User login

Prurigo nodularis has two disease endotypes, a cluster analysis shows

A cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis (PN) has identified two disease endotypes with inflammatory and noninflammatory biomarker profiles.

said senior author Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is the beginning of personalized medicine in prurigo nodularis.”

He and others have long observed significant clinical heterogeneity both in the presentation of PN – with the nodules in African American patients, for instance, appearing larger, thicker, and more fibrotic – and in patients’ response to immunomodulating and neuromodulating therapies.

To avoid the introduction of bias, the researchers used an unsupervised machine-learning approach to analyze the levels of 12 inflammatory biomarkers in 20 patients with PN and in matched healthy controls. The biomarkers were chosen based on their demonstrated dysregulation in PN and other inflammatory dermatoses.

The researchers then conducted a population-level analysis using multicenter electronic medical record data to explore inflammatory markers and verify findings from the cluster analysis. The study was published online Oct. 27, 2021, in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

One cluster of the 20 patients had higher levels of nine inflammatory biomarkers representing multiple immune axes: Higher interleukin-1 alpha, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, and IL-25. This cluster had a higher percentage of Black patients, a higher severity of itch, and lower quality of life scores, the authors report in the preprint.

The other cluster – without such an inflammatory profile – had fewer Black patients and a higher percentage of patients with myelopathy (e.g. spinal stenosis, spinal trauma, degenerative disc disease). The rates of inflammatory comorbidities and of immune- and neuromodulating treatments at the time of blood draw were relatively equivalent between the two clusters.

In the subsequent population-level analysis, using data from a global health research network of EMRs from almost 50 health care organizations, Black patients with PN were found to have higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and eosinophils, and lower transferrin, than White patients with PN. (The analysis included only Black and White patients.)

There are no Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies for PN, and “clinicians need to be really creative in managing these patients,” Dr. Kwatra said.

“There may be suggestions at the bedside that patients have more immune dysregulation, or maybe I’ll see increased circulating blood eosinophils,” he said. “And there are those who don’t seem to have any immune dysregulation and have more features of neurosensitization ... who may have a history of neck pain or back injury.”

The existence of endotypes in PN suggests that patients may benefit from personalized therapies with either immunomodulating or neuromodulating treatments, he and his colleagues wrote. “Further neuroimmune phenotyping studies of PN may pave the way for a future precision medicine management approach.”

Studies of PN conducted in Europe have been almost exclusively in White patients, Dr. Kwatra noted, even though PN has been shown to disproportionately affect Black and other racial/ethnic-minority patients.

Black patients with PN were found to have the highest all-cause mortality over 20 years post diagnosis in a separate analysis of over 22,000 patients with PN. Using data from the same health research network, Dr. Kwatra and coinvestigators stratified patients by race/ethnicity and compared each subgroup with a corresponding subgroup of similar race/ethnicity to control for inherent differences in mortality.

Overall, patients with PN had higher all-cause mortality than controls (hazard ratio, 1.70), likely because of a high comorbidity burden, they wrote in their research letter. Black patients with PN had the highest mortality (HR, 2.07), followed by White (HR, 1.74) and Hispanic (HR, 1.62) patients.

PN may exacerbate existing racial disparities in the social determinants of health, and Black patients may suffer from greater systemic inflammation, Dr. Kwatra and coauthors wrote. Certainly, he said, these findings, as well as the finding of a distinct inflammatory signature in Black patients with PN, support “that the disease burden is much higher” in these patients.

Dr Kwatra disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for Celldex Therapeutics, Galderma, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals and has received grant funding from several companies. His research is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Grants from the Dermatology Foundation and the Skin of Color Society also helped fund the cluster analysis.

A cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis (PN) has identified two disease endotypes with inflammatory and noninflammatory biomarker profiles.

said senior author Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is the beginning of personalized medicine in prurigo nodularis.”

He and others have long observed significant clinical heterogeneity both in the presentation of PN – with the nodules in African American patients, for instance, appearing larger, thicker, and more fibrotic – and in patients’ response to immunomodulating and neuromodulating therapies.

To avoid the introduction of bias, the researchers used an unsupervised machine-learning approach to analyze the levels of 12 inflammatory biomarkers in 20 patients with PN and in matched healthy controls. The biomarkers were chosen based on their demonstrated dysregulation in PN and other inflammatory dermatoses.

The researchers then conducted a population-level analysis using multicenter electronic medical record data to explore inflammatory markers and verify findings from the cluster analysis. The study was published online Oct. 27, 2021, in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

One cluster of the 20 patients had higher levels of nine inflammatory biomarkers representing multiple immune axes: Higher interleukin-1 alpha, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, and IL-25. This cluster had a higher percentage of Black patients, a higher severity of itch, and lower quality of life scores, the authors report in the preprint.

The other cluster – without such an inflammatory profile – had fewer Black patients and a higher percentage of patients with myelopathy (e.g. spinal stenosis, spinal trauma, degenerative disc disease). The rates of inflammatory comorbidities and of immune- and neuromodulating treatments at the time of blood draw were relatively equivalent between the two clusters.

In the subsequent population-level analysis, using data from a global health research network of EMRs from almost 50 health care organizations, Black patients with PN were found to have higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and eosinophils, and lower transferrin, than White patients with PN. (The analysis included only Black and White patients.)

There are no Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies for PN, and “clinicians need to be really creative in managing these patients,” Dr. Kwatra said.

“There may be suggestions at the bedside that patients have more immune dysregulation, or maybe I’ll see increased circulating blood eosinophils,” he said. “And there are those who don’t seem to have any immune dysregulation and have more features of neurosensitization ... who may have a history of neck pain or back injury.”

The existence of endotypes in PN suggests that patients may benefit from personalized therapies with either immunomodulating or neuromodulating treatments, he and his colleagues wrote. “Further neuroimmune phenotyping studies of PN may pave the way for a future precision medicine management approach.”

Studies of PN conducted in Europe have been almost exclusively in White patients, Dr. Kwatra noted, even though PN has been shown to disproportionately affect Black and other racial/ethnic-minority patients.

Black patients with PN were found to have the highest all-cause mortality over 20 years post diagnosis in a separate analysis of over 22,000 patients with PN. Using data from the same health research network, Dr. Kwatra and coinvestigators stratified patients by race/ethnicity and compared each subgroup with a corresponding subgroup of similar race/ethnicity to control for inherent differences in mortality.

Overall, patients with PN had higher all-cause mortality than controls (hazard ratio, 1.70), likely because of a high comorbidity burden, they wrote in their research letter. Black patients with PN had the highest mortality (HR, 2.07), followed by White (HR, 1.74) and Hispanic (HR, 1.62) patients.

PN may exacerbate existing racial disparities in the social determinants of health, and Black patients may suffer from greater systemic inflammation, Dr. Kwatra and coauthors wrote. Certainly, he said, these findings, as well as the finding of a distinct inflammatory signature in Black patients with PN, support “that the disease burden is much higher” in these patients.

Dr Kwatra disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for Celldex Therapeutics, Galderma, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals and has received grant funding from several companies. His research is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Grants from the Dermatology Foundation and the Skin of Color Society also helped fund the cluster analysis.

A cluster analysis of circulating plasma biomarkers in prurigo nodularis (PN) has identified two disease endotypes with inflammatory and noninflammatory biomarker profiles.

said senior author Shawn G. Kwatra, MD, of the department of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “This is the beginning of personalized medicine in prurigo nodularis.”

He and others have long observed significant clinical heterogeneity both in the presentation of PN – with the nodules in African American patients, for instance, appearing larger, thicker, and more fibrotic – and in patients’ response to immunomodulating and neuromodulating therapies.

To avoid the introduction of bias, the researchers used an unsupervised machine-learning approach to analyze the levels of 12 inflammatory biomarkers in 20 patients with PN and in matched healthy controls. The biomarkers were chosen based on their demonstrated dysregulation in PN and other inflammatory dermatoses.

The researchers then conducted a population-level analysis using multicenter electronic medical record data to explore inflammatory markers and verify findings from the cluster analysis. The study was published online Oct. 27, 2021, in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

One cluster of the 20 patients had higher levels of nine inflammatory biomarkers representing multiple immune axes: Higher interleukin-1 alpha, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, and IL-25. This cluster had a higher percentage of Black patients, a higher severity of itch, and lower quality of life scores, the authors report in the preprint.

The other cluster – without such an inflammatory profile – had fewer Black patients and a higher percentage of patients with myelopathy (e.g. spinal stenosis, spinal trauma, degenerative disc disease). The rates of inflammatory comorbidities and of immune- and neuromodulating treatments at the time of blood draw were relatively equivalent between the two clusters.

In the subsequent population-level analysis, using data from a global health research network of EMRs from almost 50 health care organizations, Black patients with PN were found to have higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, and eosinophils, and lower transferrin, than White patients with PN. (The analysis included only Black and White patients.)

There are no Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies for PN, and “clinicians need to be really creative in managing these patients,” Dr. Kwatra said.

“There may be suggestions at the bedside that patients have more immune dysregulation, or maybe I’ll see increased circulating blood eosinophils,” he said. “And there are those who don’t seem to have any immune dysregulation and have more features of neurosensitization ... who may have a history of neck pain or back injury.”

The existence of endotypes in PN suggests that patients may benefit from personalized therapies with either immunomodulating or neuromodulating treatments, he and his colleagues wrote. “Further neuroimmune phenotyping studies of PN may pave the way for a future precision medicine management approach.”

Studies of PN conducted in Europe have been almost exclusively in White patients, Dr. Kwatra noted, even though PN has been shown to disproportionately affect Black and other racial/ethnic-minority patients.

Black patients with PN were found to have the highest all-cause mortality over 20 years post diagnosis in a separate analysis of over 22,000 patients with PN. Using data from the same health research network, Dr. Kwatra and coinvestigators stratified patients by race/ethnicity and compared each subgroup with a corresponding subgroup of similar race/ethnicity to control for inherent differences in mortality.

Overall, patients with PN had higher all-cause mortality than controls (hazard ratio, 1.70), likely because of a high comorbidity burden, they wrote in their research letter. Black patients with PN had the highest mortality (HR, 2.07), followed by White (HR, 1.74) and Hispanic (HR, 1.62) patients.

PN may exacerbate existing racial disparities in the social determinants of health, and Black patients may suffer from greater systemic inflammation, Dr. Kwatra and coauthors wrote. Certainly, he said, these findings, as well as the finding of a distinct inflammatory signature in Black patients with PN, support “that the disease burden is much higher” in these patients.

Dr Kwatra disclosed that he is an advisory board member/consultant for Celldex Therapeutics, Galderma, Incyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals and has received grant funding from several companies. His research is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Grants from the Dermatology Foundation and the Skin of Color Society also helped fund the cluster analysis.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Lung transplantation in the era of COVID-19: New issues and paradigms

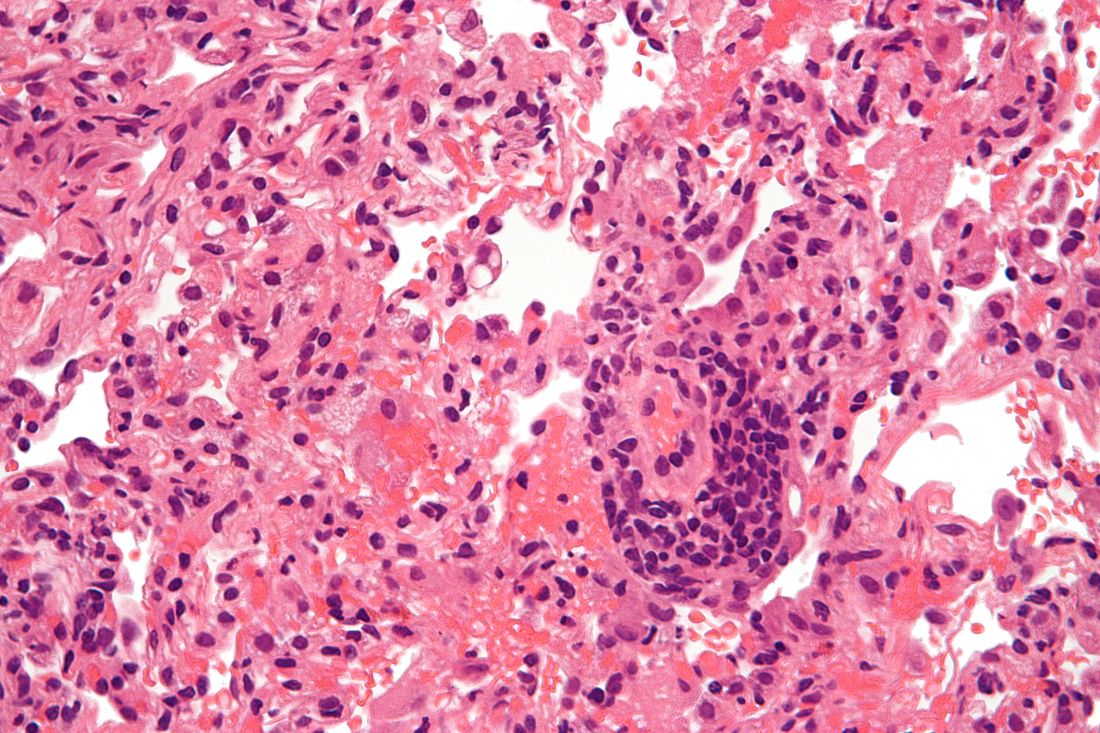

Data is sparse thus far, but there is concern in lung transplant medicine about the long-term risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and a potentially shortened longevity of transplanted lungs in recipients who become ill with COVID-19.

“My fear is that we’re potentially sitting on this iceberg worth of people who, come 6 months or a year from [the acute phase of] their COVID illness, will in fact have earlier and progressive, chronic rejection,” said Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of medicine in transplant infectious disease at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Lower respiratory viral infections have long been concerning for lung transplant recipients given their propensity to cause scarring, a decline in lung function, and a heightened risk of allograft rejection. Time will tell whether lung transplant recipients who survive COVID-19 follow a similar path, or one that is worse, he said.

Short-term data

Outcomes beyond hospitalization and acute illness for lung transplant recipients affected by COVID-19 have been reported in the literature by only a few lung transplant programs. These reports – as well as anecdotal experiences being informally shared among transplant programs – have raised the specter of more severe dysfunction following the acute phase and more early CLAD, said Tathagat Narula, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and a consultant in lung transplantation at the Mayo Clinic’s Jacksonville program.

“The available data cover only 3-6 months out. We don’t know what will happen in the next 6 months and beyond,” Dr. Narula said in an interview.

The risks of COVID-19 in already-transplanted patients and issues relating to the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination are just some of the challenges of lung transplant medicine in the era of SARS-CoV-2. “COVID-19,” said Dr. Narula, “has completely changed the way we practice lung transplant medicine – the way we’re looking both at our recipients and our donors.”

Potential donors are being evaluated with lower respiratory SARS-CoV-2 testing and an abundance of caution. And patients with severe COVID-19 affecting their own lungs are roundly expected to drive up lung transplant volume in the near future. “The whole paradigm has changed,” Dr. Narula said.

Post-acute trajectories

A chart review study published in October by the lung transplant team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, covered 44 consecutive survivors at a median follow-up of 4.5 months from hospital discharge or acute illness (the survival rate was 83.3%). Patients had significantly impaired functional status, and 18 of the 44 (40.9%) had a significant and persistent loss of forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (>10% from pre–COVID-19 baseline).

Three patients met the criteria for new CLAD after COVID-19 infection, with all three classified as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) phenotype.

Moreover, the majority of COVID-19 survivors who had CT chest scans (22 of 28) showed persistent parenchymal opacities – a finding that, regardless of symptomatology, suggests persistent allograft injury, said Amit Banga, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program in UT Southwestern’s lung transplant program.

“The implication is that there may be long-term consequences of COVID-19, perhaps related to some degree of ongoing inflammation and damage,” said Dr. Banga, a coauthor of the postinfection outcomes paper.

The UT Southwestern lung transplant program, which normally performs 60-80 transplants a year, began routine CT scanning 4-5 months into the pandemic, after “stumbling into a few patients who had no symptoms indicative of COVID pneumonia and no changes on an x-ray but significant involvement on a CT,” he said.

Without routine scanning in the general population of COVID-19 patients, Dr. Banga noted, “we’re limited in convincingly saying that COVID is uniquely doing this to lung transplant recipients.” Nor can they conclude that SARS-CoV-2 is unique from other respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in this regard. (The program has added CT scanning to its protocol for lung transplant recipients afflicted with other respiratory viruses to learn more.)

However, in the big picture, COVID-19 has proven to be far worse for lung transplant recipients than illness with other respiratory viruses, including RSV. “Patients have more frequent and greater loss of lung function, and worse debility from the acute illness,” Dr. Banga said.

“The cornerstones of treatment of both these viruses are very similar, but both the in-hospital course and the postdischarge outcomes are significantly different.”

In an initial paper published in September 2021, Dr. Banga and colleagues compared their first 25 lung transplant patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 with a historical cohort of 36 patients with RSV treated during 2016-2018.

Patients with COVID-19 had significantly worse morbidity and mortality, including worse postinfection lung function loss, functional decline, and 3-month survival.

More time, he said, will shed light on the risks of CLAD and the long-term potential for recovery of lung function. Currently, at UT Southwestern, it appears that patients who survive acute illness and the “first 3-6 months after COVID-19, when we’re seeing all the postinfection morbidity, may [enter] a period of stability,” Dr. Banga said.

Overall, he said, patients in their initial cohort are “holding steady” without unusual morbidity, readmissions, or “other setbacks to their allografts.”

At the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, which normally performs 40-50 lung transplants a year, transplant physicians have similarly observed significant declines in lung function beyond the acute phase of COVID-19. “Anecdotally, we’re seeing that some patients are beginning to recover some of their lung function, while others have not,” said Dr. Narula. “And we don’t have predictors as to who will progress to CLAD. It’s a big knowledge gap.”

Dr. Narula noted that patients with restrictive allograft syndrome, such as those reported by the UT Southwestern team, “have scarring of the lung and a much worse prognosis than the obstructive type of chronic rejection.” Whether there’s a role for antifibrotic therapy is a question worthy of research.

In UT Southwestern’s analysis, persistently lower absolute lymphocyte counts (< 600/dL) and higher ferritin levels (>150 ng/mL) at the time of hospital discharge were independently associated with significant lung function loss. This finding, reported in their October paper, has helped guide their management practices, Dr. Banga said.

“Persistently elevated ferritin may indicate ongoing inflammation at the allograft level,” he said. “We now send [such patients] home on a longer course of oral corticosteroids.”

At the front end of care for infected lung transplant recipients, Dr. Banga said that his team and physicians at other lung transplant programs are holding the cell-cycle inhibitor component of patients’ maintenance immunosuppression therapy (commonly mycophenolate or azathioprine) once infection is diagnosed to maximize chances of a better outcome.

“There may be variation on how long [the regimens are adjusted],” he said. “We changed our duration from 4 weeks to 2 due to patients developing a rebound worsening in the third and fourth week of acute illness.”

There is significant variation from institution to institution in how viral infections are managed in lung transplant recipients, he and Dr. Narula said. “Our numbers are so small in lung transplant, and we don’t have standardized protocols – it’s one of the biggest challenges in our field,” said Dr. Narula.

Vaccination issues, evaluation of donors

Whether or not immunosuppression regimens should be adjusted prior to vaccination is a controversial question, but is “an absolutely valid one” and is currently being studied in at least one National Institutes of Health–funded trial involving solid organ transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe.

“Some have jumped to the conclusion [based on some earlier data] that they should reduce immunosuppression regimens for everyone at the time of vaccination ... but I don’t know the answer yet,” he said. “Balancing staying rejection free with potentially gaining more immune response is complicated ... and it may depend on where the pandemic is going in your area and other factors.”

Reductions aside, Dr. Wolfe tells lung transplant recipients that, based on his approximation of a number of different studies in solid organ transplant recipients, approximately 40%-50% of patients who are immunized with two doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will develop meaningful antibody levels – and that this rises to 50%-60% after a third dose.

It is difficult to glean from available studies the level of vaccine response for lung transplant recipients specifically. But given that their level of maintenance immunosuppression is higher than for recipients of other donor organs, “as a broad sweep, lung transplant recipients tend to be lower in the pecking order of response,” he said.

Still, “there’s a lot to gain,” he said, pointing to a recent study from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2021 Nov 5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e3) showing that effectiveness of mRNA vaccination against COVID-19–associated hospitalization was 77% among immunocompromised adults (compared with 90% in immunocompetent adults).

“This is good vindication to keep vaccinating,” he said, “and perhaps speaks to how difficult it is to assess the vaccine response [through measurement of antibody only].”

Neither Duke University’s transplant program, which performed 100-120 lung transplants a year pre-COVID, nor the programs at UT Southwestern or the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville require that solid organ transplant candidates be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in order to receive transplants, as some other transplant programs have done. (When asked about the issue, Dr. Banga and Dr. Narula each said that they have had no or little trouble convincing patients awaiting lung transplants of the need for COVID-19 vaccination.)

In an August statement, the American Society of Transplantation recommended vaccination for all solid organ transplant recipients, preferably prior to transplantation, and said that it “support[s] the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination.”

The Society is not tracking centers’ vaccination policies. But Kaiser Health News reported in October that a growing number of transplant programs, such as UCHealth in Denver and UW Medicine in Seattle, have decided to either bar patients who refuse to be vaccinated from receiving transplants or give them lower priority on waitlists.

Potential lung donors, meanwhile, must be evaluated with lower respiratory COVID-19 testing, with results available prior to transplantation, according to policy developed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and effective in May 2021. The policy followed three published cases of donor-derived COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe, who wrote about use of COVID-positive donors in an editorial published in October.

In each case, the donor had a negative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab at the time of organ procurement but was later found to have the virus on bronchoalveolar lavage, he said.

(The use of other organs from COVID-positive donors is appearing thus far to be safe, Dr. Wolfe noted. In the editorial, he references 13 cases of solid organ transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors into noninfected recipients; none of the 13 transplant recipients developed COVID-19).

Some questions remain, such as how many lower respiratory tests should be run, and how donors should be evaluated in cases of discordant results. Dr. Banga shared the case of a donor with one positive lower respiratory test result followed by two negative results. After internal debate, and consideration of potential false positives and other issues, the team at UT Southwestern decided to decline the donor, Dr. Banga said.

Other programs are likely making similar, appropriately cautious decisions, said Dr. Wolfe. “There’s no way in real-time donor evaluation to know whether the positive test is active virus that could infect the recipient and replicate ... or whether it’s [picking up] inactive or dead fragments of virus that was there several weeks ago. Our tests don’t differentiate that.”

Transplants in COVID-19 patients

Decision-making about lung transplant candidacy among patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome is complex and in need of a new paradigm.

“Some of these patients have the potential to recover, and they’re going to recover way later than what we’re used to,” said Dr. Banga. “We can’t extrapolate for COVID ARDS what we’ve learned for any other virus-related ARDS.”

Dr. Narula also has recently seen at least one COVID-19 patient on ECMO and under evaluation for transplantation recover. “We do not want to transplant too early,” he said, noting that there is consensus that lung transplant should be pursued only when the damage is deemed irreversible clinically and radiologically in the best judgment of the team. Still, “for many of these patients the only exit route will be lung transplants. For the next 12-24 months, a significant proportion of our lung transplant patients will have had post-COVID–related lung damage.”

As of October 2021, 233 lung transplants had been performed in the United States in recipients whose primary diagnosis was reported as COVID related, said Anne Paschke, media relations specialist with the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Dr. Banga, Dr. Wolfe, and Dr. Narula reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

Data is sparse thus far, but there is concern in lung transplant medicine about the long-term risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and a potentially shortened longevity of transplanted lungs in recipients who become ill with COVID-19.

“My fear is that we’re potentially sitting on this iceberg worth of people who, come 6 months or a year from [the acute phase of] their COVID illness, will in fact have earlier and progressive, chronic rejection,” said Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of medicine in transplant infectious disease at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Lower respiratory viral infections have long been concerning for lung transplant recipients given their propensity to cause scarring, a decline in lung function, and a heightened risk of allograft rejection. Time will tell whether lung transplant recipients who survive COVID-19 follow a similar path, or one that is worse, he said.

Short-term data

Outcomes beyond hospitalization and acute illness for lung transplant recipients affected by COVID-19 have been reported in the literature by only a few lung transplant programs. These reports – as well as anecdotal experiences being informally shared among transplant programs – have raised the specter of more severe dysfunction following the acute phase and more early CLAD, said Tathagat Narula, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and a consultant in lung transplantation at the Mayo Clinic’s Jacksonville program.

“The available data cover only 3-6 months out. We don’t know what will happen in the next 6 months and beyond,” Dr. Narula said in an interview.

The risks of COVID-19 in already-transplanted patients and issues relating to the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination are just some of the challenges of lung transplant medicine in the era of SARS-CoV-2. “COVID-19,” said Dr. Narula, “has completely changed the way we practice lung transplant medicine – the way we’re looking both at our recipients and our donors.”

Potential donors are being evaluated with lower respiratory SARS-CoV-2 testing and an abundance of caution. And patients with severe COVID-19 affecting their own lungs are roundly expected to drive up lung transplant volume in the near future. “The whole paradigm has changed,” Dr. Narula said.

Post-acute trajectories

A chart review study published in October by the lung transplant team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, covered 44 consecutive survivors at a median follow-up of 4.5 months from hospital discharge or acute illness (the survival rate was 83.3%). Patients had significantly impaired functional status, and 18 of the 44 (40.9%) had a significant and persistent loss of forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (>10% from pre–COVID-19 baseline).

Three patients met the criteria for new CLAD after COVID-19 infection, with all three classified as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) phenotype.

Moreover, the majority of COVID-19 survivors who had CT chest scans (22 of 28) showed persistent parenchymal opacities – a finding that, regardless of symptomatology, suggests persistent allograft injury, said Amit Banga, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program in UT Southwestern’s lung transplant program.

“The implication is that there may be long-term consequences of COVID-19, perhaps related to some degree of ongoing inflammation and damage,” said Dr. Banga, a coauthor of the postinfection outcomes paper.

The UT Southwestern lung transplant program, which normally performs 60-80 transplants a year, began routine CT scanning 4-5 months into the pandemic, after “stumbling into a few patients who had no symptoms indicative of COVID pneumonia and no changes on an x-ray but significant involvement on a CT,” he said.

Without routine scanning in the general population of COVID-19 patients, Dr. Banga noted, “we’re limited in convincingly saying that COVID is uniquely doing this to lung transplant recipients.” Nor can they conclude that SARS-CoV-2 is unique from other respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in this regard. (The program has added CT scanning to its protocol for lung transplant recipients afflicted with other respiratory viruses to learn more.)

However, in the big picture, COVID-19 has proven to be far worse for lung transplant recipients than illness with other respiratory viruses, including RSV. “Patients have more frequent and greater loss of lung function, and worse debility from the acute illness,” Dr. Banga said.

“The cornerstones of treatment of both these viruses are very similar, but both the in-hospital course and the postdischarge outcomes are significantly different.”

In an initial paper published in September 2021, Dr. Banga and colleagues compared their first 25 lung transplant patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 with a historical cohort of 36 patients with RSV treated during 2016-2018.

Patients with COVID-19 had significantly worse morbidity and mortality, including worse postinfection lung function loss, functional decline, and 3-month survival.

More time, he said, will shed light on the risks of CLAD and the long-term potential for recovery of lung function. Currently, at UT Southwestern, it appears that patients who survive acute illness and the “first 3-6 months after COVID-19, when we’re seeing all the postinfection morbidity, may [enter] a period of stability,” Dr. Banga said.

Overall, he said, patients in their initial cohort are “holding steady” without unusual morbidity, readmissions, or “other setbacks to their allografts.”

At the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, which normally performs 40-50 lung transplants a year, transplant physicians have similarly observed significant declines in lung function beyond the acute phase of COVID-19. “Anecdotally, we’re seeing that some patients are beginning to recover some of their lung function, while others have not,” said Dr. Narula. “And we don’t have predictors as to who will progress to CLAD. It’s a big knowledge gap.”

Dr. Narula noted that patients with restrictive allograft syndrome, such as those reported by the UT Southwestern team, “have scarring of the lung and a much worse prognosis than the obstructive type of chronic rejection.” Whether there’s a role for antifibrotic therapy is a question worthy of research.

In UT Southwestern’s analysis, persistently lower absolute lymphocyte counts (< 600/dL) and higher ferritin levels (>150 ng/mL) at the time of hospital discharge were independently associated with significant lung function loss. This finding, reported in their October paper, has helped guide their management practices, Dr. Banga said.

“Persistently elevated ferritin may indicate ongoing inflammation at the allograft level,” he said. “We now send [such patients] home on a longer course of oral corticosteroids.”

At the front end of care for infected lung transplant recipients, Dr. Banga said that his team and physicians at other lung transplant programs are holding the cell-cycle inhibitor component of patients’ maintenance immunosuppression therapy (commonly mycophenolate or azathioprine) once infection is diagnosed to maximize chances of a better outcome.

“There may be variation on how long [the regimens are adjusted],” he said. “We changed our duration from 4 weeks to 2 due to patients developing a rebound worsening in the third and fourth week of acute illness.”

There is significant variation from institution to institution in how viral infections are managed in lung transplant recipients, he and Dr. Narula said. “Our numbers are so small in lung transplant, and we don’t have standardized protocols – it’s one of the biggest challenges in our field,” said Dr. Narula.

Vaccination issues, evaluation of donors

Whether or not immunosuppression regimens should be adjusted prior to vaccination is a controversial question, but is “an absolutely valid one” and is currently being studied in at least one National Institutes of Health–funded trial involving solid organ transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe.

“Some have jumped to the conclusion [based on some earlier data] that they should reduce immunosuppression regimens for everyone at the time of vaccination ... but I don’t know the answer yet,” he said. “Balancing staying rejection free with potentially gaining more immune response is complicated ... and it may depend on where the pandemic is going in your area and other factors.”

Reductions aside, Dr. Wolfe tells lung transplant recipients that, based on his approximation of a number of different studies in solid organ transplant recipients, approximately 40%-50% of patients who are immunized with two doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will develop meaningful antibody levels – and that this rises to 50%-60% after a third dose.

It is difficult to glean from available studies the level of vaccine response for lung transplant recipients specifically. But given that their level of maintenance immunosuppression is higher than for recipients of other donor organs, “as a broad sweep, lung transplant recipients tend to be lower in the pecking order of response,” he said.

Still, “there’s a lot to gain,” he said, pointing to a recent study from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2021 Nov 5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e3) showing that effectiveness of mRNA vaccination against COVID-19–associated hospitalization was 77% among immunocompromised adults (compared with 90% in immunocompetent adults).

“This is good vindication to keep vaccinating,” he said, “and perhaps speaks to how difficult it is to assess the vaccine response [through measurement of antibody only].”

Neither Duke University’s transplant program, which performed 100-120 lung transplants a year pre-COVID, nor the programs at UT Southwestern or the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville require that solid organ transplant candidates be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in order to receive transplants, as some other transplant programs have done. (When asked about the issue, Dr. Banga and Dr. Narula each said that they have had no or little trouble convincing patients awaiting lung transplants of the need for COVID-19 vaccination.)

In an August statement, the American Society of Transplantation recommended vaccination for all solid organ transplant recipients, preferably prior to transplantation, and said that it “support[s] the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination.”

The Society is not tracking centers’ vaccination policies. But Kaiser Health News reported in October that a growing number of transplant programs, such as UCHealth in Denver and UW Medicine in Seattle, have decided to either bar patients who refuse to be vaccinated from receiving transplants or give them lower priority on waitlists.

Potential lung donors, meanwhile, must be evaluated with lower respiratory COVID-19 testing, with results available prior to transplantation, according to policy developed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and effective in May 2021. The policy followed three published cases of donor-derived COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe, who wrote about use of COVID-positive donors in an editorial published in October.

In each case, the donor had a negative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab at the time of organ procurement but was later found to have the virus on bronchoalveolar lavage, he said.

(The use of other organs from COVID-positive donors is appearing thus far to be safe, Dr. Wolfe noted. In the editorial, he references 13 cases of solid organ transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors into noninfected recipients; none of the 13 transplant recipients developed COVID-19).

Some questions remain, such as how many lower respiratory tests should be run, and how donors should be evaluated in cases of discordant results. Dr. Banga shared the case of a donor with one positive lower respiratory test result followed by two negative results. After internal debate, and consideration of potential false positives and other issues, the team at UT Southwestern decided to decline the donor, Dr. Banga said.

Other programs are likely making similar, appropriately cautious decisions, said Dr. Wolfe. “There’s no way in real-time donor evaluation to know whether the positive test is active virus that could infect the recipient and replicate ... or whether it’s [picking up] inactive or dead fragments of virus that was there several weeks ago. Our tests don’t differentiate that.”

Transplants in COVID-19 patients

Decision-making about lung transplant candidacy among patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome is complex and in need of a new paradigm.

“Some of these patients have the potential to recover, and they’re going to recover way later than what we’re used to,” said Dr. Banga. “We can’t extrapolate for COVID ARDS what we’ve learned for any other virus-related ARDS.”

Dr. Narula also has recently seen at least one COVID-19 patient on ECMO and under evaluation for transplantation recover. “We do not want to transplant too early,” he said, noting that there is consensus that lung transplant should be pursued only when the damage is deemed irreversible clinically and radiologically in the best judgment of the team. Still, “for many of these patients the only exit route will be lung transplants. For the next 12-24 months, a significant proportion of our lung transplant patients will have had post-COVID–related lung damage.”

As of October 2021, 233 lung transplants had been performed in the United States in recipients whose primary diagnosis was reported as COVID related, said Anne Paschke, media relations specialist with the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Dr. Banga, Dr. Wolfe, and Dr. Narula reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

Data is sparse thus far, but there is concern in lung transplant medicine about the long-term risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and a potentially shortened longevity of transplanted lungs in recipients who become ill with COVID-19.

“My fear is that we’re potentially sitting on this iceberg worth of people who, come 6 months or a year from [the acute phase of] their COVID illness, will in fact have earlier and progressive, chronic rejection,” said Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of medicine in transplant infectious disease at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Lower respiratory viral infections have long been concerning for lung transplant recipients given their propensity to cause scarring, a decline in lung function, and a heightened risk of allograft rejection. Time will tell whether lung transplant recipients who survive COVID-19 follow a similar path, or one that is worse, he said.

Short-term data

Outcomes beyond hospitalization and acute illness for lung transplant recipients affected by COVID-19 have been reported in the literature by only a few lung transplant programs. These reports – as well as anecdotal experiences being informally shared among transplant programs – have raised the specter of more severe dysfunction following the acute phase and more early CLAD, said Tathagat Narula, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and a consultant in lung transplantation at the Mayo Clinic’s Jacksonville program.

“The available data cover only 3-6 months out. We don’t know what will happen in the next 6 months and beyond,” Dr. Narula said in an interview.

The risks of COVID-19 in already-transplanted patients and issues relating to the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination are just some of the challenges of lung transplant medicine in the era of SARS-CoV-2. “COVID-19,” said Dr. Narula, “has completely changed the way we practice lung transplant medicine – the way we’re looking both at our recipients and our donors.”

Potential donors are being evaluated with lower respiratory SARS-CoV-2 testing and an abundance of caution. And patients with severe COVID-19 affecting their own lungs are roundly expected to drive up lung transplant volume in the near future. “The whole paradigm has changed,” Dr. Narula said.

Post-acute trajectories

A chart review study published in October by the lung transplant team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, covered 44 consecutive survivors at a median follow-up of 4.5 months from hospital discharge or acute illness (the survival rate was 83.3%). Patients had significantly impaired functional status, and 18 of the 44 (40.9%) had a significant and persistent loss of forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (>10% from pre–COVID-19 baseline).

Three patients met the criteria for new CLAD after COVID-19 infection, with all three classified as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) phenotype.

Moreover, the majority of COVID-19 survivors who had CT chest scans (22 of 28) showed persistent parenchymal opacities – a finding that, regardless of symptomatology, suggests persistent allograft injury, said Amit Banga, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program in UT Southwestern’s lung transplant program.

“The implication is that there may be long-term consequences of COVID-19, perhaps related to some degree of ongoing inflammation and damage,” said Dr. Banga, a coauthor of the postinfection outcomes paper.

The UT Southwestern lung transplant program, which normally performs 60-80 transplants a year, began routine CT scanning 4-5 months into the pandemic, after “stumbling into a few patients who had no symptoms indicative of COVID pneumonia and no changes on an x-ray but significant involvement on a CT,” he said.

Without routine scanning in the general population of COVID-19 patients, Dr. Banga noted, “we’re limited in convincingly saying that COVID is uniquely doing this to lung transplant recipients.” Nor can they conclude that SARS-CoV-2 is unique from other respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in this regard. (The program has added CT scanning to its protocol for lung transplant recipients afflicted with other respiratory viruses to learn more.)

However, in the big picture, COVID-19 has proven to be far worse for lung transplant recipients than illness with other respiratory viruses, including RSV. “Patients have more frequent and greater loss of lung function, and worse debility from the acute illness,” Dr. Banga said.

“The cornerstones of treatment of both these viruses are very similar, but both the in-hospital course and the postdischarge outcomes are significantly different.”

In an initial paper published in September 2021, Dr. Banga and colleagues compared their first 25 lung transplant patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 with a historical cohort of 36 patients with RSV treated during 2016-2018.

Patients with COVID-19 had significantly worse morbidity and mortality, including worse postinfection lung function loss, functional decline, and 3-month survival.

More time, he said, will shed light on the risks of CLAD and the long-term potential for recovery of lung function. Currently, at UT Southwestern, it appears that patients who survive acute illness and the “first 3-6 months after COVID-19, when we’re seeing all the postinfection morbidity, may [enter] a period of stability,” Dr. Banga said.

Overall, he said, patients in their initial cohort are “holding steady” without unusual morbidity, readmissions, or “other setbacks to their allografts.”

At the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, which normally performs 40-50 lung transplants a year, transplant physicians have similarly observed significant declines in lung function beyond the acute phase of COVID-19. “Anecdotally, we’re seeing that some patients are beginning to recover some of their lung function, while others have not,” said Dr. Narula. “And we don’t have predictors as to who will progress to CLAD. It’s a big knowledge gap.”

Dr. Narula noted that patients with restrictive allograft syndrome, such as those reported by the UT Southwestern team, “have scarring of the lung and a much worse prognosis than the obstructive type of chronic rejection.” Whether there’s a role for antifibrotic therapy is a question worthy of research.

In UT Southwestern’s analysis, persistently lower absolute lymphocyte counts (< 600/dL) and higher ferritin levels (>150 ng/mL) at the time of hospital discharge were independently associated with significant lung function loss. This finding, reported in their October paper, has helped guide their management practices, Dr. Banga said.

“Persistently elevated ferritin may indicate ongoing inflammation at the allograft level,” he said. “We now send [such patients] home on a longer course of oral corticosteroids.”

At the front end of care for infected lung transplant recipients, Dr. Banga said that his team and physicians at other lung transplant programs are holding the cell-cycle inhibitor component of patients’ maintenance immunosuppression therapy (commonly mycophenolate or azathioprine) once infection is diagnosed to maximize chances of a better outcome.

“There may be variation on how long [the regimens are adjusted],” he said. “We changed our duration from 4 weeks to 2 due to patients developing a rebound worsening in the third and fourth week of acute illness.”

There is significant variation from institution to institution in how viral infections are managed in lung transplant recipients, he and Dr. Narula said. “Our numbers are so small in lung transplant, and we don’t have standardized protocols – it’s one of the biggest challenges in our field,” said Dr. Narula.

Vaccination issues, evaluation of donors

Whether or not immunosuppression regimens should be adjusted prior to vaccination is a controversial question, but is “an absolutely valid one” and is currently being studied in at least one National Institutes of Health–funded trial involving solid organ transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe.

“Some have jumped to the conclusion [based on some earlier data] that they should reduce immunosuppression regimens for everyone at the time of vaccination ... but I don’t know the answer yet,” he said. “Balancing staying rejection free with potentially gaining more immune response is complicated ... and it may depend on where the pandemic is going in your area and other factors.”

Reductions aside, Dr. Wolfe tells lung transplant recipients that, based on his approximation of a number of different studies in solid organ transplant recipients, approximately 40%-50% of patients who are immunized with two doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will develop meaningful antibody levels – and that this rises to 50%-60% after a third dose.

It is difficult to glean from available studies the level of vaccine response for lung transplant recipients specifically. But given that their level of maintenance immunosuppression is higher than for recipients of other donor organs, “as a broad sweep, lung transplant recipients tend to be lower in the pecking order of response,” he said.

Still, “there’s a lot to gain,” he said, pointing to a recent study from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2021 Nov 5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e3) showing that effectiveness of mRNA vaccination against COVID-19–associated hospitalization was 77% among immunocompromised adults (compared with 90% in immunocompetent adults).

“This is good vindication to keep vaccinating,” he said, “and perhaps speaks to how difficult it is to assess the vaccine response [through measurement of antibody only].”

Neither Duke University’s transplant program, which performed 100-120 lung transplants a year pre-COVID, nor the programs at UT Southwestern or the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville require that solid organ transplant candidates be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in order to receive transplants, as some other transplant programs have done. (When asked about the issue, Dr. Banga and Dr. Narula each said that they have had no or little trouble convincing patients awaiting lung transplants of the need for COVID-19 vaccination.)

In an August statement, the American Society of Transplantation recommended vaccination for all solid organ transplant recipients, preferably prior to transplantation, and said that it “support[s] the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination.”

The Society is not tracking centers’ vaccination policies. But Kaiser Health News reported in October that a growing number of transplant programs, such as UCHealth in Denver and UW Medicine in Seattle, have decided to either bar patients who refuse to be vaccinated from receiving transplants or give them lower priority on waitlists.

Potential lung donors, meanwhile, must be evaluated with lower respiratory COVID-19 testing, with results available prior to transplantation, according to policy developed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and effective in May 2021. The policy followed three published cases of donor-derived COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe, who wrote about use of COVID-positive donors in an editorial published in October.

In each case, the donor had a negative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab at the time of organ procurement but was later found to have the virus on bronchoalveolar lavage, he said.

(The use of other organs from COVID-positive donors is appearing thus far to be safe, Dr. Wolfe noted. In the editorial, he references 13 cases of solid organ transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors into noninfected recipients; none of the 13 transplant recipients developed COVID-19).

Some questions remain, such as how many lower respiratory tests should be run, and how donors should be evaluated in cases of discordant results. Dr. Banga shared the case of a donor with one positive lower respiratory test result followed by two negative results. After internal debate, and consideration of potential false positives and other issues, the team at UT Southwestern decided to decline the donor, Dr. Banga said.

Other programs are likely making similar, appropriately cautious decisions, said Dr. Wolfe. “There’s no way in real-time donor evaluation to know whether the positive test is active virus that could infect the recipient and replicate ... or whether it’s [picking up] inactive or dead fragments of virus that was there several weeks ago. Our tests don’t differentiate that.”

Transplants in COVID-19 patients

Decision-making about lung transplant candidacy among patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome is complex and in need of a new paradigm.

“Some of these patients have the potential to recover, and they’re going to recover way later than what we’re used to,” said Dr. Banga. “We can’t extrapolate for COVID ARDS what we’ve learned for any other virus-related ARDS.”

Dr. Narula also has recently seen at least one COVID-19 patient on ECMO and under evaluation for transplantation recover. “We do not want to transplant too early,” he said, noting that there is consensus that lung transplant should be pursued only when the damage is deemed irreversible clinically and radiologically in the best judgment of the team. Still, “for many of these patients the only exit route will be lung transplants. For the next 12-24 months, a significant proportion of our lung transplant patients will have had post-COVID–related lung damage.”

As of October 2021, 233 lung transplants had been performed in the United States in recipients whose primary diagnosis was reported as COVID related, said Anne Paschke, media relations specialist with the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Dr. Banga, Dr. Wolfe, and Dr. Narula reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

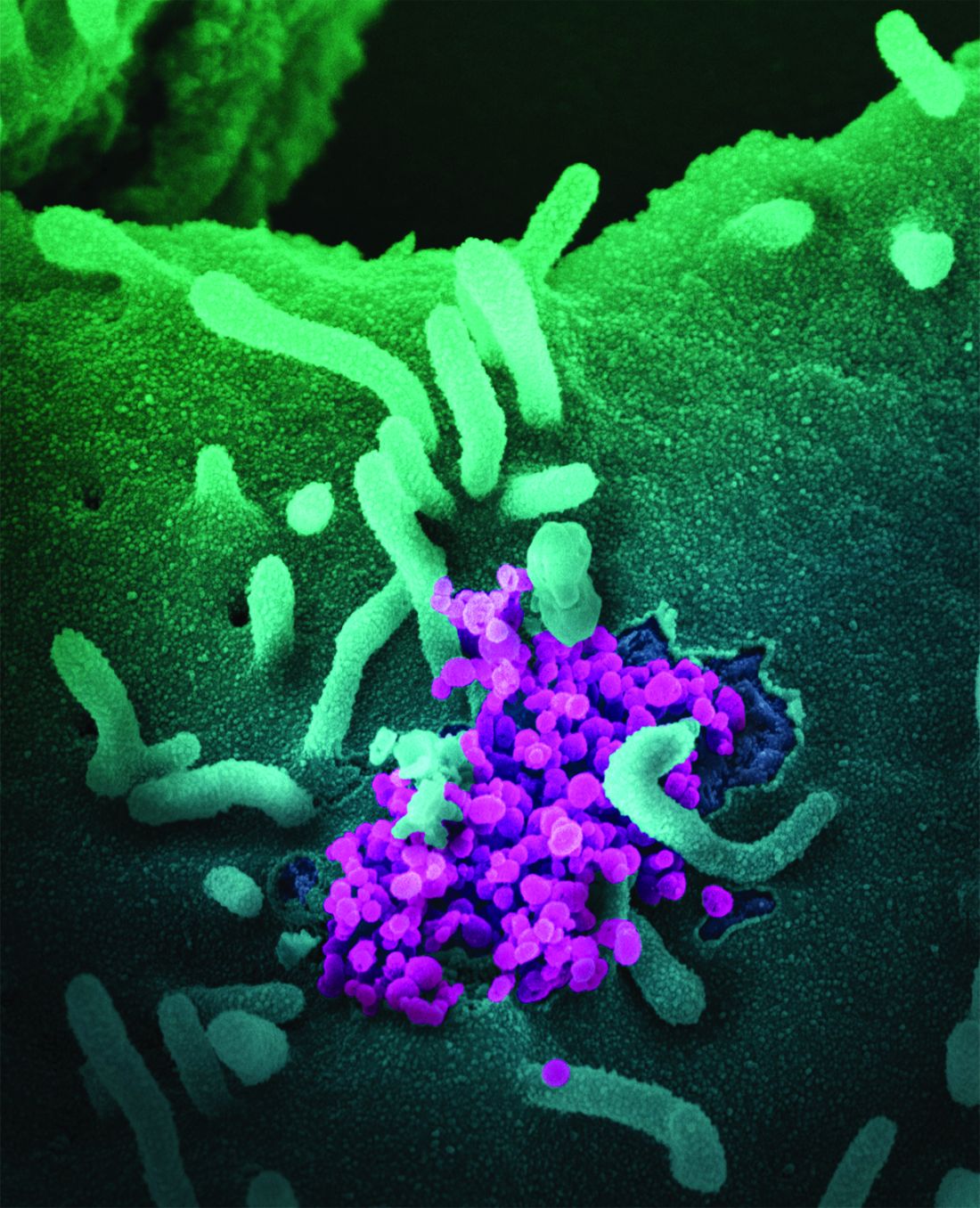

Coping with a shattered immune system: COVID and beyond

The co-opting and weakening of the immune system by hematologic malignancies and many of their treatments – and the blunting of the immune system’s response to vaccines – may be more salient during the COVID-19 pandemic than ever before.

Hematologic malignancies have been associated in large cancer-and-COVID-19 registries with more severe COVID-19 outcomes than solid tumors, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccines have yielded suboptimal responses across multiple studies. Clinicians and researchers have no shortage of questions, like what is the optimal timing of vaccines relative to cancer-directed therapy? What is the durability and impact of the immune response? What is the status of the immune system in patients who do not produce antispike antibodies after COVID-19 vaccination?

Moreover, will there be novel nonvaccine strategies – such as antibody cocktails or convalescent plasma – to ensure protection against COVID-19 and other future viral threats? And what really defines immunocompromise today and moving forward?

“We don’t know what we don’t know,” said Jeremy L. Warner, MD, associate professor of medicine (hematology/oncology) and biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and cofounder of the international COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. “The immune system is incredibly complex and there are numerous defenses, in addition to the humoral response that we routinely measure.”

Another of the pressing pandemic-time questions for infectious disease specialists working in cancer centers concerns a different infectious threat: measles. “There is a lot of concern in this space about the reported drop in childhood vaccinations and the possibility of measles outbreaks as a follow-up to COVID-19,” said Steven A. Pergam, MD, MPH, associate professor in the vaccine and infectious disease division and the clinical research division of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Whether recipients of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and cellular therapy should be revaccinated earlier than 2 years post treatment is a question worthy of preemptive discussion, he said.

What about timing?

“A silver lining of the pandemic is that it’s improving our understanding of response to vaccinations and outcomes with respiratory viruses in patients with hematologic malignancies,” said Samuel Rubinstein, MD, of the division of hematology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We’re going to learn a lot more about how to ensure that our patients are optimally protected from respiratory viruses.”

Dr. Rubinstein focuses on plasma cell disorders, mostly multiple myeloma, and routinely explains to patients consenting to use daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, or a BCMA-directed therapy, that these therapies “in particular probably do impair vaccine immune response.”

He has handled the timing of the COVID-19 vaccines – currently boosters, in most cases – as he has with influenza and other immunizations such as the pneumococcal vaccine, administering the vaccines agnostic to therapy unless the patient is about to start daratumumab or a BCMA-directed therapy. In this case, he considers vaccinating and waiting 2 weeks (for an immune response to occur) before starting therapy.

However, “if I have any concern that a delay will result in suboptimal cancer control, then I don’t wait,” Dr. Rubinstein said. Poor control of a primary malignancy has been consistently associated with worse COVID-19–specific outcomes in cancer–COVID-19 studies, he said, including an analysis of almost 5,000 patients recorded to the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium .1

(The analysis also documented that patients with a hematologic malignancy had an odds ratio of higher COVID-19 severity of 1.7, compared with patients with a solid tumor, and an odds ratio of 30-day mortality of 1.44.)

Ideally, said Dr. Warner, patients will get vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccines or others, “before starting on any cytotoxic chemotherapy and when they do not have low blood counts or perhaps autoimmune complications of immunotherapy.” However, “perfect being the enemy of good, it’s better to get vaccinated than to wait for the exact ideal time.”

Peter Paul Yu, MD, physician-in-chief at Hartford (Conn.) Healthcare Cancer Institute, said that for most patients, there’s no evidence to support an optimal timing of vaccine administration during the chemotherapy cycle. “We looked into that [to guide administration of the COVID-19 vaccines], thinking there might be some data about influenza vaccination,” he said. “But there isn’t much. … And if we make things more complicated than the evidence suggests, we may have fewer people getting vaccinations.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network offered several timing recommendations in its August 2021 COVID-19 vaccination guidance – mainly that patients receiving intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy (such as those on cytarabine/anthracycline-based induction regimens for acute myeloid leukemia) delay COVID-19 vaccination until absolute neutrophil count recovery, and that patients on long-term maintenance therapy (for instance, targeted agents for chronic lymphocytic leukemia or myeloproliferative neoplasms) be vaccinated as soon as possible.

Vaccination should be delayed for at least 3 months, the NCCN noted, following HCT or engineered cell therapy (for example, chimeric antigen receptor [CAR] T cells) “in order to maximize vaccine efficacy.”

More known unknowns

The tempered efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines in patients with hematologic malignancies “has been shown in multiple studies of multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and other malignancies, and we know it’s true in transplant,” said Dr. Pergam.

In a study of 67 patients with hematologic malignancies at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, for instance, 46.3% did not generate IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor–binding domain after completing their two-dose mRNA vaccine series. Patients with B-cell CLL were especially unlikely to develop antibodies.2A much larger study of more than 1,400 patients from investigators at the Mayo Clinics in Rochester, Minn., and Jacksonville, Fla., found that approximately 25% of all patients with hematologic malignancies did not produce antispike IgG antibodies, and that those with the most common B-cell malignancies had the lowest rate of seropositivity (44%-79%).3There’s a clear but challenging delineation between antibody testing in the research space and in clinical practice, however. Various national and cancer societies recommended earlier this year against routine postvaccine serological monitoring outside of clinical trials, and the sources interviewed for this story all emphasized that antibody titer measurements should not guide decisions about boosters or about the precautions advised for patients.

Titers checked at a single point in time do not capture the kinetics, multidimensional nature, or durability of an immune response, Dr. Warner said. “There are papers out there that say zero patients with CCL seroconverted … but they do still have some immunity, and maybe even a lot of immunity.”

Antibody testing can create a false sense of security, or a false sense of dread, he said. Yet in practice, the use of serological monitoring “has been all over the place [with] no consistency … and decisions probably being made at the individual clinic level or health system level,” he said.

To a lesser degree, so have definitions of what composes significant immunocompromise in the context of COVID-19 vaccine eligibility. “The question comes up, what does immunocompromised really mean?” said Dr. Yu, whose institution is a member of the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Alliance.

As of September, the MSK Cancer Center had taken a more granular approach to describing moderate to severe immunocompromise than did the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC said this level of immunocompromise includes people receiving active cancer treatment for tumors or cancers of the blood, and those who’ve received a stem cell transplant within the past 2 years. MSK extended the recommendation, as it concerns hematologic malignancies, to patients who are within 12 months after treatment with B-cell depleting drugs, patients who have been treated for blood cancers within the last 6 months, and patients who received CAR T therapy within the past 2 years.

Dr. Yu, who was not involved in creating the MSK recommendations for third COVID-19 vaccines, said that he has been thinking more broadly during the pandemic about the notion of immunocompetence. “It’s my opinion that patients with hematologic malignancies, even if they’re not on treatment, are not fully immune competent,” he said. This includes patients with CLL stage 0 and patients with plasma cell dyscrasias who don’t yet meet the criteria for multiple myeloma but have a monoclonal gammopathy, and those with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, he said.

“We’re seeing [variable] recommendations based on expert opinion, and I think that’s justifiable in such a dynamic situation,” Dr. Yu said. “I would [even] argue it’s desirable so we can learn from different approaches” and collect more rigorous observational data.

Immunocompetence needs to be “viewed in the context of the threat,” he added. “COVID changes the equation. … What’s immunocompromised in my mind has changed [from prepandemic times].”

Preparing for measles

Measles lit up on Dr. Pergam’s radar screen in 2019, when an outbreak occurred in nearby Clark County, Wash. This and other outbreaks in New York, California, and other states highlighted declines in measles herd immunity in the United States and prompted him to investigate the seroprevalence of measles antibodies in the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center’s outpatient population.

Of 959 consecutive patients seen at the center, they found, 25% lacked protective antibodies for measles. For patients with hematologic malignancies and those with a history of HCT, seroprevalence was worse: 37% and 54%, respectively, were without the IgG antibodies.4 Measles “is the most contagious human virus we have at the moment,” he said, and “revaccinating people is hard when it comes to cancer because it is a live virus vaccine.”

Vaccine hesitancy, a rise in nonmedical exemptions, and other factors were threatening herd immunity before the pandemic began. Now, with declines in routine childhood medical visits and other vaccination opportunities and resources here and in other countries – and declining immunization rates documented by the CDC in May 2021 – the pandemic has made measles outbreaks more likely, he said. (Measles outbreaks in West Africa on the tail end of the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2015 caused more deaths in children than Ebola, he noted.)

The first priority is vaccination “cocooning,” a strategy that has long been important for patients with hematologic malignancies. But it also possible, Dr. Pergam said, that in the setting of any future community transmission, revaccination for HCT recipients could occur earlier than the standard 2-year post-transplantation recommendation.

In a 2019 position statement endorsed by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Dr. Pergam and other infectious disease physicians and oncologists provide criteria for considering early revaccination on a case-by-case basis for patients on minimal immunosuppressive therapy who are at least 1-year post transplantation.5

“Our thinking was that there may be lower-risk patients to whom we could offer the vaccine” – patients for whom the risk of developing measles might outweigh the risk of potential vaccine-related complications, he said.

And if there were community cases, he added, there might be a place for testing antibody levels in post-transplant patients, however imperfect the window to immunity may be. “We’re thinking through potential scenarios,” he said. “Oncologists should think about measles again and have it on their back burner.”

References

1. Grivas P et al. Ann Oncol. 2021 Jun;32(6):787-800.

2. Agha ME et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021 July;8(7):ofab353.

3. Greenberger LM et al. Cancer Cell. 2021 Aug 9;39(8):1031-3.

4. Marquis SR et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 July;4(7):e2118508.

5. Pergam SA et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019 Nov;25:e321-30.

The co-opting and weakening of the immune system by hematologic malignancies and many of their treatments – and the blunting of the immune system’s response to vaccines – may be more salient during the COVID-19 pandemic than ever before.

Hematologic malignancies have been associated in large cancer-and-COVID-19 registries with more severe COVID-19 outcomes than solid tumors, and COVID-19 mRNA vaccines have yielded suboptimal responses across multiple studies. Clinicians and researchers have no shortage of questions, like what is the optimal timing of vaccines relative to cancer-directed therapy? What is the durability and impact of the immune response? What is the status of the immune system in patients who do not produce antispike antibodies after COVID-19 vaccination?

Moreover, will there be novel nonvaccine strategies – such as antibody cocktails or convalescent plasma – to ensure protection against COVID-19 and other future viral threats? And what really defines immunocompromise today and moving forward?

“We don’t know what we don’t know,” said Jeremy L. Warner, MD, associate professor of medicine (hematology/oncology) and biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and cofounder of the international COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. “The immune system is incredibly complex and there are numerous defenses, in addition to the humoral response that we routinely measure.”

Another of the pressing pandemic-time questions for infectious disease specialists working in cancer centers concerns a different infectious threat: measles. “There is a lot of concern in this space about the reported drop in childhood vaccinations and the possibility of measles outbreaks as a follow-up to COVID-19,” said Steven A. Pergam, MD, MPH, associate professor in the vaccine and infectious disease division and the clinical research division of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Whether recipients of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and cellular therapy should be revaccinated earlier than 2 years post treatment is a question worthy of preemptive discussion, he said.

What about timing?

“A silver lining of the pandemic is that it’s improving our understanding of response to vaccinations and outcomes with respiratory viruses in patients with hematologic malignancies,” said Samuel Rubinstein, MD, of the division of hematology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We’re going to learn a lot more about how to ensure that our patients are optimally protected from respiratory viruses.”

Dr. Rubinstein focuses on plasma cell disorders, mostly multiple myeloma, and routinely explains to patients consenting to use daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, or a BCMA-directed therapy, that these therapies “in particular probably do impair vaccine immune response.”

He has handled the timing of the COVID-19 vaccines – currently boosters, in most cases – as he has with influenza and other immunizations such as the pneumococcal vaccine, administering the vaccines agnostic to therapy unless the patient is about to start daratumumab or a BCMA-directed therapy. In this case, he considers vaccinating and waiting 2 weeks (for an immune response to occur) before starting therapy.

However, “if I have any concern that a delay will result in suboptimal cancer control, then I don’t wait,” Dr. Rubinstein said. Poor control of a primary malignancy has been consistently associated with worse COVID-19–specific outcomes in cancer–COVID-19 studies, he said, including an analysis of almost 5,000 patients recorded to the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium .1

(The analysis also documented that patients with a hematologic malignancy had an odds ratio of higher COVID-19 severity of 1.7, compared with patients with a solid tumor, and an odds ratio of 30-day mortality of 1.44.)

Ideally, said Dr. Warner, patients will get vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccines or others, “before starting on any cytotoxic chemotherapy and when they do not have low blood counts or perhaps autoimmune complications of immunotherapy.” However, “perfect being the enemy of good, it’s better to get vaccinated than to wait for the exact ideal time.”

Peter Paul Yu, MD, physician-in-chief at Hartford (Conn.) Healthcare Cancer Institute, said that for most patients, there’s no evidence to support an optimal timing of vaccine administration during the chemotherapy cycle. “We looked into that [to guide administration of the COVID-19 vaccines], thinking there might be some data about influenza vaccination,” he said. “But there isn’t much. … And if we make things more complicated than the evidence suggests, we may have fewer people getting vaccinations.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network offered several timing recommendations in its August 2021 COVID-19 vaccination guidance – mainly that patients receiving intensive cytotoxic chemotherapy (such as those on cytarabine/anthracycline-based induction regimens for acute myeloid leukemia) delay COVID-19 vaccination until absolute neutrophil count recovery, and that patients on long-term maintenance therapy (for instance, targeted agents for chronic lymphocytic leukemia or myeloproliferative neoplasms) be vaccinated as soon as possible.

Vaccination should be delayed for at least 3 months, the NCCN noted, following HCT or engineered cell therapy (for example, chimeric antigen receptor [CAR] T cells) “in order to maximize vaccine efficacy.”

More known unknowns

The tempered efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines in patients with hematologic malignancies “has been shown in multiple studies of multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and other malignancies, and we know it’s true in transplant,” said Dr. Pergam.

In a study of 67 patients with hematologic malignancies at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, for instance, 46.3% did not generate IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor–binding domain after completing their two-dose mRNA vaccine series. Patients with B-cell CLL were especially unlikely to develop antibodies.2A much larger study of more than 1,400 patients from investigators at the Mayo Clinics in Rochester, Minn., and Jacksonville, Fla., found that approximately 25% of all patients with hematologic malignancies did not produce antispike IgG antibodies, and that those with the most common B-cell malignancies had the lowest rate of seropositivity (44%-79%).3There’s a clear but challenging delineation between antibody testing in the research space and in clinical practice, however. Various national and cancer societies recommended earlier this year against routine postvaccine serological monitoring outside of clinical trials, and the sources interviewed for this story all emphasized that antibody titer measurements should not guide decisions about boosters or about the precautions advised for patients.

Titers checked at a single point in time do not capture the kinetics, multidimensional nature, or durability of an immune response, Dr. Warner said. “There are papers out there that say zero patients with CCL seroconverted … but they do still have some immunity, and maybe even a lot of immunity.”

Antibody testing can create a false sense of security, or a false sense of dread, he said. Yet in practice, the use of serological monitoring “has been all over the place [with] no consistency … and decisions probably being made at the individual clinic level or health system level,” he said.

To a lesser degree, so have definitions of what composes significant immunocompromise in the context of COVID-19 vaccine eligibility. “The question comes up, what does immunocompromised really mean?” said Dr. Yu, whose institution is a member of the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Alliance.

As of September, the MSK Cancer Center had taken a more granular approach to describing moderate to severe immunocompromise than did the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC said this level of immunocompromise includes people receiving active cancer treatment for tumors or cancers of the blood, and those who’ve received a stem cell transplant within the past 2 years. MSK extended the recommendation, as it concerns hematologic malignancies, to patients who are within 12 months after treatment with B-cell depleting drugs, patients who have been treated for blood cancers within the last 6 months, and patients who received CAR T therapy within the past 2 years.

Dr. Yu, who was not involved in creating the MSK recommendations for third COVID-19 vaccines, said that he has been thinking more broadly during the pandemic about the notion of immunocompetence. “It’s my opinion that patients with hematologic malignancies, even if they’re not on treatment, are not fully immune competent,” he said. This includes patients with CLL stage 0 and patients with plasma cell dyscrasias who don’t yet meet the criteria for multiple myeloma but have a monoclonal gammopathy, and those with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, he said.

“We’re seeing [variable] recommendations based on expert opinion, and I think that’s justifiable in such a dynamic situation,” Dr. Yu said. “I would [even] argue it’s desirable so we can learn from different approaches” and collect more rigorous observational data.

Immunocompetence needs to be “viewed in the context of the threat,” he added. “COVID changes the equation. … What’s immunocompromised in my mind has changed [from prepandemic times].”

Preparing for measles