User login

Trichoepithelioma and Spiradenoma Collision Tumor

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

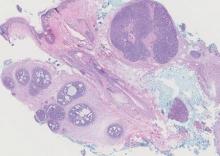

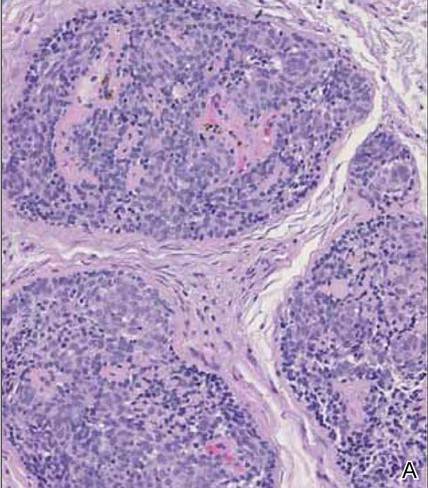

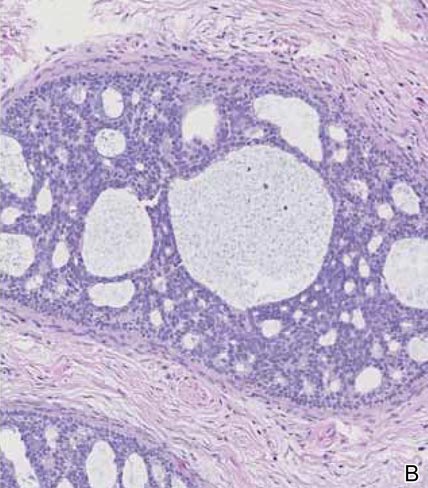

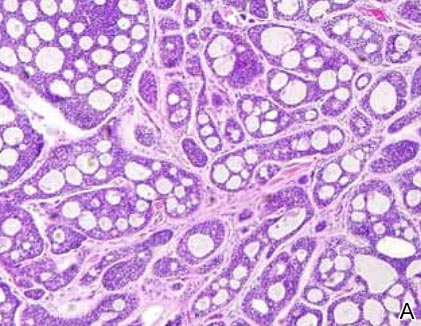

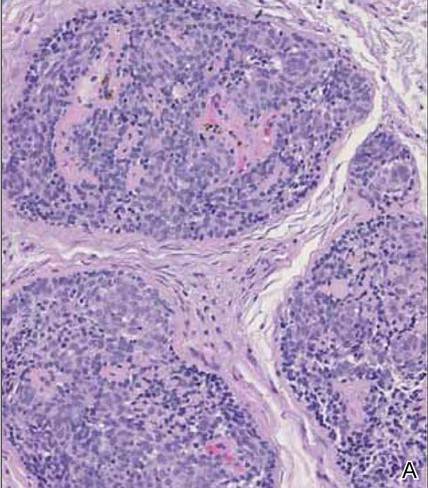

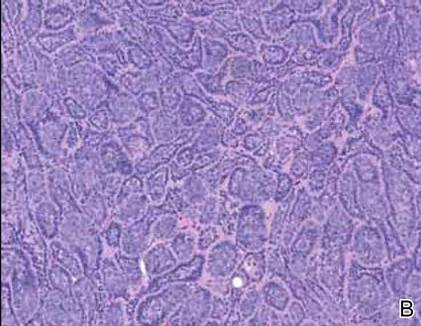

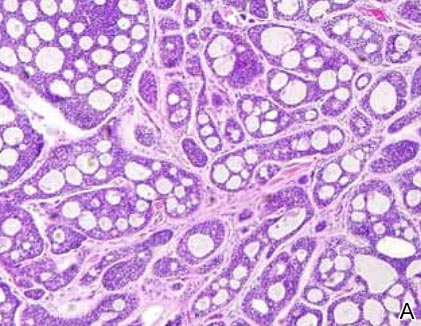

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

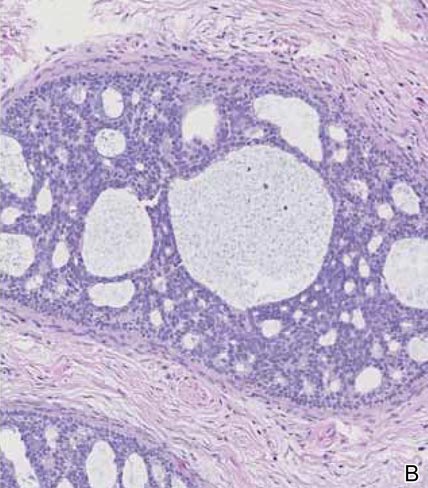

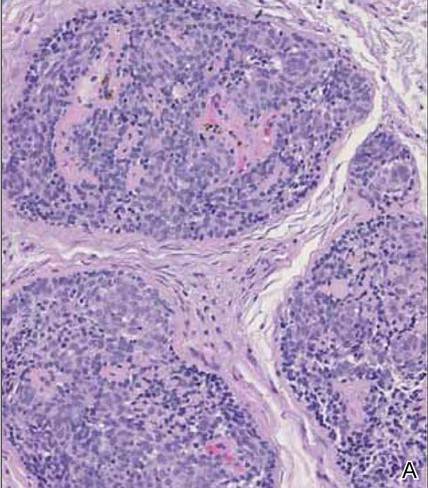

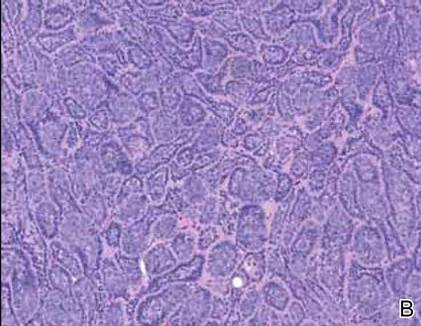

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

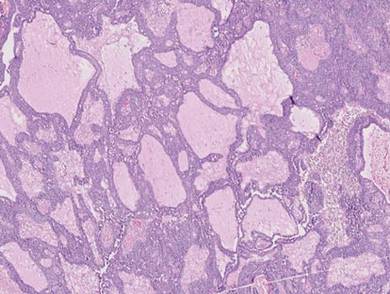

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

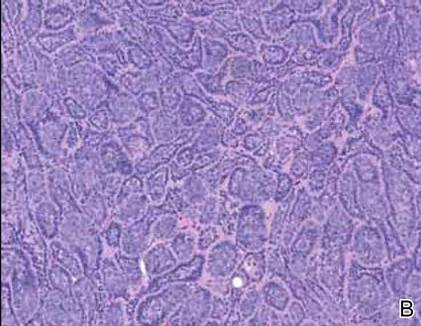

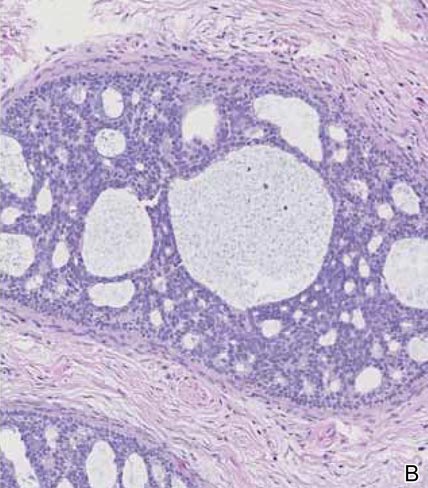

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

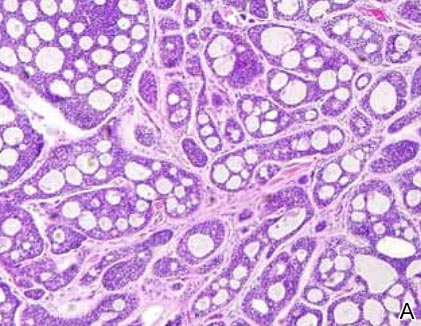

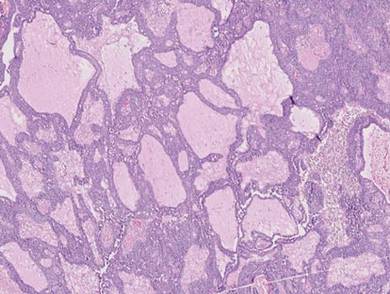

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

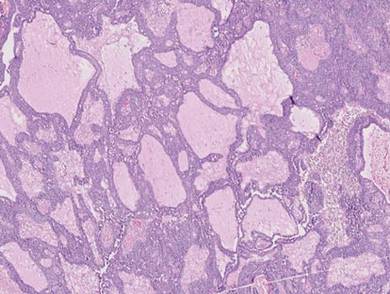

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

The coexistence of more than one cutaneous adnexal neoplasm in a single biopsy specimen is unusual and is most frequently recognized in the context of a nevus sebaceous or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, an autosomal-dominant inherited disease characterized by cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, most commonly cylindromas and trichoepitheliomas.1-3 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD, located on band 16q12; it functions as a tumor suppressor gene and has regulatory roles in development, immunity, and inflammation.1 Weyers et al3 first recognized the tendency for adnexal collision tumors to present in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome; they reported a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome with spiradenomas found in the immediate vicinity of trichoepitheliomas and in continuity with hair follicles.

Spiradenomas are composed of large, sharply demarcated, rounded nodules of basaloid cells with little cytoplasm (Figure 1).4 The basaloid nodules may demonstrate a trabecular architecture, and on close inspection 2 cell types—paler cells with more cytoplasm and darker cells with less cytoplasm—are distinguishable (Figure 2A). Lymphocytes often are scattered within the tumor nodules and/or stroma. In Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, collision tumors containing a spiradenomatous component in collision with trichoepithelioma are not uncommon.1 Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome have been reported to contain sebaceous differentiation or foci with an adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC)–like pattern and are known to occur as hybrid lesions of spiradenoma and cylindroma or trichoepithelioma (as in this case).

In this case, 2 distinct neoplasms (spiradenoma and trichoepithelioma) are apparent, side by side, with an intervening hair follicle (Figure 1). Trichoepitheliomas, also known as cribriform trichoblastomas,5 are characterized by lobules of basaloid cells resembling basal cell carcinoma surrounded by a fibroblast-rich stroma. They often contain fingerlike projections and adopt a cribriform morphology within the tumor lobules (Figure 2B).4 Numerous horn cysts may be present, but their absence does not preclude the diagnosis. Mucin may be present within the cribriform tumor islands (Figure 2B) but not in the stroma. Characteristically, trichoepitheliomas are distinctly negative for CK7 (Figure 3), and unlike spiradenomas, they lack a myoepithelial component.6 This staining pattern in combination with the tumor’s proximity to an adjacent hair follicle makes a diagnosis of trichoepithelioma and spiradenoma collision tumor most likely and supports a clinical suspicion for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.

|

Although spiradenomas sometimes contain cystic cavities (microcystic change), they typically are filled with finely granular eosinophilic material, not mucin, that is diastase resistant and periodic acid–Schiff positive (Figure 4).7 Spiradenomas classically stain positive with CK7 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen, and have a substantial myoepithelial component, as evidenced by the myoepithelial component staining with p63, S-100, and smooth muscle actin (SMA).7-9 The distinct lack of staining with CK7 and SMA in the tumor on the left in Figure 3 confirms that these tumors are of different lineage, rather than representing cystic change within a spiradenoma.

|

|

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that may occur in a primary cutaneous form, as a direct extension from an underlying salivary gland neoplasm, or rarely as a focal pattern within spiradenomas occurring both sporadically or in the context of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.2,7 The tumor is composed of variably sized cribriform islands of basaloid to pink cells concentrically arranged around glandlike spaces filled with mucin (Figure 5A). In contrast to trichoepithelioma, ACC occurs in the mid to deep dermis, often extending into subcutaneous fat with an infiltrative border, and is not often found in close proximity to hair follicles.7 Characteristically, hyaline basement membrane–like material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive is found between the tumor cells and also surrounding the individual lobules. Immunohistochemically, ACC has a myoepithelial component that stains positive with SMA, S-100, and p63; additionally, the tumor cells express low- and high-molecular-weight keratin and demonstrate variable epithelial membrane antigen positivity.10 In the current case, the superficial location, close association with a hair follicle, and lack of staining with both CK7 (Figure 3) and SMA (not shown) make ACC arising within a spiradenoma a less likely diagnosis.

Cylindromas are composed of basaloid islands interconnected in a jigsaw puzzle configuration (Figure 5B).4 Similar to spiradenomas, they also are composed of 2 cell populations. Characteristically, the tumor islands are outlined by a hyalinized eosinophilic basement membrane. Hyalinized droplets of basement membrane zone material also may be noted in the islands. Unlike spiradenomas, they lack both intratumoral lymphocytes and a trabecular growth pattern. Although spiradenocylindromas (cylindroma and spiradenoma collision tumors) are perhaps the most common collision tumor associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, there is no evidence suggesting the presence of a cylindroma in the current case.

|

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare neoplasm with a predilection for the eyelids; lesions occurring outside of this facial distribution, particularly of the breast, warrant a workup for metastatic disease.7 It typically occurs in the deeper dermis with involvement of the subcutaneous fat and is characterized by delicate fibrous septa enveloping large lakes of mucin, which contain islands of tumor cells (Figure 6). It has not been reported in association with spiradenomas. In addition, the tumor cells typically are CK7 positive.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

1. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

2. Petersson F, Kutzner H, Spagnolo DV, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma-like pattern in spiradenoma and spiradenocylindroma: a rare feature in sporadic neoplasms and those associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:642-648.

3. Weyers W, Nilles M, Eckert F, et al. Spiradenomas in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:156-161.

4. Elston DM, Ferringer T. Dermatopathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Saunders; 2009.

5. Ackerman AB, de Viragh PA, Chongchitnant N. Neoplasms with Follicular Differentiation. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1993.

6. Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8-16.

7. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

8. Meybehm M, Fischer HP. Spiradenoma and dermal cylindroma: comparative immunohistochemical analysis and histogenetic considerations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:154-161.

9. Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Tarumi C, et al. Eccrinespiradenoma: co-expression of cytokeratin and smooth muscle actin suggesting differentiation toward myoepithelial cells. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:121-123.

10. Thompson LD, Penner C, Ho NJ, et al. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal adenoid cystic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 86 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:88-109.

Challenges Facing Our Specialty

The health care environment is changing rapidly and the smart dermatologist will stay informed and respond proactively. Our strength lies in our unity and identity as dermatologists. There is strength in numbers, and for us to thrive, all dermatologists should be members of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the American Medical Association. These memberships ensure that we have a seat at the table when important decisions are being made. If you have let your membership lapse, I strongly encourage you to join. Our representation as a specialty depends on the number of members we have in each of these societies. The AAD provides many ways to stay informed, including member-to-member communications, Dermatology World, and special communications from the AAD president. Member alerts will let you know when critical action is required to affect pending legislation that impacts our specialty. Stay informed and respond when called upon.

Dermatologists face unprecedented challenges that pose a very real threat to patient access to high-quality care by a board-certified dermatologist and the future of private practice, including limited provider networks, challenges to fair reimbursement, and bad audit policies. Limited provider networks may represent the single greatest threat to the independent practice of medicine in the United States. Recent actions by payors have unenrolled large numbers of providers. In some cases, dermatologists have found that 20% of their patients became “out of network” overnight. Higher patient co-pays and difficulty with reimbursement may follow, limiting a patient’s ability to continue to see his/her physician. Challenges to fair reimbursement abound and tiered payments are becoming commonplace, with the criteria for tiering often driven by economics rather than quality. Medical necessity auditors have inappropriately used the ABCD public education tool for melanoma, applying it to medical records and ruling biopsies positive for melanoma as “not medically necessary” because the ABCDs were not documented in the physician’s note. In other cases, biopsies positive for skin cancer were ruled “not medically necessary” because of “lack of documentation of signs and symptoms.” Melanomas rarely itch, and the ABCD tool was designed for laypeople. Ignorance and lack of understanding of the care we provide jeopardizes patient access to care.

Even bigger challenges loom. Where will dermatology fit into the big picture as national health care priorities focus on large public health issues such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and depression? Dermatologists play a critical role in reducing the burden of skin cancer, preventing both death and morbidity, but most policymakers do not understand the critical services we provide. Individual physicians have a limited ability to respond to these challenges, and our state and subspecialty societies have limited resources to fight these battles. Over the last 2 years, the AAD has responded by transforming a good state affairs office into a superbly effective and nimble group of highly talented individuals with expertise in advocacy, law, and health policy. Our new Strategic Alliance Liaison Committee is designed to coordinate the efforts of patient advocacy groups and dermatology societies to help ensure an effective response. If your state or subspecialty society is not actively engaged with the AAD’s state affairs office, it is time to contact them.

It is critical that dermatologists project a unified voice. Dermatology is a small specialty, representing less than 2% of physicians, but we have always been successful in projecting a voice much larger than our numbers. Unity is key to our success. This past year, the AAD established a rapid response checklist to ensure that all critical steps fall into place when responding to a rapidly evolving critical issue, including coordination with key patient advocacy groups and other key dermatological societies such as the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Mohs College, Mohs Society, American Society of Dermatopathology, the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology, and many others. There are many payment and scope of practice issues that are difficult for us to present without appearing self-serving, but these very same messages can succeed when the focus is on patient safety, quality of care, and patient access. Patient advocacy groups are our best allies because they fight for patient rights to timely and effective care for diseases of the skin.

Change is occurring quickly and there is a lot of work to be done. Key priorities fundamental to the future of our specialty include ensuring effective advocacy, establishing how dermatologists fit into new payment and care delivery models, obtaining the data we need to demonstrate the unique value dermatologists bring to patient care and the health care system, enhancing the image of our specialty, and optimizing our support of state and local dermatological societies as they confront a growing range of issues.

We are privileged to practice a specialty that can provide patients with dramatic improvements in health and quality of life. We give back in so many ways, such as volunteering to help underserved populations overseas or at home. We have raised public awareness of the threat of melanoma. The Canadian Dermatology Association turned Niagara Falls orange on Melanoma Monday this year to raise skin cancer awareness; well done! Every one of us who helps support our patient advocacy efforts or the continued success of Camp Discovery (http://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/for-kids/camp-discovery) enhances the image of our specialty. Each time you see a hospital consultation, volunteer in the community, or squeeze in a patient who cannot pay at the end of a long day, you do more than help an individual; you help ensure the very future of our specialty.

To face the challenges ahead, we must stick together and project a unified voice. Stay informed! If you do not regularly read Dermatology World and the AAD’s member-to-member alerts, you are missing a lot. Our future depends on each one of us working together for our patients and our specialty.

The health care environment is changing rapidly and the smart dermatologist will stay informed and respond proactively. Our strength lies in our unity and identity as dermatologists. There is strength in numbers, and for us to thrive, all dermatologists should be members of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the American Medical Association. These memberships ensure that we have a seat at the table when important decisions are being made. If you have let your membership lapse, I strongly encourage you to join. Our representation as a specialty depends on the number of members we have in each of these societies. The AAD provides many ways to stay informed, including member-to-member communications, Dermatology World, and special communications from the AAD president. Member alerts will let you know when critical action is required to affect pending legislation that impacts our specialty. Stay informed and respond when called upon.

Dermatologists face unprecedented challenges that pose a very real threat to patient access to high-quality care by a board-certified dermatologist and the future of private practice, including limited provider networks, challenges to fair reimbursement, and bad audit policies. Limited provider networks may represent the single greatest threat to the independent practice of medicine in the United States. Recent actions by payors have unenrolled large numbers of providers. In some cases, dermatologists have found that 20% of their patients became “out of network” overnight. Higher patient co-pays and difficulty with reimbursement may follow, limiting a patient’s ability to continue to see his/her physician. Challenges to fair reimbursement abound and tiered payments are becoming commonplace, with the criteria for tiering often driven by economics rather than quality. Medical necessity auditors have inappropriately used the ABCD public education tool for melanoma, applying it to medical records and ruling biopsies positive for melanoma as “not medically necessary” because the ABCDs were not documented in the physician’s note. In other cases, biopsies positive for skin cancer were ruled “not medically necessary” because of “lack of documentation of signs and symptoms.” Melanomas rarely itch, and the ABCD tool was designed for laypeople. Ignorance and lack of understanding of the care we provide jeopardizes patient access to care.

Even bigger challenges loom. Where will dermatology fit into the big picture as national health care priorities focus on large public health issues such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and depression? Dermatologists play a critical role in reducing the burden of skin cancer, preventing both death and morbidity, but most policymakers do not understand the critical services we provide. Individual physicians have a limited ability to respond to these challenges, and our state and subspecialty societies have limited resources to fight these battles. Over the last 2 years, the AAD has responded by transforming a good state affairs office into a superbly effective and nimble group of highly talented individuals with expertise in advocacy, law, and health policy. Our new Strategic Alliance Liaison Committee is designed to coordinate the efforts of patient advocacy groups and dermatology societies to help ensure an effective response. If your state or subspecialty society is not actively engaged with the AAD’s state affairs office, it is time to contact them.

It is critical that dermatologists project a unified voice. Dermatology is a small specialty, representing less than 2% of physicians, but we have always been successful in projecting a voice much larger than our numbers. Unity is key to our success. This past year, the AAD established a rapid response checklist to ensure that all critical steps fall into place when responding to a rapidly evolving critical issue, including coordination with key patient advocacy groups and other key dermatological societies such as the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Mohs College, Mohs Society, American Society of Dermatopathology, the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology, and many others. There are many payment and scope of practice issues that are difficult for us to present without appearing self-serving, but these very same messages can succeed when the focus is on patient safety, quality of care, and patient access. Patient advocacy groups are our best allies because they fight for patient rights to timely and effective care for diseases of the skin.

Change is occurring quickly and there is a lot of work to be done. Key priorities fundamental to the future of our specialty include ensuring effective advocacy, establishing how dermatologists fit into new payment and care delivery models, obtaining the data we need to demonstrate the unique value dermatologists bring to patient care and the health care system, enhancing the image of our specialty, and optimizing our support of state and local dermatological societies as they confront a growing range of issues.

We are privileged to practice a specialty that can provide patients with dramatic improvements in health and quality of life. We give back in so many ways, such as volunteering to help underserved populations overseas or at home. We have raised public awareness of the threat of melanoma. The Canadian Dermatology Association turned Niagara Falls orange on Melanoma Monday this year to raise skin cancer awareness; well done! Every one of us who helps support our patient advocacy efforts or the continued success of Camp Discovery (http://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/for-kids/camp-discovery) enhances the image of our specialty. Each time you see a hospital consultation, volunteer in the community, or squeeze in a patient who cannot pay at the end of a long day, you do more than help an individual; you help ensure the very future of our specialty.

To face the challenges ahead, we must stick together and project a unified voice. Stay informed! If you do not regularly read Dermatology World and the AAD’s member-to-member alerts, you are missing a lot. Our future depends on each one of us working together for our patients and our specialty.

The health care environment is changing rapidly and the smart dermatologist will stay informed and respond proactively. Our strength lies in our unity and identity as dermatologists. There is strength in numbers, and for us to thrive, all dermatologists should be members of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the American Medical Association. These memberships ensure that we have a seat at the table when important decisions are being made. If you have let your membership lapse, I strongly encourage you to join. Our representation as a specialty depends on the number of members we have in each of these societies. The AAD provides many ways to stay informed, including member-to-member communications, Dermatology World, and special communications from the AAD president. Member alerts will let you know when critical action is required to affect pending legislation that impacts our specialty. Stay informed and respond when called upon.

Dermatologists face unprecedented challenges that pose a very real threat to patient access to high-quality care by a board-certified dermatologist and the future of private practice, including limited provider networks, challenges to fair reimbursement, and bad audit policies. Limited provider networks may represent the single greatest threat to the independent practice of medicine in the United States. Recent actions by payors have unenrolled large numbers of providers. In some cases, dermatologists have found that 20% of their patients became “out of network” overnight. Higher patient co-pays and difficulty with reimbursement may follow, limiting a patient’s ability to continue to see his/her physician. Challenges to fair reimbursement abound and tiered payments are becoming commonplace, with the criteria for tiering often driven by economics rather than quality. Medical necessity auditors have inappropriately used the ABCD public education tool for melanoma, applying it to medical records and ruling biopsies positive for melanoma as “not medically necessary” because the ABCDs were not documented in the physician’s note. In other cases, biopsies positive for skin cancer were ruled “not medically necessary” because of “lack of documentation of signs and symptoms.” Melanomas rarely itch, and the ABCD tool was designed for laypeople. Ignorance and lack of understanding of the care we provide jeopardizes patient access to care.

Even bigger challenges loom. Where will dermatology fit into the big picture as national health care priorities focus on large public health issues such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and depression? Dermatologists play a critical role in reducing the burden of skin cancer, preventing both death and morbidity, but most policymakers do not understand the critical services we provide. Individual physicians have a limited ability to respond to these challenges, and our state and subspecialty societies have limited resources to fight these battles. Over the last 2 years, the AAD has responded by transforming a good state affairs office into a superbly effective and nimble group of highly talented individuals with expertise in advocacy, law, and health policy. Our new Strategic Alliance Liaison Committee is designed to coordinate the efforts of patient advocacy groups and dermatology societies to help ensure an effective response. If your state or subspecialty society is not actively engaged with the AAD’s state affairs office, it is time to contact them.

It is critical that dermatologists project a unified voice. Dermatology is a small specialty, representing less than 2% of physicians, but we have always been successful in projecting a voice much larger than our numbers. Unity is key to our success. This past year, the AAD established a rapid response checklist to ensure that all critical steps fall into place when responding to a rapidly evolving critical issue, including coordination with key patient advocacy groups and other key dermatological societies such as the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, the Mohs College, Mohs Society, American Society of Dermatopathology, the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology, and many others. There are many payment and scope of practice issues that are difficult for us to present without appearing self-serving, but these very same messages can succeed when the focus is on patient safety, quality of care, and patient access. Patient advocacy groups are our best allies because they fight for patient rights to timely and effective care for diseases of the skin.

Change is occurring quickly and there is a lot of work to be done. Key priorities fundamental to the future of our specialty include ensuring effective advocacy, establishing how dermatologists fit into new payment and care delivery models, obtaining the data we need to demonstrate the unique value dermatologists bring to patient care and the health care system, enhancing the image of our specialty, and optimizing our support of state and local dermatological societies as they confront a growing range of issues.

We are privileged to practice a specialty that can provide patients with dramatic improvements in health and quality of life. We give back in so many ways, such as volunteering to help underserved populations overseas or at home. We have raised public awareness of the threat of melanoma. The Canadian Dermatology Association turned Niagara Falls orange on Melanoma Monday this year to raise skin cancer awareness; well done! Every one of us who helps support our patient advocacy efforts or the continued success of Camp Discovery (http://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/for-kids/camp-discovery) enhances the image of our specialty. Each time you see a hospital consultation, volunteer in the community, or squeeze in a patient who cannot pay at the end of a long day, you do more than help an individual; you help ensure the very future of our specialty.

To face the challenges ahead, we must stick together and project a unified voice. Stay informed! If you do not regularly read Dermatology World and the AAD’s member-to-member alerts, you are missing a lot. Our future depends on each one of us working together for our patients and our specialty.