User login

Macrolide monotherapy works in some NTM lung disease

Patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis and one form of Mycobacterium abscessus disease can be successfully treated with long-term oral macrolide monotherapy following short-term intravenous combination antibiotic therapy, a Korean research team has shown.

The M. abscessus complex is implicated in between a fifth and half of all cases of lung disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Though treatment is notoriously difficult and prolonged in all NTM lung disease, one subspecies of M. abscessus – M. massiliense – lacks the active gene needed for developing resistance to macrolide-based antibiotics, making it potentially more readily treated.

In research published in CHEST, Won-Jung Koh, MD, of Samsung Medical Center and Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, sought to determine the optimal treatment protocol for patients with massiliense disease (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6]:1211-21). They identified 71 patients with massiliense disease who had initiated antibiotic treatment between January 2007 and December 2012. These patients were part of an ongoing prospective cohort study on NTM lung disease. The first 28 patients in the study were hospitalized for 4 weeks and treated with intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with oral clarithromycin and a fluoroquinolone. Following discharge these patients remained on the oral agents for 24 months.

Two years into the study, the protocol changed, and the next 43 patients were treated with a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents. In some patients, azithromycin, which came into use in Korea for NTM lung disease in 2011, replaced a fluoroquinolone. After discharge, all patients stayed on the oral macrolides (with seven also taking a fluoroquinolone) until their sputum cultures were negative for 12 months.

For the patients treated for 4 weeks, the response rates after 12 months of treatment were 89% for symptoms, 79% for computed tomography, and 100% for negative sputum cultures. In the patients treated for 2 weeks, they were 100%, 91%, and 91%, respectively. None of these differences between the two groups were statistically significant. Median total treatment duration, however, was significantly shorter – by nearly a year – in the 2-week plus macrolide monotherapy group than in the other group of patients (15.2 months vs. 23.9 months, P less than .001).

Acquired macrolide resistance developed in two patients in the group who received a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents, including one case of high-level clarithromycin resistance. Genotyping revealed reinfection with different strains of M. massiliense.

“[Oral] macrolide therapy after an initial 2-week course of combination antibiotics, rather than long-term parenteral antibiotics, might be effective in most patients with M. massiliense lung disease,” Dr. Koh and colleagues wrote, noting that their study’s nonrandomized single-site design was a limitation, and that multicenter randomized trials would be needed “to assess the efficacy” of the findings.

The Korean government funded Dr. Koh and colleagues’ study. None of the authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

“In this study by Koh et al., it is gratifying that most patients had a favorable microbiologic outcome. It is also somewhat surprising that only two patients developed acquired macrolide resistant M. abscessus subsp massiliense isolates. While the absolute number is low, for those two individuals, the consequences of developing macrolide resistance are far from trivial. They have transitioned from having a mycobacterial infection that is relatively easy to treat effectively to a mycobacterial infection that is not,” David E. Griffith, MD, FCCP, and Timothy R. Aksamit, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial published in the December issue of CHEST (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6];1177-8).

The authors noted that they “enthusiastically applaud and acknowledge the prolific and consistently excellent work done by the group in South Korea, but we cannot endorse the widespread adoption of macrolide monotherapy for” this patient group. “In our view, the risk/benefit balance of this approach does not favor macrolide monotherapy even though the majority of patients in this study were adequately treated.”

Dr. Griffith is professor of medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, Tyler, and Dr. Aksamit is a consultant on pulmonary disease and critical care medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. They disclosed no conflicts of interest.

“In this study by Koh et al., it is gratifying that most patients had a favorable microbiologic outcome. It is also somewhat surprising that only two patients developed acquired macrolide resistant M. abscessus subsp massiliense isolates. While the absolute number is low, for those two individuals, the consequences of developing macrolide resistance are far from trivial. They have transitioned from having a mycobacterial infection that is relatively easy to treat effectively to a mycobacterial infection that is not,” David E. Griffith, MD, FCCP, and Timothy R. Aksamit, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial published in the December issue of CHEST (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6];1177-8).

The authors noted that they “enthusiastically applaud and acknowledge the prolific and consistently excellent work done by the group in South Korea, but we cannot endorse the widespread adoption of macrolide monotherapy for” this patient group. “In our view, the risk/benefit balance of this approach does not favor macrolide monotherapy even though the majority of patients in this study were adequately treated.”

Dr. Griffith is professor of medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, Tyler, and Dr. Aksamit is a consultant on pulmonary disease and critical care medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. They disclosed no conflicts of interest.

“In this study by Koh et al., it is gratifying that most patients had a favorable microbiologic outcome. It is also somewhat surprising that only two patients developed acquired macrolide resistant M. abscessus subsp massiliense isolates. While the absolute number is low, for those two individuals, the consequences of developing macrolide resistance are far from trivial. They have transitioned from having a mycobacterial infection that is relatively easy to treat effectively to a mycobacterial infection that is not,” David E. Griffith, MD, FCCP, and Timothy R. Aksamit, MD, FCCP, wrote in an editorial published in the December issue of CHEST (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6];1177-8).

The authors noted that they “enthusiastically applaud and acknowledge the prolific and consistently excellent work done by the group in South Korea, but we cannot endorse the widespread adoption of macrolide monotherapy for” this patient group. “In our view, the risk/benefit balance of this approach does not favor macrolide monotherapy even though the majority of patients in this study were adequately treated.”

Dr. Griffith is professor of medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, Tyler, and Dr. Aksamit is a consultant on pulmonary disease and critical care medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. They disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis and one form of Mycobacterium abscessus disease can be successfully treated with long-term oral macrolide monotherapy following short-term intravenous combination antibiotic therapy, a Korean research team has shown.

The M. abscessus complex is implicated in between a fifth and half of all cases of lung disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Though treatment is notoriously difficult and prolonged in all NTM lung disease, one subspecies of M. abscessus – M. massiliense – lacks the active gene needed for developing resistance to macrolide-based antibiotics, making it potentially more readily treated.

In research published in CHEST, Won-Jung Koh, MD, of Samsung Medical Center and Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, sought to determine the optimal treatment protocol for patients with massiliense disease (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6]:1211-21). They identified 71 patients with massiliense disease who had initiated antibiotic treatment between January 2007 and December 2012. These patients were part of an ongoing prospective cohort study on NTM lung disease. The first 28 patients in the study were hospitalized for 4 weeks and treated with intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with oral clarithromycin and a fluoroquinolone. Following discharge these patients remained on the oral agents for 24 months.

Two years into the study, the protocol changed, and the next 43 patients were treated with a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents. In some patients, azithromycin, which came into use in Korea for NTM lung disease in 2011, replaced a fluoroquinolone. After discharge, all patients stayed on the oral macrolides (with seven also taking a fluoroquinolone) until their sputum cultures were negative for 12 months.

For the patients treated for 4 weeks, the response rates after 12 months of treatment were 89% for symptoms, 79% for computed tomography, and 100% for negative sputum cultures. In the patients treated for 2 weeks, they were 100%, 91%, and 91%, respectively. None of these differences between the two groups were statistically significant. Median total treatment duration, however, was significantly shorter – by nearly a year – in the 2-week plus macrolide monotherapy group than in the other group of patients (15.2 months vs. 23.9 months, P less than .001).

Acquired macrolide resistance developed in two patients in the group who received a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents, including one case of high-level clarithromycin resistance. Genotyping revealed reinfection with different strains of M. massiliense.

“[Oral] macrolide therapy after an initial 2-week course of combination antibiotics, rather than long-term parenteral antibiotics, might be effective in most patients with M. massiliense lung disease,” Dr. Koh and colleagues wrote, noting that their study’s nonrandomized single-site design was a limitation, and that multicenter randomized trials would be needed “to assess the efficacy” of the findings.

The Korean government funded Dr. Koh and colleagues’ study. None of the authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

Patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis and one form of Mycobacterium abscessus disease can be successfully treated with long-term oral macrolide monotherapy following short-term intravenous combination antibiotic therapy, a Korean research team has shown.

The M. abscessus complex is implicated in between a fifth and half of all cases of lung disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Though treatment is notoriously difficult and prolonged in all NTM lung disease, one subspecies of M. abscessus – M. massiliense – lacks the active gene needed for developing resistance to macrolide-based antibiotics, making it potentially more readily treated.

In research published in CHEST, Won-Jung Koh, MD, of Samsung Medical Center and Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, sought to determine the optimal treatment protocol for patients with massiliense disease (Chest. 2016 Dec;150[6]:1211-21). They identified 71 patients with massiliense disease who had initiated antibiotic treatment between January 2007 and December 2012. These patients were part of an ongoing prospective cohort study on NTM lung disease. The first 28 patients in the study were hospitalized for 4 weeks and treated with intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with oral clarithromycin and a fluoroquinolone. Following discharge these patients remained on the oral agents for 24 months.

Two years into the study, the protocol changed, and the next 43 patients were treated with a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents. In some patients, azithromycin, which came into use in Korea for NTM lung disease in 2011, replaced a fluoroquinolone. After discharge, all patients stayed on the oral macrolides (with seven also taking a fluoroquinolone) until their sputum cultures were negative for 12 months.

For the patients treated for 4 weeks, the response rates after 12 months of treatment were 89% for symptoms, 79% for computed tomography, and 100% for negative sputum cultures. In the patients treated for 2 weeks, they were 100%, 91%, and 91%, respectively. None of these differences between the two groups were statistically significant. Median total treatment duration, however, was significantly shorter – by nearly a year – in the 2-week plus macrolide monotherapy group than in the other group of patients (15.2 months vs. 23.9 months, P less than .001).

Acquired macrolide resistance developed in two patients in the group who received a 2-week course of intravenous amikacin and cefoxitin along with the oral agents, including one case of high-level clarithromycin resistance. Genotyping revealed reinfection with different strains of M. massiliense.

“[Oral] macrolide therapy after an initial 2-week course of combination antibiotics, rather than long-term parenteral antibiotics, might be effective in most patients with M. massiliense lung disease,” Dr. Koh and colleagues wrote, noting that their study’s nonrandomized single-site design was a limitation, and that multicenter randomized trials would be needed “to assess the efficacy” of the findings.

The Korean government funded Dr. Koh and colleagues’ study. None of the authors disclosed conflicts of interest.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: A short course of intravenous antibiotics followed by oral macrolides may be effective at treating lung disease caused by the massiliense subspecies of M. abscessus.

Major finding: Of 43 patients receiving 2 weeks of combination antibiotics followed by a year of oral macrolides, 39 (91%) converted to negative sputum cultures before 12 months.

Data source: A prospective cohort study enrolling 71 patients at a single treatment center in Korea.

Disclosures: The Korean government sponsored the study and investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

ASTRO guidelines lower age thresholds for APBI

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

The American Society for Radiation Oncology has issued new guidelines recommending accelerated partial breast irradiation brachytherapy (APBI) as an alternative to whole breast irradiation (WBI) after surgery in early-stage breast cancer patients, and lowering the age range of patients considered suitable for the procedure to people 50 and older, from 60.

With APBI, localized radiation is delivered to the region around the excised tissue, reducing treatment time and sparing healthy tissue. APBI may also be considered for patients 40 and older, according to ASTRO, if they meet all of the pathologic criteria for suitability listed in the guidelines for patients 50 and above.

The guidelines represent the first ASTRO update on APBI since 2009. In addition to expanding the age range for APBI treatment, the guidelines add low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ as an indication. The guidelines also address intraoperative radiation therapy, or IORT, in which patients receive low-energy photon or electron radiation during surgery (Pract Rad Oncol. 2016 Nov. 17 doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.09.007).

While IORT is suitable for patients with invasive cancer eligible for APBI, the guidelines say, patients considering this option should be counseled about the risk of recurrence compared with standard treatment, and, with photon IORT, about potential toxicity risk requiring follow-up. Though more than 40 studies were considered by the ASTRO committee, including large randomized trials comparing APBI with WBI, the new recommendations represent “more of a tweak than a revolution,” said Jay Harris, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, one of the guideline authors.

Dr. Harris noted in an interview that two important randomized controlled trials comparing APBI and WBI are still underway, with full follow-up results expected in 2-3 years, after which more definitive recommendations can be made. For the intraoperative radiation advice contained in the guidelines, “we had evidence from two trials looking at different approaches,” Dr. Harris said. “One has long-term data using an electron beam in the operating room – this group showed that that approach seems reasonable in patients that we at ASTRO considered suitable in general for APBI. The other approach is low-dose photon radiation, for which we have only short-term follow-up, making us more hesitant to endorse it.” As for the new recommendation sanctioning APBI for ductal carcinoma, “There’s a lot of variation [in protocols] across the country, compared with invasive cancer,” Dr. Harris said. “We’re kind of all over the map with DCIS. This guideline presents another option.”

The guidelines were sponsored by ASTRO; two authors disclosed financial relationships with firms that make radiologic technology.

FROM PRACTICAL RADIATION ONCOLOGY

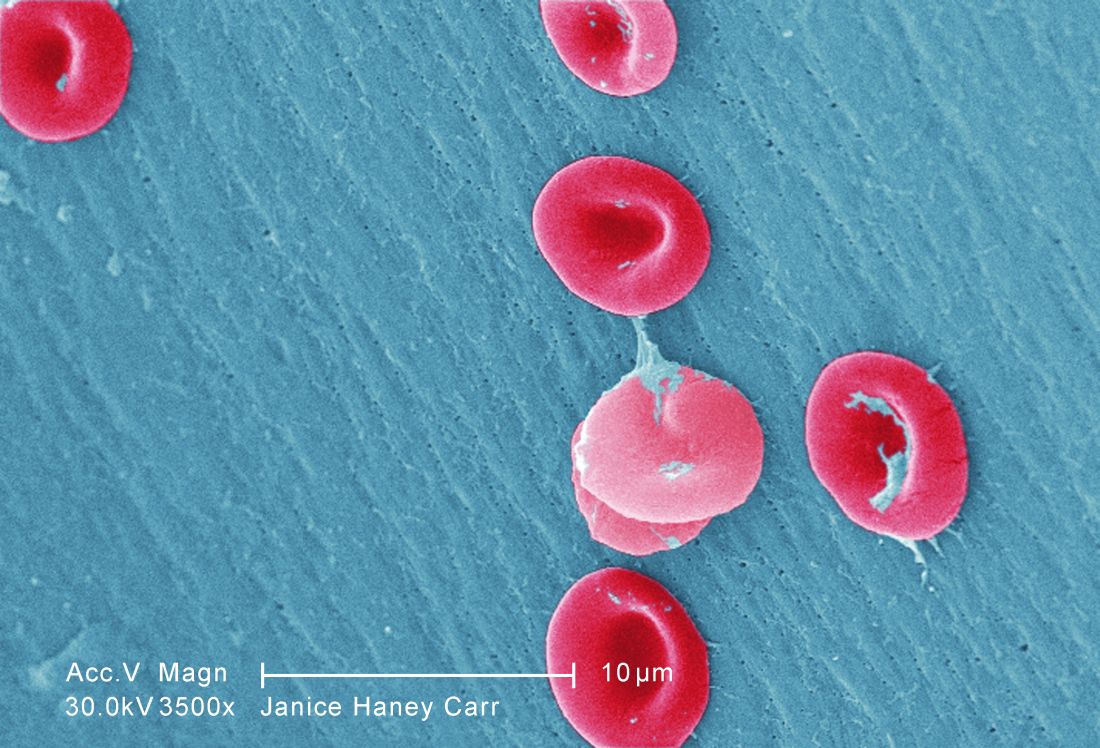

SelG1 cut pain crises in sickle cell disease

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the Nigerian trial, led by Najibah Aliyu Galadanci, MD, MPH, of Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria, the goal was to determine whether families of children with sickle cell disease and transcranial Doppler measurements indicative of increased risk for stroke could be recruited and retained in a large clinical trial, and whether they could adhere to the medication regimen. The trial also obtained preliminary evidence for hydroxyurea’s safety in this clinical setting, where transfusion therapy is not an option for most children.

Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues approached 375 families for transcranial Doppler screening, and 90% accepted. Among families of children found to have elevated measures of risk on transcranial Doppler, 92% participated in the study and received a moderate dose of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg) for 2 years. A comparison group included 210 children without elevated measures on transcranial Doppler. These children underwent regular monitoring but were not offered medication unless transcranial Doppler measures were found to be elevated.

Study adherence was exceptionally high: the families missed no monthly research visits, and no participants in the active treatment group dropped out voluntarily.

Also, at 2 years, the children treated with hydroxyurea did not have evidence of excessive toxicity, compared with the children who did not receive the drug. “Our results provide strong preliminary evidence supporting the current multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg per day vs. 10 mg/kg per day) for preventing primary strokes in children with sickle cell anemia living in Nigeria,” Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the third study, a multidisciplinary team decreased mortality in pregnant women who had sickle cell disease and lived in low and middle income settings, according to Eugenia Vicky Naa Kwarley Asare, MD, of the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics and the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra.

In a prospective trial in Ghana, where maternal mortality among women with sickle cell disease is estimated to be 8,300 per 100,000 live births, compared with 690 for women without sickle cell disease, Dr. Asare and her colleagues’ multidisciplinary team included obstetricians, hematologists, pulmonologists, and nurses, and the planned intervention protocols included a number of changes to make management more consistent and intensive. A total of 154 pregnancies were evaluated before the intervention, and 91 after. Median gestational age was 24 weeks at enrollment, and median maternal age was 29 years for both pre- and post-intervention cohorts.

Maternal mortality before the intervention was 9.7% (15 of 154) and after the intervention was 1.1% (1 of 91) of total deliveries.

Dr. Ataga’s study was sponsored by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s manufacturer, and included coinvestigators who are employees of Selexys Pharmaceuticals or who disclosed relationships with other drug manufacturers. Dr. Galadanci’s and Dr. Asare’s groups disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the Nigerian trial, led by Najibah Aliyu Galadanci, MD, MPH, of Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria, the goal was to determine whether families of children with sickle cell disease and transcranial Doppler measurements indicative of increased risk for stroke could be recruited and retained in a large clinical trial, and whether they could adhere to the medication regimen. The trial also obtained preliminary evidence for hydroxyurea’s safety in this clinical setting, where transfusion therapy is not an option for most children.

Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues approached 375 families for transcranial Doppler screening, and 90% accepted. Among families of children found to have elevated measures of risk on transcranial Doppler, 92% participated in the study and received a moderate dose of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg) for 2 years. A comparison group included 210 children without elevated measures on transcranial Doppler. These children underwent regular monitoring but were not offered medication unless transcranial Doppler measures were found to be elevated.

Study adherence was exceptionally high: the families missed no monthly research visits, and no participants in the active treatment group dropped out voluntarily.

Also, at 2 years, the children treated with hydroxyurea did not have evidence of excessive toxicity, compared with the children who did not receive the drug. “Our results provide strong preliminary evidence supporting the current multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg per day vs. 10 mg/kg per day) for preventing primary strokes in children with sickle cell anemia living in Nigeria,” Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the third study, a multidisciplinary team decreased mortality in pregnant women who had sickle cell disease and lived in low and middle income settings, according to Eugenia Vicky Naa Kwarley Asare, MD, of the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics and the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra.

In a prospective trial in Ghana, where maternal mortality among women with sickle cell disease is estimated to be 8,300 per 100,000 live births, compared with 690 for women without sickle cell disease, Dr. Asare and her colleagues’ multidisciplinary team included obstetricians, hematologists, pulmonologists, and nurses, and the planned intervention protocols included a number of changes to make management more consistent and intensive. A total of 154 pregnancies were evaluated before the intervention, and 91 after. Median gestational age was 24 weeks at enrollment, and median maternal age was 29 years for both pre- and post-intervention cohorts.

Maternal mortality before the intervention was 9.7% (15 of 154) and after the intervention was 1.1% (1 of 91) of total deliveries.

Dr. Ataga’s study was sponsored by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s manufacturer, and included coinvestigators who are employees of Selexys Pharmaceuticals or who disclosed relationships with other drug manufacturers. Dr. Galadanci’s and Dr. Asare’s groups disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the Nigerian trial, led by Najibah Aliyu Galadanci, MD, MPH, of Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria, the goal was to determine whether families of children with sickle cell disease and transcranial Doppler measurements indicative of increased risk for stroke could be recruited and retained in a large clinical trial, and whether they could adhere to the medication regimen. The trial also obtained preliminary evidence for hydroxyurea’s safety in this clinical setting, where transfusion therapy is not an option for most children.

Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues approached 375 families for transcranial Doppler screening, and 90% accepted. Among families of children found to have elevated measures of risk on transcranial Doppler, 92% participated in the study and received a moderate dose of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg) for 2 years. A comparison group included 210 children without elevated measures on transcranial Doppler. These children underwent regular monitoring but were not offered medication unless transcranial Doppler measures were found to be elevated.

Study adherence was exceptionally high: the families missed no monthly research visits, and no participants in the active treatment group dropped out voluntarily.

Also, at 2 years, the children treated with hydroxyurea did not have evidence of excessive toxicity, compared with the children who did not receive the drug. “Our results provide strong preliminary evidence supporting the current multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg per day vs. 10 mg/kg per day) for preventing primary strokes in children with sickle cell anemia living in Nigeria,” Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the third study, a multidisciplinary team decreased mortality in pregnant women who had sickle cell disease and lived in low and middle income settings, according to Eugenia Vicky Naa Kwarley Asare, MD, of the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics and the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra.

In a prospective trial in Ghana, where maternal mortality among women with sickle cell disease is estimated to be 8,300 per 100,000 live births, compared with 690 for women without sickle cell disease, Dr. Asare and her colleagues’ multidisciplinary team included obstetricians, hematologists, pulmonologists, and nurses, and the planned intervention protocols included a number of changes to make management more consistent and intensive. A total of 154 pregnancies were evaluated before the intervention, and 91 after. Median gestational age was 24 weeks at enrollment, and median maternal age was 29 years for both pre- and post-intervention cohorts.

Maternal mortality before the intervention was 9.7% (15 of 154) and after the intervention was 1.1% (1 of 91) of total deliveries.

Dr. Ataga’s study was sponsored by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s manufacturer, and included coinvestigators who are employees of Selexys Pharmaceuticals or who disclosed relationships with other drug manufacturers. Dr. Galadanci’s and Dr. Asare’s groups disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM ASH 2016

Toddler gaze patterns heritable, stable over time

NEW YORK – A team of autism researchers has found that patterns of social-visual engagement are markedly more similar among identical twin toddlers than among fraternal twins.

Social-visual engagement (SVE), which can be measured using eye-tracking technology, is how humans give preferential attention to social stimuli – in particular, people’s eyes and mouths, which provide important information for communication.

Lower levels of SVE have been shown to be associated with the later development of autism, even in children just a few months old (Nature. 2013 Dec 19;504:427-31). “But what hasn’t been shown until now is that this measure relates to genetics,” said Natasha Marrus, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

The identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, “showed much more similar levels of social-visual engagement than fraternal twins,” Dr. Marrus said, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.95) for time spent looking at eyes, compared with 0.35 (95% CI, 0.07-0.59) for fraternal twins. Similar results were obtained for the caregiver questionnaire, suggesting strong genetic influences on both early reciprocal social behavior and SVE, said Dr. Marrus, also of Washington University.

At 36 months, 69 of the twin pairs were reevaluated. The investigators again found significantly greater SVE concordance for the identical twins: ICC, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.75-0.98), compared with ICC, 0.25 (95% CI, 0.0-0.60) for fraternal twins. They also found SVE patterns strongly correlated between 21 and 36 months for individual twins, indicating traitlike stability of this behavior over time.

“These two measures that are heritable, like autism, can be measured in a general population sample, which means they show good variability – potentially allowing the detection of subtle differences that may correspond to levels of risk for autism,” Dr. Marrus said. “By 18-21 months, the risk markers for later autism are already there – if you use a nuanced enough measure to detect them.”

Dr. Marrus said that while some practitioners have been able to reliably diagnose autism in children younger than 24 months, “it’s usually with the most severe cases,” she said. “But 18 months is a big time for social as well as language development, which becomes easier to measure at that point.”

A future direction for study, she said, “would be to go earlier. If we’re seeing this at 18 months, maybe we’d see it at 12.”

With autism, “early intervention is key, and even 6 months could make a difference,” Dr. Marrus said. “These two measures stand a really good chance of telling us important things about autism – which at early ages means better diagnostic prediction, measurement of severity and risk, and the potential to monitor responses to interventions.”

The National Institutes of Health supported the study through a grant to Dr. Constantino, and Dr. Marrus’s work was supported with a postdoctoral fellowship from the Autism Science Foundation. The investigators declared no relevant financial conflicts.

NEW YORK – A team of autism researchers has found that patterns of social-visual engagement are markedly more similar among identical twin toddlers than among fraternal twins.

Social-visual engagement (SVE), which can be measured using eye-tracking technology, is how humans give preferential attention to social stimuli – in particular, people’s eyes and mouths, which provide important information for communication.

Lower levels of SVE have been shown to be associated with the later development of autism, even in children just a few months old (Nature. 2013 Dec 19;504:427-31). “But what hasn’t been shown until now is that this measure relates to genetics,” said Natasha Marrus, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

The identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, “showed much more similar levels of social-visual engagement than fraternal twins,” Dr. Marrus said, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.95) for time spent looking at eyes, compared with 0.35 (95% CI, 0.07-0.59) for fraternal twins. Similar results were obtained for the caregiver questionnaire, suggesting strong genetic influences on both early reciprocal social behavior and SVE, said Dr. Marrus, also of Washington University.

At 36 months, 69 of the twin pairs were reevaluated. The investigators again found significantly greater SVE concordance for the identical twins: ICC, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.75-0.98), compared with ICC, 0.25 (95% CI, 0.0-0.60) for fraternal twins. They also found SVE patterns strongly correlated between 21 and 36 months for individual twins, indicating traitlike stability of this behavior over time.

“These two measures that are heritable, like autism, can be measured in a general population sample, which means they show good variability – potentially allowing the detection of subtle differences that may correspond to levels of risk for autism,” Dr. Marrus said. “By 18-21 months, the risk markers for later autism are already there – if you use a nuanced enough measure to detect them.”

Dr. Marrus said that while some practitioners have been able to reliably diagnose autism in children younger than 24 months, “it’s usually with the most severe cases,” she said. “But 18 months is a big time for social as well as language development, which becomes easier to measure at that point.”

A future direction for study, she said, “would be to go earlier. If we’re seeing this at 18 months, maybe we’d see it at 12.”

With autism, “early intervention is key, and even 6 months could make a difference,” Dr. Marrus said. “These two measures stand a really good chance of telling us important things about autism – which at early ages means better diagnostic prediction, measurement of severity and risk, and the potential to monitor responses to interventions.”

The National Institutes of Health supported the study through a grant to Dr. Constantino, and Dr. Marrus’s work was supported with a postdoctoral fellowship from the Autism Science Foundation. The investigators declared no relevant financial conflicts.

NEW YORK – A team of autism researchers has found that patterns of social-visual engagement are markedly more similar among identical twin toddlers than among fraternal twins.

Social-visual engagement (SVE), which can be measured using eye-tracking technology, is how humans give preferential attention to social stimuli – in particular, people’s eyes and mouths, which provide important information for communication.

Lower levels of SVE have been shown to be associated with the later development of autism, even in children just a few months old (Nature. 2013 Dec 19;504:427-31). “But what hasn’t been shown until now is that this measure relates to genetics,” said Natasha Marrus, MD, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

The identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, “showed much more similar levels of social-visual engagement than fraternal twins,” Dr. Marrus said, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-0.95) for time spent looking at eyes, compared with 0.35 (95% CI, 0.07-0.59) for fraternal twins. Similar results were obtained for the caregiver questionnaire, suggesting strong genetic influences on both early reciprocal social behavior and SVE, said Dr. Marrus, also of Washington University.

At 36 months, 69 of the twin pairs were reevaluated. The investigators again found significantly greater SVE concordance for the identical twins: ICC, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.75-0.98), compared with ICC, 0.25 (95% CI, 0.0-0.60) for fraternal twins. They also found SVE patterns strongly correlated between 21 and 36 months for individual twins, indicating traitlike stability of this behavior over time.

“These two measures that are heritable, like autism, can be measured in a general population sample, which means they show good variability – potentially allowing the detection of subtle differences that may correspond to levels of risk for autism,” Dr. Marrus said. “By 18-21 months, the risk markers for later autism are already there – if you use a nuanced enough measure to detect them.”

Dr. Marrus said that while some practitioners have been able to reliably diagnose autism in children younger than 24 months, “it’s usually with the most severe cases,” she said. “But 18 months is a big time for social as well as language development, which becomes easier to measure at that point.”

A future direction for study, she said, “would be to go earlier. If we’re seeing this at 18 months, maybe we’d see it at 12.”

With autism, “early intervention is key, and even 6 months could make a difference,” Dr. Marrus said. “These two measures stand a really good chance of telling us important things about autism – which at early ages means better diagnostic prediction, measurement of severity and risk, and the potential to monitor responses to interventions.”

The National Institutes of Health supported the study through a grant to Dr. Constantino, and Dr. Marrus’s work was supported with a postdoctoral fellowship from the Autism Science Foundation. The investigators declared no relevant financial conflicts.

AT AACAP 2016

Targeting HER1/2 falls flat in bladder cancer trial

Patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (UBC) overexpressing HER1 or HER2 did not benefit from a course of lapatinib maintenance therapy following chemotherapy, a U.K.-based research group reported.

The phase III study, led by Thomas Powles, MD, of Queen Mary University of London, randomized 232 patients (mean age 71, about 75% male) with HER1- or HER2-positive metastatic UBC who had not progressed during platinum-based chemotherapy to placebo or lapatinib (Tykerb), an oral medication that targets HER1 and HER2 and is marketed for use in some breast cancers. The lapatinib-treated group saw no significant gains in either progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS), Dr. Powles and associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3468).

The median PFS for patients receiving lapatinib 1,500 mg daily was 4.5 months, compared with 5.1 months for the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43; P = .63), while OS after chemotherapy was 12.6 and 12 months, respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.70-1.31; P = .80). A subgroup of patients strongly positive for either or both receptors did not see significant OS or PFS benefit associated with lapatinib, a finding that the investigators said reinforced a lack of benefit.

While previous studies have indicated roles for both HER1 and HER2 in bladder cancer progression, targeting them “may not be of clinical benefit in UBC,” Dr. Powles and his colleagues wrote.

Patients with metastatic UBC have short overall survival following first-line chemotherapy, and few proven second-line treatment options exist besides additional chemotherapy, whose benefit is controversial, the researchers noted.

Despite this trial’s negative result for postchemotherapy maintenance treatment with lapatinib, Dr. Powles and his colleagues said their study, which screened 446 patients with metastatic UBC before randomizing slightly more than half, nonetheless shed some light on this difficult-to-treat patient group, including identifying three prognostic factors associated with poor outcome: radiologic progression during chemotherapy, visceral metastasis, and poor performance status. Also, they noted, 61% of the screened patients received cisplatin chemotherapy, and 48% had visceral metastasis, “which gives some insight into the current population of patients who receive chemotherapy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research U.K. sponsored the study. Dr. Powles and several coauthors disclosed financial support from GlaxoSmithKline and other pharmaceutical firms.

Patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (UBC) overexpressing HER1 or HER2 did not benefit from a course of lapatinib maintenance therapy following chemotherapy, a U.K.-based research group reported.

The phase III study, led by Thomas Powles, MD, of Queen Mary University of London, randomized 232 patients (mean age 71, about 75% male) with HER1- or HER2-positive metastatic UBC who had not progressed during platinum-based chemotherapy to placebo or lapatinib (Tykerb), an oral medication that targets HER1 and HER2 and is marketed for use in some breast cancers. The lapatinib-treated group saw no significant gains in either progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS), Dr. Powles and associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3468).

The median PFS for patients receiving lapatinib 1,500 mg daily was 4.5 months, compared with 5.1 months for the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43; P = .63), while OS after chemotherapy was 12.6 and 12 months, respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.70-1.31; P = .80). A subgroup of patients strongly positive for either or both receptors did not see significant OS or PFS benefit associated with lapatinib, a finding that the investigators said reinforced a lack of benefit.

While previous studies have indicated roles for both HER1 and HER2 in bladder cancer progression, targeting them “may not be of clinical benefit in UBC,” Dr. Powles and his colleagues wrote.

Patients with metastatic UBC have short overall survival following first-line chemotherapy, and few proven second-line treatment options exist besides additional chemotherapy, whose benefit is controversial, the researchers noted.

Despite this trial’s negative result for postchemotherapy maintenance treatment with lapatinib, Dr. Powles and his colleagues said their study, which screened 446 patients with metastatic UBC before randomizing slightly more than half, nonetheless shed some light on this difficult-to-treat patient group, including identifying three prognostic factors associated with poor outcome: radiologic progression during chemotherapy, visceral metastasis, and poor performance status. Also, they noted, 61% of the screened patients received cisplatin chemotherapy, and 48% had visceral metastasis, “which gives some insight into the current population of patients who receive chemotherapy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research U.K. sponsored the study. Dr. Powles and several coauthors disclosed financial support from GlaxoSmithKline and other pharmaceutical firms.

Patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer (UBC) overexpressing HER1 or HER2 did not benefit from a course of lapatinib maintenance therapy following chemotherapy, a U.K.-based research group reported.

The phase III study, led by Thomas Powles, MD, of Queen Mary University of London, randomized 232 patients (mean age 71, about 75% male) with HER1- or HER2-positive metastatic UBC who had not progressed during platinum-based chemotherapy to placebo or lapatinib (Tykerb), an oral medication that targets HER1 and HER2 and is marketed for use in some breast cancers. The lapatinib-treated group saw no significant gains in either progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS), Dr. Powles and associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3468).

The median PFS for patients receiving lapatinib 1,500 mg daily was 4.5 months, compared with 5.1 months for the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43; P = .63), while OS after chemotherapy was 12.6 and 12 months, respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.70-1.31; P = .80). A subgroup of patients strongly positive for either or both receptors did not see significant OS or PFS benefit associated with lapatinib, a finding that the investigators said reinforced a lack of benefit.

While previous studies have indicated roles for both HER1 and HER2 in bladder cancer progression, targeting them “may not be of clinical benefit in UBC,” Dr. Powles and his colleagues wrote.

Patients with metastatic UBC have short overall survival following first-line chemotherapy, and few proven second-line treatment options exist besides additional chemotherapy, whose benefit is controversial, the researchers noted.

Despite this trial’s negative result for postchemotherapy maintenance treatment with lapatinib, Dr. Powles and his colleagues said their study, which screened 446 patients with metastatic UBC before randomizing slightly more than half, nonetheless shed some light on this difficult-to-treat patient group, including identifying three prognostic factors associated with poor outcome: radiologic progression during chemotherapy, visceral metastasis, and poor performance status. Also, they noted, 61% of the screened patients received cisplatin chemotherapy, and 48% had visceral metastasis, “which gives some insight into the current population of patients who receive chemotherapy.”

GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research U.K. sponsored the study. Dr. Powles and several coauthors disclosed financial support from GlaxoSmithKline and other pharmaceutical firms.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Treatment with lapatinib after chemotherapy does not improve survival in people with HER1- or HER2-positive metastatic urothelial bladder cancer.

Major finding: Median progression-free survival for lapatinib was 4.5 months (95% CI, 2.8-5.4), compared with 5.1 (95% CI, 3.0-5.8) for placebo (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.81-1.43; P = .063).

Data source: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which 232 patients with HER1- or HER2-positive disease were assigned treatment with lapatinib (n = 116) or placebo (n = 116) after platinum-based chemotherapy.

Disclosures: GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research U.K. sponsored the study. Dr. Powles and several coauthors disclosed financial support from GlaxoSmithKline and other pharmaceutical firms.

Young adults and anxiety: Marriage may not be protective

A new study of anxiety disorders among young adults aged 18-24 shows that the illnesses are less prevalent among African American and Hispanic young adults, compared with whites. Furthermore, anxiety disorders are 1.5 times as prevalent among married people in this age group, compared with their unmarried peers.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cristiane S. Duarte, PhD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues looked at data from the 2012/2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative sample of U.S. households.

“We were trying to look specifically at young adulthood, which there’s emerging consensus to regard as a key developmental period,” said Dr. Duarte, whose research focuses on anxiety disorders in young adults. “It’s a period where several psychiatric disorders tend to become much more prevalent. Having untreated anxiety disorders at this age can put young adults at risk for worse outcomes down the line. If anxiety disorders can be resolved, a young adult’s trajectory can be quite different; it’s a time in life in which the right intervention can have a really big impact,” she said.

The NESARC III survey data used structured diagnostic interviews and DSM-5 criteria to assess anxiety disorders occurring in the past year. These included specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia.

For the most part, Dr. Duarte said, her group’s findings on anxiety disorders reflected earlier prevalence studies that had used DSM-IV criteria. Women were more likely than were men to report any past-year anxiety disorder (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.80-2.84), as were people with lower personal and family incomes. Rates of anxiety disorders were highest in groups with the lowest personal and family incomes, and among people neither employed nor in an educational program.

Dr. Duarte said in an interview that the latter findings were generally anticipated. However, the finding that African Americans and Hispanics at this age had lower risk relative to whites (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.40-0.67) and (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) was interesting, because it appeared to mirror the lower relative prevalence seen among adults in those two groups, rather than the higher prevalence seen among children in the same groups. More research will be needed, she said, to verify and, if correct, understand this reversing trend in prevalence seen between childhood and adulthood.

The study’s most unexpected finding, Dr. Duarte said, was that married individuals aged 18-24 had higher prevalence of anxiety (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05-2.26). “Across the board, marriage is protective for many health and mental health conditions,” Dr. Duarte said, but she acknowledged that many factors could be in play. Marriage might not, in fact, be protective in this age group; the institution might be reflective of cultural factors promoting early marriage; or the findings could reflect a selection into marriage possibly related to existing anxiety disorders.

“To better understand this finding, we will need to consider several complexities which are part of young adulthood as a unique developmental period,” she said.

Dr. Duarte’s and her colleagues’ study was funded by the Youth Anxiety Center at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. Three coauthors reported research support from pharmaceutical manufacturers and royalties from commercial publishers.

A new study of anxiety disorders among young adults aged 18-24 shows that the illnesses are less prevalent among African American and Hispanic young adults, compared with whites. Furthermore, anxiety disorders are 1.5 times as prevalent among married people in this age group, compared with their unmarried peers.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cristiane S. Duarte, PhD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues looked at data from the 2012/2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative sample of U.S. households.

“We were trying to look specifically at young adulthood, which there’s emerging consensus to regard as a key developmental period,” said Dr. Duarte, whose research focuses on anxiety disorders in young adults. “It’s a period where several psychiatric disorders tend to become much more prevalent. Having untreated anxiety disorders at this age can put young adults at risk for worse outcomes down the line. If anxiety disorders can be resolved, a young adult’s trajectory can be quite different; it’s a time in life in which the right intervention can have a really big impact,” she said.

The NESARC III survey data used structured diagnostic interviews and DSM-5 criteria to assess anxiety disorders occurring in the past year. These included specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia.

For the most part, Dr. Duarte said, her group’s findings on anxiety disorders reflected earlier prevalence studies that had used DSM-IV criteria. Women were more likely than were men to report any past-year anxiety disorder (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.80-2.84), as were people with lower personal and family incomes. Rates of anxiety disorders were highest in groups with the lowest personal and family incomes, and among people neither employed nor in an educational program.

Dr. Duarte said in an interview that the latter findings were generally anticipated. However, the finding that African Americans and Hispanics at this age had lower risk relative to whites (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.40-0.67) and (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) was interesting, because it appeared to mirror the lower relative prevalence seen among adults in those two groups, rather than the higher prevalence seen among children in the same groups. More research will be needed, she said, to verify and, if correct, understand this reversing trend in prevalence seen between childhood and adulthood.

The study’s most unexpected finding, Dr. Duarte said, was that married individuals aged 18-24 had higher prevalence of anxiety (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05-2.26). “Across the board, marriage is protective for many health and mental health conditions,” Dr. Duarte said, but she acknowledged that many factors could be in play. Marriage might not, in fact, be protective in this age group; the institution might be reflective of cultural factors promoting early marriage; or the findings could reflect a selection into marriage possibly related to existing anxiety disorders.

“To better understand this finding, we will need to consider several complexities which are part of young adulthood as a unique developmental period,” she said.

Dr. Duarte’s and her colleagues’ study was funded by the Youth Anxiety Center at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. Three coauthors reported research support from pharmaceutical manufacturers and royalties from commercial publishers.

A new study of anxiety disorders among young adults aged 18-24 shows that the illnesses are less prevalent among African American and Hispanic young adults, compared with whites. Furthermore, anxiety disorders are 1.5 times as prevalent among married people in this age group, compared with their unmarried peers.

For their research, presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Cristiane S. Duarte, PhD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York, and her colleagues looked at data from the 2012/2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a nationally representative sample of U.S. households.

“We were trying to look specifically at young adulthood, which there’s emerging consensus to regard as a key developmental period,” said Dr. Duarte, whose research focuses on anxiety disorders in young adults. “It’s a period where several psychiatric disorders tend to become much more prevalent. Having untreated anxiety disorders at this age can put young adults at risk for worse outcomes down the line. If anxiety disorders can be resolved, a young adult’s trajectory can be quite different; it’s a time in life in which the right intervention can have a really big impact,” she said.

The NESARC III survey data used structured diagnostic interviews and DSM-5 criteria to assess anxiety disorders occurring in the past year. These included specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia.

For the most part, Dr. Duarte said, her group’s findings on anxiety disorders reflected earlier prevalence studies that had used DSM-IV criteria. Women were more likely than were men to report any past-year anxiety disorder (odds ratio, 2.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.80-2.84), as were people with lower personal and family incomes. Rates of anxiety disorders were highest in groups with the lowest personal and family incomes, and among people neither employed nor in an educational program.

Dr. Duarte said in an interview that the latter findings were generally anticipated. However, the finding that African Americans and Hispanics at this age had lower risk relative to whites (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.40-0.67) and (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) was interesting, because it appeared to mirror the lower relative prevalence seen among adults in those two groups, rather than the higher prevalence seen among children in the same groups. More research will be needed, she said, to verify and, if correct, understand this reversing trend in prevalence seen between childhood and adulthood.

The study’s most unexpected finding, Dr. Duarte said, was that married individuals aged 18-24 had higher prevalence of anxiety (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05-2.26). “Across the board, marriage is protective for many health and mental health conditions,” Dr. Duarte said, but she acknowledged that many factors could be in play. Marriage might not, in fact, be protective in this age group; the institution might be reflective of cultural factors promoting early marriage; or the findings could reflect a selection into marriage possibly related to existing anxiety disorders.

“To better understand this finding, we will need to consider several complexities which are part of young adulthood as a unique developmental period,” she said.

Dr. Duarte’s and her colleagues’ study was funded by the Youth Anxiety Center at New York–Presbyterian Hospital. Three coauthors reported research support from pharmaceutical manufacturers and royalties from commercial publishers.

FROM AACAP 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: African Americans and Hispanics who are young adults have a lower risk relative to their white peers (OR, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.40-.067) and (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83). In addition, married individuals aged 18-24 had higher prevalence of anxiety (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05-2.26) than did their unmarried peers.

Data source: Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a nationally representative sample of U.S. households.

Disclosures: The Youth Anxiety Center at New York–Presbyterian Hospital funded the study. Three coauthors reported research support from pharmaceutical manufacturers and royalties from commercial publishers.

Homeless youth and risk: Untangling role of executive function

NEW YORK – Researchers studying the executive functioning ability of homeless youth have found that individuals with poor executive function report more alcohol abuse and dependence than do those with higher EF.

The results are from a study of 149 youth aged 18-22 years (53% female) living in shelters in Chicago. Subjects self-reported behaviors in a series of interviews that used three validated measures of executive function.

Scott J. Hunter, Ph.D., director of neuropsychology at the University of Chicago, presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Dr. Hunter said in an interview that the results help identify low executive functioning as both a likely contributor to risk-taking behavior and a potential target of interventions.

“We believe that the EF may be the primary concern, although the interaction [with drugs and alcohol] is something that we have to take into account,” he said. “One of the biggest issues here is how do you disentangle that executive piece with the use of substances?”

In this cohort, Dr. Hunter said, about 75% of subjects were African American and an additional 25% or so were mixed race or Latino. About half comprised a sexual minority (gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender). “Many had been kicked out of their homes,” he said.

Close to 80% of the youth in the study used cannabis regularly, and three-quarters used alcohol. The group with low EF used the greatest level of substances regularly. Admission of unprotected sexual intercourse was highest among the heavier substance users as well, suggesting “a reliance on substances to reduce sensitivity to the risks they were taking,” said Dr. Hunter, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, and pediatrics at the university.

He said the study “is providing some support for our hypothesis that the less successful these young people are in their development of EF, particularly around inhibition, the more likely it is they are going to be engaging in risk-taking behaviors that lead to cycles of more challenge” and development of psychopathology.

The researchers are considering an intervention for this population derived from EF interventions for use with adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In their current shelter environments, he said, the youth are “already undergoing programs to learn adaptive functioning to be more successful, and we’re thinking of adding an executive component where they tie the decision-making component to what they want as outcomes.”

The prefrontal cortex of the brain, which controls executive function, is not yet fully developed in adolescence, and studies have shown that youth growing up in impoverished environments have decreases or alterations in cortical development (Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 Aug 17;6:238). “What we have to think about is that we’re still at a [developmental] point where this enhancement and myelination is taking place – into the mid-20s, in fact. We may find that [an intervention] can help them better activate that,” Dr. Hunter said.

The lead author on this study was Joshua Piche, a medical student at the University of Chicago.

Dr. Hunter also is collaborating with epidemiologist John Schneider, MD, MPH, of the University of Chicago, in a study of 600 young black men who have sex with men. The researchers are looking at drug-, alcohol-related, and sexual decision-making in that cohort, about a quarter of whom are homeless. The study includes functional magnetic resonance imaging in a subgroup of subjects.

Currently, as many as 2 million U.S. youth are estimated to be living on the streets, in shelters, or in other temporary housing environments.

NEW YORK – Researchers studying the executive functioning ability of homeless youth have found that individuals with poor executive function report more alcohol abuse and dependence than do those with higher EF.

The results are from a study of 149 youth aged 18-22 years (53% female) living in shelters in Chicago. Subjects self-reported behaviors in a series of interviews that used three validated measures of executive function.

Scott J. Hunter, Ph.D., director of neuropsychology at the University of Chicago, presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Dr. Hunter said in an interview that the results help identify low executive functioning as both a likely contributor to risk-taking behavior and a potential target of interventions.

“We believe that the EF may be the primary concern, although the interaction [with drugs and alcohol] is something that we have to take into account,” he said. “One of the biggest issues here is how do you disentangle that executive piece with the use of substances?”

In this cohort, Dr. Hunter said, about 75% of subjects were African American and an additional 25% or so were mixed race or Latino. About half comprised a sexual minority (gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender). “Many had been kicked out of their homes,” he said.

Close to 80% of the youth in the study used cannabis regularly, and three-quarters used alcohol. The group with low EF used the greatest level of substances regularly. Admission of unprotected sexual intercourse was highest among the heavier substance users as well, suggesting “a reliance on substances to reduce sensitivity to the risks they were taking,” said Dr. Hunter, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, and pediatrics at the university.

He said the study “is providing some support for our hypothesis that the less successful these young people are in their development of EF, particularly around inhibition, the more likely it is they are going to be engaging in risk-taking behaviors that lead to cycles of more challenge” and development of psychopathology.

The researchers are considering an intervention for this population derived from EF interventions for use with adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In their current shelter environments, he said, the youth are “already undergoing programs to learn adaptive functioning to be more successful, and we’re thinking of adding an executive component where they tie the decision-making component to what they want as outcomes.”

The prefrontal cortex of the brain, which controls executive function, is not yet fully developed in adolescence, and studies have shown that youth growing up in impoverished environments have decreases or alterations in cortical development (Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 Aug 17;6:238). “What we have to think about is that we’re still at a [developmental] point where this enhancement and myelination is taking place – into the mid-20s, in fact. We may find that [an intervention] can help them better activate that,” Dr. Hunter said.

The lead author on this study was Joshua Piche, a medical student at the University of Chicago.

Dr. Hunter also is collaborating with epidemiologist John Schneider, MD, MPH, of the University of Chicago, in a study of 600 young black men who have sex with men. The researchers are looking at drug-, alcohol-related, and sexual decision-making in that cohort, about a quarter of whom are homeless. The study includes functional magnetic resonance imaging in a subgroup of subjects.

Currently, as many as 2 million U.S. youth are estimated to be living on the streets, in shelters, or in other temporary housing environments.

NEW YORK – Researchers studying the executive functioning ability of homeless youth have found that individuals with poor executive function report more alcohol abuse and dependence than do those with higher EF.

The results are from a study of 149 youth aged 18-22 years (53% female) living in shelters in Chicago. Subjects self-reported behaviors in a series of interviews that used three validated measures of executive function.

Scott J. Hunter, Ph.D., director of neuropsychology at the University of Chicago, presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Dr. Hunter said in an interview that the results help identify low executive functioning as both a likely contributor to risk-taking behavior and a potential target of interventions.

“We believe that the EF may be the primary concern, although the interaction [with drugs and alcohol] is something that we have to take into account,” he said. “One of the biggest issues here is how do you disentangle that executive piece with the use of substances?”

In this cohort, Dr. Hunter said, about 75% of subjects were African American and an additional 25% or so were mixed race or Latino. About half comprised a sexual minority (gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender). “Many had been kicked out of their homes,” he said.

Close to 80% of the youth in the study used cannabis regularly, and three-quarters used alcohol. The group with low EF used the greatest level of substances regularly. Admission of unprotected sexual intercourse was highest among the heavier substance users as well, suggesting “a reliance on substances to reduce sensitivity to the risks they were taking,” said Dr. Hunter, also a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, and pediatrics at the university.

He said the study “is providing some support for our hypothesis that the less successful these young people are in their development of EF, particularly around inhibition, the more likely it is they are going to be engaging in risk-taking behaviors that lead to cycles of more challenge” and development of psychopathology.

The researchers are considering an intervention for this population derived from EF interventions for use with adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In their current shelter environments, he said, the youth are “already undergoing programs to learn adaptive functioning to be more successful, and we’re thinking of adding an executive component where they tie the decision-making component to what they want as outcomes.”

The prefrontal cortex of the brain, which controls executive function, is not yet fully developed in adolescence, and studies have shown that youth growing up in impoverished environments have decreases or alterations in cortical development (Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 Aug 17;6:238). “What we have to think about is that we’re still at a [developmental] point where this enhancement and myelination is taking place – into the mid-20s, in fact. We may find that [an intervention] can help them better activate that,” Dr. Hunter said.

The lead author on this study was Joshua Piche, a medical student at the University of Chicago.

Dr. Hunter also is collaborating with epidemiologist John Schneider, MD, MPH, of the University of Chicago, in a study of 600 young black men who have sex with men. The researchers are looking at drug-, alcohol-related, and sexual decision-making in that cohort, about a quarter of whom are homeless. The study includes functional magnetic resonance imaging in a subgroup of subjects.

Currently, as many as 2 million U.S. youth are estimated to be living on the streets, in shelters, or in other temporary housing environments.

Experts outline phenotype approach to rosacea

A phenotype approach should be used to diagnose and manage rosacea, according to an expert panel that included 17 dermatologists from North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

“As individual treatments do not address multiple features simultaneously, consideration of specific phenotypical issues facilitates individualized optimization of rosacea,” the panel concluded. As individual presentations of rosacea can span more than one of the currently defined disease subtypes, and vary widely in severity, dermatologists have long expressed a need to move to a phenotype-based system for diagnosis and classification.

The goal of the panel was “to establish international consensus on diagnosis and severity determination to improve outcomes” for people with rosacea (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122).

Jerry L. Tan, MD, of the University of Western Ontario, Windsor, and coauthors, explained why they considered a transition to the phenotype-based approach important: “Subtype classification may not fully cover the range of clinical presentations and is likely to confound severity assessment, whereas a phenotype-based approach could improve patient outcomes by addressing an individual patient’s clinical presentation and concerns.”