User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

Laser pill shows potential benefits over upper GI endoscopy

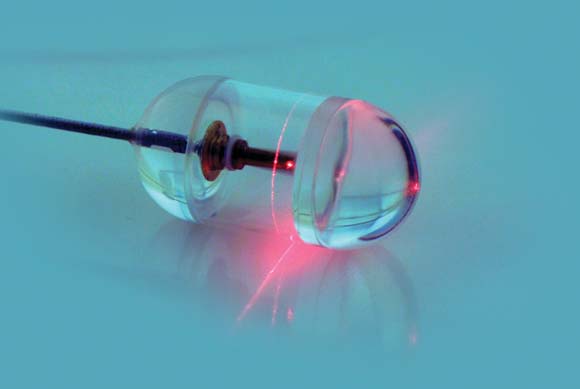

A small, swallowed, laser imaging capsule provides full-thickness imaging of the upper gastro- intestinal tract without biopsy, and is quicker and less invasive than traditional endoscopy, according to the Harvard University research-ers who are developing it.

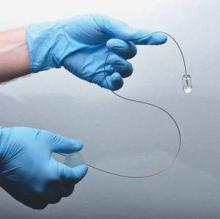

About the size of a large multivitamin pill, the transparent capsule generates a near-infrared beam that spins rapidly about its circumference during transit. Changes in the reflected light allow cross-sectional imaging of the esophagus in a few minutes. Sequential cross-sections can be compiled into three-dimensional models of the entire lumen (Nat. Med. 2013 Jan. 13 [doi: 10.1038/nm.3052]).

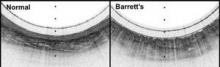

"This system gives us a convenient way to screen for Barrett?s [esophagus] that doesn?t require patient sedation, a specialized setting and equipment, or a physician who has been trained in endoscopy. By showing the three-dimensional, microscopic structure of the esophageal lining, it reveals much more detail than can be seen with even high-resolution endoscopy. The images produced have been some of the best we have seen of the esophagus," investigator Dr. Guillermo Tearney, a Harvard Medical School pathology professor and the associate director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a statement.

The capsule is on a tether, which carries its fiber optic line and laser driveshaft and helps with positioning. The capsule is pulled up and out after use, and disinfected for the next patient.

In early testing, 15 cm of esophagus in seven healthy and six Barrett?s esophagus patients was imaged in a mean of 58 seconds; it took about 6 minutes to make two down- and two up-transits. The technique, dubbed tethered capsule endomicroscopy, clearly distinguished the cellular abnormalities of Barrett?s. Standard upper GI endoscopy takes about 90 minutes.

"We originally were concerned that we might miss a lot of data because of the small size of the capsule, but we were surprised to find that, once the pill has been swallowed, it is firmly grasped by the esophagus, allowing complete microscopic imaging of the entire wall," Dr. Tearney said.

There were no complications, and 12 of the 13 subjects said they preferred the capsule to previous endoscopies.

"Because the tethered endomicroscopy pill traverses the gastrointestinal tract without visual guidance, the training required to conduct the procedure is minimal. This fact, combined with the brevity and ease with which the procedure is performed, will enable internal microscopic imaging in almost any health care setting, including in the office of the primary care physician," Dr. Tearney and his colleagues wrote in their paper.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers said they had no disclosures.

A small, swallowed, laser imaging capsule provides full-thickness imaging of the upper gastro- intestinal tract without biopsy, and is quicker and less invasive than traditional endoscopy, according to the Harvard University research-ers who are developing it.

About the size of a large multivitamin pill, the transparent capsule generates a near-infrared beam that spins rapidly about its circumference during transit. Changes in the reflected light allow cross-sectional imaging of the esophagus in a few minutes. Sequential cross-sections can be compiled into three-dimensional models of the entire lumen (Nat. Med. 2013 Jan. 13 [doi: 10.1038/nm.3052]).

"This system gives us a convenient way to screen for Barrett?s [esophagus] that doesn?t require patient sedation, a specialized setting and equipment, or a physician who has been trained in endoscopy. By showing the three-dimensional, microscopic structure of the esophageal lining, it reveals much more detail than can be seen with even high-resolution endoscopy. The images produced have been some of the best we have seen of the esophagus," investigator Dr. Guillermo Tearney, a Harvard Medical School pathology professor and the associate director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a statement.

The capsule is on a tether, which carries its fiber optic line and laser driveshaft and helps with positioning. The capsule is pulled up and out after use, and disinfected for the next patient.

In early testing, 15 cm of esophagus in seven healthy and six Barrett?s esophagus patients was imaged in a mean of 58 seconds; it took about 6 minutes to make two down- and two up-transits. The technique, dubbed tethered capsule endomicroscopy, clearly distinguished the cellular abnormalities of Barrett?s. Standard upper GI endoscopy takes about 90 minutes.

"We originally were concerned that we might miss a lot of data because of the small size of the capsule, but we were surprised to find that, once the pill has been swallowed, it is firmly grasped by the esophagus, allowing complete microscopic imaging of the entire wall," Dr. Tearney said.

There were no complications, and 12 of the 13 subjects said they preferred the capsule to previous endoscopies.

"Because the tethered endomicroscopy pill traverses the gastrointestinal tract without visual guidance, the training required to conduct the procedure is minimal. This fact, combined with the brevity and ease with which the procedure is performed, will enable internal microscopic imaging in almost any health care setting, including in the office of the primary care physician," Dr. Tearney and his colleagues wrote in their paper.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers said they had no disclosures.

A small, swallowed, laser imaging capsule provides full-thickness imaging of the upper gastro- intestinal tract without biopsy, and is quicker and less invasive than traditional endoscopy, according to the Harvard University research-ers who are developing it.

About the size of a large multivitamin pill, the transparent capsule generates a near-infrared beam that spins rapidly about its circumference during transit. Changes in the reflected light allow cross-sectional imaging of the esophagus in a few minutes. Sequential cross-sections can be compiled into three-dimensional models of the entire lumen (Nat. Med. 2013 Jan. 13 [doi: 10.1038/nm.3052]).

"This system gives us a convenient way to screen for Barrett?s [esophagus] that doesn?t require patient sedation, a specialized setting and equipment, or a physician who has been trained in endoscopy. By showing the three-dimensional, microscopic structure of the esophageal lining, it reveals much more detail than can be seen with even high-resolution endoscopy. The images produced have been some of the best we have seen of the esophagus," investigator Dr. Guillermo Tearney, a Harvard Medical School pathology professor and the associate director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in a statement.

The capsule is on a tether, which carries its fiber optic line and laser driveshaft and helps with positioning. The capsule is pulled up and out after use, and disinfected for the next patient.

In early testing, 15 cm of esophagus in seven healthy and six Barrett?s esophagus patients was imaged in a mean of 58 seconds; it took about 6 minutes to make two down- and two up-transits. The technique, dubbed tethered capsule endomicroscopy, clearly distinguished the cellular abnormalities of Barrett?s. Standard upper GI endoscopy takes about 90 minutes.

"We originally were concerned that we might miss a lot of data because of the small size of the capsule, but we were surprised to find that, once the pill has been swallowed, it is firmly grasped by the esophagus, allowing complete microscopic imaging of the entire wall," Dr. Tearney said.

There were no complications, and 12 of the 13 subjects said they preferred the capsule to previous endoscopies.

"Because the tethered endomicroscopy pill traverses the gastrointestinal tract without visual guidance, the training required to conduct the procedure is minimal. This fact, combined with the brevity and ease with which the procedure is performed, will enable internal microscopic imaging in almost any health care setting, including in the office of the primary care physician," Dr. Tearney and his colleagues wrote in their paper.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers said they had no disclosures.

Major Finding: In early testing, 15 cm of esophagus was imaged in a mean of 58 seconds and clearly distinguished the cellular abnormalities of Barrett?s esophagus; it took about 6 minutes to make two down- and two up-transits.

Data Source: A pilot study to image the esophagus in seven healthy patients and six with Barrett?s esophagus.

Disclosures: The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators said they had no disclosures.

Bariatric surgery advancement spurs guideline update

Weight loss surgery patients should get routine copper supplements along with other vitamins and minerals, according to newly updated bariatric surgery guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The groups call for 2 mg/day to offset the potential for surgery to cause a deficiency. Although routine copper screening isn’t necessary after the procedure, copper levels should be assessed and treated as needed in patients with anemia, neutropenia, myeloneuropathy, and impaired wound healing.

The copper recommendations are new since the guidelines were last published in 2008. Other recommendations – there are 74 in all – have been revised to incorporate new advances in weight loss surgery and an improved evidence base. Changes are pointed out where they’ve been made, and the level of evidence cited for each assertion. Pre- and postoperative bariatric surgery checklists have been added as well, to help avoid errors.

"This is actually a very unique collaboration among the internists represented by the endocrinologists and the obesity people and the surgeons. We actually agreed on all these things. The main intent is to assist with clinical decision making," including selecting patients and procedures and perioperative management, said lead author Dr. Jeffrey Mechanick, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and director of metabolic support at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"We scrutinized every recommendation one by one in the context of the new data. In many cases the recommendations changed," he said in an interview.

Another new recommendation is for patients to be followed by their primary care physicians and screened for cancer prior to surgery, as appropriate for age and risk. Dr. Mechanick and his colleagues have also given more attention to consent, behavioral, and psychiatric issues as well as weight loss surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes.

There’s more information on sleeve gastrectomy, as well. Considered experimental in 2008, it’s now "approved and being done more widely. There are some very nice data about its metabolic effects, independent from just the weight loss effect, effects on glycemic control, and cardiovascular risk. It was very important to devote a fair amount of time" to the procedure, he said.

The guidelines note that "sleeve gastrectomy has demonstrated benefits comparable to other bariatric procedures. ... A national risk-adjusted database positions [it] between the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in terms of weight loss, co-morbidity resolution, and complications."

"We [also] addressed two issues which were quite controversial, and are still rather unsettled. The first is the use of the lap band for mild obesity. The second is the use of these weight loss procedures specifically for patients with type 2 diabetes for glycemic control. Since 2008, there’ve been a lot more data" about the issues, he said, just as there’ve been more data about the need for copper supplementation.

As in 2008, the guidelines do not recommend bariatric surgery solely for glycemic control. "We still don’t have an absolute indication for ‘diabetes surgery,’ but we do recognize the existence of the salutary effects on glycemic control when these procedures are done for weight loss. It was important for the reader to be exposed to this information," Dr. Mechanick said.

Regarding surgery in the mildly obese, the guidelines note that patients with a body mass index of 30-34.9 kg/m2 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome "may also be offered a bariatric procedure, although current evidence is limited by the number of subjects studied and lack of long-term data demonstrating net benefit."

The guidelines will be published in the March/April 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice and March 2013 issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases.

Dr. Mechanick disclosed compensation from Abbott Nutrition for lectures and program development.

From preoperative evaluation through bariatric

surgery and onward through long-term postoperative health management, weight

loss surgery and the medical care associated with it is, obligatorily, a

thoroughly interdisciplinary effort. Endocrinologists and internists on the

bariatrics team spearhead lifestyle management, medical weight loss, and

long-term postoperative care and efforts to maintain durable weight loss.

Surgeons, endocrinologists, and internists work together to select patients

appropriate for bariatric surgery, to choose the weight-loss surgery best

suited to each individual patient, and to provide the proper preoperative

evaluation. Surgeons perform the appropriate bariatric operation and oversee

immediate postoperative and short-term perioperative care, and, frequently in

concert with gastroenterologists, internists, and endocrinologists, manage

complications that can result from bariatric surgery. Finally, long-term

continuity of medical care and durable maintenance of weight loss is again

directed by the endocrinologist and internist.

Thus, given that the entire bariatric care schema is

such an interdisciplinary effort, clinical practice guidelines for the

management of bariatric surgical patients must also be the product of an

analogous interdisciplinary effort. It is with this aim and in this spirit that

the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), The Obesity

Society (TOS), and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (AAMBS)

published their initial Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Perioperative

Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery

Patient in 2008. The same cooperating societies have just published their

sequel with numerous substantive additions, changes, and refinements. The

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and

Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient – 2013 Update: Cosponsored

by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery was published jointly in

the March issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Disease, and in the

March/April issue of Endocrine Practice.

Clearly, much has changed in the bariatric landscape

in the intervening half-decade. Laparoscopic gastric band surgery has declined,

while sleeve gastrectomy has gained traction as a restrictive bariatric

operation with more robust weight loss and glycemic effects. The

increasingly recognized impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery not only on

weight loss, but also on glycemic control and other endocrinologic endpoints

has prompted studies to determine if such benefits might also result from

restrictive-only bariatric surgeries such as sleeve gastrectomy, and initial

results appear encouraging. The arrival of more and higher-quality data with

longer-term follow up of a greater variety of endpoints has led to the ability

of these updated guidelines to provide an increasing number of more specific,

data-driven recommendations related to the broader spectrum of bariatric

surgical procedures and anatomies managed by clinicians today. They cover every

aspect of the bariatric surgical patient, from preoperative evaluation through

surgery, to postoperative management, all with more solidly outcomes-based

recommendations from over 400 references, with user-friendly and more

error-proof preoperative and postoperative care checklists, while still

arriving at such expert guidelines through interdisciplinary study and

agreement in this timely update.

John A. Martin, M.D., is associate

professor of medicine and surgery and director of endoscopy, Northwestern

University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

From preoperative evaluation through bariatric

surgery and onward through long-term postoperative health management, weight

loss surgery and the medical care associated with it is, obligatorily, a

thoroughly interdisciplinary effort. Endocrinologists and internists on the

bariatrics team spearhead lifestyle management, medical weight loss, and

long-term postoperative care and efforts to maintain durable weight loss.

Surgeons, endocrinologists, and internists work together to select patients

appropriate for bariatric surgery, to choose the weight-loss surgery best

suited to each individual patient, and to provide the proper preoperative

evaluation. Surgeons perform the appropriate bariatric operation and oversee

immediate postoperative and short-term perioperative care, and, frequently in

concert with gastroenterologists, internists, and endocrinologists, manage

complications that can result from bariatric surgery. Finally, long-term

continuity of medical care and durable maintenance of weight loss is again

directed by the endocrinologist and internist.

Thus, given that the entire bariatric care schema is

such an interdisciplinary effort, clinical practice guidelines for the

management of bariatric surgical patients must also be the product of an

analogous interdisciplinary effort. It is with this aim and in this spirit that

the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), The Obesity

Society (TOS), and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (AAMBS)

published their initial Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Perioperative

Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery

Patient in 2008. The same cooperating societies have just published their

sequel with numerous substantive additions, changes, and refinements. The

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and

Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient – 2013 Update: Cosponsored

by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery was published jointly in

the March issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Disease, and in the

March/April issue of Endocrine Practice.

Clearly, much has changed in the bariatric landscape

in the intervening half-decade. Laparoscopic gastric band surgery has declined,

while sleeve gastrectomy has gained traction as a restrictive bariatric

operation with more robust weight loss and glycemic effects. The

increasingly recognized impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery not only on

weight loss, but also on glycemic control and other endocrinologic endpoints

has prompted studies to determine if such benefits might also result from

restrictive-only bariatric surgeries such as sleeve gastrectomy, and initial

results appear encouraging. The arrival of more and higher-quality data with

longer-term follow up of a greater variety of endpoints has led to the ability

of these updated guidelines to provide an increasing number of more specific,

data-driven recommendations related to the broader spectrum of bariatric

surgical procedures and anatomies managed by clinicians today. They cover every

aspect of the bariatric surgical patient, from preoperative evaluation through

surgery, to postoperative management, all with more solidly outcomes-based

recommendations from over 400 references, with user-friendly and more

error-proof preoperative and postoperative care checklists, while still

arriving at such expert guidelines through interdisciplinary study and

agreement in this timely update.

John A. Martin, M.D., is associate

professor of medicine and surgery and director of endoscopy, Northwestern

University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

From preoperative evaluation through bariatric

surgery and onward through long-term postoperative health management, weight

loss surgery and the medical care associated with it is, obligatorily, a

thoroughly interdisciplinary effort. Endocrinologists and internists on the

bariatrics team spearhead lifestyle management, medical weight loss, and

long-term postoperative care and efforts to maintain durable weight loss.

Surgeons, endocrinologists, and internists work together to select patients

appropriate for bariatric surgery, to choose the weight-loss surgery best

suited to each individual patient, and to provide the proper preoperative

evaluation. Surgeons perform the appropriate bariatric operation and oversee

immediate postoperative and short-term perioperative care, and, frequently in

concert with gastroenterologists, internists, and endocrinologists, manage

complications that can result from bariatric surgery. Finally, long-term

continuity of medical care and durable maintenance of weight loss is again

directed by the endocrinologist and internist.

Thus, given that the entire bariatric care schema is

such an interdisciplinary effort, clinical practice guidelines for the

management of bariatric surgical patients must also be the product of an

analogous interdisciplinary effort. It is with this aim and in this spirit that

the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), The Obesity

Society (TOS), and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (AAMBS)

published their initial Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Perioperative

Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery

Patient in 2008. The same cooperating societies have just published their

sequel with numerous substantive additions, changes, and refinements. The

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and

Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient – 2013 Update: Cosponsored

by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery was published jointly in

the March issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Disease, and in the

March/April issue of Endocrine Practice.

Clearly, much has changed in the bariatric landscape

in the intervening half-decade. Laparoscopic gastric band surgery has declined,

while sleeve gastrectomy has gained traction as a restrictive bariatric

operation with more robust weight loss and glycemic effects. The

increasingly recognized impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery not only on

weight loss, but also on glycemic control and other endocrinologic endpoints

has prompted studies to determine if such benefits might also result from

restrictive-only bariatric surgeries such as sleeve gastrectomy, and initial

results appear encouraging. The arrival of more and higher-quality data with

longer-term follow up of a greater variety of endpoints has led to the ability

of these updated guidelines to provide an increasing number of more specific,

data-driven recommendations related to the broader spectrum of bariatric

surgical procedures and anatomies managed by clinicians today. They cover every

aspect of the bariatric surgical patient, from preoperative evaluation through

surgery, to postoperative management, all with more solidly outcomes-based

recommendations from over 400 references, with user-friendly and more

error-proof preoperative and postoperative care checklists, while still

arriving at such expert guidelines through interdisciplinary study and

agreement in this timely update.

John A. Martin, M.D., is associate

professor of medicine and surgery and director of endoscopy, Northwestern

University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

Weight loss surgery patients should get routine copper supplements along with other vitamins and minerals, according to newly updated bariatric surgery guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The groups call for 2 mg/day to offset the potential for surgery to cause a deficiency. Although routine copper screening isn’t necessary after the procedure, copper levels should be assessed and treated as needed in patients with anemia, neutropenia, myeloneuropathy, and impaired wound healing.

The copper recommendations are new since the guidelines were last published in 2008. Other recommendations – there are 74 in all – have been revised to incorporate new advances in weight loss surgery and an improved evidence base. Changes are pointed out where they’ve been made, and the level of evidence cited for each assertion. Pre- and postoperative bariatric surgery checklists have been added as well, to help avoid errors.

"This is actually a very unique collaboration among the internists represented by the endocrinologists and the obesity people and the surgeons. We actually agreed on all these things. The main intent is to assist with clinical decision making," including selecting patients and procedures and perioperative management, said lead author Dr. Jeffrey Mechanick, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and director of metabolic support at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"We scrutinized every recommendation one by one in the context of the new data. In many cases the recommendations changed," he said in an interview.

Another new recommendation is for patients to be followed by their primary care physicians and screened for cancer prior to surgery, as appropriate for age and risk. Dr. Mechanick and his colleagues have also given more attention to consent, behavioral, and psychiatric issues as well as weight loss surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes.

There’s more information on sleeve gastrectomy, as well. Considered experimental in 2008, it’s now "approved and being done more widely. There are some very nice data about its metabolic effects, independent from just the weight loss effect, effects on glycemic control, and cardiovascular risk. It was very important to devote a fair amount of time" to the procedure, he said.

The guidelines note that "sleeve gastrectomy has demonstrated benefits comparable to other bariatric procedures. ... A national risk-adjusted database positions [it] between the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in terms of weight loss, co-morbidity resolution, and complications."

"We [also] addressed two issues which were quite controversial, and are still rather unsettled. The first is the use of the lap band for mild obesity. The second is the use of these weight loss procedures specifically for patients with type 2 diabetes for glycemic control. Since 2008, there’ve been a lot more data" about the issues, he said, just as there’ve been more data about the need for copper supplementation.

As in 2008, the guidelines do not recommend bariatric surgery solely for glycemic control. "We still don’t have an absolute indication for ‘diabetes surgery,’ but we do recognize the existence of the salutary effects on glycemic control when these procedures are done for weight loss. It was important for the reader to be exposed to this information," Dr. Mechanick said.

Regarding surgery in the mildly obese, the guidelines note that patients with a body mass index of 30-34.9 kg/m2 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome "may also be offered a bariatric procedure, although current evidence is limited by the number of subjects studied and lack of long-term data demonstrating net benefit."

The guidelines will be published in the March/April 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice and March 2013 issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases.

Dr. Mechanick disclosed compensation from Abbott Nutrition for lectures and program development.

Weight loss surgery patients should get routine copper supplements along with other vitamins and minerals, according to newly updated bariatric surgery guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

The groups call for 2 mg/day to offset the potential for surgery to cause a deficiency. Although routine copper screening isn’t necessary after the procedure, copper levels should be assessed and treated as needed in patients with anemia, neutropenia, myeloneuropathy, and impaired wound healing.

The copper recommendations are new since the guidelines were last published in 2008. Other recommendations – there are 74 in all – have been revised to incorporate new advances in weight loss surgery and an improved evidence base. Changes are pointed out where they’ve been made, and the level of evidence cited for each assertion. Pre- and postoperative bariatric surgery checklists have been added as well, to help avoid errors.

"This is actually a very unique collaboration among the internists represented by the endocrinologists and the obesity people and the surgeons. We actually agreed on all these things. The main intent is to assist with clinical decision making," including selecting patients and procedures and perioperative management, said lead author Dr. Jeffrey Mechanick, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and director of metabolic support at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

"We scrutinized every recommendation one by one in the context of the new data. In many cases the recommendations changed," he said in an interview.

Another new recommendation is for patients to be followed by their primary care physicians and screened for cancer prior to surgery, as appropriate for age and risk. Dr. Mechanick and his colleagues have also given more attention to consent, behavioral, and psychiatric issues as well as weight loss surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes.

There’s more information on sleeve gastrectomy, as well. Considered experimental in 2008, it’s now "approved and being done more widely. There are some very nice data about its metabolic effects, independent from just the weight loss effect, effects on glycemic control, and cardiovascular risk. It was very important to devote a fair amount of time" to the procedure, he said.

The guidelines note that "sleeve gastrectomy has demonstrated benefits comparable to other bariatric procedures. ... A national risk-adjusted database positions [it] between the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in terms of weight loss, co-morbidity resolution, and complications."

"We [also] addressed two issues which were quite controversial, and are still rather unsettled. The first is the use of the lap band for mild obesity. The second is the use of these weight loss procedures specifically for patients with type 2 diabetes for glycemic control. Since 2008, there’ve been a lot more data" about the issues, he said, just as there’ve been more data about the need for copper supplementation.

As in 2008, the guidelines do not recommend bariatric surgery solely for glycemic control. "We still don’t have an absolute indication for ‘diabetes surgery,’ but we do recognize the existence of the salutary effects on glycemic control when these procedures are done for weight loss. It was important for the reader to be exposed to this information," Dr. Mechanick said.

Regarding surgery in the mildly obese, the guidelines note that patients with a body mass index of 30-34.9 kg/m2 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome "may also be offered a bariatric procedure, although current evidence is limited by the number of subjects studied and lack of long-term data demonstrating net benefit."

The guidelines will be published in the March/April 2013 issue of Endocrine Practice and March 2013 issue of Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases.

Dr. Mechanick disclosed compensation from Abbott Nutrition for lectures and program development.

'Liberation therapy' may make MS worse

SAN DIEGO – Percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty – also known as "liberation therapy" – doesn’t help people with multiple sclerosis and may increase MS brain activity in the short term, according to a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial from the State University of New York at Buffalo, the first randomized trial to investigate the procedure.

It "was ineffective in correcting" chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), the recently described condition it targets. "The results ... caution against widespread adoption of venous angioplasty in the management of patients with MS outside of rigorous clinical trials," the investigators concluded.

The findings follow a recent Food and Drug Administration warning that PTVA (percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty) can cause deaths and injuries, including strokes, damage to the treated vein, blood clots, cranial nerve damage, abdominal bleeding, and detachment and migration of stents.

The idea is to use balloon angioplasty and stents to widen veins in the chests and necks that appear to be narrowed in some MS patients. Proponents of the procedure say that those narrowed veins impair blood flow and lead to disease progression. The researchers who discovered the problem dubbed it CCSVI. A cottage industry has since sprung up to offer PTVA to MS patients.

The FDA noted in its warning that there have been no "controlled ... rigorously conducted, properly targeted" studies of the issue; that may have changed when Dr. Robert Zivadinov, a professor in the department of neurology at SUNY-Buffalo, presented his team’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

"When you reopened those veins in the neck, I think something happened in reperfusing the brain and re-exacerbating disease activity. The message of this is clear. The majority of patients who are relapsing-remitting should not undergo this treatment," he said in an interview.

Ten patients got PTVA in the first phase of the study. The second phase randomized 9 to PTVA and 10 to a sham intervention. Most had relapsing-remitting MS.

There were no MS relapses in the first phase, but PTVA patients had more relapses (4 vs. 1; P = .389) and more MRI disease activity (cumulative number of new contrast-enhancing lesions (19 vs. 3; P = .062) and new T2 lesions (17 vs. 3; P = .066) in the 6 months following treatment in phase II.

PTVA patients also didn’t fare any better on Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores, Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite scores, 6-minute walk tests, or measures of cognition and quality of life.

"We chose very active patients who had one relapse in the previous year or [gadolinium-] enhancing lesions in the 3 months before. The sample size is small, but [more than half] of patients in the treatment group showed increased activity," Dr. Zivadinov said.

The majority of the subjects were women. On average, they were about 45 years old, had been diagnosed with MS for 11 years, and were mildly to moderately disabled (mean EDSS score about 4). Most were on interferon, glatiramer acetate, or both.

Venous angioplasty didn’t cause any serious complications, and it restored venous outflow to at least 50% of normal in most patients. Phase I patients had a better than 75% improvement overall. Phase II patients had less benefit; there were no differences in venous hemodynamic insufficiency scores between treated and sham patients.

The treatment "failed to provide any sustained improvement in venous outflow as measured through duplex and/or clinical and MRI outcomes," and "more sizable changes in venous outflow [were] associated with increased disease activity primarily noted on MRI," Dr. Zivadinov and his colleagues concluded.

The work was funded primarily by SUNY-Buffalo’s Neuroimaging Analysis Center and Baird MS Research Center. Dr. Zivadinov receives personal compensation from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Bayer, Genzyme-Sanofi, Novartis, Bracco Imaging, and Questcor Pharmaceuticals.

SAN DIEGO – Percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty – also known as "liberation therapy" – doesn’t help people with multiple sclerosis and may increase MS brain activity in the short term, according to a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial from the State University of New York at Buffalo, the first randomized trial to investigate the procedure.

It "was ineffective in correcting" chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), the recently described condition it targets. "The results ... caution against widespread adoption of venous angioplasty in the management of patients with MS outside of rigorous clinical trials," the investigators concluded.

The findings follow a recent Food and Drug Administration warning that PTVA (percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty) can cause deaths and injuries, including strokes, damage to the treated vein, blood clots, cranial nerve damage, abdominal bleeding, and detachment and migration of stents.

The idea is to use balloon angioplasty and stents to widen veins in the chests and necks that appear to be narrowed in some MS patients. Proponents of the procedure say that those narrowed veins impair blood flow and lead to disease progression. The researchers who discovered the problem dubbed it CCSVI. A cottage industry has since sprung up to offer PTVA to MS patients.

The FDA noted in its warning that there have been no "controlled ... rigorously conducted, properly targeted" studies of the issue; that may have changed when Dr. Robert Zivadinov, a professor in the department of neurology at SUNY-Buffalo, presented his team’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

"When you reopened those veins in the neck, I think something happened in reperfusing the brain and re-exacerbating disease activity. The message of this is clear. The majority of patients who are relapsing-remitting should not undergo this treatment," he said in an interview.

Ten patients got PTVA in the first phase of the study. The second phase randomized 9 to PTVA and 10 to a sham intervention. Most had relapsing-remitting MS.

There were no MS relapses in the first phase, but PTVA patients had more relapses (4 vs. 1; P = .389) and more MRI disease activity (cumulative number of new contrast-enhancing lesions (19 vs. 3; P = .062) and new T2 lesions (17 vs. 3; P = .066) in the 6 months following treatment in phase II.

PTVA patients also didn’t fare any better on Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores, Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite scores, 6-minute walk tests, or measures of cognition and quality of life.

"We chose very active patients who had one relapse in the previous year or [gadolinium-] enhancing lesions in the 3 months before. The sample size is small, but [more than half] of patients in the treatment group showed increased activity," Dr. Zivadinov said.

The majority of the subjects were women. On average, they were about 45 years old, had been diagnosed with MS for 11 years, and were mildly to moderately disabled (mean EDSS score about 4). Most were on interferon, glatiramer acetate, or both.

Venous angioplasty didn’t cause any serious complications, and it restored venous outflow to at least 50% of normal in most patients. Phase I patients had a better than 75% improvement overall. Phase II patients had less benefit; there were no differences in venous hemodynamic insufficiency scores between treated and sham patients.

The treatment "failed to provide any sustained improvement in venous outflow as measured through duplex and/or clinical and MRI outcomes," and "more sizable changes in venous outflow [were] associated with increased disease activity primarily noted on MRI," Dr. Zivadinov and his colleagues concluded.

The work was funded primarily by SUNY-Buffalo’s Neuroimaging Analysis Center and Baird MS Research Center. Dr. Zivadinov receives personal compensation from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Bayer, Genzyme-Sanofi, Novartis, Bracco Imaging, and Questcor Pharmaceuticals.

SAN DIEGO – Percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty – also known as "liberation therapy" – doesn’t help people with multiple sclerosis and may increase MS brain activity in the short term, according to a small, randomized, sham-controlled trial from the State University of New York at Buffalo, the first randomized trial to investigate the procedure.

It "was ineffective in correcting" chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), the recently described condition it targets. "The results ... caution against widespread adoption of venous angioplasty in the management of patients with MS outside of rigorous clinical trials," the investigators concluded.

The findings follow a recent Food and Drug Administration warning that PTVA (percutaneous transluminal venous angioplasty) can cause deaths and injuries, including strokes, damage to the treated vein, blood clots, cranial nerve damage, abdominal bleeding, and detachment and migration of stents.

The idea is to use balloon angioplasty and stents to widen veins in the chests and necks that appear to be narrowed in some MS patients. Proponents of the procedure say that those narrowed veins impair blood flow and lead to disease progression. The researchers who discovered the problem dubbed it CCSVI. A cottage industry has since sprung up to offer PTVA to MS patients.

The FDA noted in its warning that there have been no "controlled ... rigorously conducted, properly targeted" studies of the issue; that may have changed when Dr. Robert Zivadinov, a professor in the department of neurology at SUNY-Buffalo, presented his team’s findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

"When you reopened those veins in the neck, I think something happened in reperfusing the brain and re-exacerbating disease activity. The message of this is clear. The majority of patients who are relapsing-remitting should not undergo this treatment," he said in an interview.

Ten patients got PTVA in the first phase of the study. The second phase randomized 9 to PTVA and 10 to a sham intervention. Most had relapsing-remitting MS.

There were no MS relapses in the first phase, but PTVA patients had more relapses (4 vs. 1; P = .389) and more MRI disease activity (cumulative number of new contrast-enhancing lesions (19 vs. 3; P = .062) and new T2 lesions (17 vs. 3; P = .066) in the 6 months following treatment in phase II.

PTVA patients also didn’t fare any better on Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores, Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite scores, 6-minute walk tests, or measures of cognition and quality of life.

"We chose very active patients who had one relapse in the previous year or [gadolinium-] enhancing lesions in the 3 months before. The sample size is small, but [more than half] of patients in the treatment group showed increased activity," Dr. Zivadinov said.

The majority of the subjects were women. On average, they were about 45 years old, had been diagnosed with MS for 11 years, and were mildly to moderately disabled (mean EDSS score about 4). Most were on interferon, glatiramer acetate, or both.

Venous angioplasty didn’t cause any serious complications, and it restored venous outflow to at least 50% of normal in most patients. Phase I patients had a better than 75% improvement overall. Phase II patients had less benefit; there were no differences in venous hemodynamic insufficiency scores between treated and sham patients.

The treatment "failed to provide any sustained improvement in venous outflow as measured through duplex and/or clinical and MRI outcomes," and "more sizable changes in venous outflow [were] associated with increased disease activity primarily noted on MRI," Dr. Zivadinov and his colleagues concluded.

The work was funded primarily by SUNY-Buffalo’s Neuroimaging Analysis Center and Baird MS Research Center. Dr. Zivadinov receives personal compensation from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Bayer, Genzyme-Sanofi, Novartis, Bracco Imaging, and Questcor Pharmaceuticals.

AT THE 2013 AAN ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: A total of 19 new contrast-enhancing MRI lesions were observed in 9 "liberation therapy" MS patients within 6 months of treatment, compared with 3 lesions in 10 control patients.

Date Source: A randomized, sham-controlled trial with 29 MS patients

Disclosures: The work was funded primarily by SUNY–Buffalo’s Neuroimaging Analysis Center and Baird MS Research Center. Dr. Zivadinov receives personal compensation from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Bayer, Genzyme-Sanofi, Novartis, Bracco Imaging, and Questcor Pharmaceuticals.

Second-line indication for daclizumab seems likely

SAN DIEGO – Emerging skin and liver issues mean that daclizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody in phase III testing for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, likely will be a second-line agent if approved by the Food and Drug Administration, predicted Dr. Gavin Giovannoni, a neurology professor at the University of London.

There’s been one death from autoimmune hepatitis; researchers now monitor liver values monthly. There also have been a low number of serious cutaneous events, although no cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported.

"Because of the skin reactions and the liver, I can’t see it coming out as a first-line drug for people with relapsing-remitting MS," Dr. Giovannoni said. It might prove to be a good alternative to natalizumab, he added, noting that daclizumab, if approved, likely would be on the market in 2016.

"If you don’t develop the skin reactions and the liver problem – if you get through that hurdle – the tolerability of this drug is very good," he said in an interview.

So far, daclizumab appears to be particularly good at slowing MS progression.

"It’s having a real impact on progression. Subanalysis of people with just minor relapses still got an impact on progression. The way this drug works is by boosting the innate immune system, so its impact on progression is out of proportion to its impact on relapses," he said.

That finding was confirmed in 2-year data that Dr. Giovannoni presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In that study, 170 patients who were on placebo during the first year were randomized to monthly 150 mg or 300 mg subcutaneous injections during the second year. The 52-week annualized relapse rate (ARR) was reduced by 59% among the former placebo patients who began taking daclizumab during year 2, compared with those who remained on placebo during year 2 (0.18 vs. 0.43; P less than .001), and the proportion of patients with confirmed 3-month disability progression was reduced by 50% (5% vs. 10%; P = .033).

The study included an additional 347 patients who spent the first year on daclizumab and were randomized to either continue their dose or resume it after a 24-week treatment interruption.

Those who stayed on the agent after the first year maintained their ARR in the second year (0.148 vs. 0.165) and had fewer new/newly enlarging T2 lesions (1.2 vs. 1.85; P = .032); 88% were free of confirmed disability progression at the end of 2 years. The treatment-interruption group showed no evidence of disease rebound.

The incidence of serious infections was about 2% in both years, and the incidence of serious cutaneous events was similar (1.1% vs. 1.0%). Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase elevations five times above the upper limit of normal were less common among daclizumab treated patients in year 2 (1.5% vs. 4%).

"The efficacy of [daclizumab] was sustained through the second year of therapy and the safety profile was similar in years 1 and 2," the researchers, led by Dr. Giovannoni, concluded.

He said the autoimmune hepatitis death, which occurred in the 300-mg treatment-interruption group, could have been caught in time and prevented with routine liver function monitoring.

There was also a case of asymptomatic glomerular nephritis in the trial that resolved when daclizumab was stopped, and one case of ulcerative colitis, which can’t be pinned on the drug because MS patients are at risk for inflammatory bowel disease, he said.

The skin problems "present on their own because the patients report them," he noted.

The study was funded by Biogen Idec and Abbott Biotherapeutics. Dr. Giovannoni disclosed personal compensation and research funding from Biogen, among other companies.

SAN DIEGO – Emerging skin and liver issues mean that daclizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody in phase III testing for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, likely will be a second-line agent if approved by the Food and Drug Administration, predicted Dr. Gavin Giovannoni, a neurology professor at the University of London.

There’s been one death from autoimmune hepatitis; researchers now monitor liver values monthly. There also have been a low number of serious cutaneous events, although no cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported.

"Because of the skin reactions and the liver, I can’t see it coming out as a first-line drug for people with relapsing-remitting MS," Dr. Giovannoni said. It might prove to be a good alternative to natalizumab, he added, noting that daclizumab, if approved, likely would be on the market in 2016.

"If you don’t develop the skin reactions and the liver problem – if you get through that hurdle – the tolerability of this drug is very good," he said in an interview.

So far, daclizumab appears to be particularly good at slowing MS progression.

"It’s having a real impact on progression. Subanalysis of people with just minor relapses still got an impact on progression. The way this drug works is by boosting the innate immune system, so its impact on progression is out of proportion to its impact on relapses," he said.

That finding was confirmed in 2-year data that Dr. Giovannoni presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In that study, 170 patients who were on placebo during the first year were randomized to monthly 150 mg or 300 mg subcutaneous injections during the second year. The 52-week annualized relapse rate (ARR) was reduced by 59% among the former placebo patients who began taking daclizumab during year 2, compared with those who remained on placebo during year 2 (0.18 vs. 0.43; P less than .001), and the proportion of patients with confirmed 3-month disability progression was reduced by 50% (5% vs. 10%; P = .033).

The study included an additional 347 patients who spent the first year on daclizumab and were randomized to either continue their dose or resume it after a 24-week treatment interruption.

Those who stayed on the agent after the first year maintained their ARR in the second year (0.148 vs. 0.165) and had fewer new/newly enlarging T2 lesions (1.2 vs. 1.85; P = .032); 88% were free of confirmed disability progression at the end of 2 years. The treatment-interruption group showed no evidence of disease rebound.

The incidence of serious infections was about 2% in both years, and the incidence of serious cutaneous events was similar (1.1% vs. 1.0%). Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase elevations five times above the upper limit of normal were less common among daclizumab treated patients in year 2 (1.5% vs. 4%).

"The efficacy of [daclizumab] was sustained through the second year of therapy and the safety profile was similar in years 1 and 2," the researchers, led by Dr. Giovannoni, concluded.

He said the autoimmune hepatitis death, which occurred in the 300-mg treatment-interruption group, could have been caught in time and prevented with routine liver function monitoring.

There was also a case of asymptomatic glomerular nephritis in the trial that resolved when daclizumab was stopped, and one case of ulcerative colitis, which can’t be pinned on the drug because MS patients are at risk for inflammatory bowel disease, he said.

The skin problems "present on their own because the patients report them," he noted.

The study was funded by Biogen Idec and Abbott Biotherapeutics. Dr. Giovannoni disclosed personal compensation and research funding from Biogen, among other companies.

SAN DIEGO – Emerging skin and liver issues mean that daclizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody in phase III testing for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, likely will be a second-line agent if approved by the Food and Drug Administration, predicted Dr. Gavin Giovannoni, a neurology professor at the University of London.

There’s been one death from autoimmune hepatitis; researchers now monitor liver values monthly. There also have been a low number of serious cutaneous events, although no cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported.

"Because of the skin reactions and the liver, I can’t see it coming out as a first-line drug for people with relapsing-remitting MS," Dr. Giovannoni said. It might prove to be a good alternative to natalizumab, he added, noting that daclizumab, if approved, likely would be on the market in 2016.

"If you don’t develop the skin reactions and the liver problem – if you get through that hurdle – the tolerability of this drug is very good," he said in an interview.

So far, daclizumab appears to be particularly good at slowing MS progression.

"It’s having a real impact on progression. Subanalysis of people with just minor relapses still got an impact on progression. The way this drug works is by boosting the innate immune system, so its impact on progression is out of proportion to its impact on relapses," he said.

That finding was confirmed in 2-year data that Dr. Giovannoni presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

In that study, 170 patients who were on placebo during the first year were randomized to monthly 150 mg or 300 mg subcutaneous injections during the second year. The 52-week annualized relapse rate (ARR) was reduced by 59% among the former placebo patients who began taking daclizumab during year 2, compared with those who remained on placebo during year 2 (0.18 vs. 0.43; P less than .001), and the proportion of patients with confirmed 3-month disability progression was reduced by 50% (5% vs. 10%; P = .033).

The study included an additional 347 patients who spent the first year on daclizumab and were randomized to either continue their dose or resume it after a 24-week treatment interruption.

Those who stayed on the agent after the first year maintained their ARR in the second year (0.148 vs. 0.165) and had fewer new/newly enlarging T2 lesions (1.2 vs. 1.85; P = .032); 88% were free of confirmed disability progression at the end of 2 years. The treatment-interruption group showed no evidence of disease rebound.

The incidence of serious infections was about 2% in both years, and the incidence of serious cutaneous events was similar (1.1% vs. 1.0%). Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase elevations five times above the upper limit of normal were less common among daclizumab treated patients in year 2 (1.5% vs. 4%).

"The efficacy of [daclizumab] was sustained through the second year of therapy and the safety profile was similar in years 1 and 2," the researchers, led by Dr. Giovannoni, concluded.

He said the autoimmune hepatitis death, which occurred in the 300-mg treatment-interruption group, could have been caught in time and prevented with routine liver function monitoring.

There was also a case of asymptomatic glomerular nephritis in the trial that resolved when daclizumab was stopped, and one case of ulcerative colitis, which can’t be pinned on the drug because MS patients are at risk for inflammatory bowel disease, he said.

The skin problems "present on their own because the patients report them," he noted.

The study was funded by Biogen Idec and Abbott Biotherapeutics. Dr. Giovannoni disclosed personal compensation and research funding from Biogen, among other companies.

AT THE 2013 AAN ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: After 2 years of treatment with daclizumab, 88% of relapsing-remitting MS patients were free of progression.

Data source: Randomized trial in 517 relapsing-remitting MS patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Biogen Idec and Abbott Biotherapeutics. Dr. Giovannoni disclosed personal compensation and research funding from Biogen, among other companies.

Reducing glatiramer acetate dosing frequency seems reasonable

SAN DIEGO – It seems okay to switch patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to 40-mg glatiramer acetate injections three times a week if the usual 20-mg daily injections get to be too much, according to Dr. Omar Khan, interim chair of the neurology department at Wayne State University in Detroit.

"Our patients love what the molecule does" for them, but some want to quit if the daily shots cause too much lipoatrophy or too many injection-site reactions. "I tell them rather than going off it, go every other day. [That] alternative is okay," he said in an interview.

The assertion is based in part on the randomized, blinded GALA (Glatiramer Acetate Low Frequency Administration Study), which Dr. Khan led and presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The trial randomized 943 relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients to 40 mg of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) three times weekly and 461 patients to matched placebo injections.

After a year, the placebo patients had an annualized relapse rate of 0.505, compared with a rate of 0.331 for the glatiramer acetate (GA) patients, a 34.4% reduction (P less than .0001). Similarly, the cumulative number of new or enlarging T2 lesions was 34.7% lower in the GA group, and the cumulative number of enhancing T1 lesions was 44.8% lower (P less than .0001 for both).

Although the trial did not pit 20 mg daily against 40 mg three times a week, Dr. Khan noted that the cumulative weekly dose is similar in both regimens, and that the response seen in the 40-mg group was comparable to what would be expected with 20 mg daily.

Injection-site redness, itching, and pain were more common in the GA group, as were headaches; 8.9% of the GA patients and 6.7% of the placebo patients left the study. Those results are also consistent with 20-mg daily injections.

There were no significant baseline differences between the groups. About 70% of the patients were women, they were about 38 years old on average, and almost all were white. The mean baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale score was about 2.7 in both arms, and patients were about 8 years out from diagnosis. The GA group had a baseline T2 lesion load of 19.7 mL, while the placebo group a baseline load of 17.4 mL.

It had been at least 2 years since any of the subjects had monoclonal antibodies, at least 6 months since they had used systemic corticosteroids, and at least 2 months since using immunomodulators. All the patients were GA naïve. The majority were from eastern Europe.

"We have a small phase II immunologic study," Dr. Khan noted, that pitted 20 mg daily against 40 mg every other day. "There were a lot of advantages of taking it every other day" – fewer injection-site reactions and the like – and "immunologically there was no difference" between the two regimens, he said. The study hasn’t been published yet.

In general, "if you look at just your general clinical observations, you can’t tell" which regimen patients are using, he said.

There’s debate about whether it’s better to start patients on a daily regimen, or if it’s okay to go with less frequent injections right out of the gate.

"You might generate a better Th2 [T-cell] shift if you keep them on every day for a few months, and then alter them. It could be true. The fact is that that sample in a large cohort does not exist. [Either way,] it doesn’t change a whole lot because at 6 months [and] 12 months everybody is doing well," Dr. Khan said.

In the meantime, "many of our patients routinely take [GA] less than every other day. They skip weekends; they create their own regimens," he said.

Teva Pharmaceuticals, the maker of GA, paid for the study. Dr. Khan has received personal compensation and research support from Teva, Biogen-Idec, and other companies.

SAN DIEGO – It seems okay to switch patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to 40-mg glatiramer acetate injections three times a week if the usual 20-mg daily injections get to be too much, according to Dr. Omar Khan, interim chair of the neurology department at Wayne State University in Detroit.

"Our patients love what the molecule does" for them, but some want to quit if the daily shots cause too much lipoatrophy or too many injection-site reactions. "I tell them rather than going off it, go every other day. [That] alternative is okay," he said in an interview.

The assertion is based in part on the randomized, blinded GALA (Glatiramer Acetate Low Frequency Administration Study), which Dr. Khan led and presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The trial randomized 943 relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients to 40 mg of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) three times weekly and 461 patients to matched placebo injections.

After a year, the placebo patients had an annualized relapse rate of 0.505, compared with a rate of 0.331 for the glatiramer acetate (GA) patients, a 34.4% reduction (P less than .0001). Similarly, the cumulative number of new or enlarging T2 lesions was 34.7% lower in the GA group, and the cumulative number of enhancing T1 lesions was 44.8% lower (P less than .0001 for both).

Although the trial did not pit 20 mg daily against 40 mg three times a week, Dr. Khan noted that the cumulative weekly dose is similar in both regimens, and that the response seen in the 40-mg group was comparable to what would be expected with 20 mg daily.

Injection-site redness, itching, and pain were more common in the GA group, as were headaches; 8.9% of the GA patients and 6.7% of the placebo patients left the study. Those results are also consistent with 20-mg daily injections.

There were no significant baseline differences between the groups. About 70% of the patients were women, they were about 38 years old on average, and almost all were white. The mean baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale score was about 2.7 in both arms, and patients were about 8 years out from diagnosis. The GA group had a baseline T2 lesion load of 19.7 mL, while the placebo group a baseline load of 17.4 mL.

It had been at least 2 years since any of the subjects had monoclonal antibodies, at least 6 months since they had used systemic corticosteroids, and at least 2 months since using immunomodulators. All the patients were GA naïve. The majority were from eastern Europe.

"We have a small phase II immunologic study," Dr. Khan noted, that pitted 20 mg daily against 40 mg every other day. "There were a lot of advantages of taking it every other day" – fewer injection-site reactions and the like – and "immunologically there was no difference" between the two regimens, he said. The study hasn’t been published yet.

In general, "if you look at just your general clinical observations, you can’t tell" which regimen patients are using, he said.

There’s debate about whether it’s better to start patients on a daily regimen, or if it’s okay to go with less frequent injections right out of the gate.

"You might generate a better Th2 [T-cell] shift if you keep them on every day for a few months, and then alter them. It could be true. The fact is that that sample in a large cohort does not exist. [Either way,] it doesn’t change a whole lot because at 6 months [and] 12 months everybody is doing well," Dr. Khan said.

In the meantime, "many of our patients routinely take [GA] less than every other day. They skip weekends; they create their own regimens," he said.

Teva Pharmaceuticals, the maker of GA, paid for the study. Dr. Khan has received personal compensation and research support from Teva, Biogen-Idec, and other companies.

SAN DIEGO – It seems okay to switch patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis to 40-mg glatiramer acetate injections three times a week if the usual 20-mg daily injections get to be too much, according to Dr. Omar Khan, interim chair of the neurology department at Wayne State University in Detroit.

"Our patients love what the molecule does" for them, but some want to quit if the daily shots cause too much lipoatrophy or too many injection-site reactions. "I tell them rather than going off it, go every other day. [That] alternative is okay," he said in an interview.

The assertion is based in part on the randomized, blinded GALA (Glatiramer Acetate Low Frequency Administration Study), which Dr. Khan led and presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The trial randomized 943 relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients to 40 mg of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) three times weekly and 461 patients to matched placebo injections.

After a year, the placebo patients had an annualized relapse rate of 0.505, compared with a rate of 0.331 for the glatiramer acetate (GA) patients, a 34.4% reduction (P less than .0001). Similarly, the cumulative number of new or enlarging T2 lesions was 34.7% lower in the GA group, and the cumulative number of enhancing T1 lesions was 44.8% lower (P less than .0001 for both).

Although the trial did not pit 20 mg daily against 40 mg three times a week, Dr. Khan noted that the cumulative weekly dose is similar in both regimens, and that the response seen in the 40-mg group was comparable to what would be expected with 20 mg daily.

Injection-site redness, itching, and pain were more common in the GA group, as were headaches; 8.9% of the GA patients and 6.7% of the placebo patients left the study. Those results are also consistent with 20-mg daily injections.

There were no significant baseline differences between the groups. About 70% of the patients were women, they were about 38 years old on average, and almost all were white. The mean baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale score was about 2.7 in both arms, and patients were about 8 years out from diagnosis. The GA group had a baseline T2 lesion load of 19.7 mL, while the placebo group a baseline load of 17.4 mL.

It had been at least 2 years since any of the subjects had monoclonal antibodies, at least 6 months since they had used systemic corticosteroids, and at least 2 months since using immunomodulators. All the patients were GA naïve. The majority were from eastern Europe.

"We have a small phase II immunologic study," Dr. Khan noted, that pitted 20 mg daily against 40 mg every other day. "There were a lot of advantages of taking it every other day" – fewer injection-site reactions and the like – and "immunologically there was no difference" between the two regimens, he said. The study hasn’t been published yet.

In general, "if you look at just your general clinical observations, you can’t tell" which regimen patients are using, he said.

There’s debate about whether it’s better to start patients on a daily regimen, or if it’s okay to go with less frequent injections right out of the gate.

"You might generate a better Th2 [T-cell] shift if you keep them on every day for a few months, and then alter them. It could be true. The fact is that that sample in a large cohort does not exist. [Either way,] it doesn’t change a whole lot because at 6 months [and] 12 months everybody is doing well," Dr. Khan said.

In the meantime, "many of our patients routinely take [GA] less than every other day. They skip weekends; they create their own regimens," he said.

Teva Pharmaceuticals, the maker of GA, paid for the study. Dr. Khan has received personal compensation and research support from Teva, Biogen-Idec, and other companies.

AT THE 2013 AAN ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: After a year, 40 mg of glatiramer acetate three times a week reduced the annualized MS relapse rate by 34.4% versus placebo (P less than .0001).

Data source: Randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trial in 1,404 relapsing-remitting MS patients

Disclosures: Teva, the maker of GA, paid for the study. Dr. Khan has received personal compensation and research support from Teva, Biogen-Idec, and other companies.

Psychiatric issues to blame when face, hand transplants fail

LAS VEGAS – Transplant surgeons need help from the mental health community to ensure that patients who undergo hand, face, foot, and other non-solid organ transplants succeed psychiatrically, a consultant for transplant teams says.

That’s because all of the patients who have failed those procedures have done so because of psychiatric issues, according to Dr. José R. Maldonado, the psychiatric consultant for six transplant teams at Stanford (Calif.) University. "If you get a new liver, you wake up in the morning, you have a scar in the middle of your belly, that’s it," he said. "You have pain, but you had pain before the transplant."

But getting a new hand, for example, affects patients differently.

"When you wake up in the morning and look down, you see a stitched hand attached to your body," said Dr. Maldonado, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university. "You know that that is not a part of you."

This is the same kind of mental processing that patients must undergo when they get a new face, ear, or other body part. "People have a very hard time accepting that. Those are the patients who have the most significant difficulty adapting to" a transplant, he said.

Some patients stop taking their antirejection drugs and coming to follow-up visits. Others "have gone back to the medical center and requested or demanded that they take the hand off. Some of them have taken a machete and just cut their own hand off," Dr. Maldonado told an audience of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

The issue is of particular concern at Stanford, because the university is establishing its own non-solid organ transplant program, which will join a handful of others across the United States.

Psychiatric problems are not unique to face and hand transplants; mental health issues also bedevil organ transplant patients both before and after the procedure. The worse those problems are, the worse patients tend to do. Depression and anxiety are common, as is guilt about benefiting from the donor’s death. When patients realize that their recovery is going to be difficult and slow, they become demoralized.

Heart and lung transplants seem to be the hardest on patients; some develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Liver and kidney transplants take less of a mental toll.

Immunosuppressives have their own psychiatric side effects, which complicate matters, and nearly all psychiatric medications – antidepressants, neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, and the rest – interfere with their action.

Transplants can be hard on psychiatrists, too, especially when transplant teams call to ask whether patients are good candidates for scarce organs. Given the assumed implications, it can be hard to say no.

But doing so isn’t necessarily a death sentence, Dr. Maldonado said.

He and his team have developed a pretransplant questionnaire called the SIPAT (Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant) to identify good candidates and the weaknesses that make people poor candidates so they can work on them. It’s available free online.

The 18 questions focus on four areas known to affect transplant outcomes: psychosocial support, substance abuse, mental health, and the way in which patients understand and manage their illnesses.

With the feedback, it is possible to design a treatment plan that will make these patients better transplant candidates or refer them to others who can help. That way, when these patients are seen by transplant teams, they have a better chance of being accepted, he said.

Even after rejection, the door isn’t closed forever. "Telling somebody, ‘You don’t make the cut, and unless you make a dramatic change in your life, you will never make the cut’ [will motivate some to] fix their life, come back in 6 months, and say, ‘Doctor, I’m ready. Let’s do it.’ You repeat the [assessment]," and they are now acceptable candidates, he said.

Dr. Maldonado said he had no disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Transplant surgeons need help from the mental health community to ensure that patients who undergo hand, face, foot, and other non-solid organ transplants succeed psychiatrically, a consultant for transplant teams says.

That’s because all of the patients who have failed those procedures have done so because of psychiatric issues, according to Dr. José R. Maldonado, the psychiatric consultant for six transplant teams at Stanford (Calif.) University. "If you get a new liver, you wake up in the morning, you have a scar in the middle of your belly, that’s it," he said. "You have pain, but you had pain before the transplant."

But getting a new hand, for example, affects patients differently.

"When you wake up in the morning and look down, you see a stitched hand attached to your body," said Dr. Maldonado, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the university. "You know that that is not a part of you."

This is the same kind of mental processing that patients must undergo when they get a new face, ear, or other body part. "People have a very hard time accepting that. Those are the patients who have the most significant difficulty adapting to" a transplant, he said.

Some patients stop taking their antirejection drugs and coming to follow-up visits. Others "have gone back to the medical center and requested or demanded that they take the hand off. Some of them have taken a machete and just cut their own hand off," Dr. Maldonado told an audience of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

The issue is of particular concern at Stanford, because the university is establishing its own non-solid organ transplant program, which will join a handful of others across the United States.

Psychiatric problems are not unique to face and hand transplants; mental health issues also bedevil organ transplant patients both before and after the procedure. The worse those problems are, the worse patients tend to do. Depression and anxiety are common, as is guilt about benefiting from the donor’s death. When patients realize that their recovery is going to be difficult and slow, they become demoralized.

Heart and lung transplants seem to be the hardest on patients; some develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Liver and kidney transplants take less of a mental toll.

Immunosuppressives have their own psychiatric side effects, which complicate matters, and nearly all psychiatric medications – antidepressants, neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, and the rest – interfere with their action.

Transplants can be hard on psychiatrists, too, especially when transplant teams call to ask whether patients are good candidates for scarce organs. Given the assumed implications, it can be hard to say no.

But doing so isn’t necessarily a death sentence, Dr. Maldonado said.

He and his team have developed a pretransplant questionnaire called the SIPAT (Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant) to identify good candidates and the weaknesses that make people poor candidates so they can work on them. It’s available free online.

The 18 questions focus on four areas known to affect transplant outcomes: psychosocial support, substance abuse, mental health, and the way in which patients understand and manage their illnesses.

With the feedback, it is possible to design a treatment plan that will make these patients better transplant candidates or refer them to others who can help. That way, when these patients are seen by transplant teams, they have a better chance of being accepted, he said.