User login

A complication of enoxaparin injection

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

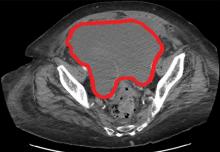

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

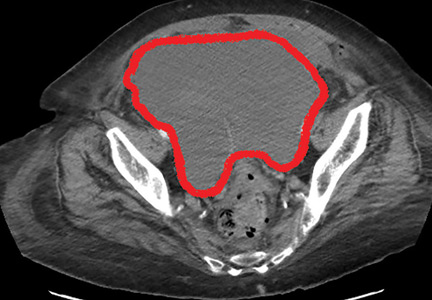

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

In reply: Gastroparesis

In Reply: We thank the readers for their letter. Our patient’s laboratory values at the time of presentation were as follows:

- Corrected sodium 142 mmol/L

- Potassium 5.5 mmol/L

- Phosphorus 6.6 mmol/L.

The rest of the electrolyte levels were within normal limits.

These reported electrolyte levels were unlikely to cause such gastroparesis. The patient’s hemoglobin A1c was 8.7% at the time of presentation, with no previous values available. However, since abdominal computed tomography done 1 year before this presentation did not show stomach dilation and the patient was asymptomatic, his gastroparesis was presumed to be acute.

In Reply: We thank the readers for their letter. Our patient’s laboratory values at the time of presentation were as follows:

- Corrected sodium 142 mmol/L

- Potassium 5.5 mmol/L

- Phosphorus 6.6 mmol/L.

The rest of the electrolyte levels were within normal limits.

These reported electrolyte levels were unlikely to cause such gastroparesis. The patient’s hemoglobin A1c was 8.7% at the time of presentation, with no previous values available. However, since abdominal computed tomography done 1 year before this presentation did not show stomach dilation and the patient was asymptomatic, his gastroparesis was presumed to be acute.

In Reply: We thank the readers for their letter. Our patient’s laboratory values at the time of presentation were as follows:

- Corrected sodium 142 mmol/L

- Potassium 5.5 mmol/L

- Phosphorus 6.6 mmol/L.

The rest of the electrolyte levels were within normal limits.

These reported electrolyte levels were unlikely to cause such gastroparesis. The patient’s hemoglobin A1c was 8.7% at the time of presentation, with no previous values available. However, since abdominal computed tomography done 1 year before this presentation did not show stomach dilation and the patient was asymptomatic, his gastroparesis was presumed to be acute.

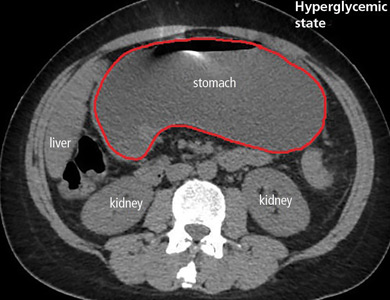

Gastroparesis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

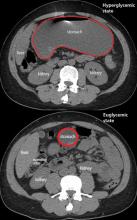

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693