User login

In reply: Acute liver failure

In Reply: We thank Dr. Homler for bringing hepatitis D as a potential cause of acute liver failure to our attention.

Hepatitis D virus, first described in the 1970s, requires the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) capsid to enter the hepatocyte and, thus, can only cause liver injury when the patient is also infected simultaneously with hepatitis B virus.1 Hepatitis D virus can cause either coinfection (presence of immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody with or without HBsAg) or superinfection (presence of HBsAg without immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody) with hepatitis B virus. In India, coinfection has been reported to be the cause of acute liver failure in about 4% of all patients, and superinfection in 4.5%.2

While simultaneous treatment for hepatitis D and B viruses with pegylated interferon and any of the agents used for treatment of hepatitis B has been successful in treating chronic hepatitis, it has not been proven useful in patients with acute liver failure, and liver transplant remains the only treatment option.3

- Rizzetto M. The adventure of delta. Liver Int 2016; 36(suppl 1):135–140.

- Irshad M, Acharya SK. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection in severe forms of liver diseases in North India. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8:995–998.

- Noureddin M, Gish R. Hepatitis delta: epidemiology, diagnosis and management 36 years after discovery. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16:365.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Homler for bringing hepatitis D as a potential cause of acute liver failure to our attention.

Hepatitis D virus, first described in the 1970s, requires the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) capsid to enter the hepatocyte and, thus, can only cause liver injury when the patient is also infected simultaneously with hepatitis B virus.1 Hepatitis D virus can cause either coinfection (presence of immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody with or without HBsAg) or superinfection (presence of HBsAg without immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody) with hepatitis B virus. In India, coinfection has been reported to be the cause of acute liver failure in about 4% of all patients, and superinfection in 4.5%.2

While simultaneous treatment for hepatitis D and B viruses with pegylated interferon and any of the agents used for treatment of hepatitis B has been successful in treating chronic hepatitis, it has not been proven useful in patients with acute liver failure, and liver transplant remains the only treatment option.3

In Reply: We thank Dr. Homler for bringing hepatitis D as a potential cause of acute liver failure to our attention.

Hepatitis D virus, first described in the 1970s, requires the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) capsid to enter the hepatocyte and, thus, can only cause liver injury when the patient is also infected simultaneously with hepatitis B virus.1 Hepatitis D virus can cause either coinfection (presence of immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody with or without HBsAg) or superinfection (presence of HBsAg without immunoglobulin M anti-HB core antibody) with hepatitis B virus. In India, coinfection has been reported to be the cause of acute liver failure in about 4% of all patients, and superinfection in 4.5%.2

While simultaneous treatment for hepatitis D and B viruses with pegylated interferon and any of the agents used for treatment of hepatitis B has been successful in treating chronic hepatitis, it has not been proven useful in patients with acute liver failure, and liver transplant remains the only treatment option.3

- Rizzetto M. The adventure of delta. Liver Int 2016; 36(suppl 1):135–140.

- Irshad M, Acharya SK. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection in severe forms of liver diseases in North India. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8:995–998.

- Noureddin M, Gish R. Hepatitis delta: epidemiology, diagnosis and management 36 years after discovery. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16:365.

- Rizzetto M. The adventure of delta. Liver Int 2016; 36(suppl 1):135–140.

- Irshad M, Acharya SK. Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection in severe forms of liver diseases in North India. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8:995–998.

- Noureddin M, Gish R. Hepatitis delta: epidemiology, diagnosis and management 36 years after discovery. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014; 16:365.

In reply: Alcoholic hepatitis: An important consideration

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov for his interest in our article1 and for his comments on the importance of infection evaluation and treatment in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. We agree with the points he has raised and emphasized several of them in our article. We highlighted the need to evaluate for infections in these patients, as about a quarter of them are infected at the time of presentation.2

Importantly, patients with alcoholic hepatitis frequently have systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, which can be related to the overall inflammatory state of the disease itself or can reflect an active bacterial infection. Therefore, clinical monitoring for symptoms and signs of infection is crucial, and screening for infections is warranted on admission as well as repeatedly during the hospital stay for patients who experience clinical deterioration.3 Obtaining blood and urine cultures and performing paracentesis in patients with ascites to evaluate for bacterial peritonitis are required. Indeed, infections are a leading cause of death in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, both directly and indirectly by predisposing to multiorgan failure.4

Another factor to consider is the increased susceptibility to infection in these patients treated with corticosteroids. A study by Louvet et al2 showed that nonresponse to corticosteroids is the main factor contributing to the development of infection during treatment with corticosteroids, suggesting that infection is likely a consequence of the absence of improvement in liver function. More recently, results of the Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis trial (which evaluated the treatment effect of prednisolone and pentoxifylline in the management of severe alcoholic hepatitis) showed that despite the higher rates of infections in patients treated with prednisolone, the mortality rates attributed to infections were similar across the treatment groups, regardless of whether prednisolone was administered.4

Finally, it is important to emphasize that criteria to initiate empiric antibiotics in patients with alcoholic hepatitis are currently lacking, and the decision to start antibiotics empirically in patients without a clear infection is largely based on the clinician’s assessment.

- Dugum M, Zein N, McCullough A, Hanouneh I. Alcoholic hepatitis: challenges in diagnosis and management. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:226–236.

- Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:541–548.

- European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012; 57:399–420.

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1619–1628.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov for his interest in our article1 and for his comments on the importance of infection evaluation and treatment in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. We agree with the points he has raised and emphasized several of them in our article. We highlighted the need to evaluate for infections in these patients, as about a quarter of them are infected at the time of presentation.2

Importantly, patients with alcoholic hepatitis frequently have systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, which can be related to the overall inflammatory state of the disease itself or can reflect an active bacterial infection. Therefore, clinical monitoring for symptoms and signs of infection is crucial, and screening for infections is warranted on admission as well as repeatedly during the hospital stay for patients who experience clinical deterioration.3 Obtaining blood and urine cultures and performing paracentesis in patients with ascites to evaluate for bacterial peritonitis are required. Indeed, infections are a leading cause of death in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, both directly and indirectly by predisposing to multiorgan failure.4

Another factor to consider is the increased susceptibility to infection in these patients treated with corticosteroids. A study by Louvet et al2 showed that nonresponse to corticosteroids is the main factor contributing to the development of infection during treatment with corticosteroids, suggesting that infection is likely a consequence of the absence of improvement in liver function. More recently, results of the Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis trial (which evaluated the treatment effect of prednisolone and pentoxifylline in the management of severe alcoholic hepatitis) showed that despite the higher rates of infections in patients treated with prednisolone, the mortality rates attributed to infections were similar across the treatment groups, regardless of whether prednisolone was administered.4

Finally, it is important to emphasize that criteria to initiate empiric antibiotics in patients with alcoholic hepatitis are currently lacking, and the decision to start antibiotics empirically in patients without a clear infection is largely based on the clinician’s assessment.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Mirrakhimov for his interest in our article1 and for his comments on the importance of infection evaluation and treatment in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. We agree with the points he has raised and emphasized several of them in our article. We highlighted the need to evaluate for infections in these patients, as about a quarter of them are infected at the time of presentation.2

Importantly, patients with alcoholic hepatitis frequently have systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, which can be related to the overall inflammatory state of the disease itself or can reflect an active bacterial infection. Therefore, clinical monitoring for symptoms and signs of infection is crucial, and screening for infections is warranted on admission as well as repeatedly during the hospital stay for patients who experience clinical deterioration.3 Obtaining blood and urine cultures and performing paracentesis in patients with ascites to evaluate for bacterial peritonitis are required. Indeed, infections are a leading cause of death in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, both directly and indirectly by predisposing to multiorgan failure.4

Another factor to consider is the increased susceptibility to infection in these patients treated with corticosteroids. A study by Louvet et al2 showed that nonresponse to corticosteroids is the main factor contributing to the development of infection during treatment with corticosteroids, suggesting that infection is likely a consequence of the absence of improvement in liver function. More recently, results of the Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis trial (which evaluated the treatment effect of prednisolone and pentoxifylline in the management of severe alcoholic hepatitis) showed that despite the higher rates of infections in patients treated with prednisolone, the mortality rates attributed to infections were similar across the treatment groups, regardless of whether prednisolone was administered.4

Finally, it is important to emphasize that criteria to initiate empiric antibiotics in patients with alcoholic hepatitis are currently lacking, and the decision to start antibiotics empirically in patients without a clear infection is largely based on the clinician’s assessment.

- Dugum M, Zein N, McCullough A, Hanouneh I. Alcoholic hepatitis: challenges in diagnosis and management. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:226–236.

- Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:541–548.

- European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012; 57:399–420.

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1619–1628.

- Dugum M, Zein N, McCullough A, Hanouneh I. Alcoholic hepatitis: challenges in diagnosis and management. Cleve Clin J Med 2015; 82:226–236.

- Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:541–548.

- European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012; 57:399–420.

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1619–1628.

Alcoholic hepatitis: Challenges in diagnosis and management

Alcoholic hepatitis, a severe manifestation of alcoholic liver disease, is rising in incidence. Complete abstinence from alcohol remains the cornerstone of treatment, while other specific interventions aim to decrease short-term mortality rates.

Despite current treatments, about 25% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis eventually die of it. For those who survive hospitalization, measures need to be taken to prevent recidivism. Although liver transplantation seems to hold promise, early transplantation is still largely experimental in alcoholic hepatitis and will likely be available to only a small subset of patients, especially in view of ethical issues and the possible wider implications for transplant centers.

New treatments will largely depend on a better understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology, and future clinical trials should evaluate therapies that improve short-term as well as long-term outcomes.

ACUTE HEPATIC DECOMPENSATION IN A HEAVY DRINKER

Excessive alcohol consumption is very common worldwide, is a major risk factor for liver disease, and is a leading cause of preventable death. Alcoholic cirrhosis is the eighth most common cause of death in the United States and in 2010 was responsible for nearly half of cirrhosis-related deaths worldwide.1

Alcoholic liver disease is a spectrum. Nearly all heavy drinkers (ie, those consuming 40 g or more of alcohol per day, Table 1) have fatty liver changes, 20% to 40% develop fibrosis, 10% to 20% progress to cirrhosis, and of those with cirrhosis, 1% to 2% are diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma every year.2

Within this spectrum, alcoholic hepatitis is a well-defined clinical syndrome characterized by acute hepatic decompensation that typically results from long-standing alcohol abuse. Binge drinkers may also be at risk for alcoholic hepatitis, but good data on the association between drinking patterns and the risk of alcoholic hepatitis are limited.

Alcoholic hepatitis varies in severity from mild to life-threatening.3 Although its exact incidence is unknown, its prevalence in alcoholics has been estimated at 20%.4 Nearly half of patients with alcoholic hepatitis have cirrhosis at the time of their acute presentation, and these patients generally have a poor prognosis, with a 28-day death rate as high as 50% in severe cases.5,6 Moreover, although alcoholic hepatitis develops in only a subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease, hospitalizations for it are increasing in the United States.7

Women are at higher risk of developing alcoholic hepatitis, an observation attributed to the effect of estrogens on oxidative stress and inflammation, lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase levels resulting in slower first-pass metabolism of alcohol, and higher body fat content causing a lower volume of distribution for alcohol than in men.8 The incidence of alcoholic hepatitis is also influenced by a number of demographic and genetic factors as well as nutritional status and coexistence of other liver diseases.9 Most patients diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis are active drinkers, but it can develop even after significantly reducing or stopping alcohol consumption.

FATTY ACIDS, ENZYMES, CYTOKINES, INFLAMMATION

Alcohol consumption induces fatty acid synthesis and inhibits fatty acid oxidation, thereby promoting fat deposition in the liver.

The major enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism are cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and alcohol dehydrogenase. CYP2E1 is inducible and is up-regulated when excess alcohol is ingested, while alcohol dehydrogen-

ase function is relatively stable. Oxidative degradation of alcohol by these enzymes generates reactive oxygen species and acetaldehyde, inducing liver injury.10 Interestingly, it has been proposed that variations in the genes for these enzymes influence alcohol consumption and dependency as well as alcohol-driven tissue damage.

In addition, alcohol disrupts the intestinal mucosal barrier, allowing lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria to travel to the liver via the portal vein. These lipopolysaccharides then bind to and activate sinusoidal Kupffer cells, leading to production of several cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and transforming growth factor beta. These cytokines promote hepatocyte inflammation, apoptosis, and necrosis (Figure 1).11

Besides activating the innate immune system, the reactive oxygen species resulting from alcohol metabolism interact with cellular components, leading to production of protein adducts. These act as antigens that activate the adaptive immune response, followed by B- and T-lymphocyte infiltration, which in turn contribute to liver injury and inflammation.12

THE DIAGNOSIS IS MAINLY CLINICAL

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis is mainly clinical. In its usual presentation, jaundice develops rapidly in a person with a known history of heavy alcohol use. Other symptoms and signs may include ascites, encephalopathy, and fever. On examination, the liver may be enlarged and tender, and a hepatic bruit has been reported.13

Other classic signs of liver disease such as parotid enlargement, Dupuytren contracture, dilated abdominal wall veins, and spider nevi can be present, but none is highly specific or sensitive for alcoholic hepatitis.

Elevated liver enzymes and other clues

Laboratory tests are important in evaluating potential alcoholic hepatitis, although no single laboratory marker can definitively establish alcohol as the cause of liver disease. To detect alcohol consumption, biochemical markers such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), mean corpuscular volume, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, and, more commonly, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase are used.

In the acute setting, typical biochemical derangements in alcoholic hepatitis include elevated AST (up to 2 to 6 times the upper limit of normal; usually less than 300 IU/L) and elevated ALT to a lesser extent,14 with an AST-to-ALT ratio greater than 2. Neutrophilia, anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy with an elevated international normalized ratio are common.

Patients with alcoholic hepatitis are also prone to develop bacterial infections, and about 7% develop hepatorenal syndrome, itself an ominous sign.15

Imaging studies are valuable in excluding other causes of abnormal liver test results in patients who abuse alcohol, such as biliary obstruction, infiltrative liver diseases, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Screen for alcohol intake

During the initial evaluation of suspected alcoholic hepatitis, one should screen for excessive drinking. In a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, only one of six US adults, including binge drinkers, said they had ever discussed alcohol consumption with a health professional.16 Many patients with alcoholic liver disease in general and alcoholic hepatitis in particular deny alcohol abuse or underreport their intake.17

Screening tests such as the CAGE questionnaire and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test can be used to assess alcohol dependence or abuse.18,19 The CAGE questionnaire consists of four questions:

- Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

- Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt guilty about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (an eye-opener) to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

A yes answer to two or more questions is considered clinically significant.

Is liver biopsy always needed?

Although alcoholic hepatitis can be suspected on the basis of clinical and biochemical clues, liver biopsy remains the gold standard diagnostic tool. It confirms the clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis in about 85% of all patients and in up to 95% when significant hyperbilirubinemia is present.20

However, whether a particular patient needs a biopsy is not always clear. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends biopsy in patients who have a clinical diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis for whom medical treatment is being considered and in those with an uncertain underlying diagnosis.

Findings on liver biopsy in alcoholic hepatitis include steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, neutrophilic infiltration, Mallory bodies (which represent aggregated cytokeratin intermediate filaments and other proteins), and scarring with a typical perivenular distribution as opposed to the periportal fibrosis seen in chronic viral hepatitis. Some histologic findings, such as centrilobular necrosis, may overlap alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

In addition to confirming the diagnosis and staging the disease, liver biopsy has prognostic value. The severity of inflammation and cholestatic changes correlates with poor prognosis and may also predict response to corticosteroid treatment in severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis.21

However, the utility of liver biopsy in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the prognosis of alcoholic hepatitis is controversial for several reasons. Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and ascites are all common in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, often making percutaneous liver biopsy contraindicated. Trans-

jugular liver biopsy is not universally available outside tertiary care centers.

Needed is a minimally invasive test for assessing this disease. Breath analysis might be such a test, offering a noninvasive means to study the composition of volatile organic compounds and elemental gases and an attractive method to evaluate health and disease in a patient-friendly manner. Our group devised a model based on breath levels of trimethylamine and pentane. When we tested it, we found that it distinguishes patients with alcoholic hepatitis from those with acute liver decompensation from causes other than alcohol and controls without liver disease with up to 90% sensitivity and 80% specificity.22

ASSESSING THE SEVERITY OF ALCOHOLIC HEPATITIS

Several models have been developed to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and guide treatment decisions (Table 2).

The MDF (Maddrey Discriminant Function)6 system was the first scoring system developed and is still the most widely used. A score of 32 or higher indicates severe alcoholic hepatitis and has been used as the threshold for starting treatment with corticosteroids.6

The MDF has limitations. Patients with a score lower than 32 are considered not to have severe alcoholic hepatitis, but up to 17% of them still die. Also, since it uses the prothrombin time, its results can vary considerably among laboratories, depending on the sensitivity of the thromboplastin reagent used.

The MELD (Model for End-stage Liver Disease) score. Sheth et al23 compared the MELD and the MDF scores in assessing the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. They found that the MELD performed as well as the MDF in predicting 30-day mortality. A MELD score of greater than 11 had a sensitivity in predicting 30-day mortality of 86% and a specificity of 81%, compared with 86% and 48%, respectively, for MDF scores greater than 32.

Another study found a MELD score of 21 to have the highest sensitivity and specificity in predicting mortality (an estimated 90-day death rate of 20%). Thus, a MELD score of 21 is an appropriate threshold for prompt consideration of specific therapies such as corticosteroids.24

The MELD score has become increasingly important in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, as some of them may become candidates for liver transplantation (see below). Also, serial MELD scores in hospitalized patients have prognostic implications, since an increase of 2 or more points in the first week has been shown to predict in-hospital mortality.25

The GAHS (Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score)26 was shown to identify patients with alcoholic hepatitis who have an especially poor prognosis and need corticosteroid therapy. In those with a GAHS of 9 or higher, the 28-day survival rate was 78% with corticosteroid treatment and 52% without corticosteroid treatment; survival rates at 84 days were 59% and 38%, respectively.26

The ABIC scoring system (Age, Serum Bilirubin, INR, and Serum Creatinine) stratifies patients by risk of death at 90 days27:

- Score less than 6.71: low risk (100% survival)

- A score 6.71–8.99: intermediate risk (70% survival)

- A score 9.0 or higher: high risk (25% survival).

Both the GAHS and ABIC score are limited by lack of external validation.

The Lille score.28 While the above scores are used to identify patients at risk of death from alcoholic hepatitis and to decide on starting corticosteroids, the Lille score is designed to assess response to corticosteroids after 1 week of treatment. It is calculated based on five pretreatment variables and the change in serum bilirubin level at day 7 of corticosteroid therapy. Lille scores range from 0 to 1; a score higher than 0.45 is associated with a 75% mortality rate at 6 months and indicates a lack of response to corticosteroids and that these drugs should be discontinued.28

MANAGEMENT

Supportive treatment

Abstinence from alcohol is the cornerstone of treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Early management of alcohol abuse or dependence is, therefore, warranted in all patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Referral to addiction specialists, motivational therapies, and anticraving drugs such as baclofen can be utilized.

Treat alcohol withdrawal. Alcoholics who suddenly decrease or discontinue their alcohol use are at high risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Within 24 hours after the last drink, patients can experience increases in their heart rate and blood pressure, along with irritability and hyperreflexia. Within the next few days, more dangerous complications including seizures and delirium tremens can arise.

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms should be treated with short-acting benzodiazepines or clomethiazole, keeping the risk of worsening encephalopathy in mind.29 If present, complications of cirrhosis such as encephalopathy, ascites, and variceal bleeding should be managed.

Nutritional support is important. Protein-calorie malnutrition is common in alcoholics, as are deficiencies of vitamin A, vitamin D, thiamine, folate, pyridoxine, and zinc.30 Although a randomized controlled trial comparing enteral nutrition (2,000 kcal/day) vs corticosteroids (prednisolone 40 mg/day) in patients with alcoholic hepatitis did not show any difference in the 28-day mortality rate, those who received nutritional support and survived the first month had a lower mortality rate than those treated with corticosteroids (8% vs 37%).31 A daily protein intake of 1.5 g per kilogram of body weight is therefore recommended, even in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.15

Combining enteral nutrition and corticosteroid treatment may have a synergistic effect but is yet to be investigated.

Screen for infection. Patients with alcoholic hepatitis should be screened for infection, as about 25% of those with severe alcoholic hepatitis have an infection at admission.32 Since many of these patients meet the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome, infections can be particularly difficult to diagnose. Patients require close clinical monitoring as well as regular pancultures for early detection. Antibiotics are frequently started empirically even though we lack specific evidence-based guidelines on this practice.33

Corticosteroids

Various studies have evaluated the role of corticosteroids in treating alcoholic hepatitis, differing considerably in sample populations, methods, and end points. Although the results of individual trials differ, meta-analyses indicate that corticosteroids have a moderate beneficial effect in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

For example, Rambaldi et al34 performed a meta-analysis that concluded the mortality rate was lower in alcoholic hepatitis patients with MDF scores of at least 32 or hepatic encephalopathy who were treated with corticosteroids than in controls (relative risk 0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.16–0.86).

Therefore, in the absence of contraindications, the AASLD recommends starting corticosteroids in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, defined as an MDF score of 32 or higher.21 The preferred agent is oral prednisolone 40 mg daily or parenteral methylprednisolone 32 mg daily for 4 weeks and then tapered over the next 2 to 4 weeks or abruptly discontinued. Because activation of prednisone is decreased in patients with liver disease, prednisolone (the active form) is preferred over prednisone (the inactive precursor).35 In alcoholic hepatitis, the number needed to treat with corticosteroids to prevent one death has been calculated36 at 5.

As mentioned, response to corticosteroids is commonly assessed at 1 week of treatment using the Lille score. A score higher than 0.45 predicts a poor response and should trigger discontinuation of corticosteroids, particularly in those classified as null responders (Lille score > 0.56).

Adverse effects of steroids include sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and steroid psychosis. Of note, patients who have evidence of hepatorenal syndrome or gastrointestinal bleeding tend to have a less favorable response to corticosteroids. Also, while infections were once considered a contraindication to steroid therapy, recent evidence suggests that steroid use might not be precluded in infected patients after appropriate antibiotic therapy. Infections occur in about a quarter of all alcoholic hepatitis patients treated with steroids, more frequently in null responders (42.5%) than in responders (11.1%), which supports corticosteroid discontinuance at 1 week in null responders.32

Pentoxifylline

An oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, pentoxifylline, also inhibits production of several cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha. At a dose of 400 mg orally three times daily for 4 weeks, pentoxifylline has been used in treating severe alcoholic hepatitis (MDF score ≥ 32) and is recommended especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated, as with sepsis.21

An early double-blind clinical trial randomized patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis to receive either pentoxifylline 400 mg orally three times daily or placebo. Of the patients who received pentoxifylline, 24.5% died during the index hospitalization, compared with 46.1% of patients who received placebo. This survival benefit was mainly related to a markedly lower incidence of hepatorenal syndrome as the cause of death in the pentoxifylline group than in the placebo group (50% vs 91.7% of deaths).37

In a small clinical trial in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, pentoxifylline recipients had a higher 3-month survival rate than prednisolone recipients (35.29% vs 14.71%, P = .04).38 However, a larger trial showed no improvement in 6-month survival with the combination of prednisolone and pentoxifylline compared with prednisolone alone (69.9% vs 69.2%, P = .91).39 Also, a meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials found no survival benefit with pentoxifylline therapy.40

Of note, in the unfortunate subgroup of patients who have a poor response to corticosteroids, no alternative treatment, including pentoxifylline, has been shown to be effective.41

Prednisone or pentoxifylline? Very recently, results of the Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) trial have been released.42 This is a large, multicenter, double-blinded clinical trial that aimed to provide a definitive answer to whether corticosteroids or pentoxifylline (or both) are beneficial in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The study included 1,103 adult patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (MDF score ≥ 32) who were randomized to monotherapy with prednisolone or pentoxifylline, combination therapy, or placebo. The primary end point was mortality at 28 days, and secondary end points included mortality at 90 days and at 1 year. Prednisolone reduced 28-day mortality by about 39%. In contrast, the 28-day mortality rate was similar in patients who received pentoxifylline and those who did not. Also, neither drug was significantly associated with a survival benefit beyond 28 days. The investigators concluded that pentoxifylline has no impact on disease progression and should not be used for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis.42

Other tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors not recommended

Two other tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, infliximab and etanercept, have been tested in clinical trials in alcoholic hepatitis. Unfortunately, the results were not encouraging, with no major reduction in mortality.43–45 In fact, these trials demonstrated a significantly increased risk of infections in the treatment groups. Therefore, these drugs are not recommended for treating alcoholic hepatitis.

A possible explanation is that tumor necrosis factor alpha plays an important role in liver regeneration, aiding in recovery from alcohol-induced liver injury, and inhibiting it can have deleterious consequences.

Other agents

A number of other agents have undergone clinical trials in alcoholic hepatitis.

N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant that replenishes glutathione stores in hepatocytes, was evaluated in a randomized clinical trial in combination with prednisolone.46 Although the 1-month mortality rate was significantly lower in the combination group than in the prednisolone-only group (8% vs 24%, P = .006), 3-month and 6-month mortality rates were not. Nonetheless, the rates of infection and hepatorenal syndrome were lower in the combination group. Therefore, corticosteroids and N-acetylcysteine may have synergistic effects, but the optimum duration of N-acetylcysteine therapy needs to be determined in further studies.

Vitamin E, silymarin, propylthiouracil, colchicine, and oxandrolone (an anabolic steroid) have also been studied, but with no convincing benefit.21

Role of liver transplantation

Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease has been a topic of great medical and social controversy. The view that alcoholic patients are responsible for their own illness led to caution when contemplating liver transplantation. Many countries require 6 months of abstinence from alcohol before placing a patient on the liver transplant list, posing a major obstacle to patients with alcoholic hepatitis, as almost all are active drinkers at the time of presentation and many will die within 6 months. Reasons for this 6-month rule include donor shortage and risk of recidivism.47

With regard to survival following alcoholic hepatitis, a study utilizing the United Network for Organ Sharing database matched patients with alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis who underwent liver transplantation. Rates of 5-year graft survival were 75% in those with alcoholic hepatitis and 73% in those with alcoholic cirrhosis (P = .97), and rates of patient survival were 80% and 78% (P = .90), respectively. Proportional regression analysis adjusting for other variables showed no impact of the etiology of liver disease on graft or patient survival. The investigators concluded that liver transplantation could be considered in a select group of patients with alcoholic hepatitis who do not improve with medical therapy.48

In a pivotal case-control prospective study,49 26 patients with Lille scores greater than 0.45 were listed for liver transplantation within a median of 13 days after nonresponse to medical therapy. The cumulative 6-month survival rate was higher in patients who received a liver transplant early than in those who did not (77% vs 23%, P < .001). This benefit was maintained through 2 years of follow-up (hazard ratio 6.08, P = .004). Of note, all these patients had supportive family members, no severe coexisting conditions, and a commitment to alcohol abstinence (although 3 patients resumed drinking after liver transplantation).49

Although these studies support early liver transplantation in carefully selected patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, the criteria for transplantation in this group need to be refined. Views on alcoholism also need to be reconciled, as strong evidence is emerging that implicates genetic and environmental influences on alcohol dependence.

Management algorithm

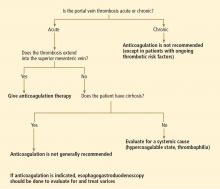

Figure 2 shows a suggested management algorithm for alcoholic hepatitis, adapted from the guidelines of the AASLD and European Association for the Study of the Liver.

NEW THERAPIES NEEDED

Novel therapies for severe alcoholic hepatitis are urgently needed to help combat this devastating condition. Advances in understanding its pathophysiology have uncovered several new therapeutic targets, and new agents are already being evaluated in clinical trials.

IMM 124-E, a hyperimmune bovine colostrum enriched with immunoglobulin G anti-lipopolysaccharide, is going to be evaluated in combination with prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Anakinra, an interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, has significant anti-inflammatory activity and is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. A clinical trial to evaluate its role in alcoholic hepatitis has been designed in which patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (defined as a MELD score ≥ 21) will be randomized to receive either methylprednisolone or a combination of anakinra, pentoxifylline, and zinc (a mineral that improves gut integrity).

Emricasan, an orally active caspase protease inhibitor, is another agent currently being tested in a phase 2 clinical trial in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Since caspases induce apoptosis, inhibiting them should theoretically dampen alcohol-induced hepatocyte injury.

Interleukin 22, a hepatoprotective cytokine, shows promise as a treatment and will soon be evaluated in alcoholic hepatitis.

- Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol 2013; 59:160–168.

- Teli MR, Day CP, Burt AD, Bennett MK, James OF. Determinants of progression to cirrhosis or fibrosis in pure alcoholic fatty liver. Lancet 1995; 346:987–990.

- Alcoholic liver disease: morphological manifestations. Review by an international group. Lancet 1981; 1:707–711.

- Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 1997; 25:108–111.

- Basra S, Anand BS. Definition, epidemiology and magnitude of alcoholic hepatitis. World J Hepatol 2011; 3:108–113.

- Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL Jr, Mezey E, White RI Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978; 75:193–199.

- Jinjuvadia R, Liangpunsakul S, for the Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment Consortium. Trends in alcoholic hepatitis-related hospitalizations, financial burden, and mortality in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014 Jun 25 (Epub ahead of print).

- Sato N, Lindros KO, Baraona E, et al. Sex difference in alcohol-related organ injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001; 25(suppl s1):40S–45S.

- Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Alcoholic hepatitis: current challenges and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:555–564.

- Seitz HK, Stickel F. Risk factors and mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis with special emphasis on alcohol and oxidative stress. Biol Chem 2006; 387:349–360.

- Thurman RG. II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of Kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am J Physiol 1998; 275:G605–G611.

- Duddempudi AT. Immunology in alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2012; 16:687–698.

- Lischner MW, Alexander JF, Galambos JT. Natural history of alcoholic hepatitis. I. The acute disease. Am J Dig Dis 1971; 16:481–494.

- Cohen JA, Kaplan MM. The SGOT/SGPT ratio—an indicator of alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci 1979; 24:835–838.

- Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2758–2769.

- McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use—44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:16–22.

- Grant BF. Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. J Stud Alcohol 1997; 58:365–371.

- Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004; 57:30–39.

- The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Second Edition. World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2001/who_msd_msb_01.6a.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2015.

- Hamid R, Forrest EH. Is histology required for the diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis? A review of published randomised controlled trials. Gut 2011; 60(suppl 1):A233.

- O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ; Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2010; 51:307–328.

- Hanouneh IA, Zein NN, Cikach F, et al. The breathprints in patients with liver disease identify novel breath biomarkers in alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:516–523.

- Sheth M, Riggs M, Patel T. Utility of the Mayo End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score in assessing prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2002; 2:2.

- Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, et al. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2005; 41:353–358.

- Srikureja W, Kyulo NL, Runyon BA, Hu KQ. MELD score is a better prognostic model than Child-Turcotte-Pugh score or Discriminant Function score in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 2005; 42:700–706.

- Forrest EH, Morris AJ, Stewart S, et al. The Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score identifies patients who may benefit from corticosteroids. Gut 2007; 56:1743–1746.

- Dominguez M, Rincón D, Abraldes JG, et al. A new scoring system for prognostic stratification of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103:2747–2756.

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology 2007; 45:1348–1354.

- Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al; Working Group on the Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium, Practice Guidelines Committee, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:1405–1412.

- Mezey E. Interaction between alcohol and nutrition in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 1991; 11:340–348.

- Cabré E, Rodríguez-Iglesias P, Caballería J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology 2000; 32:36–42.

- Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:541–548.

- European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2012; 57:399–420.

- Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis—a Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:1167–1178.

- Powell LW, Axelsen E. Corticosteroids in liver disease: studies on the biological conversion of prednisone to prednisolone and plasma protein binding. Gut 1972; 13:690–696.

- Mathurin P, O’Grady J, Carithers RL, et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut 2011; 60:255–260.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000; 119:1637–1648.

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:1613–1619.

- Mathurin P, Louvet A, Dao T, et al. Addition of pentoxifylline to prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis does not improve 6-month survival: results of the CORPENTOX trial (abstract). Hepatology 2011; 54(suppl 1):81A.

- Whitfield K, Rambaldi A, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; CD007339.

- Louvet A, Diaz E, Dharancy S, et al. Early switch to pentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J Hepatol 2008; 48:465–470.

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison ME, et al. Steroids or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis: results of the STOPAH trial [abstract LB-1]. 65th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; November 7–11, 2014; Boston, MA.

- Naveau S, Chollet-Martin S, Dharancy S, et al; Foie-Alcool group of the Association Française pour l’Etude du Foie. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of infliximab associated with prednisolone in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2004; 39:1390–1397.

- Menon KV, Stadheim L, Kamath PS, et al. A pilot study of the safety and tolerability of etanercept in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99:255–260.

- Boetticher NC, Peine CJ, Kwo P, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of etanercept in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:1953–1960.

- Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet MA, et al; AAH-NAC Study Group. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1781–1789.

- Singal AK, Duchini A. Liver transplantation in acute alcoholic hepatitis: current status and future development. World J Hepatol 2011; 3:215–218.

- Singal AK, Bashar H, Anand BS, Jampana SC, Singal V, Kuo YF. Outcomes after liver transplantation for alcoholic hepatitis are similar to alcoholic cirrhosis: exploratory analysis from the UNOS database. Hepatology 2012; 55:1398–1405.

- Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1790–1800.

Alcoholic hepatitis, a severe manifestation of alcoholic liver disease, is rising in incidence. Complete abstinence from alcohol remains the cornerstone of treatment, while other specific interventions aim to decrease short-term mortality rates.

Despite current treatments, about 25% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis eventually die of it. For those who survive hospitalization, measures need to be taken to prevent recidivism. Although liver transplantation seems to hold promise, early transplantation is still largely experimental in alcoholic hepatitis and will likely be available to only a small subset of patients, especially in view of ethical issues and the possible wider implications for transplant centers.

New treatments will largely depend on a better understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology, and future clinical trials should evaluate therapies that improve short-term as well as long-term outcomes.

ACUTE HEPATIC DECOMPENSATION IN A HEAVY DRINKER

Excessive alcohol consumption is very common worldwide, is a major risk factor for liver disease, and is a leading cause of preventable death. Alcoholic cirrhosis is the eighth most common cause of death in the United States and in 2010 was responsible for nearly half of cirrhosis-related deaths worldwide.1

Alcoholic liver disease is a spectrum. Nearly all heavy drinkers (ie, those consuming 40 g or more of alcohol per day, Table 1) have fatty liver changes, 20% to 40% develop fibrosis, 10% to 20% progress to cirrhosis, and of those with cirrhosis, 1% to 2% are diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma every year.2

Within this spectrum, alcoholic hepatitis is a well-defined clinical syndrome characterized by acute hepatic decompensation that typically results from long-standing alcohol abuse. Binge drinkers may also be at risk for alcoholic hepatitis, but good data on the association between drinking patterns and the risk of alcoholic hepatitis are limited.

Alcoholic hepatitis varies in severity from mild to life-threatening.3 Although its exact incidence is unknown, its prevalence in alcoholics has been estimated at 20%.4 Nearly half of patients with alcoholic hepatitis have cirrhosis at the time of their acute presentation, and these patients generally have a poor prognosis, with a 28-day death rate as high as 50% in severe cases.5,6 Moreover, although alcoholic hepatitis develops in only a subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease, hospitalizations for it are increasing in the United States.7

Women are at higher risk of developing alcoholic hepatitis, an observation attributed to the effect of estrogens on oxidative stress and inflammation, lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase levels resulting in slower first-pass metabolism of alcohol, and higher body fat content causing a lower volume of distribution for alcohol than in men.8 The incidence of alcoholic hepatitis is also influenced by a number of demographic and genetic factors as well as nutritional status and coexistence of other liver diseases.9 Most patients diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis are active drinkers, but it can develop even after significantly reducing or stopping alcohol consumption.

FATTY ACIDS, ENZYMES, CYTOKINES, INFLAMMATION

Alcohol consumption induces fatty acid synthesis and inhibits fatty acid oxidation, thereby promoting fat deposition in the liver.

The major enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism are cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and alcohol dehydrogenase. CYP2E1 is inducible and is up-regulated when excess alcohol is ingested, while alcohol dehydrogen-

ase function is relatively stable. Oxidative degradation of alcohol by these enzymes generates reactive oxygen species and acetaldehyde, inducing liver injury.10 Interestingly, it has been proposed that variations in the genes for these enzymes influence alcohol consumption and dependency as well as alcohol-driven tissue damage.

In addition, alcohol disrupts the intestinal mucosal barrier, allowing lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria to travel to the liver via the portal vein. These lipopolysaccharides then bind to and activate sinusoidal Kupffer cells, leading to production of several cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and transforming growth factor beta. These cytokines promote hepatocyte inflammation, apoptosis, and necrosis (Figure 1).11

Besides activating the innate immune system, the reactive oxygen species resulting from alcohol metabolism interact with cellular components, leading to production of protein adducts. These act as antigens that activate the adaptive immune response, followed by B- and T-lymphocyte infiltration, which in turn contribute to liver injury and inflammation.12

THE DIAGNOSIS IS MAINLY CLINICAL

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis is mainly clinical. In its usual presentation, jaundice develops rapidly in a person with a known history of heavy alcohol use. Other symptoms and signs may include ascites, encephalopathy, and fever. On examination, the liver may be enlarged and tender, and a hepatic bruit has been reported.13

Other classic signs of liver disease such as parotid enlargement, Dupuytren contracture, dilated abdominal wall veins, and spider nevi can be present, but none is highly specific or sensitive for alcoholic hepatitis.

Elevated liver enzymes and other clues

Laboratory tests are important in evaluating potential alcoholic hepatitis, although no single laboratory marker can definitively establish alcohol as the cause of liver disease. To detect alcohol consumption, biochemical markers such as aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), mean corpuscular volume, carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, and, more commonly, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase are used.

In the acute setting, typical biochemical derangements in alcoholic hepatitis include elevated AST (up to 2 to 6 times the upper limit of normal; usually less than 300 IU/L) and elevated ALT to a lesser extent,14 with an AST-to-ALT ratio greater than 2. Neutrophilia, anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathy with an elevated international normalized ratio are common.

Patients with alcoholic hepatitis are also prone to develop bacterial infections, and about 7% develop hepatorenal syndrome, itself an ominous sign.15

Imaging studies are valuable in excluding other causes of abnormal liver test results in patients who abuse alcohol, such as biliary obstruction, infiltrative liver diseases, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Screen for alcohol intake

During the initial evaluation of suspected alcoholic hepatitis, one should screen for excessive drinking. In a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, only one of six US adults, including binge drinkers, said they had ever discussed alcohol consumption with a health professional.16 Many patients with alcoholic liver disease in general and alcoholic hepatitis in particular deny alcohol abuse or underreport their intake.17

Screening tests such as the CAGE questionnaire and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test can be used to assess alcohol dependence or abuse.18,19 The CAGE questionnaire consists of four questions:

- Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

- Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt guilty about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (an eye-opener) to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

A yes answer to two or more questions is considered clinically significant.

Is liver biopsy always needed?

Although alcoholic hepatitis can be suspected on the basis of clinical and biochemical clues, liver biopsy remains the gold standard diagnostic tool. It confirms the clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis in about 85% of all patients and in up to 95% when significant hyperbilirubinemia is present.20

However, whether a particular patient needs a biopsy is not always clear. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends biopsy in patients who have a clinical diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis for whom medical treatment is being considered and in those with an uncertain underlying diagnosis.

Findings on liver biopsy in alcoholic hepatitis include steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, neutrophilic infiltration, Mallory bodies (which represent aggregated cytokeratin intermediate filaments and other proteins), and scarring with a typical perivenular distribution as opposed to the periportal fibrosis seen in chronic viral hepatitis. Some histologic findings, such as centrilobular necrosis, may overlap alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

In addition to confirming the diagnosis and staging the disease, liver biopsy has prognostic value. The severity of inflammation and cholestatic changes correlates with poor prognosis and may also predict response to corticosteroid treatment in severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis.21

However, the utility of liver biopsy in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the prognosis of alcoholic hepatitis is controversial for several reasons. Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and ascites are all common in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, often making percutaneous liver biopsy contraindicated. Trans-

jugular liver biopsy is not universally available outside tertiary care centers.

Needed is a minimally invasive test for assessing this disease. Breath analysis might be such a test, offering a noninvasive means to study the composition of volatile organic compounds and elemental gases and an attractive method to evaluate health and disease in a patient-friendly manner. Our group devised a model based on breath levels of trimethylamine and pentane. When we tested it, we found that it distinguishes patients with alcoholic hepatitis from those with acute liver decompensation from causes other than alcohol and controls without liver disease with up to 90% sensitivity and 80% specificity.22

ASSESSING THE SEVERITY OF ALCOHOLIC HEPATITIS

Several models have been developed to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and guide treatment decisions (Table 2).

The MDF (Maddrey Discriminant Function)6 system was the first scoring system developed and is still the most widely used. A score of 32 or higher indicates severe alcoholic hepatitis and has been used as the threshold for starting treatment with corticosteroids.6

The MDF has limitations. Patients with a score lower than 32 are considered not to have severe alcoholic hepatitis, but up to 17% of them still die. Also, since it uses the prothrombin time, its results can vary considerably among laboratories, depending on the sensitivity of the thromboplastin reagent used.

The MELD (Model for End-stage Liver Disease) score. Sheth et al23 compared the MELD and the MDF scores in assessing the severity of alcoholic hepatitis. They found that the MELD performed as well as the MDF in predicting 30-day mortality. A MELD score of greater than 11 had a sensitivity in predicting 30-day mortality of 86% and a specificity of 81%, compared with 86% and 48%, respectively, for MDF scores greater than 32.

Another study found a MELD score of 21 to have the highest sensitivity and specificity in predicting mortality (an estimated 90-day death rate of 20%). Thus, a MELD score of 21 is an appropriate threshold for prompt consideration of specific therapies such as corticosteroids.24

The MELD score has become increasingly important in patients with alcoholic hepatitis, as some of them may become candidates for liver transplantation (see below). Also, serial MELD scores in hospitalized patients have prognostic implications, since an increase of 2 or more points in the first week has been shown to predict in-hospital mortality.25

The GAHS (Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score)26 was shown to identify patients with alcoholic hepatitis who have an especially poor prognosis and need corticosteroid therapy. In those with a GAHS of 9 or higher, the 28-day survival rate was 78% with corticosteroid treatment and 52% without corticosteroid treatment; survival rates at 84 days were 59% and 38%, respectively.26

The ABIC scoring system (Age, Serum Bilirubin, INR, and Serum Creatinine) stratifies patients by risk of death at 90 days27:

- Score less than 6.71: low risk (100% survival)

- A score 6.71–8.99: intermediate risk (70% survival)

- A score 9.0 or higher: high risk (25% survival).

Both the GAHS and ABIC score are limited by lack of external validation.

The Lille score.28 While the above scores are used to identify patients at risk of death from alcoholic hepatitis and to decide on starting corticosteroids, the Lille score is designed to assess response to corticosteroids after 1 week of treatment. It is calculated based on five pretreatment variables and the change in serum bilirubin level at day 7 of corticosteroid therapy. Lille scores range from 0 to 1; a score higher than 0.45 is associated with a 75% mortality rate at 6 months and indicates a lack of response to corticosteroids and that these drugs should be discontinued.28

MANAGEMENT

Supportive treatment

Abstinence from alcohol is the cornerstone of treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Early management of alcohol abuse or dependence is, therefore, warranted in all patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Referral to addiction specialists, motivational therapies, and anticraving drugs such as baclofen can be utilized.

Treat alcohol withdrawal. Alcoholics who suddenly decrease or discontinue their alcohol use are at high risk of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Within 24 hours after the last drink, patients can experience increases in their heart rate and blood pressure, along with irritability and hyperreflexia. Within the next few days, more dangerous complications including seizures and delirium tremens can arise.

Alcohol withdrawal symptoms should be treated with short-acting benzodiazepines or clomethiazole, keeping the risk of worsening encephalopathy in mind.29 If present, complications of cirrhosis such as encephalopathy, ascites, and variceal bleeding should be managed.

Nutritional support is important. Protein-calorie malnutrition is common in alcoholics, as are deficiencies of vitamin A, vitamin D, thiamine, folate, pyridoxine, and zinc.30 Although a randomized controlled trial comparing enteral nutrition (2,000 kcal/day) vs corticosteroids (prednisolone 40 mg/day) in patients with alcoholic hepatitis did not show any difference in the 28-day mortality rate, those who received nutritional support and survived the first month had a lower mortality rate than those treated with corticosteroids (8% vs 37%).31 A daily protein intake of 1.5 g per kilogram of body weight is therefore recommended, even in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.15

Combining enteral nutrition and corticosteroid treatment may have a synergistic effect but is yet to be investigated.

Screen for infection. Patients with alcoholic hepatitis should be screened for infection, as about 25% of those with severe alcoholic hepatitis have an infection at admission.32 Since many of these patients meet the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome, infections can be particularly difficult to diagnose. Patients require close clinical monitoring as well as regular pancultures for early detection. Antibiotics are frequently started empirically even though we lack specific evidence-based guidelines on this practice.33

Corticosteroids

Various studies have evaluated the role of corticosteroids in treating alcoholic hepatitis, differing considerably in sample populations, methods, and end points. Although the results of individual trials differ, meta-analyses indicate that corticosteroids have a moderate beneficial effect in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

For example, Rambaldi et al34 performed a meta-analysis that concluded the mortality rate was lower in alcoholic hepatitis patients with MDF scores of at least 32 or hepatic encephalopathy who were treated with corticosteroids than in controls (relative risk 0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.16–0.86).

Therefore, in the absence of contraindications, the AASLD recommends starting corticosteroids in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, defined as an MDF score of 32 or higher.21 The preferred agent is oral prednisolone 40 mg daily or parenteral methylprednisolone 32 mg daily for 4 weeks and then tapered over the next 2 to 4 weeks or abruptly discontinued. Because activation of prednisone is decreased in patients with liver disease, prednisolone (the active form) is preferred over prednisone (the inactive precursor).35 In alcoholic hepatitis, the number needed to treat with corticosteroids to prevent one death has been calculated36 at 5.

As mentioned, response to corticosteroids is commonly assessed at 1 week of treatment using the Lille score. A score higher than 0.45 predicts a poor response and should trigger discontinuation of corticosteroids, particularly in those classified as null responders (Lille score > 0.56).

Adverse effects of steroids include sepsis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and steroid psychosis. Of note, patients who have evidence of hepatorenal syndrome or gastrointestinal bleeding tend to have a less favorable response to corticosteroids. Also, while infections were once considered a contraindication to steroid therapy, recent evidence suggests that steroid use might not be precluded in infected patients after appropriate antibiotic therapy. Infections occur in about a quarter of all alcoholic hepatitis patients treated with steroids, more frequently in null responders (42.5%) than in responders (11.1%), which supports corticosteroid discontinuance at 1 week in null responders.32

Pentoxifylline

An oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, pentoxifylline, also inhibits production of several cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha. At a dose of 400 mg orally three times daily for 4 weeks, pentoxifylline has been used in treating severe alcoholic hepatitis (MDF score ≥ 32) and is recommended especially if corticosteroids are contraindicated, as with sepsis.21

An early double-blind clinical trial randomized patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis to receive either pentoxifylline 400 mg orally three times daily or placebo. Of the patients who received pentoxifylline, 24.5% died during the index hospitalization, compared with 46.1% of patients who received placebo. This survival benefit was mainly related to a markedly lower incidence of hepatorenal syndrome as the cause of death in the pentoxifylline group than in the placebo group (50% vs 91.7% of deaths).37

In a small clinical trial in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, pentoxifylline recipients had a higher 3-month survival rate than prednisolone recipients (35.29% vs 14.71%, P = .04).38 However, a larger trial showed no improvement in 6-month survival with the combination of prednisolone and pentoxifylline compared with prednisolone alone (69.9% vs 69.2%, P = .91).39 Also, a meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials found no survival benefit with pentoxifylline therapy.40

Of note, in the unfortunate subgroup of patients who have a poor response to corticosteroids, no alternative treatment, including pentoxifylline, has been shown to be effective.41

Prednisone or pentoxifylline? Very recently, results of the Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) trial have been released.42 This is a large, multicenter, double-blinded clinical trial that aimed to provide a definitive answer to whether corticosteroids or pentoxifylline (or both) are beneficial in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. The study included 1,103 adult patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (MDF score ≥ 32) who were randomized to monotherapy with prednisolone or pentoxifylline, combination therapy, or placebo. The primary end point was mortality at 28 days, and secondary end points included mortality at 90 days and at 1 year. Prednisolone reduced 28-day mortality by about 39%. In contrast, the 28-day mortality rate was similar in patients who received pentoxifylline and those who did not. Also, neither drug was significantly associated with a survival benefit beyond 28 days. The investigators concluded that pentoxifylline has no impact on disease progression and should not be used for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis.42

Other tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors not recommended

Two other tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, infliximab and etanercept, have been tested in clinical trials in alcoholic hepatitis. Unfortunately, the results were not encouraging, with no major reduction in mortality.43–45 In fact, these trials demonstrated a significantly increased risk of infections in the treatment groups. Therefore, these drugs are not recommended for treating alcoholic hepatitis.

A possible explanation is that tumor necrosis factor alpha plays an important role in liver regeneration, aiding in recovery from alcohol-induced liver injury, and inhibiting it can have deleterious consequences.

Other agents

A number of other agents have undergone clinical trials in alcoholic hepatitis.

N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant that replenishes glutathione stores in hepatocytes, was evaluated in a randomized clinical trial in combination with prednisolone.46 Although the 1-month mortality rate was significantly lower in the combination group than in the prednisolone-only group (8% vs 24%, P = .006), 3-month and 6-month mortality rates were not. Nonetheless, the rates of infection and hepatorenal syndrome were lower in the combination group. Therefore, corticosteroids and N-acetylcysteine may have synergistic effects, but the optimum duration of N-acetylcysteine therapy needs to be determined in further studies.

Vitamin E, silymarin, propylthiouracil, colchicine, and oxandrolone (an anabolic steroid) have also been studied, but with no convincing benefit.21

Role of liver transplantation

Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease has been a topic of great medical and social controversy. The view that alcoholic patients are responsible for their own illness led to caution when contemplating liver transplantation. Many countries require 6 months of abstinence from alcohol before placing a patient on the liver transplant list, posing a major obstacle to patients with alcoholic hepatitis, as almost all are active drinkers at the time of presentation and many will die within 6 months. Reasons for this 6-month rule include donor shortage and risk of recidivism.47

With regard to survival following alcoholic hepatitis, a study utilizing the United Network for Organ Sharing database matched patients with alcoholic hepatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis who underwent liver transplantation. Rates of 5-year graft survival were 75% in those with alcoholic hepatitis and 73% in those with alcoholic cirrhosis (P = .97), and rates of patient survival were 80% and 78% (P = .90), respectively. Proportional regression analysis adjusting for other variables showed no impact of the etiology of liver disease on graft or patient survival. The investigators concluded that liver transplantation could be considered in a select group of patients with alcoholic hepatitis who do not improve with medical therapy.48

In a pivotal case-control prospective study,49 26 patients with Lille scores greater than 0.45 were listed for liver transplantation within a median of 13 days after nonresponse to medical therapy. The cumulative 6-month survival rate was higher in patients who received a liver transplant early than in those who did not (77% vs 23%, P < .001). This benefit was maintained through 2 years of follow-up (hazard ratio 6.08, P = .004). Of note, all these patients had supportive family members, no severe coexisting conditions, and a commitment to alcohol abstinence (although 3 patients resumed drinking after liver transplantation).49

Although these studies support early liver transplantation in carefully selected patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, the criteria for transplantation in this group need to be refined. Views on alcoholism also need to be reconciled, as strong evidence is emerging that implicates genetic and environmental influences on alcohol dependence.

Management algorithm

Figure 2 shows a suggested management algorithm for alcoholic hepatitis, adapted from the guidelines of the AASLD and European Association for the Study of the Liver.

NEW THERAPIES NEEDED

Novel therapies for severe alcoholic hepatitis are urgently needed to help combat this devastating condition. Advances in understanding its pathophysiology have uncovered several new therapeutic targets, and new agents are already being evaluated in clinical trials.

IMM 124-E, a hyperimmune bovine colostrum enriched with immunoglobulin G anti-lipopolysaccharide, is going to be evaluated in combination with prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Anakinra, an interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, has significant anti-inflammatory activity and is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. A clinical trial to evaluate its role in alcoholic hepatitis has been designed in which patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (defined as a MELD score ≥ 21) will be randomized to receive either methylprednisolone or a combination of anakinra, pentoxifylline, and zinc (a mineral that improves gut integrity).

Emricasan, an orally active caspase protease inhibitor, is another agent currently being tested in a phase 2 clinical trial in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Since caspases induce apoptosis, inhibiting them should theoretically dampen alcohol-induced hepatocyte injury.

Interleukin 22, a hepatoprotective cytokine, shows promise as a treatment and will soon be evaluated in alcoholic hepatitis.

Alcoholic hepatitis, a severe manifestation of alcoholic liver disease, is rising in incidence. Complete abstinence from alcohol remains the cornerstone of treatment, while other specific interventions aim to decrease short-term mortality rates.

Despite current treatments, about 25% of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis eventually die of it. For those who survive hospitalization, measures need to be taken to prevent recidivism. Although liver transplantation seems to hold promise, early transplantation is still largely experimental in alcoholic hepatitis and will likely be available to only a small subset of patients, especially in view of ethical issues and the possible wider implications for transplant centers.

New treatments will largely depend on a better understanding of the disease’s pathophysiology, and future clinical trials should evaluate therapies that improve short-term as well as long-term outcomes.

ACUTE HEPATIC DECOMPENSATION IN A HEAVY DRINKER

Excessive alcohol consumption is very common worldwide, is a major risk factor for liver disease, and is a leading cause of preventable death. Alcoholic cirrhosis is the eighth most common cause of death in the United States and in 2010 was responsible for nearly half of cirrhosis-related deaths worldwide.1

Alcoholic liver disease is a spectrum. Nearly all heavy drinkers (ie, those consuming 40 g or more of alcohol per day, Table 1) have fatty liver changes, 20% to 40% develop fibrosis, 10% to 20% progress to cirrhosis, and of those with cirrhosis, 1% to 2% are diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma every year.2

Within this spectrum, alcoholic hepatitis is a well-defined clinical syndrome characterized by acute hepatic decompensation that typically results from long-standing alcohol abuse. Binge drinkers may also be at risk for alcoholic hepatitis, but good data on the association between drinking patterns and the risk of alcoholic hepatitis are limited.

Alcoholic hepatitis varies in severity from mild to life-threatening.3 Although its exact incidence is unknown, its prevalence in alcoholics has been estimated at 20%.4 Nearly half of patients with alcoholic hepatitis have cirrhosis at the time of their acute presentation, and these patients generally have a poor prognosis, with a 28-day death rate as high as 50% in severe cases.5,6 Moreover, although alcoholic hepatitis develops in only a subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease, hospitalizations for it are increasing in the United States.7

Women are at higher risk of developing alcoholic hepatitis, an observation attributed to the effect of estrogens on oxidative stress and inflammation, lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase levels resulting in slower first-pass metabolism of alcohol, and higher body fat content causing a lower volume of distribution for alcohol than in men.8 The incidence of alcoholic hepatitis is also influenced by a number of demographic and genetic factors as well as nutritional status and coexistence of other liver diseases.9 Most patients diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis are active drinkers, but it can develop even after significantly reducing or stopping alcohol consumption.

FATTY ACIDS, ENZYMES, CYTOKINES, INFLAMMATION

Alcohol consumption induces fatty acid synthesis and inhibits fatty acid oxidation, thereby promoting fat deposition in the liver.

The major enzymes involved in alcohol metabolism are cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) and alcohol dehydrogenase. CYP2E1 is inducible and is up-regulated when excess alcohol is ingested, while alcohol dehydrogen-

ase function is relatively stable. Oxidative degradation of alcohol by these enzymes generates reactive oxygen species and acetaldehyde, inducing liver injury.10 Interestingly, it has been proposed that variations in the genes for these enzymes influence alcohol consumption and dependency as well as alcohol-driven tissue damage.

In addition, alcohol disrupts the intestinal mucosal barrier, allowing lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria to travel to the liver via the portal vein. These lipopolysaccharides then bind to and activate sinusoidal Kupffer cells, leading to production of several cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and transforming growth factor beta. These cytokines promote hepatocyte inflammation, apoptosis, and necrosis (Figure 1).11

Besides activating the innate immune system, the reactive oxygen species resulting from alcohol metabolism interact with cellular components, leading to production of protein adducts. These act as antigens that activate the adaptive immune response, followed by B- and T-lymphocyte infiltration, which in turn contribute to liver injury and inflammation.12

THE DIAGNOSIS IS MAINLY CLINICAL