum suction, which creates a mechanical lysis of thin-walled pustules and dislodges pore impaction. Additionally, the blue light portion of the PBBL spectrum targets endogenous porphyrins in Propionibacterium acnes, resulting in bacterial destruction.6-8

The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of salicylic acid 30% peel versus PBBL in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris.

METHODS

Study Design

This single-blind, randomized, split-face pilot study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). All patients provided informed consent before entering the study. The single-blind evaluation was performed by one dermatologist (C.T.) who examined the participants on every visit prior to PBBL treatment.

Before the study started, participants were randomized for which side of the face was to be treated with PBBL using a number assigned to each participant. Participants received both treatments—salicylic acid 30% peel on one side of the face and PBBL treatment on the other side of the face—once weekly for a total of 6 treatments. They were then asked to return for 2 follow-up evaluations at weeks 3 and 6 following the last treatment session and were instructed not to use any topical or oral acne medications during these follow-up periods.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients aged 18 years and older of any race and sex with noninflammatory papules, some inflammatory papules, and no more than 1 nodule (considered as mild to moderately severe facial acne) were included in the study. Participants had not been on any topical acne medications for at least 1 month and/or oral retinoids for at least 1 year prior to the study period. All women completed urine pregnancy tests prior to the study and were advised to utilize birth control during the study period.

Study Treatments

Salicylic Acid 30% Peel

The participant’s face was cleansed thoroughly before application of salicylic acid 30% (1.5 g/2.5 mL) to half of the face and left on for 5 minutes before being carefully rinsed off by spraying with spring water. Prior to initiating PBBL therapy, the peeled side of the participant’s face was covered with a towel.

Pneumatic Broadband Light

On the other side of the face, PBBL was performed to deliver broadband light within the spectrum range of 400 to 1200 nm at a setting approximately equivalent to a fluence of 4 to 6 J/cm2 and a vacuum setting approximately equivalent to a negative pressure of 3 lb/in2. The power setting was increased on each subsequent visit depending on each participant’s tolerability.

Participants were required to apply a moisturizer and sunscreen to the face and avoid excessive sun exposure between study visits.

Efficacy Evaluation

A comparison of the efficacy of the treatments was determined by clinical evaluation and examining the results of the outcome measurements with the modified Global Acne Grading Score (mGAGS) and Acne QOL Scale during each treatment visit. Facial photographs were taken at each visit.

Modified Global Acne Grading Score

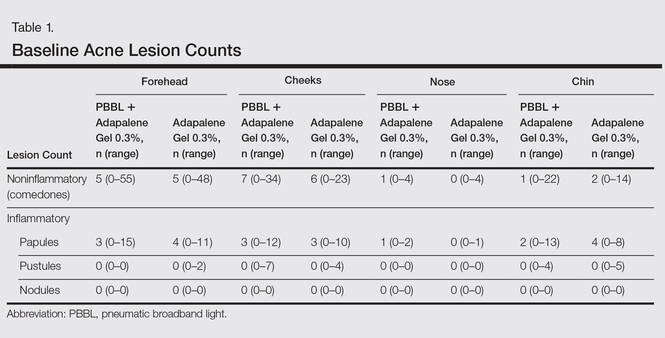

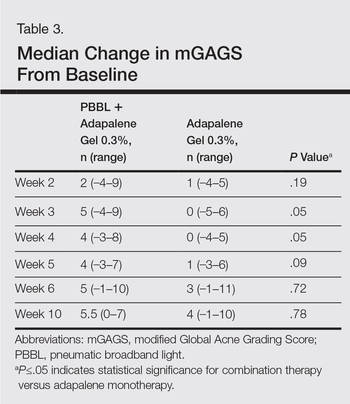

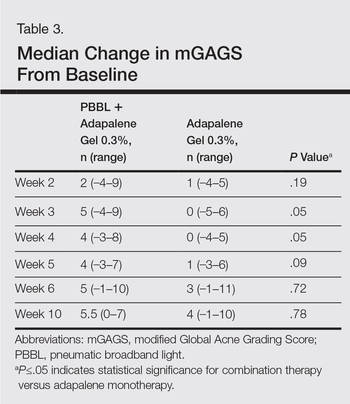

The mGAGS is a modification of the Global Acne Grading Scale (GAGS) that has been used to evaluate acne severity in many studies.9-11 The GAGS considers 6 locations on the face with a grading factor for each location. The local score is obtained by multiplying the factor rated by location with the factor of clinical assessment: local score = factor rated by location × factor rated by clinical assessment. The total score is the sum of the individual local scores (Table 1).

Although the original GAGS incorporated the type and location of the lesions in its calculation, we felt that the number of lesions also was important to add to our grading score. Therefore, we modified the GAGS by adding a factor rated by the number of lesions to improve the accuracy of the test. Accordingly, the local mGAGS scores were calculated by multiplying the location factor by the lesion type and number of lesions factors: local score = location factor × lesion type factor × number of lesions factor.

Acne QOL Questionnaire

Acne QOL was assessed during each visit to demonstrate if the treatment results affected participants’ socialization due to appearance.12 Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire, which consisted of 9 questions with 4 rating answers (0=not affected; 1=mildly affected; 2=moderately affected; 3=markedly affected). A total score of 9 or higher (high score) indicated that acne had a substantial negative impact on the participant, while a total score below 9 (low score) meant acne scarcely impacted social aspects and daily activities of the patient.

Safety Evaluation

The safety of the treatments was evaluated by clinical inspection and by comparing the results of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBPRS)13 after treatment. The WBPRS is used worldwide among researchers to assess pain, particularly in children.14,15 It is composed of 6 faces expressing pain with word descriptions with a corresponding number range reflecting pain severity from 0 to 5 (0=no hurt; 1=hurts little bit; 2=hurts little more; 3=hurts even more; 4=hurts whole lot; 5=hurts worst).13

Statistical Analysis

All variables were presented as the median (range). A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare clinical responses between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies. SPSS software version 12.0 was used for all statistical analysis. A 2-tailed P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Twelve participants (2 males, 10 females) aged 17 to 36 years (median age, 22 years; mean age [SD], 23.33 [1.65] years) with both comedonal and inflammatory acne were enrolled into this study for 6 split-face treatments of salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL at 1-week intervals for 6 weeks, with 2 subsequent follow-up sessions at weeks 3 and 6 posttreatment. Of the 12 participants, 11 were white and 1 was Asian American, with Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV. Nine participants (75%) completed the study. One participant dropped out of the study after the fourth treatment due to a scheduling conflict, and the other 2 participants did not return for follow-up. No participants withdrew from the study because of adverse therapeutic events.

Efficacy Evaluation

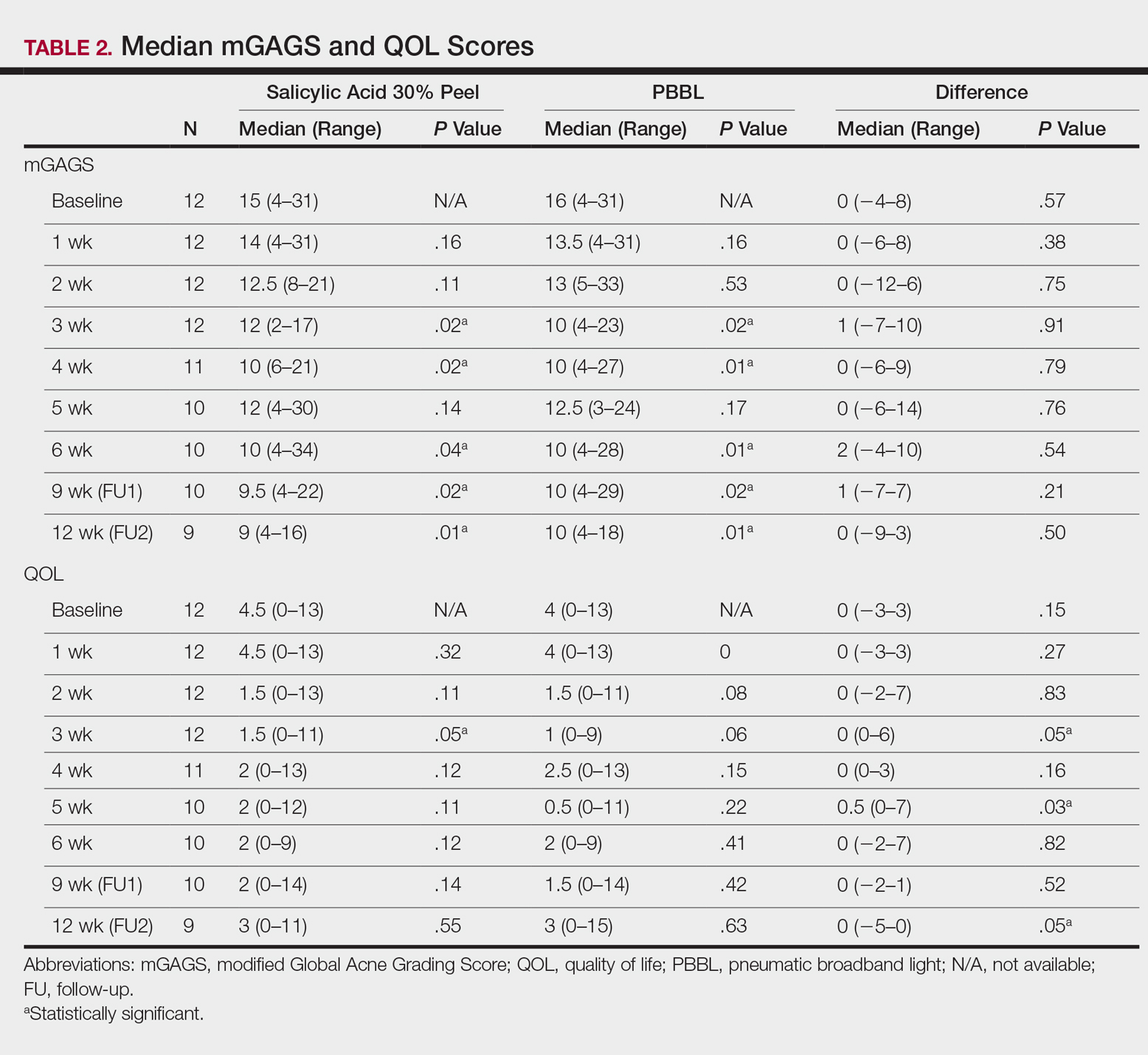

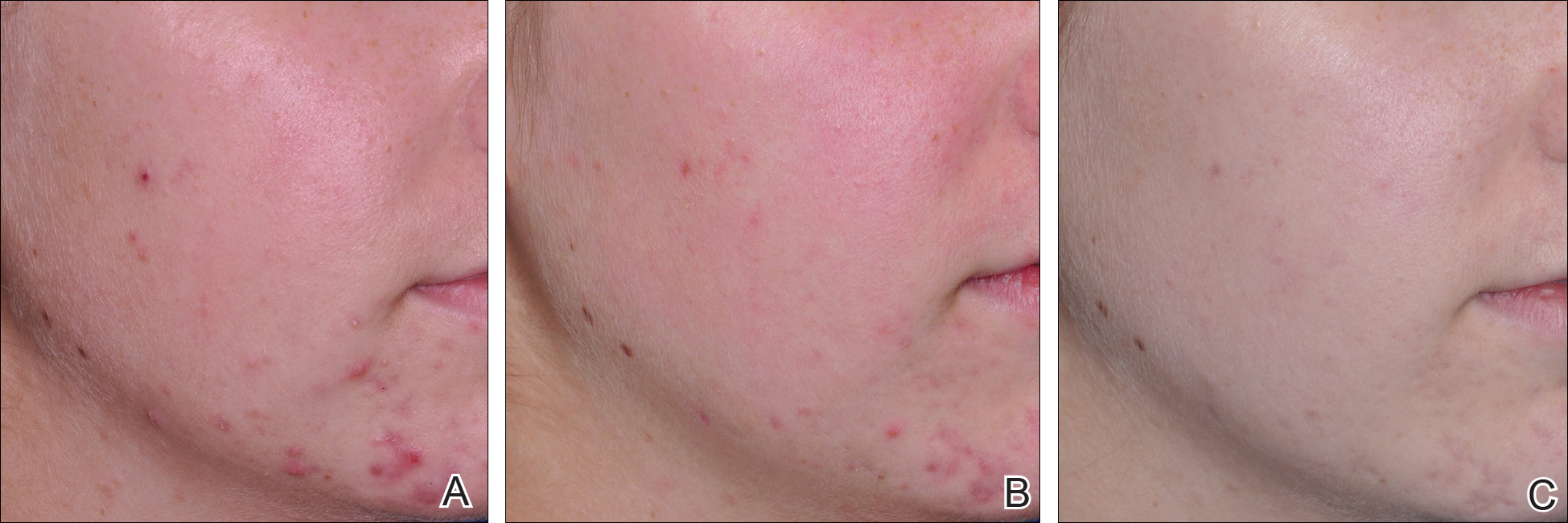

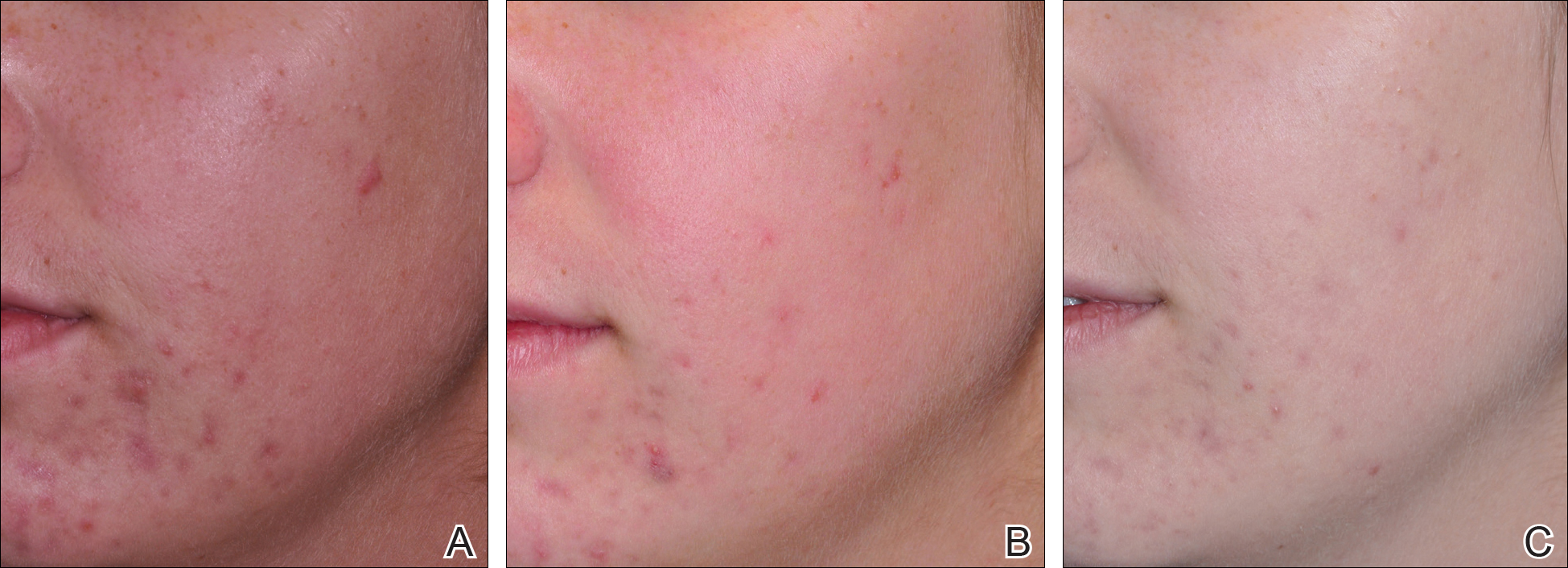

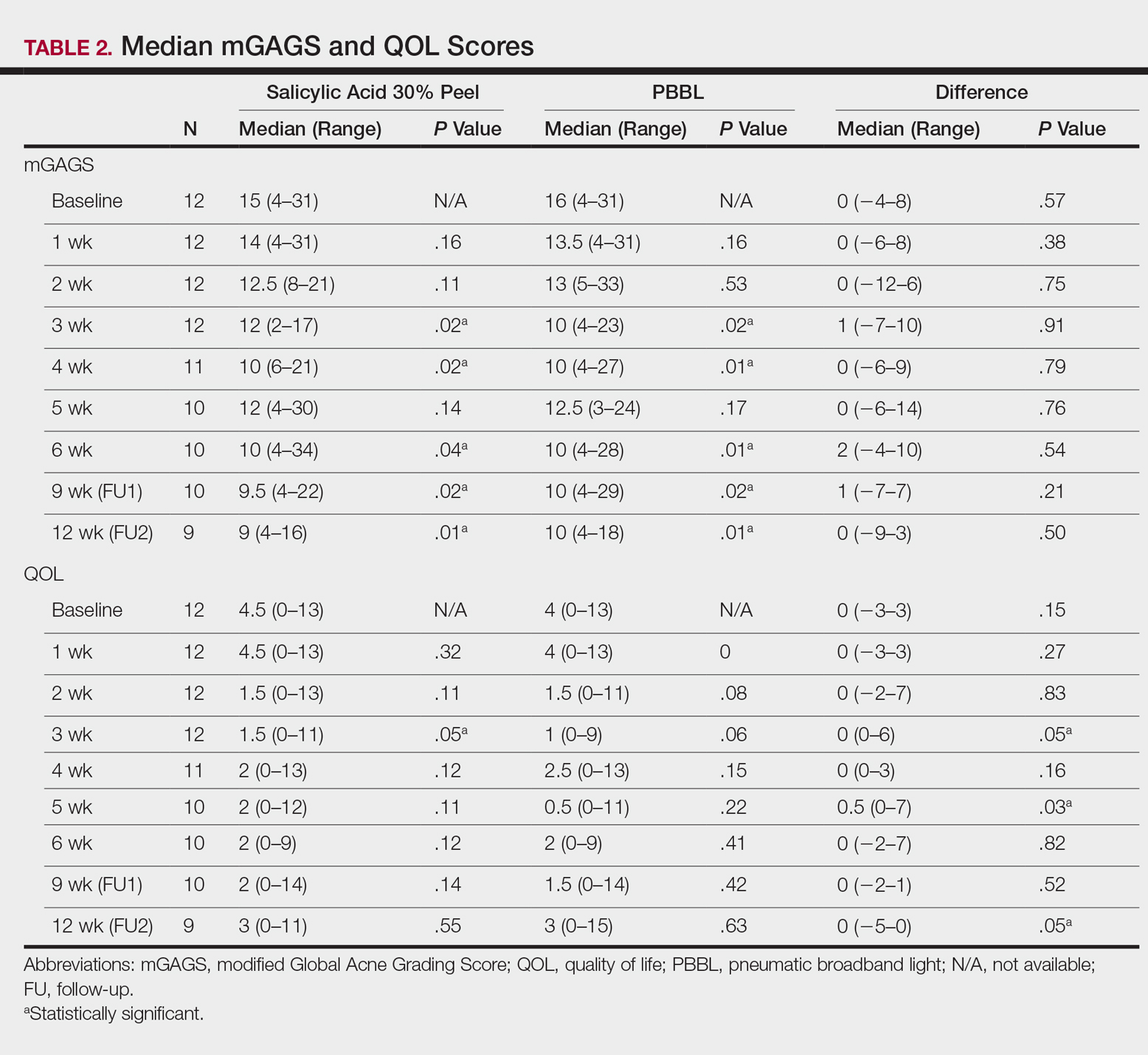

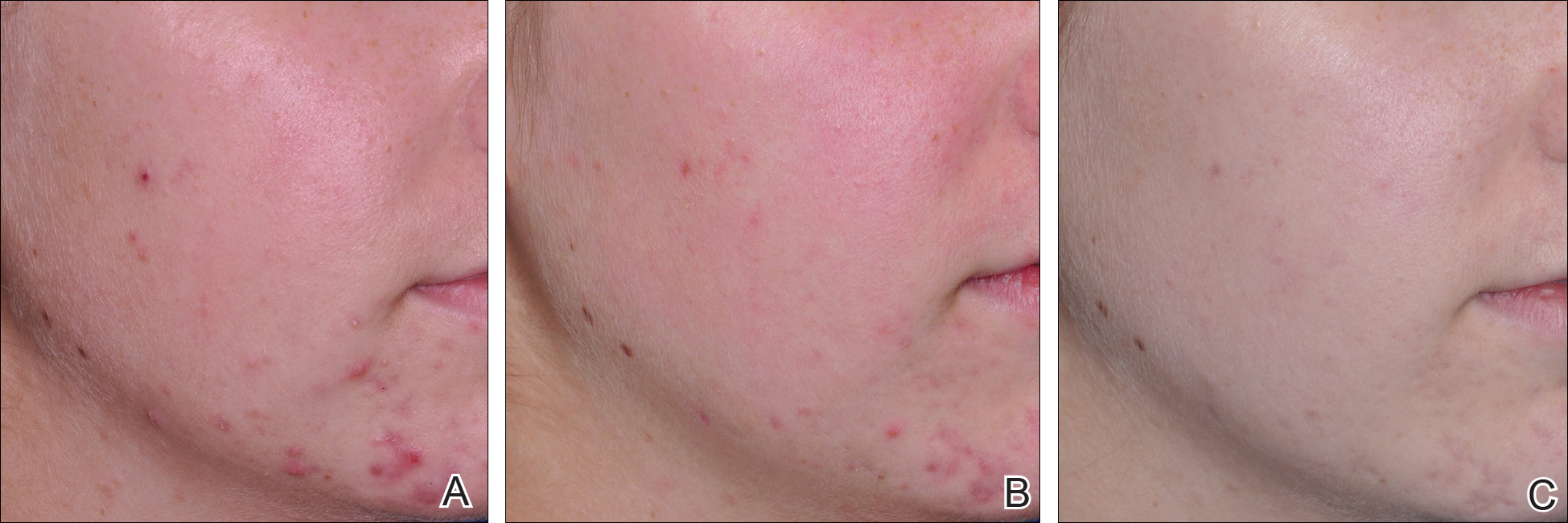

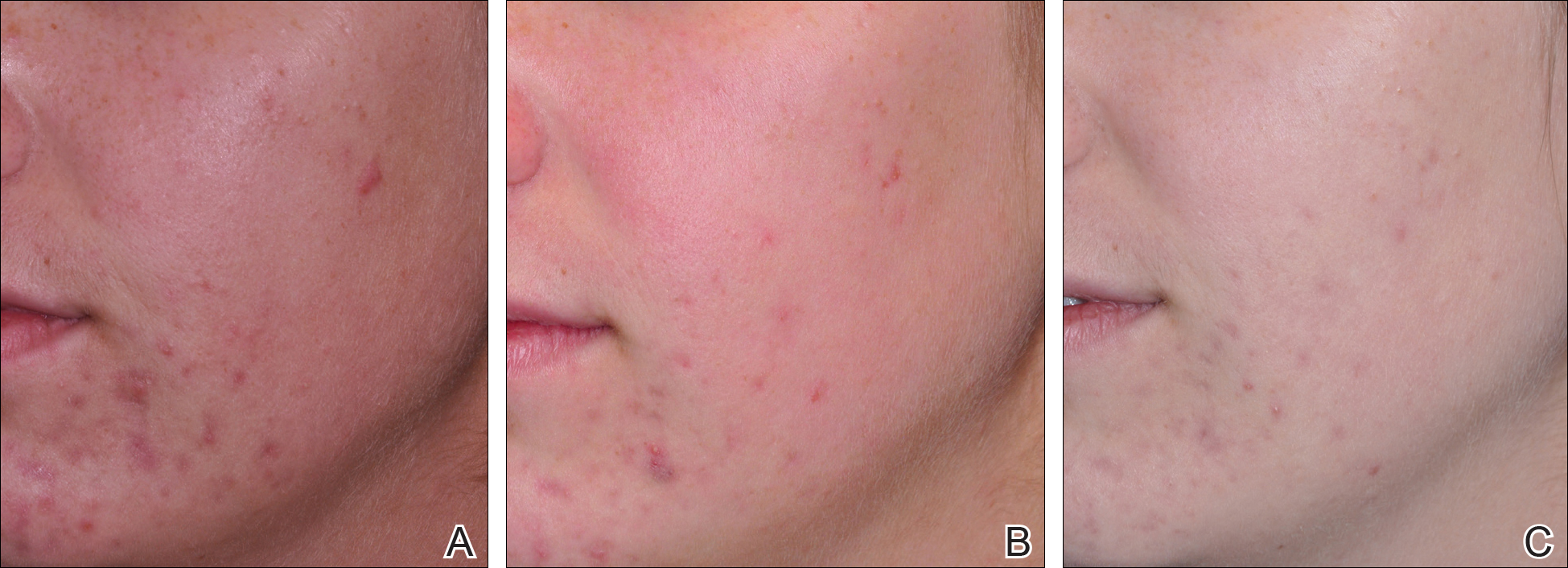

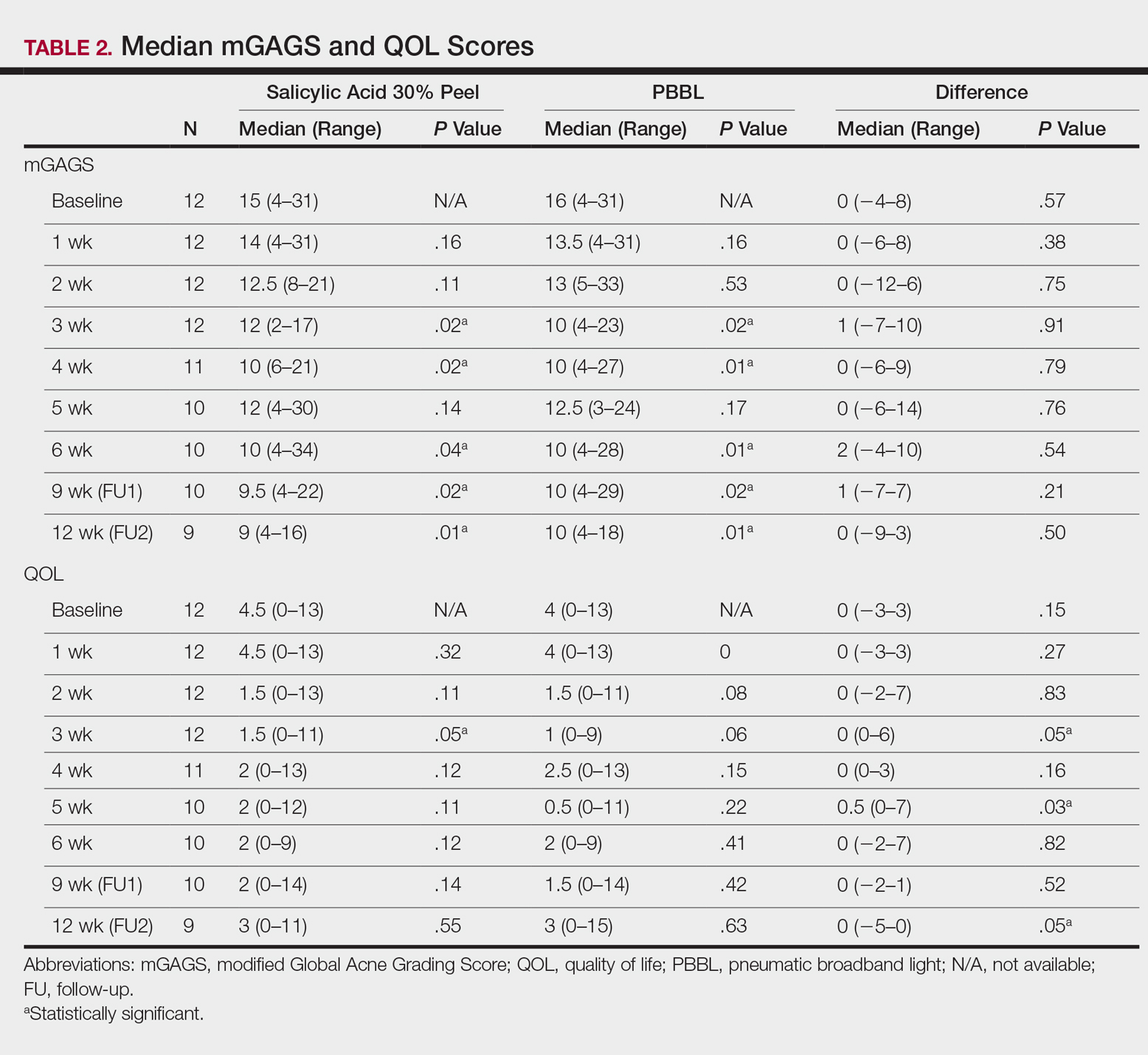

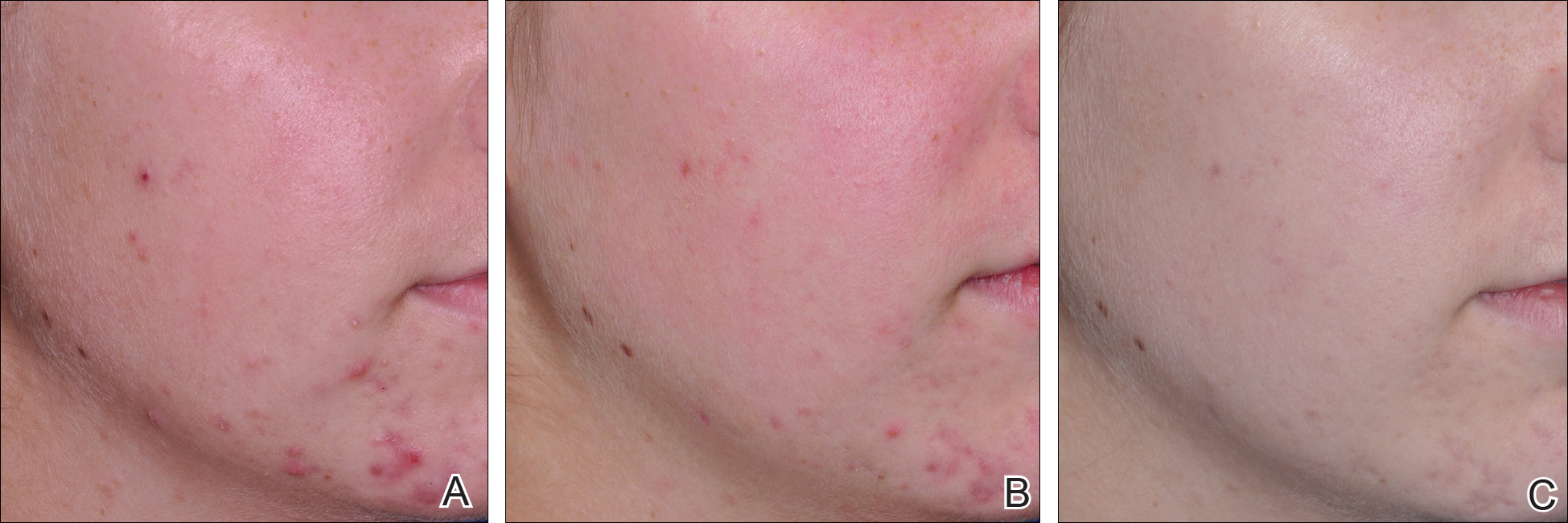

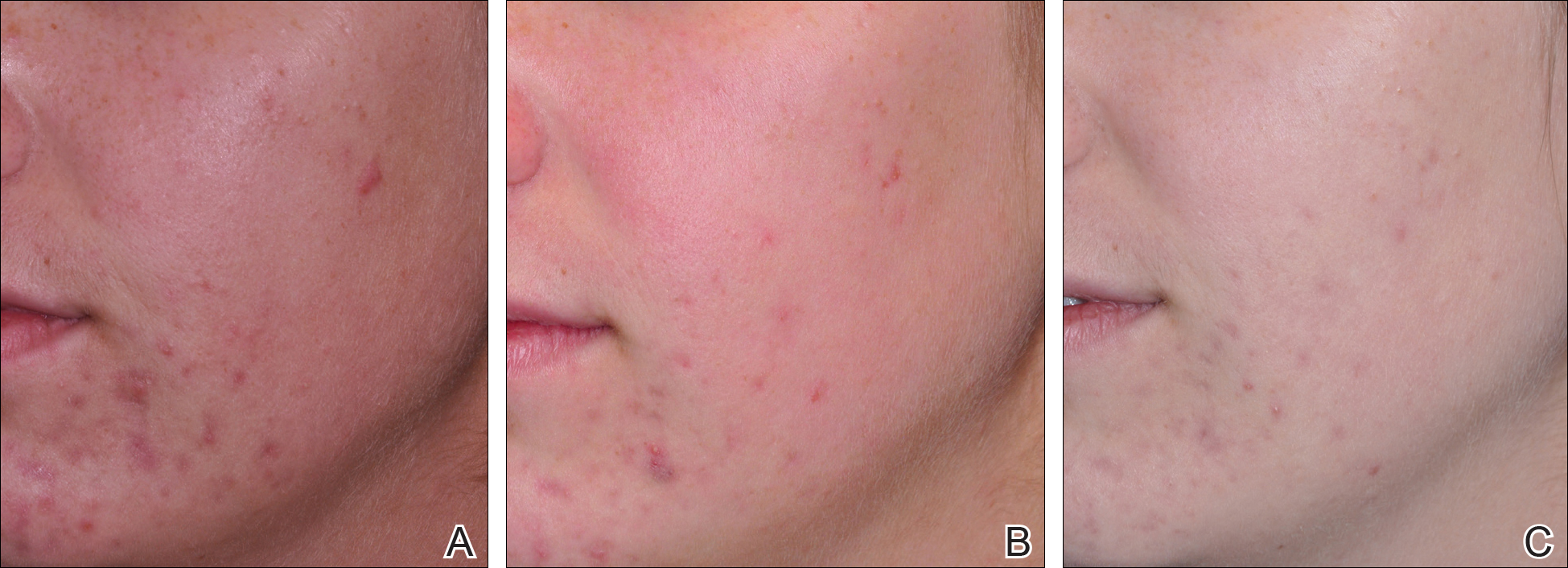

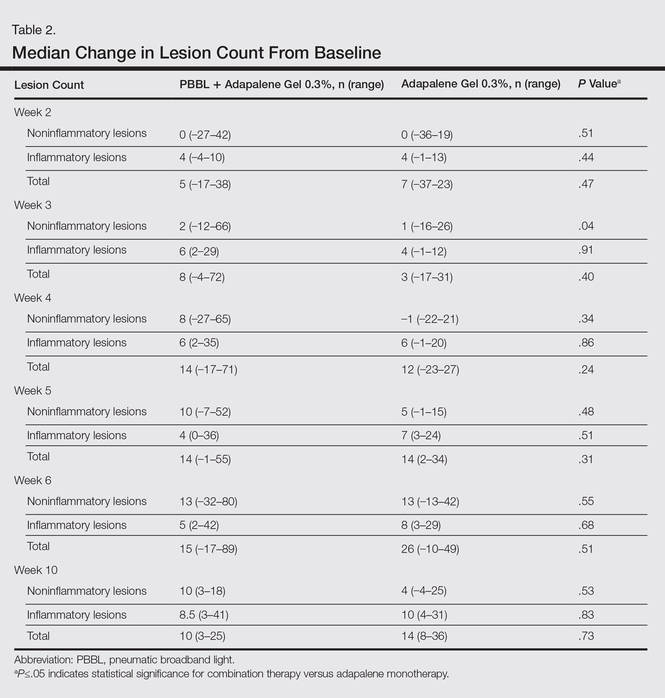

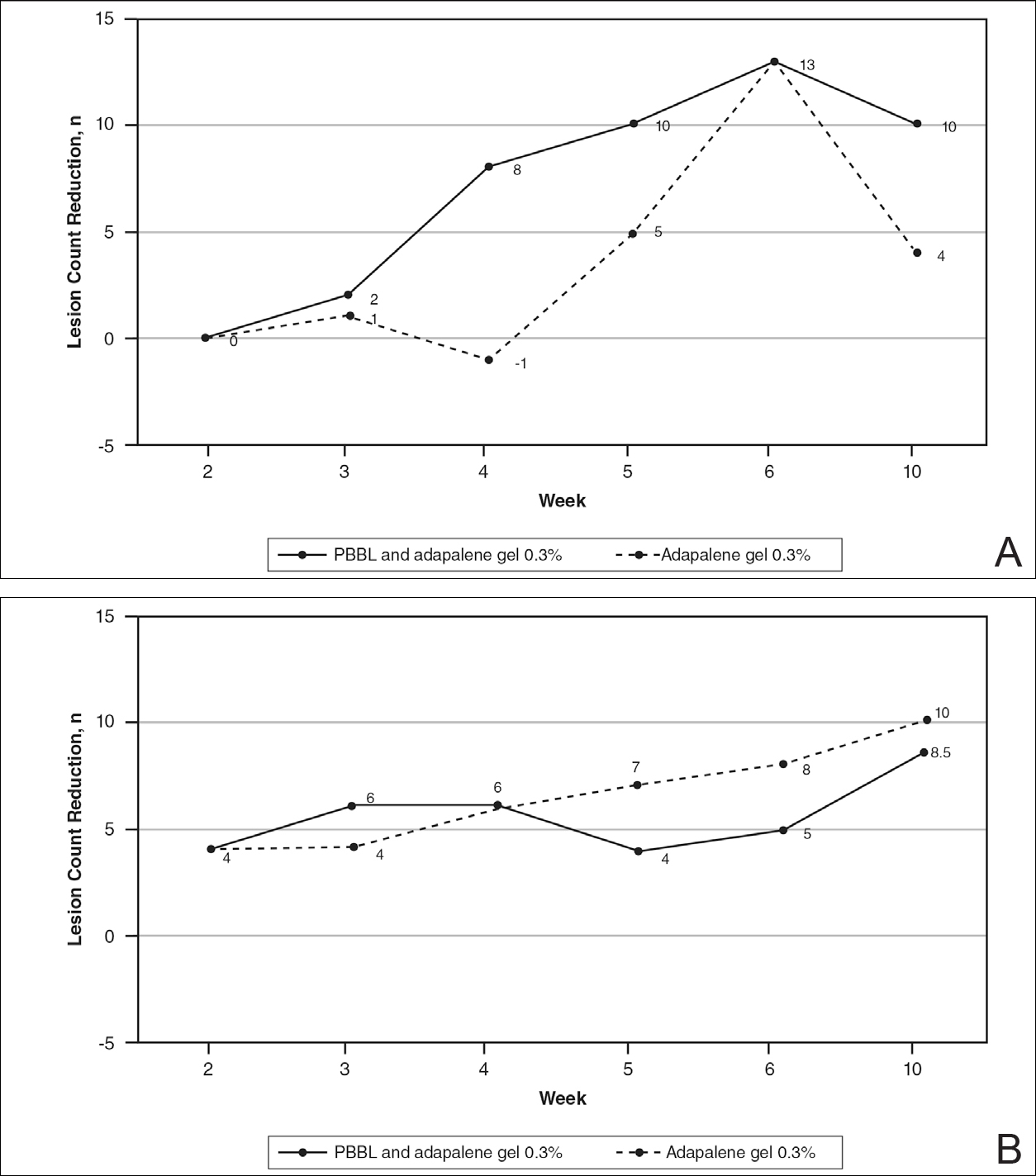

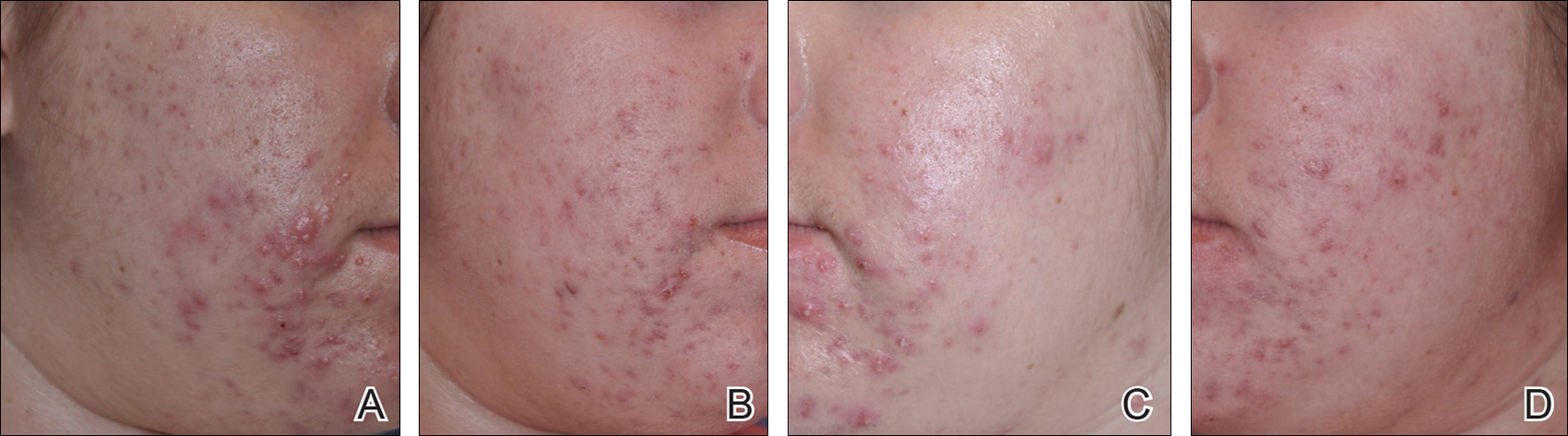

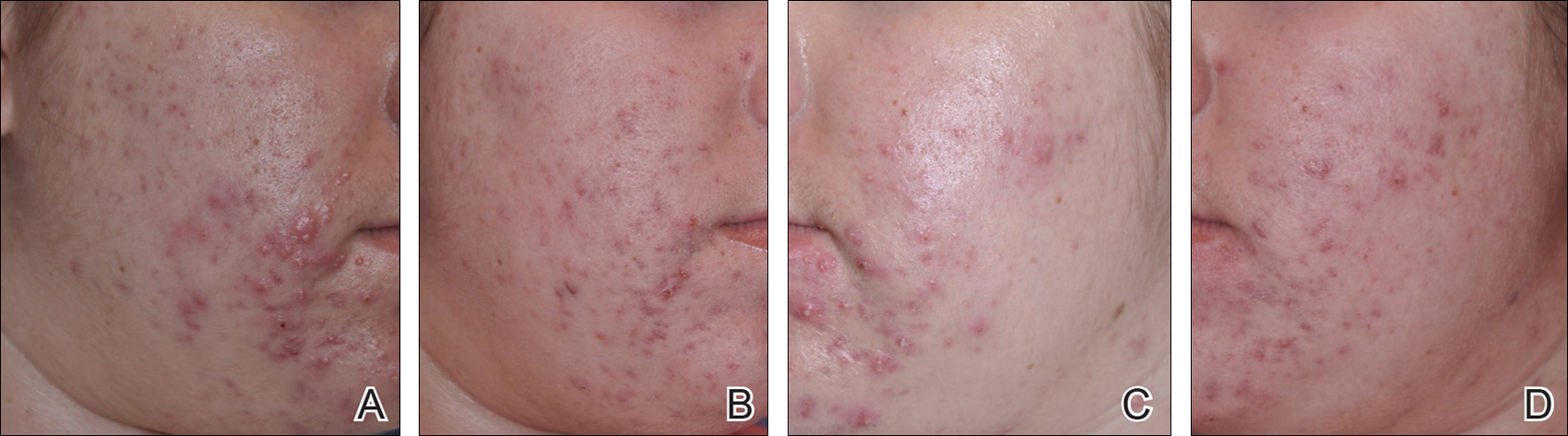

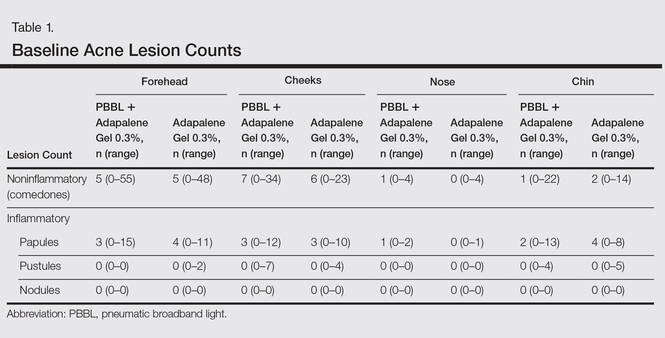

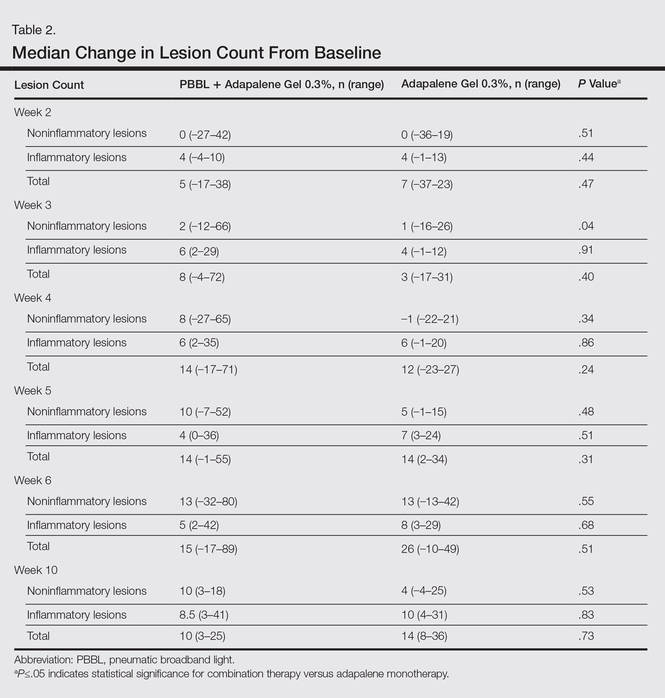

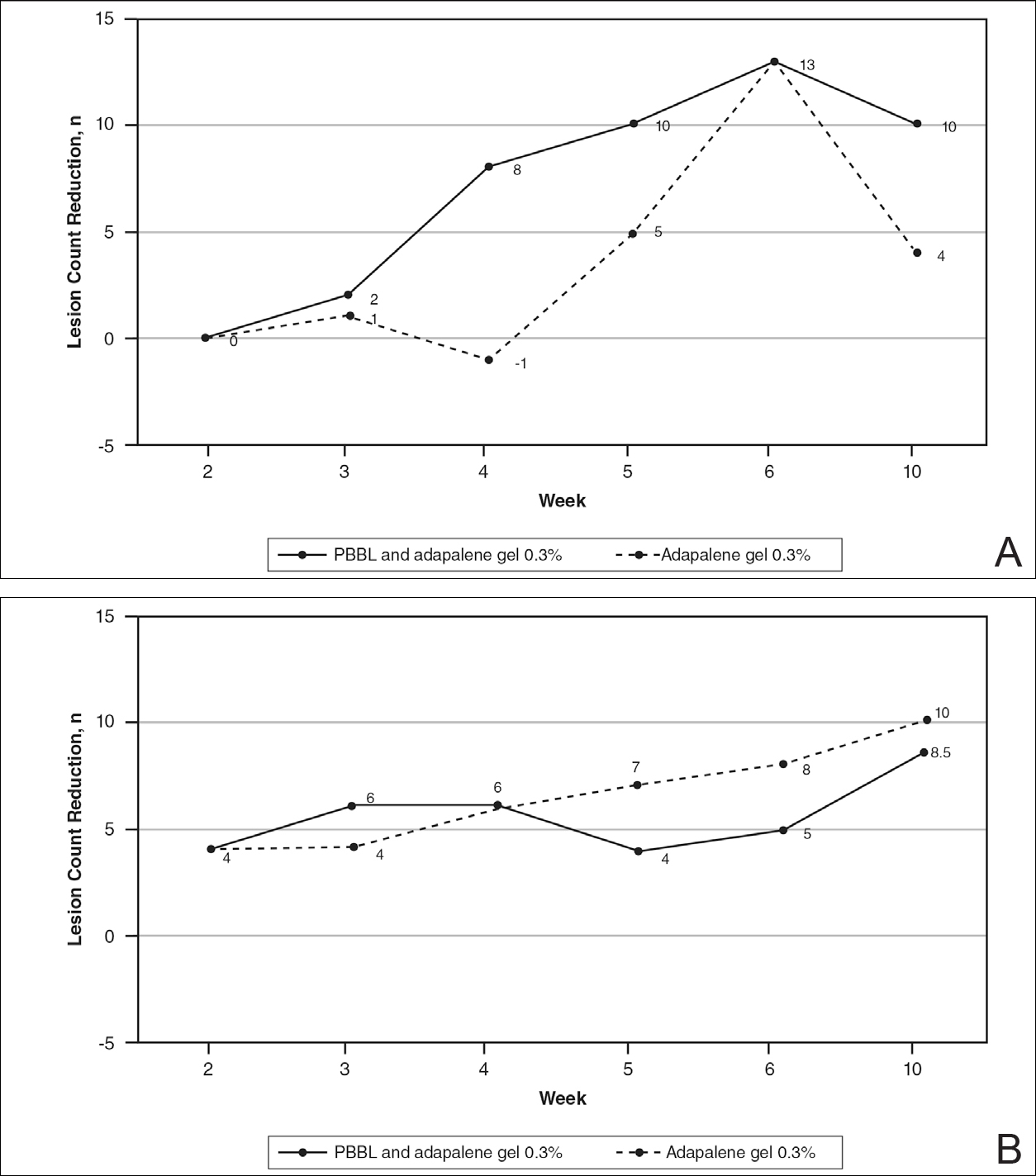

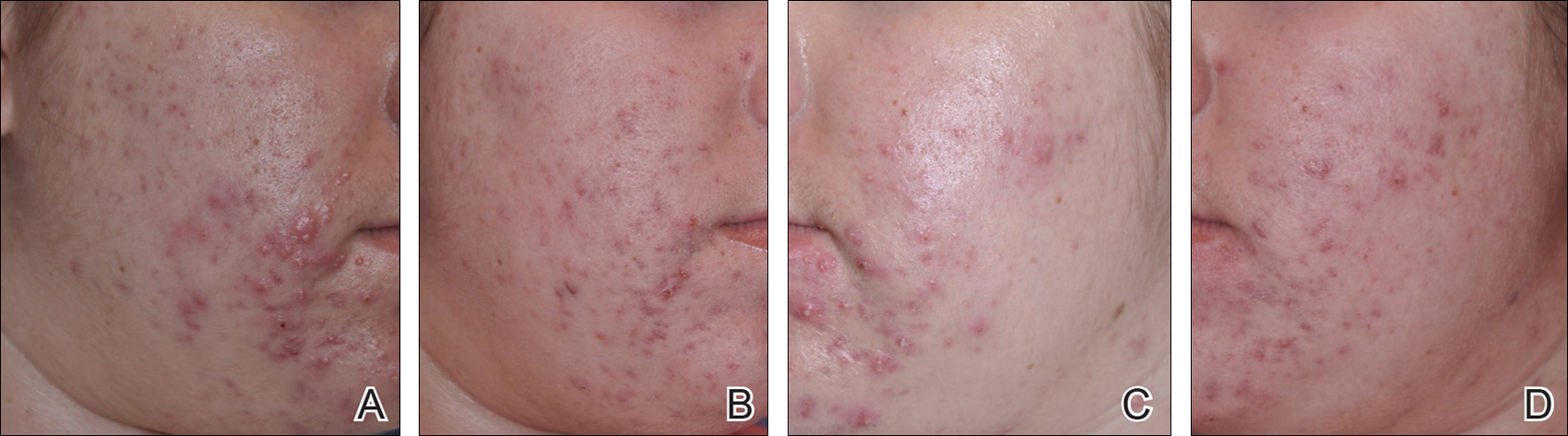

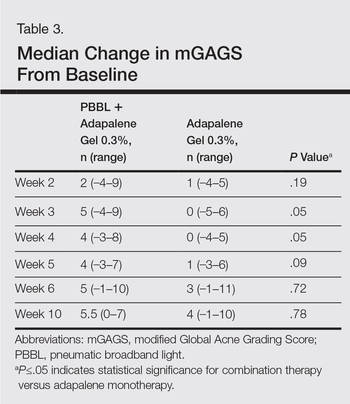

Comparisons between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures for mGAGS at each visit are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in treatment efficacy between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies during the study’s treatment and follow-up events; however, both procedures contributed to a major improvement in acne symptoms by the third treatment session and through to the last follow-up session (P≤.05). Clinical photographs at baseline, at last treatment visit (week 6), and at last follow-up (week 12) are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The results of the acne QOL questionnaire are shown in Table 2. Lower scores reflect a higher QOL. Median QOL scores at each visit ranged from 0.5 to 4.5. There was no significant difference found between the peel agent or PBBL based on the baseline QOL and subsequent visit assessments; however, the differences between the 2 treatments were significant at weeks 3 (P=.05) and 5 (P=.03) of treatment as well as at the last follow-up visit (P=.05).

According to the QOL scores, by the third treatment session participants were more satisfied with their improved acne condition from the PBBL procedure than the salicylic acid 30% peel as demonstrated by a positive range of the QOL assessments between PBBL and salicylic acid 30% peel (as shown in the difference in QOL in Table 2: week 3, 0–6; week 4, 0–3; week 5, 0–7). On the other hand, participants saw more improvement from the salicylic acid 30% peel than from PBBL by the last follow-up evaluation, as the differences in QOL scores between the 2 treatments resulted in a negative range (−5–0).

Safety

Pain assessment by the WBPRS at every visit showed a low pain rating associated with both salicylic acid 30% peel (range, 0–0.5) and PBBL (range, 1.0–1.5) treatments. The median pain score of the salicylic acid 30% peel appeared higher compared to the PBBL treatment, yet a significant difference between both treatments was seen only at weeks 1, 3, and 6 of treatment (P≤.05).

There were no unexpected therapeutic reactions reported in our study, and no participants withdrew from the study due to adverse events. Most participants experienced only mild adverse reactions, including redness, stinging, and a burning sensation on the salicylic acid 30% peel side, which were transient and disappeared in minutes; only redness occurred on the PBBL-treated side.

Comment

Facial acne treatment is challenging, as prolonged and/or severe acne contributes to scarring, declining self-confidence, and undesirable financial consequences. Even though salicylic acid peel is a commonly used acne treatment choice, the PBBL methodology was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration6 and has become an alternative procedure for acne treatment.

The pharmacological effects of salicylic acid are related to its corneocyte desquamation and exfoliative actions, thereby reducing corneocyte cohesion and unclogging follicular pores.16 Salicylic acid has been demonstrated to ameliorate inflammatory acne by its effects on the arachidonic acid cascade.2,4,17 In our study, salicylic acid 30% peel met participants’ satisfaction in acne improvement similar to a study showing a 50% improvement in acne scores after just 2 treatments.18 Our data support and corroborate that salicylic acid 30% peel renders an improvement in acne sequelae reported in several other studies.2,17,18

Pneumatic broadband light has been known to treat acne by the mechanism of pneumatic suction combined with photodynamic therapy using broadband-pulsed light (400–1200 nm).6-8 By applying the pneumatic device, a vacuum is created on the skin to remove sebum contents from follicles, whereas broadband light is emitted simultaneously to destroy bacteria and decrease the inflammatory process.7 During the vacuum process, the skin is stretched to reduce pain and avoid competitive chromophores (eg, hemoglobin), while the broadband light is administered.7 Broadband light encompasses 2 main light spectrums: blue light (415 nm) activates coproporphyrin III, which induces reactive free radicals and singlet oxygen species and has been reported to be the cause of bacterial cell death,19 and red light (633 nm), which renders an increase of fibroblast growth factors to work against the inflammatory processes.20 There are numerous studies showing a reduction of acne lesions after photopneumatic therapy with minimal side effects.6-8

In our study, we compared the efficacy of salicylic acid 30% peel with PBBL in the treatment of acne. Both treatments showed significant reduction of mGAGS compared to baseline starting from week 3 and lasting until week 12. Remarkably, although there were some participants who reported acne recurrence after completing all treatments at week 6, which could have happened when the treatments were ended, the final acne score at week 12 was still significantly lower than baseline. It is clear that the participants continued their acne improvement up to the 6-week follow-up period without any topical or oral medication. We do not propose that either salicylic acid peel or PBBL treatment is a solitary option but speculate that the combination of both treatments may initiate a faster resolution in the disappearance of acne.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in efficacy between salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures at each visit, QOL assessments related to treatment satisfaction did yield significant differences between baseline and the end of treatment. We noticed that participants had more positive attitudes toward the PBBL side at week 3 and week 5 but only mild satisfaction at week 4, as the differences in QOL scores between both treatments showed positive ranging values. This finding is most likely related to the immediate reduction of acne pustules by the PBBL vacuum lysis of these lesions. The differences in the QOL scores between both treatments at week 12 (the last follow-up evaluation) provided opposite findings, which meant patients had nearly even improvement in both PBBL method and salicylic acid 30% peel. Therefore, according to QOL data, acne disappeared quickly with the application of PBBL therapy but reappeared on the PBBL-treated side by the follow-up evaluations, though the acne score between both sides showed no statistically significant difference.

We reason that the PBBL therapy works better than salicylic acid 30% peel because the pneumatic system may help to unclog the pores through mechanical debridement via suctioning versus desquamation from salicylic acid 30% peel. Nonetheless, salicylic acid 30% peel sustained improvement when compared to PBBL through the follow-up periods. Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL treatments are well tolerated and may initiate a faster resolution in the improvement of acne when incorporated with a medical program.

Because of the recurrence of acne after treatments were stopped, additional medical therapies are advised to be used along with this study’s clinical treatments to help mitigate the acne symptoms. These treatments should be considered in patients concerned about antibiotic resistance or those who cannot take oral antibiotics or retinoids. Salicylic acid peel is more accessible and affordable than PBBL, whereas PBBL is slightly more tolerable and less irritating than salicylic acid peel. Nevertheless, the cost of investment in PBBL is quite high—as much as $70,000—and does not include disposable, single-use tips, which cost $30 each. The machine is easy to set up, weighs about 40 lb, and requires little space to store. The average cost per visit of PBBL treatment in office is $150.00 and $75.00 for salicylic acid peel (unpublished data, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 2010). Most patients may select salicylic acid peel over PBBL due to the cost and convenience of the treatment. Neither procedure should be considered as a solitary treatment option but rather as adjunctive procedures combined with oral and/or topical acne medications. After this study’s treatments were stopped and without other medications to maintain treatment effectiveness, the lesions reappeared, trending back toward baseline.

Conclusion

Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures are effective, safe, and well tolerated in treating acne. Although there was no significant difference in the efficacy between both treatments in this study, the small sample size and short follow-up intervals warrant further studies to support the observed outstanding outcomes and should be considered in combination with other medical treatment options. These procedures may be beneficial in holding the patient compliant until their medical therapies have an opportunity to work.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Joyce Okawa, RN (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for her assistance in the submission to the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Rapp DA, Brenes GA, Feldman SR, et al. Anger and acne: implications for quality of life, patient satisfaction and clinical care. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:183-189.

- Zakopoulou N, Kontochristopoulos G. Superficial chemical peels. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:246-253.

- Berson DS, Cohen JL, Rendon MI, et al. Clinical role and application of superficial chemical peels in today’s practice. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:803-811.

- Shalita AR. Treatment of mild and moderate acne vulgaris with salicylic acid in an alcohol-detergent vehicle. Cutis. 1981;28:556-558, 561.

- Sakamoto FH, Lopes JD, Anderson RR. Photodynamic therapy for acne vulgaris: a critical review from basics to clinical practice: part I. acne vulgaris: when and why consider photodynamic therapy? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:183-193; quiz 93-94.

- Gold MH, Biron J. Efficacy of a novel combination of pneumatic energy and broadband light for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:639-642.

- Shamban AT, Enokibori M, Narurkar V, et al. Photopneumatic technology for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:139-145.

- Wanitphakdeedecha R, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Photopneumatic therapy for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:239-241.

- Doshi A, Zaheer A, Stiller MJ. A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:416-418.

- Weiss JW, Shavin J, Davis M. Preliminary results of a nonrandomized, multicenter, open-label study of patient satisfaction after treatment with combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel for mild to moderate acne. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1706-1717.

- Demircay Z, Kus S, Sur H. Predictive factors for acne flare during isotretinoin treatment. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:452-456.

- Gupta MA, Johnson AM, Gupta AK. The development of an Acne Quality of Life scale: reliability, validity, and relation to subjective acne severity in mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:451-456.

- Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9-17.

- Wong DL, Hockenberry-Eaton M, Wilson D, et al. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001:1301.

- Zempsky WT, Robbins B, McKay K. Reduction of topical anesthetic onset time using ultrasound: a randomized controlled trial prior to venipuncture in young children. Pain Med. 2008;9:795-802.

- Imayama S, Ueda S, Isoda M. Histologic changes in the skin of hairless mice following peeling with salicylic acid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1390-1395.

- Lee H, Kim I. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1196-1199.

- Kessler E, Flanagan K, Chia C, et al. Comparison of alpha- and beta-hydroxy acid chemical peels in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:45-50.

- Omi T, Munavalli GS, Kawana S, et al. Ultrastructural evidencefor thermal injury to pilosebaceous units during the treatment of acne using photopneumatic (PPX) therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:7-11.

- Papageorgiou P, Katsambas A, Chu A. Phototherapy with blue (415 nm) and red (660 nm) light in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:973-978.

Facial acne vulgaris is a common skin disease among teenagers and adolescents that may negatively affect self-esteem, perceived facial attractiveness, and social participation.1 Treatments for acne often are multimodal and require the utmost adherence. For these reasons, acne treatments have been challenging to clinicians and patients alike, as patient compliance in maintaining the use of prescribed topical and oral medications remains essential to attain improvement in quality of life (QOL).

Salicylic acid is a popular medicament for acne treatment that frequently is used as monotherapy or as an adjuvant for other acne treatments, especially in patients with oily skin.2 Salicylic acid has a keratolytic effect, causing corneocyte discohesion in clogged pores or congested follicles,2 and it is effective in treating both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne.3,4

Light therapy, particularly with visible light, has been demonstrated to improve acne outcomes.5 Pneumatic broadband light (PBBL) is a therapeutic light treatment in the broadband range (400–1200 nm) that is combined with vacuum suction, which creates a mechanical lysis of thin-walled pustules and dislodges pore impaction. Additionally, the blue light portion of the PBBL spectrum targets endogenous porphyrins in Propionibacterium acnes, resulting in bacterial destruction.6-8

The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of salicylic acid 30% peel versus PBBL in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris.

METHODS

Study Design

This single-blind, randomized, split-face pilot study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). All patients provided informed consent before entering the study. The single-blind evaluation was performed by one dermatologist (C.T.) who examined the participants on every visit prior to PBBL treatment.

Before the study started, participants were randomized for which side of the face was to be treated with PBBL using a number assigned to each participant. Participants received both treatments—salicylic acid 30% peel on one side of the face and PBBL treatment on the other side of the face—once weekly for a total of 6 treatments. They were then asked to return for 2 follow-up evaluations at weeks 3 and 6 following the last treatment session and were instructed not to use any topical or oral acne medications during these follow-up periods.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients aged 18 years and older of any race and sex with noninflammatory papules, some inflammatory papules, and no more than 1 nodule (considered as mild to moderately severe facial acne) were included in the study. Participants had not been on any topical acne medications for at least 1 month and/or oral retinoids for at least 1 year prior to the study period. All women completed urine pregnancy tests prior to the study and were advised to utilize birth control during the study period.

Study Treatments

Salicylic Acid 30% Peel

The participant’s face was cleansed thoroughly before application of salicylic acid 30% (1.5 g/2.5 mL) to half of the face and left on for 5 minutes before being carefully rinsed off by spraying with spring water. Prior to initiating PBBL therapy, the peeled side of the participant’s face was covered with a towel.

Pneumatic Broadband Light

On the other side of the face, PBBL was performed to deliver broadband light within the spectrum range of 400 to 1200 nm at a setting approximately equivalent to a fluence of 4 to 6 J/cm2 and a vacuum setting approximately equivalent to a negative pressure of 3 lb/in2. The power setting was increased on each subsequent visit depending on each participant’s tolerability.

Participants were required to apply a moisturizer and sunscreen to the face and avoid excessive sun exposure between study visits.

Efficacy Evaluation

A comparison of the efficacy of the treatments was determined by clinical evaluation and examining the results of the outcome measurements with the modified Global Acne Grading Score (mGAGS) and Acne QOL Scale during each treatment visit. Facial photographs were taken at each visit.

Modified Global Acne Grading Score

The mGAGS is a modification of the Global Acne Grading Scale (GAGS) that has been used to evaluate acne severity in many studies.9-11 The GAGS considers 6 locations on the face with a grading factor for each location. The local score is obtained by multiplying the factor rated by location with the factor of clinical assessment: local score = factor rated by location × factor rated by clinical assessment. The total score is the sum of the individual local scores (Table 1).

Although the original GAGS incorporated the type and location of the lesions in its calculation, we felt that the number of lesions also was important to add to our grading score. Therefore, we modified the GAGS by adding a factor rated by the number of lesions to improve the accuracy of the test. Accordingly, the local mGAGS scores were calculated by multiplying the location factor by the lesion type and number of lesions factors: local score = location factor × lesion type factor × number of lesions factor.

Acne QOL Questionnaire

Acne QOL was assessed during each visit to demonstrate if the treatment results affected participants’ socialization due to appearance.12 Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire, which consisted of 9 questions with 4 rating answers (0=not affected; 1=mildly affected; 2=moderately affected; 3=markedly affected). A total score of 9 or higher (high score) indicated that acne had a substantial negative impact on the participant, while a total score below 9 (low score) meant acne scarcely impacted social aspects and daily activities of the patient.

Safety Evaluation

The safety of the treatments was evaluated by clinical inspection and by comparing the results of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBPRS)13 after treatment. The WBPRS is used worldwide among researchers to assess pain, particularly in children.14,15 It is composed of 6 faces expressing pain with word descriptions with a corresponding number range reflecting pain severity from 0 to 5 (0=no hurt; 1=hurts little bit; 2=hurts little more; 3=hurts even more; 4=hurts whole lot; 5=hurts worst).13

Statistical Analysis

All variables were presented as the median (range). A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare clinical responses between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies. SPSS software version 12.0 was used for all statistical analysis. A 2-tailed P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Twelve participants (2 males, 10 females) aged 17 to 36 years (median age, 22 years; mean age [SD], 23.33 [1.65] years) with both comedonal and inflammatory acne were enrolled into this study for 6 split-face treatments of salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL at 1-week intervals for 6 weeks, with 2 subsequent follow-up sessions at weeks 3 and 6 posttreatment. Of the 12 participants, 11 were white and 1 was Asian American, with Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV. Nine participants (75%) completed the study. One participant dropped out of the study after the fourth treatment due to a scheduling conflict, and the other 2 participants did not return for follow-up. No participants withdrew from the study because of adverse therapeutic events.

Efficacy Evaluation

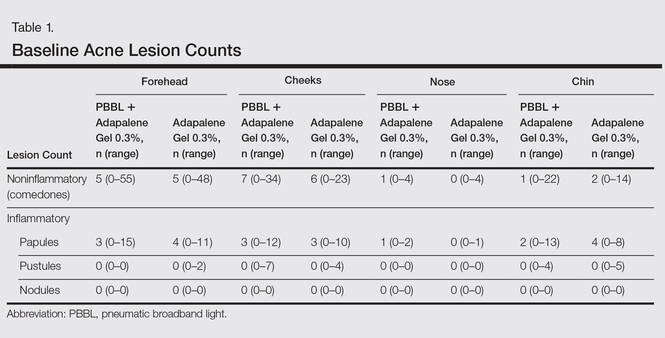

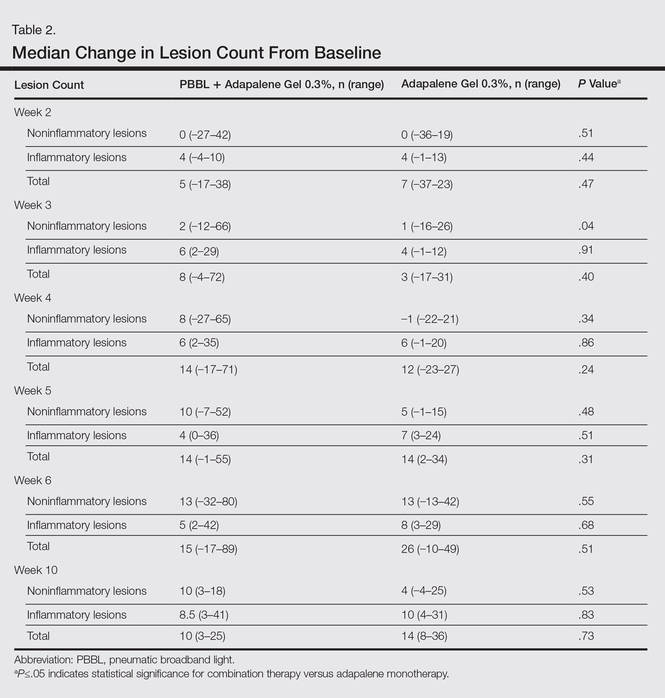

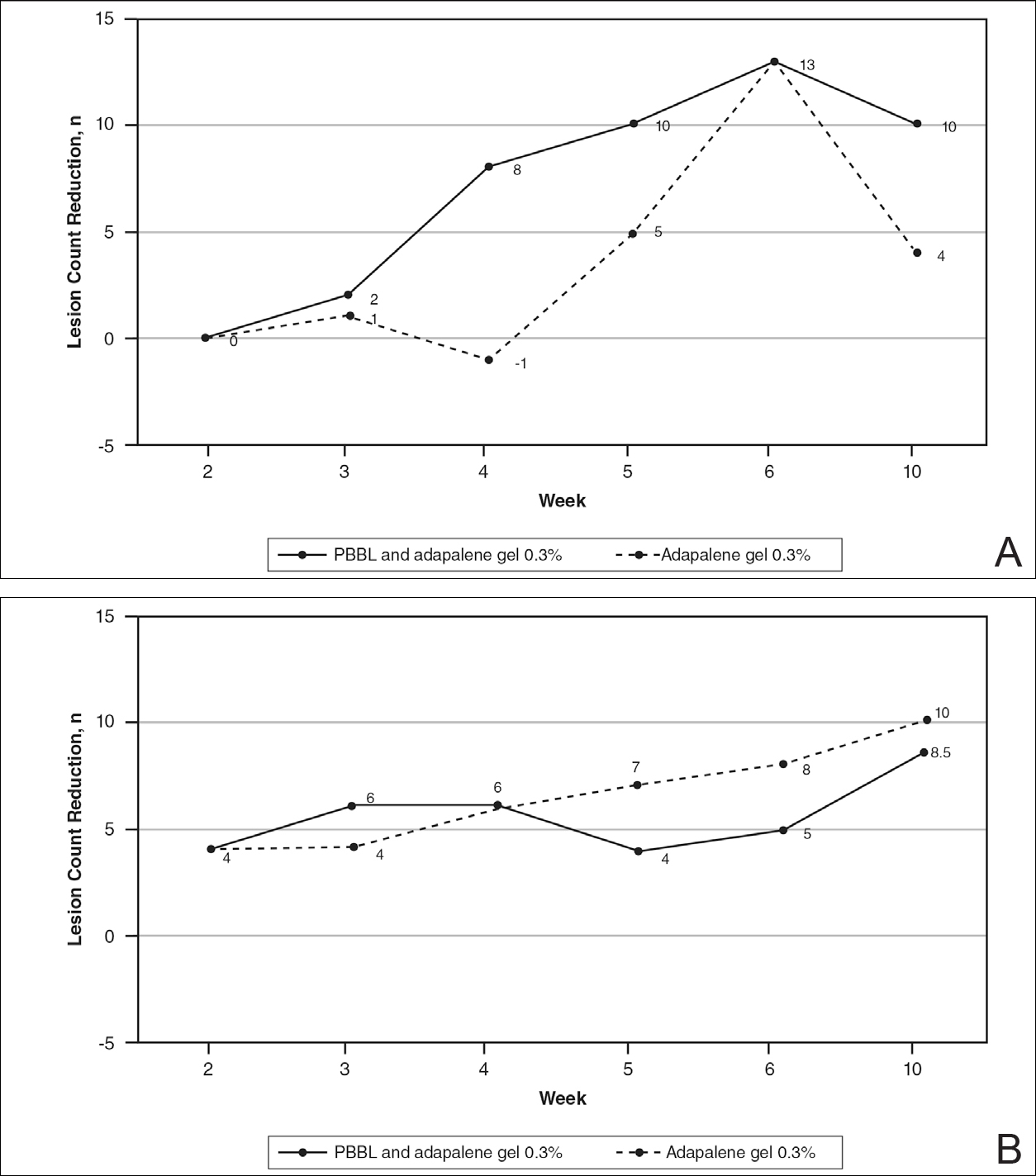

Comparisons between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures for mGAGS at each visit are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in treatment efficacy between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies during the study’s treatment and follow-up events; however, both procedures contributed to a major improvement in acne symptoms by the third treatment session and through to the last follow-up session (P≤.05). Clinical photographs at baseline, at last treatment visit (week 6), and at last follow-up (week 12) are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The results of the acne QOL questionnaire are shown in Table 2. Lower scores reflect a higher QOL. Median QOL scores at each visit ranged from 0.5 to 4.5. There was no significant difference found between the peel agent or PBBL based on the baseline QOL and subsequent visit assessments; however, the differences between the 2 treatments were significant at weeks 3 (P=.05) and 5 (P=.03) of treatment as well as at the last follow-up visit (P=.05).

According to the QOL scores, by the third treatment session participants were more satisfied with their improved acne condition from the PBBL procedure than the salicylic acid 30% peel as demonstrated by a positive range of the QOL assessments between PBBL and salicylic acid 30% peel (as shown in the difference in QOL in Table 2: week 3, 0–6; week 4, 0–3; week 5, 0–7). On the other hand, participants saw more improvement from the salicylic acid 30% peel than from PBBL by the last follow-up evaluation, as the differences in QOL scores between the 2 treatments resulted in a negative range (−5–0).

Safety

Pain assessment by the WBPRS at every visit showed a low pain rating associated with both salicylic acid 30% peel (range, 0–0.5) and PBBL (range, 1.0–1.5) treatments. The median pain score of the salicylic acid 30% peel appeared higher compared to the PBBL treatment, yet a significant difference between both treatments was seen only at weeks 1, 3, and 6 of treatment (P≤.05).

There were no unexpected therapeutic reactions reported in our study, and no participants withdrew from the study due to adverse events. Most participants experienced only mild adverse reactions, including redness, stinging, and a burning sensation on the salicylic acid 30% peel side, which were transient and disappeared in minutes; only redness occurred on the PBBL-treated side.

Comment

Facial acne treatment is challenging, as prolonged and/or severe acne contributes to scarring, declining self-confidence, and undesirable financial consequences. Even though salicylic acid peel is a commonly used acne treatment choice, the PBBL methodology was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration6 and has become an alternative procedure for acne treatment.

The pharmacological effects of salicylic acid are related to its corneocyte desquamation and exfoliative actions, thereby reducing corneocyte cohesion and unclogging follicular pores.16 Salicylic acid has been demonstrated to ameliorate inflammatory acne by its effects on the arachidonic acid cascade.2,4,17 In our study, salicylic acid 30% peel met participants’ satisfaction in acne improvement similar to a study showing a 50% improvement in acne scores after just 2 treatments.18 Our data support and corroborate that salicylic acid 30% peel renders an improvement in acne sequelae reported in several other studies.2,17,18

Pneumatic broadband light has been known to treat acne by the mechanism of pneumatic suction combined with photodynamic therapy using broadband-pulsed light (400–1200 nm).6-8 By applying the pneumatic device, a vacuum is created on the skin to remove sebum contents from follicles, whereas broadband light is emitted simultaneously to destroy bacteria and decrease the inflammatory process.7 During the vacuum process, the skin is stretched to reduce pain and avoid competitive chromophores (eg, hemoglobin), while the broadband light is administered.7 Broadband light encompasses 2 main light spectrums: blue light (415 nm) activates coproporphyrin III, which induces reactive free radicals and singlet oxygen species and has been reported to be the cause of bacterial cell death,19 and red light (633 nm), which renders an increase of fibroblast growth factors to work against the inflammatory processes.20 There are numerous studies showing a reduction of acne lesions after photopneumatic therapy with minimal side effects.6-8

In our study, we compared the efficacy of salicylic acid 30% peel with PBBL in the treatment of acne. Both treatments showed significant reduction of mGAGS compared to baseline starting from week 3 and lasting until week 12. Remarkably, although there were some participants who reported acne recurrence after completing all treatments at week 6, which could have happened when the treatments were ended, the final acne score at week 12 was still significantly lower than baseline. It is clear that the participants continued their acne improvement up to the 6-week follow-up period without any topical or oral medication. We do not propose that either salicylic acid peel or PBBL treatment is a solitary option but speculate that the combination of both treatments may initiate a faster resolution in the disappearance of acne.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in efficacy between salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures at each visit, QOL assessments related to treatment satisfaction did yield significant differences between baseline and the end of treatment. We noticed that participants had more positive attitudes toward the PBBL side at week 3 and week 5 but only mild satisfaction at week 4, as the differences in QOL scores between both treatments showed positive ranging values. This finding is most likely related to the immediate reduction of acne pustules by the PBBL vacuum lysis of these lesions. The differences in the QOL scores between both treatments at week 12 (the last follow-up evaluation) provided opposite findings, which meant patients had nearly even improvement in both PBBL method and salicylic acid 30% peel. Therefore, according to QOL data, acne disappeared quickly with the application of PBBL therapy but reappeared on the PBBL-treated side by the follow-up evaluations, though the acne score between both sides showed no statistically significant difference.

We reason that the PBBL therapy works better than salicylic acid 30% peel because the pneumatic system may help to unclog the pores through mechanical debridement via suctioning versus desquamation from salicylic acid 30% peel. Nonetheless, salicylic acid 30% peel sustained improvement when compared to PBBL through the follow-up periods. Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL treatments are well tolerated and may initiate a faster resolution in the improvement of acne when incorporated with a medical program.

Because of the recurrence of acne after treatments were stopped, additional medical therapies are advised to be used along with this study’s clinical treatments to help mitigate the acne symptoms. These treatments should be considered in patients concerned about antibiotic resistance or those who cannot take oral antibiotics or retinoids. Salicylic acid peel is more accessible and affordable than PBBL, whereas PBBL is slightly more tolerable and less irritating than salicylic acid peel. Nevertheless, the cost of investment in PBBL is quite high—as much as $70,000—and does not include disposable, single-use tips, which cost $30 each. The machine is easy to set up, weighs about 40 lb, and requires little space to store. The average cost per visit of PBBL treatment in office is $150.00 and $75.00 for salicylic acid peel (unpublished data, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 2010). Most patients may select salicylic acid peel over PBBL due to the cost and convenience of the treatment. Neither procedure should be considered as a solitary treatment option but rather as adjunctive procedures combined with oral and/or topical acne medications. After this study’s treatments were stopped and without other medications to maintain treatment effectiveness, the lesions reappeared, trending back toward baseline.

Conclusion

Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures are effective, safe, and well tolerated in treating acne. Although there was no significant difference in the efficacy between both treatments in this study, the small sample size and short follow-up intervals warrant further studies to support the observed outstanding outcomes and should be considered in combination with other medical treatment options. These procedures may be beneficial in holding the patient compliant until their medical therapies have an opportunity to work.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Joyce Okawa, RN (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for her assistance in the submission to the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Facial acne vulgaris is a common skin disease among teenagers and adolescents that may negatively affect self-esteem, perceived facial attractiveness, and social participation.1 Treatments for acne often are multimodal and require the utmost adherence. For these reasons, acne treatments have been challenging to clinicians and patients alike, as patient compliance in maintaining the use of prescribed topical and oral medications remains essential to attain improvement in quality of life (QOL).

Salicylic acid is a popular medicament for acne treatment that frequently is used as monotherapy or as an adjuvant for other acne treatments, especially in patients with oily skin.2 Salicylic acid has a keratolytic effect, causing corneocyte discohesion in clogged pores or congested follicles,2 and it is effective in treating both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne.3,4

Light therapy, particularly with visible light, has been demonstrated to improve acne outcomes.5 Pneumatic broadband light (PBBL) is a therapeutic light treatment in the broadband range (400–1200 nm) that is combined with vacuum suction, which creates a mechanical lysis of thin-walled pustules and dislodges pore impaction. Additionally, the blue light portion of the PBBL spectrum targets endogenous porphyrins in Propionibacterium acnes, resulting in bacterial destruction.6-8

The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of salicylic acid 30% peel versus PBBL in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris.

METHODS

Study Design

This single-blind, randomized, split-face pilot study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). All patients provided informed consent before entering the study. The single-blind evaluation was performed by one dermatologist (C.T.) who examined the participants on every visit prior to PBBL treatment.

Before the study started, participants were randomized for which side of the face was to be treated with PBBL using a number assigned to each participant. Participants received both treatments—salicylic acid 30% peel on one side of the face and PBBL treatment on the other side of the face—once weekly for a total of 6 treatments. They were then asked to return for 2 follow-up evaluations at weeks 3 and 6 following the last treatment session and were instructed not to use any topical or oral acne medications during these follow-up periods.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients aged 18 years and older of any race and sex with noninflammatory papules, some inflammatory papules, and no more than 1 nodule (considered as mild to moderately severe facial acne) were included in the study. Participants had not been on any topical acne medications for at least 1 month and/or oral retinoids for at least 1 year prior to the study period. All women completed urine pregnancy tests prior to the study and were advised to utilize birth control during the study period.

Study Treatments

Salicylic Acid 30% Peel

The participant’s face was cleansed thoroughly before application of salicylic acid 30% (1.5 g/2.5 mL) to half of the face and left on for 5 minutes before being carefully rinsed off by spraying with spring water. Prior to initiating PBBL therapy, the peeled side of the participant’s face was covered with a towel.

Pneumatic Broadband Light

On the other side of the face, PBBL was performed to deliver broadband light within the spectrum range of 400 to 1200 nm at a setting approximately equivalent to a fluence of 4 to 6 J/cm2 and a vacuum setting approximately equivalent to a negative pressure of 3 lb/in2. The power setting was increased on each subsequent visit depending on each participant’s tolerability.

Participants were required to apply a moisturizer and sunscreen to the face and avoid excessive sun exposure between study visits.

Efficacy Evaluation

A comparison of the efficacy of the treatments was determined by clinical evaluation and examining the results of the outcome measurements with the modified Global Acne Grading Score (mGAGS) and Acne QOL Scale during each treatment visit. Facial photographs were taken at each visit.

Modified Global Acne Grading Score

The mGAGS is a modification of the Global Acne Grading Scale (GAGS) that has been used to evaluate acne severity in many studies.9-11 The GAGS considers 6 locations on the face with a grading factor for each location. The local score is obtained by multiplying the factor rated by location with the factor of clinical assessment: local score = factor rated by location × factor rated by clinical assessment. The total score is the sum of the individual local scores (Table 1).

Although the original GAGS incorporated the type and location of the lesions in its calculation, we felt that the number of lesions also was important to add to our grading score. Therefore, we modified the GAGS by adding a factor rated by the number of lesions to improve the accuracy of the test. Accordingly, the local mGAGS scores were calculated by multiplying the location factor by the lesion type and number of lesions factors: local score = location factor × lesion type factor × number of lesions factor.

Acne QOL Questionnaire

Acne QOL was assessed during each visit to demonstrate if the treatment results affected participants’ socialization due to appearance.12 Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire, which consisted of 9 questions with 4 rating answers (0=not affected; 1=mildly affected; 2=moderately affected; 3=markedly affected). A total score of 9 or higher (high score) indicated that acne had a substantial negative impact on the participant, while a total score below 9 (low score) meant acne scarcely impacted social aspects and daily activities of the patient.

Safety Evaluation

The safety of the treatments was evaluated by clinical inspection and by comparing the results of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (WBPRS)13 after treatment. The WBPRS is used worldwide among researchers to assess pain, particularly in children.14,15 It is composed of 6 faces expressing pain with word descriptions with a corresponding number range reflecting pain severity from 0 to 5 (0=no hurt; 1=hurts little bit; 2=hurts little more; 3=hurts even more; 4=hurts whole lot; 5=hurts worst).13

Statistical Analysis

All variables were presented as the median (range). A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare clinical responses between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies. SPSS software version 12.0 was used for all statistical analysis. A 2-tailed P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Twelve participants (2 males, 10 females) aged 17 to 36 years (median age, 22 years; mean age [SD], 23.33 [1.65] years) with both comedonal and inflammatory acne were enrolled into this study for 6 split-face treatments of salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL at 1-week intervals for 6 weeks, with 2 subsequent follow-up sessions at weeks 3 and 6 posttreatment. Of the 12 participants, 11 were white and 1 was Asian American, with Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV. Nine participants (75%) completed the study. One participant dropped out of the study after the fourth treatment due to a scheduling conflict, and the other 2 participants did not return for follow-up. No participants withdrew from the study because of adverse therapeutic events.

Efficacy Evaluation

Comparisons between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures for mGAGS at each visit are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in treatment efficacy between the salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL therapies during the study’s treatment and follow-up events; however, both procedures contributed to a major improvement in acne symptoms by the third treatment session and through to the last follow-up session (P≤.05). Clinical photographs at baseline, at last treatment visit (week 6), and at last follow-up (week 12) are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The results of the acne QOL questionnaire are shown in Table 2. Lower scores reflect a higher QOL. Median QOL scores at each visit ranged from 0.5 to 4.5. There was no significant difference found between the peel agent or PBBL based on the baseline QOL and subsequent visit assessments; however, the differences between the 2 treatments were significant at weeks 3 (P=.05) and 5 (P=.03) of treatment as well as at the last follow-up visit (P=.05).

According to the QOL scores, by the third treatment session participants were more satisfied with their improved acne condition from the PBBL procedure than the salicylic acid 30% peel as demonstrated by a positive range of the QOL assessments between PBBL and salicylic acid 30% peel (as shown in the difference in QOL in Table 2: week 3, 0–6; week 4, 0–3; week 5, 0–7). On the other hand, participants saw more improvement from the salicylic acid 30% peel than from PBBL by the last follow-up evaluation, as the differences in QOL scores between the 2 treatments resulted in a negative range (−5–0).

Safety

Pain assessment by the WBPRS at every visit showed a low pain rating associated with both salicylic acid 30% peel (range, 0–0.5) and PBBL (range, 1.0–1.5) treatments. The median pain score of the salicylic acid 30% peel appeared higher compared to the PBBL treatment, yet a significant difference between both treatments was seen only at weeks 1, 3, and 6 of treatment (P≤.05).

There were no unexpected therapeutic reactions reported in our study, and no participants withdrew from the study due to adverse events. Most participants experienced only mild adverse reactions, including redness, stinging, and a burning sensation on the salicylic acid 30% peel side, which were transient and disappeared in minutes; only redness occurred on the PBBL-treated side.

Comment

Facial acne treatment is challenging, as prolonged and/or severe acne contributes to scarring, declining self-confidence, and undesirable financial consequences. Even though salicylic acid peel is a commonly used acne treatment choice, the PBBL methodology was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration6 and has become an alternative procedure for acne treatment.

The pharmacological effects of salicylic acid are related to its corneocyte desquamation and exfoliative actions, thereby reducing corneocyte cohesion and unclogging follicular pores.16 Salicylic acid has been demonstrated to ameliorate inflammatory acne by its effects on the arachidonic acid cascade.2,4,17 In our study, salicylic acid 30% peel met participants’ satisfaction in acne improvement similar to a study showing a 50% improvement in acne scores after just 2 treatments.18 Our data support and corroborate that salicylic acid 30% peel renders an improvement in acne sequelae reported in several other studies.2,17,18

Pneumatic broadband light has been known to treat acne by the mechanism of pneumatic suction combined with photodynamic therapy using broadband-pulsed light (400–1200 nm).6-8 By applying the pneumatic device, a vacuum is created on the skin to remove sebum contents from follicles, whereas broadband light is emitted simultaneously to destroy bacteria and decrease the inflammatory process.7 During the vacuum process, the skin is stretched to reduce pain and avoid competitive chromophores (eg, hemoglobin), while the broadband light is administered.7 Broadband light encompasses 2 main light spectrums: blue light (415 nm) activates coproporphyrin III, which induces reactive free radicals and singlet oxygen species and has been reported to be the cause of bacterial cell death,19 and red light (633 nm), which renders an increase of fibroblast growth factors to work against the inflammatory processes.20 There are numerous studies showing a reduction of acne lesions after photopneumatic therapy with minimal side effects.6-8

In our study, we compared the efficacy of salicylic acid 30% peel with PBBL in the treatment of acne. Both treatments showed significant reduction of mGAGS compared to baseline starting from week 3 and lasting until week 12. Remarkably, although there were some participants who reported acne recurrence after completing all treatments at week 6, which could have happened when the treatments were ended, the final acne score at week 12 was still significantly lower than baseline. It is clear that the participants continued their acne improvement up to the 6-week follow-up period without any topical or oral medication. We do not propose that either salicylic acid peel or PBBL treatment is a solitary option but speculate that the combination of both treatments may initiate a faster resolution in the disappearance of acne.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in efficacy between salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures at each visit, QOL assessments related to treatment satisfaction did yield significant differences between baseline and the end of treatment. We noticed that participants had more positive attitudes toward the PBBL side at week 3 and week 5 but only mild satisfaction at week 4, as the differences in QOL scores between both treatments showed positive ranging values. This finding is most likely related to the immediate reduction of acne pustules by the PBBL vacuum lysis of these lesions. The differences in the QOL scores between both treatments at week 12 (the last follow-up evaluation) provided opposite findings, which meant patients had nearly even improvement in both PBBL method and salicylic acid 30% peel. Therefore, according to QOL data, acne disappeared quickly with the application of PBBL therapy but reappeared on the PBBL-treated side by the follow-up evaluations, though the acne score between both sides showed no statistically significant difference.

We reason that the PBBL therapy works better than salicylic acid 30% peel because the pneumatic system may help to unclog the pores through mechanical debridement via suctioning versus desquamation from salicylic acid 30% peel. Nonetheless, salicylic acid 30% peel sustained improvement when compared to PBBL through the follow-up periods. Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL treatments are well tolerated and may initiate a faster resolution in the improvement of acne when incorporated with a medical program.

Because of the recurrence of acne after treatments were stopped, additional medical therapies are advised to be used along with this study’s clinical treatments to help mitigate the acne symptoms. These treatments should be considered in patients concerned about antibiotic resistance or those who cannot take oral antibiotics or retinoids. Salicylic acid peel is more accessible and affordable than PBBL, whereas PBBL is slightly more tolerable and less irritating than salicylic acid peel. Nevertheless, the cost of investment in PBBL is quite high—as much as $70,000—and does not include disposable, single-use tips, which cost $30 each. The machine is easy to set up, weighs about 40 lb, and requires little space to store. The average cost per visit of PBBL treatment in office is $150.00 and $75.00 for salicylic acid peel (unpublished data, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 2010). Most patients may select salicylic acid peel over PBBL due to the cost and convenience of the treatment. Neither procedure should be considered as a solitary treatment option but rather as adjunctive procedures combined with oral and/or topical acne medications. After this study’s treatments were stopped and without other medications to maintain treatment effectiveness, the lesions reappeared, trending back toward baseline.

Conclusion

Both salicylic acid 30% peel and PBBL procedures are effective, safe, and well tolerated in treating acne. Although there was no significant difference in the efficacy between both treatments in this study, the small sample size and short follow-up intervals warrant further studies to support the observed outstanding outcomes and should be considered in combination with other medical treatment options. These procedures may be beneficial in holding the patient compliant until their medical therapies have an opportunity to work.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Joyce Okawa, RN (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for her assistance in the submission to the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Rapp DA, Brenes GA, Feldman SR, et al. Anger and acne: implications for quality of life, patient satisfaction and clinical care. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:183-189.

- Zakopoulou N, Kontochristopoulos G. Superficial chemical peels. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:246-253.

- Berson DS, Cohen JL, Rendon MI, et al. Clinical role and application of superficial chemical peels in today’s practice. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:803-811.

- Shalita AR. Treatment of mild and moderate acne vulgaris with salicylic acid in an alcohol-detergent vehicle. Cutis. 1981;28:556-558, 561.

- Sakamoto FH, Lopes JD, Anderson RR. Photodynamic therapy for acne vulgaris: a critical review from basics to clinical practice: part I. acne vulgaris: when and why consider photodynamic therapy? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:183-193; quiz 93-94.