User login

Back pain as a sign of inferior vena cava filter complications

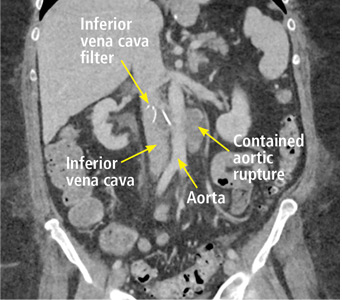

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

A 63-year-old woman presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic back pain after a fall. She was taking warfarin because of a history of factor V Leiden, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, for which a temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter had been placed 8 years ago. Her physicians had subsequently tried to remove the filter, without success. Some time after that, 1 of the filter struts had been removed after it migrated through her abdominal wall.

Laboratory testing revealed a supratherapeutic international normalized ratio of 8.5.

The patient underwent endovascular aneurysm repair with adequate placement of a vascular graft. She was discharged on therapeutic anticoagulation, and her back pain had notably improved.

COMPLICATIONS OF IVC FILTERS

In the United States, the use of IVC filters has increased significantly over the last decade, with placement rates ranging from 12% to 17% in patients with venous thromboembolism.1

The American Heart Association recommends filter placement for patients with venous thromboembolism for whom anticoagulation has failed or is contraindicated, patients unable to withstand pulmonary embolism, and patients who are hemodynamically unstable.2 While indications vary in the guidelines released by different societies, filters are most often placed in patients who have an acute bleed, significant surgery after admission for venous thromboembolism, metastatic cancer, and severe illness.3

Complications can occur during and after insertion and during removal. They are more frequent with temporary than with permanent filters, and include filter movement and fracture as well as occlusion and penetration.4,5

In our patient, we believe that the 3 remaining filter struts likely penetrated the wall of the IVC to the extent that they encountered adjacent structures (aorta, duodenum, kidney).

Of cases of IVC filter penetration reported to a US Food and Drug Administration database, 13.1% involved small bowel perforation, 6.5% involved aortic perforation, and 4.2% involved retroperitoneal bleeding. Symptoms such as abdominal and back pain were present in 38.3% of cases involving IVC penetration.5

Therefore, the differential diagnosis for patients with a history of IVC filter placement presenting with these symptoms should address filter complications, including occlusion, incorrect placement, fracture, migration, and penetration of the filter.4 If complications occur, treatment options include anticoagulation, endovascular repair, and surgical intervention.

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

- Alkhouli M, Bashir R. Inferior vena cava filters in the United States: less is more. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(3):742–743. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.010

- Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123(16):1788–1830. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f

- White RH, Geraghty EM, Brunson A, et al. High variation between hospitals in vena cava filter use for venous thromboembolism. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(7):506–512. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2352

- Sella DM, Oldenburg WA. Complications of inferior vena cava filters. Semin Vasc Surg 2013; 26(1):23–28. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2013.04.005

- Andreoli JM, Lewandowski RJ, Vogelzang RL, Ryu RK. Comparison of complication rates associated with permanent and retrievable inferior vena cava filters: a review of the MAUDE database. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014; 25(8):1181–1185. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2014.04.016

Atopic Dermatitis Pipeline

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

Just when you might have thought dermatologic therapies were peaking, along came another banner year in atopic dermatitis (AD). Last year we saw the landmark launch of dupilumab, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved biologic therapy for AD. Dupilumab addresses a novel mechanism of AD in adults by blocking IL-4 and IL-13, which both play a central role in the type 2 helper T cell (TH2) axis on the dual development of barrier-impaired skin and aberrant immune response including IgE to cutaneous aggravating agents with resultant inflammation. Additional information has shown direct effects to reduce itch in AD.1 A 12-week study of dupilumab monotherapy showed that 85% (47/55) of treated patients had at least a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score and 40% (22/55) were clear or almost clear on the investigator global assessment. With concomitant corticosteroid therapy, 100% of patients achieved EASI-50.2 Also notable, 2017 ushered in the appearance of a novel iteration of the 30-year-old concept of phosphodiesterase inhibition with the approval of the topical agent crisaborole for AD treatment in patients 2 years and older, which has been shown to be effective in both children and adults.3,4 However, despite these leaps of advancement in the care of AD, by no means has the condition been cured.

Atopic dermatitis has remained an incurable disease due to many factors: (1) variable immunologic and environmental triggers and patient disease course; (2) intolerance to therapeutic agents, including an enhanced sense of stinging and/or reactivity; (3) poor access to novel therapies among underserved patient populations; (4) lack of available data and information on variable treatment response by ethnicity and race; and (5) the absence of biologic treatments for severe childhood AD to modify long-term recurrence and progression of atopy, which is probably the most important issue, as the majority of AD cases start in children 5 years and younger.

Instituting a treatment today to provide children with disease-free skin for a lifetime truly is the Holy Grail in pediatric dermatology. To aid in the progress toward this goal, a deeper understanding of the manifestation of pediatric versus adult AD is now being investigated. It is clear that with adult chronicity, type 1 helper T cell (TH1) axis activity and prolonged defects are triggered in barrier maturation; however, recent data have started to demonstrate that the youngest patients have different issues in lipid maturation and lack TH1 activation. In particular, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 2 and fatty acid 2-hydroxylase is preferentially downregulated in children.5 It appears that the young immune system may be ripe for immune modification, which previously has been demonstrated with wild-type viral infections of varicella in children.6 However, future research will focus on what kind of tweaks to the immune system are required.

To encapsulate the AD pipeline, we will review drug trials that are in active recruitment as well as recently published data, which constitute an exciting group full of modifications of current therapies and agents with novel mechanisms of action.

Therapies targeting new mechanisms of action include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which have shown promising results for alopecia areata and vitiligo vulgaris. These agents may create selective modification of the immune system and are being tested topically and orally (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03011892).

Another mechanism that currently is being studied includes a topical IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor, which would hopefully mimic the efficacy of dupilumab, antioxidant therapies, and antimicrobials (NCT03351777, NCT03381625, NCT02910011).

Data on the outcome of a phase 3 trial of dupilumab in adolescents has been released but not yet published by the manufacturer and shows promising results in children aged 12 to 17 years, both in reduction of EASI score and in achieving clear or almost clear skin.11 Interestingly, limited data available from a press release reported similar results with dupilumab injection every 2 weeks versus every 4 weeks, which may give alternative dosing regimens in this age group once approved11; however, publication has yet to occur for the latter data.

Other mechanistic agents include blockade of cytokines and interleukins, particularly those involved in type 2 helper T cell (TH2) activity, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (a cytokine), as well as targeted single inhibition of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 and/or their receptors. Nemolizumab, an anti–IL-31 receptor A antibody, is showing promise in the control of AD-associated itch and reduction in EASI

The future of AD therapy is anyone’s guess. Having entered the biologic era with dupilumab, we have a high bar set for efficacy and safety of AD therapies, yet there remains a core group of AD patients who have not yet achieved clearance or refuse injectables; therefore, adjunctive or alternative therapeutics are still needed. Furthermore, we still have not identified who will best benefit long-term from systemic intervention and how to best effect long-term disease control with biologics or novel agents, and choosing the therapy based on patient disease characteristics or serotyping has not yet come of age. It is exciting to think about what next year will bring!

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Oncotarget. 2017;8:108480-108491.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Murrell D, Gebauer K, Spelman L, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adults with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2a, vehicle-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:1108-1112.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.e6.

- Brunner PM, Israel A, Zhang N, et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is characterized by TH2/TH17/TH22-centered inflammation and lipid alterations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:2094-2106.

- Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Silverberg NB, et al. Chickenpox in childhood is associated with decreased atopic disorders, IgE, allergic sensitization, and leukocyte subsets. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:50-58.

- Paller AS, Kabashima K, Bieber T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: end of the drought? Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:633-643.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: the pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:387-397.

- Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902-911.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study [published online February 1, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) showed positive phase 3 results in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis [press release]. Tarrytown, NY: Sanofi; May 16, 2018. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/dupixent-dupilumab-showed-positive-phase-3-results-in-adolescents-with-inadequately-controlled-moderate-to-severe-atopic-dermatitis-300649146.html. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- Ruzicka T, Hanifin JM, Furue M, et al. Anti–interleukin-31 receptor A antibody for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:826-835.