User login

Sudden Cardiac Death in a Young Patient With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

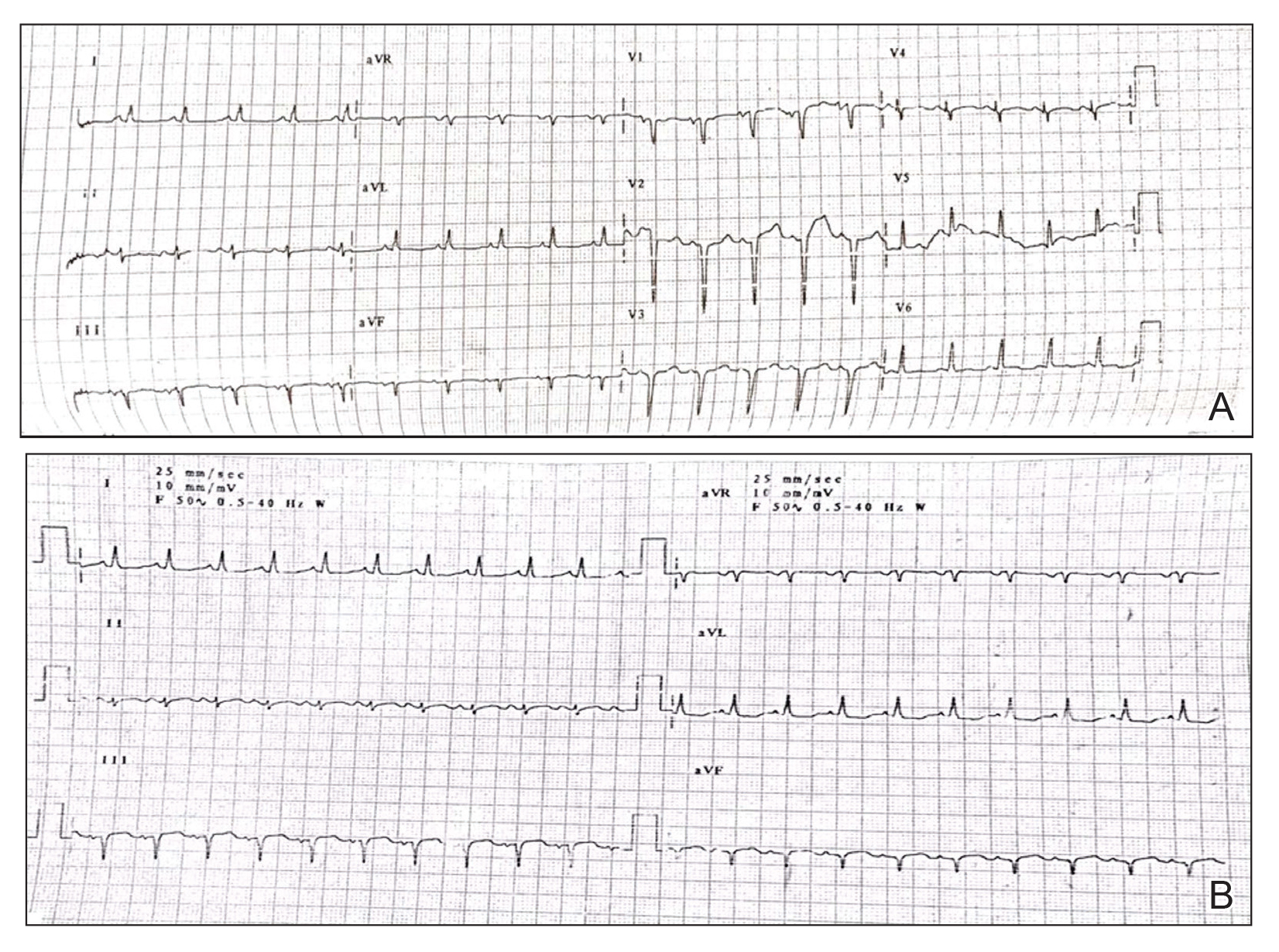

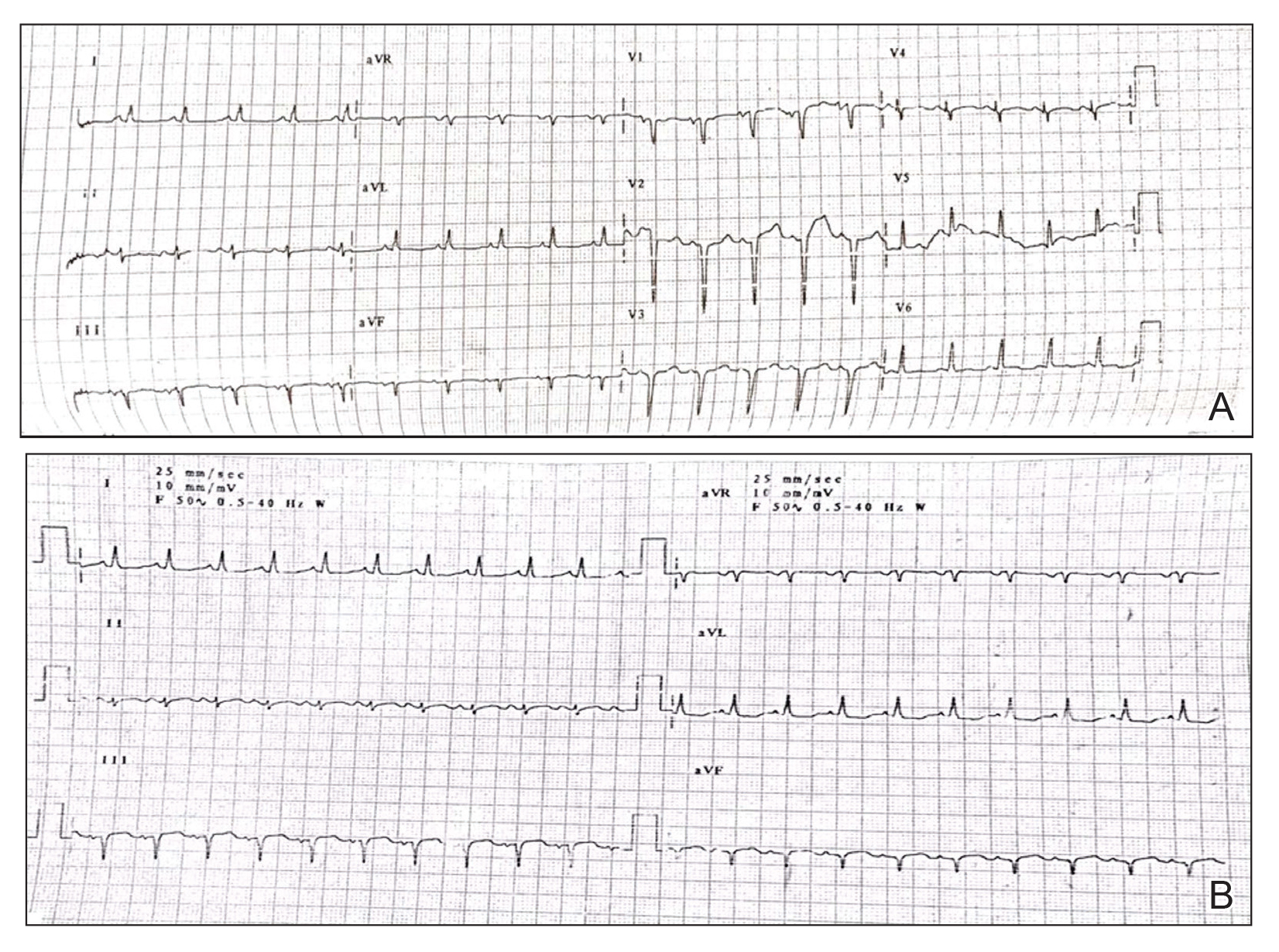

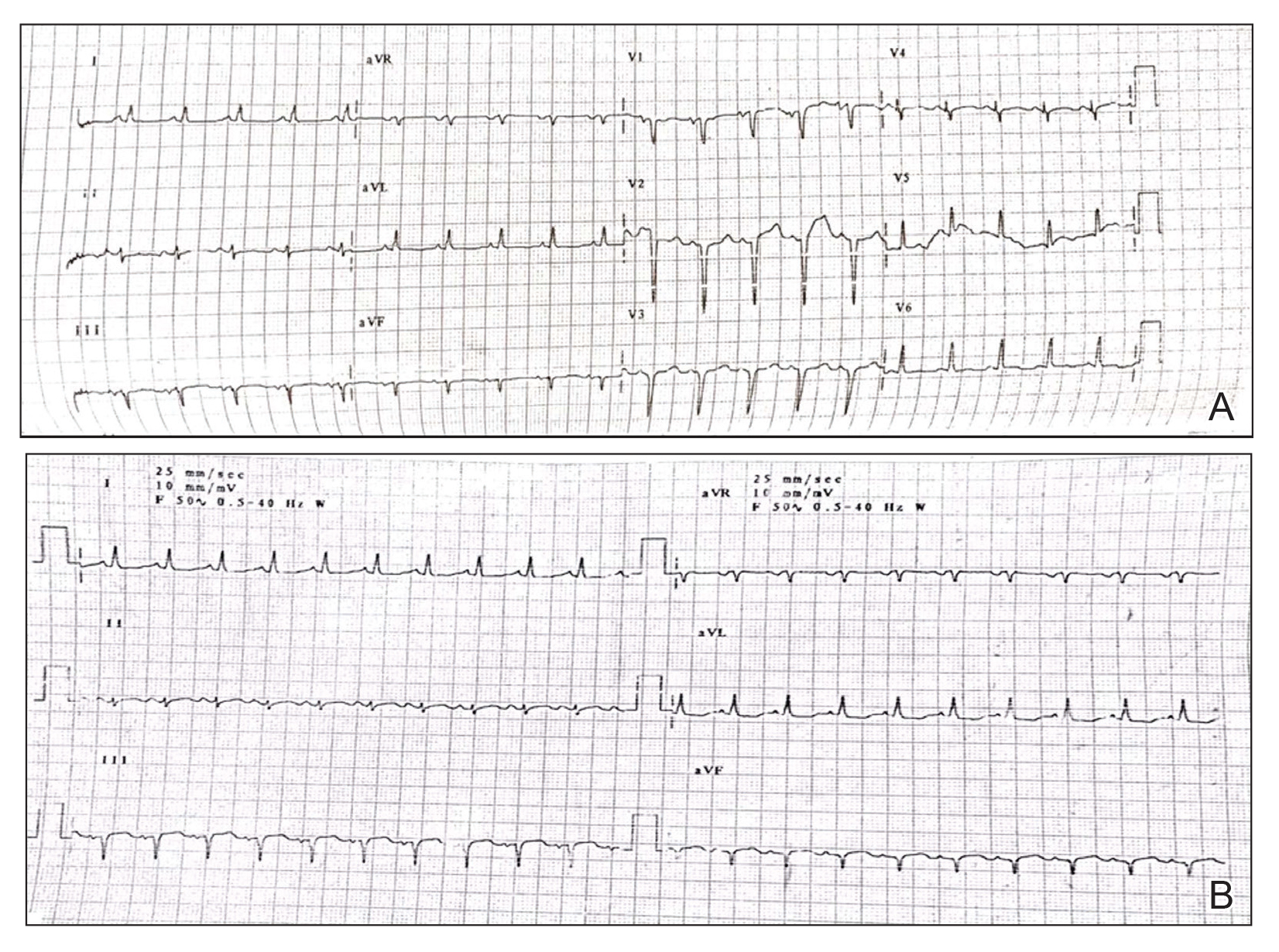

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

Practice Points

- Low-grade chronic inflammation in patients with psoriasis can lead to vascular inflammation, which can further lead to the development of major adverse cardiovascular events (CVEs) and arrhythmia.

- The need for a multidisciplinary approach and close monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis to prevent a CVE is vital.

- Baseline electrocardiogram and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease also should be performed in young patients with severe or unstable psoriasis.

Multiple linear subcutaneous nodules

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

A 34-year-old woman sought consultation at our clinic for an asymptomatic swelling on her right foot that had been growing very slowly over the last 15 years. She said she had presented to other healthcare facilities, but no diagnosis had been made and no treatment had been offered.

Examination revealed a linear swelling extending from the lower third to the mid-dorsal surface of the right foot (Figure 1). Palpation revealed multiple, closely set nodules arranged in a linear fashion. This finding along with the history raised the suspicion of neurofibroma and other conditions in the differential diagnosis, eg, pure neuritic Hansen disease, phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The rest of the mucocutaneous examination results were normal. No café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, or other swelling suggestive of neurofibroma was seen. She had no family history of mucocutaneous disease or other systemic disorder.

Because of the suspicion of neurofibromatosis, slit-lamp examination of the eyes was done to rule out Lisch nodules, a common feature of neurofibromatosis; the results were normal. Plain radiography of the right foot showed only soft-tissue swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, done to determine the extent of the lesions, revealed multiple dumbbell-shaped lesions with homogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). Histopathologic study of a biopsy specimen of the lesions showed tumor cells in the dermis. The cells were long, with elongated nuclei with pointed ends, arranged in long and short fascicles—an appearance characteristic of neurofibroma. Areas of hypocellularity and hypercellularity were seen, and on S100 protein immunostaining, the tumor cells showed strong nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity (Figure 3).

The histologic evaluation confirmed neurofibroma. The specific diagnosis of sporadic solitary neurofibroma was made based on the onset of the lesions, the number of lesions (one in this patient), and the absence of features suggestive of neurofibromatosis.

SPORADIC SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibroma is a common tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath and, when present with features such as café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, and characteristic bone changes, it is pathognomic of neurofibromatosis type 1.1 But solitary neurofibromas can occur sporadically in the absence of other features of neurofibromatosis.

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma arises from small nerves, is benign in nature, and carries a lower rate of malignant transformation than its counterpart that occurs in the setting of neurofibromatosis.2 Though sporadic solitary neurofibroma can occur in any part of the body, it is commonly seen on the head and neck, and occasionally on the presacral and parasacral space, thigh, intrascrotal area,3 the ankle and foot,4,5 and the subungual region.6 A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors examined over 30 years showed 55 sporadic solitary neurofibromas occurring in the brachial plexus region, 45 in the upper extremities, 10 in the pelvic plexus, and 31 in the lower extremities.7

Management of sporadic solitary neurofibroma depends on the patient’s discomfort. For asymptomatic lesions, serial observation is all that is required. Complete surgical excision including the parent nerve is the treatment for large lesions. More research is needed to define the potential role of drugs such as pirfenidone and tipifarnib.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Sporadic solitary neurofibroma can masquerade as pure neuritic Hansen disease (leprosy), phaeohyphomycosis, and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. The absence of neural symptoms and no evidence of trophic changes exclude pure neuritic Hansen disease. Phaeohyphomycosis clinically presents as a single cyst that may evolve into pigmented plaques,8 and the diagnosis relies on the presence of fungus in tissue. The absence of cystic changes clinically and fungi histopathologically in this patient did not favor phaeohyphomycosis. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is characterized clinically by cordlike skin lesions (the “rope sign”) and is accompanied by extracutaneous, mostly articular features. Histopathologically, it shows intense neutrophilic infiltrate and interstitial histiocytic infiltrate along with collagen degeneration. The absence of extracutaneous and classical histologic features negated this possibility in this patient.

Though sporotrichosis and cutaneous atypical mycobacterial infections may present in linear fashion following the course of the lymphatic vessels, the absence of epidermal changes after a disease course of 15 years and the absence of granulomatous infiltrate in histopathology excluded these possibilities in this patient.

The patient was referred to a plastic surgeon, and the lesions were successfully resected. She did not return for additional review after that.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.

- Hirbe AC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:834–843.

- Pulathan Z, Imamoglu M, Cay A, Guven YK. Intermittent claudication due to right common femoral artery compression by a solitary neurofibroma. Eur J Pediatr 2005; 164:463–465.

- Hosseini MM, Geramizadeh B, Shakeri S, Karimi MH. Intrascrotal solitary neurofibroma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Ann 2012; 4:119–121.

- Carvajal JA, Cuartas E, Qadir R, Levi AD, Temple HT. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32:163–167.

- Tahririan MA, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Heidarpour M, Hekmatnia F. Solitary giant neurofibroma of thigh. Adv Biomed Res 2014; 3:158.

- Huajun J, Wei Q, Ming L, Chongyang F, Weiguo Z, Decheng L. Solitary subungual neurofibroma in the right first finger. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51:335–338.

- Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102:246–255.

- Garnica M, Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F. Difficult mycoses of the skin: advances in the epidemiology and management of eumycetoma, phaeohyphomycosis and chromoblastomycosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22:559–563.