User login

Blood cancer patients, survivors hesitate over COVID-19 vaccine

Nearly one in three patients with blood cancer, and survivors, say they are unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine or unsure about getting it if one were available. The findings come from a nationwide survey by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which collected 6,517 responses.

“These findings are worrisome, to say the least,” Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the society, said in a statement.

“We know cancer patients – and blood cancer patients in particular – are susceptible to the worst effects of the virus [and] all of us in the medical community need to help cancer patients understand the importance of getting vaccinated,” she added.

The survey – the largest ever done in which cancer patients and survivors were asked about their attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines – was published online March 8 by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Survey sample

The survey asked patients with blood cancer, and survivors, about their attitudes regarding COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines.

“The main outcome [was] vaccine attitudes,” noted the authors, headed by Rena Conti, PhD, dean’s research scholar, Boston University.

Respondents were asked: “How likely are you to choose to get the vaccine?” Participants could indicate they were very unlikely, unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, likely, or very likely to get vaccinated.

“We found that 17% of respondents indicate[d] that they [were] unlikely or very unlikely to take a vaccine,” Dr. Conti and colleagues observed.

Among the 17% – deemed to be “vaccine hesitant” – slightly over half (54%) stated they had concerns about the side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccination and believed neither of the two newly approved vaccines had been or would ever be tested properly.

The survey authors noted that there is no reason to believe COVID-19 vaccines are any less safe in patients with blood cancers, but concerns have been expressed that patients with some forms of blood cancer or those undergoing certain treatments may not achieve the same immune response to the vaccine as would noncancer controls.

Importantly, the survey was conducted Dec. 1-21, 2020, and responses differed depending on whether respondents answered the survey before or after the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines had been given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration starting Dec. 10, 2020.

There was a slight increase in positive responses after the vaccines were granted regulatory approval. (One-third of those who responded to the survey after the approval were 3.7% more likely to indicate they would get vaccinated). “This suggests that hesitancy may be influenced by emerging information dissemination, government action, and vaccine availability, transforming the hypothetical opportunity of vaccination to a real one,” the survey authors speculated.

Survey respondents who were vaccine hesitant were also over 14% more likely to indicate that they didn’t think they would require hospitalization should they contract COVID-19. But clinical data have suggested that approximately half of patients with a hematological malignancy who required hospitalization for COVID-19 die from the infection, the authors noted.

“Vaccine hesitant respondents [were] also significantly less likely to engage in protective health behaviors,” the survey authors pointed out. For example, they were almost 4% less likely to have worn a face mask and 1.6% less likely to have taken other protective measures to guard against COVID-19 infection.

Need for clear messaging

To counter vaccine hesitancy, the authors suggest there is a need for clear, consistent messaging targeting patients with cancer that emphasize the risks of COVID-19 and underscore vaccine benefits.

Dr. Conti pointed out that patients with blood cancer are, in fact, being given preferential access to vaccines in many communities, although this clearly doesn’t mean patients are willing to get vaccinated, as she also noted.

“We need both adequate supply and strong demand to keep this vulnerable population safe,” Dr. Conti emphasized.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society plans to repeat the survey in the near future to assess patients’ and survivors’ access to vaccines as well as their willingness to get vaccinated.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly one in three patients with blood cancer, and survivors, say they are unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine or unsure about getting it if one were available. The findings come from a nationwide survey by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which collected 6,517 responses.

“These findings are worrisome, to say the least,” Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the society, said in a statement.

“We know cancer patients – and blood cancer patients in particular – are susceptible to the worst effects of the virus [and] all of us in the medical community need to help cancer patients understand the importance of getting vaccinated,” she added.

The survey – the largest ever done in which cancer patients and survivors were asked about their attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines – was published online March 8 by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Survey sample

The survey asked patients with blood cancer, and survivors, about their attitudes regarding COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines.

“The main outcome [was] vaccine attitudes,” noted the authors, headed by Rena Conti, PhD, dean’s research scholar, Boston University.

Respondents were asked: “How likely are you to choose to get the vaccine?” Participants could indicate they were very unlikely, unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, likely, or very likely to get vaccinated.

“We found that 17% of respondents indicate[d] that they [were] unlikely or very unlikely to take a vaccine,” Dr. Conti and colleagues observed.

Among the 17% – deemed to be “vaccine hesitant” – slightly over half (54%) stated they had concerns about the side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccination and believed neither of the two newly approved vaccines had been or would ever be tested properly.

The survey authors noted that there is no reason to believe COVID-19 vaccines are any less safe in patients with blood cancers, but concerns have been expressed that patients with some forms of blood cancer or those undergoing certain treatments may not achieve the same immune response to the vaccine as would noncancer controls.

Importantly, the survey was conducted Dec. 1-21, 2020, and responses differed depending on whether respondents answered the survey before or after the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines had been given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration starting Dec. 10, 2020.

There was a slight increase in positive responses after the vaccines were granted regulatory approval. (One-third of those who responded to the survey after the approval were 3.7% more likely to indicate they would get vaccinated). “This suggests that hesitancy may be influenced by emerging information dissemination, government action, and vaccine availability, transforming the hypothetical opportunity of vaccination to a real one,” the survey authors speculated.

Survey respondents who were vaccine hesitant were also over 14% more likely to indicate that they didn’t think they would require hospitalization should they contract COVID-19. But clinical data have suggested that approximately half of patients with a hematological malignancy who required hospitalization for COVID-19 die from the infection, the authors noted.

“Vaccine hesitant respondents [were] also significantly less likely to engage in protective health behaviors,” the survey authors pointed out. For example, they were almost 4% less likely to have worn a face mask and 1.6% less likely to have taken other protective measures to guard against COVID-19 infection.

Need for clear messaging

To counter vaccine hesitancy, the authors suggest there is a need for clear, consistent messaging targeting patients with cancer that emphasize the risks of COVID-19 and underscore vaccine benefits.

Dr. Conti pointed out that patients with blood cancer are, in fact, being given preferential access to vaccines in many communities, although this clearly doesn’t mean patients are willing to get vaccinated, as she also noted.

“We need both adequate supply and strong demand to keep this vulnerable population safe,” Dr. Conti emphasized.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society plans to repeat the survey in the near future to assess patients’ and survivors’ access to vaccines as well as their willingness to get vaccinated.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly one in three patients with blood cancer, and survivors, say they are unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine or unsure about getting it if one were available. The findings come from a nationwide survey by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, which collected 6,517 responses.

“These findings are worrisome, to say the least,” Gwen Nichols, MD, chief medical officer of the society, said in a statement.

“We know cancer patients – and blood cancer patients in particular – are susceptible to the worst effects of the virus [and] all of us in the medical community need to help cancer patients understand the importance of getting vaccinated,” she added.

The survey – the largest ever done in which cancer patients and survivors were asked about their attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines – was published online March 8 by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Survey sample

The survey asked patients with blood cancer, and survivors, about their attitudes regarding COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines.

“The main outcome [was] vaccine attitudes,” noted the authors, headed by Rena Conti, PhD, dean’s research scholar, Boston University.

Respondents were asked: “How likely are you to choose to get the vaccine?” Participants could indicate they were very unlikely, unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, likely, or very likely to get vaccinated.

“We found that 17% of respondents indicate[d] that they [were] unlikely or very unlikely to take a vaccine,” Dr. Conti and colleagues observed.

Among the 17% – deemed to be “vaccine hesitant” – slightly over half (54%) stated they had concerns about the side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccination and believed neither of the two newly approved vaccines had been or would ever be tested properly.

The survey authors noted that there is no reason to believe COVID-19 vaccines are any less safe in patients with blood cancers, but concerns have been expressed that patients with some forms of blood cancer or those undergoing certain treatments may not achieve the same immune response to the vaccine as would noncancer controls.

Importantly, the survey was conducted Dec. 1-21, 2020, and responses differed depending on whether respondents answered the survey before or after the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines had been given emergency use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration starting Dec. 10, 2020.

There was a slight increase in positive responses after the vaccines were granted regulatory approval. (One-third of those who responded to the survey after the approval were 3.7% more likely to indicate they would get vaccinated). “This suggests that hesitancy may be influenced by emerging information dissemination, government action, and vaccine availability, transforming the hypothetical opportunity of vaccination to a real one,” the survey authors speculated.

Survey respondents who were vaccine hesitant were also over 14% more likely to indicate that they didn’t think they would require hospitalization should they contract COVID-19. But clinical data have suggested that approximately half of patients with a hematological malignancy who required hospitalization for COVID-19 die from the infection, the authors noted.

“Vaccine hesitant respondents [were] also significantly less likely to engage in protective health behaviors,” the survey authors pointed out. For example, they were almost 4% less likely to have worn a face mask and 1.6% less likely to have taken other protective measures to guard against COVID-19 infection.

Need for clear messaging

To counter vaccine hesitancy, the authors suggest there is a need for clear, consistent messaging targeting patients with cancer that emphasize the risks of COVID-19 and underscore vaccine benefits.

Dr. Conti pointed out that patients with blood cancer are, in fact, being given preferential access to vaccines in many communities, although this clearly doesn’t mean patients are willing to get vaccinated, as she also noted.

“We need both adequate supply and strong demand to keep this vulnerable population safe,” Dr. Conti emphasized.

The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society plans to repeat the survey in the near future to assess patients’ and survivors’ access to vaccines as well as their willingness to get vaccinated.

The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACG: CRC screening should start at age 45

The starting age was previously 50 years for most patients. However, for Black patients, the starting age was lowered to 45 years in 2005.

The new guidance brings the ACG in line with recommendations of the American Cancer Society, which lowered the starting age to 45 years for average-risk individuals in 2018.

However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Multi-Specialty Task Force, and the American College of Physicians still recommend that CRC screening begin at the age of 50.

The new ACG guideline were published in March 2021 in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. The last time they were updated was in 2009.

The ACG said that the move was made in light of reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in adults younger than 50.

“It has been estimated that [in the United States] persons born around 1990 have twice the risk of colon cancer and four times the risk of rectal cancer, compared with those born around 1950,” guideline author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues pointed out.

“The fact that other developed countries are reporting similar increases in early-onset CRC and birth-cohort effects suggests that the Western lifestyle (especially exemplified by the obesity epidemic) is a significant contributor,” the authors added.

The new ACG guideline emphasize the importance of initiating CRC screening for average-risk patients aged 50-75 years. “Given that current rates of screening uptake are close to 60% (57.9% ages 50-64 and 62.4% ages 50-75), expanding the population to be screened may reduce these rates as emphasis shifts to screening 45- to 49-year-olds at the expense of efforts to screen the unscreened 50- to 75-year-olds,” the authors commented.

Now, however, the guideline suggests that the decision to continue screening after age 75 should be individualized. It notes that the benefits of screening are limited for those who are not expected to live for another 7-10 years. For patients with a family history of CRC, the guideline authors recommended initiating CRC screening at the age of 40 for patients with one or two first-degree relatives with either CRC or advanced colorectal polyps.

They also recommend screening colonoscopy over any other screening modality if the first-degree relative is younger than 60 or if two or more first-degree relatives of any age have CRC or advanced colorectal polyps. For such patients, screening should be repeated every 5 years.

For screening average-risk individuals, either colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is recommended. If colonoscopy is used, it should be repeated every 10 years. FIT should be conducted on an annual basis.

This is somewhat in contrast to recent changes proposed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The AGA recommends greater use of noninvasive testing, such as with fecal occult blood tests, initially. It recommends that initial colonoscopy be used only for patients at high risk for CRC.

For individuals unwilling or unable to undergo colonoscopy or FIT, the ACG suggests flexible sigmoidoscopy, multitarget stool DNA testing, CT colonography, or colon capsule. Only colonoscopy is a single-step test; all other screening modalities require a follow-up colonoscopy if test results are positive.

“We recommend against the use of aspirin as a substitute for CRC screening,” the ACG members emphasized. Rather, they suggest that the use of low-dose aspirin be considered only for patients aged 50-69 years whose risk for cardiovascular disease over the next 10 years is at least 10% and who are at low risk for bleeding.

To reduce their risk for CRC, patients need to take aspirin for at least 10 years, they pointed out.

Quality indicators

For endoscopists who perform colonoscopy, the ACG recommended that all operators determine their individual cecal intubation rates, adenoma detection rates, and withdrawal times. They also recommended that endoscopists spend at least 6 minutes inspecting the mucosa during withdrawal and achieve a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for all patients screened.

The ACG recommended remedial training for any provider whose adenoma detection rate is less than 25%.

Screening rates dropped during pandemic

The authors of the new recommendations also pointed out that, despite public health initiatives to boost CRC screening in the United States and the availability of multiple screening modalities, almost one-third of individuals who are eligible for CRC screening do not undergo screening.

Moreover, the proportion of individuals not being screened has reportedly increased during the pandemic. In one report, claims data for colonoscopies dropped by 90% during April. “Colorectal cancer screening rates must be optimized to reach the aspirational target of >80%,” the authors emphasized.

“A recommendation to be screened by a PCP [primary care provider] – who is known and trusted by the person – is clearly effective in raising participation,” they added.

Dr. Shaukat has served as a scientific consultant for Iterative Scopes and Freenome. Other ACG guideline authors reported numerous financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The starting age was previously 50 years for most patients. However, for Black patients, the starting age was lowered to 45 years in 2005.

The new guidance brings the ACG in line with recommendations of the American Cancer Society, which lowered the starting age to 45 years for average-risk individuals in 2018.

However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Multi-Specialty Task Force, and the American College of Physicians still recommend that CRC screening begin at the age of 50.

The new ACG guideline were published in March 2021 in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. The last time they were updated was in 2009.

The ACG said that the move was made in light of reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in adults younger than 50.

“It has been estimated that [in the United States] persons born around 1990 have twice the risk of colon cancer and four times the risk of rectal cancer, compared with those born around 1950,” guideline author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues pointed out.

“The fact that other developed countries are reporting similar increases in early-onset CRC and birth-cohort effects suggests that the Western lifestyle (especially exemplified by the obesity epidemic) is a significant contributor,” the authors added.

The new ACG guideline emphasize the importance of initiating CRC screening for average-risk patients aged 50-75 years. “Given that current rates of screening uptake are close to 60% (57.9% ages 50-64 and 62.4% ages 50-75), expanding the population to be screened may reduce these rates as emphasis shifts to screening 45- to 49-year-olds at the expense of efforts to screen the unscreened 50- to 75-year-olds,” the authors commented.

Now, however, the guideline suggests that the decision to continue screening after age 75 should be individualized. It notes that the benefits of screening are limited for those who are not expected to live for another 7-10 years. For patients with a family history of CRC, the guideline authors recommended initiating CRC screening at the age of 40 for patients with one or two first-degree relatives with either CRC or advanced colorectal polyps.

They also recommend screening colonoscopy over any other screening modality if the first-degree relative is younger than 60 or if two or more first-degree relatives of any age have CRC or advanced colorectal polyps. For such patients, screening should be repeated every 5 years.

For screening average-risk individuals, either colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is recommended. If colonoscopy is used, it should be repeated every 10 years. FIT should be conducted on an annual basis.

This is somewhat in contrast to recent changes proposed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The AGA recommends greater use of noninvasive testing, such as with fecal occult blood tests, initially. It recommends that initial colonoscopy be used only for patients at high risk for CRC.

For individuals unwilling or unable to undergo colonoscopy or FIT, the ACG suggests flexible sigmoidoscopy, multitarget stool DNA testing, CT colonography, or colon capsule. Only colonoscopy is a single-step test; all other screening modalities require a follow-up colonoscopy if test results are positive.

“We recommend against the use of aspirin as a substitute for CRC screening,” the ACG members emphasized. Rather, they suggest that the use of low-dose aspirin be considered only for patients aged 50-69 years whose risk for cardiovascular disease over the next 10 years is at least 10% and who are at low risk for bleeding.

To reduce their risk for CRC, patients need to take aspirin for at least 10 years, they pointed out.

Quality indicators

For endoscopists who perform colonoscopy, the ACG recommended that all operators determine their individual cecal intubation rates, adenoma detection rates, and withdrawal times. They also recommended that endoscopists spend at least 6 minutes inspecting the mucosa during withdrawal and achieve a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for all patients screened.

The ACG recommended remedial training for any provider whose adenoma detection rate is less than 25%.

Screening rates dropped during pandemic

The authors of the new recommendations also pointed out that, despite public health initiatives to boost CRC screening in the United States and the availability of multiple screening modalities, almost one-third of individuals who are eligible for CRC screening do not undergo screening.

Moreover, the proportion of individuals not being screened has reportedly increased during the pandemic. In one report, claims data for colonoscopies dropped by 90% during April. “Colorectal cancer screening rates must be optimized to reach the aspirational target of >80%,” the authors emphasized.

“A recommendation to be screened by a PCP [primary care provider] – who is known and trusted by the person – is clearly effective in raising participation,” they added.

Dr. Shaukat has served as a scientific consultant for Iterative Scopes and Freenome. Other ACG guideline authors reported numerous financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The starting age was previously 50 years for most patients. However, for Black patients, the starting age was lowered to 45 years in 2005.

The new guidance brings the ACG in line with recommendations of the American Cancer Society, which lowered the starting age to 45 years for average-risk individuals in 2018.

However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Multi-Specialty Task Force, and the American College of Physicians still recommend that CRC screening begin at the age of 50.

The new ACG guideline were published in March 2021 in the American Journal of Gastroenterology. The last time they were updated was in 2009.

The ACG said that the move was made in light of reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in adults younger than 50.

“It has been estimated that [in the United States] persons born around 1990 have twice the risk of colon cancer and four times the risk of rectal cancer, compared with those born around 1950,” guideline author Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues pointed out.

“The fact that other developed countries are reporting similar increases in early-onset CRC and birth-cohort effects suggests that the Western lifestyle (especially exemplified by the obesity epidemic) is a significant contributor,” the authors added.

The new ACG guideline emphasize the importance of initiating CRC screening for average-risk patients aged 50-75 years. “Given that current rates of screening uptake are close to 60% (57.9% ages 50-64 and 62.4% ages 50-75), expanding the population to be screened may reduce these rates as emphasis shifts to screening 45- to 49-year-olds at the expense of efforts to screen the unscreened 50- to 75-year-olds,” the authors commented.

Now, however, the guideline suggests that the decision to continue screening after age 75 should be individualized. It notes that the benefits of screening are limited for those who are not expected to live for another 7-10 years. For patients with a family history of CRC, the guideline authors recommended initiating CRC screening at the age of 40 for patients with one or two first-degree relatives with either CRC or advanced colorectal polyps.

They also recommend screening colonoscopy over any other screening modality if the first-degree relative is younger than 60 or if two or more first-degree relatives of any age have CRC or advanced colorectal polyps. For such patients, screening should be repeated every 5 years.

For screening average-risk individuals, either colonoscopy or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is recommended. If colonoscopy is used, it should be repeated every 10 years. FIT should be conducted on an annual basis.

This is somewhat in contrast to recent changes proposed by the American Gastroenterological Association. The AGA recommends greater use of noninvasive testing, such as with fecal occult blood tests, initially. It recommends that initial colonoscopy be used only for patients at high risk for CRC.

For individuals unwilling or unable to undergo colonoscopy or FIT, the ACG suggests flexible sigmoidoscopy, multitarget stool DNA testing, CT colonography, or colon capsule. Only colonoscopy is a single-step test; all other screening modalities require a follow-up colonoscopy if test results are positive.

“We recommend against the use of aspirin as a substitute for CRC screening,” the ACG members emphasized. Rather, they suggest that the use of low-dose aspirin be considered only for patients aged 50-69 years whose risk for cardiovascular disease over the next 10 years is at least 10% and who are at low risk for bleeding.

To reduce their risk for CRC, patients need to take aspirin for at least 10 years, they pointed out.

Quality indicators

For endoscopists who perform colonoscopy, the ACG recommended that all operators determine their individual cecal intubation rates, adenoma detection rates, and withdrawal times. They also recommended that endoscopists spend at least 6 minutes inspecting the mucosa during withdrawal and achieve a cecal intubation rate of at least 95% for all patients screened.

The ACG recommended remedial training for any provider whose adenoma detection rate is less than 25%.

Screening rates dropped during pandemic

The authors of the new recommendations also pointed out that, despite public health initiatives to boost CRC screening in the United States and the availability of multiple screening modalities, almost one-third of individuals who are eligible for CRC screening do not undergo screening.

Moreover, the proportion of individuals not being screened has reportedly increased during the pandemic. In one report, claims data for colonoscopies dropped by 90% during April. “Colorectal cancer screening rates must be optimized to reach the aspirational target of >80%,” the authors emphasized.

“A recommendation to be screened by a PCP [primary care provider] – who is known and trusted by the person – is clearly effective in raising participation,” they added.

Dr. Shaukat has served as a scientific consultant for Iterative Scopes and Freenome. Other ACG guideline authors reported numerous financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

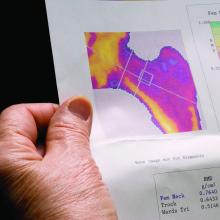

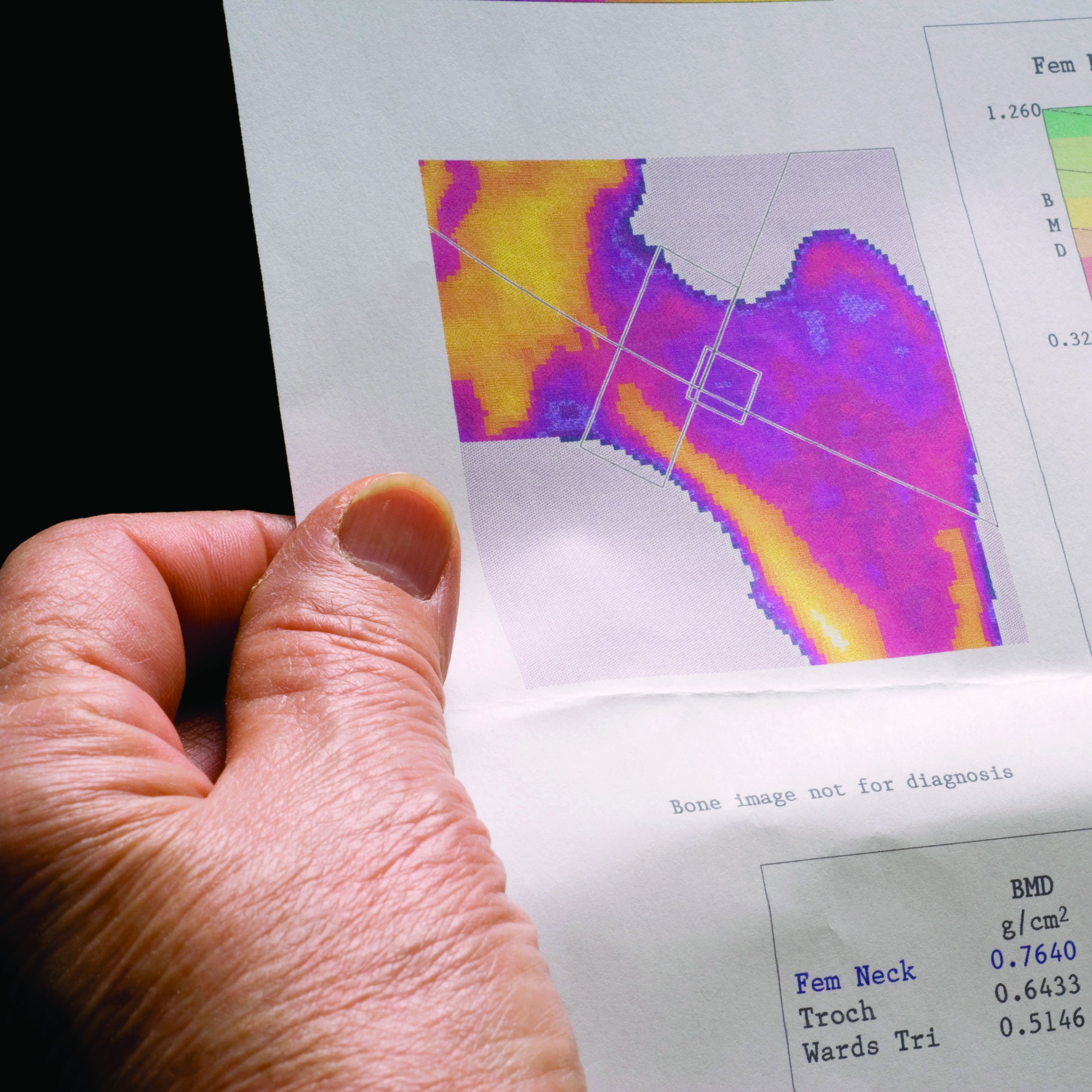

Bone loss common in kidney stone patients, yet rarely detected

Almost one in four men and women diagnosed with kidney stones have osteoporosis or a history of fracture at the time of their diagnosis, yet fewer than 10% undergo bone mineral density (BMD) screening, a retrospective analysis of a Veterans Health Administration database shows.

Because the majority of those analyzed in the VA dataset were men, this means that middle-aged and older men with kidney stones have about the same risk for osteoporosis as postmenopausal women do, but BMD screening for such men is not currently recommended, the study notes.

“These findings suggest that the risk of osteoporosis or fractures in patients with kidney stone disease is not restricted to postmenopausal women but is also observed in men, a group that is less well recognized to be at risk,” Calyani Ganesan, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues say in their article, published online March 3 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“We hope this work raises awareness regarding the possibility of reduced bone strength in patients with kidney stones, [and] in our future work, we hope to identify which patients with kidney stones are at higher risk for osteoporosis or fracture to help guide bone density screening efforts by clinicians in this population,” Dr. Ganesan added in a statement.

VA dataset: Just 9.1% had DXA after kidney stone diagnosed

A total of 531,431 patients with a history of kidney stone disease were identified in the VA dataset. Of these, 23.6% either had been diagnosed with osteoporosis or had a history of fracture around the time of their kidney stone diagnosis. The most common diagnosis was a non-hip fracture, seen in 19% of patients, Dr. Ganesan and colleagues note, followed by osteoporosis in 6.1%, and hip fracture in 2.1%.

The mean age of the patients who concurrently had received a diagnosis of kidney stone disease and osteoporosis or had a fracture history was 64.2 years. In this cohort, more than 91% were men. The majority of the patients were White.

Among some 462,681 patients who had no prior history of either osteoporosis or fracture before their diagnosis of kidney stones, only 9.1% had undergone dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening for BMD in the 5 years after their kidney stone diagnosis.

“Of those who completed DXA ... 20% were subsequently diagnosed with osteoporosis,” the authors note – 19% with non-hip fracture, and 2.4% with hip fracture.

Importantly, 85% of patients with kidney stone disease who were screened with DXA and were later diagnosed with osteoporosis were men.

“Given that almost 20% of patients in our cohort had a non-hip fracture, we contend that osteoporosis is underdiagnosed and undertreated in older men with kidney stone disease,” the authors stress.

Perform DXA screen in older men, even in absence of hypercalciuria

The authors also explain that the most common metabolic abnormality associated with kidney stones is high urine calcium excretion, or hypercalciuria.

“In a subset of patients with kidney stones, dysregulated calcium homeostasis may be present in which calcium is resorbed from bone and excreted into the urine, which can lead to osteoporosis and the formation of calcium stones,” they explain.

However, when they carried out a 24-hour assessment of urine calcium excretion on a small subset of patients with kidney stones, “we found no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion,” they point out.

Even when the authors excluded patients who were taking a thiazide diuretic – a class of drugs that decreases urine calcium excretion – there was no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion.

The investigators suggest it is possible that, in the majority of patients with kidney stones, the cause of hypercalciuria is more closely related to overabsorption of calcium from the gut, not to overresorption of calcium from the bone.

“Nonetheless, our findings indicate that patients with kidney stone disease could benefit from DXA screening even in the absence of hypercalciuria,” they state.

“And our findings provide support for wider use of bone mineral density screening in patients with kidney stone disease, including middle-aged and older men, for whom efforts to mitigate risks of osteoporosis and fractures are not commonly emphasized,” they reaffirm.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost one in four men and women diagnosed with kidney stones have osteoporosis or a history of fracture at the time of their diagnosis, yet fewer than 10% undergo bone mineral density (BMD) screening, a retrospective analysis of a Veterans Health Administration database shows.

Because the majority of those analyzed in the VA dataset were men, this means that middle-aged and older men with kidney stones have about the same risk for osteoporosis as postmenopausal women do, but BMD screening for such men is not currently recommended, the study notes.

“These findings suggest that the risk of osteoporosis or fractures in patients with kidney stone disease is not restricted to postmenopausal women but is also observed in men, a group that is less well recognized to be at risk,” Calyani Ganesan, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues say in their article, published online March 3 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“We hope this work raises awareness regarding the possibility of reduced bone strength in patients with kidney stones, [and] in our future work, we hope to identify which patients with kidney stones are at higher risk for osteoporosis or fracture to help guide bone density screening efforts by clinicians in this population,” Dr. Ganesan added in a statement.

VA dataset: Just 9.1% had DXA after kidney stone diagnosed

A total of 531,431 patients with a history of kidney stone disease were identified in the VA dataset. Of these, 23.6% either had been diagnosed with osteoporosis or had a history of fracture around the time of their kidney stone diagnosis. The most common diagnosis was a non-hip fracture, seen in 19% of patients, Dr. Ganesan and colleagues note, followed by osteoporosis in 6.1%, and hip fracture in 2.1%.

The mean age of the patients who concurrently had received a diagnosis of kidney stone disease and osteoporosis or had a fracture history was 64.2 years. In this cohort, more than 91% were men. The majority of the patients were White.

Among some 462,681 patients who had no prior history of either osteoporosis or fracture before their diagnosis of kidney stones, only 9.1% had undergone dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening for BMD in the 5 years after their kidney stone diagnosis.

“Of those who completed DXA ... 20% were subsequently diagnosed with osteoporosis,” the authors note – 19% with non-hip fracture, and 2.4% with hip fracture.

Importantly, 85% of patients with kidney stone disease who were screened with DXA and were later diagnosed with osteoporosis were men.

“Given that almost 20% of patients in our cohort had a non-hip fracture, we contend that osteoporosis is underdiagnosed and undertreated in older men with kidney stone disease,” the authors stress.

Perform DXA screen in older men, even in absence of hypercalciuria

The authors also explain that the most common metabolic abnormality associated with kidney stones is high urine calcium excretion, or hypercalciuria.

“In a subset of patients with kidney stones, dysregulated calcium homeostasis may be present in which calcium is resorbed from bone and excreted into the urine, which can lead to osteoporosis and the formation of calcium stones,” they explain.

However, when they carried out a 24-hour assessment of urine calcium excretion on a small subset of patients with kidney stones, “we found no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion,” they point out.

Even when the authors excluded patients who were taking a thiazide diuretic – a class of drugs that decreases urine calcium excretion – there was no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion.

The investigators suggest it is possible that, in the majority of patients with kidney stones, the cause of hypercalciuria is more closely related to overabsorption of calcium from the gut, not to overresorption of calcium from the bone.

“Nonetheless, our findings indicate that patients with kidney stone disease could benefit from DXA screening even in the absence of hypercalciuria,” they state.

“And our findings provide support for wider use of bone mineral density screening in patients with kidney stone disease, including middle-aged and older men, for whom efforts to mitigate risks of osteoporosis and fractures are not commonly emphasized,” they reaffirm.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost one in four men and women diagnosed with kidney stones have osteoporosis or a history of fracture at the time of their diagnosis, yet fewer than 10% undergo bone mineral density (BMD) screening, a retrospective analysis of a Veterans Health Administration database shows.

Because the majority of those analyzed in the VA dataset were men, this means that middle-aged and older men with kidney stones have about the same risk for osteoporosis as postmenopausal women do, but BMD screening for such men is not currently recommended, the study notes.

“These findings suggest that the risk of osteoporosis or fractures in patients with kidney stone disease is not restricted to postmenopausal women but is also observed in men, a group that is less well recognized to be at risk,” Calyani Ganesan, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues say in their article, published online March 3 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“We hope this work raises awareness regarding the possibility of reduced bone strength in patients with kidney stones, [and] in our future work, we hope to identify which patients with kidney stones are at higher risk for osteoporosis or fracture to help guide bone density screening efforts by clinicians in this population,” Dr. Ganesan added in a statement.

VA dataset: Just 9.1% had DXA after kidney stone diagnosed

A total of 531,431 patients with a history of kidney stone disease were identified in the VA dataset. Of these, 23.6% either had been diagnosed with osteoporosis or had a history of fracture around the time of their kidney stone diagnosis. The most common diagnosis was a non-hip fracture, seen in 19% of patients, Dr. Ganesan and colleagues note, followed by osteoporosis in 6.1%, and hip fracture in 2.1%.

The mean age of the patients who concurrently had received a diagnosis of kidney stone disease and osteoporosis or had a fracture history was 64.2 years. In this cohort, more than 91% were men. The majority of the patients were White.

Among some 462,681 patients who had no prior history of either osteoporosis or fracture before their diagnosis of kidney stones, only 9.1% had undergone dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening for BMD in the 5 years after their kidney stone diagnosis.

“Of those who completed DXA ... 20% were subsequently diagnosed with osteoporosis,” the authors note – 19% with non-hip fracture, and 2.4% with hip fracture.

Importantly, 85% of patients with kidney stone disease who were screened with DXA and were later diagnosed with osteoporosis were men.

“Given that almost 20% of patients in our cohort had a non-hip fracture, we contend that osteoporosis is underdiagnosed and undertreated in older men with kidney stone disease,” the authors stress.

Perform DXA screen in older men, even in absence of hypercalciuria

The authors also explain that the most common metabolic abnormality associated with kidney stones is high urine calcium excretion, or hypercalciuria.

“In a subset of patients with kidney stones, dysregulated calcium homeostasis may be present in which calcium is resorbed from bone and excreted into the urine, which can lead to osteoporosis and the formation of calcium stones,” they explain.

However, when they carried out a 24-hour assessment of urine calcium excretion on a small subset of patients with kidney stones, “we found no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion,” they point out.

Even when the authors excluded patients who were taking a thiazide diuretic – a class of drugs that decreases urine calcium excretion – there was no correlation between osteoporosis and the level of 24-hour urine calcium excretion.

The investigators suggest it is possible that, in the majority of patients with kidney stones, the cause of hypercalciuria is more closely related to overabsorption of calcium from the gut, not to overresorption of calcium from the bone.

“Nonetheless, our findings indicate that patients with kidney stone disease could benefit from DXA screening even in the absence of hypercalciuria,” they state.

“And our findings provide support for wider use of bone mineral density screening in patients with kidney stone disease, including middle-aged and older men, for whom efforts to mitigate risks of osteoporosis and fractures are not commonly emphasized,” they reaffirm.

The study was funded by the VA Merit Review and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Large study finds trans men on testosterone at risk for blood clots

Over 10% of transgender men (females transitioning to male) who take testosterone develop high hematocrit levels that could put them at greater risk for a thrombotic event, and the largest increase in levels occurs in the first year after starting therapy, a new Dutch study indicates.

Erythrocytosis, defined as a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L, is a potentially serious side effect of testosterone therapy, say Milou Cecilia Madsen, MD, and colleagues in their article published online Feb. 18, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

When hematocrit was measured twice, 11.1% of the cohort of 1073 trans men had levels in excess of 0.50 L/L over a 20-year follow-up.

“Erythrocytosis is common in transgender men treated with testosterone, especially in those who smoke, have [a] high BMI [body mass index], and [who] use testosterone injections,” Dr. Madsen, of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, said in a statement from the Endocrine Society.

“A reasonable first step in the care of transgender men with high red blood cells while on testosterone is to advise them to quit smoking, switch injectable testosterone to gel, and, if BMI is high, to lose weight,” she added.

First large study of testosterone in trans men with 20-year follow-up

Transgender men often undergo testosterone therapy as part of gender-affirming treatment.

Secondary erythrocytosis, a condition where the body makes too many red blood cells, is a common side effect of testosterone therapy that can increase the risk of thrombolic events, heart attack, and stroke, Dr. Madsen and colleagues explained.

This is the first study of a large cohort of trans men taking testosterone therapy followed for up to 20 years. Because of the large sample size, statistical analysis with many determinants could be performed. And because of the long follow-up, a clear time relation between initiation of testosterone therapy and hematocrit could be studied, they noted.

Participants were part of the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria study, a large cohort of individuals seen at the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Amsterdam University Medical Center between 1972 and 2015.

Laboratory measurements taken between 2004 and 2018 were available for analysis. Trans men visited the center every 3-6 months during their first year of testosterone therapy and were then monitored every year or every other year.

Long-acting undecanoate injection was associated with the highest risk of a hematocrit level greater than 0.50 L/L, and the risk of erythrocytosis in those who took long-acting intramuscular injections was about threefold higher, compared with testosterone gel (adjusted odds ratio, 3.1).

In contrast, short-acting ester injections and oral administration of testosterone had a similar risk for erythrocytosis, as did testosterone gel.

Other determinants of elevated hematocrit included smoking, medical history of a number of comorbid conditions, and older age on initiation of testosterone.

In contrast, “higher testosterone levels per se were not associated with an increased odds of hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L”, the authors noted.

Current advice for trans men based on old guidance for hypogonadism

The authors said that current advice for trans men is based on recommendations for testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men (those assigned male at birth) from 2008, which advises a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L has a moderate to high risk of adverse outcome. For levels greater than 0.54 L/L, cessation of testosterone therapy, a dose reduction, or therapeutic phlebotomy to reduce the risk of adverse events is advised. For levels 0.50-0.54 L/L, no clear advice is given.

But questions remain as to whether these guidelines are applicable to trans men because the duration of testosterone therapy is much longer in trans men and hormone treatment often cannot be discontinued without causing distress.

Meanwhile, hematology guidelines indicate an upper limit for hematocrit for cis females of 0.48 L/L.

“It could be argued that the upper limit for cis females should be applied, as trans men are born with female genetics,” the authors said. “This is a subject for further research.”

Duration of testosterone therapy impacts risk of erythrocytosis

In the study, the researchers found that longer duration of testosterone therapy increased the risk of developing hematocrit levels greater than 0.50 L/L. For example, after 1 year, the cumulative incidence of erythrocytosis was 8%; after 10 years, it was 38%; and after 14 years, it was 50%.

Until more specific guidance is developed for trans men, if hematocrit levels rise to 0.50-0.54 L/L, the researchers suggested taking “reasonable” steps to prevent a further increase:

- Consider switching patients who use injectable testosterone to transdermal products.

- Advise patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 to lose weight to attain a BMI of 18.5-25.

- Advise patients to stop smoking.

- Pursue treatment optimization for chronic lung disease or sleep apnea.

The study had no external funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over 10% of transgender men (females transitioning to male) who take testosterone develop high hematocrit levels that could put them at greater risk for a thrombotic event, and the largest increase in levels occurs in the first year after starting therapy, a new Dutch study indicates.

Erythrocytosis, defined as a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L, is a potentially serious side effect of testosterone therapy, say Milou Cecilia Madsen, MD, and colleagues in their article published online Feb. 18, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

When hematocrit was measured twice, 11.1% of the cohort of 1073 trans men had levels in excess of 0.50 L/L over a 20-year follow-up.

“Erythrocytosis is common in transgender men treated with testosterone, especially in those who smoke, have [a] high BMI [body mass index], and [who] use testosterone injections,” Dr. Madsen, of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, said in a statement from the Endocrine Society.

“A reasonable first step in the care of transgender men with high red blood cells while on testosterone is to advise them to quit smoking, switch injectable testosterone to gel, and, if BMI is high, to lose weight,” she added.

First large study of testosterone in trans men with 20-year follow-up

Transgender men often undergo testosterone therapy as part of gender-affirming treatment.

Secondary erythrocytosis, a condition where the body makes too many red blood cells, is a common side effect of testosterone therapy that can increase the risk of thrombolic events, heart attack, and stroke, Dr. Madsen and colleagues explained.

This is the first study of a large cohort of trans men taking testosterone therapy followed for up to 20 years. Because of the large sample size, statistical analysis with many determinants could be performed. And because of the long follow-up, a clear time relation between initiation of testosterone therapy and hematocrit could be studied, they noted.

Participants were part of the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria study, a large cohort of individuals seen at the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Amsterdam University Medical Center between 1972 and 2015.

Laboratory measurements taken between 2004 and 2018 were available for analysis. Trans men visited the center every 3-6 months during their first year of testosterone therapy and were then monitored every year or every other year.

Long-acting undecanoate injection was associated with the highest risk of a hematocrit level greater than 0.50 L/L, and the risk of erythrocytosis in those who took long-acting intramuscular injections was about threefold higher, compared with testosterone gel (adjusted odds ratio, 3.1).

In contrast, short-acting ester injections and oral administration of testosterone had a similar risk for erythrocytosis, as did testosterone gel.

Other determinants of elevated hematocrit included smoking, medical history of a number of comorbid conditions, and older age on initiation of testosterone.

In contrast, “higher testosterone levels per se were not associated with an increased odds of hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L”, the authors noted.

Current advice for trans men based on old guidance for hypogonadism

The authors said that current advice for trans men is based on recommendations for testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men (those assigned male at birth) from 2008, which advises a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L has a moderate to high risk of adverse outcome. For levels greater than 0.54 L/L, cessation of testosterone therapy, a dose reduction, or therapeutic phlebotomy to reduce the risk of adverse events is advised. For levels 0.50-0.54 L/L, no clear advice is given.

But questions remain as to whether these guidelines are applicable to trans men because the duration of testosterone therapy is much longer in trans men and hormone treatment often cannot be discontinued without causing distress.

Meanwhile, hematology guidelines indicate an upper limit for hematocrit for cis females of 0.48 L/L.

“It could be argued that the upper limit for cis females should be applied, as trans men are born with female genetics,” the authors said. “This is a subject for further research.”

Duration of testosterone therapy impacts risk of erythrocytosis

In the study, the researchers found that longer duration of testosterone therapy increased the risk of developing hematocrit levels greater than 0.50 L/L. For example, after 1 year, the cumulative incidence of erythrocytosis was 8%; after 10 years, it was 38%; and after 14 years, it was 50%.

Until more specific guidance is developed for trans men, if hematocrit levels rise to 0.50-0.54 L/L, the researchers suggested taking “reasonable” steps to prevent a further increase:

- Consider switching patients who use injectable testosterone to transdermal products.

- Advise patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 to lose weight to attain a BMI of 18.5-25.

- Advise patients to stop smoking.

- Pursue treatment optimization for chronic lung disease or sleep apnea.

The study had no external funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over 10% of transgender men (females transitioning to male) who take testosterone develop high hematocrit levels that could put them at greater risk for a thrombotic event, and the largest increase in levels occurs in the first year after starting therapy, a new Dutch study indicates.

Erythrocytosis, defined as a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L, is a potentially serious side effect of testosterone therapy, say Milou Cecilia Madsen, MD, and colleagues in their article published online Feb. 18, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

When hematocrit was measured twice, 11.1% of the cohort of 1073 trans men had levels in excess of 0.50 L/L over a 20-year follow-up.

“Erythrocytosis is common in transgender men treated with testosterone, especially in those who smoke, have [a] high BMI [body mass index], and [who] use testosterone injections,” Dr. Madsen, of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, said in a statement from the Endocrine Society.

“A reasonable first step in the care of transgender men with high red blood cells while on testosterone is to advise them to quit smoking, switch injectable testosterone to gel, and, if BMI is high, to lose weight,” she added.

First large study of testosterone in trans men with 20-year follow-up

Transgender men often undergo testosterone therapy as part of gender-affirming treatment.

Secondary erythrocytosis, a condition where the body makes too many red blood cells, is a common side effect of testosterone therapy that can increase the risk of thrombolic events, heart attack, and stroke, Dr. Madsen and colleagues explained.

This is the first study of a large cohort of trans men taking testosterone therapy followed for up to 20 years. Because of the large sample size, statistical analysis with many determinants could be performed. And because of the long follow-up, a clear time relation between initiation of testosterone therapy and hematocrit could be studied, they noted.

Participants were part of the Amsterdam Cohort of Gender Dysphoria study, a large cohort of individuals seen at the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at Amsterdam University Medical Center between 1972 and 2015.

Laboratory measurements taken between 2004 and 2018 were available for analysis. Trans men visited the center every 3-6 months during their first year of testosterone therapy and were then monitored every year or every other year.

Long-acting undecanoate injection was associated with the highest risk of a hematocrit level greater than 0.50 L/L, and the risk of erythrocytosis in those who took long-acting intramuscular injections was about threefold higher, compared with testosterone gel (adjusted odds ratio, 3.1).

In contrast, short-acting ester injections and oral administration of testosterone had a similar risk for erythrocytosis, as did testosterone gel.

Other determinants of elevated hematocrit included smoking, medical history of a number of comorbid conditions, and older age on initiation of testosterone.

In contrast, “higher testosterone levels per se were not associated with an increased odds of hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L”, the authors noted.

Current advice for trans men based on old guidance for hypogonadism

The authors said that current advice for trans men is based on recommendations for testosterone-treated hypogonadal cis men (those assigned male at birth) from 2008, which advises a hematocrit greater than 0.50 L/L has a moderate to high risk of adverse outcome. For levels greater than 0.54 L/L, cessation of testosterone therapy, a dose reduction, or therapeutic phlebotomy to reduce the risk of adverse events is advised. For levels 0.50-0.54 L/L, no clear advice is given.

But questions remain as to whether these guidelines are applicable to trans men because the duration of testosterone therapy is much longer in trans men and hormone treatment often cannot be discontinued without causing distress.

Meanwhile, hematology guidelines indicate an upper limit for hematocrit for cis females of 0.48 L/L.

“It could be argued that the upper limit for cis females should be applied, as trans men are born with female genetics,” the authors said. “This is a subject for further research.”

Duration of testosterone therapy impacts risk of erythrocytosis

In the study, the researchers found that longer duration of testosterone therapy increased the risk of developing hematocrit levels greater than 0.50 L/L. For example, after 1 year, the cumulative incidence of erythrocytosis was 8%; after 10 years, it was 38%; and after 14 years, it was 50%.

Until more specific guidance is developed for trans men, if hematocrit levels rise to 0.50-0.54 L/L, the researchers suggested taking “reasonable” steps to prevent a further increase:

- Consider switching patients who use injectable testosterone to transdermal products.

- Advise patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 to lose weight to attain a BMI of 18.5-25.

- Advise patients to stop smoking.

- Pursue treatment optimization for chronic lung disease or sleep apnea.

The study had no external funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New approach to breast screening based on breast density at 40

The result would then be used to stratify further screening, with annual screening starting at age 40 for average-risk women who have dense breasts, and screening every 2 years starting at age 50 for women without dense breasts.

Such an approach would be cost effective and offers a more targeted risk-based strategy for the early detection of breast cancer when compared with current practices, say the authors, led by Tina Shih, PhD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Their modeling study was published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, experts writing in an accompanying editorial are not persuaded. Karla Kerlikowske, MD, and Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, both from the University of California, San Francisco, point out that not all women with dense breasts are at increased risk for breast cancer. They caution against relying on breast density alone when determining screening strategies, and say age and other risk factors also need to be considered.

New approach proposed

Current recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force suggest that women in their 40s can choose to undergo screening mammography based on their own personal preference, Dr. Shih explained in an interview.

However, these recommendations do not take into consideration the additional risk that breast density confers on breast cancer risk – and the only way women can know their breast density is to have a mammogram. “If you follow [current] guidelines, you would not know about your breast density until the age of 45 or 50,” she commented.

“But what if you knew about breast density earlier on and then acted on it –would that make a difference?” This was the question her team set out to explore.

For their study, the authors defined women with dense breasts as those with the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category C (heterogeneously dense breasts) and category D (extremely dense breasts).

The team used a computer model to compare seven different breast screening strategies:

- No screening.

- Triennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (T50).

- Biennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and triennial. screening from age 50 to 75 for women without dense breasts at the age of 50 (SA50T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and biennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breast at age 50 (SA50B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 49, and triennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 40, and biennial mammography for women from age 50 to 75 without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40B50).

Compared with a no-screening strategy, the average number of mammography sessions through a woman’s lifetime would increase from seven mammograms per lifetime for the least frequent screening (T50) to 22 mammograms per lifetime for the most intensive screening schedule, the team reports.

Compared with no screening, screening would reduce breast cancer deaths by 8.6 per 1,000 women (T50)–13.2 per 1,000 women (SA40B50).

A cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the proposed new approach (SA40B50) yielded an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $36,200 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), compared with the currently recommended biennial screening strategy. This is well within the willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per QALY that is generally accepted by society, the authors point out.

On the other hand, false-positive results and overdiagnosis would increase, the authors note.

The average number of false positives would increase from 141.2 per 1,000 women who underwent the least frequent triennial mammography screening schedule (T50) to 567.3 per 1,000 women with the new approach (SA40B50).

Rates of overdiagnosis would also increase from a low of 12.5% to a high of 18.6%, they add.

“With this study, we are not saying that everybody should start screening at the age of 40. We’re just saying, do a baseline mammography at 40, know your breast density status, and then we can try to modify the screening schedule based on individual risk,” Dr. Shih emphasized.

“Compared with other screening strategies examined in our study, this strategy is associated with the greatest reduction in breast cancer mortality and is cost effective, [although it] involves the most screening mammograms in a woman’s lifetime and higher rates of false-positive results and overdiagnosis,” the authors conclude.

Fundamental problem with this approach

The fundamental problem with this approach of stratifying risk on measurement of breast density – and on the basis of a single reading – is that not every woman with dense breasts is at increased risk for breast cancer, the editorialists comment.

Dr. Kerlikowske and Dr. Bibbins-Domingo point out that, in fact, only about one-quarter of women with dense breasts are at high risk for a missed invasive cancer within 1 year of a negative mammogram, and these women can be identified by using the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium risk model.

“This observation means that most women with dense breasts can undergo biennial screening and need not consider annual screening or supplemental imaging,” the editorialists write.

“Thus, we caution against using breast density alone to determine if a woman is at elevated risk for breast cancer,” they emphasize.

An alternative option is to focus on overall risk to select screening strategies, they suggest. For example, most guidelines recommend screening from age 50 to 74, so identifying women in their 40s who have the same risk of a woman aged 50-59 is one way to determine who may benefit from earlier initiation of screening, the editorialists observe.

“Thus, women who have a first-degree relative with breast cancer or a history of breast biopsy could be offered screening in their 40s, and, if mammography shows dense breasts, they could continue biennial screening through their 40s,” the editorialists observe. “Such women with nondense breasts could resume biennial screening at age 50 years.”

Dr. Shih told this news organization that she did not disagree with the editorialists’ suggestion that physicians could focus on overall breast cancer risk to select an appropriate screening strategy for individual patients.

“What we are suggesting is, ‘Let’s just do a baseline assessment at the age of 40 so women know their breast density instead of waiting until they are older,’ “ she said.

“But what the editorialists are suggesting is a strategy that could be even more cost effective,” she acknowledged. Dr. Shih also said that Dr. Kerlikowske and Dr. Bibbins-Domingo’s estimate that only one-quarter of women with dense breasts are actually at high risk for breast cancer likely reflects their limitation of breast density to only those women with BI-RADs category “D” – extremely dense breasts.

Yet as Dr. Shih notes, women with category C and category D breast densities are both at higher risk for breast cancer, so ignoring women with lesser degrees of breast density still doesn’t address the fact that they have a higher-than-average risk for breast cancer.

“It’s getting harder to make universal screening strategies work as we are learning more and more about breast cancer, so people are starting to talk about screening strategies based on a patient’s risk classification,” Dr. Shih noted.

“It’ll be harder to implement these kinds of strategies, but it seems like the right way to go,” she added.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Shih reports grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Pfizer and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Dr. Kerlikowske is an unpaid consultant for GRAIL for the STRIVE study. Dr. Bibbins-Domingo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The result would then be used to stratify further screening, with annual screening starting at age 40 for average-risk women who have dense breasts, and screening every 2 years starting at age 50 for women without dense breasts.

Such an approach would be cost effective and offers a more targeted risk-based strategy for the early detection of breast cancer when compared with current practices, say the authors, led by Tina Shih, PhD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Their modeling study was published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, experts writing in an accompanying editorial are not persuaded. Karla Kerlikowske, MD, and Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, both from the University of California, San Francisco, point out that not all women with dense breasts are at increased risk for breast cancer. They caution against relying on breast density alone when determining screening strategies, and say age and other risk factors also need to be considered.

New approach proposed

Current recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force suggest that women in their 40s can choose to undergo screening mammography based on their own personal preference, Dr. Shih explained in an interview.

However, these recommendations do not take into consideration the additional risk that breast density confers on breast cancer risk – and the only way women can know their breast density is to have a mammogram. “If you follow [current] guidelines, you would not know about your breast density until the age of 45 or 50,” she commented.

“But what if you knew about breast density earlier on and then acted on it –would that make a difference?” This was the question her team set out to explore.

For their study, the authors defined women with dense breasts as those with the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category C (heterogeneously dense breasts) and category D (extremely dense breasts).

The team used a computer model to compare seven different breast screening strategies:

- No screening.

- Triennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (T50).

- Biennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and triennial. screening from age 50 to 75 for women without dense breasts at the age of 50 (SA50T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and biennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breast at age 50 (SA50B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 49, and triennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 40, and biennial mammography for women from age 50 to 75 without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40B50).

Compared with a no-screening strategy, the average number of mammography sessions through a woman’s lifetime would increase from seven mammograms per lifetime for the least frequent screening (T50) to 22 mammograms per lifetime for the most intensive screening schedule, the team reports.

Compared with no screening, screening would reduce breast cancer deaths by 8.6 per 1,000 women (T50)–13.2 per 1,000 women (SA40B50).

A cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the proposed new approach (SA40B50) yielded an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $36,200 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), compared with the currently recommended biennial screening strategy. This is well within the willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per QALY that is generally accepted by society, the authors point out.

On the other hand, false-positive results and overdiagnosis would increase, the authors note.

The average number of false positives would increase from 141.2 per 1,000 women who underwent the least frequent triennial mammography screening schedule (T50) to 567.3 per 1,000 women with the new approach (SA40B50).

Rates of overdiagnosis would also increase from a low of 12.5% to a high of 18.6%, they add.

“With this study, we are not saying that everybody should start screening at the age of 40. We’re just saying, do a baseline mammography at 40, know your breast density status, and then we can try to modify the screening schedule based on individual risk,” Dr. Shih emphasized.

“Compared with other screening strategies examined in our study, this strategy is associated with the greatest reduction in breast cancer mortality and is cost effective, [although it] involves the most screening mammograms in a woman’s lifetime and higher rates of false-positive results and overdiagnosis,” the authors conclude.

Fundamental problem with this approach

The fundamental problem with this approach of stratifying risk on measurement of breast density – and on the basis of a single reading – is that not every woman with dense breasts is at increased risk for breast cancer, the editorialists comment.

Dr. Kerlikowske and Dr. Bibbins-Domingo point out that, in fact, only about one-quarter of women with dense breasts are at high risk for a missed invasive cancer within 1 year of a negative mammogram, and these women can be identified by using the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium risk model.

“This observation means that most women with dense breasts can undergo biennial screening and need not consider annual screening or supplemental imaging,” the editorialists write.

“Thus, we caution against using breast density alone to determine if a woman is at elevated risk for breast cancer,” they emphasize.

An alternative option is to focus on overall risk to select screening strategies, they suggest. For example, most guidelines recommend screening from age 50 to 74, so identifying women in their 40s who have the same risk of a woman aged 50-59 is one way to determine who may benefit from earlier initiation of screening, the editorialists observe.

“Thus, women who have a first-degree relative with breast cancer or a history of breast biopsy could be offered screening in their 40s, and, if mammography shows dense breasts, they could continue biennial screening through their 40s,” the editorialists observe. “Such women with nondense breasts could resume biennial screening at age 50 years.”

Dr. Shih told this news organization that she did not disagree with the editorialists’ suggestion that physicians could focus on overall breast cancer risk to select an appropriate screening strategy for individual patients.

“What we are suggesting is, ‘Let’s just do a baseline assessment at the age of 40 so women know their breast density instead of waiting until they are older,’ “ she said.

“But what the editorialists are suggesting is a strategy that could be even more cost effective,” she acknowledged. Dr. Shih also said that Dr. Kerlikowske and Dr. Bibbins-Domingo’s estimate that only one-quarter of women with dense breasts are actually at high risk for breast cancer likely reflects their limitation of breast density to only those women with BI-RADs category “D” – extremely dense breasts.

Yet as Dr. Shih notes, women with category C and category D breast densities are both at higher risk for breast cancer, so ignoring women with lesser degrees of breast density still doesn’t address the fact that they have a higher-than-average risk for breast cancer.

“It’s getting harder to make universal screening strategies work as we are learning more and more about breast cancer, so people are starting to talk about screening strategies based on a patient’s risk classification,” Dr. Shih noted.

“It’ll be harder to implement these kinds of strategies, but it seems like the right way to go,” she added.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Shih reports grants from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Pfizer and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Dr. Kerlikowske is an unpaid consultant for GRAIL for the STRIVE study. Dr. Bibbins-Domingo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The result would then be used to stratify further screening, with annual screening starting at age 40 for average-risk women who have dense breasts, and screening every 2 years starting at age 50 for women without dense breasts.

Such an approach would be cost effective and offers a more targeted risk-based strategy for the early detection of breast cancer when compared with current practices, say the authors, led by Tina Shih, PhD, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Their modeling study was published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

However, experts writing in an accompanying editorial are not persuaded. Karla Kerlikowske, MD, and Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, both from the University of California, San Francisco, point out that not all women with dense breasts are at increased risk for breast cancer. They caution against relying on breast density alone when determining screening strategies, and say age and other risk factors also need to be considered.

New approach proposed

Current recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force suggest that women in their 40s can choose to undergo screening mammography based on their own personal preference, Dr. Shih explained in an interview.

However, these recommendations do not take into consideration the additional risk that breast density confers on breast cancer risk – and the only way women can know their breast density is to have a mammogram. “If you follow [current] guidelines, you would not know about your breast density until the age of 45 or 50,” she commented.

“But what if you knew about breast density earlier on and then acted on it –would that make a difference?” This was the question her team set out to explore.

For their study, the authors defined women with dense breasts as those with the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category C (heterogeneously dense breasts) and category D (extremely dense breasts).

The team used a computer model to compare seven different breast screening strategies:

- No screening.

- Triennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (T50).

- Biennial mammography from age 50 to 75 years (B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and triennial. screening from age 50 to 75 for women without dense breasts at the age of 50 (SA50T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 50 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 50, and biennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breast at age 50 (SA50B50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 49, and triennial screening from age 50 to 75 for those without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40T50).

- Stratified annual mammography from age 40 to 75 for women with dense breasts at age 40, and biennial mammography for women from age 50 to 75 without dense breasts at age 40 (SA40B50).