User login

Differences in COVID-19 Outcomes Among Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: First vs Later Surges

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

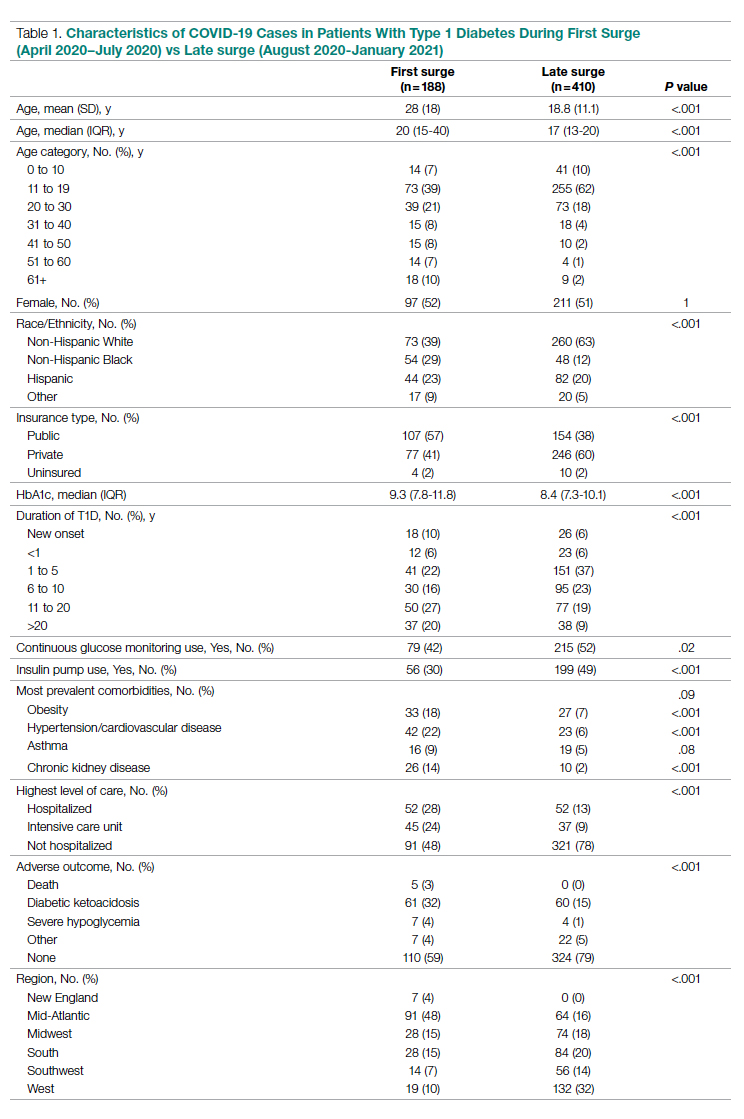

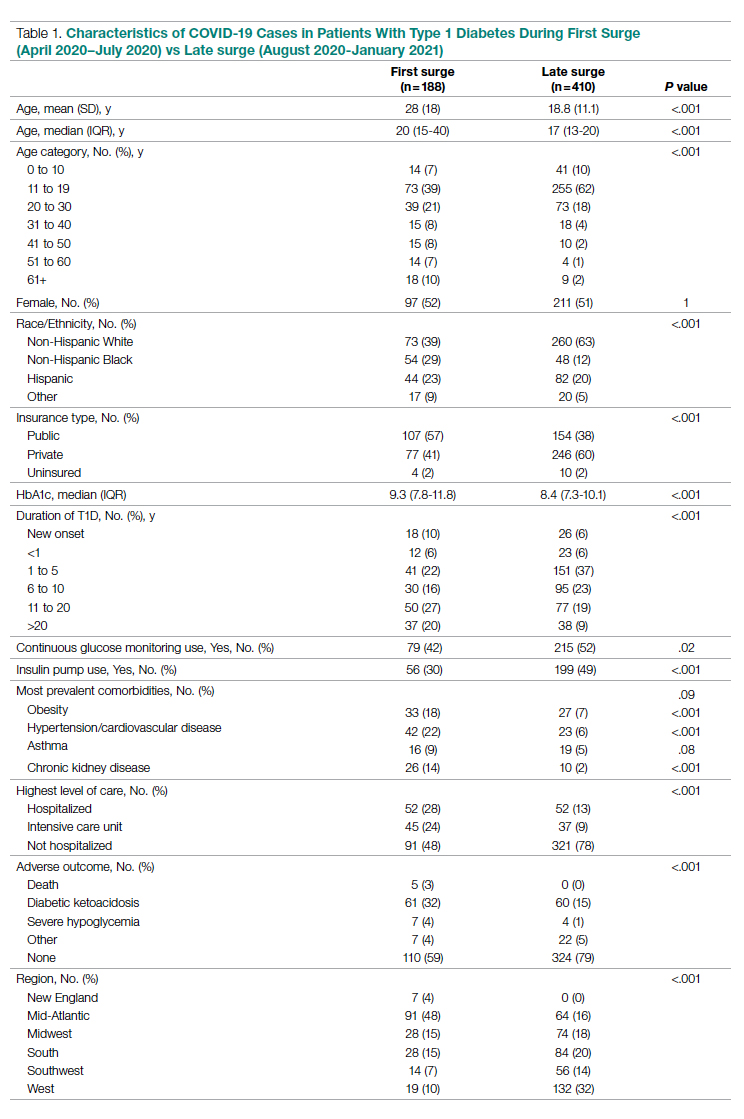

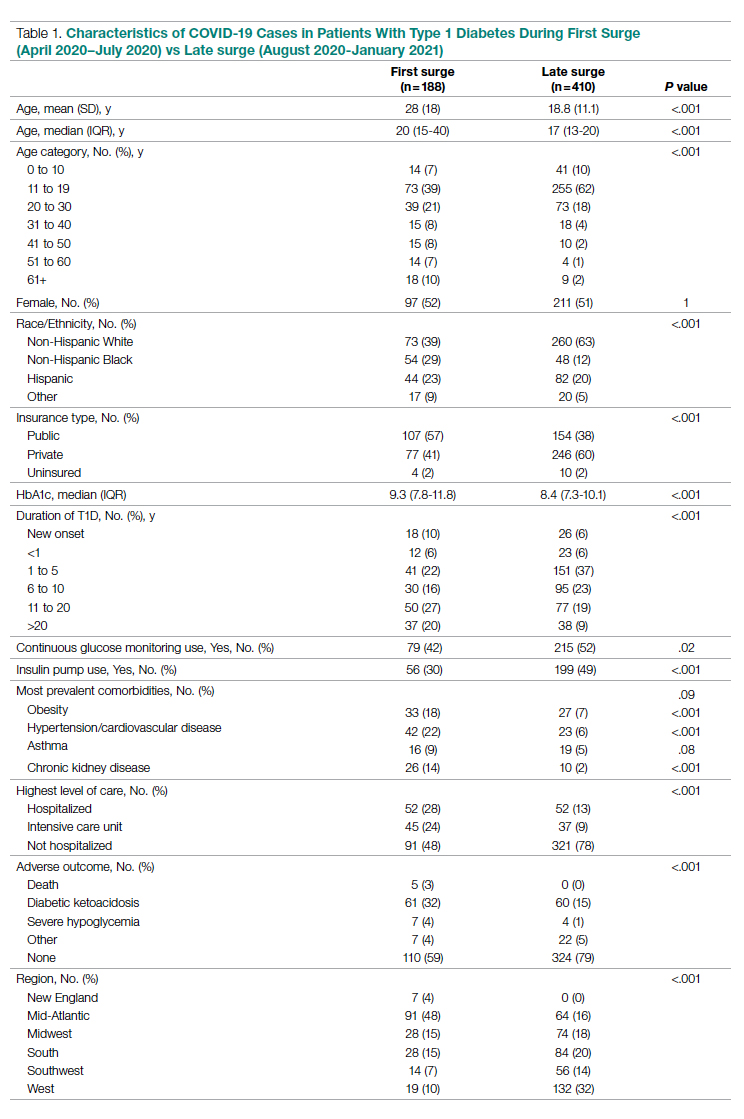

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

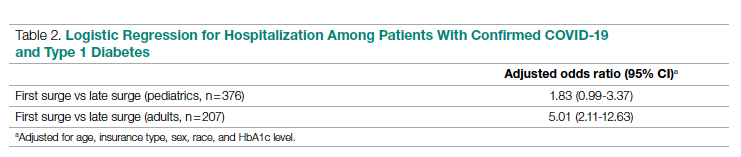

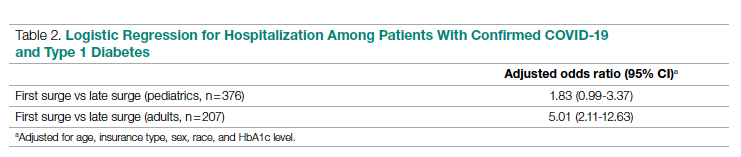

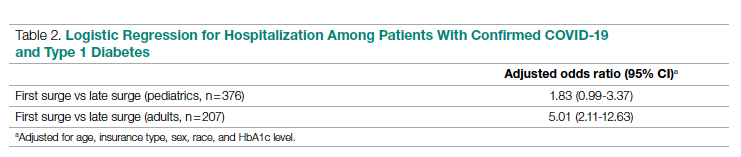

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

From Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr Gallagher), T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Saketh Rompicherla; Drs Ebekozien, Noor, Odugbesan, and Mungmode; Nicole Rioles, Emma Ospelt), University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Drs. Wilkes, O’Malley, and Rapaport), Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY (Drs. Antal and Feuer), NYU Long Island School of Medicine, Mineola, NY (Dr. Gabriel), NYU Langone Health, New York, NY (Dr. Golden), Barbara Davis Center, Aurora, CO (Dr. Alonso), Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Dr. Lyons), Stanford University, Stanford, CA (Dr. Prahalad), Children Mercy Kansas City, MO (Dr. Clements), Indiana University School of Medicine, IN (Dr. Neyman), Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego, CA (Dr. Demeterco-Berggren).

Background: Patient outcomes of COVID-19 have improved throughout the pandemic. However, because it is not known whether outcomes of COVID-19 in the type 1 diabetes (T1D) population improved over time, we investigated differences in COVID-19 outcomes for patients with T1D in the United States.

Methods: We analyzed data collected via a registry of patients with T1D and COVID-19 from 56 sites between April 2020 and January 2021. We grouped cases into first surge (April 9, 2020, to July 31, 2020, n = 188) and late surge (August 1, 2020, to January 31, 2021, n = 410), and then compared outcomes between both groups using descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

Results: Adverse outcomes were more frequent during the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (32% vs 15%, P < .001), severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04), and hospitalization (52% vs 22%, P < .001). Patients in the first surge were older (28 [SD,18.8] years vs 18.0 [SD, 11.1] years, P < .001), had higher median hemoglobin A1c levels (9.3 [interquartile range {IQR}, 4.0] vs 8.4 (IQR, 2.8), P < .001), and were more likely to use public insurance (107 [57%] vs 154 [38%], P < .001). The odds of hospitalization for adults in the first surge were 5 times higher compared to the late surge (odds ratio, 5.01; 95% CI, 2.11-12.63).

Conclusion: Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge had a higher proportion of adverse outcomes than those who presented in a later surge.

Keywords: TD1, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia.

After the World Health Organization declared the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified patients with diabetes as high risk for severe illness.1-7 The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 has significantly improved over the past 2 years. Public health measures, less severe COVID-19 variants, increased access to testing, and new treatments for COVID-19 have contributed to improved outcomes.

The T1D Exchange has previously published findings on COVID-19 outcomes for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using data from the T1D COVID-19 Surveillance Registry.8-12 Given improved outcomes in COVID-19 in the general population, we sought to determine if outcomes for cases of COVID-19 reported to this registry changed over time.

Methods

This study was coordinated by the T1D Exchange and approved as nonhuman subject research by the Western Institutional Review Board. All participating centers also obtained local institutional review board approval. No identifiable patient information was collected as part of this noninterventional, cross-sectional study.

The T1D Exchange Multi-center COVID-19 Surveillance Study collected data from endocrinology clinics that completed a retrospective chart review and submitted information to T1D Exchange via an online questionnaire for all patients with T1D at their sites who tested positive for COVID-19.13,14 The questionnaire was administered using the Qualtrics survey platform (www.qualtrics.com version XM) and contained 33 pre-coded and free-text response fields to collect patient and clinical attributes.

Each participating center identified 1 team member for reporting to avoid duplicate case submission. Each submitted case was reviewed for potential errors and incomplete information. The coordinating center verified the number of cases per site for data quality assurance.

Quantitative data were represented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). Categorical data were described as the number (percentage) of patients. Summary statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, were calculated for all patient-related and clinical characteristics. The date August 1, 2021, was selected as the end of the first surge based on a review of national COVID-19 surges.

We used the Fisher’s exact test to assess associations between hospitalization and demographics, HbA1c, diabetes duration, symptoms, and adverse outcomes. In addition, multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between time of surge and hospitalization separately for both the pediatric and adult populations. Each model was adjusted for potential sociodemographic confounders, specifically age, sex, race, insurance, and HbA1c.

All tests were 2-sided, with type 1 error set at 5%. Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were performed using statistical software R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

The characteristics of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D that were reported early in the pandemic, before August 1, 2020 (first surge), compared with those of cases reported on and after August 1, 2020 (later surges) are shown in Table 1.

Patients with T1D who presented with COVID-19 during the first surge as compared to the later surges were older (mean age 28 [SD, 18.0] years vs 18.8 [SD, 11.1] years; P < .001) and had a longer duration of diabetes (P < .001). The first-surge group also had more patients with >20 years’ diabetes duration (20% vs 9%, P < .001). Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease were also more commonly reported in first-surge cases (all P < .001).

There was a significant difference in race and ethnicity reported in the first surge vs the later surge cases, with fewer patients identifying as non-Hispanic White (39% vs, 63%, P < .001) and more patients identifying as non-Hispanic Black (29% vs 12%, P < .001). The groups also differed significantly in terms of insurance type, with more people on public insurance in the first-surge group (57% vs 38%, P < .001). In addition, median HbA1c was higher (9.3% vs 8.4%, P < .001) and continuous glucose monitor and insulin pump use were less common (P = .02 and <.001, respectively) in the early surge.

All symptoms and adverse outcomes were reported more often in the first surge, including diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA; 32% vs 15%; P < .001) and severe hypoglycemia (4% vs 1%, P = .04). Hospitalization (52% vs 13%, P < .001) and ICU admission (24% vs 9%, P < .001) were reported more often in the first-surge group.

Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of logistic regression analyses for hospitalization in the pediatric (≤19 years of age) and adult (>19 years of age) groups, along with the odds of hospitalization during the first vs late surge among COVID-positive people with T1D. Adult patients who tested positive in the first surge were about 5 times more likely to be hospitalized than adults who tested positive for infection in the late surge after adjusting for age, insurance type, sex, race, and HbA1c levels. Pediatric patients also had an increased odds for hospitalization during the first surge, but this increase was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our analysis of COVID-19 cases in patients with T1D reported by diabetes providers across the United States found that adverse outcomes were more prevalent early in the pandemic. There may be a number of reasons for this difference in outcomes between patients who presented in the first surge vs a later surge. First, because testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited and reserved for hospitalized patients early in the pandemic, the first-surge patients with confirmed COVID-19 likely represent a skewed population of higher-acuity patients. This may also explain the relative paucity of cases in younger patients reported early in the pandemic. Second, worse outcomes in the early surge may also have been associated with overwhelmed hospitals in New York City at the start of the outbreak. According to Cummings et al, the abrupt surge of critically ill patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome initially outpaced their capacity to provide prone-positioning ventilation, which has been expanded since then.15 While there was very little hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease reported in the pediatric groups, there was a higher prevalence of obesity in the pediatric group from the mid-Atlantic region. Obesity has been associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19 illness in children.16 Finally, there were 5 deaths reported in this study, all of which were reported during the first surge. Older age and increased rates of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in the first surge cases likely contributed to worse outcomes for adults in mid-Atlantic region relative to the other regions. Minority race and the use of public insurance, risk factors for more severe outcomes in all regions, were also more common in cases reported from the mid-Atlantic region.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study that relies upon voluntary provider reports. Second, availability of COVID-19 testing was limited in all regions in spring 2020. Third, different regions of the country experienced subsequent surges at different times within the reported timeframes in this analysis. Fourth, this report time period does not include the impact of the newer COVID-19 variants. Finally, trends in COVID-19 outcomes were affected by the evolution of care that developed throughout 2020.

Conclusion

Adult patients with T1D and COVID-19 who reported during the first surge had about 5 times higher hospitalization odds than those who presented in a later surge.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, MPH, 11 Avenue de Lafayette, Boston, MA 02111; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Ebekozien reports receiving research grants from Medtronic Diabetes, Eli Lilly, and Dexcom, and receiving honoraria from Medtronic Diabetes.

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):813-822. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2

2. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Asuni A, Jolly Y, Hessler D. The early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34(12):107748. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107748

3. Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(10):823-833. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0

4. Wargny M, Gourdy P, Ludwig L, et al. Type 1 diabetes in people hospitalized for COVID-19: new insights from the CORONADO study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(11):e174-e177. doi:10.2337/dc20-1217

5. Gregory JM, Slaughter JC, Duffus SH, et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):526-532. doi:10.2337/dc20-2260

6. Cardona-Hernandez R, Cherubini V, Iafusco D, Schiaffini R, Luo X, Maahs DM. Children and youth with diabetes are not at increased risk for hospitalization due to COVID-19. Pediatr Diabetes. 2021;22(2):202-206. doi:10.1111/pedi.13158

7. Maahs DM, Alonso GT, Gallagher MP, Ebekozien O. Comment on Gregory et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: a prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:526-532. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):e102. doi:10.2337/dc20-3119

8. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the US. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):e83-e85. doi:10.2337/dc20-1088

9. Beliard K, Ebekozien O, Demeterco-Berggren C, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13(3):270-272. doi:10.1111/1753-0407

10. O’Malley G, Ebekozien O, Desimone M, et al. COVID-19 hospitalization in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange Multicenter Surveillance study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e936-e942. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa825

11. Ebekozien O, Agarwal S, Noor N, et al. Inequities in diabetic ketoacidosis among patients with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: data from 52 US clinical centers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(4):e1755-e1762. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa920

12. Alonso GT, Ebekozien O, Gallagher MP, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis drives COVID-19 related hospitalizations in children with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2021;13(8):681-687. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13184

13. Noor N, Ebekozien O, Levin L, et al. Diabetes technology use for management of type 1 diabetes is associated with fewer adverse COVID-19 outcomes: findings from the T1D Exchange COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(8):e160-e162. doi:10.2337/dc21-0074

14. Demeterco-Berggren C, Ebekozien O, Rompicherla S, et al. Age and hospitalization risk in people with type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: Data from the T1D Exchange Surveillance Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;dgab668. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab668

15. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

16. Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:246-256. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163

1.11 Common Clinical Diagnoses and Conditions: Diabetes Mellitus

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, a disorder of glucose homeostasis, is increasing in incidence and prevalence in pediatrics. Although there has been a significant rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes, particularly among adolescents in high-risk ethnic groups, type 1 diabetes is still the most common form of diabetes in the pediatric and adolescent populations. The increase in obesity in the general population and the propensity of adolescents with type 2 diabetes to develop ketosis has resulted in phenotypic overlap in the pediatric patient presenting with a new diagnosis. In addition to the medical complications associated with these chronic conditions, both forms of diabetes have profound social and emotional impacts on the child. Pediatric hospitalists frequently encounter both children with new-onset diabetes and children previously diagnosed who may require hospitalization because of a diabetes related complication, an unrelated condition, or an elective procedure. Pediatric hospitalists are often positioned to provide both immediate care for children with diabetes as well as to coordinate care across multiple specialties when indicated.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Compare and contrast the epidemiology and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, attending to differences in family history, impairment of glucose regulation, and occurrence of ketoacidosis.

- Discuss the potential short and long-term complications of poor glucose control, including end-organ damage, and describe methods to assess for these complications.

- Describe common comorbidities and polyendocrinopathies associated with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the role of obesity in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

- List other common causes of hyperglycemia, such as stress, drug, or steroid-induced hyperglycemia and indicate when insulin administration is needed.

- Explain the critical role of glucose homeostasis for patients admitted for reasons unrelated to their diagnosis of diabetes.

- List and interpret the laboratory tests, including islet autoantibodies and hemoglobin A1c, used to classify diabetes type and assess glycemic control.

- List the type and appropriate timing of screening tests for complications and co-morbidities of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the different formulations of insulin and the different systems for insulin delivery and glucose monitoring.

- Describe the expected patterns of post-prandial glucose excursion in patients with diabetes and identify when a change in management is needed based on these patterns.

- Compare and contrast the role of nutrition in the management of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes.

- Review the principles of carbohydrate counting.

- Compare and contrast glucose monitoring, dietary recommendations, insulin dosing, and glucose targets between populations (such as type 1, type 2, cystic fibrosis related diabetes, and others).

- Define diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and describe its initial management, attending to fluid delivery, electrolyte and acid-base monitoring, mental status assessments, and appropriate patient placement based on local context.

- Discuss potential complications that may result from treatment of diabetes and DKA, including hypoglycemia and electrolyte imbalances.

- Summarize the approach toward management and education after stabilization of DKA.

- Describe criteria for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical improvement, education for patients and the family/caregivers, and establishment of a coordinated longitudinal care plan.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Diagnose diabetes and its complications by efficiently performing a history and physical examination, determining if the patient meets diagnostic criteria.

- Identify and treat underlying causes of increased insulin demand that may lead to DKA in the patient with known diabetes.

- Order appropriate diagnostic testing for patients with new onset diabetes, diabetes exacerbations, or secondary causes of hyperglycemia.

- Order insulin doses and delivery systems (such as intravenous infusion, subcutaneous injection, and others) and other classes of drugs used in the treatment of diabetes.

- Identify and manage both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia with attention to complications that may arise during treatment.

- Identify changes in clinical status related to severe acidosis and fluid and electrolyte disturbances and promptly initiate appropriate actions, including transfer to a higher level of care when indicated.

- Obtain prompt consultation with an endocrinologist or other subspecialist as appropriate.

- Utilize available support services, such as a certified diabetes educator, social worker, child life specialist, registered dietitian, and others, to ensure a comprehensive approach to management.

- Coordinate care and education for patients and the family/caregivers with other healthcare providers.

- Coordinate care with subspecialists and the primary care provider and arrange an appropriate transition plan for hospital discharge.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Realize the importance of effective communication and culturally responsive care when creating a diabetes management plan, maintaining awareness of the unique needs of various groups.

- Recognize that acute and chronic psychosocial factors that impact the ability of patients and the family/caregivers to manage diabetes appropriately.

- Recognize the importance of the multidisciplinary team approach in the management of diabetes in children, including involvement of the primary care provider, endocrinologist, diabetes educator, dietitian, social worker, psychologist, child life specialist, and school representative.

- Acknowledge the value of collaboration with subspecialists and the primary care provider to ensure coordinated longitudinal care for children with diabetes.

- Maintain awareness of local populations and their risk factors for diabetes.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development and implementation of cost-effective, safe, evidence-based care pathways to standardize the evaluation and management for hospitalized children with diabetes.

- Work with hospital administration, hospital staff, subspecialists, and community organizations to effect system-wide processes to improve the transition of care from hospital to the ambulatory setting.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in system-wide processes within the hospital to promote therapeutic safety and vigilance in the use of hypoglycemic agents.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in educational events to promote awareness of and familiarity with national guidelines for management strategies, new therapeutic and pharmacologic agents, and the use of medical devices to improve and monitor glucose homeostasis.

1. American Diabetes Association. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2019. Diabetes Care.2019;42(Supplement 1):S148-S164. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S013.

2. Rosenbloom AL. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther. 2010;1(2):103-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-010-0008-2.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, a disorder of glucose homeostasis, is increasing in incidence and prevalence in pediatrics. Although there has been a significant rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes, particularly among adolescents in high-risk ethnic groups, type 1 diabetes is still the most common form of diabetes in the pediatric and adolescent populations. The increase in obesity in the general population and the propensity of adolescents with type 2 diabetes to develop ketosis has resulted in phenotypic overlap in the pediatric patient presenting with a new diagnosis. In addition to the medical complications associated with these chronic conditions, both forms of diabetes have profound social and emotional impacts on the child. Pediatric hospitalists frequently encounter both children with new-onset diabetes and children previously diagnosed who may require hospitalization because of a diabetes related complication, an unrelated condition, or an elective procedure. Pediatric hospitalists are often positioned to provide both immediate care for children with diabetes as well as to coordinate care across multiple specialties when indicated.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Compare and contrast the epidemiology and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, attending to differences in family history, impairment of glucose regulation, and occurrence of ketoacidosis.

- Discuss the potential short and long-term complications of poor glucose control, including end-organ damage, and describe methods to assess for these complications.

- Describe common comorbidities and polyendocrinopathies associated with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the role of obesity in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

- List other common causes of hyperglycemia, such as stress, drug, or steroid-induced hyperglycemia and indicate when insulin administration is needed.

- Explain the critical role of glucose homeostasis for patients admitted for reasons unrelated to their diagnosis of diabetes.

- List and interpret the laboratory tests, including islet autoantibodies and hemoglobin A1c, used to classify diabetes type and assess glycemic control.

- List the type and appropriate timing of screening tests for complications and co-morbidities of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the different formulations of insulin and the different systems for insulin delivery and glucose monitoring.

- Describe the expected patterns of post-prandial glucose excursion in patients with diabetes and identify when a change in management is needed based on these patterns.

- Compare and contrast the role of nutrition in the management of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes.

- Review the principles of carbohydrate counting.

- Compare and contrast glucose monitoring, dietary recommendations, insulin dosing, and glucose targets between populations (such as type 1, type 2, cystic fibrosis related diabetes, and others).

- Define diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and describe its initial management, attending to fluid delivery, electrolyte and acid-base monitoring, mental status assessments, and appropriate patient placement based on local context.

- Discuss potential complications that may result from treatment of diabetes and DKA, including hypoglycemia and electrolyte imbalances.

- Summarize the approach toward management and education after stabilization of DKA.

- Describe criteria for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical improvement, education for patients and the family/caregivers, and establishment of a coordinated longitudinal care plan.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Diagnose diabetes and its complications by efficiently performing a history and physical examination, determining if the patient meets diagnostic criteria.

- Identify and treat underlying causes of increased insulin demand that may lead to DKA in the patient with known diabetes.

- Order appropriate diagnostic testing for patients with new onset diabetes, diabetes exacerbations, or secondary causes of hyperglycemia.

- Order insulin doses and delivery systems (such as intravenous infusion, subcutaneous injection, and others) and other classes of drugs used in the treatment of diabetes.

- Identify and manage both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia with attention to complications that may arise during treatment.

- Identify changes in clinical status related to severe acidosis and fluid and electrolyte disturbances and promptly initiate appropriate actions, including transfer to a higher level of care when indicated.

- Obtain prompt consultation with an endocrinologist or other subspecialist as appropriate.

- Utilize available support services, such as a certified diabetes educator, social worker, child life specialist, registered dietitian, and others, to ensure a comprehensive approach to management.

- Coordinate care and education for patients and the family/caregivers with other healthcare providers.

- Coordinate care with subspecialists and the primary care provider and arrange an appropriate transition plan for hospital discharge.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Realize the importance of effective communication and culturally responsive care when creating a diabetes management plan, maintaining awareness of the unique needs of various groups.

- Recognize that acute and chronic psychosocial factors that impact the ability of patients and the family/caregivers to manage diabetes appropriately.

- Recognize the importance of the multidisciplinary team approach in the management of diabetes in children, including involvement of the primary care provider, endocrinologist, diabetes educator, dietitian, social worker, psychologist, child life specialist, and school representative.

- Acknowledge the value of collaboration with subspecialists and the primary care provider to ensure coordinated longitudinal care for children with diabetes.

- Maintain awareness of local populations and their risk factors for diabetes.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development and implementation of cost-effective, safe, evidence-based care pathways to standardize the evaluation and management for hospitalized children with diabetes.

- Work with hospital administration, hospital staff, subspecialists, and community organizations to effect system-wide processes to improve the transition of care from hospital to the ambulatory setting.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in system-wide processes within the hospital to promote therapeutic safety and vigilance in the use of hypoglycemic agents.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in educational events to promote awareness of and familiarity with national guidelines for management strategies, new therapeutic and pharmacologic agents, and the use of medical devices to improve and monitor glucose homeostasis.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, a disorder of glucose homeostasis, is increasing in incidence and prevalence in pediatrics. Although there has been a significant rise in the incidence of type 2 diabetes, particularly among adolescents in high-risk ethnic groups, type 1 diabetes is still the most common form of diabetes in the pediatric and adolescent populations. The increase in obesity in the general population and the propensity of adolescents with type 2 diabetes to develop ketosis has resulted in phenotypic overlap in the pediatric patient presenting with a new diagnosis. In addition to the medical complications associated with these chronic conditions, both forms of diabetes have profound social and emotional impacts on the child. Pediatric hospitalists frequently encounter both children with new-onset diabetes and children previously diagnosed who may require hospitalization because of a diabetes related complication, an unrelated condition, or an elective procedure. Pediatric hospitalists are often positioned to provide both immediate care for children with diabetes as well as to coordinate care across multiple specialties when indicated.

Knowledge

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Compare and contrast the epidemiology and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, attending to differences in family history, impairment of glucose regulation, and occurrence of ketoacidosis.

- Discuss the potential short and long-term complications of poor glucose control, including end-organ damage, and describe methods to assess for these complications.

- Describe common comorbidities and polyendocrinopathies associated with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the role of obesity in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

- List other common causes of hyperglycemia, such as stress, drug, or steroid-induced hyperglycemia and indicate when insulin administration is needed.

- Explain the critical role of glucose homeostasis for patients admitted for reasons unrelated to their diagnosis of diabetes.

- List and interpret the laboratory tests, including islet autoantibodies and hemoglobin A1c, used to classify diabetes type and assess glycemic control.

- List the type and appropriate timing of screening tests for complications and co-morbidities of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

- Describe the different formulations of insulin and the different systems for insulin delivery and glucose monitoring.

- Describe the expected patterns of post-prandial glucose excursion in patients with diabetes and identify when a change in management is needed based on these patterns.

- Compare and contrast the role of nutrition in the management of type 1 versus type 2 diabetes.

- Review the principles of carbohydrate counting.

- Compare and contrast glucose monitoring, dietary recommendations, insulin dosing, and glucose targets between populations (such as type 1, type 2, cystic fibrosis related diabetes, and others).

- Define diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and describe its initial management, attending to fluid delivery, electrolyte and acid-base monitoring, mental status assessments, and appropriate patient placement based on local context.

- Discuss potential complications that may result from treatment of diabetes and DKA, including hypoglycemia and electrolyte imbalances.

- Summarize the approach toward management and education after stabilization of DKA.

- Describe criteria for hospital discharge, including specific measures of clinical improvement, education for patients and the family/caregivers, and establishment of a coordinated longitudinal care plan.

Skills

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Diagnose diabetes and its complications by efficiently performing a history and physical examination, determining if the patient meets diagnostic criteria.

- Identify and treat underlying causes of increased insulin demand that may lead to DKA in the patient with known diabetes.

- Order appropriate diagnostic testing for patients with new onset diabetes, diabetes exacerbations, or secondary causes of hyperglycemia.

- Order insulin doses and delivery systems (such as intravenous infusion, subcutaneous injection, and others) and other classes of drugs used in the treatment of diabetes.

- Identify and manage both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia with attention to complications that may arise during treatment.

- Identify changes in clinical status related to severe acidosis and fluid and electrolyte disturbances and promptly initiate appropriate actions, including transfer to a higher level of care when indicated.

- Obtain prompt consultation with an endocrinologist or other subspecialist as appropriate.

- Utilize available support services, such as a certified diabetes educator, social worker, child life specialist, registered dietitian, and others, to ensure a comprehensive approach to management.

- Coordinate care and education for patients and the family/caregivers with other healthcare providers.

- Coordinate care with subspecialists and the primary care provider and arrange an appropriate transition plan for hospital discharge.

Attitudes

Pediatric hospitalists should be able to:

- Realize the importance of effective communication and culturally responsive care when creating a diabetes management plan, maintaining awareness of the unique needs of various groups.

- Recognize that acute and chronic psychosocial factors that impact the ability of patients and the family/caregivers to manage diabetes appropriately.

- Recognize the importance of the multidisciplinary team approach in the management of diabetes in children, including involvement of the primary care provider, endocrinologist, diabetes educator, dietitian, social worker, psychologist, child life specialist, and school representative.

- Acknowledge the value of collaboration with subspecialists and the primary care provider to ensure coordinated longitudinal care for children with diabetes.

- Maintain awareness of local populations and their risk factors for diabetes.

Systems Organization and Improvement

In order to improve efficiency and quality within their organizations, pediatric hospitalists should:

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in the development and implementation of cost-effective, safe, evidence-based care pathways to standardize the evaluation and management for hospitalized children with diabetes.

- Work with hospital administration, hospital staff, subspecialists, and community organizations to effect system-wide processes to improve the transition of care from hospital to the ambulatory setting.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in system-wide processes within the hospital to promote therapeutic safety and vigilance in the use of hypoglycemic agents.

- Lead, coordinate, or participate in educational events to promote awareness of and familiarity with national guidelines for management strategies, new therapeutic and pharmacologic agents, and the use of medical devices to improve and monitor glucose homeostasis.

1. American Diabetes Association. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2019. Diabetes Care.2019;42(Supplement 1):S148-S164. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S013.

2. Rosenbloom AL. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther. 2010;1(2):103-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-010-0008-2.

1. American Diabetes Association. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2019. Diabetes Care.2019;42(Supplement 1):S148-S164. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S013.

2. Rosenbloom AL. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther. 2010;1(2):103-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-010-0008-2.