User login

Health data breaches compromised 29 million patient records in 2010-2013

Some 29 million private patient health records were compromised between 2010 and the end of 2013 – mostly as a result of criminal activity, say researchers, who described their findings as a likely underestimate of the magnitude of the problem.

In a research letter published April 14 in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2252), Dr. Vincent Liu of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University, evaluated U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reports of data breaches involving 500 or more patient records covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Of the 949 reported breach events during the 4-year study period, 67% involved electronic media while about 20% were attributed to paper records. Laptop or portable device theft accounted for 33% of all breaches reported.

Importantly, the frequency of breaches from hacking and unauthorized access increased significantly during the study period (from 12% in 2010 to 27% in 2013), and breaches involving external vendors represented 29% of all incidents.

“Given the rapid expansion in electronic health record deployment since 2012, as well as the expected increase in cloud-based services provided by vendors supporting predictive analytics, personal health records, health-related sensors, and gene-sequencing technology, the frequency and scope of electronic health care data breaches are likely to increase,” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote.

“Our study was limited to breaches that were already recognized, reported, and affecting at least 500 individuals [as required by the HITECH Act of 2009],” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote. “Therefore, our study likely underestimated the true number of health care data breaches occurring each year.” The study was funded by Permanente Medical Group and the National Institutes of Health. None of its authors reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Dr. Liu and his colleagues’ research makes clear that the personal health information of patients in the United States is not safe, and it needs to be. Loss of trust in an electronic health information system could seriously undermine efforts to improve health and health care in the United States. The question is what to do.

Part of the responsibility lies with the private custodians of health data, mostly clinicians, health care organizations, and insurers. Although malicious hacking gets the most media attention, the majority of data breaches result from a much more mundane and correctable problem: the failure of covered entities to observe what might be called good data hygiene.

But part of the responsibility also lies with policy makers. Health care organizations and practitioners bemoan HIPAA’s requirements, but in fact the law is antiquated and inadequate to protect patients’ health care privacy and security. The fact that HIPAA regulates only certain entities that hold health data, rather than regulating health data wherever those data reside, seems illogical in today’s digital world.

Dr. David Blumenthal is president of the Commonwealth Fund in New York; Deven McGraw is a health care attorney in Washington. Their comments were made in an editorial accompanying the study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2746]). They reported no conflicts of interest related to their comments.

Dr. Liu and his colleagues’ research makes clear that the personal health information of patients in the United States is not safe, and it needs to be. Loss of trust in an electronic health information system could seriously undermine efforts to improve health and health care in the United States. The question is what to do.

Part of the responsibility lies with the private custodians of health data, mostly clinicians, health care organizations, and insurers. Although malicious hacking gets the most media attention, the majority of data breaches result from a much more mundane and correctable problem: the failure of covered entities to observe what might be called good data hygiene.

But part of the responsibility also lies with policy makers. Health care organizations and practitioners bemoan HIPAA’s requirements, but in fact the law is antiquated and inadequate to protect patients’ health care privacy and security. The fact that HIPAA regulates only certain entities that hold health data, rather than regulating health data wherever those data reside, seems illogical in today’s digital world.

Dr. David Blumenthal is president of the Commonwealth Fund in New York; Deven McGraw is a health care attorney in Washington. Their comments were made in an editorial accompanying the study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2746]). They reported no conflicts of interest related to their comments.

Dr. Liu and his colleagues’ research makes clear that the personal health information of patients in the United States is not safe, and it needs to be. Loss of trust in an electronic health information system could seriously undermine efforts to improve health and health care in the United States. The question is what to do.

Part of the responsibility lies with the private custodians of health data, mostly clinicians, health care organizations, and insurers. Although malicious hacking gets the most media attention, the majority of data breaches result from a much more mundane and correctable problem: the failure of covered entities to observe what might be called good data hygiene.

But part of the responsibility also lies with policy makers. Health care organizations and practitioners bemoan HIPAA’s requirements, but in fact the law is antiquated and inadequate to protect patients’ health care privacy and security. The fact that HIPAA regulates only certain entities that hold health data, rather than regulating health data wherever those data reside, seems illogical in today’s digital world.

Dr. David Blumenthal is president of the Commonwealth Fund in New York; Deven McGraw is a health care attorney in Washington. Their comments were made in an editorial accompanying the study (JAMA 2015 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2746]). They reported no conflicts of interest related to their comments.

Some 29 million private patient health records were compromised between 2010 and the end of 2013 – mostly as a result of criminal activity, say researchers, who described their findings as a likely underestimate of the magnitude of the problem.

In a research letter published April 14 in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2252), Dr. Vincent Liu of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University, evaluated U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reports of data breaches involving 500 or more patient records covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Of the 949 reported breach events during the 4-year study period, 67% involved electronic media while about 20% were attributed to paper records. Laptop or portable device theft accounted for 33% of all breaches reported.

Importantly, the frequency of breaches from hacking and unauthorized access increased significantly during the study period (from 12% in 2010 to 27% in 2013), and breaches involving external vendors represented 29% of all incidents.

“Given the rapid expansion in electronic health record deployment since 2012, as well as the expected increase in cloud-based services provided by vendors supporting predictive analytics, personal health records, health-related sensors, and gene-sequencing technology, the frequency and scope of electronic health care data breaches are likely to increase,” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote.

“Our study was limited to breaches that were already recognized, reported, and affecting at least 500 individuals [as required by the HITECH Act of 2009],” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote. “Therefore, our study likely underestimated the true number of health care data breaches occurring each year.” The study was funded by Permanente Medical Group and the National Institutes of Health. None of its authors reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

Some 29 million private patient health records were compromised between 2010 and the end of 2013 – mostly as a result of criminal activity, say researchers, who described their findings as a likely underestimate of the magnitude of the problem.

In a research letter published April 14 in JAMA (doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2252), Dr. Vincent Liu of Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., and his colleagues at Stanford (Calif.) University, evaluated U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reports of data breaches involving 500 or more patient records covered under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Of the 949 reported breach events during the 4-year study period, 67% involved electronic media while about 20% were attributed to paper records. Laptop or portable device theft accounted for 33% of all breaches reported.

Importantly, the frequency of breaches from hacking and unauthorized access increased significantly during the study period (from 12% in 2010 to 27% in 2013), and breaches involving external vendors represented 29% of all incidents.

“Given the rapid expansion in electronic health record deployment since 2012, as well as the expected increase in cloud-based services provided by vendors supporting predictive analytics, personal health records, health-related sensors, and gene-sequencing technology, the frequency and scope of electronic health care data breaches are likely to increase,” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote.

“Our study was limited to breaches that were already recognized, reported, and affecting at least 500 individuals [as required by the HITECH Act of 2009],” Dr. Liu and colleagues wrote. “Therefore, our study likely underestimated the true number of health care data breaches occurring each year.” The study was funded by Permanente Medical Group and the National Institutes of Health. None of its authors reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Breaches of electronic patient data are becoming more frequent.

Major finding: Data from 29.1 million HIPAA-protected patient health records were compromised by computer theft, hacking, inappropriate electronic dissemination, and other causes over a 4-year period.

Data source: A review of HHS records on health data breaches involving 500 or more individuals occurring from 2010 through the end of 2013.

Disclosures: None.

Poor control of CVD risk factors raises morbidity, mortality risk in diabetes

Optimal control of glucose, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and smoking in adults with diabetes could result in substantial reductions of cardiovascular risk, according to results from a large cohort study of diabetes patients with and without underlying cardiovascular disease.

CV events and deaths associated with inadequate control of any of these four modifiable risk factors were about 11% and 3%, respectively, for subjects with baseline CVD, and 34% and 7%, respectively, for those without it.

Though risk was much higher for those with CVD, as expected, more attention to these traditional CVD risk factors in all diabetic patients – with or without CVD – would significantly reduce CVD-related morbidity and mortality, investigators concluded.

For their research, published online in Diabetes Care, epidemiologist Gabriela Vasquez-Benitez, Ph.D., of the Health Partners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis and her associates identified 859,617 patients with diabetes (31% with CVD) receiving treatment at a network of 11 U.S. health centers for 6 months or more, with mean follow-up of 5 years. About half of patients were female, and 45% were white. Risk factors were defined as LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥7%, blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg, or smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and associates used a regression analysis to quantify the contributions each risk factor made to CVD risk and type of CV event in both patient groups.

In patients without CVD (n = 593,167), the vast majority had HbA1c, BP, and LDL-C not at goal or were current smokers. Inadequately controlled LDL cholesterol was associated with 19.6% of myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome (95% confidence interval, 18.7-20.5), and 13.7% of strokes. Smoking was associated with 3.8% of all CV events, while inadequately controlled blood pressure was associated with 11.6% of strokes. Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and colleagues found an increased CV risk for HbA1c above 9%, but no increased risk for HbA1c of 7%-7.9%, compared with 6.5%-6.9%. This finding supports current guidelines recommending HbA1c targets below 7% or 8% for patients with diabetes, according to the investigators (Diab. Care 2015 Feb. 20 [doi:10.2337/dc14-1877]).

In subjects with diabetes and CVD, 7% of stroke was found attributable to inadequate blood pressure control and 5.9% to poor glycemic control. Smoking was the only factor seen associated with an increase in all-cause mortality in this patient group, with 2.6% of deaths seen linked to smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and her colleagues noted in their analysis that a substantial share of risk could not be attributed to the modifiable factors investigated in their study, raising the possibility that “unidentified genetic, metabolic, or psychosocial risk factors may affect risk.”

The investigators noted as limitations of their study the fact that risk factors and comorbidities were assessed at baseline and may have changed during follow-up, and that data were obtained from routine care settings with varying time intervals. Patients with type I diabetes may have been included in the cohort due to difficulties distinguishing diabetes types in patient records, they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. None of its authors reported conflicts of interest.

Optimal control of glucose, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and smoking in adults with diabetes could result in substantial reductions of cardiovascular risk, according to results from a large cohort study of diabetes patients with and without underlying cardiovascular disease.

CV events and deaths associated with inadequate control of any of these four modifiable risk factors were about 11% and 3%, respectively, for subjects with baseline CVD, and 34% and 7%, respectively, for those without it.

Though risk was much higher for those with CVD, as expected, more attention to these traditional CVD risk factors in all diabetic patients – with or without CVD – would significantly reduce CVD-related morbidity and mortality, investigators concluded.

For their research, published online in Diabetes Care, epidemiologist Gabriela Vasquez-Benitez, Ph.D., of the Health Partners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis and her associates identified 859,617 patients with diabetes (31% with CVD) receiving treatment at a network of 11 U.S. health centers for 6 months or more, with mean follow-up of 5 years. About half of patients were female, and 45% were white. Risk factors were defined as LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥7%, blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg, or smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and associates used a regression analysis to quantify the contributions each risk factor made to CVD risk and type of CV event in both patient groups.

In patients without CVD (n = 593,167), the vast majority had HbA1c, BP, and LDL-C not at goal or were current smokers. Inadequately controlled LDL cholesterol was associated with 19.6% of myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome (95% confidence interval, 18.7-20.5), and 13.7% of strokes. Smoking was associated with 3.8% of all CV events, while inadequately controlled blood pressure was associated with 11.6% of strokes. Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and colleagues found an increased CV risk for HbA1c above 9%, but no increased risk for HbA1c of 7%-7.9%, compared with 6.5%-6.9%. This finding supports current guidelines recommending HbA1c targets below 7% or 8% for patients with diabetes, according to the investigators (Diab. Care 2015 Feb. 20 [doi:10.2337/dc14-1877]).

In subjects with diabetes and CVD, 7% of stroke was found attributable to inadequate blood pressure control and 5.9% to poor glycemic control. Smoking was the only factor seen associated with an increase in all-cause mortality in this patient group, with 2.6% of deaths seen linked to smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and her colleagues noted in their analysis that a substantial share of risk could not be attributed to the modifiable factors investigated in their study, raising the possibility that “unidentified genetic, metabolic, or psychosocial risk factors may affect risk.”

The investigators noted as limitations of their study the fact that risk factors and comorbidities were assessed at baseline and may have changed during follow-up, and that data were obtained from routine care settings with varying time intervals. Patients with type I diabetes may have been included in the cohort due to difficulties distinguishing diabetes types in patient records, they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. None of its authors reported conflicts of interest.

Optimal control of glucose, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and smoking in adults with diabetes could result in substantial reductions of cardiovascular risk, according to results from a large cohort study of diabetes patients with and without underlying cardiovascular disease.

CV events and deaths associated with inadequate control of any of these four modifiable risk factors were about 11% and 3%, respectively, for subjects with baseline CVD, and 34% and 7%, respectively, for those without it.

Though risk was much higher for those with CVD, as expected, more attention to these traditional CVD risk factors in all diabetic patients – with or without CVD – would significantly reduce CVD-related morbidity and mortality, investigators concluded.

For their research, published online in Diabetes Care, epidemiologist Gabriela Vasquez-Benitez, Ph.D., of the Health Partners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis and her associates identified 859,617 patients with diabetes (31% with CVD) receiving treatment at a network of 11 U.S. health centers for 6 months or more, with mean follow-up of 5 years. About half of patients were female, and 45% were white. Risk factors were defined as LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥7%, blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg, or smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and associates used a regression analysis to quantify the contributions each risk factor made to CVD risk and type of CV event in both patient groups.

In patients without CVD (n = 593,167), the vast majority had HbA1c, BP, and LDL-C not at goal or were current smokers. Inadequately controlled LDL cholesterol was associated with 19.6% of myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome (95% confidence interval, 18.7-20.5), and 13.7% of strokes. Smoking was associated with 3.8% of all CV events, while inadequately controlled blood pressure was associated with 11.6% of strokes. Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and colleagues found an increased CV risk for HbA1c above 9%, but no increased risk for HbA1c of 7%-7.9%, compared with 6.5%-6.9%. This finding supports current guidelines recommending HbA1c targets below 7% or 8% for patients with diabetes, according to the investigators (Diab. Care 2015 Feb. 20 [doi:10.2337/dc14-1877]).

In subjects with diabetes and CVD, 7% of stroke was found attributable to inadequate blood pressure control and 5.9% to poor glycemic control. Smoking was the only factor seen associated with an increase in all-cause mortality in this patient group, with 2.6% of deaths seen linked to smoking.

Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and her colleagues noted in their analysis that a substantial share of risk could not be attributed to the modifiable factors investigated in their study, raising the possibility that “unidentified genetic, metabolic, or psychosocial risk factors may affect risk.”

The investigators noted as limitations of their study the fact that risk factors and comorbidities were assessed at baseline and may have changed during follow-up, and that data were obtained from routine care settings with varying time intervals. Patients with type I diabetes may have been included in the cohort due to difficulties distinguishing diabetes types in patient records, they said.

The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. None of its authors reported conflicts of interest.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Key clinical point: Optimal control of cardiac risk factors in patients with diabetes can substantially lower their CV risks.

Major finding: Traditional cardiovascular risk factors contribute to more than one-third of CV morbidity in patients with diabetes without known underlying cardiovascular disease.

Data source: More than 850,000 patients with diabetes treated at 11 linked healthcare centers between 2005 and 2011, of whom nearly 600,000 had no CVD at baseline.

Disclosures: Dr. Vasquez-Benitez and her associates reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Minimal invasiveness in obesity: Perspectives for GIs and surgeons

“My career goal has been to do things in an increasingly less-invasive manner,” says Dr. Robert D. Fanelli, MHA, chief of minimally invasive surgery and surgical endoscopy at The Guthrie Clinic in Sayre, Penn.

At the 2015 AGA Technology Summit, Dr. Fanelli will moderate a seminar on new technologies in obesity that, he says, is all about finding “the next step in reducing invasiveness” by bringing highly qualified endoscopic practitioners and minimally invasive surgeons together to talk about newly approved devices, devices in development, and new procedures.

While intragastric balloons, duodenal-jejunal sleeves, vagal nerve–blocking devices, endoscopic suturing, and new stenting techniques are all hot topics, “the reality is there are very few people doing any of this high-end stuff on a daily clinical basis; our goal is to change that.”

The seminar “is not just for the person who wants to know what the future will look like, but for surgeons and gastroenterologists looking to actually do some of these things now,” Dr. Fanelli said. It will include, besides the practice discussions, talks on marketing nonsurgical bariatric products and a perspective on obesity devices from insurers, investors, and representatives from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Though obesity remains largely in the surgical realm – “Roux-en-Y isn’t going away,” Dr. Fanelli said – some of the new devices promise to tilt treatment away from the purely surgical approach toward an endoscopic one. Gastroenterologists are enthusiastic about the new wave of obesity devices that can be placed without surgery, bringing their field closer to the cutting edge of weight-loss intervention, Dr. Fanelli said, but cautioned that obesity always necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, whether treated surgically or medically.

“All of the enthusiasm about new procedures to be done has to occur within the context of a multidisciplinary weight-loss clinic with psychological evaluation, behavioral coaching, smoking cessation, and other components essential to improving population health,” he said.

Dr. Fanelli’s own surgical practice incorporates basic and advanced endoscopic procedures. “I’ve dedicated my career to running this kind of hybrid practice, and there are growing numbers of us out there,” said Dr. Fanelli.

One speaker at the seminar, Dr. Dmitry Oleynikov of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha will discuss outcome measures for bariatric procedures.

Dr. Fanelli pointed to Dr. Oleynikov as a surgeon emblematic of the increasingly fluid barriers between the fields of gastroenterology and surgery. “He’s a really inventive guy who has developed equipment, including a microrobotic surgical platform, and he’s a bariatric surgeon involved with endoscopy. I like the way he thinks, I like the way he’s designed his career path, and I think that he can help us establish creative discussion.”

Like many participants who will attend the summit, Dr. Fanelli is extensively involved in new product development – a key area of interest to participants at the seminar, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

One device Dr. Fanelli conceptualized, an intestinal sleeve that can be tuned using radiofrequency from outside, “was too expensive to produce, so it’s on the shelf right now.” Dr. Fanelli noted that this was the nature of the device development process – ideas can hang around a while until the time is right to revisit them.

The science behind the recently approved vagal nerve–blocking device is based on data and concepts accumulated over time, he added. “If you go back to some of the initial research that was done after bypass, with the identification of hormonal pathways and fat-burning triggers, that’s partly where stimulation devices came from,” he said. “A lot of ideas have been percolating for 5-15 years, and it gets to the point where you begin to see something concrete that emerges from it.”

Speaking directly to that idea – how to think about new obesity devices in a regulatory and research context – will be FDA’s Dr. Martha Betz. “Physicians, surgeons, and industry alike all want to know what the pathways to market are,” Dr. Fanelli said, adding that Dr. Betz and other members of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health can help “outline a pathway by which the FDA can determine the safety of a device, but then it is up to insurers to recognize their responsibility in this process as well and to transparently outline the pathway to payment, even if only for limited use in collecting larger series of cases.”

This is where the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology comes in – to guide medical device and therapeutics innovators through the technology development and complex adoption process. The center also has a registry initiative that helps companies identify and gather the data and evidence required by physician members, payers, and regulatory agencies to demonstrate that the technologies improve patient outcomes and hopefully reduce costs to the system.

“This is the real benefit of the AGA registry initiative, to gather data, and with this unique conference; having all the stakeholders in one room is the best way of modernizing an outdated process that allows disruptive technologies to die on the vine,” Dr. Fanelli said.

“My career goal has been to do things in an increasingly less-invasive manner,” says Dr. Robert D. Fanelli, MHA, chief of minimally invasive surgery and surgical endoscopy at The Guthrie Clinic in Sayre, Penn.

At the 2015 AGA Technology Summit, Dr. Fanelli will moderate a seminar on new technologies in obesity that, he says, is all about finding “the next step in reducing invasiveness” by bringing highly qualified endoscopic practitioners and minimally invasive surgeons together to talk about newly approved devices, devices in development, and new procedures.

While intragastric balloons, duodenal-jejunal sleeves, vagal nerve–blocking devices, endoscopic suturing, and new stenting techniques are all hot topics, “the reality is there are very few people doing any of this high-end stuff on a daily clinical basis; our goal is to change that.”

The seminar “is not just for the person who wants to know what the future will look like, but for surgeons and gastroenterologists looking to actually do some of these things now,” Dr. Fanelli said. It will include, besides the practice discussions, talks on marketing nonsurgical bariatric products and a perspective on obesity devices from insurers, investors, and representatives from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Though obesity remains largely in the surgical realm – “Roux-en-Y isn’t going away,” Dr. Fanelli said – some of the new devices promise to tilt treatment away from the purely surgical approach toward an endoscopic one. Gastroenterologists are enthusiastic about the new wave of obesity devices that can be placed without surgery, bringing their field closer to the cutting edge of weight-loss intervention, Dr. Fanelli said, but cautioned that obesity always necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, whether treated surgically or medically.

“All of the enthusiasm about new procedures to be done has to occur within the context of a multidisciplinary weight-loss clinic with psychological evaluation, behavioral coaching, smoking cessation, and other components essential to improving population health,” he said.

Dr. Fanelli’s own surgical practice incorporates basic and advanced endoscopic procedures. “I’ve dedicated my career to running this kind of hybrid practice, and there are growing numbers of us out there,” said Dr. Fanelli.

One speaker at the seminar, Dr. Dmitry Oleynikov of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha will discuss outcome measures for bariatric procedures.

Dr. Fanelli pointed to Dr. Oleynikov as a surgeon emblematic of the increasingly fluid barriers between the fields of gastroenterology and surgery. “He’s a really inventive guy who has developed equipment, including a microrobotic surgical platform, and he’s a bariatric surgeon involved with endoscopy. I like the way he thinks, I like the way he’s designed his career path, and I think that he can help us establish creative discussion.”

Like many participants who will attend the summit, Dr. Fanelli is extensively involved in new product development – a key area of interest to participants at the seminar, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

One device Dr. Fanelli conceptualized, an intestinal sleeve that can be tuned using radiofrequency from outside, “was too expensive to produce, so it’s on the shelf right now.” Dr. Fanelli noted that this was the nature of the device development process – ideas can hang around a while until the time is right to revisit them.

The science behind the recently approved vagal nerve–blocking device is based on data and concepts accumulated over time, he added. “If you go back to some of the initial research that was done after bypass, with the identification of hormonal pathways and fat-burning triggers, that’s partly where stimulation devices came from,” he said. “A lot of ideas have been percolating for 5-15 years, and it gets to the point where you begin to see something concrete that emerges from it.”

Speaking directly to that idea – how to think about new obesity devices in a regulatory and research context – will be FDA’s Dr. Martha Betz. “Physicians, surgeons, and industry alike all want to know what the pathways to market are,” Dr. Fanelli said, adding that Dr. Betz and other members of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health can help “outline a pathway by which the FDA can determine the safety of a device, but then it is up to insurers to recognize their responsibility in this process as well and to transparently outline the pathway to payment, even if only for limited use in collecting larger series of cases.”

This is where the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology comes in – to guide medical device and therapeutics innovators through the technology development and complex adoption process. The center also has a registry initiative that helps companies identify and gather the data and evidence required by physician members, payers, and regulatory agencies to demonstrate that the technologies improve patient outcomes and hopefully reduce costs to the system.

“This is the real benefit of the AGA registry initiative, to gather data, and with this unique conference; having all the stakeholders in one room is the best way of modernizing an outdated process that allows disruptive technologies to die on the vine,” Dr. Fanelli said.

“My career goal has been to do things in an increasingly less-invasive manner,” says Dr. Robert D. Fanelli, MHA, chief of minimally invasive surgery and surgical endoscopy at The Guthrie Clinic in Sayre, Penn.

At the 2015 AGA Technology Summit, Dr. Fanelli will moderate a seminar on new technologies in obesity that, he says, is all about finding “the next step in reducing invasiveness” by bringing highly qualified endoscopic practitioners and minimally invasive surgeons together to talk about newly approved devices, devices in development, and new procedures.

While intragastric balloons, duodenal-jejunal sleeves, vagal nerve–blocking devices, endoscopic suturing, and new stenting techniques are all hot topics, “the reality is there are very few people doing any of this high-end stuff on a daily clinical basis; our goal is to change that.”

The seminar “is not just for the person who wants to know what the future will look like, but for surgeons and gastroenterologists looking to actually do some of these things now,” Dr. Fanelli said. It will include, besides the practice discussions, talks on marketing nonsurgical bariatric products and a perspective on obesity devices from insurers, investors, and representatives from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Though obesity remains largely in the surgical realm – “Roux-en-Y isn’t going away,” Dr. Fanelli said – some of the new devices promise to tilt treatment away from the purely surgical approach toward an endoscopic one. Gastroenterologists are enthusiastic about the new wave of obesity devices that can be placed without surgery, bringing their field closer to the cutting edge of weight-loss intervention, Dr. Fanelli said, but cautioned that obesity always necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, whether treated surgically or medically.

“All of the enthusiasm about new procedures to be done has to occur within the context of a multidisciplinary weight-loss clinic with psychological evaluation, behavioral coaching, smoking cessation, and other components essential to improving population health,” he said.

Dr. Fanelli’s own surgical practice incorporates basic and advanced endoscopic procedures. “I’ve dedicated my career to running this kind of hybrid practice, and there are growing numbers of us out there,” said Dr. Fanelli.

One speaker at the seminar, Dr. Dmitry Oleynikov of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha will discuss outcome measures for bariatric procedures.

Dr. Fanelli pointed to Dr. Oleynikov as a surgeon emblematic of the increasingly fluid barriers between the fields of gastroenterology and surgery. “He’s a really inventive guy who has developed equipment, including a microrobotic surgical platform, and he’s a bariatric surgeon involved with endoscopy. I like the way he thinks, I like the way he’s designed his career path, and I think that he can help us establish creative discussion.”

Like many participants who will attend the summit, Dr. Fanelli is extensively involved in new product development – a key area of interest to participants at the seminar, which is sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

One device Dr. Fanelli conceptualized, an intestinal sleeve that can be tuned using radiofrequency from outside, “was too expensive to produce, so it’s on the shelf right now.” Dr. Fanelli noted that this was the nature of the device development process – ideas can hang around a while until the time is right to revisit them.

The science behind the recently approved vagal nerve–blocking device is based on data and concepts accumulated over time, he added. “If you go back to some of the initial research that was done after bypass, with the identification of hormonal pathways and fat-burning triggers, that’s partly where stimulation devices came from,” he said. “A lot of ideas have been percolating for 5-15 years, and it gets to the point where you begin to see something concrete that emerges from it.”

Speaking directly to that idea – how to think about new obesity devices in a regulatory and research context – will be FDA’s Dr. Martha Betz. “Physicians, surgeons, and industry alike all want to know what the pathways to market are,” Dr. Fanelli said, adding that Dr. Betz and other members of the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health can help “outline a pathway by which the FDA can determine the safety of a device, but then it is up to insurers to recognize their responsibility in this process as well and to transparently outline the pathway to payment, even if only for limited use in collecting larger series of cases.”

This is where the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology comes in – to guide medical device and therapeutics innovators through the technology development and complex adoption process. The center also has a registry initiative that helps companies identify and gather the data and evidence required by physician members, payers, and regulatory agencies to demonstrate that the technologies improve patient outcomes and hopefully reduce costs to the system.

“This is the real benefit of the AGA registry initiative, to gather data, and with this unique conference; having all the stakeholders in one room is the best way of modernizing an outdated process that allows disruptive technologies to die on the vine,” Dr. Fanelli said.

When to use SLIT and SCID in atopic dermatitis

HOUSTON – Whether atopic dermatitis should be treated with allergen immunotherapy is still a matter of debate, as high-quality trial evidence remains scant, but clinical practice is starting to recognize the potential use of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy for certain presentations of the disease.

For patients with allergy to house-dust mites, evidence is leaning toward a role for subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) in severe forms of atopic dermatitis (AD), and to sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for milder forms, researchers said.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunotherapy, Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said that poor trial evidence and a lack of standardization in outcome measures have hindered a better understanding of when SLIT and SCIT might be indicated in atopic dermatitis. Systematic reviews have failed to offer compelling evidence for its efficacy.

This is why current practice guidelines, published in 2012, say only that clinicians “might consider” allergen immunotherapy in selected patients with AD with aeroallergen sensitivity, and the research community has been striving to standardize outcome measures using two published eczema scoring systems, EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) and SCORAD (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis). Dr. Cox, part of the AAAAI/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology joint task force on allergen immunotherapies, said new clinical guidelines in progress would likely attempt to better define the role of SLIT and SCIT in atopic dermatitis.

Dr. Cox and another speaker at the conference, Dr. Moises Calderon, both pointed to house-dust mite allergy with AD as the most promising indication for immunotherapy in AD. A closer look at the few well-designed trials that have been conducted so far reveal the potential for a better-defined role for SLIT and SCIT, they agreed.

Dr. Calderon of Imperial College London identified four important trials dealing with this issue. The first was a German study of adults with AD aggravated by house-dust mites (n = 168) randomized to SCID or placebo and treated for 18 months. The study revealed no statistically significant differences for the treatment group as a whole, but a subgroup of patients with severe AD showed a statistically significant reduction of SCORAD disease scores by 18% (P = .02), compared with placebo (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:925-31).

An Italian trial enrolling house-dust mite–sensitive children with AD (n = 56, randomized 1:1 to treatment with SLIT or placebo) found a significant difference in SCORAD from baseline (P = .25) between the children treated with SLIT and the placebo group starting 9 months after treatment. However, the difference was seen in patients with mild or moderate disease only; minimal benefit was found for children with severe disease (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:164-70).

Dr. Calderon pointed to two additional studies published that also suggested benefit. The first was an open-label Colombian study enrolling children and young adults (n = 60). Of the 31 patients randomized to treatment with SCIT and topical therapies (controls received only topical treatment), the treatment group had significant SCORAD-measured improvement, compared with the control group (P = .03). At 1 year the active group also used topical steroids and tacrolimus significantly less (P = .02), and also had a significant increase in mite-specific IgG4 (doi:10.5402/2012/183983).

Dr. Calderon also mentioned a recent observational study from Poland that looked at long-term follow-up of a group of 15 AD patients treated with SCIT between 1995 and 2001 and followed for 12 years. The results suggested that SCIT may be associated with lasting improvements even after treatment termination (Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;47:5-9).

Both Dr. Cox and Dr. Calderon agreed that more and better evidence was needed to understand when and how SLIT and SCIT can work in atopic dermatitis. “AD is a heterogeneous disease, and immunotherapy cannot be a treatment for all types of atopic dermatitis – no one treatment is probably effective for all types of AD,” Dr. Cox cautioned. But “the direction of therapy is headed toward some acceptance.”

Dr, Calderon concurred. “We are on the way to acceptance. But new studies will be key,” he said.

Dr. Cox disclosed financial relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Calderon disclosed no conflicts of interest.

HOUSTON – Whether atopic dermatitis should be treated with allergen immunotherapy is still a matter of debate, as high-quality trial evidence remains scant, but clinical practice is starting to recognize the potential use of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy for certain presentations of the disease.

For patients with allergy to house-dust mites, evidence is leaning toward a role for subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) in severe forms of atopic dermatitis (AD), and to sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for milder forms, researchers said.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunotherapy, Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said that poor trial evidence and a lack of standardization in outcome measures have hindered a better understanding of when SLIT and SCIT might be indicated in atopic dermatitis. Systematic reviews have failed to offer compelling evidence for its efficacy.

This is why current practice guidelines, published in 2012, say only that clinicians “might consider” allergen immunotherapy in selected patients with AD with aeroallergen sensitivity, and the research community has been striving to standardize outcome measures using two published eczema scoring systems, EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) and SCORAD (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis). Dr. Cox, part of the AAAAI/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology joint task force on allergen immunotherapies, said new clinical guidelines in progress would likely attempt to better define the role of SLIT and SCIT in atopic dermatitis.

Dr. Cox and another speaker at the conference, Dr. Moises Calderon, both pointed to house-dust mite allergy with AD as the most promising indication for immunotherapy in AD. A closer look at the few well-designed trials that have been conducted so far reveal the potential for a better-defined role for SLIT and SCIT, they agreed.

Dr. Calderon of Imperial College London identified four important trials dealing with this issue. The first was a German study of adults with AD aggravated by house-dust mites (n = 168) randomized to SCID or placebo and treated for 18 months. The study revealed no statistically significant differences for the treatment group as a whole, but a subgroup of patients with severe AD showed a statistically significant reduction of SCORAD disease scores by 18% (P = .02), compared with placebo (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:925-31).

An Italian trial enrolling house-dust mite–sensitive children with AD (n = 56, randomized 1:1 to treatment with SLIT or placebo) found a significant difference in SCORAD from baseline (P = .25) between the children treated with SLIT and the placebo group starting 9 months after treatment. However, the difference was seen in patients with mild or moderate disease only; minimal benefit was found for children with severe disease (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:164-70).

Dr. Calderon pointed to two additional studies published that also suggested benefit. The first was an open-label Colombian study enrolling children and young adults (n = 60). Of the 31 patients randomized to treatment with SCIT and topical therapies (controls received only topical treatment), the treatment group had significant SCORAD-measured improvement, compared with the control group (P = .03). At 1 year the active group also used topical steroids and tacrolimus significantly less (P = .02), and also had a significant increase in mite-specific IgG4 (doi:10.5402/2012/183983).

Dr. Calderon also mentioned a recent observational study from Poland that looked at long-term follow-up of a group of 15 AD patients treated with SCIT between 1995 and 2001 and followed for 12 years. The results suggested that SCIT may be associated with lasting improvements even after treatment termination (Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;47:5-9).

Both Dr. Cox and Dr. Calderon agreed that more and better evidence was needed to understand when and how SLIT and SCIT can work in atopic dermatitis. “AD is a heterogeneous disease, and immunotherapy cannot be a treatment for all types of atopic dermatitis – no one treatment is probably effective for all types of AD,” Dr. Cox cautioned. But “the direction of therapy is headed toward some acceptance.”

Dr, Calderon concurred. “We are on the way to acceptance. But new studies will be key,” he said.

Dr. Cox disclosed financial relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Calderon disclosed no conflicts of interest.

HOUSTON – Whether atopic dermatitis should be treated with allergen immunotherapy is still a matter of debate, as high-quality trial evidence remains scant, but clinical practice is starting to recognize the potential use of subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy for certain presentations of the disease.

For patients with allergy to house-dust mites, evidence is leaning toward a role for subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) in severe forms of atopic dermatitis (AD), and to sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for milder forms, researchers said.

At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunotherapy, Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., said that poor trial evidence and a lack of standardization in outcome measures have hindered a better understanding of when SLIT and SCIT might be indicated in atopic dermatitis. Systematic reviews have failed to offer compelling evidence for its efficacy.

This is why current practice guidelines, published in 2012, say only that clinicians “might consider” allergen immunotherapy in selected patients with AD with aeroallergen sensitivity, and the research community has been striving to standardize outcome measures using two published eczema scoring systems, EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) and SCORAD (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis). Dr. Cox, part of the AAAAI/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology joint task force on allergen immunotherapies, said new clinical guidelines in progress would likely attempt to better define the role of SLIT and SCIT in atopic dermatitis.

Dr. Cox and another speaker at the conference, Dr. Moises Calderon, both pointed to house-dust mite allergy with AD as the most promising indication for immunotherapy in AD. A closer look at the few well-designed trials that have been conducted so far reveal the potential for a better-defined role for SLIT and SCIT, they agreed.

Dr. Calderon of Imperial College London identified four important trials dealing with this issue. The first was a German study of adults with AD aggravated by house-dust mites (n = 168) randomized to SCID or placebo and treated for 18 months. The study revealed no statistically significant differences for the treatment group as a whole, but a subgroup of patients with severe AD showed a statistically significant reduction of SCORAD disease scores by 18% (P = .02), compared with placebo (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:925-31).

An Italian trial enrolling house-dust mite–sensitive children with AD (n = 56, randomized 1:1 to treatment with SLIT or placebo) found a significant difference in SCORAD from baseline (P = .25) between the children treated with SLIT and the placebo group starting 9 months after treatment. However, the difference was seen in patients with mild or moderate disease only; minimal benefit was found for children with severe disease (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:164-70).

Dr. Calderon pointed to two additional studies published that also suggested benefit. The first was an open-label Colombian study enrolling children and young adults (n = 60). Of the 31 patients randomized to treatment with SCIT and topical therapies (controls received only topical treatment), the treatment group had significant SCORAD-measured improvement, compared with the control group (P = .03). At 1 year the active group also used topical steroids and tacrolimus significantly less (P = .02), and also had a significant increase in mite-specific IgG4 (doi:10.5402/2012/183983).

Dr. Calderon also mentioned a recent observational study from Poland that looked at long-term follow-up of a group of 15 AD patients treated with SCIT between 1995 and 2001 and followed for 12 years. The results suggested that SCIT may be associated with lasting improvements even after treatment termination (Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;47:5-9).

Both Dr. Cox and Dr. Calderon agreed that more and better evidence was needed to understand when and how SLIT and SCIT can work in atopic dermatitis. “AD is a heterogeneous disease, and immunotherapy cannot be a treatment for all types of atopic dermatitis – no one treatment is probably effective for all types of AD,” Dr. Cox cautioned. But “the direction of therapy is headed toward some acceptance.”

Dr, Calderon concurred. “We are on the way to acceptance. But new studies will be key,” he said.

Dr. Cox disclosed financial relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Calderon disclosed no conflicts of interest.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

SLIT: Guidelines in progress and practical concerns

HOUSTON – Sublingual immunotherapy, or SLIT, long used by clinicians worldwide, is newly approved for use in the United States, and practice guidelines have yet to be published for U.S. clinicians.

A joint task force of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) is drafting the guidelines. While clinicians wait, here is a look at the evidence for efficacy and safety of SLIT – particularly when compared with subcutaneous immunotherapy – as well as at the progress of the guidelines, offered by Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Dr. Cox spoke at the annual meeting of the AAAAI.

The guidelines will closely follow package labeling for the three sublingual pollen-allergy medications approved last year by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Cox said. These are the multipollen allergen tablet Oralair (Stallergenes), the Timothy grass pollen tablet Grastek (Merck), and the ragweed tablet Ragwitek (Merck). The medicines’ indications differ in terms of minimum age for prescription, ranging from 5 to 18 years, and the timing of treatment, with Grastek indicated as a year-round treatment, and the others as seasonal treatments.

FDA labeling on all three medications recommends coprescription of epinephrine pens in case of systemic reactions, and Dr. Cox said that the AAAAI/ACAAI guidelines would reflect this. Nonetheless, coprescription of epi pens “has never been the standard in Europe or other parts of the globe. We don’t have guidance from the broader community in terms of when to take the epinephrine in terms of a SLIT reaction,” she noted. Physicians should “be aware and think about what sort of instructions you’re going to give your patients” on the use of epi pens.

The guidelines in progress advise physicians to counsel patients that site application symptoms such as itching and swelling are very common during the first week of SLIT treatment, and that the majority of SLIT reactions are local (oral, pharyngeal, or abdominal). These local reactions usually disappear within days to weeks without treatment or dose modification, though some can be severe or bothersome enough to discontinue treatment. Systemic allergic reactions are very uncommon.

The guidelines are also likely to caution physicians that there are insufficient studies comparing SLIT and subcutaneous immunotherapy, or SCIT, to make a definitive statement about efficacy, Dr. Cox said. They will note that available studies suggest SCIT is more effective in the first year of treatment than SLIT, and comparative long-term efficacy studies have not been conducted, she added.

Finally, the guidelines are likely to caution that SLIT is contraindicated in patients who are not likely to survive a systemic adverse reaction or the resultant treatment.

Dr. Cox did not say when the guidelines were likely to be published, just that “we are frantically trying to get this document together,” noting the short time that SLIT has been commercially available in the United States.

At the same session on SLIT, Dr. Desiree Larenas Linneman, an allergist in private practice in Mexico City, spoke at the meeting about practical concerns related to SLIT and how to choose whether a patient is better suited to shots or sublingual therapy.

“When you bring sublingual to the public there are several issues you are going to have to be very careful with,” Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Among these are prescriptions of highly concentrated medications by nonallergists, adherence, and patient preference. “And we still do not have data for SLIT on a vast array of comorbidities,” she said.

“When we only had SCIT, these patients came into our offices and the only decision was, would we go for shots or not?” Now the choices are more complicated. A multiallergic 8-year-old, ordinarily a good candidate for SCIT, might be better treated with tablets if the parent is adamant that the child not get shots, she said. An adult who travels constantly for work might find tablets more convenient.

But for multiallergic and highly allergic patients, SCIT is generally the more flexible and reliable option, Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Allergists have access to a great variety of different allergens they can combine to make SCIT, while the approved tablets cover only pollen. And a tablet is a fixed dose, she said, “so there’s no adjustment for highly allergic patients.”

Dr. Larenas Linneman noted that adherence and patient preference are closely related, something that physicians must keep in mind when choosing the form of immunotherapy to offer. “Adherence is a very important issue because we know adherence is quite poor both with SLIT and SCIT,” she said.

“Physicians think that what’s most important for the patient is efficacy, cost, and side effects,” but patients’ ability to comply is also key, she said, and clinicians should let patient preference guide their decisions when possible.

Dr. Cox disclosed ongoing consulting relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Larenas Linnemann disclosed financial support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MEDA, Sanofi, and Senosiain.

HOUSTON – Sublingual immunotherapy, or SLIT, long used by clinicians worldwide, is newly approved for use in the United States, and practice guidelines have yet to be published for U.S. clinicians.

A joint task force of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) is drafting the guidelines. While clinicians wait, here is a look at the evidence for efficacy and safety of SLIT – particularly when compared with subcutaneous immunotherapy – as well as at the progress of the guidelines, offered by Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Dr. Cox spoke at the annual meeting of the AAAAI.

The guidelines will closely follow package labeling for the three sublingual pollen-allergy medications approved last year by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Cox said. These are the multipollen allergen tablet Oralair (Stallergenes), the Timothy grass pollen tablet Grastek (Merck), and the ragweed tablet Ragwitek (Merck). The medicines’ indications differ in terms of minimum age for prescription, ranging from 5 to 18 years, and the timing of treatment, with Grastek indicated as a year-round treatment, and the others as seasonal treatments.

FDA labeling on all three medications recommends coprescription of epinephrine pens in case of systemic reactions, and Dr. Cox said that the AAAAI/ACAAI guidelines would reflect this. Nonetheless, coprescription of epi pens “has never been the standard in Europe or other parts of the globe. We don’t have guidance from the broader community in terms of when to take the epinephrine in terms of a SLIT reaction,” she noted. Physicians should “be aware and think about what sort of instructions you’re going to give your patients” on the use of epi pens.

The guidelines in progress advise physicians to counsel patients that site application symptoms such as itching and swelling are very common during the first week of SLIT treatment, and that the majority of SLIT reactions are local (oral, pharyngeal, or abdominal). These local reactions usually disappear within days to weeks without treatment or dose modification, though some can be severe or bothersome enough to discontinue treatment. Systemic allergic reactions are very uncommon.

The guidelines are also likely to caution physicians that there are insufficient studies comparing SLIT and subcutaneous immunotherapy, or SCIT, to make a definitive statement about efficacy, Dr. Cox said. They will note that available studies suggest SCIT is more effective in the first year of treatment than SLIT, and comparative long-term efficacy studies have not been conducted, she added.

Finally, the guidelines are likely to caution that SLIT is contraindicated in patients who are not likely to survive a systemic adverse reaction or the resultant treatment.

Dr. Cox did not say when the guidelines were likely to be published, just that “we are frantically trying to get this document together,” noting the short time that SLIT has been commercially available in the United States.

At the same session on SLIT, Dr. Desiree Larenas Linneman, an allergist in private practice in Mexico City, spoke at the meeting about practical concerns related to SLIT and how to choose whether a patient is better suited to shots or sublingual therapy.

“When you bring sublingual to the public there are several issues you are going to have to be very careful with,” Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Among these are prescriptions of highly concentrated medications by nonallergists, adherence, and patient preference. “And we still do not have data for SLIT on a vast array of comorbidities,” she said.

“When we only had SCIT, these patients came into our offices and the only decision was, would we go for shots or not?” Now the choices are more complicated. A multiallergic 8-year-old, ordinarily a good candidate for SCIT, might be better treated with tablets if the parent is adamant that the child not get shots, she said. An adult who travels constantly for work might find tablets more convenient.

But for multiallergic and highly allergic patients, SCIT is generally the more flexible and reliable option, Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Allergists have access to a great variety of different allergens they can combine to make SCIT, while the approved tablets cover only pollen. And a tablet is a fixed dose, she said, “so there’s no adjustment for highly allergic patients.”

Dr. Larenas Linneman noted that adherence and patient preference are closely related, something that physicians must keep in mind when choosing the form of immunotherapy to offer. “Adherence is a very important issue because we know adherence is quite poor both with SLIT and SCIT,” she said.

“Physicians think that what’s most important for the patient is efficacy, cost, and side effects,” but patients’ ability to comply is also key, she said, and clinicians should let patient preference guide their decisions when possible.

Dr. Cox disclosed ongoing consulting relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Larenas Linnemann disclosed financial support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MEDA, Sanofi, and Senosiain.

HOUSTON – Sublingual immunotherapy, or SLIT, long used by clinicians worldwide, is newly approved for use in the United States, and practice guidelines have yet to be published for U.S. clinicians.

A joint task force of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) is drafting the guidelines. While clinicians wait, here is a look at the evidence for efficacy and safety of SLIT – particularly when compared with subcutaneous immunotherapy – as well as at the progress of the guidelines, offered by Dr. Linda Cox, an allergist in private practice in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Dr. Cox spoke at the annual meeting of the AAAAI.

The guidelines will closely follow package labeling for the three sublingual pollen-allergy medications approved last year by the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Cox said. These are the multipollen allergen tablet Oralair (Stallergenes), the Timothy grass pollen tablet Grastek (Merck), and the ragweed tablet Ragwitek (Merck). The medicines’ indications differ in terms of minimum age for prescription, ranging from 5 to 18 years, and the timing of treatment, with Grastek indicated as a year-round treatment, and the others as seasonal treatments.

FDA labeling on all three medications recommends coprescription of epinephrine pens in case of systemic reactions, and Dr. Cox said that the AAAAI/ACAAI guidelines would reflect this. Nonetheless, coprescription of epi pens “has never been the standard in Europe or other parts of the globe. We don’t have guidance from the broader community in terms of when to take the epinephrine in terms of a SLIT reaction,” she noted. Physicians should “be aware and think about what sort of instructions you’re going to give your patients” on the use of epi pens.

The guidelines in progress advise physicians to counsel patients that site application symptoms such as itching and swelling are very common during the first week of SLIT treatment, and that the majority of SLIT reactions are local (oral, pharyngeal, or abdominal). These local reactions usually disappear within days to weeks without treatment or dose modification, though some can be severe or bothersome enough to discontinue treatment. Systemic allergic reactions are very uncommon.

The guidelines are also likely to caution physicians that there are insufficient studies comparing SLIT and subcutaneous immunotherapy, or SCIT, to make a definitive statement about efficacy, Dr. Cox said. They will note that available studies suggest SCIT is more effective in the first year of treatment than SLIT, and comparative long-term efficacy studies have not been conducted, she added.

Finally, the guidelines are likely to caution that SLIT is contraindicated in patients who are not likely to survive a systemic adverse reaction or the resultant treatment.

Dr. Cox did not say when the guidelines were likely to be published, just that “we are frantically trying to get this document together,” noting the short time that SLIT has been commercially available in the United States.

At the same session on SLIT, Dr. Desiree Larenas Linneman, an allergist in private practice in Mexico City, spoke at the meeting about practical concerns related to SLIT and how to choose whether a patient is better suited to shots or sublingual therapy.

“When you bring sublingual to the public there are several issues you are going to have to be very careful with,” Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Among these are prescriptions of highly concentrated medications by nonallergists, adherence, and patient preference. “And we still do not have data for SLIT on a vast array of comorbidities,” she said.

“When we only had SCIT, these patients came into our offices and the only decision was, would we go for shots or not?” Now the choices are more complicated. A multiallergic 8-year-old, ordinarily a good candidate for SCIT, might be better treated with tablets if the parent is adamant that the child not get shots, she said. An adult who travels constantly for work might find tablets more convenient.

But for multiallergic and highly allergic patients, SCIT is generally the more flexible and reliable option, Dr. Larenas Linneman said. Allergists have access to a great variety of different allergens they can combine to make SCIT, while the approved tablets cover only pollen. And a tablet is a fixed dose, she said, “so there’s no adjustment for highly allergic patients.”

Dr. Larenas Linneman noted that adherence and patient preference are closely related, something that physicians must keep in mind when choosing the form of immunotherapy to offer. “Adherence is a very important issue because we know adherence is quite poor both with SLIT and SCIT,” she said.

“Physicians think that what’s most important for the patient is efficacy, cost, and side effects,” but patients’ ability to comply is also key, she said, and clinicians should let patient preference guide their decisions when possible.

Dr. Cox disclosed ongoing consulting relationships with Greer and Circassia. Dr. Larenas Linnemann disclosed financial support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MEDA, Sanofi, and Senosiain.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Beware common management pitfalls in severe refractory pediatric AD

HOUSTON – Dermatologists, allergists, and other physicians treating children with extremely refractory forms of atopic dermatitis (AD) must be aware of common treatment and management pitfalls before jumping to immunosuppressant or biologic therapies, says pediatric eczema researcher Dr. Donald Y. M. Leung, particularly as this is a patient group for whom no systemic therapies have been approved.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, Dr. Leung shared insights from his clinical experience at National Jewish Health in Denver, whose pediatric eczema program represents a national referral center for patients with severely refractory disease and their families.

“As managed care continues to march on, you will be faced with taking care of the more difficult patients,” Dr. Leung told clinicians.“You will see all forms of AD in clinical practice, therefore one size does not fit all, and a stepwise approach is needed to [treat] the different forms of eczema.”

Clinicians first need to determine what step, or grade, of eczema a patient has. For example, step 2 and 3 eczema is characterized by moderate disease not controlled by intermittent use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors.

National Jewish Health’s day-based program aims to first clear up children presenting with severe eczema before clinicians attempt diagnostic testing. This is achieved through the use of wet wraps, until skin has healed enough for testing to begin.

With wet wraps and day hospitalization, “you can go from severe to mild within a few days,” Dr. Leung said. For children who do not improve after the wet wraps, ruling out immune deficiency or other diagnoses is key. Dr. Leung and colleagues look for Dock 8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) protein deficiency in children who fail to respond to wet-wrap treatment, especially if they have presented with recurrent herpes infections or persistent warts.

Another important function of the day program is to observe how parents manage children with eczema. Many, Dr. Leung said, turn out to be noncompliant with recommendations on bathing and medications, often because of the discomfort it causes the child. The monitoring is essential to reveal errors in care. “You can’t tell this in a 10-minute office visit,” he said.

A top reason children fail therapy, he said, is because parents misinterpret recommendations on applying medicine after bathing. Many think that after applying a topical medication, “you can get better absorption if you put the moisturizer on top of the topical steroid. That really just dilutes the medication and you get ineffective therapy.”

Another upshot of the monitoring is that clinicians can identify parents suffering from depression, stress, or financial problems that prevent them from complying. “As with asthma, psychosocial factors loom big,” he said. Parents are extensively counseled and referred as needed, he said. Children also can be trained not to scratch their skin, and children over 5 years in the eczema program are offered hypnosis and biofeedback training to learn how to control their response to itching.

When taking a history of suspected food reactions, Dr. Leung said, it’s important to note that only hives and anaphylaxis are clearly linked to food allergy. “Skin testing and blood work is what we all do, but that’s helpful only if negative. If it’s positive, it still doesn’t tell you that they have food-induced eczema, and like it or not, some form of the food challenge is necessary.”

Dr. Leung said it is appropriate to conduct some oral food challenges unblinded after a negative test. “If a test is positive, and the parent insists that this food may cause eczema, it’s often necessary to do a double-blind, placebo-controlled test,” he said, which is the gold standard.

In discussing systemic therapies, Dr. Leung noted that general immunosuppressants were an approach favored by dermatologists, but urged caution with regard to interferons, mycophenolate, methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporin A. “These are expensive therapies not approved in children, and you really need very good documentation that they’ve failed other forms of therapy before you’d move to that,” Dr. Leung said.

Oral steroids should be avoided. “I have seen thousands of cases of severe eczema, and I’ve never put somebody on oral steroids unless they happened to have an asthma exacerbation concurrent with AD,” he said. “This is because they often have rebound within a week of stopping oral steroids, and that rebound can be worse than the disease you started with.”

If oral steroids must be used, “you should taper slowly and increase the intensity of skin care, so they don’t have a severe rebound.”

Dr. Leung said that while omalizumab should work in any disease with an elevated serum IgE level, “more often than not it doesn’t,” and it probably should be reserved for patients with a very clear history of allergen-induced eczema, underlying urticaria, or other forms of respiratory allergy that may be triggering asthma.

Two potential approaches in which allergists and dermatologists can work together, Dr. Leung said, are phototherapy and allergy immunotherapy. The latter is controversial in AD, he acknowledged, “but if somebody has mainly dust mite allergy or is monosensitized, it’s more likely you will get good benefit. If they’re polysensitized, it is unlikely because it’s mainly a barrier problem.”

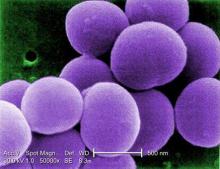

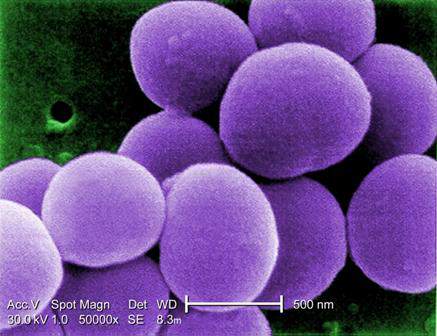

Dr. Leung did not recommend antibiotics except in the case of overt Staphylococcus aureus infection, so as not to select for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). “If you’re going to treat with some regimen, keep in mind that staph comes from the nose; that’s the body’s reservoir. You should always use an intranasal Bactroban [mupirocin] along with a systemic antibiotic.” Effective eradication of MRSA infection requires more drastic measures, including treatment of other family members and pets.

Dr. Leung disclosed doing consulting work for Celgene, Novartis, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Aventis, and a research grant from Horizon Pharma.

HOUSTON – Dermatologists, allergists, and other physicians treating children with extremely refractory forms of atopic dermatitis (AD) must be aware of common treatment and management pitfalls before jumping to immunosuppressant or biologic therapies, says pediatric eczema researcher Dr. Donald Y. M. Leung, particularly as this is a patient group for whom no systemic therapies have been approved.

In a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, Dr. Leung shared insights from his clinical experience at National Jewish Health in Denver, whose pediatric eczema program represents a national referral center for patients with severely refractory disease and their families.

“As managed care continues to march on, you will be faced with taking care of the more difficult patients,” Dr. Leung told clinicians.“You will see all forms of AD in clinical practice, therefore one size does not fit all, and a stepwise approach is needed to [treat] the different forms of eczema.”

Clinicians first need to determine what step, or grade, of eczema a patient has. For example, step 2 and 3 eczema is characterized by moderate disease not controlled by intermittent use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors.

National Jewish Health’s day-based program aims to first clear up children presenting with severe eczema before clinicians attempt diagnostic testing. This is achieved through the use of wet wraps, until skin has healed enough for testing to begin.

With wet wraps and day hospitalization, “you can go from severe to mild within a few days,” Dr. Leung said. For children who do not improve after the wet wraps, ruling out immune deficiency or other diagnoses is key. Dr. Leung and colleagues look for Dock 8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) protein deficiency in children who fail to respond to wet-wrap treatment, especially if they have presented with recurrent herpes infections or persistent warts.

Another important function of the day program is to observe how parents manage children with eczema. Many, Dr. Leung said, turn out to be noncompliant with recommendations on bathing and medications, often because of the discomfort it causes the child. The monitoring is essential to reveal errors in care. “You can’t tell this in a 10-minute office visit,” he said.

A top reason children fail therapy, he said, is because parents misinterpret recommendations on applying medicine after bathing. Many think that after applying a topical medication, “you can get better absorption if you put the moisturizer on top of the topical steroid. That really just dilutes the medication and you get ineffective therapy.”

Another upshot of the monitoring is that clinicians can identify parents suffering from depression, stress, or financial problems that prevent them from complying. “As with asthma, psychosocial factors loom big,” he said. Parents are extensively counseled and referred as needed, he said. Children also can be trained not to scratch their skin, and children over 5 years in the eczema program are offered hypnosis and biofeedback training to learn how to control their response to itching.

When taking a history of suspected food reactions, Dr. Leung said, it’s important to note that only hives and anaphylaxis are clearly linked to food allergy. “Skin testing and blood work is what we all do, but that’s helpful only if negative. If it’s positive, it still doesn’t tell you that they have food-induced eczema, and like it or not, some form of the food challenge is necessary.”

Dr. Leung said it is appropriate to conduct some oral food challenges unblinded after a negative test. “If a test is positive, and the parent insists that this food may cause eczema, it’s often necessary to do a double-blind, placebo-controlled test,” he said, which is the gold standard.

In discussing systemic therapies, Dr. Leung noted that general immunosuppressants were an approach favored by dermatologists, but urged caution with regard to interferons, mycophenolate, methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporin A. “These are expensive therapies not approved in children, and you really need very good documentation that they’ve failed other forms of therapy before you’d move to that,” Dr. Leung said.

Oral steroids should be avoided. “I have seen thousands of cases of severe eczema, and I’ve never put somebody on oral steroids unless they happened to have an asthma exacerbation concurrent with AD,” he said. “This is because they often have rebound within a week of stopping oral steroids, and that rebound can be worse than the disease you started with.”

If oral steroids must be used, “you should taper slowly and increase the intensity of skin care, so they don’t have a severe rebound.”

Dr. Leung said that while omalizumab should work in any disease with an elevated serum IgE level, “more often than not it doesn’t,” and it probably should be reserved for patients with a very clear history of allergen-induced eczema, underlying urticaria, or other forms of respiratory allergy that may be triggering asthma.

Two potential approaches in which allergists and dermatologists can work together, Dr. Leung said, are phototherapy and allergy immunotherapy. The latter is controversial in AD, he acknowledged, “but if somebody has mainly dust mite allergy or is monosensitized, it’s more likely you will get good benefit. If they’re polysensitized, it is unlikely because it’s mainly a barrier problem.”