User login

Analysis of Internal Dermatology Matches Following the COVID-19 Pandemic

Dermatology residencies continue to be among the most competitive, with only 66% of seniors in US medical schools (MD programs) successfully matching to a dermatology residency in 2023, according to the National Resident Matching Program. In 2023, there were 141 dermatology residency programs accepting applications, with a total of 499 positions offered. Of 578 medical school senior applicants, 384 of those applicants successfully matched. In contrast, of the 79 senior applicants from osteopathic medical schools, only 34 successfully matched, according to the National Resident Matching Program. A higher number of students match to either their home institution or an institution at which they completed an away (external) rotation, likely because faculty members are more comfortable matching future residents with whom they have worked because of greater familiarity with these applicants, and because applicants are more comfortable with programs familiar to them.1

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Association of Professors of Dermatology published an official statement discouraging programs from offering in-person external electives to applicants in the 2020-2021 cycle. As the pandemic progressed, this evolved: for the 2021-2022 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete only 1 away rotation, and for the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete up to 3 away rotations.2 This most recent recommendation reflects applicant experience before the pandemic, with some students having a personal connection to up to 4 programs, including their home and away programs.

A cross-sectional study published in early 2023 analyzed internal matches prior to and until the second year of the pandemic. The prepandemic rate of internal matches—applicants who matched at their home programs—was 26.7%. This rate increased to 40.3% in the 2020-2021 cycle and was 33.5% in the 2021-2022 cycle.2,3 The increase in internal matches is likely multifactorial, including the emergence of virtual interviews, the addition of program and geographic signals, and the regulation of away rotations. Notably, the rate of internal matches inversely correlates with the number of external programs to which students have connections.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to analyze the rates of internal and regional dermatology matches in the post–COVID-19 pandemic era (2022-2023) vs prepandemic and pandemic rates.

Methods

Data were obtained from publicly available online match lists from 65 US medical schools that detailed programs where dermatology applicants matched. The data reflected the postpandemic residency application cycle (2022-2023). These data were then compared to previous match rates for the prepandemic (2020-2021) and pandemic (2021-2022) application cycles. Medical schools without corresponding dermatology residency programs were excluded from the study. Regions were determined using the Association of American Medical Colleges Residency Explorer tool. The Northeast region included schools from Vermont; Pennsylvania; New Hampshire; New Jersey; Rhode Island; Maryland; Massachusetts; New York; Connecticut; and Washington, DC. The Southern region included schools from Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Arkansas, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, Oklahoma, and Virginia. The Western region included schools from Oregon, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, Washington, and California. The Central region included schools from Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska. The data collected included the number of applicants who matched into dermatology, the number of applicants who matched at their home institutions, and the regions in which applicants matched. Rates of matching were calculated as percentages, and Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare internal and regional match rates between different time periods.

Results

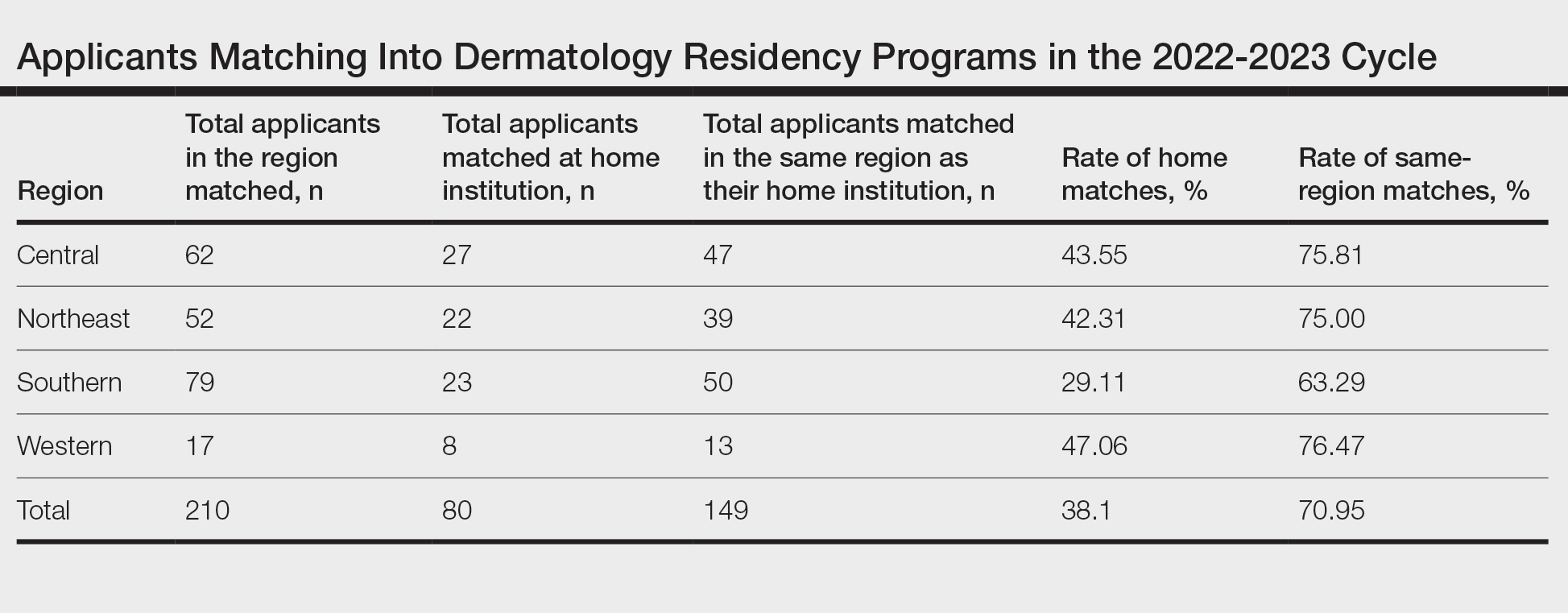

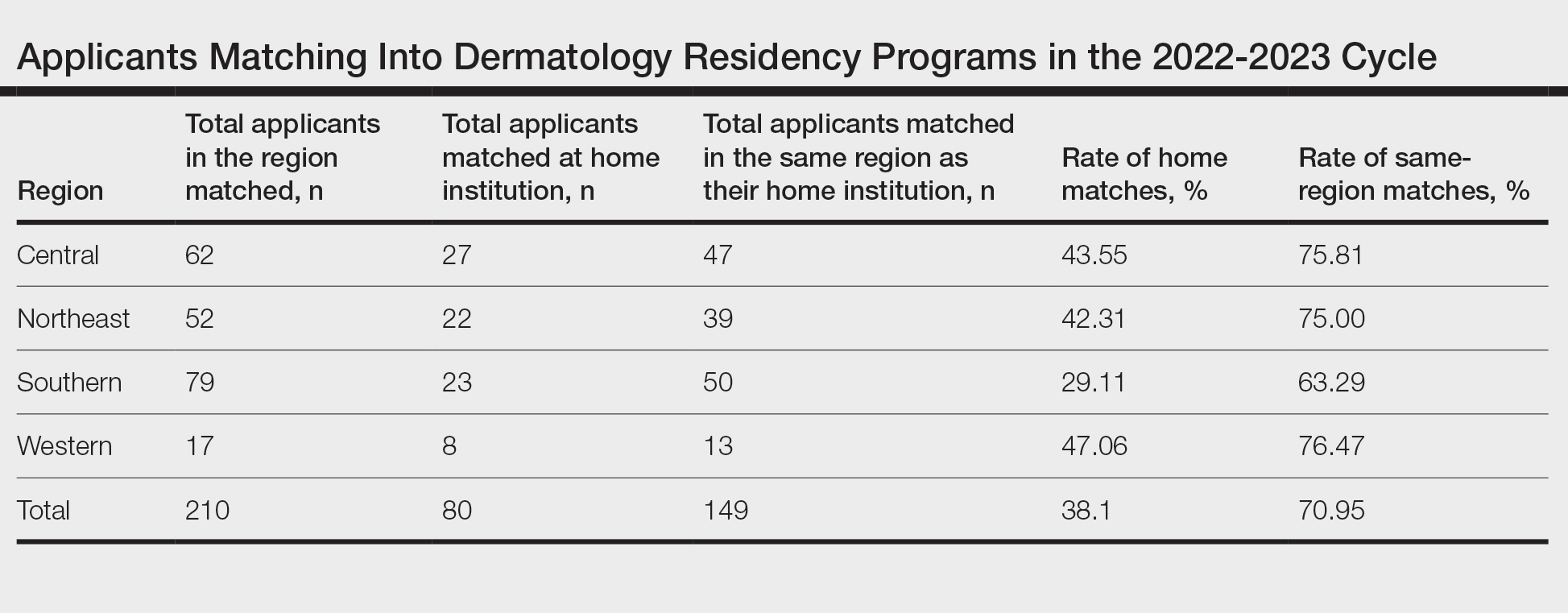

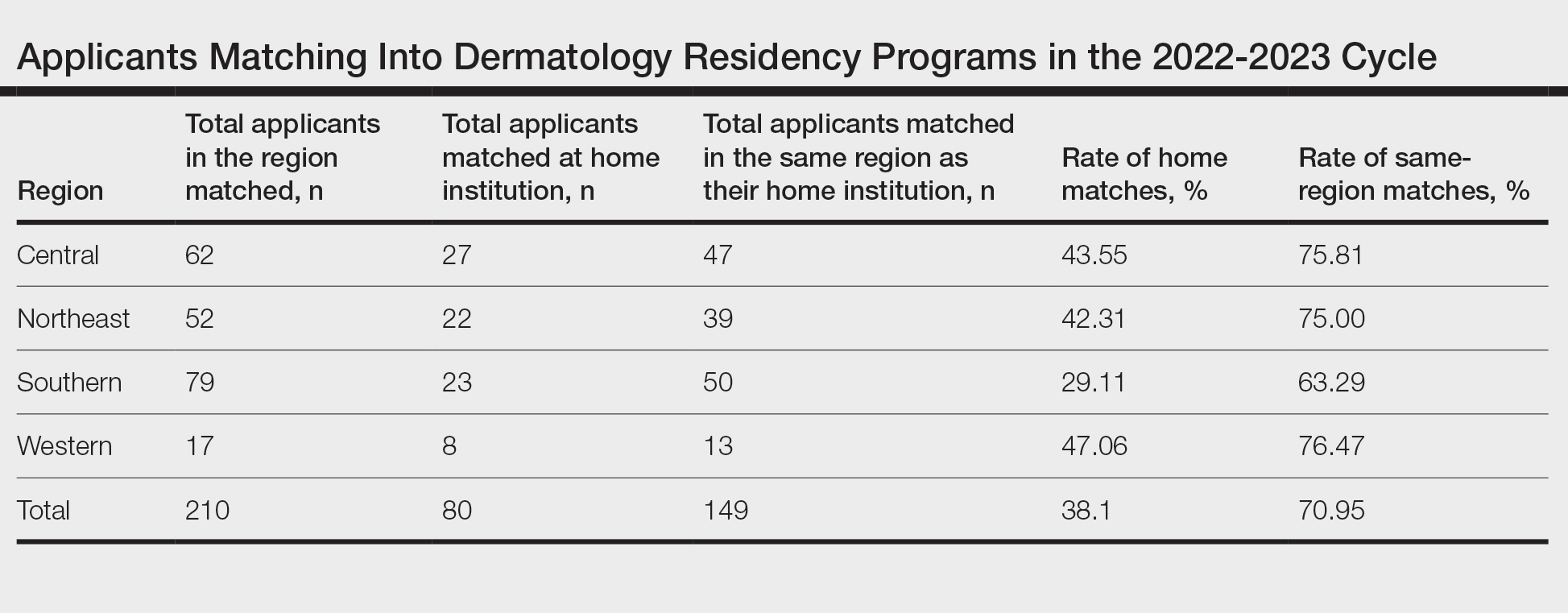

Results for the 2022-2023 residency cycle are summarized in the Table. Of 210 matches, 80 (38.10%) of the applicants matched at their home institution. In prepandemic cycles, 26.7% of applicants matched at their home institutions, which increased to 38.1% after the pandemic (P=.028). During the pandemic, 40.3% of applicants matched at their home institutions (P=.827).2 One hundred forty-nine of 210 (70.95%) applicants matched in the same region as their home institutions. The Western region had the highest rate of both internal matches (47.06%) and same-region matches (76.47%). However, the Central and Northeast regions were a close second (43.55% for home matches and 75.81% for same-region matches) and third (42.31% for home matches and 75.00% for same-region matches) for both rates, respectively. The Southern region had the lowest rates overall, with 29.11% for home matches and 63.29% for same-region matches.

Comment

The changes to the match process resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound impact on match outcomes since 2020. During the first year of the pandemic, internal matches increased to 40%; during the second year, the rate decreased to 33%.2 The difference between the current postpandemic internal match rate of 38.1% and the prepandemic internal match rate of 26.7% was statistically significant (P=.028). Conversely, the difference between the postpandemic internal match rate and the pandemic internal match rate was not significant (P=.827). These findings suggest that that pandemic trends have continued despite the return to multiple away rotations for students, perhaps suggesting that virtual interviews, which have been maintained at most programs despite the end of the pandemic, may be the driving force behind the increased home match rate. During the second year of the pandemic, there were greater odds (odds ratio, 2.3) of a dermatology program matching at least 1 internal applicant vs the years prior to 2020.4

The prepandemic regional match rate was 61.6% and increased to 67.5% during the pandemic.3 Following the pandemic, 70.95% of applicants matched in the same region as their home program. A study completed in 2022 using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency database found that there was no difference in the percentage of applicants who had a geographic connection to their program when comparing the 2021 cycle to 2018-2020 cycles.5 Frequently, applicants prefer to stay within their regions due to social factors. Although applicants can again travel for external rotations, the regional match rate has stayed relatively constant before and after the pandemic, though it has trended upward throughout the latest application cycles.

During the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were able to send preference signals to 3 programs. A survey reflecting the 2021-2022 cycle showed that 21.1% of applicants who sent a preference signal to a program were interviewed by that program, whereas only 3.7% of applicants who did not send a preference signal were interviewed. Furthermore, 19% of matched applicants sent a preference signal to the program at which they ultimately matched.6 Survey respondents included 40 accredited dermatology residency programs who reported an average of 506 applications per program. Preference signals were developed to allow applicants to connect with programs at which they were not able to rotate. It is unclear how preference signals are affecting internal or regional match rates, but similar to virtual interviewing, they may be contributing to the higher rates of internal matching.

This study is limited in the number of programs with match data publicly available for analysis. Additionally, there were no official data on how many students match at programs at which they completed external rotations. Furthermore, these data do not include reapplicants or osteopathic applicants who match within their regions. Importantly, all US medical schools were not represented in these data. Many programs, specifically in the Western region, did not have publicly available match lists. Self-reported match lists were not included in this study to avoid discrepancies. Regional rates reported here may not be representative of actual regional rates, as there were more applicants and internal matches in each region than were included in this study.

Conclusion

Although applicants were able to participate in external rotations as of the last 2 application cycles, there was still an increase in the rate of internal dermatology matches during the 2022-2023 cycle. This trend suggests an underlying disadvantage in matching for students without a home program. For the 2023-2024 cycle, applicants are recommended to complete up to 2 external rotations and may consider up to 3 if they do not have a home program. This recommended limitation in external rotations aims to allow students without a home program to develop connections with more programs.

- Luu Y, Gao W, Han J, et al. Personal connections and preference signaling: a cross-sectional analysis of the dermatology residency match during COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1381-1383. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.032

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Tarbox MB, et al. An analysis of internal and regional dermatology matches during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:207-209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.04.036

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Abdelwahab R, Antezana LA, Xie KZ, et al. Cross-sectional study of dermatology residency home match incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:886-888. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.004

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency Match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

Dermatology residencies continue to be among the most competitive, with only 66% of seniors in US medical schools (MD programs) successfully matching to a dermatology residency in 2023, according to the National Resident Matching Program. In 2023, there were 141 dermatology residency programs accepting applications, with a total of 499 positions offered. Of 578 medical school senior applicants, 384 of those applicants successfully matched. In contrast, of the 79 senior applicants from osteopathic medical schools, only 34 successfully matched, according to the National Resident Matching Program. A higher number of students match to either their home institution or an institution at which they completed an away (external) rotation, likely because faculty members are more comfortable matching future residents with whom they have worked because of greater familiarity with these applicants, and because applicants are more comfortable with programs familiar to them.1

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Association of Professors of Dermatology published an official statement discouraging programs from offering in-person external electives to applicants in the 2020-2021 cycle. As the pandemic progressed, this evolved: for the 2021-2022 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete only 1 away rotation, and for the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete up to 3 away rotations.2 This most recent recommendation reflects applicant experience before the pandemic, with some students having a personal connection to up to 4 programs, including their home and away programs.

A cross-sectional study published in early 2023 analyzed internal matches prior to and until the second year of the pandemic. The prepandemic rate of internal matches—applicants who matched at their home programs—was 26.7%. This rate increased to 40.3% in the 2020-2021 cycle and was 33.5% in the 2021-2022 cycle.2,3 The increase in internal matches is likely multifactorial, including the emergence of virtual interviews, the addition of program and geographic signals, and the regulation of away rotations. Notably, the rate of internal matches inversely correlates with the number of external programs to which students have connections.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to analyze the rates of internal and regional dermatology matches in the post–COVID-19 pandemic era (2022-2023) vs prepandemic and pandemic rates.

Methods

Data were obtained from publicly available online match lists from 65 US medical schools that detailed programs where dermatology applicants matched. The data reflected the postpandemic residency application cycle (2022-2023). These data were then compared to previous match rates for the prepandemic (2020-2021) and pandemic (2021-2022) application cycles. Medical schools without corresponding dermatology residency programs were excluded from the study. Regions were determined using the Association of American Medical Colleges Residency Explorer tool. The Northeast region included schools from Vermont; Pennsylvania; New Hampshire; New Jersey; Rhode Island; Maryland; Massachusetts; New York; Connecticut; and Washington, DC. The Southern region included schools from Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Arkansas, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, Oklahoma, and Virginia. The Western region included schools from Oregon, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, Washington, and California. The Central region included schools from Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska. The data collected included the number of applicants who matched into dermatology, the number of applicants who matched at their home institutions, and the regions in which applicants matched. Rates of matching were calculated as percentages, and Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare internal and regional match rates between different time periods.

Results

Results for the 2022-2023 residency cycle are summarized in the Table. Of 210 matches, 80 (38.10%) of the applicants matched at their home institution. In prepandemic cycles, 26.7% of applicants matched at their home institutions, which increased to 38.1% after the pandemic (P=.028). During the pandemic, 40.3% of applicants matched at their home institutions (P=.827).2 One hundred forty-nine of 210 (70.95%) applicants matched in the same region as their home institutions. The Western region had the highest rate of both internal matches (47.06%) and same-region matches (76.47%). However, the Central and Northeast regions were a close second (43.55% for home matches and 75.81% for same-region matches) and third (42.31% for home matches and 75.00% for same-region matches) for both rates, respectively. The Southern region had the lowest rates overall, with 29.11% for home matches and 63.29% for same-region matches.

Comment

The changes to the match process resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound impact on match outcomes since 2020. During the first year of the pandemic, internal matches increased to 40%; during the second year, the rate decreased to 33%.2 The difference between the current postpandemic internal match rate of 38.1% and the prepandemic internal match rate of 26.7% was statistically significant (P=.028). Conversely, the difference between the postpandemic internal match rate and the pandemic internal match rate was not significant (P=.827). These findings suggest that that pandemic trends have continued despite the return to multiple away rotations for students, perhaps suggesting that virtual interviews, which have been maintained at most programs despite the end of the pandemic, may be the driving force behind the increased home match rate. During the second year of the pandemic, there were greater odds (odds ratio, 2.3) of a dermatology program matching at least 1 internal applicant vs the years prior to 2020.4

The prepandemic regional match rate was 61.6% and increased to 67.5% during the pandemic.3 Following the pandemic, 70.95% of applicants matched in the same region as their home program. A study completed in 2022 using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency database found that there was no difference in the percentage of applicants who had a geographic connection to their program when comparing the 2021 cycle to 2018-2020 cycles.5 Frequently, applicants prefer to stay within their regions due to social factors. Although applicants can again travel for external rotations, the regional match rate has stayed relatively constant before and after the pandemic, though it has trended upward throughout the latest application cycles.

During the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were able to send preference signals to 3 programs. A survey reflecting the 2021-2022 cycle showed that 21.1% of applicants who sent a preference signal to a program were interviewed by that program, whereas only 3.7% of applicants who did not send a preference signal were interviewed. Furthermore, 19% of matched applicants sent a preference signal to the program at which they ultimately matched.6 Survey respondents included 40 accredited dermatology residency programs who reported an average of 506 applications per program. Preference signals were developed to allow applicants to connect with programs at which they were not able to rotate. It is unclear how preference signals are affecting internal or regional match rates, but similar to virtual interviewing, they may be contributing to the higher rates of internal matching.

This study is limited in the number of programs with match data publicly available for analysis. Additionally, there were no official data on how many students match at programs at which they completed external rotations. Furthermore, these data do not include reapplicants or osteopathic applicants who match within their regions. Importantly, all US medical schools were not represented in these data. Many programs, specifically in the Western region, did not have publicly available match lists. Self-reported match lists were not included in this study to avoid discrepancies. Regional rates reported here may not be representative of actual regional rates, as there were more applicants and internal matches in each region than were included in this study.

Conclusion

Although applicants were able to participate in external rotations as of the last 2 application cycles, there was still an increase in the rate of internal dermatology matches during the 2022-2023 cycle. This trend suggests an underlying disadvantage in matching for students without a home program. For the 2023-2024 cycle, applicants are recommended to complete up to 2 external rotations and may consider up to 3 if they do not have a home program. This recommended limitation in external rotations aims to allow students without a home program to develop connections with more programs.

Dermatology residencies continue to be among the most competitive, with only 66% of seniors in US medical schools (MD programs) successfully matching to a dermatology residency in 2023, according to the National Resident Matching Program. In 2023, there were 141 dermatology residency programs accepting applications, with a total of 499 positions offered. Of 578 medical school senior applicants, 384 of those applicants successfully matched. In contrast, of the 79 senior applicants from osteopathic medical schools, only 34 successfully matched, according to the National Resident Matching Program. A higher number of students match to either their home institution or an institution at which they completed an away (external) rotation, likely because faculty members are more comfortable matching future residents with whom they have worked because of greater familiarity with these applicants, and because applicants are more comfortable with programs familiar to them.1

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Association of Professors of Dermatology published an official statement discouraging programs from offering in-person external electives to applicants in the 2020-2021 cycle. As the pandemic progressed, this evolved: for the 2021-2022 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete only 1 away rotation, and for the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were encouraged to complete up to 3 away rotations.2 This most recent recommendation reflects applicant experience before the pandemic, with some students having a personal connection to up to 4 programs, including their home and away programs.

A cross-sectional study published in early 2023 analyzed internal matches prior to and until the second year of the pandemic. The prepandemic rate of internal matches—applicants who matched at their home programs—was 26.7%. This rate increased to 40.3% in the 2020-2021 cycle and was 33.5% in the 2021-2022 cycle.2,3 The increase in internal matches is likely multifactorial, including the emergence of virtual interviews, the addition of program and geographic signals, and the regulation of away rotations. Notably, the rate of internal matches inversely correlates with the number of external programs to which students have connections.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to analyze the rates of internal and regional dermatology matches in the post–COVID-19 pandemic era (2022-2023) vs prepandemic and pandemic rates.

Methods

Data were obtained from publicly available online match lists from 65 US medical schools that detailed programs where dermatology applicants matched. The data reflected the postpandemic residency application cycle (2022-2023). These data were then compared to previous match rates for the prepandemic (2020-2021) and pandemic (2021-2022) application cycles. Medical schools without corresponding dermatology residency programs were excluded from the study. Regions were determined using the Association of American Medical Colleges Residency Explorer tool. The Northeast region included schools from Vermont; Pennsylvania; New Hampshire; New Jersey; Rhode Island; Maryland; Massachusetts; New York; Connecticut; and Washington, DC. The Southern region included schools from Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Arkansas, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, Oklahoma, and Virginia. The Western region included schools from Oregon, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, Washington, and California. The Central region included schools from Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska. The data collected included the number of applicants who matched into dermatology, the number of applicants who matched at their home institutions, and the regions in which applicants matched. Rates of matching were calculated as percentages, and Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare internal and regional match rates between different time periods.

Results

Results for the 2022-2023 residency cycle are summarized in the Table. Of 210 matches, 80 (38.10%) of the applicants matched at their home institution. In prepandemic cycles, 26.7% of applicants matched at their home institutions, which increased to 38.1% after the pandemic (P=.028). During the pandemic, 40.3% of applicants matched at their home institutions (P=.827).2 One hundred forty-nine of 210 (70.95%) applicants matched in the same region as their home institutions. The Western region had the highest rate of both internal matches (47.06%) and same-region matches (76.47%). However, the Central and Northeast regions were a close second (43.55% for home matches and 75.81% for same-region matches) and third (42.31% for home matches and 75.00% for same-region matches) for both rates, respectively. The Southern region had the lowest rates overall, with 29.11% for home matches and 63.29% for same-region matches.

Comment

The changes to the match process resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have had a profound impact on match outcomes since 2020. During the first year of the pandemic, internal matches increased to 40%; during the second year, the rate decreased to 33%.2 The difference between the current postpandemic internal match rate of 38.1% and the prepandemic internal match rate of 26.7% was statistically significant (P=.028). Conversely, the difference between the postpandemic internal match rate and the pandemic internal match rate was not significant (P=.827). These findings suggest that that pandemic trends have continued despite the return to multiple away rotations for students, perhaps suggesting that virtual interviews, which have been maintained at most programs despite the end of the pandemic, may be the driving force behind the increased home match rate. During the second year of the pandemic, there were greater odds (odds ratio, 2.3) of a dermatology program matching at least 1 internal applicant vs the years prior to 2020.4

The prepandemic regional match rate was 61.6% and increased to 67.5% during the pandemic.3 Following the pandemic, 70.95% of applicants matched in the same region as their home program. A study completed in 2022 using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency database found that there was no difference in the percentage of applicants who had a geographic connection to their program when comparing the 2021 cycle to 2018-2020 cycles.5 Frequently, applicants prefer to stay within their regions due to social factors. Although applicants can again travel for external rotations, the regional match rate has stayed relatively constant before and after the pandemic, though it has trended upward throughout the latest application cycles.

During the 2022-2023 cycle, applicants were able to send preference signals to 3 programs. A survey reflecting the 2021-2022 cycle showed that 21.1% of applicants who sent a preference signal to a program were interviewed by that program, whereas only 3.7% of applicants who did not send a preference signal were interviewed. Furthermore, 19% of matched applicants sent a preference signal to the program at which they ultimately matched.6 Survey respondents included 40 accredited dermatology residency programs who reported an average of 506 applications per program. Preference signals were developed to allow applicants to connect with programs at which they were not able to rotate. It is unclear how preference signals are affecting internal or regional match rates, but similar to virtual interviewing, they may be contributing to the higher rates of internal matching.

This study is limited in the number of programs with match data publicly available for analysis. Additionally, there were no official data on how many students match at programs at which they completed external rotations. Furthermore, these data do not include reapplicants or osteopathic applicants who match within their regions. Importantly, all US medical schools were not represented in these data. Many programs, specifically in the Western region, did not have publicly available match lists. Self-reported match lists were not included in this study to avoid discrepancies. Regional rates reported here may not be representative of actual regional rates, as there were more applicants and internal matches in each region than were included in this study.

Conclusion

Although applicants were able to participate in external rotations as of the last 2 application cycles, there was still an increase in the rate of internal dermatology matches during the 2022-2023 cycle. This trend suggests an underlying disadvantage in matching for students without a home program. For the 2023-2024 cycle, applicants are recommended to complete up to 2 external rotations and may consider up to 3 if they do not have a home program. This recommended limitation in external rotations aims to allow students without a home program to develop connections with more programs.

- Luu Y, Gao W, Han J, et al. Personal connections and preference signaling: a cross-sectional analysis of the dermatology residency match during COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1381-1383. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.032

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Tarbox MB, et al. An analysis of internal and regional dermatology matches during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:207-209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.04.036

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Abdelwahab R, Antezana LA, Xie KZ, et al. Cross-sectional study of dermatology residency home match incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:886-888. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.004

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency Match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

- Luu Y, Gao W, Han J, et al. Personal connections and preference signaling: a cross-sectional analysis of the dermatology residency match during COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1381-1383. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.01.032

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Tarbox MB, et al. An analysis of internal and regional dermatology matches during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:207-209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.04.036

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Abdelwahab R, Antezana LA, Xie KZ, et al. Cross-sectional study of dermatology residency home match incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:886-888. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.004

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency Match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Dirr MA, Brownstone N, Zakria D, et al. Dermatology match preference signaling tokens: impact and implications. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1367-1368. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003645

PRACTICE POINTS

- Following the COVID-19 pandemic, affiliation with a home program is even more impactful in successful application to dermatology residency. Applicants from institutions without dermatology programs should consider completing additional externships.

- The high rate of applicants matching to the same regions as their home programs is due to several factors. Applicants may have a larger social support system near their home institution. Additionally, programs are more comfortable matching applicants within their own regions.

Results From the First Annual Association of Professors of Dermatology Program Directors Survey

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

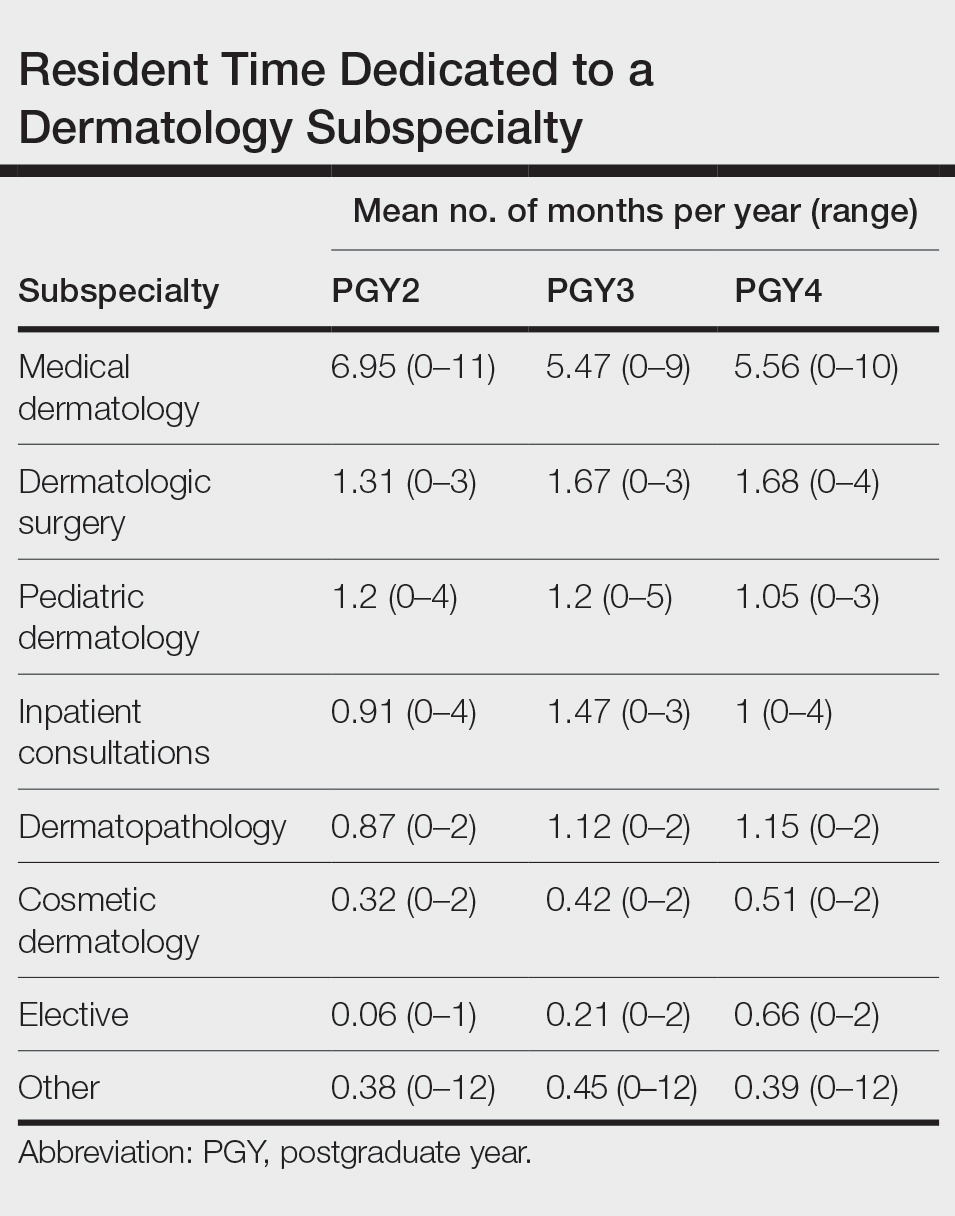

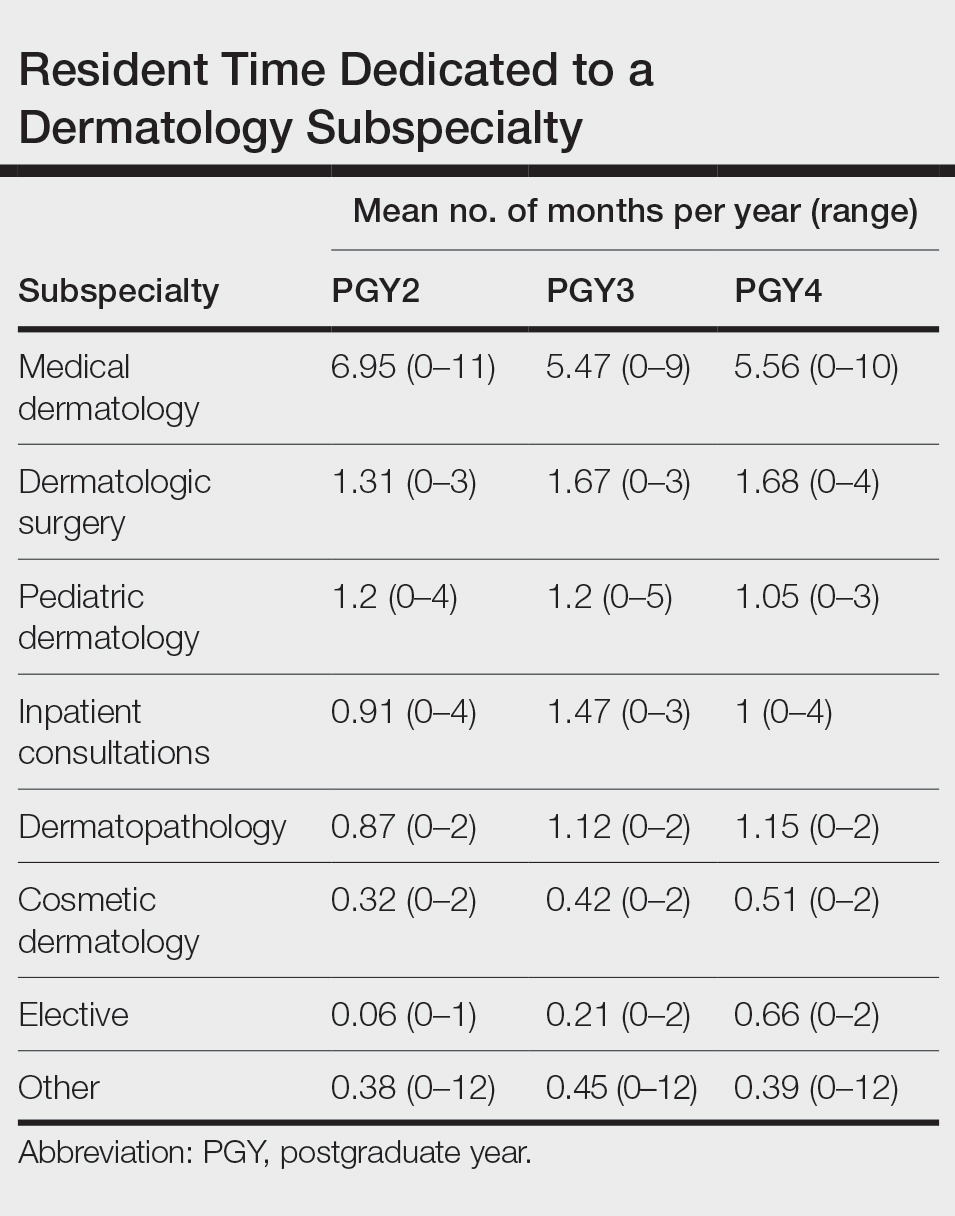

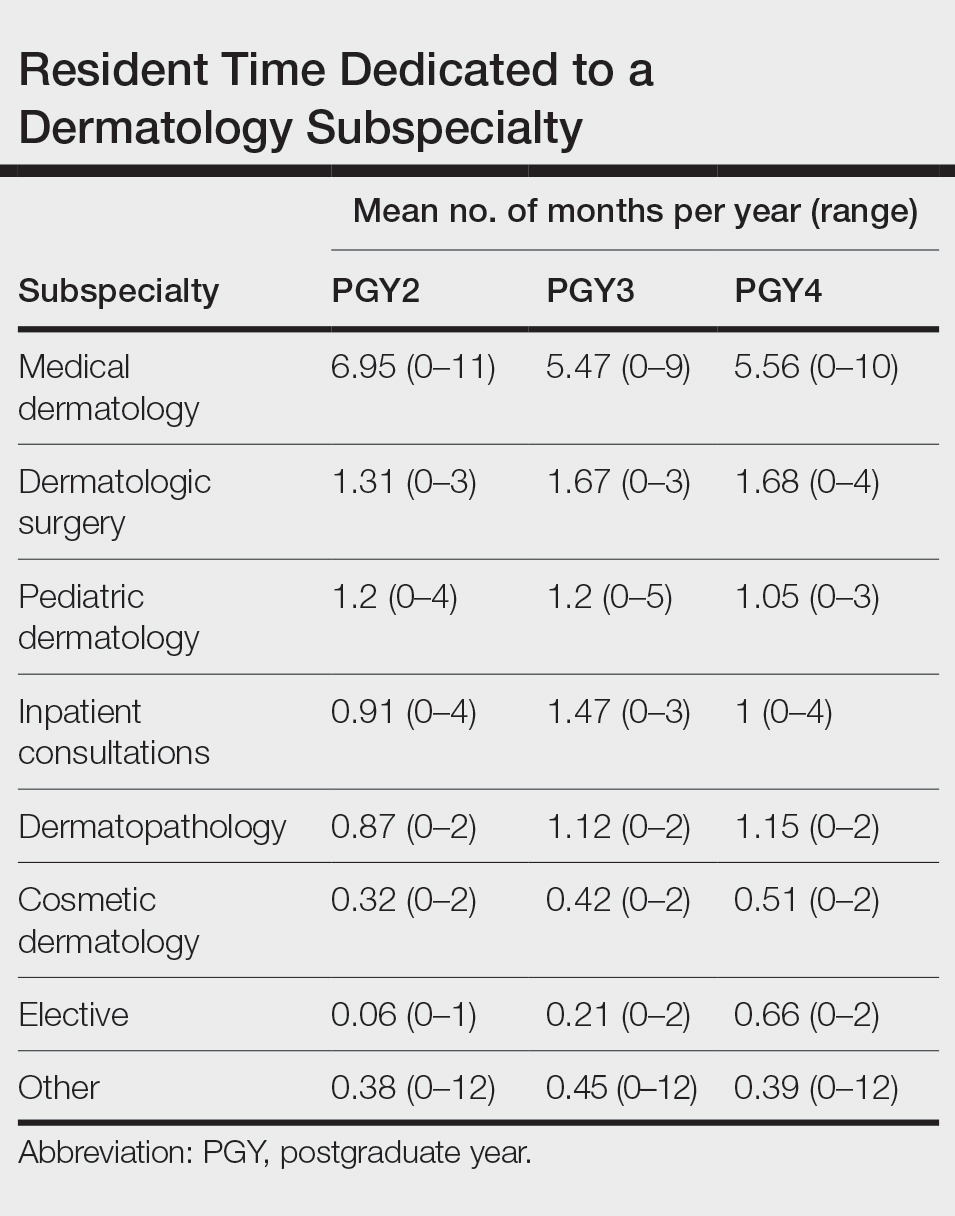

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

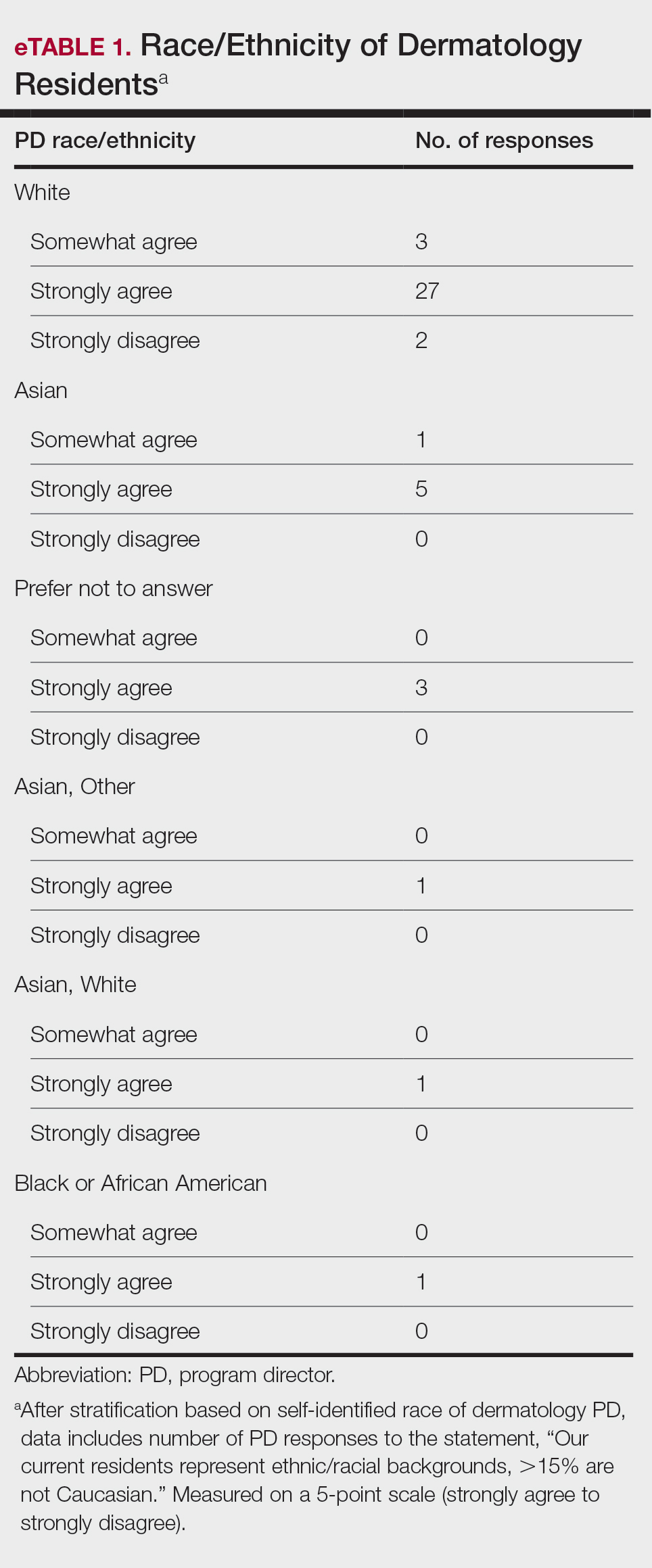

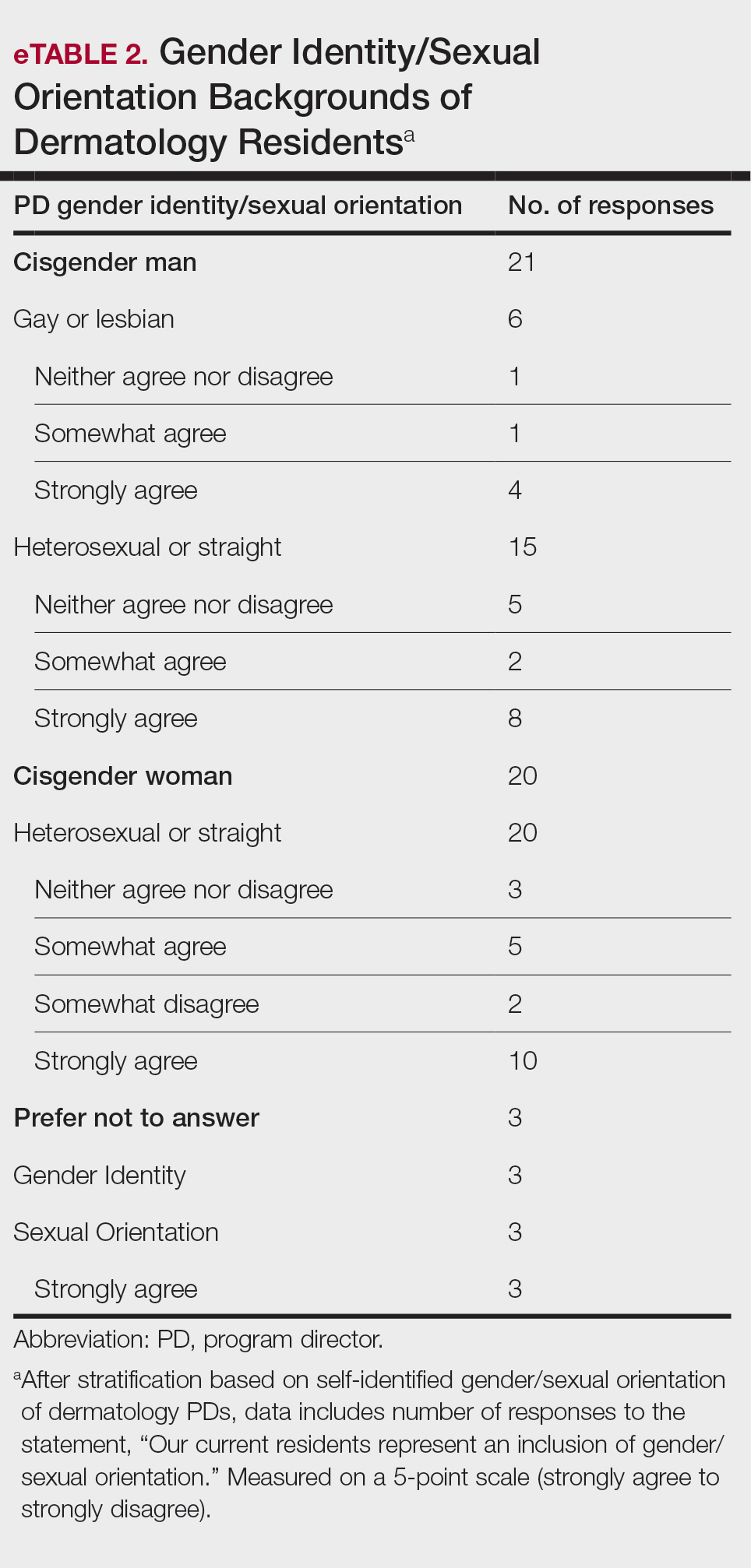

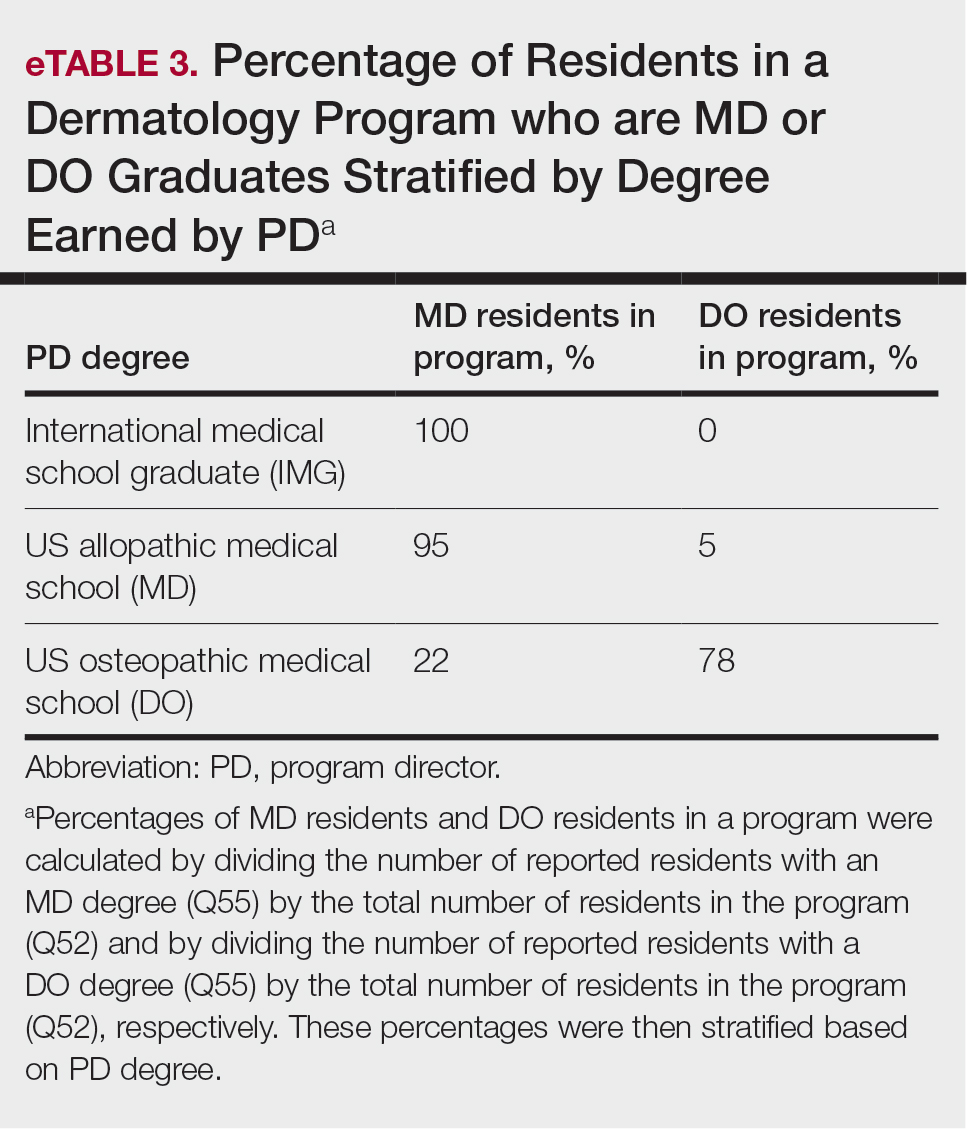

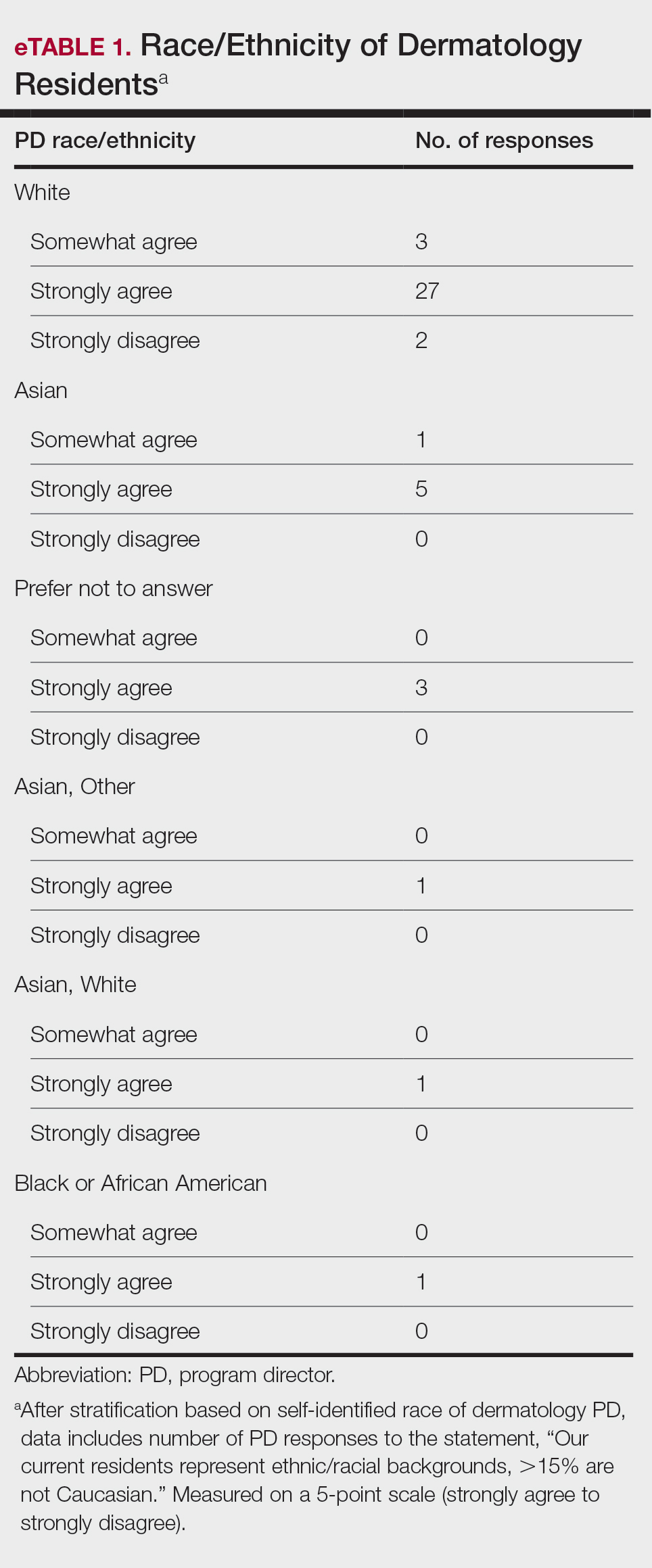

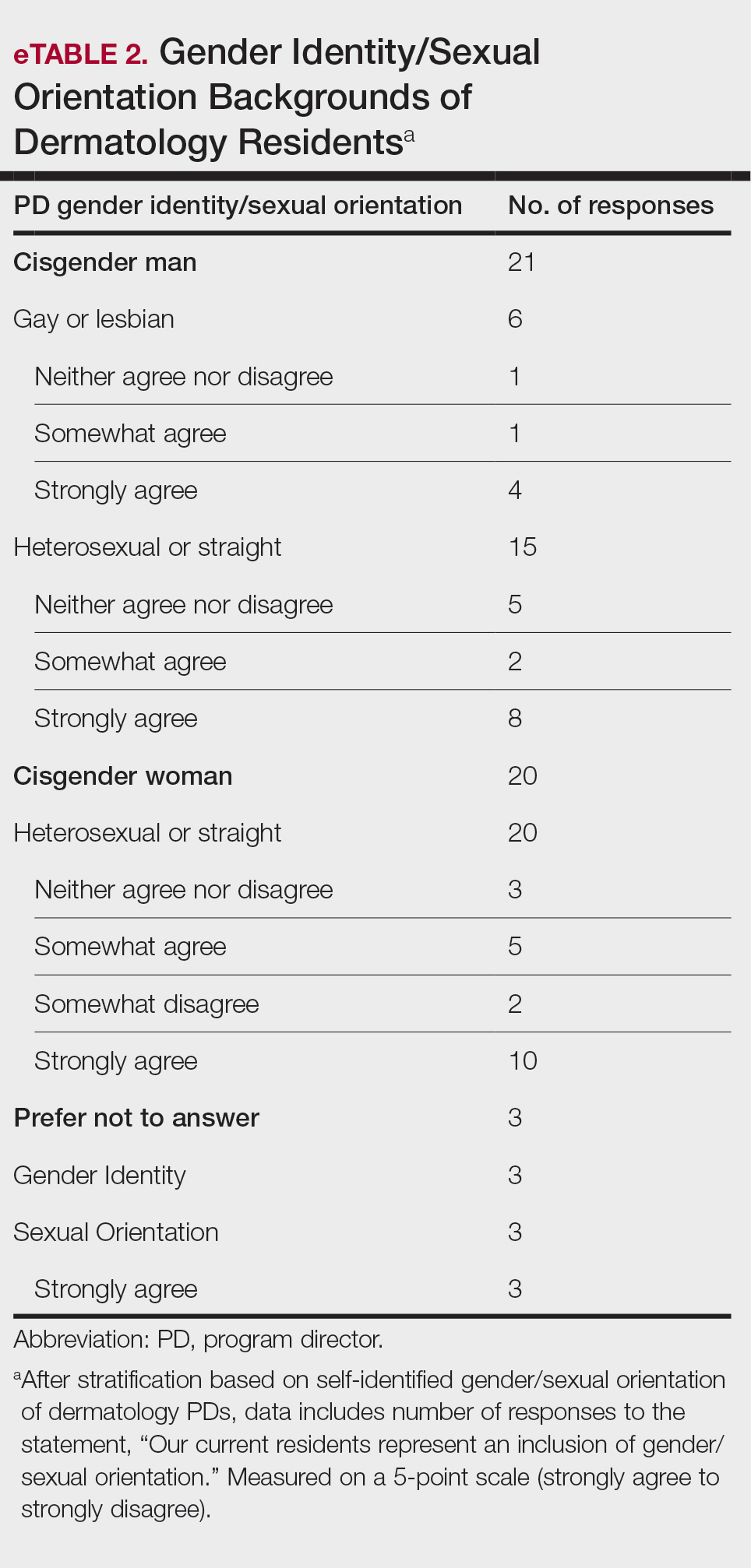

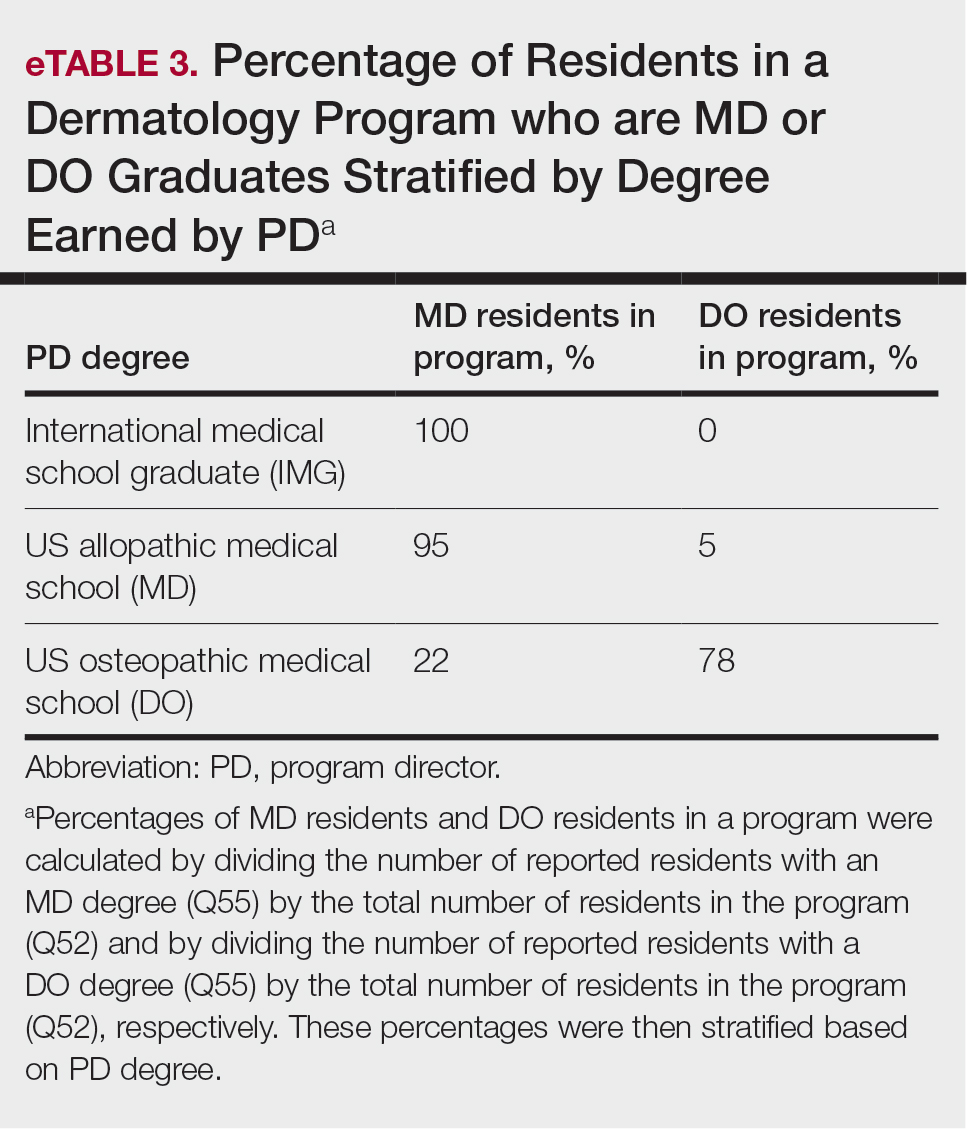

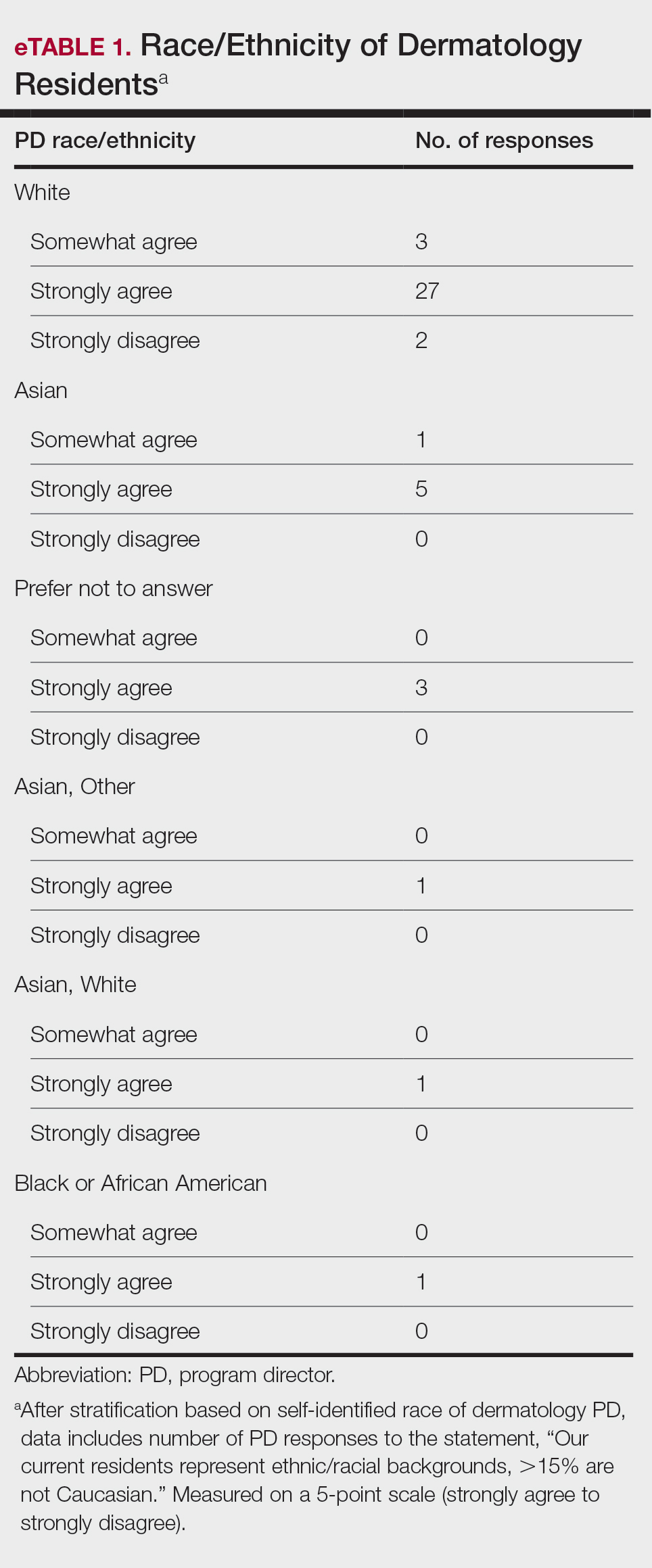

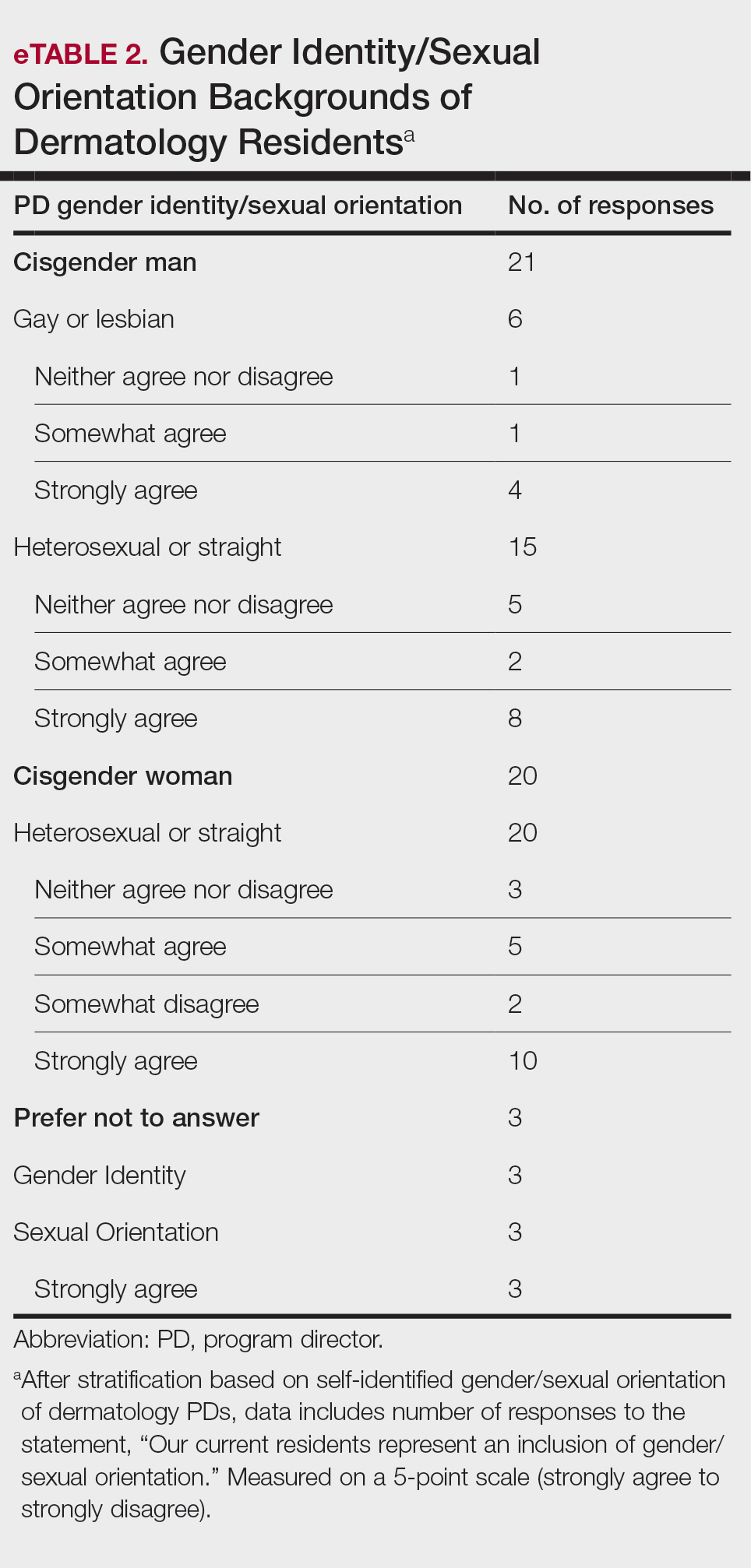

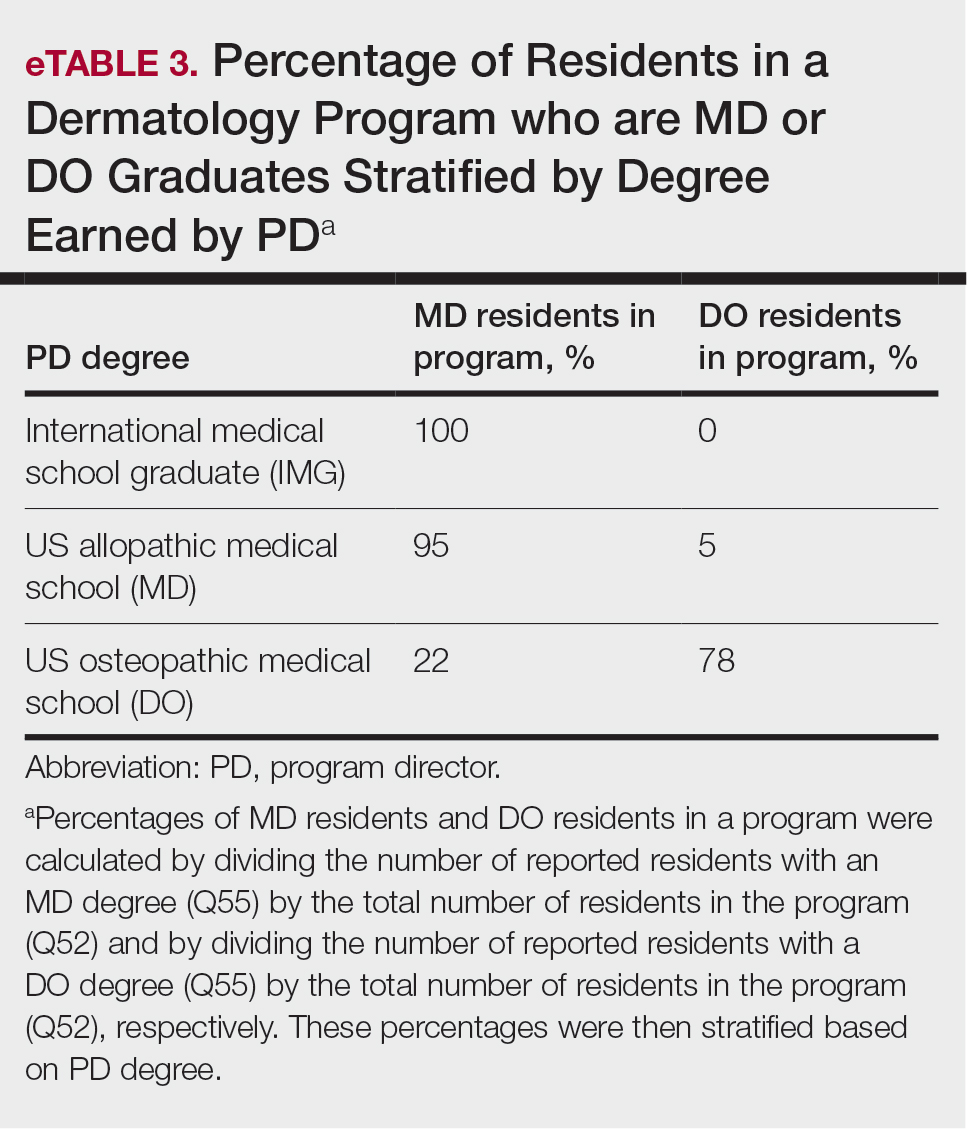

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178