User login

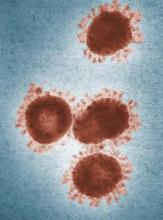

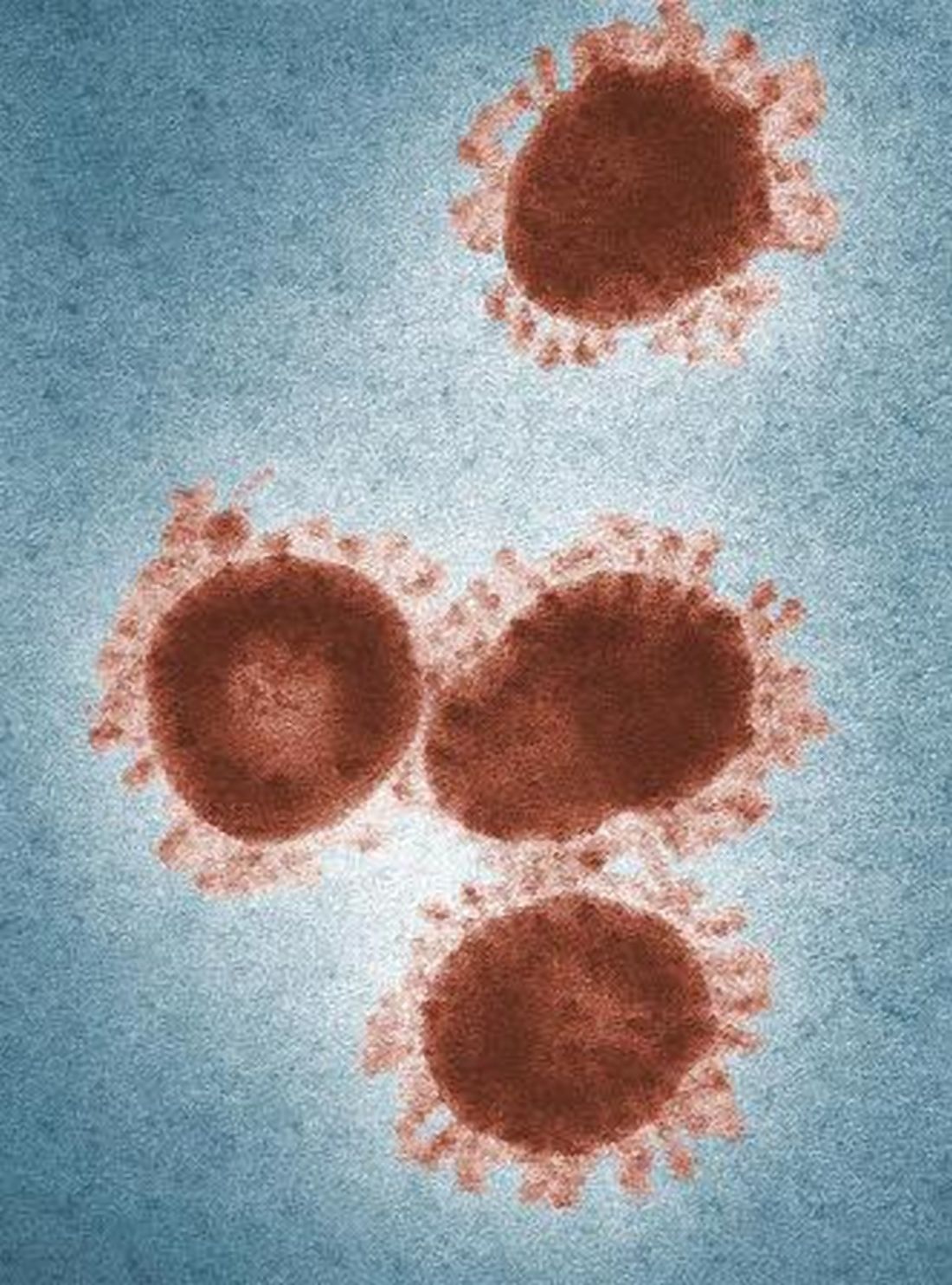

2019-nCoV outbreak: A few lessons learned for pediatric practices

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

ID Consult: It’s not necessarily over when measles infection clears

As I write, I imagine readers groaning at yet another measles story. But in early November 2019, in Portland, Oregon, Judy Guzman-Cottrill, DO, recently was groaning at yet another measles case.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, recently shared details provided by the local health department:

An unimmunized child developed measles while traveling outside the county. The child may have exposed others at Portland International Airport, a medical center in Vancouver, and potentially at another children’s hospital in the area.

As of Nov. 7, 2019, 1,261 cases of measles from 31 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – more cases in a single year since 1992. The case in Portland added at least one to that total, although public officials warned that additional cases could occur Nov. 18th through Dec. 9 (given the incubation period). Like the child in Oregon, most of the individuals who developed measles nationwide in 2019 were unimmunized. At press time, from Jan. 1 to Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles have been confirmed in 31 states; CDC released measles reports monthly.

The reasons for refusal of measles vaccine vary, but historically, some parents have made a calculated risk. Measles is rare. Most children are vaccinated. My child will be protected by herd immunity. In some communities, that is no longer true, as we have seen in 2019.

Other parents have decided – erroneously – that measles infection is less risky than measles vaccine. We need to be able to tell them the facts. Thirty percent of individuals who contract measles will develop at least one complication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in four will be hospitalized. While death from acute measles infection is uncommon, children remain at risk for sequelae months or years after the initial infection.

For example, measles is known to suppress the immune system, an effect that lasts for months or years after the initial infection. Practically, this means that once a child recovers from acute measles infection, he or she has an increased susceptibility to other infections that may last for years. Two studies published late in 2019 described the immune “amnesia” that occurs following measles infection. Essentially, the immune system forgets how to fight other pathogens, leaving children vulnerable to potentially life-threatening infections.

Michael Mina, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues measured the effects of measles infection on the immune system by studying blood samples taken from 77 unimmunized children in the Netherlands before and after measles infection.1 Two months after recovery from mild measles, children had lost a median of 33 % (range, 12%-73%) of preexisting antibodies against a range of common viruses and bacteria. The median loss was 40% after severe measles (range 11% to 62%). Similar changes were not observed after measles vaccine.

A second group of researchers led by Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. They found that measles infection reduced the diversity of immune cells available to recognize and fight infections and depleted memory B cells, essentially returning the immune to a more immature state.2

Parents also need to know that children who develop measles are at risk for noninfectious complications.

Yes, SSPE is a rare, but it is not as rare as we once thought. In 2017, investigators in California described 17 cases of SSPE identified in that state between 1998 and 2005.3 The incidence of SSPE was 1 in 1,367 for children less than 5 years at the time of measles infection and 1 in 609 for children less than 12 months when they contracted the virus.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill has seen a case of SSPE, and she hopes to never see another one. “He had been a healthy 11-year-old boy,” she recalled. “He played soccer and basketball and did well in school.” In the beginning, his symptoms were insidious and nonspecific, Dr. Guzman-Cottrill and colleagues wrote in a 2016 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.4 He started to struggle in school. He dozed off in the middle of meals. He started to drop things. Over a 4-month period, the boy developed progressive spasticity, became unable to eat or drink, and could no longer recognize or communicate with his family. “That’s when I met him,” Dr. Guzman-Cottrill said. “It was heartbreaking, and there was very little we could do for him except give the family a diagnosis. He eventually died in hospice care, nearly 4 years after his symptoms began.”

The boy had been infected with measles at 1 year of age while living in the Philippines. Dr. Guzman-Cottrill emphasized that this family had not refused measles immunization. The child had received a measles vaccine at 8 months of age, but a single vaccine at such a young age wasn’t enough to protect him.

We can hope for change in 2020, including improved immunization rates and a decline in measles cases. If that happens, measles will no longer be a hot topic in the news. We’ll likely never know what happens to the children infected in 2019, those who are facing the current cold and flu season with impaired immune systems. A decade or more will pass before we’ll know if anyone develops SSPE. For now, all we can do is wait … and worry.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky., and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606.

2. Science Immunology. 2019 Nov 1;4:eaay6125.

As I write, I imagine readers groaning at yet another measles story. But in early November 2019, in Portland, Oregon, Judy Guzman-Cottrill, DO, recently was groaning at yet another measles case.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, recently shared details provided by the local health department:

An unimmunized child developed measles while traveling outside the county. The child may have exposed others at Portland International Airport, a medical center in Vancouver, and potentially at another children’s hospital in the area.

As of Nov. 7, 2019, 1,261 cases of measles from 31 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – more cases in a single year since 1992. The case in Portland added at least one to that total, although public officials warned that additional cases could occur Nov. 18th through Dec. 9 (given the incubation period). Like the child in Oregon, most of the individuals who developed measles nationwide in 2019 were unimmunized. At press time, from Jan. 1 to Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles have been confirmed in 31 states; CDC released measles reports monthly.

The reasons for refusal of measles vaccine vary, but historically, some parents have made a calculated risk. Measles is rare. Most children are vaccinated. My child will be protected by herd immunity. In some communities, that is no longer true, as we have seen in 2019.

Other parents have decided – erroneously – that measles infection is less risky than measles vaccine. We need to be able to tell them the facts. Thirty percent of individuals who contract measles will develop at least one complication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in four will be hospitalized. While death from acute measles infection is uncommon, children remain at risk for sequelae months or years after the initial infection.

For example, measles is known to suppress the immune system, an effect that lasts for months or years after the initial infection. Practically, this means that once a child recovers from acute measles infection, he or she has an increased susceptibility to other infections that may last for years. Two studies published late in 2019 described the immune “amnesia” that occurs following measles infection. Essentially, the immune system forgets how to fight other pathogens, leaving children vulnerable to potentially life-threatening infections.

Michael Mina, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues measured the effects of measles infection on the immune system by studying blood samples taken from 77 unimmunized children in the Netherlands before and after measles infection.1 Two months after recovery from mild measles, children had lost a median of 33 % (range, 12%-73%) of preexisting antibodies against a range of common viruses and bacteria. The median loss was 40% after severe measles (range 11% to 62%). Similar changes were not observed after measles vaccine.

A second group of researchers led by Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. They found that measles infection reduced the diversity of immune cells available to recognize and fight infections and depleted memory B cells, essentially returning the immune to a more immature state.2

Parents also need to know that children who develop measles are at risk for noninfectious complications.

Yes, SSPE is a rare, but it is not as rare as we once thought. In 2017, investigators in California described 17 cases of SSPE identified in that state between 1998 and 2005.3 The incidence of SSPE was 1 in 1,367 for children less than 5 years at the time of measles infection and 1 in 609 for children less than 12 months when they contracted the virus.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill has seen a case of SSPE, and she hopes to never see another one. “He had been a healthy 11-year-old boy,” she recalled. “He played soccer and basketball and did well in school.” In the beginning, his symptoms were insidious and nonspecific, Dr. Guzman-Cottrill and colleagues wrote in a 2016 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.4 He started to struggle in school. He dozed off in the middle of meals. He started to drop things. Over a 4-month period, the boy developed progressive spasticity, became unable to eat or drink, and could no longer recognize or communicate with his family. “That’s when I met him,” Dr. Guzman-Cottrill said. “It was heartbreaking, and there was very little we could do for him except give the family a diagnosis. He eventually died in hospice care, nearly 4 years after his symptoms began.”

The boy had been infected with measles at 1 year of age while living in the Philippines. Dr. Guzman-Cottrill emphasized that this family had not refused measles immunization. The child had received a measles vaccine at 8 months of age, but a single vaccine at such a young age wasn’t enough to protect him.

We can hope for change in 2020, including improved immunization rates and a decline in measles cases. If that happens, measles will no longer be a hot topic in the news. We’ll likely never know what happens to the children infected in 2019, those who are facing the current cold and flu season with impaired immune systems. A decade or more will pass before we’ll know if anyone develops SSPE. For now, all we can do is wait … and worry.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky., and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606.

2. Science Immunology. 2019 Nov 1;4:eaay6125.

As I write, I imagine readers groaning at yet another measles story. But in early November 2019, in Portland, Oregon, Judy Guzman-Cottrill, DO, recently was groaning at yet another measles case.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, recently shared details provided by the local health department:

An unimmunized child developed measles while traveling outside the county. The child may have exposed others at Portland International Airport, a medical center in Vancouver, and potentially at another children’s hospital in the area.

As of Nov. 7, 2019, 1,261 cases of measles from 31 states had been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – more cases in a single year since 1992. The case in Portland added at least one to that total, although public officials warned that additional cases could occur Nov. 18th through Dec. 9 (given the incubation period). Like the child in Oregon, most of the individuals who developed measles nationwide in 2019 were unimmunized. At press time, from Jan. 1 to Dec. 5, 2019, 1,276 individual cases of measles have been confirmed in 31 states; CDC released measles reports monthly.

The reasons for refusal of measles vaccine vary, but historically, some parents have made a calculated risk. Measles is rare. Most children are vaccinated. My child will be protected by herd immunity. In some communities, that is no longer true, as we have seen in 2019.

Other parents have decided – erroneously – that measles infection is less risky than measles vaccine. We need to be able to tell them the facts. Thirty percent of individuals who contract measles will develop at least one complication, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in four will be hospitalized. While death from acute measles infection is uncommon, children remain at risk for sequelae months or years after the initial infection.

For example, measles is known to suppress the immune system, an effect that lasts for months or years after the initial infection. Practically, this means that once a child recovers from acute measles infection, he or she has an increased susceptibility to other infections that may last for years. Two studies published late in 2019 described the immune “amnesia” that occurs following measles infection. Essentially, the immune system forgets how to fight other pathogens, leaving children vulnerable to potentially life-threatening infections.

Michael Mina, MD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and colleagues measured the effects of measles infection on the immune system by studying blood samples taken from 77 unimmunized children in the Netherlands before and after measles infection.1 Two months after recovery from mild measles, children had lost a median of 33 % (range, 12%-73%) of preexisting antibodies against a range of common viruses and bacteria. The median loss was 40% after severe measles (range 11% to 62%). Similar changes were not observed after measles vaccine.

A second group of researchers led by Velislava N. Petrova, PhD, of the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England, investigated genetic changes in 26 unvaccinated children from the Netherlands who previously had measles. They found that measles infection reduced the diversity of immune cells available to recognize and fight infections and depleted memory B cells, essentially returning the immune to a more immature state.2

Parents also need to know that children who develop measles are at risk for noninfectious complications.

Yes, SSPE is a rare, but it is not as rare as we once thought. In 2017, investigators in California described 17 cases of SSPE identified in that state between 1998 and 2005.3 The incidence of SSPE was 1 in 1,367 for children less than 5 years at the time of measles infection and 1 in 609 for children less than 12 months when they contracted the virus.

Dr. Guzman-Cottrill has seen a case of SSPE, and she hopes to never see another one. “He had been a healthy 11-year-old boy,” she recalled. “He played soccer and basketball and did well in school.” In the beginning, his symptoms were insidious and nonspecific, Dr. Guzman-Cottrill and colleagues wrote in a 2016 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.4 He started to struggle in school. He dozed off in the middle of meals. He started to drop things. Over a 4-month period, the boy developed progressive spasticity, became unable to eat or drink, and could no longer recognize or communicate with his family. “That’s when I met him,” Dr. Guzman-Cottrill said. “It was heartbreaking, and there was very little we could do for him except give the family a diagnosis. He eventually died in hospice care, nearly 4 years after his symptoms began.”

The boy had been infected with measles at 1 year of age while living in the Philippines. Dr. Guzman-Cottrill emphasized that this family had not refused measles immunization. The child had received a measles vaccine at 8 months of age, but a single vaccine at such a young age wasn’t enough to protect him.

We can hope for change in 2020, including improved immunization rates and a decline in measles cases. If that happens, measles will no longer be a hot topic in the news. We’ll likely never know what happens to the children infected in 2019, those who are facing the current cold and flu season with impaired immune systems. A decade or more will pass before we’ll know if anyone develops SSPE. For now, all we can do is wait … and worry.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville, Ky., and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. Dr. Bryant had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366:599-606.

2. Science Immunology. 2019 Nov 1;4:eaay6125.

Is your office ready for a case of measles?

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

What infectious disease should parents be most worried about?

I think the question was intended as polite, dinner party chit chat ... maybe an attempt by a gracious hostess to make sure everyone was engaged in conversation.

“So what pediatric infectious disease should parents be most worried about?” she asked me.

I’ll admit that a couple of perfectly respectable and noncontroversial possibilities crossed my mind before I answered.

Acute flaccid myelitis? Measles?

When I replied, “gonorrhea,” conversation at the table pretty much stopped.

Let me explain. Acute flaccid myelitis is a polio-like neurologic condition that has been grabbing headlines. Yes, it is concerning that most cases have occurred in children and some affected children are left with long-term deficits. Technically though, AFM is a neurologic rather than an infectious disease. When cases occur, we suspect a viral infection but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no pathogen has been consistently identified from the spinal fluid of infected patients. From August 2014 to September 2018, the CDC received information on 368 confirmed cases, so AFM fortunately is still rare.

News reports describe measles outbreaks raging in Europe – more than 41,000 cases so far this year, and 40 deaths – and warn that the United States could be next. But let’s be honest: We have a safe and effective vaccine for measles and outbreaks like this don’t happen when individuals are appropriately immunized. Parents, immunize your children. If you are lucky enough to be traveling to Europe with your baby, remember that MMR vaccine is indicated for 6- to 11-month olds, but it doesn’t count in the 2-dose series.

But gonorrhea?

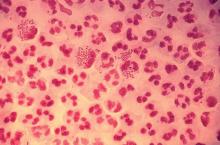

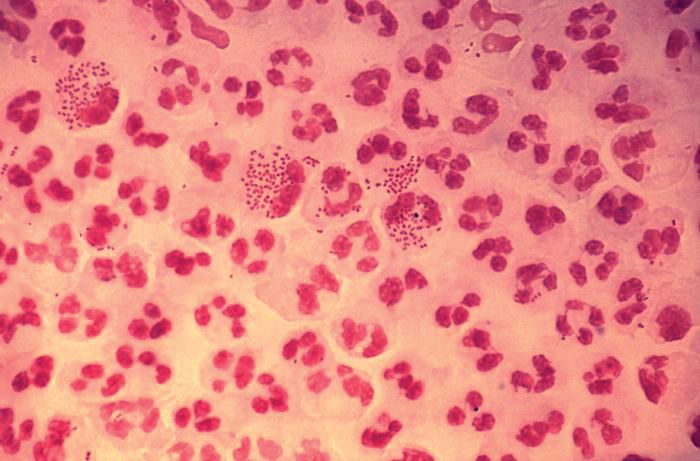

In 2017, the World Health Organization included Neisseria gonorrhoeae on its list of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health and for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. The popular media are calling N. gonorrhoeae one of the new “superbugs.” Globally, patients are being diagnosed with strains of gonorrhea that are resistant to all commonly used antibiotics. As reported during IDWeek 2018 this October, patients also are being diagnosed in the United States.

Sancta St. Cyr, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues reported data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) and trends in multidrug resistant (MDR) and extensively-drug resistant (XDR) gonorrhea in the United States. A gonococcal isolate with resistance or elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) to greater than or equal to two classes of antimicrobials is classified as MDR and an isolate with elevated MICs to greater than or equal to three classes of antimicrobials is classified as XDR. The MIC is the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibits growth of bacteria in the laboratory and rising MICs – evidence that higher levels of an antibiotic are needed to stop bacterial growth – can be an early indicator that resistance is emerging.

More than 150,000 gonococcal isolates were tested between 1987 and 2016. The first isolates with elevated MICs to cephalosporins and macrolides were identified in 1998, and since 2011, MDR resistance rates have hovered around 1%. In 2016, the rate was 1.1%, down from 1.3% in 2011. A single XDR isolate with resistance to fluoroquinolones with elevated MICs to both cephalosporins and macrolides was identified in 2011.

One could look at these data and ask if this is a “glass half full or half empty” situation, but I propose that clinicians and public health officials should not look at these data and be reassured that rates of MDR-gonorrhea remained stable between 2010 and 2016. According to a recent surveillance report released by the CDC, the absolute number of cases of gonorrhea has continued to rise. In 2017, there were 555,608 cases reported in the United States, a 67% increase since 2013. If we assume that rates of resistance in 2017 were similar to those in 2016, that’s more than 5,000 cases of MDR-gonorrhea in a single year.

“That’s bad,” one of my dining companions agreed. “But is gonorrhea really a pediatric issue?”

To answer that question, we just have to look at the numbers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, the percentage of high school students who had ever had sex was approximately 40% and about 10% of students had four or more lifetime partners. More than 45% of sexually active students denied the use of a condom during the last sexual intercourse. Certainly, that puts many teenagers at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that public health authorities report that half of all new STIs occur in individuals aged 15-24 years. Moreover, 25% of sexually active adolescent girls contract at least one STI.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United States, and according to the CDC, rates of disease in 2017 were highest among adolescents and young adults. In females specifically, the highest rates of gonorrhea were observed among those aged 20-24 years (684.8 cases per 100,000 females) and 15-19 years (557.4 cases per 100,000 females).

It makes sense that pediatricians and parents advocate for making the reduction of gonorrhea transmission rates a public health priority. We also need to recognize that prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. Since 2015, dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only CDC-recommended treatment for gonorrhea.

At that dinner party, my closest friend, who also happens to be a pediatrician, rolled her eyes and shot me look that I’m sure meant, “Nobody really wants to talk about gonorrhea over dessert.” Still, because she is a good friend she said, “So basically you’re saying that and if this keeps up, we may see kids with untreatable infection. Now that is scary.”

I kept quiet after that but I wanted to mention that in 2017, less than 85% of patients diagnosed with gonorrhea at selected surveillance sites received the recommended treatment with two antibiotics. Patients with inadequately treated gonorrhea are at risk for a host of sequelae. Women can develop pelvic inflammatory disease, abscesses, chronic pelvic pain, and damage of the fallopian tubes that can lead to infertility. Men can develop epididymitis, which occasionally results in infertility. Rarely, N. gonorrhoeae can spread to the blood and cause life-threatening infection. Of course, patients who aren’t treated appropriately may continue to spread the bacteria. Scary? You bet.

For pediatricians who need a refresher course in the treatment of STIs, there are free resources available. The CDC’s 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines are available in a free app; the app contains a nice refresher on taking a sexual history. There also is a print version, wall chart, and pocket guide. Providers also may want to check out the National STD Curriculum offered by the University of Washington STD Prevention Training Center and the University of Washington. Visit https://www.std.uw.edu/.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

I think the question was intended as polite, dinner party chit chat ... maybe an attempt by a gracious hostess to make sure everyone was engaged in conversation.

“So what pediatric infectious disease should parents be most worried about?” she asked me.

I’ll admit that a couple of perfectly respectable and noncontroversial possibilities crossed my mind before I answered.

Acute flaccid myelitis? Measles?

When I replied, “gonorrhea,” conversation at the table pretty much stopped.

Let me explain. Acute flaccid myelitis is a polio-like neurologic condition that has been grabbing headlines. Yes, it is concerning that most cases have occurred in children and some affected children are left with long-term deficits. Technically though, AFM is a neurologic rather than an infectious disease. When cases occur, we suspect a viral infection but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no pathogen has been consistently identified from the spinal fluid of infected patients. From August 2014 to September 2018, the CDC received information on 368 confirmed cases, so AFM fortunately is still rare.

News reports describe measles outbreaks raging in Europe – more than 41,000 cases so far this year, and 40 deaths – and warn that the United States could be next. But let’s be honest: We have a safe and effective vaccine for measles and outbreaks like this don’t happen when individuals are appropriately immunized. Parents, immunize your children. If you are lucky enough to be traveling to Europe with your baby, remember that MMR vaccine is indicated for 6- to 11-month olds, but it doesn’t count in the 2-dose series.

But gonorrhea?

In 2017, the World Health Organization included Neisseria gonorrhoeae on its list of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health and for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. The popular media are calling N. gonorrhoeae one of the new “superbugs.” Globally, patients are being diagnosed with strains of gonorrhea that are resistant to all commonly used antibiotics. As reported during IDWeek 2018 this October, patients also are being diagnosed in the United States.

Sancta St. Cyr, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues reported data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) and trends in multidrug resistant (MDR) and extensively-drug resistant (XDR) gonorrhea in the United States. A gonococcal isolate with resistance or elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) to greater than or equal to two classes of antimicrobials is classified as MDR and an isolate with elevated MICs to greater than or equal to three classes of antimicrobials is classified as XDR. The MIC is the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibits growth of bacteria in the laboratory and rising MICs – evidence that higher levels of an antibiotic are needed to stop bacterial growth – can be an early indicator that resistance is emerging.

More than 150,000 gonococcal isolates were tested between 1987 and 2016. The first isolates with elevated MICs to cephalosporins and macrolides were identified in 1998, and since 2011, MDR resistance rates have hovered around 1%. In 2016, the rate was 1.1%, down from 1.3% in 2011. A single XDR isolate with resistance to fluoroquinolones with elevated MICs to both cephalosporins and macrolides was identified in 2011.

One could look at these data and ask if this is a “glass half full or half empty” situation, but I propose that clinicians and public health officials should not look at these data and be reassured that rates of MDR-gonorrhea remained stable between 2010 and 2016. According to a recent surveillance report released by the CDC, the absolute number of cases of gonorrhea has continued to rise. In 2017, there were 555,608 cases reported in the United States, a 67% increase since 2013. If we assume that rates of resistance in 2017 were similar to those in 2016, that’s more than 5,000 cases of MDR-gonorrhea in a single year.

“That’s bad,” one of my dining companions agreed. “But is gonorrhea really a pediatric issue?”

To answer that question, we just have to look at the numbers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, the percentage of high school students who had ever had sex was approximately 40% and about 10% of students had four or more lifetime partners. More than 45% of sexually active students denied the use of a condom during the last sexual intercourse. Certainly, that puts many teenagers at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that public health authorities report that half of all new STIs occur in individuals aged 15-24 years. Moreover, 25% of sexually active adolescent girls contract at least one STI.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United States, and according to the CDC, rates of disease in 2017 were highest among adolescents and young adults. In females specifically, the highest rates of gonorrhea were observed among those aged 20-24 years (684.8 cases per 100,000 females) and 15-19 years (557.4 cases per 100,000 females).

It makes sense that pediatricians and parents advocate for making the reduction of gonorrhea transmission rates a public health priority. We also need to recognize that prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. Since 2015, dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only CDC-recommended treatment for gonorrhea.

At that dinner party, my closest friend, who also happens to be a pediatrician, rolled her eyes and shot me look that I’m sure meant, “Nobody really wants to talk about gonorrhea over dessert.” Still, because she is a good friend she said, “So basically you’re saying that and if this keeps up, we may see kids with untreatable infection. Now that is scary.”

I kept quiet after that but I wanted to mention that in 2017, less than 85% of patients diagnosed with gonorrhea at selected surveillance sites received the recommended treatment with two antibiotics. Patients with inadequately treated gonorrhea are at risk for a host of sequelae. Women can develop pelvic inflammatory disease, abscesses, chronic pelvic pain, and damage of the fallopian tubes that can lead to infertility. Men can develop epididymitis, which occasionally results in infertility. Rarely, N. gonorrhoeae can spread to the blood and cause life-threatening infection. Of course, patients who aren’t treated appropriately may continue to spread the bacteria. Scary? You bet.

For pediatricians who need a refresher course in the treatment of STIs, there are free resources available. The CDC’s 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines are available in a free app; the app contains a nice refresher on taking a sexual history. There also is a print version, wall chart, and pocket guide. Providers also may want to check out the National STD Curriculum offered by the University of Washington STD Prevention Training Center and the University of Washington. Visit https://www.std.uw.edu/.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

I think the question was intended as polite, dinner party chit chat ... maybe an attempt by a gracious hostess to make sure everyone was engaged in conversation.

“So what pediatric infectious disease should parents be most worried about?” she asked me.

I’ll admit that a couple of perfectly respectable and noncontroversial possibilities crossed my mind before I answered.

Acute flaccid myelitis? Measles?

When I replied, “gonorrhea,” conversation at the table pretty much stopped.

Let me explain. Acute flaccid myelitis is a polio-like neurologic condition that has been grabbing headlines. Yes, it is concerning that most cases have occurred in children and some affected children are left with long-term deficits. Technically though, AFM is a neurologic rather than an infectious disease. When cases occur, we suspect a viral infection but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no pathogen has been consistently identified from the spinal fluid of infected patients. From August 2014 to September 2018, the CDC received information on 368 confirmed cases, so AFM fortunately is still rare.

News reports describe measles outbreaks raging in Europe – more than 41,000 cases so far this year, and 40 deaths – and warn that the United States could be next. But let’s be honest: We have a safe and effective vaccine for measles and outbreaks like this don’t happen when individuals are appropriately immunized. Parents, immunize your children. If you are lucky enough to be traveling to Europe with your baby, remember that MMR vaccine is indicated for 6- to 11-month olds, but it doesn’t count in the 2-dose series.

But gonorrhea?

In 2017, the World Health Organization included Neisseria gonorrhoeae on its list of bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health and for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. The popular media are calling N. gonorrhoeae one of the new “superbugs.” Globally, patients are being diagnosed with strains of gonorrhea that are resistant to all commonly used antibiotics. As reported during IDWeek 2018 this October, patients also are being diagnosed in the United States.

Sancta St. Cyr, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her colleagues reported data from the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) and trends in multidrug resistant (MDR) and extensively-drug resistant (XDR) gonorrhea in the United States. A gonococcal isolate with resistance or elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) to greater than or equal to two classes of antimicrobials is classified as MDR and an isolate with elevated MICs to greater than or equal to three classes of antimicrobials is classified as XDR. The MIC is the lowest antimicrobial concentration that inhibits growth of bacteria in the laboratory and rising MICs – evidence that higher levels of an antibiotic are needed to stop bacterial growth – can be an early indicator that resistance is emerging.

More than 150,000 gonococcal isolates were tested between 1987 and 2016. The first isolates with elevated MICs to cephalosporins and macrolides were identified in 1998, and since 2011, MDR resistance rates have hovered around 1%. In 2016, the rate was 1.1%, down from 1.3% in 2011. A single XDR isolate with resistance to fluoroquinolones with elevated MICs to both cephalosporins and macrolides was identified in 2011.

One could look at these data and ask if this is a “glass half full or half empty” situation, but I propose that clinicians and public health officials should not look at these data and be reassured that rates of MDR-gonorrhea remained stable between 2010 and 2016. According to a recent surveillance report released by the CDC, the absolute number of cases of gonorrhea has continued to rise. In 2017, there were 555,608 cases reported in the United States, a 67% increase since 2013. If we assume that rates of resistance in 2017 were similar to those in 2016, that’s more than 5,000 cases of MDR-gonorrhea in a single year.

“That’s bad,” one of my dining companions agreed. “But is gonorrhea really a pediatric issue?”

To answer that question, we just have to look at the numbers. According to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, the percentage of high school students who had ever had sex was approximately 40% and about 10% of students had four or more lifetime partners. More than 45% of sexually active students denied the use of a condom during the last sexual intercourse. Certainly, that puts many teenagers at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that public health authorities report that half of all new STIs occur in individuals aged 15-24 years. Moreover, 25% of sexually active adolescent girls contract at least one STI.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United States, and according to the CDC, rates of disease in 2017 were highest among adolescents and young adults. In females specifically, the highest rates of gonorrhea were observed among those aged 20-24 years (684.8 cases per 100,000 females) and 15-19 years (557.4 cases per 100,000 females).

It makes sense that pediatricians and parents advocate for making the reduction of gonorrhea transmission rates a public health priority. We also need to recognize that prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical. Since 2015, dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin is the only CDC-recommended treatment for gonorrhea.

At that dinner party, my closest friend, who also happens to be a pediatrician, rolled her eyes and shot me look that I’m sure meant, “Nobody really wants to talk about gonorrhea over dessert.” Still, because she is a good friend she said, “So basically you’re saying that and if this keeps up, we may see kids with untreatable infection. Now that is scary.”

I kept quiet after that but I wanted to mention that in 2017, less than 85% of patients diagnosed with gonorrhea at selected surveillance sites received the recommended treatment with two antibiotics. Patients with inadequately treated gonorrhea are at risk for a host of sequelae. Women can develop pelvic inflammatory disease, abscesses, chronic pelvic pain, and damage of the fallopian tubes that can lead to infertility. Men can develop epididymitis, which occasionally results in infertility. Rarely, N. gonorrhoeae can spread to the blood and cause life-threatening infection. Of course, patients who aren’t treated appropriately may continue to spread the bacteria. Scary? You bet.

For pediatricians who need a refresher course in the treatment of STIs, there are free resources available. The CDC’s 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines are available in a free app; the app contains a nice refresher on taking a sexual history. There also is a print version, wall chart, and pocket guide. Providers also may want to check out the National STD Curriculum offered by the University of Washington STD Prevention Training Center and the University of Washington. Visit https://www.std.uw.edu/.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Don’t give up on influenza vaccine

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.