User login

Prognostication in Hospice Care: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Importance of Functional Status

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

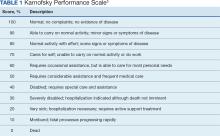

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

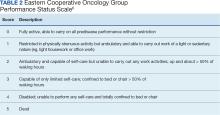

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

1. Cleary TA. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) Version 2. In: Downing GM, ed. Medical Care of the Dying. 4th ed. Victoria Hospice Society, Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006:120.

2. Palliative Performance Scale. ePrognosis, University of California San Francisco. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/pps.php

3. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

4. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-305.

5. Karnofsky Performance Scale. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp

6. Mischel A-M, Rosielle DA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. December 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/eastern-cooperative-oncology-group-performance-status/

7. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655.

8. Nizamutdinov D, Stock EM, Dandashi JA, et al. Prognostication of survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e67-e74. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.104

9. Kita D Ciernik IFVaccarella S Age as a predictive factor in glioblastomas: population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(1):17-22. doi:10.1159/000210017

10. Jordan JT, Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Plotkin SR. Glioblastoma care in the elderly. Cancer. 2016;122(2):189-197. doi:10.1002/cnr.29742

11. Brown, NF, Ottaviani D, Tazare J, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13):3161. doi:10.3390/cancers14133161

12. Christalakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. University of Chicago Press; 2000.

13. Weissman DE. Determining Prognosis in Advanced Cancer. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. January 28, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2014. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/determining-prognosis-in-advanced-cancer/

14. Childers JW, Arnold R, Curtis JR. Prognosis in End-Stage COPD. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognosis-in-end-stage-copd/

15. Reisfield GM, Wilson GR. Prognostication in Heart Failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognostication-in-heart-failure/

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

Predicting life expectancy and providing an end-of-life diagnosis in hospice and palliative care is a challenge for most clinicians. Lack of training, limited communication skills, and relationships with patients are all contributing factors. These skills can improve with the use of functional scoring tools in conjunction with the patient’s comorbidities and physical/psychological symptoms. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) are commonly used functional scoring tools.

The PPS measures 5 functional dimensions including ambulation, activity level, ability to administer self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness.1 It has been shown to be valid for a broad range of palliative care patients, including those with advanced cancer or life-threatening noncancer diagnoses in hospitals or hospice care.2 The scale, measured in 10% increments, runs from 100% (completely functional) to 0% (dead). A PPS ≤ 70% helps meet hospice eligibility criteria.

The KPS evaluates functional impairment and helps with prognostication. Developed in 1948, it evaluates a patient’s functional ability to tolerate chemotherapy, specifically in lung cancer, and has since been validated to predict mortality across older adults and in chronic disease populations.3,4 The KPS is also measured in 10% increments ranging from 100% (completely functional without assistance) to 0% (dead). A KPS ≤ 70% assists with hospice eligibility criteria (Table 1).5

Developed in 1974, the ECOG has been identified as one of the most important functional status tools in adult cancer care.6 It describes a cancer patient’s functional ability, evaluating their ability to care for oneself and participate in daily activities.7 The ECOG is a 6-point scale; patients can receive scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead). An ECOG score of 4 (sometimes 3) is generally supportive of meeting hospice eligibility (Table 2).6

CASE Presentation

An 80-year-old patient was admitted to the hospice service at the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) community living center (CLC) in Tacoma, Washington, from a community-based acute care hospital. His medical history included prostate cancer with metastasis to his pelvis and type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was stable with treatment with oral medication. Six weeks earlier the patient reported a severe frontal headache that was not responding to over-the-counter analgesics. After 2 days with these symptoms, including a ground-level fall without injuries, he presented to the VAPSHCS emergency department (ED) where a complete neurological examination, including magnetic resonance imaging, revealed a left frontoparietal brain lesion that was 4.2 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.2 cm.

The patient experienced a seizure during his ED evaluation and was admitted for treatment. He underwent a craniotomy where most, but not all the lesions were successfully removed. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited right-sided neglect, gait instability, emotional lability, and cognitive communication disorder. The patient completed 15 of 20 planned radiation treatments but declined further radiation or chemotherapy. The patient decided to halt radiation treatments after being informed by the oncology service that the treatments would likely only add 1 to 2 months to his overall survival, which was < 6 months. The patient elected to focus his goals of care on comfort, dignity, and respect at the end of life and accepted recommendations to be placed into end-of-life hospice care. He was then transferred to the VAPSHCS CLC in Tacoma, Washington, for hospice care.

Upon admission, the patient weighed 94 kg, his vital signs were within reference range, and he reported no pain or headaches. His initial laboratory results revealed a 13.2 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.6 g/dL serum albumin, and a 5.5% hemoglobin A1c, all of which fall into a normal reference range. He had a reported ECOG score of 3 and a KPS score of 50% by the transferring medical team. The patient’s medications included scheduled dexamethasone, metformin, senna, levetiracetam, and as-needed midazolam nasal spray for breakthrough seizures. He also had as-needed acetaminophen for pain. He was alert, oriented ×3, and fully ambulatory but continuously used a 4-wheeled walker for safety and gait instability.

After the patient’s first night, the hospice team met with him to discuss his understanding of his health issues. The patient appeared to have low health literacy but told the team, “I know I am dying.” He had completed written advance directives and a Portable Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment indicating that life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, supplemental mechanical feeding, or intubation, were not to be used to keep him alive.

At his first 90-day recertification, the patient had gained 8 kg and laboratory results revealed a 14.6 g/dL hemoglobin, 3.8 g/dL serum albumin, and a 6.1% hemoglobin A1c. His ECOG score remained at 3, but his KPS score had increased to 60%. The patient exhibited no new neurologic symptoms or seizures and reported no headaches but had 2 ground-level falls without injury. On both occasions the patient chose not to use his walker to go to the bathroom because it was “too far from my bed.” Per VA policy, after discussions with the hospice team, he was recertified for 90 more days of hospice care. At the end of 6 months in CLC, the patient’s weight remained stable, as did his complete blood count and comprehensive medical panel. He had 1 additional noninjurious ground-level fall and again reported no pain and no use of as-needed acetaminophen. His only medical complication was testing positive for COVID-19, but he remained asymptomatic. The patient was graduated from hospice care and referred to a nearby non-VA adult family home in the community after 180 days. At that time his ECOG score was 2 and his KPS score had increased to 70%.

DISCUSSION

Primary brain tumors account for about 2% of all malignant neoplasms in adults. About half of them represent gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme derived from neuroepithelial cells is the most frequent and deadly primary malignant central nervous system tumor in adults.8 About 50% of patients with glioblastomas are aged ≥ 65 years at diagnosis.9 A retrospective study of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services claims data paired with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database indicated a median survival of 4 months for patients with glioblastoma multiforme aged > 65 years, including all treatment modalities.10 Surgical resection combined with radiation and chemotherapy offers the best prognosis for the preservation of neurologic function.11 However, comorbidities, adverse drug effects, and the potential for postoperative complications pose significant risks, especially for older patients. Ultimately, goals of care conversations and advance directives play a very important role in evaluating benefits vs risks with this malignancy.

Our patient was aged 80 years and had previously been diagnosed with metastatic prostate malignancy. His goals of care focused on spending time with his friends, leaving his room to eat in the facility dining area, and continuing his daily walks. He remained clear that he did not want his care team to institute life-sustaining treatments to be kept alive and felt the information regarding the risks vs benefits of accepting chemotherapy was not aligned with his goals of care. Over the 6 months that he received hospice care, he gained weight, improved his hemoglobin and serum albumin levels, and ambulated with the use of a 4-wheeled walker. As the patient exhibited no functional decline or new comorbidities and his functional status improved, the clinical staff felt he no longer needed hospice services. The patient had an ECOG score of 2 and a KPS score of 70% at his hospice graduation.

Medical prognostication is one of the biggest challenges clinicians face. Clinicians are generally “over prognosticators,” and their thoughts tend to be based on the patient relationship, overall experiences in health care, and desire to treat and cure patients.12 In hospice we are asked to define the usual, normal, or expected course of a disease, but what does that mean? Although metastatic malignancies usually have a predictable course in comparison to diagnoses such as dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure, the challenges to improve prognostic ability andpredict disease course continue.13-15 Focusing on functional status, goals of care, and comorbidities are keys to helping with prognosis. Given the challenge, we find the PPS, KPS, and ECOG scales important tools.

When prognosticating, we attempt to define quantity and quality of life (which our patients must define independently or from the voice of their surrogate) and their ability to perform daily activities. Quality of life in patients with glioblastoma is progressively and significantly impacted due to the emergence of debilitating neurologic symptoms arising from infiltrative tumor growth into functionally intact brain tissue that restricts and disrupts normal day-to-day activities. However, functional status plays a significant role in helping the hospice team improve its overall prognosis.

Conclusions

This case study illustrates the difficulty that comes with prognostication(s) despite a patient's severely morbid disease, history of metastatic prostate cancer, and advanced age. Although a diagnosis may be concerning, documenting a patient’s status using functional scales prior to hospice admission and during the recertification process is helpful in prognostication. Doing so will allow health care professionals to have an accepted medical standard to use regardless how distinct the patient's diagnosis. The expression, “as the disease does not read the textbook,” may serve as a helpful reminder in talking with patients and their families. This is important as most patient’s clinical disease courses are different and having the opportunity to use performance status scales may help improve prognostic skills.

1. Cleary TA. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) Version 2. In: Downing GM, ed. Medical Care of the Dying. 4th ed. Victoria Hospice Society, Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006:120.

2. Palliative Performance Scale. ePrognosis, University of California San Francisco. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/pps.php

3. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

4. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-305.

5. Karnofsky Performance Scale. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp

6. Mischel A-M, Rosielle DA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. December 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/eastern-cooperative-oncology-group-performance-status/

7. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655.

8. Nizamutdinov D, Stock EM, Dandashi JA, et al. Prognostication of survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e67-e74. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.104

9. Kita D Ciernik IFVaccarella S Age as a predictive factor in glioblastomas: population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(1):17-22. doi:10.1159/000210017

10. Jordan JT, Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Plotkin SR. Glioblastoma care in the elderly. Cancer. 2016;122(2):189-197. doi:10.1002/cnr.29742

11. Brown, NF, Ottaviani D, Tazare J, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13):3161. doi:10.3390/cancers14133161

12. Christalakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. University of Chicago Press; 2000.

13. Weissman DE. Determining Prognosis in Advanced Cancer. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. January 28, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2014. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/determining-prognosis-in-advanced-cancer/

14. Childers JW, Arnold R, Curtis JR. Prognosis in End-Stage COPD. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognosis-in-end-stage-copd/

15. Reisfield GM, Wilson GR. Prognostication in Heart Failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognostication-in-heart-failure/

1. Cleary TA. The Palliative Performance Scale (PPSv2) Version 2. In: Downing GM, ed. Medical Care of the Dying. 4th ed. Victoria Hospice Society, Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006:120.

2. Palliative Performance Scale. ePrognosis, University of California San Francisco. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu/pps.php

3. Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

4. Khalid MA, Achakzai IK, Ahmed Khan S, et al. The use of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) as a predictor of 3 month post discharge mortality in cirrhotic patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2018;11(4):301-305.

5. Karnofsky Performance Scale. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/tools/karnofsky-performance-scale.asp

6. Mischel A-M, Rosielle DA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. December 10, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/eastern-cooperative-oncology-group-performance-status/

7. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-655.

8. Nizamutdinov D, Stock EM, Dandashi JA, et al. Prognostication of survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e67-e74. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.104

9. Kita D Ciernik IFVaccarella S Age as a predictive factor in glioblastomas: population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;33(1):17-22. doi:10.1159/000210017

10. Jordan JT, Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Plotkin SR. Glioblastoma care in the elderly. Cancer. 2016;122(2):189-197. doi:10.1002/cnr.29742

11. Brown, NF, Ottaviani D, Tazare J, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13):3161. doi:10.3390/cancers14133161

12. Christalakis NA. Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care. University of Chicago Press; 2000.

13. Weissman DE. Determining Prognosis in Advanced Cancer. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. January 28, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2014. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/determining-prognosis-in-advanced-cancer/

14. Childers JW, Arnold R, Curtis JR. Prognosis in End-Stage COPD. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognosis-in-end-stage-copd/

15. Reisfield GM, Wilson GR. Prognostication in Heart Failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. February 11, 2019. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/prognostication-in-heart-failure/

Scheduled Acetaminophen to Minimize Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

To manage the physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms of a veteran hospitalized for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome secondary to chronic alcohol overuse, acetaminophen was administered in place of psychoactive medications.

Alcohol is the most common substance misused by veterans. 1 Veterans may m isuse alcohol as a result of mental illness or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), having difficulties adjusting to civilian life, or because of heavy drinking habits acquired before leaving active duty. 2 One potential long-term effect of chronic alcohol misuse is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS), a neuropsychiatric condition secondary to a deficiency of thiamine. 3 The disease is characterized by altered mental status, oculomotor findings, and ataxia. 3 Patients with WKS may exhibit challenging behaviors, including aggression, disinhibition, and lack of awareness of their illness. 4 Due to long-standing cognitive and physical deficits, many patients require lifelong care with a focus on a palliative approach. 3

The mainstay of pharmacologic management for the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS continues to be psychoactive medications, such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and anticonvulsant medications.4-6 Though atypical antipsychotic medications remain the most widely used, they have a high adverse effect (AE) profile.5,6 Among the potential AEs are metabolic syndrome, anticholinergic effects, QTc prolongation, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal effects, sedation, and falls. There also is a US Food and Drug Administration boxed warning for increased risk of mortality.7 With the goal of improving and maintaining patient safety, pharmacologic interventions with lower AEs may be beneficial in the management of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS.

This case describes a veteran who was initially hospitalized due to confusion, ataxia, and nystagmus secondary to chronic alcohol overuse. The aim of the case was to consider the use of acetaminophen in place of psychoactive medications as a way to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS even when pain was not present.

Case Presentation

A veteran presented to the local US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) emergency department (ED) due to their spouse’s concern of acute onset confusion and ambulatory difficulties. The veteran’s medical history included extensive alcohol misuse, mild asthma, and diet-controlled hyperlipidemia. On initial evaluation, the veteran displayed symptoms of ataxia and confusion. When asked why the veteran was at the ED, the response was, “I just came to the hospital to find my sister.” Based on their medical history, clinical evaluation, and altered mental status, the veteran was admitted to the acute care medical service with a presumptive diagnosis of WKS.

On admission, the laboratory evaluation revealed normal alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels but markedly elevated γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) consistent with alcohol toxicity. COVID-19 testing was negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed evidence of alterations in the mammillary bodies and moderately severe cortical and cerebellar volume loss suggestive of long-standing alcohol use.

The veteran was hospitalized for 12 days and treated with high-dose IV thiamine, which resulted in improvement of their ophthalmic disorder (nystagmus) and ataxia. However, they continued to exhibit poor recall, confusion, and occasional agitation characterized by verbal outbursts and aggression toward the staff.

The veteran’s spouse worked full time and did not feel capable of providing the necessary follow-up care at home. The safest discharge plan found was to transfer the veteran to the local VA community living center (CLC) for physical therapy and further support of their marked cognitive decline and agitation.

Following admission to the CLC, the veteran was placed in a secured memory unit with staff trained specifically on management of veterans with cognitive impairment and behavioral concerns. As the veteran did not have decisional capacity on admission, the staff arranged a meeting with the spouse. Based on that conversation, the goals of care were to focus on a palliative approach and the hope that the veteran would one day be able to return home to their spouse.

At the CLC, the veteran was initially treated with thiamine 200 mg orally once daily and albuterol inhaler as needed. A clinical psychologist performed a comprehensive psychological evaluation on admission, which confirmed evidence of WKS with symptoms, including confusion, disorientation, and confabulation. There was no evidence of cultural diversity factors regarding the veteran’s delusional beliefs.

After the first full day in the CLC, the nursing staff observed anger and agitation that seemed to start midafternoon and continued until around dinnertime. The veteran displayed verbal outbursts, refusal to cooperate with the staff, and multiple attempts to leave the CLC. With the guidance of a geriatric psychiatrist, risperidone 1 mg once daily as needed was initiated, and staff continued with verbal redirection, both with limited efficacy. After 3 days, due to safety concerns for the veteran, other CLC patients, and CLC staff, risperidone dosing was increased to 1 mg twice daily, which had limited efficacy. Lorazepam 1 mg once daily also was added. A careful medication review was performed to minimize any potential AEs or interactions that might have contributed to the veteran’s behavior, but no pharmacologic interventions were found to fully abate their behavioral issues.

After 5 weeks of ongoing intermittent behavioral issues, the medical team again met to discuss new treatment options.A case reported by Husebo and colleagues used scheduled acetaminophen to help relieve neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in a patient who exhibited similar behavioral issues and did not respond well to antipsychotics or benzodiazepines.8 Although our veteran did not express or exhibit obvious pain, the medical team chose to trial this intervention, and the veteran was started on acetaminophen 650 mg orally 3 times daily. A comprehensive metabolic panel, including GGT and thyroid-stimulating hormone, was performed before starting acetaminophen; no abnormalities were noted. The clinical examination did not reveal physical abnormalities other than ataxia.

After 5 days of therapy with the scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran’s clinical behavior dramatically improved. The veteran exhibited infrequent agitated behavior and became cooperative with staff. Three days later, the scheduled lorazepam was discontinued, and eventually they were tapered off risperidone. One month after starting scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran had improved to a point where the staff determined a safe discharge plan could be initiated. The veteran’s nystagmus resolved and behavioral issues improved, although cognitive impairment persisted.

Due to COVID-19, a teleconference was scheduled with the veteran’s spouse to discuss a discharge plan. The spouse was pleased that the veteran had progressed adequately both functionally and behaviorally to make a safe discharge home possible. The spouse arranged to take family leave from their job to help support the veteran after discharge. The veteran was able to return home with a safe discharge plan 1 week later. The acetaminophen was continued with twice-daily dosing and was continued because there were no new behavioral issues. This was done to enhance postfacility adherence and minimize the risk of drug-drug interactions. Attempts to follow up with the veteran postdischarge were unfortunately unsuccessful as the family lived out of the local area.

Discussion

Alcohol misuse is a common finding in many US veterans, as well as in the general population.1,3 As a result, it is not uncommon to see patients with physical and psychological symptoms related to this abuse. Many of these patients will become verbally and physically abusive, thus having appropriate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions is important.

In this case study, the veteran was diagnosed with WKS and exhibited physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms consistent with this disease. Although the physical symptoms improved with thiamine and abstinence from alcohol, their cognitive impairment, verbal outbursts, and aggressive demeanor persisted.

After using antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications with minimal clinical improvement, a trial of acetaminophen 650 mg 3 times daily was instituted. The patient’s behavior improved; demeanor became calmer, and they were easily redirected by the nursing staff. Psychological support was again employed, which enhanced and supported the veteran’s calmer demeanor. Although there is limited medical literature on the use of acetaminophen in clinical situations not related to pain, there has been research documenting its effect on social interaction.9,10

Acetaminophen is an analgesic medication that acts through central neural mechanisms. It has been hypothesized that social and physical pain rely on shared neurochemical underpinnings, and some of the regions of the brain involved in affective experience of physical pain also have been found to be involved in the experience of social pain.11 Acetaminophen may impact an individual’s social well-being as social pain processes.11 It has been shown to blunt reactivity to both physical pain as well as negative stimuli.11

Conclusions

A 2019 survey on alcohol and drug use found 5.6% of adults aged ≥ 18 have an alcohol use disorder.12 In severe cases, this can result in WKS. Although replacement of thiamine is critical for physical improvement, psychological deficits may persist. Small studies have advanced the concept of using scheduled acetaminophen even when the patient is not verbalizing or displaying pain.13 Although more research needs to be done on this topic, this palliative approach may be worth considering, especially if the risks of antipsychotics and anxiolytics outweigh the benefits.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Substance use and military life drug facts. Published October 2019. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-use-military-life

2. National Veterans Foundation. What statistics show about veteran substance abuse and why proper treatment is important. Published March 30, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://nvf.org/veteran-substance-abuse-statistics

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Korsakoff syndrome. Updated July 10, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539854

4. Gerridzen IJ, Goossensen MA. Patients with Korsakoff syndrome in nursing homes: characteristics, comorbidity, and use of psychotropic drugs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):115-121. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001543

5. Press D, Alexander M. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Updated October 2021. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-neuropsychiatric-symptoms-of-dementia

6. Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: Managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):900-906. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342

7. Jibson MD. Second-generation antipsychotic medications: pharmacology, administration, and side effects. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/second-generation-antipsychotic-medications-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

8. Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4065. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4065

9. Fung K, Alden LE. Once hurt, twice shy: social pain contributes to social anxiety. Emotion. 2017;(2):231-239. doi:10.1037/emo0000223

10. Roberts ID, Krajbich I, Cheavens JS, Campo JV, Way BM. Acetaminophen Reduces Distrust in Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder Features. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):145-154. doi:10.1177/2167702617731374

11. Dewall CN, Macdonald G, Webster GD, et al. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(7):931-937. doi:10.1177/0956797610374741

12. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics. Updated June 2021. Accessed November 2, 202November 10, 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

13. Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, Luebbert RA. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2005;53(11):1921-9. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53572.x

To manage the physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms of a veteran hospitalized for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome secondary to chronic alcohol overuse, acetaminophen was administered in place of psychoactive medications.

To manage the physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms of a veteran hospitalized for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome secondary to chronic alcohol overuse, acetaminophen was administered in place of psychoactive medications.

Alcohol is the most common substance misused by veterans. 1 Veterans may m isuse alcohol as a result of mental illness or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), having difficulties adjusting to civilian life, or because of heavy drinking habits acquired before leaving active duty. 2 One potential long-term effect of chronic alcohol misuse is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS), a neuropsychiatric condition secondary to a deficiency of thiamine. 3 The disease is characterized by altered mental status, oculomotor findings, and ataxia. 3 Patients with WKS may exhibit challenging behaviors, including aggression, disinhibition, and lack of awareness of their illness. 4 Due to long-standing cognitive and physical deficits, many patients require lifelong care with a focus on a palliative approach. 3

The mainstay of pharmacologic management for the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS continues to be psychoactive medications, such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and anticonvulsant medications.4-6 Though atypical antipsychotic medications remain the most widely used, they have a high adverse effect (AE) profile.5,6 Among the potential AEs are metabolic syndrome, anticholinergic effects, QTc prolongation, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal effects, sedation, and falls. There also is a US Food and Drug Administration boxed warning for increased risk of mortality.7 With the goal of improving and maintaining patient safety, pharmacologic interventions with lower AEs may be beneficial in the management of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS.

This case describes a veteran who was initially hospitalized due to confusion, ataxia, and nystagmus secondary to chronic alcohol overuse. The aim of the case was to consider the use of acetaminophen in place of psychoactive medications as a way to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS even when pain was not present.

Case Presentation

A veteran presented to the local US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) emergency department (ED) due to their spouse’s concern of acute onset confusion and ambulatory difficulties. The veteran’s medical history included extensive alcohol misuse, mild asthma, and diet-controlled hyperlipidemia. On initial evaluation, the veteran displayed symptoms of ataxia and confusion. When asked why the veteran was at the ED, the response was, “I just came to the hospital to find my sister.” Based on their medical history, clinical evaluation, and altered mental status, the veteran was admitted to the acute care medical service with a presumptive diagnosis of WKS.

On admission, the laboratory evaluation revealed normal alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels but markedly elevated γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) consistent with alcohol toxicity. COVID-19 testing was negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed evidence of alterations in the mammillary bodies and moderately severe cortical and cerebellar volume loss suggestive of long-standing alcohol use.

The veteran was hospitalized for 12 days and treated with high-dose IV thiamine, which resulted in improvement of their ophthalmic disorder (nystagmus) and ataxia. However, they continued to exhibit poor recall, confusion, and occasional agitation characterized by verbal outbursts and aggression toward the staff.

The veteran’s spouse worked full time and did not feel capable of providing the necessary follow-up care at home. The safest discharge plan found was to transfer the veteran to the local VA community living center (CLC) for physical therapy and further support of their marked cognitive decline and agitation.

Following admission to the CLC, the veteran was placed in a secured memory unit with staff trained specifically on management of veterans with cognitive impairment and behavioral concerns. As the veteran did not have decisional capacity on admission, the staff arranged a meeting with the spouse. Based on that conversation, the goals of care were to focus on a palliative approach and the hope that the veteran would one day be able to return home to their spouse.

At the CLC, the veteran was initially treated with thiamine 200 mg orally once daily and albuterol inhaler as needed. A clinical psychologist performed a comprehensive psychological evaluation on admission, which confirmed evidence of WKS with symptoms, including confusion, disorientation, and confabulation. There was no evidence of cultural diversity factors regarding the veteran’s delusional beliefs.

After the first full day in the CLC, the nursing staff observed anger and agitation that seemed to start midafternoon and continued until around dinnertime. The veteran displayed verbal outbursts, refusal to cooperate with the staff, and multiple attempts to leave the CLC. With the guidance of a geriatric psychiatrist, risperidone 1 mg once daily as needed was initiated, and staff continued with verbal redirection, both with limited efficacy. After 3 days, due to safety concerns for the veteran, other CLC patients, and CLC staff, risperidone dosing was increased to 1 mg twice daily, which had limited efficacy. Lorazepam 1 mg once daily also was added. A careful medication review was performed to minimize any potential AEs or interactions that might have contributed to the veteran’s behavior, but no pharmacologic interventions were found to fully abate their behavioral issues.

After 5 weeks of ongoing intermittent behavioral issues, the medical team again met to discuss new treatment options.A case reported by Husebo and colleagues used scheduled acetaminophen to help relieve neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in a patient who exhibited similar behavioral issues and did not respond well to antipsychotics or benzodiazepines.8 Although our veteran did not express or exhibit obvious pain, the medical team chose to trial this intervention, and the veteran was started on acetaminophen 650 mg orally 3 times daily. A comprehensive metabolic panel, including GGT and thyroid-stimulating hormone, was performed before starting acetaminophen; no abnormalities were noted. The clinical examination did not reveal physical abnormalities other than ataxia.

After 5 days of therapy with the scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran’s clinical behavior dramatically improved. The veteran exhibited infrequent agitated behavior and became cooperative with staff. Three days later, the scheduled lorazepam was discontinued, and eventually they were tapered off risperidone. One month after starting scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran had improved to a point where the staff determined a safe discharge plan could be initiated. The veteran’s nystagmus resolved and behavioral issues improved, although cognitive impairment persisted.

Due to COVID-19, a teleconference was scheduled with the veteran’s spouse to discuss a discharge plan. The spouse was pleased that the veteran had progressed adequately both functionally and behaviorally to make a safe discharge home possible. The spouse arranged to take family leave from their job to help support the veteran after discharge. The veteran was able to return home with a safe discharge plan 1 week later. The acetaminophen was continued with twice-daily dosing and was continued because there were no new behavioral issues. This was done to enhance postfacility adherence and minimize the risk of drug-drug interactions. Attempts to follow up with the veteran postdischarge were unfortunately unsuccessful as the family lived out of the local area.

Discussion

Alcohol misuse is a common finding in many US veterans, as well as in the general population.1,3 As a result, it is not uncommon to see patients with physical and psychological symptoms related to this abuse. Many of these patients will become verbally and physically abusive, thus having appropriate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions is important.

In this case study, the veteran was diagnosed with WKS and exhibited physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms consistent with this disease. Although the physical symptoms improved with thiamine and abstinence from alcohol, their cognitive impairment, verbal outbursts, and aggressive demeanor persisted.

After using antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications with minimal clinical improvement, a trial of acetaminophen 650 mg 3 times daily was instituted. The patient’s behavior improved; demeanor became calmer, and they were easily redirected by the nursing staff. Psychological support was again employed, which enhanced and supported the veteran’s calmer demeanor. Although there is limited medical literature on the use of acetaminophen in clinical situations not related to pain, there has been research documenting its effect on social interaction.9,10

Acetaminophen is an analgesic medication that acts through central neural mechanisms. It has been hypothesized that social and physical pain rely on shared neurochemical underpinnings, and some of the regions of the brain involved in affective experience of physical pain also have been found to be involved in the experience of social pain.11 Acetaminophen may impact an individual’s social well-being as social pain processes.11 It has been shown to blunt reactivity to both physical pain as well as negative stimuli.11

Conclusions

A 2019 survey on alcohol and drug use found 5.6% of adults aged ≥ 18 have an alcohol use disorder.12 In severe cases, this can result in WKS. Although replacement of thiamine is critical for physical improvement, psychological deficits may persist. Small studies have advanced the concept of using scheduled acetaminophen even when the patient is not verbalizing or displaying pain.13 Although more research needs to be done on this topic, this palliative approach may be worth considering, especially if the risks of antipsychotics and anxiolytics outweigh the benefits.

Alcohol is the most common substance misused by veterans. 1 Veterans may m isuse alcohol as a result of mental illness or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), having difficulties adjusting to civilian life, or because of heavy drinking habits acquired before leaving active duty. 2 One potential long-term effect of chronic alcohol misuse is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS), a neuropsychiatric condition secondary to a deficiency of thiamine. 3 The disease is characterized by altered mental status, oculomotor findings, and ataxia. 3 Patients with WKS may exhibit challenging behaviors, including aggression, disinhibition, and lack of awareness of their illness. 4 Due to long-standing cognitive and physical deficits, many patients require lifelong care with a focus on a palliative approach. 3

The mainstay of pharmacologic management for the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS continues to be psychoactive medications, such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and anticonvulsant medications.4-6 Though atypical antipsychotic medications remain the most widely used, they have a high adverse effect (AE) profile.5,6 Among the potential AEs are metabolic syndrome, anticholinergic effects, QTc prolongation, orthostatic hypotension, extrapyramidal effects, sedation, and falls. There also is a US Food and Drug Administration boxed warning for increased risk of mortality.7 With the goal of improving and maintaining patient safety, pharmacologic interventions with lower AEs may be beneficial in the management of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS.

This case describes a veteran who was initially hospitalized due to confusion, ataxia, and nystagmus secondary to chronic alcohol overuse. The aim of the case was to consider the use of acetaminophen in place of psychoactive medications as a way to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms of WKS even when pain was not present.

Case Presentation

A veteran presented to the local US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) emergency department (ED) due to their spouse’s concern of acute onset confusion and ambulatory difficulties. The veteran’s medical history included extensive alcohol misuse, mild asthma, and diet-controlled hyperlipidemia. On initial evaluation, the veteran displayed symptoms of ataxia and confusion. When asked why the veteran was at the ED, the response was, “I just came to the hospital to find my sister.” Based on their medical history, clinical evaluation, and altered mental status, the veteran was admitted to the acute care medical service with a presumptive diagnosis of WKS.

On admission, the laboratory evaluation revealed normal alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels but markedly elevated γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) consistent with alcohol toxicity. COVID-19 testing was negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed evidence of alterations in the mammillary bodies and moderately severe cortical and cerebellar volume loss suggestive of long-standing alcohol use.

The veteran was hospitalized for 12 days and treated with high-dose IV thiamine, which resulted in improvement of their ophthalmic disorder (nystagmus) and ataxia. However, they continued to exhibit poor recall, confusion, and occasional agitation characterized by verbal outbursts and aggression toward the staff.

The veteran’s spouse worked full time and did not feel capable of providing the necessary follow-up care at home. The safest discharge plan found was to transfer the veteran to the local VA community living center (CLC) for physical therapy and further support of their marked cognitive decline and agitation.

Following admission to the CLC, the veteran was placed in a secured memory unit with staff trained specifically on management of veterans with cognitive impairment and behavioral concerns. As the veteran did not have decisional capacity on admission, the staff arranged a meeting with the spouse. Based on that conversation, the goals of care were to focus on a palliative approach and the hope that the veteran would one day be able to return home to their spouse.

At the CLC, the veteran was initially treated with thiamine 200 mg orally once daily and albuterol inhaler as needed. A clinical psychologist performed a comprehensive psychological evaluation on admission, which confirmed evidence of WKS with symptoms, including confusion, disorientation, and confabulation. There was no evidence of cultural diversity factors regarding the veteran’s delusional beliefs.

After the first full day in the CLC, the nursing staff observed anger and agitation that seemed to start midafternoon and continued until around dinnertime. The veteran displayed verbal outbursts, refusal to cooperate with the staff, and multiple attempts to leave the CLC. With the guidance of a geriatric psychiatrist, risperidone 1 mg once daily as needed was initiated, and staff continued with verbal redirection, both with limited efficacy. After 3 days, due to safety concerns for the veteran, other CLC patients, and CLC staff, risperidone dosing was increased to 1 mg twice daily, which had limited efficacy. Lorazepam 1 mg once daily also was added. A careful medication review was performed to minimize any potential AEs or interactions that might have contributed to the veteran’s behavior, but no pharmacologic interventions were found to fully abate their behavioral issues.

After 5 weeks of ongoing intermittent behavioral issues, the medical team again met to discuss new treatment options.A case reported by Husebo and colleagues used scheduled acetaminophen to help relieve neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in a patient who exhibited similar behavioral issues and did not respond well to antipsychotics or benzodiazepines.8 Although our veteran did not express or exhibit obvious pain, the medical team chose to trial this intervention, and the veteran was started on acetaminophen 650 mg orally 3 times daily. A comprehensive metabolic panel, including GGT and thyroid-stimulating hormone, was performed before starting acetaminophen; no abnormalities were noted. The clinical examination did not reveal physical abnormalities other than ataxia.

After 5 days of therapy with the scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran’s clinical behavior dramatically improved. The veteran exhibited infrequent agitated behavior and became cooperative with staff. Three days later, the scheduled lorazepam was discontinued, and eventually they were tapered off risperidone. One month after starting scheduled acetaminophen, the veteran had improved to a point where the staff determined a safe discharge plan could be initiated. The veteran’s nystagmus resolved and behavioral issues improved, although cognitive impairment persisted.

Due to COVID-19, a teleconference was scheduled with the veteran’s spouse to discuss a discharge plan. The spouse was pleased that the veteran had progressed adequately both functionally and behaviorally to make a safe discharge home possible. The spouse arranged to take family leave from their job to help support the veteran after discharge. The veteran was able to return home with a safe discharge plan 1 week later. The acetaminophen was continued with twice-daily dosing and was continued because there were no new behavioral issues. This was done to enhance postfacility adherence and minimize the risk of drug-drug interactions. Attempts to follow up with the veteran postdischarge were unfortunately unsuccessful as the family lived out of the local area.

Discussion

Alcohol misuse is a common finding in many US veterans, as well as in the general population.1,3 As a result, it is not uncommon to see patients with physical and psychological symptoms related to this abuse. Many of these patients will become verbally and physically abusive, thus having appropriate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions is important.

In this case study, the veteran was diagnosed with WKS and exhibited physical, cognitive, and emotional symptoms consistent with this disease. Although the physical symptoms improved with thiamine and abstinence from alcohol, their cognitive impairment, verbal outbursts, and aggressive demeanor persisted.

After using antipsychotic and anxiolytic medications with minimal clinical improvement, a trial of acetaminophen 650 mg 3 times daily was instituted. The patient’s behavior improved; demeanor became calmer, and they were easily redirected by the nursing staff. Psychological support was again employed, which enhanced and supported the veteran’s calmer demeanor. Although there is limited medical literature on the use of acetaminophen in clinical situations not related to pain, there has been research documenting its effect on social interaction.9,10

Acetaminophen is an analgesic medication that acts through central neural mechanisms. It has been hypothesized that social and physical pain rely on shared neurochemical underpinnings, and some of the regions of the brain involved in affective experience of physical pain also have been found to be involved in the experience of social pain.11 Acetaminophen may impact an individual’s social well-being as social pain processes.11 It has been shown to blunt reactivity to both physical pain as well as negative stimuli.11

Conclusions

A 2019 survey on alcohol and drug use found 5.6% of adults aged ≥ 18 have an alcohol use disorder.12 In severe cases, this can result in WKS. Although replacement of thiamine is critical for physical improvement, psychological deficits may persist. Small studies have advanced the concept of using scheduled acetaminophen even when the patient is not verbalizing or displaying pain.13 Although more research needs to be done on this topic, this palliative approach may be worth considering, especially if the risks of antipsychotics and anxiolytics outweigh the benefits.

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Substance use and military life drug facts. Published October 2019. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-use-military-life

2. National Veterans Foundation. What statistics show about veteran substance abuse and why proper treatment is important. Published March 30, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://nvf.org/veteran-substance-abuse-statistics

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Korsakoff syndrome. Updated July 10, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539854

4. Gerridzen IJ, Goossensen MA. Patients with Korsakoff syndrome in nursing homes: characteristics, comorbidity, and use of psychotropic drugs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):115-121. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001543

5. Press D, Alexander M. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Updated October 2021. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-neuropsychiatric-symptoms-of-dementia

6. Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: Managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):900-906. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342

7. Jibson MD. Second-generation antipsychotic medications: pharmacology, administration, and side effects. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/second-generation-antipsychotic-medications-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

8. Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4065. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4065

9. Fung K, Alden LE. Once hurt, twice shy: social pain contributes to social anxiety. Emotion. 2017;(2):231-239. doi:10.1037/emo0000223

10. Roberts ID, Krajbich I, Cheavens JS, Campo JV, Way BM. Acetaminophen Reduces Distrust in Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder Features. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):145-154. doi:10.1177/2167702617731374

11. Dewall CN, Macdonald G, Webster GD, et al. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(7):931-937. doi:10.1177/0956797610374741

12. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics. Updated June 2021. Accessed November 2, 202November 10, 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

13. Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, Luebbert RA. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2005;53(11):1921-9. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53572.x

1. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Substance use and military life drug facts. Published October 2019. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/substance-use-military-life

2. National Veterans Foundation. What statistics show about veteran substance abuse and why proper treatment is important. Published March 30, 2016. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://nvf.org/veteran-substance-abuse-statistics

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Korsakoff syndrome. Updated July 10, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539854

4. Gerridzen IJ, Goossensen MA. Patients with Korsakoff syndrome in nursing homes: characteristics, comorbidity, and use of psychotropic drugs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):115-121. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001543

5. Press D, Alexander M. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Updated October 2021. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-neuropsychiatric-symptoms-of-dementia

6. Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG. Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: Managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):900-906. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030342

7. Jibson MD. Second-generation antipsychotic medications: pharmacology, administration, and side effects. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/second-generation-antipsychotic-medications-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

8. Husebo BS, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen OB, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4065. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4065

9. Fung K, Alden LE. Once hurt, twice shy: social pain contributes to social anxiety. Emotion. 2017;(2):231-239. doi:10.1037/emo0000223

10. Roberts ID, Krajbich I, Cheavens JS, Campo JV, Way BM. Acetaminophen Reduces Distrust in Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder Features. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):145-154. doi:10.1177/2167702617731374

11. Dewall CN, Macdonald G, Webster GD, et al. Acetaminophen reduces social pain: behavioral and neural evidence. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(7):931-937. doi:10.1177/0956797610374741

12. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics. Updated June 2021. Accessed November 2, 202November 10, 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

13. Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Harman B, Luebbert RA. Effect of acetaminophen on behavior, well-being, and psychotropic medication use in nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2005;53(11):1921-9. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53572.x