User login

Bleeding esophageal varices: Who should receive a shunt?

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been shown in randomized controlled trials to be effective for:

- Secondary prevention of variceal bleeding

- Controlling refractory ascites in patients with liver cirrhosis.

In addition, findings from retrospective case series have suggested that it helps in cases of:

- Acute variceal bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

- Gastropathy due to portal hypertension

- Bleeding gastric varices

- Refractory hepatic hydrothorax

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Veno-occlusive disease

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Here, we discuss the indications for a TIPS in cirrhotic patients with esophageal variceal bleeding.

CIRRHOSIS CAN LEAD TO PORTAL HYPERTENSION, BLEEDING

Cirrhosis of the liver alters the hepatic architecture. Development of regenerating nodules and deposition of connective tissue between these nodules increase the resistance to portal blood flow, which can lead to portal hypertension.1

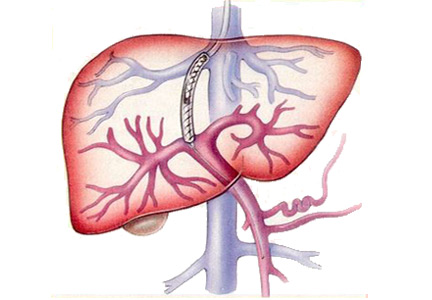

Esophageal variceal bleeding is a complication of portal hypertension and a major cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis. Combined treatment with vasoactive drugs, prophylactic antibiotics, and endoscopic band ligation is the standard of care for patients with acute bleeding. However, this treatment fails in about 10% to 15% of these patients. A TIPS creates a connection between the portal and hepatic veins, resulting in portal decompression and homeostasis.2

PRE-TIPS EVALUATION

Patients being considered for a TIPS should be medically assessed before the procedure. The workup should include the following:

- Routine blood tests, including blood type and screen (indirect Coombs test), complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time

- Doppler ultrasonography of the liver to ensure that the portal and hepatic veins are patent

- Echocardiography to assess pulmonary arterial pressure and right-side heart function

- The hepatic venous pressure gradient, which is measured at the time of TIPS placement, reflects the degree of portal hypertension. A hepatic vein is catheterized, and the right atrial pressure or the free hepatic venous pressure is subtracted from the wedged hepatic venous pressure. The gradient is normally 1 to 5 mm Hg. A gradient greater than 5 mm Hg indicates portal hypertension, and esophageal varices may start to bleed when the gradient is greater than 12 mm Hg. The goal of TIPS placement is to reduce the gradient to less than 12 mm Hg, or at least by 50%.

Heart failure is a contraindication

Pulmonary hypertension may follow TIPS placement because the shunt increases venous return to the heart. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance decreases in patients who have a shunt. This further worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state already present in patients with cirrhosis. Cardiac output increases in response to these changes. When the heart’s ability to handle this “volume overload” is exceeded, pulmonary venous pressures rise, with increasing ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypoxia, and pulmonary vasoconstriction; pulmonary edema may ensue.

Congestive heart failure, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and severe pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary pressures > 45 mm Hg) are therefore considered absolute contraindications to TIPS placement.3,4 This is why echocardiography is recommended to assess pulmonary pressure along with the size and function of the right side of the heart before proceeding with TIPS insertion.

Other considerations

TIPS insertion is not recommended in patients with active hepatic encephalopathy, which should be adequately controlled before insertion of a TIPS. This can be achieved with lactulose and rifaximin. Lactulose is a laxative; the recommended target is 3 to 4 bowel movements daily. Rifaximin is a poorly absorbed antibiotic that has a wide spectrum of coverage, affecting gram-negative and gram-positive aerobes and anaerobes. It wipes out the gut bacteria and so decreases the production of ammonia by the gut.

Paracentesis is recommended before TIPS placement if a large volume of ascites is present. Draining the fluid allows the liver to drop down and makes it easier to access the portal vein from the hepatic vein.

WHEN TO CONSIDER A TIPS IN ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BLEEDING

Acute bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

A TIPS remains the only choice to control acute variceal bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic therapy (Figure 1), with a success rate of 90% to 100%.5 The urgency of TIPS placement is an independent predictor of early mortality.

Esophageal variceal rebleeding

Once varices bleed, the risk of rebleeding is higher than 50%, and rebleeding is associated with a high mortality rate. TIPS should be considered if nonselective beta-blockers and surveillance with upper endoscopy and banding fail to prevent rebleeding, with many studies showing a TIPS to be superior to pharmacologic and endoscopic therapies.6

A meta-analysis in 1999 by Papatheodoridis et al6 found that variceal rebleeding was significantly more frequent with endoscopic therapies, at 47% vs 19% with a TIPS, but the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was higher with TIPS (34% vs 19%; P < .001), and there was no difference in mortality rates.

Hepatic encephalopathy occurs in 15% to 25% of patients after TIPS procedures. Risk factors include advanced age, poor renal function, and a history of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy can be managed with lactulose or rifaximin, or both (see above). Narcotics, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines should be avoided. In rare cases (5%) when hepatic encephalopathy is refractory to medical therapy, liver transplant should be considered.

A surgical distal splenorenal shunt is another option for patients with refractory or recurrent variceal bleeding. In a large randomized controlled trial,7 140 cirrhotic patients with recurrent variceal bleeding were randomized to receive either a distal splenorenal shunt or a TIPS. At a mean follow-up of 48 months, there was no difference in the rates of rebleeding between the two groups (5.5% with a surgical shunt vs 10.5% with a TIPS, P = .29) or in hepatic encephalopathy (50% in both groups). Survival rates were comparable between the two groups at 2 years (81% with a surgical shunt vs 88% with a TIPS) and 5 years (62% vs 61%).

Early use of TIPS after first variceal bleeding

In a 2010 randomized controlled trial,8 63 patients with cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C) and acute variceal bleeding who had received standard medical and endoscopic therapy were randomized to receive either a TIPS within 72 hours of admission or long-term conservative treatment with nonselective beta-blockers and endoscopic band ligation. The 1-year actuarial probability of remaining free of rebleeding or failure to control bleeding was 50% in the conservative treatment group vs 97% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001). The 1-year actuarial survival rate was 61% in the conservative treatment group vs 86% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001).

The authors8 concluded that early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and Child-Pugh scores of 7 to 13 who were hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding was associated with significant reductions in rates of treatment failure and mortality.

- Brenner D, Rippe RA. Pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

- Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:936–946.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD; Practice Guidelines Committee of American Association for Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:2086–2102.

- Azoulay D, Castaing D, Dennison A, Martino W, Eyraud D, Bismuth H. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state of the cirrhotic patient: preliminary report of a prospective study. Hepatology 1994; 19:129–132.

- Rodríguez-Laiz JM, Bañares R, Echenagusia A, et al. Effects of transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunt (TIPS) on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics, and hepatic function in patients with portal hypertension. Preliminary results. Dig Dis Sci 1995; 40:2121–2127.

- Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999; 30:612–622.

- Henderson JM, Boyer TD, Kutner MH, et al; DIVERT Study Group. Distal splenorenal shunt versus transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt for variceal bleeding: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:1643–1651.

- García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:2370–2379.

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been shown in randomized controlled trials to be effective for:

- Secondary prevention of variceal bleeding

- Controlling refractory ascites in patients with liver cirrhosis.

In addition, findings from retrospective case series have suggested that it helps in cases of:

- Acute variceal bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

- Gastropathy due to portal hypertension

- Bleeding gastric varices

- Refractory hepatic hydrothorax

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Veno-occlusive disease

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Here, we discuss the indications for a TIPS in cirrhotic patients with esophageal variceal bleeding.

CIRRHOSIS CAN LEAD TO PORTAL HYPERTENSION, BLEEDING

Cirrhosis of the liver alters the hepatic architecture. Development of regenerating nodules and deposition of connective tissue between these nodules increase the resistance to portal blood flow, which can lead to portal hypertension.1

Esophageal variceal bleeding is a complication of portal hypertension and a major cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis. Combined treatment with vasoactive drugs, prophylactic antibiotics, and endoscopic band ligation is the standard of care for patients with acute bleeding. However, this treatment fails in about 10% to 15% of these patients. A TIPS creates a connection between the portal and hepatic veins, resulting in portal decompression and homeostasis.2

PRE-TIPS EVALUATION

Patients being considered for a TIPS should be medically assessed before the procedure. The workup should include the following:

- Routine blood tests, including blood type and screen (indirect Coombs test), complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time

- Doppler ultrasonography of the liver to ensure that the portal and hepatic veins are patent

- Echocardiography to assess pulmonary arterial pressure and right-side heart function

- The hepatic venous pressure gradient, which is measured at the time of TIPS placement, reflects the degree of portal hypertension. A hepatic vein is catheterized, and the right atrial pressure or the free hepatic venous pressure is subtracted from the wedged hepatic venous pressure. The gradient is normally 1 to 5 mm Hg. A gradient greater than 5 mm Hg indicates portal hypertension, and esophageal varices may start to bleed when the gradient is greater than 12 mm Hg. The goal of TIPS placement is to reduce the gradient to less than 12 mm Hg, or at least by 50%.

Heart failure is a contraindication

Pulmonary hypertension may follow TIPS placement because the shunt increases venous return to the heart. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance decreases in patients who have a shunt. This further worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state already present in patients with cirrhosis. Cardiac output increases in response to these changes. When the heart’s ability to handle this “volume overload” is exceeded, pulmonary venous pressures rise, with increasing ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypoxia, and pulmonary vasoconstriction; pulmonary edema may ensue.

Congestive heart failure, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and severe pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary pressures > 45 mm Hg) are therefore considered absolute contraindications to TIPS placement.3,4 This is why echocardiography is recommended to assess pulmonary pressure along with the size and function of the right side of the heart before proceeding with TIPS insertion.

Other considerations

TIPS insertion is not recommended in patients with active hepatic encephalopathy, which should be adequately controlled before insertion of a TIPS. This can be achieved with lactulose and rifaximin. Lactulose is a laxative; the recommended target is 3 to 4 bowel movements daily. Rifaximin is a poorly absorbed antibiotic that has a wide spectrum of coverage, affecting gram-negative and gram-positive aerobes and anaerobes. It wipes out the gut bacteria and so decreases the production of ammonia by the gut.

Paracentesis is recommended before TIPS placement if a large volume of ascites is present. Draining the fluid allows the liver to drop down and makes it easier to access the portal vein from the hepatic vein.

WHEN TO CONSIDER A TIPS IN ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BLEEDING

Acute bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

A TIPS remains the only choice to control acute variceal bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic therapy (Figure 1), with a success rate of 90% to 100%.5 The urgency of TIPS placement is an independent predictor of early mortality.

Esophageal variceal rebleeding

Once varices bleed, the risk of rebleeding is higher than 50%, and rebleeding is associated with a high mortality rate. TIPS should be considered if nonselective beta-blockers and surveillance with upper endoscopy and banding fail to prevent rebleeding, with many studies showing a TIPS to be superior to pharmacologic and endoscopic therapies.6

A meta-analysis in 1999 by Papatheodoridis et al6 found that variceal rebleeding was significantly more frequent with endoscopic therapies, at 47% vs 19% with a TIPS, but the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was higher with TIPS (34% vs 19%; P < .001), and there was no difference in mortality rates.

Hepatic encephalopathy occurs in 15% to 25% of patients after TIPS procedures. Risk factors include advanced age, poor renal function, and a history of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy can be managed with lactulose or rifaximin, or both (see above). Narcotics, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines should be avoided. In rare cases (5%) when hepatic encephalopathy is refractory to medical therapy, liver transplant should be considered.

A surgical distal splenorenal shunt is another option for patients with refractory or recurrent variceal bleeding. In a large randomized controlled trial,7 140 cirrhotic patients with recurrent variceal bleeding were randomized to receive either a distal splenorenal shunt or a TIPS. At a mean follow-up of 48 months, there was no difference in the rates of rebleeding between the two groups (5.5% with a surgical shunt vs 10.5% with a TIPS, P = .29) or in hepatic encephalopathy (50% in both groups). Survival rates were comparable between the two groups at 2 years (81% with a surgical shunt vs 88% with a TIPS) and 5 years (62% vs 61%).

Early use of TIPS after first variceal bleeding

In a 2010 randomized controlled trial,8 63 patients with cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C) and acute variceal bleeding who had received standard medical and endoscopic therapy were randomized to receive either a TIPS within 72 hours of admission or long-term conservative treatment with nonselective beta-blockers and endoscopic band ligation. The 1-year actuarial probability of remaining free of rebleeding or failure to control bleeding was 50% in the conservative treatment group vs 97% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001). The 1-year actuarial survival rate was 61% in the conservative treatment group vs 86% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001).

The authors8 concluded that early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and Child-Pugh scores of 7 to 13 who were hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding was associated with significant reductions in rates of treatment failure and mortality.

A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been shown in randomized controlled trials to be effective for:

- Secondary prevention of variceal bleeding

- Controlling refractory ascites in patients with liver cirrhosis.

In addition, findings from retrospective case series have suggested that it helps in cases of:

- Acute variceal bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

- Gastropathy due to portal hypertension

- Bleeding gastric varices

- Refractory hepatic hydrothorax

- Hepatorenal syndrome

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Veno-occlusive disease

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Here, we discuss the indications for a TIPS in cirrhotic patients with esophageal variceal bleeding.

CIRRHOSIS CAN LEAD TO PORTAL HYPERTENSION, BLEEDING

Cirrhosis of the liver alters the hepatic architecture. Development of regenerating nodules and deposition of connective tissue between these nodules increase the resistance to portal blood flow, which can lead to portal hypertension.1

Esophageal variceal bleeding is a complication of portal hypertension and a major cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis. Combined treatment with vasoactive drugs, prophylactic antibiotics, and endoscopic band ligation is the standard of care for patients with acute bleeding. However, this treatment fails in about 10% to 15% of these patients. A TIPS creates a connection between the portal and hepatic veins, resulting in portal decompression and homeostasis.2

PRE-TIPS EVALUATION

Patients being considered for a TIPS should be medically assessed before the procedure. The workup should include the following:

- Routine blood tests, including blood type and screen (indirect Coombs test), complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time

- Doppler ultrasonography of the liver to ensure that the portal and hepatic veins are patent

- Echocardiography to assess pulmonary arterial pressure and right-side heart function

- The hepatic venous pressure gradient, which is measured at the time of TIPS placement, reflects the degree of portal hypertension. A hepatic vein is catheterized, and the right atrial pressure or the free hepatic venous pressure is subtracted from the wedged hepatic venous pressure. The gradient is normally 1 to 5 mm Hg. A gradient greater than 5 mm Hg indicates portal hypertension, and esophageal varices may start to bleed when the gradient is greater than 12 mm Hg. The goal of TIPS placement is to reduce the gradient to less than 12 mm Hg, or at least by 50%.

Heart failure is a contraindication

Pulmonary hypertension may follow TIPS placement because the shunt increases venous return to the heart. Additionally, systemic vascular resistance decreases in patients who have a shunt. This further worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state already present in patients with cirrhosis. Cardiac output increases in response to these changes. When the heart’s ability to handle this “volume overload” is exceeded, pulmonary venous pressures rise, with increasing ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypoxia, and pulmonary vasoconstriction; pulmonary edema may ensue.

Congestive heart failure, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and severe pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary pressures > 45 mm Hg) are therefore considered absolute contraindications to TIPS placement.3,4 This is why echocardiography is recommended to assess pulmonary pressure along with the size and function of the right side of the heart before proceeding with TIPS insertion.

Other considerations

TIPS insertion is not recommended in patients with active hepatic encephalopathy, which should be adequately controlled before insertion of a TIPS. This can be achieved with lactulose and rifaximin. Lactulose is a laxative; the recommended target is 3 to 4 bowel movements daily. Rifaximin is a poorly absorbed antibiotic that has a wide spectrum of coverage, affecting gram-negative and gram-positive aerobes and anaerobes. It wipes out the gut bacteria and so decreases the production of ammonia by the gut.

Paracentesis is recommended before TIPS placement if a large volume of ascites is present. Draining the fluid allows the liver to drop down and makes it easier to access the portal vein from the hepatic vein.

WHEN TO CONSIDER A TIPS IN ESOPHAGEAL VARICEAL BLEEDING

Acute bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy

A TIPS remains the only choice to control acute variceal bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic therapy (Figure 1), with a success rate of 90% to 100%.5 The urgency of TIPS placement is an independent predictor of early mortality.

Esophageal variceal rebleeding

Once varices bleed, the risk of rebleeding is higher than 50%, and rebleeding is associated with a high mortality rate. TIPS should be considered if nonselective beta-blockers and surveillance with upper endoscopy and banding fail to prevent rebleeding, with many studies showing a TIPS to be superior to pharmacologic and endoscopic therapies.6

A meta-analysis in 1999 by Papatheodoridis et al6 found that variceal rebleeding was significantly more frequent with endoscopic therapies, at 47% vs 19% with a TIPS, but the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy was higher with TIPS (34% vs 19%; P < .001), and there was no difference in mortality rates.

Hepatic encephalopathy occurs in 15% to 25% of patients after TIPS procedures. Risk factors include advanced age, poor renal function, and a history of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy can be managed with lactulose or rifaximin, or both (see above). Narcotics, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines should be avoided. In rare cases (5%) when hepatic encephalopathy is refractory to medical therapy, liver transplant should be considered.

A surgical distal splenorenal shunt is another option for patients with refractory or recurrent variceal bleeding. In a large randomized controlled trial,7 140 cirrhotic patients with recurrent variceal bleeding were randomized to receive either a distal splenorenal shunt or a TIPS. At a mean follow-up of 48 months, there was no difference in the rates of rebleeding between the two groups (5.5% with a surgical shunt vs 10.5% with a TIPS, P = .29) or in hepatic encephalopathy (50% in both groups). Survival rates were comparable between the two groups at 2 years (81% with a surgical shunt vs 88% with a TIPS) and 5 years (62% vs 61%).

Early use of TIPS after first variceal bleeding

In a 2010 randomized controlled trial,8 63 patients with cirrhosis (Child-Pugh class B or C) and acute variceal bleeding who had received standard medical and endoscopic therapy were randomized to receive either a TIPS within 72 hours of admission or long-term conservative treatment with nonselective beta-blockers and endoscopic band ligation. The 1-year actuarial probability of remaining free of rebleeding or failure to control bleeding was 50% in the conservative treatment group vs 97% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001). The 1-year actuarial survival rate was 61% in the conservative treatment group vs 86% in the early-TIPS group (P < .001).

The authors8 concluded that early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and Child-Pugh scores of 7 to 13 who were hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding was associated with significant reductions in rates of treatment failure and mortality.

- Brenner D, Rippe RA. Pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

- Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:936–946.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD; Practice Guidelines Committee of American Association for Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:2086–2102.

- Azoulay D, Castaing D, Dennison A, Martino W, Eyraud D, Bismuth H. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state of the cirrhotic patient: preliminary report of a prospective study. Hepatology 1994; 19:129–132.

- Rodríguez-Laiz JM, Bañares R, Echenagusia A, et al. Effects of transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunt (TIPS) on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics, and hepatic function in patients with portal hypertension. Preliminary results. Dig Dis Sci 1995; 40:2121–2127.

- Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999; 30:612–622.

- Henderson JM, Boyer TD, Kutner MH, et al; DIVERT Study Group. Distal splenorenal shunt versus transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt for variceal bleeding: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:1643–1651.

- García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:2370–2379.

- Brenner D, Rippe RA. Pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

- Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:936–946.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD; Practice Guidelines Committee of American Association for Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:2086–2102.

- Azoulay D, Castaing D, Dennison A, Martino W, Eyraud D, Bismuth H. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt worsens the hyperdynamic circulatory state of the cirrhotic patient: preliminary report of a prospective study. Hepatology 1994; 19:129–132.

- Rodríguez-Laiz JM, Bañares R, Echenagusia A, et al. Effects of transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunt (TIPS) on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics, and hepatic function in patients with portal hypertension. Preliminary results. Dig Dis Sci 1995; 40:2121–2127.

- Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999; 30:612–622.

- Henderson JM, Boyer TD, Kutner MH, et al; DIVERT Study Group. Distal splenorenal shunt versus transjugular intrahepatic portal systemic shunt for variceal bleeding: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:1643–1651.

- García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:2370–2379.

A female liver transplant recipient asks: Can I become pregnant?

Yes, pregnancy is possible, but not immediately after transplant, and it involves risks. Appropriate management and multidisciplinary care are necessary to optimize the outcomes.

HOW LONG SHOULD PREGNANCY BE POSTPONED?

Hypogonadism and amenorrhea are common and multifactorial in women with end-stage liver disease. Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, elevated estrogen level, and malnutrition all contribute to the problem.1 However, most premenopausal women experience a return of their menstrual cycle, and possibly of fertility, within the first 10 months after liver transplant,2,3 after which pregnancy is possible.

In transplant recipients of childbearing age, the need for preconception counseling and family planning should be emphasized. The timing, potential risks, and outcomes of pregnancy, and the importance of coordinated prenatal and perinatal care should be addressed.4 The National Transplant Pregnancy Registry guidelines recommend postponing conception until:

- At least 1 year has elapsed after transplant

- Graft function is stable

- Medical comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension are well controlled

- Immunosuppression is at a low maintenance level.3

Strong evidence suggests that an appropriate liver transplant-conception interval reduces adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. In particular, the risks of a low birth weight, graft rejection, and loss during pregnancy are significantly decreased.3 Therefore, contraception must be initiated after transplant before any sexual activity, with no preference as to the form of protection used.

Limited data demonstrate the safety and efficacy of combined oral contraceptives and transdermal contraceptive patches in stable solid-organ recipients.5,6 Estrogen-containing contraceptives should, however, be avoided in recurrent liver disease after transplant because of the risk of increased hepatic toxicity.

MANAGING RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY

Physicians should be alert to the possibility of a pregnancy. Early diagnosis allows the optimization of management and outcomes, as complications are increased in this population of expectant mothers.7

Well-known risks to the expectant liver transplant recipient include hypertension and preeclampsia.8 Moreover, infants born to these patients have a higher risk of prematurity and low birth weight.3,7,9 However, rates of neonatal or maternal deaths and birth defects do not differ significantly from those seen in the general population. Graft rejection is a potential complication, with rates varying between 0% and 20% in different studies.3

Multidisciplinary care is therefore crucial during these high-risk pregnancies.10 An obstetrician, a hepatologist, and a perinatalogist should collaborate to maximize outcomes.11 Frequent evaluations, preferably 2 weeks apart, are suggested for the serial assessment of fetal growth.

Furthermore, daily monitoring of the blood pressure and aggressive management of hypertension are recommended. Methyldopa appears to be the drug treatment of choice.12

Close monitoring of graft function and liver biopsy in suspected graft rejection are of essence as well.3 Routine screening for urinary tract infection, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis infections, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia should also be undertaken.

MANAGING IMMUNOSUPPRESSION IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

The choice of immunosuppression is ideally made before pregnancy. All immunosuppressive drugs cross the placenta. Thus, in theory, all agents carry risks of teratogenicity and fetal loss. However, immunosuppression is crucial in avoiding rejection. Furthermore, the use of appropriate immunosuppressive regimens prevents negative outcomes. Drugs are classified as class A (safest to use in pregnancy), through classes B, C, D, and X.

Tacrolimus (class C) monotherapy appears to be safe, with attention to the maintenance of therapeutic levels throughout pregnancy. Allograft function and tacrolimus serum levels need to be monitored because of the change in the volume of drug distribution. Cyclosporine (a pregnancy class C drug), prednisone (class B), and azathioprine (class D) are also reasonable options and may also be used if judged necessary.13

Mycophenolic acid and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors such as sirolimus and everolimus are significantly teratogenic and should be avoided in pregnant women. They are more commonly associated with spontaneous abortion, structural abnormalities, and birth defects than other immunosuppressive drugs, especially if taken in the early stages of pregnancy. Cleft lip and palate, absent auditory canals, and microtia have been reported.2,13

- Bell H, Raknerud N, Falch JA, Haug E. Inappropriately low levels of gonadotrophins in amenorrhoeic women with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Eur J Endocrinol 1995; 132:444–449.

- Mass K, Quint EH, Punch MR, Merion RM. Gynecological and reproductive function after liver transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 62:476–479.

- Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Moritz MJ, et al. Report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl 2009; 103–122.

- Parolin MB, Coelho JC, Urbanetz AA, Pampuch M. Contraception and pregnancy after liver transplantation: an update overview. Arq Gastroenterol 2009; 46:154–158. In Portuguese.

- Paulen ME, Folger SG, Curtis KM, Jamieson DJ. Contraceptive use among solid organ transplant patients: a systematic review. Contraception 2010; 82:102–112.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Bobrowska K, Kaminski P, Wielgos M, Zieniewicz K, Krawczyk M. Low-dose hormonal contraception after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2007; 39:1530–1532.

- Coffin CS, Shaheen AA, Burak KW, Myers RP. Pregnancy outcomes among liver transplant recipients in the United States: a nationwide case-control analysis. Liver Transpl 2010; 16:56–63.

- Heneghan MA, Selzner M, Yoshida EM, Mullhaupt B. Pregnancy and sexual function in liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2008; 49:507–519.

- Ho JK, Ko HH, Schaeffer DF, et al. Sexual health after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:1478–1484.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Dabrowski FA, Pietrzak B, Wielgos M. Pregnancy complications after liver transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015; 128:27–29.

- Parhar KS, Gibson PS, Coffin CS. Pregnancy following liver transplantation: review of outcomes and recommendations for management. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26:621–626.

- McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT, et al; Women’s Health Committee of the American Society of Transplantation. Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST Consensus Conference on Reproductive Issues and Transplantation. Am J Transplant 2005; 5:1592–1599.

- Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Lavelanet AF, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation 2006; 82:1698–1702.

Yes, pregnancy is possible, but not immediately after transplant, and it involves risks. Appropriate management and multidisciplinary care are necessary to optimize the outcomes.

HOW LONG SHOULD PREGNANCY BE POSTPONED?

Hypogonadism and amenorrhea are common and multifactorial in women with end-stage liver disease. Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, elevated estrogen level, and malnutrition all contribute to the problem.1 However, most premenopausal women experience a return of their menstrual cycle, and possibly of fertility, within the first 10 months after liver transplant,2,3 after which pregnancy is possible.

In transplant recipients of childbearing age, the need for preconception counseling and family planning should be emphasized. The timing, potential risks, and outcomes of pregnancy, and the importance of coordinated prenatal and perinatal care should be addressed.4 The National Transplant Pregnancy Registry guidelines recommend postponing conception until:

- At least 1 year has elapsed after transplant

- Graft function is stable

- Medical comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension are well controlled

- Immunosuppression is at a low maintenance level.3

Strong evidence suggests that an appropriate liver transplant-conception interval reduces adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. In particular, the risks of a low birth weight, graft rejection, and loss during pregnancy are significantly decreased.3 Therefore, contraception must be initiated after transplant before any sexual activity, with no preference as to the form of protection used.

Limited data demonstrate the safety and efficacy of combined oral contraceptives and transdermal contraceptive patches in stable solid-organ recipients.5,6 Estrogen-containing contraceptives should, however, be avoided in recurrent liver disease after transplant because of the risk of increased hepatic toxicity.

MANAGING RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY

Physicians should be alert to the possibility of a pregnancy. Early diagnosis allows the optimization of management and outcomes, as complications are increased in this population of expectant mothers.7

Well-known risks to the expectant liver transplant recipient include hypertension and preeclampsia.8 Moreover, infants born to these patients have a higher risk of prematurity and low birth weight.3,7,9 However, rates of neonatal or maternal deaths and birth defects do not differ significantly from those seen in the general population. Graft rejection is a potential complication, with rates varying between 0% and 20% in different studies.3

Multidisciplinary care is therefore crucial during these high-risk pregnancies.10 An obstetrician, a hepatologist, and a perinatalogist should collaborate to maximize outcomes.11 Frequent evaluations, preferably 2 weeks apart, are suggested for the serial assessment of fetal growth.

Furthermore, daily monitoring of the blood pressure and aggressive management of hypertension are recommended. Methyldopa appears to be the drug treatment of choice.12

Close monitoring of graft function and liver biopsy in suspected graft rejection are of essence as well.3 Routine screening for urinary tract infection, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis infections, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia should also be undertaken.

MANAGING IMMUNOSUPPRESSION IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

The choice of immunosuppression is ideally made before pregnancy. All immunosuppressive drugs cross the placenta. Thus, in theory, all agents carry risks of teratogenicity and fetal loss. However, immunosuppression is crucial in avoiding rejection. Furthermore, the use of appropriate immunosuppressive regimens prevents negative outcomes. Drugs are classified as class A (safest to use in pregnancy), through classes B, C, D, and X.

Tacrolimus (class C) monotherapy appears to be safe, with attention to the maintenance of therapeutic levels throughout pregnancy. Allograft function and tacrolimus serum levels need to be monitored because of the change in the volume of drug distribution. Cyclosporine (a pregnancy class C drug), prednisone (class B), and azathioprine (class D) are also reasonable options and may also be used if judged necessary.13

Mycophenolic acid and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors such as sirolimus and everolimus are significantly teratogenic and should be avoided in pregnant women. They are more commonly associated with spontaneous abortion, structural abnormalities, and birth defects than other immunosuppressive drugs, especially if taken in the early stages of pregnancy. Cleft lip and palate, absent auditory canals, and microtia have been reported.2,13

Yes, pregnancy is possible, but not immediately after transplant, and it involves risks. Appropriate management and multidisciplinary care are necessary to optimize the outcomes.

HOW LONG SHOULD PREGNANCY BE POSTPONED?

Hypogonadism and amenorrhea are common and multifactorial in women with end-stage liver disease. Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, elevated estrogen level, and malnutrition all contribute to the problem.1 However, most premenopausal women experience a return of their menstrual cycle, and possibly of fertility, within the first 10 months after liver transplant,2,3 after which pregnancy is possible.

In transplant recipients of childbearing age, the need for preconception counseling and family planning should be emphasized. The timing, potential risks, and outcomes of pregnancy, and the importance of coordinated prenatal and perinatal care should be addressed.4 The National Transplant Pregnancy Registry guidelines recommend postponing conception until:

- At least 1 year has elapsed after transplant

- Graft function is stable

- Medical comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension are well controlled

- Immunosuppression is at a low maintenance level.3

Strong evidence suggests that an appropriate liver transplant-conception interval reduces adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. In particular, the risks of a low birth weight, graft rejection, and loss during pregnancy are significantly decreased.3 Therefore, contraception must be initiated after transplant before any sexual activity, with no preference as to the form of protection used.

Limited data demonstrate the safety and efficacy of combined oral contraceptives and transdermal contraceptive patches in stable solid-organ recipients.5,6 Estrogen-containing contraceptives should, however, be avoided in recurrent liver disease after transplant because of the risk of increased hepatic toxicity.

MANAGING RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH PREGNANCY

Physicians should be alert to the possibility of a pregnancy. Early diagnosis allows the optimization of management and outcomes, as complications are increased in this population of expectant mothers.7

Well-known risks to the expectant liver transplant recipient include hypertension and preeclampsia.8 Moreover, infants born to these patients have a higher risk of prematurity and low birth weight.3,7,9 However, rates of neonatal or maternal deaths and birth defects do not differ significantly from those seen in the general population. Graft rejection is a potential complication, with rates varying between 0% and 20% in different studies.3

Multidisciplinary care is therefore crucial during these high-risk pregnancies.10 An obstetrician, a hepatologist, and a perinatalogist should collaborate to maximize outcomes.11 Frequent evaluations, preferably 2 weeks apart, are suggested for the serial assessment of fetal growth.

Furthermore, daily monitoring of the blood pressure and aggressive management of hypertension are recommended. Methyldopa appears to be the drug treatment of choice.12

Close monitoring of graft function and liver biopsy in suspected graft rejection are of essence as well.3 Routine screening for urinary tract infection, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis infections, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia should also be undertaken.

MANAGING IMMUNOSUPPRESSION IN THE PREGNANT PATIENT

The choice of immunosuppression is ideally made before pregnancy. All immunosuppressive drugs cross the placenta. Thus, in theory, all agents carry risks of teratogenicity and fetal loss. However, immunosuppression is crucial in avoiding rejection. Furthermore, the use of appropriate immunosuppressive regimens prevents negative outcomes. Drugs are classified as class A (safest to use in pregnancy), through classes B, C, D, and X.

Tacrolimus (class C) monotherapy appears to be safe, with attention to the maintenance of therapeutic levels throughout pregnancy. Allograft function and tacrolimus serum levels need to be monitored because of the change in the volume of drug distribution. Cyclosporine (a pregnancy class C drug), prednisone (class B), and azathioprine (class D) are also reasonable options and may also be used if judged necessary.13

Mycophenolic acid and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors such as sirolimus and everolimus are significantly teratogenic and should be avoided in pregnant women. They are more commonly associated with spontaneous abortion, structural abnormalities, and birth defects than other immunosuppressive drugs, especially if taken in the early stages of pregnancy. Cleft lip and palate, absent auditory canals, and microtia have been reported.2,13

- Bell H, Raknerud N, Falch JA, Haug E. Inappropriately low levels of gonadotrophins in amenorrhoeic women with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Eur J Endocrinol 1995; 132:444–449.

- Mass K, Quint EH, Punch MR, Merion RM. Gynecological and reproductive function after liver transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 62:476–479.

- Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Moritz MJ, et al. Report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl 2009; 103–122.

- Parolin MB, Coelho JC, Urbanetz AA, Pampuch M. Contraception and pregnancy after liver transplantation: an update overview. Arq Gastroenterol 2009; 46:154–158. In Portuguese.

- Paulen ME, Folger SG, Curtis KM, Jamieson DJ. Contraceptive use among solid organ transplant patients: a systematic review. Contraception 2010; 82:102–112.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Bobrowska K, Kaminski P, Wielgos M, Zieniewicz K, Krawczyk M. Low-dose hormonal contraception after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2007; 39:1530–1532.

- Coffin CS, Shaheen AA, Burak KW, Myers RP. Pregnancy outcomes among liver transplant recipients in the United States: a nationwide case-control analysis. Liver Transpl 2010; 16:56–63.

- Heneghan MA, Selzner M, Yoshida EM, Mullhaupt B. Pregnancy and sexual function in liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2008; 49:507–519.

- Ho JK, Ko HH, Schaeffer DF, et al. Sexual health after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:1478–1484.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Dabrowski FA, Pietrzak B, Wielgos M. Pregnancy complications after liver transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015; 128:27–29.

- Parhar KS, Gibson PS, Coffin CS. Pregnancy following liver transplantation: review of outcomes and recommendations for management. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26:621–626.

- McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT, et al; Women’s Health Committee of the American Society of Transplantation. Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST Consensus Conference on Reproductive Issues and Transplantation. Am J Transplant 2005; 5:1592–1599.

- Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Lavelanet AF, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation 2006; 82:1698–1702.

- Bell H, Raknerud N, Falch JA, Haug E. Inappropriately low levels of gonadotrophins in amenorrhoeic women with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Eur J Endocrinol 1995; 132:444–449.

- Mass K, Quint EH, Punch MR, Merion RM. Gynecological and reproductive function after liver transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 62:476–479.

- Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Moritz MJ, et al. Report from the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR): outcomes of pregnancy after transplantation. Clin Transpl 2009; 103–122.

- Parolin MB, Coelho JC, Urbanetz AA, Pampuch M. Contraception and pregnancy after liver transplantation: an update overview. Arq Gastroenterol 2009; 46:154–158. In Portuguese.

- Paulen ME, Folger SG, Curtis KM, Jamieson DJ. Contraceptive use among solid organ transplant patients: a systematic review. Contraception 2010; 82:102–112.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Bobrowska K, Kaminski P, Wielgos M, Zieniewicz K, Krawczyk M. Low-dose hormonal contraception after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 2007; 39:1530–1532.

- Coffin CS, Shaheen AA, Burak KW, Myers RP. Pregnancy outcomes among liver transplant recipients in the United States: a nationwide case-control analysis. Liver Transpl 2010; 16:56–63.

- Heneghan MA, Selzner M, Yoshida EM, Mullhaupt B. Pregnancy and sexual function in liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2008; 49:507–519.

- Ho JK, Ko HH, Schaeffer DF, et al. Sexual health after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:1478–1484.

- Jabiry-Zieniewicz Z, Dabrowski FA, Pietrzak B, Wielgos M. Pregnancy complications after liver transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015; 128:27–29.

- Parhar KS, Gibson PS, Coffin CS. Pregnancy following liver transplantation: review of outcomes and recommendations for management. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26:621–626.

- McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT, et al; Women’s Health Committee of the American Society of Transplantation. Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST Consensus Conference on Reproductive Issues and Transplantation. Am J Transplant 2005; 5:1592–1599.

- Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Lavelanet AF, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT. Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation 2006; 82:1698–1702.

In reply: Wilson disease

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues for bringing important questions to our attention.

In terms of the differential diagnosis of cholestatic liver injury, we agree that pathologic processes such choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis should be generally considered. However, in the case we described, the patient had no abdominal pain or fever, which makes choledocholithiasis or cholangitis very unlikely. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis can cause chronic liver disease but should not be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute liver injury (acute hepatitis), such as in the case we described.

We agree that the hemolytic anemia typically seen in patients with Wilson disease is Coombs-negative, and that Coombs testing and a peripheral smear should be performed. Both were negative in our patient.

We also agree with Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues that Kayser-Fleischer rings are not necessarily specific for Wilson disease and can be seen in patients with other forms of cholestatic liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis. However, Kayser-Fleischer rings are pathognomonic for acute liver failure from Wilson disease. In other words, when Kayser-Fleischer rings are seen in a patient with acute liver failure, the diagnosis is Wilson disease until proven otherwise.

We discussed on page 112 of our article other treatments such as plasmapheresis as adjunctive therapy to bridge patients with acute liver failure secondary to Wilson disease to transplant. However, liver transplant is still the only definitive and potentially curative treatment.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues for bringing important questions to our attention.

In terms of the differential diagnosis of cholestatic liver injury, we agree that pathologic processes such choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis should be generally considered. However, in the case we described, the patient had no abdominal pain or fever, which makes choledocholithiasis or cholangitis very unlikely. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis can cause chronic liver disease but should not be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute liver injury (acute hepatitis), such as in the case we described.

We agree that the hemolytic anemia typically seen in patients with Wilson disease is Coombs-negative, and that Coombs testing and a peripheral smear should be performed. Both were negative in our patient.

We also agree with Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues that Kayser-Fleischer rings are not necessarily specific for Wilson disease and can be seen in patients with other forms of cholestatic liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis. However, Kayser-Fleischer rings are pathognomonic for acute liver failure from Wilson disease. In other words, when Kayser-Fleischer rings are seen in a patient with acute liver failure, the diagnosis is Wilson disease until proven otherwise.

We discussed on page 112 of our article other treatments such as plasmapheresis as adjunctive therapy to bridge patients with acute liver failure secondary to Wilson disease to transplant. However, liver transplant is still the only definitive and potentially curative treatment.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues for bringing important questions to our attention.

In terms of the differential diagnosis of cholestatic liver injury, we agree that pathologic processes such choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis should be generally considered. However, in the case we described, the patient had no abdominal pain or fever, which makes choledocholithiasis or cholangitis very unlikely. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis can cause chronic liver disease but should not be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute liver injury (acute hepatitis), such as in the case we described.

We agree that the hemolytic anemia typically seen in patients with Wilson disease is Coombs-negative, and that Coombs testing and a peripheral smear should be performed. Both were negative in our patient.

We also agree with Dr. Mirrakhimov and colleagues that Kayser-Fleischer rings are not necessarily specific for Wilson disease and can be seen in patients with other forms of cholestatic liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis. However, Kayser-Fleischer rings are pathognomonic for acute liver failure from Wilson disease. In other words, when Kayser-Fleischer rings are seen in a patient with acute liver failure, the diagnosis is Wilson disease until proven otherwise.

We discussed on page 112 of our article other treatments such as plasmapheresis as adjunctive therapy to bridge patients with acute liver failure secondary to Wilson disease to transplant. However, liver transplant is still the only definitive and potentially curative treatment.

A guide to managing acute liver failure

When the liver fails, it usually fails gradually. The sudden (acute) onset of liver failure, while less common, demands prompt management, with transfer to an intensive care unit, specific treatment depending on the cause, and consideration of liver transplant, without which the mortality rate is high.

This article reviews the definition, epidemiology, etiology, and management of acute liver failure.

DEFINITIONS

Acute liver failure is defined as a syndrome of acute hepatitis with evidence of abnormal coagulation (eg, an international normalized ratio > 1.5) complicated by the development of mental alteration (encephalopathy) within 26 weeks of the onset of illness in a patient without a history of liver disease.1 In general, patients have no evidence of underlying chronic liver disease, but there are exceptions; patients with Wilson disease, vertically acquired hepatitis B virus infection, or autoimmune hepatitis can present with acute liver failure superimposed on chronic liver disease or even cirrhosis.

The term acute liver failure has replaced older terms such as fulminant hepatic failure, hyperacute liver failure, and subacute liver failure, which were used for prognostic purposes. Patients with hyperacute liver failure (defined as development of encephalopathy within 7 days of onset of illness) generally have a good prognosis with medical management, whereas those with subacute liver failure (defined as development of encephalopathy within 5 to 26 weeks of onset of illness) have a poor prognosis without liver transplant.2,3

NEARLY 2,000 CASES A YEAR

There are nearly 2,000 cases of acute liver failure each year in the United States, and it accounts for 6% of all deaths due to liver disease.4 It is more common in women than in men, and more common in white people than in other races. The peak incidence is at a fairly young age, ie, 35 to 45 years.

CAUSES

The most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States and other Western countries is acetaminophen toxicity, followed by viral hepatitis. In contrast, viral hepatitis is the most common cause in developing countries.5

Acetaminophen toxicity

Patients with acetaminophen-induced liver failure tend to be younger than other patients with acute liver failure.1 Nearly half of them present after intentionally taking a single large dose, while the rest present with unintentional toxicity while taking acetaminophen for pain relief on a long-term basis and ingesting more than the recommended dose.6

After ingestion, 52% to 57% of acetaminophen is converted to glucuronide conjugates, and 30% to 44% is converted to sulfate conjugates. These compounds are nontoxic, water-soluble, and rapidly excreted in the urine.

However, about 5% to 10% of ingested acetaminophen is shunted to the cytochrome P450 system. P450 2E1 is the main isoenzyme involved in acetaminophen metabolism, but 1A2, 3A4, and 2A6 also contribute.7,8 P450 2E1 is the same isoenzyme responsible for ethanol metabolism and is inducible. Thus, regular alcohol consumption can increase P450 2E1 activity, setting the stage under certain circumstances for increased acetaminophen metabolism through this pathway.

Metabolism of acetaminophen through the cytochrome P450 pathway results in production of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), the compound that damages the liver. NAPQI is rendered nontoxic by binding to glutathione, forming NAPQI-glutathione adducts. Glutathione capacity is limited, however. With too much acetaminophen, glutathione becomes depleted and NAPQI accumulates, binds with proteins to form adducts, and leads to necrosis of hepatocytes (Figure 1).9,10

Acetylcysteine, used in treating acetaminophen toxicity, is a substrate for glutathione synthesis and ultimately increases the amount of glutathione available to bind NAPQI and prevent damage to hepatocytes.11

Acetaminophen is a dose-related toxin. Most ingestions leading to acute liver failure exceed 10 g/day (> 150 mg/kg/day). Moderate chronic ingestion, eg, 4 g/day, usually leads to transient mild elevation of liver enzymes in healthy individuals12 but can in rare cases cause acute liver failure.13

Whitcomb and Block14 retrospectively identified 49 patients who presented with acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in 1987 through 1993; 21 (43%) had been taking acetaminophen for therapeutic purposes. All 49 patients took more than the recommended limit of 4 g/day, many of them while fasting and some while using alcohol. Acute liver failure was seen with ingestion of more than 12 g/day—or more than 10 g/day in alcohol users. The authors attributed the increased risk to activation of cytochrome P450 2E1 by alcohol and depletion of glutathione stores by starvation or alcohol abuse.

Advice to patients taking acetaminophen is given in Table 1.

Other drugs and supplements

A number of other drugs and herbal supplements can also cause acute liver failure (Table 2), the most common being antimicrobial and antiepileptic drugs.15 Of the antimicrobials, antitubercular drugs (especially isoniazid) are believed to be the most common causes, followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Phenytoin is the antiepileptic drug most often implicated in acute liver failure.

Statins can also cause acute liver failure, especially when combined with other hepatotoxic agents.16

The herbal supplements and weight-loss agents Hydroxycut and Herbalife have both been reported to cause acute liver failure, with patients presenting with either the hepatocellular or the cholestatic pattern of liver injury.17 The exact chemical in these supplements that causes liver injury has not yet been determined.

The National Institutes of Health maintains a database of cases of liver failure due to medications and supplements at livertox.nih.gov. The database includes the pattern of hepatic injury, mechanism of injury, management, and outcomes.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis B virus is the most common viral cause of acute liver failure and is responsible for about 8% of cases.18

Patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection—as evidenced by positive hepatitis B surface antigen—can develop acute liver failure if the infection is reactivated by the use of immunosuppressive drugs for solid-organ or bone-marrow transplant or medications such as anti-tumor necrosis agents, rituximab, or chemotherapy. These patients should be treated prophylactically with a nucleoside analogue, which should be continued for 6 months after immunosuppressive therapy is completed.

Hepatitis A virus is responsible for about 4% of cases.18

Hepatitis C virus rarely causes acute liver failure, especially in the absence of hepatitis A and hepatitis B.3,19

Hepatitis E virus, which is endemic in areas of Asia and Africa, can cause liver disease in pregnant women and in young adults who have concomitant liver disease from another cause. It tends to cause acute liver failure more frequently in pregnant women than in the rest of the population and carries a mortality rate of more than 20% in this subgroup.

TT (transfusion-transmitted) virus was reported in the 1990s to cause acute liver failure in about 27% of patients in whom no other cause could be found.20

Other rare viral causes of acute liver failure include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus types 1, 2, and 6.

Other causes

Other causes of acute liver failure include ischemic hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets) syndrome.

MANY PATIENTS NEED LIVER TRANSPLANT

Many patients with acute liver failure ultimately require orthotopic liver transplant,21 especially if they present with severe encephalopathy. Other aspects of treatment vary according to the cause of liver failure (Table 3).

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT

Management of acetaminophen toxicity

If the time of ingestion is known, checking the acetaminophen level can help determine the cause of acute liver failure and also predict the risk of hepatotoxicity, based on the work of Rumack and Matthew.22 Calculators are available, eg, http://reference.medscape.com/calculator/acetaminophen-toxicity.

If a patient presents with acute liver failure several days after ingesting acetaminophen, the level can be in the nontoxic range, however. In this scenario, measuring acetaminophen-protein adducts can help establish acetaminophen toxicity as the cause, as the adducts last longer in the serum and provide 100% sensitivity and specificity.23 While most laboratories can rapidly measure acetaminophen levels, only a few can measure acetaminophen-protein adducts, and thus this test is not used clinically.

Acetylcysteine is the main drug used for acetaminophen toxicity. Ideally, it should be given within 8 hours of acetaminophen ingestion, but giving it later is also useful.1

Acetylcysteine is available in oral and intravenous forms, the latter for patients who have encephalopathy or cannot tolerate oral intake due to repeated episodes of vomiting.24,25 The oral form is much less costly and is thus preferred over intravenous acetylcysteine in patients who can tolerate oral intake. Intravenous acetylcysteine should be given in a loading dose of 150 mg/kg in 5% dextrose over 15 minutes, followed by a maintenance dose of 50 mg/kg over 4 hours and then 100 mg/kg given over 16 hours.1 No dose adjustment is needed in patients who have renal toxicity (acetaminophen can also be toxic to the kidneys).

Most patients with acetaminophen-induced liver failure survive with medical management alone and do not need a liver transplant.3,26 Cirrhosis does not occur in these patients.

Management of viral acute liver failure

When patients present with acute liver failure, it is necessary to look for a viral cause by serologic testing, including hepatitis A virus IgM antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and hepatitis B core IgM antibody.

Hepatitis B can become reactivated in immunocompromised patients, and therefore the hepatitis B virus DNA level should be checked. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA in a patient previously known to have undetectable hepatitis B virus DNA confirms hepatitis B reactivation.

Patients with hepatitis B-induced acute liver failure should be treated with entecavir or tenofovir. Although this treatment may not change the course of acute liver failure or accelerate the recovery, it can prevent reinfection in the transplanted liver if liver transplant becomes indicated.27–29

Herpes simplex virus should be suspected in patients presenting with anicteric hepatitis with fever. Polymerase chain reaction testing for herpes simplex virus should be done,30 and if positive, patients should be given intravenous acyclovir.31 Despite treatment, herpes simplex virus disease is associated with a very poor prognosis without liver transplant.

Autoimmune hepatitis

The autoantibodies usually seen in autoimmune hepatitis are antinuclear antibody, antismooth muscle antibody, and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, and patients need to be tested for them.

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis can be challenging, as these autoimmune markers can be negative in 5% of patients. Liver biopsy becomes essential to establish the diagnosis in that setting.32

Guidelines advise starting prednisone 40 to 60 mg/day and placing the patient on the liver transplant list.1

Wilson disease

Although it is an uncommon cause of liver failure, Wilson disease needs special attention because it has a poor prognosis. The mortality rate in acute liver failure from Wilson disease reaches 100% without liver transplant.

Wilson disease is caused by a genetic defect that allows copper to accumulate in the liver and other organs. However, diagnosing Wilson disease as the cause of acute liver failure can be challenging because elevated serum and urine copper levels are not specific to Wilson disease and can be seen in patients with acute liver failure from any cause. In addition, the ceruloplasmin level is usually normal or high because it is an acute-phase reactant. Accumulation of copper in the liver parenchyma is usually patchy; therefore, qualitative copper staining on random liver biopsy samples provides low diagnostic yield. Quantitative copper on liver biopsy is the gold standard test to establish the diagnosis, but the test is time-consuming. Kayser-Fleischer rings around the iris are considered pathognomic for Wilson disease when seen with acute liver failure, but they are seen in only about 50% of patients.33

A unique feature of acute Wilson disease is that most patients have very high bilirubin levels and low alkaline phosphatase levels. An alkaline phosphatase-to-bilirubin ratio less than 2 in patients with acute liver failure is highly suggestive of Wilson disease.34

Another clue to the diagnosis is that patients with Wilson disease tend to develop Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia, which leads to a disproportionate elevation in aminotransferase levels, with aspartate aminotransferase being higher than alanine aminotransferase.

Once Wilson disease is suspected, the patient should be listed for liver transplant because death is almost certain without it. For patients awaiting liver transplant, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines recommend certain measures to lower the serum copper level such as albumin dialysis, continuous hemofiltration, plasmapheresis, and plasma exchange,1 but the evidence supporting their use is limited.

NONSPECIFIC MANAGEMENT

Acute liver failure can affect a number of organs and systems in addition to the liver (Figure 2).

General considerations

Because their condition can rapidly deteriorate, patients with acute liver failure are best managed in intensive care.

Patients who present to a center that does not have the facilities for liver transplant should be transferred to a transplant center as soon as possible, preferably by air. If the patient may not be able to protect the airway, endotracheal intubation should be performed before transfer.

The major causes of death in patients with acute liver failure are cerebral edema and infection. Gastrointestinal bleeding was a major cause of death in the past, but with prophylactic use of histamine H2 receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors, the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding has been significantly reduced.

Although initially used only in patients with acetaminophen-induced liver failure, acetylcysteine has also shown benefit in patients with acute liver failure from other causes. In patients with grade 1 or 2 encephalopathy on a scale of 0 (minimal) to 4 (comatose), the transplant-free survival rate is higher when acetylcysteine is given compared with placebo, but this benefit does not extend to patients with a higher grade of encephalopathy.35

Cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension

Cerebral edema is the leading cause of death in patients with acute liver failure, and it develops in nearly 40% of patients.36

The mechanism by which cerebral edema develops is not well understood. Some have proposed that ammonia is converted to glutamine, which causes cerebral edema either directly by its osmotic effect37,38 or indirectly by decreasing other osmolytes, thereby promoting water retention.39

Cerebral edema leads to intracranial hypertension, which can ultimately cause cerebral herniation and death. Because of the high mortality rate associated with cerebral edema, invasive devices were extensively used in the past to monitor intracranial pressure. However, in light of known complications of these devices, including bleeding,40 and lack of evidence of long-term benefit in terms of mortality rates, their use has come under debate.

Treatments. Many treatments are available for cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension. The first step is to elevate the head of the bed about 30 degrees. In addition, hyponatremia should be corrected, as it can worsen cerebral edema.41 If patients are intubated, maintaining a hypercapneic state is advisable to decrease the intracranial pressure.

Of the two pharmacologic options, mannitol is more often used.42 It is given as a bolus dose of 0.5 to 1 g/kg intravenously if the serum osmolality is less than 320 mOsm/L.1 Given the risk of fluid overload with mannitol, caution must be exercised in patients with renal dysfunction. The other pharmacologic option is 3% hypertonic saline.

Therapeutic hypothermia is a newer treatment for cerebral edema. Lowering the body temperature to 32 to 33°C (89.6 to 91.4°F) using cooling blankets decreases intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow and improves the cerebral perfusion pressure.43 With this treatment, patients should be closely monitored for side effects of infection, coagulopathy, and cardiac arrythmias.1

l-ornithine l-aspartate was successfully used to prevent brain edema in rats, but in humans, no benefit was seen compared with placebo.44,45 The underlying basis for this experimental treatment is that supplemental ornithine and aspartate should increase glutamate synthesis, which should increase the activity of enzyme glutamine synthetase in skeletal muscles. With the increase in enzyme activity, conversion of ammonia to glutamine should increase, thereby decreasing ammonia circulation and thus decreasing cerebral edema.

Patients with cerebral edema have a high incidence of seizures, but prophylactic antiseizure medications such as phenytoin have not been proven to be beneficial.46

Infection

Nearly 80% of patients with acute liver failure develop an infectious complication, which can be attributed to a state of immunodeficiency.47

The respiratory and urinary tracts are the most common sources of infection.48 In patients with bacteremia, Enterococcus species and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species49 are the commonly isolated organisms. Also, in patients with acute liver failure, fungal infections account for 30% of all infections.50

Infected patients often develop worsening of their encephalopathy51 without fever or elevated white blood cell count.49,52 Thus, in any patient in whom encephalopathy is worsening, an evaluation must be done to rule out infection. In these patients, systemic inflammatory response syndrome is an independent risk factor for death.53

Despite the high mortality rate with infection, whether using antibiotics prophylactically in acute liver failure is beneficial is controversial.54,55

Gastrointestinal bleeding

The current prevalence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in acute liver failure patients is about 1.5%.56 Coagulopathy and endotracheal intubation are the main risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in these patients.57 The most common source of bleeding is stress ulcers in the stomach. The ulcers develop from a combination of factors, including decreased blood flow to the mucosa causing ischemia and hypoperfusion-reperfusion injury.

Pharmacologic inhibition of gastric acid secretion has been shown to reduce upper gastrointestinal bleeding in acute liver failure. A histamine H2 receptor blocker or proton pump inhibitor should be given to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute liver failure.1,58

EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENTS

Artificial liver support systems

Membranes and dialysate solutions have been developed to remove toxic substances that are normally metabolized by the liver. Two of these—the molecular adsorbent recycling system (MARS) and the extracorporeal liver assist device (ELAD)—were developed in the late 1990s. MARS consisted of a highly permeable hollow fiber membrane mixed with albumin, and ELAD consisted of porcine hepatocytes attached to microcarriers in the extracapillary space of the hollow fiber membrane. Both systems allowed for transfer of water-soluble and protein-bound toxins in the blood across the membrane and into the dialysate.59 The clinical benefit offered by these devices is controversial,60–62 thus limiting their use to experimental purposes only.

Hepatocyte transplant

Use of hepatocyte transplant as a bridge to liver transplant was tested in 1970s, first in rats and later in humans.63 By reducing the blood ammonia level and improving cerebral perfusion pressure and cardiac function, replacement of 1% to 2% of the total liver cell mass by transplanted hepatocytes acts as a bridge to orthotopic liver transplant.64,65

PROGNOSIS

Different criteria have been used to identify patients with poor prognosis who may eventually need to undergo liver transplant.

The King’s College criteria system is the most commonly used for prognosis (Table 4).37,66–69 Its main drawback is that it is applicable only in patients with encephalopathy, and when patients reach this stage, their condition often deteriorates rapidly, and they die while awaiting liver transplant.37,66,67

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is an alternative to the King’s College criteria. A high MELD score on admission signifies advanced disease, and patients with a high MELD score tend to have a worse prognosis than those with a low score.68

The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score can also be used, as it is more sensitive than the King’s College criteria.6

The Clichy criteria66,69 can also be used.

Liver biopsy. In addition to helping establish the cause of acute liver failure, liver biopsy can also be used as a prognostic tool. Hepatocellular necrosis greater than 70% on the biopsy predicts death with a specificity of 90% and a sensitivity of 56%.70

Hypophosphatemia has been reported to indicate recovering liver function in patients with acute liver failure.71 As the liver regenerates, its energy requirement increases. To supply the energy, adenosine triphosphate production increases, and phosphorus shifts from the extracellular to the intracellular compartment to meet the need for extra phosphorus during this process. A serum phosphorus level of 2.9 mg/dL or higher appears to indicate a poor prognosis in patients with acute liver failure, as it signifies that adequate hepatocyte regeneration is not occurring.

- Polson J, Lee WM; American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology 2005; 41:1179–1197.

- O’Grady JG, Schalm SW, Williams R. Acute liver failure: redefining the syndromes. Lancet 1993; 342:273–275.

- Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, et al; US Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:947–954.

- Lee WM, Squires RH Jr, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: summary of a workshop. Hepatology 2008; 47:1401–1415.

- Acharya SK, Panda SK, Saxena A, Gupta SD. Acute hepatic failure in India: a perspective from the East. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 15:473–479.

- Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 2005; 42:1364–1372.

- Patten CJ, Thomas PE, Guy RL, et al. Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in acetaminophen activation by rat and human liver microsomes and their kinetics. Chem Res Toxicol 1993; 6:511–518.

- Chen W, Koenigs LL, Thompson SJ, et al. Oxidation of acetaminophen to its toxic quinone imine and nontoxic catechol metabolites by baculovirus-expressed and purified human cytochromes P450 2E1 and 2A6. Chem Res Toxicol 1998; 11:295-301.

- Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. IV. Protective role of glutathione. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1973; 187:211–217.

- Schilling A, Corey R, Leonard M, Eghtesad B. Acetaminophen: old drug, new warnings. Cleve Clin J Med 2010; 77:19–27.

- Lauterburg BH, Corcoran GB, Mitchell JR. Mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine in the protection against the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in rats in vivo. J Clin Invest 1983; 71:980–991.