User login

Genital Lentiginosis: A Benign Pigmentary Abnormality Often Raising Concern for Melanoma

To the Editor:

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

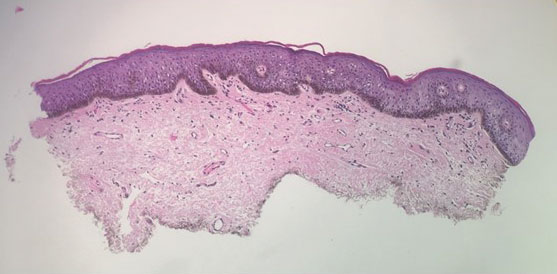

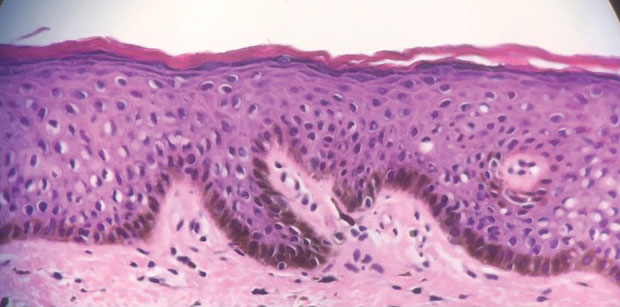

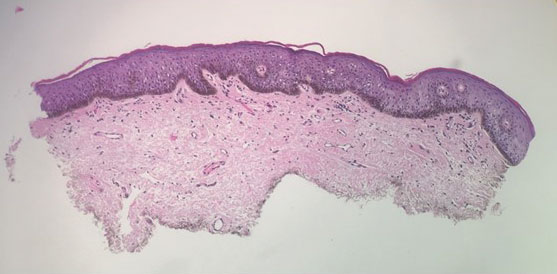

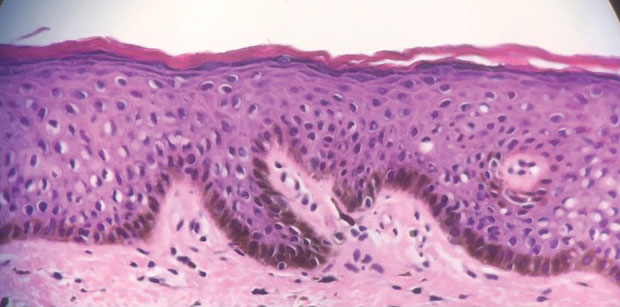

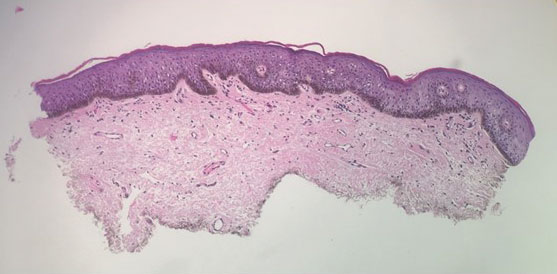

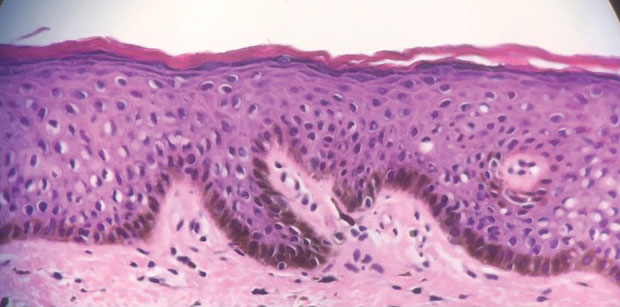

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

To the Editor:

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

To the Editor:

Genital lentiginosis (also known as mucosal melanotic macules, vulvar melanosis, penile melanosis, and penile lentigines) occurs in men and women.1 Lesions present in adult life as multifocal, asymmetrical, pigmented patches that can have a mottled appearance or exhibit skip areas. The irregular appearance of the pigmented areas often raises concern for melanoma. Biopsy reveals increased pigmentation along the basal layer of the epidermis; the irregular distribution of single melanocytes and pagetoid spread typical of melanoma in situ is not identified.

Genital lentiginosis usually occurs as an isolated finding; however, the condition can be a manifestation of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, Carney complex, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome.1-3 When it occurs as an isolated finding, the patient can be reassured and treatment is unnecessary. Because genital lentiginosis may mimic the appearance of melanoma, it is important for physicians to differentiate the two and make a correct diagnosis. We present a case of genital lentiginosis that mimicked vulvar melanoma.

A 64-year-old woman was referred by her gynecologist to dermatology to rule out vulvar melanoma. The patient had a history of hypothyroidism and hypercholesterolemia but was otherwise in good health. Genital examination revealed asymptomatic pigmented macules and patches of unknown duration (Figure 1). Specimens were taken from 3 areas by punch biopsy to clarify the diagnosis. All 3 specimens showed identical features including basilar pigmentation, occasional melanophages in the papillary dermis, and no evidence of nests or pagetoid spread of atypical melanocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Histologic findings were diagnostic for genital lentiginosis. The patient was reassured, and no treatment was provided. At 6-month follow-up there was no change in clinical appearance.

Genital lentiginosis is characterized by brown lesions that can have a mottled appearance and often are associated with skip areas.1 Lesions can be strikingly irregular and darkly pigmented.

Although the lesions of genital lentiginosis most often are isolated findings, they can be a clue to several uncommon syndromes such as autosomal-dominant Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, which is associated with genital lentiginosis, intestinal polyposis, and macrocephaly.3 Vascular malformations, lipomatosis, verrucal keratoses, and acrochordons can occur. Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden syndrome may share genetic linkage; mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) has been implicated in both syndromes.4 Underlying Carney complex should be excluded when genital lentiginosis is encountered.

Genital lentiginosis is idiopathic in most instances, but reports of lesions occurring after annular lichen planus suggest a possible mechanism.5 The disappearance of lentigines after imatinib therapy suggests a role for c-kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that is involved in intracellular signaling, in some cases.6 At times, lesions can simulate trichrome vitiligo or have a reticulate pattern.7

Men and women present at different points in the course of disease. Men often present with penile lesions 14 years after onset, on average; they notice a gradual increase in the size of lesions. Because women can have greater difficulty self-examining the genital region, they tend to present much later in the course but often within a few months after initial inspection.1,8

Genital lentiginosis can mimic melanoma with nonhomogeneous pigmentation, asymmetry, and unilateral distribution, which makes dermoscopic assessment of colors helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Melanoma is associated with combinations of gray, red, blue, and white, which are not found in genital lentiginosis.9

Biopsy of a genital lentigo is diagnostic, distinguishing the lesion from melanoma—failing to reveal the atypical melanocytes and pagetoid spread characteristic of melanoma in situ. Histologic findings can cause diagnostic difficulties when concurrent lichen sclerosus is associated with genital lentigines or nevi.10

Lentigines on sun-damaged skin or in the setting of xeroderma pigmentosum have been associated with melanoma,11-13 but genital lentigines are not considered a form of precancerous melanosis. In women, early diagnosis is important when there is concern for melanoma because the prognosis for vulvar melanoma is improved in thin lesions.14

Other entities in the differential include secondary syphilis, which commonly presents as macules and scaly papules and can be found on mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity,15 as well as Kaposi sarcoma, which is characterized by purplish, brown, or black macules, plaques, and nodules, more commonly in immunosuppressed patients.16

To avoid unwarranted concern and unnecessary surgery, dermatologists should be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adults.

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

- Hwang L, Wilson H, Orengo I. Off-center fold: irregular, pigmented genital macules. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1559-1564. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.12.1559-b

- Rhodes AR, Silverman RA, Harrist TJ, et al. Mucocutaneous lentigines, cardiomucocutaneous myxomas, and multiple blue nevi: the “LAMB” syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:72-82. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80047-x

- Erkek E, Hizel S, Sanl C, et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:639-643. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.022

- Blum RR, Rahimizadeh A, Kardon N, et al. Genital lentigines in a 6-year-old boy with a family history of Cowden’s disease: clinical and genetic evidence of the linkage between Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome and Cowden’s disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:228-230. doi:10.1177/120347540100500307

- Isbary G, Dyall-Smith D, Coras-Stepanek B, et al. Penile lentigo (genital mucosal macule) following annular lichen planus: a possible association? Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:159-161. doi:10.1111/ajd.12169

- Campbell T, Felsten L, Moore J. Disappearance of lentigines in a patient receiving imatinib treatment for familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1313-1316. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.263

- Romero- A, R, , et al. Reticulate genital pigmentation associated with localized vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146:574-575. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.69

- Barnhill RL, Albert LS, Shama SK, et al. Genital lentiginosis: a clinical and histopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:453-460. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70064-o

- De Giorgi V, Gori A, Salvati L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of vulvar melanosis over the last 20 years. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1185–1191. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2528

- El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Soyer HP, Schaeppi H, et al. Genital lentigines and melanocytic nevi with superimposed lichen sclerosus: a diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:690-694. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.034

- Shatkin M, Helm MF, Muhlbauer A, et al. Solar lentigo evolving into fatal metastatic melanoma in a patient who initially refused surgery. N A J Med Sci. 2020;1:28-31. doi:10.7156/najms.2020.1301028

- Stern JB, Peck GL, Haupt HM, et al. Malignant melanoma in xeroderma pigmentosum: search for a precursor lesion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:591-594. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70079-9

- Byrom L, Barksdale S, Weedon D, et al. Unstable solar lentigo: a defined separate entity. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:229-234. doi:10.1111/ajd.12447

- Panizzon RG. Vulvar melanoma. Semin Dermatol. 1996;15:67-70. doi:10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80021-6

- Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164. doi:10.1097/00007435-198010000-00002

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151. doi:10.1002/jso.20090

Practice Points

- The irregular appearance of genital lentiginosis—multifocal, asymmetric, irregular, and darkly pigmented patches—often raises concern for melanoma but is benign.

- Certain genetic conditions can present with genital lentiginosis.

- Dermoscopic assessment of the lesion color is highly helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis; seeing no gray, red, blue, or white makes melanoma less likely.

- Be aware of genital lentigines and their characteristic presentation in adulthood to avoid unwarranted concern and unneeded surgery.

Erythematous swollen ear

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

A 25-year-old woman presented with an exceedingly tender right ear. She’d had the helix of her ear pierced 3 days prior to presentation and 2 days after that, the ear had become tender. The tenderness was progressively worsening and associated with throbbing pain. The patient, who’d had her ears pierced before, was otherwise in good health and denied fever, chills, or travel outside of the country. She had been going to the gym regularly and took frequent showers. Physical examination revealed an erythematous swollen ear that was tender to the touch (FIGURE). The entire auricle was swollen except for the earlobe. The patient also reported purulent material draining from the helical piercing site.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Auricular perichondritis

Auricular perichondritis is an inflammation of the connective tissue surrounding the cartilage of the ear. Infectious and autoimmune factors may play a role. The underlying cartilage also may become involved. A useful clinical clue to the diagnosis of auricular perichondritis is sparing of the earlobe, which does not contain cartilage. Autoimmune causes typically have bilateral involvement. Infectious causes are usually associated with trauma and purulent drainage at the wound site. Ear piercings are an increasingly common cause, but perichondritis due to minor trauma, as a surgical complication, or in the absence of an obvious inciting trigger can occur. A careful history usually will reveal the cause.

In this case, the patient indicated that an open piercing gun at a shopping mall kiosk had been used to pierce her ear. Piercing with a sterile straight needle would have been preferable and less likely to be associated with secondary infection, as the shearing trauma to the perichondrium experienced with a piercing gun is thought to predispose to infection.1 Exposure to fresh water from the shower could have been a source for Pseudomonas infection.1

Differential: Pinpointing the diagnosis early is vital

A red and tender ear can raise a differential diagnosis that includes erysipelas, relapsing polychondritis, and auricular perichondritis. Erysipelas is a bacterial infection that spreads through the lymphatic system and is associated with intense and well-demarcated erythema. Erysipelas typically involves the face or lower legs. Infection after piercing or traumatic injury should raise suspicion of pseudomonal infection.2-5 Untreated infection can spread quickly and lead to permanent ear deformity. Although the same pattern of inflammation can be seen in relapsing polychondritis, relapsing polychondritis typically involves both ears as well as the eyes and joints.

Prompt treatment is necessary to avoid cosmetic disfigurement

The timing of the reaction in our patient made infection obvious because Pseudomonas aeruginosa seems to have a particular affinity for damaged cartilage.2

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily is the treatment of choice. Although many skin infections can be empirically treated with oral cephalosporin, penicillin, or erythromycin, it is important to recognize that infected piercing sites and auricular perichondritis due to pseudomonal infection will not respond to these agents. That’s because these agents do not provide as good coverage for Pseudomonas as they do for Staphylococci or other bacteria more often associated with skin infection. Treatment with an agent such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or oral cephalexin can mean the loss of valuable time and subsequent cosmetic disfigurement.6

Continue to: When fluctuance is present...

When fluctuance is present, incision and drainage, or even debridement, may be necessary. When extensive infection leads to cartilage necrosis and liquefaction, treatment is difficult and may result in lasting disfigurement. Prompt empiric treatment currently is considered the best option.6

Our patient was prescribed a course of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days. She noted improvement within 2 days, and the infection resolved without complication.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, Penn State Health Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Dr, HU14, Hershey, PA 17033; [email protected]

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.

1. Sandhu A, Gross M, Wylie J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa necrotizing chondritis complicating high helical ear piercing case report: clinical and public health perspectives. Can J Public Health. 2007;98:74-77.

2. Prasad HK, Sreedharan S, Prasad HS, et al. Perichondritis of the auricle and its management. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:530-534.

3. Fisher CG, Kacica MA, Bennett NM. Risk factors for cartilage infections of the ear. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:204-209.

4. Lee TC, Gold WL. Necrotizing Pseudomonas chondritis after piercing of the upper ear. CMAJ. 2011;183:819-821.

5. Rowshan HH, Keith K, Baur D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the auricular cartilage caused by “high ear piercing”: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:543-546.

6. Liu ZW, Chokkalingam P. Piercing associated perichondritis of the pinna: are we treating it correctly? J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:505-508.