User login

Vaping: The new wave of nicotine addiction

Electronic cigarettes and other “vaping” devices have been increasing in popularity among youth and adults since their introduction in the US market in 2007.1 This increase is partially driven by a public perception that vaping is harmless, or at least less harmful than cigarette smoking.2 Vaping fans also argue that current smokers can use vaping as nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit smoking.3

We disagree. Research on the health effects of vaping, though still limited, is accumulating rapidly and making it increasingly clear that this habit is far from harmless. For youth, it is a gateway to addiction to nicotine and other substances. Whether it can help people quit smoking remains to be seen. And recent months have seen reports of serious respiratory illnesses and even deaths linked to vaping.4

In December 2016, the US Surgeon General warned that e-cigarette use among youth and young adults in the United States represents a “major public health concern,”5 and that more adolescents and young adults are now vaping than smoking conventional tobacco products.

This article reviews the issue of vaping in the United States, as well as available evidence regarding its safety.

YOUTH AT RISK

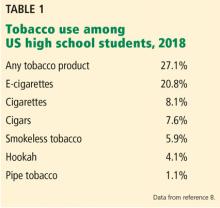

Retail sales of e-cigarettes and vaping devices approach an annual $7 billion.6 A 2014–2015 survey found that 2.4% of the general US population were current users of e-cigarettes, and 8.5% had tried them at least once.3

In 2014, for the first time, e-cigarette use became more common among US youth than traditional cigarettes.5

The odds of taking up vaping are higher among minority youth in the United States, particularly Hispanics.9 This trend is particularly worrisome because several longitudinal studies have shown that adolescents who use e-cigarettes are 3 times as likely to eventually become smokers of traditional cigarettes compared with adolescents who do not use e-cigarettes.10–12

If US youth continue smoking at the current rate, 5.6 million of the current population under age 18, or 1 of every 13, will die early of a smoking-related illness.13

RECENT OUTBREAK OF VAPING-ASSOCIATED LUNG INJURY

As of November 5, 2019, there had been 2,051 cases of vaping-associated lung injury in 49 states (all except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and 1 US territory reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with 39 confirmed deaths.4 The reported cases include respiratory injury including acute eosinophilic pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.14

Most of these patients had been vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), though many used both nicotine- and THC-containing products, and others used products containing nicotine exclusively.4 Thus, it is difficult to identify the exact substance or substances that may be contributing to this sudden outbreak among vape users, and many different product sources are currently under investigation.

One substance that may be linked to the epidemic is vitamin E acetate, which the New York State Department of Health has detected in high levels in cannabis vaping cartridges used by patients who developed lung injury.15 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is continuing to analyze vape cartridge samples submitted by affected patients to look for other chemicals that can contribute to the development of serious pulmonary illness.

WHAT IS AN E-CIGARETTE? WHAT IS A VAPE PEN?

Vape pens consist of similar elements but are not necessarily similar in appearance to a conventional cigarette, and may look more like a pen or a USB flash drive. In fact, the Juul device is recharged by plugging it into a USB port.

Vaping devices have many street names, including e-cigs, e-hookahs, vape pens, mods, vapes, and tank systems.

The first US patent application for a device resembling a modern e-cigarette was filed in 1963, but the product never made it to the market.16 Instead, the first commercially successful e-cigarette was created in Beijing in 2003 and introduced to US markets in 2007.

Newer-generation devices have larger batteries and can heat the liquid to higher temperatures, releasing more nicotine and forming additional toxicants such as formaldehyde. Devices lack standardization in terms of design, capacity for safely holding e-liquid, packaging of the e-liquid, and features designed to minimize hazards of use.

Not just nicotine

Many devices are designed for use with other drugs, including THC.17 In a 2018 study, 10.9% of college students reported vaping marijuana in the past 30 days, up from 5.2% in 2017.18

Other substances are being vaped as well.19 In theory, any heat-stable psychoactive recreational drug could be aerosolized and vaped. There are increasing reports of e-liquids containing recreational drugs such as synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, crack cocaine, LSD, and methamphetamine.17

Freedom, rebellion, glamour

Sales have risen rapidly since 2007 with widespread advertising on television and in print publications for popular brands, often featuring celebrities.20 Spending on advertising for e-cigarettes and vape devices rose from $6.4 million in 2011 to $115 million in 2014—and that was before the advent of Juul (see below).21

Marketing campaigns for vaping devices mimic the themes previously used successfully by the tobacco industry, eg, freedom, rebellion, and glamour. They also make unsubstantiated claims about health benefits and smoking cessation, though initial websites contained endorsements from physicians, similar to the strategies of tobacco companies in old cigarette ads. Cigarette ads have been prohibited since 1971—but not e-cigarette ads. Moreover, vaping products appear as product placements in television shows and movies, with advocacy groups on social media.22

By law, buyers have to be 18 or 21

Vaping devices can be purchased at vape shops, convenience stores, gas stations, and over the Internet; up to 50% of sales are conducted online.24

Fruit flavors are popular

Zhu et al25 estimated that 7,700 unique vaping flavors exist, with fruit and candy flavors predominating. The most popular flavors are tobacco and mint, followed by fruit, dessert and candy flavors, alcoholic flavors (strawberry daiquiri, margarita), and food flavors.25 These flavors have been associated with higher usage in youth, leading to increased risk of nicotine addiction.26

WHAT IS JUUL?

The Juul device (Juul Labs, www.juul.com) was developed in 2015 by 2 Stanford University graduates. Their goal was to produce a more satisfying and cigarette-like vaping experience, specifically by increasing the amount of nicotine delivered while maintaining smooth and pleasant inhalation. They created an e-liquid that could be vaporized effectively at lower temperatures.27

While more than 400 brands of vaping devices are currently available in the United States,3 Juul has held the largest market share since 2017,28 an estimated 72.1% as of August 2018.29 The surge in popularity of this particular brand is attributed to its trendy design that is similar in size and appearance to a USB flash drive,29 and its offering of sweet flavors such as “crème brûlée” and “cool mint.”

On April 24, 2018, in view of growing concern about the popularity of Juul products among youth, the FDA requested that the company submit documents regarding its marketing tactics, as well as research on the effects of this marketing on product design and public health impact, and information about adverse experiences and complaints.30 The company was forced to change its marketing to appeal less to youth. Now it offers only 3 flavors: “Virginia tobacco,” “classic tobacco,” and “menthol,” although off-brand pods containing a variety of flavors are still available. And some pods are refillable, so users can essentially vape any substance they want.

Although the Juul device delivers a strong dose of nicotine, it is small and therefore easy to hide from parents and teachers, and widespread use has been reported among youth in middle and high schools. Hoodies, hemp jewelry, and backpacks have been designed to hide the devices and allow for easy, hands-free use. YouTube searches for terms such as “Juul,” “hiding Juul at school,” and “Juul in class,” yield thousands of results.31 A 2017 survey reported that 8% of Americans age 15 to 24 had used Juul in the month prior to the survey.32 “To juul” has become a verb.

Each Juul starter kit contains the rechargeable inhalation device plus 4 flavored pods. In the United States, each Juul pod contains nearly as much nicotine as 1 pack of 20 cigarettes in a concentration of 3% or 5%. (Israel and Europe have forced the company to replace the 5% nicotine pods with 1.7% nicotine pods.33) A starter kit costs $49.99, and additional packs of 4 flavored liquid cartridges or pods cost $15.99.34 Other brands of vape pens cost between $15 and $35, and 10-mL bottles of e-liquid cost approximately $7.

What is ‘dripping’?

Hard-core vapers seeking a more intense experience are taking their vaping devices apart and modifying them for “dripping,” ie, directly dripping vape liquids onto the heated coils for inhalation. In a survey, 1 in 4 high school students using vape devices also used them for dripping, citing desires for a thicker cloud of vapor, more intense flavor, “a stronger throat hit,” curiosity, and other reasons.35 Dripping involves higher temperatures, which leads to higher amounts of nicotine delivered, along with more formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone (see below).36

BAD THINGS IN E-LIQUID AEROSOL

Studies of vape liquids consistently confirm the presence of toxic substances in the resulting vape aerosol.37–40 Depending on the combination of flavorings and solvents in a given e-liquid, a variety of chemicals can be detected in the aerosol from various vaping devices. Chemicals that may be detected include known irritants of respiratory mucosa, as well as various carcinogens. The list includes:

- Organic volatile compounds such as propylene glycol, glycerin, and toluene

- Aldehydes such as formaldehyde (released when propylene glycol is heated to high temperatures), acetaldehyde, and benzaldehyde

- Acetone and acrolein

- Carcinogenic nitrosamines

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- Particulate matter

- Metals including chromium, cadmium, nickel, and lead; and particles of copper, nickel, and silver have been found in electronic nicotine delivery system aerosol in higher levels than in conventional cigarette smoke.41

The specific chemicals detected can vary greatly between brands, even when the flavoring and nicotine content are equivalent, which frequently results in inconsistent and conflicting study findings. The chemicals detected also vary with the voltage or power used to generate the aerosol. Different flavors may carry varying levels of risk; for example, mint- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes were shown to expose users to dangerous levels of pulegone, a carcinogenic compound banned as a food additive in 2018.42 The concentrations of some of these chemicals are sufficiently high to be of toxicologic concern; for example, one study reported the presence of benzaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosol at twice the workplace exposure limit.43

Biologic effects

In an in vitro study,44 57% of e-liquids studied were found to be cytotoxic to human pulmonary fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells, and human embryonic stem cells. Fruit-flavored e-liquids in particular caused a significant increase in DNA fragmentation. Cell cultures treated with e-cigarette liquids showed increased oxidative stress, reduced cell proliferation, and increased DNA damage,44 which may have implications for carcinogenic risk.

In another study,45 exposure to e-cigarette aerosol as well as conventional cigarette smoke resulted in suppression of genes related to immune and inflammatory response in respiratory epithelial cells. All genes with decreased expression after exposure to conventional cigarette smoke also showed decreased expression with exposure to e-cigarette smoke, which the study authors suggested could lead to immune suppression at the level of the nasal mucosa. Diacetyl and acetoin, chemicals found in certain flavorings, have been linked to bronchiolitis obliterans, or “popcorn lung.”46

Nicotine is not benign

The nicotine itself in many vaping liquids should also not be underestimated. Nicotine has harmful neurocognitive effects and addictive properties, particularly in the developing brains of adolescents and young adults.47 Nicotine exposure during adolescence negatively affects memory, attention, and emotional regulation,48 as well as executive functioning, reward processing, and learning.49

The brain undergoes major structural remodeling in adolescence, and nicotine acetylcholine receptors regulate neural maturation. Early exposure to nicotine disrupts this process, leading to poor executive functioning, difficulty learning, decreased memory, and issues with reward processing.

Fetal exposure, if nicotine products are used during pregnancy, has also been linked to adverse consequences such as deficits in attention and cognition, behavioral effects, and sudden infant death syndrome.5

Much to learn about toxicity

Partly because vaping devices have been available to US consumers only since 2007, limited evidence is available regarding the long-term effects of exposure to the aerosol from these devices in humans.1 Many of the studies mentioned above were in vitro studies or conducted in mouse models. Differences in device design and the composition of the e-liquid among device brands pose a challenge for developing well-designed studies of the long-term health effects of e-cigarette and vape use. Additionally, devices may have different health impacts when used to vape cannabis or other drugs besides nicotine, which requires further investigation.

E-CIGARETTES AND SMOKING CESSATION

Conventional cigarette smoking is a major public health threat, as tobacco use is responsible for 480,000 deaths annually in the United States.50

And smoking is extremely difficult to quit: as many as 80% of smokers who attempt to quit resume smoking within the first month.51 The chance of successfully quitting improves by over 50% if the individual undergoes nicotine replacement therapy, and it improves even more with counseling.50

There are currently 5 types of FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy products (gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray) to help with smoking cessation. In addition, 2 non-nicotine prescription drugs (varenicline and bupropion) have been approved for treating tobacco dependence.

Can vaping devices be added to the list of nicotine replacement therapy products? Although some manufacturers try to brand their devices as smoking cessation aids, in one study,52 one-third of e-cigarette users said they had either never used conventional cigarettes or had formerly smoked them.

Bullen et al53 randomized smokers interested in quitting to receive either e-cigarettes, nicotine patches, or placebo (nicotine-free) e-cigarettes and followed them for 6 months. Rates of tobacco cessation were less than predicted for the entire study population, resulting in insufficient power to determine the superiority of any single method, but the study authors concluded that nicotine e-cigarettes were “modestly effective” at helping smokers quit, and that abstinence rates may be similar to those with nicotine patches.53

Hajek et al54 randomized 886 smokers to e-cigarette or nicotine replacement products of their choice. After 1 year, 18% of e-cigarette users had stopped smoking, compared with 9.9% of nicotine replacement product users. However, 80% of the e-cigarette users were still using e-cigarettes after 1 year, while only 9% of nicotine replacement product users were still using nicotine replacement therapy products after 1 year.

While quitting conventional cigarette smoking altogether has widely established health benefits, little is known about the health benefits of transitioning from conventional cigarette smoking to reduced conventional cigarette smoking with concomitant use of e-cigarettes.

Campagna et al55 found no beneficial health effects in smokers who partially substituted conventional cigarettes for e-cigarettes.

Many studies found that smokers use e-cigarettes to maintain their habit instead of quitting entirely.56 It has been suggested that any slight increase in effectiveness in smoking cessation by using e-cigarettes compared with other nicotine replacement products could be linked to satisfying of the habitual smoking actions, such as inhaling and bringing the hand to the mouth,24 which are absent when using other nicotine replacement methods such as a nicotine patch.

As with safety information, long-term outcomes regarding the use of vape devices for smoking cessation have not been yet established, as this option is still relatively new.

VAPING AS A GATEWAY DRUG

Another worrisome trend involving electronic nicotine delivery systems is their marketing and branding, which appear to be aimed directly at adolescents and young adults. Juul and other similar products cannot be sold to anyone under the age of 18 (or 21 in 18 states, including California, Massachusetts, New York, and now Ohio). Despite this, Juul and similar products continue to increase in popularity among middle school and high school students.57

While smoking cessation and health improvement are cited as reasons for vaping among middle-aged and older adults, adolescents and young adults more often cite flavor, enjoyment, peer use, and curiosity as reasons for use.

Adolescents are more likely to report interest in trying a vape product flavored with menthol or fruit than tobacco, and commonly hold the belief that fruit-flavored e-cigarettes are less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes.58 Harrell et al59 polled youth and young adults who used flavored e-cigarettes, and 78% said they would no longer use the product if their preferred flavor were not available. In September 2019, Michigan became the first state to ban the sale of flavored e-cigarettes in stores and online. Similar bills have been introduced in California, Massachusetts, and New York.60

Myths and misperceptions abound among youth regarding smoking vs vaping. Young people view regular cigarette smoking negatively, as causing cancer, bad breath, and asthma exacerbations. Meanwhile, they believe marijuana is safer and less addictive than traditional cigarette smoking.61 Youth exposed to e-cigarette advertisements viewed e-cigarettes as healthier, more enjoyable, “cool,” safe, and fun.61 The overall public health impact of increasing initiation of smoking, particularly among youth and young adults, should not be underestimated.

SECONDHAND VAPE AND OTHER EXPOSURE RISKS

Cigarette smoking has been banned in many public places, in view of a large body of scientific evidence about the harmful effects of secondhand smoke. Advocates for allowing vaping in public places say that vaping emissions do not harm bystanders, but evidence is insufficient to support this claim.62 One study showed that passive exposure to e-cigarette aerosol generated increases in serum levels of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) similar to those with passive exposure to conventional cigarette smoke.5

Accidental nicotine poisoning in children as a result of ingesting e-cigarette liquid is also a major concern,63 particularly with sweet flavors such as bubblegum or cheesecake that may be attractive to children.

Calls to US poison control centers with respect to e-cigarettes and vaping increased from 1 per month in September 2010 to 215 in February 2014, with 51% involving children under age 5.64 This trend resulted in the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act, which passed in 2015 and went into effect in 2016, requiring packaging that is difficult to open for children under age 5.5

Device malfunctions or battery failures have led to explosions that have resulted in substantial injuries to users, as well as house and car fires.49

HOW DO WE DISCOURAGE ADOLESCENT USE?

There are currently no established treatment approaches for adolescents who have become addicted to vaping. A review of the literature regarding treatment modalities used to address adolescent use of tobacco and marijuana provides insight that options such as nicotine replacement therapy and counseling modalities such as cognitive behavioral therapy may be helpful in treating teen vaping addiction. However, more research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these treatments in youth addicted to vaping.

Given that youth who vape even once are more likely to try other types of tobacco, we recommend that parents and healthcare providers start conversations by asking what the young person has seen or heard about vaping. Young people can also be asked what they think the school’s response should be: Do they think vaping should be banned in public places, as cigarettes have been banned? What about the carbon footprint? What are their thoughts on the plastic waste, batteries, and other toxins generated by the e-cigarette industry?

New US laws ban the sale of e-cigarettes and vaping devices to minors in stores and online. These policies are modeled in many cases on environmental control policies that have been previously employed to reduce tobacco use, particularly by youth. For example, changing laws to mandate sales only to individuals age 21 and older in all states can help to decrease access to these products among middle school and high school students.

As with tobacco cessation, education will not be enough. Support of legislation that bans vaping in public places, increases pricing to discourage adolescent use, and other measures used successfully to decrease conventional cigarette smoking can be deployed to decrease the public health impact of e-cigarettes. We recommend further regulation of specific harmful chemicals and clear, detailed ingredient labeling to increase consumer understanding of the risks associated with these products. Additionally, we recommend eliminating flavored e-cigarettes, which are the most appealing type for young users, and raising prices of e-cigarettes and similar products to discourage use by youth.

If current cigarette smokers want to use e-cigarettes to quit, we recommend that clinicians counsel them to eventually completely stop use of traditional cigarettes and switch to using e-cigarettes, instead of becoming a dual user of both types of products or using e-cigarettes indefinitely. After making that switch, they should then work to gradually taper usage and nicotine addiction by reducing the amount of nicotine in the e-liquid. Clinicians should ask patients about use of e-cigarettes and vaping devices specifically, and should counsel nonsmokers to avoid initiation of use.

EVIDENCE OF HARM CONTINUES TO EMERGE

Data about respiratory effects, secondhand exposure, and long-term smoking cessation efficacy are still limited, and it remains as yet unknown what combinations of solvents, flavorings, and nicotine in a given e-liquid will result in the most harmful or least harmful effects. In addition, while much of the information about the safety of these components has been obtained using in vitro or mouse models, increasing reports of serious respiratory illness and rising numbers of deaths linked to vaping make it clear that these findings likely translate to harmful effects in humans.

E-cigarettes may ultimately prove to be less harmful than traditional cigarettes, but it seems likely that with further time and research, serious health risks of e-cigarette use will continue to emerge.

- Sood A, Kesic M, Hernandez M. Electronic cigarettes: one size does not fit all. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141(6):1973-1982. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.029

- Romijnders K, van Osch L, de Vries H, Talhout R. Perceptions and reasons regarding e-cigarette use among users and non-users: a narrative literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15(6):1190. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061190

- Zhu S, Zhuang Y-L, Wong S, Cummins SE, Tedeschi GJ. E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys. BMJ 2017; 358:j3262. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3262

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. Updated November 5, 2019. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-Cigarettes/severe-Lung-Disease.html. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- US Public Health Services, US Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_sgr_full_report_non-508.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Thomas K, Kaplan S. E-cigarettes went unchecked in 10 years of federal inaction. New York Times Oct 14, 2019; updated November 1, 2019. www.nytimes.com/2019/10/14/health/vaping-e-cigarettes-fda.html.

- Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(45):1276–1277. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5

- Gentzke A, Creamer M, Cullen K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68(6):157–164. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1

- Hammig B, Daniel-Dobbs P, Blunt-Vinti H. Electronic cigarette initiation among minority youth in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2017; 43(3):306–310. doi:10.1080/00952990.2016.1203926

- Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among U.S. adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169(11):1018–1023. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1742

- Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 2015; 314(7):700–707. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.8950

- Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob Control 2016; 26(1):34–39. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Christiani DC. Vaping-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med 2019; Sept 6. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1912032

- Neel J, Aubrey A. Vitamin E suspected in serious lung problems among people who vaped cannabis. NPR Sept 5, 2019. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/09/05/758005409/vitamin-e-suspected-in-serious-lung-problems-among-people-who-vaped-cannabis. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- White A. Plans for the first e-cigarette went up in smoke 50 years ago. Smithsonian Magazine December 2018. www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/plans-for-first-e-cigarette-went-up-in-smoke-50-years-ago-180970730.

- Blundell MS, Dargan PI, Wood DM. The dark cloud of recreational drugs and vaping. QJM 2018; 111(3):145–148. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx049

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, Patrick ME. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018. 2018 Volume 2. College students & adults ages 19–60. www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Eggers ME, Lee YO, Jackson J, Wiley JL, Porter J, Nonnemaker JM. Youth use of electronic vapor products and blunts for administering cannabis. Addict Behav 2017; 70:79-82. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.020

- Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the “e-cigarette”in the USA. Tob Control 2013; 22(1):19–23. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-cigarette ads and youth. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/ecigarette-ads/index.html.

- Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Electronic cigarettes: a new “tobacco” industry? Tob Control 2011; 20(1):81. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.038562

- US Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the federal food, drug, and cosmetic act, as amended by the family smoking prevention and tobacco control act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Federal Register 2016; 81(90), May 10, 2016. www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-05-10/pdf/2016-10685.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Rom O, Pecorelli A, Valacchi G, Reznick AZ. Are e-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking? Ann NY Acad Sci 2015; 1340:65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609

- Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control 2014; 23(suppl 3):iii3-iii9. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670

- Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2015; 17(7):847–854. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu257

- Baca MC. How two Stanford grads aimed for big tech glory and got big tobacco instead. Updated September 4, 2019. The Washington Post September 4, 2019. www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/09/04/how-two-stanford-grads-aimed-big-tech-glory-got-big-tobacco-instead. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control 2019; 28(2):146–151. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382

- Walley SC, Wilson KM, Winickoff JP, Groner J. A public health crisis: electronic cigarettes, vape, and JUUL. Pediatrics 2019; 143(6):pii:e20182741. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2741

- Zernike K. F.D.A. cracks down on “juuling” among teenagers. The New York Times April 24, 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/04/24/health/fda-e-cigarettes-minors-juul.html. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Ramamurthi D, Chau C, Jackler RK. JUUL and other stealth vaporisers: hiding the habit from parents and teachers. Tob Control 2018 Sep 15; pii:tobaccocontrol-2018-054455. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054455. [Epub ahead of print]

- Willett JG, Bennett M, Hair EC, et al. Recognition, use and perceptions of JUUL among youth and young adults. Tob Control 2019; 28(1):115–116. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054273

- Kaplan S. Juul’s new product: less nicotine, more intense vapor. New York Times Nov 27, 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/11/27/health/juul-ecigarettes-nicotine.html.

- JUUL Labs. JUULpods. www.juul.com/shop/pods. Accessed November 14, 2019.

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean M, Kong G, et al. E-cigarettes and “dripping” among high-school youth. Pediatrics 2017; 139(3):pii:e20163224. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3224

- Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, et al. Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors: effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage. Nicotine Tob Res 2014; 16(10):1319–1326. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu078

- Rawlinson C, Martin S, Frosina J, Wright C. Chemical characterisation of aerosols emitted by electronic cigarettes using thermal desorption-gas chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2017; 1497:144–154. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.02.050

- Lee MS, LeBouf RF, Son YS, Koutrakis P, Christiani DC. Nicotine, aerosol particles, carbonyls and volatile organic compounds in tobacco- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes. Environ Health 2017; 16(1):42. doi:10.1186/s12940-017-0249-x

- Williams M, Bozhilov K, Ghai S, Talbot P. Elements including metals in the atomizer and aerosol of disposable electronic cigarettes and electronic hookahs. PLoS One 2017; 12(4):e0175430. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175430.

- Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014; 23(2):133–139. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050859

- Drope J, Cahn Z, Kennedy R, et al. Key issues surrounding the health impacts of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and other sources of nicotine. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(6):449–471. doi:10.3322/caac.21413

- Jabba SV, Jordt SE. Risk analysis for the carcinogen pulegone in mint- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products. JAMA Intern Med 2019 Sep 16 [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3649

- Tierney PA, Karpinsky CD, Brown JE, Luo W, Pankow JF. Flavour chemicals in electronic cigarette fluids. Tob Control 2016; 25(e1):e10–e15. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052175

- Behar RZ, Wang Y, Talbot P. Comparing the cytotoxicity of electronic cigarette fluids, aerosols and solvents. Tob Control 2017; 27(3):325–333. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053472

- Martin EM, Clapp PW, Rebuli ME, et al. E-cigarette use results in suppression of immune and inflammatory-response genes in nasal epithelial cells similar to cigarette smoke. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016; 311(1):L135–L144. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00170.2016

- Holden VK, Hines SE. Update on flavoring-induced lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016;22(2):158–164. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000250

- Siqueira L; Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Nicotine and tobacco as substances of abuse in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2017; 139(1):pii:e20163436. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3436

- England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA. Nicotine and the developing human: a neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. Am J Prev Med 2015; 49(2):286–293. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015

- Modesto-Lowe V, Alvarado C. E-cigs…are they cool? Talking to teens about e-cigarettes. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2017; 51(10):947–952. doi:10.1177/0009922817705188

- Prochaska JJ, Benowitz NL. The past, present, and future of nicotine addiction therapy. Annu Rev Med 2017; 67:467–486. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-111314-033712

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004; 99(1):29–38. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, Winickoff JP, Klein JD. Trends in electronic cigarette use among U.S. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17(10):119_1202. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu213

- Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 382(9905):1629–1637. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5

- Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(7):629–637. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808779

- Campagna D, Cibella F, Caponnetto P, et al. Changes in breathomics from a 1-year randomized smoking cessation trial of electronic cigarettes. Eur J Clin Invest 2016; 46(8):698–706. doi:10.1111/eci.12651

- Rehan HS, Maini J, Hungin APS. Vaping versus smoking: a quest for efficacy and safety of e-cigarette. Curr Drug Saf 2018; 13(2):92–101. doi:10.2174/1574886313666180227110556

- Zernike K. ‘I can’t stop’: schools struggle with vaping explosion. New York Times April 2, 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/04/02/health/vaping-ecigarettes-addiction-teen.html.

- Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Adolescents’ interest in trying flavoured e-cigarettes. Tob Control 2016; 25(suppl 2):ii62–ii66. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053174

- Harrell MB, Loukas A, Jackson CD, Marti CN, Perry CL. Flavored tobacco product use among youth and young adults: what if flavors didn’t exist? Tob Regul Sci 2017; 3(2):168–173. doi:10.18001/TRS.3.2.4

- Smith M. Amid vaping crackdown, Michigan to ban sale of flavored e-cigarettes. New York Times Sept 4, 2019. www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/us/michigan-vaping.html?module=inline.

- Roditis ML, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ perceptions of risks and benefits of conventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and marijuana: a qualitative analysis. J Adolesc Health 2015; 57(2):179–185. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.002

- Chapman S, Daube M, Maziak W. Should e-cigarette use be permitted in smoke-free public places? No. Tob Control 2017; 26(e1):e3–e4. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053359

- Marcham CL, Springston JP. Electronic cigarettes in the indoor environment. Rev Env Health 2019; 34(2):105–124. doi:10.1515/reveh-2019-0012

- Chatham-Stephens K, Law R, Taylor E, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: calls to poison centers for exposures to electronic cigarettes—United States, September 2010–September 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Report 2014; 63(13):292–293. pmid:24699766

Electronic cigarettes and other “vaping” devices have been increasing in popularity among youth and adults since their introduction in the US market in 2007.1 This increase is partially driven by a public perception that vaping is harmless, or at least less harmful than cigarette smoking.2 Vaping fans also argue that current smokers can use vaping as nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit smoking.3

We disagree. Research on the health effects of vaping, though still limited, is accumulating rapidly and making it increasingly clear that this habit is far from harmless. For youth, it is a gateway to addiction to nicotine and other substances. Whether it can help people quit smoking remains to be seen. And recent months have seen reports of serious respiratory illnesses and even deaths linked to vaping.4

In December 2016, the US Surgeon General warned that e-cigarette use among youth and young adults in the United States represents a “major public health concern,”5 and that more adolescents and young adults are now vaping than smoking conventional tobacco products.

This article reviews the issue of vaping in the United States, as well as available evidence regarding its safety.

YOUTH AT RISK

Retail sales of e-cigarettes and vaping devices approach an annual $7 billion.6 A 2014–2015 survey found that 2.4% of the general US population were current users of e-cigarettes, and 8.5% had tried them at least once.3

In 2014, for the first time, e-cigarette use became more common among US youth than traditional cigarettes.5

The odds of taking up vaping are higher among minority youth in the United States, particularly Hispanics.9 This trend is particularly worrisome because several longitudinal studies have shown that adolescents who use e-cigarettes are 3 times as likely to eventually become smokers of traditional cigarettes compared with adolescents who do not use e-cigarettes.10–12

If US youth continue smoking at the current rate, 5.6 million of the current population under age 18, or 1 of every 13, will die early of a smoking-related illness.13

RECENT OUTBREAK OF VAPING-ASSOCIATED LUNG INJURY

As of November 5, 2019, there had been 2,051 cases of vaping-associated lung injury in 49 states (all except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and 1 US territory reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with 39 confirmed deaths.4 The reported cases include respiratory injury including acute eosinophilic pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.14

Most of these patients had been vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), though many used both nicotine- and THC-containing products, and others used products containing nicotine exclusively.4 Thus, it is difficult to identify the exact substance or substances that may be contributing to this sudden outbreak among vape users, and many different product sources are currently under investigation.

One substance that may be linked to the epidemic is vitamin E acetate, which the New York State Department of Health has detected in high levels in cannabis vaping cartridges used by patients who developed lung injury.15 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is continuing to analyze vape cartridge samples submitted by affected patients to look for other chemicals that can contribute to the development of serious pulmonary illness.

WHAT IS AN E-CIGARETTE? WHAT IS A VAPE PEN?

Vape pens consist of similar elements but are not necessarily similar in appearance to a conventional cigarette, and may look more like a pen or a USB flash drive. In fact, the Juul device is recharged by plugging it into a USB port.

Vaping devices have many street names, including e-cigs, e-hookahs, vape pens, mods, vapes, and tank systems.

The first US patent application for a device resembling a modern e-cigarette was filed in 1963, but the product never made it to the market.16 Instead, the first commercially successful e-cigarette was created in Beijing in 2003 and introduced to US markets in 2007.

Newer-generation devices have larger batteries and can heat the liquid to higher temperatures, releasing more nicotine and forming additional toxicants such as formaldehyde. Devices lack standardization in terms of design, capacity for safely holding e-liquid, packaging of the e-liquid, and features designed to minimize hazards of use.

Not just nicotine

Many devices are designed for use with other drugs, including THC.17 In a 2018 study, 10.9% of college students reported vaping marijuana in the past 30 days, up from 5.2% in 2017.18

Other substances are being vaped as well.19 In theory, any heat-stable psychoactive recreational drug could be aerosolized and vaped. There are increasing reports of e-liquids containing recreational drugs such as synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, crack cocaine, LSD, and methamphetamine.17

Freedom, rebellion, glamour

Sales have risen rapidly since 2007 with widespread advertising on television and in print publications for popular brands, often featuring celebrities.20 Spending on advertising for e-cigarettes and vape devices rose from $6.4 million in 2011 to $115 million in 2014—and that was before the advent of Juul (see below).21

Marketing campaigns for vaping devices mimic the themes previously used successfully by the tobacco industry, eg, freedom, rebellion, and glamour. They also make unsubstantiated claims about health benefits and smoking cessation, though initial websites contained endorsements from physicians, similar to the strategies of tobacco companies in old cigarette ads. Cigarette ads have been prohibited since 1971—but not e-cigarette ads. Moreover, vaping products appear as product placements in television shows and movies, with advocacy groups on social media.22

By law, buyers have to be 18 or 21

Vaping devices can be purchased at vape shops, convenience stores, gas stations, and over the Internet; up to 50% of sales are conducted online.24

Fruit flavors are popular

Zhu et al25 estimated that 7,700 unique vaping flavors exist, with fruit and candy flavors predominating. The most popular flavors are tobacco and mint, followed by fruit, dessert and candy flavors, alcoholic flavors (strawberry daiquiri, margarita), and food flavors.25 These flavors have been associated with higher usage in youth, leading to increased risk of nicotine addiction.26

WHAT IS JUUL?

The Juul device (Juul Labs, www.juul.com) was developed in 2015 by 2 Stanford University graduates. Their goal was to produce a more satisfying and cigarette-like vaping experience, specifically by increasing the amount of nicotine delivered while maintaining smooth and pleasant inhalation. They created an e-liquid that could be vaporized effectively at lower temperatures.27

While more than 400 brands of vaping devices are currently available in the United States,3 Juul has held the largest market share since 2017,28 an estimated 72.1% as of August 2018.29 The surge in popularity of this particular brand is attributed to its trendy design that is similar in size and appearance to a USB flash drive,29 and its offering of sweet flavors such as “crème brûlée” and “cool mint.”

On April 24, 2018, in view of growing concern about the popularity of Juul products among youth, the FDA requested that the company submit documents regarding its marketing tactics, as well as research on the effects of this marketing on product design and public health impact, and information about adverse experiences and complaints.30 The company was forced to change its marketing to appeal less to youth. Now it offers only 3 flavors: “Virginia tobacco,” “classic tobacco,” and “menthol,” although off-brand pods containing a variety of flavors are still available. And some pods are refillable, so users can essentially vape any substance they want.

Although the Juul device delivers a strong dose of nicotine, it is small and therefore easy to hide from parents and teachers, and widespread use has been reported among youth in middle and high schools. Hoodies, hemp jewelry, and backpacks have been designed to hide the devices and allow for easy, hands-free use. YouTube searches for terms such as “Juul,” “hiding Juul at school,” and “Juul in class,” yield thousands of results.31 A 2017 survey reported that 8% of Americans age 15 to 24 had used Juul in the month prior to the survey.32 “To juul” has become a verb.

Each Juul starter kit contains the rechargeable inhalation device plus 4 flavored pods. In the United States, each Juul pod contains nearly as much nicotine as 1 pack of 20 cigarettes in a concentration of 3% or 5%. (Israel and Europe have forced the company to replace the 5% nicotine pods with 1.7% nicotine pods.33) A starter kit costs $49.99, and additional packs of 4 flavored liquid cartridges or pods cost $15.99.34 Other brands of vape pens cost between $15 and $35, and 10-mL bottles of e-liquid cost approximately $7.

What is ‘dripping’?

Hard-core vapers seeking a more intense experience are taking their vaping devices apart and modifying them for “dripping,” ie, directly dripping vape liquids onto the heated coils for inhalation. In a survey, 1 in 4 high school students using vape devices also used them for dripping, citing desires for a thicker cloud of vapor, more intense flavor, “a stronger throat hit,” curiosity, and other reasons.35 Dripping involves higher temperatures, which leads to higher amounts of nicotine delivered, along with more formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone (see below).36

BAD THINGS IN E-LIQUID AEROSOL

Studies of vape liquids consistently confirm the presence of toxic substances in the resulting vape aerosol.37–40 Depending on the combination of flavorings and solvents in a given e-liquid, a variety of chemicals can be detected in the aerosol from various vaping devices. Chemicals that may be detected include known irritants of respiratory mucosa, as well as various carcinogens. The list includes:

- Organic volatile compounds such as propylene glycol, glycerin, and toluene

- Aldehydes such as formaldehyde (released when propylene glycol is heated to high temperatures), acetaldehyde, and benzaldehyde

- Acetone and acrolein

- Carcinogenic nitrosamines

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- Particulate matter

- Metals including chromium, cadmium, nickel, and lead; and particles of copper, nickel, and silver have been found in electronic nicotine delivery system aerosol in higher levels than in conventional cigarette smoke.41

The specific chemicals detected can vary greatly between brands, even when the flavoring and nicotine content are equivalent, which frequently results in inconsistent and conflicting study findings. The chemicals detected also vary with the voltage or power used to generate the aerosol. Different flavors may carry varying levels of risk; for example, mint- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes were shown to expose users to dangerous levels of pulegone, a carcinogenic compound banned as a food additive in 2018.42 The concentrations of some of these chemicals are sufficiently high to be of toxicologic concern; for example, one study reported the presence of benzaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosol at twice the workplace exposure limit.43

Biologic effects

In an in vitro study,44 57% of e-liquids studied were found to be cytotoxic to human pulmonary fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells, and human embryonic stem cells. Fruit-flavored e-liquids in particular caused a significant increase in DNA fragmentation. Cell cultures treated with e-cigarette liquids showed increased oxidative stress, reduced cell proliferation, and increased DNA damage,44 which may have implications for carcinogenic risk.

In another study,45 exposure to e-cigarette aerosol as well as conventional cigarette smoke resulted in suppression of genes related to immune and inflammatory response in respiratory epithelial cells. All genes with decreased expression after exposure to conventional cigarette smoke also showed decreased expression with exposure to e-cigarette smoke, which the study authors suggested could lead to immune suppression at the level of the nasal mucosa. Diacetyl and acetoin, chemicals found in certain flavorings, have been linked to bronchiolitis obliterans, or “popcorn lung.”46

Nicotine is not benign

The nicotine itself in many vaping liquids should also not be underestimated. Nicotine has harmful neurocognitive effects and addictive properties, particularly in the developing brains of adolescents and young adults.47 Nicotine exposure during adolescence negatively affects memory, attention, and emotional regulation,48 as well as executive functioning, reward processing, and learning.49

The brain undergoes major structural remodeling in adolescence, and nicotine acetylcholine receptors regulate neural maturation. Early exposure to nicotine disrupts this process, leading to poor executive functioning, difficulty learning, decreased memory, and issues with reward processing.

Fetal exposure, if nicotine products are used during pregnancy, has also been linked to adverse consequences such as deficits in attention and cognition, behavioral effects, and sudden infant death syndrome.5

Much to learn about toxicity

Partly because vaping devices have been available to US consumers only since 2007, limited evidence is available regarding the long-term effects of exposure to the aerosol from these devices in humans.1 Many of the studies mentioned above were in vitro studies or conducted in mouse models. Differences in device design and the composition of the e-liquid among device brands pose a challenge for developing well-designed studies of the long-term health effects of e-cigarette and vape use. Additionally, devices may have different health impacts when used to vape cannabis or other drugs besides nicotine, which requires further investigation.

E-CIGARETTES AND SMOKING CESSATION

Conventional cigarette smoking is a major public health threat, as tobacco use is responsible for 480,000 deaths annually in the United States.50

And smoking is extremely difficult to quit: as many as 80% of smokers who attempt to quit resume smoking within the first month.51 The chance of successfully quitting improves by over 50% if the individual undergoes nicotine replacement therapy, and it improves even more with counseling.50

There are currently 5 types of FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy products (gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray) to help with smoking cessation. In addition, 2 non-nicotine prescription drugs (varenicline and bupropion) have been approved for treating tobacco dependence.

Can vaping devices be added to the list of nicotine replacement therapy products? Although some manufacturers try to brand their devices as smoking cessation aids, in one study,52 one-third of e-cigarette users said they had either never used conventional cigarettes or had formerly smoked them.

Bullen et al53 randomized smokers interested in quitting to receive either e-cigarettes, nicotine patches, or placebo (nicotine-free) e-cigarettes and followed them for 6 months. Rates of tobacco cessation were less than predicted for the entire study population, resulting in insufficient power to determine the superiority of any single method, but the study authors concluded that nicotine e-cigarettes were “modestly effective” at helping smokers quit, and that abstinence rates may be similar to those with nicotine patches.53

Hajek et al54 randomized 886 smokers to e-cigarette or nicotine replacement products of their choice. After 1 year, 18% of e-cigarette users had stopped smoking, compared with 9.9% of nicotine replacement product users. However, 80% of the e-cigarette users were still using e-cigarettes after 1 year, while only 9% of nicotine replacement product users were still using nicotine replacement therapy products after 1 year.

While quitting conventional cigarette smoking altogether has widely established health benefits, little is known about the health benefits of transitioning from conventional cigarette smoking to reduced conventional cigarette smoking with concomitant use of e-cigarettes.

Campagna et al55 found no beneficial health effects in smokers who partially substituted conventional cigarettes for e-cigarettes.

Many studies found that smokers use e-cigarettes to maintain their habit instead of quitting entirely.56 It has been suggested that any slight increase in effectiveness in smoking cessation by using e-cigarettes compared with other nicotine replacement products could be linked to satisfying of the habitual smoking actions, such as inhaling and bringing the hand to the mouth,24 which are absent when using other nicotine replacement methods such as a nicotine patch.

As with safety information, long-term outcomes regarding the use of vape devices for smoking cessation have not been yet established, as this option is still relatively new.

VAPING AS A GATEWAY DRUG

Another worrisome trend involving electronic nicotine delivery systems is their marketing and branding, which appear to be aimed directly at adolescents and young adults. Juul and other similar products cannot be sold to anyone under the age of 18 (or 21 in 18 states, including California, Massachusetts, New York, and now Ohio). Despite this, Juul and similar products continue to increase in popularity among middle school and high school students.57

While smoking cessation and health improvement are cited as reasons for vaping among middle-aged and older adults, adolescents and young adults more often cite flavor, enjoyment, peer use, and curiosity as reasons for use.

Adolescents are more likely to report interest in trying a vape product flavored with menthol or fruit than tobacco, and commonly hold the belief that fruit-flavored e-cigarettes are less harmful than tobacco-flavored e-cigarettes.58 Harrell et al59 polled youth and young adults who used flavored e-cigarettes, and 78% said they would no longer use the product if their preferred flavor were not available. In September 2019, Michigan became the first state to ban the sale of flavored e-cigarettes in stores and online. Similar bills have been introduced in California, Massachusetts, and New York.60

Myths and misperceptions abound among youth regarding smoking vs vaping. Young people view regular cigarette smoking negatively, as causing cancer, bad breath, and asthma exacerbations. Meanwhile, they believe marijuana is safer and less addictive than traditional cigarette smoking.61 Youth exposed to e-cigarette advertisements viewed e-cigarettes as healthier, more enjoyable, “cool,” safe, and fun.61 The overall public health impact of increasing initiation of smoking, particularly among youth and young adults, should not be underestimated.

SECONDHAND VAPE AND OTHER EXPOSURE RISKS

Cigarette smoking has been banned in many public places, in view of a large body of scientific evidence about the harmful effects of secondhand smoke. Advocates for allowing vaping in public places say that vaping emissions do not harm bystanders, but evidence is insufficient to support this claim.62 One study showed that passive exposure to e-cigarette aerosol generated increases in serum levels of cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) similar to those with passive exposure to conventional cigarette smoke.5

Accidental nicotine poisoning in children as a result of ingesting e-cigarette liquid is also a major concern,63 particularly with sweet flavors such as bubblegum or cheesecake that may be attractive to children.

Calls to US poison control centers with respect to e-cigarettes and vaping increased from 1 per month in September 2010 to 215 in February 2014, with 51% involving children under age 5.64 This trend resulted in the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act, which passed in 2015 and went into effect in 2016, requiring packaging that is difficult to open for children under age 5.5

Device malfunctions or battery failures have led to explosions that have resulted in substantial injuries to users, as well as house and car fires.49

HOW DO WE DISCOURAGE ADOLESCENT USE?

There are currently no established treatment approaches for adolescents who have become addicted to vaping. A review of the literature regarding treatment modalities used to address adolescent use of tobacco and marijuana provides insight that options such as nicotine replacement therapy and counseling modalities such as cognitive behavioral therapy may be helpful in treating teen vaping addiction. However, more research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these treatments in youth addicted to vaping.

Given that youth who vape even once are more likely to try other types of tobacco, we recommend that parents and healthcare providers start conversations by asking what the young person has seen or heard about vaping. Young people can also be asked what they think the school’s response should be: Do they think vaping should be banned in public places, as cigarettes have been banned? What about the carbon footprint? What are their thoughts on the plastic waste, batteries, and other toxins generated by the e-cigarette industry?

New US laws ban the sale of e-cigarettes and vaping devices to minors in stores and online. These policies are modeled in many cases on environmental control policies that have been previously employed to reduce tobacco use, particularly by youth. For example, changing laws to mandate sales only to individuals age 21 and older in all states can help to decrease access to these products among middle school and high school students.

As with tobacco cessation, education will not be enough. Support of legislation that bans vaping in public places, increases pricing to discourage adolescent use, and other measures used successfully to decrease conventional cigarette smoking can be deployed to decrease the public health impact of e-cigarettes. We recommend further regulation of specific harmful chemicals and clear, detailed ingredient labeling to increase consumer understanding of the risks associated with these products. Additionally, we recommend eliminating flavored e-cigarettes, which are the most appealing type for young users, and raising prices of e-cigarettes and similar products to discourage use by youth.

If current cigarette smokers want to use e-cigarettes to quit, we recommend that clinicians counsel them to eventually completely stop use of traditional cigarettes and switch to using e-cigarettes, instead of becoming a dual user of both types of products or using e-cigarettes indefinitely. After making that switch, they should then work to gradually taper usage and nicotine addiction by reducing the amount of nicotine in the e-liquid. Clinicians should ask patients about use of e-cigarettes and vaping devices specifically, and should counsel nonsmokers to avoid initiation of use.

EVIDENCE OF HARM CONTINUES TO EMERGE

Data about respiratory effects, secondhand exposure, and long-term smoking cessation efficacy are still limited, and it remains as yet unknown what combinations of solvents, flavorings, and nicotine in a given e-liquid will result in the most harmful or least harmful effects. In addition, while much of the information about the safety of these components has been obtained using in vitro or mouse models, increasing reports of serious respiratory illness and rising numbers of deaths linked to vaping make it clear that these findings likely translate to harmful effects in humans.

E-cigarettes may ultimately prove to be less harmful than traditional cigarettes, but it seems likely that with further time and research, serious health risks of e-cigarette use will continue to emerge.

Electronic cigarettes and other “vaping” devices have been increasing in popularity among youth and adults since their introduction in the US market in 2007.1 This increase is partially driven by a public perception that vaping is harmless, or at least less harmful than cigarette smoking.2 Vaping fans also argue that current smokers can use vaping as nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit smoking.3

We disagree. Research on the health effects of vaping, though still limited, is accumulating rapidly and making it increasingly clear that this habit is far from harmless. For youth, it is a gateway to addiction to nicotine and other substances. Whether it can help people quit smoking remains to be seen. And recent months have seen reports of serious respiratory illnesses and even deaths linked to vaping.4

In December 2016, the US Surgeon General warned that e-cigarette use among youth and young adults in the United States represents a “major public health concern,”5 and that more adolescents and young adults are now vaping than smoking conventional tobacco products.

This article reviews the issue of vaping in the United States, as well as available evidence regarding its safety.

YOUTH AT RISK

Retail sales of e-cigarettes and vaping devices approach an annual $7 billion.6 A 2014–2015 survey found that 2.4% of the general US population were current users of e-cigarettes, and 8.5% had tried them at least once.3

In 2014, for the first time, e-cigarette use became more common among US youth than traditional cigarettes.5

The odds of taking up vaping are higher among minority youth in the United States, particularly Hispanics.9 This trend is particularly worrisome because several longitudinal studies have shown that adolescents who use e-cigarettes are 3 times as likely to eventually become smokers of traditional cigarettes compared with adolescents who do not use e-cigarettes.10–12

If US youth continue smoking at the current rate, 5.6 million of the current population under age 18, or 1 of every 13, will die early of a smoking-related illness.13

RECENT OUTBREAK OF VAPING-ASSOCIATED LUNG INJURY

As of November 5, 2019, there had been 2,051 cases of vaping-associated lung injury in 49 states (all except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and 1 US territory reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with 39 confirmed deaths.4 The reported cases include respiratory injury including acute eosinophilic pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.14

Most of these patients had been vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), though many used both nicotine- and THC-containing products, and others used products containing nicotine exclusively.4 Thus, it is difficult to identify the exact substance or substances that may be contributing to this sudden outbreak among vape users, and many different product sources are currently under investigation.

One substance that may be linked to the epidemic is vitamin E acetate, which the New York State Department of Health has detected in high levels in cannabis vaping cartridges used by patients who developed lung injury.15 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is continuing to analyze vape cartridge samples submitted by affected patients to look for other chemicals that can contribute to the development of serious pulmonary illness.

WHAT IS AN E-CIGARETTE? WHAT IS A VAPE PEN?

Vape pens consist of similar elements but are not necessarily similar in appearance to a conventional cigarette, and may look more like a pen or a USB flash drive. In fact, the Juul device is recharged by plugging it into a USB port.

Vaping devices have many street names, including e-cigs, e-hookahs, vape pens, mods, vapes, and tank systems.

The first US patent application for a device resembling a modern e-cigarette was filed in 1963, but the product never made it to the market.16 Instead, the first commercially successful e-cigarette was created in Beijing in 2003 and introduced to US markets in 2007.

Newer-generation devices have larger batteries and can heat the liquid to higher temperatures, releasing more nicotine and forming additional toxicants such as formaldehyde. Devices lack standardization in terms of design, capacity for safely holding e-liquid, packaging of the e-liquid, and features designed to minimize hazards of use.

Not just nicotine

Many devices are designed for use with other drugs, including THC.17 In a 2018 study, 10.9% of college students reported vaping marijuana in the past 30 days, up from 5.2% in 2017.18

Other substances are being vaped as well.19 In theory, any heat-stable psychoactive recreational drug could be aerosolized and vaped. There are increasing reports of e-liquids containing recreational drugs such as synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, crack cocaine, LSD, and methamphetamine.17

Freedom, rebellion, glamour

Sales have risen rapidly since 2007 with widespread advertising on television and in print publications for popular brands, often featuring celebrities.20 Spending on advertising for e-cigarettes and vape devices rose from $6.4 million in 2011 to $115 million in 2014—and that was before the advent of Juul (see below).21

Marketing campaigns for vaping devices mimic the themes previously used successfully by the tobacco industry, eg, freedom, rebellion, and glamour. They also make unsubstantiated claims about health benefits and smoking cessation, though initial websites contained endorsements from physicians, similar to the strategies of tobacco companies in old cigarette ads. Cigarette ads have been prohibited since 1971—but not e-cigarette ads. Moreover, vaping products appear as product placements in television shows and movies, with advocacy groups on social media.22

By law, buyers have to be 18 or 21

Vaping devices can be purchased at vape shops, convenience stores, gas stations, and over the Internet; up to 50% of sales are conducted online.24

Fruit flavors are popular

Zhu et al25 estimated that 7,700 unique vaping flavors exist, with fruit and candy flavors predominating. The most popular flavors are tobacco and mint, followed by fruit, dessert and candy flavors, alcoholic flavors (strawberry daiquiri, margarita), and food flavors.25 These flavors have been associated with higher usage in youth, leading to increased risk of nicotine addiction.26

WHAT IS JUUL?

The Juul device (Juul Labs, www.juul.com) was developed in 2015 by 2 Stanford University graduates. Their goal was to produce a more satisfying and cigarette-like vaping experience, specifically by increasing the amount of nicotine delivered while maintaining smooth and pleasant inhalation. They created an e-liquid that could be vaporized effectively at lower temperatures.27

While more than 400 brands of vaping devices are currently available in the United States,3 Juul has held the largest market share since 2017,28 an estimated 72.1% as of August 2018.29 The surge in popularity of this particular brand is attributed to its trendy design that is similar in size and appearance to a USB flash drive,29 and its offering of sweet flavors such as “crème brûlée” and “cool mint.”

On April 24, 2018, in view of growing concern about the popularity of Juul products among youth, the FDA requested that the company submit documents regarding its marketing tactics, as well as research on the effects of this marketing on product design and public health impact, and information about adverse experiences and complaints.30 The company was forced to change its marketing to appeal less to youth. Now it offers only 3 flavors: “Virginia tobacco,” “classic tobacco,” and “menthol,” although off-brand pods containing a variety of flavors are still available. And some pods are refillable, so users can essentially vape any substance they want.

Although the Juul device delivers a strong dose of nicotine, it is small and therefore easy to hide from parents and teachers, and widespread use has been reported among youth in middle and high schools. Hoodies, hemp jewelry, and backpacks have been designed to hide the devices and allow for easy, hands-free use. YouTube searches for terms such as “Juul,” “hiding Juul at school,” and “Juul in class,” yield thousands of results.31 A 2017 survey reported that 8% of Americans age 15 to 24 had used Juul in the month prior to the survey.32 “To juul” has become a verb.

Each Juul starter kit contains the rechargeable inhalation device plus 4 flavored pods. In the United States, each Juul pod contains nearly as much nicotine as 1 pack of 20 cigarettes in a concentration of 3% or 5%. (Israel and Europe have forced the company to replace the 5% nicotine pods with 1.7% nicotine pods.33) A starter kit costs $49.99, and additional packs of 4 flavored liquid cartridges or pods cost $15.99.34 Other brands of vape pens cost between $15 and $35, and 10-mL bottles of e-liquid cost approximately $7.

What is ‘dripping’?

Hard-core vapers seeking a more intense experience are taking their vaping devices apart and modifying them for “dripping,” ie, directly dripping vape liquids onto the heated coils for inhalation. In a survey, 1 in 4 high school students using vape devices also used them for dripping, citing desires for a thicker cloud of vapor, more intense flavor, “a stronger throat hit,” curiosity, and other reasons.35 Dripping involves higher temperatures, which leads to higher amounts of nicotine delivered, along with more formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone (see below).36

BAD THINGS IN E-LIQUID AEROSOL

Studies of vape liquids consistently confirm the presence of toxic substances in the resulting vape aerosol.37–40 Depending on the combination of flavorings and solvents in a given e-liquid, a variety of chemicals can be detected in the aerosol from various vaping devices. Chemicals that may be detected include known irritants of respiratory mucosa, as well as various carcinogens. The list includes:

- Organic volatile compounds such as propylene glycol, glycerin, and toluene

- Aldehydes such as formaldehyde (released when propylene glycol is heated to high temperatures), acetaldehyde, and benzaldehyde

- Acetone and acrolein

- Carcinogenic nitrosamines

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- Particulate matter

- Metals including chromium, cadmium, nickel, and lead; and particles of copper, nickel, and silver have been found in electronic nicotine delivery system aerosol in higher levels than in conventional cigarette smoke.41

The specific chemicals detected can vary greatly between brands, even when the flavoring and nicotine content are equivalent, which frequently results in inconsistent and conflicting study findings. The chemicals detected also vary with the voltage or power used to generate the aerosol. Different flavors may carry varying levels of risk; for example, mint- and menthol-flavored e-cigarettes were shown to expose users to dangerous levels of pulegone, a carcinogenic compound banned as a food additive in 2018.42 The concentrations of some of these chemicals are sufficiently high to be of toxicologic concern; for example, one study reported the presence of benzaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosol at twice the workplace exposure limit.43

Biologic effects

In an in vitro study,44 57% of e-liquids studied were found to be cytotoxic to human pulmonary fibroblasts, lung epithelial cells, and human embryonic stem cells. Fruit-flavored e-liquids in particular caused a significant increase in DNA fragmentation. Cell cultures treated with e-cigarette liquids showed increased oxidative stress, reduced cell proliferation, and increased DNA damage,44 which may have implications for carcinogenic risk.

In another study,45 exposure to e-cigarette aerosol as well as conventional cigarette smoke resulted in suppression of genes related to immune and inflammatory response in respiratory epithelial cells. All genes with decreased expression after exposure to conventional cigarette smoke also showed decreased expression with exposure to e-cigarette smoke, which the study authors suggested could lead to immune suppression at the level of the nasal mucosa. Diacetyl and acetoin, chemicals found in certain flavorings, have been linked to bronchiolitis obliterans, or “popcorn lung.”46

Nicotine is not benign

The nicotine itself in many vaping liquids should also not be underestimated. Nicotine has harmful neurocognitive effects and addictive properties, particularly in the developing brains of adolescents and young adults.47 Nicotine exposure during adolescence negatively affects memory, attention, and emotional regulation,48 as well as executive functioning, reward processing, and learning.49

The brain undergoes major structural remodeling in adolescence, and nicotine acetylcholine receptors regulate neural maturation. Early exposure to nicotine disrupts this process, leading to poor executive functioning, difficulty learning, decreased memory, and issues with reward processing.

Fetal exposure, if nicotine products are used during pregnancy, has also been linked to adverse consequences such as deficits in attention and cognition, behavioral effects, and sudden infant death syndrome.5

Much to learn about toxicity

Partly because vaping devices have been available to US consumers only since 2007, limited evidence is available regarding the long-term effects of exposure to the aerosol from these devices in humans.1 Many of the studies mentioned above were in vitro studies or conducted in mouse models. Differences in device design and the composition of the e-liquid among device brands pose a challenge for developing well-designed studies of the long-term health effects of e-cigarette and vape use. Additionally, devices may have different health impacts when used to vape cannabis or other drugs besides nicotine, which requires further investigation.

E-CIGARETTES AND SMOKING CESSATION

Conventional cigarette smoking is a major public health threat, as tobacco use is responsible for 480,000 deaths annually in the United States.50

And smoking is extremely difficult to quit: as many as 80% of smokers who attempt to quit resume smoking within the first month.51 The chance of successfully quitting improves by over 50% if the individual undergoes nicotine replacement therapy, and it improves even more with counseling.50

There are currently 5 types of FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy products (gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray) to help with smoking cessation. In addition, 2 non-nicotine prescription drugs (varenicline and bupropion) have been approved for treating tobacco dependence.

Can vaping devices be added to the list of nicotine replacement therapy products? Although some manufacturers try to brand their devices as smoking cessation aids, in one study,52 one-third of e-cigarette users said they had either never used conventional cigarettes or had formerly smoked them.

Bullen et al53 randomized smokers interested in quitting to receive either e-cigarettes, nicotine patches, or placebo (nicotine-free) e-cigarettes and followed them for 6 months. Rates of tobacco cessation were less than predicted for the entire study population, resulting in insufficient power to determine the superiority of any single method, but the study authors concluded that nicotine e-cigarettes were “modestly effective” at helping smokers quit, and that abstinence rates may be similar to those with nicotine patches.53

Hajek et al54 randomized 886 smokers to e-cigarette or nicotine replacement products of their choice. After 1 year, 18% of e-cigarette users had stopped smoking, compared with 9.9% of nicotine replacement product users. However, 80% of the e-cigarette users were still using e-cigarettes after 1 year, while only 9% of nicotine replacement product users were still using nicotine replacement therapy products after 1 year.

While quitting conventional cigarette smoking altogether has widely established health benefits, little is known about the health benefits of transitioning from conventional cigarette smoking to reduced conventional cigarette smoking with concomitant use of e-cigarettes.

Campagna et al55 found no beneficial health effects in smokers who partially substituted conventional cigarettes for e-cigarettes.

Many studies found that smokers use e-cigarettes to maintain their habit instead of quitting entirely.56 It has been suggested that any slight increase in effectiveness in smoking cessation by using e-cigarettes compared with other nicotine replacement products could be linked to satisfying of the habitual smoking actions, such as inhaling and bringing the hand to the mouth,24 which are absent when using other nicotine replacement methods such as a nicotine patch.

As with safety information, long-term outcomes regarding the use of vape devices for smoking cessation have not been yet established, as this option is still relatively new.

VAPING AS A GATEWAY DRUG