User login

Coalescing Hyperkeratotic Plaques and Papules

The Diagnosis: X-Linked Ichthyosis

Immunohistochemical staining of a punch biopsy specimen from the left foot with cytokeratin markers AE1/3, 5/6, and 19 showed normal positive uptake. Further workup was recommended, and the patient was referred to genetics for an ichthyosis gene panel. DNA sequencing revealed a c.1121G>A transition in exon 10 of the steroid sulfatase gene, STS, consistent with X-linked ichthyosis (XLI).

X-linked ichthyosis, also known as steroid sulfatase deficiency and X-linked recessive ichthyosis, is a congenital skin disorder classified in 1965 by Wells and Kerr.1 Ichthyoses are a heterogenous group of acquired and congenital disorders of keratinization that manifest with xerosis, hyperkeratosis, and scaling.2 Of more than 20 ichthyoses, XLI is the second most common ichthyosis, with a prevalence of 1 in 6000 males.3 X-linked ichthyosis occurs almost exclusively in males, and although females can be carriers, they rarely exhibit skin manifestations.4

X-linked ichthyosis is caused by either a partial or full deletion or mutation in the STS gene on the X chromosome.2 The absence of STS activity results in the accumulation of cholesterol sulfate in the stratum corneum, leading to corneocyte cohesion, hyperkeratosis, and impaired skin permeability. The most common clinical phenotype is characterized by polygonal scales concentrated on the upper and lower extremities as well as the trunk (Figure), consistent with our patient's clinical presentation.5

anterior knees (A) as well as large exophytic papules on the upper

chest and neck (B).

X-linked ichthyosis typically presents in the first 6 months of life as generalized desquamation and xerosis that progresses to fine scaling on the trunk and extremities, more commonly and heavily involving the legs; however, the extensor surfaces of the arms also may be affected.6 After the neonatal period, fine scaling persists on the trunk and extremities, but scales often become coarser and darker over time. Although scaling is generalized, it typically spares the antecubital and popliteal fossae, palms, soles, and midface. The lateral face, axillae, and neck always remain involved.4 The most common extracutaneous manifestations of XLI affect the ocular, genitourinary, and cognitive/behavioral systems. Patients can develop corneal comma-shaped opacities, hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, and an increased risk for testicular cancer. Female carriers may have prolonged delivery of affected neonates.2,5,7-9 Given the unrelated debilitating neurologic consequences of our patient's presenting subarachnoid hemorrhage, further workup was not pursued into these associations.

Although XLI is most commonly diagnosed in early childhood, it also must be considered in adult patients presenting with severe scaling of the trunk, arms, and legs who have not had prior dermatologic workup. Given the similarity of XLI presentation to other ichthyoses, particularly ichthyosis vulgaris, lamellar ichthyosis, and ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens, genetic analysis is the most accurate diagnostic tool and should be considered in patients with an atypical presentation. Rupioid psoriasis also may be considered and can be confirmed on biopsy. Diagnosis of XLI should prompt symptomatic treatment, genetic counseling, and workup for extracutaneous manifestations.

- Wells RS, Kerr CB. Genetic classification of ichthyosis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:1-6.

- Fernandes NF, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. X-linked ichthyosis: an oculocutaneous genodermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:480-485.

- Hernández-Martín A, González-Sarmiento R, De Unamuno P. X-linked ichthyosis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:617-627.

- Elias PM, Williams ML, Choi EH, et al. Role of cholesterol sulfate in epidermal structure and function: lessons from X-linked ichthyosis [published online November 27, 2013]. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:353-361.

- Wu B, Paller AS. Ichthyosis, X-Linked. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

- Marukian NV, Choate KA. Recent advances in understanding ichthyosis pathogenesis. F1000Res. 2016;5. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8584.1.

- Baek WS, Aypar U. Case report neurological manifestations of X-linked ichthyosis: case report and review of the literature [published online August 13, 2017]. 2017;2017:9086408.

- Brookes KJ, Hawi Z, Park J, et al. Polymorphisms of the steroid sulfatase (STS) gene are associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and influence brain tissue mRNA expression. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153:1417-1424.

- Kent L, Emerton J, Bhadravathi V, et al. X-linked ichthyosis (steroid sulfatase deficiency) is associated with increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and social communication deficits. J Med Genet. 2008;45:519-524.

The Diagnosis: X-Linked Ichthyosis

Immunohistochemical staining of a punch biopsy specimen from the left foot with cytokeratin markers AE1/3, 5/6, and 19 showed normal positive uptake. Further workup was recommended, and the patient was referred to genetics for an ichthyosis gene panel. DNA sequencing revealed a c.1121G>A transition in exon 10 of the steroid sulfatase gene, STS, consistent with X-linked ichthyosis (XLI).

X-linked ichthyosis, also known as steroid sulfatase deficiency and X-linked recessive ichthyosis, is a congenital skin disorder classified in 1965 by Wells and Kerr.1 Ichthyoses are a heterogenous group of acquired and congenital disorders of keratinization that manifest with xerosis, hyperkeratosis, and scaling.2 Of more than 20 ichthyoses, XLI is the second most common ichthyosis, with a prevalence of 1 in 6000 males.3 X-linked ichthyosis occurs almost exclusively in males, and although females can be carriers, they rarely exhibit skin manifestations.4

X-linked ichthyosis is caused by either a partial or full deletion or mutation in the STS gene on the X chromosome.2 The absence of STS activity results in the accumulation of cholesterol sulfate in the stratum corneum, leading to corneocyte cohesion, hyperkeratosis, and impaired skin permeability. The most common clinical phenotype is characterized by polygonal scales concentrated on the upper and lower extremities as well as the trunk (Figure), consistent with our patient's clinical presentation.5

anterior knees (A) as well as large exophytic papules on the upper

chest and neck (B).

X-linked ichthyosis typically presents in the first 6 months of life as generalized desquamation and xerosis that progresses to fine scaling on the trunk and extremities, more commonly and heavily involving the legs; however, the extensor surfaces of the arms also may be affected.6 After the neonatal period, fine scaling persists on the trunk and extremities, but scales often become coarser and darker over time. Although scaling is generalized, it typically spares the antecubital and popliteal fossae, palms, soles, and midface. The lateral face, axillae, and neck always remain involved.4 The most common extracutaneous manifestations of XLI affect the ocular, genitourinary, and cognitive/behavioral systems. Patients can develop corneal comma-shaped opacities, hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, and an increased risk for testicular cancer. Female carriers may have prolonged delivery of affected neonates.2,5,7-9 Given the unrelated debilitating neurologic consequences of our patient's presenting subarachnoid hemorrhage, further workup was not pursued into these associations.

Although XLI is most commonly diagnosed in early childhood, it also must be considered in adult patients presenting with severe scaling of the trunk, arms, and legs who have not had prior dermatologic workup. Given the similarity of XLI presentation to other ichthyoses, particularly ichthyosis vulgaris, lamellar ichthyosis, and ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens, genetic analysis is the most accurate diagnostic tool and should be considered in patients with an atypical presentation. Rupioid psoriasis also may be considered and can be confirmed on biopsy. Diagnosis of XLI should prompt symptomatic treatment, genetic counseling, and workup for extracutaneous manifestations.

The Diagnosis: X-Linked Ichthyosis

Immunohistochemical staining of a punch biopsy specimen from the left foot with cytokeratin markers AE1/3, 5/6, and 19 showed normal positive uptake. Further workup was recommended, and the patient was referred to genetics for an ichthyosis gene panel. DNA sequencing revealed a c.1121G>A transition in exon 10 of the steroid sulfatase gene, STS, consistent with X-linked ichthyosis (XLI).

X-linked ichthyosis, also known as steroid sulfatase deficiency and X-linked recessive ichthyosis, is a congenital skin disorder classified in 1965 by Wells and Kerr.1 Ichthyoses are a heterogenous group of acquired and congenital disorders of keratinization that manifest with xerosis, hyperkeratosis, and scaling.2 Of more than 20 ichthyoses, XLI is the second most common ichthyosis, with a prevalence of 1 in 6000 males.3 X-linked ichthyosis occurs almost exclusively in males, and although females can be carriers, they rarely exhibit skin manifestations.4

X-linked ichthyosis is caused by either a partial or full deletion or mutation in the STS gene on the X chromosome.2 The absence of STS activity results in the accumulation of cholesterol sulfate in the stratum corneum, leading to corneocyte cohesion, hyperkeratosis, and impaired skin permeability. The most common clinical phenotype is characterized by polygonal scales concentrated on the upper and lower extremities as well as the trunk (Figure), consistent with our patient's clinical presentation.5

anterior knees (A) as well as large exophytic papules on the upper

chest and neck (B).

X-linked ichthyosis typically presents in the first 6 months of life as generalized desquamation and xerosis that progresses to fine scaling on the trunk and extremities, more commonly and heavily involving the legs; however, the extensor surfaces of the arms also may be affected.6 After the neonatal period, fine scaling persists on the trunk and extremities, but scales often become coarser and darker over time. Although scaling is generalized, it typically spares the antecubital and popliteal fossae, palms, soles, and midface. The lateral face, axillae, and neck always remain involved.4 The most common extracutaneous manifestations of XLI affect the ocular, genitourinary, and cognitive/behavioral systems. Patients can develop corneal comma-shaped opacities, hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, and an increased risk for testicular cancer. Female carriers may have prolonged delivery of affected neonates.2,5,7-9 Given the unrelated debilitating neurologic consequences of our patient's presenting subarachnoid hemorrhage, further workup was not pursued into these associations.

Although XLI is most commonly diagnosed in early childhood, it also must be considered in adult patients presenting with severe scaling of the trunk, arms, and legs who have not had prior dermatologic workup. Given the similarity of XLI presentation to other ichthyoses, particularly ichthyosis vulgaris, lamellar ichthyosis, and ichthyosis bullosa of Siemens, genetic analysis is the most accurate diagnostic tool and should be considered in patients with an atypical presentation. Rupioid psoriasis also may be considered and can be confirmed on biopsy. Diagnosis of XLI should prompt symptomatic treatment, genetic counseling, and workup for extracutaneous manifestations.

- Wells RS, Kerr CB. Genetic classification of ichthyosis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:1-6.

- Fernandes NF, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. X-linked ichthyosis: an oculocutaneous genodermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:480-485.

- Hernández-Martín A, González-Sarmiento R, De Unamuno P. X-linked ichthyosis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:617-627.

- Elias PM, Williams ML, Choi EH, et al. Role of cholesterol sulfate in epidermal structure and function: lessons from X-linked ichthyosis [published online November 27, 2013]. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:353-361.

- Wu B, Paller AS. Ichthyosis, X-Linked. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

- Marukian NV, Choate KA. Recent advances in understanding ichthyosis pathogenesis. F1000Res. 2016;5. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8584.1.

- Baek WS, Aypar U. Case report neurological manifestations of X-linked ichthyosis: case report and review of the literature [published online August 13, 2017]. 2017;2017:9086408.

- Brookes KJ, Hawi Z, Park J, et al. Polymorphisms of the steroid sulfatase (STS) gene are associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and influence brain tissue mRNA expression. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153:1417-1424.

- Kent L, Emerton J, Bhadravathi V, et al. X-linked ichthyosis (steroid sulfatase deficiency) is associated with increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and social communication deficits. J Med Genet. 2008;45:519-524.

- Wells RS, Kerr CB. Genetic classification of ichthyosis. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:1-6.

- Fernandes NF, Janniger CK, Schwartz RA. X-linked ichthyosis: an oculocutaneous genodermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:480-485.

- Hernández-Martín A, González-Sarmiento R, De Unamuno P. X-linked ichthyosis: an update. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:617-627.

- Elias PM, Williams ML, Choi EH, et al. Role of cholesterol sulfate in epidermal structure and function: lessons from X-linked ichthyosis [published online November 27, 2013]. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:353-361.

- Wu B, Paller AS. Ichthyosis, X-Linked. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

- Marukian NV, Choate KA. Recent advances in understanding ichthyosis pathogenesis. F1000Res. 2016;5. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8584.1.

- Baek WS, Aypar U. Case report neurological manifestations of X-linked ichthyosis: case report and review of the literature [published online August 13, 2017]. 2017;2017:9086408.

- Brookes KJ, Hawi Z, Park J, et al. Polymorphisms of the steroid sulfatase (STS) gene are associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and influence brain tissue mRNA expression. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153:1417-1424.

- Kent L, Emerton J, Bhadravathi V, et al. X-linked ichthyosis (steroid sulfatase deficiency) is associated with increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism and social communication deficits. J Med Genet. 2008;45:519-524.

A 67-year-old man with a history of congestive heart failure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and schizophrenia was admitted to the hospital for subarachnoid hemorrhage and was noted to have heavy scaling on the bilateral legs. Given recent medical events, the patient was nonconversant at the time of consultation, but his daughter provided his medical history at bedside. The patient usually wore long-sleeved clothing and pants, thus no one had seen his skin in many years, and it was unclear how long the scaling had been present. His family history was notable for eczema in distant relatives but negative for comparable conditions. Physical examination revealed thick lichenified skin with many large, exophytic, brown papules (largest measured 1.5×1×1 cm) and platelike scaling on the anterior chest, abdomen, lateral arms, and forearms. Extensive coalescing hyperkeratotic plaques and papules (up to 1 cm in thickness) were present on the anterior legs and feet, and scattered verrucous brown papules were noted on the plantar aspects of the bilateral feet. A punch biopsy of the left foot revealed extensive, dense, compact, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with a preserved granular layer with no epidermolysis.

Comment on “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site”

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

To the Editor:

A recent Cutis article, “Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site” (Cutis. 2016;97:364-367), highlighted the localization of a Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) within a well-healed scar resulting from a vein harvesting procedure performed 18 years prior to presentation. Their discussion focused on factors that may have contributed to the development of the MCC at that specific location. As noted by the authors, this case does not classically fit under the umbrella of a Marjolin ulcer given the stable, well-healed clinical appearance of the scar. We agree and believe it is not secondary to chance either but consistent with Wolf isotopic response.

This concept was originally described by Wyburn-Mason in 19551 and later revived by Wolf et al.2 Wolf isotopic response describes the development of dermatologic disorders that localize to a site of another distinct and clinically healed skin disorder. Originally, it was reserved for infections, malignancies, and immune conditions restricted to a site of a prior herpetic infection but recently has been expanded to encompass other primary nonherpesvirus-related skin disorders. The pathophysiology behind this phenomenon is unknown but thought to be the interplay of several key elements including immune dysregulation, neural, vascular, and locus minoris resistentiae (ie, a site of lessened resistance).3 Immunosuppression is a known risk factor in the development of MCCs,4 thus the proposed local immune dysregulation within a scar may alter the virus-host balance and foster the oncogenic nature of the MCC polyomavirus. A recent article describes another case of an MCC arising within a sternotomy scar,5 lending further credibility to a skin vulnerability philosophy. These cases provide further insight into the pathomechanisms involved in the development of this rare and aggressive neoplasm and sheds light on an intriguing dermatologic phenomenon.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.

- Wyburn-Mason R. Malignant change arising in tissues affected by herpes. Br Med J. 1955;2:1106-1109.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukaemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:422-423.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Grippaudo FR, Costantino B, Santanelli F. Merkel cell carcinoma on a sternotomy scar: atypical clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:e22-e24.

Nonpruritic Papular Facial Eruption

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

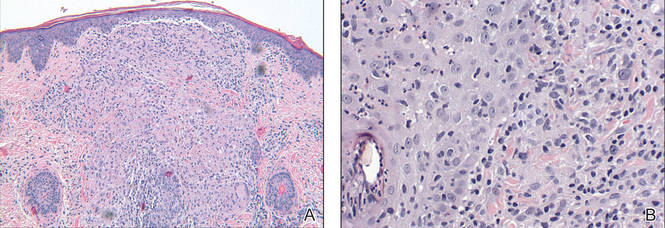

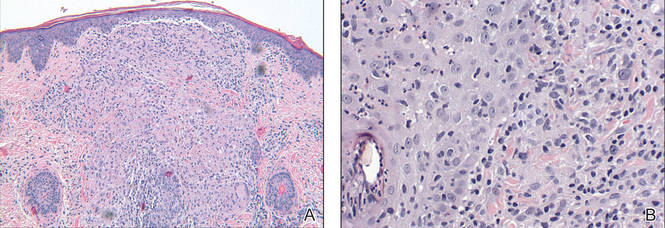

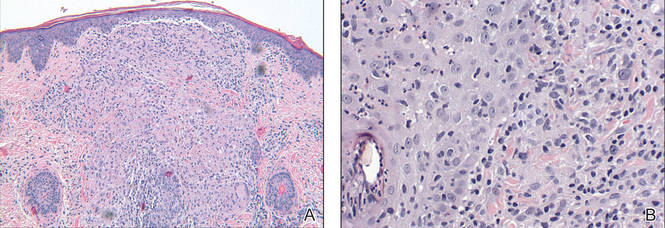

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis

Review of the prior biopsy from the lower cutaneous lip revealed granulomatous perifolliculitis. The patient’s age combined with the morphology, distribution, and histopathologic features (Figure) of his eruption were characteristic of granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD) of childhood. The patient was treated with oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole with immediate improvement, particularly with resolution of the erythema.

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is a benign, self-limited eruption in healthy prepubertal children that is characterized by coalescent, asymptomatic, dome-shaped, yellow-brown to erythematous papules.1,2 The monomorphous lesions are firm, measure 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and are most commonly located around the mouth.2,3 Other areas of involvement include the nostrils and alar creases as well as the periocular skin.4 Less commonly, GPD has been described on the scalp, ears, neck, trunk, extremities, and genital region.5 Slight peripheral scaling or erythema and small pitted scarring are variable.4,5 There may be a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment that either caused no change or a flare in the rash.1-5 Patients have no systemic findings.3,5

Biopsy of GPD shows characteristic noncaseating granulomas in the dermis, typified by perifollicular localization.5 The granulomatous infiltrate consists of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytes, with focal collections of neutrophils and occasionally overlying parakeratosis.2,3

The nomenclature of GPD has varied since the 1970s and has included Gianotti-type perioral dermatitis,6 GPD of childhood,7 rosacealike eruption in children,8 FACE (facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption),9 and sarcoidlike granulomatous dermatitis.10

The etiology of GPD is unknown, though it has been associated with use of topical, inhaled, or systemic steroids; a personal history of skin problems; a family history of atopy; vaccination; and local reactions to allergens such as cosmetic preparations, antiseptic solutions, tartar control toothpaste, and bubble gum.4,5,11-13 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis may represent a pediatric variant of granulomatous rosacea or a granulomatous variant of perioral dermatitis, but importantly, it is not related to sarcoidosis.1,4,5 Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis typically affects children of dark-skinned, African Caribbean ancestry, though it has been described in both white and Asian populations.1,2,5 Genders are equally affected.

Although generally a benign condition that spontaneously remits within a few months to 3 years,5 GPD can be quite disruptive to a patient’s self-image, necessitating therapy to hasten resolution. Prior to initiation of treatment, any topical corticosteroids being applied to the affected region should be discontinued. For children older than 9 years, a suggested regimen is oral tetracycline 250 mg twice daily; for those younger than 9 years, erythromycin 30 to 40 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses is advised.14 Metronidazole 0.75% cream and gel also have shown efficacy in GPD and represent a topical adjunct or alternative to oral therapy.1,14,15

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134.

- Choi YL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol. 2006;33:806-808.

- Tarm K, Creel NB, Krivda SJ, et al. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:399-402.

- Nguyen V, Eichenfield LF. Periorificial dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:781-785.

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358.

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Bennelli MG, et al. Particuliere dermatite peri-orale infantile: observations sur cinq cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1970;77:341.

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Savin JA, Alexander S, Marks R. A rosacea-like eruption of children. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:425-429.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual popular and acneiform facial eruption in the Negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438.

- Falk ES. Sarcoid-like granulomatous periocular dermatitis treated with tetracycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:270-272.

- Hafeez ZH. Perioral dermatitis: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:514-517.

- Ferlito TA. Tartar-control toothpaste and perioral dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;27:43-44.

- Georgouras K, Kocsard E. Micropapular sarcoidal facial eruption in a child. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;48:433-436.

- Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18:206-209.

- Miller SR, Shalita AR. Topical metronidazole gel (0.75%) for the treatment of perioral dermatitis in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:847-848.

A 7-year-old boy was referred to the dermatology department with a red, bumpy, nonpruritic facial rash of 6 months’ duration. There was no identifiable trigger. The lesions were grouped around the nose and mouth with some extension onto the neck. He was treated with pimecrolimus cream 1% for presumed atopic dermatitis with good response, but the rash recurred soon thereafter. A biopsy performed at an outside institution shortly after rash onset showed dermal granulomas, leading to a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (lupus pernio). Prior to presenting to our clinic, treatment with topical and oral corticosteroids failed. He had a normal chest radiograph, ophthalmologic examination, and angiotensin-converting enzyme level to exclude extracutaneous sarcoidosis. On physical examination the patient had innumerable, monomorphic, flesh-colored to erythematous papules confluent over the medial eyelids and canthi, perinasal skin, cutaneous lips, and preauricular skin extending onto the lateral aspect of the neck. There was superimposed scale around the mouth.