User login

Communication and collaboration: An elusive goal

In recent months I’ve participated in several system-level efforts to reduce avoidable readmissions, with considerable focus placed upon handoff communication. Over the arc of my career, handoff communication has become increasingly important as inpatient care becomes more fragmented, resulting in several national initiatives. To date, there has been no such effort placed upon communication during the hospitalization.

The Joint Commission has estimated that up to 70% of sentinel events have poor interprofessional communication as a contributing factor. HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) domains emphasize communication between physicians, nurses, and patients. Patient care suffers when health care teams do not communicate effectively, and patient satisfaction follows suit.

A few recent examples from the palliative care service:

• A 54-year-old male hospitalized with cord compression secondary to malignancy and infection was evaluated by five different surgical subspecialists over a 6-day period. An additional 4 days passed before the surgeons were able to speak and agree upon a plan.

• A 16-year-old girl with epilepsy was admitted after elective orthognathic surgery. It took 2 weeks of effort (preoperatively) on the part of her parents to ensure that the surgeon and neurologist developed a plan for antiepileptic therapy while the patient was NPO for 5 days.

• An ethics case conference was called to discuss the case of a 62-year-old woman with cirrhosis and sepsis. Two of the providers involved disagreed over the patient’s prognosis and whether enteral nutrition should be continued. At the case conference, the providers were able to discuss the case face to face, and the issue was resolved. Prior to the meeting, they had not discussed the case except through progress notes.

It is curious that, in the age of nearly continuous communication via text, e-mail, Internet, and even wearable devices, we physicians have such difficulty having a quick conversation about a patient over the phone. How can this be? In my practice, I have almost no problem reaching my colleagues when there is an emergency. In the nonemergent situation, however, it is more complicated. I don’t want to pull my colleague away from a patient (whether office- or hospital-based) for an important, but nonurgent matter. For my hospital-based colleagues, there is no office staff with whom to leave a message.

As we are all being asked to see more patients, the time for reviewing charts and returning calls is progressively reduced. Standard text messaging is not HIPAA compliant; however, there are fee-based HIPAA-compliant text applications. Our local county medical society offers this as a benefit of membership, but to date only a minority of my colleagues are users.

As we move toward more team-based care and pay for performance, it is imperative for physicians to agree upon standards for communication and for health care systems to invest in infrastructure to facilitate effective communication and collaboration. If we fail to do so, it is likely that external forces (third-party payers, regulatory agencies, etc.) will impose their own standards, without our input.

Dr. Fredholm and colleague Dr. Stephen Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. They alternate contributions to the monthly Palliatively Speaking blog.

In recent months I’ve participated in several system-level efforts to reduce avoidable readmissions, with considerable focus placed upon handoff communication. Over the arc of my career, handoff communication has become increasingly important as inpatient care becomes more fragmented, resulting in several national initiatives. To date, there has been no such effort placed upon communication during the hospitalization.

The Joint Commission has estimated that up to 70% of sentinel events have poor interprofessional communication as a contributing factor. HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) domains emphasize communication between physicians, nurses, and patients. Patient care suffers when health care teams do not communicate effectively, and patient satisfaction follows suit.

A few recent examples from the palliative care service:

• A 54-year-old male hospitalized with cord compression secondary to malignancy and infection was evaluated by five different surgical subspecialists over a 6-day period. An additional 4 days passed before the surgeons were able to speak and agree upon a plan.

• A 16-year-old girl with epilepsy was admitted after elective orthognathic surgery. It took 2 weeks of effort (preoperatively) on the part of her parents to ensure that the surgeon and neurologist developed a plan for antiepileptic therapy while the patient was NPO for 5 days.

• An ethics case conference was called to discuss the case of a 62-year-old woman with cirrhosis and sepsis. Two of the providers involved disagreed over the patient’s prognosis and whether enteral nutrition should be continued. At the case conference, the providers were able to discuss the case face to face, and the issue was resolved. Prior to the meeting, they had not discussed the case except through progress notes.

It is curious that, in the age of nearly continuous communication via text, e-mail, Internet, and even wearable devices, we physicians have such difficulty having a quick conversation about a patient over the phone. How can this be? In my practice, I have almost no problem reaching my colleagues when there is an emergency. In the nonemergent situation, however, it is more complicated. I don’t want to pull my colleague away from a patient (whether office- or hospital-based) for an important, but nonurgent matter. For my hospital-based colleagues, there is no office staff with whom to leave a message.

As we are all being asked to see more patients, the time for reviewing charts and returning calls is progressively reduced. Standard text messaging is not HIPAA compliant; however, there are fee-based HIPAA-compliant text applications. Our local county medical society offers this as a benefit of membership, but to date only a minority of my colleagues are users.

As we move toward more team-based care and pay for performance, it is imperative for physicians to agree upon standards for communication and for health care systems to invest in infrastructure to facilitate effective communication and collaboration. If we fail to do so, it is likely that external forces (third-party payers, regulatory agencies, etc.) will impose their own standards, without our input.

Dr. Fredholm and colleague Dr. Stephen Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. They alternate contributions to the monthly Palliatively Speaking blog.

In recent months I’ve participated in several system-level efforts to reduce avoidable readmissions, with considerable focus placed upon handoff communication. Over the arc of my career, handoff communication has become increasingly important as inpatient care becomes more fragmented, resulting in several national initiatives. To date, there has been no such effort placed upon communication during the hospitalization.

The Joint Commission has estimated that up to 70% of sentinel events have poor interprofessional communication as a contributing factor. HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) domains emphasize communication between physicians, nurses, and patients. Patient care suffers when health care teams do not communicate effectively, and patient satisfaction follows suit.

A few recent examples from the palliative care service:

• A 54-year-old male hospitalized with cord compression secondary to malignancy and infection was evaluated by five different surgical subspecialists over a 6-day period. An additional 4 days passed before the surgeons were able to speak and agree upon a plan.

• A 16-year-old girl with epilepsy was admitted after elective orthognathic surgery. It took 2 weeks of effort (preoperatively) on the part of her parents to ensure that the surgeon and neurologist developed a plan for antiepileptic therapy while the patient was NPO for 5 days.

• An ethics case conference was called to discuss the case of a 62-year-old woman with cirrhosis and sepsis. Two of the providers involved disagreed over the patient’s prognosis and whether enteral nutrition should be continued. At the case conference, the providers were able to discuss the case face to face, and the issue was resolved. Prior to the meeting, they had not discussed the case except through progress notes.

It is curious that, in the age of nearly continuous communication via text, e-mail, Internet, and even wearable devices, we physicians have such difficulty having a quick conversation about a patient over the phone. How can this be? In my practice, I have almost no problem reaching my colleagues when there is an emergency. In the nonemergent situation, however, it is more complicated. I don’t want to pull my colleague away from a patient (whether office- or hospital-based) for an important, but nonurgent matter. For my hospital-based colleagues, there is no office staff with whom to leave a message.

As we are all being asked to see more patients, the time for reviewing charts and returning calls is progressively reduced. Standard text messaging is not HIPAA compliant; however, there are fee-based HIPAA-compliant text applications. Our local county medical society offers this as a benefit of membership, but to date only a minority of my colleagues are users.

As we move toward more team-based care and pay for performance, it is imperative for physicians to agree upon standards for communication and for health care systems to invest in infrastructure to facilitate effective communication and collaboration. If we fail to do so, it is likely that external forces (third-party payers, regulatory agencies, etc.) will impose their own standards, without our input.

Dr. Fredholm and colleague Dr. Stephen Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. They alternate contributions to the monthly Palliatively Speaking blog.

Reconsidering comfort care

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP commented: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

"Palliatively Speaking," appears monthly at ehospitalistnews.com.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP commented: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

"Palliatively Speaking," appears monthly at ehospitalistnews.com.

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Steven Q. Simpson, FCCP commented: Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Beckanich adeptly discuss how to weigh possible life-sustaining measures in terms of whether they are providing comfort for patients and how to ensure that such treatments are discussed with patients in that context.

Additionally, they provide a very nice example of how to proceed when patients cannot communicate for themselves and have no family or other surrogates to speak for them.

Join us in the Critical Care NetWork’s eCommunity.

If you’re interested in more about these topics, you can join a discussion on this topic within the Critical Care e-Community. Simply log in to ecommunity.chestnet.org and find the Critical Care group If you’re not part of the Critical Care NetWork, log in to chestnet.org and add the Critical Care NetWork to your profile.

Questions? Contact [email protected].

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

"Palliatively Speaking," appears monthly at ehospitalistnews.com.

Reconsidering comfort care

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Recently, members of our palliative care team participated in the care of a man approaching the end of his life. The patient had suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest 4 weeks earlier, and though he had survived the immediate event, it resulted in anoxic encephalopathy, which rendered him incapable of making decisions.

When it became clear that the patient was declining despite full support, the hospital’s ethics committee was convened to determine goals of care and next steps, as the patient had no family or surrogate decision maker. After determination that the hospital staff had exercised due diligence in attempting to locate a surrogate, the physicians involved reviewed the patient’s case and recommended a change in goals to comfort care. More than one member of the committee expressed confusion as to what interventions are and are not included in comfort care, including medically administered nutrition and hydration (MANH).

Comfort care has traditionally included medications for distressing symptoms (pain, dyspnea, nausea), personal care for hygiene, and choice of place of death (home, hospital, nursing facility), usually with the assistance of a hospice agency.

As the number and complexity of interventions used near the end of life expand, clinicians and hospital staff report confusion about whether these interventions, generally considered to be life-sustaining treatments, can also be considered comfort care. We generally find that when interventions are considered in the context of the patient’s goals of care, the dilemma is clarified. Often the situation is made more complicated by considering the interventions before settling on goals. Broadly speaking, goals of care are derived from a careful consideration (by patient, physician, and family) of the natural history of the illness, expected course and prognosis, and patient preferences.

In the case of the above-referenced patient, we were unable to ascertain his goals because of neurological impairment. We did know, however, that the patient had steadfastly avoided hospitals and medical care of any kind. The attending hospitalist, pulmonologist, and palliative care physician agreed that the patient’s clinical status was declining despite all available interventions, and that his constellation of medical problems constituted a terminal condition. The physicians agreed that future ICU admission, resuscitation, and other new interventions would only prolong his dying process, but not permit him to live outside the hospital. At that time, the patient was receiving nutrition and hydration via a Dobhoff tube, and was tolerating enteral nutrition without excessive residuals or pulmonary secretions.

As with other interventions, whether or not to consider MANH a part of comfort care is individualized. In this patient’s case, in the absence of evidence that he would not want MANH, it was continued. Other patients have expressed the wish that they would under no circumstances accept MANH while receiving comfort care. Both are correct as long as they reflect that patient’s wishes.

With respect to other interventions – including but not limited to BiPAP, inotrope infusion, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and transfusions – whether or not they provide comfort is a decision to be made jointly by the patient and physician(s). As advances in medicine allow patients to live longer with serious illness, the definition of comfort care must also expand.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

‘One call’ pilot program made chronic pain a priority

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

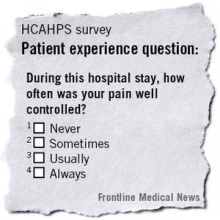

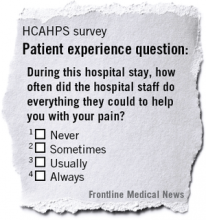

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

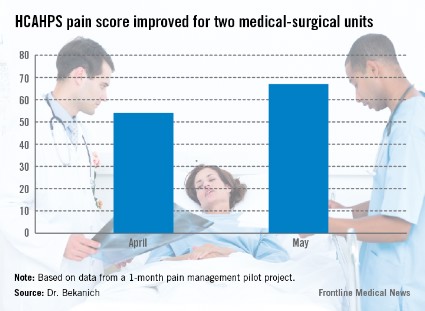

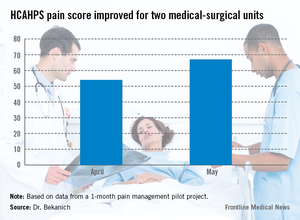

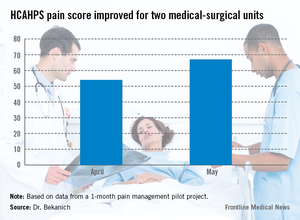

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at [email protected].

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at [email protected].

Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.

Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.

Creation of a bright spot in the hospital for pain management was not the only benefit. This short pilot project created what we see as elements of sustainability on the nursing staff and providers – getting nurses and physicians on the same page about the goals of pain management, looking at pain through a more refined lens, and building an improved sense of teamwork needed to deliver this complex care.

Our physician colleagues appreciated this service to the point that we had daily requests to include patients in the pilot that were not on the participating units. Response for the program was so enthusiastic that it incurred no additional costs. Everyone who took part did so on a voluntary basis, and those who don’t normally take call at nights or on weekends did so because of their commitment to the cause.

Most importantly, patients and families were grateful, and there was a recurrent feeling that they were well educated about their medications and other aspects of their health care.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin. Share your thoughts with Dr. Bekanich at [email protected].

Hydrocodone rescheduling: Intended and unintended consequences

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration announced that it will submit a formal recommendation to the Department of Health and Human Services to reclassify hydrocodone combination products as Schedule II.Efforts to reschedule hydrocodone date back several years and originate from the increase in overdose deaths attributed to hydrocodone as well as the drug’s relative overrepresentation in opioid abuse.

Hydrocodone has been the most prescribed drug in the United States for more than 5 years – more than medications for hypertension, diabetes, and infections, just to name a few. Studies of opioid abuse have found the majority of diverted opioids are obtained from a friend or relative who received the drug from a treating physician (as opposed to buying on the street or from a "pill mill"). Paradoxically, the FDA simultaneously approved Zohydro ER, a long-acting hydrocodone product, despite an 11-2 vote against approval in the FDA’s own advisory committee.

Our colleagues are understandably confused by these developments. Physicians and patients alike perceive that hydrocodone is weaker than other opioids, largely because it is not currently classified as Schedule II. In states with Prescription Monitoring Programs, this misperception is increased by the fact that hydrocodone prescriptions do not require a special prescription pad. Prescribers often are very surprised to discover that hydrocodone and morphine are 1:1 in opioid equianalgesic tables (Clin. J. Pain 19:286-97). While a change in the schedule classification for a drug has no bearing on its pharmacokinetics or safety profile, it will have the intended effect of decreasing the number of prescriptions written. It remains to be seen whether this change will limit access to opioids for patients with legitimate need for opioids, as is feared by many chronic pain patients and their advocates. On the other hand, there will be no perverse incentive to use a combination opioid, with consequent increased risk of hepatotoxicity from acetaminophen.

We suspect that hospitals will need to devote significant resources to early transition from parenteral to oral opioids, with subsequent transition away from opioids altogether as part of the discharge planning process. Additional time will need to be allotted for counseling patients and their families about the rationale and timing of these transitions. Furthermore, reclassifying hydrocodone will limit the number of refills permitted without a physician visit, which may lead to increased ED visits and duplicative testing, as well as patients who are dissatisfied with hospital care.

Chronic pain is a difficult and complex clinical problem. The evidence for long-term opioid therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain is weak, but for many patients opioid therapy is the only choice fully covered by insurance, or the only affordable choice for the uninsured/underinsured. Other modalities to be considered include but are not limited to adjuvant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants), physical therapy, exercise, lifestyle modifications, massage, acupuncture, biofeedback, and counseling. Hospital systems will bear the consequences of this change, and may be well served by developing additional service lines for pain management.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration announced that it will submit a formal recommendation to the Department of Health and Human Services to reclassify hydrocodone combination products as Schedule II.Efforts to reschedule hydrocodone date back several years and originate from the increase in overdose deaths attributed to hydrocodone as well as the drug’s relative overrepresentation in opioid abuse.

Hydrocodone has been the most prescribed drug in the United States for more than 5 years – more than medications for hypertension, diabetes, and infections, just to name a few. Studies of opioid abuse have found the majority of diverted opioids are obtained from a friend or relative who received the drug from a treating physician (as opposed to buying on the street or from a "pill mill"). Paradoxically, the FDA simultaneously approved Zohydro ER, a long-acting hydrocodone product, despite an 11-2 vote against approval in the FDA’s own advisory committee.

Our colleagues are understandably confused by these developments. Physicians and patients alike perceive that hydrocodone is weaker than other opioids, largely because it is not currently classified as Schedule II. In states with Prescription Monitoring Programs, this misperception is increased by the fact that hydrocodone prescriptions do not require a special prescription pad. Prescribers often are very surprised to discover that hydrocodone and morphine are 1:1 in opioid equianalgesic tables (Clin. J. Pain 19:286-97). While a change in the schedule classification for a drug has no bearing on its pharmacokinetics or safety profile, it will have the intended effect of decreasing the number of prescriptions written. It remains to be seen whether this change will limit access to opioids for patients with legitimate need for opioids, as is feared by many chronic pain patients and their advocates. On the other hand, there will be no perverse incentive to use a combination opioid, with consequent increased risk of hepatotoxicity from acetaminophen.

We suspect that hospitals will need to devote significant resources to early transition from parenteral to oral opioids, with subsequent transition away from opioids altogether as part of the discharge planning process. Additional time will need to be allotted for counseling patients and their families about the rationale and timing of these transitions. Furthermore, reclassifying hydrocodone will limit the number of refills permitted without a physician visit, which may lead to increased ED visits and duplicative testing, as well as patients who are dissatisfied with hospital care.

Chronic pain is a difficult and complex clinical problem. The evidence for long-term opioid therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain is weak, but for many patients opioid therapy is the only choice fully covered by insurance, or the only affordable choice for the uninsured/underinsured. Other modalities to be considered include but are not limited to adjuvant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants), physical therapy, exercise, lifestyle modifications, massage, acupuncture, biofeedback, and counseling. Hospital systems will bear the consequences of this change, and may be well served by developing additional service lines for pain management.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration announced that it will submit a formal recommendation to the Department of Health and Human Services to reclassify hydrocodone combination products as Schedule II.Efforts to reschedule hydrocodone date back several years and originate from the increase in overdose deaths attributed to hydrocodone as well as the drug’s relative overrepresentation in opioid abuse.

Hydrocodone has been the most prescribed drug in the United States for more than 5 years – more than medications for hypertension, diabetes, and infections, just to name a few. Studies of opioid abuse have found the majority of diverted opioids are obtained from a friend or relative who received the drug from a treating physician (as opposed to buying on the street or from a "pill mill"). Paradoxically, the FDA simultaneously approved Zohydro ER, a long-acting hydrocodone product, despite an 11-2 vote against approval in the FDA’s own advisory committee.

Our colleagues are understandably confused by these developments. Physicians and patients alike perceive that hydrocodone is weaker than other opioids, largely because it is not currently classified as Schedule II. In states with Prescription Monitoring Programs, this misperception is increased by the fact that hydrocodone prescriptions do not require a special prescription pad. Prescribers often are very surprised to discover that hydrocodone and morphine are 1:1 in opioid equianalgesic tables (Clin. J. Pain 19:286-97). While a change in the schedule classification for a drug has no bearing on its pharmacokinetics or safety profile, it will have the intended effect of decreasing the number of prescriptions written. It remains to be seen whether this change will limit access to opioids for patients with legitimate need for opioids, as is feared by many chronic pain patients and their advocates. On the other hand, there will be no perverse incentive to use a combination opioid, with consequent increased risk of hepatotoxicity from acetaminophen.

We suspect that hospitals will need to devote significant resources to early transition from parenteral to oral opioids, with subsequent transition away from opioids altogether as part of the discharge planning process. Additional time will need to be allotted for counseling patients and their families about the rationale and timing of these transitions. Furthermore, reclassifying hydrocodone will limit the number of refills permitted without a physician visit, which may lead to increased ED visits and duplicative testing, as well as patients who are dissatisfied with hospital care.

Chronic pain is a difficult and complex clinical problem. The evidence for long-term opioid therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain is weak, but for many patients opioid therapy is the only choice fully covered by insurance, or the only affordable choice for the uninsured/underinsured. Other modalities to be considered include but are not limited to adjuvant drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and anticonvulsants), physical therapy, exercise, lifestyle modifications, massage, acupuncture, biofeedback, and counseling. Hospital systems will bear the consequences of this change, and may be well served by developing additional service lines for pain management.

Dr. Fredholm and Dr. Bekanich are codirectors of Seton Palliative Care, part of the University of Texas Southwestern Residency Programs in Austin.