User login

The hospitalist as intensivist

Clinical question: What roles, training, and support do hospitalists have and perceive in the intensive care unit?

Background: There is a well-documented shortage of intensivists in the United States, which has left hospitalists to help fill the gap of care. Hospitalists, however, have varied levels of critical care knowledge and skills. In some regions, more than 80% of hospitalists deliver care in the ICU. It is unknown how much support hospitalized patients receive from board-certified critical care physicians.

Study design: Multistage cross-section survey.

Setting: Web-based survey initially sent through the Critical Care Task Force professional networks and later sent to 4,000 hospitalists randomly selected from Society of Hospital Medicine’s national electronic mailing list of 12,000 hospitalists.

Synopsis: This study includes 425 responses, approximately 10% of those solicited. Compared with the annual SHM survey, this included more hospitalists from academic hospitals (24% vs. 14.8%) and fewer from nonteaching hospitals (41% vs. 58.7%). A total of 77% of responders provide care in the ICU, with 66% serving as the attending physician.

Rural and nonacademic hospitalists are more prevalent in the ICU (96% rural vs. 73% nonrural; 90% nonacademic vs. 67% academic), are more likely to serve as the primary physician for all or most ICU patients (85% rural vs. 62% nonrural; 81% nonacademic vs. 44% academic), and provide all critical care services (55% rural vs. 10% nonrural; 64% nonacademic vs. 25% academic).

Many rural (43%) and nonacademic (42%) hospitalists feel that they are expected to practice beyond their perceived scope of expertise at least some of the time, which was correlated with perceived difficulty in transferring patients to higher levels of care. About 90% of rural hospitalists report at least insufficient support from board-certified intensivists. Of all responders in the study, 85% indicated interest in additional critical care training in some form, short of fellowship training.

Bottom line: Most hospitalists provide care in the ICU, however hospitalists provide critical care at significantly higher rates in rural and nonacademic hospital settings. This care is being provided with a perceived lack of intensivist support and training.

Citation: Sweigart JR et al. Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):6-12.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What roles, training, and support do hospitalists have and perceive in the intensive care unit?

Background: There is a well-documented shortage of intensivists in the United States, which has left hospitalists to help fill the gap of care. Hospitalists, however, have varied levels of critical care knowledge and skills. In some regions, more than 80% of hospitalists deliver care in the ICU. It is unknown how much support hospitalized patients receive from board-certified critical care physicians.

Study design: Multistage cross-section survey.

Setting: Web-based survey initially sent through the Critical Care Task Force professional networks and later sent to 4,000 hospitalists randomly selected from Society of Hospital Medicine’s national electronic mailing list of 12,000 hospitalists.

Synopsis: This study includes 425 responses, approximately 10% of those solicited. Compared with the annual SHM survey, this included more hospitalists from academic hospitals (24% vs. 14.8%) and fewer from nonteaching hospitals (41% vs. 58.7%). A total of 77% of responders provide care in the ICU, with 66% serving as the attending physician.

Rural and nonacademic hospitalists are more prevalent in the ICU (96% rural vs. 73% nonrural; 90% nonacademic vs. 67% academic), are more likely to serve as the primary physician for all or most ICU patients (85% rural vs. 62% nonrural; 81% nonacademic vs. 44% academic), and provide all critical care services (55% rural vs. 10% nonrural; 64% nonacademic vs. 25% academic).

Many rural (43%) and nonacademic (42%) hospitalists feel that they are expected to practice beyond their perceived scope of expertise at least some of the time, which was correlated with perceived difficulty in transferring patients to higher levels of care. About 90% of rural hospitalists report at least insufficient support from board-certified intensivists. Of all responders in the study, 85% indicated interest in additional critical care training in some form, short of fellowship training.

Bottom line: Most hospitalists provide care in the ICU, however hospitalists provide critical care at significantly higher rates in rural and nonacademic hospital settings. This care is being provided with a perceived lack of intensivist support and training.

Citation: Sweigart JR et al. Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):6-12.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What roles, training, and support do hospitalists have and perceive in the intensive care unit?

Background: There is a well-documented shortage of intensivists in the United States, which has left hospitalists to help fill the gap of care. Hospitalists, however, have varied levels of critical care knowledge and skills. In some regions, more than 80% of hospitalists deliver care in the ICU. It is unknown how much support hospitalized patients receive from board-certified critical care physicians.

Study design: Multistage cross-section survey.

Setting: Web-based survey initially sent through the Critical Care Task Force professional networks and later sent to 4,000 hospitalists randomly selected from Society of Hospital Medicine’s national electronic mailing list of 12,000 hospitalists.

Synopsis: This study includes 425 responses, approximately 10% of those solicited. Compared with the annual SHM survey, this included more hospitalists from academic hospitals (24% vs. 14.8%) and fewer from nonteaching hospitals (41% vs. 58.7%). A total of 77% of responders provide care in the ICU, with 66% serving as the attending physician.

Rural and nonacademic hospitalists are more prevalent in the ICU (96% rural vs. 73% nonrural; 90% nonacademic vs. 67% academic), are more likely to serve as the primary physician for all or most ICU patients (85% rural vs. 62% nonrural; 81% nonacademic vs. 44% academic), and provide all critical care services (55% rural vs. 10% nonrural; 64% nonacademic vs. 25% academic).

Many rural (43%) and nonacademic (42%) hospitalists feel that they are expected to practice beyond their perceived scope of expertise at least some of the time, which was correlated with perceived difficulty in transferring patients to higher levels of care. About 90% of rural hospitalists report at least insufficient support from board-certified intensivists. Of all responders in the study, 85% indicated interest in additional critical care training in some form, short of fellowship training.

Bottom line: Most hospitalists provide care in the ICU, however hospitalists provide critical care at significantly higher rates in rural and nonacademic hospital settings. This care is being provided with a perceived lack of intensivist support and training.

Citation: Sweigart JR et al. Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):6-12.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Guidelines to optimize treatment of reduced ejection fraction heart failure

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: What guidance is there for clinical care of complex heart failure patients?

Background: The prevalence of heart failure (HF)is escalating and consumes significant health care resources, inflicts significant morbidity and mortality, and greatly affects quality of life. There is a plethora of research, multiple medical therapies, devices, and care strategies that have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients. Previous publications have reviewed evidence-based literature but left a gap in knowledge for those more-complex areas or lacked practical clinical guidance. This policy document was created to guide physicians in informed decision making in a directed decision pathway form.

Study design: Expert consensus guidelines.

Setting: American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary group of specialties including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, epidemiologists, and patient advocacy groups addressed 10 pivotal issues in heart failure through literature review, expert consensus, and round table discussion.

Ten principles were identified and addressed:

- Initiating, adding, or switching to new evidenced-based guideline-directed therapy.

- Achieving optimal therapy using multiple HF drugs and therapies.

- Knowing when to refer a patient to an HF specialist.

- Addressing the challenges of care coordination for team-based HF treatment.

- Improving patient adherence.

- Managing specific patient cohorts, such as African Americans, older adults, and the frail.

- Managing your patients’ cost of care for HF.

- Reducing costs and managing the increased complexity of HF.

- Managing the most common cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities.

- Integrating palliative care and transitioning patients to hospice care

Bottom line: Structured guidelines to provide practical and actionable recommendations to improve heart failure outcomes, integrate evidence-based medicine when available, and utilize expert conscious when evidence-based medicine is not available.

Citation: Yancy CW et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus on decision pathway for optimizing of heart failure treatment: Answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):201-30.

Dr. Muñoa is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Emergency Imaging: Femoral Pseudoaneurysm

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

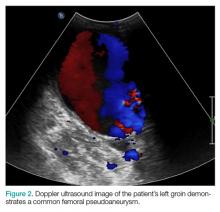

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

Case

An 84-year-old man, who was a resident at a local nursing home, presented for evaluation after the nursing staff noticed an increasingly swollen mass on the patient’s left groin. The patient’s medical history was significant for bilateral aortofemoral graft surgery, dementia, hypertension, and severe peripheral artery disease (PAD). He was not on any anticoagulation or antiplatelet agents. Due to the patient’s dementia, he was unable to provide a history regarding the onset of the swelling or any other signs or symptoms.

On examination, the patient did not appear in distress. His son, who was the patient’s durable power of attorney, was likewise unable to provide a clear timeframe regarding onset of the mass. The patient had no recent history of trauma and had not undergone any recent medical procedures. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 110/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 13 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air.

Clinical examination revealed a pulsatile, purple left groin mass and bruit. The mass was located around the left inguinal ligament and extended down the proximal, inner thigh (Figure 1). There was no drainage or lesions from the mass. Inspection of the patient’s hip demonstrated decreased adduction, limited by the mass; otherwise, there was normal range of motion. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were equal and intact, and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

The patient tolerated the examination without focal signs of discomfort. A Doppler ultrasound revealed findings consistent with a common femoral pseudoaneurysm (PSA) (Figure 2). For better visualization and extension, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained, which demonstrated a PSA measuring 11.7 x 10.7 x 7.3 cm; there was no active extravasation (Figure 3).

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline while vascular surgery services was consulted for management and repair. After a discussion with the son regarding the patient’s wishes, surgical intervention was refused and the patient was conservatively managed and transitioned to hospice care.

Discussion

A true aneurysm differs from a PSA in that true aneurysms involve all three layers of the vessel wall. A PSA consists partly of the vessel wall and partly of encapsulating fibrous tissue or surrounding tissue.

Etiology

Femoral artery PSAs can be iatrogenic, for example, develop following cardiac catheterization or at the anastomotic site of previous surgery.1 The incidence of diagnostic postcatheterization PSA ranges from 0.05% to 2%, whereas interventional postcatheterization PSA ranges from 2% to 6%.2

With the increasing number of peripheral coronary diagnostics and interventions, emergency physicians should include PSA in the differential diagnosis of patients with a recent or remote history of catheterization or bypass grafts. Less commonly, femoral PSAs are caused by non-surgical trauma or infection (ie, mycotic PSA). Patient risk factors for development of PSA include obesity, hypertension, PAD, and anticoagulation.3 Patients with femoral artery PSAs may present with a painful or painless pulsatile mass. Mass effect of the PSA can compress nearby neurovascular structures, leading to femoral neuropathies or limb edema secondary to venous obstruction.4 Complications of embolization or thrombosis can cause limb ischemia, neuropathy, and claudication, while rupture may present with a rapidly expanding groin hematoma. Additionally, sizeable PSAs can cause overlying skin necrosis.5

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of a PSA can be made through Doppler ultrasound, which is the preferred imaging modality due to its accuracy, noninvasive nature, and low cost. Doppler ultrasound has been found to have a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 97% in detecting PSAs. Additional imaging with CTA can provide further definition of vasculopathy.6 Treatment should be considered for patients with a symptomatic femoral PSA, a PSA measuring more than 3 cm, or patients who are on anticoagulation therapy. Studies have shown that observation-only and follow-up may be appropriate for patients with a PSA measuring less than 3 cm. A study by Toursarkissian et al7 found that the majority of PSAs smaller than 3 cm spontaneously resolved in a mean of 23 days without limb-threatening complications.

Treatment

Traditionally, open surgical repair techniques were the only treatment option for PSAs. However, in the early 1990s, the advent of new techniques such as stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, have developed as alternatives to open surgical repair; there has been variable success to these minimally invasive approaches.5,8

Ultrasound-Guided Compression. A conservative approach to treating PSAs, ultrasound-guided compression requires sustained compression by a skilled physician. This technique is associated with significant discomfort to the patient.5 Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. This technique is the treatment of choice for postcatheterization PSA. However, this intervention is contraindicated in patients who have concerning features such as an infected PSA, rapid expansion, skin necrosis, or signs of limb ischemia. Additionally, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is not appropriate for use in patients with a PSA occurring at anastomosis of a synthetic graft and native artery.5

Conclusion

Based on our patient’s clinical presentation and history of aortofemoral bypass surgery, we suspected a femoral PSA. While the PSA noted in our patient was sizeable, imaging studies and clinical examination showed no sign of limb ischemia or rupture.

Femoral PSAs are usually iatrogenic in nature, typically developing shortly after catheterization or a previous bypass surgery. The most serious complication of a PSA is rupture, but a thorough examination of the distal extremity is warranted to assess for limb ischemia as well. Ultrasound imaging is considered the modality of choice based on its high sensitivity and sensitivity for detecting PSAs.

Small PSAs (<3 cm) can be managed medically, but larger PSAs (>3 cm) require treatment. Newer techniques, including stenting, coil insertion, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection are alternatives to open surgical repair of larger, uncomplicated PSAs. However, urgent open surgical repair is the only option when there is evidence of a ruptured PSA, ischemia, or skin necrosis.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

1. Faggioli GL, Stella A, Gargiulo M, Tarantini S, D’Addato M, Ricotta JJ. Morphology of small aneurysms: definition and impact on risk of rupture. Am J Surg. 1994;168(2):131-135.

2. Hessel SJ, Adams DF, Abrams HL. Complications of angiography. Radiology. 1981;138(2):273-281. doi:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455105.

3. Petrou E, Malakos I, Kampanarou S, Doulas N, Voudris V. Life-threatening rupture of a femoral pseudoaneurysm after cardiac catheterization. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2016;10:201-204. doi:10.2174/1874192401610010201.

4. Mees B, Robinson D, Verhagen H, Chuen J. Non-aortic aneurysms—natural history and recommendations for referral and treatment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):370-374.

5. Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation. 2007;115(20):2666-2674. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681973.

6. Coughlin BF, Paushter DM. Peripheral pseudoaneurysms: evaluation with duplex US. Radiology. 1988;168(2):339-342. doi:10.1148/radiology.168.2.3293107.

7. Toursarkissian B, Allen BT, Petrinec D, et al. Spontaneous closure of selected iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulae. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):803-809; discussion 808-809.

8. Corriere MA, Guzman RJ. True and false aneurysms of the femoral artery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(4):216-223. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.09.008.

Don’t delay hip-fracture surgery

Background: Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons and Canadian Institute for Health recommend hip fracture surgery within 48 hours. However, a time-to-surgery threshold after which mortality and complications are increased has not been determined. This study aims to determine a time to surgery threshold for hip-fracture surgery.

Study design: Retrospective cohort trial.

Setting: 72 hospitals in Ontario, Ca., during April 1, 2009-March 31, 2014.

Synopsis: Of the 42,230 adult patients in this study, 14,174 (33.6%) received hip-fracture surgery within 24 hours of emergency department arrival. A matched patient analysis of early surgery (within 24 hours of ED arrival) vs. delayed surgery determined that patients undergoing early operation experienced lower 30-day mortality (5.8% vs 6.5%) and fewer complications (myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia). Major bleeding was not assessed as a complication. Also omitted from analysis were patients undergoing nonoperative hip-fracture management.

These findings suggest a time to surgery of 24 hours may represent a threshold defining higher risk. Two-thirds of patients in this study surpassed this threshold. Hospitalists seeing patients with hip fracture should balance time delay risks with the need for medical optimization.

Bottom line: Wait time greater than 24 hours for adults undergoing hip fracture surgery is associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality and complications.

Citation: Pincus D et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2017 Nov 28;318(20):1994-2003.

Dr. Moulder is assistant professor, University of Virginia Health System.

Background: Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons and Canadian Institute for Health recommend hip fracture surgery within 48 hours. However, a time-to-surgery threshold after which mortality and complications are increased has not been determined. This study aims to determine a time to surgery threshold for hip-fracture surgery.

Study design: Retrospective cohort trial.

Setting: 72 hospitals in Ontario, Ca., during April 1, 2009-March 31, 2014.

Synopsis: Of the 42,230 adult patients in this study, 14,174 (33.6%) received hip-fracture surgery within 24 hours of emergency department arrival. A matched patient analysis of early surgery (within 24 hours of ED arrival) vs. delayed surgery determined that patients undergoing early operation experienced lower 30-day mortality (5.8% vs 6.5%) and fewer complications (myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia). Major bleeding was not assessed as a complication. Also omitted from analysis were patients undergoing nonoperative hip-fracture management.

These findings suggest a time to surgery of 24 hours may represent a threshold defining higher risk. Two-thirds of patients in this study surpassed this threshold. Hospitalists seeing patients with hip fracture should balance time delay risks with the need for medical optimization.

Bottom line: Wait time greater than 24 hours for adults undergoing hip fracture surgery is associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality and complications.

Citation: Pincus D et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2017 Nov 28;318(20):1994-2003.

Dr. Moulder is assistant professor, University of Virginia Health System.

Background: Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons and Canadian Institute for Health recommend hip fracture surgery within 48 hours. However, a time-to-surgery threshold after which mortality and complications are increased has not been determined. This study aims to determine a time to surgery threshold for hip-fracture surgery.

Study design: Retrospective cohort trial.

Setting: 72 hospitals in Ontario, Ca., during April 1, 2009-March 31, 2014.

Synopsis: Of the 42,230 adult patients in this study, 14,174 (33.6%) received hip-fracture surgery within 24 hours of emergency department arrival. A matched patient analysis of early surgery (within 24 hours of ED arrival) vs. delayed surgery determined that patients undergoing early operation experienced lower 30-day mortality (5.8% vs 6.5%) and fewer complications (myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia). Major bleeding was not assessed as a complication. Also omitted from analysis were patients undergoing nonoperative hip-fracture management.

These findings suggest a time to surgery of 24 hours may represent a threshold defining higher risk. Two-thirds of patients in this study surpassed this threshold. Hospitalists seeing patients with hip fracture should balance time delay risks with the need for medical optimization.

Bottom line: Wait time greater than 24 hours for adults undergoing hip fracture surgery is associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality and complications.

Citation: Pincus D et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2017 Nov 28;318(20):1994-2003.

Dr. Moulder is assistant professor, University of Virginia Health System.

Lower risk of ICH with dabigatran as compared to warfarin in atrial fibrillation

Clinical question: Is dabigatran superior to warfarin with regards to the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Several studies – including the RELY trial – have revealed a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage with dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in patients with atrial fibrillation; however, few of these have been on populations generalizable to clinical practice. Furthermore, there are conflicting data on the association of dabigatran with higher rates of myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation versus warfarin.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: The Sentinel Program (national surveillance system) including 17 collaborating institutions and health care delivery systems.

Synopsis: In 25,289 propensity score–matched pairs of commercially insured patients aged 21 years or older starting dabigatran or warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation, dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.09), similar rates of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage, and a potentially higher rate of myocardial infarction (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.22-2.90). However, the association between dabigatran use and myocardial infarction was smaller and not statistically significant in sensitivity analyses. Also, subgroup analyses demonstrated higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran than did warfarin in patients aged 75 years or older and those with kidney dysfunction.

Although providing further reassuring evidence about bleeding risks – particularly intracranial hemorrhage – associated with dabigatran use, this observational study fails to clarify the association between dabigatran and myocardial infarction.

Bottom line: Dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in adults with atrial fibrillation is associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and similar risk of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage.

Citation: Go AS et al. Outcomes of dabigatran and warfarin for atrial fibrillation in contemporary practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Dec.19;167:845-54.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, University of Virginia.

Clinical question: Is dabigatran superior to warfarin with regards to the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Several studies – including the RELY trial – have revealed a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage with dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in patients with atrial fibrillation; however, few of these have been on populations generalizable to clinical practice. Furthermore, there are conflicting data on the association of dabigatran with higher rates of myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation versus warfarin.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: The Sentinel Program (national surveillance system) including 17 collaborating institutions and health care delivery systems.

Synopsis: In 25,289 propensity score–matched pairs of commercially insured patients aged 21 years or older starting dabigatran or warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation, dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.09), similar rates of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage, and a potentially higher rate of myocardial infarction (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.22-2.90). However, the association between dabigatran use and myocardial infarction was smaller and not statistically significant in sensitivity analyses. Also, subgroup analyses demonstrated higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran than did warfarin in patients aged 75 years or older and those with kidney dysfunction.

Although providing further reassuring evidence about bleeding risks – particularly intracranial hemorrhage – associated with dabigatran use, this observational study fails to clarify the association between dabigatran and myocardial infarction.

Bottom line: Dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in adults with atrial fibrillation is associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and similar risk of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage.

Citation: Go AS et al. Outcomes of dabigatran and warfarin for atrial fibrillation in contemporary practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Dec.19;167:845-54.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, University of Virginia.

Clinical question: Is dabigatran superior to warfarin with regards to the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Several studies – including the RELY trial – have revealed a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage with dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in patients with atrial fibrillation; however, few of these have been on populations generalizable to clinical practice. Furthermore, there are conflicting data on the association of dabigatran with higher rates of myocardial infarction in patients with atrial fibrillation versus warfarin.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: The Sentinel Program (national surveillance system) including 17 collaborating institutions and health care delivery systems.

Synopsis: In 25,289 propensity score–matched pairs of commercially insured patients aged 21 years or older starting dabigatran or warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation, dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.09), similar rates of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage, and a potentially higher rate of myocardial infarction (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.22-2.90). However, the association between dabigatran use and myocardial infarction was smaller and not statistically significant in sensitivity analyses. Also, subgroup analyses demonstrated higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran than did warfarin in patients aged 75 years or older and those with kidney dysfunction.

Although providing further reassuring evidence about bleeding risks – particularly intracranial hemorrhage – associated with dabigatran use, this observational study fails to clarify the association between dabigatran and myocardial infarction.

Bottom line: Dabigatran, compared with warfarin, in adults with atrial fibrillation is associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and similar risk of ischemic stroke and extracranial hemorrhage.

Citation: Go AS et al. Outcomes of dabigatran and warfarin for atrial fibrillation in contemporary practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Dec.19;167:845-54.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, University of Virginia.

Providers’ prior imaging patterns and ownership of equipment are strong predictors of low-value imaging

Background: For many common conditions, expert guidelines such as Choosing Wisely recommend against ordering specific low-value tests, yet overuse of these tests remains widespread, and unnecessary care may account for up to a third of all medical expenditures. Studies have demonstrated that there is considerable geographic variation in health care usage and higher overall imaging among clinicians who own imaging equipment. No prior study has assessed whether prior ordering patterns of low-value care predict future ordering patterns or whether providers who order low-value imaging in one clinical scenario are more likely to do so in another scenario.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of insurance claims data.

Setting: Medical claims data from a large U.S. commercial health insurer, inclusive of 29 million commercially insured members across all 50 states from January 2010 to December 2014.

Synopsis: Using the claims database, researchers created three unique study samples to examine clinician predictors of low-value imaging. The study involved outpatient visits by patients aged 18-64 years without red-flag symptoms. The first included 1,007,392 visits across 878,720 patients with acute, uncomplicated low-back pain. Physicians who ordered imaging for the prior patient with back pain were 1.8 times more likely to do so again. Similarly, in 492,804 visits by 417,010 patients with headache, clinicians who ordered imaging on the prior patient demonstrated a twofold higher odds of imaging. Physicians who practiced low-value ordering for one condition were 1.8 times more likely to do so for the other. Across all studies, imaging ownership was an independent predictor (odds ratio, 1.8).

As this study analyzed only claims data, some patients may have warranted imaging based on red-flag symptoms that were not documented. Hospitalists designing initiatives to reduce low-value testing should consider targeting specific providers with a history of low-value test use.

Bottom line: Among commercially insured patients, a clinician’s prior imaging pattern and ownership of imaging equipment were strong independent predictors of low-value back pain and headache imaging.

Citation: Hong AS et al. Clinician-level predictors for ordering low-value imaging. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Nov 1;177(11):1577-85.

Background: For many common conditions, expert guidelines such as Choosing Wisely recommend against ordering specific low-value tests, yet overuse of these tests remains widespread, and unnecessary care may account for up to a third of all medical expenditures. Studies have demonstrated that there is considerable geographic variation in health care usage and higher overall imaging among clinicians who own imaging equipment. No prior study has assessed whether prior ordering patterns of low-value care predict future ordering patterns or whether providers who order low-value imaging in one clinical scenario are more likely to do so in another scenario.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of insurance claims data.

Setting: Medical claims data from a large U.S. commercial health insurer, inclusive of 29 million commercially insured members across all 50 states from January 2010 to December 2014.

Synopsis: Using the claims database, researchers created three unique study samples to examine clinician predictors of low-value imaging. The study involved outpatient visits by patients aged 18-64 years without red-flag symptoms. The first included 1,007,392 visits across 878,720 patients with acute, uncomplicated low-back pain. Physicians who ordered imaging for the prior patient with back pain were 1.8 times more likely to do so again. Similarly, in 492,804 visits by 417,010 patients with headache, clinicians who ordered imaging on the prior patient demonstrated a twofold higher odds of imaging. Physicians who practiced low-value ordering for one condition were 1.8 times more likely to do so for the other. Across all studies, imaging ownership was an independent predictor (odds ratio, 1.8).

As this study analyzed only claims data, some patients may have warranted imaging based on red-flag symptoms that were not documented. Hospitalists designing initiatives to reduce low-value testing should consider targeting specific providers with a history of low-value test use.

Bottom line: Among commercially insured patients, a clinician’s prior imaging pattern and ownership of imaging equipment were strong independent predictors of low-value back pain and headache imaging.

Citation: Hong AS et al. Clinician-level predictors for ordering low-value imaging. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Nov 1;177(11):1577-85.

Background: For many common conditions, expert guidelines such as Choosing Wisely recommend against ordering specific low-value tests, yet overuse of these tests remains widespread, and unnecessary care may account for up to a third of all medical expenditures. Studies have demonstrated that there is considerable geographic variation in health care usage and higher overall imaging among clinicians who own imaging equipment. No prior study has assessed whether prior ordering patterns of low-value care predict future ordering patterns or whether providers who order low-value imaging in one clinical scenario are more likely to do so in another scenario.

Study design: Retrospective analysis of insurance claims data.

Setting: Medical claims data from a large U.S. commercial health insurer, inclusive of 29 million commercially insured members across all 50 states from January 2010 to December 2014.

Synopsis: Using the claims database, researchers created three unique study samples to examine clinician predictors of low-value imaging. The study involved outpatient visits by patients aged 18-64 years without red-flag symptoms. The first included 1,007,392 visits across 878,720 patients with acute, uncomplicated low-back pain. Physicians who ordered imaging for the prior patient with back pain were 1.8 times more likely to do so again. Similarly, in 492,804 visits by 417,010 patients with headache, clinicians who ordered imaging on the prior patient demonstrated a twofold higher odds of imaging. Physicians who practiced low-value ordering for one condition were 1.8 times more likely to do so for the other. Across all studies, imaging ownership was an independent predictor (odds ratio, 1.8).

As this study analyzed only claims data, some patients may have warranted imaging based on red-flag symptoms that were not documented. Hospitalists designing initiatives to reduce low-value testing should consider targeting specific providers with a history of low-value test use.

Bottom line: Among commercially insured patients, a clinician’s prior imaging pattern and ownership of imaging equipment were strong independent predictors of low-value back pain and headache imaging.

Citation: Hong AS et al. Clinician-level predictors for ordering low-value imaging. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Nov 1;177(11):1577-85.

High 5-year mortality in patients admitted with heart failure regardless of ejection fraction

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Use procalcitonin-guided algorithms to guide antibiotic therapy for acute respiratory infections to improve patient outcomes

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Myelodysplastic syndromes: etiologies, evaluation, and therapy

In this interview, Dr David Henry, MD, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and David Steensma, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, talk about myelodysplasic syndromes, from diagnosis, evaluation, and etiologies, to therapy options and molecular sequencing.

Listen to the podcast below, or click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read a transcript of the interview.

In this interview, Dr David Henry, MD, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and David Steensma, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, talk about myelodysplasic syndromes, from diagnosis, evaluation, and etiologies, to therapy options and molecular sequencing.

Listen to the podcast below, or click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read a transcript of the interview.

In this interview, Dr David Henry, MD, the Editor-in-Chief of JCSO, and David Steensma, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, talk about myelodysplasic syndromes, from diagnosis, evaluation, and etiologies, to therapy options and molecular sequencing.

Listen to the podcast below, or click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read a transcript of the interview.

Delaying lumbar punctures for a head CT may result in increased mortality in acute bacterial meningitis

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.