User login

Fever, dyspnea, and a new heart murmur

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department because of night sweats, fever, chills, and shortness of breath. He also had an acute onset of blue discoloration of his right fourth finger. His symptoms (except for the finger discoloration) had begun about 6 months previously and had rapidly progressed despite several courses of different antibiotics of different types, given both intravenously in the hospital and orally at home. He had lost 20 lb during this time. Previously, he had been healthy.

About 1 month after his symptoms began, he had consulted his primary care physician, who detected a new grade 4/6 systolic and diastolic murmur. Transthoracic echocardiography about 2 months after that demonstrated mild aortic and mitral insufficiency but no echocardiographic features supporting infective endocarditis. Of note, the patient had no risk factors for endocarditis such as illicit drug use or poor dental health.

In the emergency department, his temperature was 99.4°F (37.4°C), pulse 109 beats per minute, and blood pressure 126/60 mm Hg. He had a grade 3/6 harsh holosystolic murmur best heard at the right upper sternal border, a grade 3/4 holodiastolic murmur audible across the precordium, and a grade 3/4 holosystolic blowing murmur best heard at the cardiac apex. Other findings included signs of aortic insufficiency—the Duroziez sign (a diastolic murmur heard over the femoral artery when compressed), Watson’s water-hammer pulse (indicating a wide pulse pressure), and the Müller sign (pulsation of the uvula)—and small Janeway lesions on the inner aspect of his right arm and palm.

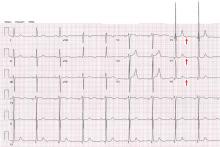

Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm, PR interval 128 ms, QRS complex 100 ms, QT interval 360 ms, and corrected QT interval 473 ms.

Blood cultures grew Streptococcus sanguinis. Both transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography were done promptly and revealed multiple mobile echodensities attached to a trileaflet aortic valve, consistent with vegetations and valve leaflet destruction; severe (4+) aortic regurgitation with flow reversal in the abdominal aorta; mild mitral regurgitation; and a mitral valve aneurysm with mild mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS: WORTH CONSIDERING

S sanguinis is a member of the group of viridans streptococci. As a normal inhabitant of the healthy human mouth, it is found in dental plaque. It may enter the bloodstream during dental cleaning and may colonize the heart valves, particularly the mitral and aortic valves, where it is the most common cause of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Infective endocarditis is often diagnosed clinically with the Duke criteria (www.med-calc.com/endocarditis.html).1 However, the variability of the clinical presentation and the nonspecific nature of the initial workup often create a diagnostic challenge for the evaluating physician.1,2

In cases of recurrent persistent fever and a new heart murmur, infective endocarditis must always be considered. Blood cultures should be ordered early and repeatedly. If blood cultures are positive, transesophageal echocardiography should be done without delay if transthoracic echocardiography was unremarkable. Prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention prevent complications.

MITRAL VALVE ANEURYSM IN AORTIC VALVE ENDOCARDITIS

Aortic valve endocarditis often also involves the mitral valve; mitral valve endocarditis is seen in 17% of patients undergoing surgery for aortic valve endocarditis.3 Proposed mechanisms for this association include jet lesions from aortic regurgitation, vegetation prolapse with direct contact between the aortic valve and anterior mitral leaflet (“kissing lesions”), and direct local spread of infection.4–7

One of every five patients with mitral valve involvement in aortic valve endocarditis has a mitral valve aneurysm.3 This is a serious finding, as it can lead to septic embolization. Also, the weakened lining of the mitral valve aneurysm can rupture, resulting in severe mitral regurgitation, acute pulmonary edema, and precipitous cardiopulmonary decompensation.5

Transesophageal echocardiography is more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiography for detecting mitral valve aneurysm.8 On two-dimensional echocardiography, the lesion appears as a narrow-necked, saccular echolucency with systolic protrusion into the left atrium. Color Doppler imaging often shows turbulent, high-velocity flow.

Differential diagnosis of mitral valve aneurysm

Differential diagnostic considerations include a valvular blood cyst, a congenital cardiac diverticulum, and mitral valve prolapse.

Valvular blood cysts are extremely rare in adults.9 These benign, congenital tumors are most often found on the atrioventricular valves in infants, in whom the reported incidence is between 25% and 100%. In almost all cases, these cysts are believed to regress spontaneously with time.

In almost all reported cases, the cyst involved the valvular apparatus or papillary muscle of the tricuspid, pulmonary, or mitral valve.10 Cysts consist of a benign diverticulum lined with flattened, cobblestone-shaped endothelium and are filled with blood. They can cause heart murmurs in otherwise asymptomatic patients.

On echocardiography, a blood cyst appears as an oval mass (often at the interatrial septum), often with normal cardiac function. In the rare case in which a blood cyst is found incidentally during echocardiography, the hemodynamic impact, if any, should be determined by Doppler techniques.

When benign, a valvular blood cyst can be safely monitored with echocardiographic follow-up.11 Treatment involves surgical resection of the mass in symptomatic patients in whom cardiac function is impaired by the presence of the cyst.

Congenital cardiac diverticuli are extremely rare, most often seen in children, and associated with a midline thoracoabdominal defect. Echocardiography can differentiate a ventricular diverticulum from an aneurysm or a pseudoaneurysm.

A ventricular diverticulum has a fibrous, narrow neck connecting with the ventricle, and a small circular echo-free space that communicates with the ventricle via this narrow neck.2 Doppler imaging shows systolic flow from the diverticulum to the ventricle, and systolic contractility may also be seen during cardiac catheterization. Congenital diverticulum is typically confused with ventricular aneurysm and, to a lesser degree, with mitral valve aneurysm.

Mitral valve prolapse is characterized by interchordal ballooning or hooding of the mitral valve leaflets that occurs when one or both floppy, enlarged leaflets prolapse into the left atrium during systole.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

The patient underwent open heart surgery, with successful repair of the aortic root, replacement of the aortic valve, and repair of the mitral valve. An abscess was found within the aneurysmal cavity.

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med 1994; 96:200–209.

- Prendergast BD. Diagnostic criteria and problems in infective endocarditis. Heart 2004; 90:611–613.

- Gonzalez-Lavin L, Lise M, Ross D. The importance of the ‘jet lesion’ in bacterial endocarditis involving the left heart. Surgical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970; 59:185–192.

- Silbiger JJ. Review: mitral valve aneurysms in infective endocarditis: mechanisms, clinical recognition, and treatment. J Heart Valve Dis 2009; 18:476–480.

- Reid CL, Chandraratna AN, Harrison E, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm: clinical features, echocardiographic-pathologic correlations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 2:460–464.

- Rodbard S. Blood velocity and endocarditis. Circulation 1963; 27:18–28.

- Piper C, Hetzer R, Körfer R, Bergemann R, Horstkotte D. The importance of secondary mitral valve involvement in primary aortic valve endocarditis; the mitral kissing vegetation. Eur Heart J 2002; 23:79–86.

- Cziner DG, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, Keller AM, Daniel WG, Kronzon I. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing mitral valve perforation. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69:1495–1497.

- Roberts PF, Serra AJ, McNicholas KW, Shapira N, Lemole GM. Atrial blood cyst: a rare finding. Ann Thorac Surg 1996; 62:880–882.

- Grimaldi A, Capritti E, Pappalardo F, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: blood cyst of the mitral valve. J Cardiovasc Med 2012; 3:46.

- Boyd WC, Rosengart TK, Hartman GS. Isolated left ventricular diverticulum in an adult. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1999; 13:468–470.

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department because of night sweats, fever, chills, and shortness of breath. He also had an acute onset of blue discoloration of his right fourth finger. His symptoms (except for the finger discoloration) had begun about 6 months previously and had rapidly progressed despite several courses of different antibiotics of different types, given both intravenously in the hospital and orally at home. He had lost 20 lb during this time. Previously, he had been healthy.

About 1 month after his symptoms began, he had consulted his primary care physician, who detected a new grade 4/6 systolic and diastolic murmur. Transthoracic echocardiography about 2 months after that demonstrated mild aortic and mitral insufficiency but no echocardiographic features supporting infective endocarditis. Of note, the patient had no risk factors for endocarditis such as illicit drug use or poor dental health.

In the emergency department, his temperature was 99.4°F (37.4°C), pulse 109 beats per minute, and blood pressure 126/60 mm Hg. He had a grade 3/6 harsh holosystolic murmur best heard at the right upper sternal border, a grade 3/4 holodiastolic murmur audible across the precordium, and a grade 3/4 holosystolic blowing murmur best heard at the cardiac apex. Other findings included signs of aortic insufficiency—the Duroziez sign (a diastolic murmur heard over the femoral artery when compressed), Watson’s water-hammer pulse (indicating a wide pulse pressure), and the Müller sign (pulsation of the uvula)—and small Janeway lesions on the inner aspect of his right arm and palm.

Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm, PR interval 128 ms, QRS complex 100 ms, QT interval 360 ms, and corrected QT interval 473 ms.

Blood cultures grew Streptococcus sanguinis. Both transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography were done promptly and revealed multiple mobile echodensities attached to a trileaflet aortic valve, consistent with vegetations and valve leaflet destruction; severe (4+) aortic regurgitation with flow reversal in the abdominal aorta; mild mitral regurgitation; and a mitral valve aneurysm with mild mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS: WORTH CONSIDERING

S sanguinis is a member of the group of viridans streptococci. As a normal inhabitant of the healthy human mouth, it is found in dental plaque. It may enter the bloodstream during dental cleaning and may colonize the heart valves, particularly the mitral and aortic valves, where it is the most common cause of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Infective endocarditis is often diagnosed clinically with the Duke criteria (www.med-calc.com/endocarditis.html).1 However, the variability of the clinical presentation and the nonspecific nature of the initial workup often create a diagnostic challenge for the evaluating physician.1,2

In cases of recurrent persistent fever and a new heart murmur, infective endocarditis must always be considered. Blood cultures should be ordered early and repeatedly. If blood cultures are positive, transesophageal echocardiography should be done without delay if transthoracic echocardiography was unremarkable. Prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention prevent complications.

MITRAL VALVE ANEURYSM IN AORTIC VALVE ENDOCARDITIS

Aortic valve endocarditis often also involves the mitral valve; mitral valve endocarditis is seen in 17% of patients undergoing surgery for aortic valve endocarditis.3 Proposed mechanisms for this association include jet lesions from aortic regurgitation, vegetation prolapse with direct contact between the aortic valve and anterior mitral leaflet (“kissing lesions”), and direct local spread of infection.4–7

One of every five patients with mitral valve involvement in aortic valve endocarditis has a mitral valve aneurysm.3 This is a serious finding, as it can lead to septic embolization. Also, the weakened lining of the mitral valve aneurysm can rupture, resulting in severe mitral regurgitation, acute pulmonary edema, and precipitous cardiopulmonary decompensation.5

Transesophageal echocardiography is more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiography for detecting mitral valve aneurysm.8 On two-dimensional echocardiography, the lesion appears as a narrow-necked, saccular echolucency with systolic protrusion into the left atrium. Color Doppler imaging often shows turbulent, high-velocity flow.

Differential diagnosis of mitral valve aneurysm

Differential diagnostic considerations include a valvular blood cyst, a congenital cardiac diverticulum, and mitral valve prolapse.

Valvular blood cysts are extremely rare in adults.9 These benign, congenital tumors are most often found on the atrioventricular valves in infants, in whom the reported incidence is between 25% and 100%. In almost all cases, these cysts are believed to regress spontaneously with time.

In almost all reported cases, the cyst involved the valvular apparatus or papillary muscle of the tricuspid, pulmonary, or mitral valve.10 Cysts consist of a benign diverticulum lined with flattened, cobblestone-shaped endothelium and are filled with blood. They can cause heart murmurs in otherwise asymptomatic patients.

On echocardiography, a blood cyst appears as an oval mass (often at the interatrial septum), often with normal cardiac function. In the rare case in which a blood cyst is found incidentally during echocardiography, the hemodynamic impact, if any, should be determined by Doppler techniques.

When benign, a valvular blood cyst can be safely monitored with echocardiographic follow-up.11 Treatment involves surgical resection of the mass in symptomatic patients in whom cardiac function is impaired by the presence of the cyst.

Congenital cardiac diverticuli are extremely rare, most often seen in children, and associated with a midline thoracoabdominal defect. Echocardiography can differentiate a ventricular diverticulum from an aneurysm or a pseudoaneurysm.

A ventricular diverticulum has a fibrous, narrow neck connecting with the ventricle, and a small circular echo-free space that communicates with the ventricle via this narrow neck.2 Doppler imaging shows systolic flow from the diverticulum to the ventricle, and systolic contractility may also be seen during cardiac catheterization. Congenital diverticulum is typically confused with ventricular aneurysm and, to a lesser degree, with mitral valve aneurysm.

Mitral valve prolapse is characterized by interchordal ballooning or hooding of the mitral valve leaflets that occurs when one or both floppy, enlarged leaflets prolapse into the left atrium during systole.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

The patient underwent open heart surgery, with successful repair of the aortic root, replacement of the aortic valve, and repair of the mitral valve. An abscess was found within the aneurysmal cavity.

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department because of night sweats, fever, chills, and shortness of breath. He also had an acute onset of blue discoloration of his right fourth finger. His symptoms (except for the finger discoloration) had begun about 6 months previously and had rapidly progressed despite several courses of different antibiotics of different types, given both intravenously in the hospital and orally at home. He had lost 20 lb during this time. Previously, he had been healthy.

About 1 month after his symptoms began, he had consulted his primary care physician, who detected a new grade 4/6 systolic and diastolic murmur. Transthoracic echocardiography about 2 months after that demonstrated mild aortic and mitral insufficiency but no echocardiographic features supporting infective endocarditis. Of note, the patient had no risk factors for endocarditis such as illicit drug use or poor dental health.

In the emergency department, his temperature was 99.4°F (37.4°C), pulse 109 beats per minute, and blood pressure 126/60 mm Hg. He had a grade 3/6 harsh holosystolic murmur best heard at the right upper sternal border, a grade 3/4 holodiastolic murmur audible across the precordium, and a grade 3/4 holosystolic blowing murmur best heard at the cardiac apex. Other findings included signs of aortic insufficiency—the Duroziez sign (a diastolic murmur heard over the femoral artery when compressed), Watson’s water-hammer pulse (indicating a wide pulse pressure), and the Müller sign (pulsation of the uvula)—and small Janeway lesions on the inner aspect of his right arm and palm.

Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm, PR interval 128 ms, QRS complex 100 ms, QT interval 360 ms, and corrected QT interval 473 ms.

Blood cultures grew Streptococcus sanguinis. Both transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography were done promptly and revealed multiple mobile echodensities attached to a trileaflet aortic valve, consistent with vegetations and valve leaflet destruction; severe (4+) aortic regurgitation with flow reversal in the abdominal aorta; mild mitral regurgitation; and a mitral valve aneurysm with mild mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS: WORTH CONSIDERING

S sanguinis is a member of the group of viridans streptococci. As a normal inhabitant of the healthy human mouth, it is found in dental plaque. It may enter the bloodstream during dental cleaning and may colonize the heart valves, particularly the mitral and aortic valves, where it is the most common cause of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Infective endocarditis is often diagnosed clinically with the Duke criteria (www.med-calc.com/endocarditis.html).1 However, the variability of the clinical presentation and the nonspecific nature of the initial workup often create a diagnostic challenge for the evaluating physician.1,2

In cases of recurrent persistent fever and a new heart murmur, infective endocarditis must always be considered. Blood cultures should be ordered early and repeatedly. If blood cultures are positive, transesophageal echocardiography should be done without delay if transthoracic echocardiography was unremarkable. Prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention prevent complications.

MITRAL VALVE ANEURYSM IN AORTIC VALVE ENDOCARDITIS

Aortic valve endocarditis often also involves the mitral valve; mitral valve endocarditis is seen in 17% of patients undergoing surgery for aortic valve endocarditis.3 Proposed mechanisms for this association include jet lesions from aortic regurgitation, vegetation prolapse with direct contact between the aortic valve and anterior mitral leaflet (“kissing lesions”), and direct local spread of infection.4–7

One of every five patients with mitral valve involvement in aortic valve endocarditis has a mitral valve aneurysm.3 This is a serious finding, as it can lead to septic embolization. Also, the weakened lining of the mitral valve aneurysm can rupture, resulting in severe mitral regurgitation, acute pulmonary edema, and precipitous cardiopulmonary decompensation.5

Transesophageal echocardiography is more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiography for detecting mitral valve aneurysm.8 On two-dimensional echocardiography, the lesion appears as a narrow-necked, saccular echolucency with systolic protrusion into the left atrium. Color Doppler imaging often shows turbulent, high-velocity flow.

Differential diagnosis of mitral valve aneurysm

Differential diagnostic considerations include a valvular blood cyst, a congenital cardiac diverticulum, and mitral valve prolapse.

Valvular blood cysts are extremely rare in adults.9 These benign, congenital tumors are most often found on the atrioventricular valves in infants, in whom the reported incidence is between 25% and 100%. In almost all cases, these cysts are believed to regress spontaneously with time.

In almost all reported cases, the cyst involved the valvular apparatus or papillary muscle of the tricuspid, pulmonary, or mitral valve.10 Cysts consist of a benign diverticulum lined with flattened, cobblestone-shaped endothelium and are filled with blood. They can cause heart murmurs in otherwise asymptomatic patients.

On echocardiography, a blood cyst appears as an oval mass (often at the interatrial septum), often with normal cardiac function. In the rare case in which a blood cyst is found incidentally during echocardiography, the hemodynamic impact, if any, should be determined by Doppler techniques.

When benign, a valvular blood cyst can be safely monitored with echocardiographic follow-up.11 Treatment involves surgical resection of the mass in symptomatic patients in whom cardiac function is impaired by the presence of the cyst.

Congenital cardiac diverticuli are extremely rare, most often seen in children, and associated with a midline thoracoabdominal defect. Echocardiography can differentiate a ventricular diverticulum from an aneurysm or a pseudoaneurysm.

A ventricular diverticulum has a fibrous, narrow neck connecting with the ventricle, and a small circular echo-free space that communicates with the ventricle via this narrow neck.2 Doppler imaging shows systolic flow from the diverticulum to the ventricle, and systolic contractility may also be seen during cardiac catheterization. Congenital diverticulum is typically confused with ventricular aneurysm and, to a lesser degree, with mitral valve aneurysm.

Mitral valve prolapse is characterized by interchordal ballooning or hooding of the mitral valve leaflets that occurs when one or both floppy, enlarged leaflets prolapse into the left atrium during systole.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

The patient underwent open heart surgery, with successful repair of the aortic root, replacement of the aortic valve, and repair of the mitral valve. An abscess was found within the aneurysmal cavity.

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med 1994; 96:200–209.

- Prendergast BD. Diagnostic criteria and problems in infective endocarditis. Heart 2004; 90:611–613.

- Gonzalez-Lavin L, Lise M, Ross D. The importance of the ‘jet lesion’ in bacterial endocarditis involving the left heart. Surgical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970; 59:185–192.

- Silbiger JJ. Review: mitral valve aneurysms in infective endocarditis: mechanisms, clinical recognition, and treatment. J Heart Valve Dis 2009; 18:476–480.

- Reid CL, Chandraratna AN, Harrison E, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm: clinical features, echocardiographic-pathologic correlations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 2:460–464.

- Rodbard S. Blood velocity and endocarditis. Circulation 1963; 27:18–28.

- Piper C, Hetzer R, Körfer R, Bergemann R, Horstkotte D. The importance of secondary mitral valve involvement in primary aortic valve endocarditis; the mitral kissing vegetation. Eur Heart J 2002; 23:79–86.

- Cziner DG, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, Keller AM, Daniel WG, Kronzon I. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing mitral valve perforation. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69:1495–1497.

- Roberts PF, Serra AJ, McNicholas KW, Shapira N, Lemole GM. Atrial blood cyst: a rare finding. Ann Thorac Surg 1996; 62:880–882.

- Grimaldi A, Capritti E, Pappalardo F, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: blood cyst of the mitral valve. J Cardiovasc Med 2012; 3:46.

- Boyd WC, Rosengart TK, Hartman GS. Isolated left ventricular diverticulum in an adult. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1999; 13:468–470.

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med 1994; 96:200–209.

- Prendergast BD. Diagnostic criteria and problems in infective endocarditis. Heart 2004; 90:611–613.

- Gonzalez-Lavin L, Lise M, Ross D. The importance of the ‘jet lesion’ in bacterial endocarditis involving the left heart. Surgical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970; 59:185–192.

- Silbiger JJ. Review: mitral valve aneurysms in infective endocarditis: mechanisms, clinical recognition, and treatment. J Heart Valve Dis 2009; 18:476–480.

- Reid CL, Chandraratna AN, Harrison E, et al. Mitral valve aneurysm: clinical features, echocardiographic-pathologic correlations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 2:460–464.

- Rodbard S. Blood velocity and endocarditis. Circulation 1963; 27:18–28.

- Piper C, Hetzer R, Körfer R, Bergemann R, Horstkotte D. The importance of secondary mitral valve involvement in primary aortic valve endocarditis; the mitral kissing vegetation. Eur Heart J 2002; 23:79–86.

- Cziner DG, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, Keller AM, Daniel WG, Kronzon I. Transesophageal versus transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing mitral valve perforation. Am J Cardiol 1992; 69:1495–1497.

- Roberts PF, Serra AJ, McNicholas KW, Shapira N, Lemole GM. Atrial blood cyst: a rare finding. Ann Thorac Surg 1996; 62:880–882.

- Grimaldi A, Capritti E, Pappalardo F, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine: blood cyst of the mitral valve. J Cardiovasc Med 2012; 3:46.

- Boyd WC, Rosengart TK, Hartman GS. Isolated left ventricular diverticulum in an adult. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 1999; 13:468–470.

In reply: The negative U wave in the setting of demand ischemia

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: It’s in the details

A 72-year-old man with a 15-year history of a heart murmur presents to his cardiologist with shortness of breath on exertion over the past 12 months. He otherwise feels well and reports no chest discomfort, palpitations, or swelling of his legs or feet. He is not taking any cardiac drugs, and his health has previously been excellent.

Q: Which of the following findings on 12-lead ECG is not commonly reported in chronic severe aortic regurgitation?

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- QRS complex left-axis deviation

- A negative U wave

- Atrial fibrillation

A: The correct answer is a negative U wave.

In long-standing left ventricular volume overload, such as in chronic aortic regurgitation, characteristic findings on ECG include lateral precordial narrow Q waves and left ventricular hypertrophy. The ST segment and T wave are often normal or nearly normal. The QRS complex vector may demonstrate left-axis deviation, but this is not absolute. In contrast, pressure overload conditions such as aortic stenosis and systemic hypertension commonly manifest as left ventricular hypertrophy with strain pattern of ST depression in lateral precordial leads and asymmetric T-wave inversion.

A negative U wave, best identified in leads V4 to V6, is a common finding in left ventricular volume overload. A negative U wave represents a negative deflection of small amplitude (normally < 0.1 to 3 mV) immediately following the T wave. Although not routinely reported, the negative U wave is an indicator of underlying structural heart disease.1

Q: A negative U wave has been associated with which of the following conditions?

- Aortic or mitral regurgitation

- Myocardial ischemia

- Hypertension

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

Negative U waves have been identified in regurgitant valvular heart disease with left ventricular volume overload, in myocardial ischemia, 2,3 and in hypertension.4 During exercise stress testing, the transient appearance of negative U waves strongly suggests flow-limiting coronary artery disease. Moreover, changes in the U wave during exercise stress testing may be a sign of well-developed coronary collaterals.5 Therefore, it is prudent to note their presence on resting ECG and to investigate further with cardiac stress testing and imaging.

The pathogenesis of the negative U wave remains unclear. Of the various hypotheses put forth, a mechano-electric phenomenon may best explain its diverse pathology.

- Correale E, Battista R, Ricciardiello V, Martone A. The negative U wave: a pathogenetic enigma but a useful, often overlooked bedside diagnostic and prognostic clue in ischemic heart disease. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:674–677.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Lambert J. Clinical study of the abnormalities of the terminal complex TU-U of the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1957; 15:102–104.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

A 72-year-old man with a 15-year history of a heart murmur presents to his cardiologist with shortness of breath on exertion over the past 12 months. He otherwise feels well and reports no chest discomfort, palpitations, or swelling of his legs or feet. He is not taking any cardiac drugs, and his health has previously been excellent.

Q: Which of the following findings on 12-lead ECG is not commonly reported in chronic severe aortic regurgitation?

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- QRS complex left-axis deviation

- A negative U wave

- Atrial fibrillation

A: The correct answer is a negative U wave.

In long-standing left ventricular volume overload, such as in chronic aortic regurgitation, characteristic findings on ECG include lateral precordial narrow Q waves and left ventricular hypertrophy. The ST segment and T wave are often normal or nearly normal. The QRS complex vector may demonstrate left-axis deviation, but this is not absolute. In contrast, pressure overload conditions such as aortic stenosis and systemic hypertension commonly manifest as left ventricular hypertrophy with strain pattern of ST depression in lateral precordial leads and asymmetric T-wave inversion.

A negative U wave, best identified in leads V4 to V6, is a common finding in left ventricular volume overload. A negative U wave represents a negative deflection of small amplitude (normally < 0.1 to 3 mV) immediately following the T wave. Although not routinely reported, the negative U wave is an indicator of underlying structural heart disease.1

Q: A negative U wave has been associated with which of the following conditions?

- Aortic or mitral regurgitation

- Myocardial ischemia

- Hypertension

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

Negative U waves have been identified in regurgitant valvular heart disease with left ventricular volume overload, in myocardial ischemia, 2,3 and in hypertension.4 During exercise stress testing, the transient appearance of negative U waves strongly suggests flow-limiting coronary artery disease. Moreover, changes in the U wave during exercise stress testing may be a sign of well-developed coronary collaterals.5 Therefore, it is prudent to note their presence on resting ECG and to investigate further with cardiac stress testing and imaging.

The pathogenesis of the negative U wave remains unclear. Of the various hypotheses put forth, a mechano-electric phenomenon may best explain its diverse pathology.

A 72-year-old man with a 15-year history of a heart murmur presents to his cardiologist with shortness of breath on exertion over the past 12 months. He otherwise feels well and reports no chest discomfort, palpitations, or swelling of his legs or feet. He is not taking any cardiac drugs, and his health has previously been excellent.

Q: Which of the following findings on 12-lead ECG is not commonly reported in chronic severe aortic regurgitation?

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- QRS complex left-axis deviation

- A negative U wave

- Atrial fibrillation

A: The correct answer is a negative U wave.

In long-standing left ventricular volume overload, such as in chronic aortic regurgitation, characteristic findings on ECG include lateral precordial narrow Q waves and left ventricular hypertrophy. The ST segment and T wave are often normal or nearly normal. The QRS complex vector may demonstrate left-axis deviation, but this is not absolute. In contrast, pressure overload conditions such as aortic stenosis and systemic hypertension commonly manifest as left ventricular hypertrophy with strain pattern of ST depression in lateral precordial leads and asymmetric T-wave inversion.

A negative U wave, best identified in leads V4 to V6, is a common finding in left ventricular volume overload. A negative U wave represents a negative deflection of small amplitude (normally < 0.1 to 3 mV) immediately following the T wave. Although not routinely reported, the negative U wave is an indicator of underlying structural heart disease.1

Q: A negative U wave has been associated with which of the following conditions?

- Aortic or mitral regurgitation

- Myocardial ischemia

- Hypertension

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

Negative U waves have been identified in regurgitant valvular heart disease with left ventricular volume overload, in myocardial ischemia, 2,3 and in hypertension.4 During exercise stress testing, the transient appearance of negative U waves strongly suggests flow-limiting coronary artery disease. Moreover, changes in the U wave during exercise stress testing may be a sign of well-developed coronary collaterals.5 Therefore, it is prudent to note their presence on resting ECG and to investigate further with cardiac stress testing and imaging.

The pathogenesis of the negative U wave remains unclear. Of the various hypotheses put forth, a mechano-electric phenomenon may best explain its diverse pathology.

- Correale E, Battista R, Ricciardiello V, Martone A. The negative U wave: a pathogenetic enigma but a useful, often overlooked bedside diagnostic and prognostic clue in ischemic heart disease. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:674–677.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Lambert J. Clinical study of the abnormalities of the terminal complex TU-U of the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1957; 15:102–104.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Correale E, Battista R, Ricciardiello V, Martone A. The negative U wave: a pathogenetic enigma but a useful, often overlooked bedside diagnostic and prognostic clue in ischemic heart disease. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:674–677.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Lambert J. Clinical study of the abnormalities of the terminal complex TU-U of the electrocardiogram. Circulation 1957; 15:102–104.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.